User login

Survey Says...

For a moment, put yourself in a hospital administrator’s shoes—more specifically, those of a hospital administrator who is looking to hire a handful of new hospitalists. You know the job duties you need to fill. You know what qualifications a candidate should have. You even know the hours you need covered.

But there remains one gaping hole in the job description: compensation.

—Tex Landis, MD, FHM, SHM Practice Analysis Committee chairman

The question of how much to offer hospitalists who are in the market for a new job—and, conversely, how much they can demand—has bedeviled the specialty since its inception. And, as HM continues its exponential growth throughout the national healthcare landscape, the devil is in the details. How does an administrator or HM group leader take into account years of experience in compensation? Do nocturnists demand more or less? What about shift work?

That picture will get clearer in 2010, thanks to a new partnership between SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). Together, the two groups are embarking on an ambitious new research project to provide hospital administrators and hospitalist practice leaders a comprehensive—and credible—set of data on hospitalist compensation and productivity. The data will be published in an annual report issued jointly by SHM and MGMA.

Previously, data available to hospitalists about the state of HM were researched and published by SHM every two years. The new partnership builds on the society’s original work by using questions similar to the SHM survey, but will add MGMA’s authority on such subjects and analytical firepower.

Big Changes

The SHM-MGMA partnership will provide two major improvements to HM and hospital administrators: the annual publication of results and MGMA’s stamp of approval to the research.

New data every year is a welcome change for David Friar, MD, president of Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan in Traverse City. “Things in hospital medicine continue to change very quickly. By the time new data is published, it’s already a few months old,” Dr. Friar says. “Doing the survey on the annual basis will be very useful to us.”

Credibility from an independent source, which MGMA has cultivated through nearly 80 years of organizational performance research, should go a long way when hospitalists are negotiating with hospital administrators. The original SHM-produced survey carried major weight within HM; this new collaborative survey will build on that success by expanding the survey’s credibility in hospitals across the country. Hospital administrators have been turning to MGMA data for other management metrics for years; now they will be able to use the same trusted source for decisions about their HM programs.

“When we negotiate with hospital administrators, we use the current data as a benchmark for comparison,” Dr. Friar says. “[Administrators] are much more familiar with MGMA. The marriage of the two should be very helpful.”

The combination also helps alleviate some confusion in the marketplace, which was the goal of both organizations, according to Crystal Taylor, MGMA’s assistant director for survey operations. “Our survey has been the gold standard for compensation but hasn’t had a high degree of detail around hospitalist-specific metrics,” Taylor says. “SHM’s research has always had more detail in this area because it was more specialized.”

Subtle Change

Although the research will be published in mid-2010, SHM members will notice changes long before then. In fact, many hospitalists already have taken advantage of the partnership, says Leslie Flores, MHA, the director of SHM’s Practice Management Institute.

“SHM and MGMA have already done a number of collaborative things,” she says. “We’ve presented a webinar together, and SHM is now offering MGMA books on its online store.”

In the near future, SHM and MGMA members can expect to hear from both organizations. MGMA has invited SHM to present at MGMA’s national conference, and MGMA will be presenting at HM09 in Washington, D.C., in April. For other SHM members, their first contact with MGMA will be through the survey, which will begin in January, according to Flores. SHM will issue e-mail invitations to group leaders to participate in the survey. The link in the e-mail will take members to MGMA’s data-gathering Web site. SHM and MGMA will present webinars and other educational tools to help practice administrators and others understand the new survey instrument.

Enthusiastic Partner

Like any other promising relationship, both parties are animated about the potential the partnership has for the future. MGMA hopes working with SHM brings them into a new and growing marketplace.

“The hospitalist market is new to us, which is another benefit of the relationship,” says Steve Hellebush, an MGMA vice president who is responsible for the association’s work with SHM. “By being able to interact with experts at SHM who really understand that segment of the healthcare industry, we’re learning more about it. As we learn more, we’ll find more opportunities.”

Both groups agree the joint project will better define the marketplace for hospitalist jobs and compensation. Those familiar with the challenges of administrating a hospitalist practice know that those changes will have a deep impact on healthcare.

“This is about giving our members the best, most valuable information available,” says Tex Landis, MD, FHM, chairman of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. “By enabling hospital medicine groups to make better decisions, this partnership will ultimately translate into better care for patients.”TH

Brandon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

Chapter Updates

Arizona

The Arizona chapter had a well-attended meeting Aug. 13 at Ruth’s Chris Steak House in Phoenix. Hospitalists, medical students, and several chief medical officers from local hospitals listened as chapter president Tochukwu S. Nwafor, MD, of Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix, gave a lecture on VTE prophylaxis in the hospitalized patient. He discussed the pivotal role hospitalists provide in treating this medical condition and the leadership they can provide because of their accessibility and knowledge. The France Foundation sponsored the discussion.

After the lecture, VTE prevention strategies were discussed. The chapter agreed to continue such work on VTE in the future.

Chapter business was discussed after the lecture. Plans for the coming year include another weekend continuing medical education (CME) activity on pertinent hospitalist topics. The chapter also plans to continue its outreach to such outlying areas as Tucson and Flagstaff.

Northern Nevada

The Northern Nevada chapter met Aug. 18 at the Washow Grill in Reno. The 38 attendees represented four HM groups. Chapter president Phil Goodman provided an overview of SHM and its resources, meetings, fellowship, and membership costs. The chapter elected officers based on nominations submitted via e-mail and nominations at the chapter meeting. A written ballot was conducted, and the officers elected for 2009-2010 are:

- President: Sukumar Gargya, MD, Renown Hospitalists;

- VP Logistics/Secretary (president-elect): Levente Levai, MD, president, Sierra Hospitalists;

- VP Membership: Lynda Malloy, director, NNMC EmCare;

- VP Education: Nagesh Gullapalli, UNSOM Hospitalists; and

- VP Projects: Jose Aguirre, president, Lake Tahoe Regional Hospitalists.

The next meeting is Nov. 3. The agenda includes a talk on “Difficult Decisions in Afib Management.” The chapter also plans to resume a journal club that aims to publish two to three times per year, starting in late November or early December.

Primary Piedmont Triad Chapter

The Primary Piedmont Triad SHM chapter had its first meeting June 23 at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C. The meeting was hosted by the Wake Forest Inpatient Physicians group of Wake Forest University Health Sciences and sponsored by Schering-Plough. The chapter had dissolved a few years ago, so this meeting was a “meet and greet.”

Ten hospitalists attended the meeting, which included the selection of new officers. There was no special presentation. The evening was spent socializing, reviewing survey results and deciding on a new vision for the chapter. The group was extremely enthusiastic and excited about the future of HM, even in the current economic climate and uncertainty surrounding healthcare reform. The chapter is planning to have quarterly meetings.

Southern Illinois

The Southern Illinois chapter met July 23 at the Hilton Garden Inn in O’Fallon. The meeting was attended by 16 hospitalists from four HM groups. Theresa Murphy, a PharmD in neuro ICU at Barnes Jewish Hospital, presented on “Euvolemic and Hypervolemic Hyponatremia and AVP Antagonishm with Vapris.” The event was a success; attendees were pleased with the topics that were discussed.

Chicago

SHM’s Chicago chapter hosted a dinner July 29 at the Reel Club in Oakbrook, Ill. The speaker was Gary Shaer, MD, professor of medicine at Rush University. The topic for Dr. Shaer’s presentation was “Managing Patients with ACS in the Acute Setting: An Interventional Cardiologist’s Perspective.” The talk generated an excellent discussion. Various HM topics were debated, including healthcare reform and the hospitalist.

The chapter also welcomed new members and newly designated Fellows in Hospital Medicine. Attendees included hospitalists from Advocate Medical Group, Loyola Medical Center, Resurrection Hospitals, Northwestern Medical Center, and Signature Group.

The next chapter meeting will be in November; the date and location are to be announced. For more information about the Chicago chapter, contact Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM, at [email protected], or Ana Nowell, MD, FHM, at [email protected].

For a moment, put yourself in a hospital administrator’s shoes—more specifically, those of a hospital administrator who is looking to hire a handful of new hospitalists. You know the job duties you need to fill. You know what qualifications a candidate should have. You even know the hours you need covered.

But there remains one gaping hole in the job description: compensation.

—Tex Landis, MD, FHM, SHM Practice Analysis Committee chairman

The question of how much to offer hospitalists who are in the market for a new job—and, conversely, how much they can demand—has bedeviled the specialty since its inception. And, as HM continues its exponential growth throughout the national healthcare landscape, the devil is in the details. How does an administrator or HM group leader take into account years of experience in compensation? Do nocturnists demand more or less? What about shift work?

That picture will get clearer in 2010, thanks to a new partnership between SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). Together, the two groups are embarking on an ambitious new research project to provide hospital administrators and hospitalist practice leaders a comprehensive—and credible—set of data on hospitalist compensation and productivity. The data will be published in an annual report issued jointly by SHM and MGMA.

Previously, data available to hospitalists about the state of HM were researched and published by SHM every two years. The new partnership builds on the society’s original work by using questions similar to the SHM survey, but will add MGMA’s authority on such subjects and analytical firepower.

Big Changes

The SHM-MGMA partnership will provide two major improvements to HM and hospital administrators: the annual publication of results and MGMA’s stamp of approval to the research.

New data every year is a welcome change for David Friar, MD, president of Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan in Traverse City. “Things in hospital medicine continue to change very quickly. By the time new data is published, it’s already a few months old,” Dr. Friar says. “Doing the survey on the annual basis will be very useful to us.”

Credibility from an independent source, which MGMA has cultivated through nearly 80 years of organizational performance research, should go a long way when hospitalists are negotiating with hospital administrators. The original SHM-produced survey carried major weight within HM; this new collaborative survey will build on that success by expanding the survey’s credibility in hospitals across the country. Hospital administrators have been turning to MGMA data for other management metrics for years; now they will be able to use the same trusted source for decisions about their HM programs.

“When we negotiate with hospital administrators, we use the current data as a benchmark for comparison,” Dr. Friar says. “[Administrators] are much more familiar with MGMA. The marriage of the two should be very helpful.”

The combination also helps alleviate some confusion in the marketplace, which was the goal of both organizations, according to Crystal Taylor, MGMA’s assistant director for survey operations. “Our survey has been the gold standard for compensation but hasn’t had a high degree of detail around hospitalist-specific metrics,” Taylor says. “SHM’s research has always had more detail in this area because it was more specialized.”

Subtle Change

Although the research will be published in mid-2010, SHM members will notice changes long before then. In fact, many hospitalists already have taken advantage of the partnership, says Leslie Flores, MHA, the director of SHM’s Practice Management Institute.

“SHM and MGMA have already done a number of collaborative things,” she says. “We’ve presented a webinar together, and SHM is now offering MGMA books on its online store.”

In the near future, SHM and MGMA members can expect to hear from both organizations. MGMA has invited SHM to present at MGMA’s national conference, and MGMA will be presenting at HM09 in Washington, D.C., in April. For other SHM members, their first contact with MGMA will be through the survey, which will begin in January, according to Flores. SHM will issue e-mail invitations to group leaders to participate in the survey. The link in the e-mail will take members to MGMA’s data-gathering Web site. SHM and MGMA will present webinars and other educational tools to help practice administrators and others understand the new survey instrument.

Enthusiastic Partner

Like any other promising relationship, both parties are animated about the potential the partnership has for the future. MGMA hopes working with SHM brings them into a new and growing marketplace.

“The hospitalist market is new to us, which is another benefit of the relationship,” says Steve Hellebush, an MGMA vice president who is responsible for the association’s work with SHM. “By being able to interact with experts at SHM who really understand that segment of the healthcare industry, we’re learning more about it. As we learn more, we’ll find more opportunities.”

Both groups agree the joint project will better define the marketplace for hospitalist jobs and compensation. Those familiar with the challenges of administrating a hospitalist practice know that those changes will have a deep impact on healthcare.

“This is about giving our members the best, most valuable information available,” says Tex Landis, MD, FHM, chairman of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. “By enabling hospital medicine groups to make better decisions, this partnership will ultimately translate into better care for patients.”TH

Brandon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

Chapter Updates

Arizona

The Arizona chapter had a well-attended meeting Aug. 13 at Ruth’s Chris Steak House in Phoenix. Hospitalists, medical students, and several chief medical officers from local hospitals listened as chapter president Tochukwu S. Nwafor, MD, of Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix, gave a lecture on VTE prophylaxis in the hospitalized patient. He discussed the pivotal role hospitalists provide in treating this medical condition and the leadership they can provide because of their accessibility and knowledge. The France Foundation sponsored the discussion.

After the lecture, VTE prevention strategies were discussed. The chapter agreed to continue such work on VTE in the future.

Chapter business was discussed after the lecture. Plans for the coming year include another weekend continuing medical education (CME) activity on pertinent hospitalist topics. The chapter also plans to continue its outreach to such outlying areas as Tucson and Flagstaff.

Northern Nevada

The Northern Nevada chapter met Aug. 18 at the Washow Grill in Reno. The 38 attendees represented four HM groups. Chapter president Phil Goodman provided an overview of SHM and its resources, meetings, fellowship, and membership costs. The chapter elected officers based on nominations submitted via e-mail and nominations at the chapter meeting. A written ballot was conducted, and the officers elected for 2009-2010 are:

- President: Sukumar Gargya, MD, Renown Hospitalists;

- VP Logistics/Secretary (president-elect): Levente Levai, MD, president, Sierra Hospitalists;

- VP Membership: Lynda Malloy, director, NNMC EmCare;

- VP Education: Nagesh Gullapalli, UNSOM Hospitalists; and

- VP Projects: Jose Aguirre, president, Lake Tahoe Regional Hospitalists.

The next meeting is Nov. 3. The agenda includes a talk on “Difficult Decisions in Afib Management.” The chapter also plans to resume a journal club that aims to publish two to three times per year, starting in late November or early December.

Primary Piedmont Triad Chapter

The Primary Piedmont Triad SHM chapter had its first meeting June 23 at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C. The meeting was hosted by the Wake Forest Inpatient Physicians group of Wake Forest University Health Sciences and sponsored by Schering-Plough. The chapter had dissolved a few years ago, so this meeting was a “meet and greet.”

Ten hospitalists attended the meeting, which included the selection of new officers. There was no special presentation. The evening was spent socializing, reviewing survey results and deciding on a new vision for the chapter. The group was extremely enthusiastic and excited about the future of HM, even in the current economic climate and uncertainty surrounding healthcare reform. The chapter is planning to have quarterly meetings.

Southern Illinois

The Southern Illinois chapter met July 23 at the Hilton Garden Inn in O’Fallon. The meeting was attended by 16 hospitalists from four HM groups. Theresa Murphy, a PharmD in neuro ICU at Barnes Jewish Hospital, presented on “Euvolemic and Hypervolemic Hyponatremia and AVP Antagonishm with Vapris.” The event was a success; attendees were pleased with the topics that were discussed.

Chicago

SHM’s Chicago chapter hosted a dinner July 29 at the Reel Club in Oakbrook, Ill. The speaker was Gary Shaer, MD, professor of medicine at Rush University. The topic for Dr. Shaer’s presentation was “Managing Patients with ACS in the Acute Setting: An Interventional Cardiologist’s Perspective.” The talk generated an excellent discussion. Various HM topics were debated, including healthcare reform and the hospitalist.

The chapter also welcomed new members and newly designated Fellows in Hospital Medicine. Attendees included hospitalists from Advocate Medical Group, Loyola Medical Center, Resurrection Hospitals, Northwestern Medical Center, and Signature Group.

The next chapter meeting will be in November; the date and location are to be announced. For more information about the Chicago chapter, contact Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM, at [email protected], or Ana Nowell, MD, FHM, at [email protected].

For a moment, put yourself in a hospital administrator’s shoes—more specifically, those of a hospital administrator who is looking to hire a handful of new hospitalists. You know the job duties you need to fill. You know what qualifications a candidate should have. You even know the hours you need covered.

But there remains one gaping hole in the job description: compensation.

—Tex Landis, MD, FHM, SHM Practice Analysis Committee chairman

The question of how much to offer hospitalists who are in the market for a new job—and, conversely, how much they can demand—has bedeviled the specialty since its inception. And, as HM continues its exponential growth throughout the national healthcare landscape, the devil is in the details. How does an administrator or HM group leader take into account years of experience in compensation? Do nocturnists demand more or less? What about shift work?

That picture will get clearer in 2010, thanks to a new partnership between SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). Together, the two groups are embarking on an ambitious new research project to provide hospital administrators and hospitalist practice leaders a comprehensive—and credible—set of data on hospitalist compensation and productivity. The data will be published in an annual report issued jointly by SHM and MGMA.

Previously, data available to hospitalists about the state of HM were researched and published by SHM every two years. The new partnership builds on the society’s original work by using questions similar to the SHM survey, but will add MGMA’s authority on such subjects and analytical firepower.

Big Changes

The SHM-MGMA partnership will provide two major improvements to HM and hospital administrators: the annual publication of results and MGMA’s stamp of approval to the research.

New data every year is a welcome change for David Friar, MD, president of Hospitalists of Northwest Michigan in Traverse City. “Things in hospital medicine continue to change very quickly. By the time new data is published, it’s already a few months old,” Dr. Friar says. “Doing the survey on the annual basis will be very useful to us.”

Credibility from an independent source, which MGMA has cultivated through nearly 80 years of organizational performance research, should go a long way when hospitalists are negotiating with hospital administrators. The original SHM-produced survey carried major weight within HM; this new collaborative survey will build on that success by expanding the survey’s credibility in hospitals across the country. Hospital administrators have been turning to MGMA data for other management metrics for years; now they will be able to use the same trusted source for decisions about their HM programs.

“When we negotiate with hospital administrators, we use the current data as a benchmark for comparison,” Dr. Friar says. “[Administrators] are much more familiar with MGMA. The marriage of the two should be very helpful.”

The combination also helps alleviate some confusion in the marketplace, which was the goal of both organizations, according to Crystal Taylor, MGMA’s assistant director for survey operations. “Our survey has been the gold standard for compensation but hasn’t had a high degree of detail around hospitalist-specific metrics,” Taylor says. “SHM’s research has always had more detail in this area because it was more specialized.”

Subtle Change

Although the research will be published in mid-2010, SHM members will notice changes long before then. In fact, many hospitalists already have taken advantage of the partnership, says Leslie Flores, MHA, the director of SHM’s Practice Management Institute.

“SHM and MGMA have already done a number of collaborative things,” she says. “We’ve presented a webinar together, and SHM is now offering MGMA books on its online store.”

In the near future, SHM and MGMA members can expect to hear from both organizations. MGMA has invited SHM to present at MGMA’s national conference, and MGMA will be presenting at HM09 in Washington, D.C., in April. For other SHM members, their first contact with MGMA will be through the survey, which will begin in January, according to Flores. SHM will issue e-mail invitations to group leaders to participate in the survey. The link in the e-mail will take members to MGMA’s data-gathering Web site. SHM and MGMA will present webinars and other educational tools to help practice administrators and others understand the new survey instrument.

Enthusiastic Partner

Like any other promising relationship, both parties are animated about the potential the partnership has for the future. MGMA hopes working with SHM brings them into a new and growing marketplace.

“The hospitalist market is new to us, which is another benefit of the relationship,” says Steve Hellebush, an MGMA vice president who is responsible for the association’s work with SHM. “By being able to interact with experts at SHM who really understand that segment of the healthcare industry, we’re learning more about it. As we learn more, we’ll find more opportunities.”

Both groups agree the joint project will better define the marketplace for hospitalist jobs and compensation. Those familiar with the challenges of administrating a hospitalist practice know that those changes will have a deep impact on healthcare.

“This is about giving our members the best, most valuable information available,” says Tex Landis, MD, FHM, chairman of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. “By enabling hospital medicine groups to make better decisions, this partnership will ultimately translate into better care for patients.”TH

Brandon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

Chapter Updates

Arizona

The Arizona chapter had a well-attended meeting Aug. 13 at Ruth’s Chris Steak House in Phoenix. Hospitalists, medical students, and several chief medical officers from local hospitals listened as chapter president Tochukwu S. Nwafor, MD, of Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix, gave a lecture on VTE prophylaxis in the hospitalized patient. He discussed the pivotal role hospitalists provide in treating this medical condition and the leadership they can provide because of their accessibility and knowledge. The France Foundation sponsored the discussion.

After the lecture, VTE prevention strategies were discussed. The chapter agreed to continue such work on VTE in the future.

Chapter business was discussed after the lecture. Plans for the coming year include another weekend continuing medical education (CME) activity on pertinent hospitalist topics. The chapter also plans to continue its outreach to such outlying areas as Tucson and Flagstaff.

Northern Nevada

The Northern Nevada chapter met Aug. 18 at the Washow Grill in Reno. The 38 attendees represented four HM groups. Chapter president Phil Goodman provided an overview of SHM and its resources, meetings, fellowship, and membership costs. The chapter elected officers based on nominations submitted via e-mail and nominations at the chapter meeting. A written ballot was conducted, and the officers elected for 2009-2010 are:

- President: Sukumar Gargya, MD, Renown Hospitalists;

- VP Logistics/Secretary (president-elect): Levente Levai, MD, president, Sierra Hospitalists;

- VP Membership: Lynda Malloy, director, NNMC EmCare;

- VP Education: Nagesh Gullapalli, UNSOM Hospitalists; and

- VP Projects: Jose Aguirre, president, Lake Tahoe Regional Hospitalists.

The next meeting is Nov. 3. The agenda includes a talk on “Difficult Decisions in Afib Management.” The chapter also plans to resume a journal club that aims to publish two to three times per year, starting in late November or early December.

Primary Piedmont Triad Chapter

The Primary Piedmont Triad SHM chapter had its first meeting June 23 at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C. The meeting was hosted by the Wake Forest Inpatient Physicians group of Wake Forest University Health Sciences and sponsored by Schering-Plough. The chapter had dissolved a few years ago, so this meeting was a “meet and greet.”

Ten hospitalists attended the meeting, which included the selection of new officers. There was no special presentation. The evening was spent socializing, reviewing survey results and deciding on a new vision for the chapter. The group was extremely enthusiastic and excited about the future of HM, even in the current economic climate and uncertainty surrounding healthcare reform. The chapter is planning to have quarterly meetings.

Southern Illinois

The Southern Illinois chapter met July 23 at the Hilton Garden Inn in O’Fallon. The meeting was attended by 16 hospitalists from four HM groups. Theresa Murphy, a PharmD in neuro ICU at Barnes Jewish Hospital, presented on “Euvolemic and Hypervolemic Hyponatremia and AVP Antagonishm with Vapris.” The event was a success; attendees were pleased with the topics that were discussed.

Chicago

SHM’s Chicago chapter hosted a dinner July 29 at the Reel Club in Oakbrook, Ill. The speaker was Gary Shaer, MD, professor of medicine at Rush University. The topic for Dr. Shaer’s presentation was “Managing Patients with ACS in the Acute Setting: An Interventional Cardiologist’s Perspective.” The talk generated an excellent discussion. Various HM topics were debated, including healthcare reform and the hospitalist.

The chapter also welcomed new members and newly designated Fellows in Hospital Medicine. Attendees included hospitalists from Advocate Medical Group, Loyola Medical Center, Resurrection Hospitals, Northwestern Medical Center, and Signature Group.

The next chapter meeting will be in November; the date and location are to be announced. For more information about the Chicago chapter, contact Aziz Ansari, DO, FHM, at [email protected], or Ana Nowell, MD, FHM, at [email protected].

Delay in Addressing Bleeding From Dialysis Access Site

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Delay in Addressing Bleeding From Dialysis Access Site

At age 73, a woman with a 20-year history of diabetes had been using prescribed insulin injections, but not consistently. She had undergone kidney dialysis for more than 10 years and had end-stage renal failure as well as several other comorbidities, including diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, hypertension, hepatitis B, and a history of knee surgery.

For 11 days before she was hospitalized in December 2004, the patient had experienced bleeding from the dialysis shunt access site in her right groin. This necessitated several emergency department (ED) visits leading to three hospitalizations. During the visit in question, the patient was seen by several physicians. Angioplasty and angiography were ordered in advance of anticipated removal of any occlusions from the shunt/graft site. Two days later, it was determined that the site should be examined and possibly revised, and surgery was scheduled for the following day. However, the patient experienced another bleed which led to a code blue; she did not survive.

The plaintiff alleged negligence by one of the physicians involved for failing to come to examine and treat the decedent’s shunt/graft site.

The defendant physician claimed that he had been consulted by phone by an ED physician and that he had not expected to see the decedent. When the defendant received a call two days later from one of the hospital nurses, he did not know why.

Defense also claimed that the decedent had wanted to keep the existing dialysis shunt/graft site in order to avoid a transition to peritoneal dialysis.

According to a published account, a confidential settlement was reached during trial.

“Moderate” Heart Defect Overlooked

One morning at work, a 37-year-old man experienced a lump in his throat, chest tightness, lightheadedness, and jaw pain. He contacted the defendant internist, who instructed the man to come to his office immediately. ECG results were normal, and after examining the patient, the internist determined that his symptoms had been induced by anxiety.

The next day, on the internist’s orders, the patient underwent ECG exercise stress testing, conducted by the defendant cardiologist. Results were interpreted as normal. A technetium Tc99m sestamibi nuclear scan confirmed a moderate defect in the left anterior descending chamber. Test results were mailed to the internist the following day.

The patient returned to work three days later and suffered a heart attack, collapsed, and was pronounced dead within one hour.

Plaintiffs for the decedent claimed that the internist should have diagnosed a heart attack and unstable angina and that further testing should have been performed during the initial visit to rule out a heart attack. The plaintiff also claimed that the decedent should have been sent to the ED and further argued that the nuclear test results should have been reported to the internist immediately, not mailed.

The defense maintained that no negligence was involved.

According to a published account, a jury found only the internist negligent and returned a $4 million verdict.

PSA Testing Conducted Only Once

In January 2005, a 49-year-old man presented to an internists’ group with urinary tract complaints, including frequent urination and a weak stream. He underwent a partial physical examination by the defendant internist, as well as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. The patient did not follow up for the remainder of the exam, but did make an appointment five months later for follow-up and a complete acute care visit.

At that time, the patient complained of rectal bleeding. The internist performed a digital rectal exam and noted an enlargement of the prostate. He did not suggest repeat PSA testing, nor did he follow up on the man’s previous urinary tract complaints. Instead, he referred him to a -gastroenterologist.

Late in 2005, the patient called the internist to inquire about blood work, including a test for diabetes. A fasting blood glucose test was ordered. Shortly thereafter, the man saw his internist, complaining of a sore throat. The internist ordered a series of laboratory tests, including lipid panels, a thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and liver enzyme tests. A PSA was neither ordered nor discussed.

In November 2007, the man was given a diagnosis of stage IV prostate cancer with metastasis to the brain, lungs, spine, and bony extremities. He did not respond to chemotherapy or to any of several other interventions.

At the time of arbitration, two weeks before the man’s death, he claimed that more regular PSA testing should have been ordered.

The defendant claimed that the original PSA test was sufficient and that even if a diagnosis had been made in May 2005, the man’s chance of survival would have been less than 50%.

The defendants were found liable, with an arbitration award of $3,547,030.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Delay in Addressing Bleeding From Dialysis Access Site

At age 73, a woman with a 20-year history of diabetes had been using prescribed insulin injections, but not consistently. She had undergone kidney dialysis for more than 10 years and had end-stage renal failure as well as several other comorbidities, including diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, hypertension, hepatitis B, and a history of knee surgery.

For 11 days before she was hospitalized in December 2004, the patient had experienced bleeding from the dialysis shunt access site in her right groin. This necessitated several emergency department (ED) visits leading to three hospitalizations. During the visit in question, the patient was seen by several physicians. Angioplasty and angiography were ordered in advance of anticipated removal of any occlusions from the shunt/graft site. Two days later, it was determined that the site should be examined and possibly revised, and surgery was scheduled for the following day. However, the patient experienced another bleed which led to a code blue; she did not survive.

The plaintiff alleged negligence by one of the physicians involved for failing to come to examine and treat the decedent’s shunt/graft site.

The defendant physician claimed that he had been consulted by phone by an ED physician and that he had not expected to see the decedent. When the defendant received a call two days later from one of the hospital nurses, he did not know why.

Defense also claimed that the decedent had wanted to keep the existing dialysis shunt/graft site in order to avoid a transition to peritoneal dialysis.

According to a published account, a confidential settlement was reached during trial.

“Moderate” Heart Defect Overlooked

One morning at work, a 37-year-old man experienced a lump in his throat, chest tightness, lightheadedness, and jaw pain. He contacted the defendant internist, who instructed the man to come to his office immediately. ECG results were normal, and after examining the patient, the internist determined that his symptoms had been induced by anxiety.

The next day, on the internist’s orders, the patient underwent ECG exercise stress testing, conducted by the defendant cardiologist. Results were interpreted as normal. A technetium Tc99m sestamibi nuclear scan confirmed a moderate defect in the left anterior descending chamber. Test results were mailed to the internist the following day.

The patient returned to work three days later and suffered a heart attack, collapsed, and was pronounced dead within one hour.

Plaintiffs for the decedent claimed that the internist should have diagnosed a heart attack and unstable angina and that further testing should have been performed during the initial visit to rule out a heart attack. The plaintiff also claimed that the decedent should have been sent to the ED and further argued that the nuclear test results should have been reported to the internist immediately, not mailed.

The defense maintained that no negligence was involved.

According to a published account, a jury found only the internist negligent and returned a $4 million verdict.

PSA Testing Conducted Only Once

In January 2005, a 49-year-old man presented to an internists’ group with urinary tract complaints, including frequent urination and a weak stream. He underwent a partial physical examination by the defendant internist, as well as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. The patient did not follow up for the remainder of the exam, but did make an appointment five months later for follow-up and a complete acute care visit.

At that time, the patient complained of rectal bleeding. The internist performed a digital rectal exam and noted an enlargement of the prostate. He did not suggest repeat PSA testing, nor did he follow up on the man’s previous urinary tract complaints. Instead, he referred him to a -gastroenterologist.

Late in 2005, the patient called the internist to inquire about blood work, including a test for diabetes. A fasting blood glucose test was ordered. Shortly thereafter, the man saw his internist, complaining of a sore throat. The internist ordered a series of laboratory tests, including lipid panels, a thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and liver enzyme tests. A PSA was neither ordered nor discussed.

In November 2007, the man was given a diagnosis of stage IV prostate cancer with metastasis to the brain, lungs, spine, and bony extremities. He did not respond to chemotherapy or to any of several other interventions.

At the time of arbitration, two weeks before the man’s death, he claimed that more regular PSA testing should have been ordered.

The defendant claimed that the original PSA test was sufficient and that even if a diagnosis had been made in May 2005, the man’s chance of survival would have been less than 50%.

The defendants were found liable, with an arbitration award of $3,547,030.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Delay in Addressing Bleeding From Dialysis Access Site

At age 73, a woman with a 20-year history of diabetes had been using prescribed insulin injections, but not consistently. She had undergone kidney dialysis for more than 10 years and had end-stage renal failure as well as several other comorbidities, including diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, hypertension, hepatitis B, and a history of knee surgery.

For 11 days before she was hospitalized in December 2004, the patient had experienced bleeding from the dialysis shunt access site in her right groin. This necessitated several emergency department (ED) visits leading to three hospitalizations. During the visit in question, the patient was seen by several physicians. Angioplasty and angiography were ordered in advance of anticipated removal of any occlusions from the shunt/graft site. Two days later, it was determined that the site should be examined and possibly revised, and surgery was scheduled for the following day. However, the patient experienced another bleed which led to a code blue; she did not survive.

The plaintiff alleged negligence by one of the physicians involved for failing to come to examine and treat the decedent’s shunt/graft site.

The defendant physician claimed that he had been consulted by phone by an ED physician and that he had not expected to see the decedent. When the defendant received a call two days later from one of the hospital nurses, he did not know why.

Defense also claimed that the decedent had wanted to keep the existing dialysis shunt/graft site in order to avoid a transition to peritoneal dialysis.

According to a published account, a confidential settlement was reached during trial.

“Moderate” Heart Defect Overlooked

One morning at work, a 37-year-old man experienced a lump in his throat, chest tightness, lightheadedness, and jaw pain. He contacted the defendant internist, who instructed the man to come to his office immediately. ECG results were normal, and after examining the patient, the internist determined that his symptoms had been induced by anxiety.

The next day, on the internist’s orders, the patient underwent ECG exercise stress testing, conducted by the defendant cardiologist. Results were interpreted as normal. A technetium Tc99m sestamibi nuclear scan confirmed a moderate defect in the left anterior descending chamber. Test results were mailed to the internist the following day.

The patient returned to work three days later and suffered a heart attack, collapsed, and was pronounced dead within one hour.

Plaintiffs for the decedent claimed that the internist should have diagnosed a heart attack and unstable angina and that further testing should have been performed during the initial visit to rule out a heart attack. The plaintiff also claimed that the decedent should have been sent to the ED and further argued that the nuclear test results should have been reported to the internist immediately, not mailed.

The defense maintained that no negligence was involved.

According to a published account, a jury found only the internist negligent and returned a $4 million verdict.

PSA Testing Conducted Only Once

In January 2005, a 49-year-old man presented to an internists’ group with urinary tract complaints, including frequent urination and a weak stream. He underwent a partial physical examination by the defendant internist, as well as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. The patient did not follow up for the remainder of the exam, but did make an appointment five months later for follow-up and a complete acute care visit.

At that time, the patient complained of rectal bleeding. The internist performed a digital rectal exam and noted an enlargement of the prostate. He did not suggest repeat PSA testing, nor did he follow up on the man’s previous urinary tract complaints. Instead, he referred him to a -gastroenterologist.

Late in 2005, the patient called the internist to inquire about blood work, including a test for diabetes. A fasting blood glucose test was ordered. Shortly thereafter, the man saw his internist, complaining of a sore throat. The internist ordered a series of laboratory tests, including lipid panels, a thyroid-stimulating hormone test, and liver enzyme tests. A PSA was neither ordered nor discussed.

In November 2007, the man was given a diagnosis of stage IV prostate cancer with metastasis to the brain, lungs, spine, and bony extremities. He did not respond to chemotherapy or to any of several other interventions.

At the time of arbitration, two weeks before the man’s death, he claimed that more regular PSA testing should have been ordered.

The defendant claimed that the original PSA test was sufficient and that even if a diagnosis had been made in May 2005, the man’s chance of survival would have been less than 50%.

The defendants were found liable, with an arbitration award of $3,547,030.

How do I keep my elderly patients from falling?

Case

An 85-year-old man with peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, a history of falls, and atrial fibrillation, which was being treated with warfarin, was admitted for a left transmetatarsal amputation. On postoperative day two, the patient slipped as he was getting out of bed to use the bathroom. He hit his head on his IV pole, and a CT scan demonstrated an acute right subdural hemorrhage. He subsequently suffered eight months of delirium before passing away at a skilled nursing facility. How could this incident have been prevented?

Background

Hospitalization represents a vulnerable time for elderly people. The presence of acute illness, an unfamiliar environment, and the frequent addition of new medications predispose an elderly patient to such iatrogenic hazards of hospitalization as falls, pressure ulcers, and delirium.1 Inpatient falls are the most common type of adverse hospital event, accounting for 70% of all inpatient accidents.2 Thirty percent to 40% of inpatient falls result in injury, with 4% to 6% resulting in serious harm.2 Interestingly, 55% of falls occur in patients 60 or younger, but 60% of falls resulting in moderate to severe injury occur in those 70 and older.3

A fall is a seminal event in the life of an elderly person. Even a fall without injury can initiate a vicious circle that begins with a fear of falling and is followed by a self-restriction of mobility, which commonly results in a decline in function.4 Functional decline in the elderly has been shown to predict mortality and nursing home placement.5

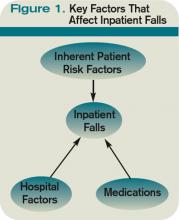

Inpatient falls are thought to occur via a complex interplay between medications, inherent patient susceptibilities, and hospital environmental hazards (see Figure 1, below).

Risk Factors

Medication prescription for the hospitalized elderly patient is perhaps the area where the hospitalist can have the greatest impact in reducing a patient’s fall risk. The most common medications thought to predispose community dwelling elders to falls are psychotropic drugs: neuroleptics, sedatives, hypnotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines.6

Limited studies of hospitalized patients indicate similar drugs as culprits. Passaro et al demonstrated that benzodiazepines with a half-life <24 hours (e.g., lorazepam and oxazepam) were strongly associated with falls even after correcting for multiple confounders.7 Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression revealed that the use of other psychotropic drugs in addition to benzodiazepines (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6–3.2) was strongly associated with an increased risk of falls. Taking more than five medications also increased a patient’s fall risk (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.02–2.6). Thus, the judicious prescription of medications—aimed at decreasing the number and dosage of medications an elderly patient takes—is essential to minimizing the risk for falls.

Several studies conducted in hospitalized elderly patients have repeatedly demonstrated a core group of inherent patient risk factors for falls: delirium, agitation or impaired judgment, burden of comorbidity, gait instability or lower-extremity weakness, urinary incontinence or frequency, and a history of falls.2,3,8 These risk factors are targeted as part of most inpatient fall prevention programs, as discussed below.

Several environmental hazards have been known to increase the risk of falls and injury. These include high patient-to-nurse ratio, inappropriate use of bedrails, wet floors, and lack of assistance with ambulation and toileting. The most studied of these is assistance with ambulation and toileting. Hitcho et al demonstrated that as many as 50% of falls are toileting-related.3 The study also showed that only 42% of patients who fell and used an assistive device at home had a fall in the hospital. As many as 85% of patients were not assisted with a device or person at the time of a fall.2 Unassisted falls are associated with increased injury risk (adjusted OR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.23-2.36).

Consistent with this, increased patient-to-nurse ratios are keenly associated with an increased risk of falls. Essentially, a patient whose nurse had more than five patients was 2.6 times more likely to fall than a patient whose nurse had five or fewer patients (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.1). Based on this data, hospitals have invested in low-to-the-floor beds and alarms for beds and chairs. Placing patients on a regular toileting schedule, avoiding medications that cause urinary incontinence, and attention to bowel regimens have become standard components of hospital fall prevention programs. Even though these issues have long been thought to be the purview of nurses and support staff, hospitalist involvement and awareness are crucial to ensuring that these issues are consistently addressed and enforced for every at-risk patient.

Inpatient Fall Prevention

Inpatient falls are similar to other geriatric syndromes and are multifactorial in etiology. Studies that report a decrease in the number of falls identify patients at the highest risk for falls and target multiple risk factors simultaneously.

Several inpatient fall risk assessment tools have been developed. The most widely used and validated in the acute hospital setting are the Morse Falls Scale and St. Thomas’ Risk Assessment Tool in Falling Elderly Inpatients (STRATIFY) (see Table 1, p. 24).9 Both tools incorporate the risk factors identified above—namely, the presence of cognitive or sensory deficits, environmental hazards, history of falls, lower-extremity or gait instability/weakness, and level of comorbidity to create a score. Higher scores are associated with increased fall risk. The scales have demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of 70% to 96% and 50% to 85%, respectively, depending on the population tested and the cutoff scores used.

In 2004, Healey et al published the results of one of the few successful randomized, controlled fall-prevention trials in an acute-care setting.10 Pairs of identical hospital units were randomized to intervention and control groups. The sample size was 3,386 patients, with a mean length of stay of 19 days.1 As part of the intervention group, a fall-risk assessment was performed on admission. Patients were screened for deficits in visual acuity (identify a pen, key, or watch from a distance of 2 meters), polypharmacy, orthostatic hypotension, mobility deficits, appropriate bedrail use, footwear safety, bed height, distance of patient from nursing station, loose cables, wet floors, and availability of the nurse call bell.

Interventions for patients who were identified as high fall risks included ophthalmology/optician referral for those for whom reading aides could not be procured, medication review, adjustment of bed rails, and physical therapy. Patients with a history of falls were placed close to nursing stations. Environmental hazards were removed. Patients with orthostatic hypotension were educated on slowly changing body position. Call lights were moved to within easy reach. No additional money was allocated for this study, but by performing these simple interventions, the authors were able to decrease the relative risk of falls by 29% (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.90, P=0.006). The incidence of injuries sustained as a result of falling, however, was unchanged.

Two large, prospective studies with historical controls involving 3,000 to 7,000 patients over the course of three years and incorporating similar interventions also demonstrated a decrease in the number of falls.11,12 Fonda and his colleagues were able to demonstrate a 77% reduction in the number of falls resulting in serious injuries.

Even though these studies are promising, a recent cluster-randomized, multifactorial intervention trial involving almost 4,000 patients on a dozen medical floors did not demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of falls or falls with injury.13 Several differences exist between the two randomized trials. In the latter trial, by Cumming et al, a study nurse reviewed the care plan of all of the patients on the intervention wards and made recommendations.13 Also, the study was designed so that each patient on the intervention wards received the intervention, regardless of their fall risk. Additionally, the study period was a mere three months. In the Healey trial, the nurses on the intervention units implemented targeted risk reduction for patients at high risk, and the study period was a full year.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors for falls on admission. A targeted fall risk assessment on admission would have identified him as high-risk, with a Morse score of 95 given his dementia (15 points), impaired gait status post-transmetatarsal amputation (20 points), secondary diagnoses (multiple comorbidities, 15 points) and history of falls (25 points), and presence of an IV (20 points). The STRATIFY risk assessment tool would have produced similar results.

Frequent toileting assistance, early mobilization, medication review, and environmental modification might have prevented his fall (see Table 2, pg. 24).

Bottom Line

Focused assessment of patients on admission can identify those at risk for falls. Multifactorial inpatient fall-prevention strategies have been shown to reduce the rate of falls in inpatients without increasing costs. TH

Dr. Ölveczky is a geriatric nocturnist in the hospital medicine program, division of medicine, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

References

- Fernandez HM, Callahan KE, Likourezos A, Leipzig RM. House staff member awareness of older inpatients’ risks for hazards of hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):390-396.

- Krauss MJ, Evanoff B, Hitcho E, et al. A case control study of patient, medication, and care-related risk factors for inpatient falls. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):116-122.

- Hitcho EB, Krauss MJ, Birge S, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):732-739.

- Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):42-49.

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556-561.

- Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):30-39.

- Passaro A, Volpato S, Romagnoni F, Manzoli N, Zuliani G, Fellin R. Benzodiazepines with different half-life and falling in a hospitalized population: The GIFA study. Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell'Anziano. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1222-1229.

- Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, McMurdo ME. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122-130.

- Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):130-139.

- Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D. Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):390-395.

- Fonda D, Cook J, Sandler V, Bailey M. Sustained reduction in serious fall-related injuries in older people in hospital. Med J Aust. 2006;184(8):379-382.

- Von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. Incidence of in-hospital falls in geriatric patients before and after the introduction of an interdisciplinary team-based fall-prevention intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):2068-2074.

- Cumming RG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. BMJ. 2008;336(7647):758-760.

- Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1049-1053.

Case

An 85-year-old man with peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, a history of falls, and atrial fibrillation, which was being treated with warfarin, was admitted for a left transmetatarsal amputation. On postoperative day two, the patient slipped as he was getting out of bed to use the bathroom. He hit his head on his IV pole, and a CT scan demonstrated an acute right subdural hemorrhage. He subsequently suffered eight months of delirium before passing away at a skilled nursing facility. How could this incident have been prevented?

Background

Hospitalization represents a vulnerable time for elderly people. The presence of acute illness, an unfamiliar environment, and the frequent addition of new medications predispose an elderly patient to such iatrogenic hazards of hospitalization as falls, pressure ulcers, and delirium.1 Inpatient falls are the most common type of adverse hospital event, accounting for 70% of all inpatient accidents.2 Thirty percent to 40% of inpatient falls result in injury, with 4% to 6% resulting in serious harm.2 Interestingly, 55% of falls occur in patients 60 or younger, but 60% of falls resulting in moderate to severe injury occur in those 70 and older.3

A fall is a seminal event in the life of an elderly person. Even a fall without injury can initiate a vicious circle that begins with a fear of falling and is followed by a self-restriction of mobility, which commonly results in a decline in function.4 Functional decline in the elderly has been shown to predict mortality and nursing home placement.5

Inpatient falls are thought to occur via a complex interplay between medications, inherent patient susceptibilities, and hospital environmental hazards (see Figure 1, below).

Risk Factors

Medication prescription for the hospitalized elderly patient is perhaps the area where the hospitalist can have the greatest impact in reducing a patient’s fall risk. The most common medications thought to predispose community dwelling elders to falls are psychotropic drugs: neuroleptics, sedatives, hypnotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines.6

Limited studies of hospitalized patients indicate similar drugs as culprits. Passaro et al demonstrated that benzodiazepines with a half-life <24 hours (e.g., lorazepam and oxazepam) were strongly associated with falls even after correcting for multiple confounders.7 Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression revealed that the use of other psychotropic drugs in addition to benzodiazepines (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6–3.2) was strongly associated with an increased risk of falls. Taking more than five medications also increased a patient’s fall risk (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.02–2.6). Thus, the judicious prescription of medications—aimed at decreasing the number and dosage of medications an elderly patient takes—is essential to minimizing the risk for falls.

Several studies conducted in hospitalized elderly patients have repeatedly demonstrated a core group of inherent patient risk factors for falls: delirium, agitation or impaired judgment, burden of comorbidity, gait instability or lower-extremity weakness, urinary incontinence or frequency, and a history of falls.2,3,8 These risk factors are targeted as part of most inpatient fall prevention programs, as discussed below.

Several environmental hazards have been known to increase the risk of falls and injury. These include high patient-to-nurse ratio, inappropriate use of bedrails, wet floors, and lack of assistance with ambulation and toileting. The most studied of these is assistance with ambulation and toileting. Hitcho et al demonstrated that as many as 50% of falls are toileting-related.3 The study also showed that only 42% of patients who fell and used an assistive device at home had a fall in the hospital. As many as 85% of patients were not assisted with a device or person at the time of a fall.2 Unassisted falls are associated with increased injury risk (adjusted OR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.23-2.36).

Consistent with this, increased patient-to-nurse ratios are keenly associated with an increased risk of falls. Essentially, a patient whose nurse had more than five patients was 2.6 times more likely to fall than a patient whose nurse had five or fewer patients (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.1). Based on this data, hospitals have invested in low-to-the-floor beds and alarms for beds and chairs. Placing patients on a regular toileting schedule, avoiding medications that cause urinary incontinence, and attention to bowel regimens have become standard components of hospital fall prevention programs. Even though these issues have long been thought to be the purview of nurses and support staff, hospitalist involvement and awareness are crucial to ensuring that these issues are consistently addressed and enforced for every at-risk patient.

Inpatient Fall Prevention

Inpatient falls are similar to other geriatric syndromes and are multifactorial in etiology. Studies that report a decrease in the number of falls identify patients at the highest risk for falls and target multiple risk factors simultaneously.

Several inpatient fall risk assessment tools have been developed. The most widely used and validated in the acute hospital setting are the Morse Falls Scale and St. Thomas’ Risk Assessment Tool in Falling Elderly Inpatients (STRATIFY) (see Table 1, p. 24).9 Both tools incorporate the risk factors identified above—namely, the presence of cognitive or sensory deficits, environmental hazards, history of falls, lower-extremity or gait instability/weakness, and level of comorbidity to create a score. Higher scores are associated with increased fall risk. The scales have demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of 70% to 96% and 50% to 85%, respectively, depending on the population tested and the cutoff scores used.

In 2004, Healey et al published the results of one of the few successful randomized, controlled fall-prevention trials in an acute-care setting.10 Pairs of identical hospital units were randomized to intervention and control groups. The sample size was 3,386 patients, with a mean length of stay of 19 days.1 As part of the intervention group, a fall-risk assessment was performed on admission. Patients were screened for deficits in visual acuity (identify a pen, key, or watch from a distance of 2 meters), polypharmacy, orthostatic hypotension, mobility deficits, appropriate bedrail use, footwear safety, bed height, distance of patient from nursing station, loose cables, wet floors, and availability of the nurse call bell.

Interventions for patients who were identified as high fall risks included ophthalmology/optician referral for those for whom reading aides could not be procured, medication review, adjustment of bed rails, and physical therapy. Patients with a history of falls were placed close to nursing stations. Environmental hazards were removed. Patients with orthostatic hypotension were educated on slowly changing body position. Call lights were moved to within easy reach. No additional money was allocated for this study, but by performing these simple interventions, the authors were able to decrease the relative risk of falls by 29% (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.90, P=0.006). The incidence of injuries sustained as a result of falling, however, was unchanged.

Two large, prospective studies with historical controls involving 3,000 to 7,000 patients over the course of three years and incorporating similar interventions also demonstrated a decrease in the number of falls.11,12 Fonda and his colleagues were able to demonstrate a 77% reduction in the number of falls resulting in serious injuries.

Even though these studies are promising, a recent cluster-randomized, multifactorial intervention trial involving almost 4,000 patients on a dozen medical floors did not demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of falls or falls with injury.13 Several differences exist between the two randomized trials. In the latter trial, by Cumming et al, a study nurse reviewed the care plan of all of the patients on the intervention wards and made recommendations.13 Also, the study was designed so that each patient on the intervention wards received the intervention, regardless of their fall risk. Additionally, the study period was a mere three months. In the Healey trial, the nurses on the intervention units implemented targeted risk reduction for patients at high risk, and the study period was a full year.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors for falls on admission. A targeted fall risk assessment on admission would have identified him as high-risk, with a Morse score of 95 given his dementia (15 points), impaired gait status post-transmetatarsal amputation (20 points), secondary diagnoses (multiple comorbidities, 15 points) and history of falls (25 points), and presence of an IV (20 points). The STRATIFY risk assessment tool would have produced similar results.

Frequent toileting assistance, early mobilization, medication review, and environmental modification might have prevented his fall (see Table 2, pg. 24).

Bottom Line

Focused assessment of patients on admission can identify those at risk for falls. Multifactorial inpatient fall-prevention strategies have been shown to reduce the rate of falls in inpatients without increasing costs. TH

Dr. Ölveczky is a geriatric nocturnist in the hospital medicine program, division of medicine, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

References

- Fernandez HM, Callahan KE, Likourezos A, Leipzig RM. House staff member awareness of older inpatients’ risks for hazards of hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):390-396.

- Krauss MJ, Evanoff B, Hitcho E, et al. A case control study of patient, medication, and care-related risk factors for inpatient falls. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):116-122.

- Hitcho EB, Krauss MJ, Birge S, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):732-739.

- Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):42-49.

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556-561.

- Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):30-39.

- Passaro A, Volpato S, Romagnoni F, Manzoli N, Zuliani G, Fellin R. Benzodiazepines with different half-life and falling in a hospitalized population: The GIFA study. Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell'Anziano. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1222-1229.

- Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, McMurdo ME. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):122-130.

- Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):130-139.

- Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D. Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):390-395.

- Fonda D, Cook J, Sandler V, Bailey M. Sustained reduction in serious fall-related injuries in older people in hospital. Med J Aust. 2006;184(8):379-382.

- Von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. Incidence of in-hospital falls in geriatric patients before and after the introduction of an interdisciplinary team-based fall-prevention intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):2068-2074.

- Cumming RG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. BMJ. 2008;336(7647):758-760.

- Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1049-1053.

Case

An 85-year-old man with peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, a history of falls, and atrial fibrillation, which was being treated with warfarin, was admitted for a left transmetatarsal amputation. On postoperative day two, the patient slipped as he was getting out of bed to use the bathroom. He hit his head on his IV pole, and a CT scan demonstrated an acute right subdural hemorrhage. He subsequently suffered eight months of delirium before passing away at a skilled nursing facility. How could this incident have been prevented?

Background

Hospitalization represents a vulnerable time for elderly people. The presence of acute illness, an unfamiliar environment, and the frequent addition of new medications predispose an elderly patient to such iatrogenic hazards of hospitalization as falls, pressure ulcers, and delirium.1 Inpatient falls are the most common type of adverse hospital event, accounting for 70% of all inpatient accidents.2 Thirty percent to 40% of inpatient falls result in injury, with 4% to 6% resulting in serious harm.2 Interestingly, 55% of falls occur in patients 60 or younger, but 60% of falls resulting in moderate to severe injury occur in those 70 and older.3

A fall is a seminal event in the life of an elderly person. Even a fall without injury can initiate a vicious circle that begins with a fear of falling and is followed by a self-restriction of mobility, which commonly results in a decline in function.4 Functional decline in the elderly has been shown to predict mortality and nursing home placement.5

Inpatient falls are thought to occur via a complex interplay between medications, inherent patient susceptibilities, and hospital environmental hazards (see Figure 1, below).

Risk Factors

Medication prescription for the hospitalized elderly patient is perhaps the area where the hospitalist can have the greatest impact in reducing a patient’s fall risk. The most common medications thought to predispose community dwelling elders to falls are psychotropic drugs: neuroleptics, sedatives, hypnotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines.6

Limited studies of hospitalized patients indicate similar drugs as culprits. Passaro et al demonstrated that benzodiazepines with a half-life <24 hours (e.g., lorazepam and oxazepam) were strongly associated with falls even after correcting for multiple confounders.7 Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression revealed that the use of other psychotropic drugs in addition to benzodiazepines (OR 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6–3.2) was strongly associated with an increased risk of falls. Taking more than five medications also increased a patient’s fall risk (OR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.02–2.6). Thus, the judicious prescription of medications—aimed at decreasing the number and dosage of medications an elderly patient takes—is essential to minimizing the risk for falls.

Several studies conducted in hospitalized elderly patients have repeatedly demonstrated a core group of inherent patient risk factors for falls: delirium, agitation or impaired judgment, burden of comorbidity, gait instability or lower-extremity weakness, urinary incontinence or frequency, and a history of falls.2,3,8 These risk factors are targeted as part of most inpatient fall prevention programs, as discussed below.

Several environmental hazards have been known to increase the risk of falls and injury. These include high patient-to-nurse ratio, inappropriate use of bedrails, wet floors, and lack of assistance with ambulation and toileting. The most studied of these is assistance with ambulation and toileting. Hitcho et al demonstrated that as many as 50% of falls are toileting-related.3 The study also showed that only 42% of patients who fell and used an assistive device at home had a fall in the hospital. As many as 85% of patients were not assisted with a device or person at the time of a fall.2 Unassisted falls are associated with increased injury risk (adjusted OR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.23-2.36).

Consistent with this, increased patient-to-nurse ratios are keenly associated with an increased risk of falls. Essentially, a patient whose nurse had more than five patients was 2.6 times more likely to fall than a patient whose nurse had five or fewer patients (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.1). Based on this data, hospitals have invested in low-to-the-floor beds and alarms for beds and chairs. Placing patients on a regular toileting schedule, avoiding medications that cause urinary incontinence, and attention to bowel regimens have become standard components of hospital fall prevention programs. Even though these issues have long been thought to be the purview of nurses and support staff, hospitalist involvement and awareness are crucial to ensuring that these issues are consistently addressed and enforced for every at-risk patient.

Inpatient Fall Prevention

Inpatient falls are similar to other geriatric syndromes and are multifactorial in etiology. Studies that report a decrease in the number of falls identify patients at the highest risk for falls and target multiple risk factors simultaneously.

Several inpatient fall risk assessment tools have been developed. The most widely used and validated in the acute hospital setting are the Morse Falls Scale and St. Thomas’ Risk Assessment Tool in Falling Elderly Inpatients (STRATIFY) (see Table 1, p. 24).9 Both tools incorporate the risk factors identified above—namely, the presence of cognitive or sensory deficits, environmental hazards, history of falls, lower-extremity or gait instability/weakness, and level of comorbidity to create a score. Higher scores are associated with increased fall risk. The scales have demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of 70% to 96% and 50% to 85%, respectively, depending on the population tested and the cutoff scores used.

In 2004, Healey et al published the results of one of the few successful randomized, controlled fall-prevention trials in an acute-care setting.10 Pairs of identical hospital units were randomized to intervention and control groups. The sample size was 3,386 patients, with a mean length of stay of 19 days.1 As part of the intervention group, a fall-risk assessment was performed on admission. Patients were screened for deficits in visual acuity (identify a pen, key, or watch from a distance of 2 meters), polypharmacy, orthostatic hypotension, mobility deficits, appropriate bedrail use, footwear safety, bed height, distance of patient from nursing station, loose cables, wet floors, and availability of the nurse call bell.

Interventions for patients who were identified as high fall risks included ophthalmology/optician referral for those for whom reading aides could not be procured, medication review, adjustment of bed rails, and physical therapy. Patients with a history of falls were placed close to nursing stations. Environmental hazards were removed. Patients with orthostatic hypotension were educated on slowly changing body position. Call lights were moved to within easy reach. No additional money was allocated for this study, but by performing these simple interventions, the authors were able to decrease the relative risk of falls by 29% (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.90, P=0.006). The incidence of injuries sustained as a result of falling, however, was unchanged.

Two large, prospective studies with historical controls involving 3,000 to 7,000 patients over the course of three years and incorporating similar interventions also demonstrated a decrease in the number of falls.11,12 Fonda and his colleagues were able to demonstrate a 77% reduction in the number of falls resulting in serious injuries.

Even though these studies are promising, a recent cluster-randomized, multifactorial intervention trial involving almost 4,000 patients on a dozen medical floors did not demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of falls or falls with injury.13 Several differences exist between the two randomized trials. In the latter trial, by Cumming et al, a study nurse reviewed the care plan of all of the patients on the intervention wards and made recommendations.13 Also, the study was designed so that each patient on the intervention wards received the intervention, regardless of their fall risk. Additionally, the study period was a mere three months. In the Healey trial, the nurses on the intervention units implemented targeted risk reduction for patients at high risk, and the study period was a full year.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors for falls on admission. A targeted fall risk assessment on admission would have identified him as high-risk, with a Morse score of 95 given his dementia (15 points), impaired gait status post-transmetatarsal amputation (20 points), secondary diagnoses (multiple comorbidities, 15 points) and history of falls (25 points), and presence of an IV (20 points). The STRATIFY risk assessment tool would have produced similar results.

Frequent toileting assistance, early mobilization, medication review, and environmental modification might have prevented his fall (see Table 2, pg. 24).

Bottom Line