User login

Stroke Centers More Common Where Laws Encourage Them

State laws have played a big part in boosting the number of hospitals where specialized stroke care is available, a new study shows.

During the study, the increase in the number of hospitals certified as primary stroke centers was more than twice as high in states with stroke legislation as in states without similar laws.

At these hospitals, a dedicated stroke-focused program staffed by professionals with special training delivers emergency therapy rapidly and reliably.

All hospitals should be able to see patients with stroke, but PSC certification attests to quality of care, said lead author Dr. Ken Uchino of the Cleveland Clinic.

"It takes money and effort to organize quality care," he told Reuters Health by email. "Sometimes a hospital is so small that the facility does not expect many patients with stroke to arrive. Sometimes the resources to provide quality care are not available, such as radiology technicians on call to run a CT scanner 24 hours a day or a specialist physician in the community."

U.S. organizations first began certifying stroke centers in 2003. Some states developed their own certification programs, and many passed laws requiring ambulance personnel to take an acute stroke patient directly to a certified center, bypassing hospitals that are not certified.

These laws seem to have encouraged more hospitals to get certification, according to a paper online now in the journal Stroke.

Between 2009 and 2013, states with stroke legislation had a 16% increase in PSC certification, compared to a 6% increase in states without similar legislation.

"I think if a hospital administrator realizes that an ambulance might bypass his or her hospital because it is not stroke-certified, there is an incentive to organize stroke care in the hospital and have stroke center certification," Uchino said.

By 2013, about a third of short-term adult general hospitals with emergency departments in the U.S. were certified as primary stroke centers, he said. But growth rates have varied by state, and by 2013 there were still three states with only one certified center, he said.

Out of 4,640 general hospitals with emergency rooms in the country, 1,505 have been certified as primary stroke centers following action by state legislatures. But the proportion of stroke centers by state still varied from as low as 4% in Wyoming, which has no stroke legislation, to 100% in Delaware, which does have stroke laws.

"Massachusetts, Florida, and New Jersey, which passed stroke legislation in 2004, had 74% to 97% of the hospitals certified as stroke centers by 2013," Uchino said.

Larger, more urban hospitals in states with higher economic output are most likely to be certified as primary stroke centers, the researchers found.

Patients brought to a certified stroke center have a better chance of survival than those brought elsewhere, Uchino said.

Almost all large hospitals can and should be stroke centers, and small hospitals still need help to improve, he said.

"Small hospitals still can become stroke centers, but they had to be creative with how they pulled resources together," said Dr. Lee H. Schwamm of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

"Every community should have at least one" primary stroke center, Schwamm, who was not part of the new study, told Reuters Health by phone. "The real challenge is how do I ensure equitable access for people all over the country."

State laws have played a big part in boosting the number of hospitals where specialized stroke care is available, a new study shows.

During the study, the increase in the number of hospitals certified as primary stroke centers was more than twice as high in states with stroke legislation as in states without similar laws.

At these hospitals, a dedicated stroke-focused program staffed by professionals with special training delivers emergency therapy rapidly and reliably.

All hospitals should be able to see patients with stroke, but PSC certification attests to quality of care, said lead author Dr. Ken Uchino of the Cleveland Clinic.

"It takes money and effort to organize quality care," he told Reuters Health by email. "Sometimes a hospital is so small that the facility does not expect many patients with stroke to arrive. Sometimes the resources to provide quality care are not available, such as radiology technicians on call to run a CT scanner 24 hours a day or a specialist physician in the community."

U.S. organizations first began certifying stroke centers in 2003. Some states developed their own certification programs, and many passed laws requiring ambulance personnel to take an acute stroke patient directly to a certified center, bypassing hospitals that are not certified.

These laws seem to have encouraged more hospitals to get certification, according to a paper online now in the journal Stroke.

Between 2009 and 2013, states with stroke legislation had a 16% increase in PSC certification, compared to a 6% increase in states without similar legislation.

"I think if a hospital administrator realizes that an ambulance might bypass his or her hospital because it is not stroke-certified, there is an incentive to organize stroke care in the hospital and have stroke center certification," Uchino said.

By 2013, about a third of short-term adult general hospitals with emergency departments in the U.S. were certified as primary stroke centers, he said. But growth rates have varied by state, and by 2013 there were still three states with only one certified center, he said.

Out of 4,640 general hospitals with emergency rooms in the country, 1,505 have been certified as primary stroke centers following action by state legislatures. But the proportion of stroke centers by state still varied from as low as 4% in Wyoming, which has no stroke legislation, to 100% in Delaware, which does have stroke laws.

"Massachusetts, Florida, and New Jersey, which passed stroke legislation in 2004, had 74% to 97% of the hospitals certified as stroke centers by 2013," Uchino said.

Larger, more urban hospitals in states with higher economic output are most likely to be certified as primary stroke centers, the researchers found.

Patients brought to a certified stroke center have a better chance of survival than those brought elsewhere, Uchino said.

Almost all large hospitals can and should be stroke centers, and small hospitals still need help to improve, he said.

"Small hospitals still can become stroke centers, but they had to be creative with how they pulled resources together," said Dr. Lee H. Schwamm of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

"Every community should have at least one" primary stroke center, Schwamm, who was not part of the new study, told Reuters Health by phone. "The real challenge is how do I ensure equitable access for people all over the country."

State laws have played a big part in boosting the number of hospitals where specialized stroke care is available, a new study shows.

During the study, the increase in the number of hospitals certified as primary stroke centers was more than twice as high in states with stroke legislation as in states without similar laws.

At these hospitals, a dedicated stroke-focused program staffed by professionals with special training delivers emergency therapy rapidly and reliably.

All hospitals should be able to see patients with stroke, but PSC certification attests to quality of care, said lead author Dr. Ken Uchino of the Cleveland Clinic.

"It takes money and effort to organize quality care," he told Reuters Health by email. "Sometimes a hospital is so small that the facility does not expect many patients with stroke to arrive. Sometimes the resources to provide quality care are not available, such as radiology technicians on call to run a CT scanner 24 hours a day or a specialist physician in the community."

U.S. organizations first began certifying stroke centers in 2003. Some states developed their own certification programs, and many passed laws requiring ambulance personnel to take an acute stroke patient directly to a certified center, bypassing hospitals that are not certified.

These laws seem to have encouraged more hospitals to get certification, according to a paper online now in the journal Stroke.

Between 2009 and 2013, states with stroke legislation had a 16% increase in PSC certification, compared to a 6% increase in states without similar legislation.

"I think if a hospital administrator realizes that an ambulance might bypass his or her hospital because it is not stroke-certified, there is an incentive to organize stroke care in the hospital and have stroke center certification," Uchino said.

By 2013, about a third of short-term adult general hospitals with emergency departments in the U.S. were certified as primary stroke centers, he said. But growth rates have varied by state, and by 2013 there were still three states with only one certified center, he said.

Out of 4,640 general hospitals with emergency rooms in the country, 1,505 have been certified as primary stroke centers following action by state legislatures. But the proportion of stroke centers by state still varied from as low as 4% in Wyoming, which has no stroke legislation, to 100% in Delaware, which does have stroke laws.

"Massachusetts, Florida, and New Jersey, which passed stroke legislation in 2004, had 74% to 97% of the hospitals certified as stroke centers by 2013," Uchino said.

Larger, more urban hospitals in states with higher economic output are most likely to be certified as primary stroke centers, the researchers found.

Patients brought to a certified stroke center have a better chance of survival than those brought elsewhere, Uchino said.

Almost all large hospitals can and should be stroke centers, and small hospitals still need help to improve, he said.

"Small hospitals still can become stroke centers, but they had to be creative with how they pulled resources together," said Dr. Lee H. Schwamm of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

"Every community should have at least one" primary stroke center, Schwamm, who was not part of the new study, told Reuters Health by phone. "The real challenge is how do I ensure equitable access for people all over the country."

New Tool Improves Harm Detection for Pediatric Inpatients

The newly developed Pediatric All-Cause Harm Measurement Tool (PACHMT) improved detection of harms in pediatric inpatients in a recent pilot study.

Using the tool, researchers found a rate of 40 harms per 100 patients admitted, and at least one harm in nearly a quarter of the children in the study. Close to half of the events were potentially or definitely preventable.

"Safety is measured inconsistently in health care, and the only way to make progress to improving these rates of harm is to understand how our patients are impacted by the care they receive," says Dr. David C. Stockwell, of George Washington University and Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. "Therefore, we would like to see wider adoption of active surveillance of safety events with an approach like the PACHMT.

“While not replacing voluntarily reported events, it would greatly augment the understanding of all-cause harm." TH

—Reuters Health

The newly developed Pediatric All-Cause Harm Measurement Tool (PACHMT) improved detection of harms in pediatric inpatients in a recent pilot study.

Using the tool, researchers found a rate of 40 harms per 100 patients admitted, and at least one harm in nearly a quarter of the children in the study. Close to half of the events were potentially or definitely preventable.

"Safety is measured inconsistently in health care, and the only way to make progress to improving these rates of harm is to understand how our patients are impacted by the care they receive," says Dr. David C. Stockwell, of George Washington University and Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. "Therefore, we would like to see wider adoption of active surveillance of safety events with an approach like the PACHMT.

“While not replacing voluntarily reported events, it would greatly augment the understanding of all-cause harm." TH

—Reuters Health

The newly developed Pediatric All-Cause Harm Measurement Tool (PACHMT) improved detection of harms in pediatric inpatients in a recent pilot study.

Using the tool, researchers found a rate of 40 harms per 100 patients admitted, and at least one harm in nearly a quarter of the children in the study. Close to half of the events were potentially or definitely preventable.

"Safety is measured inconsistently in health care, and the only way to make progress to improving these rates of harm is to understand how our patients are impacted by the care they receive," says Dr. David C. Stockwell, of George Washington University and Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. "Therefore, we would like to see wider adoption of active surveillance of safety events with an approach like the PACHMT.

“While not replacing voluntarily reported events, it would greatly augment the understanding of all-cause harm." TH

—Reuters Health

Risk Stratification Insufficient for Predicting DVT in Hospitalized Patients: JAMA Internal Medicine Study

The Wells score is only slightly better than a coin toss for predicting deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in hospitalized patients, researchers have found.

"The Wells score risk stratification is not sufficient to rule out DVT or influence management decisions in the inpatient setting," Dr. Patricia C. Silveira from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston says.

Although the Wells score has been validated in outpatient and ED settings, it has not been studied in hospitalized patients in a large prospective trial, Dr. Silveira and her colleagues note in JAMA Internal Medicine, online May 18.

The team evaluated the utility of the tool for risk stratification of inpatients with suspected DVT in a prospective study that included more than 1,100 patients. About one in eight were found on lower-extremity venous duplex ultrasound studies (LEUS) to have proximal DVT and 9.2% to have distal DVT.

The incidence of proximal DVT in the low, moderate, and high Wells pretest probability groups was 5.9%, 9.5%, and 16.4%, respectively, a much narrower range than was previously reported for outpatients (3.0%, 16.6%, and 74.6%).

The AUC for the discriminatory accuracy of the Wells score for risk of proximal DVT identified on LEUS was only 0.6 (a coin toss would yield a predicted AUC of 0.5), the researchers found.

Results were even less informative for distal DVT, where low, moderate, and high pretest probability groups had DVT incidences of 7.4%, 9.1%, and 9.7%, respectively.

"Physician should use their clinical judgment to order lower extremity ultrasound studies for hospitalized patients with suspected DVT," Dr. Silveira concludes. "A new clinical decision rule might be useful to determine a patient's pre-test probability of DVT in the inpatient setting."

Dr. Erika Leemann Price from San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California, who coauthored an invited commentary on the new report, told Reuters Health by email, "In the inpatient setting, the Wells score for DVT doesn't do a good job of telling us who has a DVT and who doesn't. Inpatients are different from outpatients in that they are at greater risk for DVT overall, but they also have multiple other comorbidities that can mimic the signs and symptoms of DVT.

"We don't currently have a validated clinical prediction model for DVT in the inpatient setting, although there is clearly a need for one that includes factors more predictive of VTE (venous thromboembolism) specifically in inpatients," Dr. Price says. "For now, if you are worried that your hospitalized patient may have a DVT, skip the Wells score and get an ultrasound." TH

—Reuters Health

The Wells score is only slightly better than a coin toss for predicting deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in hospitalized patients, researchers have found.

"The Wells score risk stratification is not sufficient to rule out DVT or influence management decisions in the inpatient setting," Dr. Patricia C. Silveira from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston says.

Although the Wells score has been validated in outpatient and ED settings, it has not been studied in hospitalized patients in a large prospective trial, Dr. Silveira and her colleagues note in JAMA Internal Medicine, online May 18.

The team evaluated the utility of the tool for risk stratification of inpatients with suspected DVT in a prospective study that included more than 1,100 patients. About one in eight were found on lower-extremity venous duplex ultrasound studies (LEUS) to have proximal DVT and 9.2% to have distal DVT.

The incidence of proximal DVT in the low, moderate, and high Wells pretest probability groups was 5.9%, 9.5%, and 16.4%, respectively, a much narrower range than was previously reported for outpatients (3.0%, 16.6%, and 74.6%).

The AUC for the discriminatory accuracy of the Wells score for risk of proximal DVT identified on LEUS was only 0.6 (a coin toss would yield a predicted AUC of 0.5), the researchers found.

Results were even less informative for distal DVT, where low, moderate, and high pretest probability groups had DVT incidences of 7.4%, 9.1%, and 9.7%, respectively.

"Physician should use their clinical judgment to order lower extremity ultrasound studies for hospitalized patients with suspected DVT," Dr. Silveira concludes. "A new clinical decision rule might be useful to determine a patient's pre-test probability of DVT in the inpatient setting."

Dr. Erika Leemann Price from San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California, who coauthored an invited commentary on the new report, told Reuters Health by email, "In the inpatient setting, the Wells score for DVT doesn't do a good job of telling us who has a DVT and who doesn't. Inpatients are different from outpatients in that they are at greater risk for DVT overall, but they also have multiple other comorbidities that can mimic the signs and symptoms of DVT.

"We don't currently have a validated clinical prediction model for DVT in the inpatient setting, although there is clearly a need for one that includes factors more predictive of VTE (venous thromboembolism) specifically in inpatients," Dr. Price says. "For now, if you are worried that your hospitalized patient may have a DVT, skip the Wells score and get an ultrasound." TH

—Reuters Health

The Wells score is only slightly better than a coin toss for predicting deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in hospitalized patients, researchers have found.

"The Wells score risk stratification is not sufficient to rule out DVT or influence management decisions in the inpatient setting," Dr. Patricia C. Silveira from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston says.

Although the Wells score has been validated in outpatient and ED settings, it has not been studied in hospitalized patients in a large prospective trial, Dr. Silveira and her colleagues note in JAMA Internal Medicine, online May 18.

The team evaluated the utility of the tool for risk stratification of inpatients with suspected DVT in a prospective study that included more than 1,100 patients. About one in eight were found on lower-extremity venous duplex ultrasound studies (LEUS) to have proximal DVT and 9.2% to have distal DVT.

The incidence of proximal DVT in the low, moderate, and high Wells pretest probability groups was 5.9%, 9.5%, and 16.4%, respectively, a much narrower range than was previously reported for outpatients (3.0%, 16.6%, and 74.6%).

The AUC for the discriminatory accuracy of the Wells score for risk of proximal DVT identified on LEUS was only 0.6 (a coin toss would yield a predicted AUC of 0.5), the researchers found.

Results were even less informative for distal DVT, where low, moderate, and high pretest probability groups had DVT incidences of 7.4%, 9.1%, and 9.7%, respectively.

"Physician should use their clinical judgment to order lower extremity ultrasound studies for hospitalized patients with suspected DVT," Dr. Silveira concludes. "A new clinical decision rule might be useful to determine a patient's pre-test probability of DVT in the inpatient setting."

Dr. Erika Leemann Price from San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California, who coauthored an invited commentary on the new report, told Reuters Health by email, "In the inpatient setting, the Wells score for DVT doesn't do a good job of telling us who has a DVT and who doesn't. Inpatients are different from outpatients in that they are at greater risk for DVT overall, but they also have multiple other comorbidities that can mimic the signs and symptoms of DVT.

"We don't currently have a validated clinical prediction model for DVT in the inpatient setting, although there is clearly a need for one that includes factors more predictive of VTE (venous thromboembolism) specifically in inpatients," Dr. Price says. "For now, if you are worried that your hospitalized patient may have a DVT, skip the Wells score and get an ultrasound." TH

—Reuters Health

Startup Pharmacy Takes Mail-Order to Next Level, Could Solve Medication Management Issue for Millions

It only takes one idea to help change the face of medicine and, recently, Forbes posted an article outlining a small startup pharmacy that could change the way we get our medication. Manchester, N.H.-based Pill Pack takes the whole mail-order pharmacy to a new level.

Medication management can be a major issue for seniors and their caregivers. Seniors are at risk for such problems as overmedication and drug interactions, if medications are not properly managed.

An UpToDate article says that a survey for adults aged 57-85 shows:

- At least one prescription medication was used by 81%;

- Five or more prescription medications were used by 29% of the overall survey population and by 36% of people aged 75 to 85 years; and

- 46% of prescription users also took at least one over-the-counter medication.

Hospitalists see it every day; the readmit because prescribed medication isn’t taken correctly. Possibly, Pill Pack might be one step in the right direction. TH

Lisa Courtney is director of operations at Baptist Health Systems in Birmingham, Ala., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

It only takes one idea to help change the face of medicine and, recently, Forbes posted an article outlining a small startup pharmacy that could change the way we get our medication. Manchester, N.H.-based Pill Pack takes the whole mail-order pharmacy to a new level.

Medication management can be a major issue for seniors and their caregivers. Seniors are at risk for such problems as overmedication and drug interactions, if medications are not properly managed.

An UpToDate article says that a survey for adults aged 57-85 shows:

- At least one prescription medication was used by 81%;

- Five or more prescription medications were used by 29% of the overall survey population and by 36% of people aged 75 to 85 years; and

- 46% of prescription users also took at least one over-the-counter medication.

Hospitalists see it every day; the readmit because prescribed medication isn’t taken correctly. Possibly, Pill Pack might be one step in the right direction. TH

Lisa Courtney is director of operations at Baptist Health Systems in Birmingham, Ala., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

It only takes one idea to help change the face of medicine and, recently, Forbes posted an article outlining a small startup pharmacy that could change the way we get our medication. Manchester, N.H.-based Pill Pack takes the whole mail-order pharmacy to a new level.

Medication management can be a major issue for seniors and their caregivers. Seniors are at risk for such problems as overmedication and drug interactions, if medications are not properly managed.

An UpToDate article says that a survey for adults aged 57-85 shows:

- At least one prescription medication was used by 81%;

- Five or more prescription medications were used by 29% of the overall survey population and by 36% of people aged 75 to 85 years; and

- 46% of prescription users also took at least one over-the-counter medication.

Hospitalists see it every day; the readmit because prescribed medication isn’t taken correctly. Possibly, Pill Pack might be one step in the right direction. TH

Lisa Courtney is director of operations at Baptist Health Systems in Birmingham, Ala., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

LISTEN NOW: Yale hospitalists' brush with cancer leads to healthcare cost awareness training program

ROBERT FOGERTY, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Yale University, talks about how his own bout with cancer as a college senior heading to medical school helped influence his I-CARE education initiative, which introduces cost awareness into internal medicine residency programs.

ROBERT FOGERTY, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Yale University, talks about how his own bout with cancer as a college senior heading to medical school helped influence his I-CARE education initiative, which introduces cost awareness into internal medicine residency programs.

ROBERT FOGERTY, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Yale University, talks about how his own bout with cancer as a college senior heading to medical school helped influence his I-CARE education initiative, which introduces cost awareness into internal medicine residency programs.

LISTEN NOW: UCSF's Christopher Moriates, MD, discusses waste-reduction efforts in hospitals

CHRISTOPHER MORIATES, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, talks about the change in focus and priorities needed for medicine to make progress in waste-reduction efforts.

CHRISTOPHER MORIATES, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, talks about the change in focus and priorities needed for medicine to make progress in waste-reduction efforts.

CHRISTOPHER MORIATES, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, talks about the change in focus and priorities needed for medicine to make progress in waste-reduction efforts.

LISTEN NOW: Vladimir Cadet, MPH, discusses alarm fatigue challenges and solutions

VLADIMIR N. CADET, MPH, associate with the Applied Solutions Group at ECRI Institute in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., discusses why it can be challenging for hospitals to reduce alarm fatigue and provides strategies to address this growing problem.

VLADIMIR N. CADET, MPH, associate with the Applied Solutions Group at ECRI Institute in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., discusses why it can be challenging for hospitals to reduce alarm fatigue and provides strategies to address this growing problem.

VLADIMIR N. CADET, MPH, associate with the Applied Solutions Group at ECRI Institute in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., discusses why it can be challenging for hospitals to reduce alarm fatigue and provides strategies to address this growing problem.

From a Near-Catastrophe, I-CARE

For Robert Fogerty, MD, MPH, it’s more than just a story. It’s a nightmare that he only narrowly avoided.

Now a hospitalist at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., Dr. Fogerty was an economics major in his senior year of college when he was diagnosed with metastatic testicular cancer. Early in the course of his treatment, amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy and before a major surgery, his insurance company informed him that his benefits had been exhausted. Even with family resources, the remaining bills would have been crippling. Luckily, he went to college in Massachusetts, where a state law allowed him to enroll in an individual insurance plan by exempting him from the normal pre-existing condition exclusion. Two years later, he got his life back in order and enrolled in medical school.

“What stuck with me is, yes, I was sick, and yes, I lost all my hair, and yes, I went to my final exams bald with my nausea medicine and my steroids in my pocket and all of those things,” he says. “But after that was all gone, after my hair grew back, and I had my last chemo and my surgery, and I was really starting to get my life back on track, the financial implications of that disease were still there. The financial impact of my illness outlasted the pathological impact of my illness, and the financial burdens could easily have been just as life-altering as a permanent disability.”

Although he was “unbelievably lucky” to escape with manageable medical bills, Dr. Fogerty says, other patients haven’t been as fortunate. That lesson is why he identifies so much with his patients. It’s why he posted his own story to the Costs of Care website, which stresses the importance of cost awareness in healthcare. And it’s why he has committed himself to helping other medical students and residents “remove the blinders” to understand healthcare’s often devastating financial impact.

“When I was going through my residency, I learned a lot about low sodium, and I learned a lot about bloodstream infections and what to do when someone can’t breathe and how to do a skin exam, and all of these things,” Dr. Fogerty says. “But all of these other components that were so devastating to me as a patient weren’t really a main portion of the education that we’re providing tomorrow’s doctors. I thought that was an opportunity to really change things."

By combining his clinical and economics expertise, Dr. Fogerty helped to develop a program called the Interactive Cost-Awareness Resident Exercise, or I-CARE. Launched in 2011, I-CARE seeks to make the abstract problem of healthcare costs—including unnecessary ones—more accessible to trainees. The concept is deceptively simple: Residents compete to see who can reach the correct diagnosis for a given case using the fewest possible resources.

By talking through each case, both trainees and faculty can discuss concepts like waste prevention and financial stewardship in a safe environment. Giving young doctors that “basic set of vocabulary,” Dr. Fogerty says, may help them engage in real decisions later on about a group or health system’s financial pressures and obligations.

The program has since spread to other medical centers, and what began as a cost-awareness exercise has blossomed into a broader discussion about minimizing the cost and burden to patients while maximizing safety and good medicine. TH

For Robert Fogerty, MD, MPH, it’s more than just a story. It’s a nightmare that he only narrowly avoided.

Now a hospitalist at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., Dr. Fogerty was an economics major in his senior year of college when he was diagnosed with metastatic testicular cancer. Early in the course of his treatment, amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy and before a major surgery, his insurance company informed him that his benefits had been exhausted. Even with family resources, the remaining bills would have been crippling. Luckily, he went to college in Massachusetts, where a state law allowed him to enroll in an individual insurance plan by exempting him from the normal pre-existing condition exclusion. Two years later, he got his life back in order and enrolled in medical school.

“What stuck with me is, yes, I was sick, and yes, I lost all my hair, and yes, I went to my final exams bald with my nausea medicine and my steroids in my pocket and all of those things,” he says. “But after that was all gone, after my hair grew back, and I had my last chemo and my surgery, and I was really starting to get my life back on track, the financial implications of that disease were still there. The financial impact of my illness outlasted the pathological impact of my illness, and the financial burdens could easily have been just as life-altering as a permanent disability.”

Although he was “unbelievably lucky” to escape with manageable medical bills, Dr. Fogerty says, other patients haven’t been as fortunate. That lesson is why he identifies so much with his patients. It’s why he posted his own story to the Costs of Care website, which stresses the importance of cost awareness in healthcare. And it’s why he has committed himself to helping other medical students and residents “remove the blinders” to understand healthcare’s often devastating financial impact.

“When I was going through my residency, I learned a lot about low sodium, and I learned a lot about bloodstream infections and what to do when someone can’t breathe and how to do a skin exam, and all of these things,” Dr. Fogerty says. “But all of these other components that were so devastating to me as a patient weren’t really a main portion of the education that we’re providing tomorrow’s doctors. I thought that was an opportunity to really change things."

By combining his clinical and economics expertise, Dr. Fogerty helped to develop a program called the Interactive Cost-Awareness Resident Exercise, or I-CARE. Launched in 2011, I-CARE seeks to make the abstract problem of healthcare costs—including unnecessary ones—more accessible to trainees. The concept is deceptively simple: Residents compete to see who can reach the correct diagnosis for a given case using the fewest possible resources.

By talking through each case, both trainees and faculty can discuss concepts like waste prevention and financial stewardship in a safe environment. Giving young doctors that “basic set of vocabulary,” Dr. Fogerty says, may help them engage in real decisions later on about a group or health system’s financial pressures and obligations.

The program has since spread to other medical centers, and what began as a cost-awareness exercise has blossomed into a broader discussion about minimizing the cost and burden to patients while maximizing safety and good medicine. TH

For Robert Fogerty, MD, MPH, it’s more than just a story. It’s a nightmare that he only narrowly avoided.

Now a hospitalist at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., Dr. Fogerty was an economics major in his senior year of college when he was diagnosed with metastatic testicular cancer. Early in the course of his treatment, amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy and before a major surgery, his insurance company informed him that his benefits had been exhausted. Even with family resources, the remaining bills would have been crippling. Luckily, he went to college in Massachusetts, where a state law allowed him to enroll in an individual insurance plan by exempting him from the normal pre-existing condition exclusion. Two years later, he got his life back in order and enrolled in medical school.

“What stuck with me is, yes, I was sick, and yes, I lost all my hair, and yes, I went to my final exams bald with my nausea medicine and my steroids in my pocket and all of those things,” he says. “But after that was all gone, after my hair grew back, and I had my last chemo and my surgery, and I was really starting to get my life back on track, the financial implications of that disease were still there. The financial impact of my illness outlasted the pathological impact of my illness, and the financial burdens could easily have been just as life-altering as a permanent disability.”

Although he was “unbelievably lucky” to escape with manageable medical bills, Dr. Fogerty says, other patients haven’t been as fortunate. That lesson is why he identifies so much with his patients. It’s why he posted his own story to the Costs of Care website, which stresses the importance of cost awareness in healthcare. And it’s why he has committed himself to helping other medical students and residents “remove the blinders” to understand healthcare’s often devastating financial impact.

“When I was going through my residency, I learned a lot about low sodium, and I learned a lot about bloodstream infections and what to do when someone can’t breathe and how to do a skin exam, and all of these things,” Dr. Fogerty says. “But all of these other components that were so devastating to me as a patient weren’t really a main portion of the education that we’re providing tomorrow’s doctors. I thought that was an opportunity to really change things."

By combining his clinical and economics expertise, Dr. Fogerty helped to develop a program called the Interactive Cost-Awareness Resident Exercise, or I-CARE. Launched in 2011, I-CARE seeks to make the abstract problem of healthcare costs—including unnecessary ones—more accessible to trainees. The concept is deceptively simple: Residents compete to see who can reach the correct diagnosis for a given case using the fewest possible resources.

By talking through each case, both trainees and faculty can discuss concepts like waste prevention and financial stewardship in a safe environment. Giving young doctors that “basic set of vocabulary,” Dr. Fogerty says, may help them engage in real decisions later on about a group or health system’s financial pressures and obligations.

The program has since spread to other medical centers, and what began as a cost-awareness exercise has blossomed into a broader discussion about minimizing the cost and burden to patients while maximizing safety and good medicine. TH

Bundled Payment and Hospital Medicine, Pt. 2

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series examining bundled payments and hospital medicine. In full disclosure, Dr. Whitcomb works for a company that is an Awardee Convener in the CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative.

In part one of this series, we discussed the basics of the BPCI program. Now we will delve into specific roles and opportunities for hospitalists in bundled payment programs in general, and the BPCI program in particular.

The bundled payment model can be hard to explain. One example that might make it clearer is that of LASIK vision correction surgery, where a single bundled payment covers the fees of the ophthalmologist, the operating facility, and any other services (like optometry) and medications (like eye drops). Another example is the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for hospital care, in which all facility costs are bundled together into a single payment.

A simplistic way to differentiate bundled payment from accountable care organization (ACOs) is that the former is typically initiated by an acute medical or surgical event and concludes after a recovery period—often 30, 60, or 90 days. Conversely, the latter generally covers the care of individuals within a population over time, often focusing on the management of chronic conditions.

The Opportunity

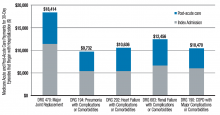

Two major opportunities for hospitalists to improve value (quality/cost) present themselves through the BPCI initiative. One is in post-acute facility utilization, and the other is in reducing readmissions. Figure 1 shows that for 30-day episodes starting with a hospitalization for five common conditions, payments for post-acute care are surprisingly close in amount to those for the preceding hospitalization.1

Much of the cost of post-acute care comes from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and, to a lesser degree, inpatient rehabilitation facilities. A broad range of research studies has demonstrated that inpatient care managed by hospitalists—compared with the traditional model—is associated with a decrease in inpatient costs; however, recent research indicates that the hospital cost savings generated by hospitalists are offset by more spending in the 30 days post discharge, specifically on more SNF care and increased readmissions.2 As another indicator that post-acute care needs a closer look, a 2013 Institute of Medicine report concluded that spending on post-acute care was responsible for the majority of Medicare’s overall regional variation in spending.1,3

Of course, success in a bundled payment model will also be derived from reducing costs in the hospital setting, such as those stemming from unnecessary or duplicative testing and imaging, injudicious use of consultants, and practices identified in programs such as Choosing Wisely.

How Your Practice Can Drive Bundled Payment Success

The aforementioned observations point to the need to improve the value of post-acute care by optimizing post-acute spending—driven mostly by SNF costs—and minimizing avoidable readmissions. I offer the following inpatient interventions to achieve these goals:

- Speak with patients early and often regarding expectations for recovery post discharge. When possible, set a goal of home discharge with the needed support.

- Write orders for early ambulation. Develop an early ambulation program with nursing and physical therapy.

- Address goals of care during the patient/family meeting. For appropriate patients with life-limiting illness, involve the palliative care service or equivalent and discuss the role of future aggressive interventions, including hospitalization, so that the course set is consistent with the patients’ goals and wishes.

- Lead the in-hospital team, instead of defaulting to others, like case management, in making an informed decision about ideal post-discharge location by factoring in caregiver availability, independence, and SNF needs. Marshal resources to enable a home recovery (i.e., home health evaluation), whether or not there is an intervening SNF stay. If patients go to a SNF, set expectations for length of stay in the facility.

- Adhere to best practices for care transitions, such as those in Project BOOST, including thorough medication reconciliation.

Beyond the Four Walls

As you aim for a high-value (high quality and affordable) discharge, your hospital medicine practice may consider new approaches to filling longstanding gaps in post-acute care. Forward-looking hospitalist groups have implemented the following approaches:

- Establish a post-discharge clinic where patients are seen after discharge, in the interim before they have an opportunity for primary care follow-up;

- Send teams to work in SNFs;

- Call patients after discharge to ensure they are following their plan of care;

- Leverage newer current procedural terminology (CPT) codes, like the Transitional Care Management or Chronic Care Management codes, to support your transitional care services;

- Provide home visits for high-risk patients; and

- Access waivers for G-codes for home visits and/or telemedicine outside of rural areas. These waivers exist under the BPCI initiative.

Shift from ‘Traditional’ Hospitalist to ‘Value’ Hospitalist

If some of the changes in practice needed to succeed in a bundled payment world seem daunting to you, it may be helpful to realize that with the challenge comes an opportunity. This opportunity for hospitalists parallels that of the early days of the specialty, when reducing length of stay created substantial support from hospital leaders and was a factor leading to the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists. In January, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services set a goal to tie 50% of Medicare payments to ‘alternative payment models’ like bundled payments by 2018. In April, as part of the sustainable growth rate fix, Medicare announced it would create substantial new bonuses for physicians who have at least 25% of their revenue in such models.1

As healthcare policy aligns behind ‘alternative payment models,’ bundled payment programs are likely to be a potent driver of an evolving hospitalist specialty. Next-generation hospitalists will be asked to take a leadership role in addressing ‘value’ with responsibility for improving care coordination and affordability over an episode of illness.

Now may be the time to take to heart the words of computer scientist Alan Kay: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

References

- Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692-694.

- Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

- Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465-1468.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series examining bundled payments and hospital medicine. In full disclosure, Dr. Whitcomb works for a company that is an Awardee Convener in the CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative.

In part one of this series, we discussed the basics of the BPCI program. Now we will delve into specific roles and opportunities for hospitalists in bundled payment programs in general, and the BPCI program in particular.

The bundled payment model can be hard to explain. One example that might make it clearer is that of LASIK vision correction surgery, where a single bundled payment covers the fees of the ophthalmologist, the operating facility, and any other services (like optometry) and medications (like eye drops). Another example is the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for hospital care, in which all facility costs are bundled together into a single payment.

A simplistic way to differentiate bundled payment from accountable care organization (ACOs) is that the former is typically initiated by an acute medical or surgical event and concludes after a recovery period—often 30, 60, or 90 days. Conversely, the latter generally covers the care of individuals within a population over time, often focusing on the management of chronic conditions.

The Opportunity

Two major opportunities for hospitalists to improve value (quality/cost) present themselves through the BPCI initiative. One is in post-acute facility utilization, and the other is in reducing readmissions. Figure 1 shows that for 30-day episodes starting with a hospitalization for five common conditions, payments for post-acute care are surprisingly close in amount to those for the preceding hospitalization.1

Much of the cost of post-acute care comes from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and, to a lesser degree, inpatient rehabilitation facilities. A broad range of research studies has demonstrated that inpatient care managed by hospitalists—compared with the traditional model—is associated with a decrease in inpatient costs; however, recent research indicates that the hospital cost savings generated by hospitalists are offset by more spending in the 30 days post discharge, specifically on more SNF care and increased readmissions.2 As another indicator that post-acute care needs a closer look, a 2013 Institute of Medicine report concluded that spending on post-acute care was responsible for the majority of Medicare’s overall regional variation in spending.1,3

Of course, success in a bundled payment model will also be derived from reducing costs in the hospital setting, such as those stemming from unnecessary or duplicative testing and imaging, injudicious use of consultants, and practices identified in programs such as Choosing Wisely.

How Your Practice Can Drive Bundled Payment Success

The aforementioned observations point to the need to improve the value of post-acute care by optimizing post-acute spending—driven mostly by SNF costs—and minimizing avoidable readmissions. I offer the following inpatient interventions to achieve these goals:

- Speak with patients early and often regarding expectations for recovery post discharge. When possible, set a goal of home discharge with the needed support.

- Write orders for early ambulation. Develop an early ambulation program with nursing and physical therapy.

- Address goals of care during the patient/family meeting. For appropriate patients with life-limiting illness, involve the palliative care service or equivalent and discuss the role of future aggressive interventions, including hospitalization, so that the course set is consistent with the patients’ goals and wishes.

- Lead the in-hospital team, instead of defaulting to others, like case management, in making an informed decision about ideal post-discharge location by factoring in caregiver availability, independence, and SNF needs. Marshal resources to enable a home recovery (i.e., home health evaluation), whether or not there is an intervening SNF stay. If patients go to a SNF, set expectations for length of stay in the facility.

- Adhere to best practices for care transitions, such as those in Project BOOST, including thorough medication reconciliation.

Beyond the Four Walls

As you aim for a high-value (high quality and affordable) discharge, your hospital medicine practice may consider new approaches to filling longstanding gaps in post-acute care. Forward-looking hospitalist groups have implemented the following approaches:

- Establish a post-discharge clinic where patients are seen after discharge, in the interim before they have an opportunity for primary care follow-up;

- Send teams to work in SNFs;

- Call patients after discharge to ensure they are following their plan of care;

- Leverage newer current procedural terminology (CPT) codes, like the Transitional Care Management or Chronic Care Management codes, to support your transitional care services;

- Provide home visits for high-risk patients; and

- Access waivers for G-codes for home visits and/or telemedicine outside of rural areas. These waivers exist under the BPCI initiative.

Shift from ‘Traditional’ Hospitalist to ‘Value’ Hospitalist

If some of the changes in practice needed to succeed in a bundled payment world seem daunting to you, it may be helpful to realize that with the challenge comes an opportunity. This opportunity for hospitalists parallels that of the early days of the specialty, when reducing length of stay created substantial support from hospital leaders and was a factor leading to the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists. In January, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services set a goal to tie 50% of Medicare payments to ‘alternative payment models’ like bundled payments by 2018. In April, as part of the sustainable growth rate fix, Medicare announced it would create substantial new bonuses for physicians who have at least 25% of their revenue in such models.1

As healthcare policy aligns behind ‘alternative payment models,’ bundled payment programs are likely to be a potent driver of an evolving hospitalist specialty. Next-generation hospitalists will be asked to take a leadership role in addressing ‘value’ with responsibility for improving care coordination and affordability over an episode of illness.

Now may be the time to take to heart the words of computer scientist Alan Kay: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

References

- Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692-694.

- Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

- Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465-1468.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series examining bundled payments and hospital medicine. In full disclosure, Dr. Whitcomb works for a company that is an Awardee Convener in the CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative.

In part one of this series, we discussed the basics of the BPCI program. Now we will delve into specific roles and opportunities for hospitalists in bundled payment programs in general, and the BPCI program in particular.

The bundled payment model can be hard to explain. One example that might make it clearer is that of LASIK vision correction surgery, where a single bundled payment covers the fees of the ophthalmologist, the operating facility, and any other services (like optometry) and medications (like eye drops). Another example is the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for hospital care, in which all facility costs are bundled together into a single payment.

A simplistic way to differentiate bundled payment from accountable care organization (ACOs) is that the former is typically initiated by an acute medical or surgical event and concludes after a recovery period—often 30, 60, or 90 days. Conversely, the latter generally covers the care of individuals within a population over time, often focusing on the management of chronic conditions.

The Opportunity

Two major opportunities for hospitalists to improve value (quality/cost) present themselves through the BPCI initiative. One is in post-acute facility utilization, and the other is in reducing readmissions. Figure 1 shows that for 30-day episodes starting with a hospitalization for five common conditions, payments for post-acute care are surprisingly close in amount to those for the preceding hospitalization.1

Much of the cost of post-acute care comes from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and, to a lesser degree, inpatient rehabilitation facilities. A broad range of research studies has demonstrated that inpatient care managed by hospitalists—compared with the traditional model—is associated with a decrease in inpatient costs; however, recent research indicates that the hospital cost savings generated by hospitalists are offset by more spending in the 30 days post discharge, specifically on more SNF care and increased readmissions.2 As another indicator that post-acute care needs a closer look, a 2013 Institute of Medicine report concluded that spending on post-acute care was responsible for the majority of Medicare’s overall regional variation in spending.1,3

Of course, success in a bundled payment model will also be derived from reducing costs in the hospital setting, such as those stemming from unnecessary or duplicative testing and imaging, injudicious use of consultants, and practices identified in programs such as Choosing Wisely.

How Your Practice Can Drive Bundled Payment Success

The aforementioned observations point to the need to improve the value of post-acute care by optimizing post-acute spending—driven mostly by SNF costs—and minimizing avoidable readmissions. I offer the following inpatient interventions to achieve these goals:

- Speak with patients early and often regarding expectations for recovery post discharge. When possible, set a goal of home discharge with the needed support.

- Write orders for early ambulation. Develop an early ambulation program with nursing and physical therapy.

- Address goals of care during the patient/family meeting. For appropriate patients with life-limiting illness, involve the palliative care service or equivalent and discuss the role of future aggressive interventions, including hospitalization, so that the course set is consistent with the patients’ goals and wishes.

- Lead the in-hospital team, instead of defaulting to others, like case management, in making an informed decision about ideal post-discharge location by factoring in caregiver availability, independence, and SNF needs. Marshal resources to enable a home recovery (i.e., home health evaluation), whether or not there is an intervening SNF stay. If patients go to a SNF, set expectations for length of stay in the facility.

- Adhere to best practices for care transitions, such as those in Project BOOST, including thorough medication reconciliation.

Beyond the Four Walls

As you aim for a high-value (high quality and affordable) discharge, your hospital medicine practice may consider new approaches to filling longstanding gaps in post-acute care. Forward-looking hospitalist groups have implemented the following approaches:

- Establish a post-discharge clinic where patients are seen after discharge, in the interim before they have an opportunity for primary care follow-up;

- Send teams to work in SNFs;

- Call patients after discharge to ensure they are following their plan of care;

- Leverage newer current procedural terminology (CPT) codes, like the Transitional Care Management or Chronic Care Management codes, to support your transitional care services;

- Provide home visits for high-risk patients; and

- Access waivers for G-codes for home visits and/or telemedicine outside of rural areas. These waivers exist under the BPCI initiative.

Shift from ‘Traditional’ Hospitalist to ‘Value’ Hospitalist

If some of the changes in practice needed to succeed in a bundled payment world seem daunting to you, it may be helpful to realize that with the challenge comes an opportunity. This opportunity for hospitalists parallels that of the early days of the specialty, when reducing length of stay created substantial support from hospital leaders and was a factor leading to the rapid growth in the number of hospitalists. In January, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services set a goal to tie 50% of Medicare payments to ‘alternative payment models’ like bundled payments by 2018. In April, as part of the sustainable growth rate fix, Medicare announced it would create substantial new bonuses for physicians who have at least 25% of their revenue in such models.1

As healthcare policy aligns behind ‘alternative payment models,’ bundled payment programs are likely to be a potent driver of an evolving hospitalist specialty. Next-generation hospitalists will be asked to take a leadership role in addressing ‘value’ with responsibility for improving care coordination and affordability over an episode of illness.

Now may be the time to take to heart the words of computer scientist Alan Kay: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.”

References

- Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692-694.

- Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

- Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465-1468.

Quality Data Dashboards Provide Performance Feedback to Physicians

A best-of-research plenary presentation at HM15 in National Harbor, Md., described a project to link physicians’ schedules to the electronic health record (EHR) in order to provide real-time, individualized performance feedback on key quality improvement and value metrics.

The abstract’s lead author, Victoria Valencia, MPH, a research data and project manager at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), explains that quality improvement priorities have driven feedback of quality metrics at the department level.

“Where I came in was to try to get the same quality metrics down to the level of the team,” she says. “We take data from our EPIC EHR, clean it up by removing outliers, merge it with our online scheduling program, and provide a robust visual presentation of individualized, real-time performance feedback to the clinical team.”

–Dr. Valencia

One example is counting the total number of phlebotomy “sticks” per day, per patient. Reporting this data helped to reduce the number of “sticks per day” by 20%, to 1.6 from 2.0. A similar approach is used for care transitions and the percentage of discharges with high-quality, after-visit summaries.

“The feedback is timely and actionable and allows the teams to address areas needing improvement,” Valencia says.

How have the doctors responded to this feedback?

“Our division is used to receiving quality feedback as part of an ongoing process that includes working meetings where the metrics are reviewed,” she says, adding that there hasn’t been pushback from the teams over these reports.

A best-of-research plenary presentation at HM15 in National Harbor, Md., described a project to link physicians’ schedules to the electronic health record (EHR) in order to provide real-time, individualized performance feedback on key quality improvement and value metrics.

The abstract’s lead author, Victoria Valencia, MPH, a research data and project manager at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), explains that quality improvement priorities have driven feedback of quality metrics at the department level.

“Where I came in was to try to get the same quality metrics down to the level of the team,” she says. “We take data from our EPIC EHR, clean it up by removing outliers, merge it with our online scheduling program, and provide a robust visual presentation of individualized, real-time performance feedback to the clinical team.”

–Dr. Valencia

One example is counting the total number of phlebotomy “sticks” per day, per patient. Reporting this data helped to reduce the number of “sticks per day” by 20%, to 1.6 from 2.0. A similar approach is used for care transitions and the percentage of discharges with high-quality, after-visit summaries.

“The feedback is timely and actionable and allows the teams to address areas needing improvement,” Valencia says.

How have the doctors responded to this feedback?

“Our division is used to receiving quality feedback as part of an ongoing process that includes working meetings where the metrics are reviewed,” she says, adding that there hasn’t been pushback from the teams over these reports.

A best-of-research plenary presentation at HM15 in National Harbor, Md., described a project to link physicians’ schedules to the electronic health record (EHR) in order to provide real-time, individualized performance feedback on key quality improvement and value metrics.

The abstract’s lead author, Victoria Valencia, MPH, a research data and project manager at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), explains that quality improvement priorities have driven feedback of quality metrics at the department level.

“Where I came in was to try to get the same quality metrics down to the level of the team,” she says. “We take data from our EPIC EHR, clean it up by removing outliers, merge it with our online scheduling program, and provide a robust visual presentation of individualized, real-time performance feedback to the clinical team.”

–Dr. Valencia

One example is counting the total number of phlebotomy “sticks” per day, per patient. Reporting this data helped to reduce the number of “sticks per day” by 20%, to 1.6 from 2.0. A similar approach is used for care transitions and the percentage of discharges with high-quality, after-visit summaries.

“The feedback is timely and actionable and allows the teams to address areas needing improvement,” Valencia says.

How have the doctors responded to this feedback?

“Our division is used to receiving quality feedback as part of an ongoing process that includes working meetings where the metrics are reviewed,” she says, adding that there hasn’t been pushback from the teams over these reports.