User login

I want you to do my job

It is never easy to replace a legend. The Vascular Specialist that Russell Samson has left behind does not require saving. There are, however, problems ahead for all vascular surgeons, and my hope is to use this forum to unite us. Vascular surgery is a small specialty in an existential crisis. There are just over 3,000 of us in the United States. Think of Vascular Specialist as your hometown newspaper. Instead of high school sports and bake sales we will cover scientific meetings, clinical trials, and relevant legislation. And maybe the occasional swap meet.

Different points of view are going to be an essential part of this process. Russell Samson represented the posh, privileged world of private practice while I come from the rough and tumble streets of academia (just checking to see if he is still reading). My hope is to bring more. More Tips and Tricks, more Point/Counterpoint, more Letters to the Editor, more input from you.

How can you get involved? If you read something and have a response, send it to me. Volunteer to write up a technical tip or provide a medical debate. Have an idea for a guest editorial? Let me know, preferably before you write it. If it is good I will likely publish it. If not, well we can still be friends. Keep in mind, unlike book publishing, we work on strict deadlines. (To the three people I owe book chapters: Soon, I promise!) We will also be starting a vascular news section for brief committee updates, course registration openings, and relevant policy changes.

Vascular Specialist is now open for submissions. Contact us at [email protected].

It is never easy to replace a legend. The Vascular Specialist that Russell Samson has left behind does not require saving. There are, however, problems ahead for all vascular surgeons, and my hope is to use this forum to unite us. Vascular surgery is a small specialty in an existential crisis. There are just over 3,000 of us in the United States. Think of Vascular Specialist as your hometown newspaper. Instead of high school sports and bake sales we will cover scientific meetings, clinical trials, and relevant legislation. And maybe the occasional swap meet.

Different points of view are going to be an essential part of this process. Russell Samson represented the posh, privileged world of private practice while I come from the rough and tumble streets of academia (just checking to see if he is still reading). My hope is to bring more. More Tips and Tricks, more Point/Counterpoint, more Letters to the Editor, more input from you.

How can you get involved? If you read something and have a response, send it to me. Volunteer to write up a technical tip or provide a medical debate. Have an idea for a guest editorial? Let me know, preferably before you write it. If it is good I will likely publish it. If not, well we can still be friends. Keep in mind, unlike book publishing, we work on strict deadlines. (To the three people I owe book chapters: Soon, I promise!) We will also be starting a vascular news section for brief committee updates, course registration openings, and relevant policy changes.

Vascular Specialist is now open for submissions. Contact us at [email protected].

It is never easy to replace a legend. The Vascular Specialist that Russell Samson has left behind does not require saving. There are, however, problems ahead for all vascular surgeons, and my hope is to use this forum to unite us. Vascular surgery is a small specialty in an existential crisis. There are just over 3,000 of us in the United States. Think of Vascular Specialist as your hometown newspaper. Instead of high school sports and bake sales we will cover scientific meetings, clinical trials, and relevant legislation. And maybe the occasional swap meet.

Different points of view are going to be an essential part of this process. Russell Samson represented the posh, privileged world of private practice while I come from the rough and tumble streets of academia (just checking to see if he is still reading). My hope is to bring more. More Tips and Tricks, more Point/Counterpoint, more Letters to the Editor, more input from you.

How can you get involved? If you read something and have a response, send it to me. Volunteer to write up a technical tip or provide a medical debate. Have an idea for a guest editorial? Let me know, preferably before you write it. If it is good I will likely publish it. If not, well we can still be friends. Keep in mind, unlike book publishing, we work on strict deadlines. (To the three people I owe book chapters: Soon, I promise!) We will also be starting a vascular news section for brief committee updates, course registration openings, and relevant policy changes.

Vascular Specialist is now open for submissions. Contact us at [email protected].

FAST and RAPID: Acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis

Psychosis and stroke are arguably the most serious acute threats to the integrity of the brain, and consequently the mind. Both are unquestionably associated with a grave outcome the longer their treatment is delayed.1,2

While the management of stroke has been elevated to the highest emergent priority because of the progressively deleterious impact of thrombotic ischemia in one of the cerebral arteries, rapid intervention for acute psychosis has never been regarded as an urgent neurologic condition with severe threats to the brain’s structure and function.3,4 There is extensive literature on the serious consequences of a long duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), including treatment resistance, frequent re-hospitalizations, more negative symptoms, and greater disability.5

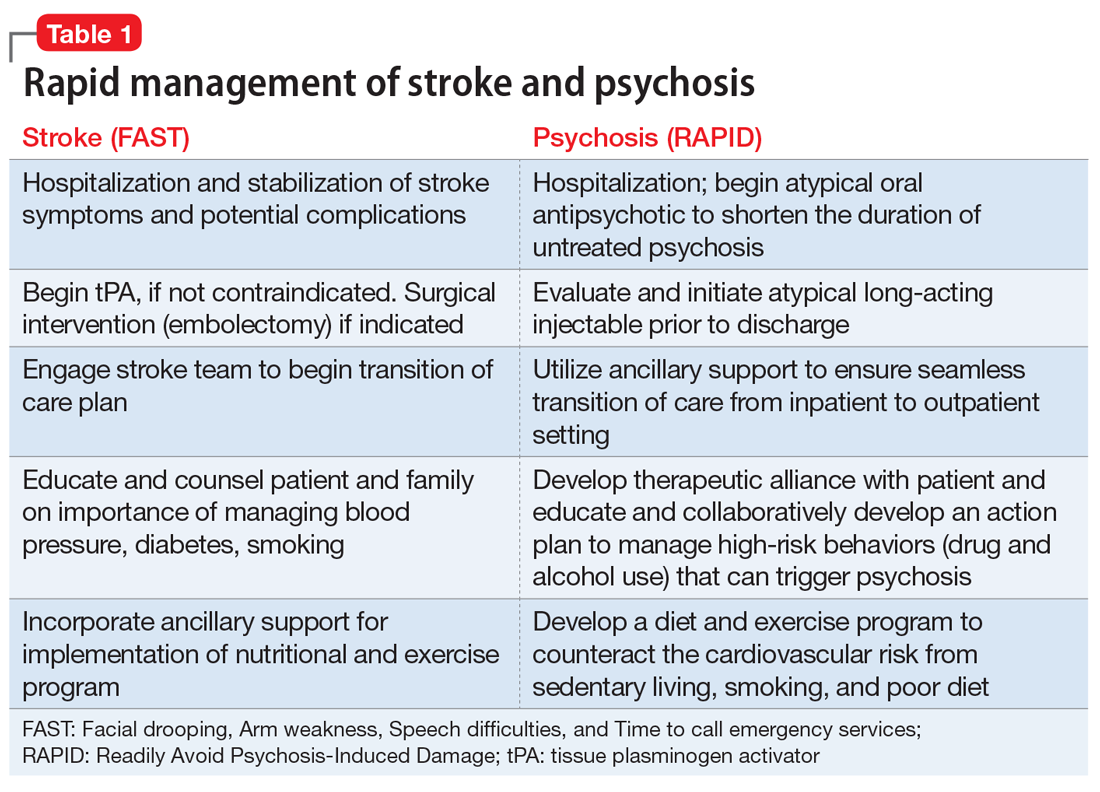

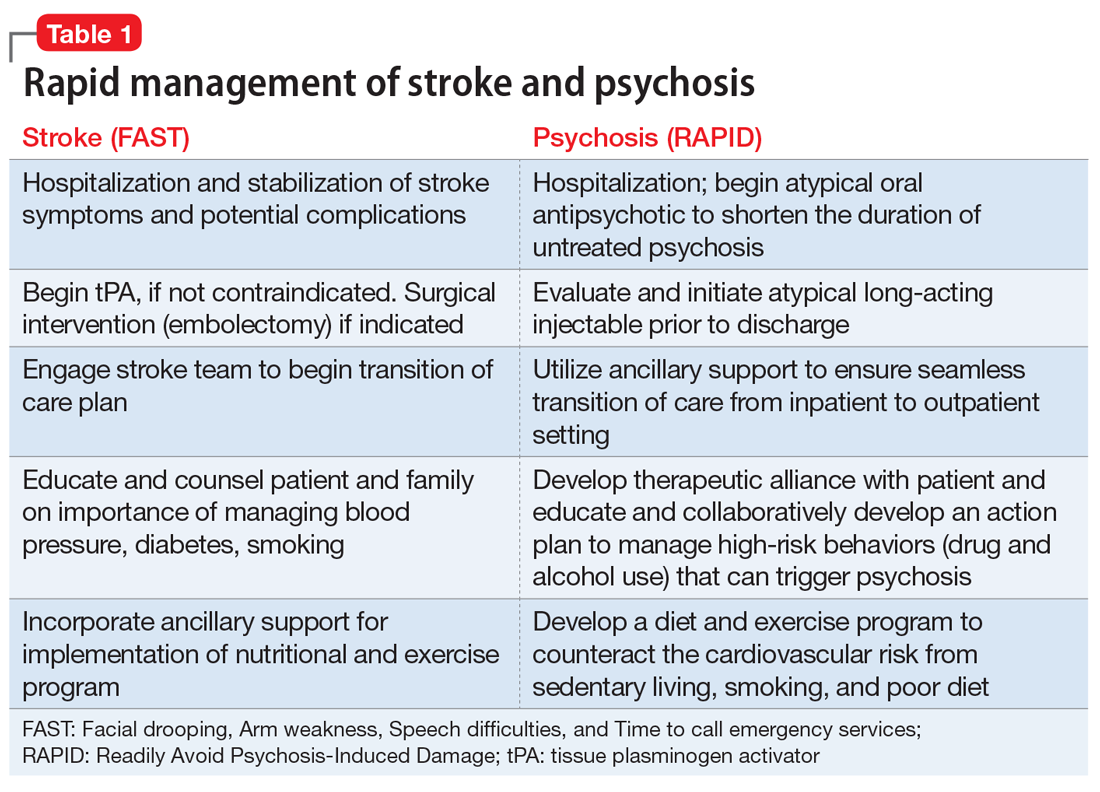

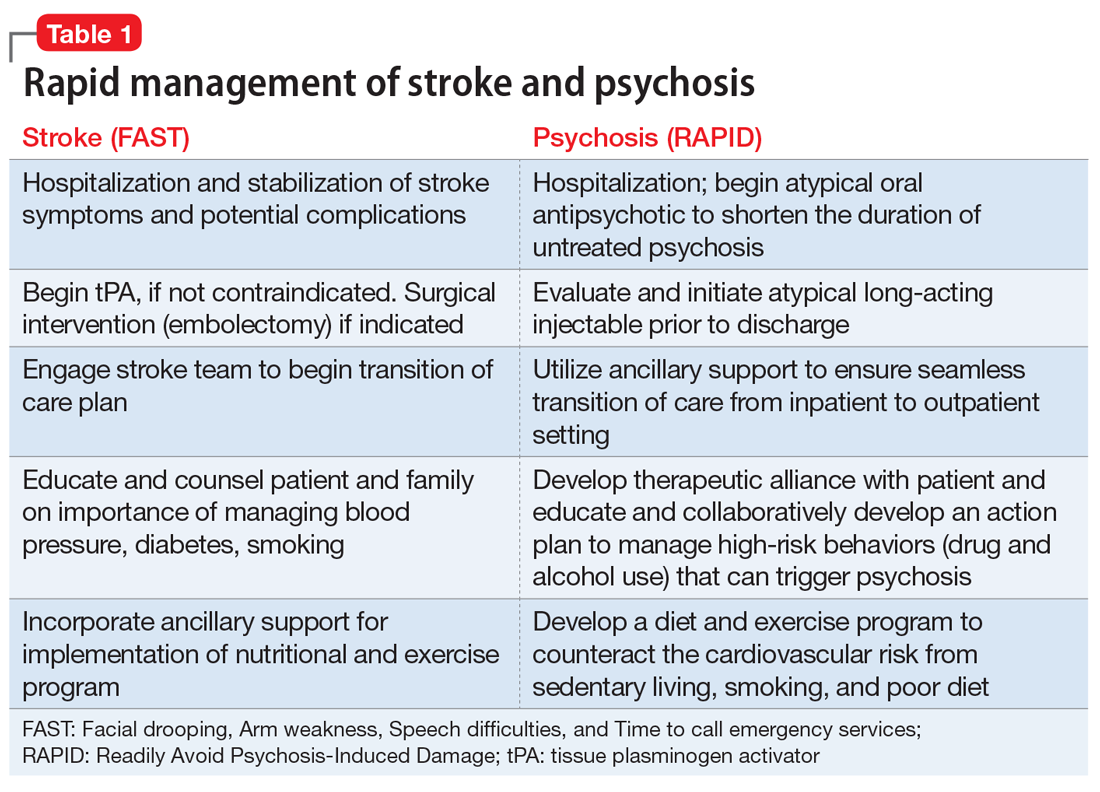

Physical paralysis from a stroke receives much more attention than “mental paralysis” of psychosis. Both must be rapidly treated, whether for the regional ischemia to brain tissue following a stroke or for the neurotoxicity of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress that lead to widespread neurodegeneration during psychosis.6 While an acronym for the quick recognition of a stroke (FAST: Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties, and Time to call emergency services) is well established, no acronym for the urgency to treat psychosis has been developed. We propose the acronym RAPID (Readily Avoid Psychosis-Induced Damage). The acronym RAPID would hopefully expedite the urgently needed pharmacotherapeutic and psychosocial intervention in psychosis to halt ongoing brain tissue loss.

It is ironic that the legal obstacles for immediate treatment, which do not exist for stroke, often delay administering antipsychotic medication to patients with anosognosia (a neurologic delusional belief that one is not ill, leading to refusal of treatment) for their psychosis and end up harming patients by prolonging their DUP until a court order is obtained to force brain-saving treatment. Frequent psychotic relapses due to nonadherence with medications are also a very common cause for prolonged DUP due to the inexplicable reluctance of some psychiatric practitioners to employ a long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) medication as soon as possible after the onset of psychosis to circumvent subsequent relapses due to the very high risk of poor adherence. Table 1 describes the optimal management of both stroke and acute psychosis once they are rapidly diagnosed, thanks to the FAST and RAPID reminders.

Tragically, the treatments of the mind have become falsely disengaged from the brain, the physical organ whose neurons, electrical impulses, synapses, and neurotransmitters generate the mind with its advanced human functions, such as self-awareness, will, thoughts, mood, speech, executive functions, memories, and social cognition. Recent editorials have challenged psychiatric practitioners to behave like cardiologists7 and oncologists8 by aggressively treating first-episode psychosis to prevent ongoing neurodegeneration due to recurrences. The brain loses 1% of its brain volume (~11 ml) after the first psychotic episode,8 which represents hundreds of millions of cells, billions of synapses, and substantial myelin. A second psychotic episode causes significant additional neuropil and white matter fiber damage and represents a different stage of schizophrenia9 with more severe tissue loss and disruption of neural pathways that trigger the process of treatment resistance and functional disability. Ensuring adherence with LAI antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first psychotic episode may allow many patients with schizophrenia to achieve a relapse-free remission and to return to their baseline functioning.10

In addition to significant brain tissue loss during psychotic episodes, mortality is also a very high risk following discharge from the first hospitalization for psychosis.11 LAI second-generation antipsychotic medications have been shown to be associated with lower mortality and neuroprotective effects,12 compared with oral or injectable first-generation antipsychotics. The highest mortality rate was reported to be associated with the lack of any antipsychotic medication,12 underscoring how untreated psychosis can be fatal.

Bottom line: Rapid treatment of stroke and psychosis is an absolute imperative for minimizing brain damage that respectively leads to physical or mental disability. The acronyms FAST and RAPID are essential reminders of the urgency needed to halt progressive neurodegeneration in those 2 devastating acute threats to the integrity of brain and mind. Intensive physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation must follow the acute treatment of stroke and psychosis, and the prevention of any recurrence is an absolute must. For psychosis, the use of a LAI second-generation antipsychotic before hospital discharge from a first episode of psychosis can be disease-modifying, with a more benign illness trajectory and outcome than the devastating deterioration that follows repetitive psychotic relapse, most often due to nonadherence with oral medications.

Continue to: Psychosis should be conceptualized as...

Psychosis should be conceptualized as a “stroke of the mind,” and it can be prevented in most patients with schizophrenia by adopting injectable antipsychotics as early after the onset of psychosis as possible. Yet, starting a LAI antipsychotic drug in first-episode psychosis before hospital discharge is rarely done, and the few patients who currently receive LAIs (10% of U.S. patients) generally receive them after multiple episodes and a protracted DUP. That’s like calling the fire department when much of the house has turned to ashes, instead of calling them when the first small flame is noticed. It makes so much sense, but the decades-old practice of postponing the use of LAIs continues to ruin the lives of young persons in the prime of life. By changing our practice habits to early use of LAIs, we have nothing to lose and our patients with psychosis may be spared a lifetime of suffering, poverty, stigma, incarceration, and functional disability. Wouldn’t we want to avoid that atrocious outcome for our own family members if they develop schizophrenia?

1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

2. Cechnicki A, Cichocki Ł, Kalisz A, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the course of schizophrenia in a 20-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):420-425.

3. Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, et al. Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(6):512-529.

4. Olabi B, Ellison-Wright I, McIntosh AM, et al. Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):88-96.

5. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

6. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

7. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

8. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

9. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

10. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

11. Nasrallah HA. The crisis of poor physical health and early mortality of psychiatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(4):7-8,11.

12. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

Psychosis and stroke are arguably the most serious acute threats to the integrity of the brain, and consequently the mind. Both are unquestionably associated with a grave outcome the longer their treatment is delayed.1,2

While the management of stroke has been elevated to the highest emergent priority because of the progressively deleterious impact of thrombotic ischemia in one of the cerebral arteries, rapid intervention for acute psychosis has never been regarded as an urgent neurologic condition with severe threats to the brain’s structure and function.3,4 There is extensive literature on the serious consequences of a long duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), including treatment resistance, frequent re-hospitalizations, more negative symptoms, and greater disability.5

Physical paralysis from a stroke receives much more attention than “mental paralysis” of psychosis. Both must be rapidly treated, whether for the regional ischemia to brain tissue following a stroke or for the neurotoxicity of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress that lead to widespread neurodegeneration during psychosis.6 While an acronym for the quick recognition of a stroke (FAST: Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties, and Time to call emergency services) is well established, no acronym for the urgency to treat psychosis has been developed. We propose the acronym RAPID (Readily Avoid Psychosis-Induced Damage). The acronym RAPID would hopefully expedite the urgently needed pharmacotherapeutic and psychosocial intervention in psychosis to halt ongoing brain tissue loss.

It is ironic that the legal obstacles for immediate treatment, which do not exist for stroke, often delay administering antipsychotic medication to patients with anosognosia (a neurologic delusional belief that one is not ill, leading to refusal of treatment) for their psychosis and end up harming patients by prolonging their DUP until a court order is obtained to force brain-saving treatment. Frequent psychotic relapses due to nonadherence with medications are also a very common cause for prolonged DUP due to the inexplicable reluctance of some psychiatric practitioners to employ a long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) medication as soon as possible after the onset of psychosis to circumvent subsequent relapses due to the very high risk of poor adherence. Table 1 describes the optimal management of both stroke and acute psychosis once they are rapidly diagnosed, thanks to the FAST and RAPID reminders.

Tragically, the treatments of the mind have become falsely disengaged from the brain, the physical organ whose neurons, electrical impulses, synapses, and neurotransmitters generate the mind with its advanced human functions, such as self-awareness, will, thoughts, mood, speech, executive functions, memories, and social cognition. Recent editorials have challenged psychiatric practitioners to behave like cardiologists7 and oncologists8 by aggressively treating first-episode psychosis to prevent ongoing neurodegeneration due to recurrences. The brain loses 1% of its brain volume (~11 ml) after the first psychotic episode,8 which represents hundreds of millions of cells, billions of synapses, and substantial myelin. A second psychotic episode causes significant additional neuropil and white matter fiber damage and represents a different stage of schizophrenia9 with more severe tissue loss and disruption of neural pathways that trigger the process of treatment resistance and functional disability. Ensuring adherence with LAI antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first psychotic episode may allow many patients with schizophrenia to achieve a relapse-free remission and to return to their baseline functioning.10

In addition to significant brain tissue loss during psychotic episodes, mortality is also a very high risk following discharge from the first hospitalization for psychosis.11 LAI second-generation antipsychotic medications have been shown to be associated with lower mortality and neuroprotective effects,12 compared with oral or injectable first-generation antipsychotics. The highest mortality rate was reported to be associated with the lack of any antipsychotic medication,12 underscoring how untreated psychosis can be fatal.

Bottom line: Rapid treatment of stroke and psychosis is an absolute imperative for minimizing brain damage that respectively leads to physical or mental disability. The acronyms FAST and RAPID are essential reminders of the urgency needed to halt progressive neurodegeneration in those 2 devastating acute threats to the integrity of brain and mind. Intensive physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation must follow the acute treatment of stroke and psychosis, and the prevention of any recurrence is an absolute must. For psychosis, the use of a LAI second-generation antipsychotic before hospital discharge from a first episode of psychosis can be disease-modifying, with a more benign illness trajectory and outcome than the devastating deterioration that follows repetitive psychotic relapse, most often due to nonadherence with oral medications.

Continue to: Psychosis should be conceptualized as...

Psychosis should be conceptualized as a “stroke of the mind,” and it can be prevented in most patients with schizophrenia by adopting injectable antipsychotics as early after the onset of psychosis as possible. Yet, starting a LAI antipsychotic drug in first-episode psychosis before hospital discharge is rarely done, and the few patients who currently receive LAIs (10% of U.S. patients) generally receive them after multiple episodes and a protracted DUP. That’s like calling the fire department when much of the house has turned to ashes, instead of calling them when the first small flame is noticed. It makes so much sense, but the decades-old practice of postponing the use of LAIs continues to ruin the lives of young persons in the prime of life. By changing our practice habits to early use of LAIs, we have nothing to lose and our patients with psychosis may be spared a lifetime of suffering, poverty, stigma, incarceration, and functional disability. Wouldn’t we want to avoid that atrocious outcome for our own family members if they develop schizophrenia?

Psychosis and stroke are arguably the most serious acute threats to the integrity of the brain, and consequently the mind. Both are unquestionably associated with a grave outcome the longer their treatment is delayed.1,2

While the management of stroke has been elevated to the highest emergent priority because of the progressively deleterious impact of thrombotic ischemia in one of the cerebral arteries, rapid intervention for acute psychosis has never been regarded as an urgent neurologic condition with severe threats to the brain’s structure and function.3,4 There is extensive literature on the serious consequences of a long duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), including treatment resistance, frequent re-hospitalizations, more negative symptoms, and greater disability.5

Physical paralysis from a stroke receives much more attention than “mental paralysis” of psychosis. Both must be rapidly treated, whether for the regional ischemia to brain tissue following a stroke or for the neurotoxicity of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress that lead to widespread neurodegeneration during psychosis.6 While an acronym for the quick recognition of a stroke (FAST: Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties, and Time to call emergency services) is well established, no acronym for the urgency to treat psychosis has been developed. We propose the acronym RAPID (Readily Avoid Psychosis-Induced Damage). The acronym RAPID would hopefully expedite the urgently needed pharmacotherapeutic and psychosocial intervention in psychosis to halt ongoing brain tissue loss.

It is ironic that the legal obstacles for immediate treatment, which do not exist for stroke, often delay administering antipsychotic medication to patients with anosognosia (a neurologic delusional belief that one is not ill, leading to refusal of treatment) for their psychosis and end up harming patients by prolonging their DUP until a court order is obtained to force brain-saving treatment. Frequent psychotic relapses due to nonadherence with medications are also a very common cause for prolonged DUP due to the inexplicable reluctance of some psychiatric practitioners to employ a long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) medication as soon as possible after the onset of psychosis to circumvent subsequent relapses due to the very high risk of poor adherence. Table 1 describes the optimal management of both stroke and acute psychosis once they are rapidly diagnosed, thanks to the FAST and RAPID reminders.

Tragically, the treatments of the mind have become falsely disengaged from the brain, the physical organ whose neurons, electrical impulses, synapses, and neurotransmitters generate the mind with its advanced human functions, such as self-awareness, will, thoughts, mood, speech, executive functions, memories, and social cognition. Recent editorials have challenged psychiatric practitioners to behave like cardiologists7 and oncologists8 by aggressively treating first-episode psychosis to prevent ongoing neurodegeneration due to recurrences. The brain loses 1% of its brain volume (~11 ml) after the first psychotic episode,8 which represents hundreds of millions of cells, billions of synapses, and substantial myelin. A second psychotic episode causes significant additional neuropil and white matter fiber damage and represents a different stage of schizophrenia9 with more severe tissue loss and disruption of neural pathways that trigger the process of treatment resistance and functional disability. Ensuring adherence with LAI antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first psychotic episode may allow many patients with schizophrenia to achieve a relapse-free remission and to return to their baseline functioning.10

In addition to significant brain tissue loss during psychotic episodes, mortality is also a very high risk following discharge from the first hospitalization for psychosis.11 LAI second-generation antipsychotic medications have been shown to be associated with lower mortality and neuroprotective effects,12 compared with oral or injectable first-generation antipsychotics. The highest mortality rate was reported to be associated with the lack of any antipsychotic medication,12 underscoring how untreated psychosis can be fatal.

Bottom line: Rapid treatment of stroke and psychosis is an absolute imperative for minimizing brain damage that respectively leads to physical or mental disability. The acronyms FAST and RAPID are essential reminders of the urgency needed to halt progressive neurodegeneration in those 2 devastating acute threats to the integrity of brain and mind. Intensive physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation must follow the acute treatment of stroke and psychosis, and the prevention of any recurrence is an absolute must. For psychosis, the use of a LAI second-generation antipsychotic before hospital discharge from a first episode of psychosis can be disease-modifying, with a more benign illness trajectory and outcome than the devastating deterioration that follows repetitive psychotic relapse, most often due to nonadherence with oral medications.

Continue to: Psychosis should be conceptualized as...

Psychosis should be conceptualized as a “stroke of the mind,” and it can be prevented in most patients with schizophrenia by adopting injectable antipsychotics as early after the onset of psychosis as possible. Yet, starting a LAI antipsychotic drug in first-episode psychosis before hospital discharge is rarely done, and the few patients who currently receive LAIs (10% of U.S. patients) generally receive them after multiple episodes and a protracted DUP. That’s like calling the fire department when much of the house has turned to ashes, instead of calling them when the first small flame is noticed. It makes so much sense, but the decades-old practice of postponing the use of LAIs continues to ruin the lives of young persons in the prime of life. By changing our practice habits to early use of LAIs, we have nothing to lose and our patients with psychosis may be spared a lifetime of suffering, poverty, stigma, incarceration, and functional disability. Wouldn’t we want to avoid that atrocious outcome for our own family members if they develop schizophrenia?

1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

2. Cechnicki A, Cichocki Ł, Kalisz A, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the course of schizophrenia in a 20-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):420-425.

3. Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, et al. Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(6):512-529.

4. Olabi B, Ellison-Wright I, McIntosh AM, et al. Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):88-96.

5. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

6. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

7. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

8. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

9. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

10. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

11. Nasrallah HA. The crisis of poor physical health and early mortality of psychiatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(4):7-8,11.

12. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

2. Cechnicki A, Cichocki Ł, Kalisz A, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the course of schizophrenia in a 20-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):420-425.

3. Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, et al. Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(6):512-529.

4. Olabi B, Ellison-Wright I, McIntosh AM, et al. Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):88-96.

5. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

6. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

7. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

8. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

9. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

10. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

11. Nasrallah HA. The crisis of poor physical health and early mortality of psychiatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(4):7-8,11.

12. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

Optimize the medical treatment of endometriosis—Use all available medications

CASE Endometriosis pain increases despite hormonal treatment

A 25-year-old woman (G0) with severe dysmenorrhea had a laparoscopy showing endometriosis in the cul-de-sac and a peritoneal window near the left uterosacral ligament. Biopsy of a cul-de-sac lesion showed endometriosis on histopathology. The patient was treated with a continuous low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive. Initially, the treatment helped relieve her pain symptoms. Over the next year, while on that treatment, her pain gradually increased in severity until it was disabling. At an office visit, the primary clinician renewed the estrogen-progestin contraceptive for another year, even though it was not relieving the patient’s pain. The patient sought a second opinion.

We are the experts in the management of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

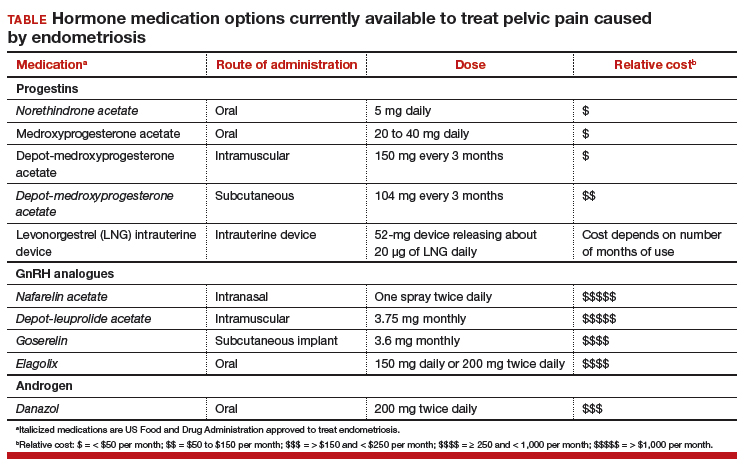

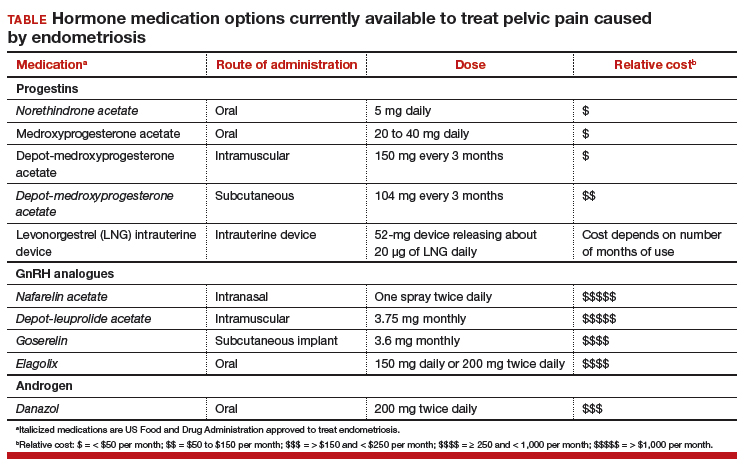

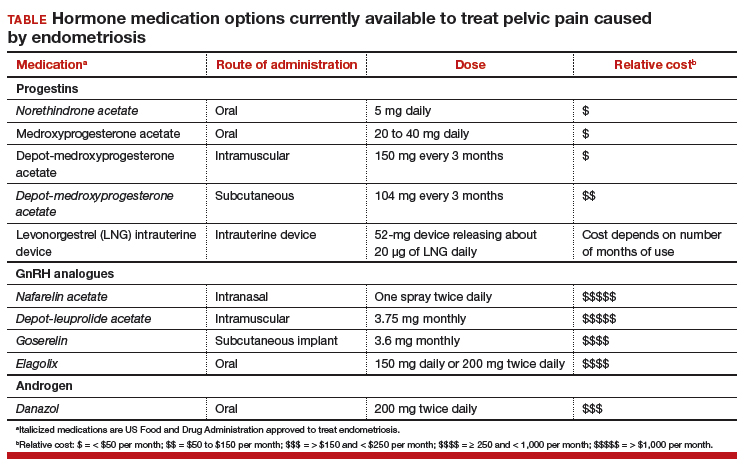

Women’s health clinicians are the specialists best trained to care for patients with severe pain caused by endometriosis. Low-dose continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed as a first-line hormonal treatment for pain caused by endometriosis. My observation is that estrogen-progestincontraceptives are often effective when initially prescribed, but with continued use over years, pain often recurs. Estrogen is known to stimulate endometriosis disease activity. Progestins at high doses suppress endometriosis disease activity. However, endometriosis implants often manifest decreased responsiveness to progestins, permitting the estrogen in the combination contraceptive to exert its disease-stimulating effect.1,2 I frequently see women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, who initially had a significant decrease in pain with continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment but who develop increasing pain with continued use of the medication. In this clinical situation, it is useful to consider stopping the estrogen-progestin therapy and to prescribe a hormone with a different mechanism of action (TABLE).

Progestin-only medications

Progestin-only medications are often effective in the treatment of pain caused by endometriosis. High-dose progestin-only medications suppress pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thereby suppressing ovarian synthesis of estrogen, resulting in low circulating levels of estrogen. This removes the estrogen stimulus that exacerbates endometriosis disease activity. High-dose progestins also directly suppress cellular activity in endometriosis implants. High-dose progestins often overcome the relative resistance of endometriosis lesions to progestin suppression of disease activity. Hence, high-dose progestin-only medications have two mechanisms of action: suppression of estrogen synthesis through pituitary suppression of LH and FSH, and direct inhibition of cellular activity in the endometriosis lesions. High-dose progestin-only treatments include:

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily

- oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 20 to 40 mg daily

- subcutaneous, or depot MPA

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD).

In my practice, I frequently use oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In one randomized trial, 90 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were randomly assigned to treatment with norethindrone acetate 2.5 mg daily or an estrogen-progestin contraceptive. After 12 months of treatment, satisfaction with treatment was reported by 73% and 62% of the women in the norethindrone acetate and estrogen-progestin groups, respectively.3 The most common adverse effects reported by women taking norethindrone acetate were weight gain (27%) and decreased libido (9%).

Oral MPA at doses of 30 mg to 100 mg daily has been reported to be effective for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. MPA treatment can induce atrophy and pseudodecidualization in endometrium and endometriosis implants. In my practice I typically prescribe doses in the range of 20 mg to 40 mg daily. With oral MPA treatment, continued uterine bleeding may occur in up to 30% of women, somewhat limiting its efficacy.4–7

Subcutaneous and depot MPA have been reported to be effective in the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.4,8 In some resource-limited countries, depot MPA may be the most available progestin for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

The LNG-IUD, inserted after surgery for endometriosis, has been reported to result in decreased pelvic pain in studies with a modest number of participants.9–11

GnRH analogue medications

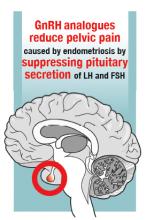

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, including both GnRH agonists (nafarelin, leuprolide, and goserelin) and GnRH antagonists (elagolix) reduce pelvic pain caused by endometriosis by suppressing pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, thereby reducing ovarian synthesis of estradiol. In the absence of estradiol stimulation, cellular activity in endometriosis lesions decreases and pain symptoms improve. In my practice, I frequently use either nafarelin12 or leuprolide acetate depot plus norethindrone add-back.13 I generally avoid the use of leuprolide depot monotherapy because in many women it causes severe vasomotor symptoms.

At standard doses, nafarelin therapy generally results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, a “sweet spot” associated with modest vasomotor symptoms and reduced cellular activity in endometriosis implants.12,14 In many women who become amenorrheic on nafarelin two sprays daily, the dose can be reduced with maintenance of pain control and ovarian suppression.15 Leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 5 to 10 pg/mL, causing severe vasomotor symptoms and reduction in cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. To reduce the adverse effects of leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy, I generally initiate concomitant add-back therapy with norethindrone acetate.13 A little recognized pharmacokinetic observation is that a very small amount of norethindrone acetate, generally less than 1%, is metabolized to ethinyl estradiol.16

The oral GnRH antagonist, elagolix, 150 mg daily for up to 24 months or 200 mg twice daily for 6 months, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2018. It is now available in pharmacies. Elagolix treatment results in significant reduction in pain caused by endometriosis, but only moderately bothersome vasomotor symptoms.17,18 Elagolix likely will become a widely used medication because of the simplicity of oral administration, efficacy against endometriosis, and acceptable adverse-effect profile. A major disadvantage of the GnRH analogue-class of medications is that they are more expensive than the progestin medications mentioned above. Among the GnRH analogue class of medications, elagolix and goserelin are the least expensive.

Androgens

Estrogen stimulates cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Androgen and high-dose progestins inhibit cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Danazol, an attenuated androgen and a progestin is effectivein treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.19,20 However, many women decline to use danazol because it is often associated with weight gain. As an androgen, danazol can permanently change a woman’s voice pitch and should not be used by professional singers or speech therapists.

Aromatase Inhibitors

Estrogen is a critically important stimulus of cell activity in endometriosis lesions. Aromatase inhibitors, which block the synthesis of estrogen, have been explored in the treatment of endometriosis that has proven to be resistant to other therapies. Although the combination of an aromatase inhibitor plus a high-dose progestin or GnRH analogue may be effective, more data are needed before widely using the aromatase inhibitors in clinical practice.21

Don’t get stuck in a rut

When treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, if the patient’s hormone regimen is not working, prescribe a medication from another class of hormones. In the case presented above, a woman with pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis reported inadequate control of her pain symptoms with a continuous estrogen-progestin medication. Her physician prescribed another year of the same estrogen-progestin medication. Instead of renewing the medication, the physician could have offered the patient a hormone medication from another drug class: 1) progestin only, 2) GnRH analogue, or 3) danazol. By using every available hormonal agent, physicians will improve the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Millions of women in our country have pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. They are counting on us, women’s health specialists, to effectively treat their disease.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Patel BG, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor RN. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):623–632.

- Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):36–43.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

- Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD002122.

- Moghissi KS, Boyce CR. Management of endometriosis with oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47(3):265–267.

- Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Rönnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1(1):13–23.

- Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 pt 1):323–327.

- Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leu-prolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314–325.

- Abou-Setta AM, Houston B, Al-Inany HG, Farquhar C. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD005072.

- Tanmahasamut P, Rattanachaiyanont M, Angsuwathana S, Techatraisak K, Indhavivadhana S, Leerasiri P. Postoperative levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for pelvic endometriosis-pain: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):519–526.

- Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273–279.

- Henzl MR, Corson SL, Moghissi K, Buttram VC, Berqvist C, Jacobsen J. Administration of nasal nafarelin as compared with oral danazol for endo-metriosis. A multicenter double-blind comparative clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(8):485–489.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 91(1):16–24.

- Barbieri RL. Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(2):740–745.

- Hull ME, Barbieri RL. Nafarelin in the treatment of endometriosis. Dose management. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;37(4):263–264.

- Barbieri RL, Petro Z, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. Aromatization of norethindrone to ethinyl estradiol by human placental microsomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(2):299–303.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28–40.

- Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):147–160.

- Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000068.

- Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Danazol: endocrine pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(4):453–463.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

CASE Endometriosis pain increases despite hormonal treatment

A 25-year-old woman (G0) with severe dysmenorrhea had a laparoscopy showing endometriosis in the cul-de-sac and a peritoneal window near the left uterosacral ligament. Biopsy of a cul-de-sac lesion showed endometriosis on histopathology. The patient was treated with a continuous low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive. Initially, the treatment helped relieve her pain symptoms. Over the next year, while on that treatment, her pain gradually increased in severity until it was disabling. At an office visit, the primary clinician renewed the estrogen-progestin contraceptive for another year, even though it was not relieving the patient’s pain. The patient sought a second opinion.

We are the experts in the management of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

Women’s health clinicians are the specialists best trained to care for patients with severe pain caused by endometriosis. Low-dose continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed as a first-line hormonal treatment for pain caused by endometriosis. My observation is that estrogen-progestincontraceptives are often effective when initially prescribed, but with continued use over years, pain often recurs. Estrogen is known to stimulate endometriosis disease activity. Progestins at high doses suppress endometriosis disease activity. However, endometriosis implants often manifest decreased responsiveness to progestins, permitting the estrogen in the combination contraceptive to exert its disease-stimulating effect.1,2 I frequently see women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, who initially had a significant decrease in pain with continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment but who develop increasing pain with continued use of the medication. In this clinical situation, it is useful to consider stopping the estrogen-progestin therapy and to prescribe a hormone with a different mechanism of action (TABLE).

Progestin-only medications

Progestin-only medications are often effective in the treatment of pain caused by endometriosis. High-dose progestin-only medications suppress pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thereby suppressing ovarian synthesis of estrogen, resulting in low circulating levels of estrogen. This removes the estrogen stimulus that exacerbates endometriosis disease activity. High-dose progestins also directly suppress cellular activity in endometriosis implants. High-dose progestins often overcome the relative resistance of endometriosis lesions to progestin suppression of disease activity. Hence, high-dose progestin-only medications have two mechanisms of action: suppression of estrogen synthesis through pituitary suppression of LH and FSH, and direct inhibition of cellular activity in the endometriosis lesions. High-dose progestin-only treatments include:

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily

- oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 20 to 40 mg daily

- subcutaneous, or depot MPA

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD).

In my practice, I frequently use oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In one randomized trial, 90 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were randomly assigned to treatment with norethindrone acetate 2.5 mg daily or an estrogen-progestin contraceptive. After 12 months of treatment, satisfaction with treatment was reported by 73% and 62% of the women in the norethindrone acetate and estrogen-progestin groups, respectively.3 The most common adverse effects reported by women taking norethindrone acetate were weight gain (27%) and decreased libido (9%).

Oral MPA at doses of 30 mg to 100 mg daily has been reported to be effective for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. MPA treatment can induce atrophy and pseudodecidualization in endometrium and endometriosis implants. In my practice I typically prescribe doses in the range of 20 mg to 40 mg daily. With oral MPA treatment, continued uterine bleeding may occur in up to 30% of women, somewhat limiting its efficacy.4–7

Subcutaneous and depot MPA have been reported to be effective in the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.4,8 In some resource-limited countries, depot MPA may be the most available progestin for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

The LNG-IUD, inserted after surgery for endometriosis, has been reported to result in decreased pelvic pain in studies with a modest number of participants.9–11

GnRH analogue medications

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, including both GnRH agonists (nafarelin, leuprolide, and goserelin) and GnRH antagonists (elagolix) reduce pelvic pain caused by endometriosis by suppressing pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, thereby reducing ovarian synthesis of estradiol. In the absence of estradiol stimulation, cellular activity in endometriosis lesions decreases and pain symptoms improve. In my practice, I frequently use either nafarelin12 or leuprolide acetate depot plus norethindrone add-back.13 I generally avoid the use of leuprolide depot monotherapy because in many women it causes severe vasomotor symptoms.

At standard doses, nafarelin therapy generally results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, a “sweet spot” associated with modest vasomotor symptoms and reduced cellular activity in endometriosis implants.12,14 In many women who become amenorrheic on nafarelin two sprays daily, the dose can be reduced with maintenance of pain control and ovarian suppression.15 Leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 5 to 10 pg/mL, causing severe vasomotor symptoms and reduction in cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. To reduce the adverse effects of leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy, I generally initiate concomitant add-back therapy with norethindrone acetate.13 A little recognized pharmacokinetic observation is that a very small amount of norethindrone acetate, generally less than 1%, is metabolized to ethinyl estradiol.16

The oral GnRH antagonist, elagolix, 150 mg daily for up to 24 months or 200 mg twice daily for 6 months, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2018. It is now available in pharmacies. Elagolix treatment results in significant reduction in pain caused by endometriosis, but only moderately bothersome vasomotor symptoms.17,18 Elagolix likely will become a widely used medication because of the simplicity of oral administration, efficacy against endometriosis, and acceptable adverse-effect profile. A major disadvantage of the GnRH analogue-class of medications is that they are more expensive than the progestin medications mentioned above. Among the GnRH analogue class of medications, elagolix and goserelin are the least expensive.

Androgens

Estrogen stimulates cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Androgen and high-dose progestins inhibit cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Danazol, an attenuated androgen and a progestin is effectivein treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.19,20 However, many women decline to use danazol because it is often associated with weight gain. As an androgen, danazol can permanently change a woman’s voice pitch and should not be used by professional singers or speech therapists.

Aromatase Inhibitors

Estrogen is a critically important stimulus of cell activity in endometriosis lesions. Aromatase inhibitors, which block the synthesis of estrogen, have been explored in the treatment of endometriosis that has proven to be resistant to other therapies. Although the combination of an aromatase inhibitor plus a high-dose progestin or GnRH analogue may be effective, more data are needed before widely using the aromatase inhibitors in clinical practice.21

Don’t get stuck in a rut

When treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, if the patient’s hormone regimen is not working, prescribe a medication from another class of hormones. In the case presented above, a woman with pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis reported inadequate control of her pain symptoms with a continuous estrogen-progestin medication. Her physician prescribed another year of the same estrogen-progestin medication. Instead of renewing the medication, the physician could have offered the patient a hormone medication from another drug class: 1) progestin only, 2) GnRH analogue, or 3) danazol. By using every available hormonal agent, physicians will improve the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Millions of women in our country have pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. They are counting on us, women’s health specialists, to effectively treat their disease.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Endometriosis pain increases despite hormonal treatment

A 25-year-old woman (G0) with severe dysmenorrhea had a laparoscopy showing endometriosis in the cul-de-sac and a peritoneal window near the left uterosacral ligament. Biopsy of a cul-de-sac lesion showed endometriosis on histopathology. The patient was treated with a continuous low-dose estrogen-progestin contraceptive. Initially, the treatment helped relieve her pain symptoms. Over the next year, while on that treatment, her pain gradually increased in severity until it was disabling. At an office visit, the primary clinician renewed the estrogen-progestin contraceptive for another year, even though it was not relieving the patient’s pain. The patient sought a second opinion.

We are the experts in the management of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

Women’s health clinicians are the specialists best trained to care for patients with severe pain caused by endometriosis. Low-dose continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed as a first-line hormonal treatment for pain caused by endometriosis. My observation is that estrogen-progestincontraceptives are often effective when initially prescribed, but with continued use over years, pain often recurs. Estrogen is known to stimulate endometriosis disease activity. Progestins at high doses suppress endometriosis disease activity. However, endometriosis implants often manifest decreased responsiveness to progestins, permitting the estrogen in the combination contraceptive to exert its disease-stimulating effect.1,2 I frequently see women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, who initially had a significant decrease in pain with continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment but who develop increasing pain with continued use of the medication. In this clinical situation, it is useful to consider stopping the estrogen-progestin therapy and to prescribe a hormone with a different mechanism of action (TABLE).

Progestin-only medications

Progestin-only medications are often effective in the treatment of pain caused by endometriosis. High-dose progestin-only medications suppress pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thereby suppressing ovarian synthesis of estrogen, resulting in low circulating levels of estrogen. This removes the estrogen stimulus that exacerbates endometriosis disease activity. High-dose progestins also directly suppress cellular activity in endometriosis implants. High-dose progestins often overcome the relative resistance of endometriosis lesions to progestin suppression of disease activity. Hence, high-dose progestin-only medications have two mechanisms of action: suppression of estrogen synthesis through pituitary suppression of LH and FSH, and direct inhibition of cellular activity in the endometriosis lesions. High-dose progestin-only treatments include:

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily

- oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 20 to 40 mg daily

- subcutaneous, or depot MPA

- levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD).

In my practice, I frequently use oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In one randomized trial, 90 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis were randomly assigned to treatment with norethindrone acetate 2.5 mg daily or an estrogen-progestin contraceptive. After 12 months of treatment, satisfaction with treatment was reported by 73% and 62% of the women in the norethindrone acetate and estrogen-progestin groups, respectively.3 The most common adverse effects reported by women taking norethindrone acetate were weight gain (27%) and decreased libido (9%).

Oral MPA at doses of 30 mg to 100 mg daily has been reported to be effective for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. MPA treatment can induce atrophy and pseudodecidualization in endometrium and endometriosis implants. In my practice I typically prescribe doses in the range of 20 mg to 40 mg daily. With oral MPA treatment, continued uterine bleeding may occur in up to 30% of women, somewhat limiting its efficacy.4–7

Subcutaneous and depot MPA have been reported to be effective in the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.4,8 In some resource-limited countries, depot MPA may be the most available progestin for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.

The LNG-IUD, inserted after surgery for endometriosis, has been reported to result in decreased pelvic pain in studies with a modest number of participants.9–11

GnRH analogue medications

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, including both GnRH agonists (nafarelin, leuprolide, and goserelin) and GnRH antagonists (elagolix) reduce pelvic pain caused by endometriosis by suppressing pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, thereby reducing ovarian synthesis of estradiol. In the absence of estradiol stimulation, cellular activity in endometriosis lesions decreases and pain symptoms improve. In my practice, I frequently use either nafarelin12 or leuprolide acetate depot plus norethindrone add-back.13 I generally avoid the use of leuprolide depot monotherapy because in many women it causes severe vasomotor symptoms.

At standard doses, nafarelin therapy generally results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, a “sweet spot” associated with modest vasomotor symptoms and reduced cellular activity in endometriosis implants.12,14 In many women who become amenorrheic on nafarelin two sprays daily, the dose can be reduced with maintenance of pain control and ovarian suppression.15 Leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy results in serum estradiol levels in the range of 5 to 10 pg/mL, causing severe vasomotor symptoms and reduction in cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. To reduce the adverse effects of leuprolide acetate depot monotherapy, I generally initiate concomitant add-back therapy with norethindrone acetate.13 A little recognized pharmacokinetic observation is that a very small amount of norethindrone acetate, generally less than 1%, is metabolized to ethinyl estradiol.16

The oral GnRH antagonist, elagolix, 150 mg daily for up to 24 months or 200 mg twice daily for 6 months, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2018. It is now available in pharmacies. Elagolix treatment results in significant reduction in pain caused by endometriosis, but only moderately bothersome vasomotor symptoms.17,18 Elagolix likely will become a widely used medication because of the simplicity of oral administration, efficacy against endometriosis, and acceptable adverse-effect profile. A major disadvantage of the GnRH analogue-class of medications is that they are more expensive than the progestin medications mentioned above. Among the GnRH analogue class of medications, elagolix and goserelin are the least expensive.

Androgens

Estrogen stimulates cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Androgen and high-dose progestins inhibit cellular activity in endometriosis lesions. Danazol, an attenuated androgen and a progestin is effectivein treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis.19,20 However, many women decline to use danazol because it is often associated with weight gain. As an androgen, danazol can permanently change a woman’s voice pitch and should not be used by professional singers or speech therapists.

Aromatase Inhibitors

Estrogen is a critically important stimulus of cell activity in endometriosis lesions. Aromatase inhibitors, which block the synthesis of estrogen, have been explored in the treatment of endometriosis that has proven to be resistant to other therapies. Although the combination of an aromatase inhibitor plus a high-dose progestin or GnRH analogue may be effective, more data are needed before widely using the aromatase inhibitors in clinical practice.21

Don’t get stuck in a rut

When treating pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, if the patient’s hormone regimen is not working, prescribe a medication from another class of hormones. In the case presented above, a woman with pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis reported inadequate control of her pain symptoms with a continuous estrogen-progestin medication. Her physician prescribed another year of the same estrogen-progestin medication. Instead of renewing the medication, the physician could have offered the patient a hormone medication from another drug class: 1) progestin only, 2) GnRH analogue, or 3) danazol. By using every available hormonal agent, physicians will improve the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Millions of women in our country have pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. They are counting on us, women’s health specialists, to effectively treat their disease.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Patel BG, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor RN. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):623–632.

- Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):36–43.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

- Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD002122.

- Moghissi KS, Boyce CR. Management of endometriosis with oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47(3):265–267.

- Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Rönnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1(1):13–23.

- Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 pt 1):323–327.

- Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leu-prolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314–325.

- Abou-Setta AM, Houston B, Al-Inany HG, Farquhar C. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD005072.

- Tanmahasamut P, Rattanachaiyanont M, Angsuwathana S, Techatraisak K, Indhavivadhana S, Leerasiri P. Postoperative levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for pelvic endometriosis-pain: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):519–526.

- Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273–279.

- Henzl MR, Corson SL, Moghissi K, Buttram VC, Berqvist C, Jacobsen J. Administration of nasal nafarelin as compared with oral danazol for endo-metriosis. A multicenter double-blind comparative clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(8):485–489.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 91(1):16–24.

- Barbieri RL. Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(2):740–745.

- Hull ME, Barbieri RL. Nafarelin in the treatment of endometriosis. Dose management. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;37(4):263–264.

- Barbieri RL, Petro Z, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. Aromatization of norethindrone to ethinyl estradiol by human placental microsomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(2):299–303.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28–40.

- Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):147–160.

- Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000068.

- Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Danazol: endocrine pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(4):453–463.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

- Patel BG, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor RN. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):623–632.

- Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):36–43.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, Pasin R, Chiodini A, Crosignani PG. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(5):1375-1387.

- Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD002122.

- Moghissi KS, Boyce CR. Management of endometriosis with oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47(3):265–267.

- Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Rönnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1(1):13–23.

- Luciano AA, Turksoy RN, Carleo J. Evaluation of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 pt 1):323–327.

- Schlaff WD, Carson SA, Luciano A, Ross D, Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leu-prolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):314–325.

- Abou-Setta AM, Houston B, Al-Inany HG, Farquhar C. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD005072.

- Tanmahasamut P, Rattanachaiyanont M, Angsuwathana S, Techatraisak K, Indhavivadhana S, Leerasiri P. Postoperative levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for pelvic endometriosis-pain: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):519–526.

- Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):273–279.

- Henzl MR, Corson SL, Moghissi K, Buttram VC, Berqvist C, Jacobsen J. Administration of nasal nafarelin as compared with oral danazol for endo-metriosis. A multicenter double-blind comparative clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(8):485–489.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 91(1):16–24.

- Barbieri RL. Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(2):740–745.

- Hull ME, Barbieri RL. Nafarelin in the treatment of endometriosis. Dose management. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;37(4):263–264.

- Barbieri RL, Petro Z, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. Aromatization of norethindrone to ethinyl estradiol by human placental microsomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(2):299–303.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28–40.

- Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):147–160.

- Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000068.

- Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ. Danazol: endocrine pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(4):453–463.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400–412.

The bias of word choice and the interpretation of laboratory tests

In the current sociopolitical environment in the United States, the slogan “words matter” has become a battle cry for several groups and causes, emphasizing that our choice of words can influence the way we assess a specific person or situation. We are not immune to the subliminal bias of words, even as we evaluate such seemingly objective components of clinical management as laboratory test results.

Several years ago, I was supervising teaching rounds on a general medicine service. It was the first rounds of the month, and the patients were relatively new to the residents and totally unknown to me. One patient was an elderly man with weight loss, fatigue, weakness, and a history of excessive alcohol ingestion. His family had corroborated the last detail, but he had stopped drinking a long time before his admission. He had normal creatinine, minimal anemia, and markedly elevated and unexplained “liver function tests.” Liver biopsy was planned.

As we entered his room, we saw a gaunt man struggle to rise from the bedside chair to get back into bed. He rocked several times and then pushed himself up from the chair using his arms. Then, after a few short steps, he plopped back into bed and greeted us. His breakfast tray was untouched at the bedside. I introduced myself, we chatted for a short while as I examined him in front of our team, and we left.

In the hallway I asked, “Who would like to get an additional blood test before we do a liver biopsy?” Without waiting for a response I asked a second question, “What exactly are liver function tests?”

Words do matter, and they influence the way we analyze clinical scenarios. It could be argued that a complete and careful history would have established that our patient’s fatigue and weakness were due to proximal muscle weakness and not general asthenia, and that detailed questioning would have revealed that his weight loss was mainly from difficulty in swallowing without a sense of choking and coughing. But faced with an elderly man, a likely explanation for liver disease, and markedly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase (AST and ALT) levels, there was premature closure of the diagnosis, and the decision was made to obtain a liver biopsy—which our hepatology consultants surely would not have done. I believe that a major contributor to the premature diagnosis was the choice of the words “liver function tests” and the default assumption that elevated serum levels of these enzymes always reflect liver disease.

Aminotransferases are fairly ubiquitous, likely present in various concentrations in all cells in our body. AST exists in mitochondrial and cytosolic forms, and ALT in the cytosol. The concentration of ALT is higher in the liver than in other organs, and its enzymatic activity is suppressed by hepatic exposure to alcohol. Both enzymes are present in muscle, and although AST is more abundant in cells other than hepatocytes, the longer serum half-life of ALT may result in roughly equal serum levels in the setting of chronic muscle injury such as myositis (the true diagnosis in our weak patient).

While a meticulous history and examination would indeed have led to the diagnosis of muscle disease in this man, they alone could not have determined whether he had coexistent liver and muscle disease. And this is a real challenge when acute muscle toxicity and liver toxicity are equally possible (eg, statin or immune checkpoint autoimmune tissue damage, or after significant trauma).

There are many nuances in the interpretation of even the most common laboratory tests. In this issue of the Journal, Agganis et al discuss liver enzymes (a term slightly more acceptable to me than liver function tests). In future issues, we will address the interpretation of other laboratory tests.

In the current sociopolitical environment in the United States, the slogan “words matter” has become a battle cry for several groups and causes, emphasizing that our choice of words can influence the way we assess a specific person or situation. We are not immune to the subliminal bias of words, even as we evaluate such seemingly objective components of clinical management as laboratory test results.

Several years ago, I was supervising teaching rounds on a general medicine service. It was the first rounds of the month, and the patients were relatively new to the residents and totally unknown to me. One patient was an elderly man with weight loss, fatigue, weakness, and a history of excessive alcohol ingestion. His family had corroborated the last detail, but he had stopped drinking a long time before his admission. He had normal creatinine, minimal anemia, and markedly elevated and unexplained “liver function tests.” Liver biopsy was planned.

As we entered his room, we saw a gaunt man struggle to rise from the bedside chair to get back into bed. He rocked several times and then pushed himself up from the chair using his arms. Then, after a few short steps, he plopped back into bed and greeted us. His breakfast tray was untouched at the bedside. I introduced myself, we chatted for a short while as I examined him in front of our team, and we left.

In the hallway I asked, “Who would like to get an additional blood test before we do a liver biopsy?” Without waiting for a response I asked a second question, “What exactly are liver function tests?”

Words do matter, and they influence the way we analyze clinical scenarios. It could be argued that a complete and careful history would have established that our patient’s fatigue and weakness were due to proximal muscle weakness and not general asthenia, and that detailed questioning would have revealed that his weight loss was mainly from difficulty in swallowing without a sense of choking and coughing. But faced with an elderly man, a likely explanation for liver disease, and markedly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase (AST and ALT) levels, there was premature closure of the diagnosis, and the decision was made to obtain a liver biopsy—which our hepatology consultants surely would not have done. I believe that a major contributor to the premature diagnosis was the choice of the words “liver function tests” and the default assumption that elevated serum levels of these enzymes always reflect liver disease.

Aminotransferases are fairly ubiquitous, likely present in various concentrations in all cells in our body. AST exists in mitochondrial and cytosolic forms, and ALT in the cytosol. The concentration of ALT is higher in the liver than in other organs, and its enzymatic activity is suppressed by hepatic exposure to alcohol. Both enzymes are present in muscle, and although AST is more abundant in cells other than hepatocytes, the longer serum half-life of ALT may result in roughly equal serum levels in the setting of chronic muscle injury such as myositis (the true diagnosis in our weak patient).

While a meticulous history and examination would indeed have led to the diagnosis of muscle disease in this man, they alone could not have determined whether he had coexistent liver and muscle disease. And this is a real challenge when acute muscle toxicity and liver toxicity are equally possible (eg, statin or immune checkpoint autoimmune tissue damage, or after significant trauma).

There are many nuances in the interpretation of even the most common laboratory tests. In this issue of the Journal, Agganis et al discuss liver enzymes (a term slightly more acceptable to me than liver function tests). In future issues, we will address the interpretation of other laboratory tests.

In the current sociopolitical environment in the United States, the slogan “words matter” has become a battle cry for several groups and causes, emphasizing that our choice of words can influence the way we assess a specific person or situation. We are not immune to the subliminal bias of words, even as we evaluate such seemingly objective components of clinical management as laboratory test results.

Several years ago, I was supervising teaching rounds on a general medicine service. It was the first rounds of the month, and the patients were relatively new to the residents and totally unknown to me. One patient was an elderly man with weight loss, fatigue, weakness, and a history of excessive alcohol ingestion. His family had corroborated the last detail, but he had stopped drinking a long time before his admission. He had normal creatinine, minimal anemia, and markedly elevated and unexplained “liver function tests.” Liver biopsy was planned.

As we entered his room, we saw a gaunt man struggle to rise from the bedside chair to get back into bed. He rocked several times and then pushed himself up from the chair using his arms. Then, after a few short steps, he plopped back into bed and greeted us. His breakfast tray was untouched at the bedside. I introduced myself, we chatted for a short while as I examined him in front of our team, and we left.

In the hallway I asked, “Who would like to get an additional blood test before we do a liver biopsy?” Without waiting for a response I asked a second question, “What exactly are liver function tests?”