User login

The case for robotic-assisted hysterectomy

During my address as president of the Board of Trustees of the AAGL in 2008, I noted that essentially 95% of all cholecystectomies, 95% of all bariatric surgery, and 70% of all appendectomies in the United States were performed laparoscopically. Unfortunately, less than 20% of hysterectomies were performed via a minimally invasive route.

Subsequently, at the time of my 2012 presidential address for the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), I noted that the percentage of minimally invasive hysterectomies performed in the United States now reached 50%, while the percentage of laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies was still mired at 18% and 14%, respectively. The increase in a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy appeared to be due to the newest method of hysterectomy; that is, robotic-assisted hysterectomy.

On March 14, 2013, Dr. James T. Breeden, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, released a statement regarding robotic surgery. In that, he noted, "While there may be some advantages to the use of robotics in complex hysterectomies ... studies have shown that adding this expensive technology for routine surgical care does not improve patient outcomes. Consequently, there is no good data proving that robotic hysterectomy is even as good as – let alone better than – existing, and far less costly, minimally invasive alternatives."

Dr. Breeden then went on to refer to a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA 2013;309:689-98) to make the point that, in a study of 264,758 patients undergoing hysterectomy in 441 hospitals in the Premier hospital group, robotics added an average of $2,000/procedure without any demonstrable benefit.

Interestingly, however, the authors of the JAMA article acknowledge that while uptake of laparoscopic hysterectomy has been slow since its inception in the early 1990s, accounting for only 14% of hysterectomies in 2005, within 3 years of the introduction of the adoption of robotics for hysterectomy, nearly 10% of all cases were completed by this enabling technology. Furthermore, the authors comment that, "The introduction of robotic gynecologic surgery was associated with a decrease in the rate of abdominal hysterectomy and an increase in the use of minimally invasive surgery as a whole, including both laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomy." The authors acknowledge that robotic surgery may be easier to learn and that robotic assistance may allow for the completion of more technically demanding cases. In addition, they note that the increase in numbers of laparoscopic hysterectomy may have occurred because of competitive pressures or an increased awareness and appreciation of minimally invasive surgical options.

In comparison, the authors found that in hospitals at which robotic surgery was not performed as of the first quarter of 2010, nearly 50% of all hysterectomies were performed via an open abdominal route, while less than 40% of hysterectomies were performed with a laparotomy incision when robotic hysterectomy was performed at the hospital. With the future adoption of the robotics in gynecologic surgery, I am sure there will be a continued reduction in open abdominal hysterectomy. Benefit ... a resounding yes!

Another fascinating finding of the JAMA study was the fact that overall complication rates were similar for robotic-assisted and laparoscopic hysterectomy (5.5% vs. 5.3%; relative risk, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.86-1.24). Moreover, patients who underwent a robotic-assisted hysterectomy were less likely to have a length of stay longer than 2 days (19.6% vs. 24.9%; RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67-0.92).

Despite no differences in complications in the JAMA study, given the fact that robotics is an emerging technology, one can easily extrapolate that the percentage of cases performed in the study by relatively inexperienced robotic surgeons, as compared with laparoscopic surgeons, was higher. Therefore, with increased surgeon experience, as with any new technology, the rate of complications would be expected to be further decreased. To this end, one must remember that early in its inception, the New York Assembly voiced concerns with laparoscopic cholecystectomy secondary to complications. Now, virtually 95% of all cholecystectomies in the United States are performed via a laparoscopic route. Currently, what is the latest focus in cholecystectomy ... robotic assisted single site cholecystectomy that is being rapidly adopted throughout the country.

While one must acknowledge that, at present, robotic-assisted surgery would appear to be more expensive to perform than laparoscopic surgery is, it is difficult to ascertain what that cost differential is truly. Furthermore, one would anticipate with increased experience and efficiency that cost would, indeed, decrease. While in 1996, Dr. James H. Dorsey published an article on the higher costs associated with laparoscopic surgery (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:476-82), more recent studies by Warren L., et al. (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:581-8), and Jonsdottir G.M., et al. (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:1142-9) actually show that the laparoscopic route can be more cost effective.

In this era of cost containment, it is imperative that surgical innovation thrive. Where would all specialties involved in minimally invasive surgery be if surgical pioneer and visionary Professor Kurt Semm were not allowed to perform early operative laparoscopic cases in Kiel, Germany? As chronicled by his associate, Professor Lisolette Mettler, in the July-September 2003 NewsScope of the AAGL, "Kurt endured much resistance, including a request for him to undergo a brain scan to rule out brain damage when attempting to introduce operative laparoscopy; the laughter of general surgeons when he recommended laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the late 1970s; a call for suspension by the president of the German Surgical Society after a 1981 lecture on laparoscopic appendectomy; and rejection of a paper on laparoscopic appendectomy to the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology as unethical." Where would the cholecystectomy market be if general surgeons headed the randomized controlled trial of open vs. laparoscopic cholecystectomy published in Lancet in 1996 (Lancet 1996;347:989-94)? The study concluded that the open procedure was superior because there was no difference in hospital stay or recovery, compared with the laparoscopic route. Where would minimally invasive gynecologic surgery be if our specialty fell in line behind Dr. Roy Pitkin, then president of ACOG, who in 1992 entitled an editorial in Obstetrics & Gynecology "Operative Laparoscopy: Surgical Advance or Technical Gimmick?" (Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;79:441-2). In this editorial he questioned operative laparoscopy on the following:

• How does one separate technical feasibility from therapeutic appropriateness?

• What is the nature of "quality assurance"?

• How can appropriate credentialing criteria be established for procedures not taught in residency and for which no present member of the medical staff can claim experience?

• To what extent are these procedures "experimental," requiring review by an institutional body charged with protection of human subjects, and how should truly informed consent be obtained?

• What about fees? When the procedure is not part of established clinical care, is it ethical to charge for professional services?

Dr. Pitkin concluded by commenting, "Our approach to evaluation of these newer surgical techniques is not something of which we can be proud." Many of these same concerns are currently being voiced by those who do not see the brilliant potential of robotics in gynecologic surgery.

Eighteen years later, in a subsequent editorial (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:890-1), Dr. Pitkin acknowledged that "A substantial body of evidence has accumulated in the recent years to support the laparoscopic approach to various gynecologic operations. ... From this extensive literature, it is now clear that many, if not most gynecologic operations traditionally done by laparotomy are amenable to a laparoscopic approach. Further, the studies are consistent in indicating that operative laparoscopy confers unequivocal advantages over older surgical approaches."

Dr. Pitkin and his coauthor, Dr. William Parker, then go on to discuss the issue of cost, "All health care financial studies are complicated by inconsistencies and uncertainties regarding the meaning of cost. ... Increase in operating time with laparoscopic surgery and disposable instruments are offset, by decreased charges reflecting shortened postoperative hospital stays. If a societal cost that included financial results from early return to work or full home activity were calculated, the advantage of endoscopic surgery would be even greater."

Just as it is imperative that our surgical specialty must remain innovative, we must remember, as can be learned with Dr. Pitkin’s two editorials, that scientific evidence behind the innovation takes time. The fact that, in its infancy, robotic assisted surgery has enabled more gynecologic surgeons to perform minimally invasive surgery for more patients cannot be denied. As seen by the JAMA article, even early on, it can be performed safely and effectively. Data collected in the final decade of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st have enabled operative laparoscopy to enter mainstream surgical care. One can foresee, with the accumulation of knowledge and experience, that robotics will have a similar – if not even greater – role within our specialty. We must learn from William Shakespeare, who provided Marc Anthony the words, "I have come to bury Caesar, not to praise him." We must not come here to bury robotic assisted surgery, but to praise it!

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller has received grants from Intuitive Surgical Inc. He also has served as a consultant for and served on the speakers bureau for Intuitive.

During my address as president of the Board of Trustees of the AAGL in 2008, I noted that essentially 95% of all cholecystectomies, 95% of all bariatric surgery, and 70% of all appendectomies in the United States were performed laparoscopically. Unfortunately, less than 20% of hysterectomies were performed via a minimally invasive route.

Subsequently, at the time of my 2012 presidential address for the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), I noted that the percentage of minimally invasive hysterectomies performed in the United States now reached 50%, while the percentage of laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies was still mired at 18% and 14%, respectively. The increase in a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy appeared to be due to the newest method of hysterectomy; that is, robotic-assisted hysterectomy.

On March 14, 2013, Dr. James T. Breeden, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, released a statement regarding robotic surgery. In that, he noted, "While there may be some advantages to the use of robotics in complex hysterectomies ... studies have shown that adding this expensive technology for routine surgical care does not improve patient outcomes. Consequently, there is no good data proving that robotic hysterectomy is even as good as – let alone better than – existing, and far less costly, minimally invasive alternatives."

Dr. Breeden then went on to refer to a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA 2013;309:689-98) to make the point that, in a study of 264,758 patients undergoing hysterectomy in 441 hospitals in the Premier hospital group, robotics added an average of $2,000/procedure without any demonstrable benefit.

Interestingly, however, the authors of the JAMA article acknowledge that while uptake of laparoscopic hysterectomy has been slow since its inception in the early 1990s, accounting for only 14% of hysterectomies in 2005, within 3 years of the introduction of the adoption of robotics for hysterectomy, nearly 10% of all cases were completed by this enabling technology. Furthermore, the authors comment that, "The introduction of robotic gynecologic surgery was associated with a decrease in the rate of abdominal hysterectomy and an increase in the use of minimally invasive surgery as a whole, including both laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomy." The authors acknowledge that robotic surgery may be easier to learn and that robotic assistance may allow for the completion of more technically demanding cases. In addition, they note that the increase in numbers of laparoscopic hysterectomy may have occurred because of competitive pressures or an increased awareness and appreciation of minimally invasive surgical options.

In comparison, the authors found that in hospitals at which robotic surgery was not performed as of the first quarter of 2010, nearly 50% of all hysterectomies were performed via an open abdominal route, while less than 40% of hysterectomies were performed with a laparotomy incision when robotic hysterectomy was performed at the hospital. With the future adoption of the robotics in gynecologic surgery, I am sure there will be a continued reduction in open abdominal hysterectomy. Benefit ... a resounding yes!

Another fascinating finding of the JAMA study was the fact that overall complication rates were similar for robotic-assisted and laparoscopic hysterectomy (5.5% vs. 5.3%; relative risk, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.86-1.24). Moreover, patients who underwent a robotic-assisted hysterectomy were less likely to have a length of stay longer than 2 days (19.6% vs. 24.9%; RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67-0.92).

Despite no differences in complications in the JAMA study, given the fact that robotics is an emerging technology, one can easily extrapolate that the percentage of cases performed in the study by relatively inexperienced robotic surgeons, as compared with laparoscopic surgeons, was higher. Therefore, with increased surgeon experience, as with any new technology, the rate of complications would be expected to be further decreased. To this end, one must remember that early in its inception, the New York Assembly voiced concerns with laparoscopic cholecystectomy secondary to complications. Now, virtually 95% of all cholecystectomies in the United States are performed via a laparoscopic route. Currently, what is the latest focus in cholecystectomy ... robotic assisted single site cholecystectomy that is being rapidly adopted throughout the country.

While one must acknowledge that, at present, robotic-assisted surgery would appear to be more expensive to perform than laparoscopic surgery is, it is difficult to ascertain what that cost differential is truly. Furthermore, one would anticipate with increased experience and efficiency that cost would, indeed, decrease. While in 1996, Dr. James H. Dorsey published an article on the higher costs associated with laparoscopic surgery (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:476-82), more recent studies by Warren L., et al. (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:581-8), and Jonsdottir G.M., et al. (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:1142-9) actually show that the laparoscopic route can be more cost effective.

In this era of cost containment, it is imperative that surgical innovation thrive. Where would all specialties involved in minimally invasive surgery be if surgical pioneer and visionary Professor Kurt Semm were not allowed to perform early operative laparoscopic cases in Kiel, Germany? As chronicled by his associate, Professor Lisolette Mettler, in the July-September 2003 NewsScope of the AAGL, "Kurt endured much resistance, including a request for him to undergo a brain scan to rule out brain damage when attempting to introduce operative laparoscopy; the laughter of general surgeons when he recommended laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the late 1970s; a call for suspension by the president of the German Surgical Society after a 1981 lecture on laparoscopic appendectomy; and rejection of a paper on laparoscopic appendectomy to the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology as unethical." Where would the cholecystectomy market be if general surgeons headed the randomized controlled trial of open vs. laparoscopic cholecystectomy published in Lancet in 1996 (Lancet 1996;347:989-94)? The study concluded that the open procedure was superior because there was no difference in hospital stay or recovery, compared with the laparoscopic route. Where would minimally invasive gynecologic surgery be if our specialty fell in line behind Dr. Roy Pitkin, then president of ACOG, who in 1992 entitled an editorial in Obstetrics & Gynecology "Operative Laparoscopy: Surgical Advance or Technical Gimmick?" (Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;79:441-2). In this editorial he questioned operative laparoscopy on the following:

• How does one separate technical feasibility from therapeutic appropriateness?

• What is the nature of "quality assurance"?

• How can appropriate credentialing criteria be established for procedures not taught in residency and for which no present member of the medical staff can claim experience?

• To what extent are these procedures "experimental," requiring review by an institutional body charged with protection of human subjects, and how should truly informed consent be obtained?

• What about fees? When the procedure is not part of established clinical care, is it ethical to charge for professional services?

Dr. Pitkin concluded by commenting, "Our approach to evaluation of these newer surgical techniques is not something of which we can be proud." Many of these same concerns are currently being voiced by those who do not see the brilliant potential of robotics in gynecologic surgery.

Eighteen years later, in a subsequent editorial (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:890-1), Dr. Pitkin acknowledged that "A substantial body of evidence has accumulated in the recent years to support the laparoscopic approach to various gynecologic operations. ... From this extensive literature, it is now clear that many, if not most gynecologic operations traditionally done by laparotomy are amenable to a laparoscopic approach. Further, the studies are consistent in indicating that operative laparoscopy confers unequivocal advantages over older surgical approaches."

Dr. Pitkin and his coauthor, Dr. William Parker, then go on to discuss the issue of cost, "All health care financial studies are complicated by inconsistencies and uncertainties regarding the meaning of cost. ... Increase in operating time with laparoscopic surgery and disposable instruments are offset, by decreased charges reflecting shortened postoperative hospital stays. If a societal cost that included financial results from early return to work or full home activity were calculated, the advantage of endoscopic surgery would be even greater."

Just as it is imperative that our surgical specialty must remain innovative, we must remember, as can be learned with Dr. Pitkin’s two editorials, that scientific evidence behind the innovation takes time. The fact that, in its infancy, robotic assisted surgery has enabled more gynecologic surgeons to perform minimally invasive surgery for more patients cannot be denied. As seen by the JAMA article, even early on, it can be performed safely and effectively. Data collected in the final decade of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st have enabled operative laparoscopy to enter mainstream surgical care. One can foresee, with the accumulation of knowledge and experience, that robotics will have a similar – if not even greater – role within our specialty. We must learn from William Shakespeare, who provided Marc Anthony the words, "I have come to bury Caesar, not to praise him." We must not come here to bury robotic assisted surgery, but to praise it!

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller has received grants from Intuitive Surgical Inc. He also has served as a consultant for and served on the speakers bureau for Intuitive.

During my address as president of the Board of Trustees of the AAGL in 2008, I noted that essentially 95% of all cholecystectomies, 95% of all bariatric surgery, and 70% of all appendectomies in the United States were performed laparoscopically. Unfortunately, less than 20% of hysterectomies were performed via a minimally invasive route.

Subsequently, at the time of my 2012 presidential address for the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), I noted that the percentage of minimally invasive hysterectomies performed in the United States now reached 50%, while the percentage of laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies was still mired at 18% and 14%, respectively. The increase in a minimally invasive approach to hysterectomy appeared to be due to the newest method of hysterectomy; that is, robotic-assisted hysterectomy.

On March 14, 2013, Dr. James T. Breeden, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, released a statement regarding robotic surgery. In that, he noted, "While there may be some advantages to the use of robotics in complex hysterectomies ... studies have shown that adding this expensive technology for routine surgical care does not improve patient outcomes. Consequently, there is no good data proving that robotic hysterectomy is even as good as – let alone better than – existing, and far less costly, minimally invasive alternatives."

Dr. Breeden then went on to refer to a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA 2013;309:689-98) to make the point that, in a study of 264,758 patients undergoing hysterectomy in 441 hospitals in the Premier hospital group, robotics added an average of $2,000/procedure without any demonstrable benefit.

Interestingly, however, the authors of the JAMA article acknowledge that while uptake of laparoscopic hysterectomy has been slow since its inception in the early 1990s, accounting for only 14% of hysterectomies in 2005, within 3 years of the introduction of the adoption of robotics for hysterectomy, nearly 10% of all cases were completed by this enabling technology. Furthermore, the authors comment that, "The introduction of robotic gynecologic surgery was associated with a decrease in the rate of abdominal hysterectomy and an increase in the use of minimally invasive surgery as a whole, including both laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomy." The authors acknowledge that robotic surgery may be easier to learn and that robotic assistance may allow for the completion of more technically demanding cases. In addition, they note that the increase in numbers of laparoscopic hysterectomy may have occurred because of competitive pressures or an increased awareness and appreciation of minimally invasive surgical options.

In comparison, the authors found that in hospitals at which robotic surgery was not performed as of the first quarter of 2010, nearly 50% of all hysterectomies were performed via an open abdominal route, while less than 40% of hysterectomies were performed with a laparotomy incision when robotic hysterectomy was performed at the hospital. With the future adoption of the robotics in gynecologic surgery, I am sure there will be a continued reduction in open abdominal hysterectomy. Benefit ... a resounding yes!

Another fascinating finding of the JAMA study was the fact that overall complication rates were similar for robotic-assisted and laparoscopic hysterectomy (5.5% vs. 5.3%; relative risk, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.86-1.24). Moreover, patients who underwent a robotic-assisted hysterectomy were less likely to have a length of stay longer than 2 days (19.6% vs. 24.9%; RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67-0.92).

Despite no differences in complications in the JAMA study, given the fact that robotics is an emerging technology, one can easily extrapolate that the percentage of cases performed in the study by relatively inexperienced robotic surgeons, as compared with laparoscopic surgeons, was higher. Therefore, with increased surgeon experience, as with any new technology, the rate of complications would be expected to be further decreased. To this end, one must remember that early in its inception, the New York Assembly voiced concerns with laparoscopic cholecystectomy secondary to complications. Now, virtually 95% of all cholecystectomies in the United States are performed via a laparoscopic route. Currently, what is the latest focus in cholecystectomy ... robotic assisted single site cholecystectomy that is being rapidly adopted throughout the country.

While one must acknowledge that, at present, robotic-assisted surgery would appear to be more expensive to perform than laparoscopic surgery is, it is difficult to ascertain what that cost differential is truly. Furthermore, one would anticipate with increased experience and efficiency that cost would, indeed, decrease. While in 1996, Dr. James H. Dorsey published an article on the higher costs associated with laparoscopic surgery (N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:476-82), more recent studies by Warren L., et al. (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:581-8), and Jonsdottir G.M., et al. (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;117:1142-9) actually show that the laparoscopic route can be more cost effective.

In this era of cost containment, it is imperative that surgical innovation thrive. Where would all specialties involved in minimally invasive surgery be if surgical pioneer and visionary Professor Kurt Semm were not allowed to perform early operative laparoscopic cases in Kiel, Germany? As chronicled by his associate, Professor Lisolette Mettler, in the July-September 2003 NewsScope of the AAGL, "Kurt endured much resistance, including a request for him to undergo a brain scan to rule out brain damage when attempting to introduce operative laparoscopy; the laughter of general surgeons when he recommended laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the late 1970s; a call for suspension by the president of the German Surgical Society after a 1981 lecture on laparoscopic appendectomy; and rejection of a paper on laparoscopic appendectomy to the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology as unethical." Where would the cholecystectomy market be if general surgeons headed the randomized controlled trial of open vs. laparoscopic cholecystectomy published in Lancet in 1996 (Lancet 1996;347:989-94)? The study concluded that the open procedure was superior because there was no difference in hospital stay or recovery, compared with the laparoscopic route. Where would minimally invasive gynecologic surgery be if our specialty fell in line behind Dr. Roy Pitkin, then president of ACOG, who in 1992 entitled an editorial in Obstetrics & Gynecology "Operative Laparoscopy: Surgical Advance or Technical Gimmick?" (Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;79:441-2). In this editorial he questioned operative laparoscopy on the following:

• How does one separate technical feasibility from therapeutic appropriateness?

• What is the nature of "quality assurance"?

• How can appropriate credentialing criteria be established for procedures not taught in residency and for which no present member of the medical staff can claim experience?

• To what extent are these procedures "experimental," requiring review by an institutional body charged with protection of human subjects, and how should truly informed consent be obtained?

• What about fees? When the procedure is not part of established clinical care, is it ethical to charge for professional services?

Dr. Pitkin concluded by commenting, "Our approach to evaluation of these newer surgical techniques is not something of which we can be proud." Many of these same concerns are currently being voiced by those who do not see the brilliant potential of robotics in gynecologic surgery.

Eighteen years later, in a subsequent editorial (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:890-1), Dr. Pitkin acknowledged that "A substantial body of evidence has accumulated in the recent years to support the laparoscopic approach to various gynecologic operations. ... From this extensive literature, it is now clear that many, if not most gynecologic operations traditionally done by laparotomy are amenable to a laparoscopic approach. Further, the studies are consistent in indicating that operative laparoscopy confers unequivocal advantages over older surgical approaches."

Dr. Pitkin and his coauthor, Dr. William Parker, then go on to discuss the issue of cost, "All health care financial studies are complicated by inconsistencies and uncertainties regarding the meaning of cost. ... Increase in operating time with laparoscopic surgery and disposable instruments are offset, by decreased charges reflecting shortened postoperative hospital stays. If a societal cost that included financial results from early return to work or full home activity were calculated, the advantage of endoscopic surgery would be even greater."

Just as it is imperative that our surgical specialty must remain innovative, we must remember, as can be learned with Dr. Pitkin’s two editorials, that scientific evidence behind the innovation takes time. The fact that, in its infancy, robotic assisted surgery has enabled more gynecologic surgeons to perform minimally invasive surgery for more patients cannot be denied. As seen by the JAMA article, even early on, it can be performed safely and effectively. Data collected in the final decade of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st have enabled operative laparoscopy to enter mainstream surgical care. One can foresee, with the accumulation of knowledge and experience, that robotics will have a similar – if not even greater – role within our specialty. We must learn from William Shakespeare, who provided Marc Anthony the words, "I have come to bury Caesar, not to praise him." We must not come here to bury robotic assisted surgery, but to praise it!

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller has received grants from Intuitive Surgical Inc. He also has served as a consultant for and served on the speakers bureau for Intuitive.

Advancements in robotic hysterectomy

Robotic-assisted surgery has been both celebrated as "revolutionary" and defamed as a "crutch." No matter where your loyalties lie in this debate, what is not debatable is the dramatic increase in minimally invasive surgery (MIS) rates for hysterectomy since robotic-assisted surgery was approved for gynecology in 2005. Rates vary across samples and sources, but according to 2011 data from Solucient and 2010 data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, approximately 27% of hysterectomies are performed with the robot, 26% with standard laparoscopy, and 12% vaginally.

It should be clear to all in 2013 that a total abdominal hysterectomy approach (TAH) is the least favored route for hysterectomy in terms of global cost, invasiveness, and overall complication rate. Therefore, as the AAGL has stated, we should all strive to improve our MIS skill-set – whether it is by the vaginal, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approach (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Personally, I prefer robotic-assisted techniques. As a community gynecologist, I believe that the marriage of high-tech computerization with the surgical sciences allows for more reproducibility than the traditional vaginal or laparoscopic approaches (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:286-91; Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:535-42).

In my experience, there are now three reproducible techniques for performing robotic-assisted hysterectomy. The first is a robotic total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) technique involving 4-5 ports, which incorporates some of the steps familiar to surgeons performing TAH. This approach was initially described by Dr. Charles Koh after the advent of the Koh colpotomizer (J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 1998;5:187-92) and was then modified and adapted to the robotic platform with my colleagues at the Ochsner Clinic in Louisiana.

The second is a reduced two-port technique that was developed last year with my colleagues at the Texas Institute for Robotic Surgery in Austin.

Last, clearance by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2013 for a da Vinci single-site instrumentation package for use in benign hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy makes the single-site technique a third reproducible approach for performing hysterectomy with the robotic platform. Use of the instrumentation package is currently being launched at Celebration Health Florida Hospital, the Cleveland Clinic, Newark (N.J.) Beth Israel Medical Center, and the Texas Institute for Robotic Surgery.

In addition to being more reproducible, the robotic route to hysterectomy now affords a "see-and-treat" approach, by which we can insert an endoscopic camera, assess the difficulty of the operation (pathology, uterine size, adhesions, etc.), and then select the robotic technique that is best for the patient.

Multisite technique

In positioning the patient, precautions are taken to prevent patient slippage on the operating table during steep Trendelenburg. Most commonly, we place a gel pad or egg crate mattress directly onto the operating table, secure it with tape, and follow with direct placement of the patient onto the gel pad or egg crate. The patient’s arms are then padded and tucked by the sides and the legs are placed in Allen stirrups.

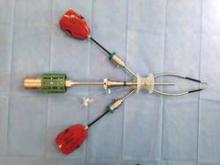

The actual procedure is begun by placing the uterine manipulator of choice. I prefer the RUMI II System with articulating tip or the Advincula Arch with the Koh colpotomizer ring (CooperSurgical, Trumball, Conn.). Other popular options are the VCare manipulator with cup (ConMed Endosurgery, Utica, N.Y.) and the McCarus-Volker Fornisee (LSI Solutions, Victor, N.Y.).

The vaginal pneumo-occlusion balloon can be placed on all three manipulators and is critical for maintaining the pneumoperitoneum that allows for the success of this technique. The importance of properly placing the uterine manipulator of your choice cannot be overemphasized.

For insufflation, I use a Veress needle placed intraumbilically or in the left upper quadrant (LUQ), depending on the patient’s surgical history. The LUQ is preferred if the patient has a history of a prior midline incision. (The stomach must be desufflated first.) The intraumbilical approach is preferred if the patient has a history of LUQ or bariatric surgery.

For port placement, the 8-mm camera port can be placed 8-10 cm above the fundus of the uterus when pushed cephalad on examination under anesthesia (EUA). The robotic camera or a separate camera with a 5-mm laparoscope is introduced (hand-held), and a four-quadrant inspection is undertaken. Direct visualization is used to place two or three additional 8-mm ports in an arch configuration. An 8-mm assistant port is placed on the patient’s side opposite the surgeon’s dominant hand. All ports are spaced 8-10 cm away from each other.

The patient is placed in sufficiently steep Trendelenburg to allow the small bowel to be displaced from the pelvis. The surgical cart is straight docked between the patient’s legs or side docked on the surgeon’s dominant hand side. The 8-mm camera is placed into the camera arm, and then two or three (per the surgeon’s preference) 8-mm robotic instruments are placed under direct visualization.

I prefer to use three instruments during the procedure: the fenestrated bipolar grasper, the monopolar scissors, and the mega suture-cut needle driver.

The ureters are identified. Retroperitoneal dissection is utilized to confirm the ureteral path if needed. Depending on the patient’s desires and history, salpingectomy may be performed.

Isolation and transection of the infundibulopelvic ligaments or the utero-ovarian ligaments are then undertaken. The dissection is carried to the middle of the round ligament, well away from the uterus (where you would place suture when performing TAH). The round ligament is transected, allowing the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament to separate and be visualized. These initial steps will secure two of the four main blood supplies, avoid early uterine artery bleeding, and maximize uterine mobility with larger uteri.

To outline the bladder flap, the location of the Koh ring, VCare cup, or McCarus-Volker Fornisee at the cervicovaginal junction should be noted and used as a general target. The bladder is then filled through the Foley to confirm its location and is then emptied. The anterior leaf of the broad ligament is then picked up and tented with the fenestrated bipolar grasper.

The monopolar scissors are employed to incise the anterior leaf from where the round ligament was transected to the area just cephalad of the cervicovaginal ring and the border of the bladder, in a fashion similar to TAH. Each of these steps is performed bilaterally.

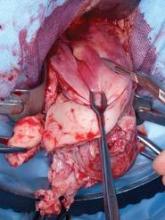

Next, in preparation for the anterior colpotomy, further development of the bladder flap is necessary. Aggressive and continuous cephalad pressure of the uterine manipulator with the ring/cup is critical to create a clear delineation of the cervicovaginal junction. Creation of the bladder flap is then completed in the caudad direction approximately 1-2 cm over the ring/cup (see image 2).

The anterior colpotomy is initiated with the posterior displacement of the uterine fundus using the RUMI II articulating tip (CooperSurgical) by rotating the handle counterclockwise. This movement simultaneously allows for pressure and emphasis to be placed on the anterior portion of the Koh ring.

Using a clockface as the reference, the anterior colpotomy is initiated at the 12 o’clock position with the monopolar scissors (settings: 30 watts). Once the ring/cup is successfully identified, the colpotomy is extended from the 12 o’clock position to the 2 o’clock and 10 o’clock positions, stopping to avoid the uterine arteries bilaterally.

To begin the posterior colpotomy, the uterine fundus is repositioned anteriorly while maintaining aggressive, continuous cephalad pressure. Again, the RUMI II allows for anterior displacement of the uterine fundus with posterior pressure and emphasis on the Koh ring by turning its handle – this time in the clockwise direction. The posterior colpotomy is initiated at the 6 o’clock position and extended upward to the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions, stopping to avoid the uterine arteries bilaterally.

For taking down the uterine arteries, the optimal placement of the uterus is a midplane position. A clear view of the uterine sidewall is created with retraction using a grasper on the remnant of the round ligament. While maintaining this view, the uterine artery is grasped, cauterized, and transected high up on the uterine sidewall.

The initial pedicle is created well away from the ring/cup in a fashion similar to the placement of a curved Heaney clamp when performing a TAH (see image 3).

Subsequently, each pedicle is then cauterized and transected close to the uterine sidewall, allowing it to fall away from the uterus as progress toward the vaginal ring/cup is made. This portion of the procedure is similar to creating pedicles with straight Heaney clamps during a TAH. Aggressive cephalad pressure is placed on the uterine manipulator and cup throughout the process, further allowing the ureters to fall away with the formation of each pedicle. Upon reaching the vaginal ring/cup, the circumferential colpotomy is completed at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions.

The specimen is then removed intact transvaginally or is morcellated. Large uteri may be morcellated endoscopically or may be removed by traditional vaginal morcellation techniques to avoid additional costs.

To decrease the chances of vaginal cuff dehiscence, it is critical to use low monopolar energy settings, create appropriate tension to allow efficient and quick colpotomies, and create an adequate bladder flap to allow incorporation of 1-2 cm of vaginal cuff tissue in the closure.

Common techniques for cuff closure include tying the suture with figure-of-eight stitches, running the suture with Lapra-Ty anchors (Ethicon Endosurgery, Nokesville, Va.), or completing the closure with barbed suture.

Dual-site technique

Patient positioning, placement of the uterine manipulator, and insufflation are all performed as previously described. However, with the two-port technique we strongly recommend using the RUMI II, which provides an added degree of manipulation as a result of its articulating tip.

The 8-mm camera port is placed midline 8-10 cm above the uterine fundus when pushed cephalad during EUA. Following the arched port arrangement described above, one additional 8-mm port is placed on the surgeon’s dominant hand side 8-10 cm lateral to the camera port in the mediolateral position. A 2-mm portless alligator grasper is placed 8-10 cm from the camera port on the opposite side (the surgeon’s nondominant side) in the mediolateral position after the robotic surgical system is docked.

The surgical cart is side docked on the surgeon’s dominant hand side, which is the same side as the working port for the robotic instrument. The 8-mm camera is then placed into the camera port and the endowrist one vessel sealer is placed under direct visualization into the robotic working port. Next, the 2-mm alligator grasper is punched through the dermis in needlelike fashion under direct visualization in the location as just described.

(For the system to correctly count instrument lives in the active robotic instrument arm, a "dummy" trocar [locked into the robotic arm but not inserted into the patient’s abdomen] must be placed into an inactive robotic arm opposite the vessel sealer.)

We use the camera arm and one robotic arm for this technique and employ three robotic instruments and a portless 2-mm grasper. Currently, we have successfully performed the two-port technique on uteri up to 16 weeks without the use of additional arms or open conversion.

The order of steps to complete the dual-site hysterectomy generally resembles that of the multisite approach, with several nuances.

The technique for lateral attachments is generally the same, except that the surgeon employs an articulating endowrist one vessel sealer for sealing and cutting tissue, while the first assist uses the 2-mm alligator grasper to proactively present and retract the adnexa for the surgeon (see image 4).

Once the round ligaments are transected, the vessel sealer is replaced with the monopolar scissors. The first assist uses the 2-mm grasper to tent the anterior leaf of the broad ligament, and the surgeon utilizes the scissors to outline and develop the bladder flap as described above. An advanced uterine manipulation skill-set is highly recommended.

After the development of the bladder flap is completed, the anterior and posterior colpotomies are completed as described above (see image 5).

Following completion of the colpotomies, the monopolar scissors are removed and the endowrist one vessel sealer is reinserted. The first assist grasps the round ligament remnant and retracts it to provide a clear view of the uterine sidewall and vessels while cephalad pressure is maintained on the manipulator. The surgeon uses the articulating vessel sealer to create pedicles as described above. Once progress is made to the level of the Koh ring, the vessel sealer is replaced with the scissor and the scissors are used to complete the circumferential colpotomy.

The vast majority of two-port hysterectomy specimens will be removed transvaginally and intact. For the supracervical approach, endoscopic morcellation is applied. With TLH and large uteri, endoscopic or traditional transvaginal morcellation may be applied. If morcellation is performed endoscopically, the robotic patient cart is undocked, the camera is moved to the mediolateral 8-mm port, and the morcellator of choice is placed midline through an expanded umbilical incision.

Following removal of the uterus, the mega suture-cut needle driver and barbed suture are used to close the vaginal cuff. Successful vaginal cuff closure with the two-port technique requires coordinated teamwork between the surgeon and an experienced first assistant. Closure is facilitated with the first assistant grasping the anterior and then the posterior cuff close to the point of needle entry that is chosen by the surgeon.

Throughout the case, suction-irrigation and passing of suture are carried out by temporarily removing the robotic instrument in the 8-mm mediolateral port.

Single-site technique

Patient positioning, placement of the uterine manipulator, and insufflation are again all performed as described for the multisite technique.

The single-site port is placed via an approximately 2-cm incision (Omega, Arch or Z type) through the umbilicus with the arrow displayed on the port pointed toward the target organ. The single-site port accommodates insufflation tubing, an 8-mm camera, two 5-mm operative instruments, and an assistant instrument; all are placed through preordained, standardized lumens (see image 6).

The surgical cart is straight or side docked on the patient’s right side. The cannulas labeled "1" and "2" are docked to robotic arms "1" and "2."

The new single-site tool set differs from instrumentation used in multisite and dual-site procedures in that the operative instruments do not have articulating wrists. Instead, they are flexible and semirigid, allowing them to fit through the curved cannulas to facilitate operative triangulation.

The aesthetic umbilical port placement used in the single-site platform should allow the completion of hysterectomy in uteri with straightforward pathology up to approximately a 14-week size.

The lateral attachments are isolated, secured, and transected as previously described utilizing the 5-mm bipolar Maryland forceps and the 5-mm monopolar hook. Additional presentation and retraction of tissue are performed by the first assistant.

Development of the bladder flap and the anterior and posterior colpotomy are performed just as they are in the multisite and dual-site techniques. If needed, internal swapping of the bipolar and the hook may facilitate more precision during right- and left-side dissections.

Uterine arteries are also dissected in an identical fashion, with internal swapping of instruments facilitating a more precise right and left dissection if needed.

The vast majority of single-site hysterectomy specimens will be removed transvaginally intact. In the supracervical approach or with larger uteri, a transumbilical approach using traditional morcellation can be used. The robotic patient side cart is undocked, the single-site port is removed, and a retractor (the Mini Mobius retractor by CooperSurgical or the extra small Alexis retractor by Applied Medical in Rancho Santa Margarita, Calif.) is inserted.

The specimen is then removed utilizing traditional instruments (i.e., knife, tenaculum, Mayo scissors). Visual "in-line" endoscopic morcellation is not recommended.

The absence of articulating wrists does add some difficulty to the vaginal cuff closure when compared to the multisite platform. We found use of the 5-mm curved needle driver combined with a Keith needle to be highly effective and time efficient (see image 7). Throughout the procedure, suction and irrigation are performed with a 5-mm instrument and suture passage is carried out via the assistant port.

The new robotic single-site instrumentation maintains advantages compared with traditional laparoscopic instrumentation. High-definition three-dimensional visualization, tremor-free instrument movement and surgeon ergonomics are distinct advantages. Other benefits include curved cannulas that restore triangulation and software that reassigns the instruments visualized on the right and left sides to the right and left hands, making hand-eye orientation fluid and intuitive.

Dr. Payne reported that he is a member of the speakers’ bureau for both Intuitive Surgical and CooperSurgical. He would like to acknowledge Dr. Devin Garza, Dr. Sherry Neyman, and Dr. Christopher Seeker for their collaboration and contributions to development of the dual-site approach, and Dr. Garza, Dr. Neyman, and Dr. Lisa Jukes for their contributions to the single-site technique.

Robotic-assisted surgery has been both celebrated as "revolutionary" and defamed as a "crutch." No matter where your loyalties lie in this debate, what is not debatable is the dramatic increase in minimally invasive surgery (MIS) rates for hysterectomy since robotic-assisted surgery was approved for gynecology in 2005. Rates vary across samples and sources, but according to 2011 data from Solucient and 2010 data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, approximately 27% of hysterectomies are performed with the robot, 26% with standard laparoscopy, and 12% vaginally.

It should be clear to all in 2013 that a total abdominal hysterectomy approach (TAH) is the least favored route for hysterectomy in terms of global cost, invasiveness, and overall complication rate. Therefore, as the AAGL has stated, we should all strive to improve our MIS skill-set – whether it is by the vaginal, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approach (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Personally, I prefer robotic-assisted techniques. As a community gynecologist, I believe that the marriage of high-tech computerization with the surgical sciences allows for more reproducibility than the traditional vaginal or laparoscopic approaches (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:286-91; Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:535-42).

In my experience, there are now three reproducible techniques for performing robotic-assisted hysterectomy. The first is a robotic total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) technique involving 4-5 ports, which incorporates some of the steps familiar to surgeons performing TAH. This approach was initially described by Dr. Charles Koh after the advent of the Koh colpotomizer (J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 1998;5:187-92) and was then modified and adapted to the robotic platform with my colleagues at the Ochsner Clinic in Louisiana.

The second is a reduced two-port technique that was developed last year with my colleagues at the Texas Institute for Robotic Surgery in Austin.

Last, clearance by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2013 for a da Vinci single-site instrumentation package for use in benign hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy makes the single-site technique a third reproducible approach for performing hysterectomy with the robotic platform. Use of the instrumentation package is currently being launched at Celebration Health Florida Hospital, the Cleveland Clinic, Newark (N.J.) Beth Israel Medical Center, and the Texas Institute for Robotic Surgery.

In addition to being more reproducible, the robotic route to hysterectomy now affords a "see-and-treat" approach, by which we can insert an endoscopic camera, assess the difficulty of the operation (pathology, uterine size, adhesions, etc.), and then select the robotic technique that is best for the patient.

Multisite technique

In positioning the patient, precautions are taken to prevent patient slippage on the operating table during steep Trendelenburg. Most commonly, we place a gel pad or egg crate mattress directly onto the operating table, secure it with tape, and follow with direct placement of the patient onto the gel pad or egg crate. The patient’s arms are then padded and tucked by the sides and the legs are placed in Allen stirrups.

The actual procedure is begun by placing the uterine manipulator of choice. I prefer the RUMI II System with articulating tip or the Advincula Arch with the Koh colpotomizer ring (CooperSurgical, Trumball, Conn.). Other popular options are the VCare manipulator with cup (ConMed Endosurgery, Utica, N.Y.) and the McCarus-Volker Fornisee (LSI Solutions, Victor, N.Y.).

The vaginal pneumo-occlusion balloon can be placed on all three manipulators and is critical for maintaining the pneumoperitoneum that allows for the success of this technique. The importance of properly placing the uterine manipulator of your choice cannot be overemphasized.

For insufflation, I use a Veress needle placed intraumbilically or in the left upper quadrant (LUQ), depending on the patient’s surgical history. The LUQ is preferred if the patient has a history of a prior midline incision. (The stomach must be desufflated first.) The intraumbilical approach is preferred if the patient has a history of LUQ or bariatric surgery.

For port placement, the 8-mm camera port can be placed 8-10 cm above the fundus of the uterus when pushed cephalad on examination under anesthesia (EUA). The robotic camera or a separate camera with a 5-mm laparoscope is introduced (hand-held), and a four-quadrant inspection is undertaken. Direct visualization is used to place two or three additional 8-mm ports in an arch configuration. An 8-mm assistant port is placed on the patient’s side opposite the surgeon’s dominant hand. All ports are spaced 8-10 cm away from each other.

The patient is placed in sufficiently steep Trendelenburg to allow the small bowel to be displaced from the pelvis. The surgical cart is straight docked between the patient’s legs or side docked on the surgeon’s dominant hand side. The 8-mm camera is placed into the camera arm, and then two or three (per the surgeon’s preference) 8-mm robotic instruments are placed under direct visualization.

I prefer to use three instruments during the procedure: the fenestrated bipolar grasper, the monopolar scissors, and the mega suture-cut needle driver.

The ureters are identified. Retroperitoneal dissection is utilized to confirm the ureteral path if needed. Depending on the patient’s desires and history, salpingectomy may be performed.

Isolation and transection of the infundibulopelvic ligaments or the utero-ovarian ligaments are then undertaken. The dissection is carried to the middle of the round ligament, well away from the uterus (where you would place suture when performing TAH). The round ligament is transected, allowing the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament to separate and be visualized. These initial steps will secure two of the four main blood supplies, avoid early uterine artery bleeding, and maximize uterine mobility with larger uteri.

To outline the bladder flap, the location of the Koh ring, VCare cup, or McCarus-Volker Fornisee at the cervicovaginal junction should be noted and used as a general target. The bladder is then filled through the Foley to confirm its location and is then emptied. The anterior leaf of the broad ligament is then picked up and tented with the fenestrated bipolar grasper.

The monopolar scissors are employed to incise the anterior leaf from where the round ligament was transected to the area just cephalad of the cervicovaginal ring and the border of the bladder, in a fashion similar to TAH. Each of these steps is performed bilaterally.

Next, in preparation for the anterior colpotomy, further development of the bladder flap is necessary. Aggressive and continuous cephalad pressure of the uterine manipulator with the ring/cup is critical to create a clear delineation of the cervicovaginal junction. Creation of the bladder flap is then completed in the caudad direction approximately 1-2 cm over the ring/cup (see image 2).

The anterior colpotomy is initiated with the posterior displacement of the uterine fundus using the RUMI II articulating tip (CooperSurgical) by rotating the handle counterclockwise. This movement simultaneously allows for pressure and emphasis to be placed on the anterior portion of the Koh ring.

Using a clockface as the reference, the anterior colpotomy is initiated at the 12 o’clock position with the monopolar scissors (settings: 30 watts). Once the ring/cup is successfully identified, the colpotomy is extended from the 12 o’clock position to the 2 o’clock and 10 o’clock positions, stopping to avoid the uterine arteries bilaterally.

To begin the posterior colpotomy, the uterine fundus is repositioned anteriorly while maintaining aggressive, continuous cephalad pressure. Again, the RUMI II allows for anterior displacement of the uterine fundus with posterior pressure and emphasis on the Koh ring by turning its handle – this time in the clockwise direction. The posterior colpotomy is initiated at the 6 o’clock position and extended upward to the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions, stopping to avoid the uterine arteries bilaterally.

For taking down the uterine arteries, the optimal placement of the uterus is a midplane position. A clear view of the uterine sidewall is created with retraction using a grasper on the remnant of the round ligament. While maintaining this view, the uterine artery is grasped, cauterized, and transected high up on the uterine sidewall.

The initial pedicle is created well away from the ring/cup in a fashion similar to the placement of a curved Heaney clamp when performing a TAH (see image 3).

Subsequently, each pedicle is then cauterized and transected close to the uterine sidewall, allowing it to fall away from the uterus as progress toward the vaginal ring/cup is made. This portion of the procedure is similar to creating pedicles with straight Heaney clamps during a TAH. Aggressive cephalad pressure is placed on the uterine manipulator and cup throughout the process, further allowing the ureters to fall away with the formation of each pedicle. Upon reaching the vaginal ring/cup, the circumferential colpotomy is completed at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions.

The specimen is then removed intact transvaginally or is morcellated. Large uteri may be morcellated endoscopically or may be removed by traditional vaginal morcellation techniques to avoid additional costs.

To decrease the chances of vaginal cuff dehiscence, it is critical to use low monopolar energy settings, create appropriate tension to allow efficient and quick colpotomies, and create an adequate bladder flap to allow incorporation of 1-2 cm of vaginal cuff tissue in the closure.

Common techniques for cuff closure include tying the suture with figure-of-eight stitches, running the suture with Lapra-Ty anchors (Ethicon Endosurgery, Nokesville, Va.), or completing the closure with barbed suture.

Dual-site technique

Patient positioning, placement of the uterine manipulator, and insufflation are all performed as previously described. However, with the two-port technique we strongly recommend using the RUMI II, which provides an added degree of manipulation as a result of its articulating tip.

The 8-mm camera port is placed midline 8-10 cm above the uterine fundus when pushed cephalad during EUA. Following the arched port arrangement described above, one additional 8-mm port is placed on the surgeon’s dominant hand side 8-10 cm lateral to the camera port in the mediolateral position. A 2-mm portless alligator grasper is placed 8-10 cm from the camera port on the opposite side (the surgeon’s nondominant side) in the mediolateral position after the robotic surgical system is docked.

The surgical cart is side docked on the surgeon’s dominant hand side, which is the same side as the working port for the robotic instrument. The 8-mm camera is then placed into the camera port and the endowrist one vessel sealer is placed under direct visualization into the robotic working port. Next, the 2-mm alligator grasper is punched through the dermis in needlelike fashion under direct visualization in the location as just described.

(For the system to correctly count instrument lives in the active robotic instrument arm, a "dummy" trocar [locked into the robotic arm but not inserted into the patient’s abdomen] must be placed into an inactive robotic arm opposite the vessel sealer.)

We use the camera arm and one robotic arm for this technique and employ three robotic instruments and a portless 2-mm grasper. Currently, we have successfully performed the two-port technique on uteri up to 16 weeks without the use of additional arms or open conversion.

The order of steps to complete the dual-site hysterectomy generally resembles that of the multisite approach, with several nuances.

The technique for lateral attachments is generally the same, except that the surgeon employs an articulating endowrist one vessel sealer for sealing and cutting tissue, while the first assist uses the 2-mm alligator grasper to proactively present and retract the adnexa for the surgeon (see image 4).

Once the round ligaments are transected, the vessel sealer is replaced with the monopolar scissors. The first assist uses the 2-mm grasper to tent the anterior leaf of the broad ligament, and the surgeon utilizes the scissors to outline and develop the bladder flap as described above. An advanced uterine manipulation skill-set is highly recommended.

After the development of the bladder flap is completed, the anterior and posterior colpotomies are completed as described above (see image 5).

Following completion of the colpotomies, the monopolar scissors are removed and the endowrist one vessel sealer is reinserted. The first assist grasps the round ligament remnant and retracts it to provide a clear view of the uterine sidewall and vessels while cephalad pressure is maintained on the manipulator. The surgeon uses the articulating vessel sealer to create pedicles as described above. Once progress is made to the level of the Koh ring, the vessel sealer is replaced with the scissor and the scissors are used to complete the circumferential colpotomy.

The vast majority of two-port hysterectomy specimens will be removed transvaginally and intact. For the supracervical approach, endoscopic morcellation is applied. With TLH and large uteri, endoscopic or traditional transvaginal morcellation may be applied. If morcellation is performed endoscopically, the robotic patient cart is undocked, the camera is moved to the mediolateral 8-mm port, and the morcellator of choice is placed midline through an expanded umbilical incision.

Following removal of the uterus, the mega suture-cut needle driver and barbed suture are used to close the vaginal cuff. Successful vaginal cuff closure with the two-port technique requires coordinated teamwork between the surgeon and an experienced first assistant. Closure is facilitated with the first assistant grasping the anterior and then the posterior cuff close to the point of needle entry that is chosen by the surgeon.

Throughout the case, suction-irrigation and passing of suture are carried out by temporarily removing the robotic instrument in the 8-mm mediolateral port.

Single-site technique

Patient positioning, placement of the uterine manipulator, and insufflation are again all performed as described for the multisite technique.

The single-site port is placed via an approximately 2-cm incision (Omega, Arch or Z type) through the umbilicus with the arrow displayed on the port pointed toward the target organ. The single-site port accommodates insufflation tubing, an 8-mm camera, two 5-mm operative instruments, and an assistant instrument; all are placed through preordained, standardized lumens (see image 6).

The surgical cart is straight or side docked on the patient’s right side. The cannulas labeled "1" and "2" are docked to robotic arms "1" and "2."

The new single-site tool set differs from instrumentation used in multisite and dual-site procedures in that the operative instruments do not have articulating wrists. Instead, they are flexible and semirigid, allowing them to fit through the curved cannulas to facilitate operative triangulation.

The aesthetic umbilical port placement used in the single-site platform should allow the completion of hysterectomy in uteri with straightforward pathology up to approximately a 14-week size.

The lateral attachments are isolated, secured, and transected as previously described utilizing the 5-mm bipolar Maryland forceps and the 5-mm monopolar hook. Additional presentation and retraction of tissue are performed by the first assistant.

Development of the bladder flap and the anterior and posterior colpotomy are performed just as they are in the multisite and dual-site techniques. If needed, internal swapping of the bipolar and the hook may facilitate more precision during right- and left-side dissections.

Uterine arteries are also dissected in an identical fashion, with internal swapping of instruments facilitating a more precise right and left dissection if needed.

The vast majority of single-site hysterectomy specimens will be removed transvaginally intact. In the supracervical approach or with larger uteri, a transumbilical approach using traditional morcellation can be used. The robotic patient side cart is undocked, the single-site port is removed, and a retractor (the Mini Mobius retractor by CooperSurgical or the extra small Alexis retractor by Applied Medical in Rancho Santa Margarita, Calif.) is inserted.

The specimen is then removed utilizing traditional instruments (i.e., knife, tenaculum, Mayo scissors). Visual "in-line" endoscopic morcellation is not recommended.

The absence of articulating wrists does add some difficulty to the vaginal cuff closure when compared to the multisite platform. We found use of the 5-mm curved needle driver combined with a Keith needle to be highly effective and time efficient (see image 7). Throughout the procedure, suction and irrigation are performed with a 5-mm instrument and suture passage is carried out via the assistant port.

The new robotic single-site instrumentation maintains advantages compared with traditional laparoscopic instrumentation. High-definition three-dimensional visualization, tremor-free instrument movement and surgeon ergonomics are distinct advantages. Other benefits include curved cannulas that restore triangulation and software that reassigns the instruments visualized on the right and left sides to the right and left hands, making hand-eye orientation fluid and intuitive.

Dr. Payne reported that he is a member of the speakers’ bureau for both Intuitive Surgical and CooperSurgical. He would like to acknowledge Dr. Devin Garza, Dr. Sherry Neyman, and Dr. Christopher Seeker for their collaboration and contributions to development of the dual-site approach, and Dr. Garza, Dr. Neyman, and Dr. Lisa Jukes for their contributions to the single-site technique.

Robotic-assisted surgery has been both celebrated as "revolutionary" and defamed as a "crutch." No matter where your loyalties lie in this debate, what is not debatable is the dramatic increase in minimally invasive surgery (MIS) rates for hysterectomy since robotic-assisted surgery was approved for gynecology in 2005. Rates vary across samples and sources, but according to 2011 data from Solucient and 2010 data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, approximately 27% of hysterectomies are performed with the robot, 26% with standard laparoscopy, and 12% vaginally.

It should be clear to all in 2013 that a total abdominal hysterectomy approach (TAH) is the least favored route for hysterectomy in terms of global cost, invasiveness, and overall complication rate. Therefore, as the AAGL has stated, we should all strive to improve our MIS skill-set – whether it is by the vaginal, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approach (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1-3).

Personally, I prefer robotic-assisted techniques. As a community gynecologist, I believe that the marriage of high-tech computerization with the surgical sciences allows for more reproducibility than the traditional vaginal or laparoscopic approaches (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:286-91; Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:535-42).

In my experience, there are now three reproducible techniques for performing robotic-assisted hysterectomy. The first is a robotic total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) technique involving 4-5 ports, which incorporates some of the steps familiar to surgeons performing TAH. This approach was initially described by Dr. Charles Koh after the advent of the Koh colpotomizer (J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 1998;5:187-92) and was then modified and adapted to the robotic platform with my colleagues at the Ochsner Clinic in Louisiana.

The second is a reduced two-port technique that was developed last year with my colleagues at the Texas Institute for Robotic Surgery in Austin.

Last, clearance by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2013 for a da Vinci single-site instrumentation package for use in benign hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy makes the single-site technique a third reproducible approach for performing hysterectomy with the robotic platform. Use of the instrumentation package is currently being launched at Celebration Health Florida Hospital, the Cleveland Clinic, Newark (N.J.) Beth Israel Medical Center, and the Texas Institute for Robotic Surgery.

In addition to being more reproducible, the robotic route to hysterectomy now affords a "see-and-treat" approach, by which we can insert an endoscopic camera, assess the difficulty of the operation (pathology, uterine size, adhesions, etc.), and then select the robotic technique that is best for the patient.

Multisite technique

In positioning the patient, precautions are taken to prevent patient slippage on the operating table during steep Trendelenburg. Most commonly, we place a gel pad or egg crate mattress directly onto the operating table, secure it with tape, and follow with direct placement of the patient onto the gel pad or egg crate. The patient’s arms are then padded and tucked by the sides and the legs are placed in Allen stirrups.

The actual procedure is begun by placing the uterine manipulator of choice. I prefer the RUMI II System with articulating tip or the Advincula Arch with the Koh colpotomizer ring (CooperSurgical, Trumball, Conn.). Other popular options are the VCare manipulator with cup (ConMed Endosurgery, Utica, N.Y.) and the McCarus-Volker Fornisee (LSI Solutions, Victor, N.Y.).

The vaginal pneumo-occlusion balloon can be placed on all three manipulators and is critical for maintaining the pneumoperitoneum that allows for the success of this technique. The importance of properly placing the uterine manipulator of your choice cannot be overemphasized.

For insufflation, I use a Veress needle placed intraumbilically or in the left upper quadrant (LUQ), depending on the patient’s surgical history. The LUQ is preferred if the patient has a history of a prior midline incision. (The stomach must be desufflated first.) The intraumbilical approach is preferred if the patient has a history of LUQ or bariatric surgery.

For port placement, the 8-mm camera port can be placed 8-10 cm above the fundus of the uterus when pushed cephalad on examination under anesthesia (EUA). The robotic camera or a separate camera with a 5-mm laparoscope is introduced (hand-held), and a four-quadrant inspection is undertaken. Direct visualization is used to place two or three additional 8-mm ports in an arch configuration. An 8-mm assistant port is placed on the patient’s side opposite the surgeon’s dominant hand. All ports are spaced 8-10 cm away from each other.

The patient is placed in sufficiently steep Trendelenburg to allow the small bowel to be displaced from the pelvis. The surgical cart is straight docked between the patient’s legs or side docked on the surgeon’s dominant hand side. The 8-mm camera is placed into the camera arm, and then two or three (per the surgeon’s preference) 8-mm robotic instruments are placed under direct visualization.

I prefer to use three instruments during the procedure: the fenestrated bipolar grasper, the monopolar scissors, and the mega suture-cut needle driver.

The ureters are identified. Retroperitoneal dissection is utilized to confirm the ureteral path if needed. Depending on the patient’s desires and history, salpingectomy may be performed.

Isolation and transection of the infundibulopelvic ligaments or the utero-ovarian ligaments are then undertaken. The dissection is carried to the middle of the round ligament, well away from the uterus (where you would place suture when performing TAH). The round ligament is transected, allowing the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament to separate and be visualized. These initial steps will secure two of the four main blood supplies, avoid early uterine artery bleeding, and maximize uterine mobility with larger uteri.

To outline the bladder flap, the location of the Koh ring, VCare cup, or McCarus-Volker Fornisee at the cervicovaginal junction should be noted and used as a general target. The bladder is then filled through the Foley to confirm its location and is then emptied. The anterior leaf of the broad ligament is then picked up and tented with the fenestrated bipolar grasper.

The monopolar scissors are employed to incise the anterior leaf from where the round ligament was transected to the area just cephalad of the cervicovaginal ring and the border of the bladder, in a fashion similar to TAH. Each of these steps is performed bilaterally.

Next, in preparation for the anterior colpotomy, further development of the bladder flap is necessary. Aggressive and continuous cephalad pressure of the uterine manipulator with the ring/cup is critical to create a clear delineation of the cervicovaginal junction. Creation of the bladder flap is then completed in the caudad direction approximately 1-2 cm over the ring/cup (see image 2).

The anterior colpotomy is initiated with the posterior displacement of the uterine fundus using the RUMI II articulating tip (CooperSurgical) by rotating the handle counterclockwise. This movement simultaneously allows for pressure and emphasis to be placed on the anterior portion of the Koh ring.

Using a clockface as the reference, the anterior colpotomy is initiated at the 12 o’clock position with the monopolar scissors (settings: 30 watts). Once the ring/cup is successfully identified, the colpotomy is extended from the 12 o’clock position to the 2 o’clock and 10 o’clock positions, stopping to avoid the uterine arteries bilaterally.

To begin the posterior colpotomy, the uterine fundus is repositioned anteriorly while maintaining aggressive, continuous cephalad pressure. Again, the RUMI II allows for anterior displacement of the uterine fundus with posterior pressure and emphasis on the Koh ring by turning its handle – this time in the clockwise direction. The posterior colpotomy is initiated at the 6 o’clock position and extended upward to the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions, stopping to avoid the uterine arteries bilaterally.

For taking down the uterine arteries, the optimal placement of the uterus is a midplane position. A clear view of the uterine sidewall is created with retraction using a grasper on the remnant of the round ligament. While maintaining this view, the uterine artery is grasped, cauterized, and transected high up on the uterine sidewall.

The initial pedicle is created well away from the ring/cup in a fashion similar to the placement of a curved Heaney clamp when performing a TAH (see image 3).

Subsequently, each pedicle is then cauterized and transected close to the uterine sidewall, allowing it to fall away from the uterus as progress toward the vaginal ring/cup is made. This portion of the procedure is similar to creating pedicles with straight Heaney clamps during a TAH. Aggressive cephalad pressure is placed on the uterine manipulator and cup throughout the process, further allowing the ureters to fall away with the formation of each pedicle. Upon reaching the vaginal ring/cup, the circumferential colpotomy is completed at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions.

The specimen is then removed intact transvaginally or is morcellated. Large uteri may be morcellated endoscopically or may be removed by traditional vaginal morcellation techniques to avoid additional costs.

To decrease the chances of vaginal cuff dehiscence, it is critical to use low monopolar energy settings, create appropriate tension to allow efficient and quick colpotomies, and create an adequate bladder flap to allow incorporation of 1-2 cm of vaginal cuff tissue in the closure.

Common techniques for cuff closure include tying the suture with figure-of-eight stitches, running the suture with Lapra-Ty anchors (Ethicon Endosurgery, Nokesville, Va.), or completing the closure with barbed suture.

Dual-site technique

Patient positioning, placement of the uterine manipulator, and insufflation are all performed as previously described. However, with the two-port technique we strongly recommend using the RUMI II, which provides an added degree of manipulation as a result of its articulating tip.

The 8-mm camera port is placed midline 8-10 cm above the uterine fundus when pushed cephalad during EUA. Following the arched port arrangement described above, one additional 8-mm port is placed on the surgeon’s dominant hand side 8-10 cm lateral to the camera port in the mediolateral position. A 2-mm portless alligator grasper is placed 8-10 cm from the camera port on the opposite side (the surgeon’s nondominant side) in the mediolateral position after the robotic surgical system is docked.