User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #11 for the ObGyn

In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Continue to the answer...

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Continue to the answer...

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Continue to the answer...

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Fibroids: Growing management options for a prevalent problem

OBG Manag. 33(12). | doi 10.12788/obgm.0169

COMMENT & CONTROVERSY

HOW TO CHOOSE THE RIGHT VAGINAL MOISTURIZER OR LUBRICANT FOR YOUR PATIENT

JOHN PENNYCUFF, MD, MSPH, AND CHERYL IGLESIA, MD (JUNE 2021)

Which vaginal products to recommend

We applaud Drs. Pennycuff and Iglesia for providing education on lubricants and vaginal moisturizers in their recent article, and agree that ObGyns, urogynecologists, and primary care providers should be aware of the types of products available. However, the authors underplayed the health risks associated with the use of poor-quality lubricants and moisturizers.

Women often turn to lubricants or vaginal moisturizers because they experience vaginal dryness during intercourse, related to menopause, and from certain medications. Vaginal fluid is primarily composed of exudate from capillaries in the vaginal wall. During sexual arousal, blood flow to the vaginal wall increases, and in turn, this should increase exudate. But chronic inflammation can suppress these increases in vaginal blood flow, preventing adequate vaginal fluid production. One such cause of chronic inflammation is using hyperosmolar lubricants, as this has been shown to negatively affect the vaginal epithelium.1,2 In this way, use of hyperosmolar lubricants can actually worsen symptoms, creating a vicious circle of dryness, lubricant use, and worsening dryness.

In addition, hyperosmolar lubricants have been shown to reduce the epithelial barrier properties of the vaginal epithelium, increasing susceptibility to microbes associated with bacterial vaginosis and to true pathogens, including herpes simplex virus type 2.3 In fact, hyperosmolar lubricants are a serious enough problem that the World Health Organization has weighed in, recommending osmolality of personal lubricants be under 380 mOsm/kg to prevent damage to the vaginal epithelium.4

Appropriately acidic pH is just as critical as osmolality. Using products with a pH higher than 4.5 will reduce amounts of protective lactobacilli and other commensal vaginal bacteria, encouraging growth of opportunistic bacteria and yeast already present. This can lead to bacterial vaginosis, aerobic vaginitis, and candidiasis. Bacterial vaginosis can lead to other serious sequelae such as increased risk in acquisition of HIV infection and preterm birth in pregnancy. Unfortunately, much of the data cited in Drs. Pennycuff and Iglesia’s article were sourced from another study (by Edwards and Panay published in Climacteric in 2016), which measured product pH values with an inappropriately calibrated device; the study’s supplemental information stated that calibration was between 5 and 9, and so any measurement below 5 was invalid and subject to error. For example, the Good Clean Love lubricant is listed as having a pH of 4.7, but its pH is never higher than 4.4.

The products on the market that meet the dual criteria of appropriate pH and isotonicity to vaginal epithelial cells may be less well known to consumers. But this should not be a reason to encourage use of hyperosmolar products whose main selling point is that they are the “leading brand.” Educating women on their choices in personal lubricants should include a full discussion of product ingredients and properties, based upon the available literature to help them select a product that supports the health of their intimate tissues.

Members of the Scientific Advisory Board for the Sexual Health and Wellness Institute: Jill Krapf, MD, MEd, IF; Cathy Chung Hwa Yi, MD; Christine Enzmann, MD, PhD, NMCP; Susan Kellogg-Spadt, PhD, CRNP, IF, CSC, FCST; Betsy Greenleaf, DO, MBA; Elizabeth DuPriest, PhD

References

- Dezzutti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV-1 activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48328. doi: 10.1371/journal .pone.0048328.

- Ayehunie S, Wang YY, Landry T, et al. Hyperosmolal vaginal lubricants markedly reduce epithelial barrier properties in a threedimensional vaginal epithelium model. Toxicol Rep. 2017;5:134-140. doi: 10.1016 /j.toxrep.2017.12.011.

- Moench TR, Mumper RJ, Hoen TE, et al. Microbicide excipients can greatly increase susceptibility to genital herpes transmission in the mouse. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:331. doi: 10.1186/1471 -2334-10-331.

- Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO/UNFPA /FHI360 Advisory note. World Health Organization, 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream /handle/10665/76580/WHO_RHR_12.33_eng .pdf?sequence=1. Accessed December 27, 2021.

Drs. Pennycuff And Iglesia Respond

We thank the members of the scientific advisory board for the Sexual Health and Wellness Institute for their thoughtful and insightful comments to our article. We agree with their comments on the importance of both pH and osmolality for vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. We also agree that selection of an incorrectly formulated product may lead to worsening of vulvovaginal symptoms as well as dysbiosis and all of its sequelae as the letter writers mentioned.

In writing the review article, we attempted to address the role that pH and osmolality play in vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and make clinicians more aware of the importance of these factors in product formulation. Our goal was to help to improve patient counseling. We tried to amass as much of the available literature as we could to act as a resource for practitioners, such as the table included in the article as well as the supplemental table included online. We hoped that by writing this article we would heighten awareness among female health practitioners about vaginal health products and encourage them to consider those products that may be better suited for their patients based on pH and osmolality.

While there remains a paucity of research on vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, there is even less consumer knowledge regarding ingredients and formulations of these products. We wholeheartedly agree with the scientific advisory board that we as health providers need to help educate women on the full spectrum of products available beyond the “leading brands.” Furthermore, we advocate that there be continued research on these products as well as more manufacturer transparency regarding not only the ingredients contained within these products but also the pH and osmolality. Simple steps such as these would ensure that providers could help counsel patients to make informed decisions regarding products for their pelvic health.

Continue to: DISMANTLING RACISM IN YOUR PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL SPHERES...

DISMANTLING RACISM IN YOUR PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL SPHERES

CASSANDRA CARBERRY, MD, MS; ANNETTA MADSEN, MD; OLIVIA CARDENAS-TROWERS, MD; OLUWATENIOLA BROWN, MD; MOIURI SIDDIQUE, MD; AND BLAIR WASHINGTON, MD, MHA (AUGUST 2021)

Dissenting opinion

“Race is real but it’s not biologic.” “Race is not based on genetic or biologic inheritance.” Am I the only one with a dissenting voice of opinion when it comes to these types of statements?

Scott Peters, MD

Oak Ridge, Tennessee

The Authors Respond

Thank you for your opinion, Dr. Peters. Although it is not completely clear what your question is, it seems that it concerns the validity of the idea that race is a social construct. We will address this question with the assumption that this letter was an effort to invite discussion and increase understanding.

The National Human Genome Research Institute describes race in this way: “Race is a fluid concept used to group people according to various factors, including ancestral background and social identity. Race is also used to group people that share a set of visible characteristics, such as skin color and facial features. Though these visible traits are influenced by genes, the vast majority of genetic variation exists within racial groups and not between them.”1

The understanding that race is a social construct has been upheld by numerous medical organizations. In August 2020, a Joint Statement was published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and 22 other organizations representing our specialty. This document states: “Recognizing that race is a social construct, not biologically based, is important to understanding that racism, not race, impacts health care, health, and health outcomes.”2

This idea is also endorsed by the AMA, who in November 2020 adopted the following policies3:

- “Recognize that race is a social construct and is distinct from ethnicity, genetic ancestry, or biology

- Support ending the practice of using race as a proxy for biology or genetics in medical education, research, and clinical practice.”

There are numerous sources that further illuminate why race is a social construct. Here are a few:

- https://www.racepowerofanillusion .org/resources/

- https ://www.pewresearch.org /fact-tank/2020/02/25/the-changing -categories-the-u-s-has-used-to -measure-race/

- Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-First Century. The New Press. 2011.

- Yudell M, Roberts D, DeSalle R, et al. Science and society. Taking race out of human genetics. Science. 2016;351(6273):564-5. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4951.

References

- National Human Genome Research Institute. Race. https://www.genome.gov/genetic-glossary /Race. Accessed December 27, 2021.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Joint Statement: Collective Action Addressing Racism. https://www.acog.org /news/news-articles/2020/08/joint-statementobstetrics-and-gynecology-collective-actionaddressing-racism.

- O’Reilly KB. AMA: Racism is a threat to public health. November 16, 2020. https://www.ama -assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/ama -racism-threat-public-health. Accessed December 27, 2021.

HOW TO CHOOSE THE RIGHT VAGINAL MOISTURIZER OR LUBRICANT FOR YOUR PATIENT

JOHN PENNYCUFF, MD, MSPH, AND CHERYL IGLESIA, MD (JUNE 2021)

Which vaginal products to recommend

We applaud Drs. Pennycuff and Iglesia for providing education on lubricants and vaginal moisturizers in their recent article, and agree that ObGyns, urogynecologists, and primary care providers should be aware of the types of products available. However, the authors underplayed the health risks associated with the use of poor-quality lubricants and moisturizers.

Women often turn to lubricants or vaginal moisturizers because they experience vaginal dryness during intercourse, related to menopause, and from certain medications. Vaginal fluid is primarily composed of exudate from capillaries in the vaginal wall. During sexual arousal, blood flow to the vaginal wall increases, and in turn, this should increase exudate. But chronic inflammation can suppress these increases in vaginal blood flow, preventing adequate vaginal fluid production. One such cause of chronic inflammation is using hyperosmolar lubricants, as this has been shown to negatively affect the vaginal epithelium.1,2 In this way, use of hyperosmolar lubricants can actually worsen symptoms, creating a vicious circle of dryness, lubricant use, and worsening dryness.

In addition, hyperosmolar lubricants have been shown to reduce the epithelial barrier properties of the vaginal epithelium, increasing susceptibility to microbes associated with bacterial vaginosis and to true pathogens, including herpes simplex virus type 2.3 In fact, hyperosmolar lubricants are a serious enough problem that the World Health Organization has weighed in, recommending osmolality of personal lubricants be under 380 mOsm/kg to prevent damage to the vaginal epithelium.4

Appropriately acidic pH is just as critical as osmolality. Using products with a pH higher than 4.5 will reduce amounts of protective lactobacilli and other commensal vaginal bacteria, encouraging growth of opportunistic bacteria and yeast already present. This can lead to bacterial vaginosis, aerobic vaginitis, and candidiasis. Bacterial vaginosis can lead to other serious sequelae such as increased risk in acquisition of HIV infection and preterm birth in pregnancy. Unfortunately, much of the data cited in Drs. Pennycuff and Iglesia’s article were sourced from another study (by Edwards and Panay published in Climacteric in 2016), which measured product pH values with an inappropriately calibrated device; the study’s supplemental information stated that calibration was between 5 and 9, and so any measurement below 5 was invalid and subject to error. For example, the Good Clean Love lubricant is listed as having a pH of 4.7, but its pH is never higher than 4.4.

The products on the market that meet the dual criteria of appropriate pH and isotonicity to vaginal epithelial cells may be less well known to consumers. But this should not be a reason to encourage use of hyperosmolar products whose main selling point is that they are the “leading brand.” Educating women on their choices in personal lubricants should include a full discussion of product ingredients and properties, based upon the available literature to help them select a product that supports the health of their intimate tissues.

Members of the Scientific Advisory Board for the Sexual Health and Wellness Institute: Jill Krapf, MD, MEd, IF; Cathy Chung Hwa Yi, MD; Christine Enzmann, MD, PhD, NMCP; Susan Kellogg-Spadt, PhD, CRNP, IF, CSC, FCST; Betsy Greenleaf, DO, MBA; Elizabeth DuPriest, PhD

References

- Dezzutti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV-1 activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48328. doi: 10.1371/journal .pone.0048328.

- Ayehunie S, Wang YY, Landry T, et al. Hyperosmolal vaginal lubricants markedly reduce epithelial barrier properties in a threedimensional vaginal epithelium model. Toxicol Rep. 2017;5:134-140. doi: 10.1016 /j.toxrep.2017.12.011.

- Moench TR, Mumper RJ, Hoen TE, et al. Microbicide excipients can greatly increase susceptibility to genital herpes transmission in the mouse. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:331. doi: 10.1186/1471 -2334-10-331.

- Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO/UNFPA /FHI360 Advisory note. World Health Organization, 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream /handle/10665/76580/WHO_RHR_12.33_eng .pdf?sequence=1. Accessed December 27, 2021.

Drs. Pennycuff And Iglesia Respond

We thank the members of the scientific advisory board for the Sexual Health and Wellness Institute for their thoughtful and insightful comments to our article. We agree with their comments on the importance of both pH and osmolality for vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. We also agree that selection of an incorrectly formulated product may lead to worsening of vulvovaginal symptoms as well as dysbiosis and all of its sequelae as the letter writers mentioned.

In writing the review article, we attempted to address the role that pH and osmolality play in vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and make clinicians more aware of the importance of these factors in product formulation. Our goal was to help to improve patient counseling. We tried to amass as much of the available literature as we could to act as a resource for practitioners, such as the table included in the article as well as the supplemental table included online. We hoped that by writing this article we would heighten awareness among female health practitioners about vaginal health products and encourage them to consider those products that may be better suited for their patients based on pH and osmolality.

While there remains a paucity of research on vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, there is even less consumer knowledge regarding ingredients and formulations of these products. We wholeheartedly agree with the scientific advisory board that we as health providers need to help educate women on the full spectrum of products available beyond the “leading brands.” Furthermore, we advocate that there be continued research on these products as well as more manufacturer transparency regarding not only the ingredients contained within these products but also the pH and osmolality. Simple steps such as these would ensure that providers could help counsel patients to make informed decisions regarding products for their pelvic health.

Continue to: DISMANTLING RACISM IN YOUR PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL SPHERES...

DISMANTLING RACISM IN YOUR PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL SPHERES

CASSANDRA CARBERRY, MD, MS; ANNETTA MADSEN, MD; OLIVIA CARDENAS-TROWERS, MD; OLUWATENIOLA BROWN, MD; MOIURI SIDDIQUE, MD; AND BLAIR WASHINGTON, MD, MHA (AUGUST 2021)

Dissenting opinion

“Race is real but it’s not biologic.” “Race is not based on genetic or biologic inheritance.” Am I the only one with a dissenting voice of opinion when it comes to these types of statements?

Scott Peters, MD

Oak Ridge, Tennessee

The Authors Respond

Thank you for your opinion, Dr. Peters. Although it is not completely clear what your question is, it seems that it concerns the validity of the idea that race is a social construct. We will address this question with the assumption that this letter was an effort to invite discussion and increase understanding.

The National Human Genome Research Institute describes race in this way: “Race is a fluid concept used to group people according to various factors, including ancestral background and social identity. Race is also used to group people that share a set of visible characteristics, such as skin color and facial features. Though these visible traits are influenced by genes, the vast majority of genetic variation exists within racial groups and not between them.”1

The understanding that race is a social construct has been upheld by numerous medical organizations. In August 2020, a Joint Statement was published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and 22 other organizations representing our specialty. This document states: “Recognizing that race is a social construct, not biologically based, is important to understanding that racism, not race, impacts health care, health, and health outcomes.”2

This idea is also endorsed by the AMA, who in November 2020 adopted the following policies3:

- “Recognize that race is a social construct and is distinct from ethnicity, genetic ancestry, or biology

- Support ending the practice of using race as a proxy for biology or genetics in medical education, research, and clinical practice.”

There are numerous sources that further illuminate why race is a social construct. Here are a few:

- https://www.racepowerofanillusion .org/resources/

- https ://www.pewresearch.org /fact-tank/2020/02/25/the-changing -categories-the-u-s-has-used-to -measure-race/

- Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-First Century. The New Press. 2011.

- Yudell M, Roberts D, DeSalle R, et al. Science and society. Taking race out of human genetics. Science. 2016;351(6273):564-5. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4951.

References

- National Human Genome Research Institute. Race. https://www.genome.gov/genetic-glossary /Race. Accessed December 27, 2021.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Joint Statement: Collective Action Addressing Racism. https://www.acog.org /news/news-articles/2020/08/joint-statementobstetrics-and-gynecology-collective-actionaddressing-racism.

- O’Reilly KB. AMA: Racism is a threat to public health. November 16, 2020. https://www.ama -assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/ama -racism-threat-public-health. Accessed December 27, 2021.

HOW TO CHOOSE THE RIGHT VAGINAL MOISTURIZER OR LUBRICANT FOR YOUR PATIENT

JOHN PENNYCUFF, MD, MSPH, AND CHERYL IGLESIA, MD (JUNE 2021)

Which vaginal products to recommend

We applaud Drs. Pennycuff and Iglesia for providing education on lubricants and vaginal moisturizers in their recent article, and agree that ObGyns, urogynecologists, and primary care providers should be aware of the types of products available. However, the authors underplayed the health risks associated with the use of poor-quality lubricants and moisturizers.

Women often turn to lubricants or vaginal moisturizers because they experience vaginal dryness during intercourse, related to menopause, and from certain medications. Vaginal fluid is primarily composed of exudate from capillaries in the vaginal wall. During sexual arousal, blood flow to the vaginal wall increases, and in turn, this should increase exudate. But chronic inflammation can suppress these increases in vaginal blood flow, preventing adequate vaginal fluid production. One such cause of chronic inflammation is using hyperosmolar lubricants, as this has been shown to negatively affect the vaginal epithelium.1,2 In this way, use of hyperosmolar lubricants can actually worsen symptoms, creating a vicious circle of dryness, lubricant use, and worsening dryness.

In addition, hyperosmolar lubricants have been shown to reduce the epithelial barrier properties of the vaginal epithelium, increasing susceptibility to microbes associated with bacterial vaginosis and to true pathogens, including herpes simplex virus type 2.3 In fact, hyperosmolar lubricants are a serious enough problem that the World Health Organization has weighed in, recommending osmolality of personal lubricants be under 380 mOsm/kg to prevent damage to the vaginal epithelium.4

Appropriately acidic pH is just as critical as osmolality. Using products with a pH higher than 4.5 will reduce amounts of protective lactobacilli and other commensal vaginal bacteria, encouraging growth of opportunistic bacteria and yeast already present. This can lead to bacterial vaginosis, aerobic vaginitis, and candidiasis. Bacterial vaginosis can lead to other serious sequelae such as increased risk in acquisition of HIV infection and preterm birth in pregnancy. Unfortunately, much of the data cited in Drs. Pennycuff and Iglesia’s article were sourced from another study (by Edwards and Panay published in Climacteric in 2016), which measured product pH values with an inappropriately calibrated device; the study’s supplemental information stated that calibration was between 5 and 9, and so any measurement below 5 was invalid and subject to error. For example, the Good Clean Love lubricant is listed as having a pH of 4.7, but its pH is never higher than 4.4.

The products on the market that meet the dual criteria of appropriate pH and isotonicity to vaginal epithelial cells may be less well known to consumers. But this should not be a reason to encourage use of hyperosmolar products whose main selling point is that they are the “leading brand.” Educating women on their choices in personal lubricants should include a full discussion of product ingredients and properties, based upon the available literature to help them select a product that supports the health of their intimate tissues.

Members of the Scientific Advisory Board for the Sexual Health and Wellness Institute: Jill Krapf, MD, MEd, IF; Cathy Chung Hwa Yi, MD; Christine Enzmann, MD, PhD, NMCP; Susan Kellogg-Spadt, PhD, CRNP, IF, CSC, FCST; Betsy Greenleaf, DO, MBA; Elizabeth DuPriest, PhD

References

- Dezzutti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV-1 activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48328. doi: 10.1371/journal .pone.0048328.

- Ayehunie S, Wang YY, Landry T, et al. Hyperosmolal vaginal lubricants markedly reduce epithelial barrier properties in a threedimensional vaginal epithelium model. Toxicol Rep. 2017;5:134-140. doi: 10.1016 /j.toxrep.2017.12.011.

- Moench TR, Mumper RJ, Hoen TE, et al. Microbicide excipients can greatly increase susceptibility to genital herpes transmission in the mouse. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:331. doi: 10.1186/1471 -2334-10-331.

- Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO/UNFPA /FHI360 Advisory note. World Health Organization, 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream /handle/10665/76580/WHO_RHR_12.33_eng .pdf?sequence=1. Accessed December 27, 2021.

Drs. Pennycuff And Iglesia Respond

We thank the members of the scientific advisory board for the Sexual Health and Wellness Institute for their thoughtful and insightful comments to our article. We agree with their comments on the importance of both pH and osmolality for vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. We also agree that selection of an incorrectly formulated product may lead to worsening of vulvovaginal symptoms as well as dysbiosis and all of its sequelae as the letter writers mentioned.

In writing the review article, we attempted to address the role that pH and osmolality play in vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and make clinicians more aware of the importance of these factors in product formulation. Our goal was to help to improve patient counseling. We tried to amass as much of the available literature as we could to act as a resource for practitioners, such as the table included in the article as well as the supplemental table included online. We hoped that by writing this article we would heighten awareness among female health practitioners about vaginal health products and encourage them to consider those products that may be better suited for their patients based on pH and osmolality.

While there remains a paucity of research on vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, there is even less consumer knowledge regarding ingredients and formulations of these products. We wholeheartedly agree with the scientific advisory board that we as health providers need to help educate women on the full spectrum of products available beyond the “leading brands.” Furthermore, we advocate that there be continued research on these products as well as more manufacturer transparency regarding not only the ingredients contained within these products but also the pH and osmolality. Simple steps such as these would ensure that providers could help counsel patients to make informed decisions regarding products for their pelvic health.

Continue to: DISMANTLING RACISM IN YOUR PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL SPHERES...

DISMANTLING RACISM IN YOUR PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL SPHERES

CASSANDRA CARBERRY, MD, MS; ANNETTA MADSEN, MD; OLIVIA CARDENAS-TROWERS, MD; OLUWATENIOLA BROWN, MD; MOIURI SIDDIQUE, MD; AND BLAIR WASHINGTON, MD, MHA (AUGUST 2021)

Dissenting opinion

“Race is real but it’s not biologic.” “Race is not based on genetic or biologic inheritance.” Am I the only one with a dissenting voice of opinion when it comes to these types of statements?

Scott Peters, MD

Oak Ridge, Tennessee

The Authors Respond

Thank you for your opinion, Dr. Peters. Although it is not completely clear what your question is, it seems that it concerns the validity of the idea that race is a social construct. We will address this question with the assumption that this letter was an effort to invite discussion and increase understanding.

The National Human Genome Research Institute describes race in this way: “Race is a fluid concept used to group people according to various factors, including ancestral background and social identity. Race is also used to group people that share a set of visible characteristics, such as skin color and facial features. Though these visible traits are influenced by genes, the vast majority of genetic variation exists within racial groups and not between them.”1

The understanding that race is a social construct has been upheld by numerous medical organizations. In August 2020, a Joint Statement was published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and 22 other organizations representing our specialty. This document states: “Recognizing that race is a social construct, not biologically based, is important to understanding that racism, not race, impacts health care, health, and health outcomes.”2

This idea is also endorsed by the AMA, who in November 2020 adopted the following policies3:

- “Recognize that race is a social construct and is distinct from ethnicity, genetic ancestry, or biology

- Support ending the practice of using race as a proxy for biology or genetics in medical education, research, and clinical practice.”

There are numerous sources that further illuminate why race is a social construct. Here are a few:

- https://www.racepowerofanillusion .org/resources/

- https ://www.pewresearch.org /fact-tank/2020/02/25/the-changing -categories-the-u-s-has-used-to -measure-race/

- Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-First Century. The New Press. 2011.

- Yudell M, Roberts D, DeSalle R, et al. Science and society. Taking race out of human genetics. Science. 2016;351(6273):564-5. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4951.

References

- National Human Genome Research Institute. Race. https://www.genome.gov/genetic-glossary /Race. Accessed December 27, 2021.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Joint Statement: Collective Action Addressing Racism. https://www.acog.org /news/news-articles/2020/08/joint-statementobstetrics-and-gynecology-collective-actionaddressing-racism.

- O’Reilly KB. AMA: Racism is a threat to public health. November 16, 2020. https://www.ama -assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/ama -racism-threat-public-health. Accessed December 27, 2021.

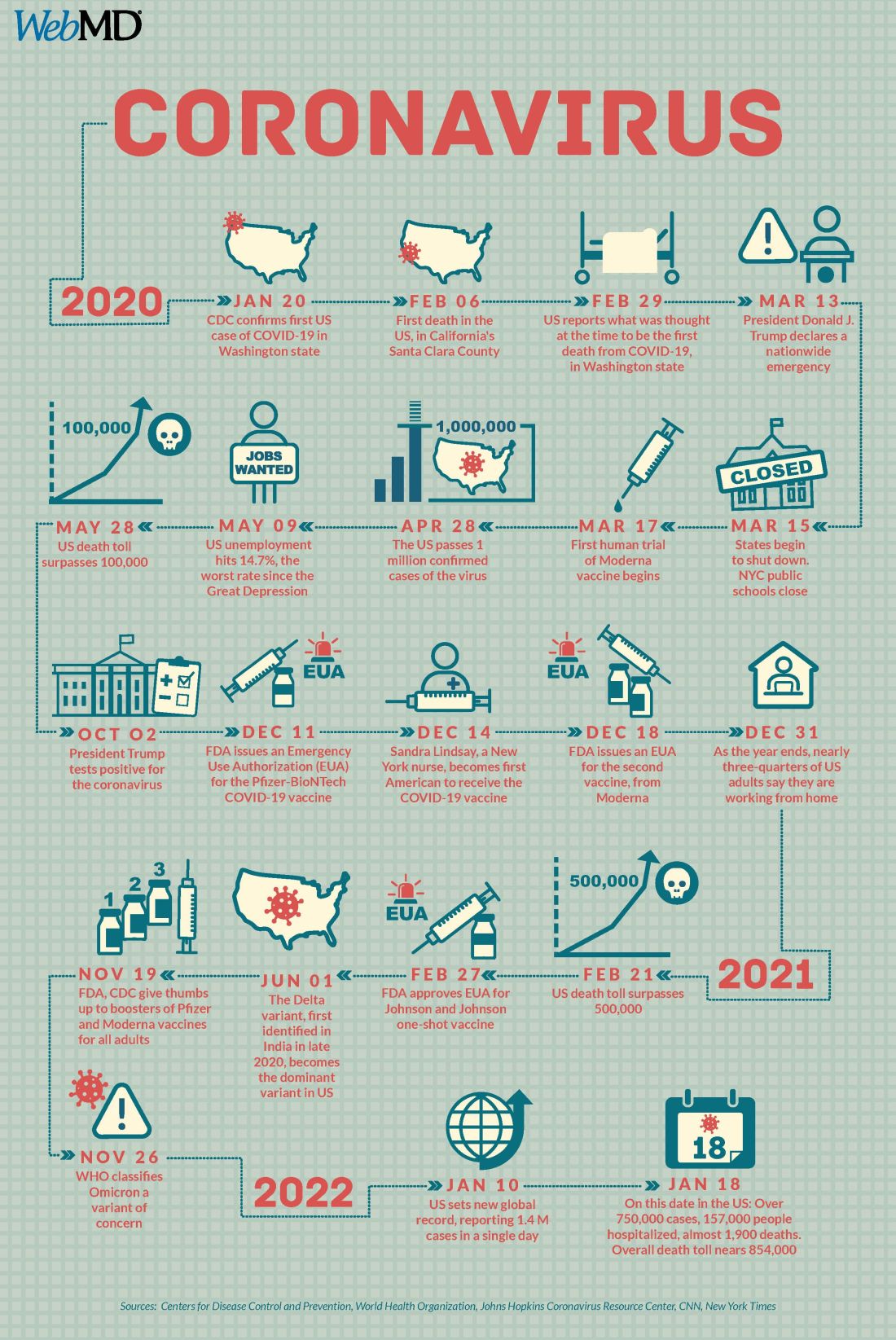

Five things you should know about ‘free’ at-home COVID tests

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Two studies detail the dangers of COVID in pregnancy

Two new studies show how COVID-19 threatens the health of pregnant people and their newborn infants.

A study conducted in Scotland showed that unvaccinated pregnant people who got COVID were much more likely to have a stillborn infant or one that dies in the first 28 days. The study also found that pregnant women infected with COVID died or needed hospitalization at a much higher rate than vaccinated women who got pregnant.

The University of Edinburgh and Public Health Scotland studied national data in 88,000 pregnancies between Dec. 2020 and Oct. 2021, according to the study published in Nature Medicine.

Overall, 77.4% of infections, 90.9% of COVID-related hospitalizations, and 98% of critical care cases occurred in the unvaccinated people, as did all newborn deaths.

The study said 2,364 babies were born to women infected with COVID, with 2,353 live births. Eleven babies were stillborn and eight live-born babies died within 28 days. Of the live births, 241 were premature.

The problems were more likely if the infection occurred 28 days or less before the delivery date, the researchers said.

The authors said the low vaccination rate among pregnant people was a problem. Only 32% of people giving birth in Oct. 2021 were fully vaccinated, while 77% of the Scottish female population aged 18-44 was fully vaccinated.

“Vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy thus requires addressing, especially in light of new recommendations for booster vaccination administration 3 months after the initial vaccination course to help protect against new variants such as Omicron,” the authors wrote. “Addressing low vaccine uptake rates in pregnant women is imperative to protect the health of women and babies in the ongoing pandemic.”

Vaccinated women who were pregnant had complication rates that were about the same for all pregnant women, the study shows.

The second study, published in The Lancet, found that women who got COVID while pregnant in five Western U.S. states were more likely to have premature births, low birth weights, and stillbirths, even when the COVID cases are mild.

The Institute for Systems Biology researchers in Seattle studied data for women who gave birth in Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, or Washington from March 5, 2020, to July 4, 2021. About 18,000 of them were tested for COVID, with 882 testing positive. Of the positive tests, 85 came in the first trimester, 226 in the second trimester, and 571 in the third semester. None of the pregnant women had been vaccinated at the time they were infected.

Most of the birth problems occurred with first and second trimester infections, the study noted, and problems occurred even if the pregnant person didn’t have respiratory complications, a major COVID symptom.

“Pregnant people are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection, even when maternal COVID-19 is less severe, and they may benefit from increased monitoring following infection,” Jennifer Hadlock, MD, an author of the paper, said in a news release.

The study also pointed out continuing inequities in health care, with most of the positive cases occurring among young, non-White people with Medicaid and high body mass index.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two new studies show how COVID-19 threatens the health of pregnant people and their newborn infants.

A study conducted in Scotland showed that unvaccinated pregnant people who got COVID were much more likely to have a stillborn infant or one that dies in the first 28 days. The study also found that pregnant women infected with COVID died or needed hospitalization at a much higher rate than vaccinated women who got pregnant.

The University of Edinburgh and Public Health Scotland studied national data in 88,000 pregnancies between Dec. 2020 and Oct. 2021, according to the study published in Nature Medicine.

Overall, 77.4% of infections, 90.9% of COVID-related hospitalizations, and 98% of critical care cases occurred in the unvaccinated people, as did all newborn deaths.

The study said 2,364 babies were born to women infected with COVID, with 2,353 live births. Eleven babies were stillborn and eight live-born babies died within 28 days. Of the live births, 241 were premature.

The problems were more likely if the infection occurred 28 days or less before the delivery date, the researchers said.

The authors said the low vaccination rate among pregnant people was a problem. Only 32% of people giving birth in Oct. 2021 were fully vaccinated, while 77% of the Scottish female population aged 18-44 was fully vaccinated.

“Vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy thus requires addressing, especially in light of new recommendations for booster vaccination administration 3 months after the initial vaccination course to help protect against new variants such as Omicron,” the authors wrote. “Addressing low vaccine uptake rates in pregnant women is imperative to protect the health of women and babies in the ongoing pandemic.”

Vaccinated women who were pregnant had complication rates that were about the same for all pregnant women, the study shows.

The second study, published in The Lancet, found that women who got COVID while pregnant in five Western U.S. states were more likely to have premature births, low birth weights, and stillbirths, even when the COVID cases are mild.

The Institute for Systems Biology researchers in Seattle studied data for women who gave birth in Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, or Washington from March 5, 2020, to July 4, 2021. About 18,000 of them were tested for COVID, with 882 testing positive. Of the positive tests, 85 came in the first trimester, 226 in the second trimester, and 571 in the third semester. None of the pregnant women had been vaccinated at the time they were infected.

Most of the birth problems occurred with first and second trimester infections, the study noted, and problems occurred even if the pregnant person didn’t have respiratory complications, a major COVID symptom.

“Pregnant people are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection, even when maternal COVID-19 is less severe, and they may benefit from increased monitoring following infection,” Jennifer Hadlock, MD, an author of the paper, said in a news release.

The study also pointed out continuing inequities in health care, with most of the positive cases occurring among young, non-White people with Medicaid and high body mass index.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two new studies show how COVID-19 threatens the health of pregnant people and their newborn infants.

A study conducted in Scotland showed that unvaccinated pregnant people who got COVID were much more likely to have a stillborn infant or one that dies in the first 28 days. The study also found that pregnant women infected with COVID died or needed hospitalization at a much higher rate than vaccinated women who got pregnant.

The University of Edinburgh and Public Health Scotland studied national data in 88,000 pregnancies between Dec. 2020 and Oct. 2021, according to the study published in Nature Medicine.

Overall, 77.4% of infections, 90.9% of COVID-related hospitalizations, and 98% of critical care cases occurred in the unvaccinated people, as did all newborn deaths.

The study said 2,364 babies were born to women infected with COVID, with 2,353 live births. Eleven babies were stillborn and eight live-born babies died within 28 days. Of the live births, 241 were premature.

The problems were more likely if the infection occurred 28 days or less before the delivery date, the researchers said.

The authors said the low vaccination rate among pregnant people was a problem. Only 32% of people giving birth in Oct. 2021 were fully vaccinated, while 77% of the Scottish female population aged 18-44 was fully vaccinated.

“Vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy thus requires addressing, especially in light of new recommendations for booster vaccination administration 3 months after the initial vaccination course to help protect against new variants such as Omicron,” the authors wrote. “Addressing low vaccine uptake rates in pregnant women is imperative to protect the health of women and babies in the ongoing pandemic.”

Vaccinated women who were pregnant had complication rates that were about the same for all pregnant women, the study shows.

The second study, published in The Lancet, found that women who got COVID while pregnant in five Western U.S. states were more likely to have premature births, low birth weights, and stillbirths, even when the COVID cases are mild.

The Institute for Systems Biology researchers in Seattle studied data for women who gave birth in Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, or Washington from March 5, 2020, to July 4, 2021. About 18,000 of them were tested for COVID, with 882 testing positive. Of the positive tests, 85 came in the first trimester, 226 in the second trimester, and 571 in the third semester. None of the pregnant women had been vaccinated at the time they were infected.

Most of the birth problems occurred with first and second trimester infections, the study noted, and problems occurred even if the pregnant person didn’t have respiratory complications, a major COVID symptom.

“Pregnant people are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection, even when maternal COVID-19 is less severe, and they may benefit from increased monitoring following infection,” Jennifer Hadlock, MD, an author of the paper, said in a news release.

The study also pointed out continuing inequities in health care, with most of the positive cases occurring among young, non-White people with Medicaid and high body mass index.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Breastfeeding linked to lower CVD risk in later life

In a meta-analysis of more than 1 million mothers, those who breastfed their children had an 11% to 17% lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), coronary heart disease (CHD), or stroke, and of dying from CVD, in later life than mothers who did not.

On average, the women had two children and had breastfed for 15.9 months in total. Longer breastfeeding was associated with greater CV health benefit.

This meta-analysis of eight studies from different countries was published online Jan. 11 in an issue of the Journal of the American Heart Association devoted to the impact of pregnancy on CV health in the mother and child.

Breastfeeding is known to be associated with a lower risk for death from infectious disease and with fewer respiratory infections in babies, the researchers write, but what is less well known is that it is also associated with a reduced risk for breast and ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes in mothers.

The current study showed a clear association between breastfeeding and reduced risk for CVD in later life, lead author Lena Tschiderer, Dipl.-Ing., PhD, and senior author Peter Willeit, MD, MPhil, PhD, summarized in a joint email to this news organization.

Specifically, mothers who had breastfed their children at any time had an 11% lower risk for CVD, a 14% lower risk for CHD, a 12% lower risk for stroke, and a 17% lower risk of dying from CVD in later life, compared with other mothers.

On the basis of existing evidence, the researchers write, the World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding until a baby is 6 months old, followed by breastfeeding plus complementary feeding until the baby is 2 years or older.

“We believe that [breastfeeding] benefits for the mother are communicated poorly,” said Dr. Tschiderer and Dr. Willeit, from the University of Innsbruck, Austria.

“Positive effects of breastfeeding on mothers need to be communicated effectively, awareness for breastfeeding recommendations needs to be raised, and interventions to promote and facilitate breastfeeding need to be implemented and reinforced,” the researchers conclude.

‘Should not be ignored’

Two cardiologists invited to comment, who were not involved with the research, noted that this study provides insight into an important topic.

“This is yet another body of evidence [and the largest population to date] to show that breastfeeding is protective for women and may show important beneficial effects in terms of CV risk,” Roxana Mehran, MD, said in an email.

“The risk reductions were 11% for CVD events and 14% for CHD events; these are impressive numbers,” said Dr. Mehran, from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“The caveat,” she said, “is that these are data from several trials, but nonetheless, this is a very important observation that should not be ignored.”

The study did not address the definitive amount of time of breastfeeding and its correlation to the improvement of CVD risk, but it did show that for the lifetime duration, the longer the better.

“The beneficial effects,” she noted, “can be linked to hormones during breastfeeding, as well as weight loss associated with breastfeeding, and resetting the maternal metabolism, as the authors suggest.”

Clinicians and employers “must provide ways to educate women about breastfeeding and make it easy for women who are in the workplace to pump, and to provide them with resources” where possible, Dr. Mehran said.

Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, MPH, noted that over the past several years, there has been intense interest in the possible health benefits of breastfeeding for both mother and child.

There is biologic plausibility for some of the possible maternal benefits because the favorable CV effects of both prolactin and oxytocin are only now being better understood, said Dr. O’Donoghue, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“The current meta-analysis provides a large dataset that helps support the concept that breastfeeding may offer some cardiovascular benefit for the mother,” she agreed.

“However, ultimately more research will be necessary since this method of combining data across trials relies upon the robustness of the statistical method in each study,” Dr. O’Donoghue said. “I applaud the authors for shining a spotlight on this important topic.”

Although the benefits of breastfeeding appear to continue over time, “it is incredibly difficult for women to continue breastfeeding once they return to work,” she added. “Women in some countries outside the U.S. have an advantage due to longer durations of maternity leave.

“If we want to encourage breastfeeding,” Dr. O’Donoghue stressed, “we need to make sure that we put the right supports in place. Women need protected places to breastfeed in the workplace and places to store their milk. Most importantly, women need to be allowed dedicated time to make it happen.”

First large study of CVD in mothers

Emerging individual studies suggest that mothers who breastfeed may have a lower risk for CVD in later life, but studies have been inconsistent, and it is not clear if longer breastfeeding would strengthen this benefit, the authors note.

To examine this, they pooled data from the following eight studies (with study acronym, country, and baseline enrolment dates in brackets): 45&Up (Australia, 2006-2009), China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB, China, 2004-2008), European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC, multinational, 1992-2000), Gallagher et al. (China, 1989-1991), Nord-Trøndelag Health Survey 2 (HUNT2, Norway, 1995-1997), Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study (JPHC, Japan, 1990-1994), Nurses’ Health Study (NHS, U.S., 1986), and the Woman’s Health Initiative (WHI, U.S., 1993-1998).

On average, the women were 51.3 years old (range, 40-65 years) when they enrolled in the study, and they were followed for a median of 10.3 years (range, 7.9-20.9 years, in the individual studies).

On average, they had their first child at age 25 and had two to three children (mean, 2.3); 82% had breastfed at some point (ranging from 58% of women in the two U.S. studies to 97% in CKB and HUNT2).

The women had breastfed for a mean of 7.4 to 18.9 months during their lifetimes (except women in the CKB study, who had breastfed for a median of 24 months).

Among the 1,192,700 women, there were 54,226 incident CVD events, 26,913 incident CHD events, 30,843 incident strokes, and 10,766 deaths from CVD during follow-up.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the fact that there could have been publication bias, since fewer than 10 studies were available for pooling. There was significant between-study heterogeneity for CVD, CHD, and stroke outcomes.

Participant-level data were also lacking, and breastfeeding was self-reported. There may have been unaccounted residual confounding, and the benefits of lifetime breastfeeding that is longer than 2 years are not clear, because few women in this population breastfed that long.

The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund. The researchers and Dr. Mehran and Dr. O’Donoghue have no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a meta-analysis of more than 1 million mothers, those who breastfed their children had an 11% to 17% lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), coronary heart disease (CHD), or stroke, and of dying from CVD, in later life than mothers who did not.

On average, the women had two children and had breastfed for 15.9 months in total. Longer breastfeeding was associated with greater CV health benefit.

This meta-analysis of eight studies from different countries was published online Jan. 11 in an issue of the Journal of the American Heart Association devoted to the impact of pregnancy on CV health in the mother and child.

Breastfeeding is known to be associated with a lower risk for death from infectious disease and with fewer respiratory infections in babies, the researchers write, but what is less well known is that it is also associated with a reduced risk for breast and ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes in mothers.

The current study showed a clear association between breastfeeding and reduced risk for CVD in later life, lead author Lena Tschiderer, Dipl.-Ing., PhD, and senior author Peter Willeit, MD, MPhil, PhD, summarized in a joint email to this news organization.

Specifically, mothers who had breastfed their children at any time had an 11% lower risk for CVD, a 14% lower risk for CHD, a 12% lower risk for stroke, and a 17% lower risk of dying from CVD in later life, compared with other mothers.

On the basis of existing evidence, the researchers write, the World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding until a baby is 6 months old, followed by breastfeeding plus complementary feeding until the baby is 2 years or older.

“We believe that [breastfeeding] benefits for the mother are communicated poorly,” said Dr. Tschiderer and Dr. Willeit, from the University of Innsbruck, Austria.

“Positive effects of breastfeeding on mothers need to be communicated effectively, awareness for breastfeeding recommendations needs to be raised, and interventions to promote and facilitate breastfeeding need to be implemented and reinforced,” the researchers conclude.

‘Should not be ignored’

Two cardiologists invited to comment, who were not involved with the research, noted that this study provides insight into an important topic.

“This is yet another body of evidence [and the largest population to date] to show that breastfeeding is protective for women and may show important beneficial effects in terms of CV risk,” Roxana Mehran, MD, said in an email.

“The risk reductions were 11% for CVD events and 14% for CHD events; these are impressive numbers,” said Dr. Mehran, from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“The caveat,” she said, “is that these are data from several trials, but nonetheless, this is a very important observation that should not be ignored.”

The study did not address the definitive amount of time of breastfeeding and its correlation to the improvement of CVD risk, but it did show that for the lifetime duration, the longer the better.

“The beneficial effects,” she noted, “can be linked to hormones during breastfeeding, as well as weight loss associated with breastfeeding, and resetting the maternal metabolism, as the authors suggest.”

Clinicians and employers “must provide ways to educate women about breastfeeding and make it easy for women who are in the workplace to pump, and to provide them with resources” where possible, Dr. Mehran said.

Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, MPH, noted that over the past several years, there has been intense interest in the possible health benefits of breastfeeding for both mother and child.

There is biologic plausibility for some of the possible maternal benefits because the favorable CV effects of both prolactin and oxytocin are only now being better understood, said Dr. O’Donoghue, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“The current meta-analysis provides a large dataset that helps support the concept that breastfeeding may offer some cardiovascular benefit for the mother,” she agreed.

“However, ultimately more research will be necessary since this method of combining data across trials relies upon the robustness of the statistical method in each study,” Dr. O’Donoghue said. “I applaud the authors for shining a spotlight on this important topic.”

Although the benefits of breastfeeding appear to continue over time, “it is incredibly difficult for women to continue breastfeeding once they return to work,” she added. “Women in some countries outside the U.S. have an advantage due to longer durations of maternity leave.

“If we want to encourage breastfeeding,” Dr. O’Donoghue stressed, “we need to make sure that we put the right supports in place. Women need protected places to breastfeed in the workplace and places to store their milk. Most importantly, women need to be allowed dedicated time to make it happen.”

First large study of CVD in mothers

Emerging individual studies suggest that mothers who breastfeed may have a lower risk for CVD in later life, but studies have been inconsistent, and it is not clear if longer breastfeeding would strengthen this benefit, the authors note.

To examine this, they pooled data from the following eight studies (with study acronym, country, and baseline enrolment dates in brackets): 45&Up (Australia, 2006-2009), China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB, China, 2004-2008), European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC, multinational, 1992-2000), Gallagher et al. (China, 1989-1991), Nord-Trøndelag Health Survey 2 (HUNT2, Norway, 1995-1997), Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study (JPHC, Japan, 1990-1994), Nurses’ Health Study (NHS, U.S., 1986), and the Woman’s Health Initiative (WHI, U.S., 1993-1998).

On average, the women were 51.3 years old (range, 40-65 years) when they enrolled in the study, and they were followed for a median of 10.3 years (range, 7.9-20.9 years, in the individual studies).

On average, they had their first child at age 25 and had two to three children (mean, 2.3); 82% had breastfed at some point (ranging from 58% of women in the two U.S. studies to 97% in CKB and HUNT2).

The women had breastfed for a mean of 7.4 to 18.9 months during their lifetimes (except women in the CKB study, who had breastfed for a median of 24 months).

Among the 1,192,700 women, there were 54,226 incident CVD events, 26,913 incident CHD events, 30,843 incident strokes, and 10,766 deaths from CVD during follow-up.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the fact that there could have been publication bias, since fewer than 10 studies were available for pooling. There was significant between-study heterogeneity for CVD, CHD, and stroke outcomes.

Participant-level data were also lacking, and breastfeeding was self-reported. There may have been unaccounted residual confounding, and the benefits of lifetime breastfeeding that is longer than 2 years are not clear, because few women in this population breastfed that long.

The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund. The researchers and Dr. Mehran and Dr. O’Donoghue have no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a meta-analysis of more than 1 million mothers, those who breastfed their children had an 11% to 17% lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD), coronary heart disease (CHD), or stroke, and of dying from CVD, in later life than mothers who did not.

On average, the women had two children and had breastfed for 15.9 months in total. Longer breastfeeding was associated with greater CV health benefit.

This meta-analysis of eight studies from different countries was published online Jan. 11 in an issue of the Journal of the American Heart Association devoted to the impact of pregnancy on CV health in the mother and child.

Breastfeeding is known to be associated with a lower risk for death from infectious disease and with fewer respiratory infections in babies, the researchers write, but what is less well known is that it is also associated with a reduced risk for breast and ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes in mothers.

The current study showed a clear association between breastfeeding and reduced risk for CVD in later life, lead author Lena Tschiderer, Dipl.-Ing., PhD, and senior author Peter Willeit, MD, MPhil, PhD, summarized in a joint email to this news organization.

Specifically, mothers who had breastfed their children at any time had an 11% lower risk for CVD, a 14% lower risk for CHD, a 12% lower risk for stroke, and a 17% lower risk of dying from CVD in later life, compared with other mothers.

On the basis of existing evidence, the researchers write, the World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding until a baby is 6 months old, followed by breastfeeding plus complementary feeding until the baby is 2 years or older.

“We believe that [breastfeeding] benefits for the mother are communicated poorly,” said Dr. Tschiderer and Dr. Willeit, from the University of Innsbruck, Austria.

“Positive effects of breastfeeding on mothers need to be communicated effectively, awareness for breastfeeding recommendations needs to be raised, and interventions to promote and facilitate breastfeeding need to be implemented and reinforced,” the researchers conclude.

‘Should not be ignored’

Two cardiologists invited to comment, who were not involved with the research, noted that this study provides insight into an important topic.

“This is yet another body of evidence [and the largest population to date] to show that breastfeeding is protective for women and may show important beneficial effects in terms of CV risk,” Roxana Mehran, MD, said in an email.

“The risk reductions were 11% for CVD events and 14% for CHD events; these are impressive numbers,” said Dr. Mehran, from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“The caveat,” she said, “is that these are data from several trials, but nonetheless, this is a very important observation that should not be ignored.”

The study did not address the definitive amount of time of breastfeeding and its correlation to the improvement of CVD risk, but it did show that for the lifetime duration, the longer the better.

“The beneficial effects,” she noted, “can be linked to hormones during breastfeeding, as well as weight loss associated with breastfeeding, and resetting the maternal metabolism, as the authors suggest.”