User login

The people behind the Journal really matter

Our goal at the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine is to provide timely, readily digestible, and useful clinical information to our readers. To do so, we need authors who buy into our educational mission, but we also need conscientious peer reviewers and an editorial staff capable of turning “doctorese” into readily understood English.

Our physician deputy editors Pelin Batur and James Pile solicit articles, guide authors, draft and revise CME questions, and assist greatly in the peer review process. Our nonphysician editors edit manuscripts to achieve a consistent editorial style in all of our published papers, but they serve many other key functions. They manage the business of publishing a monthly journal at a time of drastically shrinking advertising revenue, they ensure that Journal content complies with rules for CME material published in print and online, and they keep up with continuous changes in online publishing. The Journal receives significant funding from Cleveland Clinic’s Education Institute, funding we need to pursue our role as an independent, peer-reviewed conveyer of clinical information.

I write this to emphasize that real people manage all of these tasks, and to gratefully acknowledge two people who are leaving the Journal: Mr. Joseph Dennehy and Dr. James Pile.

Long-time sales and marketing director Joe Dennehy played a key role in the Journal’s rise from relative obscurity about 20 years ago. This period was marked by many hospital-based journals closing up shop. Published since 1931, the Journal was relaunched in 1995 as a resource for postgraduate medical education with a national and international reach. Joe was brought in to guide and implement the marketing of the Journal as an independent, high-quality, clinical educational journal to increase its attractiveness as an advertising medium for the pharmaceutical industry so we could at least partly defray the significant expenses of publishing.

Joe is well known to medical publishers and media buyers, and over the past 20 years he became the face of the Journal in sales and marketing circles. In 2010, the Association of Medical Media recognized Joe’s achievements at its 18th Annual Nexus Representatives of the Year Awards, which acknowledge outstanding sales and marketing directors for their superior service, professionalism, and communication of ideas. Joe exemplifies these qualities and has been an inspiration to those of us who know and work with him. He has fully understood the sincerity of our mission and has never asked us to stray from it. Although Joe and his wife Holly live in New York, they are part of the Cleveland-based Journal family, and we will miss them. We wish them happiness and good health.

Dr. James Pile is an internal medicine hospitalist, an infectious disease specialist, and a superior medical educator. His work with us for the past several years has enhanced the Journal’s educational value for practicing hospitalists. His working familiarity with clinical leaders in the Society of Hospital Medicine has provided us with willing and skilled peer reviewers. Jim is now transitioning to a role as director of the internal medicine residency program at MetroHealth Medical Center, also here in Cleveland. He will continue to be a clinical resource for us as author and reviewer, but his ever-calm demeanor and clinical common sense will be hard to replace.

The Journal continues to evolve with the publishing times. We are assuming a greater presence in the digital world and adjusting to an environment of ever-diminishing advertising revenue. But with the work of our editorial team (I invite you to periodically glance at our masthead to note our team of writers, managers, and production staff), we intend to stay true to our educational mission. Our personal thanks to Joe and Jim for their contributions of the past, and to our current team in Scientific Publications for their ongoing and very personal commitment to providing the highest quality medical education that we can.

Our goal at the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine is to provide timely, readily digestible, and useful clinical information to our readers. To do so, we need authors who buy into our educational mission, but we also need conscientious peer reviewers and an editorial staff capable of turning “doctorese” into readily understood English.

Our physician deputy editors Pelin Batur and James Pile solicit articles, guide authors, draft and revise CME questions, and assist greatly in the peer review process. Our nonphysician editors edit manuscripts to achieve a consistent editorial style in all of our published papers, but they serve many other key functions. They manage the business of publishing a monthly journal at a time of drastically shrinking advertising revenue, they ensure that Journal content complies with rules for CME material published in print and online, and they keep up with continuous changes in online publishing. The Journal receives significant funding from Cleveland Clinic’s Education Institute, funding we need to pursue our role as an independent, peer-reviewed conveyer of clinical information.

I write this to emphasize that real people manage all of these tasks, and to gratefully acknowledge two people who are leaving the Journal: Mr. Joseph Dennehy and Dr. James Pile.

Long-time sales and marketing director Joe Dennehy played a key role in the Journal’s rise from relative obscurity about 20 years ago. This period was marked by many hospital-based journals closing up shop. Published since 1931, the Journal was relaunched in 1995 as a resource for postgraduate medical education with a national and international reach. Joe was brought in to guide and implement the marketing of the Journal as an independent, high-quality, clinical educational journal to increase its attractiveness as an advertising medium for the pharmaceutical industry so we could at least partly defray the significant expenses of publishing.

Joe is well known to medical publishers and media buyers, and over the past 20 years he became the face of the Journal in sales and marketing circles. In 2010, the Association of Medical Media recognized Joe’s achievements at its 18th Annual Nexus Representatives of the Year Awards, which acknowledge outstanding sales and marketing directors for their superior service, professionalism, and communication of ideas. Joe exemplifies these qualities and has been an inspiration to those of us who know and work with him. He has fully understood the sincerity of our mission and has never asked us to stray from it. Although Joe and his wife Holly live in New York, they are part of the Cleveland-based Journal family, and we will miss them. We wish them happiness and good health.

Dr. James Pile is an internal medicine hospitalist, an infectious disease specialist, and a superior medical educator. His work with us for the past several years has enhanced the Journal’s educational value for practicing hospitalists. His working familiarity with clinical leaders in the Society of Hospital Medicine has provided us with willing and skilled peer reviewers. Jim is now transitioning to a role as director of the internal medicine residency program at MetroHealth Medical Center, also here in Cleveland. He will continue to be a clinical resource for us as author and reviewer, but his ever-calm demeanor and clinical common sense will be hard to replace.

The Journal continues to evolve with the publishing times. We are assuming a greater presence in the digital world and adjusting to an environment of ever-diminishing advertising revenue. But with the work of our editorial team (I invite you to periodically glance at our masthead to note our team of writers, managers, and production staff), we intend to stay true to our educational mission. Our personal thanks to Joe and Jim for their contributions of the past, and to our current team in Scientific Publications for their ongoing and very personal commitment to providing the highest quality medical education that we can.

Our goal at the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine is to provide timely, readily digestible, and useful clinical information to our readers. To do so, we need authors who buy into our educational mission, but we also need conscientious peer reviewers and an editorial staff capable of turning “doctorese” into readily understood English.

Our physician deputy editors Pelin Batur and James Pile solicit articles, guide authors, draft and revise CME questions, and assist greatly in the peer review process. Our nonphysician editors edit manuscripts to achieve a consistent editorial style in all of our published papers, but they serve many other key functions. They manage the business of publishing a monthly journal at a time of drastically shrinking advertising revenue, they ensure that Journal content complies with rules for CME material published in print and online, and they keep up with continuous changes in online publishing. The Journal receives significant funding from Cleveland Clinic’s Education Institute, funding we need to pursue our role as an independent, peer-reviewed conveyer of clinical information.

I write this to emphasize that real people manage all of these tasks, and to gratefully acknowledge two people who are leaving the Journal: Mr. Joseph Dennehy and Dr. James Pile.

Long-time sales and marketing director Joe Dennehy played a key role in the Journal’s rise from relative obscurity about 20 years ago. This period was marked by many hospital-based journals closing up shop. Published since 1931, the Journal was relaunched in 1995 as a resource for postgraduate medical education with a national and international reach. Joe was brought in to guide and implement the marketing of the Journal as an independent, high-quality, clinical educational journal to increase its attractiveness as an advertising medium for the pharmaceutical industry so we could at least partly defray the significant expenses of publishing.

Joe is well known to medical publishers and media buyers, and over the past 20 years he became the face of the Journal in sales and marketing circles. In 2010, the Association of Medical Media recognized Joe’s achievements at its 18th Annual Nexus Representatives of the Year Awards, which acknowledge outstanding sales and marketing directors for their superior service, professionalism, and communication of ideas. Joe exemplifies these qualities and has been an inspiration to those of us who know and work with him. He has fully understood the sincerity of our mission and has never asked us to stray from it. Although Joe and his wife Holly live in New York, they are part of the Cleveland-based Journal family, and we will miss them. We wish them happiness and good health.

Dr. James Pile is an internal medicine hospitalist, an infectious disease specialist, and a superior medical educator. His work with us for the past several years has enhanced the Journal’s educational value for practicing hospitalists. His working familiarity with clinical leaders in the Society of Hospital Medicine has provided us with willing and skilled peer reviewers. Jim is now transitioning to a role as director of the internal medicine residency program at MetroHealth Medical Center, also here in Cleveland. He will continue to be a clinical resource for us as author and reviewer, but his ever-calm demeanor and clinical common sense will be hard to replace.

The Journal continues to evolve with the publishing times. We are assuming a greater presence in the digital world and adjusting to an environment of ever-diminishing advertising revenue. But with the work of our editorial team (I invite you to periodically glance at our masthead to note our team of writers, managers, and production staff), we intend to stay true to our educational mission. Our personal thanks to Joe and Jim for their contributions of the past, and to our current team in Scientific Publications for their ongoing and very personal commitment to providing the highest quality medical education that we can.

In which clinical situations can the use of the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (Mirena) and the TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard) be extended?

One of the most important medical interventions to improve maternal-child health is providing effective contraception to men and women of reproductive age. The 52-mg levonorgestrel-intrauterine device (LNG-IUD; Mirena) is one of the most effective forms of reversible contraception available to women, with a failure rate of 1.1% over 5 years of use.1 The TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard), another highly effective reversible contraceptive, is reported to have failure rates of approximately 1.4% and 2.2%, over 5 and 10 years of use.2

An interesting question is whether—in certain clinical situations—a single IUD can be used for longer than the currently recommended 5 and 10 years for a Mirena IUD and a ParaGard IUD, respectively.

The LNG-IUD containing 52 mg LNG may be effective up to 7 years

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) package insert for the Mirena 52-mg LNG-IUD states that the device is “indicated for contraception for up to 5 years. Thereafter if continued contraception is desired, the system should be replaced.”1 The FDA package insert for the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, Liletta 52-mg LNG-IUD, states that it is “indicated for prevention of pregnancy up to 3 years.”3 The FDA guidance is based on data submitted to the agency by the manufacturers to support the approval process. Completing large-scale clinical trials that extend past 5 years or more is challenging, because of the cost and the loss of study participants to follow-up. Hence, few clinical trials of contraceptive IUDs continue for more than 5 to 10 years.

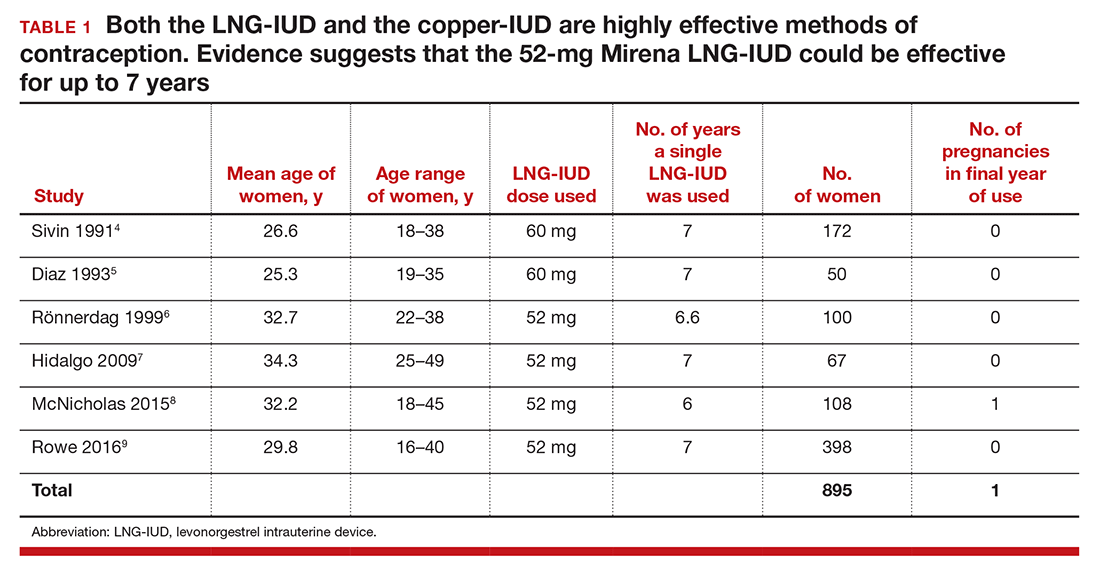

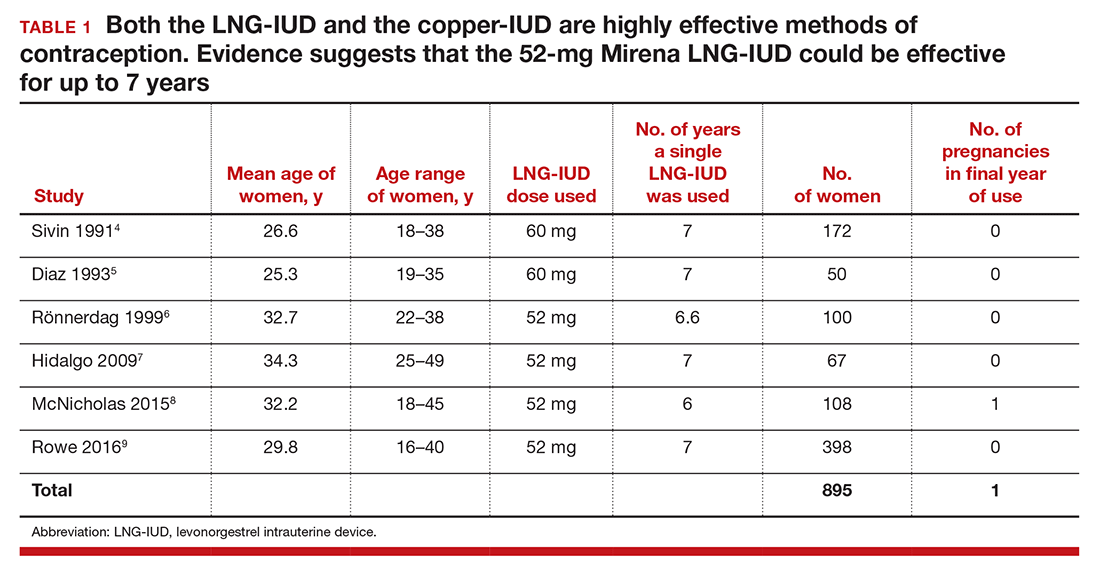

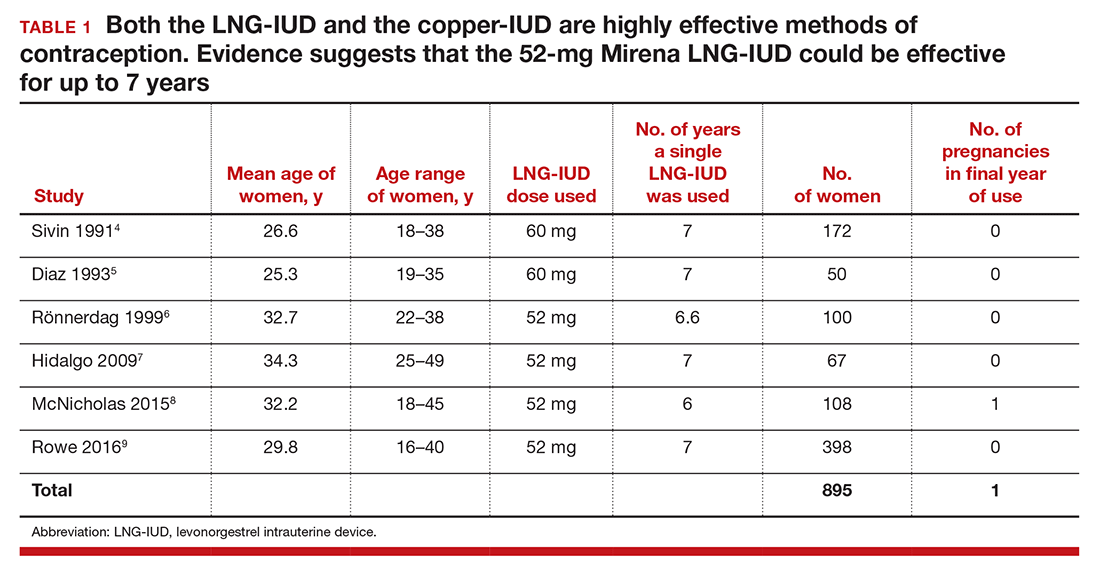

Although the FDA-approved indication for Mirena and Liletta is 5 and 3 years, respectively, evidence suggests that the 52-mg LNG-IUD is an effective contraceptive beyond 5 years. In fact, multiple studies report that this IUD is an effective contraceptive for at least 6 or 7 years (TABLE 1).4–9 Among 895 women using the 52-mg LNG-IUD for 6 to 7 years, only 1 pregnancy was reported in the last year of use. In that case, the IUD was in the cervix and partially expelled from the uterus.8 These data indicate that the 52-mg LNG-IUD is likely an effective contraceptive for up to 7 years, with pregnancy rates below 1% in the last year of use.

The TCu380A copper-IUD is effective up to 12 years

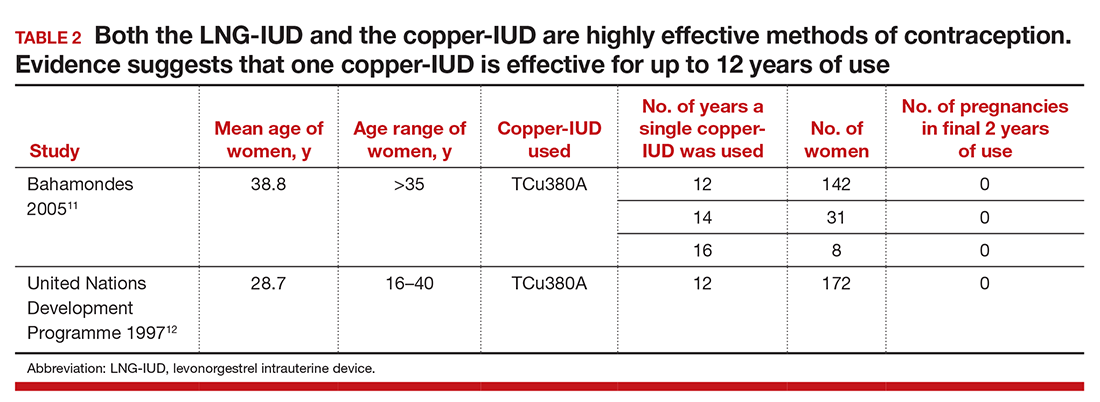

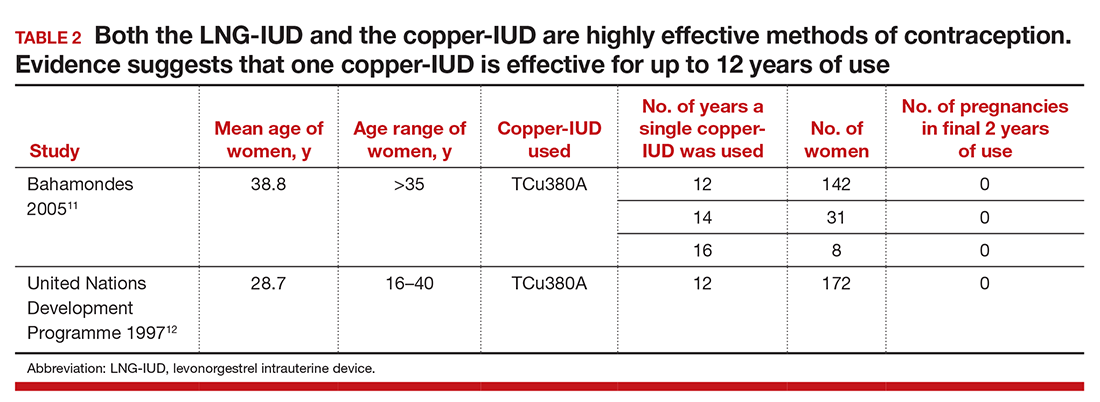

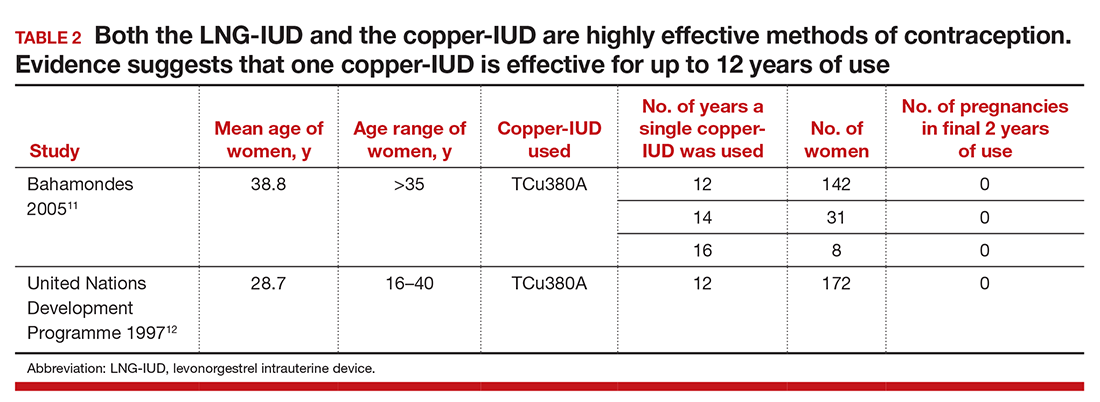

The currently available TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard) is FDA approved for 10 years.2 Studies evaluating the efficacy of this copper-IUD are limited, but those that have been published reported that it is effective for at least 12 years and possibly up to 20 years (TABLE 2).10−13

Recently I saw a patient who had a copper-IUD (ParaGard, TCu380A) inserted as a teen after a birth, and had successfully used the same device for 17 years. She presented for removal of the IUD so that she could attempt conception. After removal of the IUD, copper wire was visible on the device. Long-term studies of the TCu220 copper-IUD, which contains less copper than the ParaGard, report pregnancies with the use of the device beyond 10 years.12 These devices, which are not available in the United States, should not be used past their recommended interval.

- Mirena [package insert]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; July 2008. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021225s019lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- ParaGard [package insert]. N. Tonawanda, NY: FEI Women’s Health LLC; revised September 2005. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/018680s060lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- Liletta [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Actavis Pharma, Inc; February 2015. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206229s000lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- Sivin I, Stern J, Coutinho E, et al. Prolonged intrauterine contraception: a seven-year randomized study of the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T380 Ag IUDS. Contraception. 1991;44(5):473–480.

- Díaz J, Faúndes A, Díaz M, Marchi N. Evaluation of the clinical performance of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, up to seven years of use, in Campinas, Brazil. Contraception. 1993;47(2):169–175.

- Rönnerdag M, Odlind V. Health effects of long-term use of the intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing system. A follow-up study over 12 years of continuous use. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(8):716–721.

- Hidalgo MM, Hidalgo-Regina C, Bahamondes MV, Monteiro I, Petta CA, Bahamondes L. Serum levonorgestrel levels and endometrial thickness during extended use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2009;80(1):84–89.

- McNicholas C, Maddipati R, Zhao Q, Swor E, Peipert JF. Use of the etonogestrel implant and levonorgestrel intrauterine device beyond the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved duration. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):599–604.

- Rowe P, Farley T, Peregoudov A, et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93(6):498–506.

- Wu JP, Pickle S. Extended use of the intrauterine device: a literature review and recommendations for clinical practice. Contraception. 2014;89(6):495–503.

- Bahamondes L, Faundes A, Sobreira-Lima B, Liu-Filho JF, Pecci P, Matera S. TCu 380A IUD: a reversible permanent contraceptive method in women over 35 years of age. Contraception. 2005;72(5):337–341.

- United Nations Development Programme. Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with the TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56(6):341–352.

- Sivin I. Utility and drawbacks of continuous use of a copper T IUD for 20 years. Contraception. 2007;75(6 suppl):S70–S75.

One of the most important medical interventions to improve maternal-child health is providing effective contraception to men and women of reproductive age. The 52-mg levonorgestrel-intrauterine device (LNG-IUD; Mirena) is one of the most effective forms of reversible contraception available to women, with a failure rate of 1.1% over 5 years of use.1 The TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard), another highly effective reversible contraceptive, is reported to have failure rates of approximately 1.4% and 2.2%, over 5 and 10 years of use.2

An interesting question is whether—in certain clinical situations—a single IUD can be used for longer than the currently recommended 5 and 10 years for a Mirena IUD and a ParaGard IUD, respectively.

The LNG-IUD containing 52 mg LNG may be effective up to 7 years

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) package insert for the Mirena 52-mg LNG-IUD states that the device is “indicated for contraception for up to 5 years. Thereafter if continued contraception is desired, the system should be replaced.”1 The FDA package insert for the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, Liletta 52-mg LNG-IUD, states that it is “indicated for prevention of pregnancy up to 3 years.”3 The FDA guidance is based on data submitted to the agency by the manufacturers to support the approval process. Completing large-scale clinical trials that extend past 5 years or more is challenging, because of the cost and the loss of study participants to follow-up. Hence, few clinical trials of contraceptive IUDs continue for more than 5 to 10 years.

Although the FDA-approved indication for Mirena and Liletta is 5 and 3 years, respectively, evidence suggests that the 52-mg LNG-IUD is an effective contraceptive beyond 5 years. In fact, multiple studies report that this IUD is an effective contraceptive for at least 6 or 7 years (TABLE 1).4–9 Among 895 women using the 52-mg LNG-IUD for 6 to 7 years, only 1 pregnancy was reported in the last year of use. In that case, the IUD was in the cervix and partially expelled from the uterus.8 These data indicate that the 52-mg LNG-IUD is likely an effective contraceptive for up to 7 years, with pregnancy rates below 1% in the last year of use.

The TCu380A copper-IUD is effective up to 12 years

The currently available TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard) is FDA approved for 10 years.2 Studies evaluating the efficacy of this copper-IUD are limited, but those that have been published reported that it is effective for at least 12 years and possibly up to 20 years (TABLE 2).10−13

Recently I saw a patient who had a copper-IUD (ParaGard, TCu380A) inserted as a teen after a birth, and had successfully used the same device for 17 years. She presented for removal of the IUD so that she could attempt conception. After removal of the IUD, copper wire was visible on the device. Long-term studies of the TCu220 copper-IUD, which contains less copper than the ParaGard, report pregnancies with the use of the device beyond 10 years.12 These devices, which are not available in the United States, should not be used past their recommended interval.

One of the most important medical interventions to improve maternal-child health is providing effective contraception to men and women of reproductive age. The 52-mg levonorgestrel-intrauterine device (LNG-IUD; Mirena) is one of the most effective forms of reversible contraception available to women, with a failure rate of 1.1% over 5 years of use.1 The TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard), another highly effective reversible contraceptive, is reported to have failure rates of approximately 1.4% and 2.2%, over 5 and 10 years of use.2

An interesting question is whether—in certain clinical situations—a single IUD can be used for longer than the currently recommended 5 and 10 years for a Mirena IUD and a ParaGard IUD, respectively.

The LNG-IUD containing 52 mg LNG may be effective up to 7 years

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) package insert for the Mirena 52-mg LNG-IUD states that the device is “indicated for contraception for up to 5 years. Thereafter if continued contraception is desired, the system should be replaced.”1 The FDA package insert for the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, Liletta 52-mg LNG-IUD, states that it is “indicated for prevention of pregnancy up to 3 years.”3 The FDA guidance is based on data submitted to the agency by the manufacturers to support the approval process. Completing large-scale clinical trials that extend past 5 years or more is challenging, because of the cost and the loss of study participants to follow-up. Hence, few clinical trials of contraceptive IUDs continue for more than 5 to 10 years.

Although the FDA-approved indication for Mirena and Liletta is 5 and 3 years, respectively, evidence suggests that the 52-mg LNG-IUD is an effective contraceptive beyond 5 years. In fact, multiple studies report that this IUD is an effective contraceptive for at least 6 or 7 years (TABLE 1).4–9 Among 895 women using the 52-mg LNG-IUD for 6 to 7 years, only 1 pregnancy was reported in the last year of use. In that case, the IUD was in the cervix and partially expelled from the uterus.8 These data indicate that the 52-mg LNG-IUD is likely an effective contraceptive for up to 7 years, with pregnancy rates below 1% in the last year of use.

The TCu380A copper-IUD is effective up to 12 years

The currently available TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard) is FDA approved for 10 years.2 Studies evaluating the efficacy of this copper-IUD are limited, but those that have been published reported that it is effective for at least 12 years and possibly up to 20 years (TABLE 2).10−13

Recently I saw a patient who had a copper-IUD (ParaGard, TCu380A) inserted as a teen after a birth, and had successfully used the same device for 17 years. She presented for removal of the IUD so that she could attempt conception. After removal of the IUD, copper wire was visible on the device. Long-term studies of the TCu220 copper-IUD, which contains less copper than the ParaGard, report pregnancies with the use of the device beyond 10 years.12 These devices, which are not available in the United States, should not be used past their recommended interval.

- Mirena [package insert]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; July 2008. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021225s019lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- ParaGard [package insert]. N. Tonawanda, NY: FEI Women’s Health LLC; revised September 2005. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/018680s060lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- Liletta [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Actavis Pharma, Inc; February 2015. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206229s000lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- Sivin I, Stern J, Coutinho E, et al. Prolonged intrauterine contraception: a seven-year randomized study of the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T380 Ag IUDS. Contraception. 1991;44(5):473–480.

- Díaz J, Faúndes A, Díaz M, Marchi N. Evaluation of the clinical performance of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, up to seven years of use, in Campinas, Brazil. Contraception. 1993;47(2):169–175.

- Rönnerdag M, Odlind V. Health effects of long-term use of the intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing system. A follow-up study over 12 years of continuous use. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(8):716–721.

- Hidalgo MM, Hidalgo-Regina C, Bahamondes MV, Monteiro I, Petta CA, Bahamondes L. Serum levonorgestrel levels and endometrial thickness during extended use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2009;80(1):84–89.

- McNicholas C, Maddipati R, Zhao Q, Swor E, Peipert JF. Use of the etonogestrel implant and levonorgestrel intrauterine device beyond the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved duration. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):599–604.

- Rowe P, Farley T, Peregoudov A, et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93(6):498–506.

- Wu JP, Pickle S. Extended use of the intrauterine device: a literature review and recommendations for clinical practice. Contraception. 2014;89(6):495–503.

- Bahamondes L, Faundes A, Sobreira-Lima B, Liu-Filho JF, Pecci P, Matera S. TCu 380A IUD: a reversible permanent contraceptive method in women over 35 years of age. Contraception. 2005;72(5):337–341.

- United Nations Development Programme. Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with the TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56(6):341–352.

- Sivin I. Utility and drawbacks of continuous use of a copper T IUD for 20 years. Contraception. 2007;75(6 suppl):S70–S75.

- Mirena [package insert]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; July 2008. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021225s019lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- ParaGard [package insert]. N. Tonawanda, NY: FEI Women’s Health LLC; revised September 2005. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/018680s060lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- Liletta [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Actavis Pharma, Inc; February 2015. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206229s000lbl.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- Sivin I, Stern J, Coutinho E, et al. Prolonged intrauterine contraception: a seven-year randomized study of the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T380 Ag IUDS. Contraception. 1991;44(5):473–480.

- Díaz J, Faúndes A, Díaz M, Marchi N. Evaluation of the clinical performance of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, up to seven years of use, in Campinas, Brazil. Contraception. 1993;47(2):169–175.

- Rönnerdag M, Odlind V. Health effects of long-term use of the intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing system. A follow-up study over 12 years of continuous use. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(8):716–721.

- Hidalgo MM, Hidalgo-Regina C, Bahamondes MV, Monteiro I, Petta CA, Bahamondes L. Serum levonorgestrel levels and endometrial thickness during extended use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2009;80(1):84–89.

- McNicholas C, Maddipati R, Zhao Q, Swor E, Peipert JF. Use of the etonogestrel implant and levonorgestrel intrauterine device beyond the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved duration. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):599–604.

- Rowe P, Farley T, Peregoudov A, et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93(6):498–506.

- Wu JP, Pickle S. Extended use of the intrauterine device: a literature review and recommendations for clinical practice. Contraception. 2014;89(6):495–503.

- Bahamondes L, Faundes A, Sobreira-Lima B, Liu-Filho JF, Pecci P, Matera S. TCu 380A IUD: a reversible permanent contraceptive method in women over 35 years of age. Contraception. 2005;72(5):337–341.

- United Nations Development Programme. Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with the TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56(6):341–352.

- Sivin I. Utility and drawbacks of continuous use of a copper T IUD for 20 years. Contraception. 2007;75(6 suppl):S70–S75.

It’s health care … but not as we know it

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Introducing Dr. Tyler G. Hughes

I feel honored to join Tyler G. Hughes as co-Editor of the ACS Surgery News and I am excited to work with its Managing Editor, Therese Borden, to bring to its readers breaking information on a broad range of subjects of interest and importance to practicing surgeons. Although we have a great challenge to fill the giant shoes of our immediate predecessor, Layton “Bing” Rikkers, we will do our best to address the vexing clinical, economic, social, and administrative challenges that continue to confront us no matter what our practice type and setting.

I could not ask for a more accomplished and versatile co-Editor than Tyler Hughes. As a general surgeon practicing in the truly rural setting of McPherson, Kan., since 1995, he became an articulate spokesman for rural surgeons across the country during his tenure on the ACS Board of Governors as Kansas’ at-large member. As the crisis in access to general surgical care for rural Americans became increasingly evident, Tyler was asked to speak to the Board of Regents in February 2012, and the first new Advisory Council in 50 years was formed: the Advisory Council for Rural Surgery (ACRS), of which Tyler was named the first Chair. In 4 short years, the ACRS has become a force to promote better communication among rural surgeons and to call attention to the needs of them and their patients.

Tyler’s communication skills have also been put to great use in his role as Editor of the ACS Web Portal and as the inaugural Editor-in-Chief of the ACS Communities, an activity that has met with incredible success in promoting communication among the far-flung individual surgeons who constitute the ACS membership. Along the way, he has also served as an Associate Editor of “Selected Readings in General Surgery” and a member of the steering committee of Evidence Based Reviews in Surgery.

He currently serves as a Director of the American Board of Surgery (ABS). He is therefore familiar with all of the issues of surgical training, certification, and re-certification. He is similarly well versed in the complexities surrounding the implementation of Maintenance of Certification, which remains a “work in progress” that his experience as a practicing, small-town general surgeon will certainly inform.

Tyler has distinguished himself in other leadership positions throughout his more than 30 years as a surgeon, including as President of his 600-member physician group when he initially practiced in Dallas. He has been a Fellow in the ACS for his entire surgical career and holds a deep respect, affection, and loyalty to the College. He possesses mainstream values, true to his upbringing and his long residence in America’s heartland; yet, he understands and respects the divergent views of surgeons across our country. He is also not afraid to tackle challenging problems, which is why I know that our tenure as co-Editors of ACS Surgery News is not likely to become boring.

I feel honored to join Tyler G. Hughes as co-Editor of the ACS Surgery News and I am excited to work with its Managing Editor, Therese Borden, to bring to its readers breaking information on a broad range of subjects of interest and importance to practicing surgeons. Although we have a great challenge to fill the giant shoes of our immediate predecessor, Layton “Bing” Rikkers, we will do our best to address the vexing clinical, economic, social, and administrative challenges that continue to confront us no matter what our practice type and setting.

I could not ask for a more accomplished and versatile co-Editor than Tyler Hughes. As a general surgeon practicing in the truly rural setting of McPherson, Kan., since 1995, he became an articulate spokesman for rural surgeons across the country during his tenure on the ACS Board of Governors as Kansas’ at-large member. As the crisis in access to general surgical care for rural Americans became increasingly evident, Tyler was asked to speak to the Board of Regents in February 2012, and the first new Advisory Council in 50 years was formed: the Advisory Council for Rural Surgery (ACRS), of which Tyler was named the first Chair. In 4 short years, the ACRS has become a force to promote better communication among rural surgeons and to call attention to the needs of them and their patients.

Tyler’s communication skills have also been put to great use in his role as Editor of the ACS Web Portal and as the inaugural Editor-in-Chief of the ACS Communities, an activity that has met with incredible success in promoting communication among the far-flung individual surgeons who constitute the ACS membership. Along the way, he has also served as an Associate Editor of “Selected Readings in General Surgery” and a member of the steering committee of Evidence Based Reviews in Surgery.

He currently serves as a Director of the American Board of Surgery (ABS). He is therefore familiar with all of the issues of surgical training, certification, and re-certification. He is similarly well versed in the complexities surrounding the implementation of Maintenance of Certification, which remains a “work in progress” that his experience as a practicing, small-town general surgeon will certainly inform.

Tyler has distinguished himself in other leadership positions throughout his more than 30 years as a surgeon, including as President of his 600-member physician group when he initially practiced in Dallas. He has been a Fellow in the ACS for his entire surgical career and holds a deep respect, affection, and loyalty to the College. He possesses mainstream values, true to his upbringing and his long residence in America’s heartland; yet, he understands and respects the divergent views of surgeons across our country. He is also not afraid to tackle challenging problems, which is why I know that our tenure as co-Editors of ACS Surgery News is not likely to become boring.

I feel honored to join Tyler G. Hughes as co-Editor of the ACS Surgery News and I am excited to work with its Managing Editor, Therese Borden, to bring to its readers breaking information on a broad range of subjects of interest and importance to practicing surgeons. Although we have a great challenge to fill the giant shoes of our immediate predecessor, Layton “Bing” Rikkers, we will do our best to address the vexing clinical, economic, social, and administrative challenges that continue to confront us no matter what our practice type and setting.

I could not ask for a more accomplished and versatile co-Editor than Tyler Hughes. As a general surgeon practicing in the truly rural setting of McPherson, Kan., since 1995, he became an articulate spokesman for rural surgeons across the country during his tenure on the ACS Board of Governors as Kansas’ at-large member. As the crisis in access to general surgical care for rural Americans became increasingly evident, Tyler was asked to speak to the Board of Regents in February 2012, and the first new Advisory Council in 50 years was formed: the Advisory Council for Rural Surgery (ACRS), of which Tyler was named the first Chair. In 4 short years, the ACRS has become a force to promote better communication among rural surgeons and to call attention to the needs of them and their patients.

Tyler’s communication skills have also been put to great use in his role as Editor of the ACS Web Portal and as the inaugural Editor-in-Chief of the ACS Communities, an activity that has met with incredible success in promoting communication among the far-flung individual surgeons who constitute the ACS membership. Along the way, he has also served as an Associate Editor of “Selected Readings in General Surgery” and a member of the steering committee of Evidence Based Reviews in Surgery.

He currently serves as a Director of the American Board of Surgery (ABS). He is therefore familiar with all of the issues of surgical training, certification, and re-certification. He is similarly well versed in the complexities surrounding the implementation of Maintenance of Certification, which remains a “work in progress” that his experience as a practicing, small-town general surgeon will certainly inform.

Tyler has distinguished himself in other leadership positions throughout his more than 30 years as a surgeon, including as President of his 600-member physician group when he initially practiced in Dallas. He has been a Fellow in the ACS for his entire surgical career and holds a deep respect, affection, and loyalty to the College. He possesses mainstream values, true to his upbringing and his long residence in America’s heartland; yet, he understands and respects the divergent views of surgeons across our country. He is also not afraid to tackle challenging problems, which is why I know that our tenure as co-Editors of ACS Surgery News is not likely to become boring.

Introducing Dr. Karen Deveney

As Layton “Bing” Rikkers leaves his post as Editor of ACS Surgery News, it has fallen to Karen Deveney and me to shepherd the paper forward as co-Editors. Dr. Rikkers felt that a combination approach of an academic surgeon and a community surgeon would bring balance to ACS Surgery News that would be representative of the nature of the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

In Karen Deveney we have an accomplished academic surgeon who has wide ranging interests in and out of surgery. Karen was raised in rural Oregon, went to Stanford for undergraduate education, and did her medical school and residency at University of California, San Francisco. Among her cohort in those times of training and her early academic career were Donald Trunkey, George Sheldon, and Brent Eastman, all of whom, like Karen, went on to have a major impact in the world of surgery.

After a stint in the military serving in Germany with her surgeon husband Cliff, Karen eventually landed at Oregon Health and Science University where she went on to serve as Program Director for 20 years at one of the best general surgery training programs in the country. She served as Second Vice-President of the ACS and is the immediate past-President of the Pacific Coast Surgical Association.

Her CV reflects varied academic interests and activities. So, Karen’s contributions to academic surgery are outstanding. But in Karen we also get a person who is alive to the needs of the population beyond the walls of her major medical center. Karen has been a leader in the march to save surgical access for rural populations. She is a founding member of the ACS Advisory Council for Rural Surgery, serving as the Education Pillar Chair of that Council. In her own institution, Karen is a pioneer in developing a model rural surgery track for general surgery residents – first in Grants Pass, Ore. and then in Coos Bay, Ore.

She has been a hardworking general and colorectal surgeon for over 30 years. And, like almost all dedicated surgical educators, she has taken call – enduring the long call schedule of her residents throughout her career.

Karen and I hope to make a good team in this new effort. We are different in many ways, but very much the same in others. We plan a synergy that will unflinchingly recognize the challenges in surgery and facilitate positive discussion and reporting of the solutions for those challenges. Among those challenges are the changing economic structure of surgery, the facilitation of useful quality efforts, and most importantly, the rapid dissemination of significant clinical and scientific information vital to surgeons everywhere.

Dr. Hughes is an ACS Fellow with the department of general surgery, McPherson Hospital, McPherson, Kan., and is the Editor in Chief of ACS Communities. He is also Associate Editor for ACS Surgery News.

As Layton “Bing” Rikkers leaves his post as Editor of ACS Surgery News, it has fallen to Karen Deveney and me to shepherd the paper forward as co-Editors. Dr. Rikkers felt that a combination approach of an academic surgeon and a community surgeon would bring balance to ACS Surgery News that would be representative of the nature of the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

In Karen Deveney we have an accomplished academic surgeon who has wide ranging interests in and out of surgery. Karen was raised in rural Oregon, went to Stanford for undergraduate education, and did her medical school and residency at University of California, San Francisco. Among her cohort in those times of training and her early academic career were Donald Trunkey, George Sheldon, and Brent Eastman, all of whom, like Karen, went on to have a major impact in the world of surgery.

After a stint in the military serving in Germany with her surgeon husband Cliff, Karen eventually landed at Oregon Health and Science University where she went on to serve as Program Director for 20 years at one of the best general surgery training programs in the country. She served as Second Vice-President of the ACS and is the immediate past-President of the Pacific Coast Surgical Association.

Her CV reflects varied academic interests and activities. So, Karen’s contributions to academic surgery are outstanding. But in Karen we also get a person who is alive to the needs of the population beyond the walls of her major medical center. Karen has been a leader in the march to save surgical access for rural populations. She is a founding member of the ACS Advisory Council for Rural Surgery, serving as the Education Pillar Chair of that Council. In her own institution, Karen is a pioneer in developing a model rural surgery track for general surgery residents – first in Grants Pass, Ore. and then in Coos Bay, Ore.

She has been a hardworking general and colorectal surgeon for over 30 years. And, like almost all dedicated surgical educators, she has taken call – enduring the long call schedule of her residents throughout her career.

Karen and I hope to make a good team in this new effort. We are different in many ways, but very much the same in others. We plan a synergy that will unflinchingly recognize the challenges in surgery and facilitate positive discussion and reporting of the solutions for those challenges. Among those challenges are the changing economic structure of surgery, the facilitation of useful quality efforts, and most importantly, the rapid dissemination of significant clinical and scientific information vital to surgeons everywhere.

Dr. Hughes is an ACS Fellow with the department of general surgery, McPherson Hospital, McPherson, Kan., and is the Editor in Chief of ACS Communities. He is also Associate Editor for ACS Surgery News.

As Layton “Bing” Rikkers leaves his post as Editor of ACS Surgery News, it has fallen to Karen Deveney and me to shepherd the paper forward as co-Editors. Dr. Rikkers felt that a combination approach of an academic surgeon and a community surgeon would bring balance to ACS Surgery News that would be representative of the nature of the American College of Surgeons (ACS).

In Karen Deveney we have an accomplished academic surgeon who has wide ranging interests in and out of surgery. Karen was raised in rural Oregon, went to Stanford for undergraduate education, and did her medical school and residency at University of California, San Francisco. Among her cohort in those times of training and her early academic career were Donald Trunkey, George Sheldon, and Brent Eastman, all of whom, like Karen, went on to have a major impact in the world of surgery.

After a stint in the military serving in Germany with her surgeon husband Cliff, Karen eventually landed at Oregon Health and Science University where she went on to serve as Program Director for 20 years at one of the best general surgery training programs in the country. She served as Second Vice-President of the ACS and is the immediate past-President of the Pacific Coast Surgical Association.

Her CV reflects varied academic interests and activities. So, Karen’s contributions to academic surgery are outstanding. But in Karen we also get a person who is alive to the needs of the population beyond the walls of her major medical center. Karen has been a leader in the march to save surgical access for rural populations. She is a founding member of the ACS Advisory Council for Rural Surgery, serving as the Education Pillar Chair of that Council. In her own institution, Karen is a pioneer in developing a model rural surgery track for general surgery residents – first in Grants Pass, Ore. and then in Coos Bay, Ore.

She has been a hardworking general and colorectal surgeon for over 30 years. And, like almost all dedicated surgical educators, she has taken call – enduring the long call schedule of her residents throughout her career.

Karen and I hope to make a good team in this new effort. We are different in many ways, but very much the same in others. We plan a synergy that will unflinchingly recognize the challenges in surgery and facilitate positive discussion and reporting of the solutions for those challenges. Among those challenges are the changing economic structure of surgery, the facilitation of useful quality efforts, and most importantly, the rapid dissemination of significant clinical and scientific information vital to surgeons everywhere.

Dr. Hughes is an ACS Fellow with the department of general surgery, McPherson Hospital, McPherson, Kan., and is the Editor in Chief of ACS Communities. He is also Associate Editor for ACS Surgery News.

Protecting the newborn brain—the final frontier in obstetric and neonatal care

During the past 40 years neonatologists have discovered new treatments to improve pulmonary and cardiovascular care of preterm newborns, resulting in a dramatic reduction in newborn mortality and childhood morbidity. Important advances include glucocorticoid administration to mothers at risk for preterm birth, surfactant and nitric oxide administration to the newborn, kangaroo (or skin-to-skin) care, continuous positive airway pressure, and high-frequency ventilation.1 In 1960, only 5% of 1,000-g newborns survived. In 2000, 95% of 1,000-g newborns survive.1

The successes in pulmonary and cardiovascular care have revealed a new frontier in neonatal care: the prevention of long-term neurologic disability by the early treatment of newborn encephalpathy with therapeutic hypothermia. This novel undertaking is an important one; approximately 1 in 300 newborns are diagnosed with encephalopathy.2

Until recently there were no proven treatments for newborns with encephalopathy. However, therapeutic hypothermia now has been proven to be an effective intervention for the treatment of moderate and severe encephalopathy,3,4 and its use is expanding to include mild cases.

This increased use can lead to more complex situations arising for obstetricians, for when a neonatologist decides to initiate therapeutic hypothermia of a newborn the parents may wonder if the obstetrician’s management of labor and delivery was suboptimal, contributing to their baby’s brain injury.

Therapeutic hypothermia: The basics

First, we need to define therapeutic hypothermia. Both head hypothermia and whole-body hypothermia are effective techniques for the treatment of newborn encephalopathy.3,4 Most centers use whole-body (FIGURE) rather than head, hypothermia because it facilitates access to the head for placement of electroencephalogram (EEG) sensors.

The key principles of therapeutic hypothermia include5,6:

- Initiate hypothermia within 6 hours of birth.

- Cool the newborn to a core temperature of 33.5° to 34.5°C (92.3° to 94.1°F). Some centers focus on achieving consistent core temperatures of 33.5°C (92.3°F).

- Monitor core temperature every 5 to 15 minutes.

- Cool the newborn for 72 hours.

- Obtain head ultrasonography to detect intracranial hemorrhage.

- Initiate continuous or intermittent EEG monitoring.

- Treat seizures with phenobarbital, lorazepam, or phenytoin.

- Obtain blood cultures, a complete blood count, blood gas concentrations, alactate coagulation profile, and liver function tests.

- Sedate the newborn, if necessary.

- Minimize oral feedings during the initial phase of hypothermia.

- Obtain sequential magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies to assess brain structure and function.

- For all newborns with suspected encephalopathy, the placenta should be sent to pathology for histologic study.7

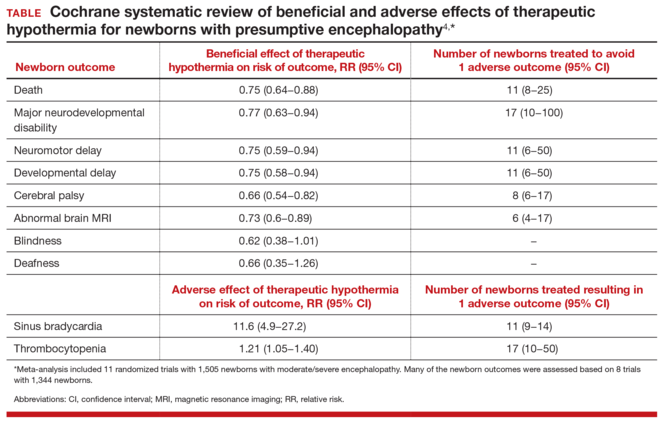

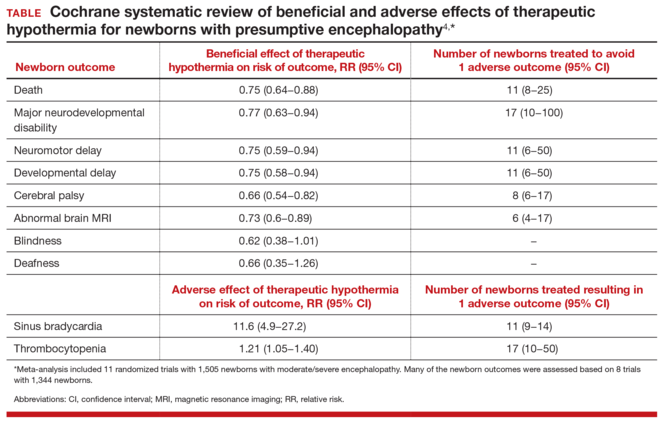

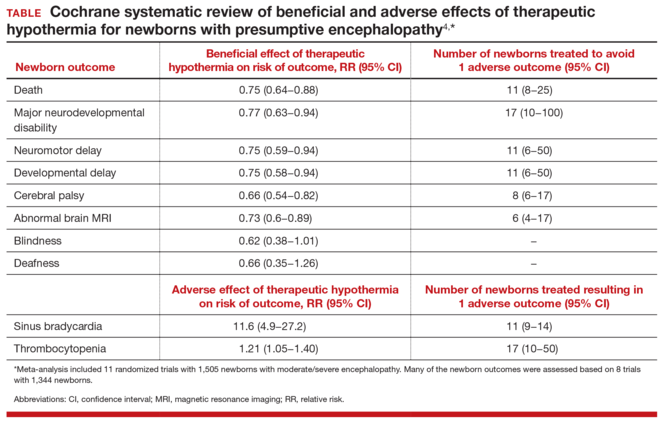

The data on therapy effectivenessTwo recent meta-analyses independently reported that therapeutic hypothermia reduced the risk of newborn death and major neurodevelopmental disability.3,4 The Cochrane meta-analysis reported that the therapy reduced the risk of neuromotor delay, developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and abnormal MRI results (TABLE).4 The study authors also reported that therapeutic hypothermia reduced the risk of blindness and deafness, although these effects did not reach statistical significance.4 Therapeutic hypothermia did increase the risk of newborn sinus bradycardia and thrombocytopenia.3,4 Compared with usual care, the therapy increased the average survival rate with a normal neurologic outcome at 18 months from 23% to 40%.3 It should be noted that even with therapeutic hypothermia treatment, many newborns with moderate to severe encephalopathy have long-term neurologic disabilities.

Indications for therapeutic hypothermia are expandingIn the initial clinical trials of therapeutic hypothermia, newborns with moderate to severe encephalopathy were enrolled. Typical inclusion criteria were: gestational age ≥35 or 36 weeks, initiation of therapeutic hypothermia within 6 hours of birth, pH ≤7.0 or base deficit of ≥16 mEq/L, 10-minute Apgar score <5 or ongoing resuscitation for 10 minutes, and moderate to severe encephalopathy on clinical examination.3,4 Typical exclusion criteria were: intrauterine growth restriction with birth weight less than 1,750 g, severe congenital anomalies or severe genetic or metabolic syndromes, major intracranial hemorrhage, sepsis, or persistent coagulopathy.

Given the success of therapeutic hypothermia for moderate to severe newborn encephalopathy, many neonatologists are expanding the indications for treatment. In some centers current indications for initiation of hypothermia include the following:

- gestational age ≥34 weeks

- suspicion of encephalopathy or a seizure event

- any obstetric sentinel event (including a bradycardia, umbilical cord prolapse, uterine rupture, placental abruption, Apgar score ≤5 at 10 minutes, pH ≤7.1 or base deficit of ≥10 mEq/L or Category III tracing, or fetal tachycardia with recurrent decelerations or fetal heart rate with minimal variability and recurrent decelerations).

Suspicion for encephalopathy might be triggered by any of a large number of newborn behaviors: lethargy, decreased activity, hypotonia, weak suck or incomplete Moro reflexes, constricted pupils, bradycardia, periodic breathing or apnea, hyperalertness, or irritability.8

Coordinate neonatology and obstetric communication with the familyGiven the expanding indications for therapeutic hypothermia, an increasing number of newborns will receive this treatment. This scenario makes enhanced communication vital. Consider this situation:

CASE Baby rushed for therapeutic hypothermia upon birthA baby is born limp and blue without a cry. Her hypotonia raises a concern for encephalopathy, and she is whisked off to the neonatal intensive care unit for 72 hours of therapeutic hypothermia. Stunned, the parents begin to wonder, “Will our baby be O.K.?” and “What went wrong?”

When neonatologists recommend therapeutic hypothermia for the newborn with presumptive encephalopathy, they may explain the situation to the parents with words such as brain injury, encephalopathy, hypoxia, and ischemia. Intrapartum events such as a Category II or III fetal heart rate tracing, operative vaginal delivery, or maternal sepsis or abruption might be mentioned as contributing factors. A consulting neurologist may mention injury of the cerebral cortex, subcortical white matter, or lateral thalami. The neonatologists and neurologists might not mention that less than 50% of cases of newborn encephalopathy are thought to be due to the management of labor.2

The obstetrician, as stunned by the events as the parents, may be at a loss about how to communicate effectively with their patient about the newborn’s encephalopathy. Obstetricians can help assure the parents of their continued involvement in the care and reinforce that the hospital’s neonatologists are superb clinicians who will do their best for the baby.

Challenges exist to effective communication. It is often difficult to optimally coordinate and align the communications of the neonatologists, neurologist, nurses, and obstetrician with the family. Communication with the family can be uncoordinated because interactions occur between the family and multiple specialists with unique perspectives and vocabularies. These conversations occur in sequence, separated in time and place. The communication between family and neonatologists typically occurs in the neonatal intensive care unit. Interactions between obstetrician and mother typically occur in the postpartum unit. The neonatologists and obstetricians are assigned to the hospital in rotating coverage shifts, increasing the number of hand-offs and physicians involved in the hospital care of the mother and newborn dyad.

A joint family meeting with the neonatologists, obstetrician, and family early in the course of newborn care might be an optimal approach to coordinating communication with the parents. Conflicting obligations certainly may make a joint meeting difficult to arrange, however.

Reducing the risk of permanent injury to the central and peripheral nervous system of the newborn is the goal of all obstetricians and neonatologists. Many authorities believe that therapeutic hypothermia can reduce the risk of death and major neurodevelopmental disorders in newborns with encephalopathy. Initial data are promising. If long-term follow-up studies prove that this therapy reduces neurologic disability, the treatment represents a major advance in maternal-child care. As we learn more about this novel, and potentially effective therapy, it should be on the minds of those involved with newborn care to involve the ObGyn in coordinated communication with the family and other medical staff.

- Philip AG. The evolution of neonatology. Pediatr Res. 2005;58(4):799−815.

- Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(6):329−338.

- Tagin MA, Woolcott CG, Vincer MJ, Whyte RK, Stinson DA. Hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(6):558−566.

- Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD003311.

- Papile LA, Baley JE, Benitz W, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1146−1150.

- Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al; Steering Group and TOBY Cooling Register participants. Treatment of asphyxiated newborns with moderate hypothermia in routine clinical practice: how cooling is managed in the UK outside a clinical trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(4):F260−F264.

- Mir IN, Johnson-Welch SF, Nelson DB, Brown LS, Rosenfeld CR, Chalak LF. Placental pathology is associated with severity of neonatal encephalopathy and adverse developmental outcomes following hypothermia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):849.e1−e7.

- Thompson CM, Puterman AS, Linley LL, et al. The value of a scoring system for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86(7):757−761.

During the past 40 years neonatologists have discovered new treatments to improve pulmonary and cardiovascular care of preterm newborns, resulting in a dramatic reduction in newborn mortality and childhood morbidity. Important advances include glucocorticoid administration to mothers at risk for preterm birth, surfactant and nitric oxide administration to the newborn, kangaroo (or skin-to-skin) care, continuous positive airway pressure, and high-frequency ventilation.1 In 1960, only 5% of 1,000-g newborns survived. In 2000, 95% of 1,000-g newborns survive.1

The successes in pulmonary and cardiovascular care have revealed a new frontier in neonatal care: the prevention of long-term neurologic disability by the early treatment of newborn encephalpathy with therapeutic hypothermia. This novel undertaking is an important one; approximately 1 in 300 newborns are diagnosed with encephalopathy.2

Until recently there were no proven treatments for newborns with encephalopathy. However, therapeutic hypothermia now has been proven to be an effective intervention for the treatment of moderate and severe encephalopathy,3,4 and its use is expanding to include mild cases.

This increased use can lead to more complex situations arising for obstetricians, for when a neonatologist decides to initiate therapeutic hypothermia of a newborn the parents may wonder if the obstetrician’s management of labor and delivery was suboptimal, contributing to their baby’s brain injury.

Therapeutic hypothermia: The basics

First, we need to define therapeutic hypothermia. Both head hypothermia and whole-body hypothermia are effective techniques for the treatment of newborn encephalopathy.3,4 Most centers use whole-body (FIGURE) rather than head, hypothermia because it facilitates access to the head for placement of electroencephalogram (EEG) sensors.

The key principles of therapeutic hypothermia include5,6:

- Initiate hypothermia within 6 hours of birth.

- Cool the newborn to a core temperature of 33.5° to 34.5°C (92.3° to 94.1°F). Some centers focus on achieving consistent core temperatures of 33.5°C (92.3°F).

- Monitor core temperature every 5 to 15 minutes.

- Cool the newborn for 72 hours.

- Obtain head ultrasonography to detect intracranial hemorrhage.

- Initiate continuous or intermittent EEG monitoring.

- Treat seizures with phenobarbital, lorazepam, or phenytoin.

- Obtain blood cultures, a complete blood count, blood gas concentrations, alactate coagulation profile, and liver function tests.

- Sedate the newborn, if necessary.

- Minimize oral feedings during the initial phase of hypothermia.

- Obtain sequential magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies to assess brain structure and function.

- For all newborns with suspected encephalopathy, the placenta should be sent to pathology for histologic study.7

The data on therapy effectivenessTwo recent meta-analyses independently reported that therapeutic hypothermia reduced the risk of newborn death and major neurodevelopmental disability.3,4 The Cochrane meta-analysis reported that the therapy reduced the risk of neuromotor delay, developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and abnormal MRI results (TABLE).4 The study authors also reported that therapeutic hypothermia reduced the risk of blindness and deafness, although these effects did not reach statistical significance.4 Therapeutic hypothermia did increase the risk of newborn sinus bradycardia and thrombocytopenia.3,4 Compared with usual care, the therapy increased the average survival rate with a normal neurologic outcome at 18 months from 23% to 40%.3 It should be noted that even with therapeutic hypothermia treatment, many newborns with moderate to severe encephalopathy have long-term neurologic disabilities.

Indications for therapeutic hypothermia are expandingIn the initial clinical trials of therapeutic hypothermia, newborns with moderate to severe encephalopathy were enrolled. Typical inclusion criteria were: gestational age ≥35 or 36 weeks, initiation of therapeutic hypothermia within 6 hours of birth, pH ≤7.0 or base deficit of ≥16 mEq/L, 10-minute Apgar score <5 or ongoing resuscitation for 10 minutes, and moderate to severe encephalopathy on clinical examination.3,4 Typical exclusion criteria were: intrauterine growth restriction with birth weight less than 1,750 g, severe congenital anomalies or severe genetic or metabolic syndromes, major intracranial hemorrhage, sepsis, or persistent coagulopathy.

Given the success of therapeutic hypothermia for moderate to severe newborn encephalopathy, many neonatologists are expanding the indications for treatment. In some centers current indications for initiation of hypothermia include the following:

- gestational age ≥34 weeks

- suspicion of encephalopathy or a seizure event

- any obstetric sentinel event (including a bradycardia, umbilical cord prolapse, uterine rupture, placental abruption, Apgar score ≤5 at 10 minutes, pH ≤7.1 or base deficit of ≥10 mEq/L or Category III tracing, or fetal tachycardia with recurrent decelerations or fetal heart rate with minimal variability and recurrent decelerations).

Suspicion for encephalopathy might be triggered by any of a large number of newborn behaviors: lethargy, decreased activity, hypotonia, weak suck or incomplete Moro reflexes, constricted pupils, bradycardia, periodic breathing or apnea, hyperalertness, or irritability.8

Coordinate neonatology and obstetric communication with the familyGiven the expanding indications for therapeutic hypothermia, an increasing number of newborns will receive this treatment. This scenario makes enhanced communication vital. Consider this situation:

CASE Baby rushed for therapeutic hypothermia upon birthA baby is born limp and blue without a cry. Her hypotonia raises a concern for encephalopathy, and she is whisked off to the neonatal intensive care unit for 72 hours of therapeutic hypothermia. Stunned, the parents begin to wonder, “Will our baby be O.K.?” and “What went wrong?”

When neonatologists recommend therapeutic hypothermia for the newborn with presumptive encephalopathy, they may explain the situation to the parents with words such as brain injury, encephalopathy, hypoxia, and ischemia. Intrapartum events such as a Category II or III fetal heart rate tracing, operative vaginal delivery, or maternal sepsis or abruption might be mentioned as contributing factors. A consulting neurologist may mention injury of the cerebral cortex, subcortical white matter, or lateral thalami. The neonatologists and neurologists might not mention that less than 50% of cases of newborn encephalopathy are thought to be due to the management of labor.2

The obstetrician, as stunned by the events as the parents, may be at a loss about how to communicate effectively with their patient about the newborn’s encephalopathy. Obstetricians can help assure the parents of their continued involvement in the care and reinforce that the hospital’s neonatologists are superb clinicians who will do their best for the baby.

Challenges exist to effective communication. It is often difficult to optimally coordinate and align the communications of the neonatologists, neurologist, nurses, and obstetrician with the family. Communication with the family can be uncoordinated because interactions occur between the family and multiple specialists with unique perspectives and vocabularies. These conversations occur in sequence, separated in time and place. The communication between family and neonatologists typically occurs in the neonatal intensive care unit. Interactions between obstetrician and mother typically occur in the postpartum unit. The neonatologists and obstetricians are assigned to the hospital in rotating coverage shifts, increasing the number of hand-offs and physicians involved in the hospital care of the mother and newborn dyad.

A joint family meeting with the neonatologists, obstetrician, and family early in the course of newborn care might be an optimal approach to coordinating communication with the parents. Conflicting obligations certainly may make a joint meeting difficult to arrange, however.

Reducing the risk of permanent injury to the central and peripheral nervous system of the newborn is the goal of all obstetricians and neonatologists. Many authorities believe that therapeutic hypothermia can reduce the risk of death and major neurodevelopmental disorders in newborns with encephalopathy. Initial data are promising. If long-term follow-up studies prove that this therapy reduces neurologic disability, the treatment represents a major advance in maternal-child care. As we learn more about this novel, and potentially effective therapy, it should be on the minds of those involved with newborn care to involve the ObGyn in coordinated communication with the family and other medical staff.

During the past 40 years neonatologists have discovered new treatments to improve pulmonary and cardiovascular care of preterm newborns, resulting in a dramatic reduction in newborn mortality and childhood morbidity. Important advances include glucocorticoid administration to mothers at risk for preterm birth, surfactant and nitric oxide administration to the newborn, kangaroo (or skin-to-skin) care, continuous positive airway pressure, and high-frequency ventilation.1 In 1960, only 5% of 1,000-g newborns survived. In 2000, 95% of 1,000-g newborns survive.1

The successes in pulmonary and cardiovascular care have revealed a new frontier in neonatal care: the prevention of long-term neurologic disability by the early treatment of newborn encephalpathy with therapeutic hypothermia. This novel undertaking is an important one; approximately 1 in 300 newborns are diagnosed with encephalopathy.2

Until recently there were no proven treatments for newborns with encephalopathy. However, therapeutic hypothermia now has been proven to be an effective intervention for the treatment of moderate and severe encephalopathy,3,4 and its use is expanding to include mild cases.

This increased use can lead to more complex situations arising for obstetricians, for when a neonatologist decides to initiate therapeutic hypothermia of a newborn the parents may wonder if the obstetrician’s management of labor and delivery was suboptimal, contributing to their baby’s brain injury.

Therapeutic hypothermia: The basics

First, we need to define therapeutic hypothermia. Both head hypothermia and whole-body hypothermia are effective techniques for the treatment of newborn encephalopathy.3,4 Most centers use whole-body (FIGURE) rather than head, hypothermia because it facilitates access to the head for placement of electroencephalogram (EEG) sensors.

The key principles of therapeutic hypothermia include5,6:

- Initiate hypothermia within 6 hours of birth.

- Cool the newborn to a core temperature of 33.5° to 34.5°C (92.3° to 94.1°F). Some centers focus on achieving consistent core temperatures of 33.5°C (92.3°F).

- Monitor core temperature every 5 to 15 minutes.

- Cool the newborn for 72 hours.

- Obtain head ultrasonography to detect intracranial hemorrhage.

- Initiate continuous or intermittent EEG monitoring.

- Treat seizures with phenobarbital, lorazepam, or phenytoin.

- Obtain blood cultures, a complete blood count, blood gas concentrations, alactate coagulation profile, and liver function tests.

- Sedate the newborn, if necessary.

- Minimize oral feedings during the initial phase of hypothermia.

- Obtain sequential magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies to assess brain structure and function.

- For all newborns with suspected encephalopathy, the placenta should be sent to pathology for histologic study.7

The data on therapy effectivenessTwo recent meta-analyses independently reported that therapeutic hypothermia reduced the risk of newborn death and major neurodevelopmental disability.3,4 The Cochrane meta-analysis reported that the therapy reduced the risk of neuromotor delay, developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and abnormal MRI results (TABLE).4 The study authors also reported that therapeutic hypothermia reduced the risk of blindness and deafness, although these effects did not reach statistical significance.4 Therapeutic hypothermia did increase the risk of newborn sinus bradycardia and thrombocytopenia.3,4 Compared with usual care, the therapy increased the average survival rate with a normal neurologic outcome at 18 months from 23% to 40%.3 It should be noted that even with therapeutic hypothermia treatment, many newborns with moderate to severe encephalopathy have long-term neurologic disabilities.

Indications for therapeutic hypothermia are expandingIn the initial clinical trials of therapeutic hypothermia, newborns with moderate to severe encephalopathy were enrolled. Typical inclusion criteria were: gestational age ≥35 or 36 weeks, initiation of therapeutic hypothermia within 6 hours of birth, pH ≤7.0 or base deficit of ≥16 mEq/L, 10-minute Apgar score <5 or ongoing resuscitation for 10 minutes, and moderate to severe encephalopathy on clinical examination.3,4 Typical exclusion criteria were: intrauterine growth restriction with birth weight less than 1,750 g, severe congenital anomalies or severe genetic or metabolic syndromes, major intracranial hemorrhage, sepsis, or persistent coagulopathy.

Given the success of therapeutic hypothermia for moderate to severe newborn encephalopathy, many neonatologists are expanding the indications for treatment. In some centers current indications for initiation of hypothermia include the following:

- gestational age ≥34 weeks

- suspicion of encephalopathy or a seizure event

- any obstetric sentinel event (including a bradycardia, umbilical cord prolapse, uterine rupture, placental abruption, Apgar score ≤5 at 10 minutes, pH ≤7.1 or base deficit of ≥10 mEq/L or Category III tracing, or fetal tachycardia with recurrent decelerations or fetal heart rate with minimal variability and recurrent decelerations).

Suspicion for encephalopathy might be triggered by any of a large number of newborn behaviors: lethargy, decreased activity, hypotonia, weak suck or incomplete Moro reflexes, constricted pupils, bradycardia, periodic breathing or apnea, hyperalertness, or irritability.8

Coordinate neonatology and obstetric communication with the familyGiven the expanding indications for therapeutic hypothermia, an increasing number of newborns will receive this treatment. This scenario makes enhanced communication vital. Consider this situation:

CASE Baby rushed for therapeutic hypothermia upon birthA baby is born limp and blue without a cry. Her hypotonia raises a concern for encephalopathy, and she is whisked off to the neonatal intensive care unit for 72 hours of therapeutic hypothermia. Stunned, the parents begin to wonder, “Will our baby be O.K.?” and “What went wrong?”

When neonatologists recommend therapeutic hypothermia for the newborn with presumptive encephalopathy, they may explain the situation to the parents with words such as brain injury, encephalopathy, hypoxia, and ischemia. Intrapartum events such as a Category II or III fetal heart rate tracing, operative vaginal delivery, or maternal sepsis or abruption might be mentioned as contributing factors. A consulting neurologist may mention injury of the cerebral cortex, subcortical white matter, or lateral thalami. The neonatologists and neurologists might not mention that less than 50% of cases of newborn encephalopathy are thought to be due to the management of labor.2

The obstetrician, as stunned by the events as the parents, may be at a loss about how to communicate effectively with their patient about the newborn’s encephalopathy. Obstetricians can help assure the parents of their continued involvement in the care and reinforce that the hospital’s neonatologists are superb clinicians who will do their best for the baby.

Challenges exist to effective communication. It is often difficult to optimally coordinate and align the communications of the neonatologists, neurologist, nurses, and obstetrician with the family. Communication with the family can be uncoordinated because interactions occur between the family and multiple specialists with unique perspectives and vocabularies. These conversations occur in sequence, separated in time and place. The communication between family and neonatologists typically occurs in the neonatal intensive care unit. Interactions between obstetrician and mother typically occur in the postpartum unit. The neonatologists and obstetricians are assigned to the hospital in rotating coverage shifts, increasing the number of hand-offs and physicians involved in the hospital care of the mother and newborn dyad.

A joint family meeting with the neonatologists, obstetrician, and family early in the course of newborn care might be an optimal approach to coordinating communication with the parents. Conflicting obligations certainly may make a joint meeting difficult to arrange, however.

Reducing the risk of permanent injury to the central and peripheral nervous system of the newborn is the goal of all obstetricians and neonatologists. Many authorities believe that therapeutic hypothermia can reduce the risk of death and major neurodevelopmental disorders in newborns with encephalopathy. Initial data are promising. If long-term follow-up studies prove that this therapy reduces neurologic disability, the treatment represents a major advance in maternal-child care. As we learn more about this novel, and potentially effective therapy, it should be on the minds of those involved with newborn care to involve the ObGyn in coordinated communication with the family and other medical staff.

- Philip AG. The evolution of neonatology. Pediatr Res. 2005;58(4):799−815.

- Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(6):329−338.

- Tagin MA, Woolcott CG, Vincer MJ, Whyte RK, Stinson DA. Hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(6):558−566.

- Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD003311.

- Papile LA, Baley JE, Benitz W, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1146−1150.

- Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al; Steering Group and TOBY Cooling Register participants. Treatment of asphyxiated newborns with moderate hypothermia in routine clinical practice: how cooling is managed in the UK outside a clinical trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(4):F260−F264.

- Mir IN, Johnson-Welch SF, Nelson DB, Brown LS, Rosenfeld CR, Chalak LF. Placental pathology is associated with severity of neonatal encephalopathy and adverse developmental outcomes following hypothermia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):849.e1−e7.

- Thompson CM, Puterman AS, Linley LL, et al. The value of a scoring system for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86(7):757−761.

- Philip AG. The evolution of neonatology. Pediatr Res. 2005;58(4):799−815.

- Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(6):329−338.

- Tagin MA, Woolcott CG, Vincer MJ, Whyte RK, Stinson DA. Hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(6):558−566.

- Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD003311.

- Papile LA, Baley JE, Benitz W, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1146−1150.

- Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al; Steering Group and TOBY Cooling Register participants. Treatment of asphyxiated newborns with moderate hypothermia in routine clinical practice: how cooling is managed in the UK outside a clinical trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(4):F260−F264.

- Mir IN, Johnson-Welch SF, Nelson DB, Brown LS, Rosenfeld CR, Chalak LF. Placental pathology is associated with severity of neonatal encephalopathy and adverse developmental outcomes following hypothermia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(6):849.e1−e7.

- Thompson CM, Puterman AS, Linley LL, et al. The value of a scoring system for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86(7):757−761.

Trust the thyroid thermostat