User login

Use of NIPT reduces invasive testing at one medical center

Following the introduction of noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) at the Maine Medical Center in Portland, the number of invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures decreased.

In a retrospective study, Joseph R. Wax, MD, and colleagues gathered statistics on the rates of genetic counseling, invasive prenatal diagnosis, and trisomy 21 detection among women who were at increased risk for aneuploidy. These rates were compared before and after the availability of NIPT.

The study included 1,046 women who underwent NIPT between June 1, 2012, and February 1, 2013, as well as 1,464 women who would have been eligible for NIPT if it had been available between December 1, 2010, and November 30, 2011. All women were aged 35 years or older and had ultrasound findings suggestive of increased risk of aneuploidy, a positive aneuploidy screen, prior trisomic fetus, or parental balanced translocation with increased risk for trisomy 13 or 21. One laboratory performed NIPT after patients received genetic counseling. The two groups were compared by maternal demographics, aneuploidy risk factors, rates of genetic counseling, invasive diagnostic procedures, and trisomy 21 detection.1

Results of the study

A total of 33 fetuses with trisomy 21 were identified by positive aneuploidy screening. After the introduction of NIPT, genetic counseling for aneuploidy risk increased (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.77; P <.0001). However, the overall use of invasive diagnostic testing (aOR, 0.42; P <.0001), including amniocentesis (aOR, 0.37, P <.0001), decreased, although the prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 21 remained similar (88% vs 100%; P = .86).1

Dr. Wax and colleagues concluded that, “NIPT in clinical practice uses more genetic counseling resources but requires significantly fewer invasive procedures to maintain the detection rates of trisomy 21.”1

Reference

1. Wax JR, Cartin A, Chard R, Lucas FL, Pinette MG. Noninvasive prenatal testing: Impact on genetic counseling, invasive prenatal diagnosis, and trisomy 21 detection. J Clinic Ultrasound. 2015;43(1):1–6.

Following the introduction of noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) at the Maine Medical Center in Portland, the number of invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures decreased.

In a retrospective study, Joseph R. Wax, MD, and colleagues gathered statistics on the rates of genetic counseling, invasive prenatal diagnosis, and trisomy 21 detection among women who were at increased risk for aneuploidy. These rates were compared before and after the availability of NIPT.

The study included 1,046 women who underwent NIPT between June 1, 2012, and February 1, 2013, as well as 1,464 women who would have been eligible for NIPT if it had been available between December 1, 2010, and November 30, 2011. All women were aged 35 years or older and had ultrasound findings suggestive of increased risk of aneuploidy, a positive aneuploidy screen, prior trisomic fetus, or parental balanced translocation with increased risk for trisomy 13 or 21. One laboratory performed NIPT after patients received genetic counseling. The two groups were compared by maternal demographics, aneuploidy risk factors, rates of genetic counseling, invasive diagnostic procedures, and trisomy 21 detection.1

Results of the study

A total of 33 fetuses with trisomy 21 were identified by positive aneuploidy screening. After the introduction of NIPT, genetic counseling for aneuploidy risk increased (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.77; P <.0001). However, the overall use of invasive diagnostic testing (aOR, 0.42; P <.0001), including amniocentesis (aOR, 0.37, P <.0001), decreased, although the prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 21 remained similar (88% vs 100%; P = .86).1

Dr. Wax and colleagues concluded that, “NIPT in clinical practice uses more genetic counseling resources but requires significantly fewer invasive procedures to maintain the detection rates of trisomy 21.”1

Following the introduction of noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) at the Maine Medical Center in Portland, the number of invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures decreased.

In a retrospective study, Joseph R. Wax, MD, and colleagues gathered statistics on the rates of genetic counseling, invasive prenatal diagnosis, and trisomy 21 detection among women who were at increased risk for aneuploidy. These rates were compared before and after the availability of NIPT.

The study included 1,046 women who underwent NIPT between June 1, 2012, and February 1, 2013, as well as 1,464 women who would have been eligible for NIPT if it had been available between December 1, 2010, and November 30, 2011. All women were aged 35 years or older and had ultrasound findings suggestive of increased risk of aneuploidy, a positive aneuploidy screen, prior trisomic fetus, or parental balanced translocation with increased risk for trisomy 13 or 21. One laboratory performed NIPT after patients received genetic counseling. The two groups were compared by maternal demographics, aneuploidy risk factors, rates of genetic counseling, invasive diagnostic procedures, and trisomy 21 detection.1

Results of the study

A total of 33 fetuses with trisomy 21 were identified by positive aneuploidy screening. After the introduction of NIPT, genetic counseling for aneuploidy risk increased (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.77; P <.0001). However, the overall use of invasive diagnostic testing (aOR, 0.42; P <.0001), including amniocentesis (aOR, 0.37, P <.0001), decreased, although the prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 21 remained similar (88% vs 100%; P = .86).1

Dr. Wax and colleagues concluded that, “NIPT in clinical practice uses more genetic counseling resources but requires significantly fewer invasive procedures to maintain the detection rates of trisomy 21.”1

Reference

1. Wax JR, Cartin A, Chard R, Lucas FL, Pinette MG. Noninvasive prenatal testing: Impact on genetic counseling, invasive prenatal diagnosis, and trisomy 21 detection. J Clinic Ultrasound. 2015;43(1):1–6.

Reference

1. Wax JR, Cartin A, Chard R, Lucas FL, Pinette MG. Noninvasive prenatal testing: Impact on genetic counseling, invasive prenatal diagnosis, and trisomy 21 detection. J Clinic Ultrasound. 2015;43(1):1–6.

ACOG offers strategies to reduce unintended pregnancy

A new Committee Opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Obstetrics & Gynecology outlines the current barriers women face when attempting to obtain contraception and provides strategies to overcome these barriers.

Unintended pregnancy and abortion rates are higher in the United States than in most other developed countries, says ACOG; the most recent data report that 49% of US pregnancies are unintended.1

The cost of unintended pregnancy

The human cost of unintended pregnancy is high, says ACOG, because women must choose to carry the pregnancy to term and keep the baby, decide for adoption, or undergo abortion. Women and their families struggle with this challenge for medical, ethical, social, legal, and financial reasons. US births from unintended pregnancies resulted in approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008. Affordable access to contraceptives would not only improve health but also reduce costs, as each dollar spent on publicly funded contraceptive services saves the US health-care system nearly $6.1

“The most effective way to reduce abortion rates is to prevent unintended pregnancy by improving access to consistent, effective, and affordable contraception,” states the Committee Opinion.1

What are barriers to use?

Major barriers to contraceptive use include lack of knowledge, misperceptions, and exaggerated concerns about safety among patients and health-care professionals, says the Committee.

Patients are concerned that oral contraceptives are linked to major health problems, that intrauterine devices (IUDs) carry a high risk of infection, and that certain contraceptives are abortifacients (although no FDA-approved contraceptive is an abortifacient).

Health-care professionals also may have knowledge deficits: some are uncertain about the risks and benefits of IUDs and lack knowledge about correct patient selection and contraindications.1

What strategies does ACOG support?

One in four American women who obtain contraceptive services seek them at publicly funded family planning clinics, cites ACOG.1 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides that all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient contraceptive education and counseling are covered for women without cost sharing for all new and revised health plans and Medicaid. However, many employers are now exempt. Women covered by exempted employers and those who remain uninsured will not benefit from ACA coverage. For these women, cost barriers persist and the most effective methods (IUDs, contraceptive implant) likely will be unattainable, says ACOG.1

Insurance companies, clinic systems, or pharmacy and therapeutics committees create additional barriers, including the number of products dispensed at one time. Insurance plans prevent 73% of women from receiving more than a 1 month supply of contraception at a time, yet most women are unable to obtain refills on a timely basis. Some systems require that women “fail” certain contraceptive methods before a more expensive method (IUD, implant) will be covered. ACOG states: “All FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be available to all insured women without cost sharing and without the need to ‘fail’ certain methods first. In the absence of contraindications, patient choice and efficacy should be the principal factors in choosing one method of contraception over another.”1

Additional strategies ACOG supports and recommends to ensure affordable and accessible contraception include:

- Full implementation of the ACA requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all FDA-approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options from within one method category (levonorgestrel as well as copper IUDs)

- Easily accessible alternative contraceptive coverage for women who receive health insurance through employers and plans exempted from the contraceptive coverage requirement

- Medicaid expansion in all states, an action critical to the ability of low-income women to obtain improved access to contraceptives

- Adequate funding for the federal Title X family planning program and Medicaid family planning services to ensure contraceptive availability for low-income women, including the use of public funds for contraceptive provision at the time of abortion

- Sufficient compensation for contraceptive services by public and private payers to ensure access, including appropriate payment for clinician services and acquisition-cost reimbursement for supplies

- Age-appropriate, medically accurate, comprehensive sexuality education that includes information on abstinence as well as the full range of FDA-approved contraceptives

- Confidential, comprehensive contraceptive care and access to contraceptive methods for adolescents without mandated parental notification or consent, including confidentiality in billing and insurance claims processing procedures

To see all of ACOG’s recommendations, access the full report.

Reference

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 615: Access to Contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):250–255. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20150102T2211197738.

A new Committee Opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Obstetrics & Gynecology outlines the current barriers women face when attempting to obtain contraception and provides strategies to overcome these barriers.

Unintended pregnancy and abortion rates are higher in the United States than in most other developed countries, says ACOG; the most recent data report that 49% of US pregnancies are unintended.1

The cost of unintended pregnancy

The human cost of unintended pregnancy is high, says ACOG, because women must choose to carry the pregnancy to term and keep the baby, decide for adoption, or undergo abortion. Women and their families struggle with this challenge for medical, ethical, social, legal, and financial reasons. US births from unintended pregnancies resulted in approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008. Affordable access to contraceptives would not only improve health but also reduce costs, as each dollar spent on publicly funded contraceptive services saves the US health-care system nearly $6.1

“The most effective way to reduce abortion rates is to prevent unintended pregnancy by improving access to consistent, effective, and affordable contraception,” states the Committee Opinion.1

What are barriers to use?

Major barriers to contraceptive use include lack of knowledge, misperceptions, and exaggerated concerns about safety among patients and health-care professionals, says the Committee.

Patients are concerned that oral contraceptives are linked to major health problems, that intrauterine devices (IUDs) carry a high risk of infection, and that certain contraceptives are abortifacients (although no FDA-approved contraceptive is an abortifacient).

Health-care professionals also may have knowledge deficits: some are uncertain about the risks and benefits of IUDs and lack knowledge about correct patient selection and contraindications.1

What strategies does ACOG support?

One in four American women who obtain contraceptive services seek them at publicly funded family planning clinics, cites ACOG.1 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides that all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient contraceptive education and counseling are covered for women without cost sharing for all new and revised health plans and Medicaid. However, many employers are now exempt. Women covered by exempted employers and those who remain uninsured will not benefit from ACA coverage. For these women, cost barriers persist and the most effective methods (IUDs, contraceptive implant) likely will be unattainable, says ACOG.1

Insurance companies, clinic systems, or pharmacy and therapeutics committees create additional barriers, including the number of products dispensed at one time. Insurance plans prevent 73% of women from receiving more than a 1 month supply of contraception at a time, yet most women are unable to obtain refills on a timely basis. Some systems require that women “fail” certain contraceptive methods before a more expensive method (IUD, implant) will be covered. ACOG states: “All FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be available to all insured women without cost sharing and without the need to ‘fail’ certain methods first. In the absence of contraindications, patient choice and efficacy should be the principal factors in choosing one method of contraception over another.”1

Additional strategies ACOG supports and recommends to ensure affordable and accessible contraception include:

- Full implementation of the ACA requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all FDA-approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options from within one method category (levonorgestrel as well as copper IUDs)

- Easily accessible alternative contraceptive coverage for women who receive health insurance through employers and plans exempted from the contraceptive coverage requirement

- Medicaid expansion in all states, an action critical to the ability of low-income women to obtain improved access to contraceptives

- Adequate funding for the federal Title X family planning program and Medicaid family planning services to ensure contraceptive availability for low-income women, including the use of public funds for contraceptive provision at the time of abortion

- Sufficient compensation for contraceptive services by public and private payers to ensure access, including appropriate payment for clinician services and acquisition-cost reimbursement for supplies

- Age-appropriate, medically accurate, comprehensive sexuality education that includes information on abstinence as well as the full range of FDA-approved contraceptives

- Confidential, comprehensive contraceptive care and access to contraceptive methods for adolescents without mandated parental notification or consent, including confidentiality in billing and insurance claims processing procedures

To see all of ACOG’s recommendations, access the full report.

A new Committee Opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Obstetrics & Gynecology outlines the current barriers women face when attempting to obtain contraception and provides strategies to overcome these barriers.

Unintended pregnancy and abortion rates are higher in the United States than in most other developed countries, says ACOG; the most recent data report that 49% of US pregnancies are unintended.1

The cost of unintended pregnancy

The human cost of unintended pregnancy is high, says ACOG, because women must choose to carry the pregnancy to term and keep the baby, decide for adoption, or undergo abortion. Women and their families struggle with this challenge for medical, ethical, social, legal, and financial reasons. US births from unintended pregnancies resulted in approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008. Affordable access to contraceptives would not only improve health but also reduce costs, as each dollar spent on publicly funded contraceptive services saves the US health-care system nearly $6.1

“The most effective way to reduce abortion rates is to prevent unintended pregnancy by improving access to consistent, effective, and affordable contraception,” states the Committee Opinion.1

What are barriers to use?

Major barriers to contraceptive use include lack of knowledge, misperceptions, and exaggerated concerns about safety among patients and health-care professionals, says the Committee.

Patients are concerned that oral contraceptives are linked to major health problems, that intrauterine devices (IUDs) carry a high risk of infection, and that certain contraceptives are abortifacients (although no FDA-approved contraceptive is an abortifacient).

Health-care professionals also may have knowledge deficits: some are uncertain about the risks and benefits of IUDs and lack knowledge about correct patient selection and contraindications.1

What strategies does ACOG support?

One in four American women who obtain contraceptive services seek them at publicly funded family planning clinics, cites ACOG.1 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides that all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient contraceptive education and counseling are covered for women without cost sharing for all new and revised health plans and Medicaid. However, many employers are now exempt. Women covered by exempted employers and those who remain uninsured will not benefit from ACA coverage. For these women, cost barriers persist and the most effective methods (IUDs, contraceptive implant) likely will be unattainable, says ACOG.1

Insurance companies, clinic systems, or pharmacy and therapeutics committees create additional barriers, including the number of products dispensed at one time. Insurance plans prevent 73% of women from receiving more than a 1 month supply of contraception at a time, yet most women are unable to obtain refills on a timely basis. Some systems require that women “fail” certain contraceptive methods before a more expensive method (IUD, implant) will be covered. ACOG states: “All FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be available to all insured women without cost sharing and without the need to ‘fail’ certain methods first. In the absence of contraindications, patient choice and efficacy should be the principal factors in choosing one method of contraception over another.”1

Additional strategies ACOG supports and recommends to ensure affordable and accessible contraception include:

- Full implementation of the ACA requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all FDA-approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options from within one method category (levonorgestrel as well as copper IUDs)

- Easily accessible alternative contraceptive coverage for women who receive health insurance through employers and plans exempted from the contraceptive coverage requirement

- Medicaid expansion in all states, an action critical to the ability of low-income women to obtain improved access to contraceptives

- Adequate funding for the federal Title X family planning program and Medicaid family planning services to ensure contraceptive availability for low-income women, including the use of public funds for contraceptive provision at the time of abortion

- Sufficient compensation for contraceptive services by public and private payers to ensure access, including appropriate payment for clinician services and acquisition-cost reimbursement for supplies

- Age-appropriate, medically accurate, comprehensive sexuality education that includes information on abstinence as well as the full range of FDA-approved contraceptives

- Confidential, comprehensive contraceptive care and access to contraceptive methods for adolescents without mandated parental notification or consent, including confidentiality in billing and insurance claims processing procedures

To see all of ACOG’s recommendations, access the full report.

Reference

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 615: Access to Contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):250–255. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20150102T2211197738.

Reference

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 615: Access to Contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):250–255. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20150102T2211197738.

At what endometrial thickness should biopsy be performed in postmenopausal women without vaginal bleeding?

With no consensus regarding the normal endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women without vaginal bleeding, there are no guidelines for clinicians to follow on when to biopsy, if at all, in an older patient presenting with pelvic pain but no bleeding.

To determine at what endometrial thickness biopsy would be optimal, Michelle Louie, MD, and colleagues from Magee Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, performed a retrospective cohort analysis of postmenopausal women aged 50 or older who underwent transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) for indications other than vaginal bleeding. They presented their findings in an abstract at the 43rd AAGL Global Congress in Vancouver, Canada.

Details of the study

Patients were included if they had an endometrial lining of 4 mm or greater and excluded if they had a history of tamoxifen use, hormone replacement, endometrial ablation, hereditary cancer syndrome, or no available pathology results.

Of 462 biopsies, 435 (94.2%) had benign pathology, nine (2.0%) had carcinoma, and seven (1.5%) had atypical hyperplasia.

Endometrial thickness of 14 mm or greater was associated with atypical hyperplasia (odds ratio [OR], 4.29; P = .02), with a negative predictive value of 98.3%. A thickness of 15 mm or greater was associated with carcinoma (OR, 4.53; P = .03), with a negative predictive value of 98.5%.

Under 14 mm, the risk of hyperplasia was low, the authors found, at 0.08%. Below 15 mm, the risk of cancer was 0.06%.

They found no significant associations between endometrial lining TVUS appearance, age, parity, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and carcinoma or atypical hyperplasia.

When biopsy might not be necessary

Therefore, regardless of conventional risk factors for endometrial cancer, if a postmenopausal woman reports pelvic pain without vaginal bleeding, and is found to have a thickened endometrial lining of less than 14 mm on TVUS, biopsy might not be warranted, conclude the study authors.

Reference

Louie M, Canavan T, Mansuria S. Threshold for endometrial biopsy in postmenopausal patients without vaginal bleeding. Abstract presented at: 43rd AAGL Global Congress; November 2014; Vancouver, Canada.

With no consensus regarding the normal endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women without vaginal bleeding, there are no guidelines for clinicians to follow on when to biopsy, if at all, in an older patient presenting with pelvic pain but no bleeding.

To determine at what endometrial thickness biopsy would be optimal, Michelle Louie, MD, and colleagues from Magee Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, performed a retrospective cohort analysis of postmenopausal women aged 50 or older who underwent transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) for indications other than vaginal bleeding. They presented their findings in an abstract at the 43rd AAGL Global Congress in Vancouver, Canada.

Details of the study

Patients were included if they had an endometrial lining of 4 mm or greater and excluded if they had a history of tamoxifen use, hormone replacement, endometrial ablation, hereditary cancer syndrome, or no available pathology results.

Of 462 biopsies, 435 (94.2%) had benign pathology, nine (2.0%) had carcinoma, and seven (1.5%) had atypical hyperplasia.

Endometrial thickness of 14 mm or greater was associated with atypical hyperplasia (odds ratio [OR], 4.29; P = .02), with a negative predictive value of 98.3%. A thickness of 15 mm or greater was associated with carcinoma (OR, 4.53; P = .03), with a negative predictive value of 98.5%.

Under 14 mm, the risk of hyperplasia was low, the authors found, at 0.08%. Below 15 mm, the risk of cancer was 0.06%.

They found no significant associations between endometrial lining TVUS appearance, age, parity, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and carcinoma or atypical hyperplasia.

When biopsy might not be necessary

Therefore, regardless of conventional risk factors for endometrial cancer, if a postmenopausal woman reports pelvic pain without vaginal bleeding, and is found to have a thickened endometrial lining of less than 14 mm on TVUS, biopsy might not be warranted, conclude the study authors.

With no consensus regarding the normal endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women without vaginal bleeding, there are no guidelines for clinicians to follow on when to biopsy, if at all, in an older patient presenting with pelvic pain but no bleeding.

To determine at what endometrial thickness biopsy would be optimal, Michelle Louie, MD, and colleagues from Magee Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, performed a retrospective cohort analysis of postmenopausal women aged 50 or older who underwent transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) for indications other than vaginal bleeding. They presented their findings in an abstract at the 43rd AAGL Global Congress in Vancouver, Canada.

Details of the study

Patients were included if they had an endometrial lining of 4 mm or greater and excluded if they had a history of tamoxifen use, hormone replacement, endometrial ablation, hereditary cancer syndrome, or no available pathology results.

Of 462 biopsies, 435 (94.2%) had benign pathology, nine (2.0%) had carcinoma, and seven (1.5%) had atypical hyperplasia.

Endometrial thickness of 14 mm or greater was associated with atypical hyperplasia (odds ratio [OR], 4.29; P = .02), with a negative predictive value of 98.3%. A thickness of 15 mm or greater was associated with carcinoma (OR, 4.53; P = .03), with a negative predictive value of 98.5%.

Under 14 mm, the risk of hyperplasia was low, the authors found, at 0.08%. Below 15 mm, the risk of cancer was 0.06%.

They found no significant associations between endometrial lining TVUS appearance, age, parity, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and carcinoma or atypical hyperplasia.

When biopsy might not be necessary

Therefore, regardless of conventional risk factors for endometrial cancer, if a postmenopausal woman reports pelvic pain without vaginal bleeding, and is found to have a thickened endometrial lining of less than 14 mm on TVUS, biopsy might not be warranted, conclude the study authors.

Reference

Louie M, Canavan T, Mansuria S. Threshold for endometrial biopsy in postmenopausal patients without vaginal bleeding. Abstract presented at: 43rd AAGL Global Congress; November 2014; Vancouver, Canada.

Reference

Louie M, Canavan T, Mansuria S. Threshold for endometrial biopsy in postmenopausal patients without vaginal bleeding. Abstract presented at: 43rd AAGL Global Congress; November 2014; Vancouver, Canada.

Best practices for the surgical management of adnexal masses in pregnancy

During the 43rd AAGL Global Congress, held November 17–21 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Sarah L. Cohen, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, stepped attendees through diagnosis and surgical management of adnexal masses in pregnancy, noting the approaches backed by the highest-quality data.

The incidence of adnexal masses in pregnancy is 1 in every 600 live births. A mass can be benign or malignant. Among benign masses found in pregnancy are functional cysts, teratomas, and the corpus luteum.

Work-up

Ultrasound imaging is a valuable component of the work-up, owing to its risk-free nature. Magnetic resonance imaging may be appropriate in selected cases, but gadolinium contrast should be avoided.

In pregnancy, the aim is to limit ionizing radiation to less than 5 to 10 rads to minimize the risk of childhood malignancy/leukemia, with no single imaging study exceeding 5 rads.

Tumor markers may be helpful, but careful interpretation is critical, taking into account the effects of pregnancy itself on CA-125 (which peaks in the first trimester), human chorionic gonadotropin, alpha fetoprotein, inhibin A, and lactate dehydrogenase.

When expectant management may be appropriate

Watchful waiting may be considered for simple cysts less than 6 cm in size, provided the patient is asymptomatic with no signs of malignancy.

Surgery is indicated when the patient is symptomatic, when there is a concern for malignancy, and when a persistent mass exceeds 10 cm in size.

As always, elective surgery is preferable, as emergent surgery in pregnancy is associated with a risk of preterm labor of 22% to 35%.

Optimal timing of surgery

Surgery can be performed safely in any trimester, provided the gynecologist is aware of special concerns. For example, in the first trimester, organogenesis is under way and the corpus luteum is still present. If the corpus luteum is removed, progesterone supplementation is necessary.

When surgery can be postponed to the second trimester, it allows time for possible resolution of the mass.

Mode of surgery

Laparoscopy allows for faster recovery, less pain (and, therefore, lower narcotic exposure to the fetus), and improved maternal ventilation.

Prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism is indicated through the use of pneumatic compression devices and, when appropriate, heparin.

Initial port placement can be performed using a Hassan technique, Veress needle, or optical trocar.

Insufflation pressures of 10 to 15 mm Hg are safe, with intraoperative monitoring of carbon dioxide.

Availability of guidelines

Surgeons should make use of guidelines, when feasible, to guide surgery. For example, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) publishes guidelines on surgery during pregnancy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also offers guidelines.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

During the 43rd AAGL Global Congress, held November 17–21 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Sarah L. Cohen, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, stepped attendees through diagnosis and surgical management of adnexal masses in pregnancy, noting the approaches backed by the highest-quality data.

The incidence of adnexal masses in pregnancy is 1 in every 600 live births. A mass can be benign or malignant. Among benign masses found in pregnancy are functional cysts, teratomas, and the corpus luteum.

Work-up

Ultrasound imaging is a valuable component of the work-up, owing to its risk-free nature. Magnetic resonance imaging may be appropriate in selected cases, but gadolinium contrast should be avoided.

In pregnancy, the aim is to limit ionizing radiation to less than 5 to 10 rads to minimize the risk of childhood malignancy/leukemia, with no single imaging study exceeding 5 rads.

Tumor markers may be helpful, but careful interpretation is critical, taking into account the effects of pregnancy itself on CA-125 (which peaks in the first trimester), human chorionic gonadotropin, alpha fetoprotein, inhibin A, and lactate dehydrogenase.

When expectant management may be appropriate

Watchful waiting may be considered for simple cysts less than 6 cm in size, provided the patient is asymptomatic with no signs of malignancy.

Surgery is indicated when the patient is symptomatic, when there is a concern for malignancy, and when a persistent mass exceeds 10 cm in size.

As always, elective surgery is preferable, as emergent surgery in pregnancy is associated with a risk of preterm labor of 22% to 35%.

Optimal timing of surgery

Surgery can be performed safely in any trimester, provided the gynecologist is aware of special concerns. For example, in the first trimester, organogenesis is under way and the corpus luteum is still present. If the corpus luteum is removed, progesterone supplementation is necessary.

When surgery can be postponed to the second trimester, it allows time for possible resolution of the mass.

Mode of surgery

Laparoscopy allows for faster recovery, less pain (and, therefore, lower narcotic exposure to the fetus), and improved maternal ventilation.

Prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism is indicated through the use of pneumatic compression devices and, when appropriate, heparin.

Initial port placement can be performed using a Hassan technique, Veress needle, or optical trocar.

Insufflation pressures of 10 to 15 mm Hg are safe, with intraoperative monitoring of carbon dioxide.

Availability of guidelines

Surgeons should make use of guidelines, when feasible, to guide surgery. For example, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) publishes guidelines on surgery during pregnancy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also offers guidelines.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

During the 43rd AAGL Global Congress, held November 17–21 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Sarah L. Cohen, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, stepped attendees through diagnosis and surgical management of adnexal masses in pregnancy, noting the approaches backed by the highest-quality data.

The incidence of adnexal masses in pregnancy is 1 in every 600 live births. A mass can be benign or malignant. Among benign masses found in pregnancy are functional cysts, teratomas, and the corpus luteum.

Work-up

Ultrasound imaging is a valuable component of the work-up, owing to its risk-free nature. Magnetic resonance imaging may be appropriate in selected cases, but gadolinium contrast should be avoided.

In pregnancy, the aim is to limit ionizing radiation to less than 5 to 10 rads to minimize the risk of childhood malignancy/leukemia, with no single imaging study exceeding 5 rads.

Tumor markers may be helpful, but careful interpretation is critical, taking into account the effects of pregnancy itself on CA-125 (which peaks in the first trimester), human chorionic gonadotropin, alpha fetoprotein, inhibin A, and lactate dehydrogenase.

When expectant management may be appropriate

Watchful waiting may be considered for simple cysts less than 6 cm in size, provided the patient is asymptomatic with no signs of malignancy.

Surgery is indicated when the patient is symptomatic, when there is a concern for malignancy, and when a persistent mass exceeds 10 cm in size.

As always, elective surgery is preferable, as emergent surgery in pregnancy is associated with a risk of preterm labor of 22% to 35%.

Optimal timing of surgery

Surgery can be performed safely in any trimester, provided the gynecologist is aware of special concerns. For example, in the first trimester, organogenesis is under way and the corpus luteum is still present. If the corpus luteum is removed, progesterone supplementation is necessary.

When surgery can be postponed to the second trimester, it allows time for possible resolution of the mass.

Mode of surgery

Laparoscopy allows for faster recovery, less pain (and, therefore, lower narcotic exposure to the fetus), and improved maternal ventilation.

Prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism is indicated through the use of pneumatic compression devices and, when appropriate, heparin.

Initial port placement can be performed using a Hassan technique, Veress needle, or optical trocar.

Insufflation pressures of 10 to 15 mm Hg are safe, with intraoperative monitoring of carbon dioxide.

Availability of guidelines

Surgeons should make use of guidelines, when feasible, to guide surgery. For example, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) publishes guidelines on surgery during pregnancy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also offers guidelines.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Clomiphene better than letrozole to treat women with unexplained infertility

When the cause of infertility is unexplained, what is the best first-choice treatment option? Could letrozole, an oral nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, result in fewer multiple gestations than current standard therapy—gonadotropins or selective estrogen receptor modulators (clomiphene citrate)—without worsening the live birth rate?

Researchers from the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) trial investigated this question and presented data at the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Study details

This prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial involved 900 women aged 18 to 40 with at least one patent fallopian tube and regular menses. Patients underwent ovarian stimulation for up to four cycles with an injectable gonadotropin (Gn; n = 300), clomiphene citrate (n = 301), or letrozole (n = 299), followed by intrauterine insemination (IUI).

Birth rate. Conception occurred in 46.8%, 35.7%, and 28.4% of women receiving Gn, clomiphene, and letrozole, respectively, with a live birth occurring in 32.2%, 23.3%, and 18.7% of respective cases. Pregnancy rates with letrozole were significantly less than with Gn (P<.001) and less than with clomiphene (P<.015).

Multiple gestations. The rate of multiple gestations was highest among women treated with Gn (10.3%). But the multiple gestation rate for letrozole was higher than that for clomiphene (2.7% vs 1.3%, respectively). All multiples treated with letrozole and clomiphene were twins; in the Gn group, there were 24 twin and 10 triplet gestations.

No significant difference was found in the rates of infants with congenital anomalies or other fetal or neonatal complications.1

Clomiphene plus IUI remains first-line therapy for unexplained infertility

Although ovarian stimulation with letrozole was safe overall, the number of live births was reduced when treatment with letrozole was compared with clomiphene or Gn, and the multiple pregnancy rate for letrozole fell between clomiphene and Gn.

“CC [clomiphene citrate] /IUI remains first-line therapy for women with unexplained infertility,” concludes Michael P. Diamond, Chair and Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Georgia.

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Reference

Diamond MP. Outcomes of the NICHD’s comparative effectiveness assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. The NICHD cooperative reproductive medicine network. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):e39. http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2814%2900767-5/fulltext. Accessed October 31, 2014.

When the cause of infertility is unexplained, what is the best first-choice treatment option? Could letrozole, an oral nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, result in fewer multiple gestations than current standard therapy—gonadotropins or selective estrogen receptor modulators (clomiphene citrate)—without worsening the live birth rate?

Researchers from the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) trial investigated this question and presented data at the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Study details

This prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial involved 900 women aged 18 to 40 with at least one patent fallopian tube and regular menses. Patients underwent ovarian stimulation for up to four cycles with an injectable gonadotropin (Gn; n = 300), clomiphene citrate (n = 301), or letrozole (n = 299), followed by intrauterine insemination (IUI).

Birth rate. Conception occurred in 46.8%, 35.7%, and 28.4% of women receiving Gn, clomiphene, and letrozole, respectively, with a live birth occurring in 32.2%, 23.3%, and 18.7% of respective cases. Pregnancy rates with letrozole were significantly less than with Gn (P<.001) and less than with clomiphene (P<.015).

Multiple gestations. The rate of multiple gestations was highest among women treated with Gn (10.3%). But the multiple gestation rate for letrozole was higher than that for clomiphene (2.7% vs 1.3%, respectively). All multiples treated with letrozole and clomiphene were twins; in the Gn group, there were 24 twin and 10 triplet gestations.

No significant difference was found in the rates of infants with congenital anomalies or other fetal or neonatal complications.1

Clomiphene plus IUI remains first-line therapy for unexplained infertility

Although ovarian stimulation with letrozole was safe overall, the number of live births was reduced when treatment with letrozole was compared with clomiphene or Gn, and the multiple pregnancy rate for letrozole fell between clomiphene and Gn.

“CC [clomiphene citrate] /IUI remains first-line therapy for women with unexplained infertility,” concludes Michael P. Diamond, Chair and Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Georgia.

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

When the cause of infertility is unexplained, what is the best first-choice treatment option? Could letrozole, an oral nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, result in fewer multiple gestations than current standard therapy—gonadotropins or selective estrogen receptor modulators (clomiphene citrate)—without worsening the live birth rate?

Researchers from the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) trial investigated this question and presented data at the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Study details

This prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial involved 900 women aged 18 to 40 with at least one patent fallopian tube and regular menses. Patients underwent ovarian stimulation for up to four cycles with an injectable gonadotropin (Gn; n = 300), clomiphene citrate (n = 301), or letrozole (n = 299), followed by intrauterine insemination (IUI).

Birth rate. Conception occurred in 46.8%, 35.7%, and 28.4% of women receiving Gn, clomiphene, and letrozole, respectively, with a live birth occurring in 32.2%, 23.3%, and 18.7% of respective cases. Pregnancy rates with letrozole were significantly less than with Gn (P<.001) and less than with clomiphene (P<.015).

Multiple gestations. The rate of multiple gestations was highest among women treated with Gn (10.3%). But the multiple gestation rate for letrozole was higher than that for clomiphene (2.7% vs 1.3%, respectively). All multiples treated with letrozole and clomiphene were twins; in the Gn group, there were 24 twin and 10 triplet gestations.

No significant difference was found in the rates of infants with congenital anomalies or other fetal or neonatal complications.1

Clomiphene plus IUI remains first-line therapy for unexplained infertility

Although ovarian stimulation with letrozole was safe overall, the number of live births was reduced when treatment with letrozole was compared with clomiphene or Gn, and the multiple pregnancy rate for letrozole fell between clomiphene and Gn.

“CC [clomiphene citrate] /IUI remains first-line therapy for women with unexplained infertility,” concludes Michael P. Diamond, Chair and Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Georgia.

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Reference

Diamond MP. Outcomes of the NICHD’s comparative effectiveness assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. The NICHD cooperative reproductive medicine network. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):e39. http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2814%2900767-5/fulltext. Accessed October 31, 2014.

Reference

Diamond MP. Outcomes of the NICHD’s comparative effectiveness assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. The NICHD cooperative reproductive medicine network. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):e39. http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2814%2900767-5/fulltext. Accessed October 31, 2014.

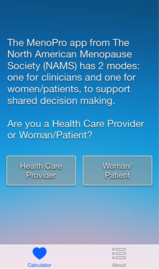

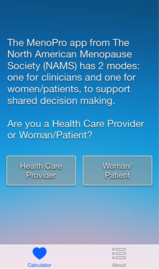

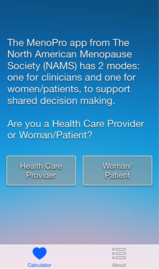

New mobile app assists clinicians in assessing menopausal patients

A new mobile app for iPhone and iPad enables both clinicians and patients to make decisions about menopausal therapies for moderate to severe hot flashes, night sweats, and/or genitourinary symptoms. The app also aids in assessing the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

|

|

|

The MenoPro app, developed in association with the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), is available free of charge from Apple. The app is designed to aid in the assessment and management of bothersome menopausal symptoms in women aged 45 and older.

Designed for both clinician and patient

A novel feature of the app is its two modes—one for the clinician and another for the patient. The clinician mode enables risk assessment and decision-making to determine whether hormonal therapy might be indicated and to determine the formulation and dosage of the therapy selected. It also features assessment of the patient’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease, her risk of breast cancer using the Gail model, and her fracture risk using the FRAX tool. When hormonal therapies are not appropriate, the app steers the clinician to nonhormonal options.

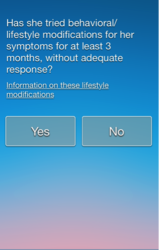

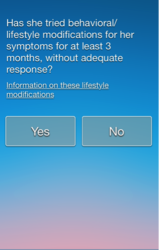

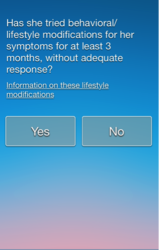

The patient can make use of the app to learn about her different treatment options, including lifestyle modifications. The app guides her through a self-assessment to gauge how far along she is in the menopausal transition, the severity of her symptoms, and her interest in hormonal or nonhormonal therapy. The app begins by recommending lifestyle changes and behavioral factors that can reduce menopausal symptoms. After a 3-month trial of these modifications, the patient is prompted to visit her health-care provider if further relief is needed.

Only FDA-approved drugs are recommended

“The app is completely up to date in terms of information about the newest medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration,” says JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, current chair of the NAMS Scientific Program and a past president of NAMS. Dr. Manson is Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School.

“The app focuses on FDA-approved medications, including off-label use of medications that may be commonly prescribed in practice to treat hot flashes, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),” she says.

“I think another big advantage is that very often clinicians who are managing patients during the menopausal transition or in early menopause may not be thinking that much about cardiovascular risk or even know how to evaluate it or make use of a 10-year risk score. So the app really helps them to become very familiar with the evaluation of cardiovascular risk, breast cancer risk, and fracture risk, and provides them with the resources to make use of the information.”

An algorithm is available within the app

The app is based on an algorithm that can be accessed within the app by choosing the “About” button. Another feature: the clinician can email a summary of the patient’s assessment directly to her, along with links to resources on a variety of relevant topics.

“In the future, there is a plan to have the app available for other mobile phones and tablet devices in addition to the iPhone and iPad,” says Dr. Manson. “We also hope to have it incorporated into electronic health records, where it could be used for clinical decision-making within the record.”

The app is not intended to replace clinical judgment, she adds. “I think clinicians are really familiar with the concept that, when you’re using an app, clinical judgment remains paramount. The app is not going to replace the clinician’s own discernment of what is going on with the patient.”

For detailed information, see an article on the app in the journal Menopause, available at http://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/professional/our-new-paper.pdf

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A new mobile app for iPhone and iPad enables both clinicians and patients to make decisions about menopausal therapies for moderate to severe hot flashes, night sweats, and/or genitourinary symptoms. The app also aids in assessing the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

|

|

|

The MenoPro app, developed in association with the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), is available free of charge from Apple. The app is designed to aid in the assessment and management of bothersome menopausal symptoms in women aged 45 and older.

Designed for both clinician and patient

A novel feature of the app is its two modes—one for the clinician and another for the patient. The clinician mode enables risk assessment and decision-making to determine whether hormonal therapy might be indicated and to determine the formulation and dosage of the therapy selected. It also features assessment of the patient’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease, her risk of breast cancer using the Gail model, and her fracture risk using the FRAX tool. When hormonal therapies are not appropriate, the app steers the clinician to nonhormonal options.

The patient can make use of the app to learn about her different treatment options, including lifestyle modifications. The app guides her through a self-assessment to gauge how far along she is in the menopausal transition, the severity of her symptoms, and her interest in hormonal or nonhormonal therapy. The app begins by recommending lifestyle changes and behavioral factors that can reduce menopausal symptoms. After a 3-month trial of these modifications, the patient is prompted to visit her health-care provider if further relief is needed.

Only FDA-approved drugs are recommended

“The app is completely up to date in terms of information about the newest medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration,” says JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, current chair of the NAMS Scientific Program and a past president of NAMS. Dr. Manson is Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School.

“The app focuses on FDA-approved medications, including off-label use of medications that may be commonly prescribed in practice to treat hot flashes, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),” she says.

“I think another big advantage is that very often clinicians who are managing patients during the menopausal transition or in early menopause may not be thinking that much about cardiovascular risk or even know how to evaluate it or make use of a 10-year risk score. So the app really helps them to become very familiar with the evaluation of cardiovascular risk, breast cancer risk, and fracture risk, and provides them with the resources to make use of the information.”

An algorithm is available within the app

The app is based on an algorithm that can be accessed within the app by choosing the “About” button. Another feature: the clinician can email a summary of the patient’s assessment directly to her, along with links to resources on a variety of relevant topics.

“In the future, there is a plan to have the app available for other mobile phones and tablet devices in addition to the iPhone and iPad,” says Dr. Manson. “We also hope to have it incorporated into electronic health records, where it could be used for clinical decision-making within the record.”

The app is not intended to replace clinical judgment, she adds. “I think clinicians are really familiar with the concept that, when you’re using an app, clinical judgment remains paramount. The app is not going to replace the clinician’s own discernment of what is going on with the patient.”

For detailed information, see an article on the app in the journal Menopause, available at http://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/professional/our-new-paper.pdf

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A new mobile app for iPhone and iPad enables both clinicians and patients to make decisions about menopausal therapies for moderate to severe hot flashes, night sweats, and/or genitourinary symptoms. The app also aids in assessing the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and fracture.

|

|

|

The MenoPro app, developed in association with the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), is available free of charge from Apple. The app is designed to aid in the assessment and management of bothersome menopausal symptoms in women aged 45 and older.

Designed for both clinician and patient

A novel feature of the app is its two modes—one for the clinician and another for the patient. The clinician mode enables risk assessment and decision-making to determine whether hormonal therapy might be indicated and to determine the formulation and dosage of the therapy selected. It also features assessment of the patient’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease, her risk of breast cancer using the Gail model, and her fracture risk using the FRAX tool. When hormonal therapies are not appropriate, the app steers the clinician to nonhormonal options.

The patient can make use of the app to learn about her different treatment options, including lifestyle modifications. The app guides her through a self-assessment to gauge how far along she is in the menopausal transition, the severity of her symptoms, and her interest in hormonal or nonhormonal therapy. The app begins by recommending lifestyle changes and behavioral factors that can reduce menopausal symptoms. After a 3-month trial of these modifications, the patient is prompted to visit her health-care provider if further relief is needed.

Only FDA-approved drugs are recommended

“The app is completely up to date in terms of information about the newest medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration,” says JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, current chair of the NAMS Scientific Program and a past president of NAMS. Dr. Manson is Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She also is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School.

“The app focuses on FDA-approved medications, including off-label use of medications that may be commonly prescribed in practice to treat hot flashes, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),” she says.

“I think another big advantage is that very often clinicians who are managing patients during the menopausal transition or in early menopause may not be thinking that much about cardiovascular risk or even know how to evaluate it or make use of a 10-year risk score. So the app really helps them to become very familiar with the evaluation of cardiovascular risk, breast cancer risk, and fracture risk, and provides them with the resources to make use of the information.”

An algorithm is available within the app

The app is based on an algorithm that can be accessed within the app by choosing the “About” button. Another feature: the clinician can email a summary of the patient’s assessment directly to her, along with links to resources on a variety of relevant topics.

“In the future, there is a plan to have the app available for other mobile phones and tablet devices in addition to the iPhone and iPad,” says Dr. Manson. “We also hope to have it incorporated into electronic health records, where it could be used for clinical decision-making within the record.”

The app is not intended to replace clinical judgment, she adds. “I think clinicians are really familiar with the concept that, when you’re using an app, clinical judgment remains paramount. The app is not going to replace the clinician’s own discernment of what is going on with the patient.”

For detailed information, see an article on the app in the journal Menopause, available at http://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/professional/our-new-paper.pdf

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Ebola: Essential facts for ObGyns

As Ebola virus spreads from West Africa, it has become apparent that ObGyns in the United States may need to evaluate patients who have been exposed to the disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a dedicated Web site for Ebola that outlines signs and symptoms, transmission, risk of exposure, diagnosis and treatment options, and clinical guidance for health-care workers.1

What are the symptoms of Ebola?

If a woman from West Africa presents with a fever, the CDC advises that she be asked specifically about recent travel to affected areas (currently Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria). Clinical signs and symptoms of Ebola include a fever of 38.6°C [101.5°F] or higher with additional symptoms1:

- severe headache

- muscle pain

- weakness

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- abdominal (stomach) pain

- unexplained hemorrhage.

Symptoms may appear from 2–21 days after exposure to Ebola. If a person with early symptoms of Ebola has had contact with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola, objects contaminated with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola, or with Ebola-infected animals, the patient should be isolated and public health professionals immediately notified, says the CDC. Blood samples from the patient should be tested to confirm infection (visit the CDC’s Ebola Web site for a list of diagnostic tests).1

More women than men infected

In a recently published perspective from the CDC on what ObGyns should be aware of regarding Ebola, Jamieson and colleagues reported that, according to UNICEF data, in this current outbreak more women than men are infected.2 They say this is most likely because women in West Africa are the primary caregivers for sick relatives, as well as make up the majority of health-care providers and birth attendants.

Pregnancy and Ebola

Based on limited, historic data from other Ebola outbreaks in Africa, there is no evidence suggesting that pregnant women are more susceptible to Ebola, although say Jamieson and colleagues, there is limited evidence suggesting that pregnant women are more at risk for severe illness and death from Ebola.2 It also appears that pregnant women with Ebola are at increased risk for spontaneous abortion and pregnancy-related hemorrhage. In 1996 in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, pregnant women were more likely than the overall patient population with Ebola to have hemorrhagic complications, specifically vaginal and uterine bleeding associated with abortion or delivery. Children born to mothers with Ebola have not survived, though the cause of death has not been identified specifically.2

Breastfeeding and Ebola

The CDC has issued recommendations for breastfeeding or infant feeding by women with suspected or confirmed exposure to Ebola. Two key points are made3:

- Mothers with probable or confirmed Ebola virus disease should not have close contact with their infants when safe alternatives to breastfeeding and infant care exist

- Where resources are limited, non−breastfed infants are at increased risk of death from starvation and other infectious diseases. These risks must be carefully weighed against the risk of Ebola virus disease.

CDC recommends that decisions about how to best feed an infant whose mother has probable or confirmed Ebola be made on a case-by-case basis, balancing nutritional needs with the risk of contracting the disease. There is not enough evidence to suggest when it is safe to resume breastfeeding after a mother’s recovery, unless her breast milk can be shown to be Ebola-free.3

Protecting health-care personnel

The CDC Ebola Web site1 provides specific protocols designed to keep health-care workers safe. These include detailed guidelines for evaluating returned travelers, instructions for specimen collection, transport, testing, submission, use of protective equipment, and isolation procedures.

Share your thoughts on this news! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name, and the city and state in which you practice

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease). http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/. Updated October 5, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- Jamieson DJ, Uyeko TM, Callaghan WM, Meaney-Delman D, Rasmussen SA. What obstetrician-gynecologists should know about Ebola: A perspective from the Centers from Disease Control and Prevention [published online ahead of print September 8, 2014]. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/publishahead/What_Obstetrician_Gynecologists_Should_Know_About.99324.aspx. Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000533.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for breastfeeding/infant feeding in the context of Ebola. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/recommendations-breastfeeding-infant-feeding-ebola.html. Updated September 19, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014.

As Ebola virus spreads from West Africa, it has become apparent that ObGyns in the United States may need to evaluate patients who have been exposed to the disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a dedicated Web site for Ebola that outlines signs and symptoms, transmission, risk of exposure, diagnosis and treatment options, and clinical guidance for health-care workers.1

What are the symptoms of Ebola?

If a woman from West Africa presents with a fever, the CDC advises that she be asked specifically about recent travel to affected areas (currently Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria). Clinical signs and symptoms of Ebola include a fever of 38.6°C [101.5°F] or higher with additional symptoms1:

- severe headache

- muscle pain

- weakness

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- abdominal (stomach) pain

- unexplained hemorrhage.

Symptoms may appear from 2–21 days after exposure to Ebola. If a person with early symptoms of Ebola has had contact with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola, objects contaminated with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola, or with Ebola-infected animals, the patient should be isolated and public health professionals immediately notified, says the CDC. Blood samples from the patient should be tested to confirm infection (visit the CDC’s Ebola Web site for a list of diagnostic tests).1

More women than men infected

In a recently published perspective from the CDC on what ObGyns should be aware of regarding Ebola, Jamieson and colleagues reported that, according to UNICEF data, in this current outbreak more women than men are infected.2 They say this is most likely because women in West Africa are the primary caregivers for sick relatives, as well as make up the majority of health-care providers and birth attendants.

Pregnancy and Ebola

Based on limited, historic data from other Ebola outbreaks in Africa, there is no evidence suggesting that pregnant women are more susceptible to Ebola, although say Jamieson and colleagues, there is limited evidence suggesting that pregnant women are more at risk for severe illness and death from Ebola.2 It also appears that pregnant women with Ebola are at increased risk for spontaneous abortion and pregnancy-related hemorrhage. In 1996 in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, pregnant women were more likely than the overall patient population with Ebola to have hemorrhagic complications, specifically vaginal and uterine bleeding associated with abortion or delivery. Children born to mothers with Ebola have not survived, though the cause of death has not been identified specifically.2

Breastfeeding and Ebola

The CDC has issued recommendations for breastfeeding or infant feeding by women with suspected or confirmed exposure to Ebola. Two key points are made3:

- Mothers with probable or confirmed Ebola virus disease should not have close contact with their infants when safe alternatives to breastfeeding and infant care exist

- Where resources are limited, non−breastfed infants are at increased risk of death from starvation and other infectious diseases. These risks must be carefully weighed against the risk of Ebola virus disease.

CDC recommends that decisions about how to best feed an infant whose mother has probable or confirmed Ebola be made on a case-by-case basis, balancing nutritional needs with the risk of contracting the disease. There is not enough evidence to suggest when it is safe to resume breastfeeding after a mother’s recovery, unless her breast milk can be shown to be Ebola-free.3

Protecting health-care personnel

The CDC Ebola Web site1 provides specific protocols designed to keep health-care workers safe. These include detailed guidelines for evaluating returned travelers, instructions for specimen collection, transport, testing, submission, use of protective equipment, and isolation procedures.

Share your thoughts on this news! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name, and the city and state in which you practice

As Ebola virus spreads from West Africa, it has become apparent that ObGyns in the United States may need to evaluate patients who have been exposed to the disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a dedicated Web site for Ebola that outlines signs and symptoms, transmission, risk of exposure, diagnosis and treatment options, and clinical guidance for health-care workers.1

What are the symptoms of Ebola?

If a woman from West Africa presents with a fever, the CDC advises that she be asked specifically about recent travel to affected areas (currently Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria). Clinical signs and symptoms of Ebola include a fever of 38.6°C [101.5°F] or higher with additional symptoms1:

- severe headache

- muscle pain

- weakness

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- abdominal (stomach) pain

- unexplained hemorrhage.

Symptoms may appear from 2–21 days after exposure to Ebola. If a person with early symptoms of Ebola has had contact with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola, objects contaminated with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola, or with Ebola-infected animals, the patient should be isolated and public health professionals immediately notified, says the CDC. Blood samples from the patient should be tested to confirm infection (visit the CDC’s Ebola Web site for a list of diagnostic tests).1

More women than men infected

In a recently published perspective from the CDC on what ObGyns should be aware of regarding Ebola, Jamieson and colleagues reported that, according to UNICEF data, in this current outbreak more women than men are infected.2 They say this is most likely because women in West Africa are the primary caregivers for sick relatives, as well as make up the majority of health-care providers and birth attendants.

Pregnancy and Ebola

Based on limited, historic data from other Ebola outbreaks in Africa, there is no evidence suggesting that pregnant women are more susceptible to Ebola, although say Jamieson and colleagues, there is limited evidence suggesting that pregnant women are more at risk for severe illness and death from Ebola.2 It also appears that pregnant women with Ebola are at increased risk for spontaneous abortion and pregnancy-related hemorrhage. In 1996 in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, pregnant women were more likely than the overall patient population with Ebola to have hemorrhagic complications, specifically vaginal and uterine bleeding associated with abortion or delivery. Children born to mothers with Ebola have not survived, though the cause of death has not been identified specifically.2

Breastfeeding and Ebola

The CDC has issued recommendations for breastfeeding or infant feeding by women with suspected or confirmed exposure to Ebola. Two key points are made3:

- Mothers with probable or confirmed Ebola virus disease should not have close contact with their infants when safe alternatives to breastfeeding and infant care exist

- Where resources are limited, non−breastfed infants are at increased risk of death from starvation and other infectious diseases. These risks must be carefully weighed against the risk of Ebola virus disease.

CDC recommends that decisions about how to best feed an infant whose mother has probable or confirmed Ebola be made on a case-by-case basis, balancing nutritional needs with the risk of contracting the disease. There is not enough evidence to suggest when it is safe to resume breastfeeding after a mother’s recovery, unless her breast milk can be shown to be Ebola-free.3

Protecting health-care personnel

The CDC Ebola Web site1 provides specific protocols designed to keep health-care workers safe. These include detailed guidelines for evaluating returned travelers, instructions for specimen collection, transport, testing, submission, use of protective equipment, and isolation procedures.

Share your thoughts on this news! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name, and the city and state in which you practice

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease). http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/. Updated October 5, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- Jamieson DJ, Uyeko TM, Callaghan WM, Meaney-Delman D, Rasmussen SA. What obstetrician-gynecologists should know about Ebola: A perspective from the Centers from Disease Control and Prevention [published online ahead of print September 8, 2014]. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/publishahead/What_Obstetrician_Gynecologists_Should_Know_About.99324.aspx. Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000533.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for breastfeeding/infant feeding in the context of Ebola. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/recommendations-breastfeeding-infant-feeding-ebola.html. Updated September 19, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease). http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/. Updated October 5, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- Jamieson DJ, Uyeko TM, Callaghan WM, Meaney-Delman D, Rasmussen SA. What obstetrician-gynecologists should know about Ebola: A perspective from the Centers from Disease Control and Prevention [published online ahead of print September 8, 2014]. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/publishahead/What_Obstetrician_Gynecologists_Should_Know_About.99324.aspx. Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000533.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for breastfeeding/infant feeding in the context of Ebola. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/recommendations-breastfeeding-infant-feeding-ebola.html. Updated September 19, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014.

Dutch study clarifies risk of attempted vaginal birth of breech fetus

Should a baby that presents breech at term be delivered vaginally or by cesarean delivery? In October 2000, results of the Term Breech Trial (TBT), the largest randomized controlled trial to investigate the effect of delivery mode for term breech deliveries on neonatal and maternal outcomes, essentially answered this question, showing that planned cesarean delivery was safer than planned vaginal delivery (with combined perinatal morbidity and mortality scores of 5% vs 16%, respectively).1 These study results affected national guidelines for choosing delivery mode in the Netherlands as well as other countries around the world.

What has been the impact on mode of delivery and neonatal outcome in the Netherlands since the TBT’s publication? Furthermore, are there antepartum parameters that can distinguish which women are at high risk versus low risk for adverse neonatal outcomes when presenting breech at delivery? Vlemmix and colleagues sought to answer these questions, using retrospective data from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry (PRN) from 1999 through 2007.1

Perinatal death decreased over time—but only for women electing cesarean

During the study period, approximately 4% of all births were breech. The researchers studied 58,320 women with term breech delivery, using the PRN. They noted an increase in the elective cesarean delivery (ECD) rate for these women, from 24% before October 2000 to 60% after December 2000, and as a consequence, found that overall perinatal mortality decreased from 1.3% to 0.7% (odds ratio [OR] 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.28–0.93).1

However, among the women who underwent planned vaginal delivery, the overall perinatal mortality remained stable (1.7% vs 1.6%; OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.52–1.76). “Despite the lower percentage of women opting for or offered a vaginal delivery, and despite a higher emergency cesarean rate during vaginal breech birth, neonatal outcome within the planned vaginal birth group did not improve,” state the authors.1

Putting the results in absolute numbers

The investigators say that the 40% of Dutch women with breech presentation at term who still attempt vaginal birth do so without improved neonatal outcome; these deliveries generate a 10-fold higher fetal mortality rate compared with ECD. Further, no subgroup of women, when evaluating parity, onset of labor, type of breech presentation, and birthweight, could be identified with a low risk of poor neonatal outcome during planned vaginal delivery compared with ECD.1

Since the TBT, 1,692 more combined elective and emergency cesarean deliveries were performed annually, leading to five less neonatal deaths per year (number needed to treat, 338). If all women who still undergo planned vaginal birth receive ECD, 6,490 more ECDs would be performed, with 10 less neonatal deaths, 116 less neonates with low Apgar score, and 20 less neonates with birth trauma per year, according to the researchers.1

They suggest that clinicians use the results of this study when counseling women with a term breech presentation on mode of delivery. “To properly inform patients, a combination of risk presentation (absolute risks, relative risks and figures) is necessary to enable individual informed decision making.”1

Share your thoughts on this news! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name, and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference