User login

Fibromuscular Dysplasia Often Misdiagnosed in Children

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Fibromuscular Dysplasia Often Misdiagnosed in Children

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke differs from the disease in adults and from clinically diagnosed fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke.

Data Source: A review of data from 81 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries or gleaned from the medical literature.

Disclosures: Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Fibromuscular Dysplasia Often Misdiagnosed in Children

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence from a preliminary study suggests that the arteriopathy called fibromuscular dysplasia appears differently in children than in adults.

In fact, what most neurologists diagnose as fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke might not be fibromuscular dysplasia at all, but is more likely to be transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) of childhood, Dr. Adam Kirton said at the conference.

Little is know about the causes of arteriopathy, the most common cause of childhood arterial ischemic stroke. One cause is fibromuscular dysplasia, a group of idiopathic, noninflammatory arteriopathies that classically involve cerebral and renal vessels in whites.

"There’s never been a systematic look at the role of fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke," said Dr. Kirton, director of the pediatric stroke program at Alberta (Calgary) Children’s Hospital. He and his associates analyzed data from 81 cases of childhood stroke that had references to fibromuscular dysplasia or renal artery disease.

Of the 15 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries and 66 cases gleaned from the medical literature, 27 had pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia, 31 were clinically diagnosed, and the remaining 23 cases were grouped as "other" diagnoses.

The records provided sufficient detail on 19 of the 27 pathologically proven cases to show that 17 of the 19 (89%) were classified as intimal fibroplasia, a type that is rarely seen in adults. Angiography of these patients showed nonspecific findings such as focal narrowing or stenosis, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

The other 2 of the 19 cases were classified as medial hyperplasia, and the remaining 8 cases could not be classified. Notably, none of the 19 had medial fibroplasia or dysplasia, the type typically seen in adults with stroke. "This is the one you learn about in medical school" that has a unique "string of beads" appearance on angiography, he said.

Conventional angiography was performed in 26 of 27 children with pathologically-proven fibromuscular dysplasia. Only 5 (20%) showed a "string of beads" appearance, compared with more than half of the clinically diagnosed group, a significant difference. The pathologically-proven group, however, had significantly higher rates of the moyamoya intake pattern and of renal artery stenosis or renal hypertension than did the clinically diagnosed group.

Of 21 children in the pathologically-proven group who underwent systemic evaluations, 16 (76%) had evidence of systemic arteriopathy outside of the brain and kidneys, "supporting the idea that a lot of fibromuscular dysplasia is really a systemic arterial disease in children," Dr. Kirton said.

There was no evidence of the female predominance for fibromuscular dysplasia that has been observed in adult cases. Nine children in the pathologically-proven group (33%) first presented with neurological symptoms in the first year of life, compared with only three children in the clinically diagnosed group (10%).

Children in the pathologically proven group were significantly more likely to have poor outcomes, to have disease recurrence, and to die, compared with the clinically diagnosed group.

Among 23 patients with pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia who were followed for an average of 43 months, 15 had poor outcomes (65%), 8 had recurrences (35%) and 10 died (43%). "There’s a selection bias here, because some of these children died before they could get to pathology," Dr. Kirton noted.

Among 30 children in the clinically diagnosed group who were followed for an average of 22 months, 10 had poor outcomes (33%), 2 had recurrences (7%) and 1 died (3%).

The clinically diagnosed cases more closely resembled TCA than fibromuscular dysplasia, he suggested. The former were more likely to be previously healthy patients with unilateral disease that had a "string of beads" appearance, less likely to have renal artery stenosis or hypertension, and less likely to develop recurrence.

"We are not able to accurately diagnose fibromuscular dysplasia clinically," Dr. Kirton said. "If you see a ‘string of beads,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean fibromuscular dysplasia. In fact, our data would argue that it suggests something else."

Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Pathologically proven fibromuscular dysplasia in children with arterial ischemic stroke differs from the disease in adults and from clinically diagnosed fibromuscular dysplasia in childhood stroke.

Data Source: A review of data from 81 cases obtained from two large Canadian registries or gleaned from the medical literature.

Disclosures: Dr. Kirton said the investigators have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Childhood Stroke Prognosis May Be Better Than Thought

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Full recovery 1 year after arterial ischemic stroke was seen in 32 of 69 children (46%), a higher rate than reported in previous studies.

Data Source: 1-year outcomes of 69 cases of childhood arterial ischemic stroke in a prospective, population-based study, compared with previous studies of hospital-based cohorts.

Disclosures: Dr. Mallick said the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

Childhood Stroke Prognosis May Be Better Than Thought

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Childhood Stroke Prognosis May Be Better Than Thought

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

LOS ANGELES – A large population-based study found better outcomes a year after childhood arterial ischemic stroke than were reported in previous studies that analyzed hospital-based cohorts.

The prospective Study of Outcome in Childhood Stroke (SOCS) followed cases of arterial ischemic stroke in children older than 27 days and younger than 16 years that were identified by British networks of medical specialists and surveillance databases from July 2008 through June 2009. The data collected cover 6 million children – 63% of children in England.

They found 82 cases of arterial ischemic stroke, for an incidence of 1.4/100,000 children per year, Dr. Andrew A. Mallick reported. Consent for follow-up assessments in the study was not available for seven patients, and six died (though none died primarily of stroke).

The parents of the remaining 69 children completed the International Pediatric Stroke Study Recovery and Recurrence Questionnaire. Their answers suggested that 32 (46%) children had fully recovered from the stroke and that 46 (67%) needed no extra help in daily activities.

Physician assessments using the Pediatric Stroke Outcome Measure suggested that 45% of the children were normal with no stroke-related deficits a year later. In the rest, physicians rated the severity of deficits as mild in 10% of children, moderate in 20%, and severe in 25%, said Dr. Mallick of the University of Bristol (England).

The percentages of children in the SOCS rated as fully recovered by parents and physicians compares favorably with the largest and most-often cited previous studies of outcome after childhood stroke, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Those studies reported normal function after arterial ischemic stroke in 32% and 13% of children (J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:316-24; Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000;42:455-61).

The previous studies followed patients from tertiary care children’s hospitals in Canada and England. Hospital-based registries generally include patients with more severe strokes who are at a higher risk of complications or death, he said.

The SOCS findings should affect prognosis after childhood arterial ischemic stroke and the design of clinical trials, Dr. Mallick said.

"We’ve seen from our data that almost half the children are prepared to make a full recovery. If some of the proposed therapies are relatively high risk, I think we need to carefully consider whether we want to be giving children who are going to recover anyway such potentially dangerous therapies," he said.

When neurologic deficits were seen in the SOCS, about half were sensorimotor deficits, approximately a quarter were cognition or behavioral deficits, and fewer were deficits in expressive or receptive speech, Dr. Mallick and his associates found.

He said he and his coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Full recovery 1 year after arterial ischemic stroke was seen in 32 of 69 children (46%), a higher rate than reported in previous studies.

Data Source: 1-year outcomes of 69 cases of childhood arterial ischemic stroke in a prospective, population-based study, compared with previous studies of hospital-based cohorts.

Disclosures: Dr. Mallick said the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. The Stroke Association (United Kingdom) funded the study.

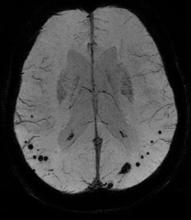

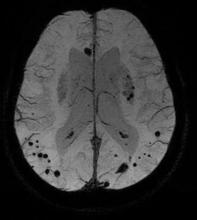

Cerebral Microbleeds Common in Elderly

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.