User login

Regression, depression, and the facts of life

HISTORY: New school, old problems

Mr. E, age 13, was diagnosed with Down syndrome at birth and has mild mental retardation and bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. His pediatrician referred him to our child and adolescent psychiatry clinic for regressed behavior, depression, and apparent psychotic symptoms. He was also having problems sleeping and had begun puberty 8 months earlier.

Five months before referral, Mr. E had graduated from a small elementary school, where he was fully mainstreamed, to a large junior high school, where he spent most of the school day in a functional skills class. About that time, Mr. E began exhibiting nocturnal and daytime enuresis, loss of previously mastered skills, intolerance of novelty and change, and separation difficulty. Although toilet trained at age 7, he started having “accidents” at home, school, and elsewhere. He was reluctant to dress himself, and he resisted going to school.

The youth also talked to himself often and appeared to respond to internal stimuli. He “relived” conversations aloud, described imaginary friends to family and teachers, and spoke to a stuffed dog called Goofy. He would sit and stare into space for up to a half-hour, appearing preoccupied. Family members said he had exhibited these behaviors in grade school but until now appeared to have “outgrown” them.

Once sociable, Mr. E had become increasingly moody, negativistic, and isolative. He spent hours alone in his room. His mother, with whom he was close, reported that he was often angry with her for no apparent reason.

With puberty, his mother noted, Mr. E had begun kissing other developmentally disabled children. He also masturbated, but at his parents’ urging he restricted this activity to his room.

On evaluation, Mr. E was pleasant and outgoing. He had the facial dysmorphia and stature typical of Down syndrome. He smiled often and interacted well, and he attended and adapted to transitions in conversation and activities. His speech was dysarthric (with hyperglossia) and telegraphic; he could speak only four- to five-word sentences.

Was Mr. E exhibiting an adjustment reaction, depression, or a normal developmental response to puberty? Do his psychotic symptoms signal onset of schizophrenia?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Because Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of mental retardation—seen in approximately 1 in 1,000 live births1—pediatricians and child psychiatrists see this disorder fairly frequently.

Regression, a form of coping exhibited by many children, is extremely common in youths with Down syndrome2 and often has a definite—though sometimes unclear—precipitant. We felt Mr. E’s move from a highly responsive, familiar school environment to a far less responsive one that accentuated his differences contributed to many of his symptoms.

Psychosis is less common in Down syndrome than in other developmental disabilities.2 Schizophrenia may occur, but diagnosis is complicated by cognition impairments, test-taking skills, and—in Mr. E’s case—inability to describe disordered thoughts or hallucinations due to poor language skills.3

Self-talk is common in Down syndrome and might be mistaken for psychosis. Note that despite his chronologic age, Mr. E is developmentally a 6-year-old, and self-talk and imaginary friends are considered normal behaviors for a child that age. What’s more, the stress of changing schools may have further compromised his developmental skills.

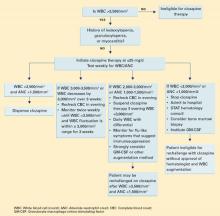

The FDA’s recent advisory about reports of increased suicidality in youths taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants for major depressive disorder during clinical trials has raised questions about using these agents in children and adolescents. Until more data become available, however, SSRIs remain the preferred drug therapy for pediatric depression.

- Based on our experience, we recommend citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, and sertraline as first-line medications for pediatric depression because their side effects are relatively benign. The reported link between increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior and use of paroxetine in pediatric patients has not been clearly established, so we cannot extrapolate that possible risk to other SSRIs.

- Newer antidepressants should be considered with caution in pediatric patients. Bupropion is contraindicated in patients with a history of seizures, bulimia, or anorexia. Mirtazapine is extremely sedating, with side effects such as weight gain and, in rare cases, agranulocytosis. Nefazodone comes with a “black box” warning for risk of liver toxicity. Trazodone is also sedating and carries a risk of priapism in boys.

- Older antidepressants, such as tricyclics, require extreme caution before prescribing to children and adolescents. Tricyclics, with their cardiac side effects, are not recommended for patients with Down syndrome, many of whom have cardiac pathology.

By contrast, depression is fairly common in Down syndrome, although it is much less prevalent in children than in adults with the developmental disorder.2

Finally, children with Down syndrome often enter puberty early, but without the cognitive or emotional maturity or knowledge to deal with the physiologic changes of adolescence.3 Parents often are reluctant to recognize their developmentally disabled child’s sexuality or are uncomfortable providing sexuality education.4 Mr. E’s parents clearly were unconvinced that his sexual behavior was normal for an adolescent.

TREATMENT Antidepressants lead to improvement

We felt Mr. E regressed secondary to emotional stress caused by switching schools. We viewed his psychotic symptoms as part of an adjustment disorder and attributed most of his other symptoms to depression. We anticipated Mr. E’s psychotic symptoms would remit spontaneously and focused on treating his mood and sleep disturbances.

We prescribed sertraline liquid suspension, 10 mg/d titrated across 3 weeks to 40 mg/d. We based our medication choice on clinical experience, mindful of a recent FDA advisory about the use of antidepressants in pediatric patients (Box 1). Also, the liquid suspension is easier to titrate than the tablet form, and we feared Mr. E might have trouble swallowing a tablet.

Mr. E’s mood and sociability improved after 3 to 4 weeks. Within 6 weeks, he regained some of his previously mastered daily activities. We added zolpidem, 10 mg nightly, to address his sleeping difficulties but discontinued the agent after 2 weeks, when his sleep patterns normalized.

At 2, 4, and 6 weeks, Mr. E was pleasant and cooperative, his thinking less concrete, and his speech more intelligible. His parents reported he was happier and more involved with family activities. At his mother’s request, sertraline was changed to 37.5 mg/d in tablet form. The patient remained stable for another month, during which his self-talk, though decreased, continued.

Two weeks later, Mr. E’s mother reported that, during a routine dermatologic examination for a chronic, presacral rash, the dermatologist noticed strategic shaving on the boy’s thighs, calves, and scrotum. Strategic shaving has been reported among sexually active youths as a means of purportedly increasing their sexual pleasure.

The dermatologist then told Mr. E’s mother that her son likely was sexually molested. Based on the boy’s differential rates of pubic hair growth, the doctor suspected that the molestation was chronic, dating back at least 3 months and probably continuing until the week before the examination. Upon hearing this, Mr. E’s parents were stunned and angry.

What behavioral signs might have suggested sexual abuse? How do the dermatologist’s findings alter diagnosis and treatment?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Given the dermatologist’s findings, Mr. E’s parents asked us whether their son’s presenting psychiatric symptoms were manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Until now, explaining Mr. E’s symptoms as a reaction to changing schools seemed plausible. His symptoms were improving with treatment, and his sexual behaviors and interest in sexual topics were physiologically normal for his chronologic age. Despite his earlier pubertal experimentations, nothing in his psychosocial history indicated risk for sexual abuse or exploitation.

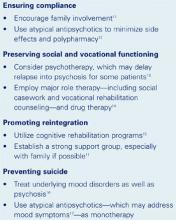

Still, children with Down syndrome are at higher risk for sexual exploitation than other children,4 so the possibility should have been explored with the parents. Psychiatrists should watch for physical signs of sexual abuse in these patients during the first examination (Box 2).4

But how is sexual abuse defined in this case? Deficient language skills prevented Mr. E from describing what happened to him, so determining whether he initiated sexual relations and with whom is nearly impossible. The act clearly could be considered abuse if Mr. E had been with an adult or older child—even if Mr. E consented. However, if Mr. E had initiated contact with another mentally retarded child, then cause, blame, and semantics become unclear. Either way, the incident could have caused PTSD.5

Diagnosing PTSD in non- or semi-verbal or retarded children is extremely difficult.6,7 Unlike adults with PTSD, pre-verbal children might not have recurrent, distressing recollections of the trauma, but symbolic displacement may characterize repetitive play, during which themes are expressed.8

Scheeringa et al have recommended PTSD criteria for preschool children, including:

- social withdrawal

- extreme temper tantrums

- loss of developmental skills

- new separation anxiety

- new onset of aggression

- new fears without obvious links to the trauma.5,6

Treating PTSD in children with developmental disabilities is also difficult. Modalities applicable to adults or mainstream children—such as psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and medications—often do not help developmentally disabled children. For example, Mr. E lacks the cognitive apparatus to respond to CBT.

On the other hand, behavioral therapy, reducing risk factors, minimizing dissociative triggers, and educating patients, parents, friends, and teachers about PTSD can help patients such as Mr. E.5 Attempting to provide structure and maintain routines is a cornerstone of any intervention.

- Aggression

- Anxiety

- Behavior, learning problems at school

- Depression

- Heightened somatic concerns

- Sexualized behavior

- Sleep disturbance

- Withdrawal

FURTHER TREATMENT A family in turmoil

We addressed Mr. E’s symptoms as PTSD-related, though his poor language skills kept us from identifying a trauma. Based on data regarding pediatric PTSD treatment,9 we increased sertraline to 50 mg/d and then to 75 mg/d across 2 weeks.

However, an intense legal investigation brought on by the parents, combined with ensuing tumult within the family, worsened Mr. E’s symptoms. His self-talk became more pronounced and his isolative behavior reappeared, suggesting that the intrusive, repetitive questioning caused him to re-experience the trauma.

We again increased sertraline, to 100 mg/d, and offered supportive therapy to Mr. E. We tried to educate his parents about understanding his symptoms and managing his behavior and strongly recommended that they undergo crisis therapy to keep their reactions and emotions from hurting Mr. E. The parents declined, however, and alleged that we did not adequately support their pursuit of a diagnosis or legal action, which for them had become synonymous with treatment.

Mr. E’s mother brought her son to a psychologist, who engaged him in play therapy. She followed her son around, noting everything he said. All the while, she failed to resolve her guilt and anger. When we explained to her that these actions were hurting Mr. E’s progress, she terminated therapy.

How would you have tried to keep Mr. E’s family in therapy?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Treating psychopathology in children carries the risk of strained relations with the patient’s family. The risk increases exponentially for developmentally disabled children, as they have little or no input and their parents are exquisitely sensitive to their needs. Further, the revelation that the parents might have somehow failed to avert or anticipate danger to the child complicates their emotional response.

Although the child is the patient, the parent is the consumer. Failure to gain or keep the parents’ confidence will hinder or destroy therapy.

We might have protected our working relationship with Mr. E’s parents by recognizing how fragile they were and how intensely they would react to any constructive criticism. Paradoxically, for the short-term we could have tolerated their detrimental behaviors toward Mr. E (such as repeated questioning) in the hopes of protecting a long-term relationship. Spending more time exploring the guilt, anger, and confusion that tormented Mr. E’s parents—particularly his mother—also might have helped.

Related resources

- Ryan RM. Recognition of psychosis in persons who do not use spoken communication. In: Ancill RJ, Holliday S, Higenbottam J (eds). Schizophrenia: exploring the spectrum of psychosis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Pueschel S. Children with Down syndrome. In: Levine M, Carey W, Crocker A, Gross R (eds). Developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1983.

2. Hodapp RM. Down syndrome: developmental, psychiatric, and management issues. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;5:881-94.

3. Feinstein C, Reiss AL. Psychiatric disorder in mentally retarded children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;5:827-52.

4. Wilgosh L. Sexual abuse of children with disabilities: intervention and treatment issues for parents. Developmental Disabil Bull. Available at: http://www.ualberta.ca/~jpdasddc/bulletin/articles/wilgosh1993.html. Accessed Nov. 10, 2003.

5. Ryan RM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with developmental disabilities. Community Health J 1994;30:45-54.

6. Scheeringa MS, Seanah CH, Myers L, Putnam FW. New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:561-70.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed-text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

8. Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Richey JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: diagnosis, assessment, and associated features. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;12:171-94.

9. Donnelly CL. Pharmacological treatment approaches for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;12:251-69.

HISTORY: New school, old problems

Mr. E, age 13, was diagnosed with Down syndrome at birth and has mild mental retardation and bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. His pediatrician referred him to our child and adolescent psychiatry clinic for regressed behavior, depression, and apparent psychotic symptoms. He was also having problems sleeping and had begun puberty 8 months earlier.

Five months before referral, Mr. E had graduated from a small elementary school, where he was fully mainstreamed, to a large junior high school, where he spent most of the school day in a functional skills class. About that time, Mr. E began exhibiting nocturnal and daytime enuresis, loss of previously mastered skills, intolerance of novelty and change, and separation difficulty. Although toilet trained at age 7, he started having “accidents” at home, school, and elsewhere. He was reluctant to dress himself, and he resisted going to school.

The youth also talked to himself often and appeared to respond to internal stimuli. He “relived” conversations aloud, described imaginary friends to family and teachers, and spoke to a stuffed dog called Goofy. He would sit and stare into space for up to a half-hour, appearing preoccupied. Family members said he had exhibited these behaviors in grade school but until now appeared to have “outgrown” them.

Once sociable, Mr. E had become increasingly moody, negativistic, and isolative. He spent hours alone in his room. His mother, with whom he was close, reported that he was often angry with her for no apparent reason.

With puberty, his mother noted, Mr. E had begun kissing other developmentally disabled children. He also masturbated, but at his parents’ urging he restricted this activity to his room.

On evaluation, Mr. E was pleasant and outgoing. He had the facial dysmorphia and stature typical of Down syndrome. He smiled often and interacted well, and he attended and adapted to transitions in conversation and activities. His speech was dysarthric (with hyperglossia) and telegraphic; he could speak only four- to five-word sentences.

Was Mr. E exhibiting an adjustment reaction, depression, or a normal developmental response to puberty? Do his psychotic symptoms signal onset of schizophrenia?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Because Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of mental retardation—seen in approximately 1 in 1,000 live births1—pediatricians and child psychiatrists see this disorder fairly frequently.

Regression, a form of coping exhibited by many children, is extremely common in youths with Down syndrome2 and often has a definite—though sometimes unclear—precipitant. We felt Mr. E’s move from a highly responsive, familiar school environment to a far less responsive one that accentuated his differences contributed to many of his symptoms.

Psychosis is less common in Down syndrome than in other developmental disabilities.2 Schizophrenia may occur, but diagnosis is complicated by cognition impairments, test-taking skills, and—in Mr. E’s case—inability to describe disordered thoughts or hallucinations due to poor language skills.3

Self-talk is common in Down syndrome and might be mistaken for psychosis. Note that despite his chronologic age, Mr. E is developmentally a 6-year-old, and self-talk and imaginary friends are considered normal behaviors for a child that age. What’s more, the stress of changing schools may have further compromised his developmental skills.

The FDA’s recent advisory about reports of increased suicidality in youths taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants for major depressive disorder during clinical trials has raised questions about using these agents in children and adolescents. Until more data become available, however, SSRIs remain the preferred drug therapy for pediatric depression.

- Based on our experience, we recommend citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, and sertraline as first-line medications for pediatric depression because their side effects are relatively benign. The reported link between increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior and use of paroxetine in pediatric patients has not been clearly established, so we cannot extrapolate that possible risk to other SSRIs.

- Newer antidepressants should be considered with caution in pediatric patients. Bupropion is contraindicated in patients with a history of seizures, bulimia, or anorexia. Mirtazapine is extremely sedating, with side effects such as weight gain and, in rare cases, agranulocytosis. Nefazodone comes with a “black box” warning for risk of liver toxicity. Trazodone is also sedating and carries a risk of priapism in boys.

- Older antidepressants, such as tricyclics, require extreme caution before prescribing to children and adolescents. Tricyclics, with their cardiac side effects, are not recommended for patients with Down syndrome, many of whom have cardiac pathology.

By contrast, depression is fairly common in Down syndrome, although it is much less prevalent in children than in adults with the developmental disorder.2

Finally, children with Down syndrome often enter puberty early, but without the cognitive or emotional maturity or knowledge to deal with the physiologic changes of adolescence.3 Parents often are reluctant to recognize their developmentally disabled child’s sexuality or are uncomfortable providing sexuality education.4 Mr. E’s parents clearly were unconvinced that his sexual behavior was normal for an adolescent.

TREATMENT Antidepressants lead to improvement

We felt Mr. E regressed secondary to emotional stress caused by switching schools. We viewed his psychotic symptoms as part of an adjustment disorder and attributed most of his other symptoms to depression. We anticipated Mr. E’s psychotic symptoms would remit spontaneously and focused on treating his mood and sleep disturbances.

We prescribed sertraline liquid suspension, 10 mg/d titrated across 3 weeks to 40 mg/d. We based our medication choice on clinical experience, mindful of a recent FDA advisory about the use of antidepressants in pediatric patients (Box 1). Also, the liquid suspension is easier to titrate than the tablet form, and we feared Mr. E might have trouble swallowing a tablet.

Mr. E’s mood and sociability improved after 3 to 4 weeks. Within 6 weeks, he regained some of his previously mastered daily activities. We added zolpidem, 10 mg nightly, to address his sleeping difficulties but discontinued the agent after 2 weeks, when his sleep patterns normalized.

At 2, 4, and 6 weeks, Mr. E was pleasant and cooperative, his thinking less concrete, and his speech more intelligible. His parents reported he was happier and more involved with family activities. At his mother’s request, sertraline was changed to 37.5 mg/d in tablet form. The patient remained stable for another month, during which his self-talk, though decreased, continued.

Two weeks later, Mr. E’s mother reported that, during a routine dermatologic examination for a chronic, presacral rash, the dermatologist noticed strategic shaving on the boy’s thighs, calves, and scrotum. Strategic shaving has been reported among sexually active youths as a means of purportedly increasing their sexual pleasure.

The dermatologist then told Mr. E’s mother that her son likely was sexually molested. Based on the boy’s differential rates of pubic hair growth, the doctor suspected that the molestation was chronic, dating back at least 3 months and probably continuing until the week before the examination. Upon hearing this, Mr. E’s parents were stunned and angry.

What behavioral signs might have suggested sexual abuse? How do the dermatologist’s findings alter diagnosis and treatment?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Given the dermatologist’s findings, Mr. E’s parents asked us whether their son’s presenting psychiatric symptoms were manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Until now, explaining Mr. E’s symptoms as a reaction to changing schools seemed plausible. His symptoms were improving with treatment, and his sexual behaviors and interest in sexual topics were physiologically normal for his chronologic age. Despite his earlier pubertal experimentations, nothing in his psychosocial history indicated risk for sexual abuse or exploitation.

Still, children with Down syndrome are at higher risk for sexual exploitation than other children,4 so the possibility should have been explored with the parents. Psychiatrists should watch for physical signs of sexual abuse in these patients during the first examination (Box 2).4

But how is sexual abuse defined in this case? Deficient language skills prevented Mr. E from describing what happened to him, so determining whether he initiated sexual relations and with whom is nearly impossible. The act clearly could be considered abuse if Mr. E had been with an adult or older child—even if Mr. E consented. However, if Mr. E had initiated contact with another mentally retarded child, then cause, blame, and semantics become unclear. Either way, the incident could have caused PTSD.5

Diagnosing PTSD in non- or semi-verbal or retarded children is extremely difficult.6,7 Unlike adults with PTSD, pre-verbal children might not have recurrent, distressing recollections of the trauma, but symbolic displacement may characterize repetitive play, during which themes are expressed.8

Scheeringa et al have recommended PTSD criteria for preschool children, including:

- social withdrawal

- extreme temper tantrums

- loss of developmental skills

- new separation anxiety

- new onset of aggression

- new fears without obvious links to the trauma.5,6

Treating PTSD in children with developmental disabilities is also difficult. Modalities applicable to adults or mainstream children—such as psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and medications—often do not help developmentally disabled children. For example, Mr. E lacks the cognitive apparatus to respond to CBT.

On the other hand, behavioral therapy, reducing risk factors, minimizing dissociative triggers, and educating patients, parents, friends, and teachers about PTSD can help patients such as Mr. E.5 Attempting to provide structure and maintain routines is a cornerstone of any intervention.

- Aggression

- Anxiety

- Behavior, learning problems at school

- Depression

- Heightened somatic concerns

- Sexualized behavior

- Sleep disturbance

- Withdrawal

FURTHER TREATMENT A family in turmoil

We addressed Mr. E’s symptoms as PTSD-related, though his poor language skills kept us from identifying a trauma. Based on data regarding pediatric PTSD treatment,9 we increased sertraline to 50 mg/d and then to 75 mg/d across 2 weeks.

However, an intense legal investigation brought on by the parents, combined with ensuing tumult within the family, worsened Mr. E’s symptoms. His self-talk became more pronounced and his isolative behavior reappeared, suggesting that the intrusive, repetitive questioning caused him to re-experience the trauma.

We again increased sertraline, to 100 mg/d, and offered supportive therapy to Mr. E. We tried to educate his parents about understanding his symptoms and managing his behavior and strongly recommended that they undergo crisis therapy to keep their reactions and emotions from hurting Mr. E. The parents declined, however, and alleged that we did not adequately support their pursuit of a diagnosis or legal action, which for them had become synonymous with treatment.

Mr. E’s mother brought her son to a psychologist, who engaged him in play therapy. She followed her son around, noting everything he said. All the while, she failed to resolve her guilt and anger. When we explained to her that these actions were hurting Mr. E’s progress, she terminated therapy.

How would you have tried to keep Mr. E’s family in therapy?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Treating psychopathology in children carries the risk of strained relations with the patient’s family. The risk increases exponentially for developmentally disabled children, as they have little or no input and their parents are exquisitely sensitive to their needs. Further, the revelation that the parents might have somehow failed to avert or anticipate danger to the child complicates their emotional response.

Although the child is the patient, the parent is the consumer. Failure to gain or keep the parents’ confidence will hinder or destroy therapy.

We might have protected our working relationship with Mr. E’s parents by recognizing how fragile they were and how intensely they would react to any constructive criticism. Paradoxically, for the short-term we could have tolerated their detrimental behaviors toward Mr. E (such as repeated questioning) in the hopes of protecting a long-term relationship. Spending more time exploring the guilt, anger, and confusion that tormented Mr. E’s parents—particularly his mother—also might have helped.

Related resources

- Ryan RM. Recognition of psychosis in persons who do not use spoken communication. In: Ancill RJ, Holliday S, Higenbottam J (eds). Schizophrenia: exploring the spectrum of psychosis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

HISTORY: New school, old problems

Mr. E, age 13, was diagnosed with Down syndrome at birth and has mild mental retardation and bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. His pediatrician referred him to our child and adolescent psychiatry clinic for regressed behavior, depression, and apparent psychotic symptoms. He was also having problems sleeping and had begun puberty 8 months earlier.

Five months before referral, Mr. E had graduated from a small elementary school, where he was fully mainstreamed, to a large junior high school, where he spent most of the school day in a functional skills class. About that time, Mr. E began exhibiting nocturnal and daytime enuresis, loss of previously mastered skills, intolerance of novelty and change, and separation difficulty. Although toilet trained at age 7, he started having “accidents” at home, school, and elsewhere. He was reluctant to dress himself, and he resisted going to school.

The youth also talked to himself often and appeared to respond to internal stimuli. He “relived” conversations aloud, described imaginary friends to family and teachers, and spoke to a stuffed dog called Goofy. He would sit and stare into space for up to a half-hour, appearing preoccupied. Family members said he had exhibited these behaviors in grade school but until now appeared to have “outgrown” them.

Once sociable, Mr. E had become increasingly moody, negativistic, and isolative. He spent hours alone in his room. His mother, with whom he was close, reported that he was often angry with her for no apparent reason.

With puberty, his mother noted, Mr. E had begun kissing other developmentally disabled children. He also masturbated, but at his parents’ urging he restricted this activity to his room.

On evaluation, Mr. E was pleasant and outgoing. He had the facial dysmorphia and stature typical of Down syndrome. He smiled often and interacted well, and he attended and adapted to transitions in conversation and activities. His speech was dysarthric (with hyperglossia) and telegraphic; he could speak only four- to five-word sentences.

Was Mr. E exhibiting an adjustment reaction, depression, or a normal developmental response to puberty? Do his psychotic symptoms signal onset of schizophrenia?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Because Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of mental retardation—seen in approximately 1 in 1,000 live births1—pediatricians and child psychiatrists see this disorder fairly frequently.

Regression, a form of coping exhibited by many children, is extremely common in youths with Down syndrome2 and often has a definite—though sometimes unclear—precipitant. We felt Mr. E’s move from a highly responsive, familiar school environment to a far less responsive one that accentuated his differences contributed to many of his symptoms.

Psychosis is less common in Down syndrome than in other developmental disabilities.2 Schizophrenia may occur, but diagnosis is complicated by cognition impairments, test-taking skills, and—in Mr. E’s case—inability to describe disordered thoughts or hallucinations due to poor language skills.3

Self-talk is common in Down syndrome and might be mistaken for psychosis. Note that despite his chronologic age, Mr. E is developmentally a 6-year-old, and self-talk and imaginary friends are considered normal behaviors for a child that age. What’s more, the stress of changing schools may have further compromised his developmental skills.

The FDA’s recent advisory about reports of increased suicidality in youths taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants for major depressive disorder during clinical trials has raised questions about using these agents in children and adolescents. Until more data become available, however, SSRIs remain the preferred drug therapy for pediatric depression.

- Based on our experience, we recommend citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, and sertraline as first-line medications for pediatric depression because their side effects are relatively benign. The reported link between increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior and use of paroxetine in pediatric patients has not been clearly established, so we cannot extrapolate that possible risk to other SSRIs.

- Newer antidepressants should be considered with caution in pediatric patients. Bupropion is contraindicated in patients with a history of seizures, bulimia, or anorexia. Mirtazapine is extremely sedating, with side effects such as weight gain and, in rare cases, agranulocytosis. Nefazodone comes with a “black box” warning for risk of liver toxicity. Trazodone is also sedating and carries a risk of priapism in boys.

- Older antidepressants, such as tricyclics, require extreme caution before prescribing to children and adolescents. Tricyclics, with their cardiac side effects, are not recommended for patients with Down syndrome, many of whom have cardiac pathology.

By contrast, depression is fairly common in Down syndrome, although it is much less prevalent in children than in adults with the developmental disorder.2

Finally, children with Down syndrome often enter puberty early, but without the cognitive or emotional maturity or knowledge to deal with the physiologic changes of adolescence.3 Parents often are reluctant to recognize their developmentally disabled child’s sexuality or are uncomfortable providing sexuality education.4 Mr. E’s parents clearly were unconvinced that his sexual behavior was normal for an adolescent.

TREATMENT Antidepressants lead to improvement

We felt Mr. E regressed secondary to emotional stress caused by switching schools. We viewed his psychotic symptoms as part of an adjustment disorder and attributed most of his other symptoms to depression. We anticipated Mr. E’s psychotic symptoms would remit spontaneously and focused on treating his mood and sleep disturbances.

We prescribed sertraline liquid suspension, 10 mg/d titrated across 3 weeks to 40 mg/d. We based our medication choice on clinical experience, mindful of a recent FDA advisory about the use of antidepressants in pediatric patients (Box 1). Also, the liquid suspension is easier to titrate than the tablet form, and we feared Mr. E might have trouble swallowing a tablet.

Mr. E’s mood and sociability improved after 3 to 4 weeks. Within 6 weeks, he regained some of his previously mastered daily activities. We added zolpidem, 10 mg nightly, to address his sleeping difficulties but discontinued the agent after 2 weeks, when his sleep patterns normalized.

At 2, 4, and 6 weeks, Mr. E was pleasant and cooperative, his thinking less concrete, and his speech more intelligible. His parents reported he was happier and more involved with family activities. At his mother’s request, sertraline was changed to 37.5 mg/d in tablet form. The patient remained stable for another month, during which his self-talk, though decreased, continued.

Two weeks later, Mr. E’s mother reported that, during a routine dermatologic examination for a chronic, presacral rash, the dermatologist noticed strategic shaving on the boy’s thighs, calves, and scrotum. Strategic shaving has been reported among sexually active youths as a means of purportedly increasing their sexual pleasure.

The dermatologist then told Mr. E’s mother that her son likely was sexually molested. Based on the boy’s differential rates of pubic hair growth, the doctor suspected that the molestation was chronic, dating back at least 3 months and probably continuing until the week before the examination. Upon hearing this, Mr. E’s parents were stunned and angry.

What behavioral signs might have suggested sexual abuse? How do the dermatologist’s findings alter diagnosis and treatment?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Given the dermatologist’s findings, Mr. E’s parents asked us whether their son’s presenting psychiatric symptoms were manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Until now, explaining Mr. E’s symptoms as a reaction to changing schools seemed plausible. His symptoms were improving with treatment, and his sexual behaviors and interest in sexual topics were physiologically normal for his chronologic age. Despite his earlier pubertal experimentations, nothing in his psychosocial history indicated risk for sexual abuse or exploitation.

Still, children with Down syndrome are at higher risk for sexual exploitation than other children,4 so the possibility should have been explored with the parents. Psychiatrists should watch for physical signs of sexual abuse in these patients during the first examination (Box 2).4

But how is sexual abuse defined in this case? Deficient language skills prevented Mr. E from describing what happened to him, so determining whether he initiated sexual relations and with whom is nearly impossible. The act clearly could be considered abuse if Mr. E had been with an adult or older child—even if Mr. E consented. However, if Mr. E had initiated contact with another mentally retarded child, then cause, blame, and semantics become unclear. Either way, the incident could have caused PTSD.5

Diagnosing PTSD in non- or semi-verbal or retarded children is extremely difficult.6,7 Unlike adults with PTSD, pre-verbal children might not have recurrent, distressing recollections of the trauma, but symbolic displacement may characterize repetitive play, during which themes are expressed.8

Scheeringa et al have recommended PTSD criteria for preschool children, including:

- social withdrawal

- extreme temper tantrums

- loss of developmental skills

- new separation anxiety

- new onset of aggression

- new fears without obvious links to the trauma.5,6

Treating PTSD in children with developmental disabilities is also difficult. Modalities applicable to adults or mainstream children—such as psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and medications—often do not help developmentally disabled children. For example, Mr. E lacks the cognitive apparatus to respond to CBT.

On the other hand, behavioral therapy, reducing risk factors, minimizing dissociative triggers, and educating patients, parents, friends, and teachers about PTSD can help patients such as Mr. E.5 Attempting to provide structure and maintain routines is a cornerstone of any intervention.

- Aggression

- Anxiety

- Behavior, learning problems at school

- Depression

- Heightened somatic concerns

- Sexualized behavior

- Sleep disturbance

- Withdrawal

FURTHER TREATMENT A family in turmoil

We addressed Mr. E’s symptoms as PTSD-related, though his poor language skills kept us from identifying a trauma. Based on data regarding pediatric PTSD treatment,9 we increased sertraline to 50 mg/d and then to 75 mg/d across 2 weeks.

However, an intense legal investigation brought on by the parents, combined with ensuing tumult within the family, worsened Mr. E’s symptoms. His self-talk became more pronounced and his isolative behavior reappeared, suggesting that the intrusive, repetitive questioning caused him to re-experience the trauma.

We again increased sertraline, to 100 mg/d, and offered supportive therapy to Mr. E. We tried to educate his parents about understanding his symptoms and managing his behavior and strongly recommended that they undergo crisis therapy to keep their reactions and emotions from hurting Mr. E. The parents declined, however, and alleged that we did not adequately support their pursuit of a diagnosis or legal action, which for them had become synonymous with treatment.

Mr. E’s mother brought her son to a psychologist, who engaged him in play therapy. She followed her son around, noting everything he said. All the while, she failed to resolve her guilt and anger. When we explained to her that these actions were hurting Mr. E’s progress, she terminated therapy.

How would you have tried to keep Mr. E’s family in therapy?

Dr. Krassner’s and Kraus’ observations

Treating psychopathology in children carries the risk of strained relations with the patient’s family. The risk increases exponentially for developmentally disabled children, as they have little or no input and their parents are exquisitely sensitive to their needs. Further, the revelation that the parents might have somehow failed to avert or anticipate danger to the child complicates their emotional response.

Although the child is the patient, the parent is the consumer. Failure to gain or keep the parents’ confidence will hinder or destroy therapy.

We might have protected our working relationship with Mr. E’s parents by recognizing how fragile they were and how intensely they would react to any constructive criticism. Paradoxically, for the short-term we could have tolerated their detrimental behaviors toward Mr. E (such as repeated questioning) in the hopes of protecting a long-term relationship. Spending more time exploring the guilt, anger, and confusion that tormented Mr. E’s parents—particularly his mother—also might have helped.

Related resources

- Ryan RM. Recognition of psychosis in persons who do not use spoken communication. In: Ancill RJ, Holliday S, Higenbottam J (eds). Schizophrenia: exploring the spectrum of psychosis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Pueschel S. Children with Down syndrome. In: Levine M, Carey W, Crocker A, Gross R (eds). Developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1983.

2. Hodapp RM. Down syndrome: developmental, psychiatric, and management issues. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;5:881-94.

3. Feinstein C, Reiss AL. Psychiatric disorder in mentally retarded children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;5:827-52.

4. Wilgosh L. Sexual abuse of children with disabilities: intervention and treatment issues for parents. Developmental Disabil Bull. Available at: http://www.ualberta.ca/~jpdasddc/bulletin/articles/wilgosh1993.html. Accessed Nov. 10, 2003.

5. Ryan RM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with developmental disabilities. Community Health J 1994;30:45-54.

6. Scheeringa MS, Seanah CH, Myers L, Putnam FW. New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:561-70.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed-text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

8. Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Richey JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: diagnosis, assessment, and associated features. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;12:171-94.

9. Donnelly CL. Pharmacological treatment approaches for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;12:251-69.

1. Pueschel S. Children with Down syndrome. In: Levine M, Carey W, Crocker A, Gross R (eds). Developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1983.

2. Hodapp RM. Down syndrome: developmental, psychiatric, and management issues. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;5:881-94.

3. Feinstein C, Reiss AL. Psychiatric disorder in mentally retarded children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;5:827-52.

4. Wilgosh L. Sexual abuse of children with disabilities: intervention and treatment issues for parents. Developmental Disabil Bull. Available at: http://www.ualberta.ca/~jpdasddc/bulletin/articles/wilgosh1993.html. Accessed Nov. 10, 2003.

5. Ryan RM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with developmental disabilities. Community Health J 1994;30:45-54.

6. Scheeringa MS, Seanah CH, Myers L, Putnam FW. New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:561-70.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed-text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

8. Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Richey JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: diagnosis, assessment, and associated features. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;12:171-94.

9. Donnelly CL. Pharmacological treatment approaches for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;12:251-69.

Beware the men with toupees

HISTORY: Treatment-refractory depression

Mr. S, age 78, has a history of depression that has not responded to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

According to his niece, Mr. S had become withdrawn, suspicious, and forgetful. Several times over the past year, police found him wandering the streets and brought him to the community hospital’s emergency room.

During one emergency room visit, he complained of decreased appetite, poor sleep, and depressed mood. He was subsequently admitted to the psychiatric unit, where he was treated with ECT and discharged on citalopram, 20 mg/d. His symptoms did not improve and he became ataxic and incontinent of urine.

Mr. S’ family placed him in a nursing home, where he became increasingly paranoid. The attending physician prescribed risperidone, 3 mg/d, with no effect. He was then transferred to our psychiatric facility.

At admission, Mr. S told us that a group of men disguised in toupees and mustaches were out to kill him. He said these men had recently killed his niece—with whom he had just spoken on the phone and had seen at the hospital. He suspected that these men were after his money, hired a woman to impersonate his niece and spy on him, and planned to bury his body and his niece’s in a remote place.

On evaluation, Mr. S was suspicious, guarded, and uncooperative, and often ended conversations abruptly. He denied auditory and visual hallucinations, was not suicidal or homicidal, and denied abusing drugs or alcohol. He said constant fear of his imminent murder left him feeling depressed.

Physical and neurologic exams were unremarkable except for mild ataxia. Mr. S’ Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination score was 19/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment.

Mr. S’ history and behavior suggest depression with psychotic features. Do we have enough information for a diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S is displaying mood symptoms consistent with his prior diagnosis of depression, but with new-onset psychosis as well.

Because of Mr. S’ neurobiologic symptoms, it is improper to diagnose depression with psychotic features without first performing a full medical and neurologic workup. The differential diagnosis needs to include medical and neurologic diagnoses, including:

- delirium secondary to urinary tract infection

- Alzheimer’s and/or vascular dementia

- normal-pressure hydrocephalus

- substance abuse.

A complete dementia and delirium workup and detailed medical history are imperative.

FURTHER HISTORY: Risky behavior

Further history reveals that Mr. S had been having sexual intercourse with prostitutes since his early teens and that this habit continued into his 70s. He had been diagnosed with syphilis in his teens and again in his 50s. Both times he refused to complete the recommended penicillin regimen because he was embarrassed by the diagnosis and had falsely believed that a single penicillin injection would cure him.

Lab tests showed a white blood cell count of 3.5 and a weakly reactive serum venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) reading.

Reporting of syphilis cases in the United States began in 1941.1 At about that time, Yale University and the Mayo Clinic began conducting clinical trials of penicillin in syphilis treatment.2

Thanks to the advent of penicillin, syphilis incidence has declined dramatically since 1943, when 575,593 cases were reported.3 Only 5,979 cases were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000.4 A slight increase in cases, mainly among homosexual men, was reported in 2001.1,4

The AIDS epidemic and the emergence of crack/cocaine use5,6 were believed to have triggered a brief increase in cases that peaked in 1990. This was likely caused by the high-risk sexual behavior observed in individuals with sexually transmitted diseases and the practice of exchanging sex for drugs.6

Could Mr. S’ syphilis—inadequately treated in his youth—be causing his depression and paranoia decades later? If so, how would you confirm this finding?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S has a longstanding history of syphilis secondary to high-risk sexual activity. This, combined with the lab findings and his worsening depression and paranoia, points to possible neurosyphilis.

Syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum., can traverse mucous membranes and abraded skin. Transmission is most common during sexual activity but also occurs through blood transfusions and nonsexual lesion contact and from mother to fetus.

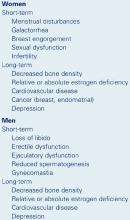

Prevalence

- 6,103 cases reported in 2001

- More prevalent among men than women (2.1:1), probably because of elevated prevalence among homosexual men

- African-Americans accounted for 62% of cases in 2001. Prevalence in African–Americans that year was 16 times greater than in whites

Risk factors

- Presence of HIV infection or other sexually transmitted disease

- Unprotected sex

- Residence in urban areas

- Substance abuse

- Homosexuality

Source: References 5 and 6

Because syphilis and its psychiatric effects are relatively uncommon (Box 1), many psychiatrists do not consider neurosyphilis in high-risk patients who present with depression, dementia, or psychosis (Box 2).

HOW SYPHILIS BECOMES NEUROSYPHILIS

Primary syphilis incubates for 10 to 90 days following infection. After this period, an infectious chancre appears along with regional adenopathy. If untreated, the chancre will disappear but the infection will progress.

Secondary syphilis is characterized by skin manifestations and occasionally affects the joints, eyes, bones, kidneys, liver, and CNS. Common effects include condylomata—highly infectious warty lesions—and a diffuse maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. These lesions disappear if left untreated, but most patients then either enter syphilis’ latent stage or experience a potentially fatal relapse of secondary syphilis.5

Latent syphilis usually remains latent or resolves, but about one-third of patients with latent syphilis slowly progress to tertiary syphilis. Neurosyphilis, one of the main forms of tertiary syphilis, can surface 5 to 35 years after an untreated primary infection.7

There are four categories of neurosyphilis:

- General paresis results in dementia, changes in personality, transient hemiparesis, depression, and psychosis.

- Tabes dorsalis degenerates the posterior columns and dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord. This results in ataxia, parasthesias, decreased proprioception and vibratory sense, Argyll Robertson pupil (an optical disorder in which the pupil does not react normally to light), neurogenic bladder, and sharp shooting pains throughout the body.

- Meningovascular neurosyphilis can result in cranial nerve abnormalities, symptoms of meningitis, and cerebral infarctions.

- Asymptomatic but with CSF positive for syphilis.

Neurosyphilis is fatal if untreated, and treatment usually does not eliminate symptoms but prevents further progression. Approximately 8% of patients with untreated primary syphilis develop neurosyphilis.5,7

Standard nontreponemal tests, such as the VDRL or rapid plasmin reagin, can be used to screen for syphilis. Because these tests often produce false positives, confirm positive results with a syphilis-specific test, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, microhemagglutination assay for antibodies to T pallidum., and the T pallidum. hemagglutination assay.

If neurosyphilis is suspected, CSF testing is strongly recommended. Diagnostic findings include elevated white blood cell and protein counts and a positive VDRL. If the CSF is negative, refer the patient for treatment anyway because false negatives are common. Patients with consistent neurologic symptoms, positive VDRL and/or FTA-ABS, and negative CSF are diagnosed with neurosyphilis and warrant treatment.7

How would you manage Mr. S’ psychiatric symptoms concomitant with medical treatment of late-stage syphilis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Although no specific guidelines exist for treating psychosis secondary to neurosyphilis, atypical antipsychotics remain the first-line treatment. Atypicals do not interact significantly with penicillin and can be given safely with syphilis treatment. Atypicals also are better tolerated than typical antipsychotics and produce fewer extrapyramidal symptoms, which are common among older patients and those with neurologic diseases.

Screening for syphilis. Every patient with a history of high-risk sexual behavior who presents with new-onset dementia or psychosis should be screened for syphilis. Sexual history can be difficult to obtain from some patients and family members, so communication between providers becomes crucial. Obtain lab test results from other care team members to monitor compliance, and coordinate patient education with other doctors on safe sexual practices.

TREATMENT: Taking his medicine

Mr. S refused further testing and emergency conservatorship was sought. Citalopram was discontinued and risperidone was gradually increased to 6 mg at bedtime. He remained paranoid and delusional.

A brain MRI showed chronic ischemic small-vessel disease. HIV testing was negative, and serum FTA-ABS was reactive. CSF showed elevated protein and white blood cell count with a nonreactive VDRL and a reactive FTA-ABS. A diagnosis of neurosyphilis was made, and treatment was initiated with aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 4 million units every 4 hours for 2 weeks.

Mr. S was discharged back to the nursing home where his penicillin injections were continued. His paranoia diminished slightly but he remained ataxic, incontinent, and confused. He was discharged from the nursing home but needed confirmative HIV screening and repeated CSF testing to determine if syphilis treatment was effective.

Six months after treatment, Mr. S’ niece reports that his paranoia has decreased. He has not needed additional psychiatric hospitalizations.

Related resources

- Merck Manual. www.merck.com. Search: “syphilis”

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Syphilis elimination: History in the making. www.cdc.gov. Click on “Health Topics A-Z,” then click on “S” and find “syphilis.”

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. www.niaid.nih.gov. Search: “syphilis”

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2000-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:971-3.

2. Mandell GL, Petri WA. Antimicrobial agents: penicillins, cephalosporins, and other beta-lactam antibiotics. In:Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, et al (eds) Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. (9th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996;1073-4.

3. Lukehart SA, Holmes KK. Spirochetal diseases. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al (eds). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. (14th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998;1023.-

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2001 supplement, syphilis surveillance report. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/2001syphilis.htm. Accessed October 10, 2003.

5. Jacobs RA. Infectious diseases: spirochetal. In: Tierney LM, McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA (eds). Current medical diagnosis and treatment. (39th ed). New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, 2000;1376-86.

6. Hutto B. Syphilis in clinical psychiatry: a review. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:453-60.

7. Carpenter CJ, Lederman MM, Salata RA. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Andreoli TE, Bennett JC, Carpenter CJ, Plum F (eds). Cecil essentials of medicine. (4th ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1997;742-5.

HISTORY: Treatment-refractory depression

Mr. S, age 78, has a history of depression that has not responded to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

According to his niece, Mr. S had become withdrawn, suspicious, and forgetful. Several times over the past year, police found him wandering the streets and brought him to the community hospital’s emergency room.

During one emergency room visit, he complained of decreased appetite, poor sleep, and depressed mood. He was subsequently admitted to the psychiatric unit, where he was treated with ECT and discharged on citalopram, 20 mg/d. His symptoms did not improve and he became ataxic and incontinent of urine.

Mr. S’ family placed him in a nursing home, where he became increasingly paranoid. The attending physician prescribed risperidone, 3 mg/d, with no effect. He was then transferred to our psychiatric facility.

At admission, Mr. S told us that a group of men disguised in toupees and mustaches were out to kill him. He said these men had recently killed his niece—with whom he had just spoken on the phone and had seen at the hospital. He suspected that these men were after his money, hired a woman to impersonate his niece and spy on him, and planned to bury his body and his niece’s in a remote place.

On evaluation, Mr. S was suspicious, guarded, and uncooperative, and often ended conversations abruptly. He denied auditory and visual hallucinations, was not suicidal or homicidal, and denied abusing drugs or alcohol. He said constant fear of his imminent murder left him feeling depressed.

Physical and neurologic exams were unremarkable except for mild ataxia. Mr. S’ Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination score was 19/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment.

Mr. S’ history and behavior suggest depression with psychotic features. Do we have enough information for a diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S is displaying mood symptoms consistent with his prior diagnosis of depression, but with new-onset psychosis as well.

Because of Mr. S’ neurobiologic symptoms, it is improper to diagnose depression with psychotic features without first performing a full medical and neurologic workup. The differential diagnosis needs to include medical and neurologic diagnoses, including:

- delirium secondary to urinary tract infection

- Alzheimer’s and/or vascular dementia

- normal-pressure hydrocephalus

- substance abuse.

A complete dementia and delirium workup and detailed medical history are imperative.

FURTHER HISTORY: Risky behavior

Further history reveals that Mr. S had been having sexual intercourse with prostitutes since his early teens and that this habit continued into his 70s. He had been diagnosed with syphilis in his teens and again in his 50s. Both times he refused to complete the recommended penicillin regimen because he was embarrassed by the diagnosis and had falsely believed that a single penicillin injection would cure him.

Lab tests showed a white blood cell count of 3.5 and a weakly reactive serum venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) reading.

Reporting of syphilis cases in the United States began in 1941.1 At about that time, Yale University and the Mayo Clinic began conducting clinical trials of penicillin in syphilis treatment.2

Thanks to the advent of penicillin, syphilis incidence has declined dramatically since 1943, when 575,593 cases were reported.3 Only 5,979 cases were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000.4 A slight increase in cases, mainly among homosexual men, was reported in 2001.1,4

The AIDS epidemic and the emergence of crack/cocaine use5,6 were believed to have triggered a brief increase in cases that peaked in 1990. This was likely caused by the high-risk sexual behavior observed in individuals with sexually transmitted diseases and the practice of exchanging sex for drugs.6

Could Mr. S’ syphilis—inadequately treated in his youth—be causing his depression and paranoia decades later? If so, how would you confirm this finding?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S has a longstanding history of syphilis secondary to high-risk sexual activity. This, combined with the lab findings and his worsening depression and paranoia, points to possible neurosyphilis.

Syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum., can traverse mucous membranes and abraded skin. Transmission is most common during sexual activity but also occurs through blood transfusions and nonsexual lesion contact and from mother to fetus.

Prevalence

- 6,103 cases reported in 2001

- More prevalent among men than women (2.1:1), probably because of elevated prevalence among homosexual men

- African-Americans accounted for 62% of cases in 2001. Prevalence in African–Americans that year was 16 times greater than in whites

Risk factors

- Presence of HIV infection or other sexually transmitted disease

- Unprotected sex

- Residence in urban areas

- Substance abuse

- Homosexuality

Source: References 5 and 6

Because syphilis and its psychiatric effects are relatively uncommon (Box 1), many psychiatrists do not consider neurosyphilis in high-risk patients who present with depression, dementia, or psychosis (Box 2).

HOW SYPHILIS BECOMES NEUROSYPHILIS

Primary syphilis incubates for 10 to 90 days following infection. After this period, an infectious chancre appears along with regional adenopathy. If untreated, the chancre will disappear but the infection will progress.

Secondary syphilis is characterized by skin manifestations and occasionally affects the joints, eyes, bones, kidneys, liver, and CNS. Common effects include condylomata—highly infectious warty lesions—and a diffuse maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. These lesions disappear if left untreated, but most patients then either enter syphilis’ latent stage or experience a potentially fatal relapse of secondary syphilis.5

Latent syphilis usually remains latent or resolves, but about one-third of patients with latent syphilis slowly progress to tertiary syphilis. Neurosyphilis, one of the main forms of tertiary syphilis, can surface 5 to 35 years after an untreated primary infection.7

There are four categories of neurosyphilis:

- General paresis results in dementia, changes in personality, transient hemiparesis, depression, and psychosis.

- Tabes dorsalis degenerates the posterior columns and dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord. This results in ataxia, parasthesias, decreased proprioception and vibratory sense, Argyll Robertson pupil (an optical disorder in which the pupil does not react normally to light), neurogenic bladder, and sharp shooting pains throughout the body.

- Meningovascular neurosyphilis can result in cranial nerve abnormalities, symptoms of meningitis, and cerebral infarctions.

- Asymptomatic but with CSF positive for syphilis.

Neurosyphilis is fatal if untreated, and treatment usually does not eliminate symptoms but prevents further progression. Approximately 8% of patients with untreated primary syphilis develop neurosyphilis.5,7

Standard nontreponemal tests, such as the VDRL or rapid plasmin reagin, can be used to screen for syphilis. Because these tests often produce false positives, confirm positive results with a syphilis-specific test, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, microhemagglutination assay for antibodies to T pallidum., and the T pallidum. hemagglutination assay.

If neurosyphilis is suspected, CSF testing is strongly recommended. Diagnostic findings include elevated white blood cell and protein counts and a positive VDRL. If the CSF is negative, refer the patient for treatment anyway because false negatives are common. Patients with consistent neurologic symptoms, positive VDRL and/or FTA-ABS, and negative CSF are diagnosed with neurosyphilis and warrant treatment.7

How would you manage Mr. S’ psychiatric symptoms concomitant with medical treatment of late-stage syphilis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Although no specific guidelines exist for treating psychosis secondary to neurosyphilis, atypical antipsychotics remain the first-line treatment. Atypicals do not interact significantly with penicillin and can be given safely with syphilis treatment. Atypicals also are better tolerated than typical antipsychotics and produce fewer extrapyramidal symptoms, which are common among older patients and those with neurologic diseases.

Screening for syphilis. Every patient with a history of high-risk sexual behavior who presents with new-onset dementia or psychosis should be screened for syphilis. Sexual history can be difficult to obtain from some patients and family members, so communication between providers becomes crucial. Obtain lab test results from other care team members to monitor compliance, and coordinate patient education with other doctors on safe sexual practices.

TREATMENT: Taking his medicine

Mr. S refused further testing and emergency conservatorship was sought. Citalopram was discontinued and risperidone was gradually increased to 6 mg at bedtime. He remained paranoid and delusional.

A brain MRI showed chronic ischemic small-vessel disease. HIV testing was negative, and serum FTA-ABS was reactive. CSF showed elevated protein and white blood cell count with a nonreactive VDRL and a reactive FTA-ABS. A diagnosis of neurosyphilis was made, and treatment was initiated with aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 4 million units every 4 hours for 2 weeks.

Mr. S was discharged back to the nursing home where his penicillin injections were continued. His paranoia diminished slightly but he remained ataxic, incontinent, and confused. He was discharged from the nursing home but needed confirmative HIV screening and repeated CSF testing to determine if syphilis treatment was effective.

Six months after treatment, Mr. S’ niece reports that his paranoia has decreased. He has not needed additional psychiatric hospitalizations.

Related resources

- Merck Manual. www.merck.com. Search: “syphilis”

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Syphilis elimination: History in the making. www.cdc.gov. Click on “Health Topics A-Z,” then click on “S” and find “syphilis.”

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. www.niaid.nih.gov. Search: “syphilis”

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

HISTORY: Treatment-refractory depression

Mr. S, age 78, has a history of depression that has not responded to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

According to his niece, Mr. S had become withdrawn, suspicious, and forgetful. Several times over the past year, police found him wandering the streets and brought him to the community hospital’s emergency room.

During one emergency room visit, he complained of decreased appetite, poor sleep, and depressed mood. He was subsequently admitted to the psychiatric unit, where he was treated with ECT and discharged on citalopram, 20 mg/d. His symptoms did not improve and he became ataxic and incontinent of urine.

Mr. S’ family placed him in a nursing home, where he became increasingly paranoid. The attending physician prescribed risperidone, 3 mg/d, with no effect. He was then transferred to our psychiatric facility.

At admission, Mr. S told us that a group of men disguised in toupees and mustaches were out to kill him. He said these men had recently killed his niece—with whom he had just spoken on the phone and had seen at the hospital. He suspected that these men were after his money, hired a woman to impersonate his niece and spy on him, and planned to bury his body and his niece’s in a remote place.

On evaluation, Mr. S was suspicious, guarded, and uncooperative, and often ended conversations abruptly. He denied auditory and visual hallucinations, was not suicidal or homicidal, and denied abusing drugs or alcohol. He said constant fear of his imminent murder left him feeling depressed.

Physical and neurologic exams were unremarkable except for mild ataxia. Mr. S’ Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination score was 19/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment.

Mr. S’ history and behavior suggest depression with psychotic features. Do we have enough information for a diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S is displaying mood symptoms consistent with his prior diagnosis of depression, but with new-onset psychosis as well.

Because of Mr. S’ neurobiologic symptoms, it is improper to diagnose depression with psychotic features without first performing a full medical and neurologic workup. The differential diagnosis needs to include medical and neurologic diagnoses, including:

- delirium secondary to urinary tract infection

- Alzheimer’s and/or vascular dementia

- normal-pressure hydrocephalus

- substance abuse.

A complete dementia and delirium workup and detailed medical history are imperative.

FURTHER HISTORY: Risky behavior

Further history reveals that Mr. S had been having sexual intercourse with prostitutes since his early teens and that this habit continued into his 70s. He had been diagnosed with syphilis in his teens and again in his 50s. Both times he refused to complete the recommended penicillin regimen because he was embarrassed by the diagnosis and had falsely believed that a single penicillin injection would cure him.

Lab tests showed a white blood cell count of 3.5 and a weakly reactive serum venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) reading.

Reporting of syphilis cases in the United States began in 1941.1 At about that time, Yale University and the Mayo Clinic began conducting clinical trials of penicillin in syphilis treatment.2

Thanks to the advent of penicillin, syphilis incidence has declined dramatically since 1943, when 575,593 cases were reported.3 Only 5,979 cases were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000.4 A slight increase in cases, mainly among homosexual men, was reported in 2001.1,4

The AIDS epidemic and the emergence of crack/cocaine use5,6 were believed to have triggered a brief increase in cases that peaked in 1990. This was likely caused by the high-risk sexual behavior observed in individuals with sexually transmitted diseases and the practice of exchanging sex for drugs.6

Could Mr. S’ syphilis—inadequately treated in his youth—be causing his depression and paranoia decades later? If so, how would you confirm this finding?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S has a longstanding history of syphilis secondary to high-risk sexual activity. This, combined with the lab findings and his worsening depression and paranoia, points to possible neurosyphilis.

Syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum., can traverse mucous membranes and abraded skin. Transmission is most common during sexual activity but also occurs through blood transfusions and nonsexual lesion contact and from mother to fetus.

Prevalence

- 6,103 cases reported in 2001

- More prevalent among men than women (2.1:1), probably because of elevated prevalence among homosexual men

- African-Americans accounted for 62% of cases in 2001. Prevalence in African–Americans that year was 16 times greater than in whites

Risk factors

- Presence of HIV infection or other sexually transmitted disease

- Unprotected sex

- Residence in urban areas

- Substance abuse

- Homosexuality

Source: References 5 and 6

Because syphilis and its psychiatric effects are relatively uncommon (Box 1), many psychiatrists do not consider neurosyphilis in high-risk patients who present with depression, dementia, or psychosis (Box 2).

HOW SYPHILIS BECOMES NEUROSYPHILIS

Primary syphilis incubates for 10 to 90 days following infection. After this period, an infectious chancre appears along with regional adenopathy. If untreated, the chancre will disappear but the infection will progress.

Secondary syphilis is characterized by skin manifestations and occasionally affects the joints, eyes, bones, kidneys, liver, and CNS. Common effects include condylomata—highly infectious warty lesions—and a diffuse maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. These lesions disappear if left untreated, but most patients then either enter syphilis’ latent stage or experience a potentially fatal relapse of secondary syphilis.5

Latent syphilis usually remains latent or resolves, but about one-third of patients with latent syphilis slowly progress to tertiary syphilis. Neurosyphilis, one of the main forms of tertiary syphilis, can surface 5 to 35 years after an untreated primary infection.7

There are four categories of neurosyphilis:

- General paresis results in dementia, changes in personality, transient hemiparesis, depression, and psychosis.

- Tabes dorsalis degenerates the posterior columns and dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord. This results in ataxia, parasthesias, decreased proprioception and vibratory sense, Argyll Robertson pupil (an optical disorder in which the pupil does not react normally to light), neurogenic bladder, and sharp shooting pains throughout the body.

- Meningovascular neurosyphilis can result in cranial nerve abnormalities, symptoms of meningitis, and cerebral infarctions.

- Asymptomatic but with CSF positive for syphilis.

Neurosyphilis is fatal if untreated, and treatment usually does not eliminate symptoms but prevents further progression. Approximately 8% of patients with untreated primary syphilis develop neurosyphilis.5,7

Standard nontreponemal tests, such as the VDRL or rapid plasmin reagin, can be used to screen for syphilis. Because these tests often produce false positives, confirm positive results with a syphilis-specific test, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, microhemagglutination assay for antibodies to T pallidum., and the T pallidum. hemagglutination assay.

If neurosyphilis is suspected, CSF testing is strongly recommended. Diagnostic findings include elevated white blood cell and protein counts and a positive VDRL. If the CSF is negative, refer the patient for treatment anyway because false negatives are common. Patients with consistent neurologic symptoms, positive VDRL and/or FTA-ABS, and negative CSF are diagnosed with neurosyphilis and warrant treatment.7

How would you manage Mr. S’ psychiatric symptoms concomitant with medical treatment of late-stage syphilis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Although no specific guidelines exist for treating psychosis secondary to neurosyphilis, atypical antipsychotics remain the first-line treatment. Atypicals do not interact significantly with penicillin and can be given safely with syphilis treatment. Atypicals also are better tolerated than typical antipsychotics and produce fewer extrapyramidal symptoms, which are common among older patients and those with neurologic diseases.

Screening for syphilis. Every patient with a history of high-risk sexual behavior who presents with new-onset dementia or psychosis should be screened for syphilis. Sexual history can be difficult to obtain from some patients and family members, so communication between providers becomes crucial. Obtain lab test results from other care team members to monitor compliance, and coordinate patient education with other doctors on safe sexual practices.

TREATMENT: Taking his medicine

Mr. S refused further testing and emergency conservatorship was sought. Citalopram was discontinued and risperidone was gradually increased to 6 mg at bedtime. He remained paranoid and delusional.

A brain MRI showed chronic ischemic small-vessel disease. HIV testing was negative, and serum FTA-ABS was reactive. CSF showed elevated protein and white blood cell count with a nonreactive VDRL and a reactive FTA-ABS. A diagnosis of neurosyphilis was made, and treatment was initiated with aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 4 million units every 4 hours for 2 weeks.

Mr. S was discharged back to the nursing home where his penicillin injections were continued. His paranoia diminished slightly but he remained ataxic, incontinent, and confused. He was discharged from the nursing home but needed confirmative HIV screening and repeated CSF testing to determine if syphilis treatment was effective.

Six months after treatment, Mr. S’ niece reports that his paranoia has decreased. He has not needed additional psychiatric hospitalizations.

Related resources