User login

The Hospitalist only

HM16 Session Analysis: Infectious Disease Emergencies: Three Diagnoses You Can’t Afford to Miss

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

HM16 Session Analysis: ICD-10 Coding Tips

Presenter: Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM

Summary: With the implementation of ICD-10, correct and specific documentation to ensure proper patient diagnosis categorization has become increasingly important. Hospitalists are urged to understand the impact CDI has on quality and reimbursement.

Quality Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on quality reporting for mortality and complication rates, risk of mortality, as well as severity of illness. Documenting present on admission (POA) also directly impacts the hospital-acquired condition (HAC) classifications.

Reimbursement Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on expected length of stay, case mix index (CMI), cost reporting, and appropriate hospital reimbursement.

HM Takeaways:

- Be clear and specific.

- Document principle diagnosis and secondary diagnoses, and their associated interactions, are critically important.

- Ensure all diagnoses are a part of the discharge summary.

- Avoid saying “History of.”

- It’s OK to document “possible,” “probably,” “likely,” or “suspected.”

- Document “why” the patient has the diagnosis.

- List all differentials, and identify if ruled in or ruled out.

- Indicate acuity, even if obvious.

This presenter also reviewed common CDI opportunities in hospital medicine.

Note: This discussion was specific to the needs of the hospital patient diagnosis and billing, and not related to physician billing and CPT codes.

Presenter: Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM

Summary: With the implementation of ICD-10, correct and specific documentation to ensure proper patient diagnosis categorization has become increasingly important. Hospitalists are urged to understand the impact CDI has on quality and reimbursement.

Quality Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on quality reporting for mortality and complication rates, risk of mortality, as well as severity of illness. Documenting present on admission (POA) also directly impacts the hospital-acquired condition (HAC) classifications.

Reimbursement Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on expected length of stay, case mix index (CMI), cost reporting, and appropriate hospital reimbursement.

HM Takeaways:

- Be clear and specific.

- Document principle diagnosis and secondary diagnoses, and their associated interactions, are critically important.

- Ensure all diagnoses are a part of the discharge summary.

- Avoid saying “History of.”

- It’s OK to document “possible,” “probably,” “likely,” or “suspected.”

- Document “why” the patient has the diagnosis.

- List all differentials, and identify if ruled in or ruled out.

- Indicate acuity, even if obvious.

This presenter also reviewed common CDI opportunities in hospital medicine.

Note: This discussion was specific to the needs of the hospital patient diagnosis and billing, and not related to physician billing and CPT codes.

Presenter: Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM

Summary: With the implementation of ICD-10, correct and specific documentation to ensure proper patient diagnosis categorization has become increasingly important. Hospitalists are urged to understand the impact CDI has on quality and reimbursement.

Quality Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on quality reporting for mortality and complication rates, risk of mortality, as well as severity of illness. Documenting present on admission (POA) also directly impacts the hospital-acquired condition (HAC) classifications.

Reimbursement Impact: Documentation has a direct impact on expected length of stay, case mix index (CMI), cost reporting, and appropriate hospital reimbursement.

HM Takeaways:

- Be clear and specific.

- Document principle diagnosis and secondary diagnoses, and their associated interactions, are critically important.

- Ensure all diagnoses are a part of the discharge summary.

- Avoid saying “History of.”

- It’s OK to document “possible,” “probably,” “likely,” or “suspected.”

- Document “why” the patient has the diagnosis.

- List all differentials, and identify if ruled in or ruled out.

- Indicate acuity, even if obvious.

This presenter also reviewed common CDI opportunities in hospital medicine.

Note: This discussion was specific to the needs of the hospital patient diagnosis and billing, and not related to physician billing and CPT codes.

NPs, PAs Vital to Hospital Medicine

Yes, it’s time for another “year ahead” type column where the writer attempts to provide clarity on future events. What does “Hospital Medicine 2016” hold for us? I hope by the time Hospital Medicine 2017 rolls around, everyone will have forgotten the wrong predictions and only remember those that reveal my exceptional clairvoyance and prescient knowledge.

NP and PA Practice in Hospital Medicine Will Continue to Grow

Well, it doesn’t take a crystal ball or tarot cards to predict this. One only has to look at the data. The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report revealed that 51.7% of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs) in their practice. Two short years later, the survey showed 83% of HMGs reported having NPs and/or PAs in their groups. That is an astounding amount of growth in a short period of time, which brings me to my next prediction.

HMGs Will Have to Continue to Figure Out How to Hire and Deploy NPs and PAs in Sensible Ways

I know that statement is very controversial. Not. But the true work of utilizing NP and PA providers in hospitalist practice is not in the hiring; it’s how to use these providers in thoughtful, sensible, and cost-effective ways.

A group leader really needs to know and understand the drivers behind the need for these hires as well as understand the financial landscape in the hiring. Are you hiring an NP/PA because you want to reduce your provider workforce cost? Are you hiring to target quality outcomes in a specific patient population? Are you hiring to staff your observation unit, freeing up your physicians for higher-acuity work? Are you hiring to treat and improve physician burnout? Or is this the only carbon-based life form you can attract to the outer boroughs of your northern clime in the deepest, darkest days of January?

All these may or may not be good reasons, but understanding those variables will help you get the right person for the right reason and will help you evaluate the return on investment and the impact on practice.

Diversity Prevents Disease

Much like the potato monoculture of McDonald’s french fries increasing the risk of potato diseases, monoculture in your hospitalist group may breed burnout and bad attitudes. Diversity of experience, perspective, and skill set may inoculate your group, keeping the dreaded crispy coated from complaining about schedule, workload, or acuity or, worse yet, simply leaving.

I don’t have data to support this, but I have heard anecdotally from more than one HMG leader that the addition of NP/PA providers to physician teams has improved physician satisfaction. SHM obviously agrees with this philosophy, as they value and support the value of a “big tent” philosophy. This big tent includes all types of people who contribute to the culture of this organization, making it stronger, more nimble and innovative, and definitely more fun.

Diversity in providers can only have a positive impact on your organization’s culture.

Whatever the Reason You Hire Them, Get Ready for Change

Be prepared for evolution. You may have initially hired an NP or PA simply to do admissions or to see all of your orthopedic co-management patients. But over time, your practice is going to morph and evolve, hopefully, in positive ways. Bring your NP/PA colleagues along for the ride; pull up a chair to the table. They may be able to provide new direction, support, or service lines to your practice in ways you hadn’t considered.

NP/PA providers’ abilities and ambitions will change over time as well. Make sure that change goes both ways. You may find that their influence and impact on your organization’s productivity and growth go beyond their industry. Consider utilizing NP/PA providers in novel ways; maybe they have great onboarding skills, are fabulous at scheduling, or can look at a spreadsheet without going cross-eyed or bald.

Change is growth. And growth is good. Unless you would rather die.

HM Needs to Develop Innovative Care Models; NPs/PAs Provide a Platform for Innovation

Inpatient medicine is changing in a rapid and unpredictable way. Some of the necessity of that work is driven by financial incentives and quality indicators, but necessity is the biggest driver of all. People, patients, and providers are getting old (thank God it’s not just me). There simply are not enough physicians to care for our rapidly aging population, or if there are, they are all employed in sunny Southern California. How we respond to this threat or opportunity is one of our most important charges. We own the inpatient kingdom. We need to lead with benevolence and thoughtfulness. We need to really look ahead and identify new ways to manage the complexity of a system whose complexity continues to mutate like some avian virus. I can’t see a future without a crucial role played by my NP/PA brethren. Can we begin this conversation with the long view in mind and really begin to own this in a true and responsible way?

Thanks for your attention, and remember, in 2017 you will have forgotten all the ways, if any, that I was wrong. TH

Ms. Cardin is a nurse practitioner in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Chicago and is chair of SHM’s NP/PA Committee. She is a newly elected SHM board member.

Yes, it’s time for another “year ahead” type column where the writer attempts to provide clarity on future events. What does “Hospital Medicine 2016” hold for us? I hope by the time Hospital Medicine 2017 rolls around, everyone will have forgotten the wrong predictions and only remember those that reveal my exceptional clairvoyance and prescient knowledge.

NP and PA Practice in Hospital Medicine Will Continue to Grow

Well, it doesn’t take a crystal ball or tarot cards to predict this. One only has to look at the data. The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report revealed that 51.7% of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs) in their practice. Two short years later, the survey showed 83% of HMGs reported having NPs and/or PAs in their groups. That is an astounding amount of growth in a short period of time, which brings me to my next prediction.

HMGs Will Have to Continue to Figure Out How to Hire and Deploy NPs and PAs in Sensible Ways

I know that statement is very controversial. Not. But the true work of utilizing NP and PA providers in hospitalist practice is not in the hiring; it’s how to use these providers in thoughtful, sensible, and cost-effective ways.

A group leader really needs to know and understand the drivers behind the need for these hires as well as understand the financial landscape in the hiring. Are you hiring an NP/PA because you want to reduce your provider workforce cost? Are you hiring to target quality outcomes in a specific patient population? Are you hiring to staff your observation unit, freeing up your physicians for higher-acuity work? Are you hiring to treat and improve physician burnout? Or is this the only carbon-based life form you can attract to the outer boroughs of your northern clime in the deepest, darkest days of January?

All these may or may not be good reasons, but understanding those variables will help you get the right person for the right reason and will help you evaluate the return on investment and the impact on practice.

Diversity Prevents Disease

Much like the potato monoculture of McDonald’s french fries increasing the risk of potato diseases, monoculture in your hospitalist group may breed burnout and bad attitudes. Diversity of experience, perspective, and skill set may inoculate your group, keeping the dreaded crispy coated from complaining about schedule, workload, or acuity or, worse yet, simply leaving.

I don’t have data to support this, but I have heard anecdotally from more than one HMG leader that the addition of NP/PA providers to physician teams has improved physician satisfaction. SHM obviously agrees with this philosophy, as they value and support the value of a “big tent” philosophy. This big tent includes all types of people who contribute to the culture of this organization, making it stronger, more nimble and innovative, and definitely more fun.

Diversity in providers can only have a positive impact on your organization’s culture.

Whatever the Reason You Hire Them, Get Ready for Change

Be prepared for evolution. You may have initially hired an NP or PA simply to do admissions or to see all of your orthopedic co-management patients. But over time, your practice is going to morph and evolve, hopefully, in positive ways. Bring your NP/PA colleagues along for the ride; pull up a chair to the table. They may be able to provide new direction, support, or service lines to your practice in ways you hadn’t considered.

NP/PA providers’ abilities and ambitions will change over time as well. Make sure that change goes both ways. You may find that their influence and impact on your organization’s productivity and growth go beyond their industry. Consider utilizing NP/PA providers in novel ways; maybe they have great onboarding skills, are fabulous at scheduling, or can look at a spreadsheet without going cross-eyed or bald.

Change is growth. And growth is good. Unless you would rather die.

HM Needs to Develop Innovative Care Models; NPs/PAs Provide a Platform for Innovation

Inpatient medicine is changing in a rapid and unpredictable way. Some of the necessity of that work is driven by financial incentives and quality indicators, but necessity is the biggest driver of all. People, patients, and providers are getting old (thank God it’s not just me). There simply are not enough physicians to care for our rapidly aging population, or if there are, they are all employed in sunny Southern California. How we respond to this threat or opportunity is one of our most important charges. We own the inpatient kingdom. We need to lead with benevolence and thoughtfulness. We need to really look ahead and identify new ways to manage the complexity of a system whose complexity continues to mutate like some avian virus. I can’t see a future without a crucial role played by my NP/PA brethren. Can we begin this conversation with the long view in mind and really begin to own this in a true and responsible way?

Thanks for your attention, and remember, in 2017 you will have forgotten all the ways, if any, that I was wrong. TH

Ms. Cardin is a nurse practitioner in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Chicago and is chair of SHM’s NP/PA Committee. She is a newly elected SHM board member.

Yes, it’s time for another “year ahead” type column where the writer attempts to provide clarity on future events. What does “Hospital Medicine 2016” hold for us? I hope by the time Hospital Medicine 2017 rolls around, everyone will have forgotten the wrong predictions and only remember those that reveal my exceptional clairvoyance and prescient knowledge.

NP and PA Practice in Hospital Medicine Will Continue to Grow

Well, it doesn’t take a crystal ball or tarot cards to predict this. One only has to look at the data. The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report revealed that 51.7% of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs) in their practice. Two short years later, the survey showed 83% of HMGs reported having NPs and/or PAs in their groups. That is an astounding amount of growth in a short period of time, which brings me to my next prediction.

HMGs Will Have to Continue to Figure Out How to Hire and Deploy NPs and PAs in Sensible Ways

I know that statement is very controversial. Not. But the true work of utilizing NP and PA providers in hospitalist practice is not in the hiring; it’s how to use these providers in thoughtful, sensible, and cost-effective ways.

A group leader really needs to know and understand the drivers behind the need for these hires as well as understand the financial landscape in the hiring. Are you hiring an NP/PA because you want to reduce your provider workforce cost? Are you hiring to target quality outcomes in a specific patient population? Are you hiring to staff your observation unit, freeing up your physicians for higher-acuity work? Are you hiring to treat and improve physician burnout? Or is this the only carbon-based life form you can attract to the outer boroughs of your northern clime in the deepest, darkest days of January?

All these may or may not be good reasons, but understanding those variables will help you get the right person for the right reason and will help you evaluate the return on investment and the impact on practice.

Diversity Prevents Disease

Much like the potato monoculture of McDonald’s french fries increasing the risk of potato diseases, monoculture in your hospitalist group may breed burnout and bad attitudes. Diversity of experience, perspective, and skill set may inoculate your group, keeping the dreaded crispy coated from complaining about schedule, workload, or acuity or, worse yet, simply leaving.

I don’t have data to support this, but I have heard anecdotally from more than one HMG leader that the addition of NP/PA providers to physician teams has improved physician satisfaction. SHM obviously agrees with this philosophy, as they value and support the value of a “big tent” philosophy. This big tent includes all types of people who contribute to the culture of this organization, making it stronger, more nimble and innovative, and definitely more fun.

Diversity in providers can only have a positive impact on your organization’s culture.

Whatever the Reason You Hire Them, Get Ready for Change

Be prepared for evolution. You may have initially hired an NP or PA simply to do admissions or to see all of your orthopedic co-management patients. But over time, your practice is going to morph and evolve, hopefully, in positive ways. Bring your NP/PA colleagues along for the ride; pull up a chair to the table. They may be able to provide new direction, support, or service lines to your practice in ways you hadn’t considered.

NP/PA providers’ abilities and ambitions will change over time as well. Make sure that change goes both ways. You may find that their influence and impact on your organization’s productivity and growth go beyond their industry. Consider utilizing NP/PA providers in novel ways; maybe they have great onboarding skills, are fabulous at scheduling, or can look at a spreadsheet without going cross-eyed or bald.

Change is growth. And growth is good. Unless you would rather die.

HM Needs to Develop Innovative Care Models; NPs/PAs Provide a Platform for Innovation

Inpatient medicine is changing in a rapid and unpredictable way. Some of the necessity of that work is driven by financial incentives and quality indicators, but necessity is the biggest driver of all. People, patients, and providers are getting old (thank God it’s not just me). There simply are not enough physicians to care for our rapidly aging population, or if there are, they are all employed in sunny Southern California. How we respond to this threat or opportunity is one of our most important charges. We own the inpatient kingdom. We need to lead with benevolence and thoughtfulness. We need to really look ahead and identify new ways to manage the complexity of a system whose complexity continues to mutate like some avian virus. I can’t see a future without a crucial role played by my NP/PA brethren. Can we begin this conversation with the long view in mind and really begin to own this in a true and responsible way?

Thanks for your attention, and remember, in 2017 you will have forgotten all the ways, if any, that I was wrong. TH

Ms. Cardin is a nurse practitioner in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Chicago and is chair of SHM’s NP/PA Committee. She is a newly elected SHM board member.

CMS Introduces Billing Code for Hospitalists: What You Need to Know

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the approval of a dedicated specialty billing code for hospitalists that will soon be ready for official use. This is a monumental step for hospital medicine, which continues to be the fastest growing medical specialty in the U.S., with more than 48,000 practitioners identifying as hospitalists.

The Hospitalist recently discussed the implications of this decision with Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, chief strategy officer for IPC Healthcare and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee (PPC), and Josh Boswell, director of government relations at SHM, to answer questions raised by SHM members.

Question: What are the benefits to hospitalists using the code?

Dr. Greeno: As we transition from fee-for-service to quality-based payment models, using this code will become critical to ensure hospitalists are reimbursed and evaluated fairly. Under the current code structure, hospitalists are missing opportunities to be rewarded and may be penalized unnecessarily because they are required to identify with internal medicine, family medicine, or another specialty that most closely resembles their daily practice. What current measures do not account for is that hospitalists’ patients are inherently more complex than those seen by practitioners in these other—most often outpatient—specialties. We as hospitalists face unique challenges and work with patients from all demographics, often with severe illnesses, making it nearly impossible to rely on benchmarks used for these other specialties.

There are a few prime examples of this that illustrate the need for the new code. Under the current system, some quality-based patient satisfaction measures under MACRA, on which hospitalists are being evaluated, pertain to the outpatient setting, including waiting room quality and office staff–irrelevant measurements for hospitalists. Hospitalists are also often incorrectly penalized under meaningful use due to complications brought on by observation status and its classification as an outpatient stay. This can cause both quality and cost measures to be extremely flawed and can misrepresent the performance and cost of hospitalists and hospital medicine groups. In the current billing structure, there is no way to accurately identify hospitalists and enable a definite fix to these problems.

To get what we want (fair measurement using relevant metrics), we must be able to identify as a separate group, and fortunately, now we can. There will be benefits we don’t even know about yet. We have to wait and see how healthcare policy continues to evolve and change moving forward. What we do know is that having this code will help us shape MACRA and future healthcare policy so that it works better for hospitalists as the specialty continues to grow in scope and impact.

Q: When will the new code go into effect?

Boswell: While there is not a set date at this time, CMS has reported that it can take up to a year, mostly due to technical changes that need to be made within their own systems. The code has already been officially approved; we just need to wait a bit longer to actually use it.

Q: What happens to hospitalists if they do not use the code?

Dr. Greeno: Some hospitalists might be nervous about the change after having billed a certain way for so long. While there is no absolute requirement for hospitalists to use the new code, the bottom line is that if hospitalists do not adopt the new code, they risk not receiving fair evaluations. Using this code should provide hospitalists with greater insight into their own performance—the data will be much more accurate and meaningful. This will allow hospitalists to hone in on areas needing improvement and provide them with more confidence that they are being compared using accurate benchmarks.

I want to stress that hospitalists, or in some cases their hospital medicine groups, will need to physically change their specialty affiliation when the code becomes effective. Otherwise, they risk not reaping the benefits associated with the new code and will continue to be evaluated using less-than-optimal benchmarks. The ball is in their court to make the change when the code is available, and SHM will serve as a resource to help ensure they know what to do and when.

Q: Where can someone go to find the code? Will it be available on the CMS website?

Boswell: When the code does become available for use, it will be communicated through various channels at SHM and also through the Medicare Learning Network, the site that houses education, information, and resources for healthcare professionals. It will also likely be distributed through additional Medicare circulars and newsletters.

As more details from CMS become available, we will have more specific information to share with members, including information on our website, webinars with billing and coding experts, email communication, and more. Continue to watch your email and social media channels for the latest updates and information.

Q: What role did SHM play in bringing this code to fruition?

Boswell: We can say with confidence that this effort was driven entirely by SHM. To start, a formal application needs to be filed in order for a code to even be considered. After determining that the benefits associated with this code far outweighed the costs and then receiving the support of our board of directors, SHM’s staff and PPC members collaborated to draft a brief and made the argument for the addition of a hospitalist billing code based on the individual elements CMS requires for consideration.

Due to the fact hospital medicine doesn’t have a board certification, while solid, our argument was far from a slam dunk. After submitting the application, SHM continuously followed up with and pressured CMS through various channels and utilized our grassroots network of hospitalists on the Hill to put this code on legislators’ radars—the result was pressure getting applied from interested members of Congress as well. If it weren’t for the persistent advocacy efforts of SHM and its members over the past several years, this code would not have even been considered, let alone approved.

This is a significant development—to our knowledge, this is the first medical specialty to be granted a code without also having a board certification. We’re thrilled that what we have been advocating for on behalf of our members is now a reality!

For the latest information on the new hospitalist billing code and other important healthcare policy updates, continue to check for SHM emails and follow SHM’s social media channels, including @SHMLive and @SHMAdvocacy on Twitter.

Sign up for the network to get the latest news in healthcare policy and discover opportunities to advocate for yourself and fellow hospitalists. TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications coordinator.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the approval of a dedicated specialty billing code for hospitalists that will soon be ready for official use. This is a monumental step for hospital medicine, which continues to be the fastest growing medical specialty in the U.S., with more than 48,000 practitioners identifying as hospitalists.

The Hospitalist recently discussed the implications of this decision with Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, chief strategy officer for IPC Healthcare and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee (PPC), and Josh Boswell, director of government relations at SHM, to answer questions raised by SHM members.

Question: What are the benefits to hospitalists using the code?

Dr. Greeno: As we transition from fee-for-service to quality-based payment models, using this code will become critical to ensure hospitalists are reimbursed and evaluated fairly. Under the current code structure, hospitalists are missing opportunities to be rewarded and may be penalized unnecessarily because they are required to identify with internal medicine, family medicine, or another specialty that most closely resembles their daily practice. What current measures do not account for is that hospitalists’ patients are inherently more complex than those seen by practitioners in these other—most often outpatient—specialties. We as hospitalists face unique challenges and work with patients from all demographics, often with severe illnesses, making it nearly impossible to rely on benchmarks used for these other specialties.

There are a few prime examples of this that illustrate the need for the new code. Under the current system, some quality-based patient satisfaction measures under MACRA, on which hospitalists are being evaluated, pertain to the outpatient setting, including waiting room quality and office staff–irrelevant measurements for hospitalists. Hospitalists are also often incorrectly penalized under meaningful use due to complications brought on by observation status and its classification as an outpatient stay. This can cause both quality and cost measures to be extremely flawed and can misrepresent the performance and cost of hospitalists and hospital medicine groups. In the current billing structure, there is no way to accurately identify hospitalists and enable a definite fix to these problems.

To get what we want (fair measurement using relevant metrics), we must be able to identify as a separate group, and fortunately, now we can. There will be benefits we don’t even know about yet. We have to wait and see how healthcare policy continues to evolve and change moving forward. What we do know is that having this code will help us shape MACRA and future healthcare policy so that it works better for hospitalists as the specialty continues to grow in scope and impact.

Q: When will the new code go into effect?

Boswell: While there is not a set date at this time, CMS has reported that it can take up to a year, mostly due to technical changes that need to be made within their own systems. The code has already been officially approved; we just need to wait a bit longer to actually use it.

Q: What happens to hospitalists if they do not use the code?

Dr. Greeno: Some hospitalists might be nervous about the change after having billed a certain way for so long. While there is no absolute requirement for hospitalists to use the new code, the bottom line is that if hospitalists do not adopt the new code, they risk not receiving fair evaluations. Using this code should provide hospitalists with greater insight into their own performance—the data will be much more accurate and meaningful. This will allow hospitalists to hone in on areas needing improvement and provide them with more confidence that they are being compared using accurate benchmarks.

I want to stress that hospitalists, or in some cases their hospital medicine groups, will need to physically change their specialty affiliation when the code becomes effective. Otherwise, they risk not reaping the benefits associated with the new code and will continue to be evaluated using less-than-optimal benchmarks. The ball is in their court to make the change when the code is available, and SHM will serve as a resource to help ensure they know what to do and when.

Q: Where can someone go to find the code? Will it be available on the CMS website?

Boswell: When the code does become available for use, it will be communicated through various channels at SHM and also through the Medicare Learning Network, the site that houses education, information, and resources for healthcare professionals. It will also likely be distributed through additional Medicare circulars and newsletters.

As more details from CMS become available, we will have more specific information to share with members, including information on our website, webinars with billing and coding experts, email communication, and more. Continue to watch your email and social media channels for the latest updates and information.

Q: What role did SHM play in bringing this code to fruition?

Boswell: We can say with confidence that this effort was driven entirely by SHM. To start, a formal application needs to be filed in order for a code to even be considered. After determining that the benefits associated with this code far outweighed the costs and then receiving the support of our board of directors, SHM’s staff and PPC members collaborated to draft a brief and made the argument for the addition of a hospitalist billing code based on the individual elements CMS requires for consideration.

Due to the fact hospital medicine doesn’t have a board certification, while solid, our argument was far from a slam dunk. After submitting the application, SHM continuously followed up with and pressured CMS through various channels and utilized our grassroots network of hospitalists on the Hill to put this code on legislators’ radars—the result was pressure getting applied from interested members of Congress as well. If it weren’t for the persistent advocacy efforts of SHM and its members over the past several years, this code would not have even been considered, let alone approved.

This is a significant development—to our knowledge, this is the first medical specialty to be granted a code without also having a board certification. We’re thrilled that what we have been advocating for on behalf of our members is now a reality!

For the latest information on the new hospitalist billing code and other important healthcare policy updates, continue to check for SHM emails and follow SHM’s social media channels, including @SHMLive and @SHMAdvocacy on Twitter.

Sign up for the network to get the latest news in healthcare policy and discover opportunities to advocate for yourself and fellow hospitalists. TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications coordinator.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced the approval of a dedicated specialty billing code for hospitalists that will soon be ready for official use. This is a monumental step for hospital medicine, which continues to be the fastest growing medical specialty in the U.S., with more than 48,000 practitioners identifying as hospitalists.

The Hospitalist recently discussed the implications of this decision with Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, chief strategy officer for IPC Healthcare and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee (PPC), and Josh Boswell, director of government relations at SHM, to answer questions raised by SHM members.

Question: What are the benefits to hospitalists using the code?

Dr. Greeno: As we transition from fee-for-service to quality-based payment models, using this code will become critical to ensure hospitalists are reimbursed and evaluated fairly. Under the current code structure, hospitalists are missing opportunities to be rewarded and may be penalized unnecessarily because they are required to identify with internal medicine, family medicine, or another specialty that most closely resembles their daily practice. What current measures do not account for is that hospitalists’ patients are inherently more complex than those seen by practitioners in these other—most often outpatient—specialties. We as hospitalists face unique challenges and work with patients from all demographics, often with severe illnesses, making it nearly impossible to rely on benchmarks used for these other specialties.

There are a few prime examples of this that illustrate the need for the new code. Under the current system, some quality-based patient satisfaction measures under MACRA, on which hospitalists are being evaluated, pertain to the outpatient setting, including waiting room quality and office staff–irrelevant measurements for hospitalists. Hospitalists are also often incorrectly penalized under meaningful use due to complications brought on by observation status and its classification as an outpatient stay. This can cause both quality and cost measures to be extremely flawed and can misrepresent the performance and cost of hospitalists and hospital medicine groups. In the current billing structure, there is no way to accurately identify hospitalists and enable a definite fix to these problems.

To get what we want (fair measurement using relevant metrics), we must be able to identify as a separate group, and fortunately, now we can. There will be benefits we don’t even know about yet. We have to wait and see how healthcare policy continues to evolve and change moving forward. What we do know is that having this code will help us shape MACRA and future healthcare policy so that it works better for hospitalists as the specialty continues to grow in scope and impact.

Q: When will the new code go into effect?

Boswell: While there is not a set date at this time, CMS has reported that it can take up to a year, mostly due to technical changes that need to be made within their own systems. The code has already been officially approved; we just need to wait a bit longer to actually use it.

Q: What happens to hospitalists if they do not use the code?

Dr. Greeno: Some hospitalists might be nervous about the change after having billed a certain way for so long. While there is no absolute requirement for hospitalists to use the new code, the bottom line is that if hospitalists do not adopt the new code, they risk not receiving fair evaluations. Using this code should provide hospitalists with greater insight into their own performance—the data will be much more accurate and meaningful. This will allow hospitalists to hone in on areas needing improvement and provide them with more confidence that they are being compared using accurate benchmarks.

I want to stress that hospitalists, or in some cases their hospital medicine groups, will need to physically change their specialty affiliation when the code becomes effective. Otherwise, they risk not reaping the benefits associated with the new code and will continue to be evaluated using less-than-optimal benchmarks. The ball is in their court to make the change when the code is available, and SHM will serve as a resource to help ensure they know what to do and when.

Q: Where can someone go to find the code? Will it be available on the CMS website?

Boswell: When the code does become available for use, it will be communicated through various channels at SHM and also through the Medicare Learning Network, the site that houses education, information, and resources for healthcare professionals. It will also likely be distributed through additional Medicare circulars and newsletters.

As more details from CMS become available, we will have more specific information to share with members, including information on our website, webinars with billing and coding experts, email communication, and more. Continue to watch your email and social media channels for the latest updates and information.

Q: What role did SHM play in bringing this code to fruition?

Boswell: We can say with confidence that this effort was driven entirely by SHM. To start, a formal application needs to be filed in order for a code to even be considered. After determining that the benefits associated with this code far outweighed the costs and then receiving the support of our board of directors, SHM’s staff and PPC members collaborated to draft a brief and made the argument for the addition of a hospitalist billing code based on the individual elements CMS requires for consideration.

Due to the fact hospital medicine doesn’t have a board certification, while solid, our argument was far from a slam dunk. After submitting the application, SHM continuously followed up with and pressured CMS through various channels and utilized our grassroots network of hospitalists on the Hill to put this code on legislators’ radars—the result was pressure getting applied from interested members of Congress as well. If it weren’t for the persistent advocacy efforts of SHM and its members over the past several years, this code would not have even been considered, let alone approved.

This is a significant development—to our knowledge, this is the first medical specialty to be granted a code without also having a board certification. We’re thrilled that what we have been advocating for on behalf of our members is now a reality!

For the latest information on the new hospitalist billing code and other important healthcare policy updates, continue to check for SHM emails and follow SHM’s social media channels, including @SHMLive and @SHMAdvocacy on Twitter.

Sign up for the network to get the latest news in healthcare policy and discover opportunities to advocate for yourself and fellow hospitalists. TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications coordinator.

A Closer Look at Characteristics of High-Performing HM Groups

Early in 2015, SHM published the updated edition of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group,” which is a free download via the SHM website. Every hospitalist group should use this comprehensive list of attributes as one important frame of reference to guide ongoing improvement efforts and long-range planning.

In this column and the next two, I’ll split the difference between the very brief list of top success factors for hospitalist groups I wrote about in my March 2011 column and the very comprehensive “Key Characteristics” document. I think these attributes are among the most important to support a high-performing group, yet they are sometimes overlooked or implemented poorly. They are of roughly equal importance and are listed in no particular order.

Deliberately Cultivating a Culture (or Mindset) of Practice Ownership

It’s easy for hospitalists to think of themselves as employees who just work shifts but have no need or opportunity to attend to the bigger picture of the practice or the hospital in which they operate. After all, being a good doctor for your patients is an awfully big job itself, and lots of recruitment ads tell you doctoring is all that will be expected of you. Someone else will handle everything necessary to ensure your practice is successful.

This line of thinking will limit the success of your group.

Your group will perform much better and you’re likely to find your career much more rewarding if you and your hospitalist colleagues think of yourselves as owning your practice and take an active role in managing it. You’ll still need others to manage day-to-day business affairs, but at least a portion of the hospitalists in the group should be actively involved in planning and making decisions about the group’s operations and future evolution.

I encounter hospitalist groups that have become convinced they don’t even have the opportunity to shape or influence their practice. “No one ever listens,” they say. “The hospital executives just do what they want regardless of what we say.” But in nearly every case, that is an exaggeration. Most administrative leaders desperately want hospitalist engagement and thoughtful participation in planning and decision making.

I wrote additional thoughts about the importance of a culture, or mindset, of practice ownership in August 2008. The print version of that column included a short list of questions you could ask yourself to assess whether your own group has such a culture, but it is missing from the web version and can be found at nelsonflores.com/html/quiz.html.

A Formal System of Group ‘Governance’

So many hospitalist groups rely almost entirely on consensus to make decisions. This might work well enough for a very small group (e.g., four or five doctors), but for large groups, it means just one or two dissenters can block a decision and nothing much gets done.

Disagreements about practice operations and future direction are common, so every group should commit to writing some method of how votes will be taken in the absence of consensus. For example, the group might be divided about whether to adopt unit-based assignments or change the hours of an evening (“swing”) shift, and a formal vote might be the only way to make a decision. It’s best if you have decided in advance issues such as what constitutes a quorum, who is eligible to vote, and whether the winning vote requires a simple or super-majority. And a formalized system of voting helps support a culture ownership.

I wrote about this originally in December 2007 and provided sample bylaws your group could modify as needed. Of course, you should keep in mind that if you are indeed employed by a larger entity such as a hospital or staffing company, you don’t have the ability to make all decisions by a vote of the group. Pay raises, staff additions, and similar decisions require support of the employer, and while a vote in support of them might influence what actually happens, it still requires the support of the employer. But there are lots of things, like the work schedule, system of allocating patients across providers, etc., that are usually best made by the group itself, and sometimes they might come down to a vote of the group.

Never Stop Recruiting and Ensure Hospitalists Themselves Are Actively Engaged in Recruiting

I wrote about recruiting originally in July 2008 when there was a shortage of hospitalists everywhere. Since then, the supply of doctors seeking work as a hospitalist has caught up with demand in many major metropolitan areas like Minneapolis and Washington, D.C.

But outside of large markets—that is, in most of the country—demand for hospitalists still far exceeds supply, and groups face ongoing staffing deficits that come with the need for existing doctors to work extra shifts and use locum tenens or other forms of temporary staffing. The potential excess supply of hospitalists in major markets may eventually trickle out and ease the shortages elsewhere, but that hasn’t happened in a big way yet. So for these places, it is crucial to devote a lot of energy and resources to recruiting.

A vital component of successful recruiting is participation in the effort by the hospitalists themselves. I think the best mindset for the hospitalists is to think of themselves as leading recruitment efforts assisted by recruiters rather than the other way around. For example, the lead hospitalist or some other designated doctor should try to respond by phone (if that’s impractical, then respond by email) to every reasonable inquiry from a new candidate within 24 hours and serve as the candidate’s principle point of communication throughout the recruitment process. The recruiter can handle details of things like arranging travel for an interview, but a hospitalist in the group should be the main source of information regarding things like the work schedule, patient volume, compensation, etc. And a hospitalist should serve as the main host during a candidate’s on-site interview.

More to Come …

Next month, I’ll address things like a written policy and procedure manual, clear reporting relationships for the hospitalist group, and roles for advanced practice clinicians (NPs and PAs). TH

Early in 2015, SHM published the updated edition of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group,” which is a free download via the SHM website. Every hospitalist group should use this comprehensive list of attributes as one important frame of reference to guide ongoing improvement efforts and long-range planning.

In this column and the next two, I’ll split the difference between the very brief list of top success factors for hospitalist groups I wrote about in my March 2011 column and the very comprehensive “Key Characteristics” document. I think these attributes are among the most important to support a high-performing group, yet they are sometimes overlooked or implemented poorly. They are of roughly equal importance and are listed in no particular order.

Deliberately Cultivating a Culture (or Mindset) of Practice Ownership

It’s easy for hospitalists to think of themselves as employees who just work shifts but have no need or opportunity to attend to the bigger picture of the practice or the hospital in which they operate. After all, being a good doctor for your patients is an awfully big job itself, and lots of recruitment ads tell you doctoring is all that will be expected of you. Someone else will handle everything necessary to ensure your practice is successful.

This line of thinking will limit the success of your group.

Your group will perform much better and you’re likely to find your career much more rewarding if you and your hospitalist colleagues think of yourselves as owning your practice and take an active role in managing it. You’ll still need others to manage day-to-day business affairs, but at least a portion of the hospitalists in the group should be actively involved in planning and making decisions about the group’s operations and future evolution.

I encounter hospitalist groups that have become convinced they don’t even have the opportunity to shape or influence their practice. “No one ever listens,” they say. “The hospital executives just do what they want regardless of what we say.” But in nearly every case, that is an exaggeration. Most administrative leaders desperately want hospitalist engagement and thoughtful participation in planning and decision making.

I wrote additional thoughts about the importance of a culture, or mindset, of practice ownership in August 2008. The print version of that column included a short list of questions you could ask yourself to assess whether your own group has such a culture, but it is missing from the web version and can be found at nelsonflores.com/html/quiz.html.

A Formal System of Group ‘Governance’

So many hospitalist groups rely almost entirely on consensus to make decisions. This might work well enough for a very small group (e.g., four or five doctors), but for large groups, it means just one or two dissenters can block a decision and nothing much gets done.

Disagreements about practice operations and future direction are common, so every group should commit to writing some method of how votes will be taken in the absence of consensus. For example, the group might be divided about whether to adopt unit-based assignments or change the hours of an evening (“swing”) shift, and a formal vote might be the only way to make a decision. It’s best if you have decided in advance issues such as what constitutes a quorum, who is eligible to vote, and whether the winning vote requires a simple or super-majority. And a formalized system of voting helps support a culture ownership.

I wrote about this originally in December 2007 and provided sample bylaws your group could modify as needed. Of course, you should keep in mind that if you are indeed employed by a larger entity such as a hospital or staffing company, you don’t have the ability to make all decisions by a vote of the group. Pay raises, staff additions, and similar decisions require support of the employer, and while a vote in support of them might influence what actually happens, it still requires the support of the employer. But there are lots of things, like the work schedule, system of allocating patients across providers, etc., that are usually best made by the group itself, and sometimes they might come down to a vote of the group.

Never Stop Recruiting and Ensure Hospitalists Themselves Are Actively Engaged in Recruiting

I wrote about recruiting originally in July 2008 when there was a shortage of hospitalists everywhere. Since then, the supply of doctors seeking work as a hospitalist has caught up with demand in many major metropolitan areas like Minneapolis and Washington, D.C.

But outside of large markets—that is, in most of the country—demand for hospitalists still far exceeds supply, and groups face ongoing staffing deficits that come with the need for existing doctors to work extra shifts and use locum tenens or other forms of temporary staffing. The potential excess supply of hospitalists in major markets may eventually trickle out and ease the shortages elsewhere, but that hasn’t happened in a big way yet. So for these places, it is crucial to devote a lot of energy and resources to recruiting.

A vital component of successful recruiting is participation in the effort by the hospitalists themselves. I think the best mindset for the hospitalists is to think of themselves as leading recruitment efforts assisted by recruiters rather than the other way around. For example, the lead hospitalist or some other designated doctor should try to respond by phone (if that’s impractical, then respond by email) to every reasonable inquiry from a new candidate within 24 hours and serve as the candidate’s principle point of communication throughout the recruitment process. The recruiter can handle details of things like arranging travel for an interview, but a hospitalist in the group should be the main source of information regarding things like the work schedule, patient volume, compensation, etc. And a hospitalist should serve as the main host during a candidate’s on-site interview.

More to Come …

Next month, I’ll address things like a written policy and procedure manual, clear reporting relationships for the hospitalist group, and roles for advanced practice clinicians (NPs and PAs). TH

Early in 2015, SHM published the updated edition of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group,” which is a free download via the SHM website. Every hospitalist group should use this comprehensive list of attributes as one important frame of reference to guide ongoing improvement efforts and long-range planning.

In this column and the next two, I’ll split the difference between the very brief list of top success factors for hospitalist groups I wrote about in my March 2011 column and the very comprehensive “Key Characteristics” document. I think these attributes are among the most important to support a high-performing group, yet they are sometimes overlooked or implemented poorly. They are of roughly equal importance and are listed in no particular order.

Deliberately Cultivating a Culture (or Mindset) of Practice Ownership

It’s easy for hospitalists to think of themselves as employees who just work shifts but have no need or opportunity to attend to the bigger picture of the practice or the hospital in which they operate. After all, being a good doctor for your patients is an awfully big job itself, and lots of recruitment ads tell you doctoring is all that will be expected of you. Someone else will handle everything necessary to ensure your practice is successful.

This line of thinking will limit the success of your group.

Your group will perform much better and you’re likely to find your career much more rewarding if you and your hospitalist colleagues think of yourselves as owning your practice and take an active role in managing it. You’ll still need others to manage day-to-day business affairs, but at least a portion of the hospitalists in the group should be actively involved in planning and making decisions about the group’s operations and future evolution.

I encounter hospitalist groups that have become convinced they don’t even have the opportunity to shape or influence their practice. “No one ever listens,” they say. “The hospital executives just do what they want regardless of what we say.” But in nearly every case, that is an exaggeration. Most administrative leaders desperately want hospitalist engagement and thoughtful participation in planning and decision making.

I wrote additional thoughts about the importance of a culture, or mindset, of practice ownership in August 2008. The print version of that column included a short list of questions you could ask yourself to assess whether your own group has such a culture, but it is missing from the web version and can be found at nelsonflores.com/html/quiz.html.

A Formal System of Group ‘Governance’

So many hospitalist groups rely almost entirely on consensus to make decisions. This might work well enough for a very small group (e.g., four or five doctors), but for large groups, it means just one or two dissenters can block a decision and nothing much gets done.

Disagreements about practice operations and future direction are common, so every group should commit to writing some method of how votes will be taken in the absence of consensus. For example, the group might be divided about whether to adopt unit-based assignments or change the hours of an evening (“swing”) shift, and a formal vote might be the only way to make a decision. It’s best if you have decided in advance issues such as what constitutes a quorum, who is eligible to vote, and whether the winning vote requires a simple or super-majority. And a formalized system of voting helps support a culture ownership.

I wrote about this originally in December 2007 and provided sample bylaws your group could modify as needed. Of course, you should keep in mind that if you are indeed employed by a larger entity such as a hospital or staffing company, you don’t have the ability to make all decisions by a vote of the group. Pay raises, staff additions, and similar decisions require support of the employer, and while a vote in support of them might influence what actually happens, it still requires the support of the employer. But there are lots of things, like the work schedule, system of allocating patients across providers, etc., that are usually best made by the group itself, and sometimes they might come down to a vote of the group.

Never Stop Recruiting and Ensure Hospitalists Themselves Are Actively Engaged in Recruiting

I wrote about recruiting originally in July 2008 when there was a shortage of hospitalists everywhere. Since then, the supply of doctors seeking work as a hospitalist has caught up with demand in many major metropolitan areas like Minneapolis and Washington, D.C.

But outside of large markets—that is, in most of the country—demand for hospitalists still far exceeds supply, and groups face ongoing staffing deficits that come with the need for existing doctors to work extra shifts and use locum tenens or other forms of temporary staffing. The potential excess supply of hospitalists in major markets may eventually trickle out and ease the shortages elsewhere, but that hasn’t happened in a big way yet. So for these places, it is crucial to devote a lot of energy and resources to recruiting.

A vital component of successful recruiting is participation in the effort by the hospitalists themselves. I think the best mindset for the hospitalists is to think of themselves as leading recruitment efforts assisted by recruiters rather than the other way around. For example, the lead hospitalist or some other designated doctor should try to respond by phone (if that’s impractical, then respond by email) to every reasonable inquiry from a new candidate within 24 hours and serve as the candidate’s principle point of communication throughout the recruitment process. The recruiter can handle details of things like arranging travel for an interview, but a hospitalist in the group should be the main source of information regarding things like the work schedule, patient volume, compensation, etc. And a hospitalist should serve as the main host during a candidate’s on-site interview.

More to Come …

Next month, I’ll address things like a written policy and procedure manual, clear reporting relationships for the hospitalist group, and roles for advanced practice clinicians (NPs and PAs). TH

Key Elements of Critical Care

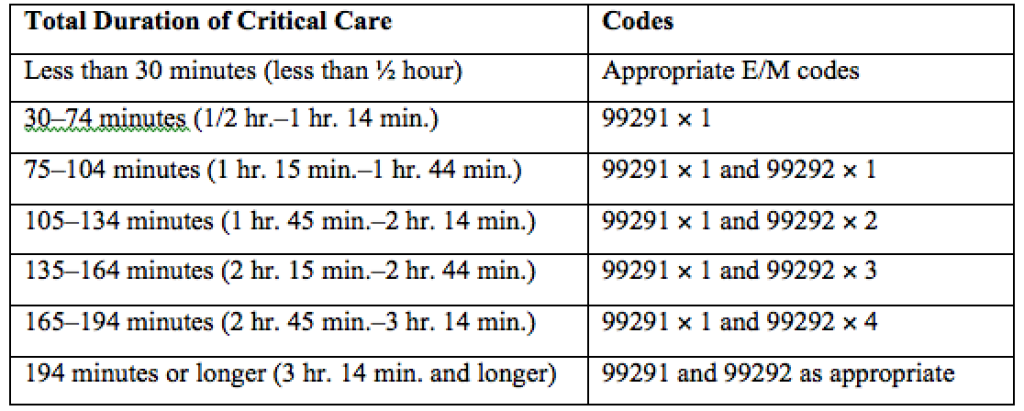

Code 99291 is used for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, first 30–74 minutes.1 It is to be reported only once per day per physician or group member of the same specialty.

Code 99292 is for critical care, evaluation, and management of the critically ill or critically injured patient, each additional 30 minutes. It is to be listed separately in addition to the code for primary service.1 Code 99292 is categorized as an add-on code. It must be reported on the same invoice as its primary code, 99291. Multiple units of code 99292 can be reported per day per physician/group.

Despite the increased resources and references for critical care billing, critical care reporting issues persist. Medicare data analysis continues to identify 99291 as high risk for claim payment errors, perpetuating prepayment claim edits for outlier utilization and location discrepancies (i.e., settings other than inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or the emergency department). 2,3,4

Bolster your documentation with these three key elements.

Critical Illness, Injury Management

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g., central nervous system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).5

Hospitalists providing care to the critically ill patient must perform highly complex decision making and interventions of high intensity that are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline. CMS further elaborates that “the patient shall be critically ill or injured at the time of the physician’s visit.”6 This is to ensure that hospitalists and other specialists support the medical necessity of the service and do not continue to report critical care codes on days after the patient has become stable and improved.

Consider the following scenarios:

CMS examples of patients whose medical condition may warrant critical care services (99291, 99292):6

- An 81-year-old male patient is admitted to the ICU following abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Two days after surgery, he requires fluids and pressors to maintain adequate perfusion and arterial pressures. He remains ventilator dependent.

- A 67-year-old female patient is three days post mitral valve repair. She develops petechiae, hypotension, and hypoxia requiring respiratory and circulatory support.

- A 70-year-old admitted for right lower lobe pneumococcal pneumonia with a history of COPD becomes hypoxic and hypotensive two days after admission.

- A 68-year-old admitted for an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction continues to have symptomatic ventricular tachycardia that is marginally responsive to antiarrhythmic therapy.

CMS examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical necessity criteria, or do not meet critical care criteria, or who do not have a critical care illness or injury and, therefore, are not eligible for critical care payment but may be reported using another appropriate hospital care code, such as subsequent hospital care codes (99231–99233), initial hospital care codes (99221–99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251–99255) when applicable:1,6

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g., drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g., insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical care unit; and

- Patients receiving only care of a chronic illness in absence of care for a critical illness (e.g., daily management of a chronic ventilator patient, management of or care related to dialysis for end-stage renal disease). Services considered palliative in nature as this type of care do not meet the definition of critical care services.7

Concurrent Care

Critically ill patients often require the care of hospitalists and other specialists throughout the course of treatment. Payors are sensitive to the multiple hours billed by multiple providers for a single patient on a given day. Claim logic provides an automated response to only allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical care hours as long as they are caring for a condition that meets the definition of critical care.

The CMS example of this: A dermatologist evaluates and treats a rash on an ICU patient who is maintained on a ventilator and nitroglycerine infusion that are being managed by an intensivist. The dermatologist should not report a service for critical care.6

Similarly for hospitalists, if an intensivist is taking care of the critical condition and there is nothing more for the hospitalist to add to the plan of care for the critical condition, critical care services may not be justified.

When different specialists are reporting critical care on the same day, it is imperative for the documentation to demonstrate that care is not duplicative of any other provider’s care (i.e., identify management of different conditions or revising elements of the plan). The care cannot overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical care services.

Calculating Time

Critical care time constitutes bedside time and time spent on the patient’s unit/floor where the physician is immediately available to the patient (see Table 1). Certain labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures are considered inherent to critical care services and are not reported separately on the claim form: cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562); chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020); pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); blood gases and interpretation of data stored in computers, such as ECGs, blood pressures, and hematologic data (99090); gastric intubation (43752, 43753); temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953); ventilation management (94002–94004, 94660, 94662); and vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).1

Instead, physician time associated with the performance and/or interpretation of these services is toward the cumulative critical care time of the day. Services or procedures that are considered separately billable (e.g., central line placement, intubation, CPR) cannot contribute to critical care time.

When separately billable procedures are performed by the same provider/specialty group on the same day as critical care, physicians should make a notation in the medical record indicating the non-overlapping service times (e.g., “central line insertion is not included as critical care time”). This may assist with securing reimbursement when the payor requests the documentation for each reported claim item.

Activities on the floor/unit that do not directly contribute to patient care or management (e.g., review of literature, teaching rounds) cannot be counted toward critical care time. Do not count time associated with indirect care provided outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g., reviewing data or calling the family from the office) toward critical care time.

Family discussions can be counted toward critical care time but must take place at bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate in the discussion unless medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. If unable to participate, a notation in the chart must delineate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason.

Credited time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or limitation(s) of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.1,7 Do not count time associated with providing periodic condition updates to the family, answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision making, or counseling the family during their grief process. If the conversation must take place via phone, it may be counted toward critical care time if the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.10

Physicians should keep track of their critical care time throughout the day. Since critical care time is a cumulative service, each entry should include the total time that critical care services were provided (e.g., 45 minutes).10 Some payors may still impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g., 2–2:50 a.m.).

Same-specialty physicians (i.e., two hospitalists from the same group practice) may require separate claims. The initial critical care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. The physician performing the additional time, beyond the first hour, reports the appropriate units of 99292 (see Table 1) under the corresponding NPI.11

CMS has issued instructions for contractors to recognize this atypical reporting method. However, non-Medicare payors may not recognize this newer reporting method and maintain that the cumulative service (by the same-specialty physician in the same provider group) should be reported under one physician name. Be sure to query the payors for appropriate reporting methods. TH

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Crosslin, R. Current Procedural Terminology 2015 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2014. 23-25.

- Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba website. Available at: www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care CPT 99291 widespread prepayment targeted review results. Cahaba website. Available at: https://www.cahabagba.com/news/critical-care-cpt-99291-widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-results-2/. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options, Inc. website. Available at: medicare.fcso.com/Publications_B/2013/251608.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Critical care fact sheet. CGS Administrators, LLC website. Available at: www.cgsmedicare.com/partb/mr/pdf/critical_care_fact_sheet.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Same day same service policy. United Healthcare website. Available at: www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Main%20Menu/Tools%20&%20Resources/Policies%20and%20Protocols/Medicare%20Advantage%20Reimbursement%20Policies/S/SameDaySameService.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Medicare claims processing manual: chapter 12, section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2015.