User login

Psychiatric consults: Documenting 6 essential elements

Written communication is an essential skill for a consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatrist, but unfortunately, how to write a consultation note is not part of formal didactics in medical school or residency training.1 Documentation of a consultation note is a permanent medical record entry that conveys current physician-to-physician information. While considerable literature describes the consultation process, little has been published about composing a consultation note.1,2 Residents and clinicians who do not have frequent consultations may be unfamiliar with the consultation environment and their role as an expert consultant. Therefore, more explicit guidance on documentation and optimal formatting of the consultation note is needed.

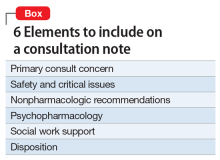

The Box provides an outline for completing the Recommendations/Treatment Plan section of psychiatric consultation notes. When providing your recommendations, it is best to use bullet points, numbering, or bold text; do not bury the information in a dense paragraph.3 Be sure to address each of the following 6 elements.

1. Primary consult concern. The first section of the Recommendations section should include the reason for the consult, which may be the most important part of the consultation process.1,2 It is important to recognize that an unclear consult question may be a sign of the primary team’s knowledge gap in psychiatry. The role of the C-L psychiatrist is to help the primary team organize their thoughts and concerns regarding their patient to decide on the final consult question.1 The active consult question may change as clinical issues evolve.

2. Safety and critical issues. Include an assessment of or recommendation on safety and critical issues. An important consideration is whether to recommend a patient sitter and to provide a reason for this recommendation. Occasionally, critical issues are more pressing than the primary consult concern. For example, there are several situations in which abnormal laboratory values and acute medical issues manifest as psychiatric symptoms, including hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, hypotension, low oxygen saturation, or infection. The connection between the 2 may not be clear to the primary treatment team; thus, include a statement to draw their attention to this.

3. Nonpharmacologic recommendations.

4. Psychopharmacology. In this section, the C-L psychiatrist should provide information on the use of any psychotropic medications and an explanation of their indications. If there are discrepancies between a patient’s home and hospital-ordered medications, clarify which medications the patient should be taking while hospitalized. If the C-L treatment team recommends initiating a new medication, provide details regarding the specific medication, dose, route, administration time, and titration schedule, as well as the specific situation for any as-needed medications. It is important to include the indication for any recommended medications, as well as any potential adverse effects. If psychotropic medications are not indicated, add a statement to emphasize this.

5. Social work support. Document any issues that need to be clarified by social work. This might include clarification of a patient’s insurance coverage, current living situation, or durable power of attorney. Also, document how the treatment team would prefer social work to assist with the patient’s care by (for example) providing the patient with resources for outpatient mental health and/or substance abuse treatment or housing options.

Continue to: Disposition

6. Disposition. Finally, include a recommendation regarding disposition. If transfer to a psychiatric facility is not indicated, provide a statement to affirm this. If transfer to a psychiatric facility is recommended, include a discussion of the patient’s appropriateness in the assessment and recommendations. It is helpful to inform the primary team of criteria that may or may not allow the patient to transfer to or be accepted by a psychiatry unit (eg, the patient will need to be off IV medications and able to tolerate oral intake prior to transfer). When transfer is not possible, communicate the reason to the primary treatment team and other ancillary staff.

Communicating responsibilities and expectations

After concluding the Recommendations section, end the consultation note with a brief sentence of gratitude (eg, “Thank you for this consultation and allowing us to assist in the care of your patient.”) and a comment regarding the C-L treatment team’s plan for follow-up. Also, include your contact information in case the primary treatment team has any questions or concerns.

The Recommendations section of a psychiatric consultation note is vital to convey current physician-to-physician recommendations. With the potential complexities in assessing and caring for a medically ill patient with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, psychiatrists with less C-L experience may be unfamiliar with the essential elements of a consultation note. It is helpful to use a Template to ensure that the consultation and documentation are complete.

1. Garrick TR, Stotland, NL. How to write a psychiatric consultation. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(7):849-855.

2. Alexander T, Bloch S. The written report in consultation-liaison psychiatry: a proposed schema. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(2):251-258.

3. von Gunten CF, Weissman DE. Writing the consultation note #267. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(5):579-580.

Written communication is an essential skill for a consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatrist, but unfortunately, how to write a consultation note is not part of formal didactics in medical school or residency training.1 Documentation of a consultation note is a permanent medical record entry that conveys current physician-to-physician information. While considerable literature describes the consultation process, little has been published about composing a consultation note.1,2 Residents and clinicians who do not have frequent consultations may be unfamiliar with the consultation environment and their role as an expert consultant. Therefore, more explicit guidance on documentation and optimal formatting of the consultation note is needed.

The Box provides an outline for completing the Recommendations/Treatment Plan section of psychiatric consultation notes. When providing your recommendations, it is best to use bullet points, numbering, or bold text; do not bury the information in a dense paragraph.3 Be sure to address each of the following 6 elements.

1. Primary consult concern. The first section of the Recommendations section should include the reason for the consult, which may be the most important part of the consultation process.1,2 It is important to recognize that an unclear consult question may be a sign of the primary team’s knowledge gap in psychiatry. The role of the C-L psychiatrist is to help the primary team organize their thoughts and concerns regarding their patient to decide on the final consult question.1 The active consult question may change as clinical issues evolve.

2. Safety and critical issues. Include an assessment of or recommendation on safety and critical issues. An important consideration is whether to recommend a patient sitter and to provide a reason for this recommendation. Occasionally, critical issues are more pressing than the primary consult concern. For example, there are several situations in which abnormal laboratory values and acute medical issues manifest as psychiatric symptoms, including hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, hypotension, low oxygen saturation, or infection. The connection between the 2 may not be clear to the primary treatment team; thus, include a statement to draw their attention to this.

3. Nonpharmacologic recommendations.

4. Psychopharmacology. In this section, the C-L psychiatrist should provide information on the use of any psychotropic medications and an explanation of their indications. If there are discrepancies between a patient’s home and hospital-ordered medications, clarify which medications the patient should be taking while hospitalized. If the C-L treatment team recommends initiating a new medication, provide details regarding the specific medication, dose, route, administration time, and titration schedule, as well as the specific situation for any as-needed medications. It is important to include the indication for any recommended medications, as well as any potential adverse effects. If psychotropic medications are not indicated, add a statement to emphasize this.

5. Social work support. Document any issues that need to be clarified by social work. This might include clarification of a patient’s insurance coverage, current living situation, or durable power of attorney. Also, document how the treatment team would prefer social work to assist with the patient’s care by (for example) providing the patient with resources for outpatient mental health and/or substance abuse treatment or housing options.

Continue to: Disposition

6. Disposition. Finally, include a recommendation regarding disposition. If transfer to a psychiatric facility is not indicated, provide a statement to affirm this. If transfer to a psychiatric facility is recommended, include a discussion of the patient’s appropriateness in the assessment and recommendations. It is helpful to inform the primary team of criteria that may or may not allow the patient to transfer to or be accepted by a psychiatry unit (eg, the patient will need to be off IV medications and able to tolerate oral intake prior to transfer). When transfer is not possible, communicate the reason to the primary treatment team and other ancillary staff.

Communicating responsibilities and expectations

After concluding the Recommendations section, end the consultation note with a brief sentence of gratitude (eg, “Thank you for this consultation and allowing us to assist in the care of your patient.”) and a comment regarding the C-L treatment team’s plan for follow-up. Also, include your contact information in case the primary treatment team has any questions or concerns.

The Recommendations section of a psychiatric consultation note is vital to convey current physician-to-physician recommendations. With the potential complexities in assessing and caring for a medically ill patient with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, psychiatrists with less C-L experience may be unfamiliar with the essential elements of a consultation note. It is helpful to use a Template to ensure that the consultation and documentation are complete.

Written communication is an essential skill for a consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatrist, but unfortunately, how to write a consultation note is not part of formal didactics in medical school or residency training.1 Documentation of a consultation note is a permanent medical record entry that conveys current physician-to-physician information. While considerable literature describes the consultation process, little has been published about composing a consultation note.1,2 Residents and clinicians who do not have frequent consultations may be unfamiliar with the consultation environment and their role as an expert consultant. Therefore, more explicit guidance on documentation and optimal formatting of the consultation note is needed.

The Box provides an outline for completing the Recommendations/Treatment Plan section of psychiatric consultation notes. When providing your recommendations, it is best to use bullet points, numbering, or bold text; do not bury the information in a dense paragraph.3 Be sure to address each of the following 6 elements.

1. Primary consult concern. The first section of the Recommendations section should include the reason for the consult, which may be the most important part of the consultation process.1,2 It is important to recognize that an unclear consult question may be a sign of the primary team’s knowledge gap in psychiatry. The role of the C-L psychiatrist is to help the primary team organize their thoughts and concerns regarding their patient to decide on the final consult question.1 The active consult question may change as clinical issues evolve.

2. Safety and critical issues. Include an assessment of or recommendation on safety and critical issues. An important consideration is whether to recommend a patient sitter and to provide a reason for this recommendation. Occasionally, critical issues are more pressing than the primary consult concern. For example, there are several situations in which abnormal laboratory values and acute medical issues manifest as psychiatric symptoms, including hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, hypotension, low oxygen saturation, or infection. The connection between the 2 may not be clear to the primary treatment team; thus, include a statement to draw their attention to this.

3. Nonpharmacologic recommendations.

4. Psychopharmacology. In this section, the C-L psychiatrist should provide information on the use of any psychotropic medications and an explanation of their indications. If there are discrepancies between a patient’s home and hospital-ordered medications, clarify which medications the patient should be taking while hospitalized. If the C-L treatment team recommends initiating a new medication, provide details regarding the specific medication, dose, route, administration time, and titration schedule, as well as the specific situation for any as-needed medications. It is important to include the indication for any recommended medications, as well as any potential adverse effects. If psychotropic medications are not indicated, add a statement to emphasize this.

5. Social work support. Document any issues that need to be clarified by social work. This might include clarification of a patient’s insurance coverage, current living situation, or durable power of attorney. Also, document how the treatment team would prefer social work to assist with the patient’s care by (for example) providing the patient with resources for outpatient mental health and/or substance abuse treatment or housing options.

Continue to: Disposition

6. Disposition. Finally, include a recommendation regarding disposition. If transfer to a psychiatric facility is not indicated, provide a statement to affirm this. If transfer to a psychiatric facility is recommended, include a discussion of the patient’s appropriateness in the assessment and recommendations. It is helpful to inform the primary team of criteria that may or may not allow the patient to transfer to or be accepted by a psychiatry unit (eg, the patient will need to be off IV medications and able to tolerate oral intake prior to transfer). When transfer is not possible, communicate the reason to the primary treatment team and other ancillary staff.

Communicating responsibilities and expectations

After concluding the Recommendations section, end the consultation note with a brief sentence of gratitude (eg, “Thank you for this consultation and allowing us to assist in the care of your patient.”) and a comment regarding the C-L treatment team’s plan for follow-up. Also, include your contact information in case the primary treatment team has any questions or concerns.

The Recommendations section of a psychiatric consultation note is vital to convey current physician-to-physician recommendations. With the potential complexities in assessing and caring for a medically ill patient with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, psychiatrists with less C-L experience may be unfamiliar with the essential elements of a consultation note. It is helpful to use a Template to ensure that the consultation and documentation are complete.

1. Garrick TR, Stotland, NL. How to write a psychiatric consultation. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(7):849-855.

2. Alexander T, Bloch S. The written report in consultation-liaison psychiatry: a proposed schema. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(2):251-258.

3. von Gunten CF, Weissman DE. Writing the consultation note #267. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(5):579-580.

1. Garrick TR, Stotland, NL. How to write a psychiatric consultation. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(7):849-855.

2. Alexander T, Bloch S. The written report in consultation-liaison psychiatry: a proposed schema. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(2):251-258.

3. von Gunten CF, Weissman DE. Writing the consultation note #267. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(5):579-580.

Tardive dyskinesia: 5 Steps for prevention

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is an elusive-to-treat adverse effect of antipsychotics that has caused extreme discomfort (in a literal and figurative sense) for patients and their psychiatrists. In 2017, the prevalence of TD as a result of exposure to dopamine antagonists was approximately 30% with first-generation antipsychotics and 20% with second-generation antipsychotics.1 There have been several effective attempts at reducing rates of TD, including lowering the dosing, shifting to second-generation antipsychotics, and using recently introduced pharmacologic treatments for TD. The past 2 years have seen increased efforts at treating this often-irreversible adverse effect with pharmacotherapy, such as the recently marketed vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2) inhibitors valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, as well as the supplement Ginkgo biloba,2 although issues with cost, adverse effects, or drug–drug interactions could limit the benefits of these agents.

Despite these strategies, one approach has been largely overlooked: prevention. Although it is included in many guidelines and literature reports, prevention has become less of a standard of practice and more of a cliché. Prevention is the key strategy for lowering the rate of TD, and it should be the assumed responsibility of each clinician in every prescription they write throughout the entire continuum of care. Here, we provide steps to take to help prevent TD, and what to consider when TD occurs.

1. Realize that we are all responsible for TD. We know TD exists, but we often feel that this adverse effect is not our fault. Avoid adapting a philosophy of “someone else caused it,” “they didn’t cause it yet,” or “it’s going to happen anyway.” We must remember that every unnecessary exposure to a dopamine antagonist increases the risk of TD, even if we don’t see the adverse effect firsthand.

2. Treat first-episode psychosis early and aggressively. Doing so may prevent chronicity of the illness, which would save a patient from long-term, high-dose exposure to antipsychotics. Lower the risk of TD with atypical antipsychotics and offer long-acting injectables when possible to improve medication adherence.

3. Treat both acute and chronic symptoms of psychosis throughout the continuum of care. The choice of medication and dose should be reevaluated at each interaction to enhance improvement of acute symptoms and to minimize chronic adverse effects. Always recognize the differences in aggressive treatment of an acute episode of psychosis vs maintenance treatment of baseline symptoms. Also, assess for TD by conducting abnormal involuntary movement scale (AIMS) examinations at baseline and at least biannually.

4. Use clozapine instead of 2 antipsychotics in chronic, refractory patients when possible. Clozapine is largely underutilize

5. Consider pharmacotherapy if TD has already occurred. Psychiatrists have been waiting for pharmacologic options for treating TD for quite some time. Explore using VMAT2 inhibitors and other agents when it is too late to implement prevention or when a patient’s symptoms are refractory to other treatments. However, avoid anticholinergic medications; there is insufficient data to support the use of these agents in the treatment of TD.5

1. Carbon M, Hsieh C, Kane J, et al. Tardive dyskinesia prevalence in the period of second-generation antipsychotic use: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):e264-e278.

2. Zheng W, Xiang Y, Ng H, et al. Extract of ginkgo biloba for tardive dyskinesia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2016;49(3):107-111.

3. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):686-693.

4. Barnes TR, Paton C. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia: benefits and risks. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(5):383-399.

5. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes. Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is an elusive-to-treat adverse effect of antipsychotics that has caused extreme discomfort (in a literal and figurative sense) for patients and their psychiatrists. In 2017, the prevalence of TD as a result of exposure to dopamine antagonists was approximately 30% with first-generation antipsychotics and 20% with second-generation antipsychotics.1 There have been several effective attempts at reducing rates of TD, including lowering the dosing, shifting to second-generation antipsychotics, and using recently introduced pharmacologic treatments for TD. The past 2 years have seen increased efforts at treating this often-irreversible adverse effect with pharmacotherapy, such as the recently marketed vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2) inhibitors valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, as well as the supplement Ginkgo biloba,2 although issues with cost, adverse effects, or drug–drug interactions could limit the benefits of these agents.

Despite these strategies, one approach has been largely overlooked: prevention. Although it is included in many guidelines and literature reports, prevention has become less of a standard of practice and more of a cliché. Prevention is the key strategy for lowering the rate of TD, and it should be the assumed responsibility of each clinician in every prescription they write throughout the entire continuum of care. Here, we provide steps to take to help prevent TD, and what to consider when TD occurs.

1. Realize that we are all responsible for TD. We know TD exists, but we often feel that this adverse effect is not our fault. Avoid adapting a philosophy of “someone else caused it,” “they didn’t cause it yet,” or “it’s going to happen anyway.” We must remember that every unnecessary exposure to a dopamine antagonist increases the risk of TD, even if we don’t see the adverse effect firsthand.

2. Treat first-episode psychosis early and aggressively. Doing so may prevent chronicity of the illness, which would save a patient from long-term, high-dose exposure to antipsychotics. Lower the risk of TD with atypical antipsychotics and offer long-acting injectables when possible to improve medication adherence.

3. Treat both acute and chronic symptoms of psychosis throughout the continuum of care. The choice of medication and dose should be reevaluated at each interaction to enhance improvement of acute symptoms and to minimize chronic adverse effects. Always recognize the differences in aggressive treatment of an acute episode of psychosis vs maintenance treatment of baseline symptoms. Also, assess for TD by conducting abnormal involuntary movement scale (AIMS) examinations at baseline and at least biannually.

4. Use clozapine instead of 2 antipsychotics in chronic, refractory patients when possible. Clozapine is largely underutilize

5. Consider pharmacotherapy if TD has already occurred. Psychiatrists have been waiting for pharmacologic options for treating TD for quite some time. Explore using VMAT2 inhibitors and other agents when it is too late to implement prevention or when a patient’s symptoms are refractory to other treatments. However, avoid anticholinergic medications; there is insufficient data to support the use of these agents in the treatment of TD.5

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is an elusive-to-treat adverse effect of antipsychotics that has caused extreme discomfort (in a literal and figurative sense) for patients and their psychiatrists. In 2017, the prevalence of TD as a result of exposure to dopamine antagonists was approximately 30% with first-generation antipsychotics and 20% with second-generation antipsychotics.1 There have been several effective attempts at reducing rates of TD, including lowering the dosing, shifting to second-generation antipsychotics, and using recently introduced pharmacologic treatments for TD. The past 2 years have seen increased efforts at treating this often-irreversible adverse effect with pharmacotherapy, such as the recently marketed vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2) inhibitors valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, as well as the supplement Ginkgo biloba,2 although issues with cost, adverse effects, or drug–drug interactions could limit the benefits of these agents.

Despite these strategies, one approach has been largely overlooked: prevention. Although it is included in many guidelines and literature reports, prevention has become less of a standard of practice and more of a cliché. Prevention is the key strategy for lowering the rate of TD, and it should be the assumed responsibility of each clinician in every prescription they write throughout the entire continuum of care. Here, we provide steps to take to help prevent TD, and what to consider when TD occurs.

1. Realize that we are all responsible for TD. We know TD exists, but we often feel that this adverse effect is not our fault. Avoid adapting a philosophy of “someone else caused it,” “they didn’t cause it yet,” or “it’s going to happen anyway.” We must remember that every unnecessary exposure to a dopamine antagonist increases the risk of TD, even if we don’t see the adverse effect firsthand.

2. Treat first-episode psychosis early and aggressively. Doing so may prevent chronicity of the illness, which would save a patient from long-term, high-dose exposure to antipsychotics. Lower the risk of TD with atypical antipsychotics and offer long-acting injectables when possible to improve medication adherence.

3. Treat both acute and chronic symptoms of psychosis throughout the continuum of care. The choice of medication and dose should be reevaluated at each interaction to enhance improvement of acute symptoms and to minimize chronic adverse effects. Always recognize the differences in aggressive treatment of an acute episode of psychosis vs maintenance treatment of baseline symptoms. Also, assess for TD by conducting abnormal involuntary movement scale (AIMS) examinations at baseline and at least biannually.

4. Use clozapine instead of 2 antipsychotics in chronic, refractory patients when possible. Clozapine is largely underutilize

5. Consider pharmacotherapy if TD has already occurred. Psychiatrists have been waiting for pharmacologic options for treating TD for quite some time. Explore using VMAT2 inhibitors and other agents when it is too late to implement prevention or when a patient’s symptoms are refractory to other treatments. However, avoid anticholinergic medications; there is insufficient data to support the use of these agents in the treatment of TD.5

1. Carbon M, Hsieh C, Kane J, et al. Tardive dyskinesia prevalence in the period of second-generation antipsychotic use: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):e264-e278.

2. Zheng W, Xiang Y, Ng H, et al. Extract of ginkgo biloba for tardive dyskinesia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2016;49(3):107-111.

3. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):686-693.

4. Barnes TR, Paton C. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia: benefits and risks. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(5):383-399.

5. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes. Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

1. Carbon M, Hsieh C, Kane J, et al. Tardive dyskinesia prevalence in the period of second-generation antipsychotic use: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):e264-e278.

2. Zheng W, Xiang Y, Ng H, et al. Extract of ginkgo biloba for tardive dyskinesia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2016;49(3):107-111.

3. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):686-693.

4. Barnes TR, Paton C. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia: benefits and risks. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(5):383-399.

5. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes. Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

Admission to an inpatient psychiatry unit or a medical unit? Consider 3 Ms and 3 Ps

Hospital psychiatrists often are asked whether a patient with comorbid medical and psychiatric illnesses should be admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit or to a medical unit. Psychiatric units vary widely in their capacity to manage patients’ medical conditions. Medical comorbidity also is associated with longer psychiatric hospitalizations.1 The decision of where to admit may be particularly challenging when presented with a patient with delirium, which often mimics primary psychiatric illnesses such as depression but will not resolve without treatment of the underlying illness. While diagnosis and treatment of delirium typically occur in the hospital setting, 1 study found that approximately 15% of 199 psychiatric inpatients were delirious and that these patients had hospital stays that were approximately 62% longer than those without delirium.2

When you need to determine whether a patient should be admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit with a medical consult or vice versa, consider the following 3 Ms and 3 Ps.

Medications. Can medications, including those that are given intravenously or require serum monitoring, be administered on the psychiatric unit? Can the medical unit administer involuntary psychotropics?

Mobility. Does the patient require assistance with mobility? Does the patient pose a fall risk? A physical therapy consult may be helpful.

Monitoring. Suicide risk is the most common indication for patient sitters.3 Would a patient sitter be needed for the patient? On the other hand, can the psychiatry unit manage telemetry, frequent vital signs, or infectious disease precautions?

People. Would the patient benefit from the therapeutic milieu and specialized staff of an inpatient psychiatry unit?

Prognosis. What ongoing medical and psychiatric management is required? What are the medical and psychiatric prognoses?

Placement. To where will the patient be transferred after hospitalization? How does admission to inpatient psychiatry vs medical impact the ultimate disposition?

Help the treatment team make the decision

Determining the ideal patient placement often evokes strong feelings among treatment teams. Psychiatrists can help facilitate the conversation by asking the questions outlined above, and by keeping in mind, “What is best for this patient?”

1. Rodrigues-Silva N, Ribeiro L. Impact of medical comorbidity in psychiatric inpatient length of stay. J Ment Health. 2017:1-5 [epub ahead of print].

2. Ritchie J, Steiner W, Abrahamowicz M. Incidence of and risk factors for delirium among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(7):727-730.

3. Solimine S, Takeshita J, Goebert D, et al. Characteristics of patients with constant observers. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(1):67-74.

Hospital psychiatrists often are asked whether a patient with comorbid medical and psychiatric illnesses should be admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit or to a medical unit. Psychiatric units vary widely in their capacity to manage patients’ medical conditions. Medical comorbidity also is associated with longer psychiatric hospitalizations.1 The decision of where to admit may be particularly challenging when presented with a patient with delirium, which often mimics primary psychiatric illnesses such as depression but will not resolve without treatment of the underlying illness. While diagnosis and treatment of delirium typically occur in the hospital setting, 1 study found that approximately 15% of 199 psychiatric inpatients were delirious and that these patients had hospital stays that were approximately 62% longer than those without delirium.2

When you need to determine whether a patient should be admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit with a medical consult or vice versa, consider the following 3 Ms and 3 Ps.

Medications. Can medications, including those that are given intravenously or require serum monitoring, be administered on the psychiatric unit? Can the medical unit administer involuntary psychotropics?

Mobility. Does the patient require assistance with mobility? Does the patient pose a fall risk? A physical therapy consult may be helpful.

Monitoring. Suicide risk is the most common indication for patient sitters.3 Would a patient sitter be needed for the patient? On the other hand, can the psychiatry unit manage telemetry, frequent vital signs, or infectious disease precautions?

People. Would the patient benefit from the therapeutic milieu and specialized staff of an inpatient psychiatry unit?

Prognosis. What ongoing medical and psychiatric management is required? What are the medical and psychiatric prognoses?

Placement. To where will the patient be transferred after hospitalization? How does admission to inpatient psychiatry vs medical impact the ultimate disposition?

Help the treatment team make the decision

Determining the ideal patient placement often evokes strong feelings among treatment teams. Psychiatrists can help facilitate the conversation by asking the questions outlined above, and by keeping in mind, “What is best for this patient?”

Hospital psychiatrists often are asked whether a patient with comorbid medical and psychiatric illnesses should be admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit or to a medical unit. Psychiatric units vary widely in their capacity to manage patients’ medical conditions. Medical comorbidity also is associated with longer psychiatric hospitalizations.1 The decision of where to admit may be particularly challenging when presented with a patient with delirium, which often mimics primary psychiatric illnesses such as depression but will not resolve without treatment of the underlying illness. While diagnosis and treatment of delirium typically occur in the hospital setting, 1 study found that approximately 15% of 199 psychiatric inpatients were delirious and that these patients had hospital stays that were approximately 62% longer than those without delirium.2

When you need to determine whether a patient should be admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit with a medical consult or vice versa, consider the following 3 Ms and 3 Ps.

Medications. Can medications, including those that are given intravenously or require serum monitoring, be administered on the psychiatric unit? Can the medical unit administer involuntary psychotropics?

Mobility. Does the patient require assistance with mobility? Does the patient pose a fall risk? A physical therapy consult may be helpful.

Monitoring. Suicide risk is the most common indication for patient sitters.3 Would a patient sitter be needed for the patient? On the other hand, can the psychiatry unit manage telemetry, frequent vital signs, or infectious disease precautions?

People. Would the patient benefit from the therapeutic milieu and specialized staff of an inpatient psychiatry unit?

Prognosis. What ongoing medical and psychiatric management is required? What are the medical and psychiatric prognoses?

Placement. To where will the patient be transferred after hospitalization? How does admission to inpatient psychiatry vs medical impact the ultimate disposition?

Help the treatment team make the decision

Determining the ideal patient placement often evokes strong feelings among treatment teams. Psychiatrists can help facilitate the conversation by asking the questions outlined above, and by keeping in mind, “What is best for this patient?”

1. Rodrigues-Silva N, Ribeiro L. Impact of medical comorbidity in psychiatric inpatient length of stay. J Ment Health. 2017:1-5 [epub ahead of print].

2. Ritchie J, Steiner W, Abrahamowicz M. Incidence of and risk factors for delirium among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(7):727-730.

3. Solimine S, Takeshita J, Goebert D, et al. Characteristics of patients with constant observers. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(1):67-74.

1. Rodrigues-Silva N, Ribeiro L. Impact of medical comorbidity in psychiatric inpatient length of stay. J Ment Health. 2017:1-5 [epub ahead of print].

2. Ritchie J, Steiner W, Abrahamowicz M. Incidence of and risk factors for delirium among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(7):727-730.

3. Solimine S, Takeshita J, Goebert D, et al. Characteristics of patients with constant observers. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(1):67-74.

How to handle unsolicited e-mails

The ubiquitous use of e-mail has opened the proverbial “Pandora’s box” of access to psychiatrists. Our e-mail addresses are readily available online via search engines or on hospital Web sites. E-mail has become a convenient method of communicating with patients; however, it also has resulted in a proliferation of unsolicited e-mails sent to physicians from people they don’t know seeking professional advice.1 If you publish medical literature or make media appearances, you may be contacted by such individuals requesting your expertise.

Unsolicited e-mails present psychiatrists with ethical and legal quandaries that force them to consider how they can balance the human reflex to offer assistance against the potential ramifications of replying. These conundrums include:

- whether the sender is an actual person, and whether he or she is asking for advice

- the risks of replying vs not replying

- the possibility that there is a plausible crisis or danger to the sender or others

- the potential for establishing a doctor–patient relationship by replying

- the legal liability that might be incurred by replying.2

Take preemptive measures

There is guidance on how to e-mail your patients and respond to solicited e-mails, but there is a dearth of literature on how to respond to unsolicited e-mails. Anecdotal reports and limited literature suggest several possible measures you could take for managing unsolicited e-mails:

- Establish a policy of never opening unsolicited e-mails

- Create a strict junk-mail filter to prevent unsolicited e-mails from being delivered to your inbox

- Set up an automatic reply stating that unwanted or unsolicited e-mails will not be read and/or that no reply will be provided

- Read unsolicited e-mails, but immediately delete them without replying

- Acknowledge the sender in a reply, but state that you are unable to assist and decline further contact

- Send a generic reply clarifying that you are unable to provide medical assistance, and encourage the sender to seek help locally.2

Despite the urge to help, consider the consequences

In addition to taking up valuable time, unsolicited e-mails create legal and ethical predicaments that could subject you to legal liability if you choose to reply. Even though your intentions may be altruistic and you want to be helpfu

1. D’Alessandro DM, D’Alessandro MP, Colbert S. A proposed solution for addressing the challenge of patient cries for help through an analysis of unsolicited electronic email. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):E74.

2. Friedman SH, Appel JM, Ash P, et al. Unsolicited e-mails to forensic psychiatrists. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2016;44(4):470-478.

The ubiquitous use of e-mail has opened the proverbial “Pandora’s box” of access to psychiatrists. Our e-mail addresses are readily available online via search engines or on hospital Web sites. E-mail has become a convenient method of communicating with patients; however, it also has resulted in a proliferation of unsolicited e-mails sent to physicians from people they don’t know seeking professional advice.1 If you publish medical literature or make media appearances, you may be contacted by such individuals requesting your expertise.

Unsolicited e-mails present psychiatrists with ethical and legal quandaries that force them to consider how they can balance the human reflex to offer assistance against the potential ramifications of replying. These conundrums include:

- whether the sender is an actual person, and whether he or she is asking for advice

- the risks of replying vs not replying

- the possibility that there is a plausible crisis or danger to the sender or others

- the potential for establishing a doctor–patient relationship by replying

- the legal liability that might be incurred by replying.2

Take preemptive measures

There is guidance on how to e-mail your patients and respond to solicited e-mails, but there is a dearth of literature on how to respond to unsolicited e-mails. Anecdotal reports and limited literature suggest several possible measures you could take for managing unsolicited e-mails:

- Establish a policy of never opening unsolicited e-mails

- Create a strict junk-mail filter to prevent unsolicited e-mails from being delivered to your inbox

- Set up an automatic reply stating that unwanted or unsolicited e-mails will not be read and/or that no reply will be provided

- Read unsolicited e-mails, but immediately delete them without replying

- Acknowledge the sender in a reply, but state that you are unable to assist and decline further contact

- Send a generic reply clarifying that you are unable to provide medical assistance, and encourage the sender to seek help locally.2

Despite the urge to help, consider the consequences

In addition to taking up valuable time, unsolicited e-mails create legal and ethical predicaments that could subject you to legal liability if you choose to reply. Even though your intentions may be altruistic and you want to be helpfu

The ubiquitous use of e-mail has opened the proverbial “Pandora’s box” of access to psychiatrists. Our e-mail addresses are readily available online via search engines or on hospital Web sites. E-mail has become a convenient method of communicating with patients; however, it also has resulted in a proliferation of unsolicited e-mails sent to physicians from people they don’t know seeking professional advice.1 If you publish medical literature or make media appearances, you may be contacted by such individuals requesting your expertise.

Unsolicited e-mails present psychiatrists with ethical and legal quandaries that force them to consider how they can balance the human reflex to offer assistance against the potential ramifications of replying. These conundrums include:

- whether the sender is an actual person, and whether he or she is asking for advice

- the risks of replying vs not replying

- the possibility that there is a plausible crisis or danger to the sender or others

- the potential for establishing a doctor–patient relationship by replying

- the legal liability that might be incurred by replying.2

Take preemptive measures

There is guidance on how to e-mail your patients and respond to solicited e-mails, but there is a dearth of literature on how to respond to unsolicited e-mails. Anecdotal reports and limited literature suggest several possible measures you could take for managing unsolicited e-mails:

- Establish a policy of never opening unsolicited e-mails

- Create a strict junk-mail filter to prevent unsolicited e-mails from being delivered to your inbox

- Set up an automatic reply stating that unwanted or unsolicited e-mails will not be read and/or that no reply will be provided

- Read unsolicited e-mails, but immediately delete them without replying

- Acknowledge the sender in a reply, but state that you are unable to assist and decline further contact

- Send a generic reply clarifying that you are unable to provide medical assistance, and encourage the sender to seek help locally.2

Despite the urge to help, consider the consequences

In addition to taking up valuable time, unsolicited e-mails create legal and ethical predicaments that could subject you to legal liability if you choose to reply. Even though your intentions may be altruistic and you want to be helpfu

1. D’Alessandro DM, D’Alessandro MP, Colbert S. A proposed solution for addressing the challenge of patient cries for help through an analysis of unsolicited electronic email. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):E74.

2. Friedman SH, Appel JM, Ash P, et al. Unsolicited e-mails to forensic psychiatrists. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2016;44(4):470-478.

1. D’Alessandro DM, D’Alessandro MP, Colbert S. A proposed solution for addressing the challenge of patient cries for help through an analysis of unsolicited electronic email. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):E74.

2. Friedman SH, Appel JM, Ash P, et al. Unsolicited e-mails to forensic psychiatrists. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2016;44(4):470-478.

Can mood stabilizers reduce chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder?

Misuse of prescription opioids has led to a staggering number of patients developing addiction, which the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified as a health care crisis. In the United States, approximately 29% of patients prescribed an opioid misuse it, and approximately 80% of heroin users started with prescription opioids.1,2 The NIH and HHS have outlined 5 priorities to help resolve this crisis:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services

- Increase availability and distribution of overdose-reversing medications

- As the epidemic changes, strengthen what we know with improved public health surveillance

- Support research that advances the understanding of pain and addiction and that develops new treatments and interventions

- Improve pain management by utilizing evidence-based practices and reducing opioid misuse and opiate-related harm.3

Treating chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder

At the Missouri University Psychiatric Center, an inpatient psychiatric ward, we recently conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify effective alternatives for treating pain, and to decrease opioid-related harm. Our study focused on 73 inpatients experiencing exacerbation of bipolar I disorder who also had chronic pain. These patients were treated with mood stabilizers, including lithium and carbamazepine. Patients also were taking medications, as needed, for agitation and their home medications for various medical problems. Selection of mood stabilizer therapy was non-random by standard of care based on best clinical practices. Dosing was based on blood-level monitoring adjusted to maintain therapeutic levels while receiving inpatient care. The average duration of inpatient treatment was approximately 1 to 5 weeks.

Pain was measured at baseline and compared with daily pain scores after mood stabilizer therapy using a 10-point scale, with 0 for no pain to 10 for worse pain, for the duration of the admission As expected based on the findings of previous research, carbamazepine resulted in a decrease in average daily pain score by 1.25 points after treatment (P = .048; F value = 4.3; F-crit = 4.23; calculated by one-way analysis of variance). However, patients who received lithium experienced a greater decrease in average daily pain score, by 2.17 points after treatment (P = .00035; F value = 14.56; F-crit = 4.02).

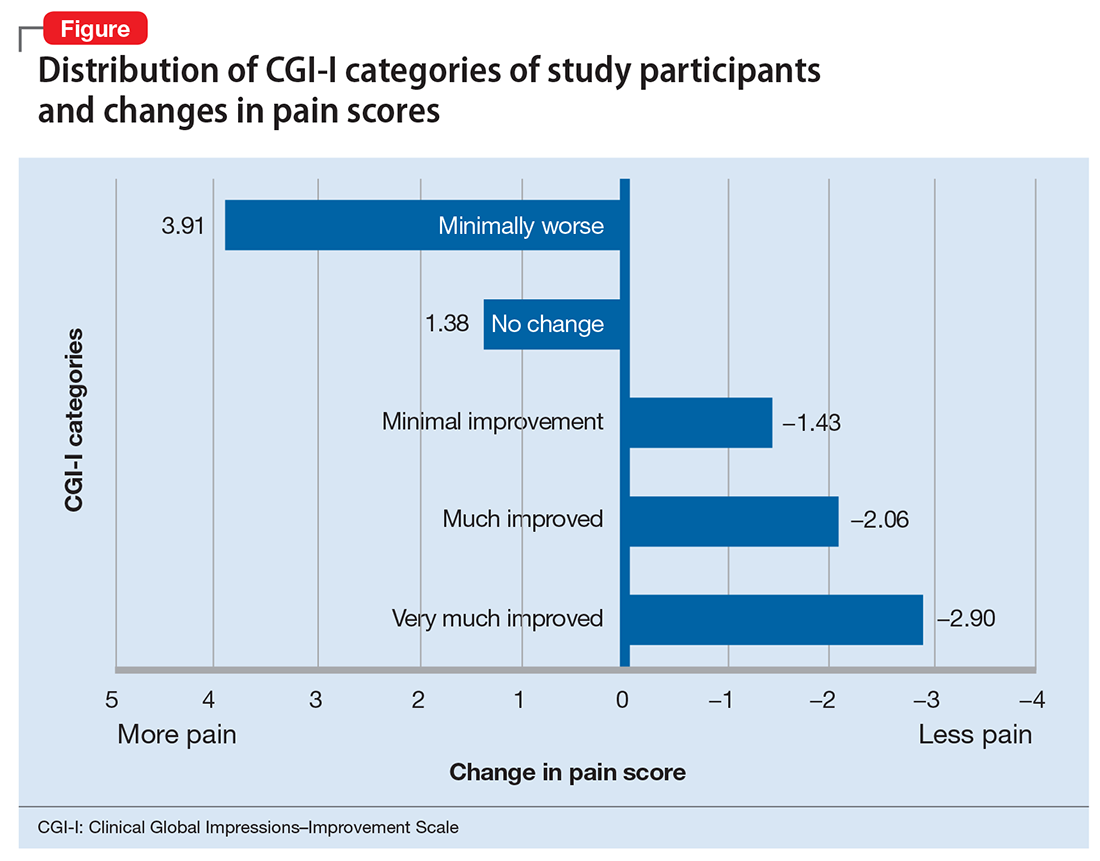

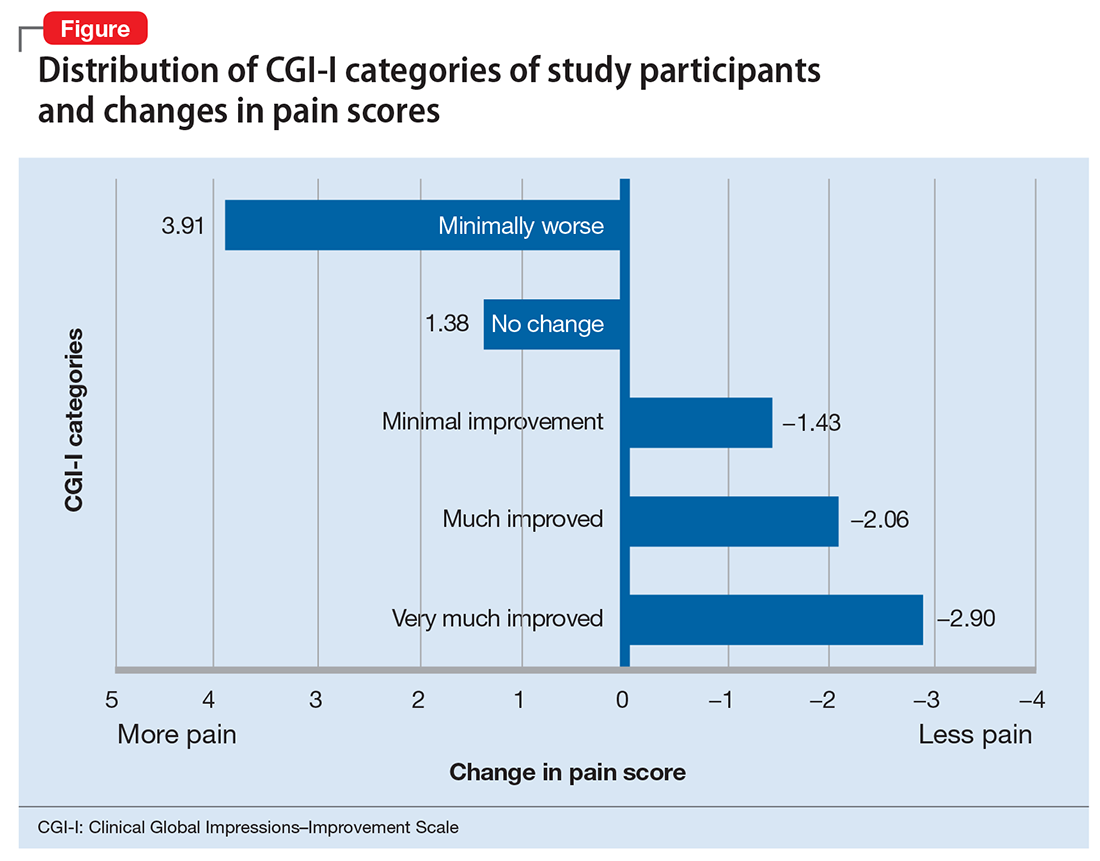

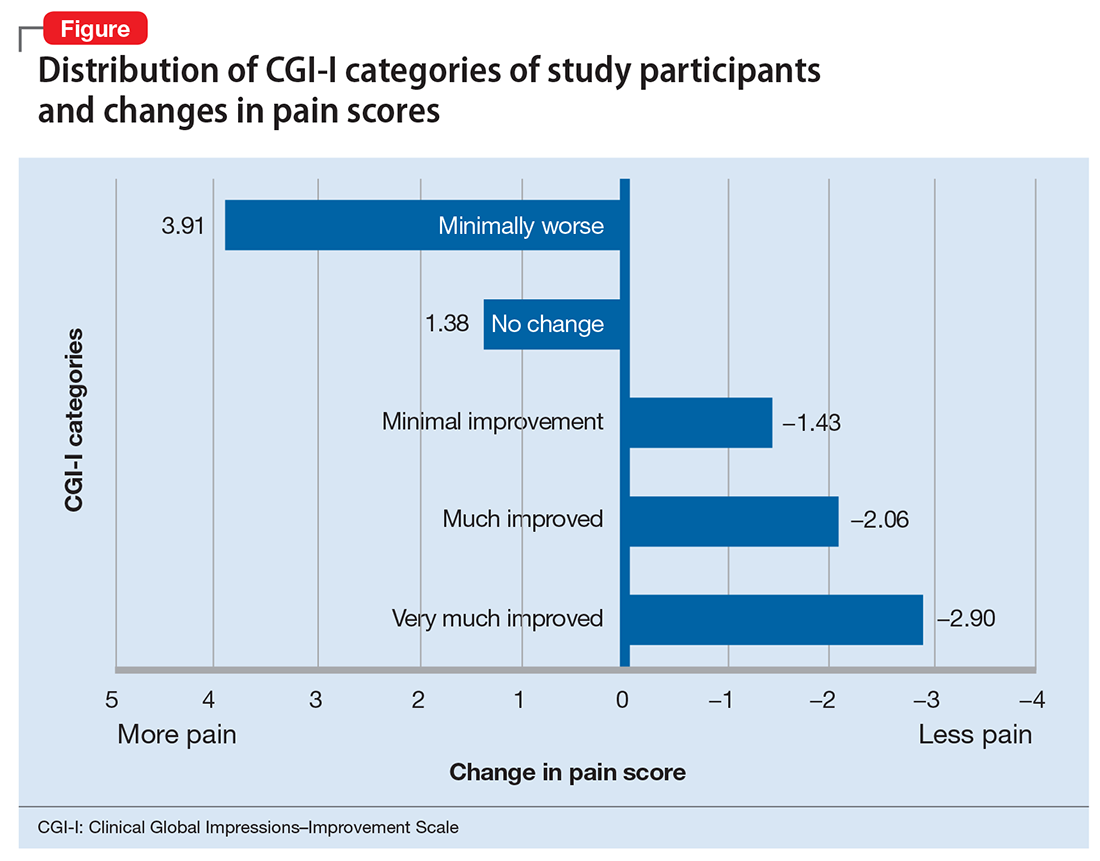

To further characterize the relationship between bipolar disorder and chronic pain, we looked at change in pain scores for mixed, manic, and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder by Clinical Global Impressions—Improvement (CGI-I) Scale categories (Figure). Participants who experienced the greatest clinical improvement also experienced the highest degree of analgesia. Those in the “Very much improved” CGI-I category experienced an almost 3-point decrease in average daily pain scores, with significance well below threshold (P = .0000967; F value = 19.83; F-crit = 4.11). Participants who showed no change in their bipolar I disorder symptoms or experienced exacerbation of their symptoms showed a significant increase in pain scores (P = .037; F value = 6.24; F-crit = 5.32).

Our data show that lithium and carbamazepine provide clinically and statistically significant analgesia in patients with bipolar I disorder and chronic pain. Furthermore, exacerbation of bipolar I disorder symptoms was associated with an increase of approximately 4 points on a 10-point chronic pain scale.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge contributions of Yajie Yu, MD, Sailaja Bysani, MD, Emily Leary, PhD, and Oluwole Popoola, MD, for their work in this study.

1. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569-576.

2. Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Rev. 2013.

3. National Institutes of Health. Department of Health and Human Services. Opiate crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-crisis. Updated January 2018. Accessed February 5, 2018.

Misuse of prescription opioids has led to a staggering number of patients developing addiction, which the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified as a health care crisis. In the United States, approximately 29% of patients prescribed an opioid misuse it, and approximately 80% of heroin users started with prescription opioids.1,2 The NIH and HHS have outlined 5 priorities to help resolve this crisis:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services

- Increase availability and distribution of overdose-reversing medications

- As the epidemic changes, strengthen what we know with improved public health surveillance

- Support research that advances the understanding of pain and addiction and that develops new treatments and interventions

- Improve pain management by utilizing evidence-based practices and reducing opioid misuse and opiate-related harm.3

Treating chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder

At the Missouri University Psychiatric Center, an inpatient psychiatric ward, we recently conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify effective alternatives for treating pain, and to decrease opioid-related harm. Our study focused on 73 inpatients experiencing exacerbation of bipolar I disorder who also had chronic pain. These patients were treated with mood stabilizers, including lithium and carbamazepine. Patients also were taking medications, as needed, for agitation and their home medications for various medical problems. Selection of mood stabilizer therapy was non-random by standard of care based on best clinical practices. Dosing was based on blood-level monitoring adjusted to maintain therapeutic levels while receiving inpatient care. The average duration of inpatient treatment was approximately 1 to 5 weeks.

Pain was measured at baseline and compared with daily pain scores after mood stabilizer therapy using a 10-point scale, with 0 for no pain to 10 for worse pain, for the duration of the admission As expected based on the findings of previous research, carbamazepine resulted in a decrease in average daily pain score by 1.25 points after treatment (P = .048; F value = 4.3; F-crit = 4.23; calculated by one-way analysis of variance). However, patients who received lithium experienced a greater decrease in average daily pain score, by 2.17 points after treatment (P = .00035; F value = 14.56; F-crit = 4.02).

To further characterize the relationship between bipolar disorder and chronic pain, we looked at change in pain scores for mixed, manic, and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder by Clinical Global Impressions—Improvement (CGI-I) Scale categories (Figure). Participants who experienced the greatest clinical improvement also experienced the highest degree of analgesia. Those in the “Very much improved” CGI-I category experienced an almost 3-point decrease in average daily pain scores, with significance well below threshold (P = .0000967; F value = 19.83; F-crit = 4.11). Participants who showed no change in their bipolar I disorder symptoms or experienced exacerbation of their symptoms showed a significant increase in pain scores (P = .037; F value = 6.24; F-crit = 5.32).

Our data show that lithium and carbamazepine provide clinically and statistically significant analgesia in patients with bipolar I disorder and chronic pain. Furthermore, exacerbation of bipolar I disorder symptoms was associated with an increase of approximately 4 points on a 10-point chronic pain scale.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge contributions of Yajie Yu, MD, Sailaja Bysani, MD, Emily Leary, PhD, and Oluwole Popoola, MD, for their work in this study.

Misuse of prescription opioids has led to a staggering number of patients developing addiction, which the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified as a health care crisis. In the United States, approximately 29% of patients prescribed an opioid misuse it, and approximately 80% of heroin users started with prescription opioids.1,2 The NIH and HHS have outlined 5 priorities to help resolve this crisis:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services

- Increase availability and distribution of overdose-reversing medications

- As the epidemic changes, strengthen what we know with improved public health surveillance

- Support research that advances the understanding of pain and addiction and that develops new treatments and interventions

- Improve pain management by utilizing evidence-based practices and reducing opioid misuse and opiate-related harm.3

Treating chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder

At the Missouri University Psychiatric Center, an inpatient psychiatric ward, we recently conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify effective alternatives for treating pain, and to decrease opioid-related harm. Our study focused on 73 inpatients experiencing exacerbation of bipolar I disorder who also had chronic pain. These patients were treated with mood stabilizers, including lithium and carbamazepine. Patients also were taking medications, as needed, for agitation and their home medications for various medical problems. Selection of mood stabilizer therapy was non-random by standard of care based on best clinical practices. Dosing was based on blood-level monitoring adjusted to maintain therapeutic levels while receiving inpatient care. The average duration of inpatient treatment was approximately 1 to 5 weeks.

Pain was measured at baseline and compared with daily pain scores after mood stabilizer therapy using a 10-point scale, with 0 for no pain to 10 for worse pain, for the duration of the admission As expected based on the findings of previous research, carbamazepine resulted in a decrease in average daily pain score by 1.25 points after treatment (P = .048; F value = 4.3; F-crit = 4.23; calculated by one-way analysis of variance). However, patients who received lithium experienced a greater decrease in average daily pain score, by 2.17 points after treatment (P = .00035; F value = 14.56; F-crit = 4.02).

To further characterize the relationship between bipolar disorder and chronic pain, we looked at change in pain scores for mixed, manic, and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder by Clinical Global Impressions—Improvement (CGI-I) Scale categories (Figure). Participants who experienced the greatest clinical improvement also experienced the highest degree of analgesia. Those in the “Very much improved” CGI-I category experienced an almost 3-point decrease in average daily pain scores, with significance well below threshold (P = .0000967; F value = 19.83; F-crit = 4.11). Participants who showed no change in their bipolar I disorder symptoms or experienced exacerbation of their symptoms showed a significant increase in pain scores (P = .037; F value = 6.24; F-crit = 5.32).

Our data show that lithium and carbamazepine provide clinically and statistically significant analgesia in patients with bipolar I disorder and chronic pain. Furthermore, exacerbation of bipolar I disorder symptoms was associated with an increase of approximately 4 points on a 10-point chronic pain scale.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge contributions of Yajie Yu, MD, Sailaja Bysani, MD, Emily Leary, PhD, and Oluwole Popoola, MD, for their work in this study.

1. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569-576.

2. Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Rev. 2013.

3. National Institutes of Health. Department of Health and Human Services. Opiate crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-crisis. Updated January 2018. Accessed February 5, 2018.

1. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569-576.

2. Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Rev. 2013.

3. National Institutes of Health. Department of Health and Human Services. Opiate crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-crisis. Updated January 2018. Accessed February 5, 2018.

4 Ways to help your patients with schizophrenia quit smoking

Tobacco-related cardiovascular disease is the primary reason adults with schizophrenia die on average 28 years earlier than their peers in the U.S. general population.1 To address this, clinicians need to prioritize smoking cessation and emphasize to patients with schizophrenia that quitting is the most important change they can make to improve their health. Here are 4 ways to help patients with schizophrenia quit smoking.

Provide hope, but be realistic. Most patients with schizophrenia who smoke want to quit; however, patients and clinicians alike have been discouraged by low quit rates and high relapse rates. Smoking often is viewed as one of the few remaining personal freedoms, as a lower priority than active psychiatric symptoms, or even as neuroprotective. By perpetuating these falsehoods and avoiding addressing smoking cessation, we are failing our patients.

With persistent engagement and use of effective pharmacotherapeutic interventions, smoking cessation is attainable and does not worsen psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, smoking cessation could save patients >$4,000 a year. It is crucial to make smoking cessation a priority at every appointment, and to offer patients hope and practical guidance through repeated attempts to quit.

Offer varenicline. For patients with schizophrenia, cessation counseling or behavioral interventions alone have a poor efficacy rate of approximately 5% (compared with 15% to 20% in the general population).2 Varenicline is the most effective smoking cessation treatment; it increases cessation rates 5-fold among patients with schizophrenia.3 As demonstrated by the Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES),4 varenicline does not lead to an increased risk of suicidality or serious neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

When starting a patient on varenicline, set a quit date 4 weeks from medication initiation. Individuals with schizophrenia often have a greater smoking burden and experience more intense symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. A 4-week period between medication initiation and the quit date will allow these patients to gradually experience reduced cravings and separate minor adverse effects of the medication from those of nicotine withdrawal. Concurrent prescription of nicotine replacement therapy (eg, patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler) also is safe and can assist in quit attempts.

Consider varenicline maintenance therapy. After a successful quit attempt, increase the likelihood of sustained cessation by continuing varenicline beyond 12 weeks. Varenicline can be used as a maintenance medication to prevent smoking relapse in patients with schizophrenia; when prescribed to these patients for an additional 3 months, it can reduce the relapse rate similarly to that seen in smokers in the general population.5

Adjust antipsychotic dosages. Tobacco smoke increases the activity of cytochrome P450 1A2, which metabolizes several antipsychotics. Thus, after successful smoking cessation, concentrations of clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, and olanzapine may increase, and dose reduction may be warranted. Conversely, if a patient resumes smoking, dosages of these medications may need to be increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Eden Evins, MD, MPH, and Corinne Cather, PhD, for their input on this article.

1. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

2. Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2(2):CD007253.

3. Evins AE, Benowitz N, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion vs. nicotine patch and placebo in the psychiatric cohort of the EAGLES trial. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 22nd Annual Meeting; March 2-5, 2016; Chicago, IL.

4. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

5. Evins AE, Hoeppner SS, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Maintenance pharmacotherapy normalizes the relapse curve in recently abstinent tobacco smokers with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:124-129.

Tobacco-related cardiovascular disease is the primary reason adults with schizophrenia die on average 28 years earlier than their peers in the U.S. general population.1 To address this, clinicians need to prioritize smoking cessation and emphasize to patients with schizophrenia that quitting is the most important change they can make to improve their health. Here are 4 ways to help patients with schizophrenia quit smoking.

Provide hope, but be realistic. Most patients with schizophrenia who smoke want to quit; however, patients and clinicians alike have been discouraged by low quit rates and high relapse rates. Smoking often is viewed as one of the few remaining personal freedoms, as a lower priority than active psychiatric symptoms, or even as neuroprotective. By perpetuating these falsehoods and avoiding addressing smoking cessation, we are failing our patients.

With persistent engagement and use of effective pharmacotherapeutic interventions, smoking cessation is attainable and does not worsen psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, smoking cessation could save patients >$4,000 a year. It is crucial to make smoking cessation a priority at every appointment, and to offer patients hope and practical guidance through repeated attempts to quit.

Offer varenicline. For patients with schizophrenia, cessation counseling or behavioral interventions alone have a poor efficacy rate of approximately 5% (compared with 15% to 20% in the general population).2 Varenicline is the most effective smoking cessation treatment; it increases cessation rates 5-fold among patients with schizophrenia.3 As demonstrated by the Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES),4 varenicline does not lead to an increased risk of suicidality or serious neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

When starting a patient on varenicline, set a quit date 4 weeks from medication initiation. Individuals with schizophrenia often have a greater smoking burden and experience more intense symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. A 4-week period between medication initiation and the quit date will allow these patients to gradually experience reduced cravings and separate minor adverse effects of the medication from those of nicotine withdrawal. Concurrent prescription of nicotine replacement therapy (eg, patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler) also is safe and can assist in quit attempts.

Consider varenicline maintenance therapy. After a successful quit attempt, increase the likelihood of sustained cessation by continuing varenicline beyond 12 weeks. Varenicline can be used as a maintenance medication to prevent smoking relapse in patients with schizophrenia; when prescribed to these patients for an additional 3 months, it can reduce the relapse rate similarly to that seen in smokers in the general population.5

Adjust antipsychotic dosages. Tobacco smoke increases the activity of cytochrome P450 1A2, which metabolizes several antipsychotics. Thus, after successful smoking cessation, concentrations of clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, and olanzapine may increase, and dose reduction may be warranted. Conversely, if a patient resumes smoking, dosages of these medications may need to be increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Eden Evins, MD, MPH, and Corinne Cather, PhD, for their input on this article.

Tobacco-related cardiovascular disease is the primary reason adults with schizophrenia die on average 28 years earlier than their peers in the U.S. general population.1 To address this, clinicians need to prioritize smoking cessation and emphasize to patients with schizophrenia that quitting is the most important change they can make to improve their health. Here are 4 ways to help patients with schizophrenia quit smoking.

Provide hope, but be realistic. Most patients with schizophrenia who smoke want to quit; however, patients and clinicians alike have been discouraged by low quit rates and high relapse rates. Smoking often is viewed as one of the few remaining personal freedoms, as a lower priority than active psychiatric symptoms, or even as neuroprotective. By perpetuating these falsehoods and avoiding addressing smoking cessation, we are failing our patients.

With persistent engagement and use of effective pharmacotherapeutic interventions, smoking cessation is attainable and does not worsen psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, smoking cessation could save patients >$4,000 a year. It is crucial to make smoking cessation a priority at every appointment, and to offer patients hope and practical guidance through repeated attempts to quit.

Offer varenicline. For patients with schizophrenia, cessation counseling or behavioral interventions alone have a poor efficacy rate of approximately 5% (compared with 15% to 20% in the general population).2 Varenicline is the most effective smoking cessation treatment; it increases cessation rates 5-fold among patients with schizophrenia.3 As demonstrated by the Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES),4 varenicline does not lead to an increased risk of suicidality or serious neuropsychiatric adverse effects.

When starting a patient on varenicline, set a quit date 4 weeks from medication initiation. Individuals with schizophrenia often have a greater smoking burden and experience more intense symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. A 4-week period between medication initiation and the quit date will allow these patients to gradually experience reduced cravings and separate minor adverse effects of the medication from those of nicotine withdrawal. Concurrent prescription of nicotine replacement therapy (eg, patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler) also is safe and can assist in quit attempts.

Consider varenicline maintenance therapy. After a successful quit attempt, increase the likelihood of sustained cessation by continuing varenicline beyond 12 weeks. Varenicline can be used as a maintenance medication to prevent smoking relapse in patients with schizophrenia; when prescribed to these patients for an additional 3 months, it can reduce the relapse rate similarly to that seen in smokers in the general population.5

Adjust antipsychotic dosages. Tobacco smoke increases the activity of cytochrome P450 1A2, which metabolizes several antipsychotics. Thus, after successful smoking cessation, concentrations of clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, and olanzapine may increase, and dose reduction may be warranted. Conversely, if a patient resumes smoking, dosages of these medications may need to be increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Eden Evins, MD, MPH, and Corinne Cather, PhD, for their input on this article.

1. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

2. Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2(2):CD007253.

3. Evins AE, Benowitz N, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion vs. nicotine patch and placebo in the psychiatric cohort of the EAGLES trial. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 22nd Annual Meeting; March 2-5, 2016; Chicago, IL.

4. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

5. Evins AE, Hoeppner SS, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Maintenance pharmacotherapy normalizes the relapse curve in recently abstinent tobacco smokers with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:124-129.

1. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

2. Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2(2):CD007253.

3. Evins AE, Benowitz N, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion vs. nicotine patch and placebo in the psychiatric cohort of the EAGLES trial. Paper presented at: Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 22nd Annual Meeting; March 2-5, 2016; Chicago, IL.

4. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

5. Evins AE, Hoeppner SS, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Maintenance pharmacotherapy normalizes the relapse curve in recently abstinent tobacco smokers with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:124-129.

Decreasing suicide risk with math

Suicide is a common reality, accounting for approximately 800,000 deaths per year worldwide.1 Properly assessing and minimizing suicide risk can be challenging. We are taught that lithium and clozapine can decrease suicidality, and many psychiatrists prescribe these medications with the firm, “evidence-based” belief that doing so reduces suicide risk. Paradoxically, what they in fact might be doing is the exact opposite; they may be giving high-risk patients the opportunity and the means to attempt suicide with a lethal amount of medication.

One patient diagnosed with a mood disorder who attempted suicide had a surprising point of view. After taking a large qu

Operations research is a subfield of mathematics that tries to optimize one or more variables when multiple variables are in play. One example would be to maximize profit while minimizing cost. During World War II, operations research was used to decrease the number of munitions used to shoot down airplanes, and to sink submarines more efficiently.

Focusing on the patient who attempted suicide by overdose, the question was: If she was discharged from the psychiatry unit with a 30-day supply of medication, how lethal would that prescription be if deliberately taken all at once? And what can be done to minimize this suicide risk? Psychiatrists know that some medications are more dangerous than others, but few have performed quantitative analysis to determine the potential lethality of these medications. The math analysis did not involve multivariable calculus or differential equations, only multiplication and division. The results were eye-opening.

Calculating relative lethality

The lethal dose 50 (LD50) is the dose of a medication expressed in mg/kg that results in the death of 50% of the animals (usually rats) used in a controlled experiment. Open-source data for the LD50 of medications is provided by the manufacturers.

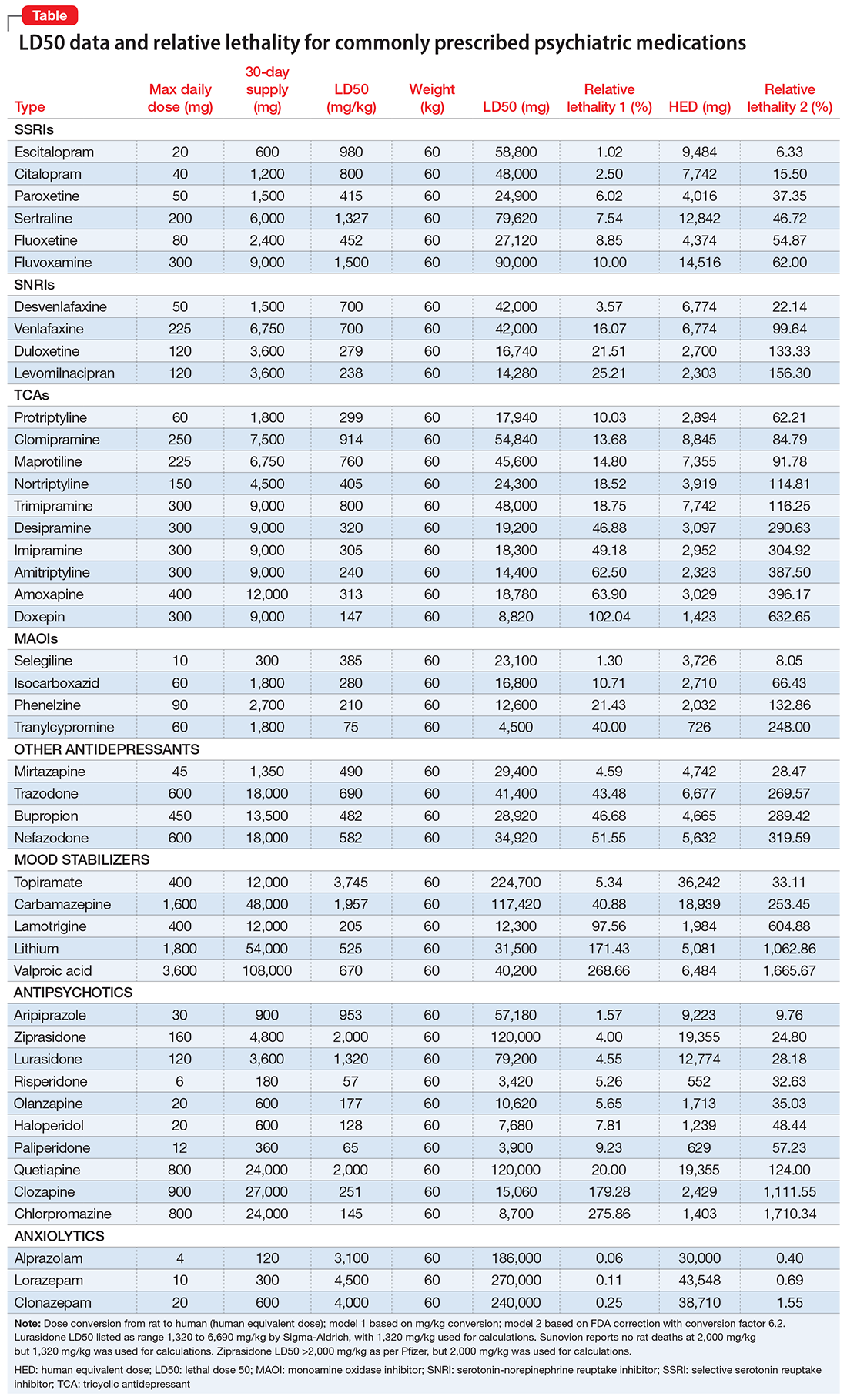

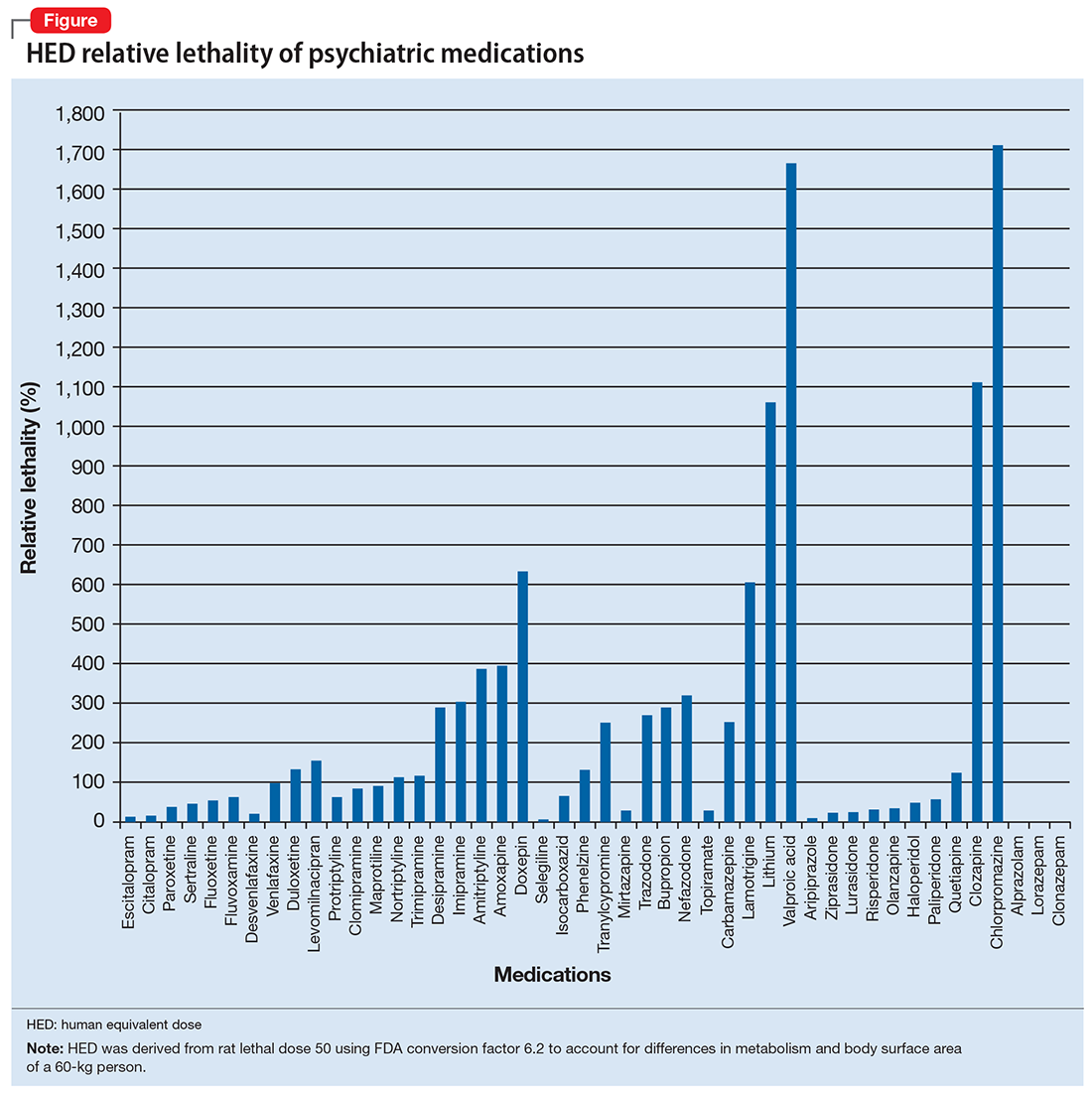

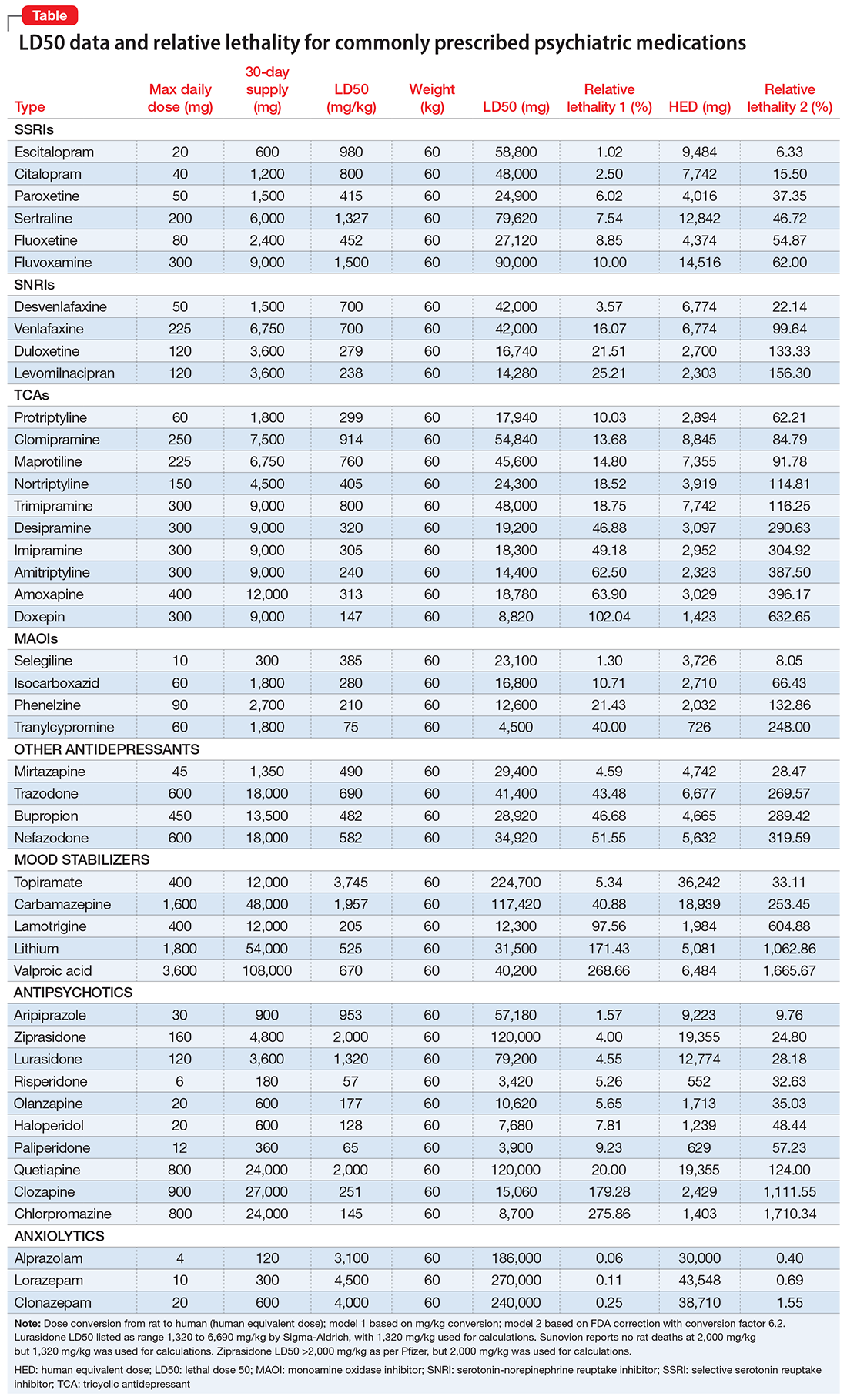

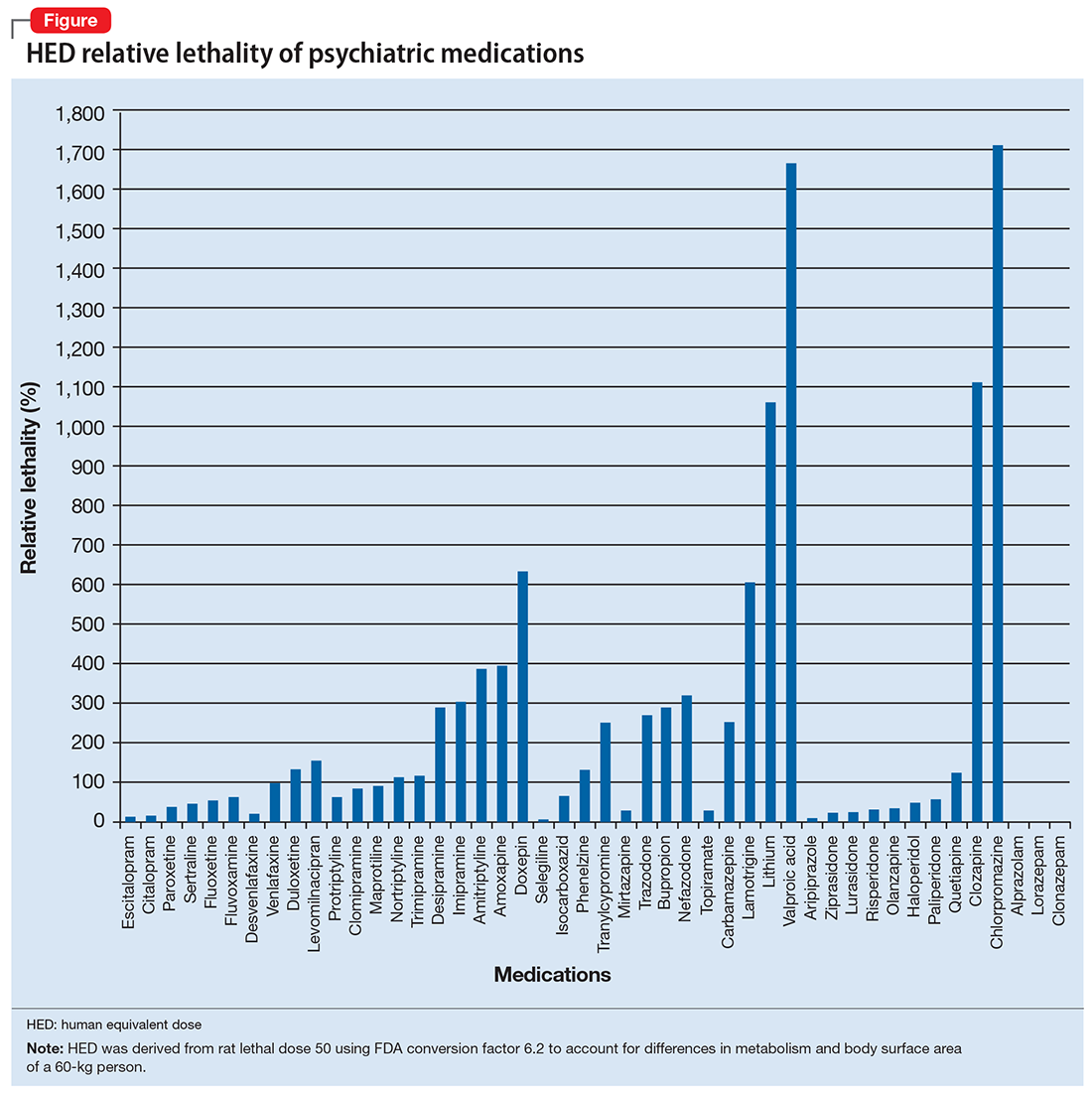

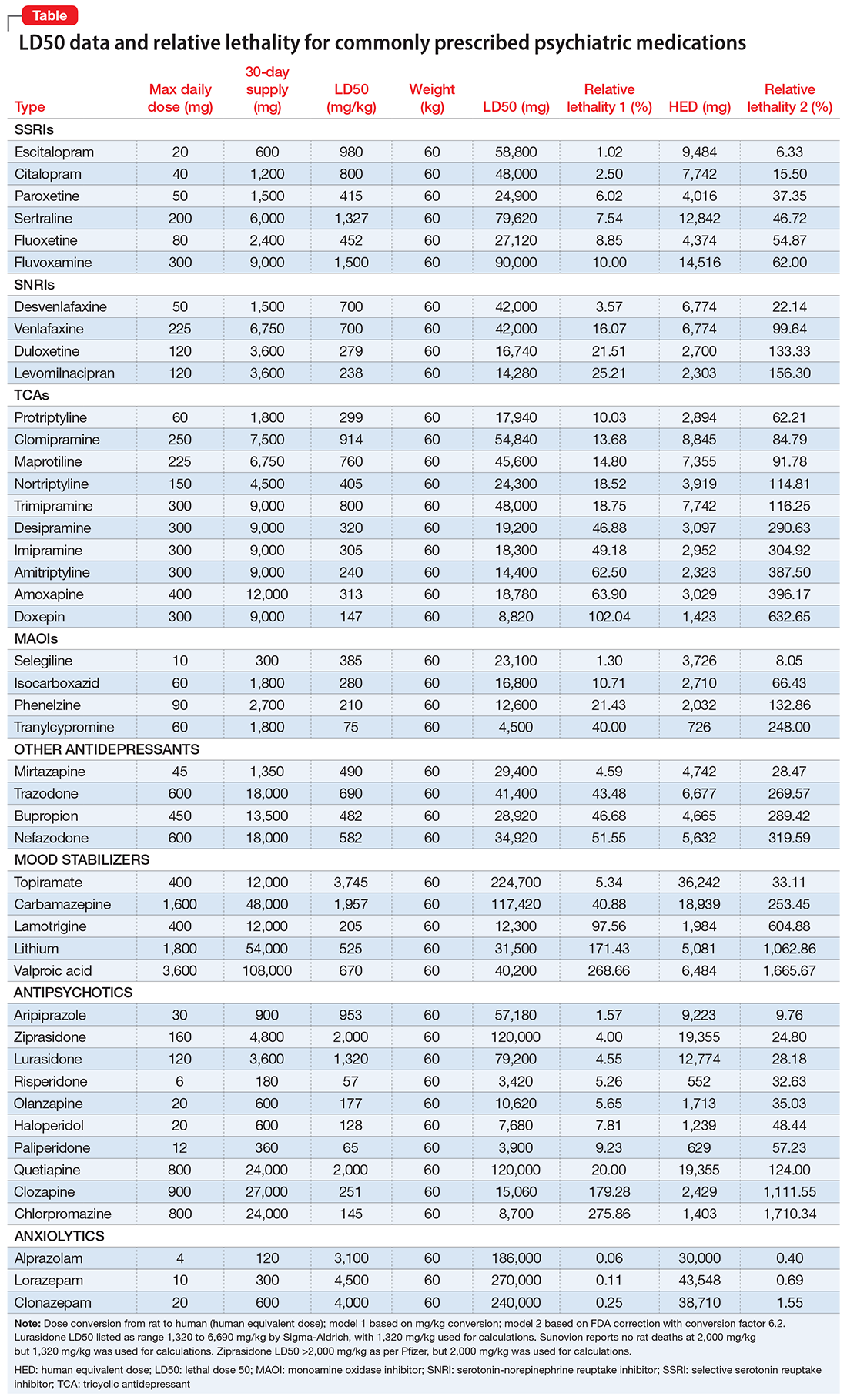

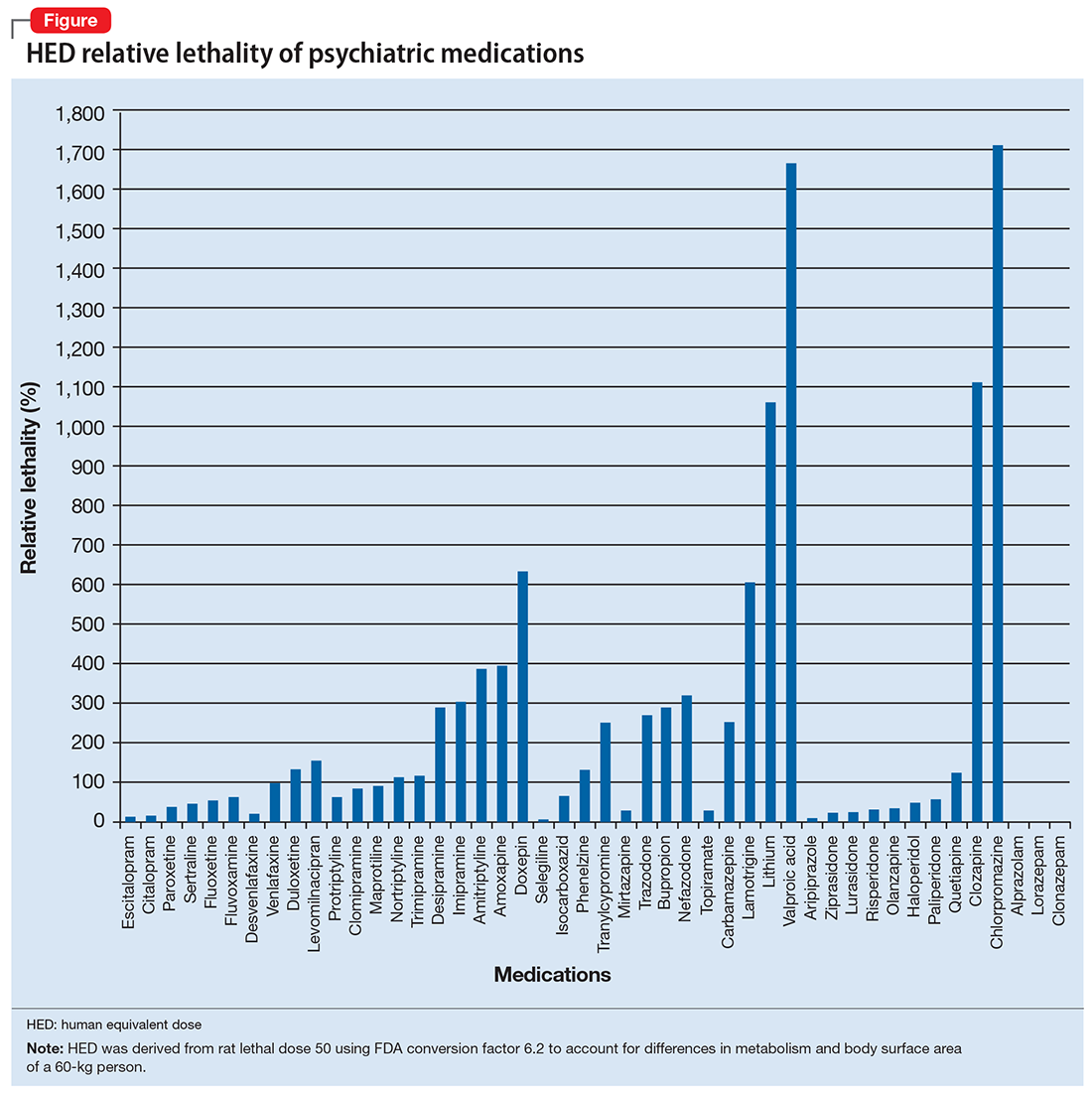

I tabulated this data for a wide range of psychiatric medications, including antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, in a spreadsheet with columns for maximum daily dose, 30-day supply of the medication, LD50 in mg/kg, LD50 for a 60-kg subject, and percentage of the 30-day supply compared with LD50. I then sorted this data by relative lethality (for my complete data, see Figure 1 and the Table).

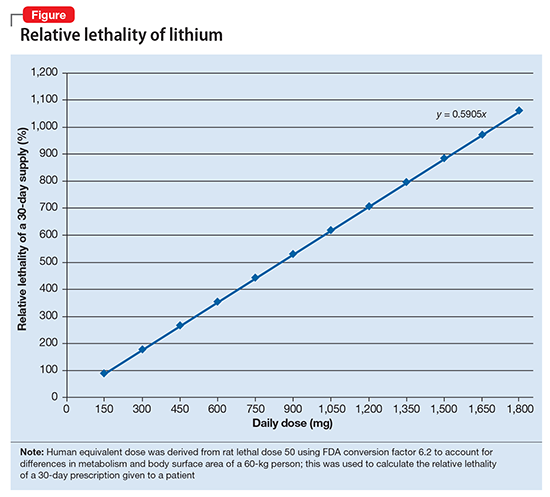

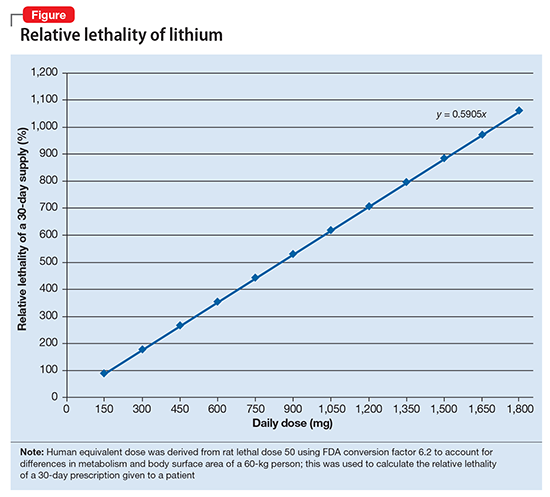

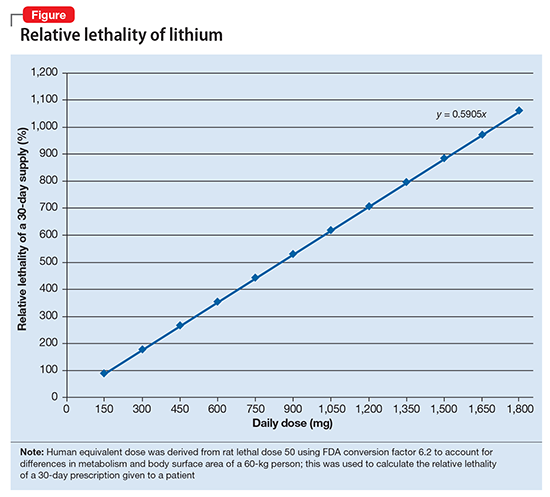

The rat dose in mg/kg was extrapolated to the human equivalent dose (HED) in mg/kg using a conversion factor of 6.2 (for a person who weighs 60 kg, the HED = LD50/6.2) as suggested by the FDA.2 The dose for the first fatality is smaller than the HED, and toxicity occurs at even smaller doses. After simplifying all the terms, the formula for the HED-relative lethality is f(x) = 310x/LD50, where x is the daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days. This is the equation of a straight line with a slope inversely proportional to the LD50 of each medication and a y-axis intercept of 0. Each medication line shows that any dose rising above 100% on the y-axis is a quantum higher than the lethal dose.

Some commonly prescribed psychotropics are highly lethal

The relative lethality of many commonly prescribed psychiatric medications, including those frequently used to reduce suicidality, varies tremendously. For example, it is widely known that the first-line mood stabilizer lithium has a narrow therapeutic window and can rapidly become toxic. If a patient becomes dehydrated, even a normal lithium dose can be toxic or lethal. Lithium has a relative lethality of 1,063% (Figure 2). Clozapine has a relative lethality of 1,112%. Valproic acid has an even higher relative lethality of 1,666%. By contrast, aripiprazole and olanzapine have a relative lethality of 10% and 35%, respectively. For preventing suicide, prescribing a second-generation antipsychotic with a lower relative lethality may be preferable over prescribing a medication with a higher relative lethality.

According to U.S. poison control centers,3 from 2000 to 2014, there were 15,036 serious outcomes, including 61 deaths, associated with lithium use, and 6,109 serious outcomes, including 37 deaths, associated with valproic acid. In contrast, there were only 1,446 serious outcomes and no deaths associated with aripiprazole use.3 These outcomes may be underreported, but they are consistent with the mathematical model predicting that medications with a higher relative lethality will have higher morbidity and mortality outcomes, regardless of a patient’s intent to overdose.

Many psychiatrists have a preferred antidepressant, mood stabilizer, or antipsychotic, and may prescribe this medication to many of their patients based on familiarity with the agent or other factors. However, simple math can give the decision process of selecting a specific medication for a given patient a more quantitative basis.

Even a small reduction in suicide would save many lives

Ultimately, the math problem comes down to 4 minutes, which is approximately how long the brain can survive without oxygen. By prescribing medications with a lower relative lethality, or by prescribing a less-than-30-day supply of the most lethal medications, it may be possible to decrease overdose morbidity and mortality, and also buy enough time for emergency personnel to save a life. If simple math can put even a 1% dent in the rate of death from suicide, approximately 8,000 lives might be saved every year.

1. World Health Organization. Suicide. Fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en. Updated August 2017. Accessed January 3, 2018.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Estimating the maximum safe starting dose in initial clinical trials for therapeutics in adult healthy volunteers. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm078932.pdf. Published July 6, 2005. Accessed January 8, 2018.

3. Nelson JC, Spyker DA. Morbidity and mortality associated with medications used in the treatment of depression: an analysis of cases reported to U.S. Poison Control Centers, 2000-2014. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):438-450.

Suicide is a common reality, accounting for approximately 800,000 deaths per year worldwide.1 Properly assessing and minimizing suicide risk can be challenging. We are taught that lithium and clozapine can decrease suicidality, and many psychiatrists prescribe these medications with the firm, “evidence-based” belief that doing so reduces suicide risk. Paradoxically, what they in fact might be doing is the exact opposite; they may be giving high-risk patients the opportunity and the means to attempt suicide with a lethal amount of medication.

One patient diagnosed with a mood disorder who attempted suicide had a surprising point of view. After taking a large qu