User login

The Hospitalist only

NAM offers recommendations to fight clinician burnout

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

WASHINGTON – a condition now estimated to affect a third to a half of clinicians in the United States, according to a report from an influential federal panel.

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) on Oct. 23 released a report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being.” The report calls for a broad and unified approach to tackling the root causes of burnout.

There must be a concerted effort by leaders of many fields of health care to create less stressful workplaces for clinicians, Pascale Carayon, PhD, cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the NAM press event.

“This is not an easy process,” said Dr. Carayon, a researcher into patient safety issues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “There is no single solution.”

The NAM report assigns specific tasks to many different participants in health care through a six-goal approach, as described below.

–Create positive workplaces. Leaders of health care systems should consider how their business and management decisions will affect clinicians’ jobs, taking into account the potential to add to their levels of burnout. Executives need to continuously monitor and evaluate the extent of burnout in their organizations, and report on this at least annually.

–Address burnout in training and in clinicians’ early years. Medical, nursing, and pharmacy schools should consider steps such as monitoring workload, implementing pass-fail grading, improving access to scholarships and affordable loans, and creating new loan repayment systems.

–Reduce administrative burden. Federal and state bodies and organizations such as the National Quality Forum should reconsider how their regulations and recommendations contribute to burnout. Organizations should seek to eliminate tasks that do not improve the care of patients.

–Improve usability and relevance of health information technology (IT). Medical organizations should develop and buy systems that are as user-friendly and easy to operate as possible. They also should look to use IT to reduce documentation demands and automate nonessential tasks.

–Reduce stigma and improve burnout recovery services. State officials and legislative bodies should make it easier for clinicians to use employee assistance programs, peer support programs, and mental health providers without the information being admissible in malpractice litigation. The report notes the recommendations from the Federation of State Medical Boards, American Medical Association, and the American Psychiatric Association on limiting inquiries in licensing applications about a clinician’s mental health. Questions should focus on current impairment rather than reach well into a clinician’s past.

–Create a national research agenda on clinician well-being. By the end of 2020, federal agencies – including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs – should develop a coordinated research agenda on clinician burnout, the report said.

In casting a wide net and assigning specific tasks, the NAM report seeks to establish efforts to address clinician burnout as a broad and shared responsibility. It would be too easy for different medical organizations to depict addressing burnout as being outside of their responsibilities, Christine K. Cassel, MD, the cochair of the NAM committee that produced the report, said during the press event.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth. Everyone is necessary to solve this problem,” said Dr. Cassel, who is a former chief executive officer of the National Quality Forum.

Darrell G. Kirch, MD, chief executive of the Association of American Medical Colleges, described the report as a “call to action” at the press event.

Previously published research has found between 35% and 54% of nurses and physicians in the United States have substantial symptoms of burnout, with the prevalence of burnout ranging between 45% and 60% for medical students and residents, the NAM report said.

Leaders of health organizations must consider how the policies they set will add stress for clinicians and make them less effective in caring for patients, said Vindell Washington, MD, chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana and a member of the NAM committee that wrote the report.

“Those linkages should be incentives and motivations for boards and leaders more broadly to act on the problem,” Dr. Washington said at the NAM event.

Dr. Kirch said he experienced burnout as a first-year medical student. He said a “brilliant aspect” of the NAM report is its emphasis on burnout as a response to the conditions under which medicine is practiced. In the past, burnout has been viewed as being the fault of the physician or nurse experiencing it, with the response then being to try to “fix” this individual, Dr. Kirch said at the event.

The NAM report instead defines burnout as a “work-related phenomenon studied since at least the 1970s,” in which an individual may experience exhaustion and detachment. Depression and other mental health issues such as anxiety disorders and addiction can follow burnout, he said. “That involves a real human toll.”

Joe Rotella, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, said in an interview that this NAM paper has the potential to spark the kind of transformation that its earlier research did for the quality of care. Then called the Institute of Medicine(IOM), NAM in 1999 issued a report, “To Err Is Human,” which is broadly seen as a key catalyst in efforts in the ensuing decades to improve the quality of care. IOM then followed up with a 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm.”

“Those papers over a period of time really did change the way we do health care,” said Dr. Rotella, who was not involved with the NAM report.

In Dr. Rotella’s view, the NAM report provides a solid framework for what remains a daunting task, addressing the many factors involved in burnout.

“The most exciting thing about this is that they don’t have 500 recommendations. They had six and that’s something people can organize around,” he said. “They are not small goals. I’m not saying they are simple.”

The NAM report delves into the factors that contribute to burnout. These include a maze of government and commercial insurance plans that create “a confusing and onerous environment for clinicians,” with many of them juggling “multiple payment systems with complex rules, processes, metrics, and incentives that may frequently change.”

Clinicians face a growing field of measurements intended to judge the quality of their performance. While some of these are useful, others are duplicative and some are not relevant to patient care, the NAM report said.

The report also noted that many clinicians describe electronic health records (EHRs) as taking a toll on their work and private lives. Previously published research has found that for every hour spent with a patient, physicians spend an additional 1-2 hours on the EHR at work, with additional time needed to complete this data entry at home after work hours, the report said.

In an interview, Cynda Rushton, RN, PhD, a Johns Hopkins University researcher and a member of the NAM committee that produced the report, said this new publication will support efforts to overhaul many aspects of current medical practice. She said she hopes it will be a “catalyst for bold and fundamental reform.

“It’s taking a deep dive into the evidence to see how we can begin to dismantle the system’s contributions to burnout,” she said. “No longer can we put Band-Aids on a gaping wound.”

The growing NP and PA workforce in hospital medicine

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

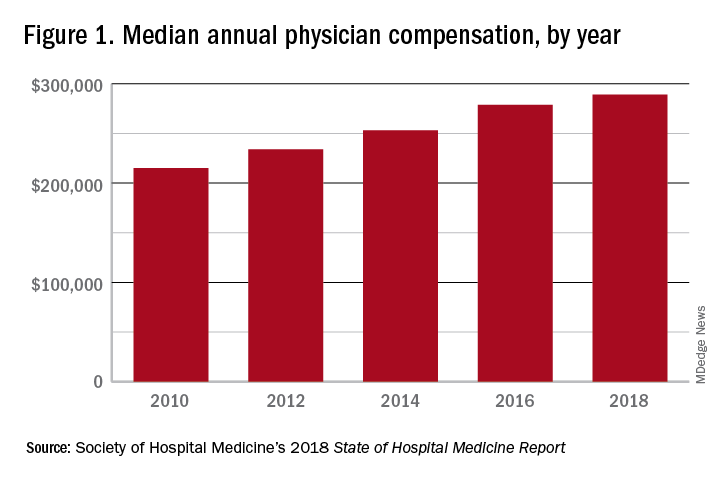

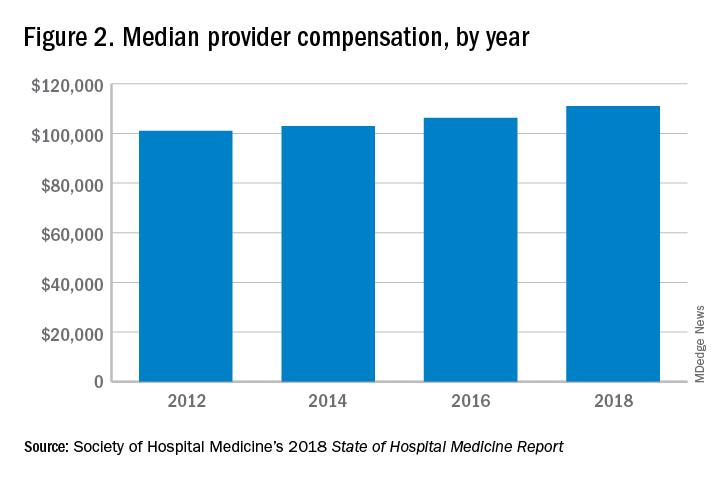

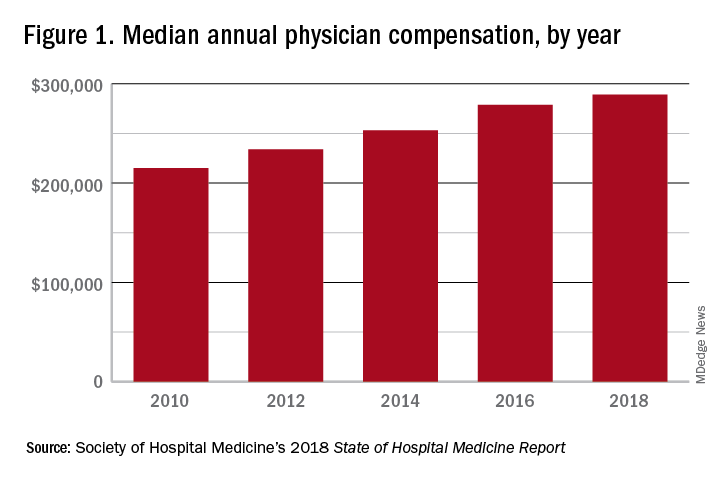

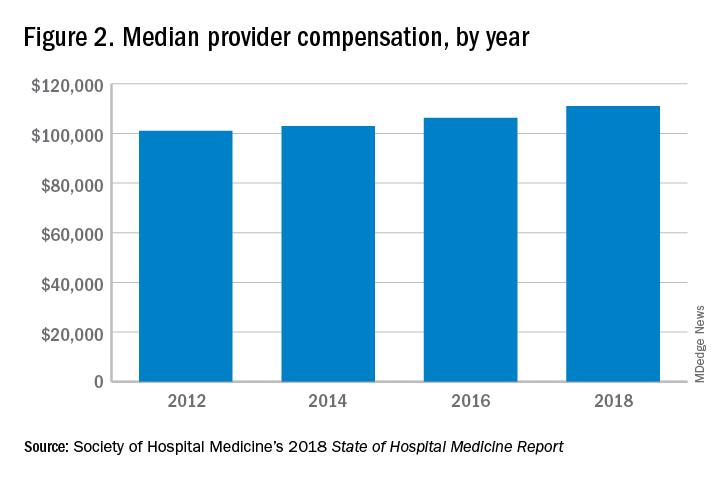

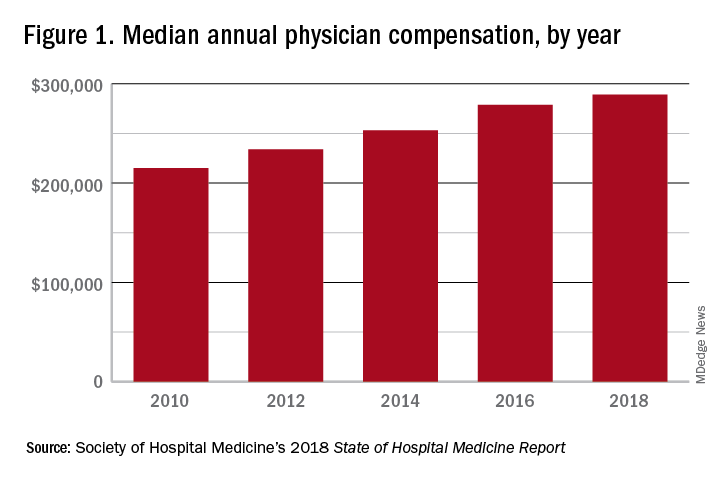

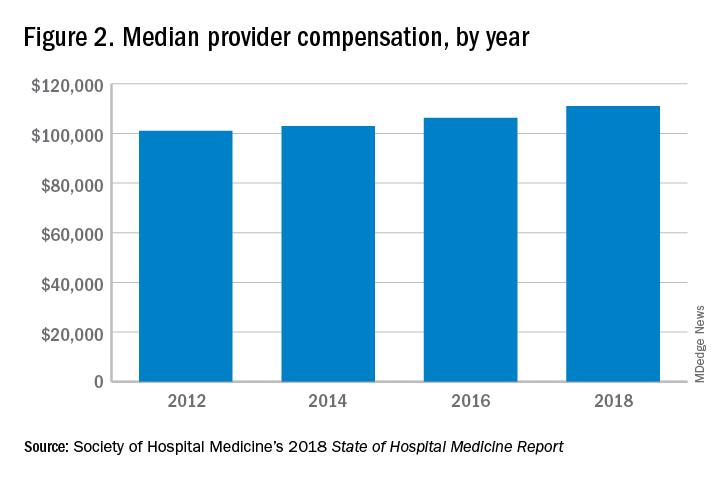

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

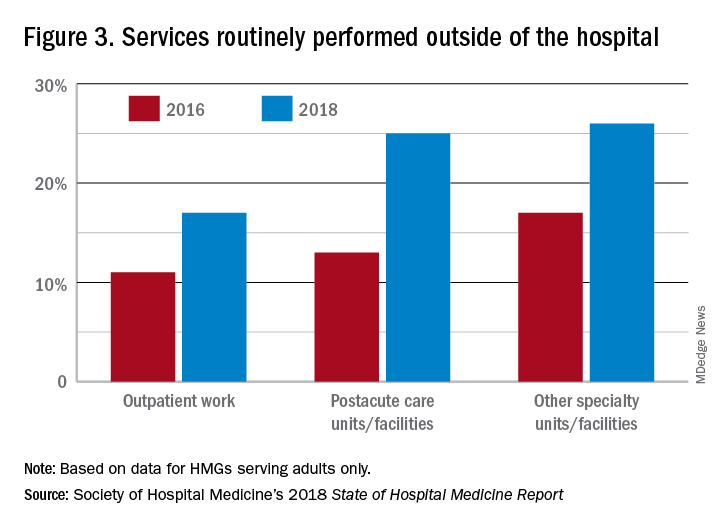

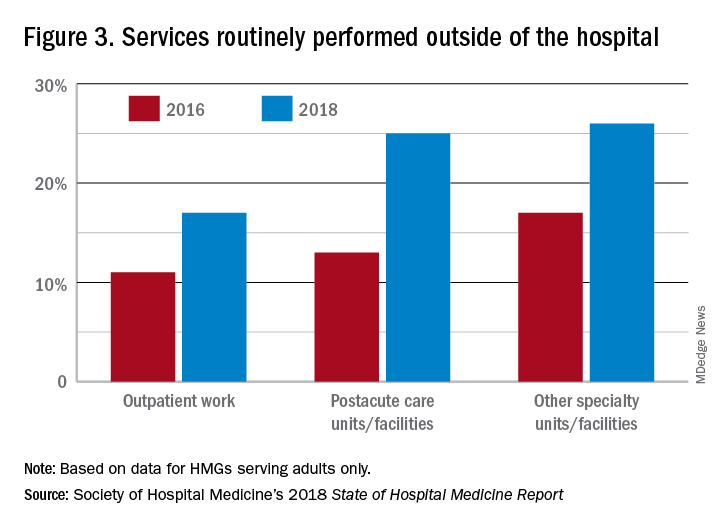

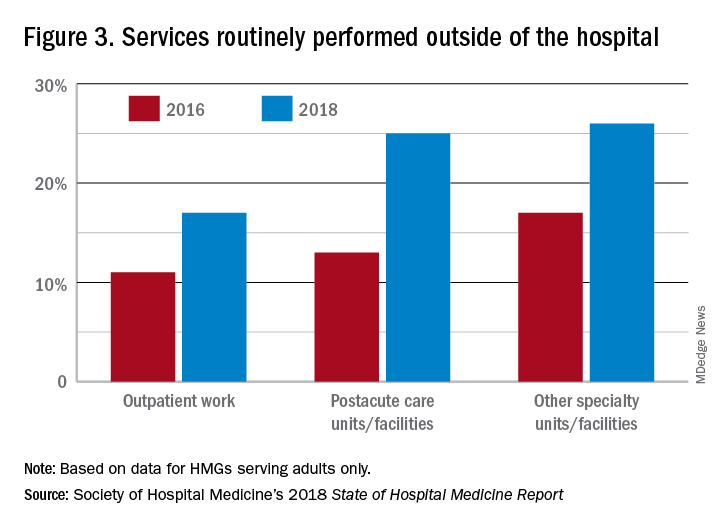

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

High rate of turnover among NPs, PAs

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

If you were a physician hospitalist in a group serving adults in 2017 you probably worked with nurse practitioners (NPs) and/or physician assistants (PAs). Seventy-seven percent of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) employed NPs and PAs that year.

In addition, the larger the group, the more likely the group was to have NPs and PAs as part of their practice model – 89% of hospital medicine groups with more than 30 physician had NPs and/or PAs as partners. In addition, the mean number of physicians for adult hospital medicine groups was 17.9. The same practices employed an average of 3.5 NPs, and 2.6 PAs.

Based on these numbers, there are just under three physicians per NP and PA in the typical HMG serving adults. This is all according to data from the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report that was published in 2019 by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

These observations lead to a number of questions. One thing that is not clear from the SoHM is why NPs and PAs are becoming a larger part of the hospital medicine workforce, but there are some insights and conjecture that can be drawn from the data. The first is economics. Over 6 years, the median incomes of NPs and PAs have risen a relatively modest 10%; over the same period physician hospitalists have seen a whopping 23.6% median pay increase.

One argument against economics as a driving force behind greater use of NPs and PAs in the hospital medicine workforce is the billing patterns of HMGs that use NPs and PAs. Ten percent of HMGs do not have their NPs and PAs bill at all. The distribution of HMGs that predominantly bill NP and PA services as shared visits, versus having NPs and PAs bill independently, has also not changed much over the years, with 22% of HMGs having NPs and PAs bill independently as a predominant model. This would seem to suggest that some HMGs may not have learned how to deploy NPs and PAs effectively.

While inefficiency can be due to hospital bylaws, the culture of the hospital medicine group, or the skill set of the NPs and PAs working in HMGs – it would seem that if the driving force for the increase in the utilization of NPs and PAs in HMGs was financial, then that would also result in more of these providers billing independently, or alternatively, an increase in hospitalist physician productivity, which the data do not show. However, multistate HMGs may have this figured out better than some of the rest of us – 78% of these HMGs have NPs and PAs billing independently! All other categories of HMGs together are around 13%, with the next highest being hospital or health system integrated delivery systems, where NPs/PAs bill independently about 15% of the time.

In the last 2 years of the survey, there have been marked increases in the number of NPs and PAs at HMGs performing “nontraditional” services. For example, outpatient work has increased from 11% to 17%, and work in the postacute space has increased from 13% to 25%. Work in behavioral health and alcohol and drug rehab facilities has also increased, from 17% to 26%. As HMGs seek to rationalize their workforce while expanding, it is possible that decision makers have felt that it was either more economical to place NPs and PAs in positions where they are seeing these patients, or it was more aligned with the NP/PA skill set, or both. In any event, as the scope of hospital medicine broadens, the use of PAs and NPs has also increased – which is probably not coincidental.

The average hospital medicine group continues to have staff openings. Workforce shortages may be leading to what in the past may have been considered physician openings being filled by NPs and PAs. Only 33% of HMGs reported having all their physician openings filled. Median physician shortage was 12% of total approved staffing. Given concerns in hospital medicine about provider burnout, the number of hospital medicine openings is no doubt a concern to HMG leaders and hospitalists. And necessity being the mother of invention, HMG leadership must be thinking differently than in the past about open positions and the skill mix needed to fill them. I believe this is leading to NPs and PAs being considered more often for a role that would have been open only to a physician in the past.

Just as open positions are a concern, so is turnover. One striking finding in the SoHM is the very high rate of turnover among NPs and PAs – a whopping 19.1% per year. For physicians, the same rate was 7.4% and has been declining every survey for many years. While NPs and PAs may be intended to stabilize the workforce, because of how this is being done in some groups, NPs and PAs may instead be a destabilizing factor. Rapid growth can lead to haphazard onboarding and less than clearly defined roles. NPs and PAs may often be placed into roles for which they are not yet prepared. In addition, the pay disparity between NPs and PAs and physicians has increased. As a new field, and with many HMGs still rapidly growing, increased thoughtfulness and maturity about how NPs and PAs are integrated into hospital medicine practices should lead to less turnover and better HMG stability in the future.

These observations could mark a future that includes higher pay for hospital medicine PAs and NPs (and potentially a slowdown in salary growth for physicians); HMGs taking steps to make the financial model more attractive by having NPs and PAs bill independently more often; and HMGs and their leaders engaging NPs and PAs by more clearly defining roles, shoring up onboarding and mentoring programs, and other measures that decrease turnover. This would help to make hospital medicine a career destination, rather than a stopping off point for NPs and PAs, much as it has become for internists over the past 20 years.

Dr. Frederickson is medical director, hospital medicine and palliative care, at CHI Health, Omaha, Neb., and assistant professor at Creighton University, Omaha.

Gender bias and pediatric hospital medicine

Where do we go from here?

Autumn is a busy time for pediatric hospitalists, with this autumn being particularly eventful as the first American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) certifying exam for Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) will be offered on Nov. 12, 2019.

More than 1,600 med/peds and pediatric hospitalists applied to be eligible for the 2019 exam, 71% of whom were women. At least 3.9% of those applicants were denied eligibility for the 2019 exam.1 These denials resulted in discussions on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) email listserv related to unintentional gender bias.

PHM was first recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in December 2015.2 Since that time, the ABP’s PHM sub-board developed eligibility criteria for practicing pediatric and med/peds hospitalists to apply for the exam. The sub-board identified three paths: a training pathway for applicants who had completed a 2-year PHM fellowship, a practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM, and a combined pathway for applicants who had completed PHM fellowships lasting less than 2 years.

Based on these pathways, 1,627 applicants applied for eligibility for the first PHM board certification exam.1 However, many concerns arose with the practice pathway eligibility criteria.

The PHM practice pathway initially included the following eligibility criteria:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice “look back” period ends on or before June 30 of the exam year and starts 4 years earlier.

• More than 0.5 FTE professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• More than 0.25 FTE direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice interruptions cannot exceed 3 months in the preceding 4 years, or 6 months in the preceding 5 years.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1,3

The start date and practice interruptions criteria in the practice pathway posed hurdles for many female applicants. Many women voiced concerns about feeling disadvantaged when applying for the PHM certifying exam and some of these women shared their concerns on the AAP SOHM email listserv. In response to these concerns, the PHM community called for increased transparency from the ABP related to denials, specifically related to unintentional gender bias against women applying for the exam.

David Skey, MD, and Jamee Walters, MD, pediatric hospitalists at Arnold Palmer Medical Center in Orlando, heard these concerns and decided to draft a petition with the help of legal counsel. The petition “demand[ed] immediate action,” and “request[ed] a formal response from the ABP regarding the practice pathway criteria.” The petition also stated that there was insufficient data to determine if the practice pathway “disadvantages women.” The petition asked the ABP to “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias” was present, or to perform an internal analysis and “release the findings publicly.”4

The petition was shared with the PHM community via the AAP SOHM listserv on July 29, 2019. Dr. Walters stated she was pleased by the response she and Dr. Skey received from the PHM community, on and off the AAP SOHM listserv. The petition was submitted to the ABP on Aug. 6, 2019, with 1,479 signatures.

On Aug. 29, 2019, the ABP’s response was shared on the AAP SOHM email listserv1 and was later published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a Special Announcement.5 In its response, the ABP stated that the gender bias allegation was “not supported by the facts” as there was “no significant difference between the percentage of women and men who were denied” eligibility.”5 In addressing the gender bias allegations and clarifying the practice pathway eligibility, the ABP removed the practice interruption criteria and modified the practice pathway criteria as follows:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice started on or before July 2015 (for board eligibility in 2019).

• Professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900-1000 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450-500 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1

Following the release of the ABP’s response, many members of the PHM community remain concerned about the ABP’s revised criteria. Arti Desai, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Seattle Children’s and senior author on a “Perspectives in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine,6 was appreciative that the ABP chose to remove the practice interruptions criterion. However, she and her colleagues remain concerned about lingering gender bias in the ABP’s practice pathway eligibility criteria surrounding the “start date” criterion. The authors state that this criterion differentially affects women, as women may take time off during or after residency for maternity or family leave. Dr. Desai states that this criterion alone can affect a woman’s chance for being eligible for the practice pathway.

Other members of the PHM community also expressed concerns about the ABP’s response to the PHM petition. Beth C. Natt, MD, pediatric hospitalist and director of pediatric hospital medicine regional programs at Connecticut Children’s in Hartford, felt that the population may have been self-selected, as the ABP’s data were limited to individuals who applied for exam eligibility. She was concerned that the data excluded pediatric hospitalists who chose not to apply because of uncertainty about meeting eligibility criteria. Klint Schwenk, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky., stated that he wished the ABP had addressed the number of pediatric hospitalists who elected not to apply based on fear of ineligibility before concluding that there was no bias. He likened the ABP’s response to that of study authors omitting selection bias when discussing the limitations of their study.

Courtney Edgar-Zarate, MD, med/peds hospitalist and associate program director of the internal medicine/pediatrics residency at the University of Arkansas, expressed concerns that the ABP’s stringent clinical patient care hours criterion may unintentionally result in ineligibility for many mid-career or senior med/peds hospitalists. Dr. Edgar-Zarate also voiced concerns that graduating med/peds residents were electing not to pursue careers in hospital medicine because they would be required to complete a PHM fellowship to become a pediatric hospitalist, when a similar fellowship is not required to practice adult hospital medicine.

The Society of Hospital Medicine shared its position in regard to the ABP’s response in a Special Announcement in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.7 In it, SHM’s pediatric leaders recognized physicians for the excellent care they provide to hospitalized children. They stated that SHM would continue to support all hospitalists, independent of board eligibility status, and would continue to offer these hospitalists the merit-based Fellow designation. SHM’s pediatric leaders also proposed future directions for the ABP, including a Focused Practice Pathway in Hospital Medicine (FPHM), such as what the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Family Medicine have adopted for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine. This maintenance of certification program that allows physicians primarily practicing in inpatient settings to focus their continuing education on inpatient practice, and is not a subspecialty.7

Dr. Edgar-Zarate fully supports the future directions for pediatric hospitalists outlined in SHM’s Special Announcement. She hopes that the ABP will support the FPHM. She feels the FPHM will encourage more med/peds physicians to practice med/peds hospital medicine. L. Nell Hodo, MD, a family medicine–trained pediatric hospitalist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, joins Dr. Edgar-Zarate in supporting an FPHM for PHM, and feels that it will open the door for hospitalists who are ineligible for the practice pathway to be able to focus their recertification on the inpatient setting.

Dr. Hodo and Dr. Desai hope that rather than excluding those who are not PHM board eligible/certified, institutions and professional organizations will consider all qualifications when hiring, mentoring, and promoting physicians who care for hospitalized children. Dr. Natt, Dr. Schwenk, Dr. Edgar-Zarate, and Dr. Hodo appreciate that SHM is leading the way, and will continue to allow all hospitalists who care for children to receive Fellow designation.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. The American Board of Pediatrics. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019.

2. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

3. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification. Published 2019.

4. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC.

5. Nichols DG, Woods SZ. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):586-8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3322.

6. Gold JM et al. Collective action and effective dialogue to address gender bias in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):630-2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3331.

7. Chang WW et al. Society of Hospital Medicine position on the American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3326.

Where do we go from here?

Where do we go from here?

Autumn is a busy time for pediatric hospitalists, with this autumn being particularly eventful as the first American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) certifying exam for Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) will be offered on Nov. 12, 2019.

More than 1,600 med/peds and pediatric hospitalists applied to be eligible for the 2019 exam, 71% of whom were women. At least 3.9% of those applicants were denied eligibility for the 2019 exam.1 These denials resulted in discussions on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) email listserv related to unintentional gender bias.

PHM was first recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in December 2015.2 Since that time, the ABP’s PHM sub-board developed eligibility criteria for practicing pediatric and med/peds hospitalists to apply for the exam. The sub-board identified three paths: a training pathway for applicants who had completed a 2-year PHM fellowship, a practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM, and a combined pathway for applicants who had completed PHM fellowships lasting less than 2 years.

Based on these pathways, 1,627 applicants applied for eligibility for the first PHM board certification exam.1 However, many concerns arose with the practice pathway eligibility criteria.

The PHM practice pathway initially included the following eligibility criteria:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice “look back” period ends on or before June 30 of the exam year and starts 4 years earlier.

• More than 0.5 FTE professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• More than 0.25 FTE direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice interruptions cannot exceed 3 months in the preceding 4 years, or 6 months in the preceding 5 years.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1,3

The start date and practice interruptions criteria in the practice pathway posed hurdles for many female applicants. Many women voiced concerns about feeling disadvantaged when applying for the PHM certifying exam and some of these women shared their concerns on the AAP SOHM email listserv. In response to these concerns, the PHM community called for increased transparency from the ABP related to denials, specifically related to unintentional gender bias against women applying for the exam.

David Skey, MD, and Jamee Walters, MD, pediatric hospitalists at Arnold Palmer Medical Center in Orlando, heard these concerns and decided to draft a petition with the help of legal counsel. The petition “demand[ed] immediate action,” and “request[ed] a formal response from the ABP regarding the practice pathway criteria.” The petition also stated that there was insufficient data to determine if the practice pathway “disadvantages women.” The petition asked the ABP to “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias” was present, or to perform an internal analysis and “release the findings publicly.”4

The petition was shared with the PHM community via the AAP SOHM listserv on July 29, 2019. Dr. Walters stated she was pleased by the response she and Dr. Skey received from the PHM community, on and off the AAP SOHM listserv. The petition was submitted to the ABP on Aug. 6, 2019, with 1,479 signatures.

On Aug. 29, 2019, the ABP’s response was shared on the AAP SOHM email listserv1 and was later published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a Special Announcement.5 In its response, the ABP stated that the gender bias allegation was “not supported by the facts” as there was “no significant difference between the percentage of women and men who were denied” eligibility.”5 In addressing the gender bias allegations and clarifying the practice pathway eligibility, the ABP removed the practice interruption criteria and modified the practice pathway criteria as follows:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice started on or before July 2015 (for board eligibility in 2019).

• Professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900-1000 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450-500 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1

Following the release of the ABP’s response, many members of the PHM community remain concerned about the ABP’s revised criteria. Arti Desai, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Seattle Children’s and senior author on a “Perspectives in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine,6 was appreciative that the ABP chose to remove the practice interruptions criterion. However, she and her colleagues remain concerned about lingering gender bias in the ABP’s practice pathway eligibility criteria surrounding the “start date” criterion. The authors state that this criterion differentially affects women, as women may take time off during or after residency for maternity or family leave. Dr. Desai states that this criterion alone can affect a woman’s chance for being eligible for the practice pathway.

Other members of the PHM community also expressed concerns about the ABP’s response to the PHM petition. Beth C. Natt, MD, pediatric hospitalist and director of pediatric hospital medicine regional programs at Connecticut Children’s in Hartford, felt that the population may have been self-selected, as the ABP’s data were limited to individuals who applied for exam eligibility. She was concerned that the data excluded pediatric hospitalists who chose not to apply because of uncertainty about meeting eligibility criteria. Klint Schwenk, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky., stated that he wished the ABP had addressed the number of pediatric hospitalists who elected not to apply based on fear of ineligibility before concluding that there was no bias. He likened the ABP’s response to that of study authors omitting selection bias when discussing the limitations of their study.

Courtney Edgar-Zarate, MD, med/peds hospitalist and associate program director of the internal medicine/pediatrics residency at the University of Arkansas, expressed concerns that the ABP’s stringent clinical patient care hours criterion may unintentionally result in ineligibility for many mid-career or senior med/peds hospitalists. Dr. Edgar-Zarate also voiced concerns that graduating med/peds residents were electing not to pursue careers in hospital medicine because they would be required to complete a PHM fellowship to become a pediatric hospitalist, when a similar fellowship is not required to practice adult hospital medicine.

The Society of Hospital Medicine shared its position in regard to the ABP’s response in a Special Announcement in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.7 In it, SHM’s pediatric leaders recognized physicians for the excellent care they provide to hospitalized children. They stated that SHM would continue to support all hospitalists, independent of board eligibility status, and would continue to offer these hospitalists the merit-based Fellow designation. SHM’s pediatric leaders also proposed future directions for the ABP, including a Focused Practice Pathway in Hospital Medicine (FPHM), such as what the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Family Medicine have adopted for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine. This maintenance of certification program that allows physicians primarily practicing in inpatient settings to focus their continuing education on inpatient practice, and is not a subspecialty.7

Dr. Edgar-Zarate fully supports the future directions for pediatric hospitalists outlined in SHM’s Special Announcement. She hopes that the ABP will support the FPHM. She feels the FPHM will encourage more med/peds physicians to practice med/peds hospital medicine. L. Nell Hodo, MD, a family medicine–trained pediatric hospitalist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, joins Dr. Edgar-Zarate in supporting an FPHM for PHM, and feels that it will open the door for hospitalists who are ineligible for the practice pathway to be able to focus their recertification on the inpatient setting.

Dr. Hodo and Dr. Desai hope that rather than excluding those who are not PHM board eligible/certified, institutions and professional organizations will consider all qualifications when hiring, mentoring, and promoting physicians who care for hospitalized children. Dr. Natt, Dr. Schwenk, Dr. Edgar-Zarate, and Dr. Hodo appreciate that SHM is leading the way, and will continue to allow all hospitalists who care for children to receive Fellow designation.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. The American Board of Pediatrics. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019.

2. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

3. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification. Published 2019.

4. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC.

5. Nichols DG, Woods SZ. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):586-8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3322.

6. Gold JM et al. Collective action and effective dialogue to address gender bias in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):630-2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3331.

7. Chang WW et al. Society of Hospital Medicine position on the American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3326.

Autumn is a busy time for pediatric hospitalists, with this autumn being particularly eventful as the first American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) certifying exam for Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) will be offered on Nov. 12, 2019.

More than 1,600 med/peds and pediatric hospitalists applied to be eligible for the 2019 exam, 71% of whom were women. At least 3.9% of those applicants were denied eligibility for the 2019 exam.1 These denials resulted in discussions on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) email listserv related to unintentional gender bias.

PHM was first recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in December 2015.2 Since that time, the ABP’s PHM sub-board developed eligibility criteria for practicing pediatric and med/peds hospitalists to apply for the exam. The sub-board identified three paths: a training pathway for applicants who had completed a 2-year PHM fellowship, a practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM, and a combined pathway for applicants who had completed PHM fellowships lasting less than 2 years.

Based on these pathways, 1,627 applicants applied for eligibility for the first PHM board certification exam.1 However, many concerns arose with the practice pathway eligibility criteria.

The PHM practice pathway initially included the following eligibility criteria:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice “look back” period ends on or before June 30 of the exam year and starts 4 years earlier.

• More than 0.5 FTE professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• More than 0.25 FTE direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice interruptions cannot exceed 3 months in the preceding 4 years, or 6 months in the preceding 5 years.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1,3

The start date and practice interruptions criteria in the practice pathway posed hurdles for many female applicants. Many women voiced concerns about feeling disadvantaged when applying for the PHM certifying exam and some of these women shared their concerns on the AAP SOHM email listserv. In response to these concerns, the PHM community called for increased transparency from the ABP related to denials, specifically related to unintentional gender bias against women applying for the exam.

David Skey, MD, and Jamee Walters, MD, pediatric hospitalists at Arnold Palmer Medical Center in Orlando, heard these concerns and decided to draft a petition with the help of legal counsel. The petition “demand[ed] immediate action,” and “request[ed] a formal response from the ABP regarding the practice pathway criteria.” The petition also stated that there was insufficient data to determine if the practice pathway “disadvantages women.” The petition asked the ABP to “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias” was present, or to perform an internal analysis and “release the findings publicly.”4

The petition was shared with the PHM community via the AAP SOHM listserv on July 29, 2019. Dr. Walters stated she was pleased by the response she and Dr. Skey received from the PHM community, on and off the AAP SOHM listserv. The petition was submitted to the ABP on Aug. 6, 2019, with 1,479 signatures.

On Aug. 29, 2019, the ABP’s response was shared on the AAP SOHM email listserv1 and was later published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a Special Announcement.5 In its response, the ABP stated that the gender bias allegation was “not supported by the facts” as there was “no significant difference between the percentage of women and men who were denied” eligibility.”5 In addressing the gender bias allegations and clarifying the practice pathway eligibility, the ABP removed the practice interruption criteria and modified the practice pathway criteria as follows:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice started on or before July 2015 (for board eligibility in 2019).

• Professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900-1000 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450-500 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1

Following the release of the ABP’s response, many members of the PHM community remain concerned about the ABP’s revised criteria. Arti Desai, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Seattle Children’s and senior author on a “Perspectives in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine,6 was appreciative that the ABP chose to remove the practice interruptions criterion. However, she and her colleagues remain concerned about lingering gender bias in the ABP’s practice pathway eligibility criteria surrounding the “start date” criterion. The authors state that this criterion differentially affects women, as women may take time off during or after residency for maternity or family leave. Dr. Desai states that this criterion alone can affect a woman’s chance for being eligible for the practice pathway.

Other members of the PHM community also expressed concerns about the ABP’s response to the PHM petition. Beth C. Natt, MD, pediatric hospitalist and director of pediatric hospital medicine regional programs at Connecticut Children’s in Hartford, felt that the population may have been self-selected, as the ABP’s data were limited to individuals who applied for exam eligibility. She was concerned that the data excluded pediatric hospitalists who chose not to apply because of uncertainty about meeting eligibility criteria. Klint Schwenk, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky., stated that he wished the ABP had addressed the number of pediatric hospitalists who elected not to apply based on fear of ineligibility before concluding that there was no bias. He likened the ABP’s response to that of study authors omitting selection bias when discussing the limitations of their study.

Courtney Edgar-Zarate, MD, med/peds hospitalist and associate program director of the internal medicine/pediatrics residency at the University of Arkansas, expressed concerns that the ABP’s stringent clinical patient care hours criterion may unintentionally result in ineligibility for many mid-career or senior med/peds hospitalists. Dr. Edgar-Zarate also voiced concerns that graduating med/peds residents were electing not to pursue careers in hospital medicine because they would be required to complete a PHM fellowship to become a pediatric hospitalist, when a similar fellowship is not required to practice adult hospital medicine.

The Society of Hospital Medicine shared its position in regard to the ABP’s response in a Special Announcement in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.7 In it, SHM’s pediatric leaders recognized physicians for the excellent care they provide to hospitalized children. They stated that SHM would continue to support all hospitalists, independent of board eligibility status, and would continue to offer these hospitalists the merit-based Fellow designation. SHM’s pediatric leaders also proposed future directions for the ABP, including a Focused Practice Pathway in Hospital Medicine (FPHM), such as what the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Family Medicine have adopted for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine. This maintenance of certification program that allows physicians primarily practicing in inpatient settings to focus their continuing education on inpatient practice, and is not a subspecialty.7

Dr. Edgar-Zarate fully supports the future directions for pediatric hospitalists outlined in SHM’s Special Announcement. She hopes that the ABP will support the FPHM. She feels the FPHM will encourage more med/peds physicians to practice med/peds hospital medicine. L. Nell Hodo, MD, a family medicine–trained pediatric hospitalist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, joins Dr. Edgar-Zarate in supporting an FPHM for PHM, and feels that it will open the door for hospitalists who are ineligible for the practice pathway to be able to focus their recertification on the inpatient setting.

Dr. Hodo and Dr. Desai hope that rather than excluding those who are not PHM board eligible/certified, institutions and professional organizations will consider all qualifications when hiring, mentoring, and promoting physicians who care for hospitalized children. Dr. Natt, Dr. Schwenk, Dr. Edgar-Zarate, and Dr. Hodo appreciate that SHM is leading the way, and will continue to allow all hospitalists who care for children to receive Fellow designation.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. The American Board of Pediatrics. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019.

2. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

3. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification. Published 2019.

4. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC.

5. Nichols DG, Woods SZ. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):586-8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3322.

6. Gold JM et al. Collective action and effective dialogue to address gender bias in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):630-2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3331.

7. Chang WW et al. Society of Hospital Medicine position on the American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3326.

Who makes the rules? CMS and IPPS

Major MS-DRG changes postponed

The introduction of the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) through amendment of the Social Security Act in 1983 transformed hospital reimbursement in the United States. Under the IPPS, a new form of Medicare prospective payment that paid hospitals a fixed amount per discharge for inpatient services was created: the diagnosis-related group (DRG). This eliminated the preceding retrospective cost reimbursement system in an attempt to stop health care price inflation.

Each DRG represents a grouping of similar conditions and procedures for services provided during an inpatient hospitalization reimbursed under Medicare Part A. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses the Medicare Severity DRG (MS-DRG) system to account for severity of illness and resource consumption. There are three levels of severity based upon secondary diagnosis: major complication/comorbidity (MCC), complication/comorbidity (CC), and noncomplication/comorbidity (non-CC).

Payment rates are defined by base rates for operating costs and capital-related costs which are adjusted for relative weight (the average cost within a DRG, compared with the average Medicare case cost) and market condition adjustments. As the largest single health care payer in the United States, CMS’ annual changes to the IPPS have a major impact on hospital reimbursement.

In May 2019, CMS released its annual proposed rule for the Hospital IPPS suggesting extensive changes to MS-DRG reimbursements. Notably, CMS proposed changing the severity level of nearly 1,500 diagnosis codes by adjusting their categorization between MCC, CC, or non-CC. The majority of these changes included downgrading MCCs to CCs or non-CCs. In fact, 87% of the changes involved a downgrade from one of the higher severity levels to a non-CC level, while only 13% involved an upgrade from a lower severity level to MCC level.

The CMS derived these changes from an algorithmic review and input from their clinical advisors to determine each diagnoses impact on resource utilization. Multiple major groups of codes were included in the downgraded groups, including secondary cancer diagnoses, organ transplant status, and hip fracture.

Evaluating codes based on coded resource use alone could have had a major negative impact on the clinical practice of hospitalists as it undervalues cognitive and clinical work associated with these secondary diagnoses. As an example, malignant neoplasm of head of pancreas (ICD-10, C25.0) was proposed to move to a non-CC. Under CMS’ proposed rule, if a patient was admitted with complications of pancreatic cancer such as cholangitis caused by biliary obstruction, the pancreatic cancer diagnosis would not serve as a CC since the primary condition for which the patient was hospitalized would be cholangitis. The anticipated increase in such a patient’s length of stay, severity of illness, and expected resource utilization would be grossly misrepresented in this case by CMS’ proposed rule changes. CMS also proposed to move major organ-transplant status (including heart, lung, kidney, and pancreas) from CC to non-CC status. Again, the cognitive work and resource utilization required to manage these patients would be underrepresented with this change, given the increased complexity of managing immunosuppressant medications or conducting an infectious diagnostic work-up in immunosuppressed patients.

The Society of Hospital Medicine Public Policy Committee provides comments annually to CMS on the IPPS, advocating for hospitalists and patients. After advocacy efforts from SHM and other groups, expressing concern about making such significant changes to the DRG system without further study, the IPPS final rule was released on August 2, 2019. SHM’s efforts paid off. The final rule excluded the proposed broad changes to the MS-DRG system that were in the proposed rule.

In deciding not to finalize the proposed severity level changes, CMS wrote that the adoption of these broad changes will be postponed in order “to fully consider the technical feedback provided” regarding the proposal. The final rule also describes making a “test GROUPER [software program] publicly available to allow for impact testing,” and allows for the possibility of phasing in changes and eliciting feedback. SHM is fully supportive of the decision to postpone major changes to the MS-DRG system in the IPPS until further review is obtained, and will continue to monitor this issue and provide appropriate input to CMS for our hospitalist members.

As hospitalists, it is important to understand the foundational role that public policy and CMS rule creation have on our work. Influencing change to the MS-DRG system is yet another example of how SHM’s work has impacted the policy domain, limiting negative effects on our members and advancing the practice of hospital medicine.

Dr. Biebelhausen is head of the section of hospital medicine at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle. Dr. Cowart is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. Dr. Hamilton is a hospitalist and associate chief quality officer at the Cleveland Clinic.

Major MS-DRG changes postponed

Major MS-DRG changes postponed