User login

Sunshine Rule Requires Physicians to Report Gifts from Drug, Medical Device Companies

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM

Hospitalist leaders are taking a wait-and-see approach to the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, which requires reporting of payments and gifts from drug and medical device companies. But as wary as many are after publication of the Final Rule 1 in February, SHM and other groups already have claimed at least one victory in tweaking the new rules.

The Sunshine Rule, as it’s known, was included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010. The rule, created by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), requires manufacturers to publicly report gifts, payments, or other transfers of value to physicians from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers worth more than $10 (see “Dos and Don’ts,” below).1

One major change to the law sought by SHM and others was tied to the reporting of indirect payments to speakers at accredited continuing medical education (CME) classes or courses. The proposed rule required reporting of those payments even if a particular industry group did not select the speakers or pay them. SHM and three dozen other societies lobbied CMS to change the rule.2 The final rule says indirect payments don’t have to be reported if the CME program meets widely accepted accreditation standards and the industry participant is neither directly paid nor selected by the vendor.

CME Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, said in a statement the caveat recognizes that CMS “is sending a strong message to commercial supporters: Underwriting accredited continuing education programs for health-care providers is to be applauded, not restricted.”

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, said the initial rule was too restrictive and could have reduced physician participation in important CME activities. He said the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and other industry groups already govern the ethical issue of accepting direct payments that could imply bias to patients.

“I’m not so sure we needed the Sunshine Act as part of the ACA at all because these same things were in effect from the ACCME and other CME accrediting organizations,” said Dr. Lenchus, a Team Hospitalist member and president of the medical staff at Jackson Health System in Miami. “What this has done is impose additional administrative requirements that now take time away from our seeing patients or doing clinical activity.”

Those costs will add up quickly, according to figures from the Federal Register, Dr. Lenchus said. CMS projects the administrative costs of reviewing reports at $1.9 million for teaching hospital staff—the category Dr. Lenchus says is most applicable to hospitalists.

Dr. Lenchus says there was discussion within the Public Policy Committee about how much information needed to be publicly reported in relation to CME. Some members “wanted nothing recorded” and “some people wanted everything recorded.”

“The rule that has been implemented strikes a nice balance between the two,” he said.

Transparent Process

Industry groups and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) currently are working to put in place systems and procedures to begin collecting the data in August. Data will be collected through the end of 2013 and must be reported to CMS by March 31, 2014. CMS will then unveil a public website showcasing the information by Sept. 30, 2014.

Public Policy Committee member Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, SFHM, said some hospitalists might feel they are “being picked on again” by having to report the added information. He instead looks at the intended push toward added transparency as “a set of obligations we have as physicians.”

“We have tremendous discretion about how health-care dollars are spent and with that comes a fiduciary responsibility, both to the patient and to the public,” he said. “This does not seem terribly burdensome to me. If I was getting nickel and dimed for every piece of candy I took through the exhibit hall during a meeting, that would be ridiculous. I’m happy to do this in a reasoned way.”

Dr. Percelay noted that the Sunshine Rule does not prevent industry payments to physicians or groups, but simply requires the public reporting and display of the remuneration. In that vein, he likened it to ethical rules that govern those who hold elected office.

“Someone should be able to Google and see that I’ve [received] funds from market research,” he said. “It’s not much different from politicians. It’s then up to the public and the media to do their due diligence.”

Dr. Lenchus said the public database has the potential to be misinterpreted by a public unfamiliar with how health care works. In particular, patients might not be able to discern the differences between the value of lunches, the payments for being on advisory boards, and industry-funded research.

“I really fear the public will look at this website, see there is any financial inducement to any physician, and erroneously conclude that any prescription of that company’s medication means that person is getting a kickback,” he says. “And we know that’s absolutely false.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register website. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/02/08/2013-02572/medicare-mediaid-childrens-health-insurance-programs-transparency-reports-and-reporting-of. Accessed March 24, 2013.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. Letter to CMS. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_ and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=30674. Accessed March 24, 2013.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM

Hospitalist leaders are taking a wait-and-see approach to the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, which requires reporting of payments and gifts from drug and medical device companies. But as wary as many are after publication of the Final Rule 1 in February, SHM and other groups already have claimed at least one victory in tweaking the new rules.

The Sunshine Rule, as it’s known, was included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010. The rule, created by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), requires manufacturers to publicly report gifts, payments, or other transfers of value to physicians from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers worth more than $10 (see “Dos and Don’ts,” below).1

One major change to the law sought by SHM and others was tied to the reporting of indirect payments to speakers at accredited continuing medical education (CME) classes or courses. The proposed rule required reporting of those payments even if a particular industry group did not select the speakers or pay them. SHM and three dozen other societies lobbied CMS to change the rule.2 The final rule says indirect payments don’t have to be reported if the CME program meets widely accepted accreditation standards and the industry participant is neither directly paid nor selected by the vendor.

CME Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, said in a statement the caveat recognizes that CMS “is sending a strong message to commercial supporters: Underwriting accredited continuing education programs for health-care providers is to be applauded, not restricted.”

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, said the initial rule was too restrictive and could have reduced physician participation in important CME activities. He said the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and other industry groups already govern the ethical issue of accepting direct payments that could imply bias to patients.

“I’m not so sure we needed the Sunshine Act as part of the ACA at all because these same things were in effect from the ACCME and other CME accrediting organizations,” said Dr. Lenchus, a Team Hospitalist member and president of the medical staff at Jackson Health System in Miami. “What this has done is impose additional administrative requirements that now take time away from our seeing patients or doing clinical activity.”

Those costs will add up quickly, according to figures from the Federal Register, Dr. Lenchus said. CMS projects the administrative costs of reviewing reports at $1.9 million for teaching hospital staff—the category Dr. Lenchus says is most applicable to hospitalists.

Dr. Lenchus says there was discussion within the Public Policy Committee about how much information needed to be publicly reported in relation to CME. Some members “wanted nothing recorded” and “some people wanted everything recorded.”

“The rule that has been implemented strikes a nice balance between the two,” he said.

Transparent Process

Industry groups and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) currently are working to put in place systems and procedures to begin collecting the data in August. Data will be collected through the end of 2013 and must be reported to CMS by March 31, 2014. CMS will then unveil a public website showcasing the information by Sept. 30, 2014.

Public Policy Committee member Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, SFHM, said some hospitalists might feel they are “being picked on again” by having to report the added information. He instead looks at the intended push toward added transparency as “a set of obligations we have as physicians.”

“We have tremendous discretion about how health-care dollars are spent and with that comes a fiduciary responsibility, both to the patient and to the public,” he said. “This does not seem terribly burdensome to me. If I was getting nickel and dimed for every piece of candy I took through the exhibit hall during a meeting, that would be ridiculous. I’m happy to do this in a reasoned way.”

Dr. Percelay noted that the Sunshine Rule does not prevent industry payments to physicians or groups, but simply requires the public reporting and display of the remuneration. In that vein, he likened it to ethical rules that govern those who hold elected office.

“Someone should be able to Google and see that I’ve [received] funds from market research,” he said. “It’s not much different from politicians. It’s then up to the public and the media to do their due diligence.”

Dr. Lenchus said the public database has the potential to be misinterpreted by a public unfamiliar with how health care works. In particular, patients might not be able to discern the differences between the value of lunches, the payments for being on advisory boards, and industry-funded research.

“I really fear the public will look at this website, see there is any financial inducement to any physician, and erroneously conclude that any prescription of that company’s medication means that person is getting a kickback,” he says. “And we know that’s absolutely false.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register website. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/02/08/2013-02572/medicare-mediaid-childrens-health-insurance-programs-transparency-reports-and-reporting-of. Accessed March 24, 2013.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. Letter to CMS. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_ and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=30674. Accessed March 24, 2013.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM

Hospitalist leaders are taking a wait-and-see approach to the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, which requires reporting of payments and gifts from drug and medical device companies. But as wary as many are after publication of the Final Rule 1 in February, SHM and other groups already have claimed at least one victory in tweaking the new rules.

The Sunshine Rule, as it’s known, was included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010. The rule, created by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), requires manufacturers to publicly report gifts, payments, or other transfers of value to physicians from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers worth more than $10 (see “Dos and Don’ts,” below).1

One major change to the law sought by SHM and others was tied to the reporting of indirect payments to speakers at accredited continuing medical education (CME) classes or courses. The proposed rule required reporting of those payments even if a particular industry group did not select the speakers or pay them. SHM and three dozen other societies lobbied CMS to change the rule.2 The final rule says indirect payments don’t have to be reported if the CME program meets widely accepted accreditation standards and the industry participant is neither directly paid nor selected by the vendor.

CME Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, said in a statement the caveat recognizes that CMS “is sending a strong message to commercial supporters: Underwriting accredited continuing education programs for health-care providers is to be applauded, not restricted.”

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, said the initial rule was too restrictive and could have reduced physician participation in important CME activities. He said the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and other industry groups already govern the ethical issue of accepting direct payments that could imply bias to patients.

“I’m not so sure we needed the Sunshine Act as part of the ACA at all because these same things were in effect from the ACCME and other CME accrediting organizations,” said Dr. Lenchus, a Team Hospitalist member and president of the medical staff at Jackson Health System in Miami. “What this has done is impose additional administrative requirements that now take time away from our seeing patients or doing clinical activity.”

Those costs will add up quickly, according to figures from the Federal Register, Dr. Lenchus said. CMS projects the administrative costs of reviewing reports at $1.9 million for teaching hospital staff—the category Dr. Lenchus says is most applicable to hospitalists.

Dr. Lenchus says there was discussion within the Public Policy Committee about how much information needed to be publicly reported in relation to CME. Some members “wanted nothing recorded” and “some people wanted everything recorded.”

“The rule that has been implemented strikes a nice balance between the two,” he said.

Transparent Process

Industry groups and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) currently are working to put in place systems and procedures to begin collecting the data in August. Data will be collected through the end of 2013 and must be reported to CMS by March 31, 2014. CMS will then unveil a public website showcasing the information by Sept. 30, 2014.

Public Policy Committee member Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, SFHM, said some hospitalists might feel they are “being picked on again” by having to report the added information. He instead looks at the intended push toward added transparency as “a set of obligations we have as physicians.”

“We have tremendous discretion about how health-care dollars are spent and with that comes a fiduciary responsibility, both to the patient and to the public,” he said. “This does not seem terribly burdensome to me. If I was getting nickel and dimed for every piece of candy I took through the exhibit hall during a meeting, that would be ridiculous. I’m happy to do this in a reasoned way.”

Dr. Percelay noted that the Sunshine Rule does not prevent industry payments to physicians or groups, but simply requires the public reporting and display of the remuneration. In that vein, he likened it to ethical rules that govern those who hold elected office.

“Someone should be able to Google and see that I’ve [received] funds from market research,” he said. “It’s not much different from politicians. It’s then up to the public and the media to do their due diligence.”

Dr. Lenchus said the public database has the potential to be misinterpreted by a public unfamiliar with how health care works. In particular, patients might not be able to discern the differences between the value of lunches, the payments for being on advisory boards, and industry-funded research.

“I really fear the public will look at this website, see there is any financial inducement to any physician, and erroneously conclude that any prescription of that company’s medication means that person is getting a kickback,” he says. “And we know that’s absolutely false.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register website. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/02/08/2013-02572/medicare-mediaid-childrens-health-insurance-programs-transparency-reports-and-reporting-of. Accessed March 24, 2013.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. Letter to CMS. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_ and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=30674. Accessed March 24, 2013.

'Systems,' Not 'Points,' Is Correct Terminology for ROS Statements

The “Billing and Coding Bandwagon” article in the May 2011 issue of The Hospitalist (p. 26) recently was brought to my attention and I have some concerns that the following statement gives a false impression of acceptable documentation: “When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”

In fact, that would still not be considered acceptable documentation for services that require a complete review of systems (99222, 99223, 99219, 99220, 99235, and 99236). The documentation guidelines clearly state: “A complete ROS [review of systems] inquires about the system(s) directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI plus all additional body systems.” At least 10 organ systems must be reviewed. Those systems with positive or pertinent negative responses must be individually documented. For the remaining systems, a notation indicating all other systems are negative is permissible. In the absence of such a notation, at least 10 systems must be individually documented.

What Medicare is saying is the provider must have inquired about all 14 systems, not just 10 or 12. The term “point” means nothing in an ROS statement. “Systems” is the correct terminology, not “points.”

I am afraid the article is misleading and could be providing inappropriate documentation advice to hospitalists dealing with CMS and AMA guidelines.

The “Billing and Coding Bandwagon” article in the May 2011 issue of The Hospitalist (p. 26) recently was brought to my attention and I have some concerns that the following statement gives a false impression of acceptable documentation: “When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”

In fact, that would still not be considered acceptable documentation for services that require a complete review of systems (99222, 99223, 99219, 99220, 99235, and 99236). The documentation guidelines clearly state: “A complete ROS [review of systems] inquires about the system(s) directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI plus all additional body systems.” At least 10 organ systems must be reviewed. Those systems with positive or pertinent negative responses must be individually documented. For the remaining systems, a notation indicating all other systems are negative is permissible. In the absence of such a notation, at least 10 systems must be individually documented.

What Medicare is saying is the provider must have inquired about all 14 systems, not just 10 or 12. The term “point” means nothing in an ROS statement. “Systems” is the correct terminology, not “points.”

I am afraid the article is misleading and could be providing inappropriate documentation advice to hospitalists dealing with CMS and AMA guidelines.

The “Billing and Coding Bandwagon” article in the May 2011 issue of The Hospitalist (p. 26) recently was brought to my attention and I have some concerns that the following statement gives a false impression of acceptable documentation: “When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”

In fact, that would still not be considered acceptable documentation for services that require a complete review of systems (99222, 99223, 99219, 99220, 99235, and 99236). The documentation guidelines clearly state: “A complete ROS [review of systems] inquires about the system(s) directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI plus all additional body systems.” At least 10 organ systems must be reviewed. Those systems with positive or pertinent negative responses must be individually documented. For the remaining systems, a notation indicating all other systems are negative is permissible. In the absence of such a notation, at least 10 systems must be individually documented.

What Medicare is saying is the provider must have inquired about all 14 systems, not just 10 or 12. The term “point” means nothing in an ROS statement. “Systems” is the correct terminology, not “points.”

I am afraid the article is misleading and could be providing inappropriate documentation advice to hospitalists dealing with CMS and AMA guidelines.

Lack of Transparency Plagues U.S. Health Care System

Everything has a price, and we all have become accustomed to knowing how much something is going to cost before we buy it. Generally, we start with thinking about how much we are willing to pay, then finding what we need within the range of what we expect to pay. Whether it is shopping on Amazon.com, negotiating the price with a landscaper, or going out to eat, we get to weigh the options in advance of acquiring the goods or services. And, generally ahead of the purchase of big-ticket items, we get an itemized list of what is available.

I recently had to buy a car. Some of the many decisions that went into the purchase were whether to include some of the offered amenities, including:

- “Surround sound”;

- Seat heaters;

- Blind-spot indicator system;

- Premium floor mat package; and

- Built-in GPS.

My husband and I thought about the price of each of these line items relative to what we were going to “get out of it”—e.g., the value. Seat heaters in South Carolina? No, thanks. Surround sound? We had to flip a coin on that one. Safety features? Absolutely. Premium floor mat package? Only if they were guaranteed to be Fruit Roll-Ups-resistant.

Over the course of several negotiations, we picked and chose options that were highly likely to add value (safety, comfort, convenience) and omitted the rest. Then we settled on a total price, paid the negotiated price, and drove away fairly content.

Now, this doesn’t mean that we actually knew the cost of adding each of those amenities into our new car; would anyone actually be able to tell us exactly how much each of those features cost to innovate, create, and install? Probably not, but they might be able to give us a pretty good estimate, as well as an estimate of how much had been added in to ship it to the dealer, to pay the overhead for the dealership, and to pay the dealership staff (from the front desk to the CEO). And we could feel pretty certain that most buyers would be presented with similar prices, regardless of their personal characteristics.

So all in all, there was a reasonable amount of transparency around the cost and the price of the car and all of its amenities, as there would be in most industries. Except in health care.

A Ton of Money, for What?

There was a fascinating article in the March 4 edition of Time titled “Bitter Pill” that discussed the cost and the price of health-care services.1 It certainly is a worthy topic, as the U.S. spends about 20% of our gross domestic product on health care, whereas most other developed countries spend half of that. In fact, according to the article, the U.S. spends more on health care annually ($2.8 trillion) than the top 10 countries combined—Japan, Germany, France, China, United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Brazil, Spain, and Australia.

About $800 billion of our health care is paid out annually by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS is an ongoing and substantial driver to the depth of the federal deficit. When Medicare was enacted in 1965, they expected the cost in 1990 to be about $12 billion per year, which was miscalculated by more than a factor of 10.

And the federal deficit, while insurmountably important, pales in comparison to the sobering statistic that 60% of personal bankruptcies are filed due to health-care bills.

Equally disappointing, the U.S. does not appear to get great value out of this exorbitant price tag, as our health-care outcomes certainly are not any better, and are sometimes worse, than other industrialized countries.

Elephants in the Room

The Time article talks extensively about the lack of transparency and drivers for cost in the industry. But there are two major, unreconciled questions the article fails to answer that are at the core of the issue:

- Is health care in the U.S. a right or a luxury?

- Can the U.S. health-care system be compassionate and restrictive at the same time?

You really don’t encounter the first question with any other industry. If I am hungry and do not have any money, I would not march into a restaurant and say, “I am hungry; therefore, you must feed me.” But we all feel like we can—and should—march into an emergency room and say, “I am sick; therefore, you must treat me,” no matter our financial situation. For all other industries, we rely on community resources, nonprofit agencies, and some state/federal funding to bridge gaps in basic necessities (food, housing, clothing, and transportation). And when those run short, people do without.

Car dealerships and Jiffy Lube do not have to follow any Emergency Medicine Treatment and Active Labor Act rules. If health care is a right, then we should not make individuals figure out how to get it, and we should not accept huge disparities in the provision of care based on personal characteristics.

My hospital, like most others in the U.S., is trying to figure out how to cut costs and do more with less. In a series of town-hall-style meetings, our leadership has been telling all of our hospital staff about planned cost-cutting and revenue-generating strategies. One of the tactics is to be more proactive and consistent with collecting copays in outpatient settings (before the delivery of any visit, test, or procedure) and to have parity with our local market on setting the price of those copays. But several employees were wrestling with the thought of collecting copays before the delivery of service. Some voiced a particular concern: “But what if they don’t have the money?” Again, not a conversation heard too often at car dealerships or Jiffy Lube.

The U.S. has a long way to go in reconciling these questions. Addressing them might be easier if there were more transparency in pricing. When you walk into Jiffy Lube, you are presented with all the things you might need for your car, based on make, model, and mileage; you get a listing of the cost of all the items, then you make decisions about what you do and do not need as you factor in what you are willing to spend. But when you go for your annual primary-care check-up, you are not presented a list of all the things you need (based on age, comorbidities, family history, etc.); you are not given a listing of the cost of those available services (check-up, eye exam, colonoscopy, pneumococcal vaccination); and rarely is there ever a discussion of what you are willing to spend. You just assume you need what is recommended, then get a bill later. There is almost no incentive for providers to discuss or present those prices to patients in advance. There is even less incentive to reduce the utilization of those offered services. And the price on the bill variably reflects the actual cost of the products/services provided.

In the hospital setting, the price of most products/services are based on the “chargemaster,” which is a fictional line listing of prices, which, according to the Time article, “gives them a big number to put in front of rich, uninsured patients” to make up for the losses in revenue from all other patients.

For the most part, health-care reform efforts have done little to address the two unanswered questions. And although reform efforts have triggered plenty of discussions about changing the rules on who pays for what and when, these efforts have done little to change the price or the cost of care, or make them more transparent.

The author of “Bitter Pill” makes an attempt to call out the “bad actors” in the industry, those who drive up the cost of health care—health-care leaders with generous salaries, pharmaceutical companies, device/product companies, trial lawyers, and profitable laboratory and radiology departments. But the article does not come close to capturing the other elephants in the room. Without confronting those issues, we will continue to fail to distinguish between the cost and the price, and any value within.

Reference

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Everything has a price, and we all have become accustomed to knowing how much something is going to cost before we buy it. Generally, we start with thinking about how much we are willing to pay, then finding what we need within the range of what we expect to pay. Whether it is shopping on Amazon.com, negotiating the price with a landscaper, or going out to eat, we get to weigh the options in advance of acquiring the goods or services. And, generally ahead of the purchase of big-ticket items, we get an itemized list of what is available.

I recently had to buy a car. Some of the many decisions that went into the purchase were whether to include some of the offered amenities, including:

- “Surround sound”;

- Seat heaters;

- Blind-spot indicator system;

- Premium floor mat package; and

- Built-in GPS.

My husband and I thought about the price of each of these line items relative to what we were going to “get out of it”—e.g., the value. Seat heaters in South Carolina? No, thanks. Surround sound? We had to flip a coin on that one. Safety features? Absolutely. Premium floor mat package? Only if they were guaranteed to be Fruit Roll-Ups-resistant.

Over the course of several negotiations, we picked and chose options that were highly likely to add value (safety, comfort, convenience) and omitted the rest. Then we settled on a total price, paid the negotiated price, and drove away fairly content.

Now, this doesn’t mean that we actually knew the cost of adding each of those amenities into our new car; would anyone actually be able to tell us exactly how much each of those features cost to innovate, create, and install? Probably not, but they might be able to give us a pretty good estimate, as well as an estimate of how much had been added in to ship it to the dealer, to pay the overhead for the dealership, and to pay the dealership staff (from the front desk to the CEO). And we could feel pretty certain that most buyers would be presented with similar prices, regardless of their personal characteristics.

So all in all, there was a reasonable amount of transparency around the cost and the price of the car and all of its amenities, as there would be in most industries. Except in health care.

A Ton of Money, for What?

There was a fascinating article in the March 4 edition of Time titled “Bitter Pill” that discussed the cost and the price of health-care services.1 It certainly is a worthy topic, as the U.S. spends about 20% of our gross domestic product on health care, whereas most other developed countries spend half of that. In fact, according to the article, the U.S. spends more on health care annually ($2.8 trillion) than the top 10 countries combined—Japan, Germany, France, China, United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Brazil, Spain, and Australia.

About $800 billion of our health care is paid out annually by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS is an ongoing and substantial driver to the depth of the federal deficit. When Medicare was enacted in 1965, they expected the cost in 1990 to be about $12 billion per year, which was miscalculated by more than a factor of 10.

And the federal deficit, while insurmountably important, pales in comparison to the sobering statistic that 60% of personal bankruptcies are filed due to health-care bills.

Equally disappointing, the U.S. does not appear to get great value out of this exorbitant price tag, as our health-care outcomes certainly are not any better, and are sometimes worse, than other industrialized countries.

Elephants in the Room

The Time article talks extensively about the lack of transparency and drivers for cost in the industry. But there are two major, unreconciled questions the article fails to answer that are at the core of the issue:

- Is health care in the U.S. a right or a luxury?

- Can the U.S. health-care system be compassionate and restrictive at the same time?

You really don’t encounter the first question with any other industry. If I am hungry and do not have any money, I would not march into a restaurant and say, “I am hungry; therefore, you must feed me.” But we all feel like we can—and should—march into an emergency room and say, “I am sick; therefore, you must treat me,” no matter our financial situation. For all other industries, we rely on community resources, nonprofit agencies, and some state/federal funding to bridge gaps in basic necessities (food, housing, clothing, and transportation). And when those run short, people do without.

Car dealerships and Jiffy Lube do not have to follow any Emergency Medicine Treatment and Active Labor Act rules. If health care is a right, then we should not make individuals figure out how to get it, and we should not accept huge disparities in the provision of care based on personal characteristics.

My hospital, like most others in the U.S., is trying to figure out how to cut costs and do more with less. In a series of town-hall-style meetings, our leadership has been telling all of our hospital staff about planned cost-cutting and revenue-generating strategies. One of the tactics is to be more proactive and consistent with collecting copays in outpatient settings (before the delivery of any visit, test, or procedure) and to have parity with our local market on setting the price of those copays. But several employees were wrestling with the thought of collecting copays before the delivery of service. Some voiced a particular concern: “But what if they don’t have the money?” Again, not a conversation heard too often at car dealerships or Jiffy Lube.

The U.S. has a long way to go in reconciling these questions. Addressing them might be easier if there were more transparency in pricing. When you walk into Jiffy Lube, you are presented with all the things you might need for your car, based on make, model, and mileage; you get a listing of the cost of all the items, then you make decisions about what you do and do not need as you factor in what you are willing to spend. But when you go for your annual primary-care check-up, you are not presented a list of all the things you need (based on age, comorbidities, family history, etc.); you are not given a listing of the cost of those available services (check-up, eye exam, colonoscopy, pneumococcal vaccination); and rarely is there ever a discussion of what you are willing to spend. You just assume you need what is recommended, then get a bill later. There is almost no incentive for providers to discuss or present those prices to patients in advance. There is even less incentive to reduce the utilization of those offered services. And the price on the bill variably reflects the actual cost of the products/services provided.

In the hospital setting, the price of most products/services are based on the “chargemaster,” which is a fictional line listing of prices, which, according to the Time article, “gives them a big number to put in front of rich, uninsured patients” to make up for the losses in revenue from all other patients.

For the most part, health-care reform efforts have done little to address the two unanswered questions. And although reform efforts have triggered plenty of discussions about changing the rules on who pays for what and when, these efforts have done little to change the price or the cost of care, or make them more transparent.

The author of “Bitter Pill” makes an attempt to call out the “bad actors” in the industry, those who drive up the cost of health care—health-care leaders with generous salaries, pharmaceutical companies, device/product companies, trial lawyers, and profitable laboratory and radiology departments. But the article does not come close to capturing the other elephants in the room. Without confronting those issues, we will continue to fail to distinguish between the cost and the price, and any value within.

Reference

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Everything has a price, and we all have become accustomed to knowing how much something is going to cost before we buy it. Generally, we start with thinking about how much we are willing to pay, then finding what we need within the range of what we expect to pay. Whether it is shopping on Amazon.com, negotiating the price with a landscaper, or going out to eat, we get to weigh the options in advance of acquiring the goods or services. And, generally ahead of the purchase of big-ticket items, we get an itemized list of what is available.

I recently had to buy a car. Some of the many decisions that went into the purchase were whether to include some of the offered amenities, including:

- “Surround sound”;

- Seat heaters;

- Blind-spot indicator system;

- Premium floor mat package; and

- Built-in GPS.

My husband and I thought about the price of each of these line items relative to what we were going to “get out of it”—e.g., the value. Seat heaters in South Carolina? No, thanks. Surround sound? We had to flip a coin on that one. Safety features? Absolutely. Premium floor mat package? Only if they were guaranteed to be Fruit Roll-Ups-resistant.

Over the course of several negotiations, we picked and chose options that were highly likely to add value (safety, comfort, convenience) and omitted the rest. Then we settled on a total price, paid the negotiated price, and drove away fairly content.

Now, this doesn’t mean that we actually knew the cost of adding each of those amenities into our new car; would anyone actually be able to tell us exactly how much each of those features cost to innovate, create, and install? Probably not, but they might be able to give us a pretty good estimate, as well as an estimate of how much had been added in to ship it to the dealer, to pay the overhead for the dealership, and to pay the dealership staff (from the front desk to the CEO). And we could feel pretty certain that most buyers would be presented with similar prices, regardless of their personal characteristics.

So all in all, there was a reasonable amount of transparency around the cost and the price of the car and all of its amenities, as there would be in most industries. Except in health care.

A Ton of Money, for What?

There was a fascinating article in the March 4 edition of Time titled “Bitter Pill” that discussed the cost and the price of health-care services.1 It certainly is a worthy topic, as the U.S. spends about 20% of our gross domestic product on health care, whereas most other developed countries spend half of that. In fact, according to the article, the U.S. spends more on health care annually ($2.8 trillion) than the top 10 countries combined—Japan, Germany, France, China, United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Brazil, Spain, and Australia.

About $800 billion of our health care is paid out annually by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS is an ongoing and substantial driver to the depth of the federal deficit. When Medicare was enacted in 1965, they expected the cost in 1990 to be about $12 billion per year, which was miscalculated by more than a factor of 10.

And the federal deficit, while insurmountably important, pales in comparison to the sobering statistic that 60% of personal bankruptcies are filed due to health-care bills.

Equally disappointing, the U.S. does not appear to get great value out of this exorbitant price tag, as our health-care outcomes certainly are not any better, and are sometimes worse, than other industrialized countries.

Elephants in the Room

The Time article talks extensively about the lack of transparency and drivers for cost in the industry. But there are two major, unreconciled questions the article fails to answer that are at the core of the issue:

- Is health care in the U.S. a right or a luxury?

- Can the U.S. health-care system be compassionate and restrictive at the same time?

You really don’t encounter the first question with any other industry. If I am hungry and do not have any money, I would not march into a restaurant and say, “I am hungry; therefore, you must feed me.” But we all feel like we can—and should—march into an emergency room and say, “I am sick; therefore, you must treat me,” no matter our financial situation. For all other industries, we rely on community resources, nonprofit agencies, and some state/federal funding to bridge gaps in basic necessities (food, housing, clothing, and transportation). And when those run short, people do without.

Car dealerships and Jiffy Lube do not have to follow any Emergency Medicine Treatment and Active Labor Act rules. If health care is a right, then we should not make individuals figure out how to get it, and we should not accept huge disparities in the provision of care based on personal characteristics.

My hospital, like most others in the U.S., is trying to figure out how to cut costs and do more with less. In a series of town-hall-style meetings, our leadership has been telling all of our hospital staff about planned cost-cutting and revenue-generating strategies. One of the tactics is to be more proactive and consistent with collecting copays in outpatient settings (before the delivery of any visit, test, or procedure) and to have parity with our local market on setting the price of those copays. But several employees were wrestling with the thought of collecting copays before the delivery of service. Some voiced a particular concern: “But what if they don’t have the money?” Again, not a conversation heard too often at car dealerships or Jiffy Lube.

The U.S. has a long way to go in reconciling these questions. Addressing them might be easier if there were more transparency in pricing. When you walk into Jiffy Lube, you are presented with all the things you might need for your car, based on make, model, and mileage; you get a listing of the cost of all the items, then you make decisions about what you do and do not need as you factor in what you are willing to spend. But when you go for your annual primary-care check-up, you are not presented a list of all the things you need (based on age, comorbidities, family history, etc.); you are not given a listing of the cost of those available services (check-up, eye exam, colonoscopy, pneumococcal vaccination); and rarely is there ever a discussion of what you are willing to spend. You just assume you need what is recommended, then get a bill later. There is almost no incentive for providers to discuss or present those prices to patients in advance. There is even less incentive to reduce the utilization of those offered services. And the price on the bill variably reflects the actual cost of the products/services provided.

In the hospital setting, the price of most products/services are based on the “chargemaster,” which is a fictional line listing of prices, which, according to the Time article, “gives them a big number to put in front of rich, uninsured patients” to make up for the losses in revenue from all other patients.

For the most part, health-care reform efforts have done little to address the two unanswered questions. And although reform efforts have triggered plenty of discussions about changing the rules on who pays for what and when, these efforts have done little to change the price or the cost of care, or make them more transparent.

The author of “Bitter Pill” makes an attempt to call out the “bad actors” in the industry, those who drive up the cost of health care—health-care leaders with generous salaries, pharmaceutical companies, device/product companies, trial lawyers, and profitable laboratory and radiology departments. But the article does not come close to capturing the other elephants in the room. Without confronting those issues, we will continue to fail to distinguish between the cost and the price, and any value within.

Reference

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Documentation, CMS-Approved Language Key to Getting Paid for Hospitalist Teaching Services

When hospitalists work in academic centers, medical and surgical services are furnished, in part, by a resident within the scope of the hospitalists’ training program. A resident is “an individual who participates in an approved graduate medical education (GME) program or a physician who is not in an approved GME program but who is authorized to practice only in a hospital setting.”1 Resident services are covered by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and paid by the Fiscal Intermediary through direct GME and Indirect Medical Education (IME) payments. These services are not billed or paid using the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The teaching physician is responsible for supervising the resident’s health-care delivery but is not paid for the resident’s work. The teaching physician is paid for their personal and medically necessary service in providing patient care. The teaching physician has the option to perform the entire service, or perform the self-determined critical or key portion(s) of the service.

Comprehensive Service

Teaching physicians independently see the patient and perform all required elements to support the visit level (e.g. 99233: subsequent hospital care, per day, which requires at least two of the following three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, or high-complexity medical decision-making).2 The teaching physician writes a note independent of a resident encounter with the patient or documentation. The teaching physician note “stands alone” and does not rely on the resident’s documentation. If the resident saw the patient and documented the encounter, the teaching physician might choose to “link to” the resident note in lieu of personally documenting the entire service. The linking statement must demonstrate teaching physician involvement in the patient encounter and participation in patient management. Use of CMS-approved statements is best to meet these requirements. Statement examples include:3

- “I performed a history and physical examination of the patient and discussed his management with the resident. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree with the documented findings and plan of care.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I agree with the findings and the plan of care as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw and examined the patient. I agree with the resident’s note, except the heart murmur is louder, so I will obtain an echo to evaluate.”

Each of these statements meets the minimum requirements for billing. However, teaching physicians should offer more information in support of other clinical, quality, and regulatory initiatives and mandates, better exemplified in the last example. The reported visit level will be supported by the combined documentation (teaching physician and resident).

The teaching physician submits a claim in their name and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99223-GC). This alerts the Medicare contractor that services were provided under teaching physician rules. Requests for documentation should include a response with medical record entries from the teaching physician and resident.

Critical/Key Portion

“Supervised” service: The resident and teaching physician can round together; they can see the patient at the same time. The teaching physician observes the resident’s performance during the patient encounter, or personally performs self-determined elements of patient care. The resident documents their patient care. The attending must still note their presence in the medical record, performance of the critical or key portions of the service, and involvement in patient management. CMS-accepted statements include:3

- “I was present with the resident during the history and exam. I discussed the case with the resident and agree with the findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw the patient with the resident and agree with the resident’s findings and plan.”

Although these statements demonstrate acceptable billing language, they lack patient-specific details that support the teaching physician’s personal contribution to patient care and the quality of their expertise. The teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99232-GC).

“Shared” service: The resident sees the patient unaccompanied and documents the corresponding care provided. The teaching physician sees the patient at a different time but performs only the critical or key portions of the service. The case is subsequently discussed with the resident. The teaching physician must document their presence and performance of the critical or key portions of the service, along with any patient management. Using CMS-quoted statements ensures regulatory compliance:3

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree, except that the picture is more consistent with pericarditis than myocardial ischemia. Will begin NSAIDs.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Discussed with resident and agree with resident’s findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “See resident’s note for details. I saw and evaluated the patient and agree with the resident’s finding and plans as written.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Agree with resident’s note, but lower extremities are weaker, now 3/5; MRI of L/S spine today.”

Once again, the teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99233-GC).

EHR Considerations

When seeing patients independent of one another, the timing of the teaching physician and resident encounters does not impact billing. However, the time that the resident encounter is documented in the medical record can significantly impact the payment when reviewed by external auditors. When the resident note is dated and timed later than the teaching physician’s entry, the teaching physician cannot consider the resident’s note for visit-level selection. The teaching physician should not “link to” a resident note that is viewed as “not having been written” prior to the teaching physician note. This would not fulfill the requirements represented in the CMS-approved language “I reviewed the resident’s note and agree.”

Electronic health record (EHR) systems sometimes hinder compliance. If the resident completes the note but does not “finalize” or “close” the encounter until after the teaching physician documents their own note, it can falsely appear that the resident note did not exist at the time the teaching physician created their entry. Because an auditor can only view the finalized entries, the timing of each entry might be erroneously represented. Proper training and closing of encounters can diminish these issues.

Additionally, scribing the attestation is not permitted. Residents cannot document the teaching physician attestation on behalf of the physician under any circumstance. CMS rules require the teaching physician to document their presence, participation, and management of the patient. In an EHR, the teaching physician must document this entry under his/her own log-in and password, which is not to be shared with anyone.

Students

CMS defines student as “an individual who participates in an accredited educational program [e.g. a medical school] that is not an approved GME program.”1 A student is not regarded as a “physician in training,” and the service is not eligible for reimbursement consideration under the teaching physician rules.

Per CMS guidelines, students can document services in the medical record, but the teaching physician may only refer to the student’s systems review and past/family/social history entries. The teaching physician must verify and redocument the history of present illness. A student’s physical exam findings or medical decision-making are not suitable for tethering, and the teaching physician must personally perform and redocument the physical exam and medical decision-making. The visit level reflects only the teaching physician’s personally performed and documented service.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Guidelines for Teaching Physicians, Interns, Residents. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/downloads/gdelinesteachgresfctsht.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 100. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 30.2. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

When hospitalists work in academic centers, medical and surgical services are furnished, in part, by a resident within the scope of the hospitalists’ training program. A resident is “an individual who participates in an approved graduate medical education (GME) program or a physician who is not in an approved GME program but who is authorized to practice only in a hospital setting.”1 Resident services are covered by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and paid by the Fiscal Intermediary through direct GME and Indirect Medical Education (IME) payments. These services are not billed or paid using the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The teaching physician is responsible for supervising the resident’s health-care delivery but is not paid for the resident’s work. The teaching physician is paid for their personal and medically necessary service in providing patient care. The teaching physician has the option to perform the entire service, or perform the self-determined critical or key portion(s) of the service.

Comprehensive Service

Teaching physicians independently see the patient and perform all required elements to support the visit level (e.g. 99233: subsequent hospital care, per day, which requires at least two of the following three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, or high-complexity medical decision-making).2 The teaching physician writes a note independent of a resident encounter with the patient or documentation. The teaching physician note “stands alone” and does not rely on the resident’s documentation. If the resident saw the patient and documented the encounter, the teaching physician might choose to “link to” the resident note in lieu of personally documenting the entire service. The linking statement must demonstrate teaching physician involvement in the patient encounter and participation in patient management. Use of CMS-approved statements is best to meet these requirements. Statement examples include:3

- “I performed a history and physical examination of the patient and discussed his management with the resident. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree with the documented findings and plan of care.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I agree with the findings and the plan of care as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw and examined the patient. I agree with the resident’s note, except the heart murmur is louder, so I will obtain an echo to evaluate.”

Each of these statements meets the minimum requirements for billing. However, teaching physicians should offer more information in support of other clinical, quality, and regulatory initiatives and mandates, better exemplified in the last example. The reported visit level will be supported by the combined documentation (teaching physician and resident).

The teaching physician submits a claim in their name and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99223-GC). This alerts the Medicare contractor that services were provided under teaching physician rules. Requests for documentation should include a response with medical record entries from the teaching physician and resident.

Critical/Key Portion

“Supervised” service: The resident and teaching physician can round together; they can see the patient at the same time. The teaching physician observes the resident’s performance during the patient encounter, or personally performs self-determined elements of patient care. The resident documents their patient care. The attending must still note their presence in the medical record, performance of the critical or key portions of the service, and involvement in patient management. CMS-accepted statements include:3

- “I was present with the resident during the history and exam. I discussed the case with the resident and agree with the findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw the patient with the resident and agree with the resident’s findings and plan.”

Although these statements demonstrate acceptable billing language, they lack patient-specific details that support the teaching physician’s personal contribution to patient care and the quality of their expertise. The teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99232-GC).

“Shared” service: The resident sees the patient unaccompanied and documents the corresponding care provided. The teaching physician sees the patient at a different time but performs only the critical or key portions of the service. The case is subsequently discussed with the resident. The teaching physician must document their presence and performance of the critical or key portions of the service, along with any patient management. Using CMS-quoted statements ensures regulatory compliance:3

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree, except that the picture is more consistent with pericarditis than myocardial ischemia. Will begin NSAIDs.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Discussed with resident and agree with resident’s findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “See resident’s note for details. I saw and evaluated the patient and agree with the resident’s finding and plans as written.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Agree with resident’s note, but lower extremities are weaker, now 3/5; MRI of L/S spine today.”

Once again, the teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99233-GC).

EHR Considerations

When seeing patients independent of one another, the timing of the teaching physician and resident encounters does not impact billing. However, the time that the resident encounter is documented in the medical record can significantly impact the payment when reviewed by external auditors. When the resident note is dated and timed later than the teaching physician’s entry, the teaching physician cannot consider the resident’s note for visit-level selection. The teaching physician should not “link to” a resident note that is viewed as “not having been written” prior to the teaching physician note. This would not fulfill the requirements represented in the CMS-approved language “I reviewed the resident’s note and agree.”

Electronic health record (EHR) systems sometimes hinder compliance. If the resident completes the note but does not “finalize” or “close” the encounter until after the teaching physician documents their own note, it can falsely appear that the resident note did not exist at the time the teaching physician created their entry. Because an auditor can only view the finalized entries, the timing of each entry might be erroneously represented. Proper training and closing of encounters can diminish these issues.

Additionally, scribing the attestation is not permitted. Residents cannot document the teaching physician attestation on behalf of the physician under any circumstance. CMS rules require the teaching physician to document their presence, participation, and management of the patient. In an EHR, the teaching physician must document this entry under his/her own log-in and password, which is not to be shared with anyone.

Students

CMS defines student as “an individual who participates in an accredited educational program [e.g. a medical school] that is not an approved GME program.”1 A student is not regarded as a “physician in training,” and the service is not eligible for reimbursement consideration under the teaching physician rules.

Per CMS guidelines, students can document services in the medical record, but the teaching physician may only refer to the student’s systems review and past/family/social history entries. The teaching physician must verify and redocument the history of present illness. A student’s physical exam findings or medical decision-making are not suitable for tethering, and the teaching physician must personally perform and redocument the physical exam and medical decision-making. The visit level reflects only the teaching physician’s personally performed and documented service.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Guidelines for Teaching Physicians, Interns, Residents. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/downloads/gdelinesteachgresfctsht.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 100. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 30.2. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

When hospitalists work in academic centers, medical and surgical services are furnished, in part, by a resident within the scope of the hospitalists’ training program. A resident is “an individual who participates in an approved graduate medical education (GME) program or a physician who is not in an approved GME program but who is authorized to practice only in a hospital setting.”1 Resident services are covered by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and paid by the Fiscal Intermediary through direct GME and Indirect Medical Education (IME) payments. These services are not billed or paid using the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The teaching physician is responsible for supervising the resident’s health-care delivery but is not paid for the resident’s work. The teaching physician is paid for their personal and medically necessary service in providing patient care. The teaching physician has the option to perform the entire service, or perform the self-determined critical or key portion(s) of the service.

Comprehensive Service

Teaching physicians independently see the patient and perform all required elements to support the visit level (e.g. 99233: subsequent hospital care, per day, which requires at least two of the following three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, or high-complexity medical decision-making).2 The teaching physician writes a note independent of a resident encounter with the patient or documentation. The teaching physician note “stands alone” and does not rely on the resident’s documentation. If the resident saw the patient and documented the encounter, the teaching physician might choose to “link to” the resident note in lieu of personally documenting the entire service. The linking statement must demonstrate teaching physician involvement in the patient encounter and participation in patient management. Use of CMS-approved statements is best to meet these requirements. Statement examples include:3

- “I performed a history and physical examination of the patient and discussed his management with the resident. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree with the documented findings and plan of care.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I agree with the findings and the plan of care as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw and examined the patient. I agree with the resident’s note, except the heart murmur is louder, so I will obtain an echo to evaluate.”

Each of these statements meets the minimum requirements for billing. However, teaching physicians should offer more information in support of other clinical, quality, and regulatory initiatives and mandates, better exemplified in the last example. The reported visit level will be supported by the combined documentation (teaching physician and resident).

The teaching physician submits a claim in their name and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99223-GC). This alerts the Medicare contractor that services were provided under teaching physician rules. Requests for documentation should include a response with medical record entries from the teaching physician and resident.

Critical/Key Portion

“Supervised” service: The resident and teaching physician can round together; they can see the patient at the same time. The teaching physician observes the resident’s performance during the patient encounter, or personally performs self-determined elements of patient care. The resident documents their patient care. The attending must still note their presence in the medical record, performance of the critical or key portions of the service, and involvement in patient management. CMS-accepted statements include:3

- “I was present with the resident during the history and exam. I discussed the case with the resident and agree with the findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw the patient with the resident and agree with the resident’s findings and plan.”

Although these statements demonstrate acceptable billing language, they lack patient-specific details that support the teaching physician’s personal contribution to patient care and the quality of their expertise. The teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99232-GC).

“Shared” service: The resident sees the patient unaccompanied and documents the corresponding care provided. The teaching physician sees the patient at a different time but performs only the critical or key portions of the service. The case is subsequently discussed with the resident. The teaching physician must document their presence and performance of the critical or key portions of the service, along with any patient management. Using CMS-quoted statements ensures regulatory compliance:3

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree, except that the picture is more consistent with pericarditis than myocardial ischemia. Will begin NSAIDs.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Discussed with resident and agree with resident’s findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “See resident’s note for details. I saw and evaluated the patient and agree with the resident’s finding and plans as written.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Agree with resident’s note, but lower extremities are weaker, now 3/5; MRI of L/S spine today.”

Once again, the teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99233-GC).

EHR Considerations

When seeing patients independent of one another, the timing of the teaching physician and resident encounters does not impact billing. However, the time that the resident encounter is documented in the medical record can significantly impact the payment when reviewed by external auditors. When the resident note is dated and timed later than the teaching physician’s entry, the teaching physician cannot consider the resident’s note for visit-level selection. The teaching physician should not “link to” a resident note that is viewed as “not having been written” prior to the teaching physician note. This would not fulfill the requirements represented in the CMS-approved language “I reviewed the resident’s note and agree.”

Electronic health record (EHR) systems sometimes hinder compliance. If the resident completes the note but does not “finalize” or “close” the encounter until after the teaching physician documents their own note, it can falsely appear that the resident note did not exist at the time the teaching physician created their entry. Because an auditor can only view the finalized entries, the timing of each entry might be erroneously represented. Proper training and closing of encounters can diminish these issues.

Additionally, scribing the attestation is not permitted. Residents cannot document the teaching physician attestation on behalf of the physician under any circumstance. CMS rules require the teaching physician to document their presence, participation, and management of the patient. In an EHR, the teaching physician must document this entry under his/her own log-in and password, which is not to be shared with anyone.

Students

CMS defines student as “an individual who participates in an accredited educational program [e.g. a medical school] that is not an approved GME program.”1 A student is not regarded as a “physician in training,” and the service is not eligible for reimbursement consideration under the teaching physician rules.

Per CMS guidelines, students can document services in the medical record, but the teaching physician may only refer to the student’s systems review and past/family/social history entries. The teaching physician must verify and redocument the history of present illness. A student’s physical exam findings or medical decision-making are not suitable for tethering, and the teaching physician must personally perform and redocument the physical exam and medical decision-making. The visit level reflects only the teaching physician’s personally performed and documented service.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Guidelines for Teaching Physicians, Interns, Residents. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/downloads/gdelinesteachgresfctsht.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 100. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 30.2. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Thirty-Day Hospital Readmissions Drop in 2012, CMS Reports

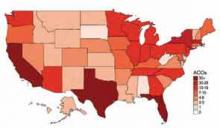

Rate of 30-day, all-cause hospital readmissions for the fourth quarter of 2012, per the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The figure had fluctuated between 18.5% and 19.5% the prior five years. The drop corresponds with the implementation of Medicare penalties for higher-than-expected readmission rates. Previous studies of readmissions, including the recent Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care report described in last month’s “Innovations” found little or no progress on reducing hospital readmissions.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Quinn K, Neeman N, Mourad M, Sliwka D. Communication coaching: A multifaceted intervention to improve physician-patient communication [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S108.

- Sokol PE, Wynia MK. There and Home Again, Safely: Five Responsibilities of Ambulatory Practices in High Quality Care Transitions. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/patient-safety/ambulatory-practices.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363.

- JAMA Internal Medicine. Nearly one-third of physicians report missing electronic notification of test results. JAMA Internal Medicine website. Available at: http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/nearly-one-third-of-physicians-report-missing-electronic-notification-of-test-results/.Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Miliard M. VA enlists telehealth for disasters. Healthcare IT News website. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/va-enlists-telehealth-disasters. Published February 27, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2013.

Rate of 30-day, all-cause hospital readmissions for the fourth quarter of 2012, per the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The figure had fluctuated between 18.5% and 19.5% the prior five years. The drop corresponds with the implementation of Medicare penalties for higher-than-expected readmission rates. Previous studies of readmissions, including the recent Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care report described in last month’s “Innovations” found little or no progress on reducing hospital readmissions.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Quinn K, Neeman N, Mourad M, Sliwka D. Communication coaching: A multifaceted intervention to improve physician-patient communication [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S108.

- Sokol PE, Wynia MK. There and Home Again, Safely: Five Responsibilities of Ambulatory Practices in High Quality Care Transitions. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/patient-safety/ambulatory-practices.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363.

- JAMA Internal Medicine. Nearly one-third of physicians report missing electronic notification of test results. JAMA Internal Medicine website. Available at: http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/nearly-one-third-of-physicians-report-missing-electronic-notification-of-test-results/.Accessed April 8, 2013.