User login

Erythematous ear with drainage

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

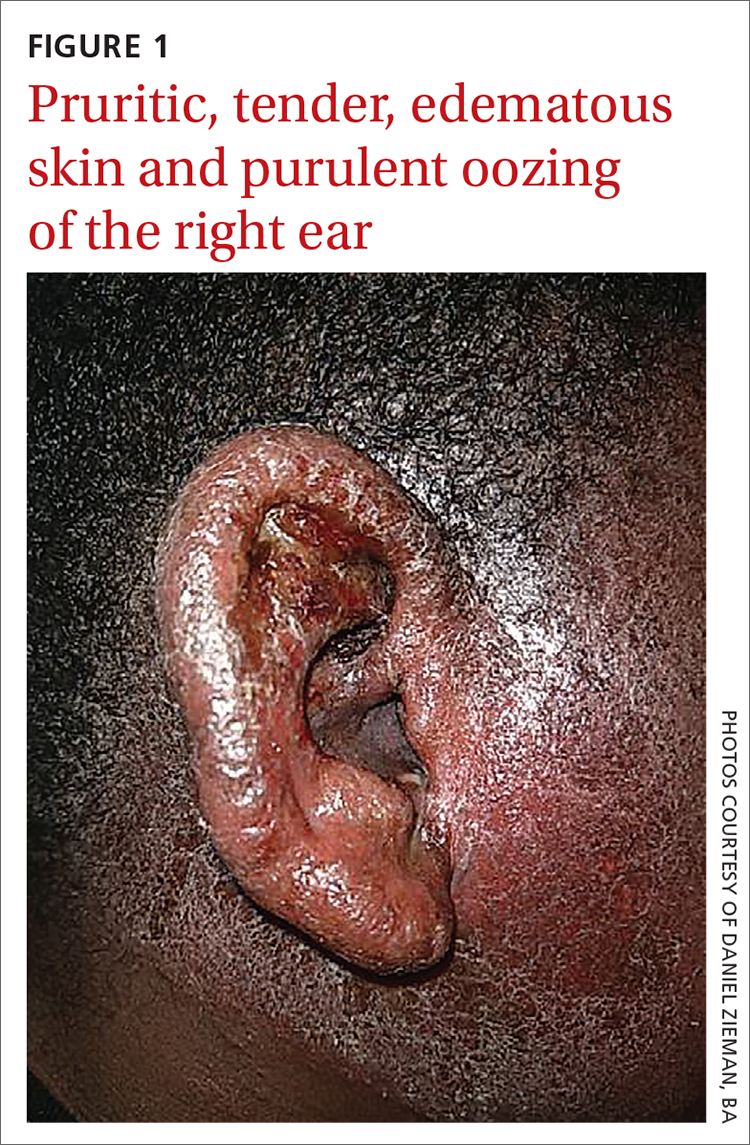

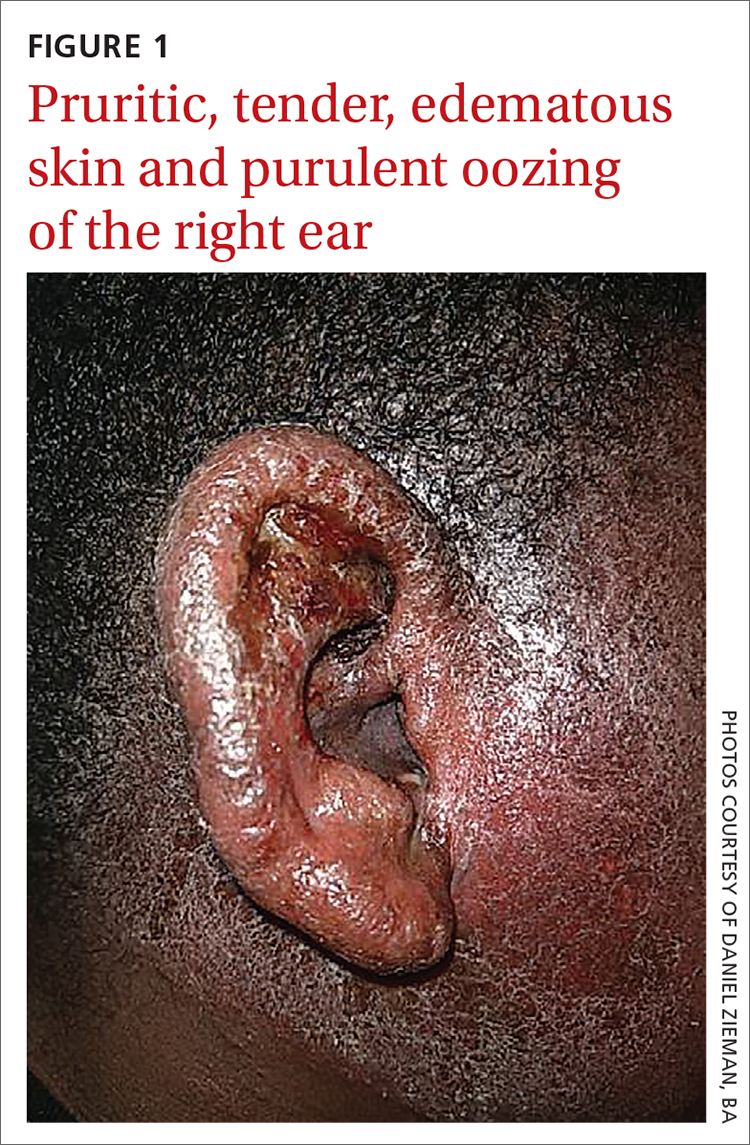

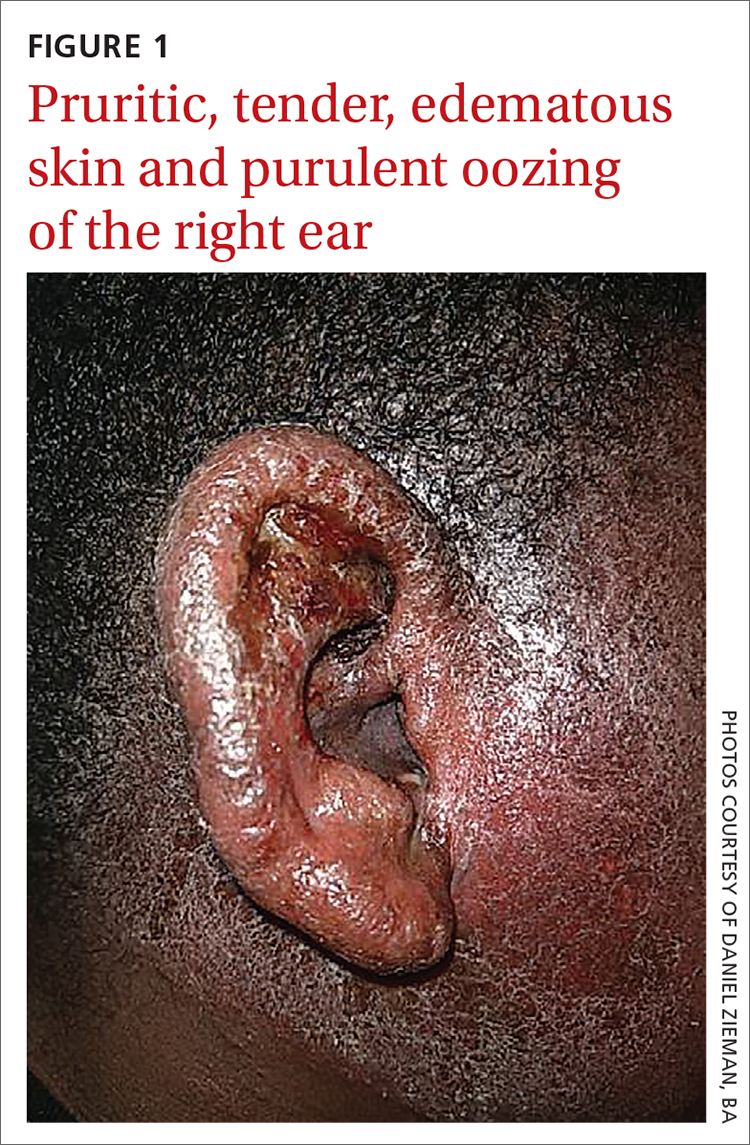

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

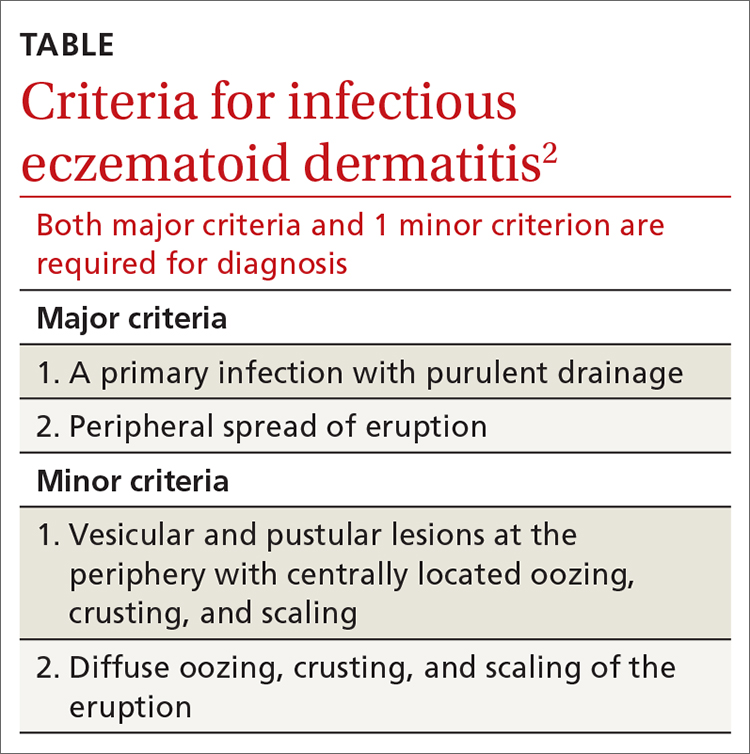

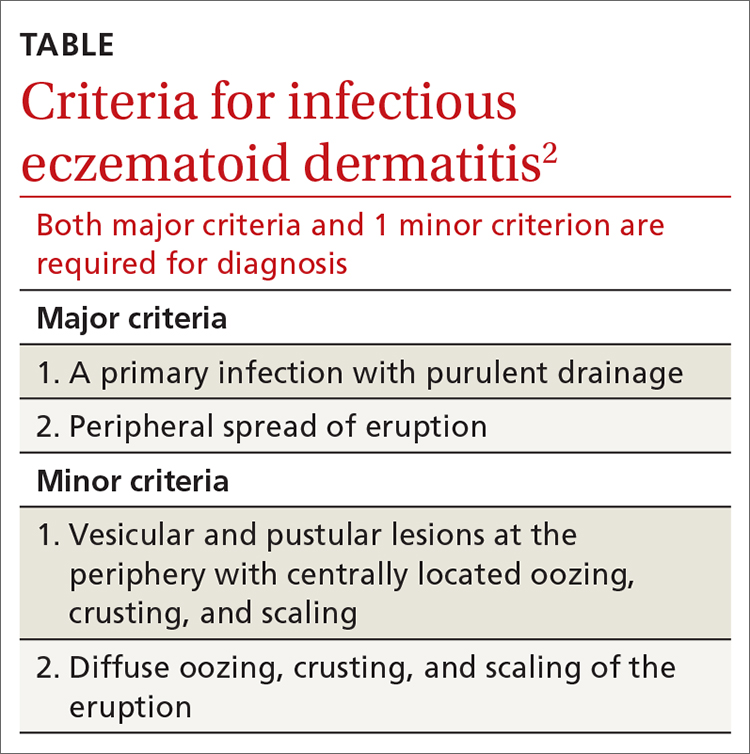

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

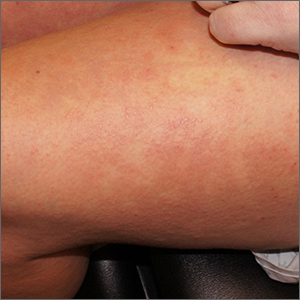

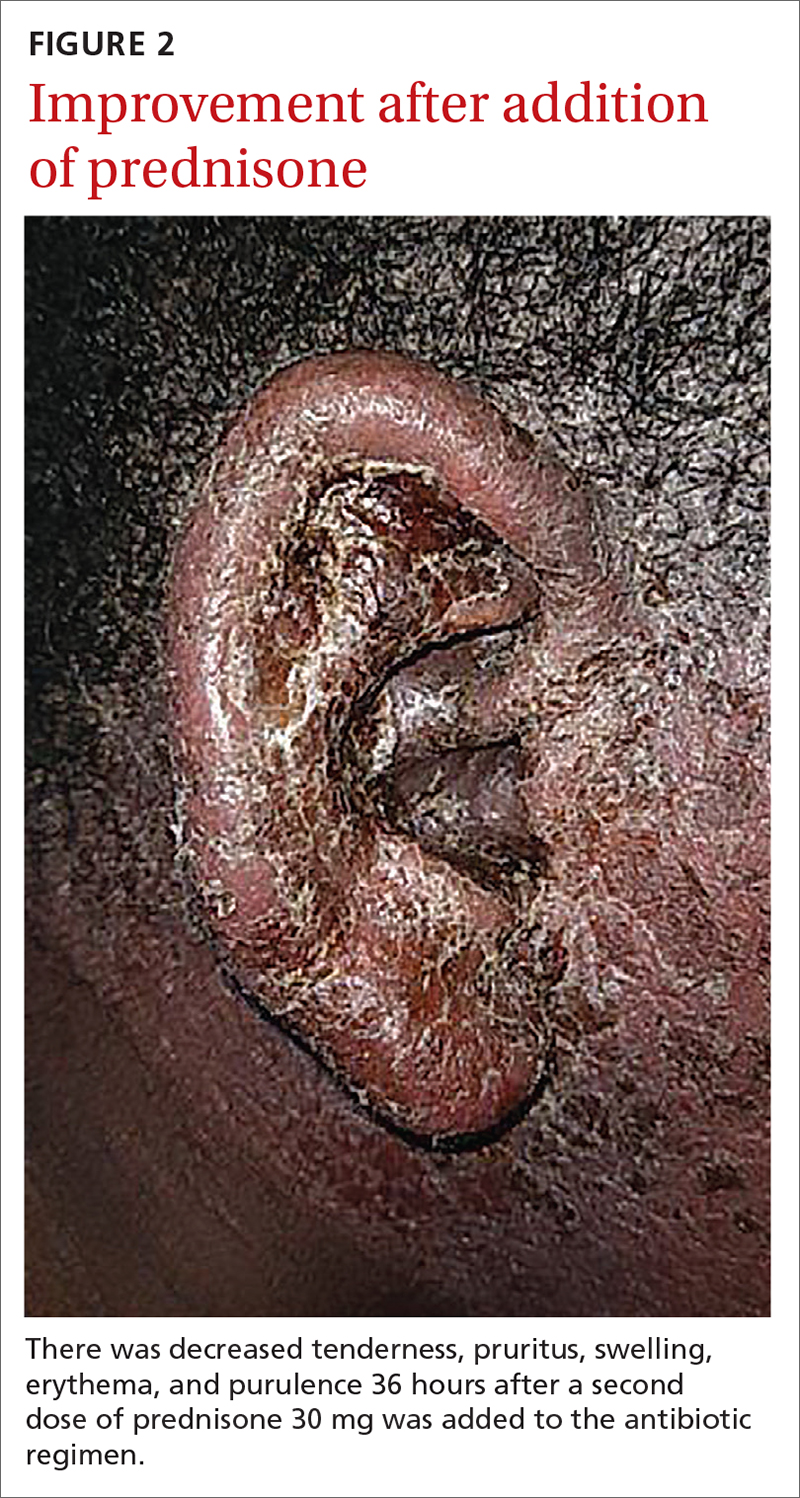

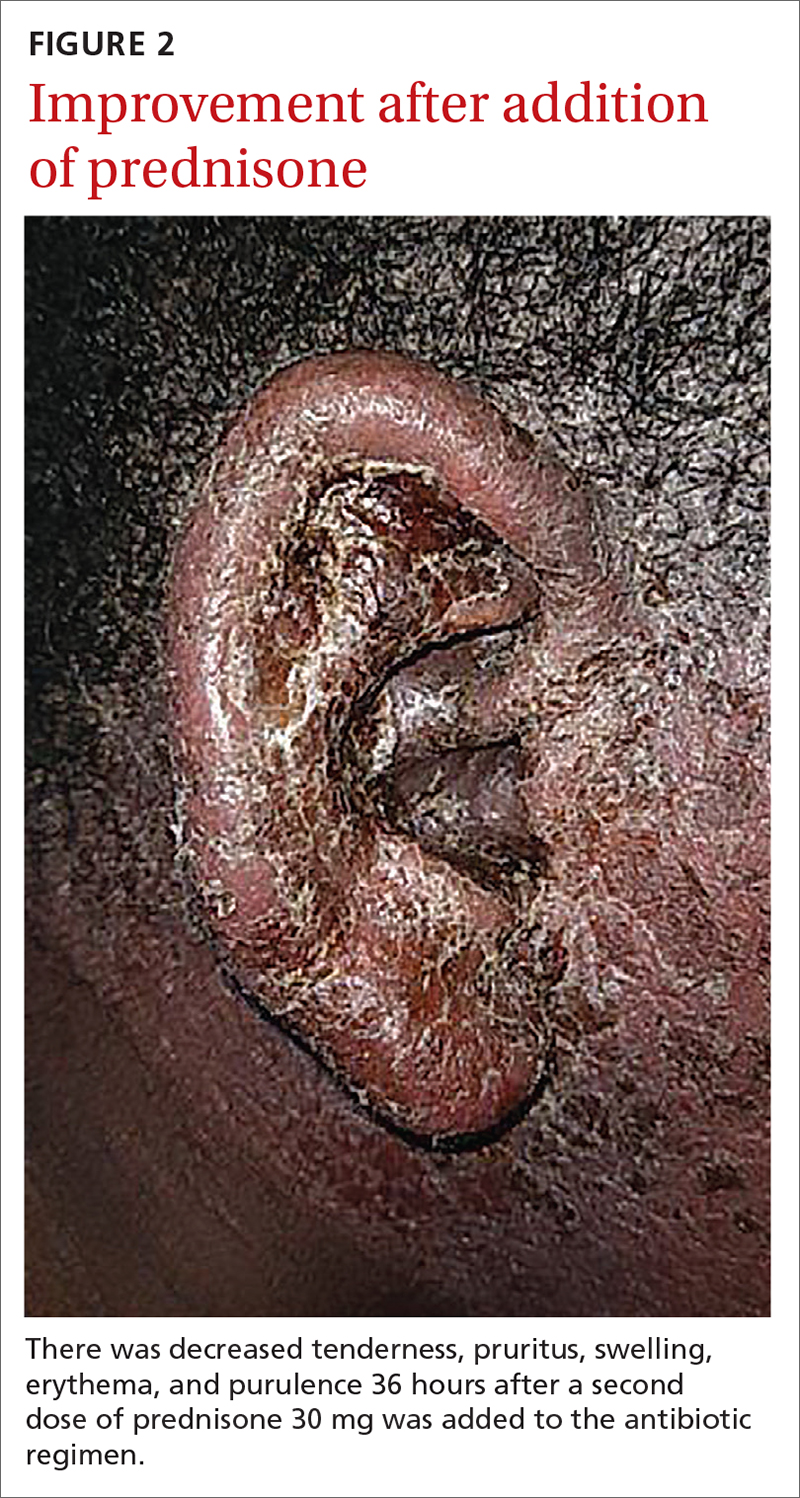

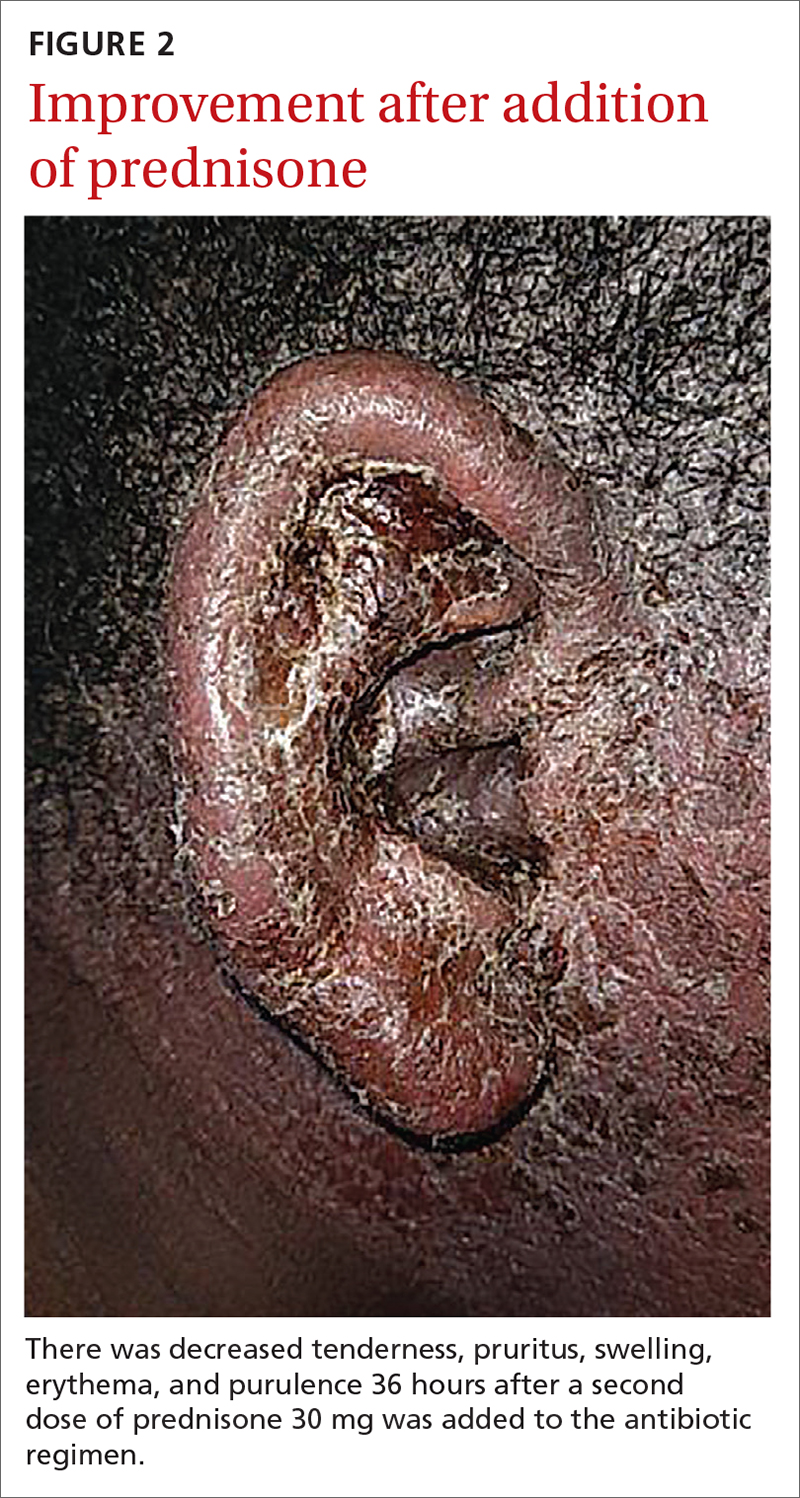

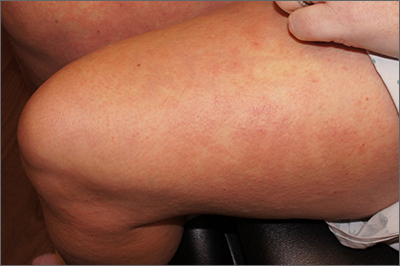

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

A 6-year-old boy was seen in the hospital in consultation for a 3-week history of suspected cellulitis of the right ear. Drainage from the right ear was refractory to treatment with a 7-day course of cephalexin 15 mL po bid of 250 mg/5 mL solution and clindamycin 24.4 mL po tid of 75 mg/5 mL solution. Treatment was followed by admission to the hospital for treatment with intravenous (IV) cefazolin 1000 mg q6h and IV vancomycin 825 mg q6h for 1 week.

The patient had a significant past medical history for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and severe atopic dermatitis that had been treated with methotrexate 10 mg per week for 6 months beginning when the child was 5 years of age. When the methotrexate proved to be ineffective, the patient was started on Aquaphor and mometasone 0.1% ointment. A 6-month trial of these agents failed as well.

Physical examination revealed that the right ear and skin around it were edematous, erythematous, pruritic, and tender. There was also purulent drainage coming from the ear (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infectious eczematoid dermatitis

The patient was referred to a dermatologist after seeing an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who made the diagnosis of otitis externa when the rash failed to respond to topical and systemic antibiotics. The patient’s tender, pruritic, oozing, edematous eruption was recognized as an infectious eczematoid dermatitis (IED).

Although it is not an uncommon condition, IED may be underrecognized. It accounted for 2.9% of admissions to a dermatology-run inpatient service between 2000 and 2010.1 IED results from cutaneous sensitization to purulent drainage secondary to acute otitis externa or another primary infection.2 In fact, cultures from the purulent drainage in this patient grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The patient’s right otitis externa drainage may have been associated with the previous history of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is associated with an increased risk of skin infections due to decreased inflammatory mediators (defensins).

Cellulitis and herpes zoster oticus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes bacterial cellulitis, acute otitis media, and herpes zoster oticus.

Bacterial cellulitis manifests with erythema, edema, and tenderness with blistering when associated with bullous impetigo rather than pruritus. The clinical appearance of the patient’s diffuse, weeping, edematous external ear, the lack of response to guided antibiotic therapy, and the pruritus experienced by the patient argue against the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis.

Acute otitis media, like otitis externa, produces ear discharge usually associated with significant pain. Thus, it is important when working through the differential to define the source of the ear discharge. In this case, a consultation with an ENT specialist confirmed that there was an intact tympanic membrane with no middle ear involvement, ruling out the diagnosis of acute otitis media.

Continue to: Herpes zoster oticus

Herpes zoster oticus. The absence of grouped vesicles at any point during the eruption, itching rather than pain, and negative viral culture and polymerase chain reaction studies for herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus excluded the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus.

Diagnostic criteria were met

This case was compatible with the characterizations of IED as initially described by Engman3 in 1902 and further detailed by Sutton,4 who provided the following criteria for diagnosis:

- an initial eczematous or pustular lesion

- extension peripherally by autoinoculation

- an absence of central clearing

- Staphylococcus on culture of the initial lesion

- a history of infection.

Case reports have added to our understanding of the mechanism of autosensitization of surrounding skin.5 Yamany and Schwartz have proposed the diagnostic criteria summarized in the TABLE.2

Age factors into location. The ears, nose, and face are predominantly involved in cases of IED in the pediatric population, while the lower extremities are predominantly involved in adults.6 Laboratory tests and imaging may aid in excluding other potential diagnoses or complications, but the diagnosis remains clinical and requires the clinician to avoid jumping to the conclusion that every moist, erythematous crusting eruption is purely infectious in nature.

Tx and prevention hinge on a combination of antibiotics, steroids

The management of IED should be aimed at fighting the infection, eliminating the allergic contact dermatitis associated with infectious products, and improving barrier protection. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics guided by culture focus on killing bacteria. The allergic immune response is dampened by systemic steroids. Topical steroids, however, are difficult to utilize on moist, draining skin. In the case of otitis externa, a combination topical antibiotic and steroid otic drop can be utilized. As healing begins, emollients are applied to aid in skin repair.2 Topical antibiotics containing neomycin or polymyxin should be avoided to eliminate the possibility of developing contact sensitivity to these agents.

For our patient, inpatient wound cultures demonstrated methicillin-resistant S aureus, and empiric treatment with IV cefepime and vancomycin was transitioned to IV clindamycin based on sensitivities and then transitioned to a 12-day course of oral clindamycin 150 mg bid. In addition, the patient received ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic drops 3 times/d to treat his otitis externa. After initiating prednisone 30 mg (1 mg/kg/d) for 10 days to cover the allergic component, the patient showed prompt clinical improvement. Gentle cleansing of the right ear with hypoallergenic soap and water followed by application of petrolatum ointment 4 times/d was used to promote healing and improve barrier function (FIGURE 2). The patient’s mother indicated during a follow-up call that the affected area had dramatically improved.

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

1. Storan ER, McEvoy MT, Wetter DA, et al. Experience with the dermatology inpatient hospital service for adults: Mayo Clinic, 2000–2010. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1360-1365. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12010

2. Yamany T, Schwartz RA. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:203-208. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12715

. An infectious form of an eczematoid dermatitis. St. Louis Courier of Med. 1902;27:401414.

4. Infectious eczematoid dermatitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1920;75:976-979.

, , . Autosensitization dermatitis: report of five cases and protocol of an experiment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;59:68-77. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01520260072010

, . Autosensitization in infectious eczematoid dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;62:703-704. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1950.01530180092021

Targetoid eruption

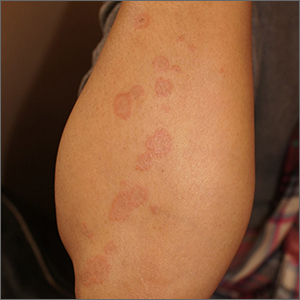

The clinical features of targetoid lesions occurring soon after herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection points to a diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM), which was confirmed by punch biopsy. The differential diagnosis for targetoid small lesions includes granuloma annulare, pityriasis rosea, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Larger targetoid lesions would be more concerning for erythema migrans (Lyme disease), tumid lupus, and severe tinea corporis.

Erythema multiforme represents an immune reaction triggered most often by HSV. About 10% of cases are triggered by exposure to various other viruses, drugs, and bacteria—notably, Mycoplasma pneumonia.1 Symptoms vary from mildly uncomfortable crops of annular and targetoid plaques to widespread annular plaques and bullae.

In the past, EM was considered a clinical variant along a continuum with Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Although mucosal involvement may occur with EM, it never progresses to SJS or TEN. The latter 2 diagnoses are associated with significant skin pain, dusky confluent patches, and a positive Nikolsky sign—wherein skin pressure causes superficial separation of the epidermis. Additionally, SJS and TEN tend to involve the trunk, whereas EM typically involves acral surfaces.

EM is self-limited but may recur in patients with additional HSV flares. Patients with frequent recurrences benefit from long-term suppression of HSV with valacyclovir 500 mg bid. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cool compresses control mild pain. Itching may be relieved with topical, medium-potency steroids or oral antihistamines. Oral ulcers or lesions may be treated with lidocaine oral suspension. Systemic steroids are contraindicated for mild disease, but they have a somewhat controversial role in alleviating severe symptoms.

This patient had mild symptoms and tolerated topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid without recurrence at 6 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

The clinical features of targetoid lesions occurring soon after herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection points to a diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM), which was confirmed by punch biopsy. The differential diagnosis for targetoid small lesions includes granuloma annulare, pityriasis rosea, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Larger targetoid lesions would be more concerning for erythema migrans (Lyme disease), tumid lupus, and severe tinea corporis.

Erythema multiforme represents an immune reaction triggered most often by HSV. About 10% of cases are triggered by exposure to various other viruses, drugs, and bacteria—notably, Mycoplasma pneumonia.1 Symptoms vary from mildly uncomfortable crops of annular and targetoid plaques to widespread annular plaques and bullae.

In the past, EM was considered a clinical variant along a continuum with Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Although mucosal involvement may occur with EM, it never progresses to SJS or TEN. The latter 2 diagnoses are associated with significant skin pain, dusky confluent patches, and a positive Nikolsky sign—wherein skin pressure causes superficial separation of the epidermis. Additionally, SJS and TEN tend to involve the trunk, whereas EM typically involves acral surfaces.

EM is self-limited but may recur in patients with additional HSV flares. Patients with frequent recurrences benefit from long-term suppression of HSV with valacyclovir 500 mg bid. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cool compresses control mild pain. Itching may be relieved with topical, medium-potency steroids or oral antihistamines. Oral ulcers or lesions may be treated with lidocaine oral suspension. Systemic steroids are contraindicated for mild disease, but they have a somewhat controversial role in alleviating severe symptoms.

This patient had mild symptoms and tolerated topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid without recurrence at 6 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The clinical features of targetoid lesions occurring soon after herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection points to a diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM), which was confirmed by punch biopsy. The differential diagnosis for targetoid small lesions includes granuloma annulare, pityriasis rosea, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Larger targetoid lesions would be more concerning for erythema migrans (Lyme disease), tumid lupus, and severe tinea corporis.

Erythema multiforme represents an immune reaction triggered most often by HSV. About 10% of cases are triggered by exposure to various other viruses, drugs, and bacteria—notably, Mycoplasma pneumonia.1 Symptoms vary from mildly uncomfortable crops of annular and targetoid plaques to widespread annular plaques and bullae.

In the past, EM was considered a clinical variant along a continuum with Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Although mucosal involvement may occur with EM, it never progresses to SJS or TEN. The latter 2 diagnoses are associated with significant skin pain, dusky confluent patches, and a positive Nikolsky sign—wherein skin pressure causes superficial separation of the epidermis. Additionally, SJS and TEN tend to involve the trunk, whereas EM typically involves acral surfaces.

EM is self-limited but may recur in patients with additional HSV flares. Patients with frequent recurrences benefit from long-term suppression of HSV with valacyclovir 500 mg bid. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cool compresses control mild pain. Itching may be relieved with topical, medium-potency steroids or oral antihistamines. Oral ulcers or lesions may be treated with lidocaine oral suspension. Systemic steroids are contraindicated for mild disease, but they have a somewhat controversial role in alleviating severe symptoms.

This patient had mild symptoms and tolerated topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid without recurrence at 6 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

Nodules on the arm

Excisional biopsy was performed on a small tumor and immune staining suggested lung cancer as the primary source.

Metastatic cancer of an unknown primary source accounts for 3% to 5% of invasive cancers.1 Poorly differentiated SCC, as in this case, may arise from skin, lung, or head and neck SCC. Risks of metastatic disease in cutaneous SCC include size greater than 2 cm, depth greater than 2 mm, and location on the ear, hand, lip, or within a burn.2 Recurrent tumors, poorly differentiated tumors, and tumors demonstrating perineural invasion also increase the risk of metastasis.

Having failed both previous treatments, further tissue characterization offered some hope of effective immunotherapy. Specifically, SCC from lung cancer as a primary source may express programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1), a transmembrane protein that suppresses adaptive immune responses. Pembrolizumab inhibits this molecule leading to a more aggressive immune response to tumor cells. Additionally, tumor profiling of specific oncogenes can highlight potentially beneficial therapies.

In this case, gene profiling identified several active tumor oncogenes, but PD-L1 was not strongly expressed. Despite the effort, this process did not uncover practical or novel treatment options. The patient was offered an empiric trial of immunotherapy but opted to pursue palliative therapy alone and passed away 2 months later.

This case highlights the role of multidisciplinary care of metastatic disease to the skin and the potential role, and limitations, of skin biopsy in tumor profiling and treatment guidance. Even though the most likely primary site was lung, cutaneous metastases can be equally devastating.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379:1428-1435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61178-1

2. Brougham NDLS, Dennett ER, Cameron R, et al. The incidence of metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of its risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:811-815. doi: 10.1002/jso.23155

Excisional biopsy was performed on a small tumor and immune staining suggested lung cancer as the primary source.

Metastatic cancer of an unknown primary source accounts for 3% to 5% of invasive cancers.1 Poorly differentiated SCC, as in this case, may arise from skin, lung, or head and neck SCC. Risks of metastatic disease in cutaneous SCC include size greater than 2 cm, depth greater than 2 mm, and location on the ear, hand, lip, or within a burn.2 Recurrent tumors, poorly differentiated tumors, and tumors demonstrating perineural invasion also increase the risk of metastasis.

Having failed both previous treatments, further tissue characterization offered some hope of effective immunotherapy. Specifically, SCC from lung cancer as a primary source may express programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1), a transmembrane protein that suppresses adaptive immune responses. Pembrolizumab inhibits this molecule leading to a more aggressive immune response to tumor cells. Additionally, tumor profiling of specific oncogenes can highlight potentially beneficial therapies.

In this case, gene profiling identified several active tumor oncogenes, but PD-L1 was not strongly expressed. Despite the effort, this process did not uncover practical or novel treatment options. The patient was offered an empiric trial of immunotherapy but opted to pursue palliative therapy alone and passed away 2 months later.

This case highlights the role of multidisciplinary care of metastatic disease to the skin and the potential role, and limitations, of skin biopsy in tumor profiling and treatment guidance. Even though the most likely primary site was lung, cutaneous metastases can be equally devastating.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Excisional biopsy was performed on a small tumor and immune staining suggested lung cancer as the primary source.

Metastatic cancer of an unknown primary source accounts for 3% to 5% of invasive cancers.1 Poorly differentiated SCC, as in this case, may arise from skin, lung, or head and neck SCC. Risks of metastatic disease in cutaneous SCC include size greater than 2 cm, depth greater than 2 mm, and location on the ear, hand, lip, or within a burn.2 Recurrent tumors, poorly differentiated tumors, and tumors demonstrating perineural invasion also increase the risk of metastasis.

Having failed both previous treatments, further tissue characterization offered some hope of effective immunotherapy. Specifically, SCC from lung cancer as a primary source may express programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1), a transmembrane protein that suppresses adaptive immune responses. Pembrolizumab inhibits this molecule leading to a more aggressive immune response to tumor cells. Additionally, tumor profiling of specific oncogenes can highlight potentially beneficial therapies.

In this case, gene profiling identified several active tumor oncogenes, but PD-L1 was not strongly expressed. Despite the effort, this process did not uncover practical or novel treatment options. The patient was offered an empiric trial of immunotherapy but opted to pursue palliative therapy alone and passed away 2 months later.

This case highlights the role of multidisciplinary care of metastatic disease to the skin and the potential role, and limitations, of skin biopsy in tumor profiling and treatment guidance. Even though the most likely primary site was lung, cutaneous metastases can be equally devastating.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379:1428-1435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61178-1

2. Brougham NDLS, Dennett ER, Cameron R, et al. The incidence of metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of its risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:811-815. doi: 10.1002/jso.23155

1. Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379:1428-1435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61178-1

2. Brougham NDLS, Dennett ER, Cameron R, et al. The incidence of metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of its risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:811-815. doi: 10.1002/jso.23155

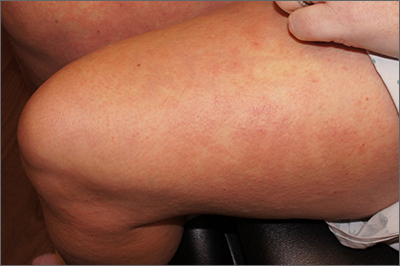

Rash after a medication change

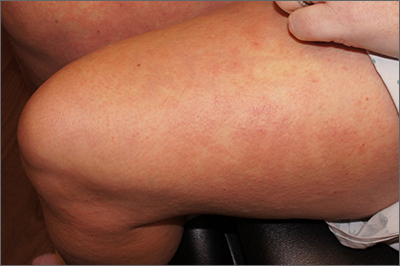

A punch biopsy revealed lichenoid interface dermatitis with eosinophils and mild spongiosis—consistent with, but not conclusive for, a drug eruption. A complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel revealed elevated levels of eosinophils and transaminases which raised the possibility of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. In this patient’s case, the transaminitis suggested some mild hepatitis; the liver is the most common organ involved in DRESS.

Diagnostic criteria for DRESS syndrome need not always be met but can include fever, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, and a morbilliform rash presenting 2 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. In this case, a lack of fever, facial edema, and other systemic symptoms favored a less severe drug eruption or what has been described as mini-DRESS.1 DRESS syndrome often merits hospitalization, and in 10% of cases it can be fatal.1

The patient in this case was started on prednisone 60 mg/d and her OCPs were discontinued. One week later, a repeat CBC showed normalized levels of eosinophils and transaminases. However, shortly after a 3-week taper of the prednisone, her levels of eosinophils and transaminases rose again. A repeat prednisone taper finally led to complete resolution of rash and sustained normalization of eosinophil and transaminase levels.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Isaacs M, Cardones AR, Rahnama-Moghadam S. DRESS syndrome: clinical myths and pearls. Cutis. 2018;102:322-326.

A punch biopsy revealed lichenoid interface dermatitis with eosinophils and mild spongiosis—consistent with, but not conclusive for, a drug eruption. A complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel revealed elevated levels of eosinophils and transaminases which raised the possibility of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. In this patient’s case, the transaminitis suggested some mild hepatitis; the liver is the most common organ involved in DRESS.

Diagnostic criteria for DRESS syndrome need not always be met but can include fever, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, and a morbilliform rash presenting 2 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. In this case, a lack of fever, facial edema, and other systemic symptoms favored a less severe drug eruption or what has been described as mini-DRESS.1 DRESS syndrome often merits hospitalization, and in 10% of cases it can be fatal.1

The patient in this case was started on prednisone 60 mg/d and her OCPs were discontinued. One week later, a repeat CBC showed normalized levels of eosinophils and transaminases. However, shortly after a 3-week taper of the prednisone, her levels of eosinophils and transaminases rose again. A repeat prednisone taper finally led to complete resolution of rash and sustained normalization of eosinophil and transaminase levels.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A punch biopsy revealed lichenoid interface dermatitis with eosinophils and mild spongiosis—consistent with, but not conclusive for, a drug eruption. A complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel revealed elevated levels of eosinophils and transaminases which raised the possibility of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. In this patient’s case, the transaminitis suggested some mild hepatitis; the liver is the most common organ involved in DRESS.

Diagnostic criteria for DRESS syndrome need not always be met but can include fever, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, and a morbilliform rash presenting 2 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. In this case, a lack of fever, facial edema, and other systemic symptoms favored a less severe drug eruption or what has been described as mini-DRESS.1 DRESS syndrome often merits hospitalization, and in 10% of cases it can be fatal.1

The patient in this case was started on prednisone 60 mg/d and her OCPs were discontinued. One week later, a repeat CBC showed normalized levels of eosinophils and transaminases. However, shortly after a 3-week taper of the prednisone, her levels of eosinophils and transaminases rose again. A repeat prednisone taper finally led to complete resolution of rash and sustained normalization of eosinophil and transaminase levels.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Isaacs M, Cardones AR, Rahnama-Moghadam S. DRESS syndrome: clinical myths and pearls. Cutis. 2018;102:322-326.

Isaacs M, Cardones AR, Rahnama-Moghadam S. DRESS syndrome: clinical myths and pearls. Cutis. 2018;102:322-326.

Scaly beard rash

Waxy loose scale with associated erythema on the face and scalp is a classic sign of seborrheic dermatitis (SD).

SD is caused by inflammation related to the presence of Malassezia, which proliferates on sebum-rich areas of skin. Malassezia is normally present on the skin, but some individuals have a heightened sensitivity to it, leading to erythema and scale. It is prudent to examine the scalp, nasolabial folds, and around the ears where it often occurs concomitantly.

There are multiple topical and systemic options which treat the fungal involvement, the subsequent inflammation, and reduce the scale.1 Topical azole antifungals are effective for reducing the amount of Malassezia present. Topical steroids work well to reduce the erythema. Fortunately, low-potency steroids, including hydrocortisone and desonide, are adequate. This is important since SD frequently involves the face and higher-potency steroids can cause skin atrophy or rebound erythema.

Salicylic acid products exfoliate the scale and topical tar products suppress the scale, both leading to clinical improvement. Sunlight and narrow beam UVB light therapy are also effective treatments. As was true with this patient, SD often improves during the summer months (when there is more sunlight) and when patients shave, as this allows for additional sun exposure to the skin.

The patient in this case was told to use ketoconazole shampoo for his scalp, beard, and mustache. He was instructed to use it at least 3 times per week, applying it to the scalp as the first part of his bathing routine and then waiting until the end to rinse it off. This technique maximizes the antifungal shampoo’s contact time on the skin. He was also given a prescription for ketoconazole cream to apply twice daily to the areas of facial erythema and scale. He was counseled that shaving his beard and mustache might help reduce the SD in those areas.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:158-169. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1473554

Waxy loose scale with associated erythema on the face and scalp is a classic sign of seborrheic dermatitis (SD).

SD is caused by inflammation related to the presence of Malassezia, which proliferates on sebum-rich areas of skin. Malassezia is normally present on the skin, but some individuals have a heightened sensitivity to it, leading to erythema and scale. It is prudent to examine the scalp, nasolabial folds, and around the ears where it often occurs concomitantly.

There are multiple topical and systemic options which treat the fungal involvement, the subsequent inflammation, and reduce the scale.1 Topical azole antifungals are effective for reducing the amount of Malassezia present. Topical steroids work well to reduce the erythema. Fortunately, low-potency steroids, including hydrocortisone and desonide, are adequate. This is important since SD frequently involves the face and higher-potency steroids can cause skin atrophy or rebound erythema.

Salicylic acid products exfoliate the scale and topical tar products suppress the scale, both leading to clinical improvement. Sunlight and narrow beam UVB light therapy are also effective treatments. As was true with this patient, SD often improves during the summer months (when there is more sunlight) and when patients shave, as this allows for additional sun exposure to the skin.

The patient in this case was told to use ketoconazole shampoo for his scalp, beard, and mustache. He was instructed to use it at least 3 times per week, applying it to the scalp as the first part of his bathing routine and then waiting until the end to rinse it off. This technique maximizes the antifungal shampoo’s contact time on the skin. He was also given a prescription for ketoconazole cream to apply twice daily to the areas of facial erythema and scale. He was counseled that shaving his beard and mustache might help reduce the SD in those areas.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Waxy loose scale with associated erythema on the face and scalp is a classic sign of seborrheic dermatitis (SD).

SD is caused by inflammation related to the presence of Malassezia, which proliferates on sebum-rich areas of skin. Malassezia is normally present on the skin, but some individuals have a heightened sensitivity to it, leading to erythema and scale. It is prudent to examine the scalp, nasolabial folds, and around the ears where it often occurs concomitantly.

There are multiple topical and systemic options which treat the fungal involvement, the subsequent inflammation, and reduce the scale.1 Topical azole antifungals are effective for reducing the amount of Malassezia present. Topical steroids work well to reduce the erythema. Fortunately, low-potency steroids, including hydrocortisone and desonide, are adequate. This is important since SD frequently involves the face and higher-potency steroids can cause skin atrophy or rebound erythema.

Salicylic acid products exfoliate the scale and topical tar products suppress the scale, both leading to clinical improvement. Sunlight and narrow beam UVB light therapy are also effective treatments. As was true with this patient, SD often improves during the summer months (when there is more sunlight) and when patients shave, as this allows for additional sun exposure to the skin.

The patient in this case was told to use ketoconazole shampoo for his scalp, beard, and mustache. He was instructed to use it at least 3 times per week, applying it to the scalp as the first part of his bathing routine and then waiting until the end to rinse it off. This technique maximizes the antifungal shampoo’s contact time on the skin. He was also given a prescription for ketoconazole cream to apply twice daily to the areas of facial erythema and scale. He was counseled that shaving his beard and mustache might help reduce the SD in those areas.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:158-169. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1473554

Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:158-169. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1473554

Foot rash and joint pain

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-month history of joint pain, swelling, and difficulty walking that began with swelling of his right knee (FIGURE 1A). The patient said that over the course of several weeks, the swelling and joint pain spread to his left knee, followed by bilateral elbows and ankles. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin produced only modest improvement.

Two weeks prior to presentation, the patient also experienced widespread pruritus and conjunctivitis. His past medical history was significant for a sexual encounter that resulted in urinary tract infection (UTI)–like symptoms approximately 1 month prior to the onset of his joint symptoms. He did not seek care for the UTI-like symptoms.

In the ED, the patient was febrile (102.1 °F) and tachycardic. Skin examination revealed erythematous papules, intact vesicles, and pustules with background hyperkeratosis and desquamation on his right foot (FIGURE 1B). The patient had spotty erythema on his palate and a 4-mm superficial erosion on the right penile shaft. Swelling and tenderness were noted over the elbows, knees, hands, and ankles. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted.

An arthrocentesis was performed on the right knee that demonstrated no organisms on Gram stain and a normal joint fluid cell count. A complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and urinalysis were ordered. A punch biopsy was performed on a scaly patch on the right elbow.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Keratoderma blenorrhagicum

The patient’s history, clinical findings, and lab results, including a positive Chlamydia trachomatis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test from a urethral swab, pointed to a diagnosis of keratoderma blenorrhagicum in association with reactive arthritis (following infection with C trachomatis).

Relevant diagnostic findings included an elevated CRP of 26.5 mg/L (normal range, < 10 mg/L), an elevated ESR of 116 mm/h (normal range, < 15 mm/h) and as noted, a positive C trachomatis PCR test. The patient’s white blood cell count was 9.7/μL (normal range, 4.5-11 μL) and the rest of the CBC was within normal limits. Urinalysis was positive for leukocytes and rare bacteria. A treponemal antibody test was negative.

Additionally, the punch biopsy from the right elbow revealed acanthosis, intercellular spongiosis, and subcorneal pustules consistent with localized pustular psoriasis or keratoderma blenorrhagicum. After the diagnosis was made, human leukocyte antigen B27 allele (HLA-B27) testing was conducted and was positive.

A predisposition exacerbates the infection

Reactive arthritis, a type of spondyloarthropathy, features a triad of conjunctivitis, urethritis, and arthritis that follows either gastrointestinal or urogenital infection.1 Reactive arthritis occurs with a male predominance of 3:1, and the worldwide prevalence is 1 in 3000.1 Causative bacteria include C trachomatis, Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile, and C pneumoniae.2 Patients with the HLA-B27 allele are 50 times more likely to develop reactive arthritis following infection with the aforementioned bacteria.1

Findings consistent with a diagnosis of reactive arthritis include a recent history of gastrointestinal or urogenital illness, joint pain, conjunctivitis, oral lesions, cutaneous changes, and genital lesions.3 Diagnostic tests should include arthrocentesis with cultures or PCR and cell count, ESR, CRP, CBC, and urinalysis. HLA-B27 can be used to support the diagnosis but is not routinely recommended.2

Pustules and psoriasiform scaling characterize this diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for the signs and symptoms seen in this patient include disseminated gonococcal arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and secondary syphilis.

Gonococcal arthritis manifests with painful, sterile joints as well as pustules on the palms and soles, but not with the psoriasiform scaling and desquamation that was seen in this case. A culture or PCR from urethral discharge or pustules on the palms and soles could be used to confirm this diagnosis.3

Continue to: Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis

Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis and the psoriasiform rashing of reactive arthritis (keratoderma blenorrhagicum) show similar histopathology; however, patients with psoriatic arthritis generally exhibit fewer constitutional symptoms.4

Rheumatoid arthritis also manifests with joint pain and swelling, especially in the hands, wrists, and knees. This diagnosis was unlikely in this patient, where small joints were largely uninvolved.4

Secondary syphilis also manifests with papular, scaly, erythematous lesions on the palms and soles along with pityriasis rosea–like rashing on the trunk. However, it rarely produces pustules or hyperkeratotic keratoderma.5 As noted earlier, a treponemal antibody test in this patient was negative.

Drug therapy is the best option

First-line therapy for reactive arthritis consists of NSAIDs. If the patient exhibits an inadequate response after a 2-week trial, intra-articular or systemic glucocorticoids may be considered.3 If the patient fails to respond to the steroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be considered. Reactive arthritis is considered chronic if the disease lasts longer than 6 months, at which point, DMARDs or tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors may be utilized.3 For cutaneous manifestations, such as keratoderma blenorrhagicum, topical glucocorticoids twice daily may be used along with keratolytic agents.

Our patient received 2 doses of azithromycin (500 mg IV) and 1 dose of ceftriaxone (2 g IV) to treat his infection while in the ED. Over the course of his hospital stay, he received ceftriaxone (1 g IV daily) for 6 days and naproxen (500 mg tid po) which was tapered. Additionally, he received a week of methylprednisolone (60 mg IM daily) before tapering to oral prednisone. His taper consisted of 40 mg po for 1 week and was decreased by 10 mg each week. Augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream and urea 20% cream were prescribed for twice-daily application for the hyperkeratotic scale on both of his feet.

1. Hayes KM, Hayes RJP, Turk MA, et al. Evolving patterns of reactive arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:2083-2088. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04522-4

2. Duba AS, Mathew SD. The seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Prim Care. 2018;45:271-287. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.005

3. Yu DT, van Tubergen A. Reactive arthritis. In: Joachim S, Romain PL, eds. UpToDate. Updated April 28, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis?search=reactive%20arthritis&topicRef=5571&source=see_link#H9

4. Barth WF, Segal K. Reactive arthritis (Reiter’s Syndrome). Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:499-503, 507.

5. Coleman E, Fiahlo A, Brateanu A. Secondary syphilis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:510-511. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84a.16089

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-month history of joint pain, swelling, and difficulty walking that began with swelling of his right knee (FIGURE 1A). The patient said that over the course of several weeks, the swelling and joint pain spread to his left knee, followed by bilateral elbows and ankles. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin produced only modest improvement.

Two weeks prior to presentation, the patient also experienced widespread pruritus and conjunctivitis. His past medical history was significant for a sexual encounter that resulted in urinary tract infection (UTI)–like symptoms approximately 1 month prior to the onset of his joint symptoms. He did not seek care for the UTI-like symptoms.

In the ED, the patient was febrile (102.1 °F) and tachycardic. Skin examination revealed erythematous papules, intact vesicles, and pustules with background hyperkeratosis and desquamation on his right foot (FIGURE 1B). The patient had spotty erythema on his palate and a 4-mm superficial erosion on the right penile shaft. Swelling and tenderness were noted over the elbows, knees, hands, and ankles. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted.

An arthrocentesis was performed on the right knee that demonstrated no organisms on Gram stain and a normal joint fluid cell count. A complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and urinalysis were ordered. A punch biopsy was performed on a scaly patch on the right elbow.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Keratoderma blenorrhagicum

The patient’s history, clinical findings, and lab results, including a positive Chlamydia trachomatis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test from a urethral swab, pointed to a diagnosis of keratoderma blenorrhagicum in association with reactive arthritis (following infection with C trachomatis).

Relevant diagnostic findings included an elevated CRP of 26.5 mg/L (normal range, < 10 mg/L), an elevated ESR of 116 mm/h (normal range, < 15 mm/h) and as noted, a positive C trachomatis PCR test. The patient’s white blood cell count was 9.7/μL (normal range, 4.5-11 μL) and the rest of the CBC was within normal limits. Urinalysis was positive for leukocytes and rare bacteria. A treponemal antibody test was negative.

Additionally, the punch biopsy from the right elbow revealed acanthosis, intercellular spongiosis, and subcorneal pustules consistent with localized pustular psoriasis or keratoderma blenorrhagicum. After the diagnosis was made, human leukocyte antigen B27 allele (HLA-B27) testing was conducted and was positive.

A predisposition exacerbates the infection

Reactive arthritis, a type of spondyloarthropathy, features a triad of conjunctivitis, urethritis, and arthritis that follows either gastrointestinal or urogenital infection.1 Reactive arthritis occurs with a male predominance of 3:1, and the worldwide prevalence is 1 in 3000.1 Causative bacteria include C trachomatis, Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile, and C pneumoniae.2 Patients with the HLA-B27 allele are 50 times more likely to develop reactive arthritis following infection with the aforementioned bacteria.1

Findings consistent with a diagnosis of reactive arthritis include a recent history of gastrointestinal or urogenital illness, joint pain, conjunctivitis, oral lesions, cutaneous changes, and genital lesions.3 Diagnostic tests should include arthrocentesis with cultures or PCR and cell count, ESR, CRP, CBC, and urinalysis. HLA-B27 can be used to support the diagnosis but is not routinely recommended.2

Pustules and psoriasiform scaling characterize this diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for the signs and symptoms seen in this patient include disseminated gonococcal arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and secondary syphilis.

Gonococcal arthritis manifests with painful, sterile joints as well as pustules on the palms and soles, but not with the psoriasiform scaling and desquamation that was seen in this case. A culture or PCR from urethral discharge or pustules on the palms and soles could be used to confirm this diagnosis.3

Continue to: Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis

Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis and the psoriasiform rashing of reactive arthritis (keratoderma blenorrhagicum) show similar histopathology; however, patients with psoriatic arthritis generally exhibit fewer constitutional symptoms.4

Rheumatoid arthritis also manifests with joint pain and swelling, especially in the hands, wrists, and knees. This diagnosis was unlikely in this patient, where small joints were largely uninvolved.4

Secondary syphilis also manifests with papular, scaly, erythematous lesions on the palms and soles along with pityriasis rosea–like rashing on the trunk. However, it rarely produces pustules or hyperkeratotic keratoderma.5 As noted earlier, a treponemal antibody test in this patient was negative.

Drug therapy is the best option

First-line therapy for reactive arthritis consists of NSAIDs. If the patient exhibits an inadequate response after a 2-week trial, intra-articular or systemic glucocorticoids may be considered.3 If the patient fails to respond to the steroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be considered. Reactive arthritis is considered chronic if the disease lasts longer than 6 months, at which point, DMARDs or tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors may be utilized.3 For cutaneous manifestations, such as keratoderma blenorrhagicum, topical glucocorticoids twice daily may be used along with keratolytic agents.

Our patient received 2 doses of azithromycin (500 mg IV) and 1 dose of ceftriaxone (2 g IV) to treat his infection while in the ED. Over the course of his hospital stay, he received ceftriaxone (1 g IV daily) for 6 days and naproxen (500 mg tid po) which was tapered. Additionally, he received a week of methylprednisolone (60 mg IM daily) before tapering to oral prednisone. His taper consisted of 40 mg po for 1 week and was decreased by 10 mg each week. Augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream and urea 20% cream were prescribed for twice-daily application for the hyperkeratotic scale on both of his feet.

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-month history of joint pain, swelling, and difficulty walking that began with swelling of his right knee (FIGURE 1A). The patient said that over the course of several weeks, the swelling and joint pain spread to his left knee, followed by bilateral elbows and ankles. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin produced only modest improvement.

Two weeks prior to presentation, the patient also experienced widespread pruritus and conjunctivitis. His past medical history was significant for a sexual encounter that resulted in urinary tract infection (UTI)–like symptoms approximately 1 month prior to the onset of his joint symptoms. He did not seek care for the UTI-like symptoms.

In the ED, the patient was febrile (102.1 °F) and tachycardic. Skin examination revealed erythematous papules, intact vesicles, and pustules with background hyperkeratosis and desquamation on his right foot (FIGURE 1B). The patient had spotty erythema on his palate and a 4-mm superficial erosion on the right penile shaft. Swelling and tenderness were noted over the elbows, knees, hands, and ankles. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted.

An arthrocentesis was performed on the right knee that demonstrated no organisms on Gram stain and a normal joint fluid cell count. A complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and urinalysis were ordered. A punch biopsy was performed on a scaly patch on the right elbow.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Keratoderma blenorrhagicum

The patient’s history, clinical findings, and lab results, including a positive Chlamydia trachomatis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test from a urethral swab, pointed to a diagnosis of keratoderma blenorrhagicum in association with reactive arthritis (following infection with C trachomatis).

Relevant diagnostic findings included an elevated CRP of 26.5 mg/L (normal range, < 10 mg/L), an elevated ESR of 116 mm/h (normal range, < 15 mm/h) and as noted, a positive C trachomatis PCR test. The patient’s white blood cell count was 9.7/μL (normal range, 4.5-11 μL) and the rest of the CBC was within normal limits. Urinalysis was positive for leukocytes and rare bacteria. A treponemal antibody test was negative.

Additionally, the punch biopsy from the right elbow revealed acanthosis, intercellular spongiosis, and subcorneal pustules consistent with localized pustular psoriasis or keratoderma blenorrhagicum. After the diagnosis was made, human leukocyte antigen B27 allele (HLA-B27) testing was conducted and was positive.

A predisposition exacerbates the infection

Reactive arthritis, a type of spondyloarthropathy, features a triad of conjunctivitis, urethritis, and arthritis that follows either gastrointestinal or urogenital infection.1 Reactive arthritis occurs with a male predominance of 3:1, and the worldwide prevalence is 1 in 3000.1 Causative bacteria include C trachomatis, Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile, and C pneumoniae.2 Patients with the HLA-B27 allele are 50 times more likely to develop reactive arthritis following infection with the aforementioned bacteria.1

Findings consistent with a diagnosis of reactive arthritis include a recent history of gastrointestinal or urogenital illness, joint pain, conjunctivitis, oral lesions, cutaneous changes, and genital lesions.3 Diagnostic tests should include arthrocentesis with cultures or PCR and cell count, ESR, CRP, CBC, and urinalysis. HLA-B27 can be used to support the diagnosis but is not routinely recommended.2

Pustules and psoriasiform scaling characterize this diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for the signs and symptoms seen in this patient include disseminated gonococcal arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and secondary syphilis.

Gonococcal arthritis manifests with painful, sterile joints as well as pustules on the palms and soles, but not with the psoriasiform scaling and desquamation that was seen in this case. A culture or PCR from urethral discharge or pustules on the palms and soles could be used to confirm this diagnosis.3

Continue to: Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis

Psoriasis in association with psoriatic arthritis and the psoriasiform rashing of reactive arthritis (keratoderma blenorrhagicum) show similar histopathology; however, patients with psoriatic arthritis generally exhibit fewer constitutional symptoms.4

Rheumatoid arthritis also manifests with joint pain and swelling, especially in the hands, wrists, and knees. This diagnosis was unlikely in this patient, where small joints were largely uninvolved.4

Secondary syphilis also manifests with papular, scaly, erythematous lesions on the palms and soles along with pityriasis rosea–like rashing on the trunk. However, it rarely produces pustules or hyperkeratotic keratoderma.5 As noted earlier, a treponemal antibody test in this patient was negative.

Drug therapy is the best option

First-line therapy for reactive arthritis consists of NSAIDs. If the patient exhibits an inadequate response after a 2-week trial, intra-articular or systemic glucocorticoids may be considered.3 If the patient fails to respond to the steroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be considered. Reactive arthritis is considered chronic if the disease lasts longer than 6 months, at which point, DMARDs or tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors may be utilized.3 For cutaneous manifestations, such as keratoderma blenorrhagicum, topical glucocorticoids twice daily may be used along with keratolytic agents.

Our patient received 2 doses of azithromycin (500 mg IV) and 1 dose of ceftriaxone (2 g IV) to treat his infection while in the ED. Over the course of his hospital stay, he received ceftriaxone (1 g IV daily) for 6 days and naproxen (500 mg tid po) which was tapered. Additionally, he received a week of methylprednisolone (60 mg IM daily) before tapering to oral prednisone. His taper consisted of 40 mg po for 1 week and was decreased by 10 mg each week. Augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream and urea 20% cream were prescribed for twice-daily application for the hyperkeratotic scale on both of his feet.

1. Hayes KM, Hayes RJP, Turk MA, et al. Evolving patterns of reactive arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:2083-2088. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04522-4

2. Duba AS, Mathew SD. The seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Prim Care. 2018;45:271-287. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.005

3. Yu DT, van Tubergen A. Reactive arthritis. In: Joachim S, Romain PL, eds. UpToDate. Updated April 28, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis?search=reactive%20arthritis&topicRef=5571&source=see_link#H9

4. Barth WF, Segal K. Reactive arthritis (Reiter’s Syndrome). Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:499-503, 507.

5. Coleman E, Fiahlo A, Brateanu A. Secondary syphilis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:510-511. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84a.16089

1. Hayes KM, Hayes RJP, Turk MA, et al. Evolving patterns of reactive arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:2083-2088. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04522-4

2. Duba AS, Mathew SD. The seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Prim Care. 2018;45:271-287. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.005

3. Yu DT, van Tubergen A. Reactive arthritis. In: Joachim S, Romain PL, eds. UpToDate. Updated April 28, 2021. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis?search=reactive%20arthritis&topicRef=5571&source=see_link#H9

4. Barth WF, Segal K. Reactive arthritis (Reiter’s Syndrome). Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:499-503, 507.

5. Coleman E, Fiahlo A, Brateanu A. Secondary syphilis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:510-511. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84a.16089

Rapidly growing hand nodule

Large, firm, erythematous, nodular lesions with central keratin plugs that arise rapidly are the hallmark of keratoacanthomas (KAs).

KAs commonly manifest on the hands and face and can alarm patients who are unfamiliar with their rapid growth. Since KAs can involute spontaneously after their growth and scarring phase, they were previously regarded as a benign lesion. KAs have a characteristic central keratin plug; this contrasts with basal cell carcinomas, which have central ulceration or scabbing. Currently, KAs are considered a subtype of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). KAs tend to grow much faster and are raised, unlike SCCs, which normally have scale surrounding macular or slightly raised erythematous tissue.

Treatments include surgical excision, cryosurgery, curettage with electrodesiccation, topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, intralesional methotrexate, or bleomycin.1 The isolated form of KAs is most common, but there are syndromes of multiple KAs that can be treated with systemic retinoids.

For this patient, the KA was transected across the base level with the surrounding skin and sent for pathology. At the same visit, the base was curetted down to the dermis and treated with electrodesiccation. This was followed by a repeat cycle of curettage and electrodesiccation. The patient was advised that if the pathology report showed invasive SCC, excision with margins would be recommended; otherwise, she would be followed clinically. Pathology did confirm a KA type of SCC. At the 6-week follow-up, the area was healing well, with no evidence of recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Panagiotopoulos A, Kyriazis N, Polychronaki E, et al. The effectiveness of cryosurgery combined with curettage and electrodessication in the treatment of keratoacanthoma: a retrospective analysis of 90 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:406-408. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_202_18

Large, firm, erythematous, nodular lesions with central keratin plugs that arise rapidly are the hallmark of keratoacanthomas (KAs).

KAs commonly manifest on the hands and face and can alarm patients who are unfamiliar with their rapid growth. Since KAs can involute spontaneously after their growth and scarring phase, they were previously regarded as a benign lesion. KAs have a characteristic central keratin plug; this contrasts with basal cell carcinomas, which have central ulceration or scabbing. Currently, KAs are considered a subtype of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). KAs tend to grow much faster and are raised, unlike SCCs, which normally have scale surrounding macular or slightly raised erythematous tissue.

Treatments include surgical excision, cryosurgery, curettage with electrodesiccation, topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, intralesional methotrexate, or bleomycin.1 The isolated form of KAs is most common, but there are syndromes of multiple KAs that can be treated with systemic retinoids.

For this patient, the KA was transected across the base level with the surrounding skin and sent for pathology. At the same visit, the base was curetted down to the dermis and treated with electrodesiccation. This was followed by a repeat cycle of curettage and electrodesiccation. The patient was advised that if the pathology report showed invasive SCC, excision with margins would be recommended; otherwise, she would be followed clinically. Pathology did confirm a KA type of SCC. At the 6-week follow-up, the area was healing well, with no evidence of recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Large, firm, erythematous, nodular lesions with central keratin plugs that arise rapidly are the hallmark of keratoacanthomas (KAs).

KAs commonly manifest on the hands and face and can alarm patients who are unfamiliar with their rapid growth. Since KAs can involute spontaneously after their growth and scarring phase, they were previously regarded as a benign lesion. KAs have a characteristic central keratin plug; this contrasts with basal cell carcinomas, which have central ulceration or scabbing. Currently, KAs are considered a subtype of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). KAs tend to grow much faster and are raised, unlike SCCs, which normally have scale surrounding macular or slightly raised erythematous tissue.

Treatments include surgical excision, cryosurgery, curettage with electrodesiccation, topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, intralesional methotrexate, or bleomycin.1 The isolated form of KAs is most common, but there are syndromes of multiple KAs that can be treated with systemic retinoids.

For this patient, the KA was transected across the base level with the surrounding skin and sent for pathology. At the same visit, the base was curetted down to the dermis and treated with electrodesiccation. This was followed by a repeat cycle of curettage and electrodesiccation. The patient was advised that if the pathology report showed invasive SCC, excision with margins would be recommended; otherwise, she would be followed clinically. Pathology did confirm a KA type of SCC. At the 6-week follow-up, the area was healing well, with no evidence of recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Panagiotopoulos A, Kyriazis N, Polychronaki E, et al. The effectiveness of cryosurgery combined with curettage and electrodessication in the treatment of keratoacanthoma: a retrospective analysis of 90 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:406-408. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_202_18

Panagiotopoulos A, Kyriazis N, Polychronaki E, et al. The effectiveness of cryosurgery combined with curettage and electrodessication in the treatment of keratoacanthoma: a retrospective analysis of 90 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:406-408. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_202_18

Erythematous axillary plaques

Due to the condition’s persistence and the negative KOH prep, erythrasma was the most likely diagnosis.

Erythrasma is caused by a bacterial infection with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It occurs in intertriginous areas that tend to be moist and irritated by friction. The erythema is usually a dull red, rather than the bright red that one would see with yeast infections. In addition, there is typically central pallor.

Woods lamp examination can confirm the diagnosis by showing coral pink fluorescence. In this patient, however, there was no fluorescence because the patient had recently washed the area and, thus, removed the porphyrins produced by C minutissimum. Biopsy for pathology is not usually necessary.

Erythrasma is treated with topical clindamycin, fusidic acid, or mupirocin. Oral macrolides and tetracyclines are also effective.1 Due to the chronicity of the erythrasma and the discomfort it caused, this patient opted for oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days. At follow-up 2 weeks later, the erythrasma had resolved.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

Due to the condition’s persistence and the negative KOH prep, erythrasma was the most likely diagnosis.

Erythrasma is caused by a bacterial infection with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It occurs in intertriginous areas that tend to be moist and irritated by friction. The erythema is usually a dull red, rather than the bright red that one would see with yeast infections. In addition, there is typically central pallor.

Woods lamp examination can confirm the diagnosis by showing coral pink fluorescence. In this patient, however, there was no fluorescence because the patient had recently washed the area and, thus, removed the porphyrins produced by C minutissimum. Biopsy for pathology is not usually necessary.

Erythrasma is treated with topical clindamycin, fusidic acid, or mupirocin. Oral macrolides and tetracyclines are also effective.1 Due to the chronicity of the erythrasma and the discomfort it caused, this patient opted for oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days. At follow-up 2 weeks later, the erythrasma had resolved.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Due to the condition’s persistence and the negative KOH prep, erythrasma was the most likely diagnosis.

Erythrasma is caused by a bacterial infection with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It occurs in intertriginous areas that tend to be moist and irritated by friction. The erythema is usually a dull red, rather than the bright red that one would see with yeast infections. In addition, there is typically central pallor.

Woods lamp examination can confirm the diagnosis by showing coral pink fluorescence. In this patient, however, there was no fluorescence because the patient had recently washed the area and, thus, removed the porphyrins produced by C minutissimum. Biopsy for pathology is not usually necessary.

Erythrasma is treated with topical clindamycin, fusidic acid, or mupirocin. Oral macrolides and tetracyclines are also effective.1 Due to the chronicity of the erythrasma and the discomfort it caused, this patient opted for oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days. At follow-up 2 weeks later, the erythrasma had resolved.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733