User login

Malpractice Chronicle

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Was Follow-Up Adequate After Neurosurgery in Cancún?

Shortly after arriving in Mexico for a brief stay, a 44-year-old woman collapsed in the customs area. She was taken to a hospital in Cancún, where she underwent emergency neurosurgery for a brain bleed. After several days of hospitalization, she was stabilized and returned to Michigan with instructions to see her family clinician.

Her appointment was delayed by an ice storm, which interrupted power to the office of the defendant internist, Dr. M. That Saturday, the woman visited the office's clinic and was examined by the defendant family practitioner, Dr. P. She presented with a shaved head and a neurosurgical scar on the left side of her head; she complained of headache and some blurred or double vision. She gave Dr. P. a list of medications and medical records (in Spanish) from the Mexican hospital.

Findings on her physical examination were normal. She was instructed to return to see Dr. M., and she did so at the clinic on the following Monday. She repeated her complaints of double vision, headache, and fatigue. Dr. M. charged his office staff with attempting to have the Mexican records translated and to arrange for a neurosurgery appointment.

The patient was ultimately scheduled for head CT and an office visit with a neurosurgeon six days later. The day after those arrangements were made, however, she experienced a massive brain bleed and died.

According to the plaintiff, the surgeons in Mexico drained the blood from the initial bleed but did not detect its source—an aneurysm in the subarachnoid space. The plaintiff alleged that the defendants should have hospitalized the decedent immediately upon her return from Mexico or sent her for an immediate neurosurgical consult. Had the decedent undergone CT immediately, it was argued, the aneurysm would have been detected, surgery would have been performed, and she would have survived.

The defendants argued that the neurosurgical follow-up was out of their area of expertise and that they made appropriate arrangements for the decedent to be seen by a neurosurgeon. They maintained that the decedent appeared stable and seemed to be improving and that it was possible that the fatal bleed was not related to the first bleed. The defendants also claimed that definitive treatment should have been given in Mexico.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned.

Ultrasound Misplaced, Diagnosis Delayed for a Year

In March 2003 at age 2, the minor plaintiff was admitted to the defendant hospital under the care of the defendant pediatric urologist, who was treating her for bilateral vesicoureteral urinary reflux and frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs). The defendant surgically reimplanted both ureters to stop urinary reflux. The toddler was discharged to home in her parents' care two days after the procedure.

The child continued to experience UTIs. Renal ultrasonography revealed a blockage in the left ureter, but the ultrasound was lost by the defendant hospital. Results were never conveyed to the ordering physicians, who failed to follow up to obtain them.

In April 2004, the defendant urologist diagnosed the condition and determined that it had gone untreated for a year. Repeat renal ultrasonography demonstrated the blockage, and a nuclear renal scan confirmed that the child's left kidney was no longer functioning at all as a result of urinary backup. In addition to losing all function of the left kidney, the child has compromised function in the right kidney. She is expected to require dialysis in the future and eventually kidney transplantation.

A $9.75 million settlement was reached.

Complications of Undiagnosed Diverticulitis

A 62-year-old woman visited the defendant internist with complaints of abdominal pressure, poor appetite, weakness, and dizziness. Her medical history included hypertension, diverticulitis, hysterectomy, and tonsillectomy.

The defendant ordered a chest x-ray, complete blood count, and urinalysis. After reviewing test results, the defendant made a diagnosis of urinary tract infection and prescribed ceftriaxone by intramuscular injection and oral ciprofloxacin.

After receiving the first injection of ceftriaxone, the patient called the defendant's office, complaining of increased discomfort. She requested admission to the hospital, which was allegedly refused by a member of the office staff. The following day, the plaintiff was transported to the hospital by ambulance with complaints of left lower quadrant pain, intermittent for one week and worsening that evening. The plaintiff reported no nausea or diarrhea but was belching.

The emergency department physician identified tender palpation in the abdomen with no rebounding and decreased bowel sounds. The defendant internist's answering service was contacted, and the covering physician ordered admission with a diagnosis of diverticulitis. CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed evidence of free air under the hemidiaphragm, ascites, and phlegmonous reaction; the results also suggested diverticulitis with perforation in the rectosigmoid region and inflammatory changes.

Five hours later, the patient was taken to surgery for an exploratory laparotomy and colostomy to address the apparent perforated diverticulum. Her immediate postoperative course included profound hypotension with narrow-complex tachycardia. These developments, allegedly resulting from abdominal sepsis due to the delay in diagnosing the perforated diverticulum, necessitated pressors and dopamine.

Soon thereafter, the patient developed right-leg ischemia. She underwent embolectomy and thrombectomy to the right common femoral artery and the superficial femoral artery, with repair to the right profunda by use of a saphenous vein patch angioplasty. Two days later, the patient was taken to surgery for an above-knee amputation.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant was negligent in failing to recognize early manifestations of diverticulitis and to order CT or MRl. The plaintiff also claimed that she should have been hospitalized when she requested admission.

The defendant maintained that the patient's history and the laboratory study results suggested that she had the flu or a urinary tract infection and that hospitalization was not needed. The defendant also maintained that when he called for a surgical consultation, the surgeon did not arrive for four and one-half hours.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned. A motion for a new trial was pending.

Surgery Continued Despite Patient's Deteriorating Condition

In 1986, the patient, then age 8, was found to be mildly mentally retarded (IQ, 59 to 70). He also had paranoid schizophrenia, causing him to hear voices in his head. The patient lived with his sister, who served as his guardian.

At age 19, the patient was scheduled to undergo surgery to correct curvature of the spine. The operation was to be performed by Dr. R., assisted by Dr. M. and by an anesthesiologist, Dr. L.

About one hour into the surgery, the patient began to manifest decreased urinary output with no known cause, but the procedure continued. About 90 minutes later, an equipment malfunction made it impossible for the medical team to monitor the patient's nerve responses and oxygen levels, but the surgery still continued.

At some point during the surgery, the patient had an unexplained blood loss and his serum calcium level dropped below normal. He also experienced a loss of oxygen to the brain, then went into cardiac arrest. At that point, the surgery was discontinued, uncompleted.

The patient was comatose for several days, during which he displayed prolonged seizure activity. After regaining consciousness, he remained in the hospital for nearly four weeks before being transferred to another facility for rehabilitation.

The patient continues to have symptoms of various neurologic problems, including athetoid-choreiform movement, which causes a general loss of balance and muscular control and cognitive deficits, which make him unable to communicate.

The plaintiff claimed that the surgery should have been stopped when the problems arose. The plaintiff also claimed that Dr. R. should have ordered intraoperative lab work when the plaintiff's condition deteriorated.

The matter was ultimately tried against Drs. R. and L. only. They denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a $3 million verdict was returned.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Was Follow-Up Adequate After Neurosurgery in Cancún?

Shortly after arriving in Mexico for a brief stay, a 44-year-old woman collapsed in the customs area. She was taken to a hospital in Cancún, where she underwent emergency neurosurgery for a brain bleed. After several days of hospitalization, she was stabilized and returned to Michigan with instructions to see her family clinician.

Her appointment was delayed by an ice storm, which interrupted power to the office of the defendant internist, Dr. M. That Saturday, the woman visited the office's clinic and was examined by the defendant family practitioner, Dr. P. She presented with a shaved head and a neurosurgical scar on the left side of her head; she complained of headache and some blurred or double vision. She gave Dr. P. a list of medications and medical records (in Spanish) from the Mexican hospital.

Findings on her physical examination were normal. She was instructed to return to see Dr. M., and she did so at the clinic on the following Monday. She repeated her complaints of double vision, headache, and fatigue. Dr. M. charged his office staff with attempting to have the Mexican records translated and to arrange for a neurosurgery appointment.

The patient was ultimately scheduled for head CT and an office visit with a neurosurgeon six days later. The day after those arrangements were made, however, she experienced a massive brain bleed and died.

According to the plaintiff, the surgeons in Mexico drained the blood from the initial bleed but did not detect its source—an aneurysm in the subarachnoid space. The plaintiff alleged that the defendants should have hospitalized the decedent immediately upon her return from Mexico or sent her for an immediate neurosurgical consult. Had the decedent undergone CT immediately, it was argued, the aneurysm would have been detected, surgery would have been performed, and she would have survived.

The defendants argued that the neurosurgical follow-up was out of their area of expertise and that they made appropriate arrangements for the decedent to be seen by a neurosurgeon. They maintained that the decedent appeared stable and seemed to be improving and that it was possible that the fatal bleed was not related to the first bleed. The defendants also claimed that definitive treatment should have been given in Mexico.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned.

Ultrasound Misplaced, Diagnosis Delayed for a Year

In March 2003 at age 2, the minor plaintiff was admitted to the defendant hospital under the care of the defendant pediatric urologist, who was treating her for bilateral vesicoureteral urinary reflux and frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs). The defendant surgically reimplanted both ureters to stop urinary reflux. The toddler was discharged to home in her parents' care two days after the procedure.

The child continued to experience UTIs. Renal ultrasonography revealed a blockage in the left ureter, but the ultrasound was lost by the defendant hospital. Results were never conveyed to the ordering physicians, who failed to follow up to obtain them.

In April 2004, the defendant urologist diagnosed the condition and determined that it had gone untreated for a year. Repeat renal ultrasonography demonstrated the blockage, and a nuclear renal scan confirmed that the child's left kidney was no longer functioning at all as a result of urinary backup. In addition to losing all function of the left kidney, the child has compromised function in the right kidney. She is expected to require dialysis in the future and eventually kidney transplantation.

A $9.75 million settlement was reached.

Complications of Undiagnosed Diverticulitis

A 62-year-old woman visited the defendant internist with complaints of abdominal pressure, poor appetite, weakness, and dizziness. Her medical history included hypertension, diverticulitis, hysterectomy, and tonsillectomy.

The defendant ordered a chest x-ray, complete blood count, and urinalysis. After reviewing test results, the defendant made a diagnosis of urinary tract infection and prescribed ceftriaxone by intramuscular injection and oral ciprofloxacin.

After receiving the first injection of ceftriaxone, the patient called the defendant's office, complaining of increased discomfort. She requested admission to the hospital, which was allegedly refused by a member of the office staff. The following day, the plaintiff was transported to the hospital by ambulance with complaints of left lower quadrant pain, intermittent for one week and worsening that evening. The plaintiff reported no nausea or diarrhea but was belching.

The emergency department physician identified tender palpation in the abdomen with no rebounding and decreased bowel sounds. The defendant internist's answering service was contacted, and the covering physician ordered admission with a diagnosis of diverticulitis. CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed evidence of free air under the hemidiaphragm, ascites, and phlegmonous reaction; the results also suggested diverticulitis with perforation in the rectosigmoid region and inflammatory changes.

Five hours later, the patient was taken to surgery for an exploratory laparotomy and colostomy to address the apparent perforated diverticulum. Her immediate postoperative course included profound hypotension with narrow-complex tachycardia. These developments, allegedly resulting from abdominal sepsis due to the delay in diagnosing the perforated diverticulum, necessitated pressors and dopamine.

Soon thereafter, the patient developed right-leg ischemia. She underwent embolectomy and thrombectomy to the right common femoral artery and the superficial femoral artery, with repair to the right profunda by use of a saphenous vein patch angioplasty. Two days later, the patient was taken to surgery for an above-knee amputation.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant was negligent in failing to recognize early manifestations of diverticulitis and to order CT or MRl. The plaintiff also claimed that she should have been hospitalized when she requested admission.

The defendant maintained that the patient's history and the laboratory study results suggested that she had the flu or a urinary tract infection and that hospitalization was not needed. The defendant also maintained that when he called for a surgical consultation, the surgeon did not arrive for four and one-half hours.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned. A motion for a new trial was pending.

Surgery Continued Despite Patient's Deteriorating Condition

In 1986, the patient, then age 8, was found to be mildly mentally retarded (IQ, 59 to 70). He also had paranoid schizophrenia, causing him to hear voices in his head. The patient lived with his sister, who served as his guardian.

At age 19, the patient was scheduled to undergo surgery to correct curvature of the spine. The operation was to be performed by Dr. R., assisted by Dr. M. and by an anesthesiologist, Dr. L.

About one hour into the surgery, the patient began to manifest decreased urinary output with no known cause, but the procedure continued. About 90 minutes later, an equipment malfunction made it impossible for the medical team to monitor the patient's nerve responses and oxygen levels, but the surgery still continued.

At some point during the surgery, the patient had an unexplained blood loss and his serum calcium level dropped below normal. He also experienced a loss of oxygen to the brain, then went into cardiac arrest. At that point, the surgery was discontinued, uncompleted.

The patient was comatose for several days, during which he displayed prolonged seizure activity. After regaining consciousness, he remained in the hospital for nearly four weeks before being transferred to another facility for rehabilitation.

The patient continues to have symptoms of various neurologic problems, including athetoid-choreiform movement, which causes a general loss of balance and muscular control and cognitive deficits, which make him unable to communicate.

The plaintiff claimed that the surgery should have been stopped when the problems arose. The plaintiff also claimed that Dr. R. should have ordered intraoperative lab work when the plaintiff's condition deteriorated.

The matter was ultimately tried against Drs. R. and L. only. They denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a $3 million verdict was returned.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Was Follow-Up Adequate After Neurosurgery in Cancún?

Shortly after arriving in Mexico for a brief stay, a 44-year-old woman collapsed in the customs area. She was taken to a hospital in Cancún, where she underwent emergency neurosurgery for a brain bleed. After several days of hospitalization, she was stabilized and returned to Michigan with instructions to see her family clinician.

Her appointment was delayed by an ice storm, which interrupted power to the office of the defendant internist, Dr. M. That Saturday, the woman visited the office's clinic and was examined by the defendant family practitioner, Dr. P. She presented with a shaved head and a neurosurgical scar on the left side of her head; she complained of headache and some blurred or double vision. She gave Dr. P. a list of medications and medical records (in Spanish) from the Mexican hospital.

Findings on her physical examination were normal. She was instructed to return to see Dr. M., and she did so at the clinic on the following Monday. She repeated her complaints of double vision, headache, and fatigue. Dr. M. charged his office staff with attempting to have the Mexican records translated and to arrange for a neurosurgery appointment.

The patient was ultimately scheduled for head CT and an office visit with a neurosurgeon six days later. The day after those arrangements were made, however, she experienced a massive brain bleed and died.

According to the plaintiff, the surgeons in Mexico drained the blood from the initial bleed but did not detect its source—an aneurysm in the subarachnoid space. The plaintiff alleged that the defendants should have hospitalized the decedent immediately upon her return from Mexico or sent her for an immediate neurosurgical consult. Had the decedent undergone CT immediately, it was argued, the aneurysm would have been detected, surgery would have been performed, and she would have survived.

The defendants argued that the neurosurgical follow-up was out of their area of expertise and that they made appropriate arrangements for the decedent to be seen by a neurosurgeon. They maintained that the decedent appeared stable and seemed to be improving and that it was possible that the fatal bleed was not related to the first bleed. The defendants also claimed that definitive treatment should have been given in Mexico.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned.

Ultrasound Misplaced, Diagnosis Delayed for a Year

In March 2003 at age 2, the minor plaintiff was admitted to the defendant hospital under the care of the defendant pediatric urologist, who was treating her for bilateral vesicoureteral urinary reflux and frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs). The defendant surgically reimplanted both ureters to stop urinary reflux. The toddler was discharged to home in her parents' care two days after the procedure.

The child continued to experience UTIs. Renal ultrasonography revealed a blockage in the left ureter, but the ultrasound was lost by the defendant hospital. Results were never conveyed to the ordering physicians, who failed to follow up to obtain them.

In April 2004, the defendant urologist diagnosed the condition and determined that it had gone untreated for a year. Repeat renal ultrasonography demonstrated the blockage, and a nuclear renal scan confirmed that the child's left kidney was no longer functioning at all as a result of urinary backup. In addition to losing all function of the left kidney, the child has compromised function in the right kidney. She is expected to require dialysis in the future and eventually kidney transplantation.

A $9.75 million settlement was reached.

Complications of Undiagnosed Diverticulitis

A 62-year-old woman visited the defendant internist with complaints of abdominal pressure, poor appetite, weakness, and dizziness. Her medical history included hypertension, diverticulitis, hysterectomy, and tonsillectomy.

The defendant ordered a chest x-ray, complete blood count, and urinalysis. After reviewing test results, the defendant made a diagnosis of urinary tract infection and prescribed ceftriaxone by intramuscular injection and oral ciprofloxacin.

After receiving the first injection of ceftriaxone, the patient called the defendant's office, complaining of increased discomfort. She requested admission to the hospital, which was allegedly refused by a member of the office staff. The following day, the plaintiff was transported to the hospital by ambulance with complaints of left lower quadrant pain, intermittent for one week and worsening that evening. The plaintiff reported no nausea or diarrhea but was belching.

The emergency department physician identified tender palpation in the abdomen with no rebounding and decreased bowel sounds. The defendant internist's answering service was contacted, and the covering physician ordered admission with a diagnosis of diverticulitis. CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed evidence of free air under the hemidiaphragm, ascites, and phlegmonous reaction; the results also suggested diverticulitis with perforation in the rectosigmoid region and inflammatory changes.

Five hours later, the patient was taken to surgery for an exploratory laparotomy and colostomy to address the apparent perforated diverticulum. Her immediate postoperative course included profound hypotension with narrow-complex tachycardia. These developments, allegedly resulting from abdominal sepsis due to the delay in diagnosing the perforated diverticulum, necessitated pressors and dopamine.

Soon thereafter, the patient developed right-leg ischemia. She underwent embolectomy and thrombectomy to the right common femoral artery and the superficial femoral artery, with repair to the right profunda by use of a saphenous vein patch angioplasty. Two days later, the patient was taken to surgery for an above-knee amputation.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant was negligent in failing to recognize early manifestations of diverticulitis and to order CT or MRl. The plaintiff also claimed that she should have been hospitalized when she requested admission.

The defendant maintained that the patient's history and the laboratory study results suggested that she had the flu or a urinary tract infection and that hospitalization was not needed. The defendant also maintained that when he called for a surgical consultation, the surgeon did not arrive for four and one-half hours.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned. A motion for a new trial was pending.

Surgery Continued Despite Patient's Deteriorating Condition

In 1986, the patient, then age 8, was found to be mildly mentally retarded (IQ, 59 to 70). He also had paranoid schizophrenia, causing him to hear voices in his head. The patient lived with his sister, who served as his guardian.

At age 19, the patient was scheduled to undergo surgery to correct curvature of the spine. The operation was to be performed by Dr. R., assisted by Dr. M. and by an anesthesiologist, Dr. L.

About one hour into the surgery, the patient began to manifest decreased urinary output with no known cause, but the procedure continued. About 90 minutes later, an equipment malfunction made it impossible for the medical team to monitor the patient's nerve responses and oxygen levels, but the surgery still continued.

At some point during the surgery, the patient had an unexplained blood loss and his serum calcium level dropped below normal. He also experienced a loss of oxygen to the brain, then went into cardiac arrest. At that point, the surgery was discontinued, uncompleted.

The patient was comatose for several days, during which he displayed prolonged seizure activity. After regaining consciousness, he remained in the hospital for nearly four weeks before being transferred to another facility for rehabilitation.

The patient continues to have symptoms of various neurologic problems, including athetoid-choreiform movement, which causes a general loss of balance and muscular control and cognitive deficits, which make him unable to communicate.

The plaintiff claimed that the surgery should have been stopped when the problems arose. The plaintiff also claimed that Dr. R. should have ordered intraoperative lab work when the plaintiff's condition deteriorated.

The matter was ultimately tried against Drs. R. and L. only. They denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a $3 million verdict was returned.

Ensuring Patient Safety and Quality Care

In addition to the longstanding issues of patients’ lack of access to health care and the increasing costs of that care, there continue to be concerns about the safety and quality of care being delivered in the United States. This is especially true as more information on the nature and extent of errors in health care has been brought to the forefront.

Since 1990, the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) has been collecting information on health care practitioners, including NPs and PAs, with regard to disciplinary actions such as monetary judgments (both by settlement and jury decision), loss of licensure, and limitation of practice. Over the years, PAs and NPs have experienced increased liability (mostly as a result of their expanding scope of practice), greater patient care responsibilities, and more autonomy. However, according to an article in the March 20, 2000, edition of Medical Economics, “Judging from the actual number of malpractice cases settled, PAs and NPs are in court much less often than their doctor colleagues.”

Information from the NPDB, in fact, reveals that NPs and PAs still incur a remarkably low rate of malpractice judgments. Moreover, anecdotal data support the possibility that hiring a PA or NP may even reduce the risk of malpractice liability.

The Health Care Quality Improvement Act, passed by Congress in 1986, requires that all malpractice payments made on behalf of any clinician who is licensed, registered, or certified by the state must be reported to the NPDB. Since the data bank began collecting statistics, it has recorded a total of 235,797 paid claims for all physicians of every type, with an average paid claim (inflation adjusted) of $282,782. During that same period, the NPDB recorded a total of 1,130 paid claims for PAs, with an average paid claim of $86,568. The total number of NP claims was 470, but average claim data were not available.

You can get some perspective on these data by keeping in mind that in 2006, there were 633,000 physicians, 125,000 NPs, and 70,000 PAs practicing in the US. There are five physicians for every NP in the country; nine physicians for every PA. Can we surmise then that the number of physician-related paid claims should be five times that of NP-related paid claims and nine times that of PA-related claims?

In reality, the number of physician-related paid claims approaches 100 times that of PA-related paid claims. A further disparity is noted when mean losses are compared: The 2006 mean physician-related losses are 33% higher than PA-related losses ($312,000 for physicians vs $234,000 for PAs). Unfortunately, it should be noted that the mean rate for PAs is approaching that of the physician.

Another way of examining the differences among the malpractice experiences of NPs, PAs, and physicians is to calculate how many providers of each type exist for each malpractice paid claim. Data from 2006 show that one claim was paid for every 2.68 physicians, compared to one for every 210.43 NPs and one for every 619.5 PAs.

It is true that we don’t know for sure how accurate the data reported to the NPDB are. Variations in NP practice—whether independent, collaborative, or phys-ician-supervised—exist from state to state, which may affect the reliability of the data. Also, differences exist among states in the way NPs are licensed. In some states, an NP is licensed as a nurse while in others he or she would be licensed as an NP, which can similarly alter the reporting. And because prescriptive authority by PAs and NPs varies from state to state, it may be true that states are not on an equal footing when it comes to their settlement of claims against NPs or PAs.

Lastly, NPs are reported to the NPDB separately from certified nurse midwives (596 paid claims) and advanced practice nurses (1,181 claims including CRNAs). If they were reported as one group, that would also affect the numbers.

It must be remembered that each health care provider is responsible for his or her own negligent acts. Even if you are a dependent practitioner with a supervising physician who is responsible for your actions, that does not exonerate you from the risk of individual liability.

To win a negligence case and recover damages from an NP or PA, a patient must prove three things: that the PA or NP owed the patient a duty of care, that he or she breached that duty, and that the patient was harmed as a result of the NP’s or PA’s action or failure to act. Conduct that may lead to liability includes failure to properly diagnose, failure to refer, exceeding one’s scope of practice, negligent monitoring, failure to question a physician’s abnormal order, or failure to properly follow up.

In most cases, PAs and NPs are covered under their employer’s policy. In spite of that, they may still be liable for their own negligence and for all or part of a plaintiff’s award or settlement. It is important, in my experience, that NPs and PAs maintain their own personal medical liability insurance.

There are plenty of articles and handbooks that discuss methods to avoid medical liability, such as the Physician Assistant Legal Handbook by Aspen Health Law and Compliance Center and The Advanced Practice Nurse’s Legal Handbook by Rebecca F. Cady, RNC, BSN, JD. But in my opinion, they all boil down to the following basic principles:

• Know and understand your scope of practice under state law.

• Know and understand your hospital or institutional policies.

• Know and understand the importance of communicating honestly with your patients and your supervising or collaborating physician.

Ensuring patient safety and improving quality of care are steadfast goals for all NPs and PAs. We need to continue our discussions on best practices for preventing medical errors as well as finding ways to remove barriers to effective practice. I would love to hear from you about these matters. Please e-mail me at [email protected].

In addition to the longstanding issues of patients’ lack of access to health care and the increasing costs of that care, there continue to be concerns about the safety and quality of care being delivered in the United States. This is especially true as more information on the nature and extent of errors in health care has been brought to the forefront.

Since 1990, the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) has been collecting information on health care practitioners, including NPs and PAs, with regard to disciplinary actions such as monetary judgments (both by settlement and jury decision), loss of licensure, and limitation of practice. Over the years, PAs and NPs have experienced increased liability (mostly as a result of their expanding scope of practice), greater patient care responsibilities, and more autonomy. However, according to an article in the March 20, 2000, edition of Medical Economics, “Judging from the actual number of malpractice cases settled, PAs and NPs are in court much less often than their doctor colleagues.”

Information from the NPDB, in fact, reveals that NPs and PAs still incur a remarkably low rate of malpractice judgments. Moreover, anecdotal data support the possibility that hiring a PA or NP may even reduce the risk of malpractice liability.

The Health Care Quality Improvement Act, passed by Congress in 1986, requires that all malpractice payments made on behalf of any clinician who is licensed, registered, or certified by the state must be reported to the NPDB. Since the data bank began collecting statistics, it has recorded a total of 235,797 paid claims for all physicians of every type, with an average paid claim (inflation adjusted) of $282,782. During that same period, the NPDB recorded a total of 1,130 paid claims for PAs, with an average paid claim of $86,568. The total number of NP claims was 470, but average claim data were not available.

You can get some perspective on these data by keeping in mind that in 2006, there were 633,000 physicians, 125,000 NPs, and 70,000 PAs practicing in the US. There are five physicians for every NP in the country; nine physicians for every PA. Can we surmise then that the number of physician-related paid claims should be five times that of NP-related paid claims and nine times that of PA-related claims?

In reality, the number of physician-related paid claims approaches 100 times that of PA-related paid claims. A further disparity is noted when mean losses are compared: The 2006 mean physician-related losses are 33% higher than PA-related losses ($312,000 for physicians vs $234,000 for PAs). Unfortunately, it should be noted that the mean rate for PAs is approaching that of the physician.

Another way of examining the differences among the malpractice experiences of NPs, PAs, and physicians is to calculate how many providers of each type exist for each malpractice paid claim. Data from 2006 show that one claim was paid for every 2.68 physicians, compared to one for every 210.43 NPs and one for every 619.5 PAs.

It is true that we don’t know for sure how accurate the data reported to the NPDB are. Variations in NP practice—whether independent, collaborative, or phys-ician-supervised—exist from state to state, which may affect the reliability of the data. Also, differences exist among states in the way NPs are licensed. In some states, an NP is licensed as a nurse while in others he or she would be licensed as an NP, which can similarly alter the reporting. And because prescriptive authority by PAs and NPs varies from state to state, it may be true that states are not on an equal footing when it comes to their settlement of claims against NPs or PAs.

Lastly, NPs are reported to the NPDB separately from certified nurse midwives (596 paid claims) and advanced practice nurses (1,181 claims including CRNAs). If they were reported as one group, that would also affect the numbers.

It must be remembered that each health care provider is responsible for his or her own negligent acts. Even if you are a dependent practitioner with a supervising physician who is responsible for your actions, that does not exonerate you from the risk of individual liability.

To win a negligence case and recover damages from an NP or PA, a patient must prove three things: that the PA or NP owed the patient a duty of care, that he or she breached that duty, and that the patient was harmed as a result of the NP’s or PA’s action or failure to act. Conduct that may lead to liability includes failure to properly diagnose, failure to refer, exceeding one’s scope of practice, negligent monitoring, failure to question a physician’s abnormal order, or failure to properly follow up.

In most cases, PAs and NPs are covered under their employer’s policy. In spite of that, they may still be liable for their own negligence and for all or part of a plaintiff’s award or settlement. It is important, in my experience, that NPs and PAs maintain their own personal medical liability insurance.

There are plenty of articles and handbooks that discuss methods to avoid medical liability, such as the Physician Assistant Legal Handbook by Aspen Health Law and Compliance Center and The Advanced Practice Nurse’s Legal Handbook by Rebecca F. Cady, RNC, BSN, JD. But in my opinion, they all boil down to the following basic principles:

• Know and understand your scope of practice under state law.

• Know and understand your hospital or institutional policies.

• Know and understand the importance of communicating honestly with your patients and your supervising or collaborating physician.

Ensuring patient safety and improving quality of care are steadfast goals for all NPs and PAs. We need to continue our discussions on best practices for preventing medical errors as well as finding ways to remove barriers to effective practice. I would love to hear from you about these matters. Please e-mail me at [email protected].

In addition to the longstanding issues of patients’ lack of access to health care and the increasing costs of that care, there continue to be concerns about the safety and quality of care being delivered in the United States. This is especially true as more information on the nature and extent of errors in health care has been brought to the forefront.

Since 1990, the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) has been collecting information on health care practitioners, including NPs and PAs, with regard to disciplinary actions such as monetary judgments (both by settlement and jury decision), loss of licensure, and limitation of practice. Over the years, PAs and NPs have experienced increased liability (mostly as a result of their expanding scope of practice), greater patient care responsibilities, and more autonomy. However, according to an article in the March 20, 2000, edition of Medical Economics, “Judging from the actual number of malpractice cases settled, PAs and NPs are in court much less often than their doctor colleagues.”

Information from the NPDB, in fact, reveals that NPs and PAs still incur a remarkably low rate of malpractice judgments. Moreover, anecdotal data support the possibility that hiring a PA or NP may even reduce the risk of malpractice liability.

The Health Care Quality Improvement Act, passed by Congress in 1986, requires that all malpractice payments made on behalf of any clinician who is licensed, registered, or certified by the state must be reported to the NPDB. Since the data bank began collecting statistics, it has recorded a total of 235,797 paid claims for all physicians of every type, with an average paid claim (inflation adjusted) of $282,782. During that same period, the NPDB recorded a total of 1,130 paid claims for PAs, with an average paid claim of $86,568. The total number of NP claims was 470, but average claim data were not available.

You can get some perspective on these data by keeping in mind that in 2006, there were 633,000 physicians, 125,000 NPs, and 70,000 PAs practicing in the US. There are five physicians for every NP in the country; nine physicians for every PA. Can we surmise then that the number of physician-related paid claims should be five times that of NP-related paid claims and nine times that of PA-related claims?

In reality, the number of physician-related paid claims approaches 100 times that of PA-related paid claims. A further disparity is noted when mean losses are compared: The 2006 mean physician-related losses are 33% higher than PA-related losses ($312,000 for physicians vs $234,000 for PAs). Unfortunately, it should be noted that the mean rate for PAs is approaching that of the physician.

Another way of examining the differences among the malpractice experiences of NPs, PAs, and physicians is to calculate how many providers of each type exist for each malpractice paid claim. Data from 2006 show that one claim was paid for every 2.68 physicians, compared to one for every 210.43 NPs and one for every 619.5 PAs.

It is true that we don’t know for sure how accurate the data reported to the NPDB are. Variations in NP practice—whether independent, collaborative, or phys-ician-supervised—exist from state to state, which may affect the reliability of the data. Also, differences exist among states in the way NPs are licensed. In some states, an NP is licensed as a nurse while in others he or she would be licensed as an NP, which can similarly alter the reporting. And because prescriptive authority by PAs and NPs varies from state to state, it may be true that states are not on an equal footing when it comes to their settlement of claims against NPs or PAs.

Lastly, NPs are reported to the NPDB separately from certified nurse midwives (596 paid claims) and advanced practice nurses (1,181 claims including CRNAs). If they were reported as one group, that would also affect the numbers.

It must be remembered that each health care provider is responsible for his or her own negligent acts. Even if you are a dependent practitioner with a supervising physician who is responsible for your actions, that does not exonerate you from the risk of individual liability.

To win a negligence case and recover damages from an NP or PA, a patient must prove three things: that the PA or NP owed the patient a duty of care, that he or she breached that duty, and that the patient was harmed as a result of the NP’s or PA’s action or failure to act. Conduct that may lead to liability includes failure to properly diagnose, failure to refer, exceeding one’s scope of practice, negligent monitoring, failure to question a physician’s abnormal order, or failure to properly follow up.

In most cases, PAs and NPs are covered under their employer’s policy. In spite of that, they may still be liable for their own negligence and for all or part of a plaintiff’s award or settlement. It is important, in my experience, that NPs and PAs maintain their own personal medical liability insurance.

There are plenty of articles and handbooks that discuss methods to avoid medical liability, such as the Physician Assistant Legal Handbook by Aspen Health Law and Compliance Center and The Advanced Practice Nurse’s Legal Handbook by Rebecca F. Cady, RNC, BSN, JD. But in my opinion, they all boil down to the following basic principles:

• Know and understand your scope of practice under state law.

• Know and understand your hospital or institutional policies.

• Know and understand the importance of communicating honestly with your patients and your supervising or collaborating physician.

Ensuring patient safety and improving quality of care are steadfast goals for all NPs and PAs. We need to continue our discussions on best practices for preventing medical errors as well as finding ways to remove barriers to effective practice. I would love to hear from you about these matters. Please e-mail me at [email protected].

Malpractice minute

Could a patient’s violent act

have been prevented?

THE PATIENT. A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

CASE FACTS. The patient killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26.

THE VICTIM’S FAMILY’S CLAIM. The death would not have occurred if the patient had been civilly committed or heavily medicated.

THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH AUTHORITY’S DEFENSE. The violent act was unforeseeable, and the patient was compliant with treatment. The victim’s mother should not have left the disabled woman alone with the patient.

Submit your verdict and find out how the court ruled. Click on “Have more to say about this topic?” to comment.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Could a patient’s violent act

have been prevented?

THE PATIENT. A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

CASE FACTS. The patient killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26.

THE VICTIM’S FAMILY’S CLAIM. The death would not have occurred if the patient had been civilly committed or heavily medicated.

THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH AUTHORITY’S DEFENSE. The violent act was unforeseeable, and the patient was compliant with treatment. The victim’s mother should not have left the disabled woman alone with the patient.

Submit your verdict and find out how the court ruled. Click on “Have more to say about this topic?” to comment.

Could a patient’s violent act

have been prevented?

THE PATIENT. A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type.

CASE FACTS. The patient killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26.

THE VICTIM’S FAMILY’S CLAIM. The death would not have occurred if the patient had been civilly committed or heavily medicated.

THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH AUTHORITY’S DEFENSE. The violent act was unforeseeable, and the patient was compliant with treatment. The victim’s mother should not have left the disabled woman alone with the patient.

Submit your verdict and find out how the court ruled. Click on “Have more to say about this topic?” to comment.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Violence risk: Is clinical judgment enough?

Dear Dr. Mossman:

Multiple studies support the reliability and validity of actuarial measures—such as the Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management (HCR-20) risk assessment scheme—to assess violence risk, whereas physicians’ clinical judgment is highly variable. Should clinicians use actuarial measures to assess a patient’s risk of violence? Could it be considered negligent not to use actuarial measures?—Submitted by “Dr. S”

In the 30 years since the Tarasoff decision—which held that psychiatrists have a duty to protect individuals who are being threatened with bodily harm by a patient1—assessing patients’ risk of future violence has become an accepted part of mental health practice.2 Dr. S has asked 2 sophisticated questions about risk assessment. The short answer is that although so-called “actuarial” techniques for assessing risk are valuable, psychiatrists who do not use them are not practicing negligently. To explain why, this article discusses:

- the difference between “clinical” and “actuarial” judgment

- the HCR-20’s strengths and weaknesses

- actuarial measures and negligence.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online marketplace of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Clinical vs actuarial judgment

In the 1970s and 1980s, mental health professionals believed they could not accurately predict violence.3 We now know this is not correct. Since the 1990s, when researchers adopted better methods for gauging the accuracy of risk assessments,4-6 research has shown that mental health clinicians can assess dangerousness with clearly-better-than-chance accuracy, whether the assessment covers just the next few days, several months, or years.4

Over the same period, psychologists recognized that when it comes to making predictions, clinical judgment—making predictions by putting together information in one’s head—often is inferior to using simple formulae derived from empirically demonstrated relationships between data and outcome.7 This approach—“actuarial” judgment—is how insurance companies use data to calculate risk.

By the late 1990s, psychologists had developed actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs)8 that could accurately rank the likelihood of various forms of violence. Table 1 lists some well-known ARAIs and the populations for which they were designed. In clinical practice, psychiatrists usually focus on risk posed by psychiatric patients. The HCR-209 was designed to help evaluate this type of risk.

Table 1

Examples of actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs)

| ARAI | Risk assessed |

|---|---|

| HCR-209 | Violence in psychiatric populations, such as formerly hospitalized patients |

| Classification Of Violence Risk (COVR) | Violence by civil psychiatric patients following discharge into the community |

| Violence Risk Assessment Guide (VRAG) | Violent recidivism by formerly incarcerated offenders |

| Static-99 | Recidivism by sex offenders |

HCR-20’s pros and cons

The HCR-20 has 20 items:

- 10 concerning the patient’s history

- 5 related to clinical factors

- 5 that deal with risk management (Table 2).

To use the HCR-20 as an exercise of true actuarial judgment, you would base your opinion of a patient’s risk of violence solely on the HCR-20 score, without regard for other patient factors. However, the HCR-20’s developers think this approach “may be unreasonable, unethical, and illegal.”9 One reason is that the HCR-20 omits obvious signs of potential violence, such as a clearly stated threat with unambiguous intent to act.

For example, if a patient is doing well in the hospital (and has a low score on HCR-20 clinical items), a psychiatrist might assume the patient will cause few problems after discharge. But if the risk management items generate a high score, the psychiatrist should realize that these factors raise the patient’s violence risk and may require additional intervention—perhaps a different type of community placement or special effort to help the patient follow up with out-patient treatment.

Table 2

Items from the Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management (HCR-20)

| Historical items | Clinical items | Risk management items |

|---|---|---|

| H1 Previous violence | C1 Lack of insight | R1 Plans lack feasibility |

| H2 Young age at first incident | C2 Negative attitudes | R2 Exposure to destabilizers |

| H3 Relationship instability | C3 Active symptoms of major mental illness | R3 Lack of personal support |

| H4 Employment problems | C4 Impulsivity | R4 Noncompliance with remediation attempts |

| H5 Substance use problems | C5 Unresponsive to treatment | R5 Stress |

| H6 Major mental illness | ||

| H7 Psychopathy | ||

| H8 Early maladjustment | ||

| H9 Personality disorder | ||

| H10 Prior supervision failure | ||

| Score each item 0, 1, or 2, depending on how closely the patient matches the described characteristic. For example, when scoring item C3 (active symptoms of major mental illness), a patient gets 0 for “no active symptoms,” 1 for “possible/less serious active symptoms,” or 2 for “definite/serious active symptoms.” An individual can receive a total HCR-20 score of 0 to 40. The higher the score, the higher likelihood of violence in the coming months. | ||

| Source: Reprinted with permission from Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, Hart SD. HCR-20: assessing risk for violence, version 2. Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada: Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute; 1997 | ||

Is not using ARAIs negligent?

Some writers believe that using ARAIs should12 or may soon13 become the standard of care. Why, then, do psychiatrists seldom use ARAIs in their clinical work? Partly it is because clinicians rarely receive adequate training in assessing violence risk or the science supporting it. After a 5-hour training module featuring the HCR-20, psychiatry residents could better identify factors that affect violence risk, organize their reasoning, and come up with risk management strategies.2

Psychiatrists may have other reasons for not using ARAIs that make clinical sense. Although ARAIs can rank individuals’ violence risk, the probabilities of violence associated with each rank aren’t substantial enough to justify differences in management.14 Scientifically, it’s interesting to know that we can separate patients into groups with “low” (9%) and “high” (49%) risks of violence.15 But would you want to manage these patients differently? Most psychiatrists probably would not feel comfortable ignoring a 9% risk of violence.

To avoid negligence, psychiatrists need only “exercise the skill, knowledge, and care normally possessed and exercised by other members of their profession.”17 Psychiatrists seldom use ARAIs,12 so failing to use them cannot constitute malpractice. As Simon points out, a practicing psychiatrist’s role is to treat patients, not predict violence. He concludes, “at this time, the standard of care does not require the average or reasonable psychiatrist to use actuarial assessment instruments in the evaluation and treatment of potentially violent patients.”16

1. Tarasoff vs Regents of the University of California, 551 P. 2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

2. McNiel DE, Chamberlain JR, Weaver CM, et al. Impact of clinical training on violence risk assessment. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:195-200.

3. Monahan J. The clinical prediction of violent behavior. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1981.

4. Mossman D. Assessing predictions of violence: being accurate about accuracy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:783-92.

5. Rice ME, Harris GT. Violent recidivism: assessing predictive validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:737-48.

6. Gardner W, Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Clinical versus actuarial predictions of violence in patients with mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:602-9.

7. Dawes RM, Faust D, Meehl PE. Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science 1989;243:1668-74.

8. Hart SD, Michie C, Cooke DJ. Precision of actuarial risk assessment instruments: evaluating the ‘margins of error’ of group v. individual predictions of violence. Brit J Psychiatry 2007;190:60-5.

9. Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, Hart SD. HCR-20: assessing risk for violence, version 2. Burnaby, British Columbia: Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute; 1997.

10. Quinsey VL, Harris GT, Rice ME, Cormier CA. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006.

11. Hanson RK, Morton-Bourgon KE. The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: a meta-analysis. Ottawa, Canada: Public Safety Canada; 2007. Available at: http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/res/cor/rep/_fl/crp2007-01-en.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2008.

12. Swanson JW. Preventing the unpredicted: managing violence risk in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:191-3.

13. Lamberg L. New tools aid violence risk assessment. JAMA 2007;298(5):499-501.

14. Mossman D. Commentary: assessing the risk of violence—are “accurate” predictions useful? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2000;28:272-81.

15. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, et al. An actuarial model of violence risk assessment for persons with mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2005;56:810-15.

16. Simon RI. The myth of “imminent” violence in psychiatry and the law. Univ Cincinnati L Rev 2006;75:631-43.

17. Dobbs DB. The law of torts. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2000:269.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

Multiple studies support the reliability and validity of actuarial measures—such as the Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management (HCR-20) risk assessment scheme—to assess violence risk, whereas physicians’ clinical judgment is highly variable. Should clinicians use actuarial measures to assess a patient’s risk of violence? Could it be considered negligent not to use actuarial measures?—Submitted by “Dr. S”

In the 30 years since the Tarasoff decision—which held that psychiatrists have a duty to protect individuals who are being threatened with bodily harm by a patient1—assessing patients’ risk of future violence has become an accepted part of mental health practice.2 Dr. S has asked 2 sophisticated questions about risk assessment. The short answer is that although so-called “actuarial” techniques for assessing risk are valuable, psychiatrists who do not use them are not practicing negligently. To explain why, this article discusses:

- the difference between “clinical” and “actuarial” judgment

- the HCR-20’s strengths and weaknesses

- actuarial measures and negligence.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online marketplace of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Clinical vs actuarial judgment

In the 1970s and 1980s, mental health professionals believed they could not accurately predict violence.3 We now know this is not correct. Since the 1990s, when researchers adopted better methods for gauging the accuracy of risk assessments,4-6 research has shown that mental health clinicians can assess dangerousness with clearly-better-than-chance accuracy, whether the assessment covers just the next few days, several months, or years.4

Over the same period, psychologists recognized that when it comes to making predictions, clinical judgment—making predictions by putting together information in one’s head—often is inferior to using simple formulae derived from empirically demonstrated relationships between data and outcome.7 This approach—“actuarial” judgment—is how insurance companies use data to calculate risk.

By the late 1990s, psychologists had developed actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs)8 that could accurately rank the likelihood of various forms of violence. Table 1 lists some well-known ARAIs and the populations for which they were designed. In clinical practice, psychiatrists usually focus on risk posed by psychiatric patients. The HCR-209 was designed to help evaluate this type of risk.

Table 1

Examples of actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs)

| ARAI | Risk assessed |

|---|---|

| HCR-209 | Violence in psychiatric populations, such as formerly hospitalized patients |

| Classification Of Violence Risk (COVR) | Violence by civil psychiatric patients following discharge into the community |

| Violence Risk Assessment Guide (VRAG) | Violent recidivism by formerly incarcerated offenders |

| Static-99 | Recidivism by sex offenders |

HCR-20’s pros and cons

The HCR-20 has 20 items:

- 10 concerning the patient’s history

- 5 related to clinical factors

- 5 that deal with risk management (Table 2).

To use the HCR-20 as an exercise of true actuarial judgment, you would base your opinion of a patient’s risk of violence solely on the HCR-20 score, without regard for other patient factors. However, the HCR-20’s developers think this approach “may be unreasonable, unethical, and illegal.”9 One reason is that the HCR-20 omits obvious signs of potential violence, such as a clearly stated threat with unambiguous intent to act.

For example, if a patient is doing well in the hospital (and has a low score on HCR-20 clinical items), a psychiatrist might assume the patient will cause few problems after discharge. But if the risk management items generate a high score, the psychiatrist should realize that these factors raise the patient’s violence risk and may require additional intervention—perhaps a different type of community placement or special effort to help the patient follow up with out-patient treatment.

Table 2

Items from the Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management (HCR-20)

| Historical items | Clinical items | Risk management items |

|---|---|---|

| H1 Previous violence | C1 Lack of insight | R1 Plans lack feasibility |

| H2 Young age at first incident | C2 Negative attitudes | R2 Exposure to destabilizers |

| H3 Relationship instability | C3 Active symptoms of major mental illness | R3 Lack of personal support |

| H4 Employment problems | C4 Impulsivity | R4 Noncompliance with remediation attempts |

| H5 Substance use problems | C5 Unresponsive to treatment | R5 Stress |

| H6 Major mental illness | ||

| H7 Psychopathy | ||

| H8 Early maladjustment | ||

| H9 Personality disorder | ||

| H10 Prior supervision failure | ||

| Score each item 0, 1, or 2, depending on how closely the patient matches the described characteristic. For example, when scoring item C3 (active symptoms of major mental illness), a patient gets 0 for “no active symptoms,” 1 for “possible/less serious active symptoms,” or 2 for “definite/serious active symptoms.” An individual can receive a total HCR-20 score of 0 to 40. The higher the score, the higher likelihood of violence in the coming months. | ||

| Source: Reprinted with permission from Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, Hart SD. HCR-20: assessing risk for violence, version 2. Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada: Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute; 1997 | ||

Is not using ARAIs negligent?

Some writers believe that using ARAIs should12 or may soon13 become the standard of care. Why, then, do psychiatrists seldom use ARAIs in their clinical work? Partly it is because clinicians rarely receive adequate training in assessing violence risk or the science supporting it. After a 5-hour training module featuring the HCR-20, psychiatry residents could better identify factors that affect violence risk, organize their reasoning, and come up with risk management strategies.2

Psychiatrists may have other reasons for not using ARAIs that make clinical sense. Although ARAIs can rank individuals’ violence risk, the probabilities of violence associated with each rank aren’t substantial enough to justify differences in management.14 Scientifically, it’s interesting to know that we can separate patients into groups with “low” (9%) and “high” (49%) risks of violence.15 But would you want to manage these patients differently? Most psychiatrists probably would not feel comfortable ignoring a 9% risk of violence.

To avoid negligence, psychiatrists need only “exercise the skill, knowledge, and care normally possessed and exercised by other members of their profession.”17 Psychiatrists seldom use ARAIs,12 so failing to use them cannot constitute malpractice. As Simon points out, a practicing psychiatrist’s role is to treat patients, not predict violence. He concludes, “at this time, the standard of care does not require the average or reasonable psychiatrist to use actuarial assessment instruments in the evaluation and treatment of potentially violent patients.”16

Dear Dr. Mossman:

Multiple studies support the reliability and validity of actuarial measures—such as the Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management (HCR-20) risk assessment scheme—to assess violence risk, whereas physicians’ clinical judgment is highly variable. Should clinicians use actuarial measures to assess a patient’s risk of violence? Could it be considered negligent not to use actuarial measures?—Submitted by “Dr. S”

In the 30 years since the Tarasoff decision—which held that psychiatrists have a duty to protect individuals who are being threatened with bodily harm by a patient1—assessing patients’ risk of future violence has become an accepted part of mental health practice.2 Dr. S has asked 2 sophisticated questions about risk assessment. The short answer is that although so-called “actuarial” techniques for assessing risk are valuable, psychiatrists who do not use them are not practicing negligently. To explain why, this article discusses:

- the difference between “clinical” and “actuarial” judgment

- the HCR-20’s strengths and weaknesses

- actuarial measures and negligence.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online marketplace of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Clinical vs actuarial judgment

In the 1970s and 1980s, mental health professionals believed they could not accurately predict violence.3 We now know this is not correct. Since the 1990s, when researchers adopted better methods for gauging the accuracy of risk assessments,4-6 research has shown that mental health clinicians can assess dangerousness with clearly-better-than-chance accuracy, whether the assessment covers just the next few days, several months, or years.4

Over the same period, psychologists recognized that when it comes to making predictions, clinical judgment—making predictions by putting together information in one’s head—often is inferior to using simple formulae derived from empirically demonstrated relationships between data and outcome.7 This approach—“actuarial” judgment—is how insurance companies use data to calculate risk.

By the late 1990s, psychologists had developed actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs)8 that could accurately rank the likelihood of various forms of violence. Table 1 lists some well-known ARAIs and the populations for which they were designed. In clinical practice, psychiatrists usually focus on risk posed by psychiatric patients. The HCR-209 was designed to help evaluate this type of risk.

Table 1

Examples of actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs)

| ARAI | Risk assessed |

|---|---|

| HCR-209 | Violence in psychiatric populations, such as formerly hospitalized patients |

| Classification Of Violence Risk (COVR) | Violence by civil psychiatric patients following discharge into the community |

| Violence Risk Assessment Guide (VRAG) | Violent recidivism by formerly incarcerated offenders |

| Static-99 | Recidivism by sex offenders |

HCR-20’s pros and cons

The HCR-20 has 20 items:

- 10 concerning the patient’s history

- 5 related to clinical factors

- 5 that deal with risk management (Table 2).

To use the HCR-20 as an exercise of true actuarial judgment, you would base your opinion of a patient’s risk of violence solely on the HCR-20 score, without regard for other patient factors. However, the HCR-20’s developers think this approach “may be unreasonable, unethical, and illegal.”9 One reason is that the HCR-20 omits obvious signs of potential violence, such as a clearly stated threat with unambiguous intent to act.

For example, if a patient is doing well in the hospital (and has a low score on HCR-20 clinical items), a psychiatrist might assume the patient will cause few problems after discharge. But if the risk management items generate a high score, the psychiatrist should realize that these factors raise the patient’s violence risk and may require additional intervention—perhaps a different type of community placement or special effort to help the patient follow up with out-patient treatment.

Table 2

Items from the Historical, Clinical, and Risk Management (HCR-20)

| Historical items | Clinical items | Risk management items |

|---|---|---|

| H1 Previous violence | C1 Lack of insight | R1 Plans lack feasibility |

| H2 Young age at first incident | C2 Negative attitudes | R2 Exposure to destabilizers |

| H3 Relationship instability | C3 Active symptoms of major mental illness | R3 Lack of personal support |

| H4 Employment problems | C4 Impulsivity | R4 Noncompliance with remediation attempts |

| H5 Substance use problems | C5 Unresponsive to treatment | R5 Stress |

| H6 Major mental illness | ||

| H7 Psychopathy | ||

| H8 Early maladjustment | ||

| H9 Personality disorder | ||

| H10 Prior supervision failure | ||

| Score each item 0, 1, or 2, depending on how closely the patient matches the described characteristic. For example, when scoring item C3 (active symptoms of major mental illness), a patient gets 0 for “no active symptoms,” 1 for “possible/less serious active symptoms,” or 2 for “definite/serious active symptoms.” An individual can receive a total HCR-20 score of 0 to 40. The higher the score, the higher likelihood of violence in the coming months. | ||

| Source: Reprinted with permission from Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, Hart SD. HCR-20: assessing risk for violence, version 2. Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada: Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute; 1997 | ||

Is not using ARAIs negligent?

Some writers believe that using ARAIs should12 or may soon13 become the standard of care. Why, then, do psychiatrists seldom use ARAIs in their clinical work? Partly it is because clinicians rarely receive adequate training in assessing violence risk or the science supporting it. After a 5-hour training module featuring the HCR-20, psychiatry residents could better identify factors that affect violence risk, organize their reasoning, and come up with risk management strategies.2

Psychiatrists may have other reasons for not using ARAIs that make clinical sense. Although ARAIs can rank individuals’ violence risk, the probabilities of violence associated with each rank aren’t substantial enough to justify differences in management.14 Scientifically, it’s interesting to know that we can separate patients into groups with “low” (9%) and “high” (49%) risks of violence.15 But would you want to manage these patients differently? Most psychiatrists probably would not feel comfortable ignoring a 9% risk of violence.

To avoid negligence, psychiatrists need only “exercise the skill, knowledge, and care normally possessed and exercised by other members of their profession.”17 Psychiatrists seldom use ARAIs,12 so failing to use them cannot constitute malpractice. As Simon points out, a practicing psychiatrist’s role is to treat patients, not predict violence. He concludes, “at this time, the standard of care does not require the average or reasonable psychiatrist to use actuarial assessment instruments in the evaluation and treatment of potentially violent patients.”16

1. Tarasoff vs Regents of the University of California, 551 P. 2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

2. McNiel DE, Chamberlain JR, Weaver CM, et al. Impact of clinical training on violence risk assessment. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:195-200.

3. Monahan J. The clinical prediction of violent behavior. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1981.

4. Mossman D. Assessing predictions of violence: being accurate about accuracy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:783-92.

5. Rice ME, Harris GT. Violent recidivism: assessing predictive validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:737-48.

6. Gardner W, Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Clinical versus actuarial predictions of violence in patients with mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:602-9.

7. Dawes RM, Faust D, Meehl PE. Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science 1989;243:1668-74.

8. Hart SD, Michie C, Cooke DJ. Precision of actuarial risk assessment instruments: evaluating the ‘margins of error’ of group v. individual predictions of violence. Brit J Psychiatry 2007;190:60-5.

9. Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, Hart SD. HCR-20: assessing risk for violence, version 2. Burnaby, British Columbia: Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute; 1997.

10. Quinsey VL, Harris GT, Rice ME, Cormier CA. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006.

11. Hanson RK, Morton-Bourgon KE. The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: a meta-analysis. Ottawa, Canada: Public Safety Canada; 2007. Available at: http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/res/cor/rep/_fl/crp2007-01-en.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2008.

12. Swanson JW. Preventing the unpredicted: managing violence risk in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:191-3.

13. Lamberg L. New tools aid violence risk assessment. JAMA 2007;298(5):499-501.

14. Mossman D. Commentary: assessing the risk of violence—are “accurate” predictions useful? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2000;28:272-81.

15. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, et al. An actuarial model of violence risk assessment for persons with mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2005;56:810-15.

16. Simon RI. The myth of “imminent” violence in psychiatry and the law. Univ Cincinnati L Rev 2006;75:631-43.

17. Dobbs DB. The law of torts. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2000:269.

1. Tarasoff vs Regents of the University of California, 551 P. 2d 334 (Cal. 1976).

2. McNiel DE, Chamberlain JR, Weaver CM, et al. Impact of clinical training on violence risk assessment. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:195-200.

3. Monahan J. The clinical prediction of violent behavior. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1981.

4. Mossman D. Assessing predictions of violence: being accurate about accuracy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:783-92.

5. Rice ME, Harris GT. Violent recidivism: assessing predictive validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:737-48.

6. Gardner W, Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Clinical versus actuarial predictions of violence in patients with mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:602-9.

7. Dawes RM, Faust D, Meehl PE. Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science 1989;243:1668-74.

8. Hart SD, Michie C, Cooke DJ. Precision of actuarial risk assessment instruments: evaluating the ‘margins of error’ of group v. individual predictions of violence. Brit J Psychiatry 2007;190:60-5.

9. Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, Hart SD. HCR-20: assessing risk for violence, version 2. Burnaby, British Columbia: Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute; 1997.

10. Quinsey VL, Harris GT, Rice ME, Cormier CA. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006.

11. Hanson RK, Morton-Bourgon KE. The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: a meta-analysis. Ottawa, Canada: Public Safety Canada; 2007. Available at: http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/res/cor/rep/_fl/crp2007-01-en.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2008.

12. Swanson JW. Preventing the unpredicted: managing violence risk in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:191-3.

13. Lamberg L. New tools aid violence risk assessment. JAMA 2007;298(5):499-501.

14. Mossman D. Commentary: assessing the risk of violence—are “accurate” predictions useful? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2000;28:272-81.

15. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, et al. An actuarial model of violence risk assessment for persons with mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2005;56:810-15.

16. Simon RI. The myth of “imminent” violence in psychiatry and the law. Univ Cincinnati L Rev 2006;75:631-43.

17. Dobbs DB. The law of torts. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2000:269.

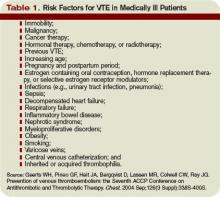

What is the best choice for prophylaxis against VTE in medical inpatients?

Case

A 76-year-old gentleman is admitted for progressively worsening dyspnea, cough, and bilateral leg edema. Upon admission, his blood pressure is 150/90 mm/Hg, pulse 90 beats per minute, and respiration is 24 per minute.

Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distension, bilateral crackles, S3 gallop, and 2+ bilateral lower extremity edema. The chest radiograph shows cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema. He is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure and starts aggressive medical therapy.

Overview

Approximately 2 million cases of deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) occur annually in the United States. Based on studies utilizing ventilation-perfusion scanning, half these patients likely have a silent pulmonary embolism (PE); of these, approximately 250,000 die.

The spectrum of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes DVT and PE, can vary from being asymptomatic to sudden death. Autopsy studies suggest a leading cause of sudden death in hospitalized medical patients is often a PE. There also are sequelae, such as chronic pulmonary hypertension, occurring in approximately 5% of PE cases, and post-thrombotic syndrome, occurring in approximately 40% of patients with DVT at two years.1