User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Prenatal diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders: Going beyond what’s currently indicated

Key clinical point: Performing prenatal exome sequencing (ES) not solely for the indication of fetal malformations but also for specific prenatal findings, such as fetal growth restriction and polyhydramnios, could avoid missing the diagnosis of postnatal neurocognitive disorders.

Main finding: Sonographic fetal structural findings of 52.5% of patients with postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive disorders did not hint at considering prenatal ES. Fetal structural abnormalities and other sonographic anomalies (fetal growth restriction, polyhydramnios, etc.) were shown by 23.75% of patients.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study that analyzed the prenatal sonographic data of 122 patients with postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive disorder using ES.

Disclosures: The authors received no financial support for conducting the study. AR Shuldiner disclosed being a full-time employee of and receiving salary and stock options from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. C Gonzaga-Jauregui was a full-time employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at the time of the study.

Source: Sukenik-Halevy R et al. Prenat Diagn. 2022 (Jan 14). Doi: 10.1002/pd.6095.

Key clinical point: Performing prenatal exome sequencing (ES) not solely for the indication of fetal malformations but also for specific prenatal findings, such as fetal growth restriction and polyhydramnios, could avoid missing the diagnosis of postnatal neurocognitive disorders.

Main finding: Sonographic fetal structural findings of 52.5% of patients with postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive disorders did not hint at considering prenatal ES. Fetal structural abnormalities and other sonographic anomalies (fetal growth restriction, polyhydramnios, etc.) were shown by 23.75% of patients.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study that analyzed the prenatal sonographic data of 122 patients with postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive disorder using ES.

Disclosures: The authors received no financial support for conducting the study. AR Shuldiner disclosed being a full-time employee of and receiving salary and stock options from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. C Gonzaga-Jauregui was a full-time employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at the time of the study.

Source: Sukenik-Halevy R et al. Prenat Diagn. 2022 (Jan 14). Doi: 10.1002/pd.6095.

Key clinical point: Performing prenatal exome sequencing (ES) not solely for the indication of fetal malformations but also for specific prenatal findings, such as fetal growth restriction and polyhydramnios, could avoid missing the diagnosis of postnatal neurocognitive disorders.

Main finding: Sonographic fetal structural findings of 52.5% of patients with postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive disorders did not hint at considering prenatal ES. Fetal structural abnormalities and other sonographic anomalies (fetal growth restriction, polyhydramnios, etc.) were shown by 23.75% of patients.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study that analyzed the prenatal sonographic data of 122 patients with postnatally diagnosed neurocognitive disorder using ES.

Disclosures: The authors received no financial support for conducting the study. AR Shuldiner disclosed being a full-time employee of and receiving salary and stock options from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. C Gonzaga-Jauregui was a full-time employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at the time of the study.

Source: Sukenik-Halevy R et al. Prenat Diagn. 2022 (Jan 14). Doi: 10.1002/pd.6095.

Fetuses with cerebral blood flow redistribution are susceptible to adverse perinatal outcomes

Key clinical point: Fetal cerebral blood flow redistribution assessed by antenatal Doppler scanning is a strong and independent indicator of a composite adverse perinatal outcome (CAPO) and stillbirth in low-resource settings.

Main finding: Middle cerebral artery pulsatility index (PI) <5th percentile (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.08; P = .013), cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) <5th percentile (aOR 2.22; P = .02), and uterine artery PI >95th percentile (aOR 2.36; P = .041) showed a significant association with CAPO. CPR <5th percentile was significantly associated with stillbirth (aOR 4.82; P = .038).

Study details: Findings are from a single-center prospective cohort study including 995 singleton pregnant women who enrolled in antenatal care after <24 weeks of pregnancy and showed no obvious fetal abnormalities on an antenatal ultrasound scan.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Grand Challenges Canada and University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands. No conflict of interests was reported.

Source: Ali S et al. BJOG. 2022 (Feb 4). Doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17115.

Key clinical point: Fetal cerebral blood flow redistribution assessed by antenatal Doppler scanning is a strong and independent indicator of a composite adverse perinatal outcome (CAPO) and stillbirth in low-resource settings.

Main finding: Middle cerebral artery pulsatility index (PI) <5th percentile (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.08; P = .013), cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) <5th percentile (aOR 2.22; P = .02), and uterine artery PI >95th percentile (aOR 2.36; P = .041) showed a significant association with CAPO. CPR <5th percentile was significantly associated with stillbirth (aOR 4.82; P = .038).

Study details: Findings are from a single-center prospective cohort study including 995 singleton pregnant women who enrolled in antenatal care after <24 weeks of pregnancy and showed no obvious fetal abnormalities on an antenatal ultrasound scan.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Grand Challenges Canada and University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands. No conflict of interests was reported.

Source: Ali S et al. BJOG. 2022 (Feb 4). Doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17115.

Key clinical point: Fetal cerebral blood flow redistribution assessed by antenatal Doppler scanning is a strong and independent indicator of a composite adverse perinatal outcome (CAPO) and stillbirth in low-resource settings.

Main finding: Middle cerebral artery pulsatility index (PI) <5th percentile (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.08; P = .013), cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) <5th percentile (aOR 2.22; P = .02), and uterine artery PI >95th percentile (aOR 2.36; P = .041) showed a significant association with CAPO. CPR <5th percentile was significantly associated with stillbirth (aOR 4.82; P = .038).

Study details: Findings are from a single-center prospective cohort study including 995 singleton pregnant women who enrolled in antenatal care after <24 weeks of pregnancy and showed no obvious fetal abnormalities on an antenatal ultrasound scan.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Grand Challenges Canada and University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands. No conflict of interests was reported.

Source: Ali S et al. BJOG. 2022 (Feb 4). Doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17115.

cfDNA screening for the common trisomies performs well in low-risk pregnancies

Key clinical point: In women at low risk for aneuploidy, single-nucleotide polymorphism-based cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening for trisomies 21, 18, and 13 (T21, T18, T13, respectively) demonstrates similar high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) as those in high-risk women.

Main finding: In low-risk vs. high-risk women, T21 was detected with similar sensitivity (100% vs. 98.8%; P = 1.0), specificity (99.98% vs. 99.96%; P = .61), and a high PPV (85.71% vs. 97.53%; P = .06), with analogous results for T18 and T13.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, prospective, observational SMART study including 17,851 pregnant women undergoing cfDNA screening for aneuploidy and 22q11.2DS, along with DNA analysis of the fetus or newborn. Of these, 13,043 pregnancies were at low risk for aneuploidy, with the rest being high risk.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Natera, Inc, CA, USA. Some of the authors, including the lead author, received institutional research support from Natera. M Egbert, Z Demko, M Rabinowitz, and K Martin serve as an employee/consultant of Natera and own stocks/options. J Hyett has participated in expert consultancies for and B Jacobson reports research clinical diagnostic trials with Natera, among others.

Source: Dar P et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.019.

Key clinical point: In women at low risk for aneuploidy, single-nucleotide polymorphism-based cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening for trisomies 21, 18, and 13 (T21, T18, T13, respectively) demonstrates similar high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) as those in high-risk women.

Main finding: In low-risk vs. high-risk women, T21 was detected with similar sensitivity (100% vs. 98.8%; P = 1.0), specificity (99.98% vs. 99.96%; P = .61), and a high PPV (85.71% vs. 97.53%; P = .06), with analogous results for T18 and T13.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, prospective, observational SMART study including 17,851 pregnant women undergoing cfDNA screening for aneuploidy and 22q11.2DS, along with DNA analysis of the fetus or newborn. Of these, 13,043 pregnancies were at low risk for aneuploidy, with the rest being high risk.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Natera, Inc, CA, USA. Some of the authors, including the lead author, received institutional research support from Natera. M Egbert, Z Demko, M Rabinowitz, and K Martin serve as an employee/consultant of Natera and own stocks/options. J Hyett has participated in expert consultancies for and B Jacobson reports research clinical diagnostic trials with Natera, among others.

Source: Dar P et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.019.

Key clinical point: In women at low risk for aneuploidy, single-nucleotide polymorphism-based cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening for trisomies 21, 18, and 13 (T21, T18, T13, respectively) demonstrates similar high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) as those in high-risk women.

Main finding: In low-risk vs. high-risk women, T21 was detected with similar sensitivity (100% vs. 98.8%; P = 1.0), specificity (99.98% vs. 99.96%; P = .61), and a high PPV (85.71% vs. 97.53%; P = .06), with analogous results for T18 and T13.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, prospective, observational SMART study including 17,851 pregnant women undergoing cfDNA screening for aneuploidy and 22q11.2DS, along with DNA analysis of the fetus or newborn. Of these, 13,043 pregnancies were at low risk for aneuploidy, with the rest being high risk.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Natera, Inc, CA, USA. Some of the authors, including the lead author, received institutional research support from Natera. M Egbert, Z Demko, M Rabinowitz, and K Martin serve as an employee/consultant of Natera and own stocks/options. J Hyett has participated in expert consultancies for and B Jacobson reports research clinical diagnostic trials with Natera, among others.

Source: Dar P et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.019.

Tips for connecting with your patients

It is a tough time to be a doctor. With the stresses of the pandemic, the continued unfettered rise of insurance company BS, and so many medical groups being bought up that we often don’t even know who makes the decisions, the patient can sometimes be hidden in the equation.

Be curious

When physicians are curious about why patients have symptoms, how those symptoms will affect their lives, and how worried the patient is about them, patients feel cared about.

Ascertaining how concerned patients are about their symptoms will help you make decisions on whether symptoms you are not concerned about actually need to be treated.

Limit use of EHRs when possible

Use of the electronic health record during visits is essential, but focusing on it too much can put a barrier between the physician and the patient.

Marmor and colleagues found there is an inverse relationship between time spent on the EHR by a patient’s physician and the patient’s satisfaction.1

Eye contact with the patient is important, especially when patients are sharing concerns they are scared about and upsetting experiences. There can be awkward pauses when looking things up on the EHR. Fill those pauses by explaining to the patient what you are doing, or chatting with the patient.

Consider teaching medical students

When a medical student works with you, it doubles the time the patient gets with a concerned listener. Students also can do a great job with timely follow-up and checking in with worried patients.

By having the student present in the clinic room, with the patient present, the patient can really feel heard. The student shares all the details the patient shared, and now their physician is hearing an organized, thoughtful report of the patients concerns.

In fact, I was involved in a study that showed that patients preferred in room presentations, and that they were more satisfied when students presented in the room.2

Use healing words

Some words carry loaded emotions. The word chronic, for example, has negative connotations, whereas the term persisting does not.

I will often ask patients how long they have been suffering from a symptom to imply my concern for what they are going through. The term “chief complaint” is outdated, and upsets patients when they see it in their medical record.

As a patient of mine once said to me: “I never complained about that problem, I just brought it to your attention.” No one wants to be seen as a complainer. Substituting the word concern for complaint works well.

Explain as you examine

People love to hear the term normal. When you are examining a patient, let them know when findings are normal.

I also find it helpful to explain to patients why I am doing certain physical exam maneuvers. This helps them assess how thorough we are in our thought process.

When patients feel their physicians are thorough, they have more confidence in them.

In summary

- Be curious.

- Do not overly focus on the EHR.

- Consider teaching a medical student.

- Be careful of word choice.

- “Overexplain” the physical exam.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as 3rd-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Marmor RA et al. Appl Clin Inform. 2018 Jan;9(1):11-4.

2. Rogers HD et al. Acad Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

It is a tough time to be a doctor. With the stresses of the pandemic, the continued unfettered rise of insurance company BS, and so many medical groups being bought up that we often don’t even know who makes the decisions, the patient can sometimes be hidden in the equation.

Be curious

When physicians are curious about why patients have symptoms, how those symptoms will affect their lives, and how worried the patient is about them, patients feel cared about.

Ascertaining how concerned patients are about their symptoms will help you make decisions on whether symptoms you are not concerned about actually need to be treated.

Limit use of EHRs when possible

Use of the electronic health record during visits is essential, but focusing on it too much can put a barrier between the physician and the patient.

Marmor and colleagues found there is an inverse relationship between time spent on the EHR by a patient’s physician and the patient’s satisfaction.1

Eye contact with the patient is important, especially when patients are sharing concerns they are scared about and upsetting experiences. There can be awkward pauses when looking things up on the EHR. Fill those pauses by explaining to the patient what you are doing, or chatting with the patient.

Consider teaching medical students

When a medical student works with you, it doubles the time the patient gets with a concerned listener. Students also can do a great job with timely follow-up and checking in with worried patients.

By having the student present in the clinic room, with the patient present, the patient can really feel heard. The student shares all the details the patient shared, and now their physician is hearing an organized, thoughtful report of the patients concerns.

In fact, I was involved in a study that showed that patients preferred in room presentations, and that they were more satisfied when students presented in the room.2

Use healing words

Some words carry loaded emotions. The word chronic, for example, has negative connotations, whereas the term persisting does not.

I will often ask patients how long they have been suffering from a symptom to imply my concern for what they are going through. The term “chief complaint” is outdated, and upsets patients when they see it in their medical record.

As a patient of mine once said to me: “I never complained about that problem, I just brought it to your attention.” No one wants to be seen as a complainer. Substituting the word concern for complaint works well.

Explain as you examine

People love to hear the term normal. When you are examining a patient, let them know when findings are normal.

I also find it helpful to explain to patients why I am doing certain physical exam maneuvers. This helps them assess how thorough we are in our thought process.

When patients feel their physicians are thorough, they have more confidence in them.

In summary

- Be curious.

- Do not overly focus on the EHR.

- Consider teaching a medical student.

- Be careful of word choice.

- “Overexplain” the physical exam.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as 3rd-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Marmor RA et al. Appl Clin Inform. 2018 Jan;9(1):11-4.

2. Rogers HD et al. Acad Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

It is a tough time to be a doctor. With the stresses of the pandemic, the continued unfettered rise of insurance company BS, and so many medical groups being bought up that we often don’t even know who makes the decisions, the patient can sometimes be hidden in the equation.

Be curious

When physicians are curious about why patients have symptoms, how those symptoms will affect their lives, and how worried the patient is about them, patients feel cared about.

Ascertaining how concerned patients are about their symptoms will help you make decisions on whether symptoms you are not concerned about actually need to be treated.

Limit use of EHRs when possible

Use of the electronic health record during visits is essential, but focusing on it too much can put a barrier between the physician and the patient.

Marmor and colleagues found there is an inverse relationship between time spent on the EHR by a patient’s physician and the patient’s satisfaction.1

Eye contact with the patient is important, especially when patients are sharing concerns they are scared about and upsetting experiences. There can be awkward pauses when looking things up on the EHR. Fill those pauses by explaining to the patient what you are doing, or chatting with the patient.

Consider teaching medical students

When a medical student works with you, it doubles the time the patient gets with a concerned listener. Students also can do a great job with timely follow-up and checking in with worried patients.

By having the student present in the clinic room, with the patient present, the patient can really feel heard. The student shares all the details the patient shared, and now their physician is hearing an organized, thoughtful report of the patients concerns.

In fact, I was involved in a study that showed that patients preferred in room presentations, and that they were more satisfied when students presented in the room.2

Use healing words

Some words carry loaded emotions. The word chronic, for example, has negative connotations, whereas the term persisting does not.

I will often ask patients how long they have been suffering from a symptom to imply my concern for what they are going through. The term “chief complaint” is outdated, and upsets patients when they see it in their medical record.

As a patient of mine once said to me: “I never complained about that problem, I just brought it to your attention.” No one wants to be seen as a complainer. Substituting the word concern for complaint works well.

Explain as you examine

People love to hear the term normal. When you are examining a patient, let them know when findings are normal.

I also find it helpful to explain to patients why I am doing certain physical exam maneuvers. This helps them assess how thorough we are in our thought process.

When patients feel their physicians are thorough, they have more confidence in them.

In summary

- Be curious.

- Do not overly focus on the EHR.

- Consider teaching a medical student.

- Be careful of word choice.

- “Overexplain” the physical exam.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as 3rd-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Marmor RA et al. Appl Clin Inform. 2018 Jan;9(1):11-4.

2. Rogers HD et al. Acad Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

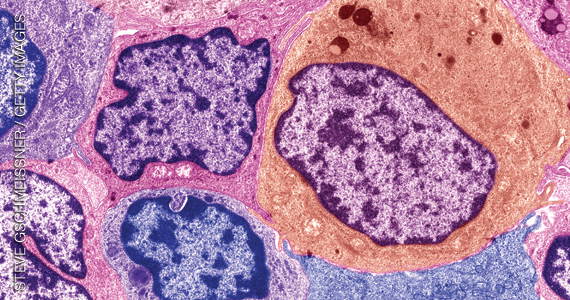

Late-onset recurrence in breast cancer: Implications for women’s health clinicians in survivorship care

Improved treatments for breast cancer (BC) and effective screening programs have resulted in a BC mortality rate reduction of 41% since 1989.1 Because BC is the leading cause of cancer in women, these mortality improvements have resulted in more than 3 million BC survivors in the United States.2,3 With longer-term survival, there is increasing interest in late-onset recurrences.4,5 A recent study has provided an improved understanding of the risk of lateonset recurrence in women with 10 years of disease-free survival, an important finding for women’s health providers because oncologists do not typically follow survivors after 10 years of disease-free survival.4

Recent study looks at incidence of late-onset recurrence

Pederson and colleagues evaluated all patients diagnosed with BC in Denmark from 1987 through 2004.4 Those patients without evidence of recurrence at 10 years were then followed utilizing population-based linked registries to identify patients who subsequently developed a local, regional, or distant late-onset recurrence. The authors evaluated the frequency of late recurrence and identified associations with demographic and tumor characteristics.

What they found

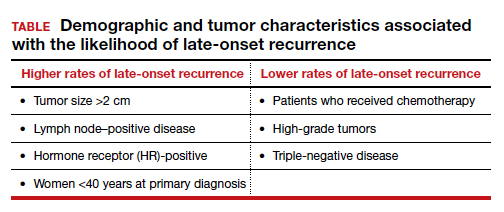

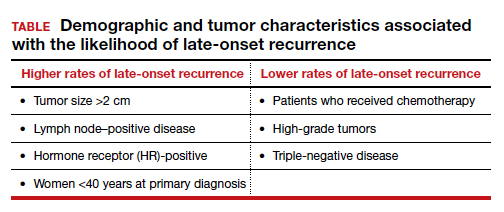

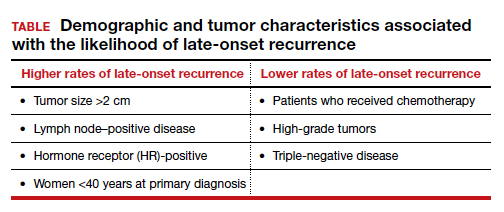

A total of 36,920 patients were diagnosed with BC in Denmark between 1987-2004, of whom 20,315 (55%) were identified as disease free for at least 10 years. Late-onset recurrence occurred in 2,595 (12.8%) with the strongest associations of recurrence seen in patients who had a tumor size >2 cm and lymph node‒positive (involving 4 or more nodes) disease (24.6%), compared with 12.7% in patients with tumors <2 cm and node-negative disease. Several other factors were associated with a higher risk of late-onset recurrence and are included in the TABLE. Half of the recurrences occurred between 10 and 15 years after the primary diagnosis.

Prior research

These findings are consistent with another recent study showing that BC patients have a 1% to 2%/year risk of recurrence after 10 disease-free years.5 Strengths of this study include:

- population-based, including all women with BC

- long-term follow-up for up to 32 years

- universal health care in Denmark, which results in robust and linked databases and very few missing data points.

There were two notable weaknesses to consider:

- Treatment regimens changed considerably during the time frame of the study (1997-2018), particularly the duration of tamoxifen use in patients with HR-positive disease. In this study nearly all patients received 5 years or less of tamoxifen. Since the mid-2010s, 10 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy has become routine in HR-positive BC, which reduces recurrences, including late-onset recurrence.6 The effect of 10 years of tamoxifen would very likely have resulted in less late-onset recurrence in the HR-positive population in this study.

- There is a lack of racial diversity in the Danish population, and the study findings may not translate to Black patients who have a higher frequency of triple-negative BC with a different risk of late-onset recurrence.7

Practice takeaways

Cancer surveillance. There are 3+ million BC survivors in the United States, and a 55%+ likelihood that they will be disease free for 10 years. This is clearly an important population to the women’s health care provider. This study, and previous research, suggests that among 10-year-disease-free survivors, 1% to 2% will recur annually, with higher rates amongst HR-positive, lymph-node positive women under age 40, and in the first 5 years following the 10-year post–initial diagnosis mark, so ongoing surveillance is imperative. Annual clinical breast examinations along with annual (not biennial) mammography should be performed.8 Digital breast tomosynthesis has improved specificity and sensitivity for BC detection and is the preferred modality when it is available.

Management of menopausal symptoms. These findings also have implications for menopausal hormone therapy for patients with symptoms. Because HR-positive patients have an increased risk of late-onset recurrence, nonhormonal therapies should be considered as first-line therapy for patients with menopausal symptoms. If hormone therapy is being considered, providers and patients should use shared decision making to balance the potential benefits (reduction in symptoms, possible cardiovascular benefits, and reduction in bone loss) with the risks (increased risk of recurrence and venous thromboembolism), even if patients are remote from the original diagnosis (ie, 10-year disease-free survival).

Topical estrogen therapies would be preferred for patients with significant urogenital atrophic symptoms who fail nonhormonal therapies due to substantially less systemic absorption and the lack of need to add a progestin.9,10 If oral therapy is being considered, I carefully counsel these women about the likely increased risk of recurrence and, if possible, include their breast oncologist in the discussion. ●

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654.

- de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561- 570. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356.

- Carreira H, Williams R, Funston G, et al. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a matched population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. PLOS Med. 2021;18:e1003504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003504.

- Pedersen RN, Esen BÖ, Mellemkjær L, et al. The incidence of breast cancer recurrence 10-32 years after primary diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. November 8, 2021. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab202.

- Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, et al. 20-year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1836- 1846. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701830.

- Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:805-816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61963-1.

- Scott LC, Mobley LR, Kuo TM, et al. Update on triple‐negative breast cancer disparities for the United States: a population‐based study from the United States Cancer Statistics database, 2010 through 2014. Cancer. 2019;125:3412-3417. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32207.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. 2021; Version 2.2022.

- Crandall CJ, Diamant A, Santoro N. Safety of vaginal estrogens: a systematic review. Menopause. 2020;27:339-360. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000001468.

- Treatment of urogenital symptoms in individuals with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer: clinical consensus. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:950-960. doi: 10.1097/AOG .0000000000004601.

Improved treatments for breast cancer (BC) and effective screening programs have resulted in a BC mortality rate reduction of 41% since 1989.1 Because BC is the leading cause of cancer in women, these mortality improvements have resulted in more than 3 million BC survivors in the United States.2,3 With longer-term survival, there is increasing interest in late-onset recurrences.4,5 A recent study has provided an improved understanding of the risk of lateonset recurrence in women with 10 years of disease-free survival, an important finding for women’s health providers because oncologists do not typically follow survivors after 10 years of disease-free survival.4

Recent study looks at incidence of late-onset recurrence

Pederson and colleagues evaluated all patients diagnosed with BC in Denmark from 1987 through 2004.4 Those patients without evidence of recurrence at 10 years were then followed utilizing population-based linked registries to identify patients who subsequently developed a local, regional, or distant late-onset recurrence. The authors evaluated the frequency of late recurrence and identified associations with demographic and tumor characteristics.

What they found

A total of 36,920 patients were diagnosed with BC in Denmark between 1987-2004, of whom 20,315 (55%) were identified as disease free for at least 10 years. Late-onset recurrence occurred in 2,595 (12.8%) with the strongest associations of recurrence seen in patients who had a tumor size >2 cm and lymph node‒positive (involving 4 or more nodes) disease (24.6%), compared with 12.7% in patients with tumors <2 cm and node-negative disease. Several other factors were associated with a higher risk of late-onset recurrence and are included in the TABLE. Half of the recurrences occurred between 10 and 15 years after the primary diagnosis.

Prior research

These findings are consistent with another recent study showing that BC patients have a 1% to 2%/year risk of recurrence after 10 disease-free years.5 Strengths of this study include:

- population-based, including all women with BC

- long-term follow-up for up to 32 years

- universal health care in Denmark, which results in robust and linked databases and very few missing data points.

There were two notable weaknesses to consider:

- Treatment regimens changed considerably during the time frame of the study (1997-2018), particularly the duration of tamoxifen use in patients with HR-positive disease. In this study nearly all patients received 5 years or less of tamoxifen. Since the mid-2010s, 10 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy has become routine in HR-positive BC, which reduces recurrences, including late-onset recurrence.6 The effect of 10 years of tamoxifen would very likely have resulted in less late-onset recurrence in the HR-positive population in this study.

- There is a lack of racial diversity in the Danish population, and the study findings may not translate to Black patients who have a higher frequency of triple-negative BC with a different risk of late-onset recurrence.7

Practice takeaways

Cancer surveillance. There are 3+ million BC survivors in the United States, and a 55%+ likelihood that they will be disease free for 10 years. This is clearly an important population to the women’s health care provider. This study, and previous research, suggests that among 10-year-disease-free survivors, 1% to 2% will recur annually, with higher rates amongst HR-positive, lymph-node positive women under age 40, and in the first 5 years following the 10-year post–initial diagnosis mark, so ongoing surveillance is imperative. Annual clinical breast examinations along with annual (not biennial) mammography should be performed.8 Digital breast tomosynthesis has improved specificity and sensitivity for BC detection and is the preferred modality when it is available.

Management of menopausal symptoms. These findings also have implications for menopausal hormone therapy for patients with symptoms. Because HR-positive patients have an increased risk of late-onset recurrence, nonhormonal therapies should be considered as first-line therapy for patients with menopausal symptoms. If hormone therapy is being considered, providers and patients should use shared decision making to balance the potential benefits (reduction in symptoms, possible cardiovascular benefits, and reduction in bone loss) with the risks (increased risk of recurrence and venous thromboembolism), even if patients are remote from the original diagnosis (ie, 10-year disease-free survival).

Topical estrogen therapies would be preferred for patients with significant urogenital atrophic symptoms who fail nonhormonal therapies due to substantially less systemic absorption and the lack of need to add a progestin.9,10 If oral therapy is being considered, I carefully counsel these women about the likely increased risk of recurrence and, if possible, include their breast oncologist in the discussion. ●

Improved treatments for breast cancer (BC) and effective screening programs have resulted in a BC mortality rate reduction of 41% since 1989.1 Because BC is the leading cause of cancer in women, these mortality improvements have resulted in more than 3 million BC survivors in the United States.2,3 With longer-term survival, there is increasing interest in late-onset recurrences.4,5 A recent study has provided an improved understanding of the risk of lateonset recurrence in women with 10 years of disease-free survival, an important finding for women’s health providers because oncologists do not typically follow survivors after 10 years of disease-free survival.4

Recent study looks at incidence of late-onset recurrence

Pederson and colleagues evaluated all patients diagnosed with BC in Denmark from 1987 through 2004.4 Those patients without evidence of recurrence at 10 years were then followed utilizing population-based linked registries to identify patients who subsequently developed a local, regional, or distant late-onset recurrence. The authors evaluated the frequency of late recurrence and identified associations with demographic and tumor characteristics.

What they found

A total of 36,920 patients were diagnosed with BC in Denmark between 1987-2004, of whom 20,315 (55%) were identified as disease free for at least 10 years. Late-onset recurrence occurred in 2,595 (12.8%) with the strongest associations of recurrence seen in patients who had a tumor size >2 cm and lymph node‒positive (involving 4 or more nodes) disease (24.6%), compared with 12.7% in patients with tumors <2 cm and node-negative disease. Several other factors were associated with a higher risk of late-onset recurrence and are included in the TABLE. Half of the recurrences occurred between 10 and 15 years after the primary diagnosis.

Prior research

These findings are consistent with another recent study showing that BC patients have a 1% to 2%/year risk of recurrence after 10 disease-free years.5 Strengths of this study include:

- population-based, including all women with BC

- long-term follow-up for up to 32 years

- universal health care in Denmark, which results in robust and linked databases and very few missing data points.

There were two notable weaknesses to consider:

- Treatment regimens changed considerably during the time frame of the study (1997-2018), particularly the duration of tamoxifen use in patients with HR-positive disease. In this study nearly all patients received 5 years or less of tamoxifen. Since the mid-2010s, 10 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy has become routine in HR-positive BC, which reduces recurrences, including late-onset recurrence.6 The effect of 10 years of tamoxifen would very likely have resulted in less late-onset recurrence in the HR-positive population in this study.

- There is a lack of racial diversity in the Danish population, and the study findings may not translate to Black patients who have a higher frequency of triple-negative BC with a different risk of late-onset recurrence.7

Practice takeaways

Cancer surveillance. There are 3+ million BC survivors in the United States, and a 55%+ likelihood that they will be disease free for 10 years. This is clearly an important population to the women’s health care provider. This study, and previous research, suggests that among 10-year-disease-free survivors, 1% to 2% will recur annually, with higher rates amongst HR-positive, lymph-node positive women under age 40, and in the first 5 years following the 10-year post–initial diagnosis mark, so ongoing surveillance is imperative. Annual clinical breast examinations along with annual (not biennial) mammography should be performed.8 Digital breast tomosynthesis has improved specificity and sensitivity for BC detection and is the preferred modality when it is available.

Management of menopausal symptoms. These findings also have implications for menopausal hormone therapy for patients with symptoms. Because HR-positive patients have an increased risk of late-onset recurrence, nonhormonal therapies should be considered as first-line therapy for patients with menopausal symptoms. If hormone therapy is being considered, providers and patients should use shared decision making to balance the potential benefits (reduction in symptoms, possible cardiovascular benefits, and reduction in bone loss) with the risks (increased risk of recurrence and venous thromboembolism), even if patients are remote from the original diagnosis (ie, 10-year disease-free survival).

Topical estrogen therapies would be preferred for patients with significant urogenital atrophic symptoms who fail nonhormonal therapies due to substantially less systemic absorption and the lack of need to add a progestin.9,10 If oral therapy is being considered, I carefully counsel these women about the likely increased risk of recurrence and, if possible, include their breast oncologist in the discussion. ●

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654.

- de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561- 570. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356.

- Carreira H, Williams R, Funston G, et al. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a matched population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. PLOS Med. 2021;18:e1003504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003504.

- Pedersen RN, Esen BÖ, Mellemkjær L, et al. The incidence of breast cancer recurrence 10-32 years after primary diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. November 8, 2021. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab202.

- Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, et al. 20-year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1836- 1846. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701830.

- Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:805-816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61963-1.

- Scott LC, Mobley LR, Kuo TM, et al. Update on triple‐negative breast cancer disparities for the United States: a population‐based study from the United States Cancer Statistics database, 2010 through 2014. Cancer. 2019;125:3412-3417. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32207.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. 2021; Version 2.2022.

- Crandall CJ, Diamant A, Santoro N. Safety of vaginal estrogens: a systematic review. Menopause. 2020;27:339-360. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000001468.

- Treatment of urogenital symptoms in individuals with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer: clinical consensus. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:950-960. doi: 10.1097/AOG .0000000000004601.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654.

- de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561- 570. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356.

- Carreira H, Williams R, Funston G, et al. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a matched population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. PLOS Med. 2021;18:e1003504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003504.

- Pedersen RN, Esen BÖ, Mellemkjær L, et al. The incidence of breast cancer recurrence 10-32 years after primary diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. November 8, 2021. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab202.

- Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, et al. 20-year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1836- 1846. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701830.

- Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:805-816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61963-1.

- Scott LC, Mobley LR, Kuo TM, et al. Update on triple‐negative breast cancer disparities for the United States: a population‐based study from the United States Cancer Statistics database, 2010 through 2014. Cancer. 2019;125:3412-3417. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32207.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. 2021; Version 2.2022.

- Crandall CJ, Diamant A, Santoro N. Safety of vaginal estrogens: a systematic review. Menopause. 2020;27:339-360. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000001468.

- Treatment of urogenital symptoms in individuals with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer: clinical consensus. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:950-960. doi: 10.1097/AOG .0000000000004601.

Long COVID symptoms linked to effects on vagus nerve

Several long COVID symptoms could be linked to the effects of the coronavirus on a vital central nerve, according to new research being released in the spring.

The vagus nerve, which runs from the brain into the body, connects to the heart, lungs, intestines, and several muscles involved with swallowing. It plays a role in several body functions that control heart rate, speech, the gag reflex, sweating, and digestion.

Those with long COVID and vagus nerve problems could face long-term issues with their voice, a hard time swallowing, dizziness, a high heart rate, low blood pressure, and diarrhea, the study authors found.

Their findings will be presented at the 2022 European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in late April.

“Most long COVID subjects with vagus nerve dysfunction symptoms had a range of significant, clinically relevant, structural and/or functional alterations in their vagus nerve, including nerve thickening, trouble swallowing, and symptoms of impaired breathing,” the study authors wrote. “Our findings so far thus point at vagus nerve dysfunction as a central pathophysiological feature of long COVID.”

Researchers from the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol in Barcelona performed a study to look at vagus nerve functioning in long COVID patients. Among 348 patients, about 66% had at least one symptom that suggested vagus nerve dysfunction. The researchers did a broad evaluation with imaging and functional tests for 22 patients in the university’s Long COVID Clinic from March to June 2021.

Of the 22 patients, 20 were women, and the median age was 44. The most frequent symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction were diarrhea (73%), high heart rates (59%), dizziness (45%), swallowing problems (45%), voice problems (45%), and low blood pressure (14%).

Almost all (19 of 22 patients) had three or more symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction. The average length of symptoms was 14 months.

Of 22 patients, 6 had a change in the vagus nerve in the neck, which the researchers observed by ultrasound. They had a thickening of the vagus nerve and increased “echogenicity,” which suggests inflammation.

What’s more, 10 of 22 patients had flattened “diaphragmatic curves” during a thoracic ultrasound, which means the diaphragm doesn’t move as well as it should during breathing, and abnormal breathing. In another assessment, 10 of 16 patients had lower maximum inspiration pressures, suggesting a weakness in breathing muscles.

Eating and digestion were also impaired in some patients, with 13 reporting trouble with swallowing. During a gastric and bowel function assessment, eight patients couldn’t move food from the esophagus to the stomach as well as they should, while nine patients had acid reflux. Three patients had a hiatal hernia, which happens when the upper part of the stomach bulges through the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

The voices of some patients changed as well. Eight patients had an abnormal voice handicap index 30 test, which is a standard way to measure voice function. Among those, seven patients had dysphonia, or persistent voice problems.

The study is ongoing, and the research team is continuing to recruit patients to study the links between long COVID and the vagus nerve. The full paper isn’t yet available, and the research hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“The study appears to add to a growing collection of data suggesting at least some of the symptoms of long COVID is mediated through a direct impact on the nervous system,” David Strain, MD, a clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter (England), told the Science Media Centre.

“Establishing vagal nerve damage is useful information, as there are recognized, albeit not perfect, treatments for other causes of vagal nerve dysfunction that may be extrapolated to be beneficial for people with this type of long COVID,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Several long COVID symptoms could be linked to the effects of the coronavirus on a vital central nerve, according to new research being released in the spring.

The vagus nerve, which runs from the brain into the body, connects to the heart, lungs, intestines, and several muscles involved with swallowing. It plays a role in several body functions that control heart rate, speech, the gag reflex, sweating, and digestion.

Those with long COVID and vagus nerve problems could face long-term issues with their voice, a hard time swallowing, dizziness, a high heart rate, low blood pressure, and diarrhea, the study authors found.

Their findings will be presented at the 2022 European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in late April.

“Most long COVID subjects with vagus nerve dysfunction symptoms had a range of significant, clinically relevant, structural and/or functional alterations in their vagus nerve, including nerve thickening, trouble swallowing, and symptoms of impaired breathing,” the study authors wrote. “Our findings so far thus point at vagus nerve dysfunction as a central pathophysiological feature of long COVID.”

Researchers from the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol in Barcelona performed a study to look at vagus nerve functioning in long COVID patients. Among 348 patients, about 66% had at least one symptom that suggested vagus nerve dysfunction. The researchers did a broad evaluation with imaging and functional tests for 22 patients in the university’s Long COVID Clinic from March to June 2021.

Of the 22 patients, 20 were women, and the median age was 44. The most frequent symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction were diarrhea (73%), high heart rates (59%), dizziness (45%), swallowing problems (45%), voice problems (45%), and low blood pressure (14%).

Almost all (19 of 22 patients) had three or more symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction. The average length of symptoms was 14 months.

Of 22 patients, 6 had a change in the vagus nerve in the neck, which the researchers observed by ultrasound. They had a thickening of the vagus nerve and increased “echogenicity,” which suggests inflammation.

What’s more, 10 of 22 patients had flattened “diaphragmatic curves” during a thoracic ultrasound, which means the diaphragm doesn’t move as well as it should during breathing, and abnormal breathing. In another assessment, 10 of 16 patients had lower maximum inspiration pressures, suggesting a weakness in breathing muscles.

Eating and digestion were also impaired in some patients, with 13 reporting trouble with swallowing. During a gastric and bowel function assessment, eight patients couldn’t move food from the esophagus to the stomach as well as they should, while nine patients had acid reflux. Three patients had a hiatal hernia, which happens when the upper part of the stomach bulges through the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

The voices of some patients changed as well. Eight patients had an abnormal voice handicap index 30 test, which is a standard way to measure voice function. Among those, seven patients had dysphonia, or persistent voice problems.

The study is ongoing, and the research team is continuing to recruit patients to study the links between long COVID and the vagus nerve. The full paper isn’t yet available, and the research hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“The study appears to add to a growing collection of data suggesting at least some of the symptoms of long COVID is mediated through a direct impact on the nervous system,” David Strain, MD, a clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter (England), told the Science Media Centre.

“Establishing vagal nerve damage is useful information, as there are recognized, albeit not perfect, treatments for other causes of vagal nerve dysfunction that may be extrapolated to be beneficial for people with this type of long COVID,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Several long COVID symptoms could be linked to the effects of the coronavirus on a vital central nerve, according to new research being released in the spring.

The vagus nerve, which runs from the brain into the body, connects to the heart, lungs, intestines, and several muscles involved with swallowing. It plays a role in several body functions that control heart rate, speech, the gag reflex, sweating, and digestion.

Those with long COVID and vagus nerve problems could face long-term issues with their voice, a hard time swallowing, dizziness, a high heart rate, low blood pressure, and diarrhea, the study authors found.

Their findings will be presented at the 2022 European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in late April.

“Most long COVID subjects with vagus nerve dysfunction symptoms had a range of significant, clinically relevant, structural and/or functional alterations in their vagus nerve, including nerve thickening, trouble swallowing, and symptoms of impaired breathing,” the study authors wrote. “Our findings so far thus point at vagus nerve dysfunction as a central pathophysiological feature of long COVID.”

Researchers from the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol in Barcelona performed a study to look at vagus nerve functioning in long COVID patients. Among 348 patients, about 66% had at least one symptom that suggested vagus nerve dysfunction. The researchers did a broad evaluation with imaging and functional tests for 22 patients in the university’s Long COVID Clinic from March to June 2021.

Of the 22 patients, 20 were women, and the median age was 44. The most frequent symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction were diarrhea (73%), high heart rates (59%), dizziness (45%), swallowing problems (45%), voice problems (45%), and low blood pressure (14%).

Almost all (19 of 22 patients) had three or more symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction. The average length of symptoms was 14 months.

Of 22 patients, 6 had a change in the vagus nerve in the neck, which the researchers observed by ultrasound. They had a thickening of the vagus nerve and increased “echogenicity,” which suggests inflammation.

What’s more, 10 of 22 patients had flattened “diaphragmatic curves” during a thoracic ultrasound, which means the diaphragm doesn’t move as well as it should during breathing, and abnormal breathing. In another assessment, 10 of 16 patients had lower maximum inspiration pressures, suggesting a weakness in breathing muscles.

Eating and digestion were also impaired in some patients, with 13 reporting trouble with swallowing. During a gastric and bowel function assessment, eight patients couldn’t move food from the esophagus to the stomach as well as they should, while nine patients had acid reflux. Three patients had a hiatal hernia, which happens when the upper part of the stomach bulges through the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

The voices of some patients changed as well. Eight patients had an abnormal voice handicap index 30 test, which is a standard way to measure voice function. Among those, seven patients had dysphonia, or persistent voice problems.

The study is ongoing, and the research team is continuing to recruit patients to study the links between long COVID and the vagus nerve. The full paper isn’t yet available, and the research hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“The study appears to add to a growing collection of data suggesting at least some of the symptoms of long COVID is mediated through a direct impact on the nervous system,” David Strain, MD, a clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter (England), told the Science Media Centre.

“Establishing vagal nerve damage is useful information, as there are recognized, albeit not perfect, treatments for other causes of vagal nerve dysfunction that may be extrapolated to be beneficial for people with this type of long COVID,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Estrogen supplementation may reduce COVID-19 death risk

Estrogen supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19 among postmenopausal women, new research suggests.

The findings, from a nationwide study using data from Sweden, were published online Feb. 14 in BMJ Open by Malin Sund, MD, PhD, of Umeå (Sweden) University Faculty of Medicine and colleagues.

Among postmenopausal women aged 50-80 years with verified COVID-19, those receiving estrogen as part of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms were less than half as likely to die from it as those not receiving estrogen, even after adjustment for confounders.

“This study shows an association between estrogen levels and COVID-19 death. Consequently, drugs increasing estrogen levels may have a role in therapeutic efforts to alleviate COVID-19 severity in postmenopausal women and could be studied in randomized control trials,” the investigators write.

However, coauthor Anne-Marie Fors Connolly, MD, PhD, a resident in clinical microbiology at Umeå University, cautioned: “This is an observational study. Further clinical studies are needed to verify these results before recommending clinicians to consider estrogen supplementation.”

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, agrees.

He told the U.K. Science and Media Centre: “This is an observational study comparing three groups of women based on whether they used hormonal therapy to boost estrogen levels or who had, as a result of treatment for breast cancer ... reduced estrogen levels or neither. The findings are apparently dramatic.”

“At the very least, great caution should be exercised in thinking that menopausal hormone therapy will have substantial, or even any, benefits in dealing with COVID-19,” he warned.

Do women die less frequently from COVID-19 than men?

Studies conducted early in the pandemic suggest women may be protected from poor outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with men, even after adjustment for confounders.

According to more recent data from the Swedish Public Health Agency, of the 16,501 people who have died from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, about 45% are women and 55% are men. About 70% who have received intensive care because of COVID-19 are men, although cumulative data suggest that women are nearly as likely to die from COVID-19 as men, Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

For the current study, a total of 14,685 women aged 50-80 years were included, of whom 17.3% (2,535) had received estrogen supplementation, 81.2% (11,923) had native estrogen levels with no breast cancer or estrogen supplementation (controls), and 1.5% (227) had decreased estrogen levels because of breast cancer and antiestrogen treatment.

The group with decreased estrogen levels had a more than twofold risk of dying from COVID-19 compared with controls (odds ratio, 2.35), but this difference was no longer significant after adjustments for potential confounders including age, income, and educational level, and weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index (wCCI).

However, the group with augmented estrogen levels had a decreased risk of dying from COVID-19 before (odds ratio, 0.45) and after (OR, 0.47) adjustment.

The percentages of patients who died of COVID-19 were 4.6% of controls, 10.1% of those with decreased estrogen, and 2.1% with increased estrogen.

Not surprisingly, the risk of dying from COVID-19 also increased with age (OR of 1.15 for every year increase in age) and comorbidities (OR, 1.13 per increase in wCCI). Low income and having only a primary level education also increased the odds of dying from COVID-19.

Data on obesity, a known risk factor for COVID-19 death, weren’t reported.

“Obesity would have been a very relevant variable to include. Unfortunately, this information is not present in the nationwide registry data that we used for our study,” Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

While the data are observational and can’t be used to inform treatment, Dr. Connolly pointed to a U.S. randomized clinical trial currently recruiting patients that will investigate the effect of estradiol and progesterone therapy in 120 adults hospitalized with COVID-19.

In the meantime, she warned doctors and patients: “Please do not consider ending antiestrogen treatment following breast cancer – this is a necessary treatment for the cancer.”

Dr. Evans noted, “There are short-term benefits of menopausal hormone therapy but women should not, based on this or other observational studies, be advised to take HRT [hormone replacement therapy] for a supposed benefit on death from COVID-19.”

The study had several nonpharmaceutical industry funders, including Umeå University and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The authors and Dr. Evans have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Estrogen supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19 among postmenopausal women, new research suggests.

The findings, from a nationwide study using data from Sweden, were published online Feb. 14 in BMJ Open by Malin Sund, MD, PhD, of Umeå (Sweden) University Faculty of Medicine and colleagues.

Among postmenopausal women aged 50-80 years with verified COVID-19, those receiving estrogen as part of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms were less than half as likely to die from it as those not receiving estrogen, even after adjustment for confounders.

“This study shows an association between estrogen levels and COVID-19 death. Consequently, drugs increasing estrogen levels may have a role in therapeutic efforts to alleviate COVID-19 severity in postmenopausal women and could be studied in randomized control trials,” the investigators write.

However, coauthor Anne-Marie Fors Connolly, MD, PhD, a resident in clinical microbiology at Umeå University, cautioned: “This is an observational study. Further clinical studies are needed to verify these results before recommending clinicians to consider estrogen supplementation.”

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, agrees.

He told the U.K. Science and Media Centre: “This is an observational study comparing three groups of women based on whether they used hormonal therapy to boost estrogen levels or who had, as a result of treatment for breast cancer ... reduced estrogen levels or neither. The findings are apparently dramatic.”

“At the very least, great caution should be exercised in thinking that menopausal hormone therapy will have substantial, or even any, benefits in dealing with COVID-19,” he warned.

Do women die less frequently from COVID-19 than men?

Studies conducted early in the pandemic suggest women may be protected from poor outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with men, even after adjustment for confounders.

According to more recent data from the Swedish Public Health Agency, of the 16,501 people who have died from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, about 45% are women and 55% are men. About 70% who have received intensive care because of COVID-19 are men, although cumulative data suggest that women are nearly as likely to die from COVID-19 as men, Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

For the current study, a total of 14,685 women aged 50-80 years were included, of whom 17.3% (2,535) had received estrogen supplementation, 81.2% (11,923) had native estrogen levels with no breast cancer or estrogen supplementation (controls), and 1.5% (227) had decreased estrogen levels because of breast cancer and antiestrogen treatment.

The group with decreased estrogen levels had a more than twofold risk of dying from COVID-19 compared with controls (odds ratio, 2.35), but this difference was no longer significant after adjustments for potential confounders including age, income, and educational level, and weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index (wCCI).

However, the group with augmented estrogen levels had a decreased risk of dying from COVID-19 before (odds ratio, 0.45) and after (OR, 0.47) adjustment.

The percentages of patients who died of COVID-19 were 4.6% of controls, 10.1% of those with decreased estrogen, and 2.1% with increased estrogen.

Not surprisingly, the risk of dying from COVID-19 also increased with age (OR of 1.15 for every year increase in age) and comorbidities (OR, 1.13 per increase in wCCI). Low income and having only a primary level education also increased the odds of dying from COVID-19.

Data on obesity, a known risk factor for COVID-19 death, weren’t reported.

“Obesity would have been a very relevant variable to include. Unfortunately, this information is not present in the nationwide registry data that we used for our study,” Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

While the data are observational and can’t be used to inform treatment, Dr. Connolly pointed to a U.S. randomized clinical trial currently recruiting patients that will investigate the effect of estradiol and progesterone therapy in 120 adults hospitalized with COVID-19.

In the meantime, she warned doctors and patients: “Please do not consider ending antiestrogen treatment following breast cancer – this is a necessary treatment for the cancer.”

Dr. Evans noted, “There are short-term benefits of menopausal hormone therapy but women should not, based on this or other observational studies, be advised to take HRT [hormone replacement therapy] for a supposed benefit on death from COVID-19.”

The study had several nonpharmaceutical industry funders, including Umeå University and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The authors and Dr. Evans have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Estrogen supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19 among postmenopausal women, new research suggests.

The findings, from a nationwide study using data from Sweden, were published online Feb. 14 in BMJ Open by Malin Sund, MD, PhD, of Umeå (Sweden) University Faculty of Medicine and colleagues.

Among postmenopausal women aged 50-80 years with verified COVID-19, those receiving estrogen as part of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms were less than half as likely to die from it as those not receiving estrogen, even after adjustment for confounders.

“This study shows an association between estrogen levels and COVID-19 death. Consequently, drugs increasing estrogen levels may have a role in therapeutic efforts to alleviate COVID-19 severity in postmenopausal women and could be studied in randomized control trials,” the investigators write.

However, coauthor Anne-Marie Fors Connolly, MD, PhD, a resident in clinical microbiology at Umeå University, cautioned: “This is an observational study. Further clinical studies are needed to verify these results before recommending clinicians to consider estrogen supplementation.”

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, agrees.

He told the U.K. Science and Media Centre: “This is an observational study comparing three groups of women based on whether they used hormonal therapy to boost estrogen levels or who had, as a result of treatment for breast cancer ... reduced estrogen levels or neither. The findings are apparently dramatic.”

“At the very least, great caution should be exercised in thinking that menopausal hormone therapy will have substantial, or even any, benefits in dealing with COVID-19,” he warned.

Do women die less frequently from COVID-19 than men?

Studies conducted early in the pandemic suggest women may be protected from poor outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with men, even after adjustment for confounders.

According to more recent data from the Swedish Public Health Agency, of the 16,501 people who have died from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, about 45% are women and 55% are men. About 70% who have received intensive care because of COVID-19 are men, although cumulative data suggest that women are nearly as likely to die from COVID-19 as men, Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

For the current study, a total of 14,685 women aged 50-80 years were included, of whom 17.3% (2,535) had received estrogen supplementation, 81.2% (11,923) had native estrogen levels with no breast cancer or estrogen supplementation (controls), and 1.5% (227) had decreased estrogen levels because of breast cancer and antiestrogen treatment.

The group with decreased estrogen levels had a more than twofold risk of dying from COVID-19 compared with controls (odds ratio, 2.35), but this difference was no longer significant after adjustments for potential confounders including age, income, and educational level, and weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index (wCCI).

However, the group with augmented estrogen levels had a decreased risk of dying from COVID-19 before (odds ratio, 0.45) and after (OR, 0.47) adjustment.

The percentages of patients who died of COVID-19 were 4.6% of controls, 10.1% of those with decreased estrogen, and 2.1% with increased estrogen.

Not surprisingly, the risk of dying from COVID-19 also increased with age (OR of 1.15 for every year increase in age) and comorbidities (OR, 1.13 per increase in wCCI). Low income and having only a primary level education also increased the odds of dying from COVID-19.

Data on obesity, a known risk factor for COVID-19 death, weren’t reported.

“Obesity would have been a very relevant variable to include. Unfortunately, this information is not present in the nationwide registry data that we used for our study,” Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

While the data are observational and can’t be used to inform treatment, Dr. Connolly pointed to a U.S. randomized clinical trial currently recruiting patients that will investigate the effect of estradiol and progesterone therapy in 120 adults hospitalized with COVID-19.

In the meantime, she warned doctors and patients: “Please do not consider ending antiestrogen treatment following breast cancer – this is a necessary treatment for the cancer.”

Dr. Evans noted, “There are short-term benefits of menopausal hormone therapy but women should not, based on this or other observational studies, be advised to take HRT [hormone replacement therapy] for a supposed benefit on death from COVID-19.”

The study had several nonpharmaceutical industry funders, including Umeå University and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The authors and Dr. Evans have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

PCOS common in adolescent girls with type 2 diabetes

Polycystic ovary syndrome is common in girls with type 2 diabetes, findings of a new study suggest, and authors say screening for PCOS is critical in this group.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 470 girls (average age 12.9-16.1 years) with type 2 diabetes in six studies, the prevalence of PCOS was nearly 1 in 5 (19.58%; 95% confidence interval, 12.02%-27.14%; P = .002), substantially higher than that of PCOS in the general adolescent population.

PCOS, a complex endocrine disorder, occurs in 1.14%-11.04% of adolescent girls globally, according to the paper published online in JAMA Network Open.

The secondary outcome studied links to prevalence of PCOS with race and obesity.

Insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia are present in 44%-70% of women with PCOS, suggesting that they are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes, according to the researchers led by Milena Cioana, BHSc, with the department of pediatrics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Kelly A. Curran, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City, where she practices adolescent medicine, said in an interview that it has been known that women with PCOS have higher rates of diabetes and many in the field have suspected the relationship is bidirectional.

“In my clinical practice, I’ve seen a high percentage of women with type 2 diabetes present with irregular menses, some of whom have gone on to be diagnosed with PCOS,” said Dr. Curran, who was not involved with the study.

However, she said, she was surprised the prevalence of PCOS reported in this paper – nearly one in five – was so high. Early diagnosis is important for PCOS to prevent complications such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia.

Psychiatric conditions are also prevalent in patients with PCOS, including anxiety (18%), depression (16%), and ADHD (9%).

Dr. Curran agreed there is a need to screen for PCOS and to evaluate for other causes of irregular periods in patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Menstrual irregularities are often overlooked in young women without further work-up, especially in patients who have chronic illnesses,” she noted.

Results come with a caveat

However, the authors said, results should be viewed with caution because “studies including the larger numbers of girls did not report the criteria used to diagnose PCOS, which is a challenge during adolescence.”

Diagnostic criteria for PCOS during adolescence include the combination of menstrual irregularities according to time since their first period and clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism after excluding other potential causes.

Dr. Curran explained that PCOS symptoms include irregular periods and acne which can overlap with normal changes in puberty. In her experience, PCOS is often diagnosed without patients meeting full criteria. She agreed further research with standardized criteria is urgently needed.

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/American Society of Reproductive Medicine, the Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the International Consortium of Paediatric Endocrinology guidelines suggest that using ultrasound to check the size of ovaries could help diagnose PCOS, but other guidelines are more conservative, the authors noted.

They added that “there is a need for a consensus to establish the pediatric criteria for diagnosing PCOS in adolescents to ensure accurate diagnosis and lower the misclassification rates.”

Assessing links to obesity and race

Still unclear, the authors wrote, is whether and how obesity and race affect prevalence of PCOS among girls with type 2 diabetes.

The authors wrote: “Although earlier studies suggested that obesity-related insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia can contribute to PCOS pathogenesis, insulin resistance in patients with PCOS may be present independently of [body mass index]. Obesity seems to increase the risk of PCOS only slightly and might represent a referral bias for PCOS.”

Few studies included in the meta-analysis had race-specific data, so the authors were limited in assessing associations between race and PCOS prevalence.

“However,” they wrote, “our data demonstrate that Indian girls had the highest prevalence, followed by White girls, and then Indigenous girls in Canada.”

Further studies are needed to help define at-risk subgroups and evaluate treatment strategies, the authors noted.

They reported having no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Curran had no conflicts of interest.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is common in girls with type 2 diabetes, findings of a new study suggest, and authors say screening for PCOS is critical in this group.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 470 girls (average age 12.9-16.1 years) with type 2 diabetes in six studies, the prevalence of PCOS was nearly 1 in 5 (19.58%; 95% confidence interval, 12.02%-27.14%; P = .002), substantially higher than that of PCOS in the general adolescent population.

PCOS, a complex endocrine disorder, occurs in 1.14%-11.04% of adolescent girls globally, according to the paper published online in JAMA Network Open.

The secondary outcome studied links to prevalence of PCOS with race and obesity.

Insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia are present in 44%-70% of women with PCOS, suggesting that they are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes, according to the researchers led by Milena Cioana, BHSc, with the department of pediatrics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Kelly A. Curran, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City, where she practices adolescent medicine, said in an interview that it has been known that women with PCOS have higher rates of diabetes and many in the field have suspected the relationship is bidirectional.

“In my clinical practice, I’ve seen a high percentage of women with type 2 diabetes present with irregular menses, some of whom have gone on to be diagnosed with PCOS,” said Dr. Curran, who was not involved with the study.

However, she said, she was surprised the prevalence of PCOS reported in this paper – nearly one in five – was so high. Early diagnosis is important for PCOS to prevent complications such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia.

Psychiatric conditions are also prevalent in patients with PCOS, including anxiety (18%), depression (16%), and ADHD (9%).

Dr. Curran agreed there is a need to screen for PCOS and to evaluate for other causes of irregular periods in patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Menstrual irregularities are often overlooked in young women without further work-up, especially in patients who have chronic illnesses,” she noted.

Results come with a caveat

However, the authors said, results should be viewed with caution because “studies including the larger numbers of girls did not report the criteria used to diagnose PCOS, which is a challenge during adolescence.”

Diagnostic criteria for PCOS during adolescence include the combination of menstrual irregularities according to time since their first period and clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism after excluding other potential causes.

Dr. Curran explained that PCOS symptoms include irregular periods and acne which can overlap with normal changes in puberty. In her experience, PCOS is often diagnosed without patients meeting full criteria. She agreed further research with standardized criteria is urgently needed.