User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations, culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the USMLE Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

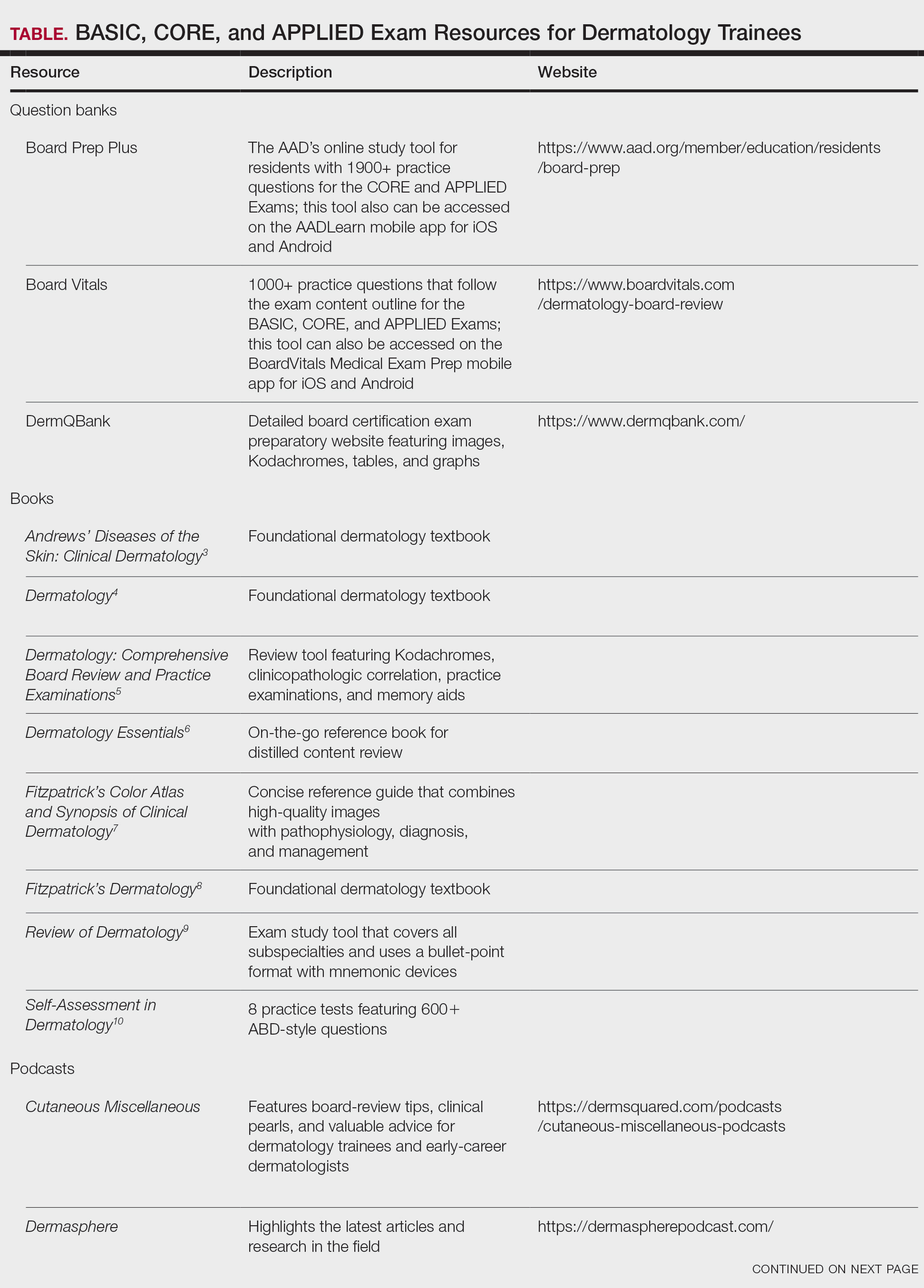

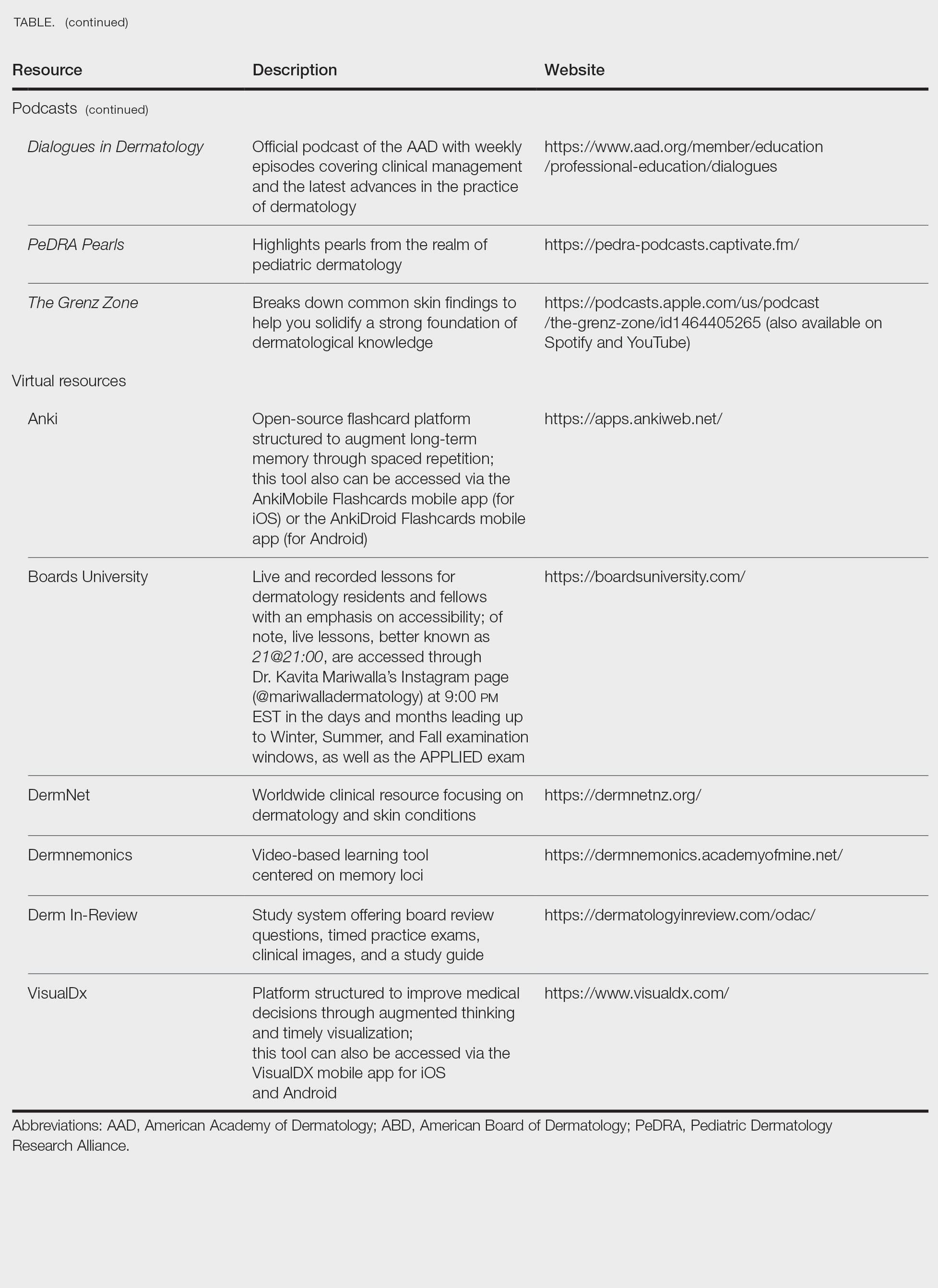

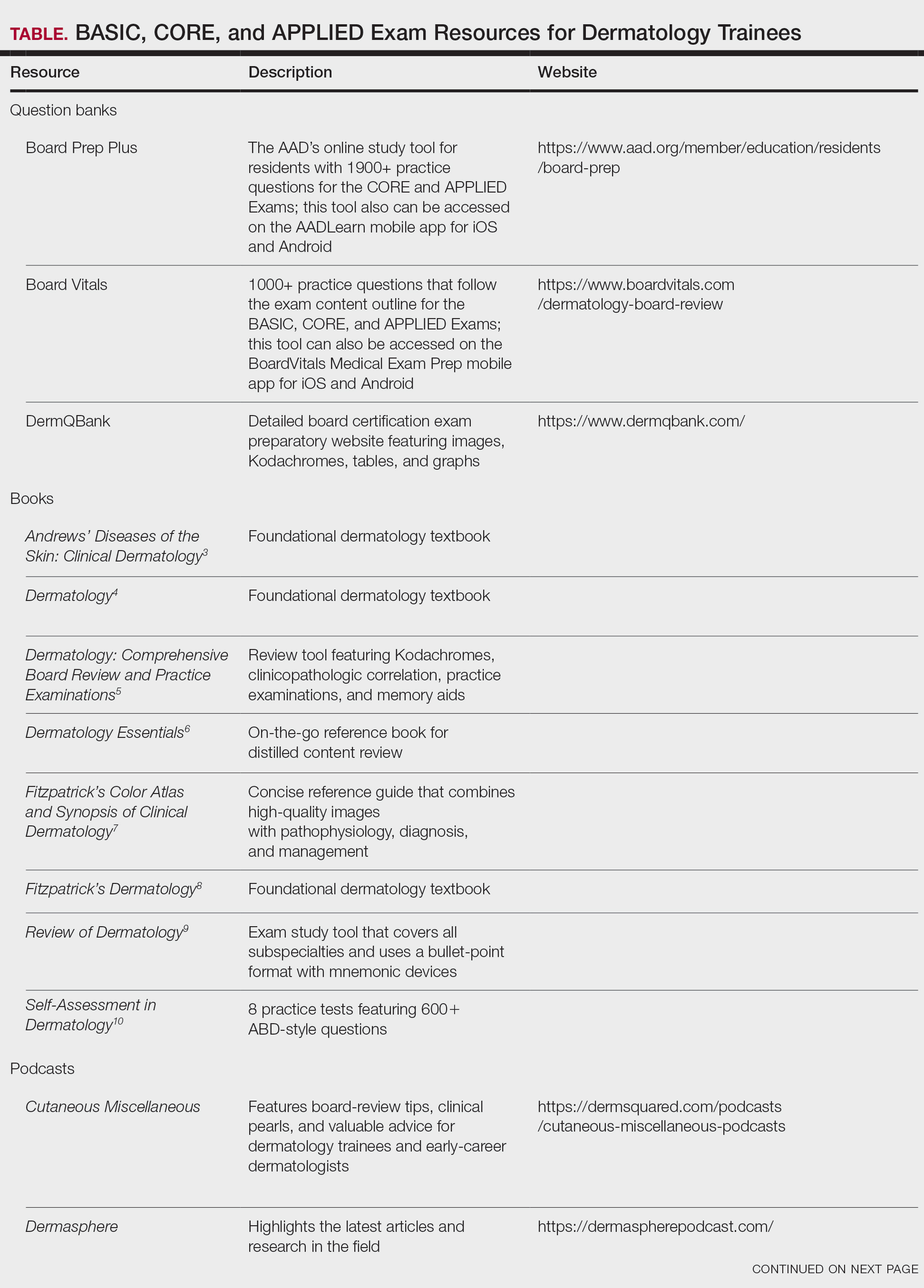

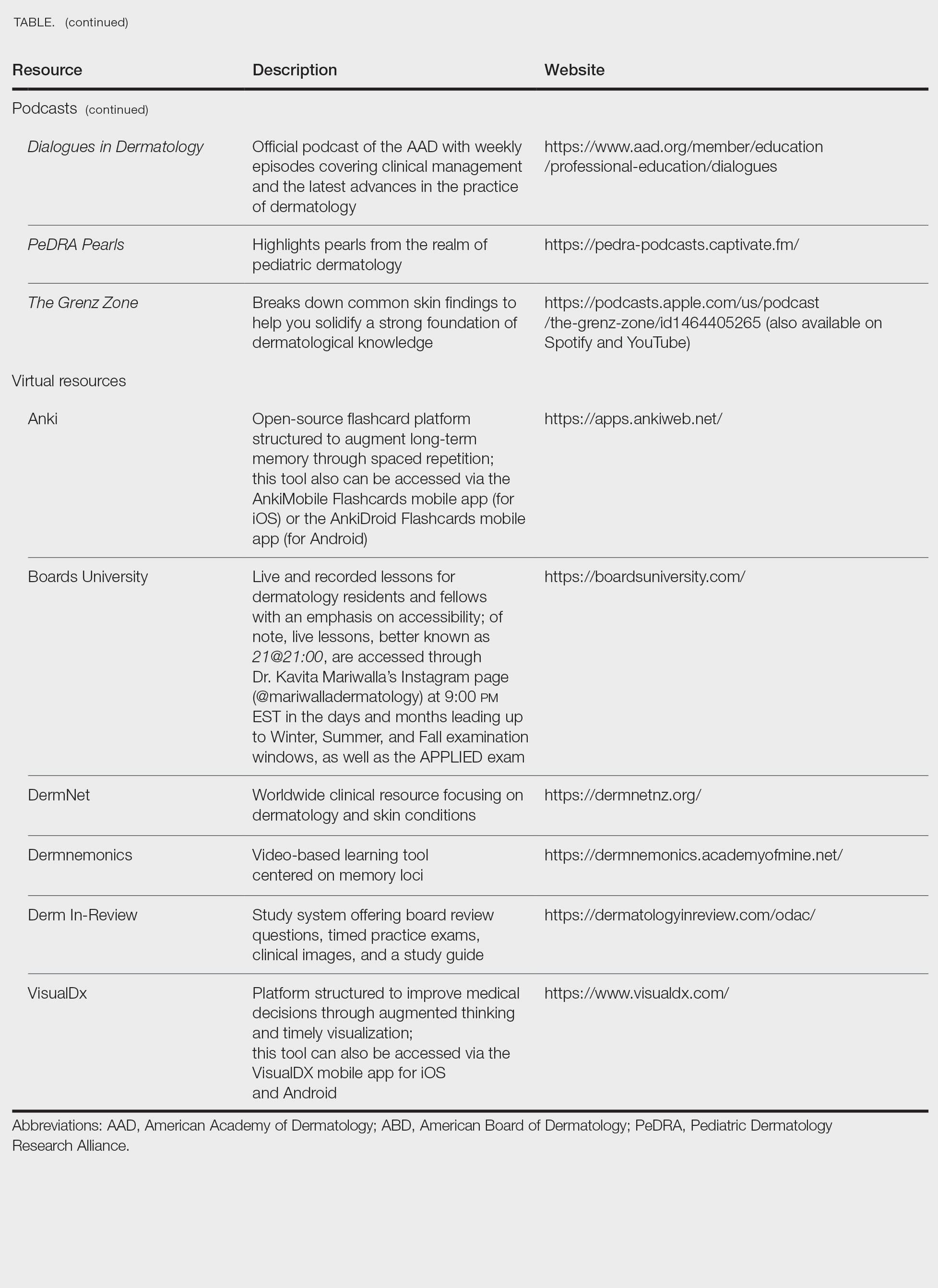

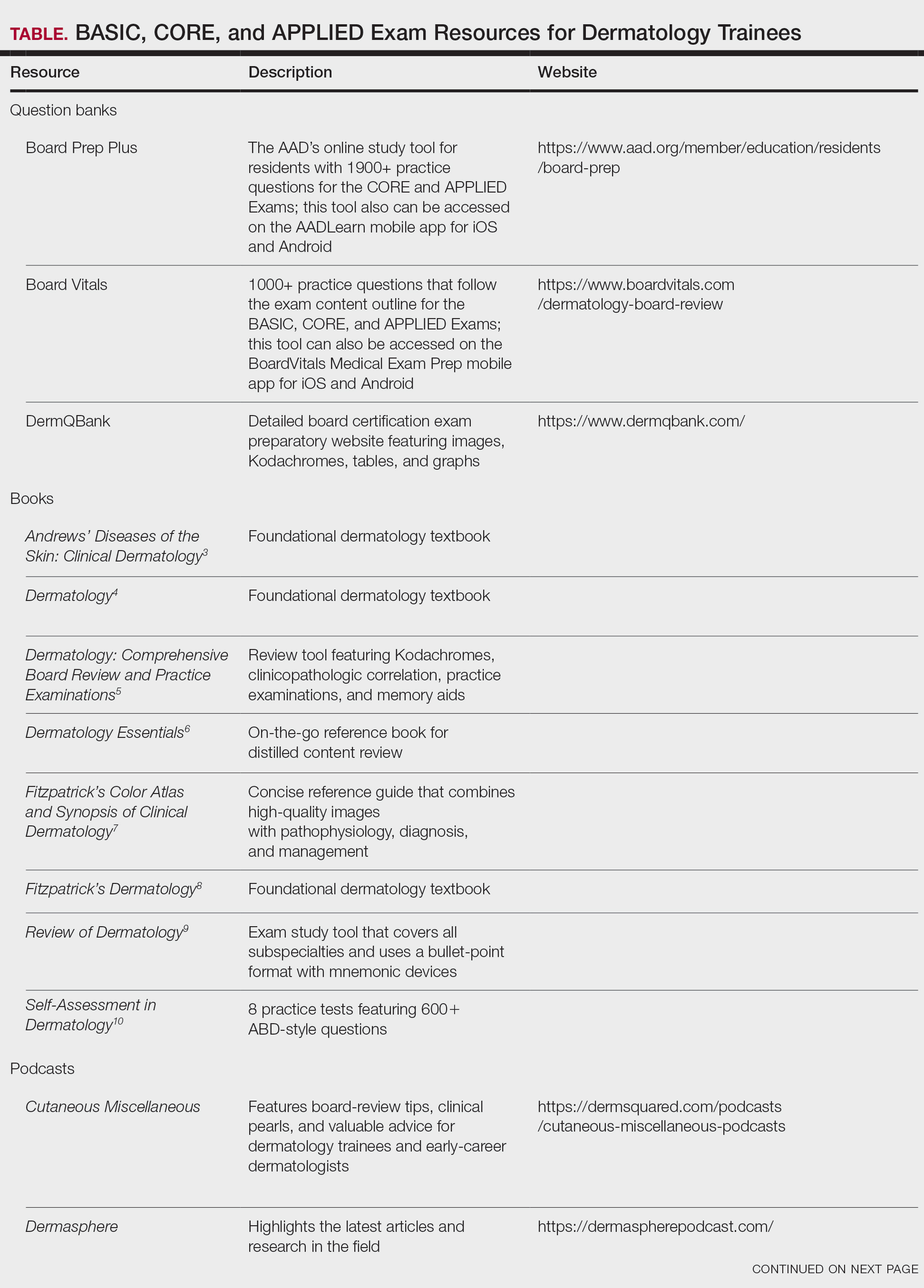

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside of clinical responsibilities (Table). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for additional ones to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you can also consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18

Never forget that you have already come this far; trust in your journey and remember what is meant for you will not miss you. Juggling 6 exams during residency alongside clinical and personal responsibilities is no small feat. With a strong study plan and smart test-day strategies, I have no doubt you will become a board-certified dermatologist!

- ABD certification pathway info center. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/abd-certification-pathway/abd-certification-pathway-info-center

- American Board of Dermatology. General exam information. Accessed January 13, 2026. https://www.abderm.org/exams/general-exam-information

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nelson KC, Cerroni L, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology: Comprehensive Board Review and Practice Examinations. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Saavedra AP, Kang S, Amagai M, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TL, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2017.

- Leventhal JS, Levy LL. Self-Assessment in Dermatology: Questions and Answers. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2024.

- Association of Academic Cosmetic Dermatology. Resources for dermatology residents. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://theaacd.org/resident-resources/

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.12.007

- Shabeeb N. Dermatology resident education for skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106:E18-E20. doi:10.12788/cutis.0099

- Azhar AF. Review of 3 comprehensive Anki flash card decks for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2023;112:E10-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0813

- ODAC Dermatology. Derm In-Review. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://dermatologyinreview.com/odac/

- American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification testing with Pearson VUE. Accessed October 19, 2025. https://www.pearsonvue.com/us/en/abd.html

- Lim YH. Transitioning from an intern to a dermatology resident. Cutis. 2022;110:E14-E16. doi:10.12788/cutis.0638

- Lim YH. Prioritizing mental health in residency. Cutis. 2022;109:E36-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0551

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations, culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the USMLE Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside of clinical responsibilities (Table). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for additional ones to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you can also consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18

Never forget that you have already come this far; trust in your journey and remember what is meant for you will not miss you. Juggling 6 exams during residency alongside clinical and personal responsibilities is no small feat. With a strong study plan and smart test-day strategies, I have no doubt you will become a board-certified dermatologist!

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations, culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the USMLE Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside of clinical responsibilities (Table). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for additional ones to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you can also consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18

Never forget that you have already come this far; trust in your journey and remember what is meant for you will not miss you. Juggling 6 exams during residency alongside clinical and personal responsibilities is no small feat. With a strong study plan and smart test-day strategies, I have no doubt you will become a board-certified dermatologist!

- ABD certification pathway info center. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/abd-certification-pathway/abd-certification-pathway-info-center

- American Board of Dermatology. General exam information. Accessed January 13, 2026. https://www.abderm.org/exams/general-exam-information

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nelson KC, Cerroni L, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology: Comprehensive Board Review and Practice Examinations. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Saavedra AP, Kang S, Amagai M, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TL, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2017.

- Leventhal JS, Levy LL. Self-Assessment in Dermatology: Questions and Answers. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2024.

- Association of Academic Cosmetic Dermatology. Resources for dermatology residents. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://theaacd.org/resident-resources/

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.12.007

- Shabeeb N. Dermatology resident education for skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106:E18-E20. doi:10.12788/cutis.0099

- Azhar AF. Review of 3 comprehensive Anki flash card decks for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2023;112:E10-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0813

- ODAC Dermatology. Derm In-Review. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://dermatologyinreview.com/odac/

- American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification testing with Pearson VUE. Accessed October 19, 2025. https://www.pearsonvue.com/us/en/abd.html

- Lim YH. Transitioning from an intern to a dermatology resident. Cutis. 2022;110:E14-E16. doi:10.12788/cutis.0638

- Lim YH. Prioritizing mental health in residency. Cutis. 2022;109:E36-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0551

- ABD certification pathway info center. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/abd-certification-pathway/abd-certification-pathway-info-center

- American Board of Dermatology. General exam information. Accessed January 13, 2026. https://www.abderm.org/exams/general-exam-information

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nelson KC, Cerroni L, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology: Comprehensive Board Review and Practice Examinations. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Saavedra AP, Kang S, Amagai M, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TL, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2017.

- Leventhal JS, Levy LL. Self-Assessment in Dermatology: Questions and Answers. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2024.

- Association of Academic Cosmetic Dermatology. Resources for dermatology residents. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://theaacd.org/resident-resources/

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.12.007

- Shabeeb N. Dermatology resident education for skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106:E18-E20. doi:10.12788/cutis.0099

- Azhar AF. Review of 3 comprehensive Anki flash card decks for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2023;112:E10-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0813

- ODAC Dermatology. Derm In-Review. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://dermatologyinreview.com/odac/

- American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification testing with Pearson VUE. Accessed October 19, 2025. https://www.pearsonvue.com/us/en/abd.html

- Lim YH. Transitioning from an intern to a dermatology resident. Cutis. 2022;110:E14-E16. doi:10.12788/cutis.0638

- Lim YH. Prioritizing mental health in residency. Cutis. 2022;109:E36-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0551

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Practice Points

- To become a board-certified dermatologist, one must complete the American Board of Dermatology Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, followed by 4 CORE Exam modules and a final APPLIED Exam following residency completion.

- When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore fully. With so many options available, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style.

- A comprehensive study strategy begins during your first year of residency and appropriately intensifies in the months leading up to the exams. Make sure to cultivate test day strategies to help you stay calm, focused, and in the zone.

Comprehensive Patch Testing: An Essential Tool for Care of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Comprehensive Patch Testing: An Essential Tool for Care of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common skin condition affecting approximately 20% of the general population in the United States.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a unique disease in that there is an opportunity for complete cure through allergen avoidance; however, this requires proper identification of the offending allergen. When the culprit allergen is not identified or removed from the patient’s environment, chronic ACD can develop, leading to persistent inflammation and related symptoms, reduced quality of life, and greater economic burden for patients and the health care system.2,3

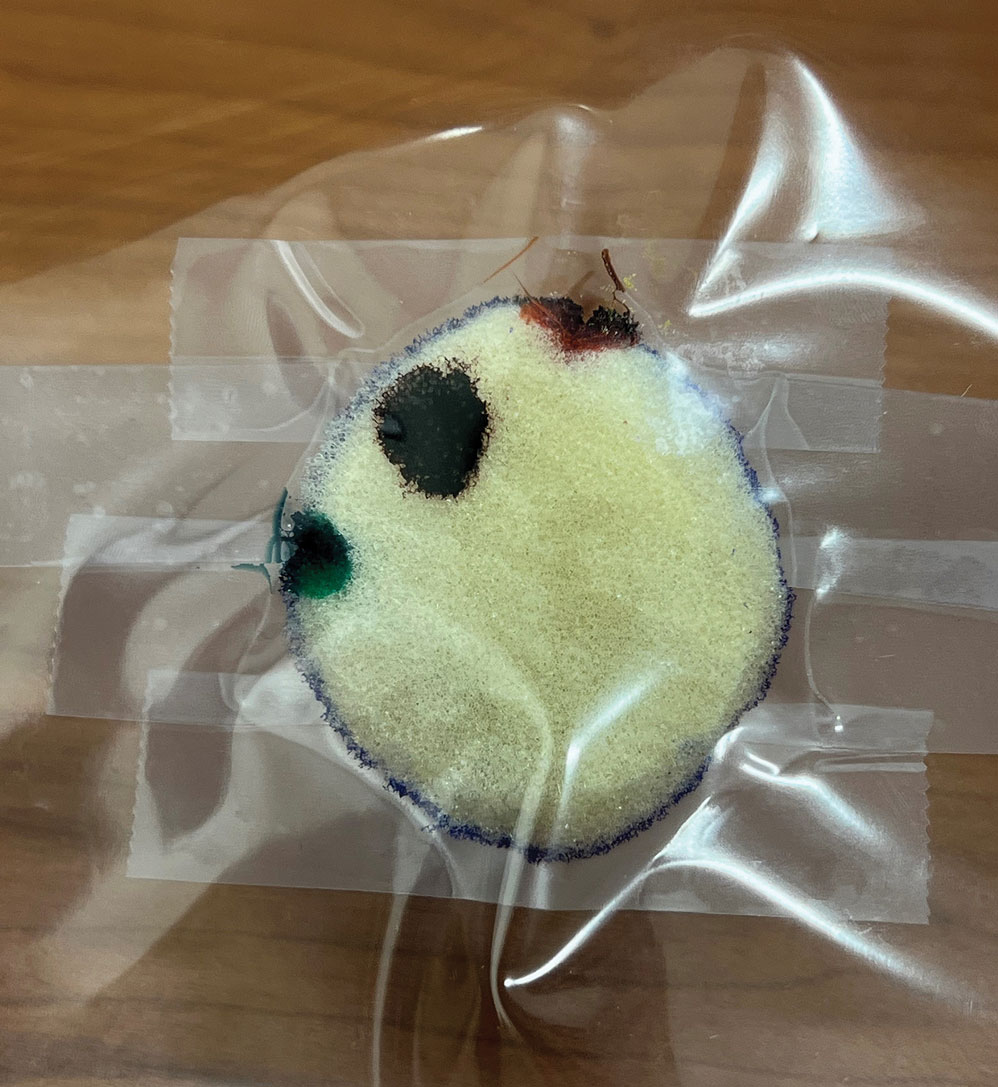

Patch testing (PT) is the only available diagnostic test for ACD, allowing for identification and subsequent avoidance of contact allergens. Patch testing involves applying allergens—typically chemicals that can be found in personal care products—onto the skin for 48 hours. Delayed readings are completed 72 to 168 hours after application. Interpretation of relevance and patient counseling, with resultant allergen avoidance, are required for a successful patient experience. Patch testing is considered safe in tested populations; rare risks associated with PT include active sensitization and anaphylaxis.4

There are many screening series available, with the number of screening allergens ranging from 35 (T.R.U.E. [Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous] test) to 90 (American Contact Dermatitis Society [ACDS] Core series). Comprehensive PT generally refers to the completion of PT for all potentially relevant and testable allergens for a given patient, which typically involves testing beyond a screening series. Currently in the United States, comprehensive PT typically includes testing for 80 to 90 allergens and any additional potentially relevant allergens based on the clinical history and patient exposures. A 2018 survey noted that, of 149 ACDS members, 82% always used a baseline screening series for PT, with 62% of these routinely testing 80 allergens and 18% routinely testing 70 allergens.5 Additionally, nearly 70% always or sometimes tested with supplemental or additional series. In other words, advanced patch testers were routinely testing 70 to 80 allergens in their screening series, and most were testing additional allergens to ensure the best care for their patients.

To account for emerging allergens, accommodate changes in allergen test concentrations recommended by ACDS and the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), and address the need for comprehensive PT for most patients, recommended screening series are regularly updated by patch test societies and expert panels such as the ACDS and the NACDG. When the ACDS Core series6 was introduced in 2013, it consisted of 80 recommended allergens.7 The panel was updated in 20178 and again in 2020,6 most recently with 90 allergens. The NACDG has collected patch test data since at least 19929 and revisits their recommended screening series on a 2-year cycle, evaluating test concentrations and adding and removing allergens based on allergen trends, allergen performance, patient need, and emergence of new allergens; the current NACDG series consists of 80 allergens. This article illustrates the clinical and public health value of comprehensive PT and the vital role of allergen access in the comprehensive patch test process, with the ultimate goal of optimizing care for patients with ACD.

Value of Comprehensive Patch Testing for ACD

Early PT represents the most cost-effective approach to the diagnosis and management of ACD. Lack of access to PT can lead to delayed diagnosis, resulting in continued exposure to the offending allergen, disease chronicity, and ultimately worse quality-of-life scores compared with patients who are diagnosed early.10 Earlier diagnosis also can minimize costs by avoiding unnecessary treatments. Without access to comprehensive PT, patients could potentially be erroneously diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and subsequently treated with expensive biologic therapies (eg, dupilumab, which costs approximately $4000 per dose or $104,000 per year11), when allergen avoidance would have been curative with minimal cost. The continued value of comprehensive PT, especially in the era of the atopic dermatitis therapeutic revolution, cannot be more strongly emphasized.

Among 140 patients with ACD, 87% found PT useful, 91% were able to avoid allergens, and 57% noted improvement or resolution of their dermatitis after avoidance of identified allergens.12 A multicenter prospective observational study demonstrated that PT improved dermatology-specific quality of life and reduced resources used for patients with ACD compared to non–patch tested individuals.13 Another study found that patients with ACD who underwent PT and were confirmed as having relevant positive contact allergens showed improvement in both perceived eczema severity and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores just 2 months after testing.14 This effect is attributed to the identification and subsequent avoidance of clinically relevant contact allergens. In a study of 519 patients with dermatitis, Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved significantly after PT regardless of whether the results were positive or negative, indicating benefits for the care and treatment of dermatitis, even in the setting of negative patch test results (P< .001).15 This could because they were still counseled on gentle skin care and management of their dermatitis at the PT visit. Improvements in disease severity also have been observed in adults and children after PT, with most patients having partial to complete clearance of their dermatitis.16,17 This is not surprising, as comprehensive PT allows clinicians to diagnose the cause of ACD by finding the exact allergen triggering the eruption and then guide patients through avoidance of these allergens to eventually clear their dermatitis.

Comprehensive Patch Testing Captures Allergen Trends

Dermatologists who perform PT in the United States currently have access to a diverse array of allergens, with more than 500 different allergens available. Access to and utilization of these allergens are essential for the comprehensive evaluation needed for our patients.

Comprehensive PT has uncovered emerging allergens such as dimethyl fumarate, the potent cause of sofa dermatitis18; isobornyl acrylate, which is found in wearable diabetic monitors19; and acetophenone azine, which can cause shin guard ACD in athletes.20 Increasing prevalence of ACD to these allergens would not have been identified without provider access to PT. Patch testing also has identified emerging allergen trends, such as the methylisothiazolinone allergy epidemic.21 All of these emerging allergens, identified through PT, have been named Contact Allergen of the Year by the ACDS due to their newfound relevance.18-20

In contrast, allergen prevalence can decrease over time, leading to removal from screening panels; examples include methyldibromo glutaronitrile, which is no longer widely present in consumer products, and thimerosal, which has frequent positive results but low relevance due to its infrequent use in personal care products. In response to comprehensive PT studies, allergen concentrations may be modified, as in the case of formaldehyde, which has notable irritant potential at higher tested concentrations but remains on the ACDS Core Allergen Series with a test concentration that optimizes the number of true positive reactions while decreasing irritant reactions.6 Likewise, nickel sulfate test concentrations were increased in the NACDG screening series due to evidence that testing at 5% identifies more nickel contact allergy than testing at 2.5% without considerably increasing irritant reactions.22

Allergen Choice and Flexibility are Key to Optimal Screening

Dermatologists who perform PT usually choose their screening series based on expert consensus and recommendations.6,23 Additional test allergens for comprehensive PT typically are chosen based on patient exposures, regional trends, and clinical expertise. This flexibility traditionally has allowed for the opportunity to identify culprit allergens that are relevant for the individual patient; for example, a hairdresser may have daily exposure to resorcinol, whereas a massage therapist may have regular exposure to essential oils. Testing only a standard screening series may miss the culprit allergen for both patients. For optimal patient outcomes, allergen choice and flexibility are key.

Currently, the 35-allergen T.R.U.E. test is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved patch test; however, multiple studies have shown that comprehensive PT, including supplemental allergens, considerably improves the diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes in ACD. A 6-year retrospective study found that using an extended screening series identified an additional 10.8% of patients (n=585) with positive tests who were negative to the T.R.U.E. test.24 Patch testing with the T.R.U.E. test alone would miss almost half of the positive reactions detected by the NACDG 80-panel screening series. Furthermore, an additional 21.1% of 3056 tested patients had at least one relevant reaction to a supplemental allergen that was not present in the NACDG screening series.23 In a retrospective study of 791 patients patch tested with the NACDG screening series and 2 supplemental series, 19.5% and 12.1% of patients, respectively, had positive reactions to supplemental allergens.25 This reinforces the importance of comprehensive PT beyond a more limited screening series. Testing more allergens identifies more causative allergens for patients.

Changes in Utilization May Affect Patient Care

Recent data have shown a shift in patch test utilization. An analysis of Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims for PT between 2010 and 2018 demonstrated that an increase in patch test utilization during this period was driven mainly by nonphysician providers and allergists.26 From 2012 to 2017, the number of patients patch tested by allergists grew by 20.3% compared to only 1.84% for dermatologists.27 Since dupilumab was approved in 2017 for the management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, claims data from 2017 to 2022 showed an exponential increase in its utilization, while patch test utilization has markedly decreased.28

Dermatologists are the predominant experts in ACD, but these concerning trends suggest decreasing utilization of PT by dermatologists, possibly due to lack of required residency training in PT, cost of patch test allergens and supplies with corresponding static reimbursement rates, staff time and training required for an excellent PT experience, comparative ease of biologic prescription vs the time-intensive process of comprehensive PT, and perceived high barrier of entry into PT. This may limit patient access to high-quality comprehensive PT and more importantly, a chance for our patients to experience resolution of their skin disease.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive PT is safe, effective, and readily available. Unfettered access to a wide range of allergens improves diagnostic accuracy and quality of life and reduces economic burden from sick leave, job loss, and treatment costs. Patch testing remains the one and only way to identify causative allergens for patients with ACD, and comprehensive PT is the most ideal approach for excellent patient care.

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Hand eczema. Lancet. 2024;404:2476-2486.

- Garg V, Brod B, Gaspari AA. Patch testing: uses, systems, risks/benefits, and its role in managing the patient with contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:580-590.

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Taylor J, Liu B, et al. Patch test practice patterns of members of the American Contact Dermatitis Society. Dermatitis. 2020;31:272-275.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series. Dermatitis. 2013;24:7-9.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2017 Update. Dermatitis. 2017;28:141-143.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo VA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard tray patch test results (1992 to 1994). Am J Contact Dermat. 1995;6:160-165.

- Kadyk DL, McCarter K, Achen F, et al. Quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1037-1048.

- Dupixent® (dupilumab): pricing and insurance. Sanofi US. Updated June 2025. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.dupixent.com/support-savings/cost-insurance

- Woo PN, Hay IC, Ormerod AD. An audit of the value of patch testing and its effect on quality of life. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:244-247.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson R. Impact of patch testing on dermatology-specific quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:215-221.

- Thomson KF, Wilkinson SM, Sommer S, et al. Eczema: quality of life by body site and the effect of patch testing. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:627-630.

- Boonchai W, Charoenpipatsin N, Winayanuwattikun W, et al. Assessment of the quality of life (QoL) of patients with dermatitis and the impact of patch testing on QoL: a study of 519 patients diagnosed with dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:182-188.

- Johnson H, Rao M, Yu J. Improved or not improved, that is the question: patch testing outcomes from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Contact Dermatitis. 2024;90:324-327.

- George SE, Yu J. Patch testing outcomes in children at the Massachusetts General Hospital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:354-356.

- McNamara D. Dimethyl fumarate named 2011 allergen of the year.Int Med News. February 3, 2011. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.mdedge.com/internalmedicine/article/20401/dermatology/dimethyl-fumarate-named-2011-allergen-year

- Nath N, Reeder M, Atwater AR. Isobornyl acrylate and diabetic devices steal the show for the 2020 American Contact Dermatitis Societyallergen of the year. Cutis. 2020;105:283-285.

- Raison-Peyron N, Sasseville D. Acetophenone azine. Dermatitis. 2021;32:5-9.

- Castanedo-Tardana MP, Zug KA. Methylisothiazolinone. Dermatitis. 2013;24:2-6.

- Svedman C, Ale I, Goh CL, et al. Patch testing with nickel sulfate 5.0% traces significantly more contact allergy than 2.5%: a prospective study within the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Dermatitis. 2022;33:417-420.

- Houle MC, DeKoven JG, Atwater AR, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2021-2022. Dermatitis. 2025;36:464-476.

- Sundquist BK, Yang B, Pasha MA. Experience in patch testing: a 6-year retrospective review from a single academic allergy practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:502-507.

- Atwater AR, Liu B, Walsh R, et al. Supplemental patch testing identifies allergens missed by standard screening series. Dermatitis. 2024;35:366-372.

- Ravishankar A, Freese RL, Parsons HM, et al. Trends in patch testing in the Medicare Part B fee-for-service population. Dermatitis. 2022;33:129-134.

- Cheraghlou S, Watsky KL, Cohen JM. Utilization, cost, and provider trends in patch testing among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States from 2012 to 2017. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1218-1226.

- Santiago Mangual KP, Rau A, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Increasing use of dupilumab and decreasing use of patch testing in medicare patients from 2017 to 2022: a claims database study. Dermatitis. 2025;36:538-540.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common skin condition affecting approximately 20% of the general population in the United States.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a unique disease in that there is an opportunity for complete cure through allergen avoidance; however, this requires proper identification of the offending allergen. When the culprit allergen is not identified or removed from the patient’s environment, chronic ACD can develop, leading to persistent inflammation and related symptoms, reduced quality of life, and greater economic burden for patients and the health care system.2,3

Patch testing (PT) is the only available diagnostic test for ACD, allowing for identification and subsequent avoidance of contact allergens. Patch testing involves applying allergens—typically chemicals that can be found in personal care products—onto the skin for 48 hours. Delayed readings are completed 72 to 168 hours after application. Interpretation of relevance and patient counseling, with resultant allergen avoidance, are required for a successful patient experience. Patch testing is considered safe in tested populations; rare risks associated with PT include active sensitization and anaphylaxis.4

There are many screening series available, with the number of screening allergens ranging from 35 (T.R.U.E. [Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous] test) to 90 (American Contact Dermatitis Society [ACDS] Core series). Comprehensive PT generally refers to the completion of PT for all potentially relevant and testable allergens for a given patient, which typically involves testing beyond a screening series. Currently in the United States, comprehensive PT typically includes testing for 80 to 90 allergens and any additional potentially relevant allergens based on the clinical history and patient exposures. A 2018 survey noted that, of 149 ACDS members, 82% always used a baseline screening series for PT, with 62% of these routinely testing 80 allergens and 18% routinely testing 70 allergens.5 Additionally, nearly 70% always or sometimes tested with supplemental or additional series. In other words, advanced patch testers were routinely testing 70 to 80 allergens in their screening series, and most were testing additional allergens to ensure the best care for their patients.

To account for emerging allergens, accommodate changes in allergen test concentrations recommended by ACDS and the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), and address the need for comprehensive PT for most patients, recommended screening series are regularly updated by patch test societies and expert panels such as the ACDS and the NACDG. When the ACDS Core series6 was introduced in 2013, it consisted of 80 recommended allergens.7 The panel was updated in 20178 and again in 2020,6 most recently with 90 allergens. The NACDG has collected patch test data since at least 19929 and revisits their recommended screening series on a 2-year cycle, evaluating test concentrations and adding and removing allergens based on allergen trends, allergen performance, patient need, and emergence of new allergens; the current NACDG series consists of 80 allergens. This article illustrates the clinical and public health value of comprehensive PT and the vital role of allergen access in the comprehensive patch test process, with the ultimate goal of optimizing care for patients with ACD.

Value of Comprehensive Patch Testing for ACD

Early PT represents the most cost-effective approach to the diagnosis and management of ACD. Lack of access to PT can lead to delayed diagnosis, resulting in continued exposure to the offending allergen, disease chronicity, and ultimately worse quality-of-life scores compared with patients who are diagnosed early.10 Earlier diagnosis also can minimize costs by avoiding unnecessary treatments. Without access to comprehensive PT, patients could potentially be erroneously diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and subsequently treated with expensive biologic therapies (eg, dupilumab, which costs approximately $4000 per dose or $104,000 per year11), when allergen avoidance would have been curative with minimal cost. The continued value of comprehensive PT, especially in the era of the atopic dermatitis therapeutic revolution, cannot be more strongly emphasized.

Among 140 patients with ACD, 87% found PT useful, 91% were able to avoid allergens, and 57% noted improvement or resolution of their dermatitis after avoidance of identified allergens.12 A multicenter prospective observational study demonstrated that PT improved dermatology-specific quality of life and reduced resources used for patients with ACD compared to non–patch tested individuals.13 Another study found that patients with ACD who underwent PT and were confirmed as having relevant positive contact allergens showed improvement in both perceived eczema severity and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores just 2 months after testing.14 This effect is attributed to the identification and subsequent avoidance of clinically relevant contact allergens. In a study of 519 patients with dermatitis, Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved significantly after PT regardless of whether the results were positive or negative, indicating benefits for the care and treatment of dermatitis, even in the setting of negative patch test results (P< .001).15 This could because they were still counseled on gentle skin care and management of their dermatitis at the PT visit. Improvements in disease severity also have been observed in adults and children after PT, with most patients having partial to complete clearance of their dermatitis.16,17 This is not surprising, as comprehensive PT allows clinicians to diagnose the cause of ACD by finding the exact allergen triggering the eruption and then guide patients through avoidance of these allergens to eventually clear their dermatitis.

Comprehensive Patch Testing Captures Allergen Trends

Dermatologists who perform PT in the United States currently have access to a diverse array of allergens, with more than 500 different allergens available. Access to and utilization of these allergens are essential for the comprehensive evaluation needed for our patients.

Comprehensive PT has uncovered emerging allergens such as dimethyl fumarate, the potent cause of sofa dermatitis18; isobornyl acrylate, which is found in wearable diabetic monitors19; and acetophenone azine, which can cause shin guard ACD in athletes.20 Increasing prevalence of ACD to these allergens would not have been identified without provider access to PT. Patch testing also has identified emerging allergen trends, such as the methylisothiazolinone allergy epidemic.21 All of these emerging allergens, identified through PT, have been named Contact Allergen of the Year by the ACDS due to their newfound relevance.18-20

In contrast, allergen prevalence can decrease over time, leading to removal from screening panels; examples include methyldibromo glutaronitrile, which is no longer widely present in consumer products, and thimerosal, which has frequent positive results but low relevance due to its infrequent use in personal care products. In response to comprehensive PT studies, allergen concentrations may be modified, as in the case of formaldehyde, which has notable irritant potential at higher tested concentrations but remains on the ACDS Core Allergen Series with a test concentration that optimizes the number of true positive reactions while decreasing irritant reactions.6 Likewise, nickel sulfate test concentrations were increased in the NACDG screening series due to evidence that testing at 5% identifies more nickel contact allergy than testing at 2.5% without considerably increasing irritant reactions.22

Allergen Choice and Flexibility are Key to Optimal Screening

Dermatologists who perform PT usually choose their screening series based on expert consensus and recommendations.6,23 Additional test allergens for comprehensive PT typically are chosen based on patient exposures, regional trends, and clinical expertise. This flexibility traditionally has allowed for the opportunity to identify culprit allergens that are relevant for the individual patient; for example, a hairdresser may have daily exposure to resorcinol, whereas a massage therapist may have regular exposure to essential oils. Testing only a standard screening series may miss the culprit allergen for both patients. For optimal patient outcomes, allergen choice and flexibility are key.

Currently, the 35-allergen T.R.U.E. test is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved patch test; however, multiple studies have shown that comprehensive PT, including supplemental allergens, considerably improves the diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes in ACD. A 6-year retrospective study found that using an extended screening series identified an additional 10.8% of patients (n=585) with positive tests who were negative to the T.R.U.E. test.24 Patch testing with the T.R.U.E. test alone would miss almost half of the positive reactions detected by the NACDG 80-panel screening series. Furthermore, an additional 21.1% of 3056 tested patients had at least one relevant reaction to a supplemental allergen that was not present in the NACDG screening series.23 In a retrospective study of 791 patients patch tested with the NACDG screening series and 2 supplemental series, 19.5% and 12.1% of patients, respectively, had positive reactions to supplemental allergens.25 This reinforces the importance of comprehensive PT beyond a more limited screening series. Testing more allergens identifies more causative allergens for patients.

Changes in Utilization May Affect Patient Care

Recent data have shown a shift in patch test utilization. An analysis of Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims for PT between 2010 and 2018 demonstrated that an increase in patch test utilization during this period was driven mainly by nonphysician providers and allergists.26 From 2012 to 2017, the number of patients patch tested by allergists grew by 20.3% compared to only 1.84% for dermatologists.27 Since dupilumab was approved in 2017 for the management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, claims data from 2017 to 2022 showed an exponential increase in its utilization, while patch test utilization has markedly decreased.28

Dermatologists are the predominant experts in ACD, but these concerning trends suggest decreasing utilization of PT by dermatologists, possibly due to lack of required residency training in PT, cost of patch test allergens and supplies with corresponding static reimbursement rates, staff time and training required for an excellent PT experience, comparative ease of biologic prescription vs the time-intensive process of comprehensive PT, and perceived high barrier of entry into PT. This may limit patient access to high-quality comprehensive PT and more importantly, a chance for our patients to experience resolution of their skin disease.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive PT is safe, effective, and readily available. Unfettered access to a wide range of allergens improves diagnostic accuracy and quality of life and reduces economic burden from sick leave, job loss, and treatment costs. Patch testing remains the one and only way to identify causative allergens for patients with ACD, and comprehensive PT is the most ideal approach for excellent patient care.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common skin condition affecting approximately 20% of the general population in the United States.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a unique disease in that there is an opportunity for complete cure through allergen avoidance; however, this requires proper identification of the offending allergen. When the culprit allergen is not identified or removed from the patient’s environment, chronic ACD can develop, leading to persistent inflammation and related symptoms, reduced quality of life, and greater economic burden for patients and the health care system.2,3

Patch testing (PT) is the only available diagnostic test for ACD, allowing for identification and subsequent avoidance of contact allergens. Patch testing involves applying allergens—typically chemicals that can be found in personal care products—onto the skin for 48 hours. Delayed readings are completed 72 to 168 hours after application. Interpretation of relevance and patient counseling, with resultant allergen avoidance, are required for a successful patient experience. Patch testing is considered safe in tested populations; rare risks associated with PT include active sensitization and anaphylaxis.4

There are many screening series available, with the number of screening allergens ranging from 35 (T.R.U.E. [Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous] test) to 90 (American Contact Dermatitis Society [ACDS] Core series). Comprehensive PT generally refers to the completion of PT for all potentially relevant and testable allergens for a given patient, which typically involves testing beyond a screening series. Currently in the United States, comprehensive PT typically includes testing for 80 to 90 allergens and any additional potentially relevant allergens based on the clinical history and patient exposures. A 2018 survey noted that, of 149 ACDS members, 82% always used a baseline screening series for PT, with 62% of these routinely testing 80 allergens and 18% routinely testing 70 allergens.5 Additionally, nearly 70% always or sometimes tested with supplemental or additional series. In other words, advanced patch testers were routinely testing 70 to 80 allergens in their screening series, and most were testing additional allergens to ensure the best care for their patients.

To account for emerging allergens, accommodate changes in allergen test concentrations recommended by ACDS and the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), and address the need for comprehensive PT for most patients, recommended screening series are regularly updated by patch test societies and expert panels such as the ACDS and the NACDG. When the ACDS Core series6 was introduced in 2013, it consisted of 80 recommended allergens.7 The panel was updated in 20178 and again in 2020,6 most recently with 90 allergens. The NACDG has collected patch test data since at least 19929 and revisits their recommended screening series on a 2-year cycle, evaluating test concentrations and adding and removing allergens based on allergen trends, allergen performance, patient need, and emergence of new allergens; the current NACDG series consists of 80 allergens. This article illustrates the clinical and public health value of comprehensive PT and the vital role of allergen access in the comprehensive patch test process, with the ultimate goal of optimizing care for patients with ACD.

Value of Comprehensive Patch Testing for ACD

Early PT represents the most cost-effective approach to the diagnosis and management of ACD. Lack of access to PT can lead to delayed diagnosis, resulting in continued exposure to the offending allergen, disease chronicity, and ultimately worse quality-of-life scores compared with patients who are diagnosed early.10 Earlier diagnosis also can minimize costs by avoiding unnecessary treatments. Without access to comprehensive PT, patients could potentially be erroneously diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and subsequently treated with expensive biologic therapies (eg, dupilumab, which costs approximately $4000 per dose or $104,000 per year11), when allergen avoidance would have been curative with minimal cost. The continued value of comprehensive PT, especially in the era of the atopic dermatitis therapeutic revolution, cannot be more strongly emphasized.

Among 140 patients with ACD, 87% found PT useful, 91% were able to avoid allergens, and 57% noted improvement or resolution of their dermatitis after avoidance of identified allergens.12 A multicenter prospective observational study demonstrated that PT improved dermatology-specific quality of life and reduced resources used for patients with ACD compared to non–patch tested individuals.13 Another study found that patients with ACD who underwent PT and were confirmed as having relevant positive contact allergens showed improvement in both perceived eczema severity and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores just 2 months after testing.14 This effect is attributed to the identification and subsequent avoidance of clinically relevant contact allergens. In a study of 519 patients with dermatitis, Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved significantly after PT regardless of whether the results were positive or negative, indicating benefits for the care and treatment of dermatitis, even in the setting of negative patch test results (P< .001).15 This could because they were still counseled on gentle skin care and management of their dermatitis at the PT visit. Improvements in disease severity also have been observed in adults and children after PT, with most patients having partial to complete clearance of their dermatitis.16,17 This is not surprising, as comprehensive PT allows clinicians to diagnose the cause of ACD by finding the exact allergen triggering the eruption and then guide patients through avoidance of these allergens to eventually clear their dermatitis.

Comprehensive Patch Testing Captures Allergen Trends

Dermatologists who perform PT in the United States currently have access to a diverse array of allergens, with more than 500 different allergens available. Access to and utilization of these allergens are essential for the comprehensive evaluation needed for our patients.

Comprehensive PT has uncovered emerging allergens such as dimethyl fumarate, the potent cause of sofa dermatitis18; isobornyl acrylate, which is found in wearable diabetic monitors19; and acetophenone azine, which can cause shin guard ACD in athletes.20 Increasing prevalence of ACD to these allergens would not have been identified without provider access to PT. Patch testing also has identified emerging allergen trends, such as the methylisothiazolinone allergy epidemic.21 All of these emerging allergens, identified through PT, have been named Contact Allergen of the Year by the ACDS due to their newfound relevance.18-20

In contrast, allergen prevalence can decrease over time, leading to removal from screening panels; examples include methyldibromo glutaronitrile, which is no longer widely present in consumer products, and thimerosal, which has frequent positive results but low relevance due to its infrequent use in personal care products. In response to comprehensive PT studies, allergen concentrations may be modified, as in the case of formaldehyde, which has notable irritant potential at higher tested concentrations but remains on the ACDS Core Allergen Series with a test concentration that optimizes the number of true positive reactions while decreasing irritant reactions.6 Likewise, nickel sulfate test concentrations were increased in the NACDG screening series due to evidence that testing at 5% identifies more nickel contact allergy than testing at 2.5% without considerably increasing irritant reactions.22

Allergen Choice and Flexibility are Key to Optimal Screening

Dermatologists who perform PT usually choose their screening series based on expert consensus and recommendations.6,23 Additional test allergens for comprehensive PT typically are chosen based on patient exposures, regional trends, and clinical expertise. This flexibility traditionally has allowed for the opportunity to identify culprit allergens that are relevant for the individual patient; for example, a hairdresser may have daily exposure to resorcinol, whereas a massage therapist may have regular exposure to essential oils. Testing only a standard screening series may miss the culprit allergen for both patients. For optimal patient outcomes, allergen choice and flexibility are key.

Currently, the 35-allergen T.R.U.E. test is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved patch test; however, multiple studies have shown that comprehensive PT, including supplemental allergens, considerably improves the diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes in ACD. A 6-year retrospective study found that using an extended screening series identified an additional 10.8% of patients (n=585) with positive tests who were negative to the T.R.U.E. test.24 Patch testing with the T.R.U.E. test alone would miss almost half of the positive reactions detected by the NACDG 80-panel screening series. Furthermore, an additional 21.1% of 3056 tested patients had at least one relevant reaction to a supplemental allergen that was not present in the NACDG screening series.23 In a retrospective study of 791 patients patch tested with the NACDG screening series and 2 supplemental series, 19.5% and 12.1% of patients, respectively, had positive reactions to supplemental allergens.25 This reinforces the importance of comprehensive PT beyond a more limited screening series. Testing more allergens identifies more causative allergens for patients.

Changes in Utilization May Affect Patient Care

Recent data have shown a shift in patch test utilization. An analysis of Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims for PT between 2010 and 2018 demonstrated that an increase in patch test utilization during this period was driven mainly by nonphysician providers and allergists.26 From 2012 to 2017, the number of patients patch tested by allergists grew by 20.3% compared to only 1.84% for dermatologists.27 Since dupilumab was approved in 2017 for the management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, claims data from 2017 to 2022 showed an exponential increase in its utilization, while patch test utilization has markedly decreased.28

Dermatologists are the predominant experts in ACD, but these concerning trends suggest decreasing utilization of PT by dermatologists, possibly due to lack of required residency training in PT, cost of patch test allergens and supplies with corresponding static reimbursement rates, staff time and training required for an excellent PT experience, comparative ease of biologic prescription vs the time-intensive process of comprehensive PT, and perceived high barrier of entry into PT. This may limit patient access to high-quality comprehensive PT and more importantly, a chance for our patients to experience resolution of their skin disease.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive PT is safe, effective, and readily available. Unfettered access to a wide range of allergens improves diagnostic accuracy and quality of life and reduces economic burden from sick leave, job loss, and treatment costs. Patch testing remains the one and only way to identify causative allergens for patients with ACD, and comprehensive PT is the most ideal approach for excellent patient care.

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Hand eczema. Lancet. 2024;404:2476-2486.

- Garg V, Brod B, Gaspari AA. Patch testing: uses, systems, risks/benefits, and its role in managing the patient with contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:580-590.

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Taylor J, Liu B, et al. Patch test practice patterns of members of the American Contact Dermatitis Society. Dermatitis. 2020;31:272-275.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series. Dermatitis. 2013;24:7-9.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2017 Update. Dermatitis. 2017;28:141-143.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo VA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard tray patch test results (1992 to 1994). Am J Contact Dermat. 1995;6:160-165.

- Kadyk DL, McCarter K, Achen F, et al. Quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1037-1048.