User login

Red nodules on legs

Given the patient's diagnosis of stage IV MCL, the presentation of diffuse skin lesions, and the histopathologic and immunophenotyping results of those lesions, this patient is diagnosed with secondary cutaneous MCL. The hematologist-oncologist discusses the findings with the patient and presents potential next steps and treatment options.

MCL is a type of B-cell neoplasm that, with advancements in the understanding of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the past 30 years, has been defined as its own clinicopathologic entity by the Revised European-American Lymphoma and World Health Organization classifications. Up to 10% of all NHLs are MCL. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. Skin manifestations are not as common as other extranodal manifestations. Primary cutaneous MCL occurs in up to 6% of patients with MCL; secondary cutaneous involvement is slightly more common, occurring in 17% of patients with MCL. Secondary cutaneous MCL usually presents in late-stage disease. Men are more likely to present with MCL than are women by a ratio of 3:1. Median age at presentation is 67 years.

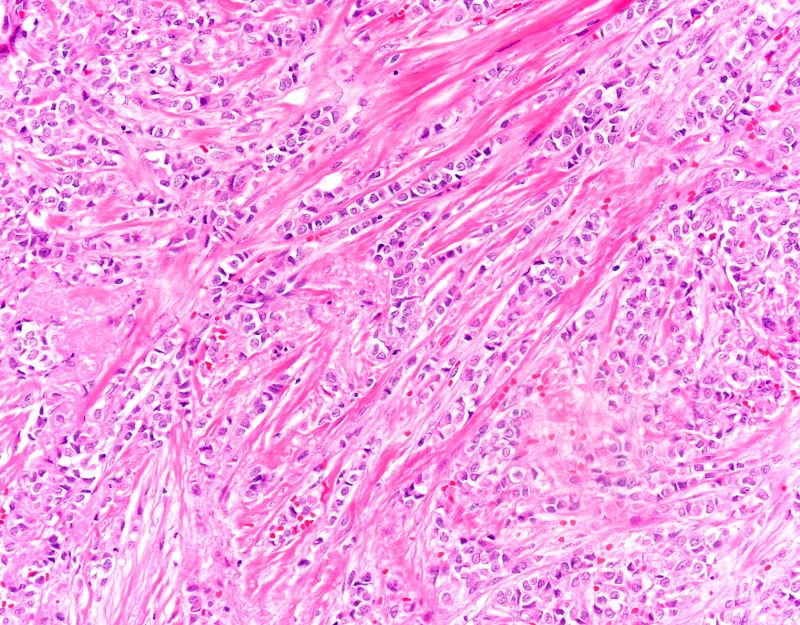

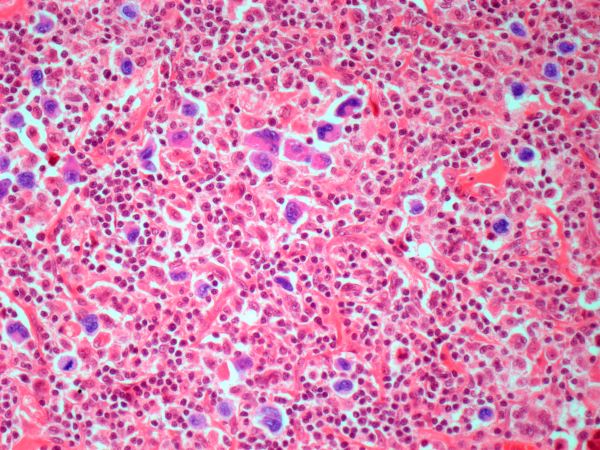

Diagnosing MCL is a multipronged approach. Physical examination may reveal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveals monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin (Ig), IgM, or IgD, that are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen–positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate/biopsy are used more for staging than for diagnosis. Blood studies, including anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with up to 40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and a negative Coombs test also help diagnose MCL. Secondary cutaneous MCL is diagnosed on the basis of an MCL diagnosis along with diffuse infiltration of the skin, with multiple erythematous papules and nodules coalescing to form plaques; skin biopsy and immunohistopathology showing monotonous proliferation of small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with scant cytoplasm; irregular cleaved nuclei with coarse chromatin; and inconspicuous nucleoli as well as a spared papillary dermis.

Pathogenesis of MCL involves disordered lymphoproliferation in a subset of naive pregerminal center cells in primary follicles or in the mantle region of secondary follicles. Most cases are linked with translocation of chromosome 14 and 11, which induces overexpression of protein cyclin D1. Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, human herpes virus 6), environmental factors, and primary and secondary immunodeficiency are also associated with the development of NHL.

Patient education should include detailed information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events as well as psychosocial and nutrition counseling.

Chemoimmunotherapy is standard initial treatment for MCL, but relapse is expected. Chemotherapy-free regimens with biologic targets, which were once used in second-line treatment, have increasingly become an important first-line treatment given their efficacy in the relapsed/refractory setting. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is also a second-line treatment option. In patients with MCL and a TP53 mutation, clinical trial participation is encouraged because of poor prognosis.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's diagnosis of stage IV MCL, the presentation of diffuse skin lesions, and the histopathologic and immunophenotyping results of those lesions, this patient is diagnosed with secondary cutaneous MCL. The hematologist-oncologist discusses the findings with the patient and presents potential next steps and treatment options.

MCL is a type of B-cell neoplasm that, with advancements in the understanding of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the past 30 years, has been defined as its own clinicopathologic entity by the Revised European-American Lymphoma and World Health Organization classifications. Up to 10% of all NHLs are MCL. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. Skin manifestations are not as common as other extranodal manifestations. Primary cutaneous MCL occurs in up to 6% of patients with MCL; secondary cutaneous involvement is slightly more common, occurring in 17% of patients with MCL. Secondary cutaneous MCL usually presents in late-stage disease. Men are more likely to present with MCL than are women by a ratio of 3:1. Median age at presentation is 67 years.

Diagnosing MCL is a multipronged approach. Physical examination may reveal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveals monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin (Ig), IgM, or IgD, that are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen–positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate/biopsy are used more for staging than for diagnosis. Blood studies, including anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with up to 40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and a negative Coombs test also help diagnose MCL. Secondary cutaneous MCL is diagnosed on the basis of an MCL diagnosis along with diffuse infiltration of the skin, with multiple erythematous papules and nodules coalescing to form plaques; skin biopsy and immunohistopathology showing monotonous proliferation of small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with scant cytoplasm; irregular cleaved nuclei with coarse chromatin; and inconspicuous nucleoli as well as a spared papillary dermis.

Pathogenesis of MCL involves disordered lymphoproliferation in a subset of naive pregerminal center cells in primary follicles or in the mantle region of secondary follicles. Most cases are linked with translocation of chromosome 14 and 11, which induces overexpression of protein cyclin D1. Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, human herpes virus 6), environmental factors, and primary and secondary immunodeficiency are also associated with the development of NHL.

Patient education should include detailed information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events as well as psychosocial and nutrition counseling.

Chemoimmunotherapy is standard initial treatment for MCL, but relapse is expected. Chemotherapy-free regimens with biologic targets, which were once used in second-line treatment, have increasingly become an important first-line treatment given their efficacy in the relapsed/refractory setting. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is also a second-line treatment option. In patients with MCL and a TP53 mutation, clinical trial participation is encouraged because of poor prognosis.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's diagnosis of stage IV MCL, the presentation of diffuse skin lesions, and the histopathologic and immunophenotyping results of those lesions, this patient is diagnosed with secondary cutaneous MCL. The hematologist-oncologist discusses the findings with the patient and presents potential next steps and treatment options.

MCL is a type of B-cell neoplasm that, with advancements in the understanding of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the past 30 years, has been defined as its own clinicopathologic entity by the Revised European-American Lymphoma and World Health Organization classifications. Up to 10% of all NHLs are MCL. Clinical presentation includes advanced disease with B symptoms (eg, night sweats, fever, weight loss), generalized lymphadenopathy, abdominal distention associated with hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue. Skin manifestations are not as common as other extranodal manifestations. Primary cutaneous MCL occurs in up to 6% of patients with MCL; secondary cutaneous involvement is slightly more common, occurring in 17% of patients with MCL. Secondary cutaneous MCL usually presents in late-stage disease. Men are more likely to present with MCL than are women by a ratio of 3:1. Median age at presentation is 67 years.

Diagnosing MCL is a multipronged approach. Physical examination may reveal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Lymph node biopsy and aspiration with immunophenotyping in MCL reveals monoclonal B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin (Ig), IgM, or IgD, that are characteristically CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen–positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) but lack expression of CD10 and CD23 and overexpress cyclin D1. Bone marrow aspirate/biopsy are used more for staging than for diagnosis. Blood studies, including anemia and cytopenias secondary to bone marrow infiltration (with up to 40% of cases showing lymphocytosis > 4000/μL), abnormal liver function tests, and a negative Coombs test also help diagnose MCL. Secondary cutaneous MCL is diagnosed on the basis of an MCL diagnosis along with diffuse infiltration of the skin, with multiple erythematous papules and nodules coalescing to form plaques; skin biopsy and immunohistopathology showing monotonous proliferation of small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with scant cytoplasm; irregular cleaved nuclei with coarse chromatin; and inconspicuous nucleoli as well as a spared papillary dermis.

Pathogenesis of MCL involves disordered lymphoproliferation in a subset of naive pregerminal center cells in primary follicles or in the mantle region of secondary follicles. Most cases are linked with translocation of chromosome 14 and 11, which induces overexpression of protein cyclin D1. Viral infection (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, human herpes virus 6), environmental factors, and primary and secondary immunodeficiency are also associated with the development of NHL.

Patient education should include detailed information about clinical trials, available treatment options, and associated adverse events as well as psychosocial and nutrition counseling.

Chemoimmunotherapy is standard initial treatment for MCL, but relapse is expected. Chemotherapy-free regimens with biologic targets, which were once used in second-line treatment, have increasingly become an important first-line treatment given their efficacy in the relapsed/refractory setting. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is also a second-line treatment option. In patients with MCL and a TP53 mutation, clinical trial participation is encouraged because of poor prognosis.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 72-year-old man presents to his hematologist-oncologist with red ulcerative nodules on both legs. Six months before, the patient was diagnosed with stage IV mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and began chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). Initial patient reports at diagnosis were abdominal distention, generalized lymphadenopathy, night sweats, and fatigue; he received a referral to hematology-oncology after his complete blood count with differential revealed anemia and cytopenias. Additional blood studies showed lymphocytosis > 4000/μL, elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, abnormal liver function tests, and a negative result on the Coombs test. Ultrasound of the abdomen revealed hepatosplenomegaly and abdominal lymphadenopathy. The hematologist-oncologist ordered a lymph node biopsy and aspiration. Immunophenotyping showed CD5 and CD20 expression but a lack of CD23 and CD10 expression; cyclin D1 was overexpressed. Bone marrow biopsy revealed hypercellular marrow spaces showing infiltration by sheets of atypical lymphoid cells.

Because the patient presents with red ulcerative nodules on both legs, the hematologist-oncologist orders a skin biopsy of the lesions. Histopathologic evaluation shows monotonous proliferation of small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with scant cytoplasm, irregular cleaved nuclei with coarse chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli as well as a spared papillary dermis. Immunophenotyping shows CD5 and CD20 expression but a lack of CD23 and CD10 expression; cyclin D1 is overexpressed.

Pain in upper right abdomen

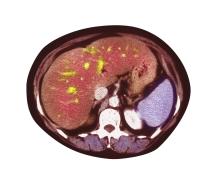

The patient's history, symptomatology, and assessments suggest a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The primary care physician recommends referral to a hepatologist for evaluation and possible liver biopsy.

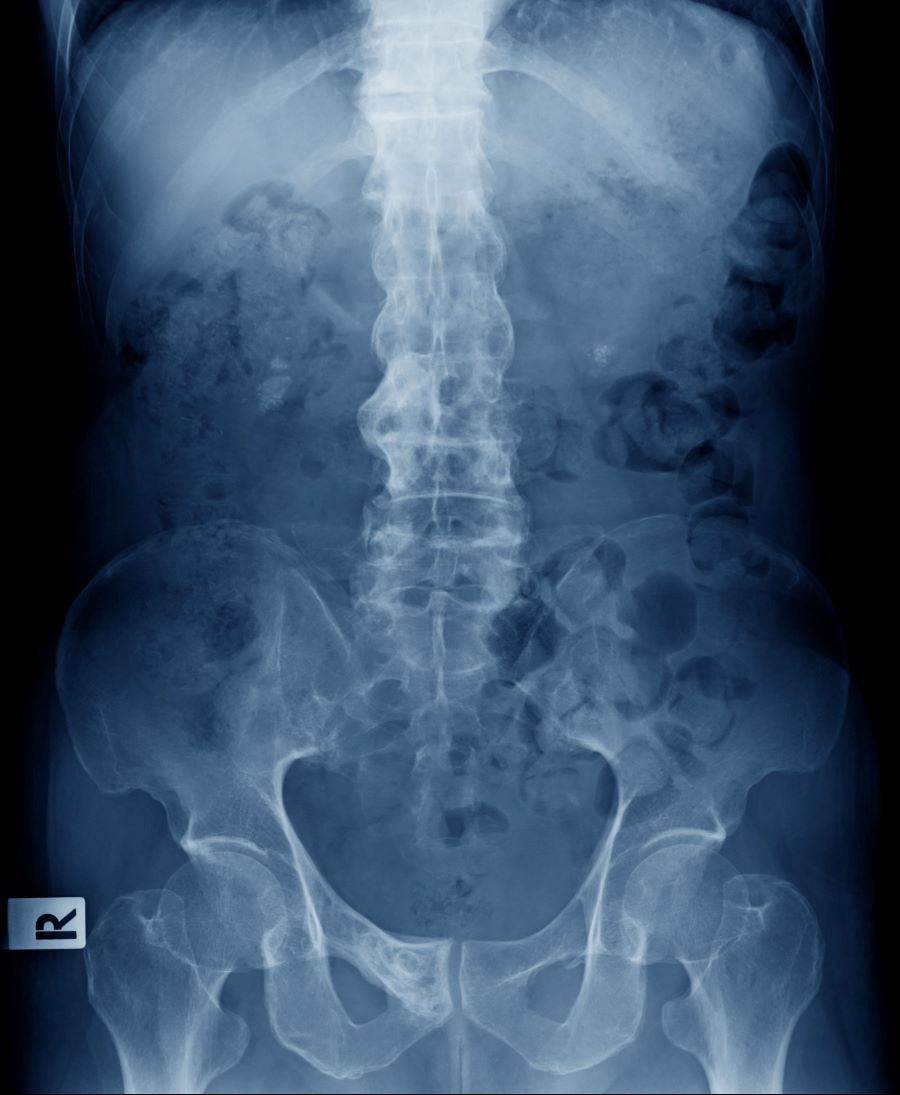

NAFLD involves an accumulation of triglycerides and other fats in the liver (unrelated to alcohol consumption and other liver disease), with the presence of hepatic steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes. NAFLD affects 25% to 35% of the general population, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease. The rate increases among patients with obesity, 80% of whom are affected by NAFLD.

NAFLD should be considered in patients with unexplained elevations in serum aminotransferases (without positive viral markers or autoantibodies and no history of alcohol use) and a high risk for steatohepatitis, including obesity. The standard NAFLD assessment for biopsy specimens is the Brunt system, and disease stage is determined using the NAFLD activity score and the amount of fibrosis present.

A study of the natural history of NAFLD in patients who were followed for 3 years showed that without pharmacologic intervention, one third experienced disease progression, one third remained stable, and one third improved. An independent risk factor for progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was abnormal glucose tolerance testing. In another natural history study, a 10% higher rate of mortality over 10 years was demonstrated among those with NAFLD vs controls, with the top three causes of death being cancer, heart disease, and liver-related disease. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis has been shown to be elevated in Latino and Japanese American populations.

Patients with NAFLD should be seen regularly to assess for disease progression and receive guidance on weight management interventions and exercise. A weight loss of more than 5% has been shown to reduce liver fat and provide cardiometabolic benefits; a weight reduction of more than 10% can help reverse steatohepatitis or liver fibrosis. In addition to weight loss management strategies, physicians should discuss the importance of controlling hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and T2D with their patients and share the importance of avoiding alcohol and other hepatotoxic substances.

According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: "There are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for the treatment of NAFLD; however, some diabetes and anti-obesity medications can be beneficial. Bariatric surgery is also effective for weight loss and reducing liver fat in persons with severe obesity."

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient's history, symptomatology, and assessments suggest a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The primary care physician recommends referral to a hepatologist for evaluation and possible liver biopsy.

NAFLD involves an accumulation of triglycerides and other fats in the liver (unrelated to alcohol consumption and other liver disease), with the presence of hepatic steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes. NAFLD affects 25% to 35% of the general population, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease. The rate increases among patients with obesity, 80% of whom are affected by NAFLD.

NAFLD should be considered in patients with unexplained elevations in serum aminotransferases (without positive viral markers or autoantibodies and no history of alcohol use) and a high risk for steatohepatitis, including obesity. The standard NAFLD assessment for biopsy specimens is the Brunt system, and disease stage is determined using the NAFLD activity score and the amount of fibrosis present.

A study of the natural history of NAFLD in patients who were followed for 3 years showed that without pharmacologic intervention, one third experienced disease progression, one third remained stable, and one third improved. An independent risk factor for progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was abnormal glucose tolerance testing. In another natural history study, a 10% higher rate of mortality over 10 years was demonstrated among those with NAFLD vs controls, with the top three causes of death being cancer, heart disease, and liver-related disease. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis has been shown to be elevated in Latino and Japanese American populations.

Patients with NAFLD should be seen regularly to assess for disease progression and receive guidance on weight management interventions and exercise. A weight loss of more than 5% has been shown to reduce liver fat and provide cardiometabolic benefits; a weight reduction of more than 10% can help reverse steatohepatitis or liver fibrosis. In addition to weight loss management strategies, physicians should discuss the importance of controlling hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and T2D with their patients and share the importance of avoiding alcohol and other hepatotoxic substances.

According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: "There are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for the treatment of NAFLD; however, some diabetes and anti-obesity medications can be beneficial. Bariatric surgery is also effective for weight loss and reducing liver fat in persons with severe obesity."

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient's history, symptomatology, and assessments suggest a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The primary care physician recommends referral to a hepatologist for evaluation and possible liver biopsy.

NAFLD involves an accumulation of triglycerides and other fats in the liver (unrelated to alcohol consumption and other liver disease), with the presence of hepatic steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes. NAFLD affects 25% to 35% of the general population, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease. The rate increases among patients with obesity, 80% of whom are affected by NAFLD.

NAFLD should be considered in patients with unexplained elevations in serum aminotransferases (without positive viral markers or autoantibodies and no history of alcohol use) and a high risk for steatohepatitis, including obesity. The standard NAFLD assessment for biopsy specimens is the Brunt system, and disease stage is determined using the NAFLD activity score and the amount of fibrosis present.

A study of the natural history of NAFLD in patients who were followed for 3 years showed that without pharmacologic intervention, one third experienced disease progression, one third remained stable, and one third improved. An independent risk factor for progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis was abnormal glucose tolerance testing. In another natural history study, a 10% higher rate of mortality over 10 years was demonstrated among those with NAFLD vs controls, with the top three causes of death being cancer, heart disease, and liver-related disease. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis has been shown to be elevated in Latino and Japanese American populations.

Patients with NAFLD should be seen regularly to assess for disease progression and receive guidance on weight management interventions and exercise. A weight loss of more than 5% has been shown to reduce liver fat and provide cardiometabolic benefits; a weight reduction of more than 10% can help reverse steatohepatitis or liver fibrosis. In addition to weight loss management strategies, physicians should discuss the importance of controlling hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and T2D with their patients and share the importance of avoiding alcohol and other hepatotoxic substances.

According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: "There are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for the treatment of NAFLD; however, some diabetes and anti-obesity medications can be beneficial. Bariatric surgery is also effective for weight loss and reducing liver fat in persons with severe obesity."

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 51-year-old Hispanic man presents to his primary care physician with fatigue and pain in the upper right abdomen. Physical exam reveals ascites and splenomegaly. His height is 5 ft 8 in and weight is 274 lb; his BMI is 41.7. For the past 5 years, the patient has seen his physician for routine annual exams, during which time he has consistently met the criteria for World Health Organization Class 3 overweight (BMI ≥ 40) and has taken metformin, with varying degrees of adherence, for type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now, given the patient's symptoms and the potential for uncontrolled diabetes, the physician orders laboratory studies and viral serologies for hepatitis. Results of these assessments exclude viral infection but demonstrate abnormal levels of fasting insulin and glucose, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated transaminase levels that are sixfold above normal levels, with an aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine transaminase ratio < 1:1.

Intensely pruritic rash

The history and findings in this case are consistent with atopic dermatitis (AD).

AD is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects more than 200 million people worldwide, including as many as 30% of children and 10% of adults. Although it is more common in children (and may persist into adulthood), approximately 1 in 4 adults with AD have adult-onset disease.

The etiology of AD is complex and includes both genetic and environmental factors, including a weakened skin barrier, immune dysregulation, and abnormalities of the skin microbiome. AD is a member of the atopic triad (ie, AD, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and asthma), which may commence concurrently or in succession in what is referred to as the "atopic march."

The presentation of adult-onset AD may differ from that seen in children. For example, the most commonly reported body regions affected in adult-onset AD are the hands, eyelids, neck, and flexural surfaces of the upper limbs. In contrast, childhood-onset AD is less specific to body regions other than flexural areas. Xerosis is a prominent feature, and lichenification may be present. Some patients may have a rippled, brown macular ring around the neck, simulating the pigmentations seen in macular amyloid but due instead to postinflammatory melanin deposition. Pruritus is the most common and bothersome symptom associated with AD; patients may also experience anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances.

Diminished quality of life, reduced productivity at work and school, and increased healthcare costs (hospitalizations, emergency visits, outpatient visits, and medications) have all been reported in patients with AD. Triggers for flare-ups vary among individuals; commonly reported triggers include physical or emotional stress, changes in temperature or humidity, sweating, allergens, and irritants.

AD is typically diagnosed clinically given the characteristic distribution of lesions in various age groups (infancy, childhood, and adult). Associated findings such as keratosis pilaris may help to facilitate the diagnosis. No biomarker for the diagnosis of AD has been found and laboratory testing is rarely necessary. However, a swab of infected skin may help to isolate a specific involved organism (eg, Staphylococcus or Streptococcus) and antibiotic sensitivity. Allergy and radioallergosorbent testing are not necessary to make the diagnosis. A swab for viral polymerase chain reaction may be beneficial to help identify superinfection with herpes simplex virus and identify a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum. Testing for serum IgE level can also be helpful for supporting the diagnosis of AD.

The management of AD includes trigger avoidance, daily skin care with application of emollients, anti-inflammatory therapy, and other complementary modalities. For mild or moderate AD, first-line treatment consists of topical anti-inflammatory ointments and creams, including topical corticosteroids, which are available in a broad range of potencies. Other topical medications include topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for patients aged ≥ 2 years), which may be particularly appropriate when there is concern for adverse events secondary to corticosteroid use; topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor (crisaborole ointment for patients aged ≥ 3 months); and topical Janus kinase inhibitor (ruxolitinib cream for patients aged ≥ 12 years).

For patients with moderate to severe AD, or for those who are refractory to topical medications, treatment may include biologic therapy (dupilumab and tralokinumab for patients aged ≥ 6 months and ≥ 18 years, respectively), oral Janus kinase inhibitors (upadacitinib and abrocitinib for patients ages ≥ 12 and ≥ 18 years, respectively), phototherapy (commonly narrow-band ultraviolet light type B treatment), and oral immunomodulators (including methotrexate, mycophenolate, and azathioprine). Combination therapy may be required for the long-term management of more severe AD.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are consistent with atopic dermatitis (AD).

AD is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects more than 200 million people worldwide, including as many as 30% of children and 10% of adults. Although it is more common in children (and may persist into adulthood), approximately 1 in 4 adults with AD have adult-onset disease.

The etiology of AD is complex and includes both genetic and environmental factors, including a weakened skin barrier, immune dysregulation, and abnormalities of the skin microbiome. AD is a member of the atopic triad (ie, AD, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and asthma), which may commence concurrently or in succession in what is referred to as the "atopic march."

The presentation of adult-onset AD may differ from that seen in children. For example, the most commonly reported body regions affected in adult-onset AD are the hands, eyelids, neck, and flexural surfaces of the upper limbs. In contrast, childhood-onset AD is less specific to body regions other than flexural areas. Xerosis is a prominent feature, and lichenification may be present. Some patients may have a rippled, brown macular ring around the neck, simulating the pigmentations seen in macular amyloid but due instead to postinflammatory melanin deposition. Pruritus is the most common and bothersome symptom associated with AD; patients may also experience anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances.

Diminished quality of life, reduced productivity at work and school, and increased healthcare costs (hospitalizations, emergency visits, outpatient visits, and medications) have all been reported in patients with AD. Triggers for flare-ups vary among individuals; commonly reported triggers include physical or emotional stress, changes in temperature or humidity, sweating, allergens, and irritants.

AD is typically diagnosed clinically given the characteristic distribution of lesions in various age groups (infancy, childhood, and adult). Associated findings such as keratosis pilaris may help to facilitate the diagnosis. No biomarker for the diagnosis of AD has been found and laboratory testing is rarely necessary. However, a swab of infected skin may help to isolate a specific involved organism (eg, Staphylococcus or Streptococcus) and antibiotic sensitivity. Allergy and radioallergosorbent testing are not necessary to make the diagnosis. A swab for viral polymerase chain reaction may be beneficial to help identify superinfection with herpes simplex virus and identify a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum. Testing for serum IgE level can also be helpful for supporting the diagnosis of AD.

The management of AD includes trigger avoidance, daily skin care with application of emollients, anti-inflammatory therapy, and other complementary modalities. For mild or moderate AD, first-line treatment consists of topical anti-inflammatory ointments and creams, including topical corticosteroids, which are available in a broad range of potencies. Other topical medications include topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for patients aged ≥ 2 years), which may be particularly appropriate when there is concern for adverse events secondary to corticosteroid use; topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor (crisaborole ointment for patients aged ≥ 3 months); and topical Janus kinase inhibitor (ruxolitinib cream for patients aged ≥ 12 years).

For patients with moderate to severe AD, or for those who are refractory to topical medications, treatment may include biologic therapy (dupilumab and tralokinumab for patients aged ≥ 6 months and ≥ 18 years, respectively), oral Janus kinase inhibitors (upadacitinib and abrocitinib for patients ages ≥ 12 and ≥ 18 years, respectively), phototherapy (commonly narrow-band ultraviolet light type B treatment), and oral immunomodulators (including methotrexate, mycophenolate, and azathioprine). Combination therapy may be required for the long-term management of more severe AD.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are consistent with atopic dermatitis (AD).

AD is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects more than 200 million people worldwide, including as many as 30% of children and 10% of adults. Although it is more common in children (and may persist into adulthood), approximately 1 in 4 adults with AD have adult-onset disease.

The etiology of AD is complex and includes both genetic and environmental factors, including a weakened skin barrier, immune dysregulation, and abnormalities of the skin microbiome. AD is a member of the atopic triad (ie, AD, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and asthma), which may commence concurrently or in succession in what is referred to as the "atopic march."

The presentation of adult-onset AD may differ from that seen in children. For example, the most commonly reported body regions affected in adult-onset AD are the hands, eyelids, neck, and flexural surfaces of the upper limbs. In contrast, childhood-onset AD is less specific to body regions other than flexural areas. Xerosis is a prominent feature, and lichenification may be present. Some patients may have a rippled, brown macular ring around the neck, simulating the pigmentations seen in macular amyloid but due instead to postinflammatory melanin deposition. Pruritus is the most common and bothersome symptom associated with AD; patients may also experience anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances.

Diminished quality of life, reduced productivity at work and school, and increased healthcare costs (hospitalizations, emergency visits, outpatient visits, and medications) have all been reported in patients with AD. Triggers for flare-ups vary among individuals; commonly reported triggers include physical or emotional stress, changes in temperature or humidity, sweating, allergens, and irritants.

AD is typically diagnosed clinically given the characteristic distribution of lesions in various age groups (infancy, childhood, and adult). Associated findings such as keratosis pilaris may help to facilitate the diagnosis. No biomarker for the diagnosis of AD has been found and laboratory testing is rarely necessary. However, a swab of infected skin may help to isolate a specific involved organism (eg, Staphylococcus or Streptococcus) and antibiotic sensitivity. Allergy and radioallergosorbent testing are not necessary to make the diagnosis. A swab for viral polymerase chain reaction may be beneficial to help identify superinfection with herpes simplex virus and identify a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum. Testing for serum IgE level can also be helpful for supporting the diagnosis of AD.

The management of AD includes trigger avoidance, daily skin care with application of emollients, anti-inflammatory therapy, and other complementary modalities. For mild or moderate AD, first-line treatment consists of topical anti-inflammatory ointments and creams, including topical corticosteroids, which are available in a broad range of potencies. Other topical medications include topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for patients aged ≥ 2 years), which may be particularly appropriate when there is concern for adverse events secondary to corticosteroid use; topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor (crisaborole ointment for patients aged ≥ 3 months); and topical Janus kinase inhibitor (ruxolitinib cream for patients aged ≥ 12 years).

For patients with moderate to severe AD, or for those who are refractory to topical medications, treatment may include biologic therapy (dupilumab and tralokinumab for patients aged ≥ 6 months and ≥ 18 years, respectively), oral Janus kinase inhibitors (upadacitinib and abrocitinib for patients ages ≥ 12 and ≥ 18 years, respectively), phototherapy (commonly narrow-band ultraviolet light type B treatment), and oral immunomodulators (including methotrexate, mycophenolate, and azathioprine). Combination therapy may be required for the long-term management of more severe AD.

William D. James, MD, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Disclosure: William D. James, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Elsevier.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 52-year-old woman presents with complaints of an itchy rash on her arms, legs, neck, and eyelids. She reports having flares with a similar eruption on her arms and legs over the past 2 years, but on previous occasions she was able to manage it with topical emollients. Over the past 6 months, however, it has worsened both in intensity and spread. She describes the rash as intensely pruritic, and now that it has become more visible, she reports feeling embarrassed by it at work and during social outings. The itch is also disrupting her sleep. The patient states that she is undergoing an extremely stressful period in her life because of her parents' declining health and a recent separation from her husband.

Approximately 3 months ago, she visited her primary care provider, who diagnosed her with an allergic rash and prescribed a course of an oral glucocorticoid. Initially, she thought the treatment worked, but the rash soon recurred after she finished her treatment.

Physical examination reveals scaly, crusted hyperpigmented lesions involving the arms, flexural areas of the elbows and knees, neck, and eyelids. Lichenification and xerosis are observed. There is no evidence of conjunctivitis or scalp involvement. The turbinates are not inflamed. Complete blood count findings are within normal range. The patient is 5 ft 3 in and weighs 125 lb (BMI 22.1) and is a nonsmoker.

Cough and hemoptysis

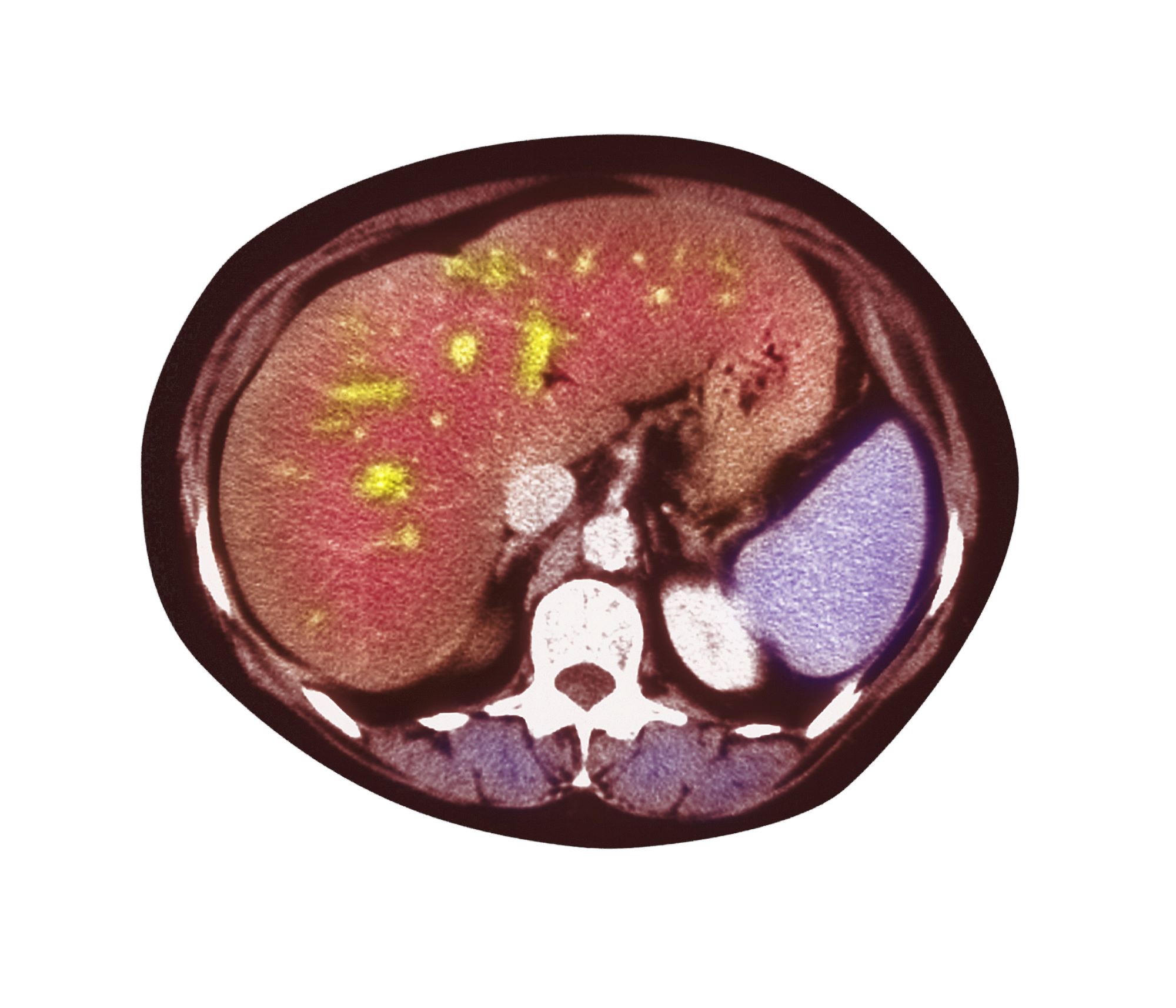

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 74-year-old man presents to the emergency department with reports of cough, hemoptysis, and unintentional weight loss of approximately 8 weeks' duration. The patient has a 35-year history of smoking (35 pack years). The patient's vital signs include temperature of 98.4 °F, BP of 135/80 mm Hg, and pulse oximeter reading of 94%. Physical examination reveals rales over the left side of the chest and decreased breath sounds in bilateral bases of the lungs. The patient appears cachexic. He is 6 ft 2 in and weighs 163 lb.

A chest radiograph reveals a mass in the right lung field. A subsequent CT of the chest reveals multiple pulmonary nodules and extensive mediastinal nodal metastases. Histopathology reveals small, uniform, poorly differentiated necrotic cancers and adenocarcinoma with papillary and acinar features.

Forgetfulness and confusion

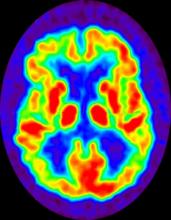

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset familial AD (onset after age 65 years).

AD is a common neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. In 2020, 5.8 million Americans were living with AD. By 2050, this number is projected to increase to 13.9 million people, or almost 3.3% of the US population. Globally, 152 million people are projected to have AD and other dementias by 2050. The worldwide increase in incidence and prevalence of AD is at least partially explained by an aging population and increased life expectancy.

The cause of AD remains unclear, but there is substantial evidence that AD is a highly heritable disorder. Familial AD is characterized by having more than one member in more than one generation with AD. The autosomal-dominant form of AD is linked to mutations in three genes: AAP on chromosome 21, PSEN1 on chromosome 14, and PSEN2 on chromosome 1. APP mutations may cause increased generation and aggregation of beta-amyloid peptide, whereas PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations result in aggregation of beta-amyloid by interfering with the processing of gamma-secretase.

APOE is another genetic marker that increases the risk for AD. Isoform e4 of the APOE gene (located on chromosome 19) has been associated with more sporadic and familial forms of AD that present after age 65 years. Approximately 50% of individuals carrying one APOEe4 develop AD, and 90% of individuals who have two alleles develop AD. Variants in the gene for the sortilin receptor, SORT1, have also been found in familial and sporadic forms of AD.

The cognitive and behavioral impairment associated with AD significantly affects a patient's social and occupational functioning. Insidiously progressive memory loss is a characteristic symptoms seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease advances over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. A slow progression of behavioral changes may also occur in individuals with AD.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are often used to diagnose patients. In addition, biomarker evidence may help to increase the diagnostic certainty. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid-beta for AD.

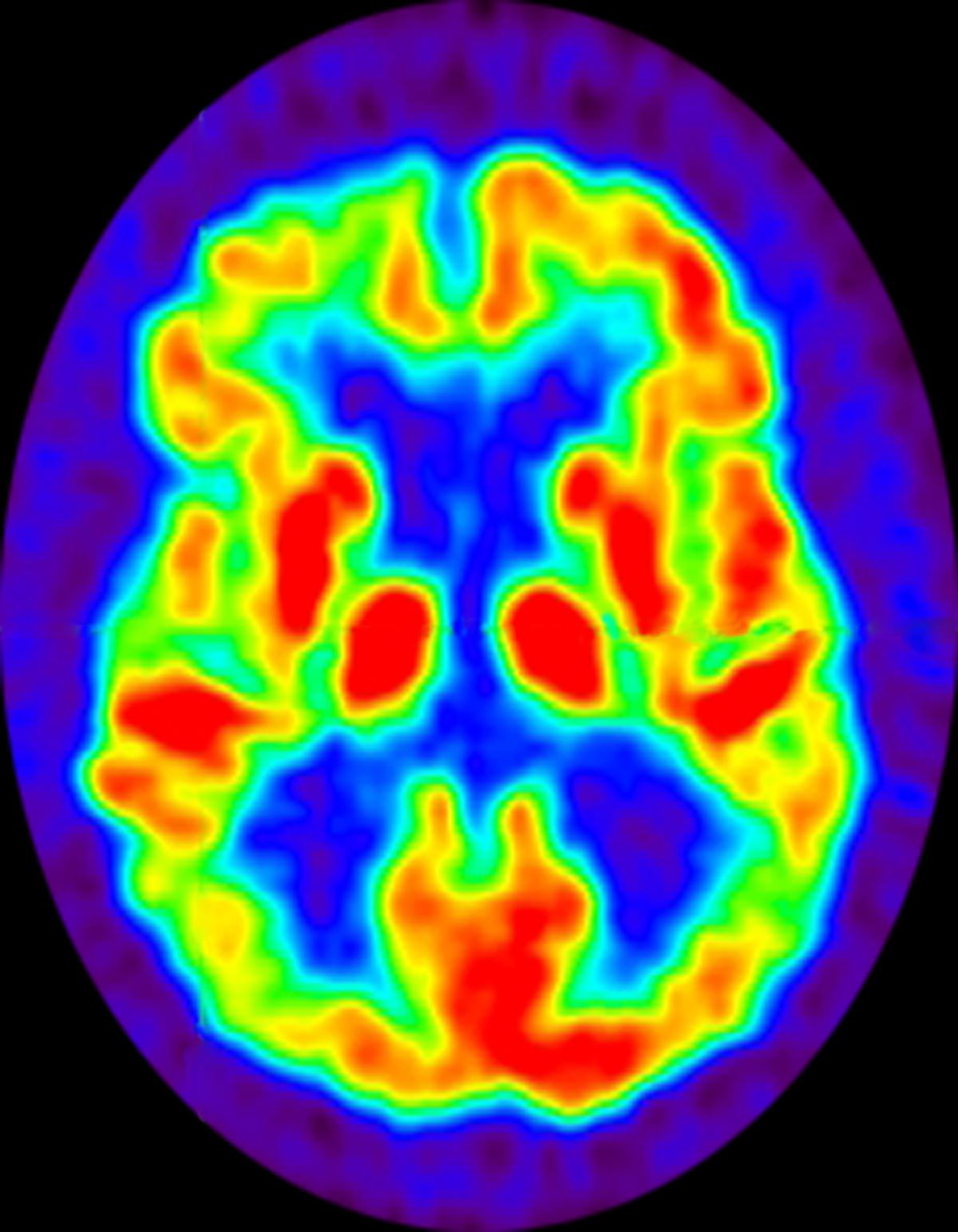

Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD because it allows for accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT can be used when MRI is not available or is contraindicated, such as in a patient with a pacemaker. PET is another noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, which marked a significant achievement to improve AD diagnosis.

At present, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatments for AD. Antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, can be treated with psychotropic agents. Behavioral interventions including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training can also be helpful for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD, often in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise may also play a role in delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset familial AD (onset after age 65 years).

AD is a common neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. In 2020, 5.8 million Americans were living with AD. By 2050, this number is projected to increase to 13.9 million people, or almost 3.3% of the US population. Globally, 152 million people are projected to have AD and other dementias by 2050. The worldwide increase in incidence and prevalence of AD is at least partially explained by an aging population and increased life expectancy.

The cause of AD remains unclear, but there is substantial evidence that AD is a highly heritable disorder. Familial AD is characterized by having more than one member in more than one generation with AD. The autosomal-dominant form of AD is linked to mutations in three genes: AAP on chromosome 21, PSEN1 on chromosome 14, and PSEN2 on chromosome 1. APP mutations may cause increased generation and aggregation of beta-amyloid peptide, whereas PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations result in aggregation of beta-amyloid by interfering with the processing of gamma-secretase.

APOE is another genetic marker that increases the risk for AD. Isoform e4 of the APOE gene (located on chromosome 19) has been associated with more sporadic and familial forms of AD that present after age 65 years. Approximately 50% of individuals carrying one APOEe4 develop AD, and 90% of individuals who have two alleles develop AD. Variants in the gene for the sortilin receptor, SORT1, have also been found in familial and sporadic forms of AD.

The cognitive and behavioral impairment associated with AD significantly affects a patient's social and occupational functioning. Insidiously progressive memory loss is a characteristic symptoms seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease advances over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. A slow progression of behavioral changes may also occur in individuals with AD.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are often used to diagnose patients. In addition, biomarker evidence may help to increase the diagnostic certainty. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid-beta for AD.

Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD because it allows for accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT can be used when MRI is not available or is contraindicated, such as in a patient with a pacemaker. PET is another noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, which marked a significant achievement to improve AD diagnosis.

At present, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatments for AD. Antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, can be treated with psychotropic agents. Behavioral interventions including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training can also be helpful for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD, often in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise may also play a role in delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset familial AD (onset after age 65 years).

AD is a common neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. In 2020, 5.8 million Americans were living with AD. By 2050, this number is projected to increase to 13.9 million people, or almost 3.3% of the US population. Globally, 152 million people are projected to have AD and other dementias by 2050. The worldwide increase in incidence and prevalence of AD is at least partially explained by an aging population and increased life expectancy.

The cause of AD remains unclear, but there is substantial evidence that AD is a highly heritable disorder. Familial AD is characterized by having more than one member in more than one generation with AD. The autosomal-dominant form of AD is linked to mutations in three genes: AAP on chromosome 21, PSEN1 on chromosome 14, and PSEN2 on chromosome 1. APP mutations may cause increased generation and aggregation of beta-amyloid peptide, whereas PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations result in aggregation of beta-amyloid by interfering with the processing of gamma-secretase.

APOE is another genetic marker that increases the risk for AD. Isoform e4 of the APOE gene (located on chromosome 19) has been associated with more sporadic and familial forms of AD that present after age 65 years. Approximately 50% of individuals carrying one APOEe4 develop AD, and 90% of individuals who have two alleles develop AD. Variants in the gene for the sortilin receptor, SORT1, have also been found in familial and sporadic forms of AD.

The cognitive and behavioral impairment associated with AD significantly affects a patient's social and occupational functioning. Insidiously progressive memory loss is a characteristic symptoms seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease advances over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. A slow progression of behavioral changes may also occur in individuals with AD.

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are often used to diagnose patients. In addition, biomarker evidence may help to increase the diagnostic certainty. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid-beta for AD.

Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD because it allows for accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT can be used when MRI is not available or is contraindicated, such as in a patient with a pacemaker. PET is another noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, which marked a significant achievement to improve AD diagnosis.

At present, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatments for AD. Antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid-beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, can be treated with psychotropic agents. Behavioral interventions including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training can also be helpful for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD, often in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders). Regular physical activity and exercise may also play a role in delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 72-year-old woman presents with a 12-month history of short-term memory loss. The patient is accompanied by her husband, who states her symptoms have become increasingly frequent and severe. The patient can no longer drive familiar routes after becoming lost on several occasions. She frequently misplaces items; recently, she placed her husband's car keys in the refrigerator. The patient admits to increasing bouts of forgetfulness and confusion and states that she has been feeling very down. She has not been able to watch her grandchildren over the past few months, which makes her feel sad and old. She also reports trouble sleeping at night due to generalized anxiety.

The patient's past medical history is significant for hypertension and dyslipidemia. There is no history of neurotoxic exposure, head injuries, strokes, or seizures. Her family history is positive for dementia. Her older brother was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease (AD) at age 68 years, and her mother died from AD at age 82 years. Current medications include rosuvastatin 20 mg/d and lisinopril 20 mg/d. The patient's current height and weight are 5 ft 5 in and 163 lb, respectively (BMI is 27.1).

No abnormalities are noted on physical examination; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are within normal ranges. The patient scores 18 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. The patient's clinician orders a brain fluorodeoxyglucose-PET, which reveals areas of decreased glucose metabolism involving the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, inferior parietal lobule, and middle temporal gyrus.

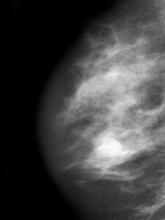

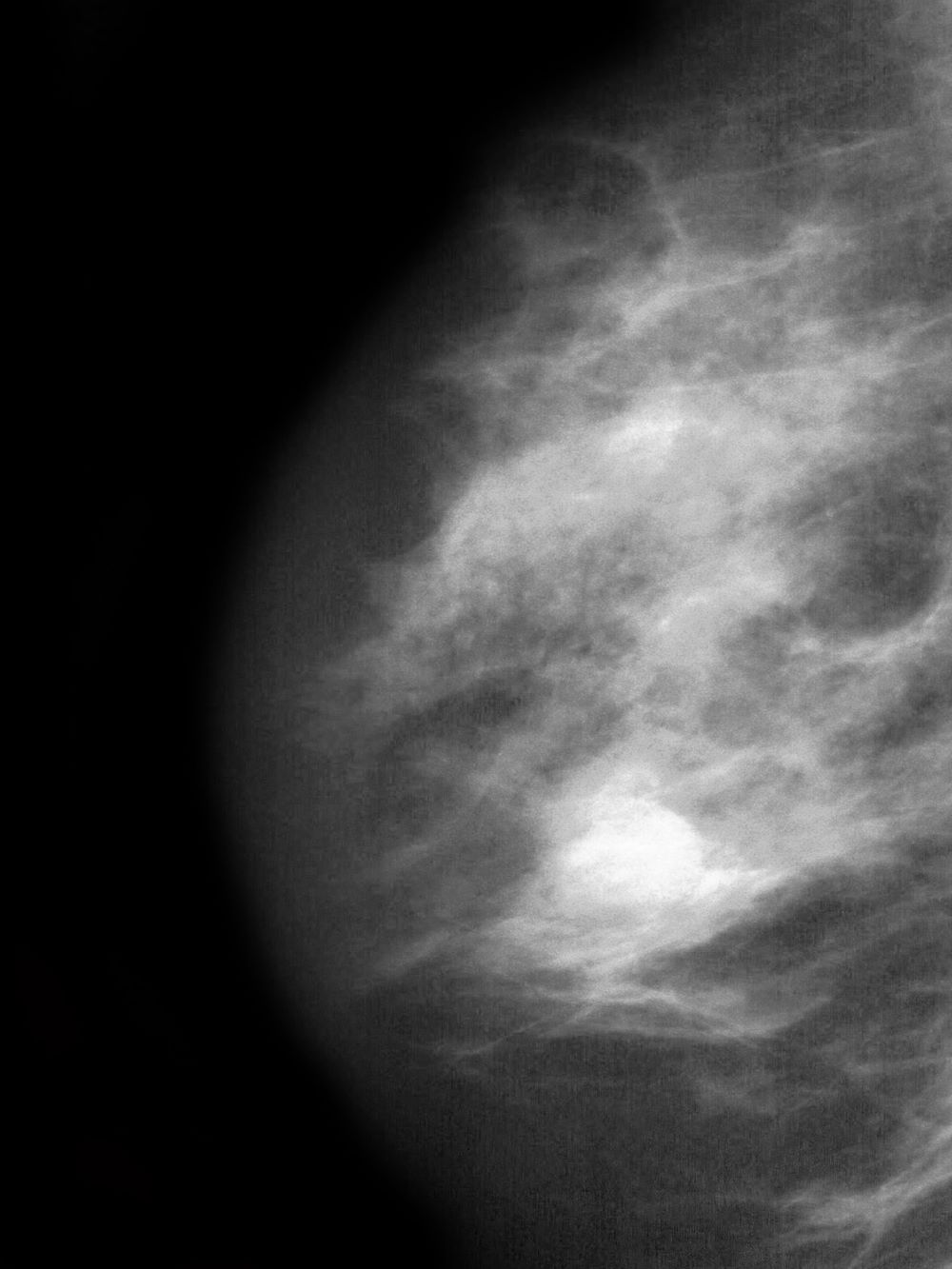

Postmenopausal screening mammogram

The findings in this case are suggestive of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Globally, breast cancer remains the most common life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women. In the United States, approximately 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 deaths were attributed to breast cancer in the same year. Worldwide, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer-related deaths were reported in 2020.

ILC is one of the leading histologic types of invasive carcinoma, second in incidence only to invasive carcinoma of no special type. ILC accounts for 5%-15% of all invasive breast cancers, and its incidence has been steadily increasing — particularly among postmenopausal women — over the past two decades. ILC has distinct molecular and histopathologic features, including the loss of cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, resulting in small, discohesive cells proliferating in single-file strands; positivity for both the estrogen and progesterone receptor; and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negativity.

The diagnosis of ILC can be challenging, as it is difficult to detect both on physical examination and with standard imaging techniques. Patients are often diagnosed with late-stage disease, characterized by large tumors and lymph node involvement. The signs of ILC are often vague, such as skin thickening or dimpling. In addition, measuring the extent of ILC can be challenging, as traditional screening methods (eg, mammography and ultrasonography) have a low sensitivity for detecting ILC compared with other invasive breast tumors. This difficulty is usually ascribed to the diffuse infiltrative growth pattern of ILC. MRI has a greater sensitivity for detecting ILC.

Risk factors for the development of ILC have been identified and include:

• Alcohol consumption

• Use of combined hormone replacement therapy

• Early menarche (menarche before the age of 12 years)

• Late-onset menopause (menopause after the age of 55 years)

• Nulliparity/low parity (defined by World Health Organization as fewer than five pregnancies with gestation periods of ≥ 20 weeks)

• Late age at birth (> 30 years)

• Family history (eg, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome)

• Genetics (eg, CDH1 mutations)

Treatment protocols for ILC align with those used in other breast cancer subtypes and typically involve a multidisciplinary approach comprising surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies. Cancers that are deemed resectable will typically be managed surgically upfront, although some patients may require neoadjuvant therapy to reduce tumor burden and facilitate surgical intervention. Breast-conserving surgery using a wide local excision can frequently be performed; however, in up to 65% of cases, a second surgery will be required (re-excision or mastectomy). Axillary lymph node status is a crucial factor in the prognosis of all breast cancers and affects surgical planning. Sentinel node biopsy is the standard method of assessing the axilla.

Systemic therapy is an integral part of the multidisciplinary approach to treating breast cancer and usually involves the use of chemotherapy. However, because of the unique molecular biology of ILC, treatment response to chemotherapy is often poor, resulting in lower rates of complete pathologic response and higher rates of mastectomy. Conversely, ILC has been shown to respond well to endocrine therapy, making it the optimal treatment choice. Novel therapeutic approaches are under investigation.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of ILC is available from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The findings in this case are suggestive of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Globally, breast cancer remains the most common life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women. In the United States, approximately 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 deaths were attributed to breast cancer in the same year. Worldwide, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer-related deaths were reported in 2020.

ILC is one of the leading histologic types of invasive carcinoma, second in incidence only to invasive carcinoma of no special type. ILC accounts for 5%-15% of all invasive breast cancers, and its incidence has been steadily increasing — particularly among postmenopausal women — over the past two decades. ILC has distinct molecular and histopathologic features, including the loss of cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, resulting in small, discohesive cells proliferating in single-file strands; positivity for both the estrogen and progesterone receptor; and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negativity.

The diagnosis of ILC can be challenging, as it is difficult to detect both on physical examination and with standard imaging techniques. Patients are often diagnosed with late-stage disease, characterized by large tumors and lymph node involvement. The signs of ILC are often vague, such as skin thickening or dimpling. In addition, measuring the extent of ILC can be challenging, as traditional screening methods (eg, mammography and ultrasonography) have a low sensitivity for detecting ILC compared with other invasive breast tumors. This difficulty is usually ascribed to the diffuse infiltrative growth pattern of ILC. MRI has a greater sensitivity for detecting ILC.

Risk factors for the development of ILC have been identified and include:

• Alcohol consumption

• Use of combined hormone replacement therapy

• Early menarche (menarche before the age of 12 years)

• Late-onset menopause (menopause after the age of 55 years)

• Nulliparity/low parity (defined by World Health Organization as fewer than five pregnancies with gestation periods of ≥ 20 weeks)

• Late age at birth (> 30 years)

• Family history (eg, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome)

• Genetics (eg, CDH1 mutations)

Treatment protocols for ILC align with those used in other breast cancer subtypes and typically involve a multidisciplinary approach comprising surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies. Cancers that are deemed resectable will typically be managed surgically upfront, although some patients may require neoadjuvant therapy to reduce tumor burden and facilitate surgical intervention. Breast-conserving surgery using a wide local excision can frequently be performed; however, in up to 65% of cases, a second surgery will be required (re-excision or mastectomy). Axillary lymph node status is a crucial factor in the prognosis of all breast cancers and affects surgical planning. Sentinel node biopsy is the standard method of assessing the axilla.

Systemic therapy is an integral part of the multidisciplinary approach to treating breast cancer and usually involves the use of chemotherapy. However, because of the unique molecular biology of ILC, treatment response to chemotherapy is often poor, resulting in lower rates of complete pathologic response and higher rates of mastectomy. Conversely, ILC has been shown to respond well to endocrine therapy, making it the optimal treatment choice. Novel therapeutic approaches are under investigation.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of ILC is available from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The findings in this case are suggestive of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Globally, breast cancer remains the most common life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women. In the United States, approximately 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 deaths were attributed to breast cancer in the same year. Worldwide, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer-related deaths were reported in 2020.

ILC is one of the leading histologic types of invasive carcinoma, second in incidence only to invasive carcinoma of no special type. ILC accounts for 5%-15% of all invasive breast cancers, and its incidence has been steadily increasing — particularly among postmenopausal women — over the past two decades. ILC has distinct molecular and histopathologic features, including the loss of cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, resulting in small, discohesive cells proliferating in single-file strands; positivity for both the estrogen and progesterone receptor; and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negativity.

The diagnosis of ILC can be challenging, as it is difficult to detect both on physical examination and with standard imaging techniques. Patients are often diagnosed with late-stage disease, characterized by large tumors and lymph node involvement. The signs of ILC are often vague, such as skin thickening or dimpling. In addition, measuring the extent of ILC can be challenging, as traditional screening methods (eg, mammography and ultrasonography) have a low sensitivity for detecting ILC compared with other invasive breast tumors. This difficulty is usually ascribed to the diffuse infiltrative growth pattern of ILC. MRI has a greater sensitivity for detecting ILC.

Risk factors for the development of ILC have been identified and include:

• Alcohol consumption

• Use of combined hormone replacement therapy

• Early menarche (menarche before the age of 12 years)

• Late-onset menopause (menopause after the age of 55 years)

• Nulliparity/low parity (defined by World Health Organization as fewer than five pregnancies with gestation periods of ≥ 20 weeks)

• Late age at birth (> 30 years)

• Family history (eg, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome)

• Genetics (eg, CDH1 mutations)

Treatment protocols for ILC align with those used in other breast cancer subtypes and typically involve a multidisciplinary approach comprising surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies. Cancers that are deemed resectable will typically be managed surgically upfront, although some patients may require neoadjuvant therapy to reduce tumor burden and facilitate surgical intervention. Breast-conserving surgery using a wide local excision can frequently be performed; however, in up to 65% of cases, a second surgery will be required (re-excision or mastectomy). Axillary lymph node status is a crucial factor in the prognosis of all breast cancers and affects surgical planning. Sentinel node biopsy is the standard method of assessing the axilla.