User login

Do GLP-1s Lower CRC Risk in Patients With Obesity and T2D?

SAN DIEGO — new research showed.

CRC risk was also lower for patients taking GLP-1s than the general population.

“Our findings show we might need to evaluate these therapies beyond their glycemic or weight loss [effects],” said first author Omar Al Ta’ani, MD, of the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh.

This supports future prospective studies examining GLP-1s for CRC reduction, added Ta’ani, who presented the results at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity are known to have a higher risk for CRC, stemming from metabolic risk factors. Whereas prior studies suggested that GLP-1s decrease the risk for CRC compared with other antidiabetic medications, studies looking at the risk for CRC associated with bariatric surgery have had more mixed results, Ta’ani said.

For the comparison, Ta’ani and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the TriNetX database, identifying patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 30) enrolled in the database between 2005 and 2019.

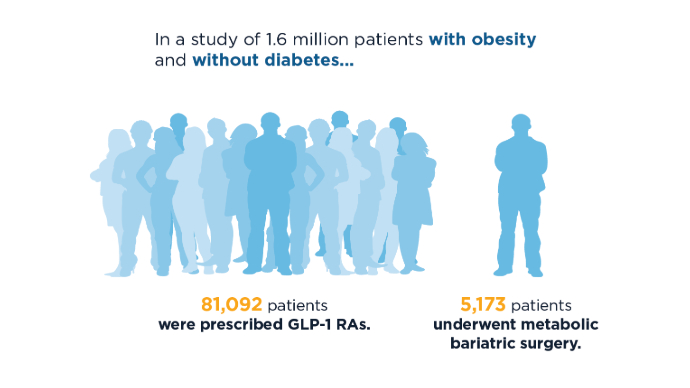

Overall, the study included 94,098 GLP-1 users and 24,969 patients who underwent bariatric surgery. Those with a prior history of CRC were excluded.

Using propensity score matching, patients treated with GLP-1s were matched 1:1 with patients who had bariatric surgery based on wide-ranging factors including age, race, gender, demographics, diseases, medications, personal and family history, and hemoglobin A1c.

After the propensity matching, each group included 21,022 patients. About 64% in each group were women; their median age was 53 years and about 65% were White.

Overall, the results showed that patients on GLP-1s had a significantly lower CRC risk compared with those who had bariatric surgery (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.29; P < .0001). The lower risk was also observed among those with high obesity (defined as BMI > 35) compared with those who had surgery (aHR, 0.39; P < .0001).

The results were consistent across genders; however, the differences between GLP-1s and bariatric surgery were not observed in the 18- to 45-year-old age group (BMI > 30, P = .0809; BMI > 35, P = .2318).

Compared with the general population, patients on GLP-1s also had a reduced risk for CRC (aHR, 0.28; P < .0001); however, the difference was not observed between the bariatric surgery group and the general population (aHR, 1.11; P = .3).

Among patients with type 2 diabetes with CRC and a BMI > 30, the 5-year mortality rate was lower in the GLP-1 group vs the bariatric surgery group (aHR, 0.42; P < .001).

Speculating on the mechanisms of GLP-1s that could result in a greater reduction in CRC risk, Ta’ani explained that the key pathways linking type 2 diabetes, obesity, and CRC include hyperinsulinemia, chronic inflammation, and impaired immune surveillance.

Studies have shown that GLP-1s may be more effective in addressing the collective pathways, he said. They “may improve insulin resistance and lower systemic inflammation.”

Furthermore, GLP1s “inhibit tumor pathways like Wnt/beta-catenin and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, which promote apoptosis and reduce tumor cell proliferation,” he added.

Bariatric Surgery Findings Questioned

Meanwhile, “bariatric surgery’s impact on CRC remains mixed,” said Ta’ani.

Commenting on the study, Vance L. Albaugh, MD, an assistant professor of metabolic surgery at the Metamor Institute, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, noted that prior studies, including a recent meta-analysis, suggest a potential benefit of bariatric surgery in cancer prevention.

“I think the [current study] is interesting, but it’s been pretty [well-reported] that bariatric surgery does decrease cancer incidence, so I find it questionable that this study shows the opposite of what’s in the literature,” Albaugh, an obesity medicine specialist and bariatric surgeon, said in an interview.

Ta’ani acknowledged the study’s important limitations, including that with a retrospective design, causality cannot be firmly established.

And, as noted by an audience member in the session’s Q&A, the study ended in 2019, which was before GLP-1s had taken off as anti-obesity drugs and before US Food and Drug Administration approvals for weight loss.

Participants were matched based on BMI, however, Ta’ani pointed out.

Albaugh agreed that the study ending in 2019 was a notable limitation. However, the relatively long study period — extending from 2005 to 2019 — was a strength.

“It’s nice to have a very long period to capture people who are diagnosed, because it takes a long time to develop CRC,” he said. “To evaluate effects [of more recent drug regimens], you would not be able to have the follow-up they had.”

Other study limitations included the need to adjust for ranges of obesity severity, said Albaugh. “The risk of colorectal cancer is probably much different for someone with a BMI of 60 vs a BMI of 30.”

Ultimately, a key question the study results raise is whether GLP-1 drugs have protective effects above and beyond that of weight loss, he said.

“I think that’s a very exciting question and that’s what I think the researchers’ next work should really focus on.”

Ta’ani had no disclosures to report. Albaugh reported that he had consulted for Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — new research showed.

CRC risk was also lower for patients taking GLP-1s than the general population.

“Our findings show we might need to evaluate these therapies beyond their glycemic or weight loss [effects],” said first author Omar Al Ta’ani, MD, of the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh.

This supports future prospective studies examining GLP-1s for CRC reduction, added Ta’ani, who presented the results at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity are known to have a higher risk for CRC, stemming from metabolic risk factors. Whereas prior studies suggested that GLP-1s decrease the risk for CRC compared with other antidiabetic medications, studies looking at the risk for CRC associated with bariatric surgery have had more mixed results, Ta’ani said.

For the comparison, Ta’ani and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the TriNetX database, identifying patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 30) enrolled in the database between 2005 and 2019.

Overall, the study included 94,098 GLP-1 users and 24,969 patients who underwent bariatric surgery. Those with a prior history of CRC were excluded.

Using propensity score matching, patients treated with GLP-1s were matched 1:1 with patients who had bariatric surgery based on wide-ranging factors including age, race, gender, demographics, diseases, medications, personal and family history, and hemoglobin A1c.

After the propensity matching, each group included 21,022 patients. About 64% in each group were women; their median age was 53 years and about 65% were White.

Overall, the results showed that patients on GLP-1s had a significantly lower CRC risk compared with those who had bariatric surgery (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.29; P < .0001). The lower risk was also observed among those with high obesity (defined as BMI > 35) compared with those who had surgery (aHR, 0.39; P < .0001).

The results were consistent across genders; however, the differences between GLP-1s and bariatric surgery were not observed in the 18- to 45-year-old age group (BMI > 30, P = .0809; BMI > 35, P = .2318).

Compared with the general population, patients on GLP-1s also had a reduced risk for CRC (aHR, 0.28; P < .0001); however, the difference was not observed between the bariatric surgery group and the general population (aHR, 1.11; P = .3).

Among patients with type 2 diabetes with CRC and a BMI > 30, the 5-year mortality rate was lower in the GLP-1 group vs the bariatric surgery group (aHR, 0.42; P < .001).

Speculating on the mechanisms of GLP-1s that could result in a greater reduction in CRC risk, Ta’ani explained that the key pathways linking type 2 diabetes, obesity, and CRC include hyperinsulinemia, chronic inflammation, and impaired immune surveillance.

Studies have shown that GLP-1s may be more effective in addressing the collective pathways, he said. They “may improve insulin resistance and lower systemic inflammation.”

Furthermore, GLP1s “inhibit tumor pathways like Wnt/beta-catenin and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, which promote apoptosis and reduce tumor cell proliferation,” he added.

Bariatric Surgery Findings Questioned

Meanwhile, “bariatric surgery’s impact on CRC remains mixed,” said Ta’ani.

Commenting on the study, Vance L. Albaugh, MD, an assistant professor of metabolic surgery at the Metamor Institute, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, noted that prior studies, including a recent meta-analysis, suggest a potential benefit of bariatric surgery in cancer prevention.

“I think the [current study] is interesting, but it’s been pretty [well-reported] that bariatric surgery does decrease cancer incidence, so I find it questionable that this study shows the opposite of what’s in the literature,” Albaugh, an obesity medicine specialist and bariatric surgeon, said in an interview.

Ta’ani acknowledged the study’s important limitations, including that with a retrospective design, causality cannot be firmly established.

And, as noted by an audience member in the session’s Q&A, the study ended in 2019, which was before GLP-1s had taken off as anti-obesity drugs and before US Food and Drug Administration approvals for weight loss.

Participants were matched based on BMI, however, Ta’ani pointed out.

Albaugh agreed that the study ending in 2019 was a notable limitation. However, the relatively long study period — extending from 2005 to 2019 — was a strength.

“It’s nice to have a very long period to capture people who are diagnosed, because it takes a long time to develop CRC,” he said. “To evaluate effects [of more recent drug regimens], you would not be able to have the follow-up they had.”

Other study limitations included the need to adjust for ranges of obesity severity, said Albaugh. “The risk of colorectal cancer is probably much different for someone with a BMI of 60 vs a BMI of 30.”

Ultimately, a key question the study results raise is whether GLP-1 drugs have protective effects above and beyond that of weight loss, he said.

“I think that’s a very exciting question and that’s what I think the researchers’ next work should really focus on.”

Ta’ani had no disclosures to report. Albaugh reported that he had consulted for Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — new research showed.

CRC risk was also lower for patients taking GLP-1s than the general population.

“Our findings show we might need to evaluate these therapies beyond their glycemic or weight loss [effects],” said first author Omar Al Ta’ani, MD, of the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh.

This supports future prospective studies examining GLP-1s for CRC reduction, added Ta’ani, who presented the results at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity are known to have a higher risk for CRC, stemming from metabolic risk factors. Whereas prior studies suggested that GLP-1s decrease the risk for CRC compared with other antidiabetic medications, studies looking at the risk for CRC associated with bariatric surgery have had more mixed results, Ta’ani said.

For the comparison, Ta’ani and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the TriNetX database, identifying patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 30) enrolled in the database between 2005 and 2019.

Overall, the study included 94,098 GLP-1 users and 24,969 patients who underwent bariatric surgery. Those with a prior history of CRC were excluded.

Using propensity score matching, patients treated with GLP-1s were matched 1:1 with patients who had bariatric surgery based on wide-ranging factors including age, race, gender, demographics, diseases, medications, personal and family history, and hemoglobin A1c.

After the propensity matching, each group included 21,022 patients. About 64% in each group were women; their median age was 53 years and about 65% were White.

Overall, the results showed that patients on GLP-1s had a significantly lower CRC risk compared with those who had bariatric surgery (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.29; P < .0001). The lower risk was also observed among those with high obesity (defined as BMI > 35) compared with those who had surgery (aHR, 0.39; P < .0001).

The results were consistent across genders; however, the differences between GLP-1s and bariatric surgery were not observed in the 18- to 45-year-old age group (BMI > 30, P = .0809; BMI > 35, P = .2318).

Compared with the general population, patients on GLP-1s also had a reduced risk for CRC (aHR, 0.28; P < .0001); however, the difference was not observed between the bariatric surgery group and the general population (aHR, 1.11; P = .3).

Among patients with type 2 diabetes with CRC and a BMI > 30, the 5-year mortality rate was lower in the GLP-1 group vs the bariatric surgery group (aHR, 0.42; P < .001).

Speculating on the mechanisms of GLP-1s that could result in a greater reduction in CRC risk, Ta’ani explained that the key pathways linking type 2 diabetes, obesity, and CRC include hyperinsulinemia, chronic inflammation, and impaired immune surveillance.

Studies have shown that GLP-1s may be more effective in addressing the collective pathways, he said. They “may improve insulin resistance and lower systemic inflammation.”

Furthermore, GLP1s “inhibit tumor pathways like Wnt/beta-catenin and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, which promote apoptosis and reduce tumor cell proliferation,” he added.

Bariatric Surgery Findings Questioned

Meanwhile, “bariatric surgery’s impact on CRC remains mixed,” said Ta’ani.

Commenting on the study, Vance L. Albaugh, MD, an assistant professor of metabolic surgery at the Metamor Institute, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, noted that prior studies, including a recent meta-analysis, suggest a potential benefit of bariatric surgery in cancer prevention.

“I think the [current study] is interesting, but it’s been pretty [well-reported] that bariatric surgery does decrease cancer incidence, so I find it questionable that this study shows the opposite of what’s in the literature,” Albaugh, an obesity medicine specialist and bariatric surgeon, said in an interview.

Ta’ani acknowledged the study’s important limitations, including that with a retrospective design, causality cannot be firmly established.

And, as noted by an audience member in the session’s Q&A, the study ended in 2019, which was before GLP-1s had taken off as anti-obesity drugs and before US Food and Drug Administration approvals for weight loss.

Participants were matched based on BMI, however, Ta’ani pointed out.

Albaugh agreed that the study ending in 2019 was a notable limitation. However, the relatively long study period — extending from 2005 to 2019 — was a strength.

“It’s nice to have a very long period to capture people who are diagnosed, because it takes a long time to develop CRC,” he said. “To evaluate effects [of more recent drug regimens], you would not be able to have the follow-up they had.”

Other study limitations included the need to adjust for ranges of obesity severity, said Albaugh. “The risk of colorectal cancer is probably much different for someone with a BMI of 60 vs a BMI of 30.”

Ultimately, a key question the study results raise is whether GLP-1 drugs have protective effects above and beyond that of weight loss, he said.

“I think that’s a very exciting question and that’s what I think the researchers’ next work should really focus on.”

Ta’ani had no disclosures to report. Albaugh reported that he had consulted for Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DDW 2025

ctDNA Positivity in Colorectal Cancer Links to Chemotherapy Response

SAN DIEGO — the results of the BESPOKE study showed.

“These findings highlight the value of utilizing ctDNA to select which patients should receive management chemotherapy and which patients can be potentially spared chemotherapy’s physical, emotional, and financial toxicities without compromising their long-term outcomes,” said first author Kim Magee of Natera, a clinical genetic testing company in Austin, Texas.

“ctDNA is emerging as the most powerful and prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer,” said Magee, who presented the findings at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

In stage II CRC, as many as 80% of patients are cured by surgery alone, while only about 5% benefit from chemotherapy. In stage III CRC, about half of patients are cured by surgery alone, while only 20% benefit from chemotherapy, and 30% recur despite chemotherapy, Magee explained.

The inability to pinpoint which patients will most benefit from chemotherapy means “we know we are needlessly treating [many] of these patients,” she said.

ctDNA Offers Insights Into Tumor’s Real-Time Status

Just as cells release fragments (cell-free DNA) into the blood as they regenerate, tumor cells also release fragments — ctDNA — which can represent a biomarker of a cancer’s current state, Magee explained.

Because the DNA fragments have a half-life of only about 2 hours, they represent a key snapshot in real time, “as opposed to imaging, which can take several weeks or months to show changes,” she said.

To determine the effects of ctDNA testing on treatment decisions and asymptomatic recurrence rates, Magee and colleagues analyzed data from the multicenter, prospective study, which used the Signatera (Natera) residual disease test.

The study included 1794 patients with resected stage II-III CRC who were treated with the standard of care between May 2020 and March 2023 who had complete clinical and laboratory data available.

ctDNA was collected 2-6 weeks post surgery and at surveillance months 2, 4, 6, and every 3 months through month 24.

Among the 1166 patients included in a final analysis, 694 (59.5%) patients received adjunctive chemotherapy, and 472 (40.5%) received no chemotherapy.

Among those with stage II CRC, a postoperative MRD positivity rate was 7.54%, while the rate in those with stage III disease was 28.35%.

Overall, 16.1% of patients had a recurrence by the trial end at 24 months.

The results showed that among patients who tested negative for ctDNA, the disease-free survival estimates were highly favorable, at 91.8% for stage II and 87.4% for stage III CRC.

Comparatively, for those who were ctDNA-positive, disease-free survival rates were just 45.9% and 35.5%, respectively, regardless of whether those patients received adjunctive chemotherapy.

At the study’s first ctDNA surveillance timepoint, patients who were ctDNA-positive with stage II and III CRC combined had substantially worse disease-free survival than patients who were ctDNA-negative (HR, 26.4; P < .0001).

Impact of Chemotherapy

Patients who were found to be MRD-positive on ctDNA testing and treated with chemotherapy had a 40.3% 2-year disease-free survival rate compared with just 24.7% among MRD-positive patients who did not receive chemotherapy.

Meanwhile, those who were MRD-negative and treated with chemotherapy had a substantially higher 2-year disease-free survival rate of 89.7% — nearly identical to the 89.5% observed in the no-chemotherapy group.

The findings underscored that “the adjuvant chemotherapy benefits were only observed among those who were ctDNA-positive,” Magee said.

“ctDNA can guide postsurgical treatment decisions by identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from chemotherapy, and in the surveillance setting, ctDNA can predict recurrence — usually ahead of scans,” she added. “This opens the opportunity to intervene and give those patients a second chance at cure.”

On the heels of major recent advances including CT, MRI, and PET-CT, “we believe that ctDNA represents the next major pivotal advancement in monitoring and eventually better understanding cancer diagnostics,” Magee said.

Commenting on the study, William M. Grady, MD, AGAF, medical director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Gastrointestinal Cancer Prevention Clinic, Seattle, said the BESPOKE trial represents a “well-done” study, adding to research underscoring that “MRD testing is a more accurate prognostic assay than the current standards of CT scan and CEA [carcinoembryonic antigen, a tumor marker] testing.”

However, “a limitation is that this is 2 years of follow-up, [while] 5-year follow-up data would be ideal,” he said in an interview, noting, importantly, that “a small number of patients who have no evidence of disease (NED) at 2 years develop recurrence by 5 years.”

Furthermore, more research demonstrating the outcomes of MRD detection is needed, Grady added.

“A caveat is that studies are still needed showing that if you change your care of patients based on the MRD result, that you improve outcomes,” he said. “These studies are being planned and initiated at this time, from my understanding.”

Oncologists treating patients with CRC are commonly performing MRD assessment with ctDNA assays; however, Grady noted that the practice is still not the standard of care.

Regarding the suggestion of ctDNA representing the next major, pivotal step in cancer monitoring, Grady responded that “I think this is aspirational, and further studies are needed to make this claim.”

However, “it does look like it has the promise to turn out to be true.”

Magee is an employee of Nater. Grady has been on the scientific advisory boards for Guardant Health and Freenome and has consulted for Karius.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — the results of the BESPOKE study showed.

“These findings highlight the value of utilizing ctDNA to select which patients should receive management chemotherapy and which patients can be potentially spared chemotherapy’s physical, emotional, and financial toxicities without compromising their long-term outcomes,” said first author Kim Magee of Natera, a clinical genetic testing company in Austin, Texas.

“ctDNA is emerging as the most powerful and prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer,” said Magee, who presented the findings at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

In stage II CRC, as many as 80% of patients are cured by surgery alone, while only about 5% benefit from chemotherapy. In stage III CRC, about half of patients are cured by surgery alone, while only 20% benefit from chemotherapy, and 30% recur despite chemotherapy, Magee explained.

The inability to pinpoint which patients will most benefit from chemotherapy means “we know we are needlessly treating [many] of these patients,” she said.

ctDNA Offers Insights Into Tumor’s Real-Time Status

Just as cells release fragments (cell-free DNA) into the blood as they regenerate, tumor cells also release fragments — ctDNA — which can represent a biomarker of a cancer’s current state, Magee explained.

Because the DNA fragments have a half-life of only about 2 hours, they represent a key snapshot in real time, “as opposed to imaging, which can take several weeks or months to show changes,” she said.

To determine the effects of ctDNA testing on treatment decisions and asymptomatic recurrence rates, Magee and colleagues analyzed data from the multicenter, prospective study, which used the Signatera (Natera) residual disease test.

The study included 1794 patients with resected stage II-III CRC who were treated with the standard of care between May 2020 and March 2023 who had complete clinical and laboratory data available.

ctDNA was collected 2-6 weeks post surgery and at surveillance months 2, 4, 6, and every 3 months through month 24.

Among the 1166 patients included in a final analysis, 694 (59.5%) patients received adjunctive chemotherapy, and 472 (40.5%) received no chemotherapy.

Among those with stage II CRC, a postoperative MRD positivity rate was 7.54%, while the rate in those with stage III disease was 28.35%.

Overall, 16.1% of patients had a recurrence by the trial end at 24 months.

The results showed that among patients who tested negative for ctDNA, the disease-free survival estimates were highly favorable, at 91.8% for stage II and 87.4% for stage III CRC.

Comparatively, for those who were ctDNA-positive, disease-free survival rates were just 45.9% and 35.5%, respectively, regardless of whether those patients received adjunctive chemotherapy.

At the study’s first ctDNA surveillance timepoint, patients who were ctDNA-positive with stage II and III CRC combined had substantially worse disease-free survival than patients who were ctDNA-negative (HR, 26.4; P < .0001).

Impact of Chemotherapy

Patients who were found to be MRD-positive on ctDNA testing and treated with chemotherapy had a 40.3% 2-year disease-free survival rate compared with just 24.7% among MRD-positive patients who did not receive chemotherapy.

Meanwhile, those who were MRD-negative and treated with chemotherapy had a substantially higher 2-year disease-free survival rate of 89.7% — nearly identical to the 89.5% observed in the no-chemotherapy group.

The findings underscored that “the adjuvant chemotherapy benefits were only observed among those who were ctDNA-positive,” Magee said.

“ctDNA can guide postsurgical treatment decisions by identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from chemotherapy, and in the surveillance setting, ctDNA can predict recurrence — usually ahead of scans,” she added. “This opens the opportunity to intervene and give those patients a second chance at cure.”

On the heels of major recent advances including CT, MRI, and PET-CT, “we believe that ctDNA represents the next major pivotal advancement in monitoring and eventually better understanding cancer diagnostics,” Magee said.

Commenting on the study, William M. Grady, MD, AGAF, medical director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Gastrointestinal Cancer Prevention Clinic, Seattle, said the BESPOKE trial represents a “well-done” study, adding to research underscoring that “MRD testing is a more accurate prognostic assay than the current standards of CT scan and CEA [carcinoembryonic antigen, a tumor marker] testing.”

However, “a limitation is that this is 2 years of follow-up, [while] 5-year follow-up data would be ideal,” he said in an interview, noting, importantly, that “a small number of patients who have no evidence of disease (NED) at 2 years develop recurrence by 5 years.”

Furthermore, more research demonstrating the outcomes of MRD detection is needed, Grady added.

“A caveat is that studies are still needed showing that if you change your care of patients based on the MRD result, that you improve outcomes,” he said. “These studies are being planned and initiated at this time, from my understanding.”

Oncologists treating patients with CRC are commonly performing MRD assessment with ctDNA assays; however, Grady noted that the practice is still not the standard of care.

Regarding the suggestion of ctDNA representing the next major, pivotal step in cancer monitoring, Grady responded that “I think this is aspirational, and further studies are needed to make this claim.”

However, “it does look like it has the promise to turn out to be true.”

Magee is an employee of Nater. Grady has been on the scientific advisory boards for Guardant Health and Freenome and has consulted for Karius.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — the results of the BESPOKE study showed.

“These findings highlight the value of utilizing ctDNA to select which patients should receive management chemotherapy and which patients can be potentially spared chemotherapy’s physical, emotional, and financial toxicities without compromising their long-term outcomes,” said first author Kim Magee of Natera, a clinical genetic testing company in Austin, Texas.

“ctDNA is emerging as the most powerful and prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer,” said Magee, who presented the findings at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

In stage II CRC, as many as 80% of patients are cured by surgery alone, while only about 5% benefit from chemotherapy. In stage III CRC, about half of patients are cured by surgery alone, while only 20% benefit from chemotherapy, and 30% recur despite chemotherapy, Magee explained.

The inability to pinpoint which patients will most benefit from chemotherapy means “we know we are needlessly treating [many] of these patients,” she said.

ctDNA Offers Insights Into Tumor’s Real-Time Status

Just as cells release fragments (cell-free DNA) into the blood as they regenerate, tumor cells also release fragments — ctDNA — which can represent a biomarker of a cancer’s current state, Magee explained.

Because the DNA fragments have a half-life of only about 2 hours, they represent a key snapshot in real time, “as opposed to imaging, which can take several weeks or months to show changes,” she said.

To determine the effects of ctDNA testing on treatment decisions and asymptomatic recurrence rates, Magee and colleagues analyzed data from the multicenter, prospective study, which used the Signatera (Natera) residual disease test.

The study included 1794 patients with resected stage II-III CRC who were treated with the standard of care between May 2020 and March 2023 who had complete clinical and laboratory data available.

ctDNA was collected 2-6 weeks post surgery and at surveillance months 2, 4, 6, and every 3 months through month 24.

Among the 1166 patients included in a final analysis, 694 (59.5%) patients received adjunctive chemotherapy, and 472 (40.5%) received no chemotherapy.

Among those with stage II CRC, a postoperative MRD positivity rate was 7.54%, while the rate in those with stage III disease was 28.35%.

Overall, 16.1% of patients had a recurrence by the trial end at 24 months.

The results showed that among patients who tested negative for ctDNA, the disease-free survival estimates were highly favorable, at 91.8% for stage II and 87.4% for stage III CRC.

Comparatively, for those who were ctDNA-positive, disease-free survival rates were just 45.9% and 35.5%, respectively, regardless of whether those patients received adjunctive chemotherapy.

At the study’s first ctDNA surveillance timepoint, patients who were ctDNA-positive with stage II and III CRC combined had substantially worse disease-free survival than patients who were ctDNA-negative (HR, 26.4; P < .0001).

Impact of Chemotherapy

Patients who were found to be MRD-positive on ctDNA testing and treated with chemotherapy had a 40.3% 2-year disease-free survival rate compared with just 24.7% among MRD-positive patients who did not receive chemotherapy.

Meanwhile, those who were MRD-negative and treated with chemotherapy had a substantially higher 2-year disease-free survival rate of 89.7% — nearly identical to the 89.5% observed in the no-chemotherapy group.

The findings underscored that “the adjuvant chemotherapy benefits were only observed among those who were ctDNA-positive,” Magee said.

“ctDNA can guide postsurgical treatment decisions by identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from chemotherapy, and in the surveillance setting, ctDNA can predict recurrence — usually ahead of scans,” she added. “This opens the opportunity to intervene and give those patients a second chance at cure.”

On the heels of major recent advances including CT, MRI, and PET-CT, “we believe that ctDNA represents the next major pivotal advancement in monitoring and eventually better understanding cancer diagnostics,” Magee said.

Commenting on the study, William M. Grady, MD, AGAF, medical director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center Gastrointestinal Cancer Prevention Clinic, Seattle, said the BESPOKE trial represents a “well-done” study, adding to research underscoring that “MRD testing is a more accurate prognostic assay than the current standards of CT scan and CEA [carcinoembryonic antigen, a tumor marker] testing.”

However, “a limitation is that this is 2 years of follow-up, [while] 5-year follow-up data would be ideal,” he said in an interview, noting, importantly, that “a small number of patients who have no evidence of disease (NED) at 2 years develop recurrence by 5 years.”

Furthermore, more research demonstrating the outcomes of MRD detection is needed, Grady added.

“A caveat is that studies are still needed showing that if you change your care of patients based on the MRD result, that you improve outcomes,” he said. “These studies are being planned and initiated at this time, from my understanding.”

Oncologists treating patients with CRC are commonly performing MRD assessment with ctDNA assays; however, Grady noted that the practice is still not the standard of care.

Regarding the suggestion of ctDNA representing the next major, pivotal step in cancer monitoring, Grady responded that “I think this is aspirational, and further studies are needed to make this claim.”

However, “it does look like it has the promise to turn out to be true.”

Magee is an employee of Nater. Grady has been on the scientific advisory boards for Guardant Health and Freenome and has consulted for Karius.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DDW 2025

SGLT2 Inhibitors Reduce Portal Hypertension From Cirrhosis

SAN DIEGO — , new research shows.

“Our study found that SGLT2 inhibitors were associated with fewer portal hypertension complications and lower mortality, suggesting they may be a valuable addition to cirrhosis management,” first author Abhinav K. Rao, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, told GI & Hepatology News.

The findings were presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Portal hypertension, a potentially life-threatening complication of cirrhosis, can be a key driver of additional complications including ascites and gastro-esophageal varices in cirrhosis.

Current treatments such as beta-blockers can prevent some complications, however, more effective therapies are needed.

SGLT2 inhibitors are often used in the treatment of cardiovascular disease as well as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH)–mediated liver disease; research is lacking regarding their effects in portal hypertension in the broader population of people with cirrhosis.

“The therapeutic efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors might be related to their ability to improve vascular function, making them attractive in portal hypertension,” Rao explained.

To investigate, Rao and colleagues evaluated data on 637,079 patients with cirrhosis in the TriNetX database, which includes patients in the United States from 66 healthcare organizations.

Patients were divided into three subgroups, including those with MASH, alcohol-associated, and other etiologies of cirrhosis.

Using robust 1:1 propensity score matching, patients in each subgroup were stratified as either having or not having been treated with SGLT2 inhibitors, limited to those who initiated the drugs within 1 year of their cirrhosis diagnosis to prevent immortal time bias. Patients were matched on other characteristics.

For the primary outcome of all-cause mortality, with an overall median follow-up of 2 years, patients prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors in the MASH cirrhosis (n = 47,385), alcohol-associated cirrhosis (n = 107,844), and other etiologies of cirrhosis (n = 59,499) groups all had a significantly lower risk for all-cause mortality than those not prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors (P < .05 for all).

SGLT2 Inhibitors in MASH Cirrhosis

Specifically looking at the MASH cirrhosis group, Rao described outcomes of the two groups of 3026 patients each who were and were not treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.

The patients had similar rates of esophageal varices (25% in the SGLT2 group and 22% in the no SGLT2 group), ascites (19% in each group), and a similar rate of 19% had hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

About 57% of patients in each treatment group used beta-blockers and 33% used glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Those with a history of liver transplantation, hemodialysis, or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement were excluded.

The secondary outcome results in those patients showed that treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors was associated with significantly reduced risks of developing portal hypertension complications including ascites, HE, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and hepatorenal syndrome (P < .05 for all).

Esophageal variceal bleeding was also reduced with SGLT-2 inhibitors; however the difference was not statistically significant.

Effects Diminished With Beta-Blocker Treatment

In a secondary analysis of patients in the MASH cirrhosis group treated with one type of a nonselective beta-blockers (n = 509) and another nonselective beta-blockers (n = 2561), the beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on portal hypertension, with the exception of HE and SBP, were found to be somewhat diminished, likely because patients were already benefitting from the beta-blockers, Rao noted.

Other Groups

In outcomes of the non–MASH-related cirrhosis groups, patients prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors also had a reduced risk for specific, as well as any portal hypertension complications (P < .05), Rao noted.

Overall, the findings add to previous studies on SGLT2 inhibitors in MASH and expand on the possible benefits, he said.

“Our findings validate these [previous] results and suggest potential benefits across for patients with other types of liver disease and raise the possibility of a beneficial effect in portal hypertension,” he said.

“Given the marked reduction in portal hypertension complications after SGLT2 inhibitor initiation, the associated survival benefit may not be surprising,” he noted.

“However, we were intrigued by the consistent reduction in portal hypertension complications across all cirrhosis types, especially since SGLT-2 inhibitors are most commonly used in patients with diabetes who have MASH-mediated liver disease.”

‘Real World Glimpse’ at SGLT2 Inhibitors; Limitations Need Noting

Commenting on the study, Rotonya M. Carr, MD, Division Head of Gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said the study sheds important light on an issue previously addressed only in smaller cohorts.

“To date, there have only been a few small prospective, retrospective, and case series studies investigating SGTL2 inhibitors in patients with cirrhosis,” she told GI & Hepatology Newsv.

“This retrospective study is a real-world glimpse at how patients with cirrhosis may fare on these drugs — very exciting data.”

Carr cautioned, however, that, in addition to the retrospective study design, limitations included that the study doesn’t provide details on the duration of therapy, preventing an understanding of whether the results represent chronic, sustained use of SGLT2 inhibitors.

“[Therefore], we cannot interpret these results to mean that chronic, sustained use of SGTL2 inh is beneficial, or does not cause harm, in patients with cirrhosis.”

“While these data are provocative, more work needs to be done before we understand the full safety and efficacy of SGTL2 inhibitors for patients with cirrhosis,” Carr added.

“However, these data are very encouraging, and I am optimistic that we will indeed see both SGTL2 inhibitors and GLP-1s among the group of medications we use in the future for the primary management of patients with liver disease.”

The authors had no disclosures to report. Carr’s disclosures included relationships with Intercept and Novo Nordisk and research funding from Merck.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — , new research shows.

“Our study found that SGLT2 inhibitors were associated with fewer portal hypertension complications and lower mortality, suggesting they may be a valuable addition to cirrhosis management,” first author Abhinav K. Rao, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, told GI & Hepatology News.

The findings were presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Portal hypertension, a potentially life-threatening complication of cirrhosis, can be a key driver of additional complications including ascites and gastro-esophageal varices in cirrhosis.

Current treatments such as beta-blockers can prevent some complications, however, more effective therapies are needed.

SGLT2 inhibitors are often used in the treatment of cardiovascular disease as well as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH)–mediated liver disease; research is lacking regarding their effects in portal hypertension in the broader population of people with cirrhosis.

“The therapeutic efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors might be related to their ability to improve vascular function, making them attractive in portal hypertension,” Rao explained.

To investigate, Rao and colleagues evaluated data on 637,079 patients with cirrhosis in the TriNetX database, which includes patients in the United States from 66 healthcare organizations.

Patients were divided into three subgroups, including those with MASH, alcohol-associated, and other etiologies of cirrhosis.

Using robust 1:1 propensity score matching, patients in each subgroup were stratified as either having or not having been treated with SGLT2 inhibitors, limited to those who initiated the drugs within 1 year of their cirrhosis diagnosis to prevent immortal time bias. Patients were matched on other characteristics.

For the primary outcome of all-cause mortality, with an overall median follow-up of 2 years, patients prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors in the MASH cirrhosis (n = 47,385), alcohol-associated cirrhosis (n = 107,844), and other etiologies of cirrhosis (n = 59,499) groups all had a significantly lower risk for all-cause mortality than those not prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors (P < .05 for all).

SGLT2 Inhibitors in MASH Cirrhosis

Specifically looking at the MASH cirrhosis group, Rao described outcomes of the two groups of 3026 patients each who were and were not treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.

The patients had similar rates of esophageal varices (25% in the SGLT2 group and 22% in the no SGLT2 group), ascites (19% in each group), and a similar rate of 19% had hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

About 57% of patients in each treatment group used beta-blockers and 33% used glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Those with a history of liver transplantation, hemodialysis, or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement were excluded.

The secondary outcome results in those patients showed that treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors was associated with significantly reduced risks of developing portal hypertension complications including ascites, HE, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and hepatorenal syndrome (P < .05 for all).

Esophageal variceal bleeding was also reduced with SGLT-2 inhibitors; however the difference was not statistically significant.

Effects Diminished With Beta-Blocker Treatment

In a secondary analysis of patients in the MASH cirrhosis group treated with one type of a nonselective beta-blockers (n = 509) and another nonselective beta-blockers (n = 2561), the beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on portal hypertension, with the exception of HE and SBP, were found to be somewhat diminished, likely because patients were already benefitting from the beta-blockers, Rao noted.

Other Groups

In outcomes of the non–MASH-related cirrhosis groups, patients prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors also had a reduced risk for specific, as well as any portal hypertension complications (P < .05), Rao noted.

Overall, the findings add to previous studies on SGLT2 inhibitors in MASH and expand on the possible benefits, he said.

“Our findings validate these [previous] results and suggest potential benefits across for patients with other types of liver disease and raise the possibility of a beneficial effect in portal hypertension,” he said.

“Given the marked reduction in portal hypertension complications after SGLT2 inhibitor initiation, the associated survival benefit may not be surprising,” he noted.

“However, we were intrigued by the consistent reduction in portal hypertension complications across all cirrhosis types, especially since SGLT-2 inhibitors are most commonly used in patients with diabetes who have MASH-mediated liver disease.”

‘Real World Glimpse’ at SGLT2 Inhibitors; Limitations Need Noting

Commenting on the study, Rotonya M. Carr, MD, Division Head of Gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said the study sheds important light on an issue previously addressed only in smaller cohorts.

“To date, there have only been a few small prospective, retrospective, and case series studies investigating SGTL2 inhibitors in patients with cirrhosis,” she told GI & Hepatology Newsv.

“This retrospective study is a real-world glimpse at how patients with cirrhosis may fare on these drugs — very exciting data.”

Carr cautioned, however, that, in addition to the retrospective study design, limitations included that the study doesn’t provide details on the duration of therapy, preventing an understanding of whether the results represent chronic, sustained use of SGLT2 inhibitors.

“[Therefore], we cannot interpret these results to mean that chronic, sustained use of SGTL2 inh is beneficial, or does not cause harm, in patients with cirrhosis.”

“While these data are provocative, more work needs to be done before we understand the full safety and efficacy of SGTL2 inhibitors for patients with cirrhosis,” Carr added.

“However, these data are very encouraging, and I am optimistic that we will indeed see both SGTL2 inhibitors and GLP-1s among the group of medications we use in the future for the primary management of patients with liver disease.”

The authors had no disclosures to report. Carr’s disclosures included relationships with Intercept and Novo Nordisk and research funding from Merck.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — , new research shows.

“Our study found that SGLT2 inhibitors were associated with fewer portal hypertension complications and lower mortality, suggesting they may be a valuable addition to cirrhosis management,” first author Abhinav K. Rao, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, told GI & Hepatology News.

The findings were presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Portal hypertension, a potentially life-threatening complication of cirrhosis, can be a key driver of additional complications including ascites and gastro-esophageal varices in cirrhosis.

Current treatments such as beta-blockers can prevent some complications, however, more effective therapies are needed.

SGLT2 inhibitors are often used in the treatment of cardiovascular disease as well as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH)–mediated liver disease; research is lacking regarding their effects in portal hypertension in the broader population of people with cirrhosis.

“The therapeutic efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors might be related to their ability to improve vascular function, making them attractive in portal hypertension,” Rao explained.

To investigate, Rao and colleagues evaluated data on 637,079 patients with cirrhosis in the TriNetX database, which includes patients in the United States from 66 healthcare organizations.

Patients were divided into three subgroups, including those with MASH, alcohol-associated, and other etiologies of cirrhosis.

Using robust 1:1 propensity score matching, patients in each subgroup were stratified as either having or not having been treated with SGLT2 inhibitors, limited to those who initiated the drugs within 1 year of their cirrhosis diagnosis to prevent immortal time bias. Patients were matched on other characteristics.

For the primary outcome of all-cause mortality, with an overall median follow-up of 2 years, patients prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors in the MASH cirrhosis (n = 47,385), alcohol-associated cirrhosis (n = 107,844), and other etiologies of cirrhosis (n = 59,499) groups all had a significantly lower risk for all-cause mortality than those not prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors (P < .05 for all).

SGLT2 Inhibitors in MASH Cirrhosis

Specifically looking at the MASH cirrhosis group, Rao described outcomes of the two groups of 3026 patients each who were and were not treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.

The patients had similar rates of esophageal varices (25% in the SGLT2 group and 22% in the no SGLT2 group), ascites (19% in each group), and a similar rate of 19% had hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

About 57% of patients in each treatment group used beta-blockers and 33% used glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Those with a history of liver transplantation, hemodialysis, or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement were excluded.

The secondary outcome results in those patients showed that treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors was associated with significantly reduced risks of developing portal hypertension complications including ascites, HE, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and hepatorenal syndrome (P < .05 for all).

Esophageal variceal bleeding was also reduced with SGLT-2 inhibitors; however the difference was not statistically significant.

Effects Diminished With Beta-Blocker Treatment

In a secondary analysis of patients in the MASH cirrhosis group treated with one type of a nonselective beta-blockers (n = 509) and another nonselective beta-blockers (n = 2561), the beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on portal hypertension, with the exception of HE and SBP, were found to be somewhat diminished, likely because patients were already benefitting from the beta-blockers, Rao noted.

Other Groups

In outcomes of the non–MASH-related cirrhosis groups, patients prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors also had a reduced risk for specific, as well as any portal hypertension complications (P < .05), Rao noted.

Overall, the findings add to previous studies on SGLT2 inhibitors in MASH and expand on the possible benefits, he said.

“Our findings validate these [previous] results and suggest potential benefits across for patients with other types of liver disease and raise the possibility of a beneficial effect in portal hypertension,” he said.

“Given the marked reduction in portal hypertension complications after SGLT2 inhibitor initiation, the associated survival benefit may not be surprising,” he noted.

“However, we were intrigued by the consistent reduction in portal hypertension complications across all cirrhosis types, especially since SGLT-2 inhibitors are most commonly used in patients with diabetes who have MASH-mediated liver disease.”

‘Real World Glimpse’ at SGLT2 Inhibitors; Limitations Need Noting

Commenting on the study, Rotonya M. Carr, MD, Division Head of Gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said the study sheds important light on an issue previously addressed only in smaller cohorts.

“To date, there have only been a few small prospective, retrospective, and case series studies investigating SGTL2 inhibitors in patients with cirrhosis,” she told GI & Hepatology Newsv.

“This retrospective study is a real-world glimpse at how patients with cirrhosis may fare on these drugs — very exciting data.”

Carr cautioned, however, that, in addition to the retrospective study design, limitations included that the study doesn’t provide details on the duration of therapy, preventing an understanding of whether the results represent chronic, sustained use of SGLT2 inhibitors.

“[Therefore], we cannot interpret these results to mean that chronic, sustained use of SGTL2 inh is beneficial, or does not cause harm, in patients with cirrhosis.”

“While these data are provocative, more work needs to be done before we understand the full safety and efficacy of SGTL2 inhibitors for patients with cirrhosis,” Carr added.

“However, these data are very encouraging, and I am optimistic that we will indeed see both SGTL2 inhibitors and GLP-1s among the group of medications we use in the future for the primary management of patients with liver disease.”

The authors had no disclosures to report. Carr’s disclosures included relationships with Intercept and Novo Nordisk and research funding from Merck.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DDW 2025

AI-Enhanced Digital Collaborative Care Improves IBS Symptoms

SAN DIEGO — seen at Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, an observational study found.

Symptom tracking at 4-week intervals showed that “almost everybody got better” regardless of IBS subtype, with relief starting in the first 4 weeks, Stephen Lupe, PsyD, gastrointestinal psychologist and director of Behavioral Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, said in an interview with GI & Hepatology News.

The findings were presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Digital Boost to Collaborative Care Model

The combination of dietary interventions and brain-gut behavioral therapy has demonstrated excellent outcomes for patients with IBS, but patients struggle to access these needed services, Lupe noted. A medical home collaborative care model in which patients get care from a multidisciplinary team has been shown to be a good way to successfully deliver this combination of care.

“When you do collaborative in-person care, people get better quicker,” Lupe said.

However, scaling access to this model remains a challenge. For their study, Cleveland Clinic researchers added an AI-enhanced digital platform, Ayble Health, to the in-person collaborative care model to expand access to disease-management services and evaluated whether it improved clinical outcomes for study’s 171 participants, who were recruited via social media advertisements.

Here’s how the platform works. Once a patient enrolls in Ayble Health, a personalized care plan is recommended based on a virtual visit, screening questionnaire, and baseline survey.

The platform includes brain-gut programs, including guided audio content on mindfulness, hypnosis, meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and breathing techniques; personalized nutrition support to find and remove trigger foods, a food barcode scanner, and a comprehensive groceries database; and AI-powered wellness tools to help manage and track symptoms. Lupe worked with Ayble Health to develop the platform’s behavioral health content and care pathways.

Patients may choose to follow any combination of three care pathways: A care team overseen by gastro-psychologists, dietitians, and gastroenterologists; a holistic nutrition program including a personalized elimination diet; and a brain-gut behavioral therapy program with gut-directed hypnosis, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy. They go at their own pace, can connect with Ayble Health’s virtual care team to help with education and goal setting, and continue to consult their Cleveland Clinic providers as needed for evaluation and treatment.

“The care team is still there. We’ve just augmented it to make sure that as many people as possible get behavioral skills training and dietary support, with monitoring between visits — instead of the traditional, ‘I’ll see you in 6 months approach,” Lupe explained.

IBS Symptom Scores Improve

Of the study’s 171 patients, 20 had IBS-diarrhea, 23 had IBS-constipation, 32 had IBS-mixed, and 8 had IBS-unspecified. The remaining 88 patients reported IBS without indication of subtype.

At intake, all patients had active IBS symptoms, with scores ≥ 75 on the IBS symptom severity scale (IBS-SSS). Most patients enrolled in more than one care pathway, and 95% of participants completed at least 4 weeks on their chosen pathways.

Overall, patients saw an average 140-point decrease in IBS-SSS from intake through follow-up lasting up to 42 weeks. A drop in IBS-SSS score ≥ 50 points was considered a clinically meaningful change.

Symptom improvements occurred as early as week 4, were sustained and were uniform across IBS subtypes, suggesting that the AI-enhanced digital collaborative care model has wide utility in patients with IBS, Lupe said.

Patients with the most severe IBS symptoms showed the greatest improvement, but even 50% of those with mild symptoms had clinically meaningful changes in IBS-SSS.

Improvement in IBS symptoms was seen across all care pathways, but the combination of multiple pathways improved outcomes better than a single care pathway alone. The combination of nutrition and brain-gut behavioral therapy demonstrated the greatest reduction in IBS-SSS scores and proportion of patients achieving clinically meaningful results (95%).

The digital comprehensive car model for IBS is now “up and running” at Cleveland Clinic, and the team plans to proactively reach out to patients with gastrointestinal disorders recently seen at their center to alert them to the availability of this tool, Lupe said.

A randomized controlled trial is planned to further validate these observational findings, he added.

‘Wave of the Future’

The digital collaborative care model is “innovative, and I think is the wave of the future,” Kyle Staller, MD, MPH, gastroenterologist and director of the Gastrointestinal Motility Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who wasn’t involved in the study, told GI & Hepatology News.

“These digital platforms bundle nondrug options, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary therapy, hypnotherapy, so patients can choose what suits them, rather than the gastroenterologist hunting down each individual resource, which requires a lot of work,” Staller said.

The study “provides real-world evidence that a deliberative, digital, collaborative care model that houses various types of nondrug IBS treatment under one roof can provide meaningful benefit to patients,” Staller told GI & Hepatology News.

Importantly, he said, “patients chose which option they wanted. At the end of the day, the way that we should be thinking about IBS care is really making sure that we engage the patient with treatment choices,” Staller said.

This study had no specific funding. Three authors had relationships with Ayble Health. Lupe is a scientific advisor for Boomerang Health and paid lecturer for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Staller disclosed having relationships with Mahana Therapeutics, Ardelyx Inc, Gemelli Biotech, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — seen at Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, an observational study found.

Symptom tracking at 4-week intervals showed that “almost everybody got better” regardless of IBS subtype, with relief starting in the first 4 weeks, Stephen Lupe, PsyD, gastrointestinal psychologist and director of Behavioral Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, said in an interview with GI & Hepatology News.

The findings were presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Digital Boost to Collaborative Care Model

The combination of dietary interventions and brain-gut behavioral therapy has demonstrated excellent outcomes for patients with IBS, but patients struggle to access these needed services, Lupe noted. A medical home collaborative care model in which patients get care from a multidisciplinary team has been shown to be a good way to successfully deliver this combination of care.

“When you do collaborative in-person care, people get better quicker,” Lupe said.

However, scaling access to this model remains a challenge. For their study, Cleveland Clinic researchers added an AI-enhanced digital platform, Ayble Health, to the in-person collaborative care model to expand access to disease-management services and evaluated whether it improved clinical outcomes for study’s 171 participants, who were recruited via social media advertisements.

Here’s how the platform works. Once a patient enrolls in Ayble Health, a personalized care plan is recommended based on a virtual visit, screening questionnaire, and baseline survey.

The platform includes brain-gut programs, including guided audio content on mindfulness, hypnosis, meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and breathing techniques; personalized nutrition support to find and remove trigger foods, a food barcode scanner, and a comprehensive groceries database; and AI-powered wellness tools to help manage and track symptoms. Lupe worked with Ayble Health to develop the platform’s behavioral health content and care pathways.

Patients may choose to follow any combination of three care pathways: A care team overseen by gastro-psychologists, dietitians, and gastroenterologists; a holistic nutrition program including a personalized elimination diet; and a brain-gut behavioral therapy program with gut-directed hypnosis, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy. They go at their own pace, can connect with Ayble Health’s virtual care team to help with education and goal setting, and continue to consult their Cleveland Clinic providers as needed for evaluation and treatment.

“The care team is still there. We’ve just augmented it to make sure that as many people as possible get behavioral skills training and dietary support, with monitoring between visits — instead of the traditional, ‘I’ll see you in 6 months approach,” Lupe explained.

IBS Symptom Scores Improve

Of the study’s 171 patients, 20 had IBS-diarrhea, 23 had IBS-constipation, 32 had IBS-mixed, and 8 had IBS-unspecified. The remaining 88 patients reported IBS without indication of subtype.

At intake, all patients had active IBS symptoms, with scores ≥ 75 on the IBS symptom severity scale (IBS-SSS). Most patients enrolled in more than one care pathway, and 95% of participants completed at least 4 weeks on their chosen pathways.

Overall, patients saw an average 140-point decrease in IBS-SSS from intake through follow-up lasting up to 42 weeks. A drop in IBS-SSS score ≥ 50 points was considered a clinically meaningful change.

Symptom improvements occurred as early as week 4, were sustained and were uniform across IBS subtypes, suggesting that the AI-enhanced digital collaborative care model has wide utility in patients with IBS, Lupe said.

Patients with the most severe IBS symptoms showed the greatest improvement, but even 50% of those with mild symptoms had clinically meaningful changes in IBS-SSS.

Improvement in IBS symptoms was seen across all care pathways, but the combination of multiple pathways improved outcomes better than a single care pathway alone. The combination of nutrition and brain-gut behavioral therapy demonstrated the greatest reduction in IBS-SSS scores and proportion of patients achieving clinically meaningful results (95%).

The digital comprehensive car model for IBS is now “up and running” at Cleveland Clinic, and the team plans to proactively reach out to patients with gastrointestinal disorders recently seen at their center to alert them to the availability of this tool, Lupe said.

A randomized controlled trial is planned to further validate these observational findings, he added.

‘Wave of the Future’

The digital collaborative care model is “innovative, and I think is the wave of the future,” Kyle Staller, MD, MPH, gastroenterologist and director of the Gastrointestinal Motility Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who wasn’t involved in the study, told GI & Hepatology News.

“These digital platforms bundle nondrug options, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary therapy, hypnotherapy, so patients can choose what suits them, rather than the gastroenterologist hunting down each individual resource, which requires a lot of work,” Staller said.

The study “provides real-world evidence that a deliberative, digital, collaborative care model that houses various types of nondrug IBS treatment under one roof can provide meaningful benefit to patients,” Staller told GI & Hepatology News.

Importantly, he said, “patients chose which option they wanted. At the end of the day, the way that we should be thinking about IBS care is really making sure that we engage the patient with treatment choices,” Staller said.

This study had no specific funding. Three authors had relationships with Ayble Health. Lupe is a scientific advisor for Boomerang Health and paid lecturer for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Staller disclosed having relationships with Mahana Therapeutics, Ardelyx Inc, Gemelli Biotech, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — seen at Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, an observational study found.

Symptom tracking at 4-week intervals showed that “almost everybody got better” regardless of IBS subtype, with relief starting in the first 4 weeks, Stephen Lupe, PsyD, gastrointestinal psychologist and director of Behavioral Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, said in an interview with GI & Hepatology News.

The findings were presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

Digital Boost to Collaborative Care Model

The combination of dietary interventions and brain-gut behavioral therapy has demonstrated excellent outcomes for patients with IBS, but patients struggle to access these needed services, Lupe noted. A medical home collaborative care model in which patients get care from a multidisciplinary team has been shown to be a good way to successfully deliver this combination of care.

“When you do collaborative in-person care, people get better quicker,” Lupe said.

However, scaling access to this model remains a challenge. For their study, Cleveland Clinic researchers added an AI-enhanced digital platform, Ayble Health, to the in-person collaborative care model to expand access to disease-management services and evaluated whether it improved clinical outcomes for study’s 171 participants, who were recruited via social media advertisements.

Here’s how the platform works. Once a patient enrolls in Ayble Health, a personalized care plan is recommended based on a virtual visit, screening questionnaire, and baseline survey.

The platform includes brain-gut programs, including guided audio content on mindfulness, hypnosis, meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and breathing techniques; personalized nutrition support to find and remove trigger foods, a food barcode scanner, and a comprehensive groceries database; and AI-powered wellness tools to help manage and track symptoms. Lupe worked with Ayble Health to develop the platform’s behavioral health content and care pathways.

Patients may choose to follow any combination of three care pathways: A care team overseen by gastro-psychologists, dietitians, and gastroenterologists; a holistic nutrition program including a personalized elimination diet; and a brain-gut behavioral therapy program with gut-directed hypnosis, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy. They go at their own pace, can connect with Ayble Health’s virtual care team to help with education and goal setting, and continue to consult their Cleveland Clinic providers as needed for evaluation and treatment.

“The care team is still there. We’ve just augmented it to make sure that as many people as possible get behavioral skills training and dietary support, with monitoring between visits — instead of the traditional, ‘I’ll see you in 6 months approach,” Lupe explained.

IBS Symptom Scores Improve

Of the study’s 171 patients, 20 had IBS-diarrhea, 23 had IBS-constipation, 32 had IBS-mixed, and 8 had IBS-unspecified. The remaining 88 patients reported IBS without indication of subtype.

At intake, all patients had active IBS symptoms, with scores ≥ 75 on the IBS symptom severity scale (IBS-SSS). Most patients enrolled in more than one care pathway, and 95% of participants completed at least 4 weeks on their chosen pathways.

Overall, patients saw an average 140-point decrease in IBS-SSS from intake through follow-up lasting up to 42 weeks. A drop in IBS-SSS score ≥ 50 points was considered a clinically meaningful change.

Symptom improvements occurred as early as week 4, were sustained and were uniform across IBS subtypes, suggesting that the AI-enhanced digital collaborative care model has wide utility in patients with IBS, Lupe said.

Patients with the most severe IBS symptoms showed the greatest improvement, but even 50% of those with mild symptoms had clinically meaningful changes in IBS-SSS.

Improvement in IBS symptoms was seen across all care pathways, but the combination of multiple pathways improved outcomes better than a single care pathway alone. The combination of nutrition and brain-gut behavioral therapy demonstrated the greatest reduction in IBS-SSS scores and proportion of patients achieving clinically meaningful results (95%).

The digital comprehensive car model for IBS is now “up and running” at Cleveland Clinic, and the team plans to proactively reach out to patients with gastrointestinal disorders recently seen at their center to alert them to the availability of this tool, Lupe said.

A randomized controlled trial is planned to further validate these observational findings, he added.

‘Wave of the Future’

The digital collaborative care model is “innovative, and I think is the wave of the future,” Kyle Staller, MD, MPH, gastroenterologist and director of the Gastrointestinal Motility Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who wasn’t involved in the study, told GI & Hepatology News.

“These digital platforms bundle nondrug options, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary therapy, hypnotherapy, so patients can choose what suits them, rather than the gastroenterologist hunting down each individual resource, which requires a lot of work,” Staller said.

The study “provides real-world evidence that a deliberative, digital, collaborative care model that houses various types of nondrug IBS treatment under one roof can provide meaningful benefit to patients,” Staller told GI & Hepatology News.

Importantly, he said, “patients chose which option they wanted. At the end of the day, the way that we should be thinking about IBS care is really making sure that we engage the patient with treatment choices,” Staller said.

This study had no specific funding. Three authors had relationships with Ayble Health. Lupe is a scientific advisor for Boomerang Health and paid lecturer for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Staller disclosed having relationships with Mahana Therapeutics, Ardelyx Inc, Gemelli Biotech, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DDW 2025

Advances in Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Advances in Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

- Vantanasiri K, Kamboj AK, Kisiel JB, Iyer PG. Advances in Screening for Barrett Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2024;99(3):459-473. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.014

- Cancer Stat Facts: Esophageal Cancer. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html

- Seer*Explorer: Esophagus. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html

- Kolb JM, Chen M, Tavakkoli A, et al. Understanding Compliance, Practice Patterns, and Barriers Among Gastroenterologists and Primary Care Providers Is Crucial for Developing Strategies to Improve Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1568-1573.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.003

- Kunzmann AT, Thrift AP, Cardwell CR, et al. Model for Identifying Individuals at Risk for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1229-1236.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.014

- Rubenstein JH, Evans RR, Burns JA, et al. Patients With Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Esophagogastric Junction Frequently Have Potential Screening Opportunities. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1349-1351.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.255

- Xie S-H, Ness-Jensen E, Medefelt N, Lagergren J. Assessing the feasibility of targeted screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma based on individual risk assessment in a population-based cohort study in Norway (The HUNT Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):829-835. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0069-9

- Rubenstein JH, Fontaine S, MacDonald PW, et al. Predicting Incident Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Gastric Cardia Using Machine Learning of Electronic Health Records. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(6):1420-1429.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.011

- Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):333-344. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31099-0

- Moinova HR, Verma S, Dumot J, et al. Multicenter, Prospective Trial of Nonendoscopic

Biomarker-Driven Detection of Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119(11):2206-2214. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002850 - Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680

- ASGE STANDARDS OF PRACTICE COMMITTEE; Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(3):335-359.e2. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.012

- Muthusamy VR, Wani S, Gyawali CP, Komanduri S. CGIT Barrett’s Esophagus Consensus Conference Participants. AGA Clinical Practice Update on New Technology and Innovation for Surveillance and Screening in Barrett’s Esophagus: Expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(12):2696-2706. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.06.003

- Xie SH, Lagergren J. A model for predicting individuals’ absolute risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: Moving toward tailored screening and prevention. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(12):2813-2819. doi:10.1002/ijc.29988

- Rubenstein JH, McConnell D, Waljee AK, et al. Validation and Comparison of Tools for Selecting Individuals to Screen for Barrett’s Esophagus and Early Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2082-2092. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.037

- Iyer PG, Sachdeva K, Leggett CL, et al. Development of Electronic Health Record–Based Machine Learning Models to Predict Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Risk. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023;14(10):e00637. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000637

- Ross-Innes CS, Debiram-Beecham I, O’Donovan M, et al; BEST2 Study Group. Evaluation of a minimally invasive cell sampling device coupled with assessment of trefoil factor 3 expression for diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus: a multicenter case-control study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(1):e1001780. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001780

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

- Vantanasiri K, Kamboj AK, Kisiel JB, Iyer PG. Advances in Screening for Barrett Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2024;99(3):459-473. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.014

- Cancer Stat Facts: Esophageal Cancer. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html

- Seer*Explorer: Esophagus. NIH National Cancer Institute: Survival, Epidemiology, and End Results Program web site. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html

- Kolb JM, Chen M, Tavakkoli A, et al. Understanding Compliance, Practice Patterns, and Barriers Among Gastroenterologists and Primary Care Providers Is Crucial for Developing Strategies to Improve Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1568-1573.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.003

- Kunzmann AT, Thrift AP, Cardwell CR, et al. Model for Identifying Individuals at Risk for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1229-1236.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.014

- Rubenstein JH, Evans RR, Burns JA, et al. Patients With Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Esophagogastric Junction Frequently Have Potential Screening Opportunities. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(4):1349-1351.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.255

- Xie S-H, Ness-Jensen E, Medefelt N, Lagergren J. Assessing the feasibility of targeted screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma based on individual risk assessment in a population-based cohort study in Norway (The HUNT Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):829-835. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0069-9

- Rubenstein JH, Fontaine S, MacDonald PW, et al. Predicting Incident Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus or Gastric Cardia Using Machine Learning of Electronic Health Records. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(6):1420-1429.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.011

- Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):333-344. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31099-0