User login

Painful swelling of fingers and toe

Although psoriatic arthritis is not the only disease associated with dactylitis — other culprits are sarcoidosis, septic arthritis, tuberculosis, and gout — dactylitis is one of the characteristic symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. Dactylitis is seen in as many as 35% of patients with psoriatic disease. Dactylitis clinically presents — as in this patient — with sausage-like swelling of the digits. It is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as one of the hallmarks of psoriatic arthritis.

Dactylitis has been thought to be a result of the concomitant swelling and inflammation of the flexor tendon sheaths of the metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal, or interphalangeal joints. Flexor tenosynovitis can be detected by examination with MRI and ultrasound. Dactylitis is associated with radiologically evident erosive damage to the joints.

Patients with psoriatic arthritis are typically seronegative for rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody; antinuclear antibody titers in persons with psoriatic arthritis do not differ from those of age- and sex-matched controls. C-reactive protein may be elevated but is often normal. Lack of C-reactive protein elevation, however, does not mean that systemic inflammation is absent, but rather indicates that different markers are needed that allow better quantification of systemic inflammation in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Although psoriatic arthritis is not the only disease associated with dactylitis — other culprits are sarcoidosis, septic arthritis, tuberculosis, and gout — dactylitis is one of the characteristic symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. Dactylitis is seen in as many as 35% of patients with psoriatic disease. Dactylitis clinically presents — as in this patient — with sausage-like swelling of the digits. It is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as one of the hallmarks of psoriatic arthritis.

Dactylitis has been thought to be a result of the concomitant swelling and inflammation of the flexor tendon sheaths of the metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal, or interphalangeal joints. Flexor tenosynovitis can be detected by examination with MRI and ultrasound. Dactylitis is associated with radiologically evident erosive damage to the joints.

Patients with psoriatic arthritis are typically seronegative for rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody; antinuclear antibody titers in persons with psoriatic arthritis do not differ from those of age- and sex-matched controls. C-reactive protein may be elevated but is often normal. Lack of C-reactive protein elevation, however, does not mean that systemic inflammation is absent, but rather indicates that different markers are needed that allow better quantification of systemic inflammation in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Although psoriatic arthritis is not the only disease associated with dactylitis — other culprits are sarcoidosis, septic arthritis, tuberculosis, and gout — dactylitis is one of the characteristic symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. Dactylitis is seen in as many as 35% of patients with psoriatic disease. Dactylitis clinically presents — as in this patient — with sausage-like swelling of the digits. It is included in the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) as one of the hallmarks of psoriatic arthritis.

Dactylitis has been thought to be a result of the concomitant swelling and inflammation of the flexor tendon sheaths of the metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal, or interphalangeal joints. Flexor tenosynovitis can be detected by examination with MRI and ultrasound. Dactylitis is associated with radiologically evident erosive damage to the joints.

Patients with psoriatic arthritis are typically seronegative for rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody; antinuclear antibody titers in persons with psoriatic arthritis do not differ from those of age- and sex-matched controls. C-reactive protein may be elevated but is often normal. Lack of C-reactive protein elevation, however, does not mean that systemic inflammation is absent, but rather indicates that different markers are needed that allow better quantification of systemic inflammation in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 35-year-old man presents with painful swelling of his right index and ring fingers as well as the fourth toe on his right foot, which has persisted for 5 days. He cannot perform his daily activities owing to severe pain in the affected fingers and toes. His medical history is unremarkable. His paternal uncle had psoriasis, which was successfully treated with adalimumab.

Physical assessment reveals tender, fusiform, swollen soft tissues in the affected fingertips, the fourth toe, and swollen palms. Nails are pitted. Hand radiography reveals mild edema of the soft tissue of the index and ring fingers but no significant joint abnormalities. Enthesitis is not present. Laboratory tests reveal a negative human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) test, negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and normal C-reactive protein.

Dactylitis was diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms, radiographic results, and laboratory findings.

Intermittent joint aches

Fundamental changes in the initial pharmacologic approach to psoriatic arthritis were made in the 2018 American College Rheumatology/National Psoriasis (ACR/NPF) guidelines for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Previously, methotrexate had been widely used as the first-line agent. The 2018 guidelines recommend a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor over methotrexate and other oral small molecules (leflunomide, cyclosporine, and apremilast).

Herein is a broad summary of the guidelines:

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over oral small molecule; may consider oral small molecule with mild psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis, patient preference, and/or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitor; may consider IL-17 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with oral small molecule over IL-17 inhibitor; may consider IL-17 inhibitor with severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis

· Treat with oral small molecule over IL-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, or concomitant inflammatory bowel disease

· Treat with methotrexate over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; may consider nonsteroidals for mild psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis

· Treat with IL-17 inhibitor over IL-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor in a patient with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease

Note that these recommendations are based on conditional evidence (ie, low to very low quality). In fact, in the entire guideline document, only 6% of the recommendations are strong, whereas 96% are conditional. This emphasizes the importance of evaluating each patient individually and engaging in a discussion to choose optimal therapy.

Another set of guidelines, from the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), was last updated in 2015. Since then, many of the agents above have been introduced. Updated GRAPPA guidelines are expected to be released later this year.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Fundamental changes in the initial pharmacologic approach to psoriatic arthritis were made in the 2018 American College Rheumatology/National Psoriasis (ACR/NPF) guidelines for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Previously, methotrexate had been widely used as the first-line agent. The 2018 guidelines recommend a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor over methotrexate and other oral small molecules (leflunomide, cyclosporine, and apremilast).

Herein is a broad summary of the guidelines:

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over oral small molecule; may consider oral small molecule with mild psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis, patient preference, and/or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitor; may consider IL-17 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with oral small molecule over IL-17 inhibitor; may consider IL-17 inhibitor with severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis

· Treat with oral small molecule over IL-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, or concomitant inflammatory bowel disease

· Treat with methotrexate over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; may consider nonsteroidals for mild psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis

· Treat with IL-17 inhibitor over IL-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor in a patient with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease

Note that these recommendations are based on conditional evidence (ie, low to very low quality). In fact, in the entire guideline document, only 6% of the recommendations are strong, whereas 96% are conditional. This emphasizes the importance of evaluating each patient individually and engaging in a discussion to choose optimal therapy.

Another set of guidelines, from the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), was last updated in 2015. Since then, many of the agents above have been introduced. Updated GRAPPA guidelines are expected to be released later this year.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Fundamental changes in the initial pharmacologic approach to psoriatic arthritis were made in the 2018 American College Rheumatology/National Psoriasis (ACR/NPF) guidelines for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Previously, methotrexate had been widely used as the first-line agent. The 2018 guidelines recommend a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor over methotrexate and other oral small molecules (leflunomide, cyclosporine, and apremilast).

Herein is a broad summary of the guidelines:

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over oral small molecule; may consider oral small molecule with mild psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis, patient preference, and/or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over interleukin (IL)-17 inhibitor; may consider IL-17 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with TNF inhibitor over interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or contraindication to TNF inhibitor

· Treat with oral small molecule over IL-17 inhibitor; may consider IL-17 inhibitor with severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis

· Treat with oral small molecule over IL-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor with severe psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, or concomitant inflammatory bowel disease

· Treat with methotrexate over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; may consider nonsteroidals for mild psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis

· Treat with IL-17 inhibitor over IL-12/23 inhibitor; may consider IL-12/23 inhibitor in a patient with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease

Note that these recommendations are based on conditional evidence (ie, low to very low quality). In fact, in the entire guideline document, only 6% of the recommendations are strong, whereas 96% are conditional. This emphasizes the importance of evaluating each patient individually and engaging in a discussion to choose optimal therapy.

Another set of guidelines, from the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), was last updated in 2015. Since then, many of the agents above have been introduced. Updated GRAPPA guidelines are expected to be released later this year.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 56-year-old man presents because of intermittent joint aches and difficulty picking up his grandchild and cleaning his home. He has a 6-year history of scalp psoriasis that he has controlled with a salicylic acid shampoo. On physical examination, he has tenderness over both elbows and in his metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints on both hands. Swollen joints are noted in the proximal and distal joints of the right hand. His fingernails show uniform pitting.

Neurologic examination shows no sensory deficits or hyperesthesia. Motor examination is unremarkable, and chest and abdominal findings are unremarkable. Blood pressure is 138/90 mm Hg. Radiographic imaging shows asymmetric erosive changes with very small areas of bony proliferation in the PIP joints.There is asymmetric narrowing of the joint space in the interphalangeal joints. Laboratory findings reveal an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 35 mm/h, negative rheumatoid factor, negative antinuclear antibody, and C-reactive protein of 7 mg/dL.

These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. This patient has severe psoriatic arthritis based on radiographic evidence of erosive disease.

Pulsating unilateral headache and nausea

The patient is probably experiencing migraine without aura. Migraines are a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral. These attacks are associated with symptoms related to the central nervous system. Approximately 15% of patients with migraine experience aura (temporary visual, sensory, speech, or other motor disturbances). More research is needed to determine whether migraine with and without aura are potentially different diagnostic entities.

Classic migraine is a clinical diagnosis. When patients experience migraine symptoms routinely, however, it is important to consider whether these signs and symptoms can be accounted for by another diagnosis. Neuroimaging and, less commonly, lumbar puncture may be indicated in some presentations; red flags that call for additional workup are captured in the acronym SNOOP: systemic symptoms, neurologic symptoms, onset is acute, older patients, and previous history. In addition, classic migraine should be distinguished from common headaches as well as rare subtypes of migraine. For instance, hemiplegic migraine typically presents with temporary unilateral hemiparesis, sometimes accompanied by speech disturbance, and may be inherited (familial hemiplegic migraine). Basilar migraine is another rare subtype of migraine that manifests with signs of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Attacks of chronic paroxysmal hemicrania are unilateral (just as migraines can be in about half of all cases); they are marked by their high intensity but short duration, and are accompanied by same-side facial autonomic symptoms (eg, tearing, congestion). Such patients' history and presentation do not fulfill criteria put forth by the American Headache Society (AHS) for chronic migraine, which specify having headaches 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, and in which on at least 8 days per month those attacks are consistent with migraine or are relieved by a triptan or ergot derivative.

Migraine management must be personalized for each patient and is often associated with a marked trial-and-error period. Migraine without aura and migraine with aura are treated via similar approaches. AHS guidelines include several medications that may be effective in mitigating migraines, including both migraine-specific agents (ergotamine, ergotamine derivatives, and lasmiditan), and nonspecific agents (NSAIDs, combination analgesics, intravenous magnesium, isometheptene-containing compounds, and antiemetics). Triptans represent first-line acute treatment for migraine, but the FDA has approved five acute migraine treatments in total: celecoxib, lasmiditan, remote electrical neuromodulation (REN), rimegepant, and ubrogepant. For moderate or severe attacks, migraine-specific agents are recommended: beyond triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Patients should limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who do not find relief within these parameters are candidates for preventive migraine treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is probably experiencing migraine without aura. Migraines are a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral. These attacks are associated with symptoms related to the central nervous system. Approximately 15% of patients with migraine experience aura (temporary visual, sensory, speech, or other motor disturbances). More research is needed to determine whether migraine with and without aura are potentially different diagnostic entities.

Classic migraine is a clinical diagnosis. When patients experience migraine symptoms routinely, however, it is important to consider whether these signs and symptoms can be accounted for by another diagnosis. Neuroimaging and, less commonly, lumbar puncture may be indicated in some presentations; red flags that call for additional workup are captured in the acronym SNOOP: systemic symptoms, neurologic symptoms, onset is acute, older patients, and previous history. In addition, classic migraine should be distinguished from common headaches as well as rare subtypes of migraine. For instance, hemiplegic migraine typically presents with temporary unilateral hemiparesis, sometimes accompanied by speech disturbance, and may be inherited (familial hemiplegic migraine). Basilar migraine is another rare subtype of migraine that manifests with signs of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Attacks of chronic paroxysmal hemicrania are unilateral (just as migraines can be in about half of all cases); they are marked by their high intensity but short duration, and are accompanied by same-side facial autonomic symptoms (eg, tearing, congestion). Such patients' history and presentation do not fulfill criteria put forth by the American Headache Society (AHS) for chronic migraine, which specify having headaches 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, and in which on at least 8 days per month those attacks are consistent with migraine or are relieved by a triptan or ergot derivative.

Migraine management must be personalized for each patient and is often associated with a marked trial-and-error period. Migraine without aura and migraine with aura are treated via similar approaches. AHS guidelines include several medications that may be effective in mitigating migraines, including both migraine-specific agents (ergotamine, ergotamine derivatives, and lasmiditan), and nonspecific agents (NSAIDs, combination analgesics, intravenous magnesium, isometheptene-containing compounds, and antiemetics). Triptans represent first-line acute treatment for migraine, but the FDA has approved five acute migraine treatments in total: celecoxib, lasmiditan, remote electrical neuromodulation (REN), rimegepant, and ubrogepant. For moderate or severe attacks, migraine-specific agents are recommended: beyond triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Patients should limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who do not find relief within these parameters are candidates for preventive migraine treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The patient is probably experiencing migraine without aura. Migraines are a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral. These attacks are associated with symptoms related to the central nervous system. Approximately 15% of patients with migraine experience aura (temporary visual, sensory, speech, or other motor disturbances). More research is needed to determine whether migraine with and without aura are potentially different diagnostic entities.

Classic migraine is a clinical diagnosis. When patients experience migraine symptoms routinely, however, it is important to consider whether these signs and symptoms can be accounted for by another diagnosis. Neuroimaging and, less commonly, lumbar puncture may be indicated in some presentations; red flags that call for additional workup are captured in the acronym SNOOP: systemic symptoms, neurologic symptoms, onset is acute, older patients, and previous history. In addition, classic migraine should be distinguished from common headaches as well as rare subtypes of migraine. For instance, hemiplegic migraine typically presents with temporary unilateral hemiparesis, sometimes accompanied by speech disturbance, and may be inherited (familial hemiplegic migraine). Basilar migraine is another rare subtype of migraine that manifests with signs of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Attacks of chronic paroxysmal hemicrania are unilateral (just as migraines can be in about half of all cases); they are marked by their high intensity but short duration, and are accompanied by same-side facial autonomic symptoms (eg, tearing, congestion). Such patients' history and presentation do not fulfill criteria put forth by the American Headache Society (AHS) for chronic migraine, which specify having headaches 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, and in which on at least 8 days per month those attacks are consistent with migraine or are relieved by a triptan or ergot derivative.

Migraine management must be personalized for each patient and is often associated with a marked trial-and-error period. Migraine without aura and migraine with aura are treated via similar approaches. AHS guidelines include several medications that may be effective in mitigating migraines, including both migraine-specific agents (ergotamine, ergotamine derivatives, and lasmiditan), and nonspecific agents (NSAIDs, combination analgesics, intravenous magnesium, isometheptene-containing compounds, and antiemetics). Triptans represent first-line acute treatment for migraine, but the FDA has approved five acute migraine treatments in total: celecoxib, lasmiditan, remote electrical neuromodulation (REN), rimegepant, and ubrogepant. For moderate or severe attacks, migraine-specific agents are recommended: beyond triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Patients should limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who do not find relief within these parameters are candidates for preventive migraine treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

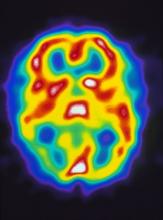

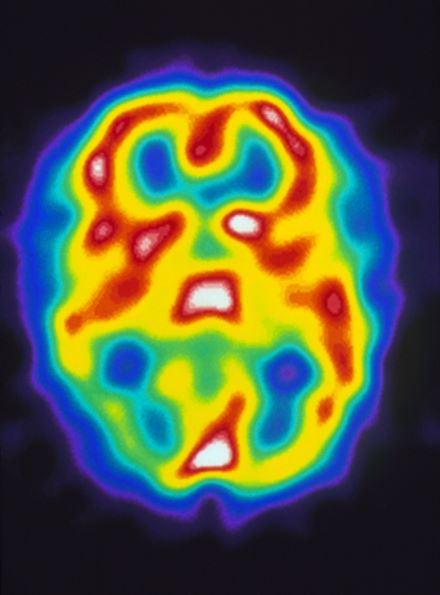

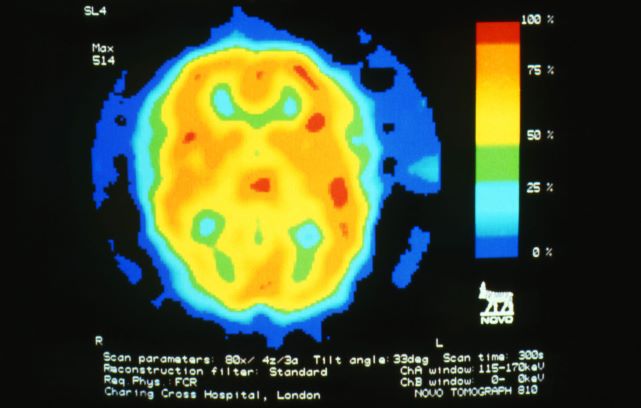

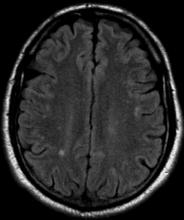

A 22-year-old woman presents with a pulsating unilateral headache (right side) and is very nauseated. The patient reports that since childhood, she has been prone to headaches, with no other significant medical history. Over the past year or so, the headaches have been occurring about once or twice a month, have taken on a throbbing quality, and usually last for several days without relief from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). While taking part in a clinical trial, the patient undergoes a single photon emission CT scan which shows reduced blood flow (lower left).

Recent onset of polyuria and polydipsia

The patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of T2D.

The prevalence of T2D is increasing dramatically in children and adolescents. Like adult-onset T2D, obesity, family history, and sedentary lifestyle are major predisposing risk factors for T2D in children and adolescents. Significantly, the onset of diabetes at a younger age is associated with longer disease exposure and increased risk for chronic complications. Moreover, T2D in adolescents manifests as a severe progressive phenotype that often presents with complications, poor treatment response, and rapid progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Studies have shown that the risk for complications is greater in youth-onset T2D than it is in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and adult-onset T2D.

T2D has a variable presentation in children and adolescents. Approximately one third of patients are diagnosed without having typical diabetes signs or symptoms. In most cases, these patients are in their mid-adolescence are obese and were screened because of one or more positive risk factors or because glycosuria was detected on a random urine test. These patients typically have one or more of the typical characteristics of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Polyuria and polydipsia are seen in approximately 67% of youth with T2D at presentation. Recent weight loss may be present, but it is usually less severe in patients with T2D compared with T1D. Additionally, frequent fungal skin infections or severe vulvovaginitis because of Candida in adolescent girls can be the presenting complaint.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is present in less than 1 in 10 adolescents diagnosed with T2D. Most of these patients belong to ethnic minority groups, report polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, and lethargy, and require hospital admission, rehydration, and insulin replacement therapy. Patients with symptoms such as vomiting can decline rapidly and need urgent evaluation and management.

Certain adolescent patients with obesity who present with diabetic ketoacidosis and are diagnosed with T2D at presentation can also have T1D and will require lifelong insulin treatment. Therefore, following a diagnosis of diabetes in an adolescent, it is critical to differentiate T2D from type 1 diabetes, as well as from other more rare diabetes types, to ensure proper long-term management. Given the substantial overlap between T2D and T1D symptoms, a combination of history clues, clinical characteristics, and laboratory studies must be used to reliably make the distinction. Important clues in the patient's history include:

• Age. Patients with T2D typically present after the onset of puberty, at a mean age of 13.5 years. Conversely, nearly one half of patients with T1D present before 10 years of age, regardless of race or ethnicity.

• Family history. Up to 90% of patients with T2D have an affected first- or second-degree relative; the corresponding percentage for patients with T1D is less than 10%.

• Ethnicity. T2D disproportionately affects youth of ethnic and racial minorities. Compared with White individuals, youth belonging to minority groups such as Native American, African American, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander have a much higher risk of developing T2D.

• Body weight. Most adolescents with T2D have obesity (BMI ≥ 95 percentile for age and sex), whereas those with T1D are usually of normal weight and may report a recent history of weight loss.

• Clinical findings. Adolescents with T2D usually present with features of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, such as acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and polycystic ovary syndrome, whereas these findings are rare in youth with T1D. One study showed that up to 90% of youth diagnosed with T2D had acanthosis nigricans, in contrast to only 12% of those diagnosed with T1D.

Additionally, when the diagnosis of T2D is being considered in children and adolescents, a panel of pancreatic autoantibodies should be tested to exclude the possibility of autoimmune T1D. Because T2D is not immunologically mediated, the identification of one or more pancreatic (islet) cell antibodies in a diabetic adolescent with obesity supports the diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes. Antibodies that are usually measured include islet cell antibodies (against cytoplasmic proteins in the beta cell), anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, and tyrosine phosphatase insulinoma-associated antigen 2, as well as anti-insulin antibodies if insulin replacement therapy has not been used for more than 2 weeks. In addition, a beta cell–specific autoantibody to zinc transporter 8 is frequently detected in children with T1D and can aid in the differential diagnosis. However, up to one third of children with T2D can have at least one detectable beta-cell autoantibody; therefore, total absence of diabetes autoimmune markers is not required for the diagnosis of T2D in children and adolescents.

When a diagnosis of T2D has been established, treatment should consist of lifestyle management, diabetes self-management education, and pharmacologic therapy. According to the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care, the management of diabetes in children and adolescents cannot simply be drawn from the typical care provided to adults with diabetes. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, developmental considerations, and response to therapy in pediatric populations often vary from adult diabetes, and differences exist in recommended care for children and adolescents with T1D, T2D, and other forms of pediatric diabetes.

Because the diabetes type is often uncertain in the first few weeks of treatment, initial therapy should address the hyperglycemia and associated metabolic derangements regardless of the ultimate diabetes type; therapy should then be adjusted once metabolic compensation has been established and subsequent information, such as islet autoantibody results, becomes available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

The patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of T2D.

The prevalence of T2D is increasing dramatically in children and adolescents. Like adult-onset T2D, obesity, family history, and sedentary lifestyle are major predisposing risk factors for T2D in children and adolescents. Significantly, the onset of diabetes at a younger age is associated with longer disease exposure and increased risk for chronic complications. Moreover, T2D in adolescents manifests as a severe progressive phenotype that often presents with complications, poor treatment response, and rapid progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Studies have shown that the risk for complications is greater in youth-onset T2D than it is in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and adult-onset T2D.

T2D has a variable presentation in children and adolescents. Approximately one third of patients are diagnosed without having typical diabetes signs or symptoms. In most cases, these patients are in their mid-adolescence are obese and were screened because of one or more positive risk factors or because glycosuria was detected on a random urine test. These patients typically have one or more of the typical characteristics of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Polyuria and polydipsia are seen in approximately 67% of youth with T2D at presentation. Recent weight loss may be present, but it is usually less severe in patients with T2D compared with T1D. Additionally, frequent fungal skin infections or severe vulvovaginitis because of Candida in adolescent girls can be the presenting complaint.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is present in less than 1 in 10 adolescents diagnosed with T2D. Most of these patients belong to ethnic minority groups, report polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, and lethargy, and require hospital admission, rehydration, and insulin replacement therapy. Patients with symptoms such as vomiting can decline rapidly and need urgent evaluation and management.

Certain adolescent patients with obesity who present with diabetic ketoacidosis and are diagnosed with T2D at presentation can also have T1D and will require lifelong insulin treatment. Therefore, following a diagnosis of diabetes in an adolescent, it is critical to differentiate T2D from type 1 diabetes, as well as from other more rare diabetes types, to ensure proper long-term management. Given the substantial overlap between T2D and T1D symptoms, a combination of history clues, clinical characteristics, and laboratory studies must be used to reliably make the distinction. Important clues in the patient's history include:

• Age. Patients with T2D typically present after the onset of puberty, at a mean age of 13.5 years. Conversely, nearly one half of patients with T1D present before 10 years of age, regardless of race or ethnicity.

• Family history. Up to 90% of patients with T2D have an affected first- or second-degree relative; the corresponding percentage for patients with T1D is less than 10%.

• Ethnicity. T2D disproportionately affects youth of ethnic and racial minorities. Compared with White individuals, youth belonging to minority groups such as Native American, African American, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander have a much higher risk of developing T2D.

• Body weight. Most adolescents with T2D have obesity (BMI ≥ 95 percentile for age and sex), whereas those with T1D are usually of normal weight and may report a recent history of weight loss.

• Clinical findings. Adolescents with T2D usually present with features of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, such as acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and polycystic ovary syndrome, whereas these findings are rare in youth with T1D. One study showed that up to 90% of youth diagnosed with T2D had acanthosis nigricans, in contrast to only 12% of those diagnosed with T1D.

Additionally, when the diagnosis of T2D is being considered in children and adolescents, a panel of pancreatic autoantibodies should be tested to exclude the possibility of autoimmune T1D. Because T2D is not immunologically mediated, the identification of one or more pancreatic (islet) cell antibodies in a diabetic adolescent with obesity supports the diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes. Antibodies that are usually measured include islet cell antibodies (against cytoplasmic proteins in the beta cell), anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, and tyrosine phosphatase insulinoma-associated antigen 2, as well as anti-insulin antibodies if insulin replacement therapy has not been used for more than 2 weeks. In addition, a beta cell–specific autoantibody to zinc transporter 8 is frequently detected in children with T1D and can aid in the differential diagnosis. However, up to one third of children with T2D can have at least one detectable beta-cell autoantibody; therefore, total absence of diabetes autoimmune markers is not required for the diagnosis of T2D in children and adolescents.

When a diagnosis of T2D has been established, treatment should consist of lifestyle management, diabetes self-management education, and pharmacologic therapy. According to the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care, the management of diabetes in children and adolescents cannot simply be drawn from the typical care provided to adults with diabetes. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, developmental considerations, and response to therapy in pediatric populations often vary from adult diabetes, and differences exist in recommended care for children and adolescents with T1D, T2D, and other forms of pediatric diabetes.

Because the diabetes type is often uncertain in the first few weeks of treatment, initial therapy should address the hyperglycemia and associated metabolic derangements regardless of the ultimate diabetes type; therapy should then be adjusted once metabolic compensation has been established and subsequent information, such as islet autoantibody results, becomes available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

The patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of T2D.

The prevalence of T2D is increasing dramatically in children and adolescents. Like adult-onset T2D, obesity, family history, and sedentary lifestyle are major predisposing risk factors for T2D in children and adolescents. Significantly, the onset of diabetes at a younger age is associated with longer disease exposure and increased risk for chronic complications. Moreover, T2D in adolescents manifests as a severe progressive phenotype that often presents with complications, poor treatment response, and rapid progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Studies have shown that the risk for complications is greater in youth-onset T2D than it is in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and adult-onset T2D.

T2D has a variable presentation in children and adolescents. Approximately one third of patients are diagnosed without having typical diabetes signs or symptoms. In most cases, these patients are in their mid-adolescence are obese and were screened because of one or more positive risk factors or because glycosuria was detected on a random urine test. These patients typically have one or more of the typical characteristics of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Polyuria and polydipsia are seen in approximately 67% of youth with T2D at presentation. Recent weight loss may be present, but it is usually less severe in patients with T2D compared with T1D. Additionally, frequent fungal skin infections or severe vulvovaginitis because of Candida in adolescent girls can be the presenting complaint.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is present in less than 1 in 10 adolescents diagnosed with T2D. Most of these patients belong to ethnic minority groups, report polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, and lethargy, and require hospital admission, rehydration, and insulin replacement therapy. Patients with symptoms such as vomiting can decline rapidly and need urgent evaluation and management.

Certain adolescent patients with obesity who present with diabetic ketoacidosis and are diagnosed with T2D at presentation can also have T1D and will require lifelong insulin treatment. Therefore, following a diagnosis of diabetes in an adolescent, it is critical to differentiate T2D from type 1 diabetes, as well as from other more rare diabetes types, to ensure proper long-term management. Given the substantial overlap between T2D and T1D symptoms, a combination of history clues, clinical characteristics, and laboratory studies must be used to reliably make the distinction. Important clues in the patient's history include:

• Age. Patients with T2D typically present after the onset of puberty, at a mean age of 13.5 years. Conversely, nearly one half of patients with T1D present before 10 years of age, regardless of race or ethnicity.

• Family history. Up to 90% of patients with T2D have an affected first- or second-degree relative; the corresponding percentage for patients with T1D is less than 10%.

• Ethnicity. T2D disproportionately affects youth of ethnic and racial minorities. Compared with White individuals, youth belonging to minority groups such as Native American, African American, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander have a much higher risk of developing T2D.

• Body weight. Most adolescents with T2D have obesity (BMI ≥ 95 percentile for age and sex), whereas those with T1D are usually of normal weight and may report a recent history of weight loss.

• Clinical findings. Adolescents with T2D usually present with features of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, such as acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and polycystic ovary syndrome, whereas these findings are rare in youth with T1D. One study showed that up to 90% of youth diagnosed with T2D had acanthosis nigricans, in contrast to only 12% of those diagnosed with T1D.

Additionally, when the diagnosis of T2D is being considered in children and adolescents, a panel of pancreatic autoantibodies should be tested to exclude the possibility of autoimmune T1D. Because T2D is not immunologically mediated, the identification of one or more pancreatic (islet) cell antibodies in a diabetic adolescent with obesity supports the diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes. Antibodies that are usually measured include islet cell antibodies (against cytoplasmic proteins in the beta cell), anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, and tyrosine phosphatase insulinoma-associated antigen 2, as well as anti-insulin antibodies if insulin replacement therapy has not been used for more than 2 weeks. In addition, a beta cell–specific autoantibody to zinc transporter 8 is frequently detected in children with T1D and can aid in the differential diagnosis. However, up to one third of children with T2D can have at least one detectable beta-cell autoantibody; therefore, total absence of diabetes autoimmune markers is not required for the diagnosis of T2D in children and adolescents.

When a diagnosis of T2D has been established, treatment should consist of lifestyle management, diabetes self-management education, and pharmacologic therapy. According to the 2022 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care, the management of diabetes in children and adolescents cannot simply be drawn from the typical care provided to adults with diabetes. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, developmental considerations, and response to therapy in pediatric populations often vary from adult diabetes, and differences exist in recommended care for children and adolescents with T1D, T2D, and other forms of pediatric diabetes.

Because the diabetes type is often uncertain in the first few weeks of treatment, initial therapy should address the hyperglycemia and associated metabolic derangements regardless of the ultimate diabetes type; therapy should then be adjusted once metabolic compensation has been established and subsequent information, such as islet autoantibody results, becomes available.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 14-year-old Black girl presents with complaints of increasing fatigue and recent onset of polyuria and polydipsia. According to the patient's chart, she has lost approximately 5 lb since her last examination 8 months ago. Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg, pulse of 79, and temperature of 100.4°F (38°C). Her weight is 165 lb (75 kg, 96th percentile), height is 62 in (157.5 cm, 32nd percentile), and BMI is 30.2 (97th percentile). Acanthosis nigricans is present. The patient is at Tanner stage 3 of sexual development. There is a positive first-degree family history of type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, and obesity, as well as premature cardiac death in an uncle. Laboratory findings include an A1c value of 7.4%, HDL-C 220 mg/dL, LDL-C 144 mg/dL, and serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL.

Symptoms of fatigue and abdominal pain

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

An 18-year-old man presents with increasing fatigue, prolonged diarrhea, and intermittent abdominal pain. The patient is nearly 6 months into his freshman year at the local university, where he resides. He states that his symptoms began approximately 12 weeks earlier. He describes passing an average of eight to 10 watery stools per day, including nocturnal diarrhea, with no noticeable blood or mucus and no rectal urgency. The patient has lost 13 lb since his symptoms began, which he attributes to the diarrhea and to adjusting to dormitory life and institutional meals. He also notes a slight decrease in appetite. His symptoms typically begin within an hour of awakening, after he has had his morning meal. The patient admits to smoking and occasional use of cannabis. He is not taking any medications or over-the-counter products.

Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 120/70 mm Hg, pulse of 74 beats/min, and temperature of 98.4 °F (37 °C). His weight is 139 lb and his height is 5 ft 10 in. Diffuse abdominal tenderness is present; inspection of the perianal region and rectal examination are normal. There is a positive first-degree family history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and inflammatory bowel disease. His paternal grandmother died of colon cancer at 77 years of age and his maternal grandfather died of ischemic stroke at 82 years of age.

Laboratory findings are all within the normal range and stool testing excludes infectious etiologies. Subsequent endoscopic findings include multiple colonic ulcers longitudinally arranged with a cobblestone appearance.

Woman with throbbing unilateral headache

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Migraine is a complex disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of headache, most often unilateral and in some cases associated with photophobia or phonophobia — a constellation known as aura — that usually arises before the head pain but may also occur during or afterward. Migraine is most common in women, and prevalence peaks between the ages of 25 and 55. In 2016, headache was the fifth most common reason for an ED visit and the third most common reason for an ED visit among female patients age 15-64.

Diagnosis of migraine is made on the basis of patient history. Examples of red flags in the differential would be the presence of neurologic symptoms, stiff neck, or fever, or history of head injury or major trauma. Migraine should also be distinguished from other common headaches. Tension-type headaches usually cause mild or moderate bilateral pain, with a deep, steady ache rather than the typical throbbing quality of migraine headache. In cluster headache, the patient experiences attacks of severe or very severe, strictly unilateral pain (orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain), but the cadence of these headaches differs from that of migraines; these attacks last 15-180 minutes and occur from once every other day to eight times a day. Patients with basilar migraine, common among female patients, usually present with symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

The American Headache Society defines migraine as when a patient reports at least five attacks. These episodes must last 4-72 hours and have at least two of these four characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. In addition, during attacks, the patient must experience either nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia. Signs and symptoms cannot be accounted for by another diagnosis.

Treatment of migraines is often associated with a trial-and-error period. For mild to moderate migraines, these agents may be considered: NSAIDs, nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or caffeinated analgesic combinations. For moderate or severe attacks, or even mild to moderate attacks that do not respond well to therapy, migraine-specific agents are recommended: triptans, dihydroergotamine (DHE), small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants), and selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonists (ditans). Menstrual migraines are treated via the same approaches as nonmenstrual migraines.

Many patients, like the one described here, experience severe nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. For these cases, nonoral agents may be considered (these agents are also an option for patients whose headaches do not respond well to traditional oral medication). Patients should be advised to limit medication use to an average of two headache days per week, and those who feel it necessary to exceed this limit should be offered a preventive treatment.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, Instructor, Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital/Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Angeliki Vgontzas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

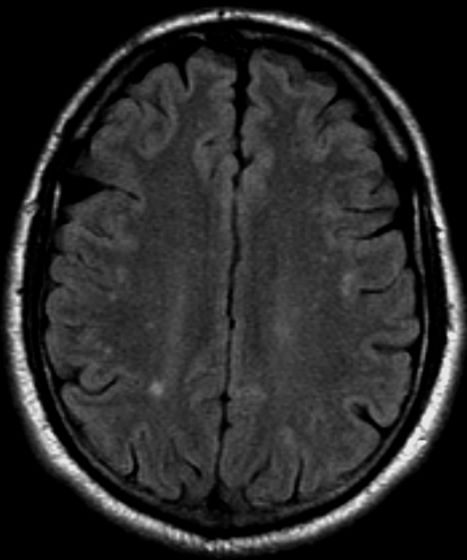

A 28-year-old woman presents with a throbbing unilateral headache (left side) and is very nauseated. She describes a white light in her line of vision. Her headaches are recurring, pulsating, and usually last for about 2 days without relief from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). She has been experiencing these episodes almost every month for the past 8 months and initially attributed them to her menstrual cycle, as she has always experienced moderate to severe headaches during this time. The patient is enrolled in a research trial in which single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging revealed low activity with reduced blood flow. The patient is nonfebrile.

Shortness of breath and abdominal pain

On the basis of the patient's history and clinical presentation, the likely diagnosis is ketosis-prone diabetes (KPD) type 2. KPD is widely thought of as an atypical diabetes syndrome, though some groups consider it to be a common clinical presentation in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) rather than a subtype of disease. The condition is more prevalent in males and among Black and Hispanic populations.

Definitive diagnosis of the type of diabetes can present a clinical challenge during acute presentation. Although the majority of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) episodes occur in patients previously diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, an estimated 34% occur in patients with T2D. For patients who are obese or have a family history of diabetes, there should be a high index of suspicion for new-onset DKA in type 2 diabetes.