User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Warning: Watch out for ‘medication substitution reaction’

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) recently started medical school, and one of the first things we learned in our Human Dimension class was to listen to our patients. While this may seem prosaic to seasoned practitioners, I quickly realized the important, real-world consequences of doing so.

Clinicians rightfully presume that when they send a prescription to a pharmacy, the patient will receive what they have ordered or the generic equivalent unless it is ordered “Dispense as written.” Unfortunately, a confluence of increased demand and supply chain disruptions has produced nationwide shortages of generic Adderall extended-release (XR) and Adderall, which are commonly prescribed to patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 While pharmacies should notify patients when they do not have these medications in stock, we have encountered numerous cases where due to shortages, prescriptions for generic dextroamphetamine/amphetamine salts XR or immediate-release (IR) have been filled with the same milligrams of only dextroamphetamine XR or IR, respectively, without notifying the patient or the prescribing clinician. Pharmacies have included several national chains and local independent stores in the New York/New Jersey region.

Over the past several months, we have encountered patients who had been well stabilized on their ADHD medication regimen who began to report anxiety, jitteriness, agitation, fatigue, poor concentration, and/or hyperactivity, and who also reported that their pills “look different.” First, we considered their symptoms could be attributed to a switch between generic manufacturers. However, upon further inspection, we discovered that the medication name printed on the label was different from what had been prescribed. We confirmed this by checking the Prescription Monitoring Program database.

Pharmacists have recently won prescribing privileges for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) to treat COVID-19, but they certainly are not permitted to fill prescriptions for psychoactive controlled substances that have different pharmacologic profiles than the medication the clinician ordered. Adderall contains D-amphetamine and L-amphetamine in a ratio of 3:1, which makes it different in potency from dextroamphetamine alone and requires adjustment to the dosage and potentially to the frequency to achieve near equivalency.

Once we realized the issue and helped our patients locate a pharmacy that had generic Adderall XR and Adderall in stock so they could resume their previous regimen, their symptoms resolved.

It is important for all clinicians to add “medication substitution reaction” to their differential diagnosis of new-onset ADHD-related symptoms in previously stable patients.

1. Pharmaceutical Commerce. Innovative solutions for pandemic-driven pharmacy drug shortages. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/innovative-solutions-for-pandemic-driven-pharmacy-drug-shortages

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) recently started medical school, and one of the first things we learned in our Human Dimension class was to listen to our patients. While this may seem prosaic to seasoned practitioners, I quickly realized the important, real-world consequences of doing so.

Clinicians rightfully presume that when they send a prescription to a pharmacy, the patient will receive what they have ordered or the generic equivalent unless it is ordered “Dispense as written.” Unfortunately, a confluence of increased demand and supply chain disruptions has produced nationwide shortages of generic Adderall extended-release (XR) and Adderall, which are commonly prescribed to patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 While pharmacies should notify patients when they do not have these medications in stock, we have encountered numerous cases where due to shortages, prescriptions for generic dextroamphetamine/amphetamine salts XR or immediate-release (IR) have been filled with the same milligrams of only dextroamphetamine XR or IR, respectively, without notifying the patient or the prescribing clinician. Pharmacies have included several national chains and local independent stores in the New York/New Jersey region.

Over the past several months, we have encountered patients who had been well stabilized on their ADHD medication regimen who began to report anxiety, jitteriness, agitation, fatigue, poor concentration, and/or hyperactivity, and who also reported that their pills “look different.” First, we considered their symptoms could be attributed to a switch between generic manufacturers. However, upon further inspection, we discovered that the medication name printed on the label was different from what had been prescribed. We confirmed this by checking the Prescription Monitoring Program database.

Pharmacists have recently won prescribing privileges for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) to treat COVID-19, but they certainly are not permitted to fill prescriptions for psychoactive controlled substances that have different pharmacologic profiles than the medication the clinician ordered. Adderall contains D-amphetamine and L-amphetamine in a ratio of 3:1, which makes it different in potency from dextroamphetamine alone and requires adjustment to the dosage and potentially to the frequency to achieve near equivalency.

Once we realized the issue and helped our patients locate a pharmacy that had generic Adderall XR and Adderall in stock so they could resume their previous regimen, their symptoms resolved.

It is important for all clinicians to add “medication substitution reaction” to their differential diagnosis of new-onset ADHD-related symptoms in previously stable patients.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) recently started medical school, and one of the first things we learned in our Human Dimension class was to listen to our patients. While this may seem prosaic to seasoned practitioners, I quickly realized the important, real-world consequences of doing so.

Clinicians rightfully presume that when they send a prescription to a pharmacy, the patient will receive what they have ordered or the generic equivalent unless it is ordered “Dispense as written.” Unfortunately, a confluence of increased demand and supply chain disruptions has produced nationwide shortages of generic Adderall extended-release (XR) and Adderall, which are commonly prescribed to patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 While pharmacies should notify patients when they do not have these medications in stock, we have encountered numerous cases where due to shortages, prescriptions for generic dextroamphetamine/amphetamine salts XR or immediate-release (IR) have been filled with the same milligrams of only dextroamphetamine XR or IR, respectively, without notifying the patient or the prescribing clinician. Pharmacies have included several national chains and local independent stores in the New York/New Jersey region.

Over the past several months, we have encountered patients who had been well stabilized on their ADHD medication regimen who began to report anxiety, jitteriness, agitation, fatigue, poor concentration, and/or hyperactivity, and who also reported that their pills “look different.” First, we considered their symptoms could be attributed to a switch between generic manufacturers. However, upon further inspection, we discovered that the medication name printed on the label was different from what had been prescribed. We confirmed this by checking the Prescription Monitoring Program database.

Pharmacists have recently won prescribing privileges for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) to treat COVID-19, but they certainly are not permitted to fill prescriptions for psychoactive controlled substances that have different pharmacologic profiles than the medication the clinician ordered. Adderall contains D-amphetamine and L-amphetamine in a ratio of 3:1, which makes it different in potency from dextroamphetamine alone and requires adjustment to the dosage and potentially to the frequency to achieve near equivalency.

Once we realized the issue and helped our patients locate a pharmacy that had generic Adderall XR and Adderall in stock so they could resume their previous regimen, their symptoms resolved.

It is important for all clinicians to add “medication substitution reaction” to their differential diagnosis of new-onset ADHD-related symptoms in previously stable patients.

1. Pharmaceutical Commerce. Innovative solutions for pandemic-driven pharmacy drug shortages. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/innovative-solutions-for-pandemic-driven-pharmacy-drug-shortages

1. Pharmaceutical Commerce. Innovative solutions for pandemic-driven pharmacy drug shortages. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/innovative-solutions-for-pandemic-driven-pharmacy-drug-shortages

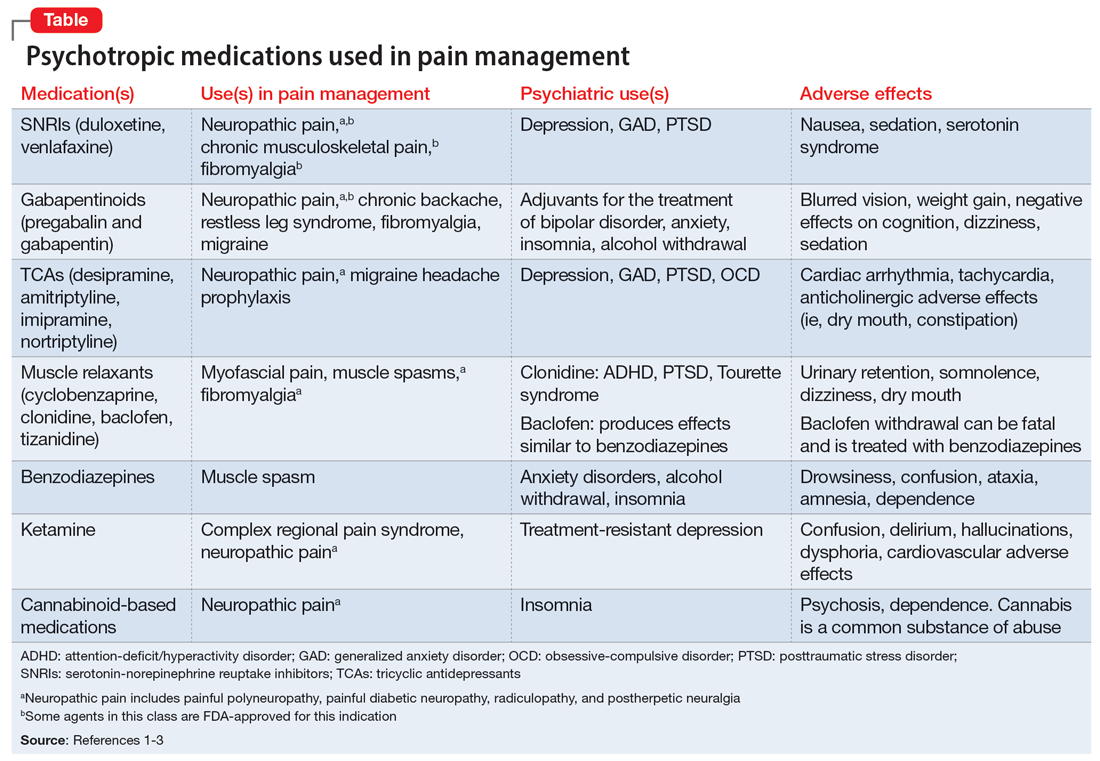

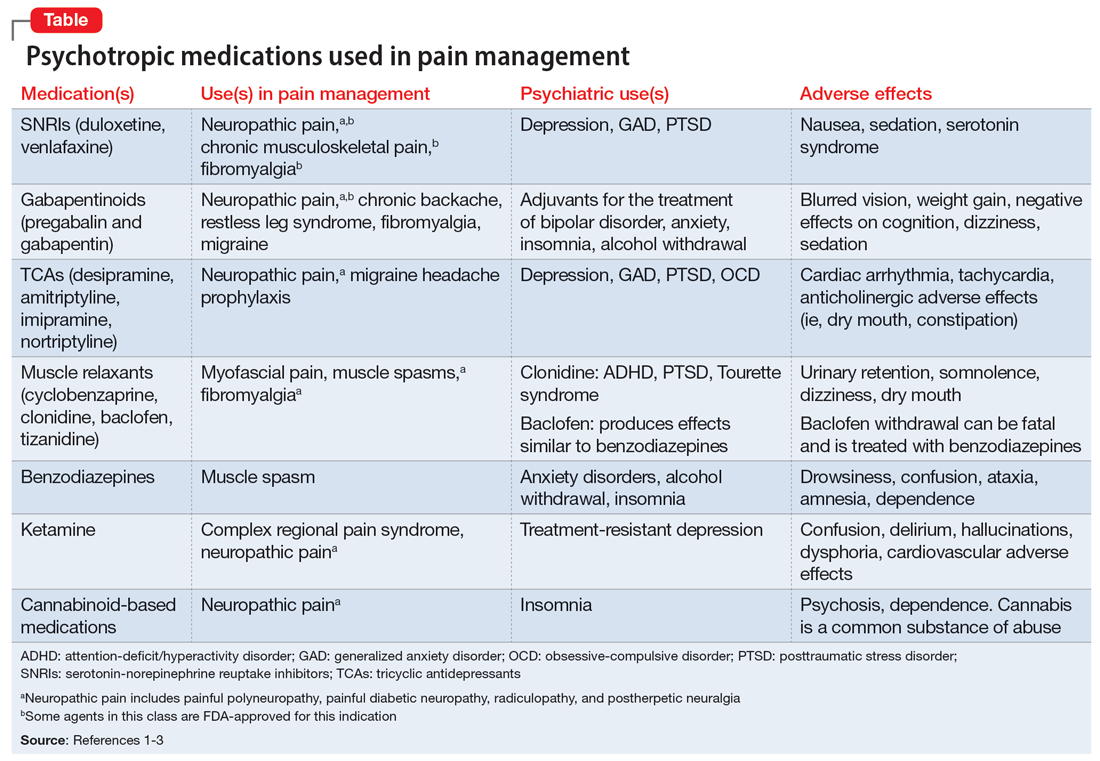

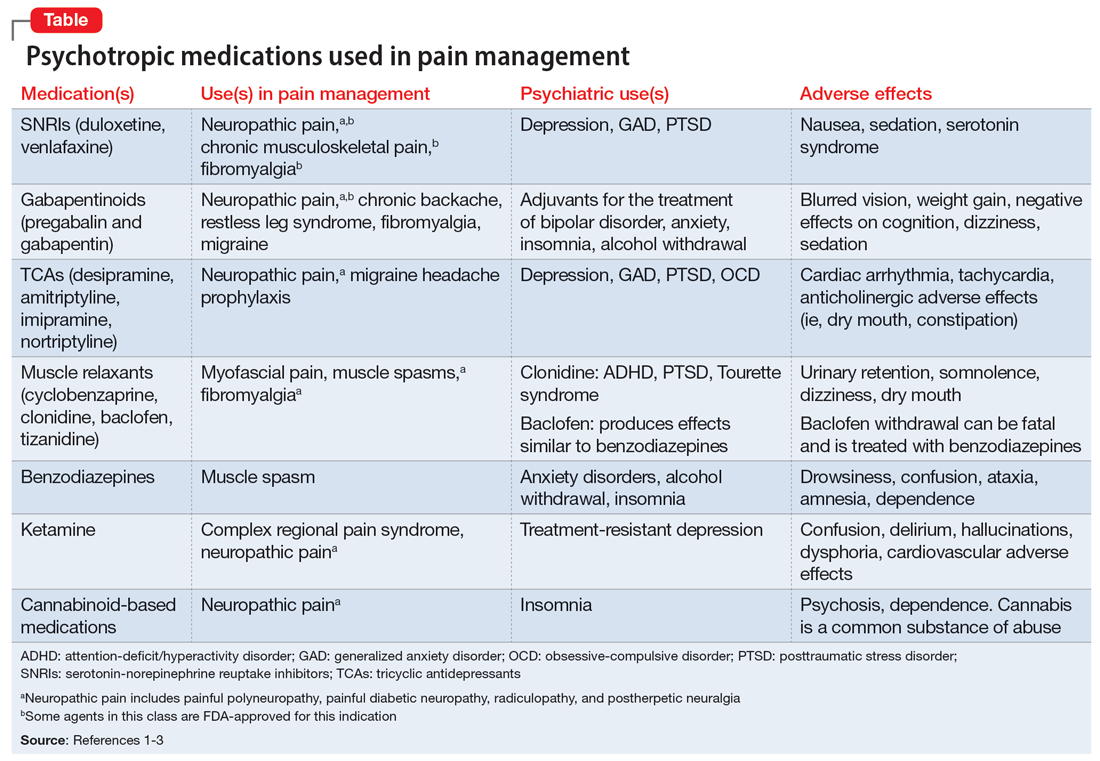

Psychotropic medications for chronic pain

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

The light at the end of the tunnel: Reflecting on a 7-year training journey

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

Lamotrigine for bipolar depression?

In reading Dr. Nasrallah's August 2022 editorial (“Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms,”

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thanks for your message. Lamotrigine is not FDA-approved for bipolar or unipolar depression, either as monotherapy or as an adjunctive therapy. It has never been approved for mania, either (no efficacy at all). Its only FDA-approved psychiatric indication is maintenance therapy after a patient with bipolar I disorder emerges from mania with the help of one of the antimanic drugs. Yet many clinicians may perceive lamotrigine as useful for bipolar depression because more than 20 years ago the manufacturer sponsored several small studies (not FDA trials). Two studies that showed efficacy were published, but 4 other studies that failed to show efficacy were not published. As a result, many clinicians got the false impression that lamotrigine is an effective antidepressant. I hope this explains why lamotrigine was not included in the list of antidepressants in my editorial.

In reading Dr. Nasrallah's August 2022 editorial (“Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms,”

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thanks for your message. Lamotrigine is not FDA-approved for bipolar or unipolar depression, either as monotherapy or as an adjunctive therapy. It has never been approved for mania, either (no efficacy at all). Its only FDA-approved psychiatric indication is maintenance therapy after a patient with bipolar I disorder emerges from mania with the help of one of the antimanic drugs. Yet many clinicians may perceive lamotrigine as useful for bipolar depression because more than 20 years ago the manufacturer sponsored several small studies (not FDA trials). Two studies that showed efficacy were published, but 4 other studies that failed to show efficacy were not published. As a result, many clinicians got the false impression that lamotrigine is an effective antidepressant. I hope this explains why lamotrigine was not included in the list of antidepressants in my editorial.

In reading Dr. Nasrallah's August 2022 editorial (“Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms,”

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thanks for your message. Lamotrigine is not FDA-approved for bipolar or unipolar depression, either as monotherapy or as an adjunctive therapy. It has never been approved for mania, either (no efficacy at all). Its only FDA-approved psychiatric indication is maintenance therapy after a patient with bipolar I disorder emerges from mania with the help of one of the antimanic drugs. Yet many clinicians may perceive lamotrigine as useful for bipolar depression because more than 20 years ago the manufacturer sponsored several small studies (not FDA trials). Two studies that showed efficacy were published, but 4 other studies that failed to show efficacy were not published. As a result, many clinicians got the false impression that lamotrigine is an effective antidepressant. I hope this explains why lamotrigine was not included in the list of antidepressants in my editorial.

Patients with schizophrenia may be twice as likely to develop dementia

Results from a review and meta-analysis of almost 13 million total participants from nine countries showed that, across multiple different psychotic disorders, there was a 2.5-fold higher risk of developing dementia later in life compared with individuals who did not have a disorder. This was regardless of the age at which the patients first developed the mental illness.

Moreover, participants with a psychotic disorder tended to be younger than average when diagnosed with dementia. Two studies showed that those with psychotic disorders were more likely to be diagnosed with dementia as early as in their 60s.

“The findings add to a growing body of evidence linking psychiatric disorders with later cognitive decline and dementia,” senior investigator Jean Stafford, PhD, a research fellow at MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing, University College London, told this news organization.

Dr. Stafford noted that the results highlight the importance of being aware of and watchful for symptoms of cognitive decline in patients with psychotic disorders in mid- and late life.

“In addition, given that people with psychotic disorders are at higher risk of experiencing multiple health conditions, including dementia, managing overall physical and mental health in this group is crucial,” she said.

The findings were published online in Psychological Medicine.

Bringing the evidence together

There is increasing evidence that multiple psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses are associated with cognitive decline and dementia, with particularly strong evidence for late-life depression, Dr. Stafford said.

“However, the relationship between psychotic disorders and dementia is less well-established,” she added.

Last year, her team published a study showing a strong association between very late onset psychotic disorders, defined as first diagnosed after age 60 years, and increased risk for dementia in Swedish population register data.

“We also became aware of several other large studies on the topic published in the last few years and realized that an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis was needed to bring together the evidence, specifically focusing on longitudinal studies,” Dr. Stafford said.

The researchers searched four databases of prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies published through March 2022. Studies were required to focus on adults aged 18 years or older with a clinical diagnosis of a nonaffective psychotic disorder and a comparison group consisting of adults without a nonaffective psychotic disorder.

Of 9,496 papers, the investigators selected 11 published from 2003 to 2022 that met criteria for inclusion in their meta-analysis (12,997,101 participants), with follow-up periods ranging from 1.57 to 33 years.

The studies hailed from Denmark, Finland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Taiwan, New Zealand, and Israel.

Random-effects meta-analyses were used to pool estimates across studies. The researchers assessed the risk of bias for each study. They also included two additional studies in the review, but not the meta-analysis, that focused specifically on late-onset acute and transient psychosis and late-onset delusional disorder.

The other studies focused on late-onset schizophrenia and/or very late onset schizophrenia-like psychoses, schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, and schizophrenia in older people.

Most studies investigated the incidence of all-cause dementia, although one study focused on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.

Potential mechanisms

The narrative review showed that most studies (n = 10) were of high methodological quality, although two were rated as fair and one as poor.

Almost all studies accounted for basic sociodemographic confounders. Several also adjusted for comorbidities, alcohol/substance use disorders, medications, smoking status, and income/education level.

Pooled estimates from the meta-analyzed studies showed that only one showed no significant association between psychotic disorders and dementia, whereas 10 reported increased risk (pooled risk ratio, 2.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.67-3.80; I2, 99.7%).

Subgroup analyses showed higher risk in participants with typical and late-onset psychotic disorders (pooled RR, 2.10; 95% CI, 2.33-4.14; I2, 77.5%; P = .004) vs. those with very late onset schizophrenia-like psychoses (pooled RR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.74-4.40 I2, 98.9%; P < .001).

The effect was larger in studies with a follow-up of less than 10 years vs. those with a follow-up of 10 years or more, and it was also greater in studies conducted in non-European vs. European countries (all P < .001).

Studies with more female participants (≥ 60%) showed higher risk compared with those that had a lower percentage of female participants. Studies published during or after 2020 showed a stronger association than those published before 2020 (all P < .001).

There was also a higher risk for dementia in studies investigating broader nonaffective psychotic disorders compared with studies investigating only schizophrenia, in prospective vs. retrospective studies, and in studies with a minimum age of less than 60 years at baseline vs. a minimum age of 60 or older (all P < .001).

“Several possible mechanisms could underlie these findings, although we were not able to directly test these in our review,” Dr. Stafford said. She noted that psychotic disorders and other psychiatric diagnoses may cause dementia.

“People with psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are also at higher risk of health conditions including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which are known risk factors for dementia and could underpin these associations,” said Dr. Stafford.

It is also possible “that psychotic symptoms could be early markers of dementia for some people, rather than causes,” she added.

Neuroimaging evidence lacking

Commenting on the study, Dilip V. Jeste, MD, former senior associate dean for healthy aging and senior care and distinguished professor of psychiatry and neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego, complimented the investigators for “an excellent article on an important but difficult topic.”

Limitations “pertain not to the meta-analysis but to the original studies,” said Dr. Jeste, who was not involved with the review. Diagnosing dementia in individuals with psychotic disorders is “challenging because cognitive deficits and behavioral symptoms in psychotic disorders may be misdiagnosed as dementia in some individuals – and vice versa,” he added.

Moreover, the studies did not specify the type of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal, or mixed. Together, “they account for 90% of the dementias, and most patients with these dementias have brain abnormalities that can clearly be seen on MRI,” Dr. Jeste said.

However, patients with schizophrenia who are diagnosed with dementia “rarely show severe brain atrophy, even in specific regions commonly observed in nonpsychotic people with these dementias,” Dr. Jeste noted.

Thus, objective neuroimaging-based evidence for dementia and its subtype “is lacking in most of the published studies of persons with psychotic disorders diagnosed as having dementia,” he said.

There is a “clear need for comprehensive studies of dementia in people with psychotic disorders to understand the significance of the results,” Dr. Jeste concluded.

The review did not receive any funding. Dr. Stafford was supported by an NIHR-UCLH BRC Postdoctoral Bridging Fellowship and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Stafford was also the principal investigator in one of the studies meeting the inclusion criteria of the review. The other investigators and Dr. Jeste reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from a review and meta-analysis of almost 13 million total participants from nine countries showed that, across multiple different psychotic disorders, there was a 2.5-fold higher risk of developing dementia later in life compared with individuals who did not have a disorder. This was regardless of the age at which the patients first developed the mental illness.

Moreover, participants with a psychotic disorder tended to be younger than average when diagnosed with dementia. Two studies showed that those with psychotic disorders were more likely to be diagnosed with dementia as early as in their 60s.

“The findings add to a growing body of evidence linking psychiatric disorders with later cognitive decline and dementia,” senior investigator Jean Stafford, PhD, a research fellow at MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing, University College London, told this news organization.

Dr. Stafford noted that the results highlight the importance of being aware of and watchful for symptoms of cognitive decline in patients with psychotic disorders in mid- and late life.

“In addition, given that people with psychotic disorders are at higher risk of experiencing multiple health conditions, including dementia, managing overall physical and mental health in this group is crucial,” she said.

The findings were published online in Psychological Medicine.

Bringing the evidence together

There is increasing evidence that multiple psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses are associated with cognitive decline and dementia, with particularly strong evidence for late-life depression, Dr. Stafford said.

“However, the relationship between psychotic disorders and dementia is less well-established,” she added.

Last year, her team published a study showing a strong association between very late onset psychotic disorders, defined as first diagnosed after age 60 years, and increased risk for dementia in Swedish population register data.

“We also became aware of several other large studies on the topic published in the last few years and realized that an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis was needed to bring together the evidence, specifically focusing on longitudinal studies,” Dr. Stafford said.

The researchers searched four databases of prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies published through March 2022. Studies were required to focus on adults aged 18 years or older with a clinical diagnosis of a nonaffective psychotic disorder and a comparison group consisting of adults without a nonaffective psychotic disorder.

Of 9,496 papers, the investigators selected 11 published from 2003 to 2022 that met criteria for inclusion in their meta-analysis (12,997,101 participants), with follow-up periods ranging from 1.57 to 33 years.

The studies hailed from Denmark, Finland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Taiwan, New Zealand, and Israel.

Random-effects meta-analyses were used to pool estimates across studies. The researchers assessed the risk of bias for each study. They also included two additional studies in the review, but not the meta-analysis, that focused specifically on late-onset acute and transient psychosis and late-onset delusional disorder.

The other studies focused on late-onset schizophrenia and/or very late onset schizophrenia-like psychoses, schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, and schizophrenia in older people.

Most studies investigated the incidence of all-cause dementia, although one study focused on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.

Potential mechanisms

The narrative review showed that most studies (n = 10) were of high methodological quality, although two were rated as fair and one as poor.

Almost all studies accounted for basic sociodemographic confounders. Several also adjusted for comorbidities, alcohol/substance use disorders, medications, smoking status, and income/education level.

Pooled estimates from the meta-analyzed studies showed that only one showed no significant association between psychotic disorders and dementia, whereas 10 reported increased risk (pooled risk ratio, 2.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.67-3.80; I2, 99.7%).

Subgroup analyses showed higher risk in participants with typical and late-onset psychotic disorders (pooled RR, 2.10; 95% CI, 2.33-4.14; I2, 77.5%; P = .004) vs. those with very late onset schizophrenia-like psychoses (pooled RR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.74-4.40 I2, 98.9%; P < .001).

The effect was larger in studies with a follow-up of less than 10 years vs. those with a follow-up of 10 years or more, and it was also greater in studies conducted in non-European vs. European countries (all P < .001).

Studies with more female participants (≥ 60%) showed higher risk compared with those that had a lower percentage of female participants. Studies published during or after 2020 showed a stronger association than those published before 2020 (all P < .001).

There was also a higher risk for dementia in studies investigating broader nonaffective psychotic disorders compared with studies investigating only schizophrenia, in prospective vs. retrospective studies, and in studies with a minimum age of less than 60 years at baseline vs. a minimum age of 60 or older (all P < .001).

“Several possible mechanisms could underlie these findings, although we were not able to directly test these in our review,” Dr. Stafford said. She noted that psychotic disorders and other psychiatric diagnoses may cause dementia.

“People with psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are also at higher risk of health conditions including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which are known risk factors for dementia and could underpin these associations,” said Dr. Stafford.

It is also possible “that psychotic symptoms could be early markers of dementia for some people, rather than causes,” she added.

Neuroimaging evidence lacking

Commenting on the study, Dilip V. Jeste, MD, former senior associate dean for healthy aging and senior care and distinguished professor of psychiatry and neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego, complimented the investigators for “an excellent article on an important but difficult topic.”

Limitations “pertain not to the meta-analysis but to the original studies,” said Dr. Jeste, who was not involved with the review. Diagnosing dementia in individuals with psychotic disorders is “challenging because cognitive deficits and behavioral symptoms in psychotic disorders may be misdiagnosed as dementia in some individuals – and vice versa,” he added.

Moreover, the studies did not specify the type of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal, or mixed. Together, “they account for 90% of the dementias, and most patients with these dementias have brain abnormalities that can clearly be seen on MRI,” Dr. Jeste said.

However, patients with schizophrenia who are diagnosed with dementia “rarely show severe brain atrophy, even in specific regions commonly observed in nonpsychotic people with these dementias,” Dr. Jeste noted.

Thus, objective neuroimaging-based evidence for dementia and its subtype “is lacking in most of the published studies of persons with psychotic disorders diagnosed as having dementia,” he said.

There is a “clear need for comprehensive studies of dementia in people with psychotic disorders to understand the significance of the results,” Dr. Jeste concluded.

The review did not receive any funding. Dr. Stafford was supported by an NIHR-UCLH BRC Postdoctoral Bridging Fellowship and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Stafford was also the principal investigator in one of the studies meeting the inclusion criteria of the review. The other investigators and Dr. Jeste reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from a review and meta-analysis of almost 13 million total participants from nine countries showed that, across multiple different psychotic disorders, there was a 2.5-fold higher risk of developing dementia later in life compared with individuals who did not have a disorder. This was regardless of the age at which the patients first developed the mental illness.

Moreover, participants with a psychotic disorder tended to be younger than average when diagnosed with dementia. Two studies showed that those with psychotic disorders were more likely to be diagnosed with dementia as early as in their 60s.

“The findings add to a growing body of evidence linking psychiatric disorders with later cognitive decline and dementia,” senior investigator Jean Stafford, PhD, a research fellow at MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing, University College London, told this news organization.

Dr. Stafford noted that the results highlight the importance of being aware of and watchful for symptoms of cognitive decline in patients with psychotic disorders in mid- and late life.

“In addition, given that people with psychotic disorders are at higher risk of experiencing multiple health conditions, including dementia, managing overall physical and mental health in this group is crucial,” she said.

The findings were published online in Psychological Medicine.

Bringing the evidence together

There is increasing evidence that multiple psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses are associated with cognitive decline and dementia, with particularly strong evidence for late-life depression, Dr. Stafford said.

“However, the relationship between psychotic disorders and dementia is less well-established,” she added.

Last year, her team published a study showing a strong association between very late onset psychotic disorders, defined as first diagnosed after age 60 years, and increased risk for dementia in Swedish population register data.

“We also became aware of several other large studies on the topic published in the last few years and realized that an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis was needed to bring together the evidence, specifically focusing on longitudinal studies,” Dr. Stafford said.

The researchers searched four databases of prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies published through March 2022. Studies were required to focus on adults aged 18 years or older with a clinical diagnosis of a nonaffective psychotic disorder and a comparison group consisting of adults without a nonaffective psychotic disorder.

Of 9,496 papers, the investigators selected 11 published from 2003 to 2022 that met criteria for inclusion in their meta-analysis (12,997,101 participants), with follow-up periods ranging from 1.57 to 33 years.

The studies hailed from Denmark, Finland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Taiwan, New Zealand, and Israel.

Random-effects meta-analyses were used to pool estimates across studies. The researchers assessed the risk of bias for each study. They also included two additional studies in the review, but not the meta-analysis, that focused specifically on late-onset acute and transient psychosis and late-onset delusional disorder.

The other studies focused on late-onset schizophrenia and/or very late onset schizophrenia-like psychoses, schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, and schizophrenia in older people.

Most studies investigated the incidence of all-cause dementia, although one study focused on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.

Potential mechanisms

The narrative review showed that most studies (n = 10) were of high methodological quality, although two were rated as fair and one as poor.

Almost all studies accounted for basic sociodemographic confounders. Several also adjusted for comorbidities, alcohol/substance use disorders, medications, smoking status, and income/education level.

Pooled estimates from the meta-analyzed studies showed that only one showed no significant association between psychotic disorders and dementia, whereas 10 reported increased risk (pooled risk ratio, 2.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.67-3.80; I2, 99.7%).

Subgroup analyses showed higher risk in participants with typical and late-onset psychotic disorders (pooled RR, 2.10; 95% CI, 2.33-4.14; I2, 77.5%; P = .004) vs. those with very late onset schizophrenia-like psychoses (pooled RR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.74-4.40 I2, 98.9%; P < .001).

The effect was larger in studies with a follow-up of less than 10 years vs. those with a follow-up of 10 years or more, and it was also greater in studies conducted in non-European vs. European countries (all P < .001).

Studies with more female participants (≥ 60%) showed higher risk compared with those that had a lower percentage of female participants. Studies published during or after 2020 showed a stronger association than those published before 2020 (all P < .001).

There was also a higher risk for dementia in studies investigating broader nonaffective psychotic disorders compared with studies investigating only schizophrenia, in prospective vs. retrospective studies, and in studies with a minimum age of less than 60 years at baseline vs. a minimum age of 60 or older (all P < .001).

“Several possible mechanisms could underlie these findings, although we were not able to directly test these in our review,” Dr. Stafford said. She noted that psychotic disorders and other psychiatric diagnoses may cause dementia.

“People with psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are also at higher risk of health conditions including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which are known risk factors for dementia and could underpin these associations,” said Dr. Stafford.

It is also possible “that psychotic symptoms could be early markers of dementia for some people, rather than causes,” she added.

Neuroimaging evidence lacking

Commenting on the study, Dilip V. Jeste, MD, former senior associate dean for healthy aging and senior care and distinguished professor of psychiatry and neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego, complimented the investigators for “an excellent article on an important but difficult topic.”

Limitations “pertain not to the meta-analysis but to the original studies,” said Dr. Jeste, who was not involved with the review. Diagnosing dementia in individuals with psychotic disorders is “challenging because cognitive deficits and behavioral symptoms in psychotic disorders may be misdiagnosed as dementia in some individuals – and vice versa,” he added.

Moreover, the studies did not specify the type of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal, or mixed. Together, “they account for 90% of the dementias, and most patients with these dementias have brain abnormalities that can clearly be seen on MRI,” Dr. Jeste said.

However, patients with schizophrenia who are diagnosed with dementia “rarely show severe brain atrophy, even in specific regions commonly observed in nonpsychotic people with these dementias,” Dr. Jeste noted.

Thus, objective neuroimaging-based evidence for dementia and its subtype “is lacking in most of the published studies of persons with psychotic disorders diagnosed as having dementia,” he said.

There is a “clear need for comprehensive studies of dementia in people with psychotic disorders to understand the significance of the results,” Dr. Jeste concluded.

The review did not receive any funding. Dr. Stafford was supported by an NIHR-UCLH BRC Postdoctoral Bridging Fellowship and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Stafford was also the principal investigator in one of the studies meeting the inclusion criteria of the review. The other investigators and Dr. Jeste reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PSYCHOLOGICAL MEDICINE

Menopause an independent risk factor for schizophrenia relapse

Investigators studied a cohort of close to 62,000 people with SSDs, stratifying individuals by sex and age, and found that starting between the ages of 45 and 50 years – when the menopausal transition is underway – women were more frequently hospitalized for psychosis, compared with men and women younger than 45 years.

In addition, the protective effect of antipsychotic medication was highest in women younger than 45 years and lowest in women aged 45 years or older, even at higher doses.

“Women with schizophrenia who are older than 45 are a vulnerable group for relapse, and higher doses of antipsychotics are not the answer,” lead author Iris Sommer, MD, PhD, professor, department of neuroscience, University Medical Center of Groningen, the Netherlands, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Schizophrenia Bulletin.

Vulnerable period

There is an association between estrogen levels and disease severity throughout the life stages of women with SSDs, with lower estrogen levels associated with psychosis, for example, during low estrogenic phases of the menstrual cycle, the investigators note.

“After menopause, estrogen levels remain low, which is associated with a deterioration in the clinical course; therefore, women with SSD have sex-specific psychiatric needs that differ according to their life stage,” they add.

“Estrogens inhibit an important liver enzyme (cytochrome P-450 [CYP1A2]), which leads to higher blood levels of several antipsychotics like olanzapine and clozapine,” said Dr. Sommer. In addition, estrogens make the stomach less acidic, “leading to easier resorption of medication.”

As a clinician, Dr. Sommer said that she has “often witnessed a worsening of symptoms [of psychosis] after menopause.” As a researcher, she “knew that estrogens can have ameliorating effects on brain health, especially in schizophrenia.”

She and her colleagues were motivated to research the issue because there is a “remarkable paucity” of quantitative data on a “vulnerable period that all women with schizophrenia will experience.”

Detailed, quantitative data

The researchers sought to provide “detailed, quantitative data on life-stage dependent clinical changes occurring in women with SSD, using an intra-individual design to prevent confounding.”

They drew on data from a nationwide, register-based cohort study of all hospitalized patients with SSD between 1972 and 2014 in Finland (n = 61,889), with follow-up from Jan. 1, 1996, to Dec. 31, 2017.

People were stratified according to age (younger than 45 years and 45 years or older), with the same person contributing person-time to both age groups. The cohort was also subdivided into 5-year age groups, starting at age 20 years and ending at age 69 years.

The primary outcome measure was relapse (that is, inpatient hospitalization because of psychosis).

The researchers focused specifically on monotherapies, excluding time periods when two or more antipsychotics were used concomitantly. They also looked at antipsychotic nonuse periods.

Antipsychotic monotherapies were categorized into defined daily doses per day (DDDs/d):

- less than 0.4

- 0.4 to 0.6

- 0.6 to 0.9

- 0.9 to less than 1.1

- 1.1 to less than 1.4

- 1.4 to less than 1.6

- 1.6 or more

The researchers restricted the main analyses to the four most frequently used oral antipsychotic monotherapies: clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone.

The turning tide

The cohort consisted of more men than women (31,104 vs. 30,785, respectively), with a mean (standard deviation) age of 49.8 (16.6) years in women vs. 43.6 (14.8) in men.

Among both sexes, olanzapine was the most prescribed antipsychotic (roughly one-quarter of patients). In women, the next most common antipsychotic was risperidone, followed by quetiapine and clozapine, whereas in men, the second most common antipsychotic was clozapine, followed by risperidone and quetiapine.

When the researchers compared men and women younger than 45 years, there were “few consistent differences” in proportions hospitalized for psychosis.

Starting at age 45 years and continuing through the oldest age group (65-69 years), higher proportions of women were hospitalized for psychosis, compared with their male peers (all Ps < .00001).

Women 45 or older had significantly higher risk for relapse associated with standard dose use, compared with the other groups.

When the researchers compared men and women older and younger than 45 years, women younger than 45 years showed lower adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) at doses between of 0.6-0.9 DDDs/d, whereas for doses over 1.1 DDDs/d, women aged 45 years or older showed “remarkably higher” aHRs, compared with women younger than 45 years and men aged 45 years or older, with a difference that increased with increasing dose.

In women, the efficacy of the antipsychotics was decreased at these DDDs/d.

“We ... showed that antipsychotic monotherapy is most effective in preventing relapse in women below 45, as compared to women above that age, and also as compared to men of all ages,” the authors summarize. But after age 45 years, “the tide seems to turn for women,” compared with younger women and with men of the same age group.

One of several study limitations was the use of age as an estimation of menopausal status, they note.

Don’t just raise the dose

Commenting on the research, Mary Seeman, MD, professor emerita, department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, noted the study corroborates her group’s findings regarding the effect of menopause on antipsychotic response.

“When the efficacy of previously effective antipsychotic doses wanes at menopause, raising the dose is not the treatment of choice because it increases the risk of weight gain, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular events,” said Dr. Seeman, who was not involved with the current research.

“Changing to an antipsychotic that is less affected by estrogen loss may work better,” she continued, noting that amisulpride and aripiprazole “work well post menopause.”

Additional interventions may include changing to a depot or skin-patch antipsychotic that “obviates first-pass metabolism,” adding hormone replacement or a selective estrogen receptor modulator or including phytoestrogens (bioidenticals) in the diet.

The study yields research recommendations, including comparing the effectiveness of different antipsychotics in postmenopausal women with SSDs, recruiting pre- and postmenopausal women in trials of antipsychotic drugs, and stratifying by hormonal status when analyzing results of antipsychotic trials, Dr. Seeman said.

This work was supported by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital and the Academy of Finland. The Dutch Medical Research Association supported Dr. Sommer. Dr. Sommer declares no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Seeman declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied a cohort of close to 62,000 people with SSDs, stratifying individuals by sex and age, and found that starting between the ages of 45 and 50 years – when the menopausal transition is underway – women were more frequently hospitalized for psychosis, compared with men and women younger than 45 years.

In addition, the protective effect of antipsychotic medication was highest in women younger than 45 years and lowest in women aged 45 years or older, even at higher doses.

“Women with schizophrenia who are older than 45 are a vulnerable group for relapse, and higher doses of antipsychotics are not the answer,” lead author Iris Sommer, MD, PhD, professor, department of neuroscience, University Medical Center of Groningen, the Netherlands, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Schizophrenia Bulletin.

Vulnerable period

There is an association between estrogen levels and disease severity throughout the life stages of women with SSDs, with lower estrogen levels associated with psychosis, for example, during low estrogenic phases of the menstrual cycle, the investigators note.

“After menopause, estrogen levels remain low, which is associated with a deterioration in the clinical course; therefore, women with SSD have sex-specific psychiatric needs that differ according to their life stage,” they add.

“Estrogens inhibit an important liver enzyme (cytochrome P-450 [CYP1A2]), which leads to higher blood levels of several antipsychotics like olanzapine and clozapine,” said Dr. Sommer. In addition, estrogens make the stomach less acidic, “leading to easier resorption of medication.”

As a clinician, Dr. Sommer said that she has “often witnessed a worsening of symptoms [of psychosis] after menopause.” As a researcher, she “knew that estrogens can have ameliorating effects on brain health, especially in schizophrenia.”

She and her colleagues were motivated to research the issue because there is a “remarkable paucity” of quantitative data on a “vulnerable period that all women with schizophrenia will experience.”

Detailed, quantitative data

The researchers sought to provide “detailed, quantitative data on life-stage dependent clinical changes occurring in women with SSD, using an intra-individual design to prevent confounding.”

They drew on data from a nationwide, register-based cohort study of all hospitalized patients with SSD between 1972 and 2014 in Finland (n = 61,889), with follow-up from Jan. 1, 1996, to Dec. 31, 2017.

People were stratified according to age (younger than 45 years and 45 years or older), with the same person contributing person-time to both age groups. The cohort was also subdivided into 5-year age groups, starting at age 20 years and ending at age 69 years.

The primary outcome measure was relapse (that is, inpatient hospitalization because of psychosis).

The researchers focused specifically on monotherapies, excluding time periods when two or more antipsychotics were used concomitantly. They also looked at antipsychotic nonuse periods.

Antipsychotic monotherapies were categorized into defined daily doses per day (DDDs/d):

- less than 0.4

- 0.4 to 0.6

- 0.6 to 0.9

- 0.9 to less than 1.1

- 1.1 to less than 1.4

- 1.4 to less than 1.6

- 1.6 or more

The researchers restricted the main analyses to the four most frequently used oral antipsychotic monotherapies: clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone.

The turning tide

The cohort consisted of more men than women (31,104 vs. 30,785, respectively), with a mean (standard deviation) age of 49.8 (16.6) years in women vs. 43.6 (14.8) in men.

Among both sexes, olanzapine was the most prescribed antipsychotic (roughly one-quarter of patients). In women, the next most common antipsychotic was risperidone, followed by quetiapine and clozapine, whereas in men, the second most common antipsychotic was clozapine, followed by risperidone and quetiapine.

When the researchers compared men and women younger than 45 years, there were “few consistent differences” in proportions hospitalized for psychosis.

Starting at age 45 years and continuing through the oldest age group (65-69 years), higher proportions of women were hospitalized for psychosis, compared with their male peers (all Ps < .00001).

Women 45 or older had significantly higher risk for relapse associated with standard dose use, compared with the other groups.

When the researchers compared men and women older and younger than 45 years, women younger than 45 years showed lower adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) at doses between of 0.6-0.9 DDDs/d, whereas for doses over 1.1 DDDs/d, women aged 45 years or older showed “remarkably higher” aHRs, compared with women younger than 45 years and men aged 45 years or older, with a difference that increased with increasing dose.

In women, the efficacy of the antipsychotics was decreased at these DDDs/d.

“We ... showed that antipsychotic monotherapy is most effective in preventing relapse in women below 45, as compared to women above that age, and also as compared to men of all ages,” the authors summarize. But after age 45 years, “the tide seems to turn for women,” compared with younger women and with men of the same age group.

One of several study limitations was the use of age as an estimation of menopausal status, they note.

Don’t just raise the dose

Commenting on the research, Mary Seeman, MD, professor emerita, department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, noted the study corroborates her group’s findings regarding the effect of menopause on antipsychotic response.

“When the efficacy of previously effective antipsychotic doses wanes at menopause, raising the dose is not the treatment of choice because it increases the risk of weight gain, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular events,” said Dr. Seeman, who was not involved with the current research.

“Changing to an antipsychotic that is less affected by estrogen loss may work better,” she continued, noting that amisulpride and aripiprazole “work well post menopause.”

Additional interventions may include changing to a depot or skin-patch antipsychotic that “obviates first-pass metabolism,” adding hormone replacement or a selective estrogen receptor modulator or including phytoestrogens (bioidenticals) in the diet.

The study yields research recommendations, including comparing the effectiveness of different antipsychotics in postmenopausal women with SSDs, recruiting pre- and postmenopausal women in trials of antipsychotic drugs, and stratifying by hormonal status when analyzing results of antipsychotic trials, Dr. Seeman said.

This work was supported by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital and the Academy of Finland. The Dutch Medical Research Association supported Dr. Sommer. Dr. Sommer declares no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Seeman declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied a cohort of close to 62,000 people with SSDs, stratifying individuals by sex and age, and found that starting between the ages of 45 and 50 years – when the menopausal transition is underway – women were more frequently hospitalized for psychosis, compared with men and women younger than 45 years.

In addition, the protective effect of antipsychotic medication was highest in women younger than 45 years and lowest in women aged 45 years or older, even at higher doses.

“Women with schizophrenia who are older than 45 are a vulnerable group for relapse, and higher doses of antipsychotics are not the answer,” lead author Iris Sommer, MD, PhD, professor, department of neuroscience, University Medical Center of Groningen, the Netherlands, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Schizophrenia Bulletin.

Vulnerable period

There is an association between estrogen levels and disease severity throughout the life stages of women with SSDs, with lower estrogen levels associated with psychosis, for example, during low estrogenic phases of the menstrual cycle, the investigators note.

“After menopause, estrogen levels remain low, which is associated with a deterioration in the clinical course; therefore, women with SSD have sex-specific psychiatric needs that differ according to their life stage,” they add.

“Estrogens inhibit an important liver enzyme (cytochrome P-450 [CYP1A2]), which leads to higher blood levels of several antipsychotics like olanzapine and clozapine,” said Dr. Sommer. In addition, estrogens make the stomach less acidic, “leading to easier resorption of medication.”