User login

Data Trends 2024: Diabetes

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

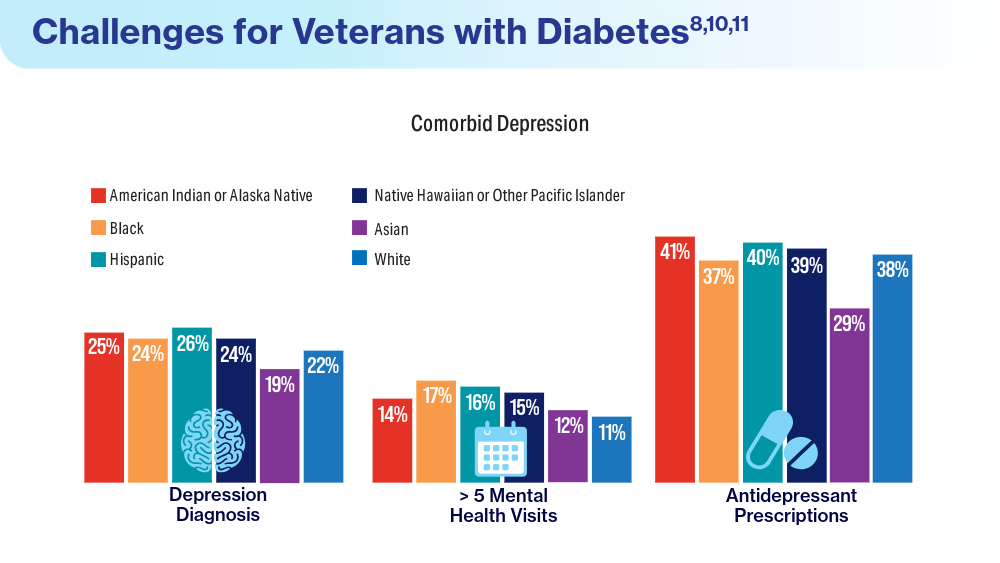

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al; for the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

- Utech A. VA supports veterans who have type 2 diabetes. VA News. August 18, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://news.va.gov/107579/va-supportsveterans-who-have-type-2-diabetes/

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Shanmugam R, Kruse CS, Fulton LV. Obesity and morbidity risk in the U.S. veteran. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):191. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030191

- Briskin A. Obesity and diabetes: causes, treatments, and stigma. diaTribe. October 4, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://diatribe.org/obesity-and-diabetescauses-

treatments-and-stigma - Leonard C, Sayre G, Williams S, et al. Understanding the experience of veterans who require lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration. PLOS One. 2022;17(3):e0265620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265620

- Armstrong DG. Diabetic foot ulcers: a silent killer of veterans. Stat News. November 11, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/11/diabetic-foot-ulcers-veterans-silent-killer/

- Koleda EW. The veteran diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) epidemic: a U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) services review. TreatNOW. October 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://treatnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-VA-Diabetic-Foot-Ulcer-Epidemic-10-14-22.pdf

- CDC identifies diabetes belt. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Updated June 7, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

- Avramovic S, Alemi F, Kanchi R, et al. US Veterans Administration diabetes risk (VADR) national cohort: cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e039489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039489

- Breland JY, Tseng CH, Toyama J, Washington DL. Influence of depression on racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes control. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11(6):e003612. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003612

As CGM Benefit Data Accrue, Primary Care Use Expands

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — As increasing data show benefit for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices beyond just insulin-treated diabetes, efforts are being made to optimize the use of CGM in primary care settings.

Currently, Medicare and most private insurers cover CGM for people with diabetes who use insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes or the type of insulin, and for those with a history of severe hypoglycemia. Data are increasingly showing benefit for people who don’t use insulin. As of now, with the exception of some state Medicaid beneficiaries, the majority must pay out of pocket.

Such use is expected to grow with the upcoming availability of two new over-the-counter CGMs, Dexcom’s Stelo and Abbott’s Libre Rio, both made for people with diabetes who don’t use insulin. (Abbott will also launch the Lingo, a wellness CGM for people without diabetes.)

This means that CGM will become increasingly prevalent in primary care, where there is currently a great deal of variability in the capacity to manage and use the data generated by the devices to improve diabetes management, experts said during an oral abstract session at the recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) 84th Scientific Sessions and in interviews with this news organization.

“It’s picking up steam, and there’s a lot more visibility of CGM in primary care and a lot more people prescribing it,” Thomas W. Martens, MD, medical director of the International Diabetes Center at HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, told this news organization. He noted that the recent switch in many cases of CGM from billing as durable medical equipment to pharmacy has made prescribing easier, while television advertising has increased demand.

But still unclear, he noted, is how the CGM data are being used. “The question is, are prescriptions just being sent out and people using it like a finger-stick blood glucose monitor, or is primary care really using the data to move diabetes forward? I think that’s where a lot of the work on dissemination and implementation is going. How do we really make this a useful tool for optimizing diabetes care?”

Informing Food Choice, Treatment Intensification

At the ADA meeting, Dr. Martens presented topline data from a randomized multicenter controlled trial funded by Abbott, examining the effect of CGM use on guiding food choices and other behaviors in 72 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not using insulin but who were using other glucose-lowering medications.

At 3 months, with no medication changes, there was a significant overall 26% reduction in time spent above 180 mg/dL (P < .0001), which didn›t differ significantly between those randomized to CGM alone or in conjunction with a food logging app. Both groups also experienced a significant 1.1% reduction in A1c (P < .0001) and about a 4-lb weight loss (P = .014 for CGM alone, P = .0032 for CGM + app).

“The win for people not on insulin is you can see the impact of food choices really quickly with a CGM ... and then perhaps modify that to improve postprandial hyperglycemia,” Dr. Martens said.

And for the clinician, “not everybody with type 2 diabetes not on insulin can get where they need to be just by changing their diets. The CGM is a pretty good tool for knowing when you need to advance therapy.”

Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) Assist CGM Use

Another speaker at the ADA meeting, Sean M. Oser, MD, director of the Practice Innovation Program and associated director of the Primary Care Diabetes Lab at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, noted that 90% of adults with type 2 diabetes and 50% with type 1 diabetes receive their diabetes care in primary care settings.

“CGM is increasingly becoming standard of care in diabetes ... But [primary care providers] remain relatively untrained about CGM ... What I’m concerned about is the disparity disparities in who has access and who does not. We really need to bring our primary care colleagues along,” he said.

Dr. Oser described tools he and his wife, Tamara K. Oser, MD, professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the same institution, developed in conjunction with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), including the Transformation in Practice series (TIPS).

The PREPARE 4 CGM study examined the use of three different strategies for incorporating CGM into primary care settings: Either use of AAFP TIPS alone, TIPS plus practice facilitation services by coaches who assist the practice in implementing new workflows, or referral to a virtual CGM initiation service (virCIS) with a virtual CGM workshop that Dr. Oser and Dr. Oser also developed.

Of the 76 Colorado primary care practices participating (out of 60 planned), the 46 who chose AAFP TIPS were randomized to either the AAFP TIPS alone or to TIPS + practice facilitation. The other 30 chose virCIS with the onetime CGM basics webinar. The fact that more practices than anticipated were recruited for the study suggests that “primary care interest in CGM is very high. They want to learn,” Dr. Oser noted.

Of the 51 practice characteristics investigated, only one, the presence of a DCES, in the practice, was significantly associated with the choice of CGM implementation strategy. Of the 16 practices with access to a DCES, all of them chose self-initiation with CGM using TIPS. But of the 60 practices without a DCES, half chose the virCIS.

“We know that 36% of primary care practices have access to a DCES within the clinic, part-time or full-time, and that’s not enough, I would argue,” Dr. Oser said.

Indeed, Dr. Martens told this news organization that those professionals, formerly called “diabetes educators,” often aren’t available in primary care settings, especially in rural areas. “Unfortunately, they are not well reimbursed. A lot of care systems don’t employ as many as they ideally should because it tends not to be a moneymaker ... Something’s got to change with reimbursement for the cognitive aspects of diabetes management.”

Dr. Oser said his team’s next steps include completion of the virCIS operations, analysis of the effectiveness of the three implantation strategies in practice- and patient-level outcomes, a cost analysis of the three strategies, and further development of toolkits to assist in these efforts.

“One of our goals is to keep people at their primary care home, where they want to be ... Diabetes knows no borders. People should have access wherever they are,” Dr. Oser concluded in his ADA talk.

What Predicts Primary Care CGM Prescribing?

Further clues about effective strategies to improve CGM prescribing in primary care were provided in a study presented by Jovan Milosavljevic, MD, a second-year endocrinology fellow at the Fleischer Institute for Diabetes and Metabolism, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

He began by noting that there are currently 61.5 million diabetes visits annually in primary care compared with 32.0 million in specialty care and that there is a shortage of endocrinologists in the face of the rising number of people diagnosed with diabetes. “Primary care will continue to be the only point of care for most people with diabetes. So, standard-of-care treatment such as CGM must enter routine primary care practice to impact population-level health outcomes.”

Electronic health record data were examined for 39,710 patients with type 2 diabetes seen at 13 primary care sites affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center, a large safety net hospital in New York, where CGM is widely covered by public insurance. Between July 31, 2020, and July 31, 2023, a total of 3503, or just 8.8%, were prescribed CGM by a primary care provider.

Those with CGM prescribed were younger than those without (59.7 vs 62.7 years), about 40% of both groups were Hispanic or Black, and a majority were English-speaking: 84.5% of those prescribed CGM spoke English, while only 13.1% spoke Spanish. Over half (59.1%) of those prescribed CGM had commercial insurance, while only 11.2% had Medicaid and 29.7% had Medicare.

More patients with CGM prescribed had providers with more than 10 years in practice: 72.5% vs 64.5% with no CGM.

Not surprisingly, those with CGM prescribed were more likely on insulin — 21% using just basal and 35% on multiple daily injections. Those prescribed CGM had higher A1c levels before CGM prescription: 9.2% vs 7.2% for those not prescribed CGM.

No racial or ethnic bias was found in the relationships between CGM use and insulin use, provider experience, engagement with care, and A1c. However, there were differences by age, sex, and spoken language.

For example, the Hispanic group aged 65 years and older was less likely than those younger to be prescribed CGM, but this wasn’t seen in other ethnic groups. In fact, older White people were slightly more likely to have CGM prescribed. Spanish-speaking patients were about 43% less likely to have CGM prescribed than were English-speaking patients.

These findings suggest a dual approach might work best for improving CGM prescribing in primary care. “We can leverage the knowledge that some of these factors are independent of bias and promote clinical and evidence-based guidelines for CGM. Additionally, we should focus on physicians in training,” Dr. Milosavljevic said.

At the same time, “we need to tackle systemic inequity in prescription processes,” with measures such as improving prescription workflows, supporting prior authorization, and using patient hands-on support for older adults and Spanish-speaking individuals, he said.

In a message to this news organization, Tamara K. Oser, MD, wrote, “Disparities in CGM and other diabetes technology are prevalent and multifactorial. In addition to insurance barriers, implicit bias also plays a large role. Shared decision-making should always be used when deciding to prescribe diabetes technologies.”

The PREPARE 4 CGM study is evaluating willingness to pay for CGM, she noted.

“Even patients without insurance might want to purchase one sensor every few months to empower them to learn more about how food and exercise affect their glucose or to help assess the need for [adjusting] diabetes medications. It is an exciting time for people living with diabetes. Primary care, endocrinology, device manufacturers, and insurers should all do their part to assure increased access to these evidence-based technologies.”

Dr. Martens’ employer has received funds on his behalf for research and speaking support from Dexcom, Abbott Diabetes Care, Medtronic, Insulet, Tandem, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novo Nordisk, and for consulting from Sanofi and Eli Lilly and Company. He is employed by the nonprofit HealthPartners Institute dba International Diabetes Center and received no personal income from these activities.

The Osers have received advisory board consulting fees (through the University of Colorado) from Dexcom, Medscape Medical News, Ascensia, and Blue Circle Health and research grants (through the University of Colorado) from National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, Abbott Diabetes, Dexcom, and Insulet. They do not own stocks in any device or pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Milosavljevic’s work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science and Einstein-Montefiore Clinical and Translational Science Awards. He had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — As increasing data show benefit for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices beyond just insulin-treated diabetes, efforts are being made to optimize the use of CGM in primary care settings.

Currently, Medicare and most private insurers cover CGM for people with diabetes who use insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes or the type of insulin, and for those with a history of severe hypoglycemia. Data are increasingly showing benefit for people who don’t use insulin. As of now, with the exception of some state Medicaid beneficiaries, the majority must pay out of pocket.

Such use is expected to grow with the upcoming availability of two new over-the-counter CGMs, Dexcom’s Stelo and Abbott’s Libre Rio, both made for people with diabetes who don’t use insulin. (Abbott will also launch the Lingo, a wellness CGM for people without diabetes.)

This means that CGM will become increasingly prevalent in primary care, where there is currently a great deal of variability in the capacity to manage and use the data generated by the devices to improve diabetes management, experts said during an oral abstract session at the recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) 84th Scientific Sessions and in interviews with this news organization.

“It’s picking up steam, and there’s a lot more visibility of CGM in primary care and a lot more people prescribing it,” Thomas W. Martens, MD, medical director of the International Diabetes Center at HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, told this news organization. He noted that the recent switch in many cases of CGM from billing as durable medical equipment to pharmacy has made prescribing easier, while television advertising has increased demand.

But still unclear, he noted, is how the CGM data are being used. “The question is, are prescriptions just being sent out and people using it like a finger-stick blood glucose monitor, or is primary care really using the data to move diabetes forward? I think that’s where a lot of the work on dissemination and implementation is going. How do we really make this a useful tool for optimizing diabetes care?”

Informing Food Choice, Treatment Intensification

At the ADA meeting, Dr. Martens presented topline data from a randomized multicenter controlled trial funded by Abbott, examining the effect of CGM use on guiding food choices and other behaviors in 72 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not using insulin but who were using other glucose-lowering medications.

At 3 months, with no medication changes, there was a significant overall 26% reduction in time spent above 180 mg/dL (P < .0001), which didn›t differ significantly between those randomized to CGM alone or in conjunction with a food logging app. Both groups also experienced a significant 1.1% reduction in A1c (P < .0001) and about a 4-lb weight loss (P = .014 for CGM alone, P = .0032 for CGM + app).

“The win for people not on insulin is you can see the impact of food choices really quickly with a CGM ... and then perhaps modify that to improve postprandial hyperglycemia,” Dr. Martens said.

And for the clinician, “not everybody with type 2 diabetes not on insulin can get where they need to be just by changing their diets. The CGM is a pretty good tool for knowing when you need to advance therapy.”

Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) Assist CGM Use

Another speaker at the ADA meeting, Sean M. Oser, MD, director of the Practice Innovation Program and associated director of the Primary Care Diabetes Lab at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, noted that 90% of adults with type 2 diabetes and 50% with type 1 diabetes receive their diabetes care in primary care settings.

“CGM is increasingly becoming standard of care in diabetes ... But [primary care providers] remain relatively untrained about CGM ... What I’m concerned about is the disparity disparities in who has access and who does not. We really need to bring our primary care colleagues along,” he said.

Dr. Oser described tools he and his wife, Tamara K. Oser, MD, professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the same institution, developed in conjunction with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), including the Transformation in Practice series (TIPS).

The PREPARE 4 CGM study examined the use of three different strategies for incorporating CGM into primary care settings: Either use of AAFP TIPS alone, TIPS plus practice facilitation services by coaches who assist the practice in implementing new workflows, or referral to a virtual CGM initiation service (virCIS) with a virtual CGM workshop that Dr. Oser and Dr. Oser also developed.

Of the 76 Colorado primary care practices participating (out of 60 planned), the 46 who chose AAFP TIPS were randomized to either the AAFP TIPS alone or to TIPS + practice facilitation. The other 30 chose virCIS with the onetime CGM basics webinar. The fact that more practices than anticipated were recruited for the study suggests that “primary care interest in CGM is very high. They want to learn,” Dr. Oser noted.

Of the 51 practice characteristics investigated, only one, the presence of a DCES, in the practice, was significantly associated with the choice of CGM implementation strategy. Of the 16 practices with access to a DCES, all of them chose self-initiation with CGM using TIPS. But of the 60 practices without a DCES, half chose the virCIS.

“We know that 36% of primary care practices have access to a DCES within the clinic, part-time or full-time, and that’s not enough, I would argue,” Dr. Oser said.

Indeed, Dr. Martens told this news organization that those professionals, formerly called “diabetes educators,” often aren’t available in primary care settings, especially in rural areas. “Unfortunately, they are not well reimbursed. A lot of care systems don’t employ as many as they ideally should because it tends not to be a moneymaker ... Something’s got to change with reimbursement for the cognitive aspects of diabetes management.”

Dr. Oser said his team’s next steps include completion of the virCIS operations, analysis of the effectiveness of the three implantation strategies in practice- and patient-level outcomes, a cost analysis of the three strategies, and further development of toolkits to assist in these efforts.

“One of our goals is to keep people at their primary care home, where they want to be ... Diabetes knows no borders. People should have access wherever they are,” Dr. Oser concluded in his ADA talk.

What Predicts Primary Care CGM Prescribing?

Further clues about effective strategies to improve CGM prescribing in primary care were provided in a study presented by Jovan Milosavljevic, MD, a second-year endocrinology fellow at the Fleischer Institute for Diabetes and Metabolism, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

He began by noting that there are currently 61.5 million diabetes visits annually in primary care compared with 32.0 million in specialty care and that there is a shortage of endocrinologists in the face of the rising number of people diagnosed with diabetes. “Primary care will continue to be the only point of care for most people with diabetes. So, standard-of-care treatment such as CGM must enter routine primary care practice to impact population-level health outcomes.”

Electronic health record data were examined for 39,710 patients with type 2 diabetes seen at 13 primary care sites affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center, a large safety net hospital in New York, where CGM is widely covered by public insurance. Between July 31, 2020, and July 31, 2023, a total of 3503, or just 8.8%, were prescribed CGM by a primary care provider.

Those with CGM prescribed were younger than those without (59.7 vs 62.7 years), about 40% of both groups were Hispanic or Black, and a majority were English-speaking: 84.5% of those prescribed CGM spoke English, while only 13.1% spoke Spanish. Over half (59.1%) of those prescribed CGM had commercial insurance, while only 11.2% had Medicaid and 29.7% had Medicare.

More patients with CGM prescribed had providers with more than 10 years in practice: 72.5% vs 64.5% with no CGM.

Not surprisingly, those with CGM prescribed were more likely on insulin — 21% using just basal and 35% on multiple daily injections. Those prescribed CGM had higher A1c levels before CGM prescription: 9.2% vs 7.2% for those not prescribed CGM.

No racial or ethnic bias was found in the relationships between CGM use and insulin use, provider experience, engagement with care, and A1c. However, there were differences by age, sex, and spoken language.

For example, the Hispanic group aged 65 years and older was less likely than those younger to be prescribed CGM, but this wasn’t seen in other ethnic groups. In fact, older White people were slightly more likely to have CGM prescribed. Spanish-speaking patients were about 43% less likely to have CGM prescribed than were English-speaking patients.

These findings suggest a dual approach might work best for improving CGM prescribing in primary care. “We can leverage the knowledge that some of these factors are independent of bias and promote clinical and evidence-based guidelines for CGM. Additionally, we should focus on physicians in training,” Dr. Milosavljevic said.

At the same time, “we need to tackle systemic inequity in prescription processes,” with measures such as improving prescription workflows, supporting prior authorization, and using patient hands-on support for older adults and Spanish-speaking individuals, he said.

In a message to this news organization, Tamara K. Oser, MD, wrote, “Disparities in CGM and other diabetes technology are prevalent and multifactorial. In addition to insurance barriers, implicit bias also plays a large role. Shared decision-making should always be used when deciding to prescribe diabetes technologies.”

The PREPARE 4 CGM study is evaluating willingness to pay for CGM, she noted.

“Even patients without insurance might want to purchase one sensor every few months to empower them to learn more about how food and exercise affect their glucose or to help assess the need for [adjusting] diabetes medications. It is an exciting time for people living with diabetes. Primary care, endocrinology, device manufacturers, and insurers should all do their part to assure increased access to these evidence-based technologies.”

Dr. Martens’ employer has received funds on his behalf for research and speaking support from Dexcom, Abbott Diabetes Care, Medtronic, Insulet, Tandem, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novo Nordisk, and for consulting from Sanofi and Eli Lilly and Company. He is employed by the nonprofit HealthPartners Institute dba International Diabetes Center and received no personal income from these activities.

The Osers have received advisory board consulting fees (through the University of Colorado) from Dexcom, Medscape Medical News, Ascensia, and Blue Circle Health and research grants (through the University of Colorado) from National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, Abbott Diabetes, Dexcom, and Insulet. They do not own stocks in any device or pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Milosavljevic’s work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science and Einstein-Montefiore Clinical and Translational Science Awards. He had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — As increasing data show benefit for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices beyond just insulin-treated diabetes, efforts are being made to optimize the use of CGM in primary care settings.

Currently, Medicare and most private insurers cover CGM for people with diabetes who use insulin, regardless of the type of diabetes or the type of insulin, and for those with a history of severe hypoglycemia. Data are increasingly showing benefit for people who don’t use insulin. As of now, with the exception of some state Medicaid beneficiaries, the majority must pay out of pocket.

Such use is expected to grow with the upcoming availability of two new over-the-counter CGMs, Dexcom’s Stelo and Abbott’s Libre Rio, both made for people with diabetes who don’t use insulin. (Abbott will also launch the Lingo, a wellness CGM for people without diabetes.)

This means that CGM will become increasingly prevalent in primary care, where there is currently a great deal of variability in the capacity to manage and use the data generated by the devices to improve diabetes management, experts said during an oral abstract session at the recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) 84th Scientific Sessions and in interviews with this news organization.

“It’s picking up steam, and there’s a lot more visibility of CGM in primary care and a lot more people prescribing it,” Thomas W. Martens, MD, medical director of the International Diabetes Center at HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, told this news organization. He noted that the recent switch in many cases of CGM from billing as durable medical equipment to pharmacy has made prescribing easier, while television advertising has increased demand.

But still unclear, he noted, is how the CGM data are being used. “The question is, are prescriptions just being sent out and people using it like a finger-stick blood glucose monitor, or is primary care really using the data to move diabetes forward? I think that’s where a lot of the work on dissemination and implementation is going. How do we really make this a useful tool for optimizing diabetes care?”

Informing Food Choice, Treatment Intensification

At the ADA meeting, Dr. Martens presented topline data from a randomized multicenter controlled trial funded by Abbott, examining the effect of CGM use on guiding food choices and other behaviors in 72 adults with type 2 diabetes who were not using insulin but who were using other glucose-lowering medications.

At 3 months, with no medication changes, there was a significant overall 26% reduction in time spent above 180 mg/dL (P < .0001), which didn›t differ significantly between those randomized to CGM alone or in conjunction with a food logging app. Both groups also experienced a significant 1.1% reduction in A1c (P < .0001) and about a 4-lb weight loss (P = .014 for CGM alone, P = .0032 for CGM + app).

“The win for people not on insulin is you can see the impact of food choices really quickly with a CGM ... and then perhaps modify that to improve postprandial hyperglycemia,” Dr. Martens said.

And for the clinician, “not everybody with type 2 diabetes not on insulin can get where they need to be just by changing their diets. The CGM is a pretty good tool for knowing when you need to advance therapy.”

Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (DCESs) Assist CGM Use

Another speaker at the ADA meeting, Sean M. Oser, MD, director of the Practice Innovation Program and associated director of the Primary Care Diabetes Lab at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, noted that 90% of adults with type 2 diabetes and 50% with type 1 diabetes receive their diabetes care in primary care settings.

“CGM is increasingly becoming standard of care in diabetes ... But [primary care providers] remain relatively untrained about CGM ... What I’m concerned about is the disparity disparities in who has access and who does not. We really need to bring our primary care colleagues along,” he said.

Dr. Oser described tools he and his wife, Tamara K. Oser, MD, professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the same institution, developed in conjunction with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), including the Transformation in Practice series (TIPS).

The PREPARE 4 CGM study examined the use of three different strategies for incorporating CGM into primary care settings: Either use of AAFP TIPS alone, TIPS plus practice facilitation services by coaches who assist the practice in implementing new workflows, or referral to a virtual CGM initiation service (virCIS) with a virtual CGM workshop that Dr. Oser and Dr. Oser also developed.

Of the 76 Colorado primary care practices participating (out of 60 planned), the 46 who chose AAFP TIPS were randomized to either the AAFP TIPS alone or to TIPS + practice facilitation. The other 30 chose virCIS with the onetime CGM basics webinar. The fact that more practices than anticipated were recruited for the study suggests that “primary care interest in CGM is very high. They want to learn,” Dr. Oser noted.

Of the 51 practice characteristics investigated, only one, the presence of a DCES, in the practice, was significantly associated with the choice of CGM implementation strategy. Of the 16 practices with access to a DCES, all of them chose self-initiation with CGM using TIPS. But of the 60 practices without a DCES, half chose the virCIS.

“We know that 36% of primary care practices have access to a DCES within the clinic, part-time or full-time, and that’s not enough, I would argue,” Dr. Oser said.

Indeed, Dr. Martens told this news organization that those professionals, formerly called “diabetes educators,” often aren’t available in primary care settings, especially in rural areas. “Unfortunately, they are not well reimbursed. A lot of care systems don’t employ as many as they ideally should because it tends not to be a moneymaker ... Something’s got to change with reimbursement for the cognitive aspects of diabetes management.”

Dr. Oser said his team’s next steps include completion of the virCIS operations, analysis of the effectiveness of the three implantation strategies in practice- and patient-level outcomes, a cost analysis of the three strategies, and further development of toolkits to assist in these efforts.

“One of our goals is to keep people at their primary care home, where they want to be ... Diabetes knows no borders. People should have access wherever they are,” Dr. Oser concluded in his ADA talk.

What Predicts Primary Care CGM Prescribing?

Further clues about effective strategies to improve CGM prescribing in primary care were provided in a study presented by Jovan Milosavljevic, MD, a second-year endocrinology fellow at the Fleischer Institute for Diabetes and Metabolism, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

He began by noting that there are currently 61.5 million diabetes visits annually in primary care compared with 32.0 million in specialty care and that there is a shortage of endocrinologists in the face of the rising number of people diagnosed with diabetes. “Primary care will continue to be the only point of care for most people with diabetes. So, standard-of-care treatment such as CGM must enter routine primary care practice to impact population-level health outcomes.”

Electronic health record data were examined for 39,710 patients with type 2 diabetes seen at 13 primary care sites affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center, a large safety net hospital in New York, where CGM is widely covered by public insurance. Between July 31, 2020, and July 31, 2023, a total of 3503, or just 8.8%, were prescribed CGM by a primary care provider.

Those with CGM prescribed were younger than those without (59.7 vs 62.7 years), about 40% of both groups were Hispanic or Black, and a majority were English-speaking: 84.5% of those prescribed CGM spoke English, while only 13.1% spoke Spanish. Over half (59.1%) of those prescribed CGM had commercial insurance, while only 11.2% had Medicaid and 29.7% had Medicare.

More patients with CGM prescribed had providers with more than 10 years in practice: 72.5% vs 64.5% with no CGM.

Not surprisingly, those with CGM prescribed were more likely on insulin — 21% using just basal and 35% on multiple daily injections. Those prescribed CGM had higher A1c levels before CGM prescription: 9.2% vs 7.2% for those not prescribed CGM.

No racial or ethnic bias was found in the relationships between CGM use and insulin use, provider experience, engagement with care, and A1c. However, there were differences by age, sex, and spoken language.

For example, the Hispanic group aged 65 years and older was less likely than those younger to be prescribed CGM, but this wasn’t seen in other ethnic groups. In fact, older White people were slightly more likely to have CGM prescribed. Spanish-speaking patients were about 43% less likely to have CGM prescribed than were English-speaking patients.

These findings suggest a dual approach might work best for improving CGM prescribing in primary care. “We can leverage the knowledge that some of these factors are independent of bias and promote clinical and evidence-based guidelines for CGM. Additionally, we should focus on physicians in training,” Dr. Milosavljevic said.

At the same time, “we need to tackle systemic inequity in prescription processes,” with measures such as improving prescription workflows, supporting prior authorization, and using patient hands-on support for older adults and Spanish-speaking individuals, he said.

In a message to this news organization, Tamara K. Oser, MD, wrote, “Disparities in CGM and other diabetes technology are prevalent and multifactorial. In addition to insurance barriers, implicit bias also plays a large role. Shared decision-making should always be used when deciding to prescribe diabetes technologies.”

The PREPARE 4 CGM study is evaluating willingness to pay for CGM, she noted.

“Even patients without insurance might want to purchase one sensor every few months to empower them to learn more about how food and exercise affect their glucose or to help assess the need for [adjusting] diabetes medications. It is an exciting time for people living with diabetes. Primary care, endocrinology, device manufacturers, and insurers should all do their part to assure increased access to these evidence-based technologies.”

Dr. Martens’ employer has received funds on his behalf for research and speaking support from Dexcom, Abbott Diabetes Care, Medtronic, Insulet, Tandem, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novo Nordisk, and for consulting from Sanofi and Eli Lilly and Company. He is employed by the nonprofit HealthPartners Institute dba International Diabetes Center and received no personal income from these activities.

The Osers have received advisory board consulting fees (through the University of Colorado) from Dexcom, Medscape Medical News, Ascensia, and Blue Circle Health and research grants (through the University of Colorado) from National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, Abbott Diabetes, Dexcom, and Insulet. They do not own stocks in any device or pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Milosavljevic’s work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science and Einstein-Montefiore Clinical and Translational Science Awards. He had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ADA 2024

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2024

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics. Click below to view highlights from the issue:

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics. Click below to view highlights from the issue:

Federal Health Care Data Trends is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, showcasing the latest research in health care for veterans and active-duty military members via compelling infographics. Click below to view highlights from the issue:

Ultraprocessed Foods Upped Risk for Diabetic Complications

TOPLINE:

In patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), eating more ultraprocessed food (UPF) increased the overall risk for microvascular complications and for diabetic kidney disease in particular. The risk was partly mediated by biomarkers related to body weight, lipid metabolism, and inflammation.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the association between the intake of UPF and the risk for diabetic microvascular complications in a prospective cohort of 5685 participants with T2D (mean age, 59.7 years; 63.8% men) from the UK Biobank.

- Dietary information of participants was collected with a web-based 24-hour dietary recall tool that recorded the frequency of consumption of 206 foods and 32 beverages.

- Researchers found five patterns that accounted for one third of UPF intake variation by estimated weight (not calories): Bread and spreads; cereal with liquids; high dairy and low cured meat; sugary beverages and snacks; and mixed beverages and savory snacks.

- The outcomes included the risk for overall microvascular complications; for diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and diabetic kidney disease; and for biomarkers related to microvascular complications.

TAKEAWAY:

- During a median follow-up duration of 12.7 years, 1243 composite microvascular complications were reported, including 599 diabetic retinopathy, 237 diabetic neuropathy, and 662 diabetic kidney disease events.

- Each 10% increase in the proportion of UPF consumption increased the risk for composite microvascular complications by 8% (hazard ratio [HR], 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03-1.13) and diabetic kidney disease by 13% (HR 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.20). No significant UPF intake association was found with diabetic retinopathy or diabetic neuropathy.

- In the biomarker mediation analysis, body mass index, triglycerides, and C-reactive protein collectively explained 22% (P < .001) and 15.8% (P < .001) of the associations of UPF consumption with composite microvascular complications and diabetic kidney disease, respectively.

- The food pattern rich in sugary beverages and snacks increased the risk for diabetic kidney disease, whereas the pattern rich in mixed beverages and savory snacks increased the risk for composite microvascular complications and diabetic retinopathy.

IN PRACTICE:

“In view of microvascular complications, our findings further support adhering to the recommendations outlined in the American Diabetes Association’s 2022 guidelines, which advocate for the preference of whole foods over highly processed ones,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yue Li, MBBS, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. It was published online in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

LIMITATIONS:

The dietary recall used in the UK Biobank was not specifically designed to collect dietary data according to the Nova food categories used in the study, which may have led to misclassifications. Data on usual dietary intake may not have been captured accurately, as all participants did not provide multiple dietary recalls. Individuals with T2D who completed dietary assessments were more likely to have a higher socioeconomic status and healthier lifestyle than those not filling the assessment, which could have resulted in an underrepresentation of high UPF consumers.

DISCLOSURES:

Some authors received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and other government sources. None of the authors declared any competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), eating more ultraprocessed food (UPF) increased the overall risk for microvascular complications and for diabetic kidney disease in particular. The risk was partly mediated by biomarkers related to body weight, lipid metabolism, and inflammation.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the association between the intake of UPF and the risk for diabetic microvascular complications in a prospective cohort of 5685 participants with T2D (mean age, 59.7 years; 63.8% men) from the UK Biobank.

- Dietary information of participants was collected with a web-based 24-hour dietary recall tool that recorded the frequency of consumption of 206 foods and 32 beverages.

- Researchers found five patterns that accounted for one third of UPF intake variation by estimated weight (not calories): Bread and spreads; cereal with liquids; high dairy and low cured meat; sugary beverages and snacks; and mixed beverages and savory snacks.

- The outcomes included the risk for overall microvascular complications; for diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and diabetic kidney disease; and for biomarkers related to microvascular complications.

TAKEAWAY:

- During a median follow-up duration of 12.7 years, 1243 composite microvascular complications were reported, including 599 diabetic retinopathy, 237 diabetic neuropathy, and 662 diabetic kidney disease events.

- Each 10% increase in the proportion of UPF consumption increased the risk for composite microvascular complications by 8% (hazard ratio [HR], 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03-1.13) and diabetic kidney disease by 13% (HR 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.20). No significant UPF intake association was found with diabetic retinopathy or diabetic neuropathy.

- In the biomarker mediation analysis, body mass index, triglycerides, and C-reactive protein collectively explained 22% (P < .001) and 15.8% (P < .001) of the associations of UPF consumption with composite microvascular complications and diabetic kidney disease, respectively.

- The food pattern rich in sugary beverages and snacks increased the risk for diabetic kidney disease, whereas the pattern rich in mixed beverages and savory snacks increased the risk for composite microvascular complications and diabetic retinopathy.

IN PRACTICE:

“In view of microvascular complications, our findings further support adhering to the recommendations outlined in the American Diabetes Association’s 2022 guidelines, which advocate for the preference of whole foods over highly processed ones,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yue Li, MBBS, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. It was published online in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

LIMITATIONS:

The dietary recall used in the UK Biobank was not specifically designed to collect dietary data according to the Nova food categories used in the study, which may have led to misclassifications. Data on usual dietary intake may not have been captured accurately, as all participants did not provide multiple dietary recalls. Individuals with T2D who completed dietary assessments were more likely to have a higher socioeconomic status and healthier lifestyle than those not filling the assessment, which could have resulted in an underrepresentation of high UPF consumers.

DISCLOSURES:

Some authors received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and other government sources. None of the authors declared any competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), eating more ultraprocessed food (UPF) increased the overall risk for microvascular complications and for diabetic kidney disease in particular. The risk was partly mediated by biomarkers related to body weight, lipid metabolism, and inflammation.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the association between the intake of UPF and the risk for diabetic microvascular complications in a prospective cohort of 5685 participants with T2D (mean age, 59.7 years; 63.8% men) from the UK Biobank.

- Dietary information of participants was collected with a web-based 24-hour dietary recall tool that recorded the frequency of consumption of 206 foods and 32 beverages.

- Researchers found five patterns that accounted for one third of UPF intake variation by estimated weight (not calories): Bread and spreads; cereal with liquids; high dairy and low cured meat; sugary beverages and snacks; and mixed beverages and savory snacks.

- The outcomes included the risk for overall microvascular complications; for diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and diabetic kidney disease; and for biomarkers related to microvascular complications.

TAKEAWAY:

- During a median follow-up duration of 12.7 years, 1243 composite microvascular complications were reported, including 599 diabetic retinopathy, 237 diabetic neuropathy, and 662 diabetic kidney disease events.

- Each 10% increase in the proportion of UPF consumption increased the risk for composite microvascular complications by 8% (hazard ratio [HR], 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03-1.13) and diabetic kidney disease by 13% (HR 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.20). No significant UPF intake association was found with diabetic retinopathy or diabetic neuropathy.

- In the biomarker mediation analysis, body mass index, triglycerides, and C-reactive protein collectively explained 22% (P < .001) and 15.8% (P < .001) of the associations of UPF consumption with composite microvascular complications and diabetic kidney disease, respectively.

- The food pattern rich in sugary beverages and snacks increased the risk for diabetic kidney disease, whereas the pattern rich in mixed beverages and savory snacks increased the risk for composite microvascular complications and diabetic retinopathy.

IN PRACTICE:

“In view of microvascular complications, our findings further support adhering to the recommendations outlined in the American Diabetes Association’s 2022 guidelines, which advocate for the preference of whole foods over highly processed ones,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yue Li, MBBS, School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. It was published online in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

LIMITATIONS:

The dietary recall used in the UK Biobank was not specifically designed to collect dietary data according to the Nova food categories used in the study, which may have led to misclassifications. Data on usual dietary intake may not have been captured accurately, as all participants did not provide multiple dietary recalls. Individuals with T2D who completed dietary assessments were more likely to have a higher socioeconomic status and healthier lifestyle than those not filling the assessment, which could have resulted in an underrepresentation of high UPF consumers.

DISCLOSURES:

Some authors received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and other government sources. None of the authors declared any competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Weight Loss in Obesity May Create ‘Positive’ Hormone Changes

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why Is Mom’s Type 1 Diabetes Half as Likely as Dad’s to Pass to Child?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Individuals with a family history of type 1 diabetes face 8-15 times higher risk for this condition than the general population, with the risk of inheritance from mothers with type 1 diabetes being about half that of fathers with type 1 diabetes; however, it is unclear if the effect continues past childhood and what is responsible for the difference in risk.

- Researchers performed a meta-analysis across five cohort studies involving 11,475 individuals diagnosed with type 1 diabetes aged 0-88 years to evaluate if maternal type 1 diabetes conferred relative protection only to young children.

- They compared the proportion of individuals with type 1 diabetes with affected fathers versus mothers and explored if this comparison was altered by the age at diagnosis and the timing of parental diagnosis relative to the birth of the offspring.

- Lastly, the inherited genetic risk for type 1 diabetes was compared between those with affected mothers versus fathers using a risk score composed of more than 60 different gene variants associated with type 1 diabetes.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with type 1 diabetes were almost twice as likely to have a father with the condition than a mother (odds ratio, 1.79; P < .0001).

- The protective effect of maternal diabetes was seen regardless of whether the individuals were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes before or after age 18 years (P < .0001).

- Maternal diabetes was linked to a lower risk for type 1 diabetes in children only if the mother had type 1 diabetes during pregnancy.

- The genetic risk score for type 1 diabetes was not significantly different between those with affected fathers versus mothers (P = .31).

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding why having a mother compared with a father with type 1 diabetes offers a relative protection against type 1 diabetes could help us develop new ways to prevent type 1 diabetes, such as treatments that mimic some of the protective elements from mothers,” study author Lowri Allen, MBChB, said in a news release.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dr. Allen from the Diabetes Research Group, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, and was published as an early release from the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

LIMITATIONS:

This abstract did not discuss any limitations. The number of individuals and parents with type 1 diabetes in the meta-analysis was not disclosed. The baseline risk for type 1 diabetes among individuals with a mother, father, or both or no parent with type 1 diabetes was not disclosed. The number of people with type 1 diabetes under and over age 18 was not disclosed, nor were the numbers of mothers and fathers with type 1 diabetes. The relative risk in individuals having no parent with type 1 diabetes was not disclosed. Moreover, the race and ethnicity of the study populations were not disclosed.

DISCLOSURES:

The Wellcome Trust supported this study. The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Individuals with a family history of type 1 diabetes face 8-15 times higher risk for this condition than the general population, with the risk of inheritance from mothers with type 1 diabetes being about half that of fathers with type 1 diabetes; however, it is unclear if the effect continues past childhood and what is responsible for the difference in risk.

- Researchers performed a meta-analysis across five cohort studies involving 11,475 individuals diagnosed with type 1 diabetes aged 0-88 years to evaluate if maternal type 1 diabetes conferred relative protection only to young children.

- They compared the proportion of individuals with type 1 diabetes with affected fathers versus mothers and explored if this comparison was altered by the age at diagnosis and the timing of parental diagnosis relative to the birth of the offspring.

- Lastly, the inherited genetic risk for type 1 diabetes was compared between those with affected mothers versus fathers using a risk score composed of more than 60 different gene variants associated with type 1 diabetes.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with type 1 diabetes were almost twice as likely to have a father with the condition than a mother (odds ratio, 1.79; P < .0001).

- The protective effect of maternal diabetes was seen regardless of whether the individuals were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes before or after age 18 years (P < .0001).

- Maternal diabetes was linked to a lower risk for type 1 diabetes in children only if the mother had type 1 diabetes during pregnancy.

- The genetic risk score for type 1 diabetes was not significantly different between those with affected fathers versus mothers (P = .31).

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding why having a mother compared with a father with type 1 diabetes offers a relative protection against type 1 diabetes could help us develop new ways to prevent type 1 diabetes, such as treatments that mimic some of the protective elements from mothers,” study author Lowri Allen, MBChB, said in a news release.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dr. Allen from the Diabetes Research Group, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, and was published as an early release from the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

LIMITATIONS:

This abstract did not discuss any limitations. The number of individuals and parents with type 1 diabetes in the meta-analysis was not disclosed. The baseline risk for type 1 diabetes among individuals with a mother, father, or both or no parent with type 1 diabetes was not disclosed. The number of people with type 1 diabetes under and over age 18 was not disclosed, nor were the numbers of mothers and fathers with type 1 diabetes. The relative risk in individuals having no parent with type 1 diabetes was not disclosed. Moreover, the race and ethnicity of the study populations were not disclosed.

DISCLOSURES:

The Wellcome Trust supported this study. The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Individuals with a family history of type 1 diabetes face 8-15 times higher risk for this condition than the general population, with the risk of inheritance from mothers with type 1 diabetes being about half that of fathers with type 1 diabetes; however, it is unclear if the effect continues past childhood and what is responsible for the difference in risk.

- Researchers performed a meta-analysis across five cohort studies involving 11,475 individuals diagnosed with type 1 diabetes aged 0-88 years to evaluate if maternal type 1 diabetes conferred relative protection only to young children.

- They compared the proportion of individuals with type 1 diabetes with affected fathers versus mothers and explored if this comparison was altered by the age at diagnosis and the timing of parental diagnosis relative to the birth of the offspring.

- Lastly, the inherited genetic risk for type 1 diabetes was compared between those with affected mothers versus fathers using a risk score composed of more than 60 different gene variants associated with type 1 diabetes.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with type 1 diabetes were almost twice as likely to have a father with the condition than a mother (odds ratio, 1.79; P < .0001).

- The protective effect of maternal diabetes was seen regardless of whether the individuals were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes before or after age 18 years (P < .0001).

- Maternal diabetes was linked to a lower risk for type 1 diabetes in children only if the mother had type 1 diabetes during pregnancy.

- The genetic risk score for type 1 diabetes was not significantly different between those with affected fathers versus mothers (P = .31).

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding why having a mother compared with a father with type 1 diabetes offers a relative protection against type 1 diabetes could help us develop new ways to prevent type 1 diabetes, such as treatments that mimic some of the protective elements from mothers,” study author Lowri Allen, MBChB, said in a news release.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dr. Allen from the Diabetes Research Group, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, and was published as an early release from the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

LIMITATIONS:

This abstract did not discuss any limitations. The number of individuals and parents with type 1 diabetes in the meta-analysis was not disclosed. The baseline risk for type 1 diabetes among individuals with a mother, father, or both or no parent with type 1 diabetes was not disclosed. The number of people with type 1 diabetes under and over age 18 was not disclosed, nor were the numbers of mothers and fathers with type 1 diabetes. The relative risk in individuals having no parent with type 1 diabetes was not disclosed. Moreover, the race and ethnicity of the study populations were not disclosed.

DISCLOSURES:

The Wellcome Trust supported this study. The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Non-Prescription Semaglutide Purchased Online Poses Risks

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.

“Semaglutide products are actively being sold without prescription by illegal online pharmacies, with vendors shipping unregistered and falsified products,” wrote Amir Reza Ashraf, PharmD, of the University of Pécs, Hungary, and colleagues in their paper, published online on August 2, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted in July 2023, but its publication comes a week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert about dosing errors in compounded semaglutide, which typically does require a prescription.

Study coauthor Tim K. Mackey, PhD, told this news organization, “Compounding pharmacies are another element of this risk that has become more prominent now but arguably have more controls if prescribed appropriately, while the traditional ‘no-prescription’ online market still exists and will continue to evolve.”

Overall, said Dr. Mackey, professor of global health at the University of California San Diego and director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute,

He advises clinicians to actively discuss with their patients the risks associated with semaglutide and, specifically, the dangers of buying it online. “Clinicians can act as a primary information source for patient safety information by letting their patients know about these risks ... and also asking where patients get their medications in case they are concerned about reports of adverse events or other patient safety issues.”

Buyer Beware: Online Semaglutide Purchases Not as They Seem

The investigators began by searching online for websites advertising semaglutide without a prescription. They ordered products from six online vendors that showed up prominently in the searches. Of those, three offered prefilled 0.25 mg/dose semaglutide injection pens, while the other three sold vials of lyophilized semaglutide powder to be reconstituted to solution for injection. Prices for the smallest dose and quantity ranged from $113 to $360.

Only three of the ordered products — all vials — actually showed up. The advertised prefilled pens were all nondelivery scams, with requests for an extra payment of $650-$1200 purportedly to clear customs. This was confirmed as fraudulent by customs agencies, the authors noted.

The three vial products were received and assessed physically, of both the packaging and the actual product, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine purity and peptide concentration, and microbiologically, to examine sterility.

Using a checklist from the International Pharmaceutical Federation, Dr. Ashraf and colleagues found “clear discrepancies in regulatory registration information, accurate labeling, and evidence products were likely unregistered or unlicensed.”

Quality testing showed that one sample had an elevated presence of endotoxin suggesting possible contamination. While all three actually did contain semaglutide, the measured content exceeded the labeled amount by 29%-39%, posing a risk that users could receive up to 39% more than intended per injection, “particularly concerning if a consumer has to reconstitute and self-inject,” Dr. Mackey noted.

At least one of these sites in this study, “semaspace.com,” was subsequently sent a warning letter by the FDA for unauthorized semaglutide sale, Mackey noted.

Unfortunately, he told this news organization, these dangers are likely to persist. “There is a strong market opportunity to introduce counterfeit and unauthorized versions of semaglutide. Counterfeiters will continue to innovate with where they sell products, what products they offer, and how they mislead consumers about the safety and legality of what they are offering online. We are likely just at the beginning of counterfeiting of semaglutide, and it is likely that these false products will become endemic in our supply chain.”

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund. The authors had no further disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.