User login

Market Watch

Discontinued Products

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension and pediatric drops for oral suspension1

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension (Amoxil brand usually for adults), 250mg/5mL (100mL and 150mL sizes)2

- Insulin isophane suspension (Humulin 50/50), due to limited use.3 Current patient demand and existing inventory note product availability through April 2010. There are about 3,000 patients in the U.S. who will be affected by this action.

- Phenytoin 30 mg (Dilantin Kapseals brand) are being reformulated in a new, extended-release formulation, but Kapseals will be discontinued.4

New Generics

- Tacrolimus (generic Prograf) capsules5

New Drugs, Indications, and Dosage Forms

- Asenapine tablets (Saphris) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat adults with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. The most common adverse effects in trials were akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence. The most common adverse effects that were reported in the bipolar disorder trials were somnolence, dizziness, movement disorders other than akathisia, and weight gain.6

- Colchicine 0.6 mg tablets (Colcrys) have been approved by the FDA to treat gout flares and familial Mediterranean fever.7 Colchicine has been used for many years but has not received FDA approval until recently. The FDA is re-evaluating some older drugs and drug classes. For example, the pancrelipase products fall under a similar ruling. Now that colchicine is approved, the manufacturer has shown that it meets modern standards for safety, effectiveness, quality, and labeling. Historically, physicians have administered colchicine hourly to treat acute gout flares until symptoms subsided or the patient developed adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. A dosing study determined that one 1.2-mg dose of this formulation followed by 0.6 mg one hour later was as effective as hourly dosing in patients without renal or hepatic dysfunction. This two-dose regimen was less toxic than prior dosing regimens and, therefore, it received the FDA’s approval.8

- Fentanyl buccal soluble film (Onsolis) has been approved by the FDA as an opioid for managing breakthrough cancer pain in patients 18 years and older who already are receiving and are tolerant to opioid therapy.9 It is available in 200-, 400-, 600-, 800- and 1,200-mcg strengths. A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) will be available with dispensing.

- Insulin aspart injection (NovoLog) has undergone a label change. NovoLog can now be used in an insulin pump for up to six days. The infusion set should be changed at least every three days. The updated label includes information about discarding the drug if temperatures exceed 37oC (98.6oF).10

- Interferon beta-1b injection (Extavia): A new brand of interferon has been approved by the FDA for treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as for patients who have experienced a first clinical episode of MS with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features consistent of the disease.11

- Morphine/naltrexone capsules (Embeda), a long-acting opioid designed to reduce drug euphoria, have been approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe chronic pain. It was developed with the abuse-deterrent drug naltrexone, which reduces euphoria when crushed or chewed.12

- Pitavastatin 4 mg (Livalo) has been approved by the FDA to treat hypercholesterolemia and combined dyslipidemia.13 It’s a potent statin with a new base structure. Additionally, it is only minimally metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway. It will be available in early 2010 in 1-, 2- and 4-mg strengths. Only time will tell whether this is truly a benefit for this new agent.

- Saxagliptin (Onglyza), a new oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus as an adjunct to diet and exercise.14 It is administered once daily at a starting dose of 2.5 mg or 5 mg, without regard to meal.15 The lower dose is recommended in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (CrCL < 50 mL/min). The lower dose (2.5 mg) also is recommended for patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, atazanavir, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, nefazodone, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, or telithromycin). The most common adverse effects in clinical trials were respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, and headache.

Pipeline

- Roflumilast (Daxas), a phosphodiesterase 4 enzyme inhibitor, has been submitted to the FDA. It is a once-daily oral treatment for patients with symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).16

- Tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin-6 receptor-inhibiting monoclonal antibody to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), has been approved for use in Europe. Its manufacturer has announced that the FDA has accepted its reapplication for treating moderate to severe RA. It is available in Japan for treating RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Castleman’s disease.17

- TZP-102, an investigational oral prokinetic agent for treating diabetic gastroparesis, has received FDA fast-track status. A multinational study is under way for this ghrelin receptor agonist.18 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City and a clinical pharmacist at New York Downtown Hospital.

Discontinued Products

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension and pediatric drops for oral suspension1

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension (Amoxil brand usually for adults), 250mg/5mL (100mL and 150mL sizes)2

- Insulin isophane suspension (Humulin 50/50), due to limited use.3 Current patient demand and existing inventory note product availability through April 2010. There are about 3,000 patients in the U.S. who will be affected by this action.

- Phenytoin 30 mg (Dilantin Kapseals brand) are being reformulated in a new, extended-release formulation, but Kapseals will be discontinued.4

New Generics

- Tacrolimus (generic Prograf) capsules5

New Drugs, Indications, and Dosage Forms

- Asenapine tablets (Saphris) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat adults with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. The most common adverse effects in trials were akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence. The most common adverse effects that were reported in the bipolar disorder trials were somnolence, dizziness, movement disorders other than akathisia, and weight gain.6

- Colchicine 0.6 mg tablets (Colcrys) have been approved by the FDA to treat gout flares and familial Mediterranean fever.7 Colchicine has been used for many years but has not received FDA approval until recently. The FDA is re-evaluating some older drugs and drug classes. For example, the pancrelipase products fall under a similar ruling. Now that colchicine is approved, the manufacturer has shown that it meets modern standards for safety, effectiveness, quality, and labeling. Historically, physicians have administered colchicine hourly to treat acute gout flares until symptoms subsided or the patient developed adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. A dosing study determined that one 1.2-mg dose of this formulation followed by 0.6 mg one hour later was as effective as hourly dosing in patients without renal or hepatic dysfunction. This two-dose regimen was less toxic than prior dosing regimens and, therefore, it received the FDA’s approval.8

- Fentanyl buccal soluble film (Onsolis) has been approved by the FDA as an opioid for managing breakthrough cancer pain in patients 18 years and older who already are receiving and are tolerant to opioid therapy.9 It is available in 200-, 400-, 600-, 800- and 1,200-mcg strengths. A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) will be available with dispensing.

- Insulin aspart injection (NovoLog) has undergone a label change. NovoLog can now be used in an insulin pump for up to six days. The infusion set should be changed at least every three days. The updated label includes information about discarding the drug if temperatures exceed 37oC (98.6oF).10

- Interferon beta-1b injection (Extavia): A new brand of interferon has been approved by the FDA for treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as for patients who have experienced a first clinical episode of MS with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features consistent of the disease.11

- Morphine/naltrexone capsules (Embeda), a long-acting opioid designed to reduce drug euphoria, have been approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe chronic pain. It was developed with the abuse-deterrent drug naltrexone, which reduces euphoria when crushed or chewed.12

- Pitavastatin 4 mg (Livalo) has been approved by the FDA to treat hypercholesterolemia and combined dyslipidemia.13 It’s a potent statin with a new base structure. Additionally, it is only minimally metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway. It will be available in early 2010 in 1-, 2- and 4-mg strengths. Only time will tell whether this is truly a benefit for this new agent.

- Saxagliptin (Onglyza), a new oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus as an adjunct to diet and exercise.14 It is administered once daily at a starting dose of 2.5 mg or 5 mg, without regard to meal.15 The lower dose is recommended in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (CrCL < 50 mL/min). The lower dose (2.5 mg) also is recommended for patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, atazanavir, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, nefazodone, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, or telithromycin). The most common adverse effects in clinical trials were respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, and headache.

Pipeline

- Roflumilast (Daxas), a phosphodiesterase 4 enzyme inhibitor, has been submitted to the FDA. It is a once-daily oral treatment for patients with symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).16

- Tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin-6 receptor-inhibiting monoclonal antibody to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), has been approved for use in Europe. Its manufacturer has announced that the FDA has accepted its reapplication for treating moderate to severe RA. It is available in Japan for treating RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Castleman’s disease.17

- TZP-102, an investigational oral prokinetic agent for treating diabetic gastroparesis, has received FDA fast-track status. A multinational study is under way for this ghrelin receptor agonist.18 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City and a clinical pharmacist at New York Downtown Hospital.

Discontinued Products

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension and pediatric drops for oral suspension1

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension (Amoxil brand usually for adults), 250mg/5mL (100mL and 150mL sizes)2

- Insulin isophane suspension (Humulin 50/50), due to limited use.3 Current patient demand and existing inventory note product availability through April 2010. There are about 3,000 patients in the U.S. who will be affected by this action.

- Phenytoin 30 mg (Dilantin Kapseals brand) are being reformulated in a new, extended-release formulation, but Kapseals will be discontinued.4

New Generics

- Tacrolimus (generic Prograf) capsules5

New Drugs, Indications, and Dosage Forms

- Asenapine tablets (Saphris) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat adults with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. The most common adverse effects in trials were akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence. The most common adverse effects that were reported in the bipolar disorder trials were somnolence, dizziness, movement disorders other than akathisia, and weight gain.6

- Colchicine 0.6 mg tablets (Colcrys) have been approved by the FDA to treat gout flares and familial Mediterranean fever.7 Colchicine has been used for many years but has not received FDA approval until recently. The FDA is re-evaluating some older drugs and drug classes. For example, the pancrelipase products fall under a similar ruling. Now that colchicine is approved, the manufacturer has shown that it meets modern standards for safety, effectiveness, quality, and labeling. Historically, physicians have administered colchicine hourly to treat acute gout flares until symptoms subsided or the patient developed adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. A dosing study determined that one 1.2-mg dose of this formulation followed by 0.6 mg one hour later was as effective as hourly dosing in patients without renal or hepatic dysfunction. This two-dose regimen was less toxic than prior dosing regimens and, therefore, it received the FDA’s approval.8

- Fentanyl buccal soluble film (Onsolis) has been approved by the FDA as an opioid for managing breakthrough cancer pain in patients 18 years and older who already are receiving and are tolerant to opioid therapy.9 It is available in 200-, 400-, 600-, 800- and 1,200-mcg strengths. A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) will be available with dispensing.

- Insulin aspart injection (NovoLog) has undergone a label change. NovoLog can now be used in an insulin pump for up to six days. The infusion set should be changed at least every three days. The updated label includes information about discarding the drug if temperatures exceed 37oC (98.6oF).10

- Interferon beta-1b injection (Extavia): A new brand of interferon has been approved by the FDA for treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as for patients who have experienced a first clinical episode of MS with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features consistent of the disease.11

- Morphine/naltrexone capsules (Embeda), a long-acting opioid designed to reduce drug euphoria, have been approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe chronic pain. It was developed with the abuse-deterrent drug naltrexone, which reduces euphoria when crushed or chewed.12

- Pitavastatin 4 mg (Livalo) has been approved by the FDA to treat hypercholesterolemia and combined dyslipidemia.13 It’s a potent statin with a new base structure. Additionally, it is only minimally metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway. It will be available in early 2010 in 1-, 2- and 4-mg strengths. Only time will tell whether this is truly a benefit for this new agent.

- Saxagliptin (Onglyza), a new oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus as an adjunct to diet and exercise.14 It is administered once daily at a starting dose of 2.5 mg or 5 mg, without regard to meal.15 The lower dose is recommended in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (CrCL < 50 mL/min). The lower dose (2.5 mg) also is recommended for patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, atazanavir, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, nefazodone, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, or telithromycin). The most common adverse effects in clinical trials were respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, and headache.

Pipeline

- Roflumilast (Daxas), a phosphodiesterase 4 enzyme inhibitor, has been submitted to the FDA. It is a once-daily oral treatment for patients with symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).16

- Tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin-6 receptor-inhibiting monoclonal antibody to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), has been approved for use in Europe. Its manufacturer has announced that the FDA has accepted its reapplication for treating moderate to severe RA. It is available in Japan for treating RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Castleman’s disease.17

- TZP-102, an investigational oral prokinetic agent for treating diabetic gastroparesis, has received FDA fast-track status. A multinational study is under way for this ghrelin receptor agonist.18 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City and a clinical pharmacist at New York Downtown Hospital.

What is the appropriate use of chronic medications in the perioperative setting?

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

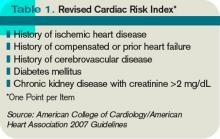

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

Perioperative Corticosteroids

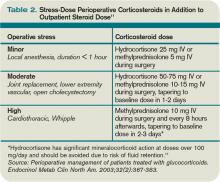

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

Perioperative Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

Perioperative Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

In the Literature

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- CPOE and quality outcomes

- Outcomes of standardized management of endocarditis

- Effect of tPA three to 4.5 hours after stroke onset

- Failure to notify patients of significant test results

- PFO repair and stroke rate

- Predictors of delay in defibrillation for in-hospital arrest

- H. pylori eradication and risk of future gastric cancer

- Bleeding risk with fondaparinux vs. enoxaparin in ACS

- Perceptions of physician ability to predict medical futility

CPOE Is Associated with Improvement in Quality Measures

Clinical question: Is computerized physician order entry (CPOE) associated with improved outcomes across a large, nationally representative sample of hospitals?

Background: Several single-institution studies suggest CPOE leads to better outcomes in quality measures for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia as defined by the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA) initiative, led by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Little systematic information is known about the effects of CPOE on quality of care.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: The Health Information Management System Society (HIMSS) analytics database of 3,364 hospitals throughout the U.S.

Synopsis: Of the hospitals that reported CPOE utilization to HIMSS, 264 (7.8%) fully implement CPOE throughout their institutions. These CPOE hospitals outperformed their peers on five of 11 quality measures related to ordering medications, and in one of nine non-medication-related measures. No difference was noted in the other measures, except CPOE hospitals were less effective at providing antibiotics within four hours of pneumonia diagnosis. Hospitals that utilized CPOE were generally academic, larger, and nonprofit. After adjusting for these differences, benefits were still preserved.

The authors indicate that the lack of systematic outperformance by CPOE hospitals in all 20 of the quality categories inherently suggests that other factors (e.g., concomitant QI efforts) are not affecting these results. Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established between CPOE and the observed benefits. CPOE might represent the commitment of certain hospitals to quality measures, but further study is needed.

Bottom line: Enhanced compliance in several CMS-established quality measures is seen in hospitals that utilize CPOE throughout their institutions.

Citation: Yu FB, Menachemi N, Berner ES, Allison JJ, Weissman NW, Houston TK. Full implementation of computerized physician order entry and medication-related quality outcomes: a study of 3,364 hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(4):278-286.

Standardized Management of Endocarditis Leads to Significant Mortality Benefit

Clinical question: Does a standardized approach to the treatment of infective endocarditis reduce mortality and morbidity?

Background: Despite epidemiological changes to the inciting bacteria and improvements in available antibiotics, mortality and morbidity associated with endocarditis remain high. The contribution of inconsistent or inaccurate treatment of endocarditis is unclear.

Study design: Case series with historical controls from 1994 to 2001, compared with protocolized patients from 2002 to 2006.

Setting: Single teaching tertiary-care hospital in France.

Synopsis: The authors established a diagnostic protocol for infectious endocarditis from 1994 to 2001 (period 1) and established a treatment protocol from 2002 to 2006 (period 2). Despite a statistically significant sicker population (older, higher comorbidities, higher coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections, and fewer healthy valves), the period-2 patients had a dramatically lower mortality rate of 8.2% (P<0.001), compared with 18.5% in period-1 patients. Fewer episodes of renal failure, organ failure, and deaths associated with embolism were noted in period 2.

Whether these results are due to more frequent care, more aggressive care (patients were “summoned” if they did not show for appointments), standardized medication and surgical options, or the effects of long-term collaboration, these results appear durable, remarkable, and reproducible.

This study is limited by its lack of randomization and extensive time frame, with concomitant changes in medical treatment and observed infectious organisms.

Bottom line: Implementation of a standardized approach to endocarditis has significant benefit on mortality and morbidity.

Citation: Botelho-Nevers E, Thuny F, Casalta JP, et al. Dramatic reduction in infective endocarditis-related mortality with a management-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14):1290-1298.

Treatment with tPA in the Three- to 4.5-Hour Time Window after Stroke Is Beneficial

Clinical question: What is the effect of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) on outcomes in patients treated in the three- to 4.5-hour window after stroke?

Background: The third European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study 3 (ECASS-3) demonstrated benefit of treatment of acute stroke with tPA in the three- to 4.5-hour time window. Prior studies, however, did not show superiority of tPA over placebo, and there is a lack of a confirmatory randomized, controlled trial of tPA in this time frame.

Study design: Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

Setting: Four studies involving 1,622 patients who were treated with intravenous tPA for acute ischemic stroke from three to 4.5 hours after stroke compared with placebo.

Synopsis: Of the randomized, controlled trials of intravenous tPA for treatment of acute ischemic stroke from three to 4.5 hours after stroke, four trials (ECASS-1, ECASS-2, ECASS-3, and ATLANTIS) were included in the analysis. Treatment with tPA in the three- to 4.5-hour time window is associated with increased favorable outcomes based on the global outcome measure (OR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.10-1.56, P=0.002) and the modified Rankin Scale (OR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.07-1.59, P=0.01), compared with placebo. The 90-day mortality rate was not significantly different between the treatment and placebo groups (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.75-1.43, P=0.83).

Due to the relatively high dose of tPA (1.1 mg/kg) administered in the ECASS-1 trial, a separate meta-analysis looking at the other three trials (tPA dose of 0.9 mg/kg) was conducted, and the favorable outcome with tPA remained.

Bottom line: Treatment of acute ischemic stroke with tPA in the three- to 4.5-hour time window results in an increased rate of favorable functional outcomes without a significant difference in mortality.