User login

‘Update in HM’ to highlight practice pearls

Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, and Cynthia Cooper, MD, hadn’t met in person until early 2018. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t spent a lot of time together.

Once a month, the two hospitalists checked in with one another through wide-ranging phone calls. Together, they have combed the medical literature and conferred over the past year, making long lists of candidate studies for the “Top 20” journal articles of the year for practicing hospitalists.

The two physicians will comoderate Tuesday’s “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, where they will summarize research findings of these “Top 20” articles. Their hope is to present research that each attendee can bring home to improve patient outcomes on a daily basis, while making for a smoother and more efficient practice.

Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said the presentations will not simply summarize study results but also will help attendees focus on the key findings – the clinical pearls – that represent real opportunities to update practice.

Since hospital medicine crosses so many disciplines, each physician said, in separate interviews, that doing justice to the literature has been time consuming and intellectually challenging – but worthwhile.

Dr. Cooper, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that, although she and Dr. Slawski practice in geographically diverse areas, their practice settings – academic medical centers – have many similarities. She said that, as she reviewed the medical literature over the past year, she gave considerable thought to the particular challenges and demands of hospitalists who practice in community hospitals and rural settings, where the level of support and access to subspecialty consults might be very different from the academic milieu.

“We hope that our unique approaches lend more breadth to the session,” said Dr. Slawski. “We want to make sure we have a good representation of SHM’s constituency, and that we present high-impact studies.”

To hit the mark of articles that are relevant for all, Dr. Cooper said she wants to make sure to focus on the practicalities of hospital-based practice – possible topics include prediction scores, hepatic encephalopathy, and the management of sepsis.

Neither Dr. Slawski nor Dr. Cooper reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Update in Hospital Medicine

Tuesday, 1:40-2:40 p.m.

Palms Ballroom

Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, and Cynthia Cooper, MD, hadn’t met in person until early 2018. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t spent a lot of time together.

Once a month, the two hospitalists checked in with one another through wide-ranging phone calls. Together, they have combed the medical literature and conferred over the past year, making long lists of candidate studies for the “Top 20” journal articles of the year for practicing hospitalists.

The two physicians will comoderate Tuesday’s “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, where they will summarize research findings of these “Top 20” articles. Their hope is to present research that each attendee can bring home to improve patient outcomes on a daily basis, while making for a smoother and more efficient practice.

Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said the presentations will not simply summarize study results but also will help attendees focus on the key findings – the clinical pearls – that represent real opportunities to update practice.

Since hospital medicine crosses so many disciplines, each physician said, in separate interviews, that doing justice to the literature has been time consuming and intellectually challenging – but worthwhile.

Dr. Cooper, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that, although she and Dr. Slawski practice in geographically diverse areas, their practice settings – academic medical centers – have many similarities. She said that, as she reviewed the medical literature over the past year, she gave considerable thought to the particular challenges and demands of hospitalists who practice in community hospitals and rural settings, where the level of support and access to subspecialty consults might be very different from the academic milieu.

“We hope that our unique approaches lend more breadth to the session,” said Dr. Slawski. “We want to make sure we have a good representation of SHM’s constituency, and that we present high-impact studies.”

To hit the mark of articles that are relevant for all, Dr. Cooper said she wants to make sure to focus on the practicalities of hospital-based practice – possible topics include prediction scores, hepatic encephalopathy, and the management of sepsis.

Neither Dr. Slawski nor Dr. Cooper reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Update in Hospital Medicine

Tuesday, 1:40-2:40 p.m.

Palms Ballroom

Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, and Cynthia Cooper, MD, hadn’t met in person until early 2018. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t spent a lot of time together.

Once a month, the two hospitalists checked in with one another through wide-ranging phone calls. Together, they have combed the medical literature and conferred over the past year, making long lists of candidate studies for the “Top 20” journal articles of the year for practicing hospitalists.

The two physicians will comoderate Tuesday’s “Update in Hospital Medicine” session, where they will summarize research findings of these “Top 20” articles. Their hope is to present research that each attendee can bring home to improve patient outcomes on a daily basis, while making for a smoother and more efficient practice.

Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said the presentations will not simply summarize study results but also will help attendees focus on the key findings – the clinical pearls – that represent real opportunities to update practice.

Since hospital medicine crosses so many disciplines, each physician said, in separate interviews, that doing justice to the literature has been time consuming and intellectually challenging – but worthwhile.

Dr. Cooper, a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that, although she and Dr. Slawski practice in geographically diverse areas, their practice settings – academic medical centers – have many similarities. She said that, as she reviewed the medical literature over the past year, she gave considerable thought to the particular challenges and demands of hospitalists who practice in community hospitals and rural settings, where the level of support and access to subspecialty consults might be very different from the academic milieu.

“We hope that our unique approaches lend more breadth to the session,” said Dr. Slawski. “We want to make sure we have a good representation of SHM’s constituency, and that we present high-impact studies.”

To hit the mark of articles that are relevant for all, Dr. Cooper said she wants to make sure to focus on the practicalities of hospital-based practice – possible topics include prediction scores, hepatic encephalopathy, and the management of sepsis.

Neither Dr. Slawski nor Dr. Cooper reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Update in Hospital Medicine

Tuesday, 1:40-2:40 p.m.

Palms Ballroom

New guidance for inpatient opioid prescribing

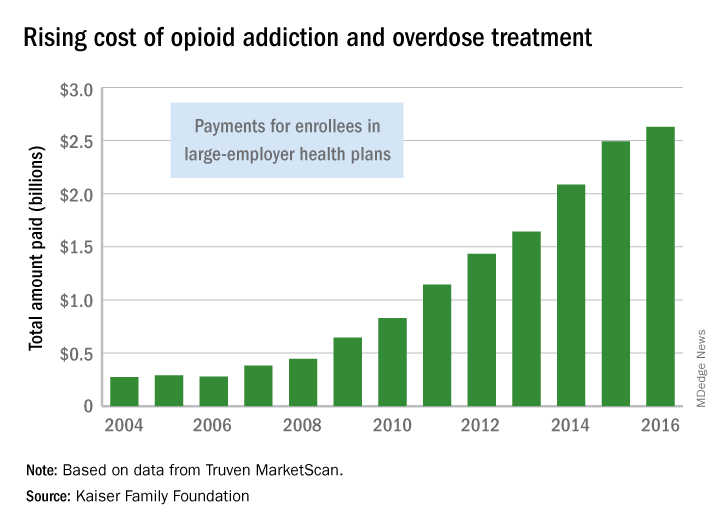

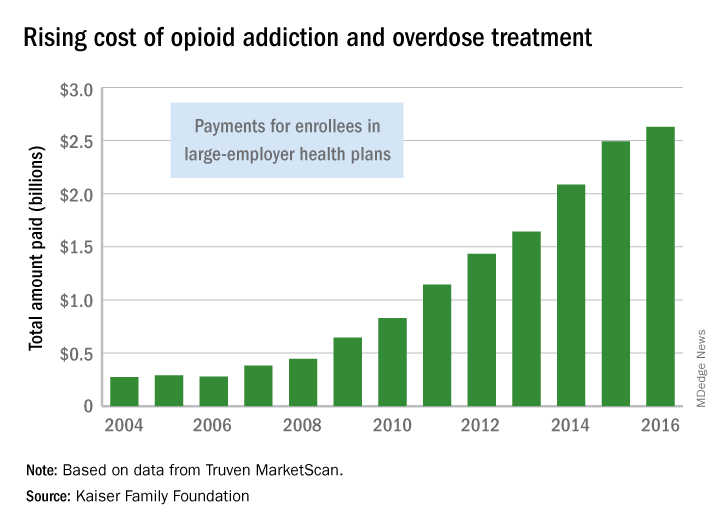

ORLANDO – A new guidance statement for opioid prescribing for hospitalized adults who have acute noncancer pain has been issued by the Society for Hospital Medicine.

The statement comes after an exhaustive systematic review that found just four existing guidelines met inclusion criteria, though none focused specifically on acute pain in hospitalized adults.

Among the key issues taken from the existing guidelines and addressed in the new SHM guidance statement are deciding when opioids – or a nonopioid alternative – should be used, as well as selection of appropriate dose, route, and duration of administration. The guidance statement advises that clinicians prescribe the lowest effective opioid dose for the shortest duration possible.

Best practices for screening and monitoring before and during opioid initiation is another major focus, as is minimizing opioid-related adverse events, both by careful patient selection and by judicious prescribing.

Finally, the statement acknowledges that, when a discharge medication list includes an opioid prescription, there is potential risk for misuse or diversion. Accordingly, the recommendation is to limit the duration of outpatient prescribing to 7 days of medication, with consideration of a 3-5 day prescription.

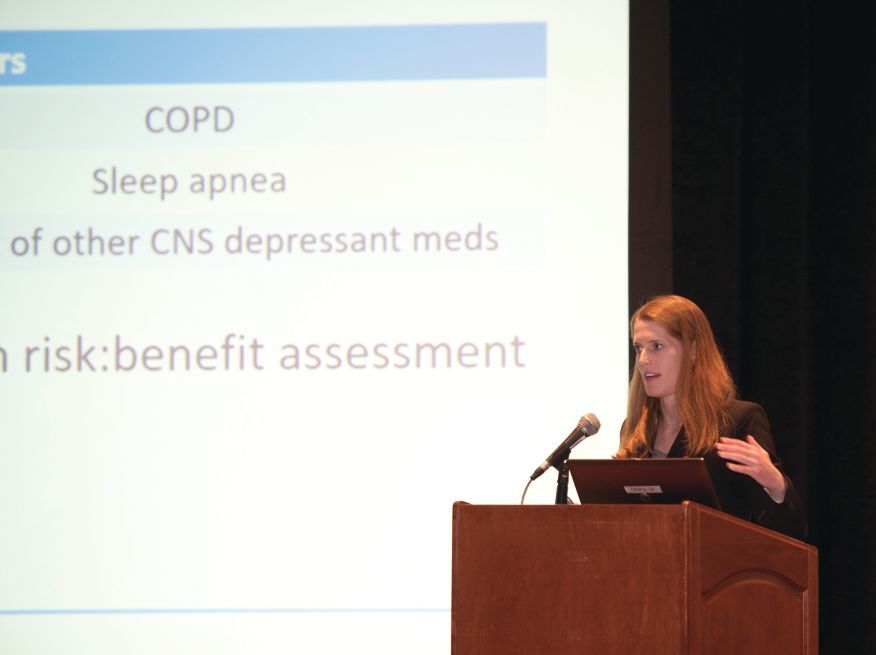

An interactive session at the 2018 SHM annual meeting presenting the guidance statement focused less on marching through the guidance’s 16 specific statements, and more on teasing out the why, when, how – and how long – of inpatient opioid prescribing.

The well-attended session, led by two of the guideline authors, Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, and Teryl K. Nuckols, MD, FHM, began with Dr. Herzig, director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, making a compelling case for why guidance is needed for inpatient opioid prescribing for acute pain.

“Few would disagree that, at the end of the day, we are the final common pathway” for hospitalized patients who receive opioids, said Dr. Herzig. And there’s ample evidence that troublesome opioid prescribing is widespread, she said, adding that associated problems aren’t limited to such inpatient adverse events as falls, respiratory arrest, and acute kidney injury; plenty of opioid-exposed patients who leave the hospital continue to use opioids in problematic ways after discharge.

Of patients who were opioid naive and filled outpatient opioid prescriptions on discharge, “Almost half of patients were still using opioids 90 days later,” Dr. Herzig said. “Hospitals contribute to opioid initiation in millions of patients each year, so our prescribing patterns in the hospital do matter.”

“We tend to prescribe high doses,” said Dr. Herzig – an average of a 68-mg oral morphine equivalent (OME) dose on days that opioids were received, according to a 2014 study she coauthored. Overall, Dr. Herzig and her colleagues found that about 40% of patients who received opioids had a daily dose of at least 50 mg OME, and about a quarter received a daily dose at or exceeding 100 mg OME (Herzig et al. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9[2]:73-81).

Further, she said, “We tend to prescribe a bit haphazardly.” The same study found wide variation in regional inpatient opioid-prescribing practices, with inpatients in the U.S. Midwest, South, and West seeing adjusted relative rates of exposure to opioids of 1.26, 1.33, and 1.37, compared with the Northeast, she said.

Among the more concerning findings, she said, was that “hospitals that prescribe opioids more frequently appear to do so less safely.” In hospitals that fell into the top quartile for inpatient opioid exposure, the overall rate of opioid-related adverse events was 0.39%, compared with 0.21% for hospitals in the bottom quartile of opioid prescribing, for an overall adjusted relative risk of 1.23 in opioid-exposed patients in the hospitals with the highest prescribing, said Dr. Herzig.

Dr. Nuckols, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, engaged attendees to identify challenges in acute pain management among hospitalized adults.

The audience was quick and prolific with answers, which included varying physician standards for opioid prescribing; patient expectations for pain management – and sometimes denial that opioid use has become a disorder; varying expectations for pain management among care team members who may be reluctant to let go of pain as “the fifth vital sign;” difficulty accessing and being reimbursed for nonpharmacologic strategies; and, acknowledged by all, patient satisfaction scores.

To this last point, Dr. Nuckols said that there have been “a few recent changes for the better.” The Joint Commission is revising its standards to move away from pain as a vital sign, toward a focused assessment of pain that considers how patients are responding to pain, as well as functional status. However, she said, “There aren’t any validated measures yet for how we’re going to do this.”

Similar shifts are underway with pain-related HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) questions, which have undergone a “big pullback” from an emphasis on complete control of pain, and now put more focus on whether caregivers asked about pain and talked with inpatients about ways to treat pain, said Dr. Nuckols.

Speaking to the process of developing the guidance statement, Dr. Nuckols said that “I think it’s important to note that the empirical literature about managing pain for inpatients … is almost nonexistent.” Of the four criteria that met inclusion criteria – “and we were tough raters when it comes to the guidelines” – most were based on expert consensus, she said, and most had primarily an outpatient focus.

Themes that emerged from the review process included consideration of a nonopioid strategy before initiating an opioid. These might include pharmacologic interventions such as acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory for nociceptive pain, pregabalin, gabapentin, or other medication to manage neuropathic pain, or nonpharmacologic interventions such as heat, ice, or distraction. All of these should also be considered as adjuncts to minimize opioid dosing as well, said Dr. Nuckols, citing well-documented synergy with multiple modalities of pain treatment.

Careful patient selection is also key, said Dr. Nuckols. She noted that she asks herself, “How likely is this patient to get into trouble?” with inpatient opioid administration. A concept that goes hand-in-hand, she said, is choosing the appropriate dose and route.

Dr. Herzig picked up this theme, noting that route of administration matters. A speedy route, such as intravenous administration, has been shown to reinforce the potentially addictive effect of opioids. There are times when IV is the route to use, such as when the patient can’t take medication by mouth or when immediate pain control truly is needed. However, oral medication is just as effective, albeit slightly slower acting, she said.

Conversion from IV to oral opioids is a potential time for trouble, said Dr. Herzig. “Always use an opioid conversion chart,” she said. Cross-tolerance can be incomplete between opioids, so safe practice is to begin with about 50% of the OME dose with the new medication and titrate up. And don’t use a long-acting opioid for acute pain, she said, noting that not only will there be a long half-life and washout period if the dose is too high, but patient risk for later opioid use disorder is also upped with this strategy. “You can always add more, but it’s hard to take away,” said Dr. Herzig.

On discharge, consider whether an opioid should be prescribed at all, said Dr. Herzig. The guidance statement advises generally prescribing less than a 7-day supply, with the rationale that, if posthospitalization acute pain is severe enough to require an opioid at that point, the patient should have outpatient follow-up.

This approach doesn’t undertreat outpatient pain, said Dr. Herzig, pointing to studies that show that, at discharge, “the majority of opioids that patients are getting, they are not taking – which tells us that by definition we are overprescribing.”

The authors of the guidance statement wanted to address two important topics that were not sufficiently evidence backed, Dr. Herzig said. They had hoped to give clear guidance about best practices for communication and follow-up with outpatient providers after hospital discharge. Though they didn’t find clear guidance in this area, “We do believe that outpatient providers need to be kept in the loop.”

A second area, currently a hot button topic both in the medical community and in the lay press, is whether a naloxone prescription should accompany an opioid prescription at discharge. “There just aren’t studies for this,” said Dr. Herzig.

The full text of the guidance statement may be found here: https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/161927/hospital-medicine/improving-safety-opioid-use-acute-noncancer-pain.

ORLANDO – A new guidance statement for opioid prescribing for hospitalized adults who have acute noncancer pain has been issued by the Society for Hospital Medicine.

The statement comes after an exhaustive systematic review that found just four existing guidelines met inclusion criteria, though none focused specifically on acute pain in hospitalized adults.

Among the key issues taken from the existing guidelines and addressed in the new SHM guidance statement are deciding when opioids – or a nonopioid alternative – should be used, as well as selection of appropriate dose, route, and duration of administration. The guidance statement advises that clinicians prescribe the lowest effective opioid dose for the shortest duration possible.

Best practices for screening and monitoring before and during opioid initiation is another major focus, as is minimizing opioid-related adverse events, both by careful patient selection and by judicious prescribing.

Finally, the statement acknowledges that, when a discharge medication list includes an opioid prescription, there is potential risk for misuse or diversion. Accordingly, the recommendation is to limit the duration of outpatient prescribing to 7 days of medication, with consideration of a 3-5 day prescription.

An interactive session at the 2018 SHM annual meeting presenting the guidance statement focused less on marching through the guidance’s 16 specific statements, and more on teasing out the why, when, how – and how long – of inpatient opioid prescribing.

The well-attended session, led by two of the guideline authors, Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, and Teryl K. Nuckols, MD, FHM, began with Dr. Herzig, director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, making a compelling case for why guidance is needed for inpatient opioid prescribing for acute pain.

“Few would disagree that, at the end of the day, we are the final common pathway” for hospitalized patients who receive opioids, said Dr. Herzig. And there’s ample evidence that troublesome opioid prescribing is widespread, she said, adding that associated problems aren’t limited to such inpatient adverse events as falls, respiratory arrest, and acute kidney injury; plenty of opioid-exposed patients who leave the hospital continue to use opioids in problematic ways after discharge.

Of patients who were opioid naive and filled outpatient opioid prescriptions on discharge, “Almost half of patients were still using opioids 90 days later,” Dr. Herzig said. “Hospitals contribute to opioid initiation in millions of patients each year, so our prescribing patterns in the hospital do matter.”

“We tend to prescribe high doses,” said Dr. Herzig – an average of a 68-mg oral morphine equivalent (OME) dose on days that opioids were received, according to a 2014 study she coauthored. Overall, Dr. Herzig and her colleagues found that about 40% of patients who received opioids had a daily dose of at least 50 mg OME, and about a quarter received a daily dose at or exceeding 100 mg OME (Herzig et al. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9[2]:73-81).

Further, she said, “We tend to prescribe a bit haphazardly.” The same study found wide variation in regional inpatient opioid-prescribing practices, with inpatients in the U.S. Midwest, South, and West seeing adjusted relative rates of exposure to opioids of 1.26, 1.33, and 1.37, compared with the Northeast, she said.

Among the more concerning findings, she said, was that “hospitals that prescribe opioids more frequently appear to do so less safely.” In hospitals that fell into the top quartile for inpatient opioid exposure, the overall rate of opioid-related adverse events was 0.39%, compared with 0.21% for hospitals in the bottom quartile of opioid prescribing, for an overall adjusted relative risk of 1.23 in opioid-exposed patients in the hospitals with the highest prescribing, said Dr. Herzig.

Dr. Nuckols, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, engaged attendees to identify challenges in acute pain management among hospitalized adults.

The audience was quick and prolific with answers, which included varying physician standards for opioid prescribing; patient expectations for pain management – and sometimes denial that opioid use has become a disorder; varying expectations for pain management among care team members who may be reluctant to let go of pain as “the fifth vital sign;” difficulty accessing and being reimbursed for nonpharmacologic strategies; and, acknowledged by all, patient satisfaction scores.

To this last point, Dr. Nuckols said that there have been “a few recent changes for the better.” The Joint Commission is revising its standards to move away from pain as a vital sign, toward a focused assessment of pain that considers how patients are responding to pain, as well as functional status. However, she said, “There aren’t any validated measures yet for how we’re going to do this.”

Similar shifts are underway with pain-related HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) questions, which have undergone a “big pullback” from an emphasis on complete control of pain, and now put more focus on whether caregivers asked about pain and talked with inpatients about ways to treat pain, said Dr. Nuckols.

Speaking to the process of developing the guidance statement, Dr. Nuckols said that “I think it’s important to note that the empirical literature about managing pain for inpatients … is almost nonexistent.” Of the four criteria that met inclusion criteria – “and we were tough raters when it comes to the guidelines” – most were based on expert consensus, she said, and most had primarily an outpatient focus.

Themes that emerged from the review process included consideration of a nonopioid strategy before initiating an opioid. These might include pharmacologic interventions such as acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory for nociceptive pain, pregabalin, gabapentin, or other medication to manage neuropathic pain, or nonpharmacologic interventions such as heat, ice, or distraction. All of these should also be considered as adjuncts to minimize opioid dosing as well, said Dr. Nuckols, citing well-documented synergy with multiple modalities of pain treatment.

Careful patient selection is also key, said Dr. Nuckols. She noted that she asks herself, “How likely is this patient to get into trouble?” with inpatient opioid administration. A concept that goes hand-in-hand, she said, is choosing the appropriate dose and route.

Dr. Herzig picked up this theme, noting that route of administration matters. A speedy route, such as intravenous administration, has been shown to reinforce the potentially addictive effect of opioids. There are times when IV is the route to use, such as when the patient can’t take medication by mouth or when immediate pain control truly is needed. However, oral medication is just as effective, albeit slightly slower acting, she said.

Conversion from IV to oral opioids is a potential time for trouble, said Dr. Herzig. “Always use an opioid conversion chart,” she said. Cross-tolerance can be incomplete between opioids, so safe practice is to begin with about 50% of the OME dose with the new medication and titrate up. And don’t use a long-acting opioid for acute pain, she said, noting that not only will there be a long half-life and washout period if the dose is too high, but patient risk for later opioid use disorder is also upped with this strategy. “You can always add more, but it’s hard to take away,” said Dr. Herzig.

On discharge, consider whether an opioid should be prescribed at all, said Dr. Herzig. The guidance statement advises generally prescribing less than a 7-day supply, with the rationale that, if posthospitalization acute pain is severe enough to require an opioid at that point, the patient should have outpatient follow-up.

This approach doesn’t undertreat outpatient pain, said Dr. Herzig, pointing to studies that show that, at discharge, “the majority of opioids that patients are getting, they are not taking – which tells us that by definition we are overprescribing.”

The authors of the guidance statement wanted to address two important topics that were not sufficiently evidence backed, Dr. Herzig said. They had hoped to give clear guidance about best practices for communication and follow-up with outpatient providers after hospital discharge. Though they didn’t find clear guidance in this area, “We do believe that outpatient providers need to be kept in the loop.”

A second area, currently a hot button topic both in the medical community and in the lay press, is whether a naloxone prescription should accompany an opioid prescription at discharge. “There just aren’t studies for this,” said Dr. Herzig.

The full text of the guidance statement may be found here: https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/161927/hospital-medicine/improving-safety-opioid-use-acute-noncancer-pain.

ORLANDO – A new guidance statement for opioid prescribing for hospitalized adults who have acute noncancer pain has been issued by the Society for Hospital Medicine.

The statement comes after an exhaustive systematic review that found just four existing guidelines met inclusion criteria, though none focused specifically on acute pain in hospitalized adults.

Among the key issues taken from the existing guidelines and addressed in the new SHM guidance statement are deciding when opioids – or a nonopioid alternative – should be used, as well as selection of appropriate dose, route, and duration of administration. The guidance statement advises that clinicians prescribe the lowest effective opioid dose for the shortest duration possible.

Best practices for screening and monitoring before and during opioid initiation is another major focus, as is minimizing opioid-related adverse events, both by careful patient selection and by judicious prescribing.

Finally, the statement acknowledges that, when a discharge medication list includes an opioid prescription, there is potential risk for misuse or diversion. Accordingly, the recommendation is to limit the duration of outpatient prescribing to 7 days of medication, with consideration of a 3-5 day prescription.

An interactive session at the 2018 SHM annual meeting presenting the guidance statement focused less on marching through the guidance’s 16 specific statements, and more on teasing out the why, when, how – and how long – of inpatient opioid prescribing.

The well-attended session, led by two of the guideline authors, Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, and Teryl K. Nuckols, MD, FHM, began with Dr. Herzig, director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, making a compelling case for why guidance is needed for inpatient opioid prescribing for acute pain.

“Few would disagree that, at the end of the day, we are the final common pathway” for hospitalized patients who receive opioids, said Dr. Herzig. And there’s ample evidence that troublesome opioid prescribing is widespread, she said, adding that associated problems aren’t limited to such inpatient adverse events as falls, respiratory arrest, and acute kidney injury; plenty of opioid-exposed patients who leave the hospital continue to use opioids in problematic ways after discharge.

Of patients who were opioid naive and filled outpatient opioid prescriptions on discharge, “Almost half of patients were still using opioids 90 days later,” Dr. Herzig said. “Hospitals contribute to opioid initiation in millions of patients each year, so our prescribing patterns in the hospital do matter.”

“We tend to prescribe high doses,” said Dr. Herzig – an average of a 68-mg oral morphine equivalent (OME) dose on days that opioids were received, according to a 2014 study she coauthored. Overall, Dr. Herzig and her colleagues found that about 40% of patients who received opioids had a daily dose of at least 50 mg OME, and about a quarter received a daily dose at or exceeding 100 mg OME (Herzig et al. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9[2]:73-81).

Further, she said, “We tend to prescribe a bit haphazardly.” The same study found wide variation in regional inpatient opioid-prescribing practices, with inpatients in the U.S. Midwest, South, and West seeing adjusted relative rates of exposure to opioids of 1.26, 1.33, and 1.37, compared with the Northeast, she said.

Among the more concerning findings, she said, was that “hospitals that prescribe opioids more frequently appear to do so less safely.” In hospitals that fell into the top quartile for inpatient opioid exposure, the overall rate of opioid-related adverse events was 0.39%, compared with 0.21% for hospitals in the bottom quartile of opioid prescribing, for an overall adjusted relative risk of 1.23 in opioid-exposed patients in the hospitals with the highest prescribing, said Dr. Herzig.

Dr. Nuckols, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, engaged attendees to identify challenges in acute pain management among hospitalized adults.

The audience was quick and prolific with answers, which included varying physician standards for opioid prescribing; patient expectations for pain management – and sometimes denial that opioid use has become a disorder; varying expectations for pain management among care team members who may be reluctant to let go of pain as “the fifth vital sign;” difficulty accessing and being reimbursed for nonpharmacologic strategies; and, acknowledged by all, patient satisfaction scores.

To this last point, Dr. Nuckols said that there have been “a few recent changes for the better.” The Joint Commission is revising its standards to move away from pain as a vital sign, toward a focused assessment of pain that considers how patients are responding to pain, as well as functional status. However, she said, “There aren’t any validated measures yet for how we’re going to do this.”

Similar shifts are underway with pain-related HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) questions, which have undergone a “big pullback” from an emphasis on complete control of pain, and now put more focus on whether caregivers asked about pain and talked with inpatients about ways to treat pain, said Dr. Nuckols.

Speaking to the process of developing the guidance statement, Dr. Nuckols said that “I think it’s important to note that the empirical literature about managing pain for inpatients … is almost nonexistent.” Of the four criteria that met inclusion criteria – “and we were tough raters when it comes to the guidelines” – most were based on expert consensus, she said, and most had primarily an outpatient focus.

Themes that emerged from the review process included consideration of a nonopioid strategy before initiating an opioid. These might include pharmacologic interventions such as acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory for nociceptive pain, pregabalin, gabapentin, or other medication to manage neuropathic pain, or nonpharmacologic interventions such as heat, ice, or distraction. All of these should also be considered as adjuncts to minimize opioid dosing as well, said Dr. Nuckols, citing well-documented synergy with multiple modalities of pain treatment.

Careful patient selection is also key, said Dr. Nuckols. She noted that she asks herself, “How likely is this patient to get into trouble?” with inpatient opioid administration. A concept that goes hand-in-hand, she said, is choosing the appropriate dose and route.

Dr. Herzig picked up this theme, noting that route of administration matters. A speedy route, such as intravenous administration, has been shown to reinforce the potentially addictive effect of opioids. There are times when IV is the route to use, such as when the patient can’t take medication by mouth or when immediate pain control truly is needed. However, oral medication is just as effective, albeit slightly slower acting, she said.

Conversion from IV to oral opioids is a potential time for trouble, said Dr. Herzig. “Always use an opioid conversion chart,” she said. Cross-tolerance can be incomplete between opioids, so safe practice is to begin with about 50% of the OME dose with the new medication and titrate up. And don’t use a long-acting opioid for acute pain, she said, noting that not only will there be a long half-life and washout period if the dose is too high, but patient risk for later opioid use disorder is also upped with this strategy. “You can always add more, but it’s hard to take away,” said Dr. Herzig.

On discharge, consider whether an opioid should be prescribed at all, said Dr. Herzig. The guidance statement advises generally prescribing less than a 7-day supply, with the rationale that, if posthospitalization acute pain is severe enough to require an opioid at that point, the patient should have outpatient follow-up.

This approach doesn’t undertreat outpatient pain, said Dr. Herzig, pointing to studies that show that, at discharge, “the majority of opioids that patients are getting, they are not taking – which tells us that by definition we are overprescribing.”

The authors of the guidance statement wanted to address two important topics that were not sufficiently evidence backed, Dr. Herzig said. They had hoped to give clear guidance about best practices for communication and follow-up with outpatient providers after hospital discharge. Though they didn’t find clear guidance in this area, “We do believe that outpatient providers need to be kept in the loop.”

A second area, currently a hot button topic both in the medical community and in the lay press, is whether a naloxone prescription should accompany an opioid prescription at discharge. “There just aren’t studies for this,” said Dr. Herzig.

The full text of the guidance statement may be found here: https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/161927/hospital-medicine/improving-safety-opioid-use-acute-noncancer-pain.

REPORTING FROM HM18

Simvastatin, atorvastatin cut mortality risk for sepsis patients

a large health care database review has determined.

Among almost 53,000 sepsis patients, those who had been taking simvastatin were 28% less likely to die within 30 days of a sepsis admission than were patients not taking a statin. Atorvastatin conferred a similar significant survival benefit, reducing the risk of death by 22%, Chien-Chang Lee, MD and his colleagues wrote in the April issue of the journal CHEST®.

The drugs also exert a direct antimicrobial effect, he asserted.

“Of note, simvastatin was shown by several reports to have the most potent antibacterial activity,” targeting both methicillin-resistant and -sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, as well as gram negative and positive bacteria.

Dr. Lee and his colleagues extracted mortality and statin prescription data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database from 2000-2011. They looked at 30- and 90-day mortality in 52,737 patients who developed sepsis; the statins of interest were atorvastatin, simvastatin, and rosuvastatin. Patients had to have been taking the medication for at least 30 days before sepsis onset to be included, and patients taking more than one statin were excluded from the analysis.

Patients were a mean of 69 years old. About half had a lower respiratory infection. The remainder had infections within the abdomen, the biliary or urinary tract, skin, or orthopedic infections. There were no significant differences in comorbidities or in other medications taken among the three statin groups or the nonusers.

Of the entire cohort, 17% died by 30 days and nearly 23% by 90 days. Compared with those who had never received a statin, the statin users were 12% less likely to die by 30 days (hazard ratio, 0.88). Mortality at 90 days was also decreased, when compared with nonusers (HR, 0.93).

Simvastatin demonstrated the greatest benefit, with a 28% decreased risk of 30-day mortality (HR, 0.72). Atorvastatin followed, with a 22% risk reduction (HR, 0.78). Rosuvastatin exerted a nonsignificant 13% benefit.

The authors then examined 90-day mortality risks for the patients with a propensity matching score using a subgroup comprising 536 simvastatin users, 536 atorvastatin users, and 536 rosuvastatin users. Simvastatin was associated with a 23% reduction in 30-day mortality risk (HR, 0.77) and atorvastatin with a 21% reduction (HR, 0.79), when compared with rosuvastatin.

Statins’ antimicrobial properties are probably partially caused by their inactivation of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase pathway, Dr. Lee and his colleagues noted. In addition to being vital for cholesterol synthesis, this pathway “also contributes to the production of isoprenoids and lipid compounds that are essential for cell signaling and structure in the pathogen. Secondly, the chemical property of different types of statins may affect their targeting to bacteria. The lipophilic properties of simvastatin or atorvastatin may allow better binding to bacteria cell walls than the hydrophilic properties of rosuvastatin.”

The study was funded by the Taiwan National Science Foundation and Taiwan National Ministry of Science and Technology. Dr. Lee had no financial conflicts.

The statin-sepsis mortality link will probably never be definitively proven, but the study by Lee and colleagues gives us the best data so far on this intriguing connection, Steven Q. Simpson, MD and Joel D. Mermis, MD wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“It is unlikely that prospective randomized trials of statins for prevention of sepsis mortality will ever be undertaken, owing to the sheer number of patients that would require randomization in order to have adequate numbers who actually develop sepsis,” the colleagues wrote. “We believe that the next best thing to randomization and a prospective trial is exactly what the authors have done – identify a cohort, track them through time, even if nonconcurrently, and match cases to controls by propensity matching on important clinical characteristics.”

Nevertheless, the two said, “This brings us to one aspect of the study that leaves open a window for some doubt.”

Lee et al. extracted their data from a large national insurance claims database. These systems “are commonly believed to overestimate sepsis incidence,” Dr. Simpson and Dr. Mermis wrote. A 2009 U.S. study bore this out, they said. “That study showed that in the U.S in 2014, there were approximately 1.7 million cases of sepsis in a population of 330 million, for an annual incidence rate of five sepsis cases per 1,000 patient-years.”

However, a “quick calculation” of the Taiwan data suggests that the annual sepsis caseload is about 5,200 per year in a population of 23 million at risk – an annual incidence of only 0.2 cases per 1,000 patient-years.

“This represents an order of magnitude difference in sepsis incidence between the U.S. and Taiwan, providing some issues to ponder. Does Taiwan indeed have a lower incidence of sepsis by that much? If so, is the lower incidence related to genetics, environment, health care access, or other factors?

“Although Lee et al. have provided us with data of the highest quality that we can likely hope for, the book may not be quite closed, yet.”

Dr. Mermis and Dr. Simpson are pulmonologists at the University of Kansas, Kansas City. They made their comments in an editorial published in the April issue of CHEST® (Mermis JD and Simpson SQ. CHEST. 2018 April. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.004.)

The statin-sepsis mortality link will probably never be definitively proven, but the study by Lee and colleagues gives us the best data so far on this intriguing connection, Steven Q. Simpson, MD and Joel D. Mermis, MD wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“It is unlikely that prospective randomized trials of statins for prevention of sepsis mortality will ever be undertaken, owing to the sheer number of patients that would require randomization in order to have adequate numbers who actually develop sepsis,” the colleagues wrote. “We believe that the next best thing to randomization and a prospective trial is exactly what the authors have done – identify a cohort, track them through time, even if nonconcurrently, and match cases to controls by propensity matching on important clinical characteristics.”

Nevertheless, the two said, “This brings us to one aspect of the study that leaves open a window for some doubt.”

Lee et al. extracted their data from a large national insurance claims database. These systems “are commonly believed to overestimate sepsis incidence,” Dr. Simpson and Dr. Mermis wrote. A 2009 U.S. study bore this out, they said. “That study showed that in the U.S in 2014, there were approximately 1.7 million cases of sepsis in a population of 330 million, for an annual incidence rate of five sepsis cases per 1,000 patient-years.”

However, a “quick calculation” of the Taiwan data suggests that the annual sepsis caseload is about 5,200 per year in a population of 23 million at risk – an annual incidence of only 0.2 cases per 1,000 patient-years.

“This represents an order of magnitude difference in sepsis incidence between the U.S. and Taiwan, providing some issues to ponder. Does Taiwan indeed have a lower incidence of sepsis by that much? If so, is the lower incidence related to genetics, environment, health care access, or other factors?

“Although Lee et al. have provided us with data of the highest quality that we can likely hope for, the book may not be quite closed, yet.”

Dr. Mermis and Dr. Simpson are pulmonologists at the University of Kansas, Kansas City. They made their comments in an editorial published in the April issue of CHEST® (Mermis JD and Simpson SQ. CHEST. 2018 April. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.004.)

The statin-sepsis mortality link will probably never be definitively proven, but the study by Lee and colleagues gives us the best data so far on this intriguing connection, Steven Q. Simpson, MD and Joel D. Mermis, MD wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“It is unlikely that prospective randomized trials of statins for prevention of sepsis mortality will ever be undertaken, owing to the sheer number of patients that would require randomization in order to have adequate numbers who actually develop sepsis,” the colleagues wrote. “We believe that the next best thing to randomization and a prospective trial is exactly what the authors have done – identify a cohort, track them through time, even if nonconcurrently, and match cases to controls by propensity matching on important clinical characteristics.”

Nevertheless, the two said, “This brings us to one aspect of the study that leaves open a window for some doubt.”

Lee et al. extracted their data from a large national insurance claims database. These systems “are commonly believed to overestimate sepsis incidence,” Dr. Simpson and Dr. Mermis wrote. A 2009 U.S. study bore this out, they said. “That study showed that in the U.S in 2014, there were approximately 1.7 million cases of sepsis in a population of 330 million, for an annual incidence rate of five sepsis cases per 1,000 patient-years.”

However, a “quick calculation” of the Taiwan data suggests that the annual sepsis caseload is about 5,200 per year in a population of 23 million at risk – an annual incidence of only 0.2 cases per 1,000 patient-years.

“This represents an order of magnitude difference in sepsis incidence between the U.S. and Taiwan, providing some issues to ponder. Does Taiwan indeed have a lower incidence of sepsis by that much? If so, is the lower incidence related to genetics, environment, health care access, or other factors?

“Although Lee et al. have provided us with data of the highest quality that we can likely hope for, the book may not be quite closed, yet.”

Dr. Mermis and Dr. Simpson are pulmonologists at the University of Kansas, Kansas City. They made their comments in an editorial published in the April issue of CHEST® (Mermis JD and Simpson SQ. CHEST. 2018 April. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.004.)

a large health care database review has determined.

Among almost 53,000 sepsis patients, those who had been taking simvastatin were 28% less likely to die within 30 days of a sepsis admission than were patients not taking a statin. Atorvastatin conferred a similar significant survival benefit, reducing the risk of death by 22%, Chien-Chang Lee, MD and his colleagues wrote in the April issue of the journal CHEST®.

The drugs also exert a direct antimicrobial effect, he asserted.

“Of note, simvastatin was shown by several reports to have the most potent antibacterial activity,” targeting both methicillin-resistant and -sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, as well as gram negative and positive bacteria.

Dr. Lee and his colleagues extracted mortality and statin prescription data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database from 2000-2011. They looked at 30- and 90-day mortality in 52,737 patients who developed sepsis; the statins of interest were atorvastatin, simvastatin, and rosuvastatin. Patients had to have been taking the medication for at least 30 days before sepsis onset to be included, and patients taking more than one statin were excluded from the analysis.

Patients were a mean of 69 years old. About half had a lower respiratory infection. The remainder had infections within the abdomen, the biliary or urinary tract, skin, or orthopedic infections. There were no significant differences in comorbidities or in other medications taken among the three statin groups or the nonusers.

Of the entire cohort, 17% died by 30 days and nearly 23% by 90 days. Compared with those who had never received a statin, the statin users were 12% less likely to die by 30 days (hazard ratio, 0.88). Mortality at 90 days was also decreased, when compared with nonusers (HR, 0.93).

Simvastatin demonstrated the greatest benefit, with a 28% decreased risk of 30-day mortality (HR, 0.72). Atorvastatin followed, with a 22% risk reduction (HR, 0.78). Rosuvastatin exerted a nonsignificant 13% benefit.

The authors then examined 90-day mortality risks for the patients with a propensity matching score using a subgroup comprising 536 simvastatin users, 536 atorvastatin users, and 536 rosuvastatin users. Simvastatin was associated with a 23% reduction in 30-day mortality risk (HR, 0.77) and atorvastatin with a 21% reduction (HR, 0.79), when compared with rosuvastatin.

Statins’ antimicrobial properties are probably partially caused by their inactivation of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase pathway, Dr. Lee and his colleagues noted. In addition to being vital for cholesterol synthesis, this pathway “also contributes to the production of isoprenoids and lipid compounds that are essential for cell signaling and structure in the pathogen. Secondly, the chemical property of different types of statins may affect their targeting to bacteria. The lipophilic properties of simvastatin or atorvastatin may allow better binding to bacteria cell walls than the hydrophilic properties of rosuvastatin.”

The study was funded by the Taiwan National Science Foundation and Taiwan National Ministry of Science and Technology. Dr. Lee had no financial conflicts.

a large health care database review has determined.

Among almost 53,000 sepsis patients, those who had been taking simvastatin were 28% less likely to die within 30 days of a sepsis admission than were patients not taking a statin. Atorvastatin conferred a similar significant survival benefit, reducing the risk of death by 22%, Chien-Chang Lee, MD and his colleagues wrote in the April issue of the journal CHEST®.

The drugs also exert a direct antimicrobial effect, he asserted.

“Of note, simvastatin was shown by several reports to have the most potent antibacterial activity,” targeting both methicillin-resistant and -sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, as well as gram negative and positive bacteria.

Dr. Lee and his colleagues extracted mortality and statin prescription data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database from 2000-2011. They looked at 30- and 90-day mortality in 52,737 patients who developed sepsis; the statins of interest were atorvastatin, simvastatin, and rosuvastatin. Patients had to have been taking the medication for at least 30 days before sepsis onset to be included, and patients taking more than one statin were excluded from the analysis.

Patients were a mean of 69 years old. About half had a lower respiratory infection. The remainder had infections within the abdomen, the biliary or urinary tract, skin, or orthopedic infections. There were no significant differences in comorbidities or in other medications taken among the three statin groups or the nonusers.

Of the entire cohort, 17% died by 30 days and nearly 23% by 90 days. Compared with those who had never received a statin, the statin users were 12% less likely to die by 30 days (hazard ratio, 0.88). Mortality at 90 days was also decreased, when compared with nonusers (HR, 0.93).

Simvastatin demonstrated the greatest benefit, with a 28% decreased risk of 30-day mortality (HR, 0.72). Atorvastatin followed, with a 22% risk reduction (HR, 0.78). Rosuvastatin exerted a nonsignificant 13% benefit.

The authors then examined 90-day mortality risks for the patients with a propensity matching score using a subgroup comprising 536 simvastatin users, 536 atorvastatin users, and 536 rosuvastatin users. Simvastatin was associated with a 23% reduction in 30-day mortality risk (HR, 0.77) and atorvastatin with a 21% reduction (HR, 0.79), when compared with rosuvastatin.

Statins’ antimicrobial properties are probably partially caused by their inactivation of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase pathway, Dr. Lee and his colleagues noted. In addition to being vital for cholesterol synthesis, this pathway “also contributes to the production of isoprenoids and lipid compounds that are essential for cell signaling and structure in the pathogen. Secondly, the chemical property of different types of statins may affect their targeting to bacteria. The lipophilic properties of simvastatin or atorvastatin may allow better binding to bacteria cell walls than the hydrophilic properties of rosuvastatin.”

The study was funded by the Taiwan National Science Foundation and Taiwan National Ministry of Science and Technology. Dr. Lee had no financial conflicts.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Simvastatin and atorvastatin were associated with decreased mortality risk among sepsis patients.

Major finding: Compared with those not taking the drugs, those taking simvastatin were 28% less likely to die by 30 days, and those taking atorvastatin were 22% less likely.

Study details: The database study comprised almost 54,000 sepsis cases over 11 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Taiwan National Science Foundation and Taiwan National Ministry of Science and Technology. Dr. Lee had no financial conflicts.

Source: Lee C-C et al. CHEST. 2018 April;153(4):769-70.

Use of a risk score may be able to identify high-risk patients presenting with acute heart failure

Clinical question: Can we use readily available data to risk stratify patients who present to the emergency department in acute heart failure (AHF)?

Background: Although cardiac biomarkers such as troponin and B-natriuretic peptide have general prognostic value in patients with AHF presenting to the emergency department, these values do not reliably aid in determining patients’ risk for unfavorable outcomes at the time of clinical decision making. Currently available published scores for risk-stratifying patients with AHF in the ED have limited applicability.

Setting: The registry included patients from 34 different hospitals in Spain.

Synopsis: This study analyzed clinical variables from a cohort of 4,897 AHF patients to determine predictors of patient outcomes. Thirteen clinical variables were identified as independent predictors of 30-day mortality and were incorporated into a risk score calculator (MEESSI-AHF). The risk score includes variables such as vital signs, age, labs values, and performance status. A second cohort of 3,229 patients were used to validate the risk score. The risk score effectively discriminates patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients. One important limitation is a high number of missing values in derivation cohort that required advanced statistics to overcome. The generalizability of the population studies (Spanish population) to other countries is still unclear. A risk score that can reasonably identify low-risk patients may be the most clinically useful in order to identify patients that either can be treated effectively in the emergency department and may not warrant inpatient admission.

Bottom line: The MEESSI-AHF risk score may be a helpful tool in identifying the risk of 30-day mortality in patients who present to the ED with AHF, but it is currently unclear if the score can be generalized to other populations.

Citation: Miro O et al. Predicting 30-day mortality for patients with acute heart failure in the emergency department: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 21;167(10):698-705.

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Clinical question: Can we use readily available data to risk stratify patients who present to the emergency department in acute heart failure (AHF)?

Background: Although cardiac biomarkers such as troponin and B-natriuretic peptide have general prognostic value in patients with AHF presenting to the emergency department, these values do not reliably aid in determining patients’ risk for unfavorable outcomes at the time of clinical decision making. Currently available published scores for risk-stratifying patients with AHF in the ED have limited applicability.

Setting: The registry included patients from 34 different hospitals in Spain.

Synopsis: This study analyzed clinical variables from a cohort of 4,897 AHF patients to determine predictors of patient outcomes. Thirteen clinical variables were identified as independent predictors of 30-day mortality and were incorporated into a risk score calculator (MEESSI-AHF). The risk score includes variables such as vital signs, age, labs values, and performance status. A second cohort of 3,229 patients were used to validate the risk score. The risk score effectively discriminates patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients. One important limitation is a high number of missing values in derivation cohort that required advanced statistics to overcome. The generalizability of the population studies (Spanish population) to other countries is still unclear. A risk score that can reasonably identify low-risk patients may be the most clinically useful in order to identify patients that either can be treated effectively in the emergency department and may not warrant inpatient admission.

Bottom line: The MEESSI-AHF risk score may be a helpful tool in identifying the risk of 30-day mortality in patients who present to the ED with AHF, but it is currently unclear if the score can be generalized to other populations.

Citation: Miro O et al. Predicting 30-day mortality for patients with acute heart failure in the emergency department: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 21;167(10):698-705.

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Clinical question: Can we use readily available data to risk stratify patients who present to the emergency department in acute heart failure (AHF)?

Background: Although cardiac biomarkers such as troponin and B-natriuretic peptide have general prognostic value in patients with AHF presenting to the emergency department, these values do not reliably aid in determining patients’ risk for unfavorable outcomes at the time of clinical decision making. Currently available published scores for risk-stratifying patients with AHF in the ED have limited applicability.

Setting: The registry included patients from 34 different hospitals in Spain.

Synopsis: This study analyzed clinical variables from a cohort of 4,897 AHF patients to determine predictors of patient outcomes. Thirteen clinical variables were identified as independent predictors of 30-day mortality and were incorporated into a risk score calculator (MEESSI-AHF). The risk score includes variables such as vital signs, age, labs values, and performance status. A second cohort of 3,229 patients were used to validate the risk score. The risk score effectively discriminates patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients. One important limitation is a high number of missing values in derivation cohort that required advanced statistics to overcome. The generalizability of the population studies (Spanish population) to other countries is still unclear. A risk score that can reasonably identify low-risk patients may be the most clinically useful in order to identify patients that either can be treated effectively in the emergency department and may not warrant inpatient admission.

Bottom line: The MEESSI-AHF risk score may be a helpful tool in identifying the risk of 30-day mortality in patients who present to the ED with AHF, but it is currently unclear if the score can be generalized to other populations.

Citation: Miro O et al. Predicting 30-day mortality for patients with acute heart failure in the emergency department: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 21;167(10):698-705.

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Two scoring systems helpful in diagnosing heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

SAN DIEGO – Both the 4Ts Score and the HIT Expert Probability (HEP) Score are useful in clinical practice for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, but the HEP score may have better operative characteristics in ICU patients, results from a “real world” analysis showed.

“The diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is challenging,” Allyson M. Pishko, MD, one of the study authors, said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “The 4Ts Score is commonly used, but limitations include its low positive predictive value and significant interobserver variability.”

One external prospective study showed operating characteristics similar to those of 4Ts scores (Thromb Haemost 2015;113[3]:633-40).

The aim of the current study was to validate the HEP Score in a “real world” setting and to compare the performance of the HEP Score versus the 4Ts Score. The researchers enrolled 292 adults with suspected acute HIT who were hospitalized at the University of Pennsylvania or affiliated community hospitals, and who had HIT laboratory testing ordered.

The HEP Score and the 4Ts Score were calculated by a member of the clinical team and were completed prior to return of the HIT lab test result. The majority of scorers (62%) were hematology fellows, followed by attendings (35%), and residents/students (3%). All patients underwent testing with an HIT ELISA and serotonin-release assay (SRA). Patients in whom the optical density of the ELISA was less than 0.4 units were classified as not having HIT. The researchers used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare HEP and 4Ts Scores in patients with and without HIT.

Of the 292 patients, 209 were HIT negative and 83 had their data reviewed by an expert panel. Of these 83 patients, 40 were found to be HIT negative and 43 were HIT positive, and their mean ages were 65 years and 63 years, respectively. Among the cases found to be positive for HIT, 93% had HIT ELISA optical density of 1 or greater and 69.7% were SRA positive. The median HEP Score in patients with and without HIT was 8 versus 5 (P less than .0001).

At the prespecified screening cut-off of 2 or more points, the HEP Score was 97.7% sensitive and 21.9% specific, with a positive predictive value of 17.7% and a negative predictive value of 98.2%. A cut-off of 5 or greater provided 90.7% sensitivity and 47.8% specificity with a positive predictive value of 23.1% and a negative predictive value of 96.8%. The mean time to calculate the HEP Score was 4.1 minutes.

The median 4Ts Score in patients with and without HIT was 5 versus 4 (P less than .0001), Dr. Pishko reported. A 4Ts Score of 4 or greater had a sensitivity of 97.7% and specificity of 32.9%, with a positive predictive value of 20.1% and a negative predictive value of 98.8%.

The area under the ROC curves for the HEP Score and 4Ts Score were similar (0.81 vs. 0.76; P = .121). Subset analysis revealed that compared with the 4Ts Score, the HEP Score had better operating characteristics in ICU patients (AUC 0.87 vs. 0.79; P= .029) and with trainee scorers (AUC 0.79 vs. 0.73; P = .032).

“Our data suggest that either the HEP Score or the 4Ts Score could be used in clinical practice,” Dr. Pishko said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Pishko reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pishko A et al. THSNA 2018.

SAN DIEGO – Both the 4Ts Score and the HIT Expert Probability (HEP) Score are useful in clinical practice for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, but the HEP score may have better operative characteristics in ICU patients, results from a “real world” analysis showed.

“The diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is challenging,” Allyson M. Pishko, MD, one of the study authors, said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “The 4Ts Score is commonly used, but limitations include its low positive predictive value and significant interobserver variability.”

One external prospective study showed operating characteristics similar to those of 4Ts scores (Thromb Haemost 2015;113[3]:633-40).

The aim of the current study was to validate the HEP Score in a “real world” setting and to compare the performance of the HEP Score versus the 4Ts Score. The researchers enrolled 292 adults with suspected acute HIT who were hospitalized at the University of Pennsylvania or affiliated community hospitals, and who had HIT laboratory testing ordered.

The HEP Score and the 4Ts Score were calculated by a member of the clinical team and were completed prior to return of the HIT lab test result. The majority of scorers (62%) were hematology fellows, followed by attendings (35%), and residents/students (3%). All patients underwent testing with an HIT ELISA and serotonin-release assay (SRA). Patients in whom the optical density of the ELISA was less than 0.4 units were classified as not having HIT. The researchers used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare HEP and 4Ts Scores in patients with and without HIT.

Of the 292 patients, 209 were HIT negative and 83 had their data reviewed by an expert panel. Of these 83 patients, 40 were found to be HIT negative and 43 were HIT positive, and their mean ages were 65 years and 63 years, respectively. Among the cases found to be positive for HIT, 93% had HIT ELISA optical density of 1 or greater and 69.7% were SRA positive. The median HEP Score in patients with and without HIT was 8 versus 5 (P less than .0001).

At the prespecified screening cut-off of 2 or more points, the HEP Score was 97.7% sensitive and 21.9% specific, with a positive predictive value of 17.7% and a negative predictive value of 98.2%. A cut-off of 5 or greater provided 90.7% sensitivity and 47.8% specificity with a positive predictive value of 23.1% and a negative predictive value of 96.8%. The mean time to calculate the HEP Score was 4.1 minutes.

The median 4Ts Score in patients with and without HIT was 5 versus 4 (P less than .0001), Dr. Pishko reported. A 4Ts Score of 4 or greater had a sensitivity of 97.7% and specificity of 32.9%, with a positive predictive value of 20.1% and a negative predictive value of 98.8%.

The area under the ROC curves for the HEP Score and 4Ts Score were similar (0.81 vs. 0.76; P = .121). Subset analysis revealed that compared with the 4Ts Score, the HEP Score had better operating characteristics in ICU patients (AUC 0.87 vs. 0.79; P= .029) and with trainee scorers (AUC 0.79 vs. 0.73; P = .032).

“Our data suggest that either the HEP Score or the 4Ts Score could be used in clinical practice,” Dr. Pishko said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Pishko reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pishko A et al. THSNA 2018.

SAN DIEGO – Both the 4Ts Score and the HIT Expert Probability (HEP) Score are useful in clinical practice for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, but the HEP score may have better operative characteristics in ICU patients, results from a “real world” analysis showed.

“The diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is challenging,” Allyson M. Pishko, MD, one of the study authors, said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “The 4Ts Score is commonly used, but limitations include its low positive predictive value and significant interobserver variability.”

One external prospective study showed operating characteristics similar to those of 4Ts scores (Thromb Haemost 2015;113[3]:633-40).

The aim of the current study was to validate the HEP Score in a “real world” setting and to compare the performance of the HEP Score versus the 4Ts Score. The researchers enrolled 292 adults with suspected acute HIT who were hospitalized at the University of Pennsylvania or affiliated community hospitals, and who had HIT laboratory testing ordered.

The HEP Score and the 4Ts Score were calculated by a member of the clinical team and were completed prior to return of the HIT lab test result. The majority of scorers (62%) were hematology fellows, followed by attendings (35%), and residents/students (3%). All patients underwent testing with an HIT ELISA and serotonin-release assay (SRA). Patients in whom the optical density of the ELISA was less than 0.4 units were classified as not having HIT. The researchers used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare HEP and 4Ts Scores in patients with and without HIT.

Of the 292 patients, 209 were HIT negative and 83 had their data reviewed by an expert panel. Of these 83 patients, 40 were found to be HIT negative and 43 were HIT positive, and their mean ages were 65 years and 63 years, respectively. Among the cases found to be positive for HIT, 93% had HIT ELISA optical density of 1 or greater and 69.7% were SRA positive. The median HEP Score in patients with and without HIT was 8 versus 5 (P less than .0001).

At the prespecified screening cut-off of 2 or more points, the HEP Score was 97.7% sensitive and 21.9% specific, with a positive predictive value of 17.7% and a negative predictive value of 98.2%. A cut-off of 5 or greater provided 90.7% sensitivity and 47.8% specificity with a positive predictive value of 23.1% and a negative predictive value of 96.8%. The mean time to calculate the HEP Score was 4.1 minutes.

The median 4Ts Score in patients with and without HIT was 5 versus 4 (P less than .0001), Dr. Pishko reported. A 4Ts Score of 4 or greater had a sensitivity of 97.7% and specificity of 32.9%, with a positive predictive value of 20.1% and a negative predictive value of 98.8%.

The area under the ROC curves for the HEP Score and 4Ts Score were similar (0.81 vs. 0.76; P = .121). Subset analysis revealed that compared with the 4Ts Score, the HEP Score had better operating characteristics in ICU patients (AUC 0.87 vs. 0.79; P= .029) and with trainee scorers (AUC 0.79 vs. 0.73; P = .032).

“Our data suggest that either the HEP Score or the 4Ts Score could be used in clinical practice,” Dr. Pishko said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Pishko reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pishko A et al. THSNA 2018.

REPORTING FROM THSNA 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The area under the ROC curves for the HEP Score and 4Ts Score were similar (0.81 vs. 0.76; P = .121).

Study details: A prospective study of 292 adults with suspected acute HIT who were hospitalized at the University of Pennsylvania or affiliated community hospitals.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Pishko reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Pishko A et al. THSNA 2018.

Boosting bedside skills in hands-on session

A low faculty-to-learner ratio helped HM18 attendees get the most from their learning experience in the Sunday pre-conference course “Bedside Procedures for the Hospitalist.”

The pre-course blended live didactic teaching and hands-on training with simulators so participants could not only learn but also review and demonstrate techniques for many common invasive procedures hospitalists encounter in practice.

“Our goal is to make the entire bedside procedures pre-course a unique experience,” course codirector Alyssa Burkhart, MD, of the Billings (Mont.) Clinic, said in an interview before the session.

“We carefully select the curriculum to create a program most relevant to the participants and their day-to-day work in patient care,” said Dr. Burkhart.

“The low faculty-to-learner ratio coupled with ample time to practice under expert guidance separates us from others. ... It’s a privilege to share our love of procedures with this year’s SHM participants,” said Dr. Burkhart, who comoderated the session with Joshua Lenchus, DO, SFHM, of the University of Miami.

An interactive focus on bedside procedures benefits novices and experienced clinicians, said Dr. Lenchus.

The simulation experience involved practice with ultrasound as well as anatomically representative training equipment.

“Our hope is that many hospitalists may once again find that spark of interest in performing more of their own procedures. The interactive sessions embedded within the pre-course are vital to the success of our program. Many other training sessions are didactics based. We strive to keep lecture time to a minimum so that small groups can learn from the expert facilitators,” Dr. Burkhart added.

“Ample hands-on practice time, interactive experience, and direct supervision separate our pre-course from other commercially available offerings,” Dr. Lenchus said.

The agenda kicked off with vascular and intraosseous access in the morning, followed by paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and basic airway management, including the use of supraglottic devices.

Dr. Burkhart noted that the course included two separate practice sessions for vascular access because of the number of technical steps and potential complications. “Attendees typically wish to spend a considerable amount of time on vascular access,” she said. “The intraosseous access station and its exceptional trainers always receive very positive feedback.”

Dr. Burkhart and Dr. Lenchus had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A low faculty-to-learner ratio helped HM18 attendees get the most from their learning experience in the Sunday pre-conference course “Bedside Procedures for the Hospitalist.”

The pre-course blended live didactic teaching and hands-on training with simulators so participants could not only learn but also review and demonstrate techniques for many common invasive procedures hospitalists encounter in practice.

“Our goal is to make the entire bedside procedures pre-course a unique experience,” course codirector Alyssa Burkhart, MD, of the Billings (Mont.) Clinic, said in an interview before the session.

“We carefully select the curriculum to create a program most relevant to the participants and their day-to-day work in patient care,” said Dr. Burkhart.

“The low faculty-to-learner ratio coupled with ample time to practice under expert guidance separates us from others. ... It’s a privilege to share our love of procedures with this year’s SHM participants,” said Dr. Burkhart, who comoderated the session with Joshua Lenchus, DO, SFHM, of the University of Miami.

An interactive focus on bedside procedures benefits novices and experienced clinicians, said Dr. Lenchus.

The simulation experience involved practice with ultrasound as well as anatomically representative training equipment.

“Our hope is that many hospitalists may once again find that spark of interest in performing more of their own procedures. The interactive sessions embedded within the pre-course are vital to the success of our program. Many other training sessions are didactics based. We strive to keep lecture time to a minimum so that small groups can learn from the expert facilitators,” Dr. Burkhart added.

“Ample hands-on practice time, interactive experience, and direct supervision separate our pre-course from other commercially available offerings,” Dr. Lenchus said.

The agenda kicked off with vascular and intraosseous access in the morning, followed by paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and basic airway management, including the use of supraglottic devices.

Dr. Burkhart noted that the course included two separate practice sessions for vascular access because of the number of technical steps and potential complications. “Attendees typically wish to spend a considerable amount of time on vascular access,” she said. “The intraosseous access station and its exceptional trainers always receive very positive feedback.”

Dr. Burkhart and Dr. Lenchus had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A low faculty-to-learner ratio helped HM18 attendees get the most from their learning experience in the Sunday pre-conference course “Bedside Procedures for the Hospitalist.”

The pre-course blended live didactic teaching and hands-on training with simulators so participants could not only learn but also review and demonstrate techniques for many common invasive procedures hospitalists encounter in practice.

“Our goal is to make the entire bedside procedures pre-course a unique experience,” course codirector Alyssa Burkhart, MD, of the Billings (Mont.) Clinic, said in an interview before the session.

“We carefully select the curriculum to create a program most relevant to the participants and their day-to-day work in patient care,” said Dr. Burkhart.

“The low faculty-to-learner ratio coupled with ample time to practice under expert guidance separates us from others. ... It’s a privilege to share our love of procedures with this year’s SHM participants,” said Dr. Burkhart, who comoderated the session with Joshua Lenchus, DO, SFHM, of the University of Miami.

An interactive focus on bedside procedures benefits novices and experienced clinicians, said Dr. Lenchus.

The simulation experience involved practice with ultrasound as well as anatomically representative training equipment.

“Our hope is that many hospitalists may once again find that spark of interest in performing more of their own procedures. The interactive sessions embedded within the pre-course are vital to the success of our program. Many other training sessions are didactics based. We strive to keep lecture time to a minimum so that small groups can learn from the expert facilitators,” Dr. Burkhart added.

“Ample hands-on practice time, interactive experience, and direct supervision separate our pre-course from other commercially available offerings,” Dr. Lenchus said.

The agenda kicked off with vascular and intraosseous access in the morning, followed by paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and basic airway management, including the use of supraglottic devices.

Dr. Burkhart noted that the course included two separate practice sessions for vascular access because of the number of technical steps and potential complications. “Attendees typically wish to spend a considerable amount of time on vascular access,” she said. “The intraosseous access station and its exceptional trainers always receive very positive feedback.”

Dr. Burkhart and Dr. Lenchus had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards

Clinical question: While it is generally thought that ICU wards are not conducive for sleep because of light and noise disruptions, are general wards any better?

Background: Hospitalized patients frequently report poor sleep, partly because of the inpatient environment. Sound level changes (SLCs), rather than the total volumes, are important in disrupting sleep. The World Health Organization recommends that nighttime baseline noise levels do not exceed 30 decibels (dB) and that nighttime noise peaks (i.e., loud noises) do not exceed 40 dB. The circadian rhythm system depends on ambient light to regulate the internal clock. Insufficient and inappropriately timed light exposure can desynchronize the biological clock, thereby negatively affecting sleep quality.

Setting: Tertiary care hospital in La Jolla, Calif.

Synopsis: For approximately 24-72 hours, recordings of sound and light were performed. ICU rooms were louder (hourly averages ranged from 56.1 dB to 60.3 dB) than were non-ICU wards (44.6-55.1 dB). However, SLCs of 17.5 dB or greater were not statistically different (ICU, 203.9 ± 28.8 times; non-ICU, 270.9 ± 39.5; P = .11). In both ICU and non-ICU wards, average daytime light levels were less than 250 lux and generally were brightest in the afternoon. This corresponds to low, office-level lighting, which may not be conducive for maintaining circadian rhythm.

Bottom line: While ICU wards are generally louder than non-ICU wards, sound level changes are equivalent and probably more important concerning sleep disruption. While no significant differences were seen in light levels, the amount and timing of lighting may not be optimal for keeping circadian rhythm.