User login

Should a Patient Who Requests Alcohol Detoxification Be Admitted or Treated as Outpatient?

Case

A 42-year-old man with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypertension, and alcohol use disorder (AUD) presents to the ED requesting alcohol detoxification. He has had six admissions in the last six months for alcohol detoxification. Two years ago, the patient had a documented alcohol withdrawal seizure. His last drink was eight hours ago, and he currently drinks a liter of vodka a day. On exam, his pulse rate is 126 bpm, and his blood pressure is 162/91 mm Hg. He appears anxious and has bilateral hand tremors. His serum ethanol level is 388.6 mg/dL.

Overview

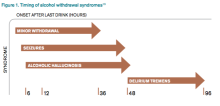

DSM-5 integrated alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence that were previously classified in DSM-IV into AUDs with mild, moderate, and severe subclassifications. AUDs are the most serious substance abuse problem in the U.S. In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse is 17.8% and of alcohol dependence is 12.5%.1–3 One study estimates that 24% of adult patients brought to the ED by ambulance suffer from alcoholism, and approximately 10% to 32% of hospitalized medical patients have an AUD.4–8 Patients who stop drinking will develop alcohol withdrawal as early as six hours after their last drink (see Figure 1). The majority of patients at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) will develop only minor uncomplicated symptoms, but up to 20% will develop symptoms associated with complicated AWS, including withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens (DT).9 It is not entirely clear why some individuals suffer from more severe withdrawal symptoms than others, but genetic predisposition may play a role.10

DT is a syndrome characterized by agitation, disorientation, hallucinations, and autonomic instability (tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis) in the setting of acute reduction or abstinence from alcohol and is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%.11 Complicated AWS is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality, longer lengths of stay, inflated costs of care, increased burden and frustration of nursing and medical staff, and worse cognitive functioning.9 In 80% of cases, the symptoms of uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal do not require aggressive medical intervention and usually disappear within two to seven days of the last drink.12 Physicians making triage decisions for patients who present to the ED in need of detoxification face a difficult dilemma concerning inpatient versus outpatient treatment.

Review of the Data

The literature on both inpatient and outpatient management and treatment of AWS is well-described. Currently, there are no guidelines or consensus on whether to admit patients with alcohol abuse syndromes to the hospital when the request for detoxification is made. Admission should be considered for all patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal who present to the ED.13 Patients with mild AWS may be discharged if they do not require admission for an additional medical condition, but patients experiencing moderate to severe withdrawal require admission for monitoring and treatment. Many physicians use a simple assessment of past history of DT and pulse rate, which may be easily evaluated in clinical settings, to readily identify patients who are at high risk of developing DT during an alcohol dependence period.14

Since 1978, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) has been consistently used for both monitoring patients with alcohol withdrawal and for making an initial assessment. CIWA-Ar was developed as a revised scale and is frequently used to monitor the severity of ongoing alcohol withdrawal and the response to treatment for the clinical care of patients in alcohol withdrawal (see Figure 2). CIWA-Ar was not developed to identify patients at risk for AWS but is frequently used to determine if patients require admission to the hospital for detoxification.15 Patients with CIWA-Ar scores > 15 require inpatient detoxification. Patients with scores between 8 and 15 should be admitted if they have a history of prior seizures or DT but could otherwise be considered for outpatient detoxification. Patients with scores < 8, which are considered mild alcohol withdrawal, can likely be safely treated as outpatients unless they have a history of DT or alcohol withdrawal seizures.16 Because symptoms of severe alcohol withdrawal are often not present for more than six hours after the patient’s last drink, or often longer, CIWA-Ar is limited and does not identify patients who are otherwise at high risk for complicated withdrawal. A protocol was developed incorporating the patient’s history of alcohol withdrawal seizure, DT, and the CIWA to evaluate the outcome of outpatient versus inpatient detoxification.16

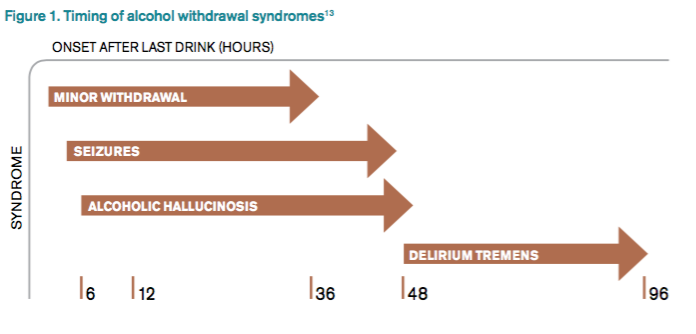

The most promising tool to screen patients for AWS was developed recently by researchers at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif., using an extensive systematic literature search to identify evidence-based clinical factors associated with the development of AWS.15 The Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) was subsequently constructed from 10 items correlating with complicated AWS (see Figure 3). When using a PAWSS score cutoff of ≥ 4, the predictive value of identifying a patient who is at risk for complicated withdrawal is significantly increased to 93.1%. This tool has only been used in medically ill patients but could be extrapolated for use in patients who present to an acute-care setting requesting inpatient detoxification.

Patients presenting to the ED with alcohol withdrawal seizures have been shown to have an associated 35% risk of progression to DT when found to have a low platelet count, low blood pyridoxine, and a high blood level of homocysteine. In another retrospective cohort study in Hepatology, three clinical features were identified to be associated with an increased risk for DT: alcohol dependence, a prior history of DT, and a higher pulse rate at admission (> 100 bpm).14

Instructions for the assessment of the patient who requests detoxification are as follows:

- A patient whose last drink of alcohol was more than five days ago and who shows no signs of withdrawal is unlikely to develop significant withdrawal symptoms and does not require inpatient detoxification.

- Other medical and psychiatric conditions should be evaluated for admission including alcohol use disorder complications.

- Calculate CIWA-Ar score:

Scores < 8 may not need detoxification; consider calculating PAWSS score.

Scores of 8 to 15 without symptoms of DT or seizures can be treated as an outpatient detoxification if no contraindication.

Scores of ≥ 15 should be admitted to the hospital.

- Calculate PAWSS score:

Scores ≥ 4 suggest high risk for moderate to severe complicated AWS, and admission should be considered.

Scores < 4 suggest lower risk for complicated AWS, and outpatient treatment should be considered if patients do not have a medical or surgical diagnosis requiring admission.

Back to the Case

At the time of his presentation, the patient was beginning to show signs of early withdrawal symptoms, including tremor and tachycardia, despite having an elevated blood alcohol level. This patient had a PAWSS score of 6, placing him at increased risk of complicated AWS, and a CIWA-Ar score of 13. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital, and symptom-triggered therapy for treatment of his alcohol withdrawal was used. The patient’s CIWA-Ar score peaked at 21 some 24 hours after his last drink. The patient otherwise had an uncomplicated four-day hospital course due to persistent nausea.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists unsure of which patients should be admitted for alcohol detoxification can use the PAWSS tool and an initial CIWA-Ar score to help determine a patient’s risk for developing complicated AWS. TH

Dr. Velasquez and Dr. Kornsawad are assistant professors and hospitalists at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Velasquez also serves as assistant professor and hospitalist at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System serving the San Antonio area.

References

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorder and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

- Lieber CS. Medical disorders of alcoholism. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1058-1065.

- Hasin SD, Stinson SF, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

- Whiteman PJ, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR. Alcoholism in the emergency department: an epidemiologic study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):14-20.

- Nielson SD, Storgarrd H, Moesgarrd F, Gluud C. Prevalence of alcohol problems among adult somatic in-patients of a Copenhagen hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29(5):583-590.

- Smothers BA, Yahr HT, Ruhl CE. Detection of alcohol use disorders in general hospital admissions in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(7):749-756.

- Dolman JM, Hawkes ND. Combining the audit questionnaire and biochemical markers to assess alcohol use and risk of alcohol withdrawal in medical inpatients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(6):515-519.

- Doering-Silveira J, Fidalgo TM, Nascimento CL, et al. Assessing alcohol dependence in hospitalized patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(6):5783-5791.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Das S, et al. Prospective validation study of the prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale (PAWSS) in medically ill inpatients: a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):509-518.

- Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

- Turner RC, Lichstein PR, Pedan Jr JG, Busher JT, Waivers LE. Alcohol withdrawal syndromes: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(5):432-444.

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492-501.

- Stehman CR, Mycyk MB. A rational approach to the treatment of alcohol withdrawal in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):734-742.

- Lee JH, Jang MK, Lee JY, et al. Clinical predictors for delirium tremens in alcohol dependence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(12):1833-1837.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375-390.

- Stephens JR, Liles AE, Dancel R, Gilchrist M, Kirsch J, DeWalt DA. Who needs inpatient detox? Development and implementation of a hospitalist protocol for the evaluation of patients for alcohol detoxification. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):587-593.

Case

A 42-year-old man with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypertension, and alcohol use disorder (AUD) presents to the ED requesting alcohol detoxification. He has had six admissions in the last six months for alcohol detoxification. Two years ago, the patient had a documented alcohol withdrawal seizure. His last drink was eight hours ago, and he currently drinks a liter of vodka a day. On exam, his pulse rate is 126 bpm, and his blood pressure is 162/91 mm Hg. He appears anxious and has bilateral hand tremors. His serum ethanol level is 388.6 mg/dL.

Overview

DSM-5 integrated alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence that were previously classified in DSM-IV into AUDs with mild, moderate, and severe subclassifications. AUDs are the most serious substance abuse problem in the U.S. In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse is 17.8% and of alcohol dependence is 12.5%.1–3 One study estimates that 24% of adult patients brought to the ED by ambulance suffer from alcoholism, and approximately 10% to 32% of hospitalized medical patients have an AUD.4–8 Patients who stop drinking will develop alcohol withdrawal as early as six hours after their last drink (see Figure 1). The majority of patients at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) will develop only minor uncomplicated symptoms, but up to 20% will develop symptoms associated with complicated AWS, including withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens (DT).9 It is not entirely clear why some individuals suffer from more severe withdrawal symptoms than others, but genetic predisposition may play a role.10

DT is a syndrome characterized by agitation, disorientation, hallucinations, and autonomic instability (tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis) in the setting of acute reduction or abstinence from alcohol and is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%.11 Complicated AWS is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality, longer lengths of stay, inflated costs of care, increased burden and frustration of nursing and medical staff, and worse cognitive functioning.9 In 80% of cases, the symptoms of uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal do not require aggressive medical intervention and usually disappear within two to seven days of the last drink.12 Physicians making triage decisions for patients who present to the ED in need of detoxification face a difficult dilemma concerning inpatient versus outpatient treatment.

Review of the Data

The literature on both inpatient and outpatient management and treatment of AWS is well-described. Currently, there are no guidelines or consensus on whether to admit patients with alcohol abuse syndromes to the hospital when the request for detoxification is made. Admission should be considered for all patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal who present to the ED.13 Patients with mild AWS may be discharged if they do not require admission for an additional medical condition, but patients experiencing moderate to severe withdrawal require admission for monitoring and treatment. Many physicians use a simple assessment of past history of DT and pulse rate, which may be easily evaluated in clinical settings, to readily identify patients who are at high risk of developing DT during an alcohol dependence period.14

Since 1978, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) has been consistently used for both monitoring patients with alcohol withdrawal and for making an initial assessment. CIWA-Ar was developed as a revised scale and is frequently used to monitor the severity of ongoing alcohol withdrawal and the response to treatment for the clinical care of patients in alcohol withdrawal (see Figure 2). CIWA-Ar was not developed to identify patients at risk for AWS but is frequently used to determine if patients require admission to the hospital for detoxification.15 Patients with CIWA-Ar scores > 15 require inpatient detoxification. Patients with scores between 8 and 15 should be admitted if they have a history of prior seizures or DT but could otherwise be considered for outpatient detoxification. Patients with scores < 8, which are considered mild alcohol withdrawal, can likely be safely treated as outpatients unless they have a history of DT or alcohol withdrawal seizures.16 Because symptoms of severe alcohol withdrawal are often not present for more than six hours after the patient’s last drink, or often longer, CIWA-Ar is limited and does not identify patients who are otherwise at high risk for complicated withdrawal. A protocol was developed incorporating the patient’s history of alcohol withdrawal seizure, DT, and the CIWA to evaluate the outcome of outpatient versus inpatient detoxification.16

The most promising tool to screen patients for AWS was developed recently by researchers at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif., using an extensive systematic literature search to identify evidence-based clinical factors associated with the development of AWS.15 The Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) was subsequently constructed from 10 items correlating with complicated AWS (see Figure 3). When using a PAWSS score cutoff of ≥ 4, the predictive value of identifying a patient who is at risk for complicated withdrawal is significantly increased to 93.1%. This tool has only been used in medically ill patients but could be extrapolated for use in patients who present to an acute-care setting requesting inpatient detoxification.

Patients presenting to the ED with alcohol withdrawal seizures have been shown to have an associated 35% risk of progression to DT when found to have a low platelet count, low blood pyridoxine, and a high blood level of homocysteine. In another retrospective cohort study in Hepatology, three clinical features were identified to be associated with an increased risk for DT: alcohol dependence, a prior history of DT, and a higher pulse rate at admission (> 100 bpm).14

Instructions for the assessment of the patient who requests detoxification are as follows:

- A patient whose last drink of alcohol was more than five days ago and who shows no signs of withdrawal is unlikely to develop significant withdrawal symptoms and does not require inpatient detoxification.

- Other medical and psychiatric conditions should be evaluated for admission including alcohol use disorder complications.

- Calculate CIWA-Ar score:

Scores < 8 may not need detoxification; consider calculating PAWSS score.

Scores of 8 to 15 without symptoms of DT or seizures can be treated as an outpatient detoxification if no contraindication.

Scores of ≥ 15 should be admitted to the hospital.

- Calculate PAWSS score:

Scores ≥ 4 suggest high risk for moderate to severe complicated AWS, and admission should be considered.

Scores < 4 suggest lower risk for complicated AWS, and outpatient treatment should be considered if patients do not have a medical or surgical diagnosis requiring admission.

Back to the Case

At the time of his presentation, the patient was beginning to show signs of early withdrawal symptoms, including tremor and tachycardia, despite having an elevated blood alcohol level. This patient had a PAWSS score of 6, placing him at increased risk of complicated AWS, and a CIWA-Ar score of 13. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital, and symptom-triggered therapy for treatment of his alcohol withdrawal was used. The patient’s CIWA-Ar score peaked at 21 some 24 hours after his last drink. The patient otherwise had an uncomplicated four-day hospital course due to persistent nausea.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists unsure of which patients should be admitted for alcohol detoxification can use the PAWSS tool and an initial CIWA-Ar score to help determine a patient’s risk for developing complicated AWS. TH

Dr. Velasquez and Dr. Kornsawad are assistant professors and hospitalists at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Velasquez also serves as assistant professor and hospitalist at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System serving the San Antonio area.

References

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorder and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

- Lieber CS. Medical disorders of alcoholism. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1058-1065.

- Hasin SD, Stinson SF, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

- Whiteman PJ, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR. Alcoholism in the emergency department: an epidemiologic study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):14-20.

- Nielson SD, Storgarrd H, Moesgarrd F, Gluud C. Prevalence of alcohol problems among adult somatic in-patients of a Copenhagen hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29(5):583-590.

- Smothers BA, Yahr HT, Ruhl CE. Detection of alcohol use disorders in general hospital admissions in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(7):749-756.

- Dolman JM, Hawkes ND. Combining the audit questionnaire and biochemical markers to assess alcohol use and risk of alcohol withdrawal in medical inpatients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(6):515-519.

- Doering-Silveira J, Fidalgo TM, Nascimento CL, et al. Assessing alcohol dependence in hospitalized patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(6):5783-5791.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Das S, et al. Prospective validation study of the prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale (PAWSS) in medically ill inpatients: a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):509-518.

- Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

- Turner RC, Lichstein PR, Pedan Jr JG, Busher JT, Waivers LE. Alcohol withdrawal syndromes: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(5):432-444.

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492-501.

- Stehman CR, Mycyk MB. A rational approach to the treatment of alcohol withdrawal in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):734-742.

- Lee JH, Jang MK, Lee JY, et al. Clinical predictors for delirium tremens in alcohol dependence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(12):1833-1837.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375-390.

- Stephens JR, Liles AE, Dancel R, Gilchrist M, Kirsch J, DeWalt DA. Who needs inpatient detox? Development and implementation of a hospitalist protocol for the evaluation of patients for alcohol detoxification. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):587-593.

Case

A 42-year-old man with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypertension, and alcohol use disorder (AUD) presents to the ED requesting alcohol detoxification. He has had six admissions in the last six months for alcohol detoxification. Two years ago, the patient had a documented alcohol withdrawal seizure. His last drink was eight hours ago, and he currently drinks a liter of vodka a day. On exam, his pulse rate is 126 bpm, and his blood pressure is 162/91 mm Hg. He appears anxious and has bilateral hand tremors. His serum ethanol level is 388.6 mg/dL.

Overview

DSM-5 integrated alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence that were previously classified in DSM-IV into AUDs with mild, moderate, and severe subclassifications. AUDs are the most serious substance abuse problem in the U.S. In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse is 17.8% and of alcohol dependence is 12.5%.1–3 One study estimates that 24% of adult patients brought to the ED by ambulance suffer from alcoholism, and approximately 10% to 32% of hospitalized medical patients have an AUD.4–8 Patients who stop drinking will develop alcohol withdrawal as early as six hours after their last drink (see Figure 1). The majority of patients at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) will develop only minor uncomplicated symptoms, but up to 20% will develop symptoms associated with complicated AWS, including withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens (DT).9 It is not entirely clear why some individuals suffer from more severe withdrawal symptoms than others, but genetic predisposition may play a role.10

DT is a syndrome characterized by agitation, disorientation, hallucinations, and autonomic instability (tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis) in the setting of acute reduction or abstinence from alcohol and is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%.11 Complicated AWS is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality, longer lengths of stay, inflated costs of care, increased burden and frustration of nursing and medical staff, and worse cognitive functioning.9 In 80% of cases, the symptoms of uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal do not require aggressive medical intervention and usually disappear within two to seven days of the last drink.12 Physicians making triage decisions for patients who present to the ED in need of detoxification face a difficult dilemma concerning inpatient versus outpatient treatment.

Review of the Data

The literature on both inpatient and outpatient management and treatment of AWS is well-described. Currently, there are no guidelines or consensus on whether to admit patients with alcohol abuse syndromes to the hospital when the request for detoxification is made. Admission should be considered for all patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal who present to the ED.13 Patients with mild AWS may be discharged if they do not require admission for an additional medical condition, but patients experiencing moderate to severe withdrawal require admission for monitoring and treatment. Many physicians use a simple assessment of past history of DT and pulse rate, which may be easily evaluated in clinical settings, to readily identify patients who are at high risk of developing DT during an alcohol dependence period.14

Since 1978, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) has been consistently used for both monitoring patients with alcohol withdrawal and for making an initial assessment. CIWA-Ar was developed as a revised scale and is frequently used to monitor the severity of ongoing alcohol withdrawal and the response to treatment for the clinical care of patients in alcohol withdrawal (see Figure 2). CIWA-Ar was not developed to identify patients at risk for AWS but is frequently used to determine if patients require admission to the hospital for detoxification.15 Patients with CIWA-Ar scores > 15 require inpatient detoxification. Patients with scores between 8 and 15 should be admitted if they have a history of prior seizures or DT but could otherwise be considered for outpatient detoxification. Patients with scores < 8, which are considered mild alcohol withdrawal, can likely be safely treated as outpatients unless they have a history of DT or alcohol withdrawal seizures.16 Because symptoms of severe alcohol withdrawal are often not present for more than six hours after the patient’s last drink, or often longer, CIWA-Ar is limited and does not identify patients who are otherwise at high risk for complicated withdrawal. A protocol was developed incorporating the patient’s history of alcohol withdrawal seizure, DT, and the CIWA to evaluate the outcome of outpatient versus inpatient detoxification.16

The most promising tool to screen patients for AWS was developed recently by researchers at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif., using an extensive systematic literature search to identify evidence-based clinical factors associated with the development of AWS.15 The Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) was subsequently constructed from 10 items correlating with complicated AWS (see Figure 3). When using a PAWSS score cutoff of ≥ 4, the predictive value of identifying a patient who is at risk for complicated withdrawal is significantly increased to 93.1%. This tool has only been used in medically ill patients but could be extrapolated for use in patients who present to an acute-care setting requesting inpatient detoxification.

Patients presenting to the ED with alcohol withdrawal seizures have been shown to have an associated 35% risk of progression to DT when found to have a low platelet count, low blood pyridoxine, and a high blood level of homocysteine. In another retrospective cohort study in Hepatology, three clinical features were identified to be associated with an increased risk for DT: alcohol dependence, a prior history of DT, and a higher pulse rate at admission (> 100 bpm).14

Instructions for the assessment of the patient who requests detoxification are as follows:

- A patient whose last drink of alcohol was more than five days ago and who shows no signs of withdrawal is unlikely to develop significant withdrawal symptoms and does not require inpatient detoxification.

- Other medical and psychiatric conditions should be evaluated for admission including alcohol use disorder complications.

- Calculate CIWA-Ar score:

Scores < 8 may not need detoxification; consider calculating PAWSS score.

Scores of 8 to 15 without symptoms of DT or seizures can be treated as an outpatient detoxification if no contraindication.

Scores of ≥ 15 should be admitted to the hospital.

- Calculate PAWSS score:

Scores ≥ 4 suggest high risk for moderate to severe complicated AWS, and admission should be considered.

Scores < 4 suggest lower risk for complicated AWS, and outpatient treatment should be considered if patients do not have a medical or surgical diagnosis requiring admission.

Back to the Case

At the time of his presentation, the patient was beginning to show signs of early withdrawal symptoms, including tremor and tachycardia, despite having an elevated blood alcohol level. This patient had a PAWSS score of 6, placing him at increased risk of complicated AWS, and a CIWA-Ar score of 13. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital, and symptom-triggered therapy for treatment of his alcohol withdrawal was used. The patient’s CIWA-Ar score peaked at 21 some 24 hours after his last drink. The patient otherwise had an uncomplicated four-day hospital course due to persistent nausea.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists unsure of which patients should be admitted for alcohol detoxification can use the PAWSS tool and an initial CIWA-Ar score to help determine a patient’s risk for developing complicated AWS. TH

Dr. Velasquez and Dr. Kornsawad are assistant professors and hospitalists at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Velasquez also serves as assistant professor and hospitalist at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System serving the San Antonio area.

References

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorder and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

- Lieber CS. Medical disorders of alcoholism. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1058-1065.

- Hasin SD, Stinson SF, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

- Whiteman PJ, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR. Alcoholism in the emergency department: an epidemiologic study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):14-20.

- Nielson SD, Storgarrd H, Moesgarrd F, Gluud C. Prevalence of alcohol problems among adult somatic in-patients of a Copenhagen hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29(5):583-590.

- Smothers BA, Yahr HT, Ruhl CE. Detection of alcohol use disorders in general hospital admissions in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(7):749-756.

- Dolman JM, Hawkes ND. Combining the audit questionnaire and biochemical markers to assess alcohol use and risk of alcohol withdrawal in medical inpatients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(6):515-519.

- Doering-Silveira J, Fidalgo TM, Nascimento CL, et al. Assessing alcohol dependence in hospitalized patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(6):5783-5791.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Das S, et al. Prospective validation study of the prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale (PAWSS) in medically ill inpatients: a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):509-518.

- Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

- Turner RC, Lichstein PR, Pedan Jr JG, Busher JT, Waivers LE. Alcohol withdrawal syndromes: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(5):432-444.

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492-501.

- Stehman CR, Mycyk MB. A rational approach to the treatment of alcohol withdrawal in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):734-742.

- Lee JH, Jang MK, Lee JY, et al. Clinical predictors for delirium tremens in alcohol dependence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(12):1833-1837.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375-390.

- Stephens JR, Liles AE, Dancel R, Gilchrist M, Kirsch J, DeWalt DA. Who needs inpatient detox? Development and implementation of a hospitalist protocol for the evaluation of patients for alcohol detoxification. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):587-593.

HM16 Session Analysis: Medical, Behavioral Management of Eating Disorders

Presenter: Kyung E. Rhee, MD, MSc, MA

Summary: Eating disorders (ED) are common and have significant morbidity and mortality. EDs are the third most common psychiatric disorder of adolescents with a prevalence of 0.5-2% for anorexia and 0.9-3% for bulimia; 90% of patients are female. Mortality rate can be as high as 10% for anorexia and 1% for bulimia. Diagnosis is formally guided by DSM 5 criteria, but the mnemonic SCOFF can be useful:

- Do you feel or make yourself SICK when eating?

- Do you feel you’ve lost CONTROL of your eating?

- Have you lost one STONE (14 lbs. developed by the British) of weight?

- Do you feel FAT?

- Does FOOD dominate your life?

A detailed history is needed as patients with ED may engage in secretive behaviors to hide their illness. After diagnosis, treatment may be outpatient or inpatient. Medical issues hospitalists are likely to see with inpatients include re-feeding syndrome, various metabolic disturbances, secondary amenorrhea, sleep disturbances, and for patients with bulimia, evidence of dental or esophageal trauma from purging. Differential diagnoses include: IBD, thyroid disease, celiac, diabetes, and Addison’s disease.

Hospitalists’ role in treatment is as part of a multidisciplinary group to manage the medical complications. Inpatient management includes individual and group therapy, monitored group meals, daily blind weights, bathroom visits, and focused lab studies. There is no “cure” and only ~50% of patients are free of ongoing symptoms after treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Eating disorders are common in adolescent females and have significant morbidity and mortality.

- Hospitalists’ role is diagnosis via careful history and management of medical complications with an eating disorder team. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Kyung E. Rhee, MD, MSc, MA

Summary: Eating disorders (ED) are common and have significant morbidity and mortality. EDs are the third most common psychiatric disorder of adolescents with a prevalence of 0.5-2% for anorexia and 0.9-3% for bulimia; 90% of patients are female. Mortality rate can be as high as 10% for anorexia and 1% for bulimia. Diagnosis is formally guided by DSM 5 criteria, but the mnemonic SCOFF can be useful:

- Do you feel or make yourself SICK when eating?

- Do you feel you’ve lost CONTROL of your eating?

- Have you lost one STONE (14 lbs. developed by the British) of weight?

- Do you feel FAT?

- Does FOOD dominate your life?

A detailed history is needed as patients with ED may engage in secretive behaviors to hide their illness. After diagnosis, treatment may be outpatient or inpatient. Medical issues hospitalists are likely to see with inpatients include re-feeding syndrome, various metabolic disturbances, secondary amenorrhea, sleep disturbances, and for patients with bulimia, evidence of dental or esophageal trauma from purging. Differential diagnoses include: IBD, thyroid disease, celiac, diabetes, and Addison’s disease.

Hospitalists’ role in treatment is as part of a multidisciplinary group to manage the medical complications. Inpatient management includes individual and group therapy, monitored group meals, daily blind weights, bathroom visits, and focused lab studies. There is no “cure” and only ~50% of patients are free of ongoing symptoms after treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Eating disorders are common in adolescent females and have significant morbidity and mortality.

- Hospitalists’ role is diagnosis via careful history and management of medical complications with an eating disorder team. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Kyung E. Rhee, MD, MSc, MA

Summary: Eating disorders (ED) are common and have significant morbidity and mortality. EDs are the third most common psychiatric disorder of adolescents with a prevalence of 0.5-2% for anorexia and 0.9-3% for bulimia; 90% of patients are female. Mortality rate can be as high as 10% for anorexia and 1% for bulimia. Diagnosis is formally guided by DSM 5 criteria, but the mnemonic SCOFF can be useful:

- Do you feel or make yourself SICK when eating?

- Do you feel you’ve lost CONTROL of your eating?

- Have you lost one STONE (14 lbs. developed by the British) of weight?

- Do you feel FAT?

- Does FOOD dominate your life?

A detailed history is needed as patients with ED may engage in secretive behaviors to hide their illness. After diagnosis, treatment may be outpatient or inpatient. Medical issues hospitalists are likely to see with inpatients include re-feeding syndrome, various metabolic disturbances, secondary amenorrhea, sleep disturbances, and for patients with bulimia, evidence of dental or esophageal trauma from purging. Differential diagnoses include: IBD, thyroid disease, celiac, diabetes, and Addison’s disease.

Hospitalists’ role in treatment is as part of a multidisciplinary group to manage the medical complications. Inpatient management includes individual and group therapy, monitored group meals, daily blind weights, bathroom visits, and focused lab studies. There is no “cure” and only ~50% of patients are free of ongoing symptoms after treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Eating disorders are common in adolescent females and have significant morbidity and mortality.

- Hospitalists’ role is diagnosis via careful history and management of medical complications with an eating disorder team. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

HM16 Session Analysis: Stay Calm, Safe During Inpatient Behavioral Emergencies

Presenters: David Pressel, MD, PhD, FAAP, FHM, Emily Fingado, MD, FAAP, and Jessica Tomaszewski, MD, FAAP

Summary: Patients may engage in violent behaviors that pose a danger to themselves or others. Behavioral emergencies may be rare, can be dangerous, and staff may feel ill-trained to respond appropriately. Patients with ingestions, or underlying psychiatric or developmental difficulties, are at highest risk for developing a behavioral emergency.

The first strategy in handling a potentially violent patient is de-escalation, i.e., trying to identify and rectify the behavioral trigger. If de-escalation is not successful, personal safety is paramount. Get away from the patient and get help. If a patient needs to be physically restrained, minimally there should be one staff member per limb. Various physical devices, including soft restraints, four-point leathers, hand mittens, and spit hoods may be used to control a violent patient. A violent restraint is characterized by the indication, not the device. Medications may be used to treat the underlying mental health issue and should not be used as PRN chemical restraints.

After a violent patient is safely restrained, further steps need to be taken, including notification of the attending or legal guardian if a minor; documentation of the event, including a debrief of what occurred; a room sweep to ensure securing any dangerous items (metal eating utensils); and modification of the care plan to strategize on removal of the restraints as soon as is safe.

Hospitals should view behavioral emergencies similarly to a Code Blue. Have a specialized team that responds and undergoes regular training.

Key Takeaways

- Behavioral emergencies occur when a patient becomes violent.

- De-escalation is the best response.

- If not successful, maintain personal safety, control and medicate the patient as appropriate, and document clearly. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenters: David Pressel, MD, PhD, FAAP, FHM, Emily Fingado, MD, FAAP, and Jessica Tomaszewski, MD, FAAP

Summary: Patients may engage in violent behaviors that pose a danger to themselves or others. Behavioral emergencies may be rare, can be dangerous, and staff may feel ill-trained to respond appropriately. Patients with ingestions, or underlying psychiatric or developmental difficulties, are at highest risk for developing a behavioral emergency.

The first strategy in handling a potentially violent patient is de-escalation, i.e., trying to identify and rectify the behavioral trigger. If de-escalation is not successful, personal safety is paramount. Get away from the patient and get help. If a patient needs to be physically restrained, minimally there should be one staff member per limb. Various physical devices, including soft restraints, four-point leathers, hand mittens, and spit hoods may be used to control a violent patient. A violent restraint is characterized by the indication, not the device. Medications may be used to treat the underlying mental health issue and should not be used as PRN chemical restraints.

After a violent patient is safely restrained, further steps need to be taken, including notification of the attending or legal guardian if a minor; documentation of the event, including a debrief of what occurred; a room sweep to ensure securing any dangerous items (metal eating utensils); and modification of the care plan to strategize on removal of the restraints as soon as is safe.

Hospitals should view behavioral emergencies similarly to a Code Blue. Have a specialized team that responds and undergoes regular training.

Key Takeaways

- Behavioral emergencies occur when a patient becomes violent.

- De-escalation is the best response.

- If not successful, maintain personal safety, control and medicate the patient as appropriate, and document clearly. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenters: David Pressel, MD, PhD, FAAP, FHM, Emily Fingado, MD, FAAP, and Jessica Tomaszewski, MD, FAAP

Summary: Patients may engage in violent behaviors that pose a danger to themselves or others. Behavioral emergencies may be rare, can be dangerous, and staff may feel ill-trained to respond appropriately. Patients with ingestions, or underlying psychiatric or developmental difficulties, are at highest risk for developing a behavioral emergency.

The first strategy in handling a potentially violent patient is de-escalation, i.e., trying to identify and rectify the behavioral trigger. If de-escalation is not successful, personal safety is paramount. Get away from the patient and get help. If a patient needs to be physically restrained, minimally there should be one staff member per limb. Various physical devices, including soft restraints, four-point leathers, hand mittens, and spit hoods may be used to control a violent patient. A violent restraint is characterized by the indication, not the device. Medications may be used to treat the underlying mental health issue and should not be used as PRN chemical restraints.

After a violent patient is safely restrained, further steps need to be taken, including notification of the attending or legal guardian if a minor; documentation of the event, including a debrief of what occurred; a room sweep to ensure securing any dangerous items (metal eating utensils); and modification of the care plan to strategize on removal of the restraints as soon as is safe.

Hospitals should view behavioral emergencies similarly to a Code Blue. Have a specialized team that responds and undergoes regular training.

Key Takeaways

- Behavioral emergencies occur when a patient becomes violent.

- De-escalation is the best response.

- If not successful, maintain personal safety, control and medicate the patient as appropriate, and document clearly. TH

Dr. Pressel is a pediatric hospitalist and inpatient medical director at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

HM16 Session Analysis: Update in Pulmonary Medicine

Presenter: Daniel D. Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM

Summary: This presentation focused on pulmonary updates specific to hospitalist practice, from end of 2014 to early 2016.

New research on community-acquired pneumonia suggest that only 38% of cases a presumptive pathogen will be isolated. Virus account for 23%, bacteria 11% (including S. pneumonia, S. Aureus and Enterobacteriaceae), both (virus and bacteria) 3%, and fungus or mycobacterium 1%. It is important to notice no recent data on etiology was available since mid-1990.

There is also a new pragmatic trial suggesting that B-lactam monotherapy is not inferior to either B-lactam in combination with macrolides or fluoroquinolones. The study reported an 11%, 90-day mortality with B-lactam monotherapy compared with 11% when combined with macrolides and 8.8% when using quinolones monotherapy.

Update evidence supports the use of corticosteroids for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia, at a dose of 20-60 mg day for 5-7 days. The study showed decreased mortality in patients with clinical criteria for severe pneumonia with NNT 7; it also showed decrease need for mechanical ventilation and development of ARDS.

An additional, interesting finding was a decrease in length of stay (LOS) in the steroid group. In patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, high flow nasal cannula reduced mortality and likely reduces intubation in severely hypoxemic patients when compared to NPPV.

In patients with first unprovoked VTE, extending anticoagulation to two years or adding aspirin after initial anticoagulation might reduce recurrent VTE without significant increasing in risk for major bleeding.

Key Takeaways:

- B-lactam monotherapy for hospitalized non-ICU CAP might be reasonable choice.

- Moderate short course of steroids in CAP, reduce ARDS, intubation, LOS in all hospitalized patients (and mortality on severe CAP)

- A trial of high flow NC is indicated in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure

- Aspirin prophylaxis following anticoagulation (most benefit first year), or extended anticoagulation for 2 years reduce recurrent VTE without much additional bleeding risk.

Dr. Villagra is a hospitalist in Batesville, Ark., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Daniel D. Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM

Summary: This presentation focused on pulmonary updates specific to hospitalist practice, from end of 2014 to early 2016.

New research on community-acquired pneumonia suggest that only 38% of cases a presumptive pathogen will be isolated. Virus account for 23%, bacteria 11% (including S. pneumonia, S. Aureus and Enterobacteriaceae), both (virus and bacteria) 3%, and fungus or mycobacterium 1%. It is important to notice no recent data on etiology was available since mid-1990.

There is also a new pragmatic trial suggesting that B-lactam monotherapy is not inferior to either B-lactam in combination with macrolides or fluoroquinolones. The study reported an 11%, 90-day mortality with B-lactam monotherapy compared with 11% when combined with macrolides and 8.8% when using quinolones monotherapy.

Update evidence supports the use of corticosteroids for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia, at a dose of 20-60 mg day for 5-7 days. The study showed decreased mortality in patients with clinical criteria for severe pneumonia with NNT 7; it also showed decrease need for mechanical ventilation and development of ARDS.

An additional, interesting finding was a decrease in length of stay (LOS) in the steroid group. In patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, high flow nasal cannula reduced mortality and likely reduces intubation in severely hypoxemic patients when compared to NPPV.

In patients with first unprovoked VTE, extending anticoagulation to two years or adding aspirin after initial anticoagulation might reduce recurrent VTE without significant increasing in risk for major bleeding.

Key Takeaways:

- B-lactam monotherapy for hospitalized non-ICU CAP might be reasonable choice.

- Moderate short course of steroids in CAP, reduce ARDS, intubation, LOS in all hospitalized patients (and mortality on severe CAP)

- A trial of high flow NC is indicated in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure

- Aspirin prophylaxis following anticoagulation (most benefit first year), or extended anticoagulation for 2 years reduce recurrent VTE without much additional bleeding risk.

Dr. Villagra is a hospitalist in Batesville, Ark., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

Presenter: Daniel D. Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM

Summary: This presentation focused on pulmonary updates specific to hospitalist practice, from end of 2014 to early 2016.

New research on community-acquired pneumonia suggest that only 38% of cases a presumptive pathogen will be isolated. Virus account for 23%, bacteria 11% (including S. pneumonia, S. Aureus and Enterobacteriaceae), both (virus and bacteria) 3%, and fungus or mycobacterium 1%. It is important to notice no recent data on etiology was available since mid-1990.

There is also a new pragmatic trial suggesting that B-lactam monotherapy is not inferior to either B-lactam in combination with macrolides or fluoroquinolones. The study reported an 11%, 90-day mortality with B-lactam monotherapy compared with 11% when combined with macrolides and 8.8% when using quinolones monotherapy.

Update evidence supports the use of corticosteroids for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia, at a dose of 20-60 mg day for 5-7 days. The study showed decreased mortality in patients with clinical criteria for severe pneumonia with NNT 7; it also showed decrease need for mechanical ventilation and development of ARDS.

An additional, interesting finding was a decrease in length of stay (LOS) in the steroid group. In patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, high flow nasal cannula reduced mortality and likely reduces intubation in severely hypoxemic patients when compared to NPPV.

In patients with first unprovoked VTE, extending anticoagulation to two years or adding aspirin after initial anticoagulation might reduce recurrent VTE without significant increasing in risk for major bleeding.

Key Takeaways:

- B-lactam monotherapy for hospitalized non-ICU CAP might be reasonable choice.

- Moderate short course of steroids in CAP, reduce ARDS, intubation, LOS in all hospitalized patients (and mortality on severe CAP)

- A trial of high flow NC is indicated in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure

- Aspirin prophylaxis following anticoagulation (most benefit first year), or extended anticoagulation for 2 years reduce recurrent VTE without much additional bleeding risk.

Dr. Villagra is a hospitalist in Batesville, Ark., and a member of Team Hospitalist.

HM16 Session Analysis: Infectious Disease Emergencies: Three Diagnoses You Can’t Afford to Miss

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

Presenter: Jim Pile, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Summary: The following three infectious diagnoses are relatively uncommon but important not to miss as they are associated with high mortality, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Remembering these key points can help you make the diagnosis:

- Bacterial meningitis: Many patients do not have the classic triad—fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status—but nearly all have at least one of these signs, and most have headache. The jolt accentuation test—horizontal movement of the head causing exacerbation of the headache—is more sensitive than nuchal rigidity in these cases. Diagnosis is confirmed by lumbar puncture. It appears safe to not to perform head CT in patients

- Spinal epidural abscess: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, hemodialysis, UTI, trauma, epidural anesthesia, trauma/surgery. Presentation is acute to indolent and usually consists of four stages: central back pain, radicular pain, neurologic deficits, paralysis; fever variable. Checking ESR can be helpful as it is elevated in most cases. MRI is imaging study of choice. Initial management includes antibiotics to coverage Staph Aureus and gram negative rods and surgery consultation.

- Necrotizing soft tissue infection: Risk factors include DM, IV drug use, trauma/surgery, ETOH, immunosuppression (Type I); muscle trauma, skin integrity deficits (Type II). Clinical suspicion is paramount. Specific clues include: pain out of proportion, anesthesia, systemic toxicity, rapid progression, bullae/crepitus, and failure to respond to antibiotics. Initial management includes initiation of B-lactam/lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem plus clindamycin and MRSA coverage, imaging and prompt surgical consultation (as delayed/inadequate surgery associated with poor prognosis.

Key Takeaway

Clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, spinal epidural abscesses, and necrotizing soft tissue infections, and delays in diagnosis and treatment are associated with increased mortality.TH

QUIZ: Will My COPD Patient Benefit from Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NIPPV)?

[WpProQuiz 5]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 5]

[WpProQuiz 5]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 5]

[WpProQuiz 5]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 5]

Not Sleeping Enough Can Cause Serious Health Issues

ATLANTA (Reuters) - Did you get enough sleep last night? If not, you are not alone. More than one out of three American adults do not get enough sleep, according to a study released Thursday from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"That's a big problem," says Dr. Nancy Collop, director of the Emory Sleep Center at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, who is familiar with the study. "You don't function as well, your ability to pay attention is reduced, and it can have serious, long term side effects. It can change your metabolism for the worse."

At least seven hours of sleep is considered healthy for an adults aged 18 to 60, according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society. The CDC analyzed data from a 2014 survey of 444,306 adults and found roughly 65% of respondents reported getting that amount of

sleep.

"Lifestyle changes such as going to bed at the same time each night; rising at the same time each morning; and turning off or removing televisions, computers, mobile devices from the bedroom, can help people get the healthy sleep they need," said Dr. Wayne Giles, director of the CDC's Division of Population Health, in a statement.

Getting less than seven hours a night is associated with an increased risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke and frequent mental distress, the study shows. Published in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the study is the first of its kind to look at all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

The study found that among those most likely to get great sleep were married or have a job, with 67% and 65%, respectively saying they get enough. Only 56% of divorced adults said they get enough sleep, and just over half of jobless adults sleep seven hours a night regularly. Among the best sleepers were college graduates, with 72% reporting seven hours or more.

The study found geographical differences as well as ethnic disparities. Hawaiian residents get less sleep than those living in South Dakota, the study found. Non-Hispanic whites sleep better than non-Hispanic black residents, with 67% and 54%, respectively.

ATLANTA (Reuters) - Did you get enough sleep last night? If not, you are not alone. More than one out of three American adults do not get enough sleep, according to a study released Thursday from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"That's a big problem," says Dr. Nancy Collop, director of the Emory Sleep Center at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, who is familiar with the study. "You don't function as well, your ability to pay attention is reduced, and it can have serious, long term side effects. It can change your metabolism for the worse."

At least seven hours of sleep is considered healthy for an adults aged 18 to 60, according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society. The CDC analyzed data from a 2014 survey of 444,306 adults and found roughly 65% of respondents reported getting that amount of

sleep.

"Lifestyle changes such as going to bed at the same time each night; rising at the same time each morning; and turning off or removing televisions, computers, mobile devices from the bedroom, can help people get the healthy sleep they need," said Dr. Wayne Giles, director of the CDC's Division of Population Health, in a statement.

Getting less than seven hours a night is associated with an increased risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke and frequent mental distress, the study shows. Published in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the study is the first of its kind to look at all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

The study found that among those most likely to get great sleep were married or have a job, with 67% and 65%, respectively saying they get enough. Only 56% of divorced adults said they get enough sleep, and just over half of jobless adults sleep seven hours a night regularly. Among the best sleepers were college graduates, with 72% reporting seven hours or more.

The study found geographical differences as well as ethnic disparities. Hawaiian residents get less sleep than those living in South Dakota, the study found. Non-Hispanic whites sleep better than non-Hispanic black residents, with 67% and 54%, respectively.

ATLANTA (Reuters) - Did you get enough sleep last night? If not, you are not alone. More than one out of three American adults do not get enough sleep, according to a study released Thursday from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"That's a big problem," says Dr. Nancy Collop, director of the Emory Sleep Center at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, who is familiar with the study. "You don't function as well, your ability to pay attention is reduced, and it can have serious, long term side effects. It can change your metabolism for the worse."

At least seven hours of sleep is considered healthy for an adults aged 18 to 60, according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society. The CDC analyzed data from a 2014 survey of 444,306 adults and found roughly 65% of respondents reported getting that amount of

sleep.

"Lifestyle changes such as going to bed at the same time each night; rising at the same time each morning; and turning off or removing televisions, computers, mobile devices from the bedroom, can help people get the healthy sleep they need," said Dr. Wayne Giles, director of the CDC's Division of Population Health, in a statement.

Getting less than seven hours a night is associated with an increased risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke and frequent mental distress, the study shows. Published in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the study is the first of its kind to look at all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

The study found that among those most likely to get great sleep were married or have a job, with 67% and 65%, respectively saying they get enough. Only 56% of divorced adults said they get enough sleep, and just over half of jobless adults sleep seven hours a night regularly. Among the best sleepers were college graduates, with 72% reporting seven hours or more.

The study found geographical differences as well as ethnic disparities. Hawaiian residents get less sleep than those living in South Dakota, the study found. Non-Hispanic whites sleep better than non-Hispanic black residents, with 67% and 54%, respectively.

Sharing Notes for Better Doctor-Patient Communication

Excellent communication between physicians and patients is a crucial element of hospital quality, but it’s also an ongoing challenge for many institutions. One physician wondered whether letting patients read their physicians’ notes could help.

“I wanted to find new methods to improve patient understanding of their medical care plan,” says Craig Weinert, MD, MPH, medical director for adult inpatient services at the University of Minnesota Medical Center and author of “Giving Doctors’ Daily Progress Notes to Hospitalized Patients and Families to Improve Patient Experience” in the American Journal of Medical Quality. “It seemed logical to me that giving patients access to the same information that all the other members of the healthcare team were reading would improve communication. This is the overall hypothesis of the Open Notes movement.”

Another reason Dr. Weinert pursued the study: In his clinical job as an intensivist, he encounters frequent disagreements with patients’ families regarding prognosis and goals of care.

“No one has figured out how to increase the alignment of prognosis between the family and the medical team,” Dr. Weinert says. “I think having the families read the doctors’ notes, where the issues with poor-prognosis multi-organ failure are repeatedly spelled out, might help families more quickly grasp the futility of continuing care.”

During the study, hospitalized patients or family members on six wards of a university hospital received a printed copy of their medical team’s daily progress notes. Surveys afterward showed 74% to 86% of patients and family members responded favorably. Physicians were mostly satisfied, too.

“Most doctors, at the end of the study, thought that Open Notes went better than they had predicted,” Dr. Weinert says.

Complete transparency of medical records is the future of medicine, he says. It’s what patients want, “especially the younger generation.”

“Over the next 10 years,” he says, “I predict ... all [electronic medical record] vendors will have electronic portals that allow clinic and hospitalized patients access to almost everything in the EMR.”

Reference

1. Weinert C. Giving doctors’ daily progress notes to hospitalized patients and families to improve patient experience. Am J Med Qual. 2015. doi:10.1177/1062860615610424.

Excellent communication between physicians and patients is a crucial element of hospital quality, but it’s also an ongoing challenge for many institutions. One physician wondered whether letting patients read their physicians’ notes could help.

“I wanted to find new methods to improve patient understanding of their medical care plan,” says Craig Weinert, MD, MPH, medical director for adult inpatient services at the University of Minnesota Medical Center and author of “Giving Doctors’ Daily Progress Notes to Hospitalized Patients and Families to Improve Patient Experience” in the American Journal of Medical Quality. “It seemed logical to me that giving patients access to the same information that all the other members of the healthcare team were reading would improve communication. This is the overall hypothesis of the Open Notes movement.”

Another reason Dr. Weinert pursued the study: In his clinical job as an intensivist, he encounters frequent disagreements with patients’ families regarding prognosis and goals of care.

“No one has figured out how to increase the alignment of prognosis between the family and the medical team,” Dr. Weinert says. “I think having the families read the doctors’ notes, where the issues with poor-prognosis multi-organ failure are repeatedly spelled out, might help families more quickly grasp the futility of continuing care.”

During the study, hospitalized patients or family members on six wards of a university hospital received a printed copy of their medical team’s daily progress notes. Surveys afterward showed 74% to 86% of patients and family members responded favorably. Physicians were mostly satisfied, too.

“Most doctors, at the end of the study, thought that Open Notes went better than they had predicted,” Dr. Weinert says.

Complete transparency of medical records is the future of medicine, he says. It’s what patients want, “especially the younger generation.”

“Over the next 10 years,” he says, “I predict ... all [electronic medical record] vendors will have electronic portals that allow clinic and hospitalized patients access to almost everything in the EMR.”

Reference

1. Weinert C. Giving doctors’ daily progress notes to hospitalized patients and families to improve patient experience. Am J Med Qual. 2015. doi:10.1177/1062860615610424.

Excellent communication between physicians and patients is a crucial element of hospital quality, but it’s also an ongoing challenge for many institutions. One physician wondered whether letting patients read their physicians’ notes could help.

“I wanted to find new methods to improve patient understanding of their medical care plan,” says Craig Weinert, MD, MPH, medical director for adult inpatient services at the University of Minnesota Medical Center and author of “Giving Doctors’ Daily Progress Notes to Hospitalized Patients and Families to Improve Patient Experience” in the American Journal of Medical Quality. “It seemed logical to me that giving patients access to the same information that all the other members of the healthcare team were reading would improve communication. This is the overall hypothesis of the Open Notes movement.”

Another reason Dr. Weinert pursued the study: In his clinical job as an intensivist, he encounters frequent disagreements with patients’ families regarding prognosis and goals of care.

“No one has figured out how to increase the alignment of prognosis between the family and the medical team,” Dr. Weinert says. “I think having the families read the doctors’ notes, where the issues with poor-prognosis multi-organ failure are repeatedly spelled out, might help families more quickly grasp the futility of continuing care.”

During the study, hospitalized patients or family members on six wards of a university hospital received a printed copy of their medical team’s daily progress notes. Surveys afterward showed 74% to 86% of patients and family members responded favorably. Physicians were mostly satisfied, too.

“Most doctors, at the end of the study, thought that Open Notes went better than they had predicted,” Dr. Weinert says.

Complete transparency of medical records is the future of medicine, he says. It’s what patients want, “especially the younger generation.”

“Over the next 10 years,” he says, “I predict ... all [electronic medical record] vendors will have electronic portals that allow clinic and hospitalized patients access to almost everything in the EMR.”

Reference

1. Weinert C. Giving doctors’ daily progress notes to hospitalized patients and families to improve patient experience. Am J Med Qual. 2015. doi:10.1177/1062860615610424.

New Study Shows PCMH Resulted in Positive Changes

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Implementation of a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) resulted in small changes in utilization patterns and modest quality improvements over a three-year period, according to a new report.

Dr. Lisa M. Kern of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and colleagues found more primary care visits, fewer specialist visits, fewer lab and radiologic tests, and fewer hospitalizations and rehospitalizations in the practices that adopted the PCMH.

Most changes occurred in the last year of the study, three years after PCMH implementation, they report in the Annals of Internal Medicine, online February 15.

The PCMH model "attempts to shift the medical paradigm from care for individual patients to care for populations, from care by physicians to care by a team of providers, from a focus on acute illness to an emphasis on chronic disease management, and from care at a single site to coordinated care across providers and settings," Dr. Kern and her team write. However, they add, studies looking at the effectiveness of the approach have had mixed results.

To date, most studies attempting to look at PCMH have had follow-up periods lasting just 1.5 to 2 years after implementation, the researchers note. "These changes take time, and studies with relatively short follow-up may have underestimated the effects of the intervention," they add.

The new study included 438 primary care physicians in 226 practices with more than 136,000 patients enrolled in five health plans. Insurers offered incentives of $2 to $10 per patient per month to practices that achieved level III PCMH recognition from the National Committee for Quality Assurance

(NCQA).

Twelve practices including 125 physicians volunteered for the PCMH initiative, and were assisted by two outside consulting groups. All of these practices achieved level III PCMH recognition. Among the remaining physicians, 87 doctors in 45 practices adopted electronic health records (EHR) without the

PCMH intervention, and 226 physicians in 169 practices continued using paper records.

For the eight quality measures the researchers looked at, two showed greater improvements over time in the PCMH group compared to one or both of the control groups: eye examination and hemoglobin A1c testing for patients with diabetes.

From 2008 to 2012, the PCMH group showed improvements over the paper group and the EHR group for six of seven utilization measures.

NCQA recognition was one aspect of the PCMH intervention in the new study, but this doesn't represent the entire intervention, Dr. Mark W. Friedberg of RAND Corporation and Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study, told Reuters Health.

"What they evaluated was a different way of paying practices, combined with some technical assistance, combined with some shared savings in the last year of the pilot," Dr. Friedberg explained. And this also requires defining what improving care means, he added, for example "better technical quality of care, better patient experience, better effectiveness of care, better professional satisfaction and lower burnout for people working in the practices. It's also hard to measure all of those, and most studies don't."

The new study is well done, according to Dr. Friedberg, but the challenge will be to understand how it fits in with the rest of the medical home literature, he said. "There's a lot of trials still out there and the results are still coming in, including some very large Medicare medical home pilots. I think we'll have a much better sense of what works in a year or two as those results come back."

Dr. Kern did not respond to an interview request by press time.

The study was funded by The Commonwealth Fund and the New York State Department of Health.

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - Implementation of a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) resulted in small changes in utilization patterns and modest quality improvements over a three-year period, according to a new report.

Dr. Lisa M. Kern of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and colleagues found more primary care visits, fewer specialist visits, fewer lab and radiologic tests, and fewer hospitalizations and rehospitalizations in the practices that adopted the PCMH.

Most changes occurred in the last year of the study, three years after PCMH implementation, they report in the Annals of Internal Medicine, online February 15.

The PCMH model "attempts to shift the medical paradigm from care for individual patients to care for populations, from care by physicians to care by a team of providers, from a focus on acute illness to an emphasis on chronic disease management, and from care at a single site to coordinated care across providers and settings," Dr. Kern and her team write. However, they add, studies looking at the effectiveness of the approach have had mixed results.

To date, most studies attempting to look at PCMH have had follow-up periods lasting just 1.5 to 2 years after implementation, the researchers note. "These changes take time, and studies with relatively short follow-up may have underestimated the effects of the intervention," they add.

The new study included 438 primary care physicians in 226 practices with more than 136,000 patients enrolled in five health plans. Insurers offered incentives of $2 to $10 per patient per month to practices that achieved level III PCMH recognition from the National Committee for Quality Assurance

(NCQA).

Twelve practices including 125 physicians volunteered for the PCMH initiative, and were assisted by two outside consulting groups. All of these practices achieved level III PCMH recognition. Among the remaining physicians, 87 doctors in 45 practices adopted electronic health records (EHR) without the