User login

Clinical Care Pathway for Cellulitis Can Help Reduce Antibiotic Use, Cost

Clinical question: How would an evidence-based clinical pathway for cellulitis affect process metrics, patient outcomes, and clinical cost?

Background: Cellulitis is a common hospital problem, but its evaluation and treatment vary widely. Specifically, broad-spectrum antibiotics and imaging studies are overutilized when compared to recommended guidelines. A standardized clinical pathway is proposed as a possible solution.

Study design: Retrospective, observational, pre-/post-intervention study.

Setting: University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team created a guideline-based care pathway for cellulitis and enrolled 677 adult patients for retrospective analysis during a two-year period. The study showed an overall 59% decrease in the odds of ordering broad-spectrum antibiotics, 23% decrease in pharmacy cost, 44% decrease in laboratory cost, and 13% decrease in overall facility cost, pre-/post-intervention. It also demonstrated no adverse effect on length of stay or 30-day readmission rates.

Given the retrospective, single-center nature of this study, as well as some baseline characteristic differences between enrolled patients, careful conclusions regarding external validity on diverse patient populations must be considered; however, the history of clinical care pathways supports many of the study’s findings. The results make a compelling case for hospitalist groups to implement similar cellulitis pathways and research their effectiveness.

Bottom line: Clinical care pathways for cellulitis provide an opportunity to improve antibiotic stewardship and lower hospital costs without compromising quality of care.

Citation: Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Spivak ES, Hopkins C, Kawamoto K. Evidence-based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2433.

Clinical question: How would an evidence-based clinical pathway for cellulitis affect process metrics, patient outcomes, and clinical cost?

Background: Cellulitis is a common hospital problem, but its evaluation and treatment vary widely. Specifically, broad-spectrum antibiotics and imaging studies are overutilized when compared to recommended guidelines. A standardized clinical pathway is proposed as a possible solution.

Study design: Retrospective, observational, pre-/post-intervention study.

Setting: University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team created a guideline-based care pathway for cellulitis and enrolled 677 adult patients for retrospective analysis during a two-year period. The study showed an overall 59% decrease in the odds of ordering broad-spectrum antibiotics, 23% decrease in pharmacy cost, 44% decrease in laboratory cost, and 13% decrease in overall facility cost, pre-/post-intervention. It also demonstrated no adverse effect on length of stay or 30-day readmission rates.

Given the retrospective, single-center nature of this study, as well as some baseline characteristic differences between enrolled patients, careful conclusions regarding external validity on diverse patient populations must be considered; however, the history of clinical care pathways supports many of the study’s findings. The results make a compelling case for hospitalist groups to implement similar cellulitis pathways and research their effectiveness.

Bottom line: Clinical care pathways for cellulitis provide an opportunity to improve antibiotic stewardship and lower hospital costs without compromising quality of care.

Citation: Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Spivak ES, Hopkins C, Kawamoto K. Evidence-based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2433.

Clinical question: How would an evidence-based clinical pathway for cellulitis affect process metrics, patient outcomes, and clinical cost?

Background: Cellulitis is a common hospital problem, but its evaluation and treatment vary widely. Specifically, broad-spectrum antibiotics and imaging studies are overutilized when compared to recommended guidelines. A standardized clinical pathway is proposed as a possible solution.

Study design: Retrospective, observational, pre-/post-intervention study.

Setting: University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team created a guideline-based care pathway for cellulitis and enrolled 677 adult patients for retrospective analysis during a two-year period. The study showed an overall 59% decrease in the odds of ordering broad-spectrum antibiotics, 23% decrease in pharmacy cost, 44% decrease in laboratory cost, and 13% decrease in overall facility cost, pre-/post-intervention. It also demonstrated no adverse effect on length of stay or 30-day readmission rates.

Given the retrospective, single-center nature of this study, as well as some baseline characteristic differences between enrolled patients, careful conclusions regarding external validity on diverse patient populations must be considered; however, the history of clinical care pathways supports many of the study’s findings. The results make a compelling case for hospitalist groups to implement similar cellulitis pathways and research their effectiveness.

Bottom line: Clinical care pathways for cellulitis provide an opportunity to improve antibiotic stewardship and lower hospital costs without compromising quality of care.

Citation: Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Spivak ES, Hopkins C, Kawamoto K. Evidence-based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2433.

Antimicrobial Stewardship Resources Often Lacking in Hospitalists' Routines

The best antibiotic stewardship programs weave improvements into the routines of hospitalists. But at the end of the day, developing and overseeing these important programs does require some level of time and money. And setting aside that time and money has been the exception rather than the rule.

According to early results from an SHM survey, nine of 123 hospitalists said that they are compensated for work on antimicrobial stewardship programs at their hospitals. That’s a mere 7%. Only 10 out of 122 respondents said they have “protected time” for work on an antimicrobial stewardship program. That’s about 8%. And it’s possible that the survey results are actually skewed somewhat, receiving responses from more proactive centers. One hundred fifteen out of 178 respondents, or 65%, said that they have an antimicrobial stewardship program at their centers.

Arjun Srinivasan, the CDC’s associate director for healthcare-associated infection prevention programs, says he has found that typically about half of U.S. hospitals have such programs. Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, director of the collaborative inpatient medicine service at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, says change can be a slow process, but he expects initiatives like SHM’s new antibiotic stewardship campaign to help tip the scales toward more resources and more change. It’s a matter of “making the case that, No. 1, this is a problem and, No. 2, there are solutions out there and, No. 3, these solutions are cost effective, as well as improving quality.” Demonstrating the effects on cost and outcomes, he says, is “likely the tipping point [where] we will see real change.”

“If we don’t change, we’re going to run out of antibiotics,” says Dr. Howell, who is also senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. “People are sort of really panic-stricken. And that fear is helping to motivate them to drive change, too.”

Jonathan Zenilman, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Bayview, says that his team worked with a non-Hopkins hospital in Delaware and found they saved about $80,000 a year just by eliminating the use of ertapenem for pre-operative prophylaxis for abdominal surgery. Numbers like that, he says, show that the case for savings can be made to hospital administration. Then again, it’s often easier to make the case before a program is started—and harder to keep it going after that first year.

“Between the second and the third year, you’re not going to generate much savings, if anything,” he says. If a new administrator is in place, it can be a challenge to get them to realize that costs will go back up once a program is dismantled.

“They look at this as an additional business model,” Dr. Zenilman explains. “They’ll say, ‘Where does my revenue offset the costs?’ And sometimes they just don’t get the value proposition…It needs to be pitched as a value proposition and not as a revenue proposition.”

The culture change toward value in the U.S. is helping, though, he says. “Now the business case is easier,” he says, “because there’s clearly this regulatory push towards doing it.” TH

The best antibiotic stewardship programs weave improvements into the routines of hospitalists. But at the end of the day, developing and overseeing these important programs does require some level of time and money. And setting aside that time and money has been the exception rather than the rule.

According to early results from an SHM survey, nine of 123 hospitalists said that they are compensated for work on antimicrobial stewardship programs at their hospitals. That’s a mere 7%. Only 10 out of 122 respondents said they have “protected time” for work on an antimicrobial stewardship program. That’s about 8%. And it’s possible that the survey results are actually skewed somewhat, receiving responses from more proactive centers. One hundred fifteen out of 178 respondents, or 65%, said that they have an antimicrobial stewardship program at their centers.

Arjun Srinivasan, the CDC’s associate director for healthcare-associated infection prevention programs, says he has found that typically about half of U.S. hospitals have such programs. Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, director of the collaborative inpatient medicine service at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, says change can be a slow process, but he expects initiatives like SHM’s new antibiotic stewardship campaign to help tip the scales toward more resources and more change. It’s a matter of “making the case that, No. 1, this is a problem and, No. 2, there are solutions out there and, No. 3, these solutions are cost effective, as well as improving quality.” Demonstrating the effects on cost and outcomes, he says, is “likely the tipping point [where] we will see real change.”

“If we don’t change, we’re going to run out of antibiotics,” says Dr. Howell, who is also senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. “People are sort of really panic-stricken. And that fear is helping to motivate them to drive change, too.”

Jonathan Zenilman, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Bayview, says that his team worked with a non-Hopkins hospital in Delaware and found they saved about $80,000 a year just by eliminating the use of ertapenem for pre-operative prophylaxis for abdominal surgery. Numbers like that, he says, show that the case for savings can be made to hospital administration. Then again, it’s often easier to make the case before a program is started—and harder to keep it going after that first year.

“Between the second and the third year, you’re not going to generate much savings, if anything,” he says. If a new administrator is in place, it can be a challenge to get them to realize that costs will go back up once a program is dismantled.

“They look at this as an additional business model,” Dr. Zenilman explains. “They’ll say, ‘Where does my revenue offset the costs?’ And sometimes they just don’t get the value proposition…It needs to be pitched as a value proposition and not as a revenue proposition.”

The culture change toward value in the U.S. is helping, though, he says. “Now the business case is easier,” he says, “because there’s clearly this regulatory push towards doing it.” TH

The best antibiotic stewardship programs weave improvements into the routines of hospitalists. But at the end of the day, developing and overseeing these important programs does require some level of time and money. And setting aside that time and money has been the exception rather than the rule.

According to early results from an SHM survey, nine of 123 hospitalists said that they are compensated for work on antimicrobial stewardship programs at their hospitals. That’s a mere 7%. Only 10 out of 122 respondents said they have “protected time” for work on an antimicrobial stewardship program. That’s about 8%. And it’s possible that the survey results are actually skewed somewhat, receiving responses from more proactive centers. One hundred fifteen out of 178 respondents, or 65%, said that they have an antimicrobial stewardship program at their centers.

Arjun Srinivasan, the CDC’s associate director for healthcare-associated infection prevention programs, says he has found that typically about half of U.S. hospitals have such programs. Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, director of the collaborative inpatient medicine service at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, says change can be a slow process, but he expects initiatives like SHM’s new antibiotic stewardship campaign to help tip the scales toward more resources and more change. It’s a matter of “making the case that, No. 1, this is a problem and, No. 2, there are solutions out there and, No. 3, these solutions are cost effective, as well as improving quality.” Demonstrating the effects on cost and outcomes, he says, is “likely the tipping point [where] we will see real change.”

“If we don’t change, we’re going to run out of antibiotics,” says Dr. Howell, who is also senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. “People are sort of really panic-stricken. And that fear is helping to motivate them to drive change, too.”

Jonathan Zenilman, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Bayview, says that his team worked with a non-Hopkins hospital in Delaware and found they saved about $80,000 a year just by eliminating the use of ertapenem for pre-operative prophylaxis for abdominal surgery. Numbers like that, he says, show that the case for savings can be made to hospital administration. Then again, it’s often easier to make the case before a program is started—and harder to keep it going after that first year.

“Between the second and the third year, you’re not going to generate much savings, if anything,” he says. If a new administrator is in place, it can be a challenge to get them to realize that costs will go back up once a program is dismantled.

“They look at this as an additional business model,” Dr. Zenilman explains. “They’ll say, ‘Where does my revenue offset the costs?’ And sometimes they just don’t get the value proposition…It needs to be pitched as a value proposition and not as a revenue proposition.”

The culture change toward value in the U.S. is helping, though, he says. “Now the business case is easier,” he says, “because there’s clearly this regulatory push towards doing it.” TH

Chemotherapy Does Not Improve Quality of Life with End-Stage Cancer

Clinical question: Does palliative chemotherapy improve quality of life (QOL) in patients with end-stage cancer, regardless of performance status?

Background: There is continued debate about the benefit of palliative chemotherapy at the end of life. Guidelines recommend a good performance score as an indicator of appropriate use of therapy; however, little is known about the benefits and harms of chemotherapy in metastatic cancer patients stratified by performance status.

Study design: Longitudinal, prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-institutional in the United States.

Synopsis: Five U.S. institutions enrolled 661 patients with metastatic cancer and estimated life expectancy less than six months; 312 patients who died during the study period were included in the final analysis of postmortem questionnaires of caretakers regarding QOL in the patients’ last week of life. Contrary to current thought, the study demonstrated that patients undergoing end-of-life palliative chemotherapy with good ECOG performance status (0-1) had significantly worse QOL than those avoiding palliative chemotherapy. There was no difference in QOL in patients with worse performance status (ECOG 2-3).

This study is one of the first prospective investigations of this topic and makes a compelling case for withholding palliative chemotherapy at the end of life regardless of performance status. The study is somewhat limited in that the QOL measurement is only for the last week of life and the patients were not randomized into the chemotherapy arm, which could bias results.

Bottom line: Palliative chemotherapy does not improve QOL near death, and may actually worsen QOL in patients with good performance status.

Citation: Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):778-784.

Clinical question: Does palliative chemotherapy improve quality of life (QOL) in patients with end-stage cancer, regardless of performance status?

Background: There is continued debate about the benefit of palliative chemotherapy at the end of life. Guidelines recommend a good performance score as an indicator of appropriate use of therapy; however, little is known about the benefits and harms of chemotherapy in metastatic cancer patients stratified by performance status.

Study design: Longitudinal, prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-institutional in the United States.

Synopsis: Five U.S. institutions enrolled 661 patients with metastatic cancer and estimated life expectancy less than six months; 312 patients who died during the study period were included in the final analysis of postmortem questionnaires of caretakers regarding QOL in the patients’ last week of life. Contrary to current thought, the study demonstrated that patients undergoing end-of-life palliative chemotherapy with good ECOG performance status (0-1) had significantly worse QOL than those avoiding palliative chemotherapy. There was no difference in QOL in patients with worse performance status (ECOG 2-3).

This study is one of the first prospective investigations of this topic and makes a compelling case for withholding palliative chemotherapy at the end of life regardless of performance status. The study is somewhat limited in that the QOL measurement is only for the last week of life and the patients were not randomized into the chemotherapy arm, which could bias results.

Bottom line: Palliative chemotherapy does not improve QOL near death, and may actually worsen QOL in patients with good performance status.

Citation: Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):778-784.

Clinical question: Does palliative chemotherapy improve quality of life (QOL) in patients with end-stage cancer, regardless of performance status?

Background: There is continued debate about the benefit of palliative chemotherapy at the end of life. Guidelines recommend a good performance score as an indicator of appropriate use of therapy; however, little is known about the benefits and harms of chemotherapy in metastatic cancer patients stratified by performance status.

Study design: Longitudinal, prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-institutional in the United States.

Synopsis: Five U.S. institutions enrolled 661 patients with metastatic cancer and estimated life expectancy less than six months; 312 patients who died during the study period were included in the final analysis of postmortem questionnaires of caretakers regarding QOL in the patients’ last week of life. Contrary to current thought, the study demonstrated that patients undergoing end-of-life palliative chemotherapy with good ECOG performance status (0-1) had significantly worse QOL than those avoiding palliative chemotherapy. There was no difference in QOL in patients with worse performance status (ECOG 2-3).

This study is one of the first prospective investigations of this topic and makes a compelling case for withholding palliative chemotherapy at the end of life regardless of performance status. The study is somewhat limited in that the QOL measurement is only for the last week of life and the patients were not randomized into the chemotherapy arm, which could bias results.

Bottom line: Palliative chemotherapy does not improve QOL near death, and may actually worsen QOL in patients with good performance status.

Citation: Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):778-784.

Post-Operative Transfusions after Noncardiac Surgery Associated with Increased Adverse Outcomes

Clinical question: Do transfusions affect post-operative outcomes after noncardiac surgery?

Background: Studies have demonstrated that a restrictive transfusion strategy is probably superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in many clinical settings. Despite this data, there continues to be wide variation in the use of blood transfusions in the peri-operative setting.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-two community and academic hospitals in Michigan.

Synopsis: Demographic, operative, and outcomes data were extracted from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and reviewed for 48,720 patients who underwent noncardiac surgery between 2012-2014. A total of 4.6% of patients received a blood transfusion within 72 hours after surgery. The patients who received blood products were at increased risk for death at 30 days (3.6% excess absolute risk), for infectious complications (1% excess absolute risk), and for having at least one post-operative noninfectious complication (4.4% increased absolute risk).

Bottom line: Although observational in nature, this study adds to the increasing body of evidence supporting an increase in surgical morbidity and mortality associated with blood transfusions.

Citation: Abdelsattar ZM, Hendren S, Wong SL, Campbell DA Jr, Henke P. Variation in transfusion practices and the effect on outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;262(1):1-6.

Clinical question: Do transfusions affect post-operative outcomes after noncardiac surgery?

Background: Studies have demonstrated that a restrictive transfusion strategy is probably superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in many clinical settings. Despite this data, there continues to be wide variation in the use of blood transfusions in the peri-operative setting.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-two community and academic hospitals in Michigan.

Synopsis: Demographic, operative, and outcomes data were extracted from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and reviewed for 48,720 patients who underwent noncardiac surgery between 2012-2014. A total of 4.6% of patients received a blood transfusion within 72 hours after surgery. The patients who received blood products were at increased risk for death at 30 days (3.6% excess absolute risk), for infectious complications (1% excess absolute risk), and for having at least one post-operative noninfectious complication (4.4% increased absolute risk).

Bottom line: Although observational in nature, this study adds to the increasing body of evidence supporting an increase in surgical morbidity and mortality associated with blood transfusions.

Citation: Abdelsattar ZM, Hendren S, Wong SL, Campbell DA Jr, Henke P. Variation in transfusion practices and the effect on outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;262(1):1-6.

Clinical question: Do transfusions affect post-operative outcomes after noncardiac surgery?

Background: Studies have demonstrated that a restrictive transfusion strategy is probably superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in many clinical settings. Despite this data, there continues to be wide variation in the use of blood transfusions in the peri-operative setting.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-two community and academic hospitals in Michigan.

Synopsis: Demographic, operative, and outcomes data were extracted from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and reviewed for 48,720 patients who underwent noncardiac surgery between 2012-2014. A total of 4.6% of patients received a blood transfusion within 72 hours after surgery. The patients who received blood products were at increased risk for death at 30 days (3.6% excess absolute risk), for infectious complications (1% excess absolute risk), and for having at least one post-operative noninfectious complication (4.4% increased absolute risk).

Bottom line: Although observational in nature, this study adds to the increasing body of evidence supporting an increase in surgical morbidity and mortality associated with blood transfusions.

Citation: Abdelsattar ZM, Hendren S, Wong SL, Campbell DA Jr, Henke P. Variation in transfusion practices and the effect on outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;262(1):1-6.

Left Atrial Appendage Closure Favorable Over Warfarin for Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical question: Is there a favorable risk-benefit ratio for left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) compared to warfarin for prevention of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?

Background: LAAC with the WATCHMAN device was shown to be noninferior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in two trials: PROTECT AF and PREVAIL. Further efficacy concerns were raised following routine regulatory filings, leading to the need for continued evaluation.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Patient-level data were combined and analyzed from the PROTECT AF and PREVAIL trails and two nonrandomized registries of LAAC with the WATCHMAN device: the Continued Access PROTECT AF registry (CAP) and the Continued Access to PREVAIL registry (CAP2).

Synopsis: A total of 2,406 patients were enrolled from all four data sets from 2005-2014. Of those, 1,877 were treated with the WATCHMAN device and 382 were treated with warfarin. Annualized risk of stroke if untreated with anticoagulation for all patients was 5.7% to 7.6%, indicating that all were eligible to be treated with warfarin. Ninety percent of patients had moderate to high risk of bleeding. Analysis showed that LAAC was noninferior to warfarin for stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death.

A slight increase in ischemic stroke in the LAAC group was counterbalanced by the significant reduction in hemorrhagic stroke in the LAAC group versus the warfarin group. Cardiovascular deaths were significantly fewer in the LAAC cohort; all-cause mortality favored LAAC but did not reach statistical significance. There was also a significant reduction in nonprocedure-related major bleeding in the LAAC group. Limitations of this study include the limited number of patients treated with warfarin and lack of comparison to new oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

Bottom line: Patients with increased stroke risk from nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with the WATCHMAN device for LAAC have significant reductions in hemorrhagic stroke, cardiovascular death, and nonprocedure-related major bleeding, but slightly increased risk of ischemic stroke compared to those treated with warfarin.

Citaiton: Holmes DR Jr, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. Left atrial appendage closure as an alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(24):2614-2623.

Clinical question: Is there a favorable risk-benefit ratio for left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) compared to warfarin for prevention of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?

Background: LAAC with the WATCHMAN device was shown to be noninferior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in two trials: PROTECT AF and PREVAIL. Further efficacy concerns were raised following routine regulatory filings, leading to the need for continued evaluation.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Patient-level data were combined and analyzed from the PROTECT AF and PREVAIL trails and two nonrandomized registries of LAAC with the WATCHMAN device: the Continued Access PROTECT AF registry (CAP) and the Continued Access to PREVAIL registry (CAP2).

Synopsis: A total of 2,406 patients were enrolled from all four data sets from 2005-2014. Of those, 1,877 were treated with the WATCHMAN device and 382 were treated with warfarin. Annualized risk of stroke if untreated with anticoagulation for all patients was 5.7% to 7.6%, indicating that all were eligible to be treated with warfarin. Ninety percent of patients had moderate to high risk of bleeding. Analysis showed that LAAC was noninferior to warfarin for stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death.

A slight increase in ischemic stroke in the LAAC group was counterbalanced by the significant reduction in hemorrhagic stroke in the LAAC group versus the warfarin group. Cardiovascular deaths were significantly fewer in the LAAC cohort; all-cause mortality favored LAAC but did not reach statistical significance. There was also a significant reduction in nonprocedure-related major bleeding in the LAAC group. Limitations of this study include the limited number of patients treated with warfarin and lack of comparison to new oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

Bottom line: Patients with increased stroke risk from nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with the WATCHMAN device for LAAC have significant reductions in hemorrhagic stroke, cardiovascular death, and nonprocedure-related major bleeding, but slightly increased risk of ischemic stroke compared to those treated with warfarin.

Citaiton: Holmes DR Jr, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. Left atrial appendage closure as an alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(24):2614-2623.

Clinical question: Is there a favorable risk-benefit ratio for left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) compared to warfarin for prevention of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?

Background: LAAC with the WATCHMAN device was shown to be noninferior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in two trials: PROTECT AF and PREVAIL. Further efficacy concerns were raised following routine regulatory filings, leading to the need for continued evaluation.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Patient-level data were combined and analyzed from the PROTECT AF and PREVAIL trails and two nonrandomized registries of LAAC with the WATCHMAN device: the Continued Access PROTECT AF registry (CAP) and the Continued Access to PREVAIL registry (CAP2).

Synopsis: A total of 2,406 patients were enrolled from all four data sets from 2005-2014. Of those, 1,877 were treated with the WATCHMAN device and 382 were treated with warfarin. Annualized risk of stroke if untreated with anticoagulation for all patients was 5.7% to 7.6%, indicating that all were eligible to be treated with warfarin. Ninety percent of patients had moderate to high risk of bleeding. Analysis showed that LAAC was noninferior to warfarin for stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death.

A slight increase in ischemic stroke in the LAAC group was counterbalanced by the significant reduction in hemorrhagic stroke in the LAAC group versus the warfarin group. Cardiovascular deaths were significantly fewer in the LAAC cohort; all-cause mortality favored LAAC but did not reach statistical significance. There was also a significant reduction in nonprocedure-related major bleeding in the LAAC group. Limitations of this study include the limited number of patients treated with warfarin and lack of comparison to new oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

Bottom line: Patients with increased stroke risk from nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with the WATCHMAN device for LAAC have significant reductions in hemorrhagic stroke, cardiovascular death, and nonprocedure-related major bleeding, but slightly increased risk of ischemic stroke compared to those treated with warfarin.

Citaiton: Holmes DR Jr, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. Left atrial appendage closure as an alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(24):2614-2623.

Pediatric Trigger Tool Helps Identify Inpatient Pediatric Harm

Clinical question: Can a trigger tool identify harms for hospitalized children?

Background: An estimated 400,000 people die annually in the United States as a result of hospital-associated harm. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services define harm as “unintended physical injury … by medical care that required additional monitoring, treatment, or hospitalization or that resulted in death.” Although harm is common, voluntary reporting of events has been shown to capture only 2%-8% of harm. Global Trigger Tools (GTT) are an alternative to voluntary reports. These tools use “triggers,” or clues, to help reviewers identify potential harms when reviewing the electronic heath record. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has created an adult-focused GTT; however, no pediatric-focused GTT exists.

Study design: Cross-sectional, retrospective chart review.

Setting: Children <22 years old discharged from six freestanding U.S. children’s hospitals in February 2012.

Synopsis: In a prior paper, the authors described how they used a modified Delphi technique to develop a pediatric GTT based upon the IHI GTT. Here they piloted this new pediatric-focused GTT through a retrospective chart review. One clinical nonphysician reviewer and one physician reviewer were selected from each site and received training on use of the pediatric GTT and the identification of harms. One hundred charts from each site were randomly selected for application of the GTT. The reviewers examined the charts for harms and then applied the GTT. When reviewers found a harm, they determined the likelihood that the harm was preventable.

Of the 600 records reviewed, 240 harms were found. The GTT identified 1,093 potential harms, leading to identification of 204 harms. The remaining 36 harms did not cause a trigger and were found by chart review. The positive predictive value of the aggregate GTT was 22%. There were 40 harms per 100 patients, and 24.3% of patients had one or more harm. Sixty-eight percent of harms were of the least severe type, and only one led to a patient death. The most common harms were intravenous catheter infiltration, respiratory distress, constipation, pain, and surgical complications.

Bottom line: The pediatric GTT appears to be a moderately sensitive indicator for inpatient pediatric harm. Inpatient pediatric harm occurs frequently, with about one in four pediatric inpatients suffering from harm. Serious harm appears uncommon.

Citation: Stockwell DC, Bisarya H, Classen DC, et al. A trigger tool to detect harm in pediatric inpatient settings. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):1036-1042.

Clinical question: Can a trigger tool identify harms for hospitalized children?

Background: An estimated 400,000 people die annually in the United States as a result of hospital-associated harm. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services define harm as “unintended physical injury … by medical care that required additional monitoring, treatment, or hospitalization or that resulted in death.” Although harm is common, voluntary reporting of events has been shown to capture only 2%-8% of harm. Global Trigger Tools (GTT) are an alternative to voluntary reports. These tools use “triggers,” or clues, to help reviewers identify potential harms when reviewing the electronic heath record. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has created an adult-focused GTT; however, no pediatric-focused GTT exists.

Study design: Cross-sectional, retrospective chart review.

Setting: Children <22 years old discharged from six freestanding U.S. children’s hospitals in February 2012.

Synopsis: In a prior paper, the authors described how they used a modified Delphi technique to develop a pediatric GTT based upon the IHI GTT. Here they piloted this new pediatric-focused GTT through a retrospective chart review. One clinical nonphysician reviewer and one physician reviewer were selected from each site and received training on use of the pediatric GTT and the identification of harms. One hundred charts from each site were randomly selected for application of the GTT. The reviewers examined the charts for harms and then applied the GTT. When reviewers found a harm, they determined the likelihood that the harm was preventable.

Of the 600 records reviewed, 240 harms were found. The GTT identified 1,093 potential harms, leading to identification of 204 harms. The remaining 36 harms did not cause a trigger and were found by chart review. The positive predictive value of the aggregate GTT was 22%. There were 40 harms per 100 patients, and 24.3% of patients had one or more harm. Sixty-eight percent of harms were of the least severe type, and only one led to a patient death. The most common harms were intravenous catheter infiltration, respiratory distress, constipation, pain, and surgical complications.

Bottom line: The pediatric GTT appears to be a moderately sensitive indicator for inpatient pediatric harm. Inpatient pediatric harm occurs frequently, with about one in four pediatric inpatients suffering from harm. Serious harm appears uncommon.

Citation: Stockwell DC, Bisarya H, Classen DC, et al. A trigger tool to detect harm in pediatric inpatient settings. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):1036-1042.

Clinical question: Can a trigger tool identify harms for hospitalized children?

Background: An estimated 400,000 people die annually in the United States as a result of hospital-associated harm. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services define harm as “unintended physical injury … by medical care that required additional monitoring, treatment, or hospitalization or that resulted in death.” Although harm is common, voluntary reporting of events has been shown to capture only 2%-8% of harm. Global Trigger Tools (GTT) are an alternative to voluntary reports. These tools use “triggers,” or clues, to help reviewers identify potential harms when reviewing the electronic heath record. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has created an adult-focused GTT; however, no pediatric-focused GTT exists.

Study design: Cross-sectional, retrospective chart review.

Setting: Children <22 years old discharged from six freestanding U.S. children’s hospitals in February 2012.

Synopsis: In a prior paper, the authors described how they used a modified Delphi technique to develop a pediatric GTT based upon the IHI GTT. Here they piloted this new pediatric-focused GTT through a retrospective chart review. One clinical nonphysician reviewer and one physician reviewer were selected from each site and received training on use of the pediatric GTT and the identification of harms. One hundred charts from each site were randomly selected for application of the GTT. The reviewers examined the charts for harms and then applied the GTT. When reviewers found a harm, they determined the likelihood that the harm was preventable.

Of the 600 records reviewed, 240 harms were found. The GTT identified 1,093 potential harms, leading to identification of 204 harms. The remaining 36 harms did not cause a trigger and were found by chart review. The positive predictive value of the aggregate GTT was 22%. There were 40 harms per 100 patients, and 24.3% of patients had one or more harm. Sixty-eight percent of harms were of the least severe type, and only one led to a patient death. The most common harms were intravenous catheter infiltration, respiratory distress, constipation, pain, and surgical complications.

Bottom line: The pediatric GTT appears to be a moderately sensitive indicator for inpatient pediatric harm. Inpatient pediatric harm occurs frequently, with about one in four pediatric inpatients suffering from harm. Serious harm appears uncommon.

Citation: Stockwell DC, Bisarya H, Classen DC, et al. A trigger tool to detect harm in pediatric inpatient settings. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):1036-1042.

Easing the Grieving Process for Families of Patients Dying in the ICU

Clinical question: Can we dignify death in the ICU and ease the grieving process by soliciting wishes from patients, families, and care team members?

Background: The death of the critically ill patient in the ICU can be dehumanizing and overwhelming for the patient’s family and friends, leading to prolonged physical and psychological stress. These deaths might have similar effects on the clinicians caring for the patients.

Study design: Mixed methods.

Setting: Medical-surgical ICU at a 21-bed, academic tertiary medical center in Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with at least one family member and three clinicians per patient. A total of 40 patients were screened and deemed eligible for inclusion. Only seven patients were able to provide input on the wishes or interviews; the others had impaired consciousness. The team obtained 163 wishes from those individuals, and was able to implement 159 of them (97.5%). At least three wishes from each patient-family dyad were implemented.

The wishes were classified into five categories:

- Humanizing the environment;

- Personal tributes;

- Family reconnections;

- Rituals and observances; and

- Paying it forward.

These wishes were implemented before (51.6%) and after (48.4%) death and were generally inexpensive (less than $200 per patient).

From the 160 interviews of 170 individuals, the central theme that emerged was personalization of the dying process in the ICU through three related domains: dignifying the patient, giving the family a voice, and fostering clinician compassion.

The 3 Wishes Project provides a framework to foster discussion among care team members and families to ensure personalization and dignity in the dying process.

Bottom line: Solicitation of wishes from dying patients, their families, and their care team members can have a positive impact by allowing individualized end-of-life care.

Citation: Cook D, Swinton M, Toledo F, et al. Personalizing death in the intensive care unit: the 3 Wishes Project: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):271-279.

Clinical question: Can we dignify death in the ICU and ease the grieving process by soliciting wishes from patients, families, and care team members?

Background: The death of the critically ill patient in the ICU can be dehumanizing and overwhelming for the patient’s family and friends, leading to prolonged physical and psychological stress. These deaths might have similar effects on the clinicians caring for the patients.

Study design: Mixed methods.

Setting: Medical-surgical ICU at a 21-bed, academic tertiary medical center in Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with at least one family member and three clinicians per patient. A total of 40 patients were screened and deemed eligible for inclusion. Only seven patients were able to provide input on the wishes or interviews; the others had impaired consciousness. The team obtained 163 wishes from those individuals, and was able to implement 159 of them (97.5%). At least three wishes from each patient-family dyad were implemented.

The wishes were classified into five categories:

- Humanizing the environment;

- Personal tributes;

- Family reconnections;

- Rituals and observances; and

- Paying it forward.

These wishes were implemented before (51.6%) and after (48.4%) death and were generally inexpensive (less than $200 per patient).

From the 160 interviews of 170 individuals, the central theme that emerged was personalization of the dying process in the ICU through three related domains: dignifying the patient, giving the family a voice, and fostering clinician compassion.

The 3 Wishes Project provides a framework to foster discussion among care team members and families to ensure personalization and dignity in the dying process.

Bottom line: Solicitation of wishes from dying patients, their families, and their care team members can have a positive impact by allowing individualized end-of-life care.

Citation: Cook D, Swinton M, Toledo F, et al. Personalizing death in the intensive care unit: the 3 Wishes Project: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):271-279.

Clinical question: Can we dignify death in the ICU and ease the grieving process by soliciting wishes from patients, families, and care team members?

Background: The death of the critically ill patient in the ICU can be dehumanizing and overwhelming for the patient’s family and friends, leading to prolonged physical and psychological stress. These deaths might have similar effects on the clinicians caring for the patients.

Study design: Mixed methods.

Setting: Medical-surgical ICU at a 21-bed, academic tertiary medical center in Ontario, Canada.

Synopsis: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with at least one family member and three clinicians per patient. A total of 40 patients were screened and deemed eligible for inclusion. Only seven patients were able to provide input on the wishes or interviews; the others had impaired consciousness. The team obtained 163 wishes from those individuals, and was able to implement 159 of them (97.5%). At least three wishes from each patient-family dyad were implemented.

The wishes were classified into five categories:

- Humanizing the environment;

- Personal tributes;

- Family reconnections;

- Rituals and observances; and

- Paying it forward.

These wishes were implemented before (51.6%) and after (48.4%) death and were generally inexpensive (less than $200 per patient).

From the 160 interviews of 170 individuals, the central theme that emerged was personalization of the dying process in the ICU through three related domains: dignifying the patient, giving the family a voice, and fostering clinician compassion.

The 3 Wishes Project provides a framework to foster discussion among care team members and families to ensure personalization and dignity in the dying process.

Bottom line: Solicitation of wishes from dying patients, their families, and their care team members can have a positive impact by allowing individualized end-of-life care.

Citation: Cook D, Swinton M, Toledo F, et al. Personalizing death in the intensive care unit: the 3 Wishes Project: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):271-279.

Thrombosis Management Demands Delicate, Balanced Approach

The delicate balance involved in providing hospitalized patients with needed anticoagulant, anti-platelet, and thrombolytic therapies for stroke and possible cardiac complications while minimizing bleed risks was explored by several speakers at the University of California San Francisco’s annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient Conference.

“These are dynamic issues and they’re moving all the time,” said Tracy Minichiello, MD, a former hospitalist who now runs the Anticoagulation and Thrombosis Service at the San Francisco VA Medical Center. Dosing and monitoring choices for physicians have grown more complicated with the new oral anticoagulants (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban), and she said another balancing act is emerging in hospitals trying to avoid unnecessary and wasteful treatments.

“There is interest on both sides of that question,” Dr. Minichiello said, adding the stakes are high. “We don’t want to miss the diagnosis of pulmonary embolisms, which can be difficult to catch. But now there’s more discussion of the other side of the issue—over-diagnosis and over-treatment—where we’re also trying to avoid, for example, overuse of CT scans.”

Another major thrust of Dr. Minichiello’s presentations involved bridging therapies, the application of a parenteral, short-acting anticoagulant therapy during the temporary interruption of warfarin anticoagulation for an invasive procedure. Bridging decreases stroke and embolism risk, but with an increased risk for bleeding.

“Full intensity bridging therapy for anticoagulation potentially can do more harm than good,” she said, noting a dearth of data to support mortality benefits of bridging therapy.

Literature increasingly recommends hospitalists be more selective about the use of bridging therapies that might have been employed reflexively in the past, she noted.

“[Hospitalists] must be mindful of the risks and benefits,” she said.

Physicians should also think twice about concomitant antiplatelet therapy like aspirin with anticoagulants. “We need to work collaboratively with our cardiology colleagues when a patient is on two or three of these therapies,” she said. “Recommendations in this area are in evolution.”

Elise Bouchard, MD, an internist at Centre Maria-Chapdelaine in Dolbeau-Mistassini, Quebec, attended Dr. Minichiello’s breakout session on challenging cases.

“I learned that we shouldn’t use aspirin with Coumadin or other anticoagulants, except for cases like acute coronary syndrome,” Dr. Bouchard said. She also explained a number of her patients with cancer, for example, need anticoagulation treatment and hate getting another injection, so she tries when possible to offer the oral anticoagulants.

Dr. Minichiello works with hospitalists at the San Francisco VA who seek consults around procedures, anticoagulant choices, and when to restart treatments.

“Most hospitalists don’t have access to a service like ours, although they might be able to call on a hematology consult service [or pharmacist],” she said. She suggested hospitalists trying to develop their own evidenced-based protocols use websites like the University of Washington’s anticoagulation service website, or the American Society of Health System Pharmacists’ anticoagulation resource center. TH

The delicate balance involved in providing hospitalized patients with needed anticoagulant, anti-platelet, and thrombolytic therapies for stroke and possible cardiac complications while minimizing bleed risks was explored by several speakers at the University of California San Francisco’s annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient Conference.

“These are dynamic issues and they’re moving all the time,” said Tracy Minichiello, MD, a former hospitalist who now runs the Anticoagulation and Thrombosis Service at the San Francisco VA Medical Center. Dosing and monitoring choices for physicians have grown more complicated with the new oral anticoagulants (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban), and she said another balancing act is emerging in hospitals trying to avoid unnecessary and wasteful treatments.

“There is interest on both sides of that question,” Dr. Minichiello said, adding the stakes are high. “We don’t want to miss the diagnosis of pulmonary embolisms, which can be difficult to catch. But now there’s more discussion of the other side of the issue—over-diagnosis and over-treatment—where we’re also trying to avoid, for example, overuse of CT scans.”

Another major thrust of Dr. Minichiello’s presentations involved bridging therapies, the application of a parenteral, short-acting anticoagulant therapy during the temporary interruption of warfarin anticoagulation for an invasive procedure. Bridging decreases stroke and embolism risk, but with an increased risk for bleeding.

“Full intensity bridging therapy for anticoagulation potentially can do more harm than good,” she said, noting a dearth of data to support mortality benefits of bridging therapy.

Literature increasingly recommends hospitalists be more selective about the use of bridging therapies that might have been employed reflexively in the past, she noted.

“[Hospitalists] must be mindful of the risks and benefits,” she said.

Physicians should also think twice about concomitant antiplatelet therapy like aspirin with anticoagulants. “We need to work collaboratively with our cardiology colleagues when a patient is on two or three of these therapies,” she said. “Recommendations in this area are in evolution.”

Elise Bouchard, MD, an internist at Centre Maria-Chapdelaine in Dolbeau-Mistassini, Quebec, attended Dr. Minichiello’s breakout session on challenging cases.

“I learned that we shouldn’t use aspirin with Coumadin or other anticoagulants, except for cases like acute coronary syndrome,” Dr. Bouchard said. She also explained a number of her patients with cancer, for example, need anticoagulation treatment and hate getting another injection, so she tries when possible to offer the oral anticoagulants.

Dr. Minichiello works with hospitalists at the San Francisco VA who seek consults around procedures, anticoagulant choices, and when to restart treatments.

“Most hospitalists don’t have access to a service like ours, although they might be able to call on a hematology consult service [or pharmacist],” she said. She suggested hospitalists trying to develop their own evidenced-based protocols use websites like the University of Washington’s anticoagulation service website, or the American Society of Health System Pharmacists’ anticoagulation resource center. TH

The delicate balance involved in providing hospitalized patients with needed anticoagulant, anti-platelet, and thrombolytic therapies for stroke and possible cardiac complications while minimizing bleed risks was explored by several speakers at the University of California San Francisco’s annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient Conference.

“These are dynamic issues and they’re moving all the time,” said Tracy Minichiello, MD, a former hospitalist who now runs the Anticoagulation and Thrombosis Service at the San Francisco VA Medical Center. Dosing and monitoring choices for physicians have grown more complicated with the new oral anticoagulants (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban), and she said another balancing act is emerging in hospitals trying to avoid unnecessary and wasteful treatments.

“There is interest on both sides of that question,” Dr. Minichiello said, adding the stakes are high. “We don’t want to miss the diagnosis of pulmonary embolisms, which can be difficult to catch. But now there’s more discussion of the other side of the issue—over-diagnosis and over-treatment—where we’re also trying to avoid, for example, overuse of CT scans.”

Another major thrust of Dr. Minichiello’s presentations involved bridging therapies, the application of a parenteral, short-acting anticoagulant therapy during the temporary interruption of warfarin anticoagulation for an invasive procedure. Bridging decreases stroke and embolism risk, but with an increased risk for bleeding.

“Full intensity bridging therapy for anticoagulation potentially can do more harm than good,” she said, noting a dearth of data to support mortality benefits of bridging therapy.

Literature increasingly recommends hospitalists be more selective about the use of bridging therapies that might have been employed reflexively in the past, she noted.

“[Hospitalists] must be mindful of the risks and benefits,” she said.

Physicians should also think twice about concomitant antiplatelet therapy like aspirin with anticoagulants. “We need to work collaboratively with our cardiology colleagues when a patient is on two or three of these therapies,” she said. “Recommendations in this area are in evolution.”

Elise Bouchard, MD, an internist at Centre Maria-Chapdelaine in Dolbeau-Mistassini, Quebec, attended Dr. Minichiello’s breakout session on challenging cases.

“I learned that we shouldn’t use aspirin with Coumadin or other anticoagulants, except for cases like acute coronary syndrome,” Dr. Bouchard said. She also explained a number of her patients with cancer, for example, need anticoagulation treatment and hate getting another injection, so she tries when possible to offer the oral anticoagulants.

Dr. Minichiello works with hospitalists at the San Francisco VA who seek consults around procedures, anticoagulant choices, and when to restart treatments.

“Most hospitalists don’t have access to a service like ours, although they might be able to call on a hematology consult service [or pharmacist],” she said. She suggested hospitalists trying to develop their own evidenced-based protocols use websites like the University of Washington’s anticoagulation service website, or the American Society of Health System Pharmacists’ anticoagulation resource center. TH

"Wish List" Outlines Patients' Expectations for Hospital Stays, and Some Easy Fixes

So, how does this apply to hospitalists? Many of the items on the list are an easy fix and don't cost a thing. Here are a few areas hospitalist can impact:

- I want to sleep. For example: are there standing overnight test orders that could be provided during the day?

- Reduce noise outside my room, particularly at night. How can hospitalists contribute to reducing hallway and nursing station noise?

- Knock before entering. It's a sign of respect to knock before entering the patient's room. Sitting down while talking to the patient and introducing yourself are also key.

- Keep me (and my family) updated. Are you always updating the patient and family about the plan of care and if things change?

- I want to be a part of my care. Do you always use language patients (and families) can easily understand? How do you ensure patients (and families) understand the plan of care?

- Be professional, always. No matter where you are in the hospital, patients and families are watching you closely. Ask yourself, "How I perceive you is often how I perceive the hospital and care that I am receiving."

What else can you do to improve the patient's experience in your hospital? TH

So, how does this apply to hospitalists? Many of the items on the list are an easy fix and don't cost a thing. Here are a few areas hospitalist can impact:

- I want to sleep. For example: are there standing overnight test orders that could be provided during the day?

- Reduce noise outside my room, particularly at night. How can hospitalists contribute to reducing hallway and nursing station noise?

- Knock before entering. It's a sign of respect to knock before entering the patient's room. Sitting down while talking to the patient and introducing yourself are also key.

- Keep me (and my family) updated. Are you always updating the patient and family about the plan of care and if things change?

- I want to be a part of my care. Do you always use language patients (and families) can easily understand? How do you ensure patients (and families) understand the plan of care?

- Be professional, always. No matter where you are in the hospital, patients and families are watching you closely. Ask yourself, "How I perceive you is often how I perceive the hospital and care that I am receiving."

What else can you do to improve the patient's experience in your hospital? TH

So, how does this apply to hospitalists? Many of the items on the list are an easy fix and don't cost a thing. Here are a few areas hospitalist can impact:

- I want to sleep. For example: are there standing overnight test orders that could be provided during the day?

- Reduce noise outside my room, particularly at night. How can hospitalists contribute to reducing hallway and nursing station noise?

- Knock before entering. It's a sign of respect to knock before entering the patient's room. Sitting down while talking to the patient and introducing yourself are also key.

- Keep me (and my family) updated. Are you always updating the patient and family about the plan of care and if things change?

- I want to be a part of my care. Do you always use language patients (and families) can easily understand? How do you ensure patients (and families) understand the plan of care?

- Be professional, always. No matter where you are in the hospital, patients and families are watching you closely. Ask yourself, "How I perceive you is often how I perceive the hospital and care that I am receiving."

What else can you do to improve the patient's experience in your hospital? TH

Yoga-Based Classes for Veterans With Severe Mental Illness: Development, Dissemination, and Assessment

There is growing interest in developing a holistic and integrative approach for the treatment of severe mental illnesses (SMI), such as schizophrenia, major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorders. Western medicine has traditionally focused on the direct treatment of symptoms and separated the management of physical and mental health, but increasing attention is being given to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for patients with SMI.

Recognizing the connectedness of the mind and body, these complementary or alternative approaches incorporate nontraditional therapeutic techniques with mainstream treatment methods, including psychopharmacology and psychotherapy.1 Patients with SMI may particularly benefit from a mind-body therapeutic approach, because they often experience psychological symptoms such as stress, anxiety, depression and psychosis, as well as a preponderance of medical comorbidities, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, some of which are compounded by adverse effects (AEs) of essential pharmacologic treatments.2-4 Mind-body interventions might also be particularly advantageous for veterans, who often experience a range of interconnected physical and psychological difficulties due to trauma exposure and challenges transitioning from military to civilian life.5

Related: Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

In 2002, the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy issued a report supporting CAM research and integration into existing medical systems.6 The DoD later established Total Force Fitness, a holistic health care program for active-duty military personnel.7 The VA has also incorporated mind-body and holistic strategies into veteran care.8 One such mind-body intervention, yoga, is becoming increasingly popular within the health care field.

Recent research has documented the effectiveness of yoga, underscoring its utility as a mind-body therapeutic approach. Yoga is associated with improvement in balance and flexibility,9 fatigue,10 blood pressure,11 sleep,12 strength,13 and pain14 in both healthy individuals and patients with medical and psychiatric disorders.15 The literature also illustrates that yoga has led to significant improvements in stress and psychiatric symptoms in individuals with PTSD, schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety.16-22 A previous meta-analysis conducted by the authors, which considered studies of the effectiveness of yoga as an adjunctive treatment for patients with mental illness, found that 212 studies with null results would need to be located and incorporated to negate the positive effects of yoga found in the literature.17

Because yoga emphasizes the practice of mindfulness and timing movement with breath awareness, it is a calming practice that may decrease stress and relieve psychiatric symptoms not treated through psychopharmacology and psychotherapy.17,21 Recent research has postulated that the physiological mechanisms by which this occurs may include (a) reduction in sympathetic and increase in parasympathetic activity23,24; (b) increases in heart-rate variability and respiratory sinus arrhythmia, low levels of which are associated with anxiety, panic disorder, and depression23,24; (c) increases in melatonin and serotonin 25-27; and (d) decrease in cortisol.28,29

Related: Enhancing Patient Satisfaction Through the Use of Complementary Therapies

As yoga may calm the autonomic nervous system and reduce stress, it may benefit patients with SMI, whose symptoms are often aggravated by stress.30 In addition, veterans experience both acute stressors and high levels of chronic stress.5 Therefore, because they experience mind-body comorbid illnesses as well as high levels of stress, the authors believe that veterans with SMI could benefit greatly from a tailored yoga-based program as part of a holistic approach that includes necessary medication and evidence-based therapies.

In order to evaluate the effects of a yoga program on veterans receiving mental health treatment across the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS), the authors developed a set of yoga-based wellness classes called Breathing, Stretching, Relaxation (BSR) classes. This article describes the process of developing these classes and outlines the procedures and results of a study to assess their effects.

BSR Classes

The development of BSR classes took place at the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC), within the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Center (PRRC) program. The PRRC is a psychoeducational program that focuses on the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of life in order to help veterans with SMI rehabilitate and reintegrate into the community. The program allows veterans to create their own recovery curriculum by selecting from diverse classes led by program staff members, including physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, and recreational therapists.

Development of BSR Protocols

The primary goal of this project was to develop a yoga-based program tailored to the specific needs of veterans with SMI. To the authors’ knowledge, BSR is the first yoga-based program customized for SMI. The BSR classes were developed within interdisciplinary focus groups that included professional yoga teachers, the director of the PRRC, psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, and physical therapists. Drawing on their experience with SMI and yoga, members of the focus groups identified 3 aspects of yoga that would be most beneficial to veterans with SMI, and the program was designed to optimize these effects. Because SMI can both create and be exacerbated by stress, BSR classes were designed to reduce stress and provide veterans with the tools to monitor and manage their stress.

Breathing and meditative techniques were adapted from yoga in order to facilitate stress reduction. In addition, aerobic elements of yoga have the potential to help veterans manage their incidence of medical diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes. Patients with SMI are at a greater risk for developing these diseases, so classes were designed to incorporate physical stretching elements to promote overall health.4,31-33 Finally BSR was designed to improve veteran self- efficacy and self-esteem, and to place veterans at the center of their care by equipping them with skills to practice BSR independently.

Related: Mindfulness to Reduce Stress

The focus groups also identified the logistic requirements when implementing a yoga-based program for veterans with SMI, including (a) obtaining participant or conservator consent; (b) obtaining medical clearance from care providers, given the high prevalence of medical comorbidities; (c) removing the traditional yoga terms, taking a secular approach, and naming the class “Breathing, Stretching, Relaxation” without directly referencing yoga; (d) asking veterans’ permission before incorporating physical contact into demonstrations, because veterans with SMI, especially those with PTSD, might be uncomfortable with touching from instructors; (e) creating protocols of varying duration and intensity so that BSR was approachable for veterans with diverse levels of physical ability; and (f) ensuring that a clinician who regularly works with SMI patients be present to supervise classes for the safety of patients and instructors.

Yoga instructors and clinicians collaborated to create adaptable 30- and 50-minute protocols that reflected best practices for an SMI population. The 30-minute seated BSR class protocol is included in eAppendix A. Once protocols were finalized, a Train the Trainer program was established to facilitate dissemination of BSR to clinicians working with veterans with SMI throughout the VAGLAHS.

Interested clinicians were given protocols and trained to lead BSR classes on their own. Subsequently, clinician-led BSR classes of various lengths (depending on clinician preference and program scheduling) were established at PRRCs and other mental health programs, such as Mental Health Recovery and Intensive Treatment and Dual Diagnosis Treatment Program, throughout the VAGLAHS. These programs were selected, because they are centered on recovery and improvements in symptoms of SMI. The adoption of a Train the Trainer model, through which VA clinicians were trained by professional yoga instructors, allowed for seamless integration of BSR into VA usual care for veterans with SMI.

Assessment of Classes

The authors conducted a study to assess the quality and effectiveness of BSR classes. This survey research was approved by the VAGLAHS institutional review board for human subjects. The authors hypothesized that there would be significant improvements in veterans’ stress, pain, well-being, and perception of the benefits of BSR over 8 weeks of participation in classes. Also hypothesized was that there would be greater benefits in veterans who participated in longer classes and who attended classes more frequently.

Methods

A total of 120 veterans completed surveys after participating in clinician- and yoga instructor-led BSR classes at the 3 sites within the VAGLAHS: WLAVAMC, Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC), and Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center (SACC). At the WLAVAMC, surveys were collected at 10-, 30-, 60-, and 90-minute classes. At LAACC, surveys were collected at 30- and 60-minute classes. At SACC, surveys were collected at 20- and 45-minute classes. A researcher noted the duration of the class and was available to assist with comprehension. Veterans completed identical surveys after classes at a designated week 0 (baseline), week 4, and week 8. Of the 120 patients with an initial survey, 82 completed at least 1 follow-up survey and 49 completed both follow-up surveys.

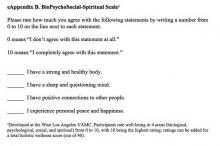

Survey packets included (a) demographic questions, including age, gender, and ethnicity; (b) class participation questions, including frequency of class attendance, patients’ favorite aspect of class, and dura tion of class attendance (in months of prior participation); (c) a pain rating from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable); (d) the BioPsychoSocial-Spiritual (BPSS) Scale (eAppendix B), developed at the WLAVAMC, which provides wellness scores from 0 (low) to 10 (high) in 4 areas as well as a holistic wellness score from 0 (low) to 40 (high); (e) the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), developed by Cohen and colleagues, which generates a stress score for the past month from 0 (low) to 40 (high)34; and (f) the Perceived Benefits of Yoga Questionnaire (PBYQ) (eAppendix C), which rates participants’ opinions about the benefits of yoga from 12 (low) to 60 (high) and is based on the Perceived Benefits of Dance Questionnaire.35

Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s r correlation coefficients were calculated between PBYQ scores and quantitative survey items at each time point (weeks 0, 4, and 8). Linear mixed-effects models were used to test for effects of multiple predictor variables on individual outcomes. Each model had a random intercept by participant, and regressors included main effects for the following: survey week (0, 4, or 8), class duration (in minutes), age, sex, ethnicity, frequency of attendance (in days per week), and duration of attendance (in months). For all statistical analyses, a 2-tailed significance criterion of α = .05 was used.

Results

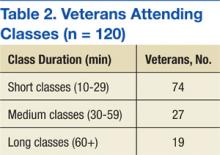

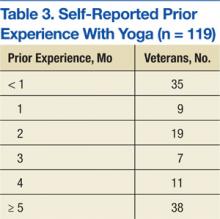

Veterans who completed surveys were predominantly male (90.8%) and averaged 61.4 years of age. Table 1 shows demographic information. Table 2 displays the number of participants who were involved in short (< 30 min), medium (30-59 min), and long (> 60 min) classes. Veteran participants also had a wide range of prior BSR experience (Table 3).

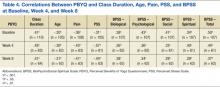

At all time points, PBYQ scores were significantly positively correlated with class duration and biological, psychological, social, spiritual, and total well-being as measured by the BPSS. The PBYQ scores at all time points were also significantly negatively correlated with age, pain ratings, and PSS scores. Table 4 includes specific Pearson’s r values.

Survey week was not significantly associated with any individual outcome measures. There were no significant regressors for total PSS score or total BPSS score within the linear models. However, participants’ PBYQ scores were significantly associated with age (t(98) = -2.13, P = .036), frequency of attendance (t(103) = 2.10, P = .038), and class duration (t(98) = 4.35, P < .001). Additionally, class duration was significantly associated with pain (t(98) = -3.01, P = .003), with longer duration associated with less pain. Ethnicity was also associated with pain, with African American veterans reporting less pain than did white (t(98) = -2.41, P = .017) and Hispanic (t(98) = -2.31, P = .023) veterans. Because ethnicity was significantly associated with class duration (F(5,339) = 3.81, P = .002), the authors used an analysis of covariance to test for a mediating effect of ethnicity on the relationship between class duration and pain. Although there was a partial mediation (F(5,203) = 2.57, P = .028), the main effect of class duration remained significant.

Discussion and Limitations

The goals of this project were to develop a yoga-based program tailored for veterans with SMI and assess the program in a sample of veterans with SMI on subjective reports of stress, pain, well-being, and benefits of yoga. The authors hypothesized that significant improvements in these measures in veterans with SMI would be observed over 8 weeks of participation in BSR classes and that there would be greater benefits in veterans who participated in longer classes and who attended classes more frequently.

The authors succeeded in developing an adaptable yoga-based wellness program for veterans with SMI that can be both practiced in structured classes and incorporated into veterans’ everyday routines. The BSR classes were well tolerated by veterans with SMI, caused no discernible AEs, and are readily available for dissemination across other mental health programs. Veterans described integrating the tools they learned within BSR classes into their daily lives, helping them to manage pain; feel more flexible; reduce stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms; and increase relaxation and feelings of self-control and confidence. Table 5 shows qualitative feedback collected from veterans. In addition, the Train the Trainer model optimized clinical applicability and flexibility, demonstrating that clinicians can seamlessly integrate BSR classes into a health care plan for veterans with SMI.

In assessing quantitative measures of stress, pain, well-being, and perceived benefits of a yoga-based program, veterans who reported BSR classes as beneficial experienced lower levels of pain and stress and higher levels of biological, psychological, social, spiritual, and overall well-being. Those veterans who perceived BSR as more beneficial tended to be younger and attend longer classes with greater frequency. Veterans who attended longer classes also reported experiencing less pain. This may be because the more rigorous stretching and posing involved in longer BSR classes made them more effective at reducing pain; however, it is also possible that veterans who were experiencing more pain avoided these longer classes due to their rigor and length.

Results suggest that longer classes attended with greater regularity may be more beneficial to veterans than short and infrequent classes, particularly in regards to their pain. Despite the relationships between class and outcome variables, the authors did not find significant improvements in measures of wellness, pain, stress, or perceived benefits of BSR over time, as was hypothesized. This may be because the data collection for this study began after classes had been established for some time. In fact, only 35 of 120 veterans included in this study reported having < 1 month of BSR experience at week 0, suggesting that results collected from week 0 did not represent a true baseline measurement. Although no relationship was found between prior duration of attendance and any outcome measures, the fact that most veterans in the sample had attended classes for several months prior to completing surveys may have biased the results by favoring the responses of veterans who were more invested in the classes. Improvements may have been better captured in a BSR-naïve sample.

The finding that the PBYQ score was significantly correlated with all other outcome measures (pain, BPSS score, and PSS score) raises some questions about the ways in which these classes were beneficial to veterans. It may be that veterans who experienced more positive outcomes from classes saw BSR as more beneficial, but it is also possible that veterans who entered classes with greater expectations experienced better outcomes due to a placebo effect—that is, outcomes may have been influenced more by the expectation than by the content of the classes. In the case of well-being (BPSS scores) and stress (PSS score), this could explain why these outcomes were significantly correlated with perceived benefits of BSR but were not significantly related to any class-related variables such as duration and frequency of attendance. Pain ratings, however, were related to class variables and perceived benefits of BSR.