User login

Hold rectal surgery decision until neoadjuvant chemo is done

BOSTON – Good results come to those who wait, suggest the findings of a study of optimal timing of surgical decisions in patients with advanced stage cancers in the distal rectum.

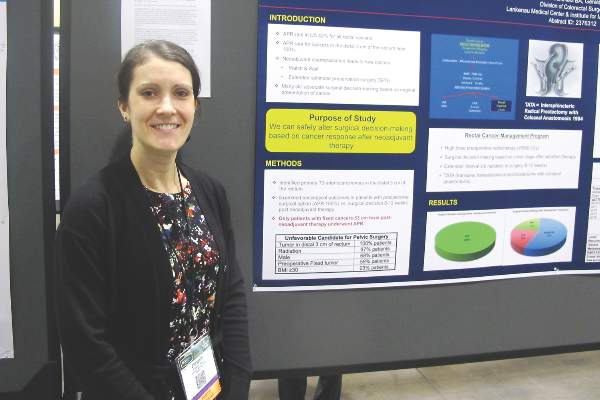

When surgeons waited 8 to 12 weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant chemoradiation to decide whether to proceed with radical sphincter preservation surgery (SPS) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) in patients with T3 cancers of the distal third of the rectum, they were able to avoid creating a colostomy with no adverse oncologic outcomes in 79% of patients, reported Dr. Elizabeth A. Myers and her colleagues from the Lankenau Medical Center and Institute for Medical Research in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

“An interesting thing, but still quite controversial, is the timing of when you do surgery,” Dr. Myers said in an interview during a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

“There is a large school of thought that still believes you should base your surgical plan on the tumor at its presentation, versus making the decision once the patient has undergone neoadjuvant chemoradiation treatment. The purpose of our study is to show with our data that you can safely alter your decision making based on what the cancer presents as following neoadjuvant chemoradiation,” she said.

The investigators looked at 192 consecutive patients with T3 cancers of the distal third of the rectum who were included in a prospectively maintained database. At the time of presentation, all of the patients would have met criteria for requiring APR and colostomy, due to unfavorable factors for pelvic surgery such as prior radiation (97%), male sex (68%), preoperative fixed tumor (59%), or obesity (23%).

The patients underwent neoadjuvant radiation given at a mean of dose of 5,580 cGy, consisting of a 4,500 cGy standard dose and a 1,080 cGy boost to the area of tumor. Most (87%) also received concurrent 5-fluorauracil-based chemotherapy.

“We have found that this helps to downgrade the tumor quite well,” Dr. Myers said.

Following the completion of therapy, they waited for 8 to 12 additional weeks before planning surgery to allow for the maximum benefit of radiation.

All patients, except those who at the end of neoadjuvant chemotherapy still had a fixed cancer at the 3 cm level or below, were offered SPS. The mean time from completion of chemotherapy to surgery was 11 weeks.

Of the 192 patients, 41 underwent APR, 109 had radical SPS, including 107 receiving transanal transabdominal proctocolectomy with coloanal anastomosis (TATA), and 2 receiving low anterior resection. The remaining patients had local excision with either a transanal technique (TAE; 15 patients) or transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM, 27 patients).

After a mean follow-up of 55.4 months (range, 1-242 months) the 5-year stoma-free survival rate was 79%. Kaplan-Meier 5-year actuarial survival rates were 98% for all patients who underwent radical SPS, 100% for those who had local excision with TEM, 82% for those who had local excision with TAE (combined SPS procedures, 95%), and 72% for patients who underwent APR.

Local recurrences occurred in 6.6% of all patients who underwent SPS, compared with 7.3% of those who underwent APR. Distant metastases occurred in 22.5% and 24.4%, respectively.

“Holding surgical decision-making until after completion of neoadjuvant therapy allows for increased sphincter preservation with good oncologic outcomes in rectal cancer patients,” the investigators concluded.

BOSTON – Good results come to those who wait, suggest the findings of a study of optimal timing of surgical decisions in patients with advanced stage cancers in the distal rectum.

When surgeons waited 8 to 12 weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant chemoradiation to decide whether to proceed with radical sphincter preservation surgery (SPS) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) in patients with T3 cancers of the distal third of the rectum, they were able to avoid creating a colostomy with no adverse oncologic outcomes in 79% of patients, reported Dr. Elizabeth A. Myers and her colleagues from the Lankenau Medical Center and Institute for Medical Research in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

“An interesting thing, but still quite controversial, is the timing of when you do surgery,” Dr. Myers said in an interview during a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

“There is a large school of thought that still believes you should base your surgical plan on the tumor at its presentation, versus making the decision once the patient has undergone neoadjuvant chemoradiation treatment. The purpose of our study is to show with our data that you can safely alter your decision making based on what the cancer presents as following neoadjuvant chemoradiation,” she said.

The investigators looked at 192 consecutive patients with T3 cancers of the distal third of the rectum who were included in a prospectively maintained database. At the time of presentation, all of the patients would have met criteria for requiring APR and colostomy, due to unfavorable factors for pelvic surgery such as prior radiation (97%), male sex (68%), preoperative fixed tumor (59%), or obesity (23%).

The patients underwent neoadjuvant radiation given at a mean of dose of 5,580 cGy, consisting of a 4,500 cGy standard dose and a 1,080 cGy boost to the area of tumor. Most (87%) also received concurrent 5-fluorauracil-based chemotherapy.

“We have found that this helps to downgrade the tumor quite well,” Dr. Myers said.

Following the completion of therapy, they waited for 8 to 12 additional weeks before planning surgery to allow for the maximum benefit of radiation.

All patients, except those who at the end of neoadjuvant chemotherapy still had a fixed cancer at the 3 cm level or below, were offered SPS. The mean time from completion of chemotherapy to surgery was 11 weeks.

Of the 192 patients, 41 underwent APR, 109 had radical SPS, including 107 receiving transanal transabdominal proctocolectomy with coloanal anastomosis (TATA), and 2 receiving low anterior resection. The remaining patients had local excision with either a transanal technique (TAE; 15 patients) or transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM, 27 patients).

After a mean follow-up of 55.4 months (range, 1-242 months) the 5-year stoma-free survival rate was 79%. Kaplan-Meier 5-year actuarial survival rates were 98% for all patients who underwent radical SPS, 100% for those who had local excision with TEM, 82% for those who had local excision with TAE (combined SPS procedures, 95%), and 72% for patients who underwent APR.

Local recurrences occurred in 6.6% of all patients who underwent SPS, compared with 7.3% of those who underwent APR. Distant metastases occurred in 22.5% and 24.4%, respectively.

“Holding surgical decision-making until after completion of neoadjuvant therapy allows for increased sphincter preservation with good oncologic outcomes in rectal cancer patients,” the investigators concluded.

BOSTON – Good results come to those who wait, suggest the findings of a study of optimal timing of surgical decisions in patients with advanced stage cancers in the distal rectum.

When surgeons waited 8 to 12 weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant chemoradiation to decide whether to proceed with radical sphincter preservation surgery (SPS) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) in patients with T3 cancers of the distal third of the rectum, they were able to avoid creating a colostomy with no adverse oncologic outcomes in 79% of patients, reported Dr. Elizabeth A. Myers and her colleagues from the Lankenau Medical Center and Institute for Medical Research in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

“An interesting thing, but still quite controversial, is the timing of when you do surgery,” Dr. Myers said in an interview during a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

“There is a large school of thought that still believes you should base your surgical plan on the tumor at its presentation, versus making the decision once the patient has undergone neoadjuvant chemoradiation treatment. The purpose of our study is to show with our data that you can safely alter your decision making based on what the cancer presents as following neoadjuvant chemoradiation,” she said.

The investigators looked at 192 consecutive patients with T3 cancers of the distal third of the rectum who were included in a prospectively maintained database. At the time of presentation, all of the patients would have met criteria for requiring APR and colostomy, due to unfavorable factors for pelvic surgery such as prior radiation (97%), male sex (68%), preoperative fixed tumor (59%), or obesity (23%).

The patients underwent neoadjuvant radiation given at a mean of dose of 5,580 cGy, consisting of a 4,500 cGy standard dose and a 1,080 cGy boost to the area of tumor. Most (87%) also received concurrent 5-fluorauracil-based chemotherapy.

“We have found that this helps to downgrade the tumor quite well,” Dr. Myers said.

Following the completion of therapy, they waited for 8 to 12 additional weeks before planning surgery to allow for the maximum benefit of radiation.

All patients, except those who at the end of neoadjuvant chemotherapy still had a fixed cancer at the 3 cm level or below, were offered SPS. The mean time from completion of chemotherapy to surgery was 11 weeks.

Of the 192 patients, 41 underwent APR, 109 had radical SPS, including 107 receiving transanal transabdominal proctocolectomy with coloanal anastomosis (TATA), and 2 receiving low anterior resection. The remaining patients had local excision with either a transanal technique (TAE; 15 patients) or transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM, 27 patients).

After a mean follow-up of 55.4 months (range, 1-242 months) the 5-year stoma-free survival rate was 79%. Kaplan-Meier 5-year actuarial survival rates were 98% for all patients who underwent radical SPS, 100% for those who had local excision with TEM, 82% for those who had local excision with TAE (combined SPS procedures, 95%), and 72% for patients who underwent APR.

Local recurrences occurred in 6.6% of all patients who underwent SPS, compared with 7.3% of those who underwent APR. Distant metastases occurred in 22.5% and 24.4%, respectively.

“Holding surgical decision-making until after completion of neoadjuvant therapy allows for increased sphincter preservation with good oncologic outcomes in rectal cancer patients,” the investigators concluded.

FROM SSO 2016

Key clinical point: Waiting 8-12 weeks following neoadjuvant chemoradiation in patients with T3 distal rectal cancers improves chances for sphincter preservation.

Major finding: The 5-year stoma-free survival rate was 79% in patients initially considered candidates for APR and colostomy.

Data source: Retrospective review of 192 patients in a prospectively maintained database.

Disclosures: The study was internally supported. Dr. Myers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Elective CRC resections increase with universal insurance

BOSTON – Expanding access to health insurance for low- and moderate-income families has apparently improved colorectal cancer care in Massachusetts, and may do the same for other states that participate in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

That assertion comes from investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. They found that following the introduction in 2006 of a universal health insurance law in the Bay State – the law that would serve as a model for the Affordable Care Act – the rate of elective colorectal resections increased while the rate of emergent resections decreased.

In contrast, in three states used as controls, the opposite occurred.

“This could be due to a variety of different factors, including earlier diagnosis, presenting with disease more amenable to surgical resection. It could also be due to increased referrals from primary care providers or GI doctors,” said Dr. Andrew P. Loehrer from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery, at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

He acknowledged, however, that the administrative dataset he and his colleagues used in the study lacks information about clinical staging or use of neoadjuvant therapy, making it difficult to determine whether insured patients actually present at an earlier, more readily treatable disease stage.

Nonetheless, “from a cancer standpoint, my study provides early, hopeful evidence. In order to definitively say that this improves care, we need to have some more of the cancer-specific variables, but with this study, combined with some other work that we and other groups have done, we see that patients in Massachusetts are presenting with earlier stage disease, whether it’s acute disease or cancer, and they’re getting more appropriate care in a more timely fashion,” he said in an interview.

Role model

Dr. Loehrer noted that disparities in access to health care have been shown in previous studies to be associated with the likelihood of unfavorable outcomes for patients with colorectal cancer. For example, a 2008 study (Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9:222-31) showed that uninsured patients with colorectal cancer had a twofold greater risk for presenting with advanced disease than privately insured patients. Additionally, a 2004 study (Br J Surg. 91:605-9) showed that patients who presented with colorectal cancer requiring emergent resection had significantly lower 5-year overall survival than patients who underwent elective resection.

Massachusetts implemented its pioneering health insurance reform law in 2006. The law increased eligibility for persons with incomes up to 150% of the Federal Poverty Level, created government-subsidized insurance for those with incomes from 150% to 300% of the poverty line, mandated that all Bay State residents have some form of health insurance, and allowed young adults up to the age of 26 to remain on their parents’ plans.

To see whether insurance reform could have a salutary effect on cancer care, the investigators drew on Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) State Inpatient Databases for Massachusetts and for Florida, New Jersey, and New York as control states. They used ICD-9 diagnosis codes to identify patients with colorectal cancer, including those who underwent resection.

To establish procedure rates, they used U.S. Census Bureau data to establish the population of denominators, which included all adults 18-54 years of age who were insured either through Medicaid, Commonwealth Care (in Massachusetts), or were listed as uninsured or self-pay. Medicare-insured patients were not included, as they were not directly affected by the reform law.

They identified 18,598 patients admitted to Massachusetts hospitals for colorectal cancer from 2001 through 2011, and 147,482 admitted during the same period to hospitals in the control states.

The authors created Poisson difference-in-differences models which compare changes in the selected outcomes in Massachusetts with changes in the control states. The models were adjusted for age, sex, race, hospital type, and secular trends.

They found that admission rates for colorectal cancer increased over time in Massachusetts by 13.3 per 100,000 residents per quarter, compared with 8.3/100,000 in the control states, translating into an adjusted rate ratio (ARR) of 1.13. Resection rates for cancer, the primary study outcome, also grew by a significantly larger margin in Massachusetts, by 5.5/100,000, compared with 0.5/100,000 in control states, with an ARR of 1.37 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

For the secondary outcome of changes in emergent and elective resections after admission, they found that emergent surgeries in Massachusetts declined by 2.7/100,000, but increased by 4.4/100,000 in the states without insurance reform. Similarly, elective resections after admission increased in the Bay State by 7.4/100,000, but decreased by 1.8/100,000 in control states.

Relative to controls, the adjusted probability that a patient with colorectal cancer in Massachusetts would have emergent surgery after admission declined by 6.1% (P = .014) and the probability that he or she would have elective resection increased by 7.8% (P = .005).

An analysis of the odds ratio of resection during admission, adjusted for age, race, presentation with metastatic disease, hospital type, and secular trends, showed that prior to reform uninsured patients in both Massachusetts and control states were significantly less likely than privately insured patients to have resections (odds ratio, 0.42 in Mass.; 0.45 in control states).

However, after the implementation of reform the gap between previously uninsured and privately insured in Massachusetts narrowed (OR, 0.63) but remained the same in control states (OR, 0.44).

Dr. Loehrer acknowledged in an interview that Massachusetts differs from other states in some regards, including in concentrations of health providers and in requirements for insurance coverage that were in place even before the 2006 reforms, but is optimistic that improvements in colorectal cancer care can occur in states that have embraced the Affordable Care Act.

“There are a lot of services that were available and we had high colonoscopy rates prior to all of this, but that said, the mechanism is exactly the same, there are still vulnerable populations, and at this point I think it’s hopeful and promising that we will see similar results in other states,” he said.

BOSTON – Expanding access to health insurance for low- and moderate-income families has apparently improved colorectal cancer care in Massachusetts, and may do the same for other states that participate in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

That assertion comes from investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. They found that following the introduction in 2006 of a universal health insurance law in the Bay State – the law that would serve as a model for the Affordable Care Act – the rate of elective colorectal resections increased while the rate of emergent resections decreased.

In contrast, in three states used as controls, the opposite occurred.

“This could be due to a variety of different factors, including earlier diagnosis, presenting with disease more amenable to surgical resection. It could also be due to increased referrals from primary care providers or GI doctors,” said Dr. Andrew P. Loehrer from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery, at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

He acknowledged, however, that the administrative dataset he and his colleagues used in the study lacks information about clinical staging or use of neoadjuvant therapy, making it difficult to determine whether insured patients actually present at an earlier, more readily treatable disease stage.

Nonetheless, “from a cancer standpoint, my study provides early, hopeful evidence. In order to definitively say that this improves care, we need to have some more of the cancer-specific variables, but with this study, combined with some other work that we and other groups have done, we see that patients in Massachusetts are presenting with earlier stage disease, whether it’s acute disease or cancer, and they’re getting more appropriate care in a more timely fashion,” he said in an interview.

Role model

Dr. Loehrer noted that disparities in access to health care have been shown in previous studies to be associated with the likelihood of unfavorable outcomes for patients with colorectal cancer. For example, a 2008 study (Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9:222-31) showed that uninsured patients with colorectal cancer had a twofold greater risk for presenting with advanced disease than privately insured patients. Additionally, a 2004 study (Br J Surg. 91:605-9) showed that patients who presented with colorectal cancer requiring emergent resection had significantly lower 5-year overall survival than patients who underwent elective resection.

Massachusetts implemented its pioneering health insurance reform law in 2006. The law increased eligibility for persons with incomes up to 150% of the Federal Poverty Level, created government-subsidized insurance for those with incomes from 150% to 300% of the poverty line, mandated that all Bay State residents have some form of health insurance, and allowed young adults up to the age of 26 to remain on their parents’ plans.

To see whether insurance reform could have a salutary effect on cancer care, the investigators drew on Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) State Inpatient Databases for Massachusetts and for Florida, New Jersey, and New York as control states. They used ICD-9 diagnosis codes to identify patients with colorectal cancer, including those who underwent resection.

To establish procedure rates, they used U.S. Census Bureau data to establish the population of denominators, which included all adults 18-54 years of age who were insured either through Medicaid, Commonwealth Care (in Massachusetts), or were listed as uninsured or self-pay. Medicare-insured patients were not included, as they were not directly affected by the reform law.

They identified 18,598 patients admitted to Massachusetts hospitals for colorectal cancer from 2001 through 2011, and 147,482 admitted during the same period to hospitals in the control states.

The authors created Poisson difference-in-differences models which compare changes in the selected outcomes in Massachusetts with changes in the control states. The models were adjusted for age, sex, race, hospital type, and secular trends.

They found that admission rates for colorectal cancer increased over time in Massachusetts by 13.3 per 100,000 residents per quarter, compared with 8.3/100,000 in the control states, translating into an adjusted rate ratio (ARR) of 1.13. Resection rates for cancer, the primary study outcome, also grew by a significantly larger margin in Massachusetts, by 5.5/100,000, compared with 0.5/100,000 in control states, with an ARR of 1.37 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

For the secondary outcome of changes in emergent and elective resections after admission, they found that emergent surgeries in Massachusetts declined by 2.7/100,000, but increased by 4.4/100,000 in the states without insurance reform. Similarly, elective resections after admission increased in the Bay State by 7.4/100,000, but decreased by 1.8/100,000 in control states.

Relative to controls, the adjusted probability that a patient with colorectal cancer in Massachusetts would have emergent surgery after admission declined by 6.1% (P = .014) and the probability that he or she would have elective resection increased by 7.8% (P = .005).

An analysis of the odds ratio of resection during admission, adjusted for age, race, presentation with metastatic disease, hospital type, and secular trends, showed that prior to reform uninsured patients in both Massachusetts and control states were significantly less likely than privately insured patients to have resections (odds ratio, 0.42 in Mass.; 0.45 in control states).

However, after the implementation of reform the gap between previously uninsured and privately insured in Massachusetts narrowed (OR, 0.63) but remained the same in control states (OR, 0.44).

Dr. Loehrer acknowledged in an interview that Massachusetts differs from other states in some regards, including in concentrations of health providers and in requirements for insurance coverage that were in place even before the 2006 reforms, but is optimistic that improvements in colorectal cancer care can occur in states that have embraced the Affordable Care Act.

“There are a lot of services that were available and we had high colonoscopy rates prior to all of this, but that said, the mechanism is exactly the same, there are still vulnerable populations, and at this point I think it’s hopeful and promising that we will see similar results in other states,” he said.

BOSTON – Expanding access to health insurance for low- and moderate-income families has apparently improved colorectal cancer care in Massachusetts, and may do the same for other states that participate in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

That assertion comes from investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. They found that following the introduction in 2006 of a universal health insurance law in the Bay State – the law that would serve as a model for the Affordable Care Act – the rate of elective colorectal resections increased while the rate of emergent resections decreased.

In contrast, in three states used as controls, the opposite occurred.

“This could be due to a variety of different factors, including earlier diagnosis, presenting with disease more amenable to surgical resection. It could also be due to increased referrals from primary care providers or GI doctors,” said Dr. Andrew P. Loehrer from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery, at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

He acknowledged, however, that the administrative dataset he and his colleagues used in the study lacks information about clinical staging or use of neoadjuvant therapy, making it difficult to determine whether insured patients actually present at an earlier, more readily treatable disease stage.

Nonetheless, “from a cancer standpoint, my study provides early, hopeful evidence. In order to definitively say that this improves care, we need to have some more of the cancer-specific variables, but with this study, combined with some other work that we and other groups have done, we see that patients in Massachusetts are presenting with earlier stage disease, whether it’s acute disease or cancer, and they’re getting more appropriate care in a more timely fashion,” he said in an interview.

Role model

Dr. Loehrer noted that disparities in access to health care have been shown in previous studies to be associated with the likelihood of unfavorable outcomes for patients with colorectal cancer. For example, a 2008 study (Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9:222-31) showed that uninsured patients with colorectal cancer had a twofold greater risk for presenting with advanced disease than privately insured patients. Additionally, a 2004 study (Br J Surg. 91:605-9) showed that patients who presented with colorectal cancer requiring emergent resection had significantly lower 5-year overall survival than patients who underwent elective resection.

Massachusetts implemented its pioneering health insurance reform law in 2006. The law increased eligibility for persons with incomes up to 150% of the Federal Poverty Level, created government-subsidized insurance for those with incomes from 150% to 300% of the poverty line, mandated that all Bay State residents have some form of health insurance, and allowed young adults up to the age of 26 to remain on their parents’ plans.

To see whether insurance reform could have a salutary effect on cancer care, the investigators drew on Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) State Inpatient Databases for Massachusetts and for Florida, New Jersey, and New York as control states. They used ICD-9 diagnosis codes to identify patients with colorectal cancer, including those who underwent resection.

To establish procedure rates, they used U.S. Census Bureau data to establish the population of denominators, which included all adults 18-54 years of age who were insured either through Medicaid, Commonwealth Care (in Massachusetts), or were listed as uninsured or self-pay. Medicare-insured patients were not included, as they were not directly affected by the reform law.

They identified 18,598 patients admitted to Massachusetts hospitals for colorectal cancer from 2001 through 2011, and 147,482 admitted during the same period to hospitals in the control states.

The authors created Poisson difference-in-differences models which compare changes in the selected outcomes in Massachusetts with changes in the control states. The models were adjusted for age, sex, race, hospital type, and secular trends.

They found that admission rates for colorectal cancer increased over time in Massachusetts by 13.3 per 100,000 residents per quarter, compared with 8.3/100,000 in the control states, translating into an adjusted rate ratio (ARR) of 1.13. Resection rates for cancer, the primary study outcome, also grew by a significantly larger margin in Massachusetts, by 5.5/100,000, compared with 0.5/100,000 in control states, with an ARR of 1.37 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

For the secondary outcome of changes in emergent and elective resections after admission, they found that emergent surgeries in Massachusetts declined by 2.7/100,000, but increased by 4.4/100,000 in the states without insurance reform. Similarly, elective resections after admission increased in the Bay State by 7.4/100,000, but decreased by 1.8/100,000 in control states.

Relative to controls, the adjusted probability that a patient with colorectal cancer in Massachusetts would have emergent surgery after admission declined by 6.1% (P = .014) and the probability that he or she would have elective resection increased by 7.8% (P = .005).

An analysis of the odds ratio of resection during admission, adjusted for age, race, presentation with metastatic disease, hospital type, and secular trends, showed that prior to reform uninsured patients in both Massachusetts and control states were significantly less likely than privately insured patients to have resections (odds ratio, 0.42 in Mass.; 0.45 in control states).

However, after the implementation of reform the gap between previously uninsured and privately insured in Massachusetts narrowed (OR, 0.63) but remained the same in control states (OR, 0.44).

Dr. Loehrer acknowledged in an interview that Massachusetts differs from other states in some regards, including in concentrations of health providers and in requirements for insurance coverage that were in place even before the 2006 reforms, but is optimistic that improvements in colorectal cancer care can occur in states that have embraced the Affordable Care Act.

“There are a lot of services that were available and we had high colonoscopy rates prior to all of this, but that said, the mechanism is exactly the same, there are still vulnerable populations, and at this point I think it’s hopeful and promising that we will see similar results in other states,” he said.

FROM SSO 2016

Key clinical point: Outcomes for patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) who undergo elective resection are better than for those who require emergent resections.

Major finding: Elective CRC resection rates increased and emergent resections decreased after universal insurance was instituted in Massachusetts in 2006.

Data source: Retrospective study comparing differences over time between CRC resection rates in Massachusetts vs. those in Florida, New Jersey, and New York.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Loehrer and his coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.