User login

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Neurology

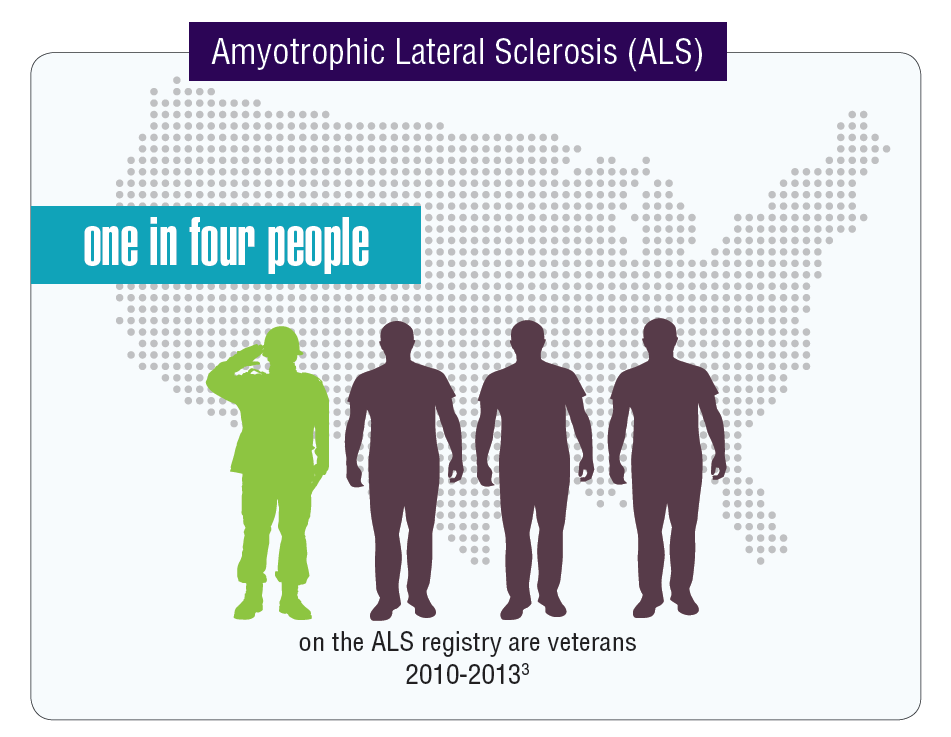

Data seem to indicate that service members and veterans may be at an increased risk of acquiring multiple neurologic diseases or injuries. The very nature of a career in the military often comes with a higher risk of sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) either through combat or physical training, but other serious neurologic disorders seem to affect veterans disproportionally compared with those who did not serve in the Armed Forces.

Click here to continue reading.

Data seem to indicate that service members and veterans may be at an increased risk of acquiring multiple neurologic diseases or injuries. The very nature of a career in the military often comes with a higher risk of sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) either through combat or physical training, but other serious neurologic disorders seem to affect veterans disproportionally compared with those who did not serve in the Armed Forces.

Click here to continue reading.

Data seem to indicate that service members and veterans may be at an increased risk of acquiring multiple neurologic diseases or injuries. The very nature of a career in the military often comes with a higher risk of sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) either through combat or physical training, but other serious neurologic disorders seem to affect veterans disproportionally compared with those who did not serve in the Armed Forces.

Click here to continue reading.

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Dermatology

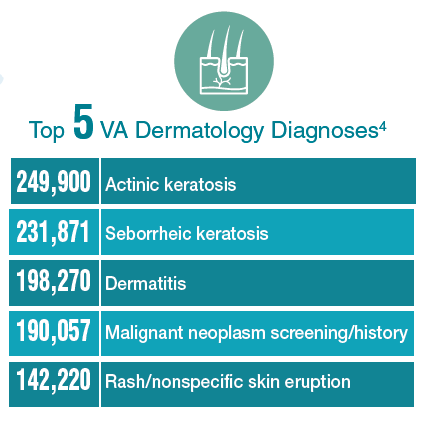

There is significant variation among the civilian, active-duty, and veteran populations in regard to dermatologic conditions. Civilians most frequently visit a specialist with complaints of eczema, dermatitis, acne, and other benign conditions. Among active-duty service members, infections and allergic bite reactions are the most common reasons for a trip to a health care facility. In contrast, veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with precancerous skin conditions or to receive a screening for malignant skin cancers.

Click here to continue reading.

There is significant variation among the civilian, active-duty, and veteran populations in regard to dermatologic conditions. Civilians most frequently visit a specialist with complaints of eczema, dermatitis, acne, and other benign conditions. Among active-duty service members, infections and allergic bite reactions are the most common reasons for a trip to a health care facility. In contrast, veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with precancerous skin conditions or to receive a screening for malignant skin cancers.

Click here to continue reading.

There is significant variation among the civilian, active-duty, and veteran populations in regard to dermatologic conditions. Civilians most frequently visit a specialist with complaints of eczema, dermatitis, acne, and other benign conditions. Among active-duty service members, infections and allergic bite reactions are the most common reasons for a trip to a health care facility. In contrast, veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with precancerous skin conditions or to receive a screening for malignant skin cancers.

Click here to continue reading.

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Cardiovascular Diseases

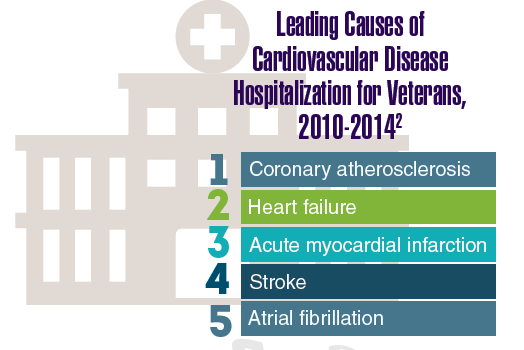

Cardiovascular disease remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. According to the American Heart Association, in the US, every 40 seconds someone experiences a stroke, another person has a heart attack, and a third person dies of cardiovascular disease.1 More than 92 million American adults have some form of cardiovascular disease or poststroke symptoms, and the costs are well above $300 billion.1

Click here to continue reading.

Cardiovascular disease remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. According to the American Heart Association, in the US, every 40 seconds someone experiences a stroke, another person has a heart attack, and a third person dies of cardiovascular disease.1 More than 92 million American adults have some form of cardiovascular disease or poststroke symptoms, and the costs are well above $300 billion.1

Click here to continue reading.

Cardiovascular disease remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. According to the American Heart Association, in the US, every 40 seconds someone experiences a stroke, another person has a heart attack, and a third person dies of cardiovascular disease.1 More than 92 million American adults have some form of cardiovascular disease or poststroke symptoms, and the costs are well above $300 billion.1

Click here to continue reading.

Federal Health Data Trends:Vietnam Era Veterans (FULL)

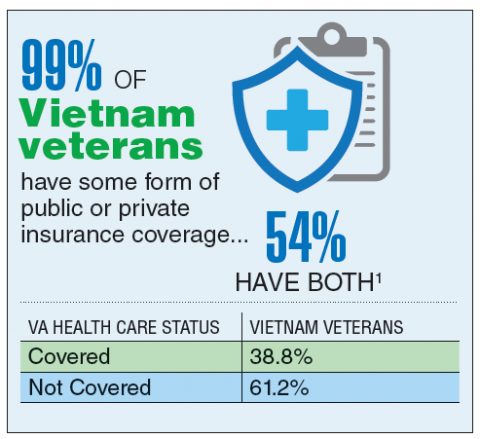

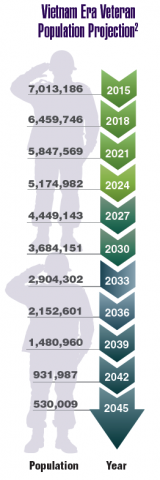

According to the VA, 8,744,000 veterans served in the Armed Forces in the time between the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords.1 Of those, 3,403,000 were deployed to Southeast Asia. Those who served during this period often were exposed to unique environmental hazards, such as commonly used pesticides and herbicides, as well as diseases attributed to the tropical environment, such as fungal infections, and there were more than 40,000 reported cases of malaria. Upon returning home, these veterans faced a tough readjustment that often magnified the stress associated with combat.

Today, the VA recognizes 8 conditions related to service in Vietnam for the purposes of establishing service-connection: soft tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, prostate cancer, acute peripheral neuropathy, and spina bifida in offspring. As the veterans of this conflict age into their retirement years, the VA now also faces the challenge of providing care to this growing senior population.

According to the VA, 8,744,000 veterans served in the Armed Forces in the time between the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords.1 Of those, 3,403,000 were deployed to Southeast Asia. Those who served during this period often were exposed to unique environmental hazards, such as commonly used pesticides and herbicides, as well as diseases attributed to the tropical environment, such as fungal infections, and there were more than 40,000 reported cases of malaria. Upon returning home, these veterans faced a tough readjustment that often magnified the stress associated with combat.

Today, the VA recognizes 8 conditions related to service in Vietnam for the purposes of establishing service-connection: soft tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, prostate cancer, acute peripheral neuropathy, and spina bifida in offspring. As the veterans of this conflict age into their retirement years, the VA now also faces the challenge of providing care to this growing senior population.

According to the VA, 8,744,000 veterans served in the Armed Forces in the time between the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords.1 Of those, 3,403,000 were deployed to Southeast Asia. Those who served during this period often were exposed to unique environmental hazards, such as commonly used pesticides and herbicides, as well as diseases attributed to the tropical environment, such as fungal infections, and there were more than 40,000 reported cases of malaria. Upon returning home, these veterans faced a tough readjustment that often magnified the stress associated with combat.

Today, the VA recognizes 8 conditions related to service in Vietnam for the purposes of establishing service-connection: soft tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, prostate cancer, acute peripheral neuropathy, and spina bifida in offspring. As the veterans of this conflict age into their retirement years, the VA now also faces the challenge of providing care to this growing senior population.

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Gulf War & Post-9/11 Veterans

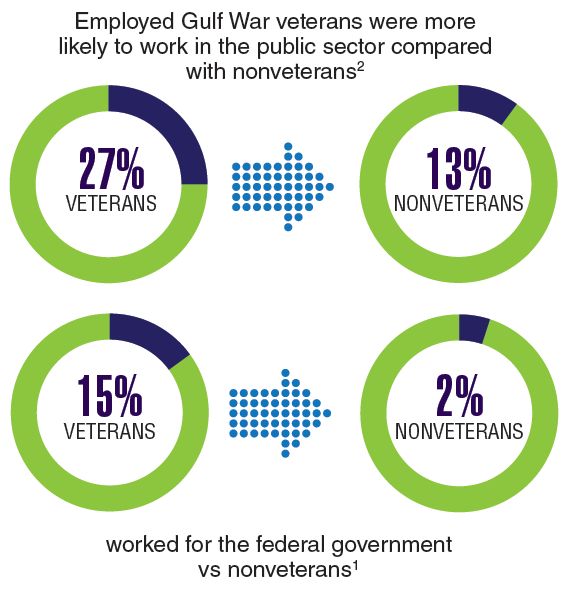

Currently, the largest growing percentage of veterans are those who served during the Gulf War and Post-9/11 era. Over the next few years, nearly every state in the US can expect growth in this veteran population greater than 20%. Although this group of 4.1 million veterans tend to use their VA health benefits less than do the veterans of previous eras, these veterans also exhibit some unique qualities not previously seen in VA patient populations. These veterans already have been identified to be at an increased risk of acquiring several diseases, which include arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and sleep apnea. But perhaps the biggest shift, and the one that could require the most change in the way the Veterans Health Administration provides care, is along gender lines.

Click here to continue reading.

Currently, the largest growing percentage of veterans are those who served during the Gulf War and Post-9/11 era. Over the next few years, nearly every state in the US can expect growth in this veteran population greater than 20%. Although this group of 4.1 million veterans tend to use their VA health benefits less than do the veterans of previous eras, these veterans also exhibit some unique qualities not previously seen in VA patient populations. These veterans already have been identified to be at an increased risk of acquiring several diseases, which include arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and sleep apnea. But perhaps the biggest shift, and the one that could require the most change in the way the Veterans Health Administration provides care, is along gender lines.

Click here to continue reading.

Currently, the largest growing percentage of veterans are those who served during the Gulf War and Post-9/11 era. Over the next few years, nearly every state in the US can expect growth in this veteran population greater than 20%. Although this group of 4.1 million veterans tend to use their VA health benefits less than do the veterans of previous eras, these veterans also exhibit some unique qualities not previously seen in VA patient populations. These veterans already have been identified to be at an increased risk of acquiring several diseases, which include arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and sleep apnea. But perhaps the biggest shift, and the one that could require the most change in the way the Veterans Health Administration provides care, is along gender lines.

Click here to continue reading.

Federal Health Care Data Trends Vietnam Era Veterans

According to the VA, 8,744,000 veterans served in the Armed Forces in the time between the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords.1 Of those, 3,403,000 were deployed to Southeast Asia. Those who served during this period often were exposed to unique environmental hazards, such as commonly used pesticides and herbicides, as well as diseases attributed to the tropical environment, such as fungal infections, and there were more than 40,000 reported cases of malaria. Upon returning home, these veterans faced a tough readjustment that often magnified the stress associated with combat.

Click here to continue reading.

According to the VA, 8,744,000 veterans served in the Armed Forces in the time between the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords.1 Of those, 3,403,000 were deployed to Southeast Asia. Those who served during this period often were exposed to unique environmental hazards, such as commonly used pesticides and herbicides, as well as diseases attributed to the tropical environment, such as fungal infections, and there were more than 40,000 reported cases of malaria. Upon returning home, these veterans faced a tough readjustment that often magnified the stress associated with combat.

Click here to continue reading.

According to the VA, 8,744,000 veterans served in the Armed Forces in the time between the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords.1 Of those, 3,403,000 were deployed to Southeast Asia. Those who served during this period often were exposed to unique environmental hazards, such as commonly used pesticides and herbicides, as well as diseases attributed to the tropical environment, such as fungal infections, and there were more than 40,000 reported cases of malaria. Upon returning home, these veterans faced a tough readjustment that often magnified the stress associated with combat.

Click here to continue reading.

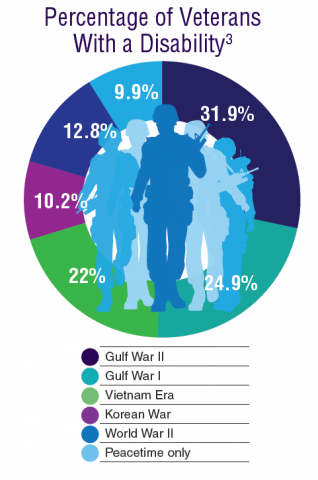

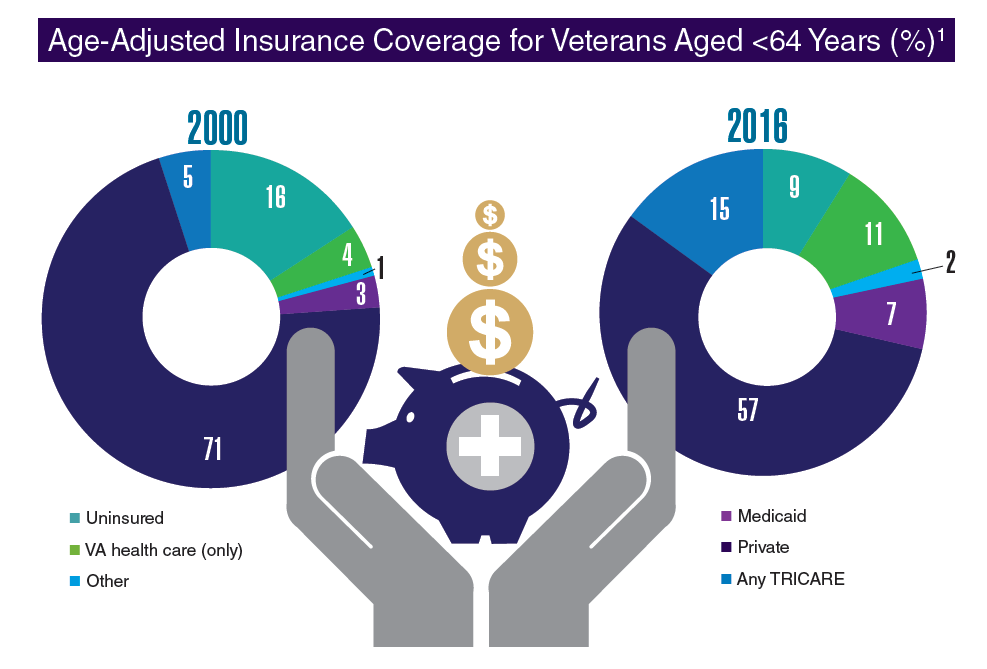

Federal Health Care Data Trends: Veteran Demographics

If there is one thing that the VA and DoD have in common—it’s access to high-quality data. With 8.9 million veterans accessing VA care and another 9.4 million utilizing TRICARE, both the Veterans Health Administration and the TRICARE/Military Health System know a tremendous amount about their population. As a result, the VA, DoD, and independent researchers have amassed a great amount of data about health care diagnoses and outcomes. The goal of this supplement to Federal Practitioner is to help federal health care providers synthesize the data by identifying the most significant research and highlighting key findings. We have pulled together the data from a broad cross-section of researchers and developed infographics to clarify and emphasize some of the most important trends in an easy to understand format.

Click here to continue reading.

If there is one thing that the VA and DoD have in common—it’s access to high-quality data. With 8.9 million veterans accessing VA care and another 9.4 million utilizing TRICARE, both the Veterans Health Administration and the TRICARE/Military Health System know a tremendous amount about their population. As a result, the VA, DoD, and independent researchers have amassed a great amount of data about health care diagnoses and outcomes. The goal of this supplement to Federal Practitioner is to help federal health care providers synthesize the data by identifying the most significant research and highlighting key findings. We have pulled together the data from a broad cross-section of researchers and developed infographics to clarify and emphasize some of the most important trends in an easy to understand format.

Click here to continue reading.

If there is one thing that the VA and DoD have in common—it’s access to high-quality data. With 8.9 million veterans accessing VA care and another 9.4 million utilizing TRICARE, both the Veterans Health Administration and the TRICARE/Military Health System know a tremendous amount about their population. As a result, the VA, DoD, and independent researchers have amassed a great amount of data about health care diagnoses and outcomes. The goal of this supplement to Federal Practitioner is to help federal health care providers synthesize the data by identifying the most significant research and highlighting key findings. We have pulled together the data from a broad cross-section of researchers and developed infographics to clarify and emphasize some of the most important trends in an easy to understand format.

Click here to continue reading.

Major PHS Cuts Proposed in Reorg Plan

The Trump administration seeks to reorganize several federal agencies as part of a sweeping reform proposal, issued June 21. Although the plans hits many parts of federal health care, the most dramatic change is a proposed reduction of the Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps from more than 6,000 officers to no more than 4,500.

“Government in the 21st century is fundamentally a services business, and modern information technology should be at the heart of the U.S. government service delivery model,” according to the administration’s reform proposal. “And yet, today’s Executive branch is still aligned to the stove-piped organizational constructs of the 20th century, which in many cases have grown inefficient and out of date. Consequently, the public and our workforce are frustrated with government’s ability to deliver its mission in an effective, efficient, and secure way.”

If implemented, changes to the Commissioned Corp would be dramatic. The plan directs the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “civilianize officers who do not provide critical public health services” and to ensure that the Corps is deployed at least once every 3 years to positions that either are difficult to fill or respond to a public health emergency. Instead the Commissioned Corps would be replaced with a Reserve Corps. Similar to the armed forces reserves, this group “would consist of Government employees and private citizens who agree to be deployed and serve in times of national need.” In addition, the plan would change the way federal agencies pay for the retirement benefits of Commissioned Corps members, potentially eliminating one of the fiscal benefits that agencies receive for hiring Commissioned Corps members.

In addition, under the proposal, nutrition assistance programs currently run out of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) would move to the Department of Health and Human Services, which would be rebranded the Department of Health and Public Welfare.

Moving these programs “would allow for better and easier coordination across programs that serve similar populations, ensuring consistent policies and a single point of administration for the major public assistance programs,” according to the proposal. “This single point of administration would lead to reduced duplication in state reporting requirements and other administrative burdens, and a more streamlined process for issuing guidance, writing regulations, and approving waivers.”

Food oversight functions would move from the Food and Drug Administration to the USDA; FDA would be rebranded the Federal Drug Administration and focus on drugs, devices, biologics, tobacco, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The administration also proposed to create a Council on Public Assistance comprised of “all federal agencies that administer public benefits, with a statutory authority to set cross-cutting program policies, including uniform work requirements.”

Other functions of the council would include approving service plans and waivers by states under Welfare-to-Work projects; resolving disputes when multiple agencies disagree on a particular policy; and recommending policy changes to eliminate barriers at the federal, state, and local level to getting welfare beneficiaries to work.

The proposal also calls for a restructuring of the National Institutes of Health “to ensure operations are effective and efficient,” with no detail provided. It would also place the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under the auspices of NIH.

The Strategic National Stockpile would be managed by the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response “to consolidate strategic decision making around the development and procurement of medical countermeasures, and streamline operational decisions during responses to public health and other emergencies to improve responsiveness.”

Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), the ranking member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, was quick to dismiss the plan, labeling it as “futile” and an “attempt to make government work worse for the people it serves.”

This article originally appeared at Internal Medicine News. It has been edited for Federal Practitioner and includes additional reporting by Reid Paul.

The Trump administration seeks to reorganize several federal agencies as part of a sweeping reform proposal, issued June 21. Although the plans hits many parts of federal health care, the most dramatic change is a proposed reduction of the Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps from more than 6,000 officers to no more than 4,500.

“Government in the 21st century is fundamentally a services business, and modern information technology should be at the heart of the U.S. government service delivery model,” according to the administration’s reform proposal. “And yet, today’s Executive branch is still aligned to the stove-piped organizational constructs of the 20th century, which in many cases have grown inefficient and out of date. Consequently, the public and our workforce are frustrated with government’s ability to deliver its mission in an effective, efficient, and secure way.”

If implemented, changes to the Commissioned Corp would be dramatic. The plan directs the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “civilianize officers who do not provide critical public health services” and to ensure that the Corps is deployed at least once every 3 years to positions that either are difficult to fill or respond to a public health emergency. Instead the Commissioned Corps would be replaced with a Reserve Corps. Similar to the armed forces reserves, this group “would consist of Government employees and private citizens who agree to be deployed and serve in times of national need.” In addition, the plan would change the way federal agencies pay for the retirement benefits of Commissioned Corps members, potentially eliminating one of the fiscal benefits that agencies receive for hiring Commissioned Corps members.

In addition, under the proposal, nutrition assistance programs currently run out of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) would move to the Department of Health and Human Services, which would be rebranded the Department of Health and Public Welfare.

Moving these programs “would allow for better and easier coordination across programs that serve similar populations, ensuring consistent policies and a single point of administration for the major public assistance programs,” according to the proposal. “This single point of administration would lead to reduced duplication in state reporting requirements and other administrative burdens, and a more streamlined process for issuing guidance, writing regulations, and approving waivers.”

Food oversight functions would move from the Food and Drug Administration to the USDA; FDA would be rebranded the Federal Drug Administration and focus on drugs, devices, biologics, tobacco, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The administration also proposed to create a Council on Public Assistance comprised of “all federal agencies that administer public benefits, with a statutory authority to set cross-cutting program policies, including uniform work requirements.”

Other functions of the council would include approving service plans and waivers by states under Welfare-to-Work projects; resolving disputes when multiple agencies disagree on a particular policy; and recommending policy changes to eliminate barriers at the federal, state, and local level to getting welfare beneficiaries to work.

The proposal also calls for a restructuring of the National Institutes of Health “to ensure operations are effective and efficient,” with no detail provided. It would also place the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under the auspices of NIH.

The Strategic National Stockpile would be managed by the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response “to consolidate strategic decision making around the development and procurement of medical countermeasures, and streamline operational decisions during responses to public health and other emergencies to improve responsiveness.”

Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), the ranking member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, was quick to dismiss the plan, labeling it as “futile” and an “attempt to make government work worse for the people it serves.”

This article originally appeared at Internal Medicine News. It has been edited for Federal Practitioner and includes additional reporting by Reid Paul.

The Trump administration seeks to reorganize several federal agencies as part of a sweeping reform proposal, issued June 21. Although the plans hits many parts of federal health care, the most dramatic change is a proposed reduction of the Public Health Service (PHS) Commissioned Corps from more than 6,000 officers to no more than 4,500.

“Government in the 21st century is fundamentally a services business, and modern information technology should be at the heart of the U.S. government service delivery model,” according to the administration’s reform proposal. “And yet, today’s Executive branch is still aligned to the stove-piped organizational constructs of the 20th century, which in many cases have grown inefficient and out of date. Consequently, the public and our workforce are frustrated with government’s ability to deliver its mission in an effective, efficient, and secure way.”

If implemented, changes to the Commissioned Corp would be dramatic. The plan directs the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “civilianize officers who do not provide critical public health services” and to ensure that the Corps is deployed at least once every 3 years to positions that either are difficult to fill or respond to a public health emergency. Instead the Commissioned Corps would be replaced with a Reserve Corps. Similar to the armed forces reserves, this group “would consist of Government employees and private citizens who agree to be deployed and serve in times of national need.” In addition, the plan would change the way federal agencies pay for the retirement benefits of Commissioned Corps members, potentially eliminating one of the fiscal benefits that agencies receive for hiring Commissioned Corps members.

In addition, under the proposal, nutrition assistance programs currently run out of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) would move to the Department of Health and Human Services, which would be rebranded the Department of Health and Public Welfare.

Moving these programs “would allow for better and easier coordination across programs that serve similar populations, ensuring consistent policies and a single point of administration for the major public assistance programs,” according to the proposal. “This single point of administration would lead to reduced duplication in state reporting requirements and other administrative burdens, and a more streamlined process for issuing guidance, writing regulations, and approving waivers.”

Food oversight functions would move from the Food and Drug Administration to the USDA; FDA would be rebranded the Federal Drug Administration and focus on drugs, devices, biologics, tobacco, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The administration also proposed to create a Council on Public Assistance comprised of “all federal agencies that administer public benefits, with a statutory authority to set cross-cutting program policies, including uniform work requirements.”

Other functions of the council would include approving service plans and waivers by states under Welfare-to-Work projects; resolving disputes when multiple agencies disagree on a particular policy; and recommending policy changes to eliminate barriers at the federal, state, and local level to getting welfare beneficiaries to work.

The proposal also calls for a restructuring of the National Institutes of Health “to ensure operations are effective and efficient,” with no detail provided. It would also place the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under the auspices of NIH.

The Strategic National Stockpile would be managed by the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response “to consolidate strategic decision making around the development and procurement of medical countermeasures, and streamline operational decisions during responses to public health and other emergencies to improve responsiveness.”

Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), the ranking member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, was quick to dismiss the plan, labeling it as “futile” and an “attempt to make government work worse for the people it serves.”

This article originally appeared at Internal Medicine News. It has been edited for Federal Practitioner and includes additional reporting by Reid Paul.

Veterans Can Now Access Medical Images and Reports Online

Veterans with a premium account on My HealtheVet no longer need to make an in-person visit to get their medical images and associated study reports—now they can do it online. VA Medical Images and Reports allows users to view, download, and share copies of their radiology studies, including x-rays, mammograms, MRIs, and CTs, from the VA Electronic Health Record.

Radiology studies are available in My HealtheVet 3 calendar days after the study report has been verified. When a request for a specific study is completed, veterans can view a lower resolution thumbnail copy of the images and the radiology report online or download a zip file with the information. For studies with large files, the user can opt to receive an e-mail notification when the download request is complete.

To view diagnostic-quality images, veterans may install a free medical image viewer on their computer. The images and reports can be copied to a CD, DVD, USB flash drive, or any portable drive to share with providers, across VA settings and outside the VA.

Veterans with a premium account on My HealtheVet no longer need to make an in-person visit to get their medical images and associated study reports—now they can do it online. VA Medical Images and Reports allows users to view, download, and share copies of their radiology studies, including x-rays, mammograms, MRIs, and CTs, from the VA Electronic Health Record.

Radiology studies are available in My HealtheVet 3 calendar days after the study report has been verified. When a request for a specific study is completed, veterans can view a lower resolution thumbnail copy of the images and the radiology report online or download a zip file with the information. For studies with large files, the user can opt to receive an e-mail notification when the download request is complete.

To view diagnostic-quality images, veterans may install a free medical image viewer on their computer. The images and reports can be copied to a CD, DVD, USB flash drive, or any portable drive to share with providers, across VA settings and outside the VA.

Veterans with a premium account on My HealtheVet no longer need to make an in-person visit to get their medical images and associated study reports—now they can do it online. VA Medical Images and Reports allows users to view, download, and share copies of their radiology studies, including x-rays, mammograms, MRIs, and CTs, from the VA Electronic Health Record.

Radiology studies are available in My HealtheVet 3 calendar days after the study report has been verified. When a request for a specific study is completed, veterans can view a lower resolution thumbnail copy of the images and the radiology report online or download a zip file with the information. For studies with large files, the user can opt to receive an e-mail notification when the download request is complete.

To view diagnostic-quality images, veterans may install a free medical image viewer on their computer. The images and reports can be copied to a CD, DVD, USB flash drive, or any portable drive to share with providers, across VA settings and outside the VA.

The VA Cannot Be Privatized

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).