User login

Twins

Pregnancies involving multiple births are an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in most obstetrical practices, with twin gestations now accounting for more than 3% of all births in the United States.

The incidence of twinning is attributable to two main social factors: older maternal age at childbirth, which is responsible for a third of the increase, and the increased use of assisted reproductive technology (ART), which is responsible for the other two-thirds.

Although refinements in ART and recommendations to limit the number of embryos transferred during in vitro procedures have led to reductions in the number of higher-order multiples, twin gestations are still common, occurring in up to one-third of IVF pregnancies. Ovulation induction, which is a much more commonly used ART procedure, is also associated with twinning rates of 5%-10%.

What must be appreciated is the reality that twin gestations carry significant risks and contribute disproportionately to our national rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Although twin gestations represent just over 3% of all live births, they account for 15% of all early preterm births and 25% of all very-low birth weight infants.

Approximately 15% of all neonates with respiratory distress syndrome are twins, and twins account for 12% of all cases of grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage. Of all neonatal deaths in the United States, approximately 15% are twins. Moreover, approximately 10% of all stillbirths in the United States are twins.

In short, twin gestations are one of the most common high-risk conditions in obstetrical practice. Twin pregnancies are usually exciting for parents and their families, but it is important to reflect on the significant risks they can present, and to consider how these pregnancies can be optimally managed in order to reduce these risks.

No Simple Diagnosis

The first step in the optimal management of twins is to make the early diagnosis of chorionicity. The American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology ran a striking editorial about the significance of establishing chorionicity by first-trimester ultrasound in multiple gestations. The editorial’s authors, Dr. Kenneth J. Moise Jr. and Dr. Anthony Johnson, reflected on a talk given by Dr. Krypos Nicolaides of King’s College London, in which he broke away from his discussion of fetal therapy, paused, and made the following statement:

"There is NO diagnosis of twins. There are only monochorionic twins or dichorionic twins. This diagnosis should be written in capital red letters across the top of the patient’s chart." (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203:1-2).

It could not have been better stated. It is not appropriate in obstetrical medicine to make a simple diagnosis of "twins" any longer. Early identification of whether a twin gestation involves either a monochorionic, single-placenta placentation, or a dichorionic, dual-placenta placentation is essential for accurate risk assessment and optimal antepartum management. Monochorionic pregnancies, which represent just over 20% of all twin gestations, are at much greater risk for miscarriage, congenital anomalies, growth abnormalities (including twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome), preterm birth, stillbirth, and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

Determining this single feature – the chorionicity of the twin gestations – will thus shape a host of decisions, from the frequency of ultrasound examinations to the type of late-pregnancy surveillance and the timing of delivery.

With proper training, chorionicity can be determined with almost 100% accuracy in the first trimester, and if a patient doesn’t present in the first trimester, it still can be determined in the second trimester with an accuracy approaching 100% using a variety of ultrasound markers and parameters.

Optimizing Nutrition

I firmly believe that maximizing the mother’s nutrition is one of the most important determinants of a healthy outcome in a twin pregnancy.

In its 2009 report titled "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines," the Institute of Medicine for the first time offered body mass index–specific recommendations for women with multiple gestations. The IOM has long had recommendations for singleton pregnancies based on pregravid BMI status, but this latest report marked the first time that multiple pregnancies were addressed in such detail.

Clearly, our knowledge base has advanced. During the 1990s and 2000s, a number of investigators – most notably Barbara Luke, Sc.D., currently a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Michigan State University, East Lansing – have published articles on the role of nutrition and weight gain in women with multiple gestations, and the relationship of these factors to pregnancy outcomes. Studies have demonstrated the critical effect that appropriate maternal weight gain and optimal nutrition have on twin fetal growth, birth weight, length of gestation, and other outcomes.

Surprisingly, the IOM consensus panel did not issue recommendations for women who are underweight, citing a lack of evidence. I believe there is clear epidemiologic evidence, however, that women with twin pregnancies who are underweight before pregnancy and have poor gestational weight gain are at the highest risk for poor outcomes.

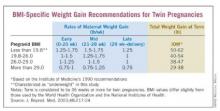

In a 2003 report, Dr. Luke and a team of investigators, myself included, developed BMI-specific weight gain guidelines for optimal birth weights in twin pregnancies. Our weight gain curves and recommendations, which were based on a multi-institution cohort study of 2,324 twin pregnancies, are similar to the IOM’s guidelines. We also addressed the category of underweight women, however, and advised a gain of 50-62 pounds for these women. (See box.)

Women with a pregravid underweight status who had a total weight gain within this range experienced optimal fetal growth and birth weight. (J. Reprod. Med. 2003;48:217-24).

In a separate follow-up study of the value of using these BMI-specific weight gain goals, Dr. William Goodnight and I found that in our twins clinic, women who failed to achieve their BMI-specific weight-gain goals had a lower birth weight by nearly 200 g per twin and a length of gestation that was 1 week shorter than that of women who met weight gain goals (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;195[suppl]:S121).

As we described in a review published in 2009, achieving twin weight-gain goals should be part of a comprehensive approach to nutrition that also includes an appropriate caloric intake (3,000-4,000 kcal/day in underweight to normal weight women); supplementation with calcium, magnesium, folate, and zinc (beyond a usual prenatal vitamin); and a nutrient-dense diet that is high in iron-rich proteins and omega-3 fatty acids (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1121-34). In our practice, we emphasize the value of meat protein and of low-mercury fish.

Dr. Luke, who has coauthored a book with Tamara Eberlein that we often recommend to our patients, titled "When Youre Expecting Twins, Triplets or Quads" (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), has best demonstrated the extent to which intensive nutritional counseling and follow-up pays off in twin pregnancies.

In a cohort study published in 2003, she enrolled 190 women with twin pregnancies in a specialized prenatal program that involved twice-monthly visits for nutritional counseling and monitoring. Women were prescribed a diet of 3,000-4,000 kcal/day, with 20% of calories from protein, 40% from carbohydrates, and 40% from fat, as well as multimineral supplementation. The women were monitored for adequate weight gain and had serial ultrasound assessments.

Compared with 339 women with twin pregnancies who were followed by their physicians at the University of Michigan but not enrolled in the program, the program participants had significantly longer gestations (about a week), higher birth weights (220 g), a 23% reduction in preterm births, and significant reductions in preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, preeclampsia, ICU admission, and other poor outcomes.

Overall, the incidence of major neonatal morbidity was 17% for the nutritional program participants, compared with 32% for those women who did not receive the specialized care (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189:934-8).

Measuring Cervical Length

One of the major clinical concerns with any twin pregnancy is the prevention of preterm birth and, by extension, the identification of those women with twins who, within this broader high-risk category, are at greatest risk for preterm birth.

Since the mid-1990s, research has shown that a short cervix detected in the midtrimester (defined as 16-24 weeks) by transvaginal ultrasound is a powerful predictor of preterm birth in women with either singleton or twin gestations. Studies of twin gestations have shown that as cervical length shortens to 25 mm or less, the risk of subsequent preterm birth (defined less than 34 weeks) rises dramatically.

In a report on twin pregnancies from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, for instance, Dr. R.L. Goldenberg and associates demonstrated that cervical length less than or equal to 25 mm at 24 weeks was the best predictor of spontaneous preterm birth. In fact, of all 50 potential risk factors that were studied, a short cervix was the only factor that was consistently associated with preterm birth. The investigators also noted that this shorter cervical length was more common at both 24 and 28 weeks in twins, compared with singleton pregnancies (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996;175:1047-53).

Through the 1990s and the next decade, investigators searched for a viable intervention. However, in numerous studies, the use of cerclage in mothers of twins with a short cervix was found to be of no benefit. Prophylactic tocolysis also failed to prevent preterm birth in published studies.

The use of bed rest has remained controversial. It is commonly prescribed to prevent preterm birth in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix, despite the fact that we have no published data demonstrating its effectiveness in prolonging pregnancy. Personally, I believe that bed rest can reduce the frequency of uterine contractions and help protect the cervix from the weight of the pregnancy.

Interest in the treatment of twin pregnancies with progesterone had waned after 2007, when a National Institutes of Health multicenter, randomized trial of injectable progesterone reported that 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate did not reduce the rate of twin preterm birth (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:454-61).

However, progesterone recently has reemerged as a treatment for women who are at higher risk of preterm birth, based on the publication this year of Dr. Roberto Romero’s review and meta-analysis of vaginal progesterone for women with a sonographic short cervix (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;206:124.e1-19). Indeed, this review provides the first evidence of a beneficial effect in women with a short cervix who are carrying a twin gestation. The meta-analysis covered five prospective, randomized trials of vaginal progesterone with a total of 775 women who had a sonographically confirmed short cervix (25 mm or less) in the midtrimester. The vast majority of women in these studies carried singleton pregnancies, but two of the studies enrolled twin as well as singleton gestations, and one of the five studies – albeit a small one – focused solely on twin pregnancies.

Overall, treatment with vaginal progesterone was associated with a highly significant 42% reduction in the rate of preterm birth at less than 33 weeks. Among twin gestations specifically, the reduction in preterm birth was 30% – a meaningful trend, but not statistically significant. When it came to neonatal morbidity and mortality, however, the effect of vaginal progesterone among twin gestations was far more striking: The group that received vaginal progesterone had a 48% reduction in the risk of composite neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Admittedly, a primary randomized, controlled trial in twin gestations is still needed. In the meantime, however, given the tremendous risk faced by women with a twin gestation and a short cervix, and the lack of any other proven treatment, I believe that vaginal progesterone (Prometrium, in either a 200-mg suppository or 90-mg gel) is an appropriate treatment for this condition.

In our practice, we routinely perform transvaginal cervical-length measurements with our twin pregnancies at the time of their anatomical survey at 18-20 weeks, and then every 2-4 weeks (depending on how short the cervix is) up to 26-28 weeks. If a short cervix is diagnosed, we restrict activity and start vaginal progesterone.

Surveillance, Delivery

Careful surveillance during the late gestational period is critical, as twins – particularly monochorionic twins – are at increased risk of growth restriction or growth discordancy, and have an increased risk of developing abnormalities in amniotic fluid volume. Compared with singletons, twins also are at increased risk of stillbirth in the third trimester; this risk, again, appears to be higher for monochorionic gestations.

We perform routine ultrasound evaluations every 3 weeks for our monochorionic twins and every 4 weeks for our dichorionic twins, in the absence of any abnormalities. If abnormalities in growth are suspected with standard ultrasound evaluation, we add umbilical artery Doppler studies to further assess well-being. We also routinely institute fetal nonstress testing at 32 weeks’ gestation for monochorionic twins and at 34 weeks for our dichorionic twins. Additional strategies are employed as necessary.

The overall risk of stillbirth for twin gestations is 0.2%-0.4% per week after 32 weeks’ gestation, and rises further beyond 38 weeks – a risk that makes surveillance critical.

Some investigators, however, have recently reported higher-than-expected stillbirth rates for "apparently uncomplicated" monochorionic twin gestations. This risk has ranged from 1% to 4% at 32 and 38 weeks’ gestation in various reports.

These studies were debated as part of a workshop held in 2011 by the National Institutes of Health and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on the "Timing of Indicated Late Preterm and Early Term Births." The findings of the higher stillbirth rates remain controversial, but on the basis of these concerns, it was recommended that monochorionic twins – even "uncomplicated" cases – should be offered elective delivery at 34-37 weeks’ gestation, with decisions made after careful discussion and informed consent.

Uncomplicated dichorionic twins, on the other hand, appear to have optimal outcomes when delivered at 38 weeks’ gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:323-3; Semin. Perinatol. 2011;35:277-85).

Recommended surveillance and delivery of monoamniotic twins – a rare but serious type of monochorionic twin gestation – has evolved recently in favor of intensive inpatient monitoring.

The benefits of hospitalization were demonstrated most strikingly in a multicenter cohort study that compared 43 women who were admitted at a median gestational age of 26.5 weeks for inpatient fetal testing two to three times daily vs. 44 women who were followed as outpatients with fetal testing one to three times weekly.

There were no stillbirths in the hospitalized group, but there was a 15% stillbirth rate in the outpatient group. The inpatient group also had significant improvements in birth weight, gestational age at delivery, and neonatal morbidity (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;192:96-101).

This and other evidence suggests that mothers of monoamniotic twins have the best possible outcome when their pregnancies are managed in a hospital setting with fetal monitoring two to three times a day, starting at 24-26 weeks’ gestation, with delivery timed between 32 and 34 weeks’ gestation. This was among the conclusions of the 2011 NIH-SMFM workshop.

Specialized Care

A final consideration regarding the antepartum care of multiples would be the benefit that might be achieved by establishing a specialized twins clinic.

The literature includes numerous reports, including one of our own (Semin. Perinatol 1995;19:387-403), describing improved perinatal outcomes for twins who are cared for by multidisciplinary teams using best practice protocols. Our team includes an obstetrician, a certified nurse-midwife, a nutritionist, an ultrasonographer, and a perinatal nurse.

In our experience, this approach significantly reduces perinatal mortality, primarily by reducing preterm premature rupture of membranes and very low birth weight delivery.

Dr. Newman is currently a professor and the Maas Chair for Reproductive Sciences in the department of obstetrics and gynecology, and vice chairman for academic affairs and women’s health research at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. He established a multidisciplinary twins clinic in 1989 and since then has provided care for more than 1,000 women with twins. Dr. Rogers said he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Pregnancies involving multiple births are an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in most obstetrical practices, with twin gestations now accounting for more than 3% of all births in the United States.

The incidence of twinning is attributable to two main social factors: older maternal age at childbirth, which is responsible for a third of the increase, and the increased use of assisted reproductive technology (ART), which is responsible for the other two-thirds.

Although refinements in ART and recommendations to limit the number of embryos transferred during in vitro procedures have led to reductions in the number of higher-order multiples, twin gestations are still common, occurring in up to one-third of IVF pregnancies. Ovulation induction, which is a much more commonly used ART procedure, is also associated with twinning rates of 5%-10%.

What must be appreciated is the reality that twin gestations carry significant risks and contribute disproportionately to our national rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Although twin gestations represent just over 3% of all live births, they account for 15% of all early preterm births and 25% of all very-low birth weight infants.

Approximately 15% of all neonates with respiratory distress syndrome are twins, and twins account for 12% of all cases of grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage. Of all neonatal deaths in the United States, approximately 15% are twins. Moreover, approximately 10% of all stillbirths in the United States are twins.

In short, twin gestations are one of the most common high-risk conditions in obstetrical practice. Twin pregnancies are usually exciting for parents and their families, but it is important to reflect on the significant risks they can present, and to consider how these pregnancies can be optimally managed in order to reduce these risks.

No Simple Diagnosis

The first step in the optimal management of twins is to make the early diagnosis of chorionicity. The American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology ran a striking editorial about the significance of establishing chorionicity by first-trimester ultrasound in multiple gestations. The editorial’s authors, Dr. Kenneth J. Moise Jr. and Dr. Anthony Johnson, reflected on a talk given by Dr. Krypos Nicolaides of King’s College London, in which he broke away from his discussion of fetal therapy, paused, and made the following statement:

"There is NO diagnosis of twins. There are only monochorionic twins or dichorionic twins. This diagnosis should be written in capital red letters across the top of the patient’s chart." (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203:1-2).

It could not have been better stated. It is not appropriate in obstetrical medicine to make a simple diagnosis of "twins" any longer. Early identification of whether a twin gestation involves either a monochorionic, single-placenta placentation, or a dichorionic, dual-placenta placentation is essential for accurate risk assessment and optimal antepartum management. Monochorionic pregnancies, which represent just over 20% of all twin gestations, are at much greater risk for miscarriage, congenital anomalies, growth abnormalities (including twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome), preterm birth, stillbirth, and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

Determining this single feature – the chorionicity of the twin gestations – will thus shape a host of decisions, from the frequency of ultrasound examinations to the type of late-pregnancy surveillance and the timing of delivery.

With proper training, chorionicity can be determined with almost 100% accuracy in the first trimester, and if a patient doesn’t present in the first trimester, it still can be determined in the second trimester with an accuracy approaching 100% using a variety of ultrasound markers and parameters.

Optimizing Nutrition

I firmly believe that maximizing the mother’s nutrition is one of the most important determinants of a healthy outcome in a twin pregnancy.

In its 2009 report titled "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines," the Institute of Medicine for the first time offered body mass index–specific recommendations for women with multiple gestations. The IOM has long had recommendations for singleton pregnancies based on pregravid BMI status, but this latest report marked the first time that multiple pregnancies were addressed in such detail.

Clearly, our knowledge base has advanced. During the 1990s and 2000s, a number of investigators – most notably Barbara Luke, Sc.D., currently a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Michigan State University, East Lansing – have published articles on the role of nutrition and weight gain in women with multiple gestations, and the relationship of these factors to pregnancy outcomes. Studies have demonstrated the critical effect that appropriate maternal weight gain and optimal nutrition have on twin fetal growth, birth weight, length of gestation, and other outcomes.

Surprisingly, the IOM consensus panel did not issue recommendations for women who are underweight, citing a lack of evidence. I believe there is clear epidemiologic evidence, however, that women with twin pregnancies who are underweight before pregnancy and have poor gestational weight gain are at the highest risk for poor outcomes.

In a 2003 report, Dr. Luke and a team of investigators, myself included, developed BMI-specific weight gain guidelines for optimal birth weights in twin pregnancies. Our weight gain curves and recommendations, which were based on a multi-institution cohort study of 2,324 twin pregnancies, are similar to the IOM’s guidelines. We also addressed the category of underweight women, however, and advised a gain of 50-62 pounds for these women. (See box.)

Women with a pregravid underweight status who had a total weight gain within this range experienced optimal fetal growth and birth weight. (J. Reprod. Med. 2003;48:217-24).

In a separate follow-up study of the value of using these BMI-specific weight gain goals, Dr. William Goodnight and I found that in our twins clinic, women who failed to achieve their BMI-specific weight-gain goals had a lower birth weight by nearly 200 g per twin and a length of gestation that was 1 week shorter than that of women who met weight gain goals (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;195[suppl]:S121).

As we described in a review published in 2009, achieving twin weight-gain goals should be part of a comprehensive approach to nutrition that also includes an appropriate caloric intake (3,000-4,000 kcal/day in underweight to normal weight women); supplementation with calcium, magnesium, folate, and zinc (beyond a usual prenatal vitamin); and a nutrient-dense diet that is high in iron-rich proteins and omega-3 fatty acids (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1121-34). In our practice, we emphasize the value of meat protein and of low-mercury fish.

Dr. Luke, who has coauthored a book with Tamara Eberlein that we often recommend to our patients, titled "When Youre Expecting Twins, Triplets or Quads" (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), has best demonstrated the extent to which intensive nutritional counseling and follow-up pays off in twin pregnancies.

In a cohort study published in 2003, she enrolled 190 women with twin pregnancies in a specialized prenatal program that involved twice-monthly visits for nutritional counseling and monitoring. Women were prescribed a diet of 3,000-4,000 kcal/day, with 20% of calories from protein, 40% from carbohydrates, and 40% from fat, as well as multimineral supplementation. The women were monitored for adequate weight gain and had serial ultrasound assessments.

Compared with 339 women with twin pregnancies who were followed by their physicians at the University of Michigan but not enrolled in the program, the program participants had significantly longer gestations (about a week), higher birth weights (220 g), a 23% reduction in preterm births, and significant reductions in preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, preeclampsia, ICU admission, and other poor outcomes.

Overall, the incidence of major neonatal morbidity was 17% for the nutritional program participants, compared with 32% for those women who did not receive the specialized care (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189:934-8).

Measuring Cervical Length

One of the major clinical concerns with any twin pregnancy is the prevention of preterm birth and, by extension, the identification of those women with twins who, within this broader high-risk category, are at greatest risk for preterm birth.

Since the mid-1990s, research has shown that a short cervix detected in the midtrimester (defined as 16-24 weeks) by transvaginal ultrasound is a powerful predictor of preterm birth in women with either singleton or twin gestations. Studies of twin gestations have shown that as cervical length shortens to 25 mm or less, the risk of subsequent preterm birth (defined less than 34 weeks) rises dramatically.

In a report on twin pregnancies from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, for instance, Dr. R.L. Goldenberg and associates demonstrated that cervical length less than or equal to 25 mm at 24 weeks was the best predictor of spontaneous preterm birth. In fact, of all 50 potential risk factors that were studied, a short cervix was the only factor that was consistently associated with preterm birth. The investigators also noted that this shorter cervical length was more common at both 24 and 28 weeks in twins, compared with singleton pregnancies (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996;175:1047-53).

Through the 1990s and the next decade, investigators searched for a viable intervention. However, in numerous studies, the use of cerclage in mothers of twins with a short cervix was found to be of no benefit. Prophylactic tocolysis also failed to prevent preterm birth in published studies.

The use of bed rest has remained controversial. It is commonly prescribed to prevent preterm birth in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix, despite the fact that we have no published data demonstrating its effectiveness in prolonging pregnancy. Personally, I believe that bed rest can reduce the frequency of uterine contractions and help protect the cervix from the weight of the pregnancy.

Interest in the treatment of twin pregnancies with progesterone had waned after 2007, when a National Institutes of Health multicenter, randomized trial of injectable progesterone reported that 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate did not reduce the rate of twin preterm birth (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:454-61).

However, progesterone recently has reemerged as a treatment for women who are at higher risk of preterm birth, based on the publication this year of Dr. Roberto Romero’s review and meta-analysis of vaginal progesterone for women with a sonographic short cervix (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;206:124.e1-19). Indeed, this review provides the first evidence of a beneficial effect in women with a short cervix who are carrying a twin gestation. The meta-analysis covered five prospective, randomized trials of vaginal progesterone with a total of 775 women who had a sonographically confirmed short cervix (25 mm or less) in the midtrimester. The vast majority of women in these studies carried singleton pregnancies, but two of the studies enrolled twin as well as singleton gestations, and one of the five studies – albeit a small one – focused solely on twin pregnancies.

Overall, treatment with vaginal progesterone was associated with a highly significant 42% reduction in the rate of preterm birth at less than 33 weeks. Among twin gestations specifically, the reduction in preterm birth was 30% – a meaningful trend, but not statistically significant. When it came to neonatal morbidity and mortality, however, the effect of vaginal progesterone among twin gestations was far more striking: The group that received vaginal progesterone had a 48% reduction in the risk of composite neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Admittedly, a primary randomized, controlled trial in twin gestations is still needed. In the meantime, however, given the tremendous risk faced by women with a twin gestation and a short cervix, and the lack of any other proven treatment, I believe that vaginal progesterone (Prometrium, in either a 200-mg suppository or 90-mg gel) is an appropriate treatment for this condition.

In our practice, we routinely perform transvaginal cervical-length measurements with our twin pregnancies at the time of their anatomical survey at 18-20 weeks, and then every 2-4 weeks (depending on how short the cervix is) up to 26-28 weeks. If a short cervix is diagnosed, we restrict activity and start vaginal progesterone.

Surveillance, Delivery

Careful surveillance during the late gestational period is critical, as twins – particularly monochorionic twins – are at increased risk of growth restriction or growth discordancy, and have an increased risk of developing abnormalities in amniotic fluid volume. Compared with singletons, twins also are at increased risk of stillbirth in the third trimester; this risk, again, appears to be higher for monochorionic gestations.

We perform routine ultrasound evaluations every 3 weeks for our monochorionic twins and every 4 weeks for our dichorionic twins, in the absence of any abnormalities. If abnormalities in growth are suspected with standard ultrasound evaluation, we add umbilical artery Doppler studies to further assess well-being. We also routinely institute fetal nonstress testing at 32 weeks’ gestation for monochorionic twins and at 34 weeks for our dichorionic twins. Additional strategies are employed as necessary.

The overall risk of stillbirth for twin gestations is 0.2%-0.4% per week after 32 weeks’ gestation, and rises further beyond 38 weeks – a risk that makes surveillance critical.

Some investigators, however, have recently reported higher-than-expected stillbirth rates for "apparently uncomplicated" monochorionic twin gestations. This risk has ranged from 1% to 4% at 32 and 38 weeks’ gestation in various reports.

These studies were debated as part of a workshop held in 2011 by the National Institutes of Health and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on the "Timing of Indicated Late Preterm and Early Term Births." The findings of the higher stillbirth rates remain controversial, but on the basis of these concerns, it was recommended that monochorionic twins – even "uncomplicated" cases – should be offered elective delivery at 34-37 weeks’ gestation, with decisions made after careful discussion and informed consent.

Uncomplicated dichorionic twins, on the other hand, appear to have optimal outcomes when delivered at 38 weeks’ gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:323-3; Semin. Perinatol. 2011;35:277-85).

Recommended surveillance and delivery of monoamniotic twins – a rare but serious type of monochorionic twin gestation – has evolved recently in favor of intensive inpatient monitoring.

The benefits of hospitalization were demonstrated most strikingly in a multicenter cohort study that compared 43 women who were admitted at a median gestational age of 26.5 weeks for inpatient fetal testing two to three times daily vs. 44 women who were followed as outpatients with fetal testing one to three times weekly.

There were no stillbirths in the hospitalized group, but there was a 15% stillbirth rate in the outpatient group. The inpatient group also had significant improvements in birth weight, gestational age at delivery, and neonatal morbidity (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;192:96-101).

This and other evidence suggests that mothers of monoamniotic twins have the best possible outcome when their pregnancies are managed in a hospital setting with fetal monitoring two to three times a day, starting at 24-26 weeks’ gestation, with delivery timed between 32 and 34 weeks’ gestation. This was among the conclusions of the 2011 NIH-SMFM workshop.

Specialized Care

A final consideration regarding the antepartum care of multiples would be the benefit that might be achieved by establishing a specialized twins clinic.

The literature includes numerous reports, including one of our own (Semin. Perinatol 1995;19:387-403), describing improved perinatal outcomes for twins who are cared for by multidisciplinary teams using best practice protocols. Our team includes an obstetrician, a certified nurse-midwife, a nutritionist, an ultrasonographer, and a perinatal nurse.

In our experience, this approach significantly reduces perinatal mortality, primarily by reducing preterm premature rupture of membranes and very low birth weight delivery.

Dr. Newman is currently a professor and the Maas Chair for Reproductive Sciences in the department of obstetrics and gynecology, and vice chairman for academic affairs and women’s health research at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. He established a multidisciplinary twins clinic in 1989 and since then has provided care for more than 1,000 women with twins. Dr. Rogers said he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Pregnancies involving multiple births are an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in most obstetrical practices, with twin gestations now accounting for more than 3% of all births in the United States.

The incidence of twinning is attributable to two main social factors: older maternal age at childbirth, which is responsible for a third of the increase, and the increased use of assisted reproductive technology (ART), which is responsible for the other two-thirds.

Although refinements in ART and recommendations to limit the number of embryos transferred during in vitro procedures have led to reductions in the number of higher-order multiples, twin gestations are still common, occurring in up to one-third of IVF pregnancies. Ovulation induction, which is a much more commonly used ART procedure, is also associated with twinning rates of 5%-10%.

What must be appreciated is the reality that twin gestations carry significant risks and contribute disproportionately to our national rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Although twin gestations represent just over 3% of all live births, they account for 15% of all early preterm births and 25% of all very-low birth weight infants.

Approximately 15% of all neonates with respiratory distress syndrome are twins, and twins account for 12% of all cases of grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage. Of all neonatal deaths in the United States, approximately 15% are twins. Moreover, approximately 10% of all stillbirths in the United States are twins.

In short, twin gestations are one of the most common high-risk conditions in obstetrical practice. Twin pregnancies are usually exciting for parents and their families, but it is important to reflect on the significant risks they can present, and to consider how these pregnancies can be optimally managed in order to reduce these risks.

No Simple Diagnosis

The first step in the optimal management of twins is to make the early diagnosis of chorionicity. The American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology ran a striking editorial about the significance of establishing chorionicity by first-trimester ultrasound in multiple gestations. The editorial’s authors, Dr. Kenneth J. Moise Jr. and Dr. Anthony Johnson, reflected on a talk given by Dr. Krypos Nicolaides of King’s College London, in which he broke away from his discussion of fetal therapy, paused, and made the following statement:

"There is NO diagnosis of twins. There are only monochorionic twins or dichorionic twins. This diagnosis should be written in capital red letters across the top of the patient’s chart." (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203:1-2).

It could not have been better stated. It is not appropriate in obstetrical medicine to make a simple diagnosis of "twins" any longer. Early identification of whether a twin gestation involves either a monochorionic, single-placenta placentation, or a dichorionic, dual-placenta placentation is essential for accurate risk assessment and optimal antepartum management. Monochorionic pregnancies, which represent just over 20% of all twin gestations, are at much greater risk for miscarriage, congenital anomalies, growth abnormalities (including twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome), preterm birth, stillbirth, and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

Determining this single feature – the chorionicity of the twin gestations – will thus shape a host of decisions, from the frequency of ultrasound examinations to the type of late-pregnancy surveillance and the timing of delivery.

With proper training, chorionicity can be determined with almost 100% accuracy in the first trimester, and if a patient doesn’t present in the first trimester, it still can be determined in the second trimester with an accuracy approaching 100% using a variety of ultrasound markers and parameters.

Optimizing Nutrition

I firmly believe that maximizing the mother’s nutrition is one of the most important determinants of a healthy outcome in a twin pregnancy.

In its 2009 report titled "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines," the Institute of Medicine for the first time offered body mass index–specific recommendations for women with multiple gestations. The IOM has long had recommendations for singleton pregnancies based on pregravid BMI status, but this latest report marked the first time that multiple pregnancies were addressed in such detail.

Clearly, our knowledge base has advanced. During the 1990s and 2000s, a number of investigators – most notably Barbara Luke, Sc.D., currently a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Michigan State University, East Lansing – have published articles on the role of nutrition and weight gain in women with multiple gestations, and the relationship of these factors to pregnancy outcomes. Studies have demonstrated the critical effect that appropriate maternal weight gain and optimal nutrition have on twin fetal growth, birth weight, length of gestation, and other outcomes.

Surprisingly, the IOM consensus panel did not issue recommendations for women who are underweight, citing a lack of evidence. I believe there is clear epidemiologic evidence, however, that women with twin pregnancies who are underweight before pregnancy and have poor gestational weight gain are at the highest risk for poor outcomes.

In a 2003 report, Dr. Luke and a team of investigators, myself included, developed BMI-specific weight gain guidelines for optimal birth weights in twin pregnancies. Our weight gain curves and recommendations, which were based on a multi-institution cohort study of 2,324 twin pregnancies, are similar to the IOM’s guidelines. We also addressed the category of underweight women, however, and advised a gain of 50-62 pounds for these women. (See box.)

Women with a pregravid underweight status who had a total weight gain within this range experienced optimal fetal growth and birth weight. (J. Reprod. Med. 2003;48:217-24).

In a separate follow-up study of the value of using these BMI-specific weight gain goals, Dr. William Goodnight and I found that in our twins clinic, women who failed to achieve their BMI-specific weight-gain goals had a lower birth weight by nearly 200 g per twin and a length of gestation that was 1 week shorter than that of women who met weight gain goals (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;195[suppl]:S121).

As we described in a review published in 2009, achieving twin weight-gain goals should be part of a comprehensive approach to nutrition that also includes an appropriate caloric intake (3,000-4,000 kcal/day in underweight to normal weight women); supplementation with calcium, magnesium, folate, and zinc (beyond a usual prenatal vitamin); and a nutrient-dense diet that is high in iron-rich proteins and omega-3 fatty acids (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1121-34). In our practice, we emphasize the value of meat protein and of low-mercury fish.

Dr. Luke, who has coauthored a book with Tamara Eberlein that we often recommend to our patients, titled "When Youre Expecting Twins, Triplets or Quads" (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), has best demonstrated the extent to which intensive nutritional counseling and follow-up pays off in twin pregnancies.

In a cohort study published in 2003, she enrolled 190 women with twin pregnancies in a specialized prenatal program that involved twice-monthly visits for nutritional counseling and monitoring. Women were prescribed a diet of 3,000-4,000 kcal/day, with 20% of calories from protein, 40% from carbohydrates, and 40% from fat, as well as multimineral supplementation. The women were monitored for adequate weight gain and had serial ultrasound assessments.

Compared with 339 women with twin pregnancies who were followed by their physicians at the University of Michigan but not enrolled in the program, the program participants had significantly longer gestations (about a week), higher birth weights (220 g), a 23% reduction in preterm births, and significant reductions in preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, preeclampsia, ICU admission, and other poor outcomes.

Overall, the incidence of major neonatal morbidity was 17% for the nutritional program participants, compared with 32% for those women who did not receive the specialized care (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189:934-8).

Measuring Cervical Length

One of the major clinical concerns with any twin pregnancy is the prevention of preterm birth and, by extension, the identification of those women with twins who, within this broader high-risk category, are at greatest risk for preterm birth.

Since the mid-1990s, research has shown that a short cervix detected in the midtrimester (defined as 16-24 weeks) by transvaginal ultrasound is a powerful predictor of preterm birth in women with either singleton or twin gestations. Studies of twin gestations have shown that as cervical length shortens to 25 mm or less, the risk of subsequent preterm birth (defined less than 34 weeks) rises dramatically.

In a report on twin pregnancies from the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, for instance, Dr. R.L. Goldenberg and associates demonstrated that cervical length less than or equal to 25 mm at 24 weeks was the best predictor of spontaneous preterm birth. In fact, of all 50 potential risk factors that were studied, a short cervix was the only factor that was consistently associated with preterm birth. The investigators also noted that this shorter cervical length was more common at both 24 and 28 weeks in twins, compared with singleton pregnancies (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996;175:1047-53).

Through the 1990s and the next decade, investigators searched for a viable intervention. However, in numerous studies, the use of cerclage in mothers of twins with a short cervix was found to be of no benefit. Prophylactic tocolysis also failed to prevent preterm birth in published studies.

The use of bed rest has remained controversial. It is commonly prescribed to prevent preterm birth in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix, despite the fact that we have no published data demonstrating its effectiveness in prolonging pregnancy. Personally, I believe that bed rest can reduce the frequency of uterine contractions and help protect the cervix from the weight of the pregnancy.

Interest in the treatment of twin pregnancies with progesterone had waned after 2007, when a National Institutes of Health multicenter, randomized trial of injectable progesterone reported that 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate did not reduce the rate of twin preterm birth (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:454-61).

However, progesterone recently has reemerged as a treatment for women who are at higher risk of preterm birth, based on the publication this year of Dr. Roberto Romero’s review and meta-analysis of vaginal progesterone for women with a sonographic short cervix (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;206:124.e1-19). Indeed, this review provides the first evidence of a beneficial effect in women with a short cervix who are carrying a twin gestation. The meta-analysis covered five prospective, randomized trials of vaginal progesterone with a total of 775 women who had a sonographically confirmed short cervix (25 mm or less) in the midtrimester. The vast majority of women in these studies carried singleton pregnancies, but two of the studies enrolled twin as well as singleton gestations, and one of the five studies – albeit a small one – focused solely on twin pregnancies.

Overall, treatment with vaginal progesterone was associated with a highly significant 42% reduction in the rate of preterm birth at less than 33 weeks. Among twin gestations specifically, the reduction in preterm birth was 30% – a meaningful trend, but not statistically significant. When it came to neonatal morbidity and mortality, however, the effect of vaginal progesterone among twin gestations was far more striking: The group that received vaginal progesterone had a 48% reduction in the risk of composite neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Admittedly, a primary randomized, controlled trial in twin gestations is still needed. In the meantime, however, given the tremendous risk faced by women with a twin gestation and a short cervix, and the lack of any other proven treatment, I believe that vaginal progesterone (Prometrium, in either a 200-mg suppository or 90-mg gel) is an appropriate treatment for this condition.

In our practice, we routinely perform transvaginal cervical-length measurements with our twin pregnancies at the time of their anatomical survey at 18-20 weeks, and then every 2-4 weeks (depending on how short the cervix is) up to 26-28 weeks. If a short cervix is diagnosed, we restrict activity and start vaginal progesterone.

Surveillance, Delivery

Careful surveillance during the late gestational period is critical, as twins – particularly monochorionic twins – are at increased risk of growth restriction or growth discordancy, and have an increased risk of developing abnormalities in amniotic fluid volume. Compared with singletons, twins also are at increased risk of stillbirth in the third trimester; this risk, again, appears to be higher for monochorionic gestations.

We perform routine ultrasound evaluations every 3 weeks for our monochorionic twins and every 4 weeks for our dichorionic twins, in the absence of any abnormalities. If abnormalities in growth are suspected with standard ultrasound evaluation, we add umbilical artery Doppler studies to further assess well-being. We also routinely institute fetal nonstress testing at 32 weeks’ gestation for monochorionic twins and at 34 weeks for our dichorionic twins. Additional strategies are employed as necessary.

The overall risk of stillbirth for twin gestations is 0.2%-0.4% per week after 32 weeks’ gestation, and rises further beyond 38 weeks – a risk that makes surveillance critical.

Some investigators, however, have recently reported higher-than-expected stillbirth rates for "apparently uncomplicated" monochorionic twin gestations. This risk has ranged from 1% to 4% at 32 and 38 weeks’ gestation in various reports.

These studies were debated as part of a workshop held in 2011 by the National Institutes of Health and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine on the "Timing of Indicated Late Preterm and Early Term Births." The findings of the higher stillbirth rates remain controversial, but on the basis of these concerns, it was recommended that monochorionic twins – even "uncomplicated" cases – should be offered elective delivery at 34-37 weeks’ gestation, with decisions made after careful discussion and informed consent.

Uncomplicated dichorionic twins, on the other hand, appear to have optimal outcomes when delivered at 38 weeks’ gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:323-3; Semin. Perinatol. 2011;35:277-85).

Recommended surveillance and delivery of monoamniotic twins – a rare but serious type of monochorionic twin gestation – has evolved recently in favor of intensive inpatient monitoring.

The benefits of hospitalization were demonstrated most strikingly in a multicenter cohort study that compared 43 women who were admitted at a median gestational age of 26.5 weeks for inpatient fetal testing two to three times daily vs. 44 women who were followed as outpatients with fetal testing one to three times weekly.

There were no stillbirths in the hospitalized group, but there was a 15% stillbirth rate in the outpatient group. The inpatient group also had significant improvements in birth weight, gestational age at delivery, and neonatal morbidity (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;192:96-101).

This and other evidence suggests that mothers of monoamniotic twins have the best possible outcome when their pregnancies are managed in a hospital setting with fetal monitoring two to three times a day, starting at 24-26 weeks’ gestation, with delivery timed between 32 and 34 weeks’ gestation. This was among the conclusions of the 2011 NIH-SMFM workshop.

Specialized Care

A final consideration regarding the antepartum care of multiples would be the benefit that might be achieved by establishing a specialized twins clinic.

The literature includes numerous reports, including one of our own (Semin. Perinatol 1995;19:387-403), describing improved perinatal outcomes for twins who are cared for by multidisciplinary teams using best practice protocols. Our team includes an obstetrician, a certified nurse-midwife, a nutritionist, an ultrasonographer, and a perinatal nurse.

In our experience, this approach significantly reduces perinatal mortality, primarily by reducing preterm premature rupture of membranes and very low birth weight delivery.

Dr. Newman is currently a professor and the Maas Chair for Reproductive Sciences in the department of obstetrics and gynecology, and vice chairman for academic affairs and women’s health research at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. He established a multidisciplinary twins clinic in 1989 and since then has provided care for more than 1,000 women with twins. Dr. Rogers said he has no relevant financial disclosures.