User login

Don’t lose your access to essential resources

If you are a current AGA trainee, medical resident, or student member, please renew your membership today to ensure the continuation of your career-enhancing benefits for the upcoming membership year. Prepare for your next chapter with the latest news and breakthroughs in the field, as well as access to educational programs, events and much more.

While renewing, please update your member profile at My AGA for news and resources tailored to your professional interests. The deadline to renew is Aug. 31, 2018.

If you have any questions, please contact AGA Member Relations at [email protected] or 301-941-2651.

If you are a current AGA trainee, medical resident, or student member, please renew your membership today to ensure the continuation of your career-enhancing benefits for the upcoming membership year. Prepare for your next chapter with the latest news and breakthroughs in the field, as well as access to educational programs, events and much more.

While renewing, please update your member profile at My AGA for news and resources tailored to your professional interests. The deadline to renew is Aug. 31, 2018.

If you have any questions, please contact AGA Member Relations at [email protected] or 301-941-2651.

If you are a current AGA trainee, medical resident, or student member, please renew your membership today to ensure the continuation of your career-enhancing benefits for the upcoming membership year. Prepare for your next chapter with the latest news and breakthroughs in the field, as well as access to educational programs, events and much more.

While renewing, please update your member profile at My AGA for news and resources tailored to your professional interests. The deadline to renew is Aug. 31, 2018.

If you have any questions, please contact AGA Member Relations at [email protected] or 301-941-2651.

A successful career starts with taking charge

Successful careers don’t just happen. They are made by individuals who take charge and build their own success. The alternative is burnout.

“Part of burnout is feeling overburdened, overworked, and out of control,” said Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, professor and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, during Strategies for a Successful Career: Wellness, Empowerment, Leadership and Resilience at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2018. “If somebody is staying until 9 or 10 o’clock [at night] to finish notes, I have a discussion with them. It is good to be done at 5 p.m. and go home. It is all about setting your own priorities and not letting the job take over your life.”

Associations have a role to play, too. The ASGE Technology Committee reported in 2010 that up to 89% of GIs suffer musculoskeletal injuries from manipulating scopes. Colonoscopist’s thumb (left thumb tendonitis) and metacarpophalangeal joint strain were the most common injuries.

“Risk factors are part of our work,” said Mehnaz Shafi, MD, AGAF, professor of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Pinching, pushing, pulling, and awkward positions are part of what we do. This is an injury with consequences.”

Dr. Shafi chairs the AGA Task Force on Ergonomics. The group has recommended changes to endoscopic work stations that minimize injury. The most important changes include mounting monitors on flexible stands to accommodate GIs of all heights, adding straps to the control head to allow the fingers to relax, providing ergonomic training to all GIs and using patient beds that can be raised and lowered to accommodate both tall and short GIs.

“Shaping your career is one of the key principles in preventing burnout,” said Arthur DeCross, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Rochester Medical Center, N.Y. “We know that more than half of gastroenterologists self-identify as being burned out. And one of the major contributors to burnout is lack of control over your work environment, your career, your colleagues. Taking control of your career can make a difference.”

Taking control can be particularly important for women. An AGA burnout survey in 2015 found that 51% of male GIs reported burnout versus 62% of female GIs.

One reason is women’s tendency to negotiate poorly on their own behalf, said Marie-Pier Tétreault, PhD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

“It’s a matter of attitude,” she explained. “Men tend to believe they can and should make life happen. Women tend to believe that what you see is what you get. Even when women do negotiate, they tend to ask for 15%-30% less than their male colleagues. If you don’t ask, you won’t get.”

Simply taking the lead in negotiations can improve the outcome, she continued. Network with colleagues and mentors to find the appropriate ranges for salaries, benefits, and perks such as parking, spousal job opportunities, facilities and space, teaching expectations, administrative support, and more.

Successful careers don’t just happen. They are made by individuals who take charge and build their own success. The alternative is burnout.

“Part of burnout is feeling overburdened, overworked, and out of control,” said Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, professor and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, during Strategies for a Successful Career: Wellness, Empowerment, Leadership and Resilience at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2018. “If somebody is staying until 9 or 10 o’clock [at night] to finish notes, I have a discussion with them. It is good to be done at 5 p.m. and go home. It is all about setting your own priorities and not letting the job take over your life.”

Associations have a role to play, too. The ASGE Technology Committee reported in 2010 that up to 89% of GIs suffer musculoskeletal injuries from manipulating scopes. Colonoscopist’s thumb (left thumb tendonitis) and metacarpophalangeal joint strain were the most common injuries.

“Risk factors are part of our work,” said Mehnaz Shafi, MD, AGAF, professor of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Pinching, pushing, pulling, and awkward positions are part of what we do. This is an injury with consequences.”

Dr. Shafi chairs the AGA Task Force on Ergonomics. The group has recommended changes to endoscopic work stations that minimize injury. The most important changes include mounting monitors on flexible stands to accommodate GIs of all heights, adding straps to the control head to allow the fingers to relax, providing ergonomic training to all GIs and using patient beds that can be raised and lowered to accommodate both tall and short GIs.

“Shaping your career is one of the key principles in preventing burnout,” said Arthur DeCross, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Rochester Medical Center, N.Y. “We know that more than half of gastroenterologists self-identify as being burned out. And one of the major contributors to burnout is lack of control over your work environment, your career, your colleagues. Taking control of your career can make a difference.”

Taking control can be particularly important for women. An AGA burnout survey in 2015 found that 51% of male GIs reported burnout versus 62% of female GIs.

One reason is women’s tendency to negotiate poorly on their own behalf, said Marie-Pier Tétreault, PhD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

“It’s a matter of attitude,” she explained. “Men tend to believe they can and should make life happen. Women tend to believe that what you see is what you get. Even when women do negotiate, they tend to ask for 15%-30% less than their male colleagues. If you don’t ask, you won’t get.”

Simply taking the lead in negotiations can improve the outcome, she continued. Network with colleagues and mentors to find the appropriate ranges for salaries, benefits, and perks such as parking, spousal job opportunities, facilities and space, teaching expectations, administrative support, and more.

Successful careers don’t just happen. They are made by individuals who take charge and build their own success. The alternative is burnout.

“Part of burnout is feeling overburdened, overworked, and out of control,” said Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, professor and chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, during Strategies for a Successful Career: Wellness, Empowerment, Leadership and Resilience at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2018. “If somebody is staying until 9 or 10 o’clock [at night] to finish notes, I have a discussion with them. It is good to be done at 5 p.m. and go home. It is all about setting your own priorities and not letting the job take over your life.”

Associations have a role to play, too. The ASGE Technology Committee reported in 2010 that up to 89% of GIs suffer musculoskeletal injuries from manipulating scopes. Colonoscopist’s thumb (left thumb tendonitis) and metacarpophalangeal joint strain were the most common injuries.

“Risk factors are part of our work,” said Mehnaz Shafi, MD, AGAF, professor of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Pinching, pushing, pulling, and awkward positions are part of what we do. This is an injury with consequences.”

Dr. Shafi chairs the AGA Task Force on Ergonomics. The group has recommended changes to endoscopic work stations that minimize injury. The most important changes include mounting monitors on flexible stands to accommodate GIs of all heights, adding straps to the control head to allow the fingers to relax, providing ergonomic training to all GIs and using patient beds that can be raised and lowered to accommodate both tall and short GIs.

“Shaping your career is one of the key principles in preventing burnout,” said Arthur DeCross, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Rochester Medical Center, N.Y. “We know that more than half of gastroenterologists self-identify as being burned out. And one of the major contributors to burnout is lack of control over your work environment, your career, your colleagues. Taking control of your career can make a difference.”

Taking control can be particularly important for women. An AGA burnout survey in 2015 found that 51% of male GIs reported burnout versus 62% of female GIs.

One reason is women’s tendency to negotiate poorly on their own behalf, said Marie-Pier Tétreault, PhD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

“It’s a matter of attitude,” she explained. “Men tend to believe they can and should make life happen. Women tend to believe that what you see is what you get. Even when women do negotiate, they tend to ask for 15%-30% less than their male colleagues. If you don’t ask, you won’t get.”

Simply taking the lead in negotiations can improve the outcome, she continued. Network with colleagues and mentors to find the appropriate ranges for salaries, benefits, and perks such as parking, spousal job opportunities, facilities and space, teaching expectations, administrative support, and more.

August 2018

Gastroenterology

How to maximize learning in a gastroenterology fellow clinic: Prepare to precept. Kumar NL; Perencevich ML. 2018 Jul;155(1):8-10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.022.

Management of patients with functional heartburn. Lee YY; Wu JCY. 2018 Jun;154(8):2018-21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.030.

Skills acquired during my 1-year AGA editorial fellowship. Shah ED. 2018 May;154(6):1563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.043.

How to incorporate quality improvement and patient safety projects in your training. Siddique SM et al. 2018 May;154(6):1564-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.044.

Clin Gastro Hepatol.

Training the endo-thlete: An update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Singla M et al. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.019.

Workup and management of bloating. Kamboj AK; Oxentenko AS. 2018 Jul;16(7):1030-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.046.

Hiatal and paraesophageal hernias. Callaway JP, Vaezi MF. 2018 Jun;16(6):810-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.045.

CMGH

A sabbatical: The gift that keeps on giving. Friedman SL. 2018;5(4):656-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.01.010.

Gastroenterology

How to maximize learning in a gastroenterology fellow clinic: Prepare to precept. Kumar NL; Perencevich ML. 2018 Jul;155(1):8-10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.022.

Management of patients with functional heartburn. Lee YY; Wu JCY. 2018 Jun;154(8):2018-21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.030.

Skills acquired during my 1-year AGA editorial fellowship. Shah ED. 2018 May;154(6):1563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.043.

How to incorporate quality improvement and patient safety projects in your training. Siddique SM et al. 2018 May;154(6):1564-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.044.

Clin Gastro Hepatol.

Training the endo-thlete: An update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Singla M et al. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.019.

Workup and management of bloating. Kamboj AK; Oxentenko AS. 2018 Jul;16(7):1030-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.046.

Hiatal and paraesophageal hernias. Callaway JP, Vaezi MF. 2018 Jun;16(6):810-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.045.

CMGH

A sabbatical: The gift that keeps on giving. Friedman SL. 2018;5(4):656-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.01.010.

Gastroenterology

How to maximize learning in a gastroenterology fellow clinic: Prepare to precept. Kumar NL; Perencevich ML. 2018 Jul;155(1):8-10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.022.

Management of patients with functional heartburn. Lee YY; Wu JCY. 2018 Jun;154(8):2018-21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.030.

Skills acquired during my 1-year AGA editorial fellowship. Shah ED. 2018 May;154(6):1563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.043.

How to incorporate quality improvement and patient safety projects in your training. Siddique SM et al. 2018 May;154(6):1564-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.044.

Clin Gastro Hepatol.

Training the endo-thlete: An update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Singla M et al. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.019.

Workup and management of bloating. Kamboj AK; Oxentenko AS. 2018 Jul;16(7):1030-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.046.

Hiatal and paraesophageal hernias. Callaway JP, Vaezi MF. 2018 Jun;16(6):810-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.045.

CMGH

A sabbatical: The gift that keeps on giving. Friedman SL. 2018;5(4):656-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.01.010.

Negotiating physician employment agreements

You have finally completed your residency or fellowship, and now you have a job offer. With some trepidation, you decide to read the employment agreement that has been emailed to you. You quickly realize that you do not understand much of it. All those legal terms! You lament the fact that medical school never taught you about the business of medicine. What are you going to do? The choices are actually quite simple: You can take the time to educate yourself or you can hire an expert. This article will review some of the basic principles of negotiating as well as some of the critical issues found in physician employment agreements today.

Whether you represent yourself or hire someone to do it for you, it is important to understand some of the basic principles of negotiating. These principles generally are applicable whether you are buying a house or negotiating your employment agreement.

Negotiations

The most important principle is preparation. For example, many physicians negotiate their salaries during the interview process. Consequently, it is imperative that, before you negotiate your compensation, you know the range of salaries in your area for your specialty. It is also important to know whether salaries are usually guaranteed in your market, or whether production-based salaries (which are based on the amount of your billings) are the norm. Never go into an interview unprepared!

Always try to gain leverage in your negotiations. The easiest way to accomplish this is by having multiple offers, and subtly letting your suitors know this. Allow adequate time to negotiate; the more time you have, the easier it is to negotiate. Establish your objectives and try to anticipate the objectives of the other party. Determine your best-case and worse-case scenarios, as well as the most likely outcome. Do not negotiate against yourself and try to get something every time you give something. Define the nonnegotiable issues, and do not waste time on them. Keep cool and be flexible.

The first question you must answer when you receive an employment agreement is who is going to negotiate it. Many new physicians hire attorneys to help them with their employment agreements and employers expect as much. It is best to engage an attorney before you begin your job search so you can get a better understanding of how the attorney can help you. Most attorneys do not charge a prospective client for such information. However, many physicians wait until they actually receive an offer before contacting an attorney. It is not uncommon for physicians to negotiate their salaries during job interviews even if they eventually hire an attorney to help them. This is usually attributable to a lack of negotiating experience and an eagerness to determine whether a job offer is viable. Keep in mind that an attorney often can negotiate a better starting salary than you, so try to resist the temptation to negotiate your salary during the interview process.

Compensation

With compensation in mind, what are some of the important issues? Today, many physician employers are converting to production-based compensation models. Consequently, it is important for new physicians to obtain guaranteed base salaries during their first few years of employment while they are building their practices.

On occasion, new physicians initially are offered production-based compensation models, which also allocate a share of practice overhead expenses to them. This is a very dangerous compensation model for a new physician. Under such a model, it is possible that a new physician could have a negative balance in his/her cost center at the end of the year, and actually owe his/her employer money.

Some physicians may be offered income guarantees by hospitals. There are several different types of income guarantees but they are frequently categorized together even though they differ significantly. The most common income guarantees offered to physicians are physician recruitment agreements (PRAs). Under a PRA, a hospital usually guarantees that a physician who relocates to the service area of the hospital collects a minimum amount of monthly revenue for 1-2 years, which is known as the guarantee period. The hospital also guarantees to pay certain monthly expenses of the physician during the guarantee period. This arrangement is actually structured as a loan by the hospital to the physician, and requires the physician to execute a promissory note with the hospital for the amounts advanced to the physician by the hospital. The promissory note is forgiven if the physician continues to practice in the service area for 2-3 years after the guarantee period. This type of guarantee provides an excellent opportunity for a new physician to establish a solo practice. A variation of this model involves a third party such as a medical group. Under this model, the hospital continues to guarantee the revenue of the new physician and pays the medical group the expenses it incurs as a result of hiring the new physician. These expenses are known as incremental practice expenses. The medical group also becomes a signatory to the promissory note. Other health care entities also have begun to offer PRAs to physicians. For example, an independent practice association in California recently entered into a PRA with a gastroenterologist.

Keep in mind that the promissory note executed by the physician may affect the credit of the physician, especially if he/she wants to obtain financing for a home purchase. Also, a hospital may seek security for the performance of the promissory note by collateralizing the personal assets of the physician instead of just his/her practice assets; this should be avoided.

The other type of income guarantee is provided to hospital-based physicians such as pathologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, etc. Under this type of guarantee, a hospital ensures that the physicians receive a minimum threshold of collections. This type of guarantee may be necessary to attract hospital-based physicians to a hospital which has a low-income and/or Medicaid population. This is not a typical scenario for a gastroenterologist.

Some practices create incentives for physicians by offering a variety of bonuses. Most often these bonuses are production based but sometimes they are based on such quality issues as patient satisfaction. The most common types of production bonuses are based on attaining a level of collections above a dollar threshold or exceeding a minimum level of relative value units (RVUs).

To summarize, new physicians should always try to get at least a 2-year income guarantee. They should never allow an employer to allocate overhead to them during the first 2 years of employment. In addition, they should always try to negotiate realistic production-based bonuses.

Benefits

Fringe benefits are an integral part of a compensation package for a new physician. Most physician employers offer a generous package of health insurance, retirement, reimbursable expenses, and paid time off. These benefits should be clearly delineated in the employment agreement or employee handbook. A very common question about health benefits is when they become effective (the first day of employment, 30 days after employment, the first of the month after employment, etc.). This is significant because Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) is quite expensive. Another issue is whether health insurance also will cover the physician’s spouse and dependents. Most physician employers cover only the physician, not his/her spouse and dependents. If a new physician has a spouse who already provides family health benefits, it may behoove the physician to negotiate an allowance in lieu of health benefits.

Paid time off of 10-20 days are commonly given by physician employers to new physicians. Some employers also provide 5 or more additional days of paid time off for Continuing Medical Education (CME). Of course, once a physician goes onto production-based compensation, paid time off usually is not provided.

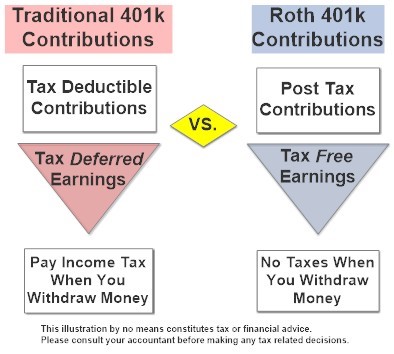

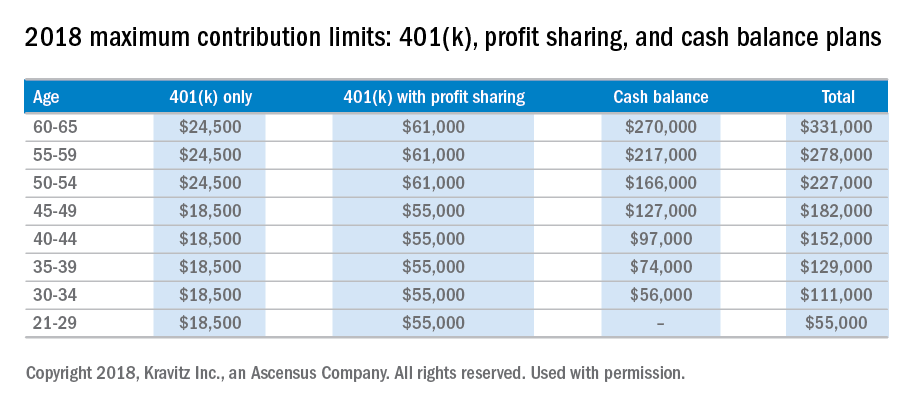

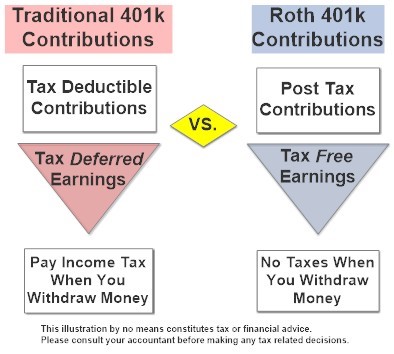

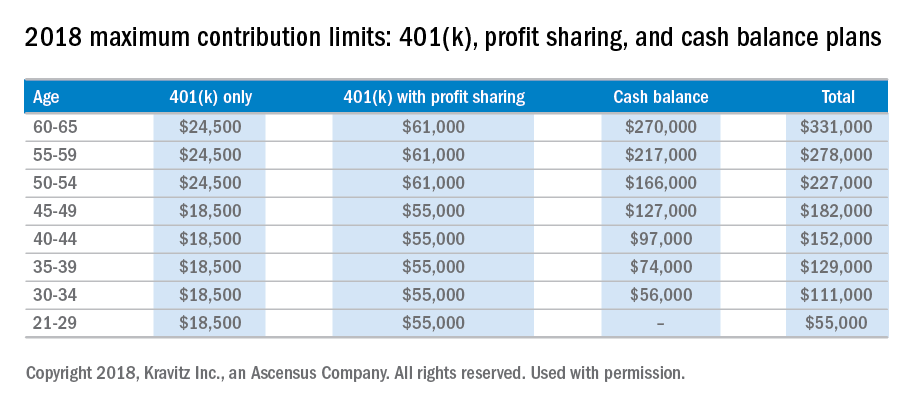

It is very important that a physician employer offer a retirement plan. Oftentimes, there is a matching contribution by the employer. However, it is not uncommon for there to be a year waiting period for eligibility in the retirement plan. Retirement plans vary significantly so it is advisable for a new physician to meet with the employer’s human resources department to get the details of the plan offered; the physician may want to confer with a financial advisor after obtaining this information.

Most physician employers reimburse licensing and DEA fees, medical staff dues, and board certification expenses. There is often a CME allowance as well. In competitive markets, some physician employers also offer innovative benefits such as student loan repayment programs, fellowship and residency stipends, and forgivable loans for housing. Sometimes these benefits are not included in the employment agreement; you may have to ask for them.

Indemnification/noncompetition

In addition to compensation and benefits, there are several other issues which are commonly found in employment agreements. Perhaps the most controversial is the issue of indemnification. The legal concept of indemnity allows a physician employer to recover damages and defense costs from a physician employee in certain circumstances. For example, if a physician employer has a $1,000,000/$3,000,000 malpractice policy covering itself and each of its physician employees, and if a physician commits malpractice and the award is $2,000,000, the employer may seek to recover the $1,000,000 deficit from the physician. In California, for example, the physician employer would be prohibited from seeking the deficit from the physician employee, but in most states, it is permitted. Because insurance policies usually do not cover physicians for damages, expenses, costs, etc as a result of an indemnification action, there is no practical way for a physician to protect himself/herself from the consequences. It is very important that physicians not sign any type of agreement with an indemnification clause in it without consulting an attorney first.

Another controversial issue is noncompete restrictions. In many states, a physician employer can restrict a physician employee from competing with it after an employment agreement is terminated. The noncompete prohibitions usually last for 1-2 years and extend over a geographic area, which often causes a terminated physician to relocate. Importantly, noncompete clauses are generally enforceable in most states.

Tail coverage

Malpractice tail coverage often can be an issue as well. For many years, physician employers routinely paid the cost of tail coverage for a physician employee after termination of employment. Tail coverage is necessary because most malpractice policies are claims-made insurance instead of occurrence insurance. This means that the insurance is applicable when a claim is filed versus when a malpractice act or omission occurred. Because of the significant cost of tail coverage, many physician employers attempt to transfer this financial responsibility to physician employees. Depending on a physician’s specialty, tail coverage can be quite costly. Consequently, it behooves physicians to carefully negotiate this issue. If a physician employer is unwilling to provide tail coverage, a compromise may be proposed whereby the physician employee is responsible only for the cost of tail coverage if he/she terminates the employment agreement without cause or if the physician employer terminates the employment agreement for cause. Conversely, the physician employer would be responsible for the cost if the physician employer terminates the employment agreement without cause or the physician employee terminates the employment agreement for cause.

Equity accrual

Finally, new physicians always should ask whether there is an opportunity to obtain equity in the organizations that hire them. Many for-profit physician employers provide such an opportunity to new physicians after 2-3 years. However, timing is just one factor. Importantly, the cost of the buy-in is critical especially to new physicians with student loans. Recognizing this problem, the trend today is for physician employers to have nominal buy-ins. Notwithstanding this trend, some physician employers also own ambulatory surgery centers and the buy-ins for these entities must be at fair market value and cannot be financed by the center or its owners under the law. Consequently, the buy-in for ambulatory surgery centers is usually substantial and requires a physician to obtain outside financing.

In conclusion, when evaluating the viability of a physician employment opportunity, salary should be only one factor considered. Fringe benefits, the opportunity for equity, and the fairness of the employment agreement also should be weighed heavily by a physician. It is important for a physician to be comfortable with his/her peers and work environment. Selecting the right job opportunity can be challenging. However, the process will be much easier if you remember the basic principles of negotiating.

You have finally completed your residency or fellowship, and now you have a job offer. With some trepidation, you decide to read the employment agreement that has been emailed to you. You quickly realize that you do not understand much of it. All those legal terms! You lament the fact that medical school never taught you about the business of medicine. What are you going to do? The choices are actually quite simple: You can take the time to educate yourself or you can hire an expert. This article will review some of the basic principles of negotiating as well as some of the critical issues found in physician employment agreements today.

Whether you represent yourself or hire someone to do it for you, it is important to understand some of the basic principles of negotiating. These principles generally are applicable whether you are buying a house or negotiating your employment agreement.

Negotiations

The most important principle is preparation. For example, many physicians negotiate their salaries during the interview process. Consequently, it is imperative that, before you negotiate your compensation, you know the range of salaries in your area for your specialty. It is also important to know whether salaries are usually guaranteed in your market, or whether production-based salaries (which are based on the amount of your billings) are the norm. Never go into an interview unprepared!

Always try to gain leverage in your negotiations. The easiest way to accomplish this is by having multiple offers, and subtly letting your suitors know this. Allow adequate time to negotiate; the more time you have, the easier it is to negotiate. Establish your objectives and try to anticipate the objectives of the other party. Determine your best-case and worse-case scenarios, as well as the most likely outcome. Do not negotiate against yourself and try to get something every time you give something. Define the nonnegotiable issues, and do not waste time on them. Keep cool and be flexible.

The first question you must answer when you receive an employment agreement is who is going to negotiate it. Many new physicians hire attorneys to help them with their employment agreements and employers expect as much. It is best to engage an attorney before you begin your job search so you can get a better understanding of how the attorney can help you. Most attorneys do not charge a prospective client for such information. However, many physicians wait until they actually receive an offer before contacting an attorney. It is not uncommon for physicians to negotiate their salaries during job interviews even if they eventually hire an attorney to help them. This is usually attributable to a lack of negotiating experience and an eagerness to determine whether a job offer is viable. Keep in mind that an attorney often can negotiate a better starting salary than you, so try to resist the temptation to negotiate your salary during the interview process.

Compensation

With compensation in mind, what are some of the important issues? Today, many physician employers are converting to production-based compensation models. Consequently, it is important for new physicians to obtain guaranteed base salaries during their first few years of employment while they are building their practices.

On occasion, new physicians initially are offered production-based compensation models, which also allocate a share of practice overhead expenses to them. This is a very dangerous compensation model for a new physician. Under such a model, it is possible that a new physician could have a negative balance in his/her cost center at the end of the year, and actually owe his/her employer money.

Some physicians may be offered income guarantees by hospitals. There are several different types of income guarantees but they are frequently categorized together even though they differ significantly. The most common income guarantees offered to physicians are physician recruitment agreements (PRAs). Under a PRA, a hospital usually guarantees that a physician who relocates to the service area of the hospital collects a minimum amount of monthly revenue for 1-2 years, which is known as the guarantee period. The hospital also guarantees to pay certain monthly expenses of the physician during the guarantee period. This arrangement is actually structured as a loan by the hospital to the physician, and requires the physician to execute a promissory note with the hospital for the amounts advanced to the physician by the hospital. The promissory note is forgiven if the physician continues to practice in the service area for 2-3 years after the guarantee period. This type of guarantee provides an excellent opportunity for a new physician to establish a solo practice. A variation of this model involves a third party such as a medical group. Under this model, the hospital continues to guarantee the revenue of the new physician and pays the medical group the expenses it incurs as a result of hiring the new physician. These expenses are known as incremental practice expenses. The medical group also becomes a signatory to the promissory note. Other health care entities also have begun to offer PRAs to physicians. For example, an independent practice association in California recently entered into a PRA with a gastroenterologist.

Keep in mind that the promissory note executed by the physician may affect the credit of the physician, especially if he/she wants to obtain financing for a home purchase. Also, a hospital may seek security for the performance of the promissory note by collateralizing the personal assets of the physician instead of just his/her practice assets; this should be avoided.

The other type of income guarantee is provided to hospital-based physicians such as pathologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, etc. Under this type of guarantee, a hospital ensures that the physicians receive a minimum threshold of collections. This type of guarantee may be necessary to attract hospital-based physicians to a hospital which has a low-income and/or Medicaid population. This is not a typical scenario for a gastroenterologist.

Some practices create incentives for physicians by offering a variety of bonuses. Most often these bonuses are production based but sometimes they are based on such quality issues as patient satisfaction. The most common types of production bonuses are based on attaining a level of collections above a dollar threshold or exceeding a minimum level of relative value units (RVUs).

To summarize, new physicians should always try to get at least a 2-year income guarantee. They should never allow an employer to allocate overhead to them during the first 2 years of employment. In addition, they should always try to negotiate realistic production-based bonuses.

Benefits

Fringe benefits are an integral part of a compensation package for a new physician. Most physician employers offer a generous package of health insurance, retirement, reimbursable expenses, and paid time off. These benefits should be clearly delineated in the employment agreement or employee handbook. A very common question about health benefits is when they become effective (the first day of employment, 30 days after employment, the first of the month after employment, etc.). This is significant because Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) is quite expensive. Another issue is whether health insurance also will cover the physician’s spouse and dependents. Most physician employers cover only the physician, not his/her spouse and dependents. If a new physician has a spouse who already provides family health benefits, it may behoove the physician to negotiate an allowance in lieu of health benefits.

Paid time off of 10-20 days are commonly given by physician employers to new physicians. Some employers also provide 5 or more additional days of paid time off for Continuing Medical Education (CME). Of course, once a physician goes onto production-based compensation, paid time off usually is not provided.

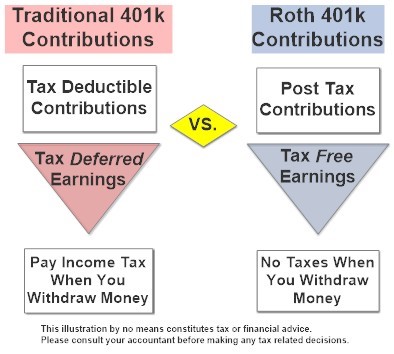

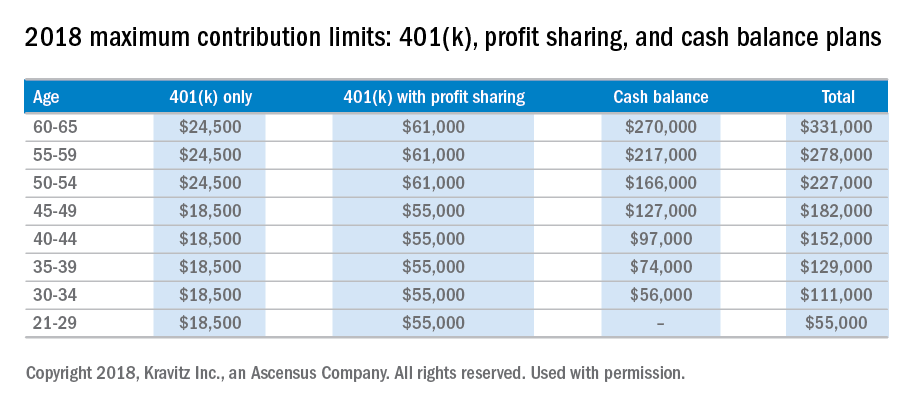

It is very important that a physician employer offer a retirement plan. Oftentimes, there is a matching contribution by the employer. However, it is not uncommon for there to be a year waiting period for eligibility in the retirement plan. Retirement plans vary significantly so it is advisable for a new physician to meet with the employer’s human resources department to get the details of the plan offered; the physician may want to confer with a financial advisor after obtaining this information.

Most physician employers reimburse licensing and DEA fees, medical staff dues, and board certification expenses. There is often a CME allowance as well. In competitive markets, some physician employers also offer innovative benefits such as student loan repayment programs, fellowship and residency stipends, and forgivable loans for housing. Sometimes these benefits are not included in the employment agreement; you may have to ask for them.

Indemnification/noncompetition

In addition to compensation and benefits, there are several other issues which are commonly found in employment agreements. Perhaps the most controversial is the issue of indemnification. The legal concept of indemnity allows a physician employer to recover damages and defense costs from a physician employee in certain circumstances. For example, if a physician employer has a $1,000,000/$3,000,000 malpractice policy covering itself and each of its physician employees, and if a physician commits malpractice and the award is $2,000,000, the employer may seek to recover the $1,000,000 deficit from the physician. In California, for example, the physician employer would be prohibited from seeking the deficit from the physician employee, but in most states, it is permitted. Because insurance policies usually do not cover physicians for damages, expenses, costs, etc as a result of an indemnification action, there is no practical way for a physician to protect himself/herself from the consequences. It is very important that physicians not sign any type of agreement with an indemnification clause in it without consulting an attorney first.

Another controversial issue is noncompete restrictions. In many states, a physician employer can restrict a physician employee from competing with it after an employment agreement is terminated. The noncompete prohibitions usually last for 1-2 years and extend over a geographic area, which often causes a terminated physician to relocate. Importantly, noncompete clauses are generally enforceable in most states.

Tail coverage

Malpractice tail coverage often can be an issue as well. For many years, physician employers routinely paid the cost of tail coverage for a physician employee after termination of employment. Tail coverage is necessary because most malpractice policies are claims-made insurance instead of occurrence insurance. This means that the insurance is applicable when a claim is filed versus when a malpractice act or omission occurred. Because of the significant cost of tail coverage, many physician employers attempt to transfer this financial responsibility to physician employees. Depending on a physician’s specialty, tail coverage can be quite costly. Consequently, it behooves physicians to carefully negotiate this issue. If a physician employer is unwilling to provide tail coverage, a compromise may be proposed whereby the physician employee is responsible only for the cost of tail coverage if he/she terminates the employment agreement without cause or if the physician employer terminates the employment agreement for cause. Conversely, the physician employer would be responsible for the cost if the physician employer terminates the employment agreement without cause or the physician employee terminates the employment agreement for cause.

Equity accrual

Finally, new physicians always should ask whether there is an opportunity to obtain equity in the organizations that hire them. Many for-profit physician employers provide such an opportunity to new physicians after 2-3 years. However, timing is just one factor. Importantly, the cost of the buy-in is critical especially to new physicians with student loans. Recognizing this problem, the trend today is for physician employers to have nominal buy-ins. Notwithstanding this trend, some physician employers also own ambulatory surgery centers and the buy-ins for these entities must be at fair market value and cannot be financed by the center or its owners under the law. Consequently, the buy-in for ambulatory surgery centers is usually substantial and requires a physician to obtain outside financing.

In conclusion, when evaluating the viability of a physician employment opportunity, salary should be only one factor considered. Fringe benefits, the opportunity for equity, and the fairness of the employment agreement also should be weighed heavily by a physician. It is important for a physician to be comfortable with his/her peers and work environment. Selecting the right job opportunity can be challenging. However, the process will be much easier if you remember the basic principles of negotiating.

You have finally completed your residency or fellowship, and now you have a job offer. With some trepidation, you decide to read the employment agreement that has been emailed to you. You quickly realize that you do not understand much of it. All those legal terms! You lament the fact that medical school never taught you about the business of medicine. What are you going to do? The choices are actually quite simple: You can take the time to educate yourself or you can hire an expert. This article will review some of the basic principles of negotiating as well as some of the critical issues found in physician employment agreements today.

Whether you represent yourself or hire someone to do it for you, it is important to understand some of the basic principles of negotiating. These principles generally are applicable whether you are buying a house or negotiating your employment agreement.

Negotiations

The most important principle is preparation. For example, many physicians negotiate their salaries during the interview process. Consequently, it is imperative that, before you negotiate your compensation, you know the range of salaries in your area for your specialty. It is also important to know whether salaries are usually guaranteed in your market, or whether production-based salaries (which are based on the amount of your billings) are the norm. Never go into an interview unprepared!

Always try to gain leverage in your negotiations. The easiest way to accomplish this is by having multiple offers, and subtly letting your suitors know this. Allow adequate time to negotiate; the more time you have, the easier it is to negotiate. Establish your objectives and try to anticipate the objectives of the other party. Determine your best-case and worse-case scenarios, as well as the most likely outcome. Do not negotiate against yourself and try to get something every time you give something. Define the nonnegotiable issues, and do not waste time on them. Keep cool and be flexible.

The first question you must answer when you receive an employment agreement is who is going to negotiate it. Many new physicians hire attorneys to help them with their employment agreements and employers expect as much. It is best to engage an attorney before you begin your job search so you can get a better understanding of how the attorney can help you. Most attorneys do not charge a prospective client for such information. However, many physicians wait until they actually receive an offer before contacting an attorney. It is not uncommon for physicians to negotiate their salaries during job interviews even if they eventually hire an attorney to help them. This is usually attributable to a lack of negotiating experience and an eagerness to determine whether a job offer is viable. Keep in mind that an attorney often can negotiate a better starting salary than you, so try to resist the temptation to negotiate your salary during the interview process.

Compensation

With compensation in mind, what are some of the important issues? Today, many physician employers are converting to production-based compensation models. Consequently, it is important for new physicians to obtain guaranteed base salaries during their first few years of employment while they are building their practices.

On occasion, new physicians initially are offered production-based compensation models, which also allocate a share of practice overhead expenses to them. This is a very dangerous compensation model for a new physician. Under such a model, it is possible that a new physician could have a negative balance in his/her cost center at the end of the year, and actually owe his/her employer money.

Some physicians may be offered income guarantees by hospitals. There are several different types of income guarantees but they are frequently categorized together even though they differ significantly. The most common income guarantees offered to physicians are physician recruitment agreements (PRAs). Under a PRA, a hospital usually guarantees that a physician who relocates to the service area of the hospital collects a minimum amount of monthly revenue for 1-2 years, which is known as the guarantee period. The hospital also guarantees to pay certain monthly expenses of the physician during the guarantee period. This arrangement is actually structured as a loan by the hospital to the physician, and requires the physician to execute a promissory note with the hospital for the amounts advanced to the physician by the hospital. The promissory note is forgiven if the physician continues to practice in the service area for 2-3 years after the guarantee period. This type of guarantee provides an excellent opportunity for a new physician to establish a solo practice. A variation of this model involves a third party such as a medical group. Under this model, the hospital continues to guarantee the revenue of the new physician and pays the medical group the expenses it incurs as a result of hiring the new physician. These expenses are known as incremental practice expenses. The medical group also becomes a signatory to the promissory note. Other health care entities also have begun to offer PRAs to physicians. For example, an independent practice association in California recently entered into a PRA with a gastroenterologist.

Keep in mind that the promissory note executed by the physician may affect the credit of the physician, especially if he/she wants to obtain financing for a home purchase. Also, a hospital may seek security for the performance of the promissory note by collateralizing the personal assets of the physician instead of just his/her practice assets; this should be avoided.

The other type of income guarantee is provided to hospital-based physicians such as pathologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, etc. Under this type of guarantee, a hospital ensures that the physicians receive a minimum threshold of collections. This type of guarantee may be necessary to attract hospital-based physicians to a hospital which has a low-income and/or Medicaid population. This is not a typical scenario for a gastroenterologist.

Some practices create incentives for physicians by offering a variety of bonuses. Most often these bonuses are production based but sometimes they are based on such quality issues as patient satisfaction. The most common types of production bonuses are based on attaining a level of collections above a dollar threshold or exceeding a minimum level of relative value units (RVUs).

To summarize, new physicians should always try to get at least a 2-year income guarantee. They should never allow an employer to allocate overhead to them during the first 2 years of employment. In addition, they should always try to negotiate realistic production-based bonuses.

Benefits

Fringe benefits are an integral part of a compensation package for a new physician. Most physician employers offer a generous package of health insurance, retirement, reimbursable expenses, and paid time off. These benefits should be clearly delineated in the employment agreement or employee handbook. A very common question about health benefits is when they become effective (the first day of employment, 30 days after employment, the first of the month after employment, etc.). This is significant because Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) is quite expensive. Another issue is whether health insurance also will cover the physician’s spouse and dependents. Most physician employers cover only the physician, not his/her spouse and dependents. If a new physician has a spouse who already provides family health benefits, it may behoove the physician to negotiate an allowance in lieu of health benefits.

Paid time off of 10-20 days are commonly given by physician employers to new physicians. Some employers also provide 5 or more additional days of paid time off for Continuing Medical Education (CME). Of course, once a physician goes onto production-based compensation, paid time off usually is not provided.

It is very important that a physician employer offer a retirement plan. Oftentimes, there is a matching contribution by the employer. However, it is not uncommon for there to be a year waiting period for eligibility in the retirement plan. Retirement plans vary significantly so it is advisable for a new physician to meet with the employer’s human resources department to get the details of the plan offered; the physician may want to confer with a financial advisor after obtaining this information.

Most physician employers reimburse licensing and DEA fees, medical staff dues, and board certification expenses. There is often a CME allowance as well. In competitive markets, some physician employers also offer innovative benefits such as student loan repayment programs, fellowship and residency stipends, and forgivable loans for housing. Sometimes these benefits are not included in the employment agreement; you may have to ask for them.

Indemnification/noncompetition

In addition to compensation and benefits, there are several other issues which are commonly found in employment agreements. Perhaps the most controversial is the issue of indemnification. The legal concept of indemnity allows a physician employer to recover damages and defense costs from a physician employee in certain circumstances. For example, if a physician employer has a $1,000,000/$3,000,000 malpractice policy covering itself and each of its physician employees, and if a physician commits malpractice and the award is $2,000,000, the employer may seek to recover the $1,000,000 deficit from the physician. In California, for example, the physician employer would be prohibited from seeking the deficit from the physician employee, but in most states, it is permitted. Because insurance policies usually do not cover physicians for damages, expenses, costs, etc as a result of an indemnification action, there is no practical way for a physician to protect himself/herself from the consequences. It is very important that physicians not sign any type of agreement with an indemnification clause in it without consulting an attorney first.

Another controversial issue is noncompete restrictions. In many states, a physician employer can restrict a physician employee from competing with it after an employment agreement is terminated. The noncompete prohibitions usually last for 1-2 years and extend over a geographic area, which often causes a terminated physician to relocate. Importantly, noncompete clauses are generally enforceable in most states.

Tail coverage

Malpractice tail coverage often can be an issue as well. For many years, physician employers routinely paid the cost of tail coverage for a physician employee after termination of employment. Tail coverage is necessary because most malpractice policies are claims-made insurance instead of occurrence insurance. This means that the insurance is applicable when a claim is filed versus when a malpractice act or omission occurred. Because of the significant cost of tail coverage, many physician employers attempt to transfer this financial responsibility to physician employees. Depending on a physician’s specialty, tail coverage can be quite costly. Consequently, it behooves physicians to carefully negotiate this issue. If a physician employer is unwilling to provide tail coverage, a compromise may be proposed whereby the physician employee is responsible only for the cost of tail coverage if he/she terminates the employment agreement without cause or if the physician employer terminates the employment agreement for cause. Conversely, the physician employer would be responsible for the cost if the physician employer terminates the employment agreement without cause or the physician employee terminates the employment agreement for cause.

Equity accrual

Finally, new physicians always should ask whether there is an opportunity to obtain equity in the organizations that hire them. Many for-profit physician employers provide such an opportunity to new physicians after 2-3 years. However, timing is just one factor. Importantly, the cost of the buy-in is critical especially to new physicians with student loans. Recognizing this problem, the trend today is for physician employers to have nominal buy-ins. Notwithstanding this trend, some physician employers also own ambulatory surgery centers and the buy-ins for these entities must be at fair market value and cannot be financed by the center or its owners under the law. Consequently, the buy-in for ambulatory surgery centers is usually substantial and requires a physician to obtain outside financing.

In conclusion, when evaluating the viability of a physician employment opportunity, salary should be only one factor considered. Fringe benefits, the opportunity for equity, and the fairness of the employment agreement also should be weighed heavily by a physician. It is important for a physician to be comfortable with his/her peers and work environment. Selecting the right job opportunity can be challenging. However, the process will be much easier if you remember the basic principles of negotiating.

My experience with the 2017 Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship

When I entered the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship last year, many of my cofellows asked, “What exactly is an editorial fellowship?” After completing the program, I can now reflect on what was truly a fantastic year-long experience that complemented my final year of fellowship training.

Manuscripts certainly don’t review and accept themselves into journals, and fellowship training usually gives little insight into how manuscripts move through the submission, peer review, and production processes. What happens while authors wait for an editorial decision?

Since its first publication in 1943, Gastroenterology has importantly affected clinical care and the direction of research in our field. The quality of the American Gastroenterological Association’s flagship journal is derived from the sweat and muscle put in daily by gastroenterology-oriented and hepatology-oriented professionals who strive to transform the steady stream of cutting-edge manuscript submissions into an influential monthly publication read by a broad audience of clinicians, trainees, academic researchers, and policy makers. Without a doubt, this fellowship provided me with a sincere appreciation for the dedication that the board of editors puts into the peer review process and into maintaining the quality of monthly publications.

Near the beginning of my editorial fellowship, I spent a week at Vanderbilt University with the on-site editors. This was an irreplaceable opportunity for a trainee like myself to meet with both clinical- and research-oriented academic gastroenterologists who integrate demanding editorial roles into busy and fulfilling professional careers. Throughout my week there, I met with editors and staff who held various roles within the journal. Overall, this experience taught me about what metrics the journal uses to ensure quality, how manuscripts move from submission to publication, and how the direction and content of the journal is directed toward both AGA members and a broader readership.

At its core, the fellowship was focused on teaching the fundamental process of peer review. High-quality reviews for Gastroenterology provide consultative content and methodological expertise to editors who can then provide direction and make editorial recommendations to the authors. During my fellowship, I learned how to write a structured and nuanced review on the basis of novelty, clinical relevance and effects, and methodological rigor. I was paired with one of the associate editors on the basis of my primary content area of interest and regularly provided reviews for original article submissions. As the year progressed, I become more comfortable with reviewing beyond my immediate knowledge base. I also became more adept at providing detailed comments that would be insightful and accessible to both authors and editors.

Each week, I participated in a phone call with the board of editors, which was composed of thought leaders with content expertise in both gastroenterology and hepatology. During the call, we would thoughtfully critique some of the most cutting-edge research in our field; each manuscript often represented the culmination of years of meticulous work by research groups and multinational collaborations. From a fellow’s perspective, these calls gave me access to what may be the most insightful discussions taking place in our field, discussions which could have potential implications on future disease management principles and clinical practice guidelines. Through our meetings, it became apparent how much work goes into finding quality reviewers and how much time goes into assimilating the resulting recommendations into a cohesive discussion. This was an opportunity to learn how associate editors walk the entire board through a manuscript: from a basis of current knowledge and practice, through the conduct and findings of a particular study, and ultimately, to how study findings might affect the field.

What I came away with the most from the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship was an appreciation for the importance of the editorial and peer review process in maintaining the integrity and detail needed in high-quality research. Ultimately, this fellowship gave me a meaningful and immediate way to give back to the field that I can continue over the course of my professional career. I am certain that this unique program will continue to give future editorial fellows the skills and motivation they need to become actively involved in the editorial and peer review processes when they are beginning their independent careers.

Dr. Shah, MD, MBA, is an assistant professor; he is also the director of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility in the division of gastroenterology in the department of internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

When I entered the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship last year, many of my cofellows asked, “What exactly is an editorial fellowship?” After completing the program, I can now reflect on what was truly a fantastic year-long experience that complemented my final year of fellowship training.

Manuscripts certainly don’t review and accept themselves into journals, and fellowship training usually gives little insight into how manuscripts move through the submission, peer review, and production processes. What happens while authors wait for an editorial decision?

Since its first publication in 1943, Gastroenterology has importantly affected clinical care and the direction of research in our field. The quality of the American Gastroenterological Association’s flagship journal is derived from the sweat and muscle put in daily by gastroenterology-oriented and hepatology-oriented professionals who strive to transform the steady stream of cutting-edge manuscript submissions into an influential monthly publication read by a broad audience of clinicians, trainees, academic researchers, and policy makers. Without a doubt, this fellowship provided me with a sincere appreciation for the dedication that the board of editors puts into the peer review process and into maintaining the quality of monthly publications.

Near the beginning of my editorial fellowship, I spent a week at Vanderbilt University with the on-site editors. This was an irreplaceable opportunity for a trainee like myself to meet with both clinical- and research-oriented academic gastroenterologists who integrate demanding editorial roles into busy and fulfilling professional careers. Throughout my week there, I met with editors and staff who held various roles within the journal. Overall, this experience taught me about what metrics the journal uses to ensure quality, how manuscripts move from submission to publication, and how the direction and content of the journal is directed toward both AGA members and a broader readership.

At its core, the fellowship was focused on teaching the fundamental process of peer review. High-quality reviews for Gastroenterology provide consultative content and methodological expertise to editors who can then provide direction and make editorial recommendations to the authors. During my fellowship, I learned how to write a structured and nuanced review on the basis of novelty, clinical relevance and effects, and methodological rigor. I was paired with one of the associate editors on the basis of my primary content area of interest and regularly provided reviews for original article submissions. As the year progressed, I become more comfortable with reviewing beyond my immediate knowledge base. I also became more adept at providing detailed comments that would be insightful and accessible to both authors and editors.

Each week, I participated in a phone call with the board of editors, which was composed of thought leaders with content expertise in both gastroenterology and hepatology. During the call, we would thoughtfully critique some of the most cutting-edge research in our field; each manuscript often represented the culmination of years of meticulous work by research groups and multinational collaborations. From a fellow’s perspective, these calls gave me access to what may be the most insightful discussions taking place in our field, discussions which could have potential implications on future disease management principles and clinical practice guidelines. Through our meetings, it became apparent how much work goes into finding quality reviewers and how much time goes into assimilating the resulting recommendations into a cohesive discussion. This was an opportunity to learn how associate editors walk the entire board through a manuscript: from a basis of current knowledge and practice, through the conduct and findings of a particular study, and ultimately, to how study findings might affect the field.

What I came away with the most from the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship was an appreciation for the importance of the editorial and peer review process in maintaining the integrity and detail needed in high-quality research. Ultimately, this fellowship gave me a meaningful and immediate way to give back to the field that I can continue over the course of my professional career. I am certain that this unique program will continue to give future editorial fellows the skills and motivation they need to become actively involved in the editorial and peer review processes when they are beginning their independent careers.

Dr. Shah, MD, MBA, is an assistant professor; he is also the director of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility in the division of gastroenterology in the department of internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

When I entered the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship last year, many of my cofellows asked, “What exactly is an editorial fellowship?” After completing the program, I can now reflect on what was truly a fantastic year-long experience that complemented my final year of fellowship training.

Manuscripts certainly don’t review and accept themselves into journals, and fellowship training usually gives little insight into how manuscripts move through the submission, peer review, and production processes. What happens while authors wait for an editorial decision?

Since its first publication in 1943, Gastroenterology has importantly affected clinical care and the direction of research in our field. The quality of the American Gastroenterological Association’s flagship journal is derived from the sweat and muscle put in daily by gastroenterology-oriented and hepatology-oriented professionals who strive to transform the steady stream of cutting-edge manuscript submissions into an influential monthly publication read by a broad audience of clinicians, trainees, academic researchers, and policy makers. Without a doubt, this fellowship provided me with a sincere appreciation for the dedication that the board of editors puts into the peer review process and into maintaining the quality of monthly publications.

Near the beginning of my editorial fellowship, I spent a week at Vanderbilt University with the on-site editors. This was an irreplaceable opportunity for a trainee like myself to meet with both clinical- and research-oriented academic gastroenterologists who integrate demanding editorial roles into busy and fulfilling professional careers. Throughout my week there, I met with editors and staff who held various roles within the journal. Overall, this experience taught me about what metrics the journal uses to ensure quality, how manuscripts move from submission to publication, and how the direction and content of the journal is directed toward both AGA members and a broader readership.

At its core, the fellowship was focused on teaching the fundamental process of peer review. High-quality reviews for Gastroenterology provide consultative content and methodological expertise to editors who can then provide direction and make editorial recommendations to the authors. During my fellowship, I learned how to write a structured and nuanced review on the basis of novelty, clinical relevance and effects, and methodological rigor. I was paired with one of the associate editors on the basis of my primary content area of interest and regularly provided reviews for original article submissions. As the year progressed, I become more comfortable with reviewing beyond my immediate knowledge base. I also became more adept at providing detailed comments that would be insightful and accessible to both authors and editors.

Each week, I participated in a phone call with the board of editors, which was composed of thought leaders with content expertise in both gastroenterology and hepatology. During the call, we would thoughtfully critique some of the most cutting-edge research in our field; each manuscript often represented the culmination of years of meticulous work by research groups and multinational collaborations. From a fellow’s perspective, these calls gave me access to what may be the most insightful discussions taking place in our field, discussions which could have potential implications on future disease management principles and clinical practice guidelines. Through our meetings, it became apparent how much work goes into finding quality reviewers and how much time goes into assimilating the resulting recommendations into a cohesive discussion. This was an opportunity to learn how associate editors walk the entire board through a manuscript: from a basis of current knowledge and practice, through the conduct and findings of a particular study, and ultimately, to how study findings might affect the field.

What I came away with the most from the Gastroenterology Editorial Fellowship was an appreciation for the importance of the editorial and peer review process in maintaining the integrity and detail needed in high-quality research. Ultimately, this fellowship gave me a meaningful and immediate way to give back to the field that I can continue over the course of my professional career. I am certain that this unique program will continue to give future editorial fellows the skills and motivation they need to become actively involved in the editorial and peer review processes when they are beginning their independent careers.

Dr. Shah, MD, MBA, is an assistant professor; he is also the director of the Center for Gastrointestinal Motility in the division of gastroenterology in the department of internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

May 2018

Gastroenterology

How to perform a high-quality examination in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Everson M et al. 2018 April;154(5):1222-6. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.001

How to become a physician executive: From fellowship to leadership. Shah ED and Allen JI. 2018 March;154(4):784-7. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.009

How to obtain training in nutrition during the gastroenterology fellowship. Micic D et al.2018 Feb;154(3):467-70. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.006

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

Physician burnout: The hidden health care crisis. Lacy BE and Chan JL.2018 March;16(3):311-7. doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

AGA Perspectives

Vol. 14 No. 1 | December/January 2018

Everything you need to know about MOC. AGA staff writers.

Vol. 13 No. 5 | October/November 2017

Gastroenterologists as patient advocates in public policy. Siddique SM and Mehta S.

Gastroenterology

How to perform a high-quality examination in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Everson M et al. 2018 April;154(5):1222-6. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.001

How to become a physician executive: From fellowship to leadership. Shah ED and Allen JI. 2018 March;154(4):784-7. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.009

How to obtain training in nutrition during the gastroenterology fellowship. Micic D et al.2018 Feb;154(3):467-70. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.006

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

Physician burnout: The hidden health care crisis. Lacy BE and Chan JL.2018 March;16(3):311-7. doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

AGA Perspectives

Vol. 14 No. 1 | December/January 2018

Everything you need to know about MOC. AGA staff writers.

Vol. 13 No. 5 | October/November 2017

Gastroenterologists as patient advocates in public policy. Siddique SM and Mehta S.

Gastroenterology

How to perform a high-quality examination in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Everson M et al. 2018 April;154(5):1222-6. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.001

How to become a physician executive: From fellowship to leadership. Shah ED and Allen JI. 2018 March;154(4):784-7. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.009

How to obtain training in nutrition during the gastroenterology fellowship. Micic D et al.2018 Feb;154(3):467-70. doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.006

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

Physician burnout: The hidden health care crisis. Lacy BE and Chan JL.2018 March;16(3):311-7. doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

AGA Perspectives

Vol. 14 No. 1 | December/January 2018

Everything you need to know about MOC. AGA staff writers.

Vol. 13 No. 5 | October/November 2017

Gastroenterologists as patient advocates in public policy. Siddique SM and Mehta S.

Underserved populations and colorectal cancer screening: Patient perceptions of barriers to care and effective interventions

Editor's Note:

Importantly, these barriers often vary between specific population subsets. In this month’s In Focus article, brought to you by The New Gastroenterologist, the members of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee provide an enlightening overview of the barriers affecting underserved populations as well as strategies that can be employed to overcome these impediments. Better understanding of patient-specific barriers will, I hope, allow us to more effectively redress them and ultimately increase colorectal cancer screening rates in all populations.

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Despite the positive public health effects of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, there remains differential uptake of CRC screening in the United States. Minority populations born in the United States and immigrant populations are among those with the lowest rates of CRC screening, and both socioeconomic status and ethnicity are strongly associated with stage of CRC at diagnosis.1,2 Thus, recognizing the economic, social, and cultural factors that result in low rates of CRC screening in underserved populations is important in order to devise targeted interventions to increase CRC uptake and reduce morbidity and mortality in these populations.

What are the facts and figures?

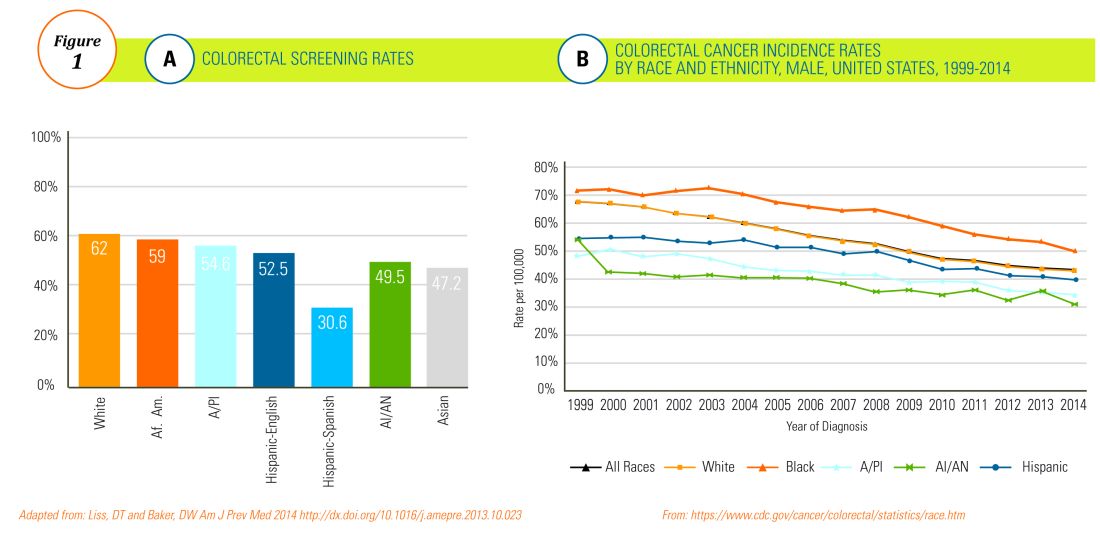

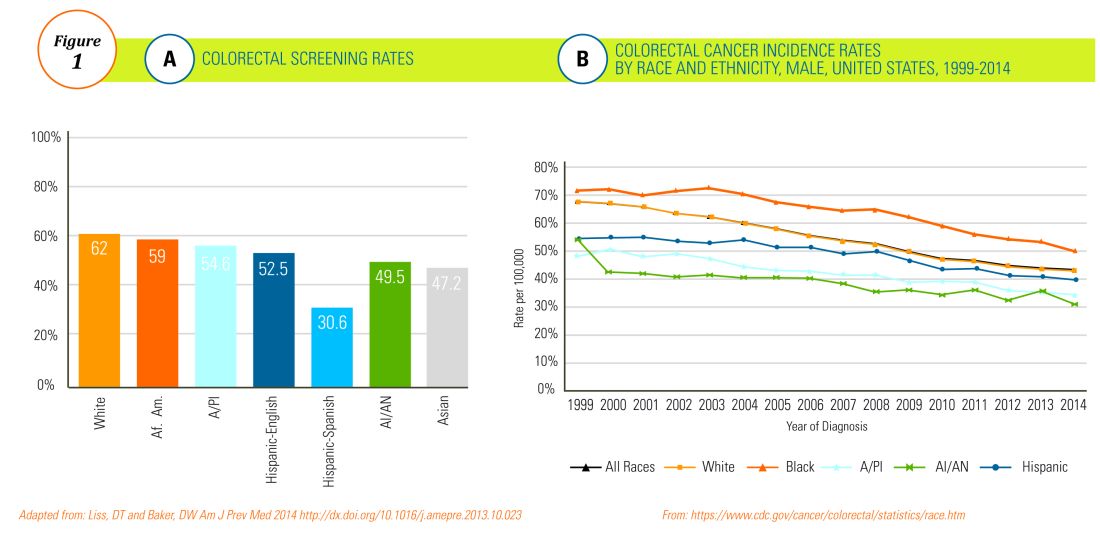

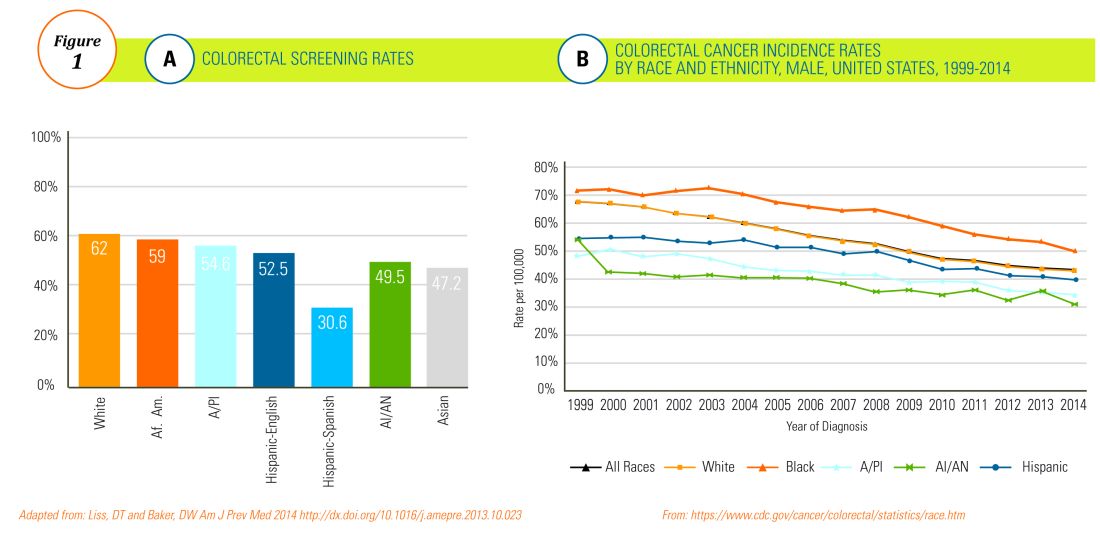

The overall rate of screening colonoscopies has increased in all ethnic groups in the past 10 years but still falls below the goal of 71% established by the Healthy People project (www.healthypeople.gov) for the year 2020.3 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ethnicity-specific data for U.S.-born populations, 60% of whites, 55% of African Americans (AA), 50% of American Indian/Alaskan natives (AI/AN), 46% of Latino Americans, and 47% of Asians undergo CRC screening (Figure 1A).4 While CRC incidence in non-Hispanic whites age 50 years and older has dropped by 32% since 2000 because of screening, this trend has not been observed in AAs.5,6

The incidence of CRC in AAs is estimated at 49/10,000, one of the highest amongst U.S. populations and is the second and third most common cancer in AA women and men, respectively (Figure 1B).

Similar to AAs, AI/AN patients present with more advanced CRC disease and at younger ages and have lower survival rates, compared with other racial groups, a trend that has not changed in the last decade.7 CRC screening data in this population vary according to sex, geographic location, and health care utilization, with as few as 4.0% of asymptomatic, average-risk AI/ANs who receive medical care in the Indian Health Services being screened for CRC.8

The low rate of CRC screening among Latinos also poses a significant obstacle to the Healthy People project since it is expected that by 2060 Latinos will constitute 30% of the U.S. population. Therefore, strategies to improve CRC screening in this population are needed to continue the gains made in overall CRC mortality rates.

The percentage of immigrants in the U.S. population increased from 4.7% in 1970 to 13.5% in 2015. Immigrants, regardless of their ethnicity, represent a very vulnerable population, and CRC screening data in this population are not as robust as for U.S.-born groups. In general, immigrants have substantially lower CRC screening rates, compared with U.S.-born populations (21% vs. 60%),9 and it is suspected that additional, significant barriers to CRC screening and care exist for undocumented immigrants.

Another often overlooked group, are individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. In this group, screening rates range from 49% to 65%.10

Finally, while information is available for many health care conditions and disparities faced by various ethnic groups, there are few CRC screening data for the LGBTQ community. Perhaps amplifying this problem is the existence of conflicting data in this population, with some studies suggesting there is no difference in CRC risk across groups in the LGBTQ community and others suggesting an increased risk.11,12 Notably, sexual orientation has been identified as a positive predictor of CRC screening in gay and bisexual men – CRC screening rates are higher in these groups, compared with heterosexual men.13 In contrast, no such difference has been found between homosexual and heterosexual women.14

What are the barriers?

Several common themes contribute to disparities in CRC screening among minority groups, including psychosocial/cultural, socioeconomic, provider-specific, and insurance-related factors. Some patient-related barriers include issues of illiteracy, having poor health literacy or English proficiency, having only grade school education,15,16 cultural misconceptions, transportation issues, difficulties affording copayments or deductibles, and a lack of follow-up for scheduled appointments and exams.17-20 Poor health literacy has a profound effect on exam perceptions, fear of test results, and compliance with scheduling tests and bowel preparation instructions21-25; it also affects one’s understanding of the importance of CRC screening, the recommended screening age, and the available choice of screening tests.

Even when some apparent barriers are mitigated, disparities in CRC screening remain. For example, even among the insured and among Medicare beneficiaries, screening rates and adequate follow-up rates after abnormal findings remain lower among AAs and those of low socioeconomic status than they are among whites.26-28 At least part of this paradox results from the presence of unmeasured cultural/belief systems that affect CRC screening uptake. Some of these factors include fear and/or denial of CRC diagnoses, mistrust of the health care system, and reluctance to undergo medical treatment and surgery.16,29 AAs are also less likely to be aware of a family history of CRC and to discuss personal and/or family history of CRC or polyps, which can thereby hinder the identification of high-risk individuals who would benefit from early screening.15,30

The deeply rooted sense of fatalism also plays a crucial role and has been cited for many minority and immigrant populations. Fatalism leads patients to view a diagnosis of cancer as a matter of “fate” or “God’s will,” and therefore, it is to be endured.23,31 Similarly, in a qualitative study of 44 Somali men living in St. Paul and Minneapolis, believing cancer was more common in whites, believing they were protected from cancer by God, fearing a cancer diagnosis, and fearing ostracism from their community were reported as barriers to cancer screening.32