User login

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

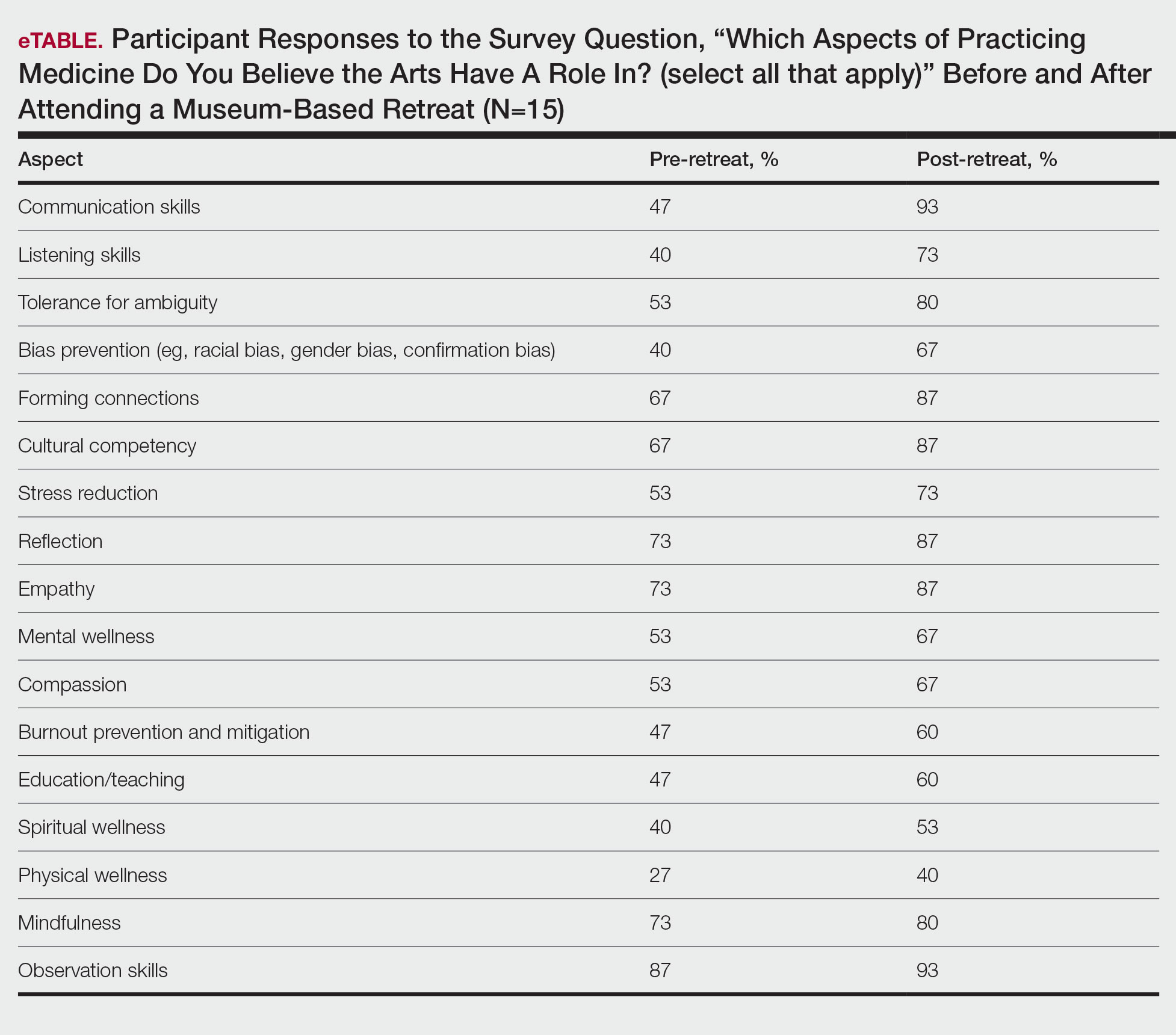

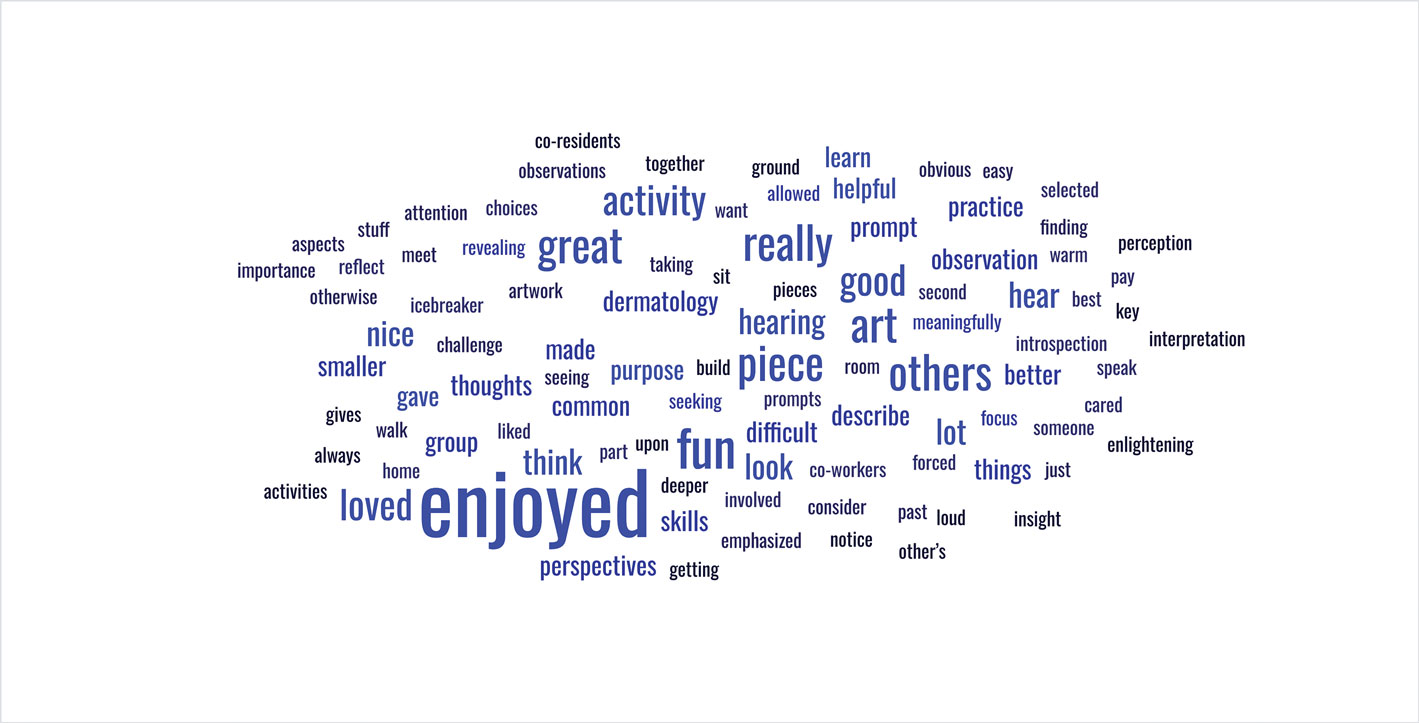

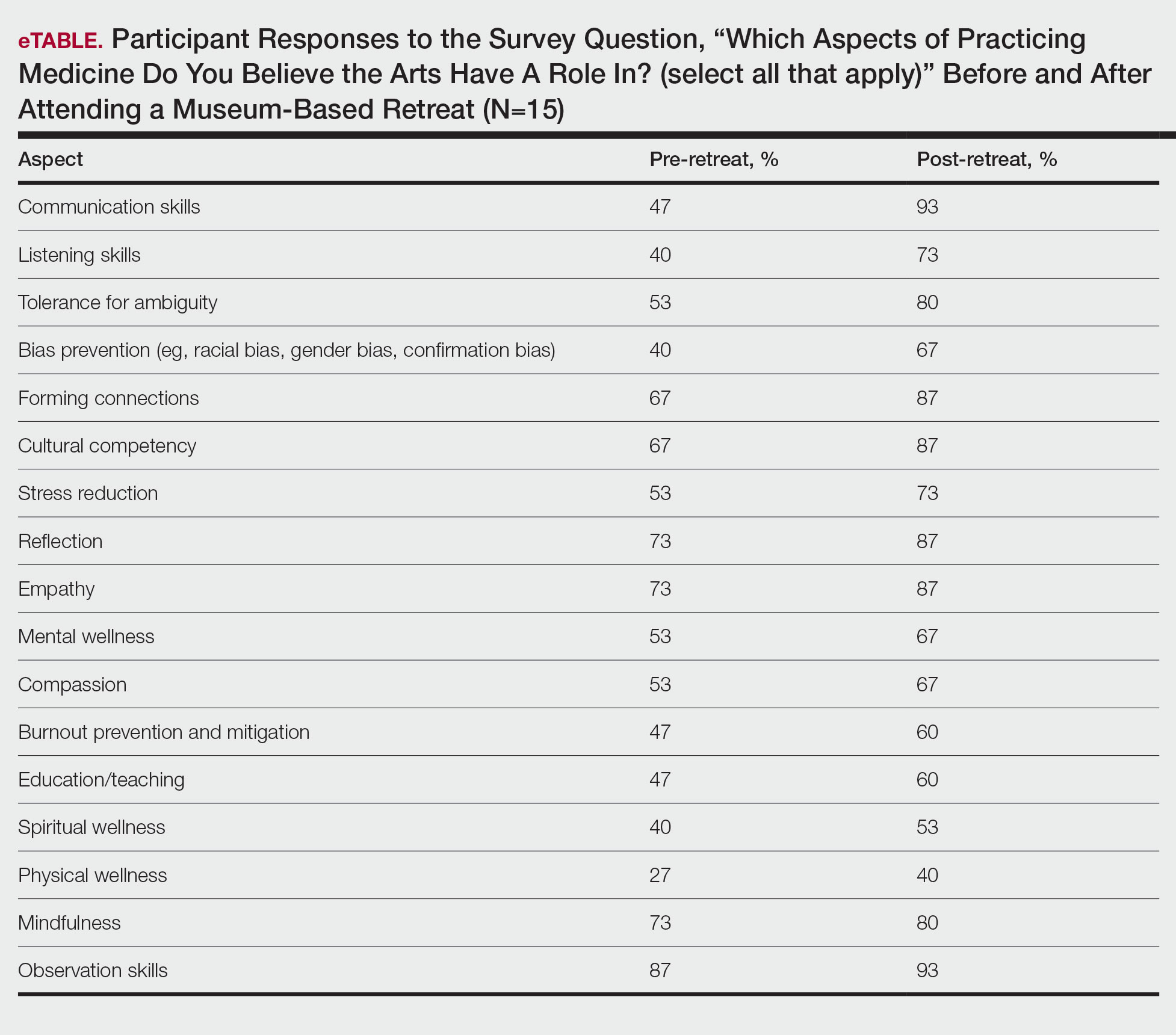

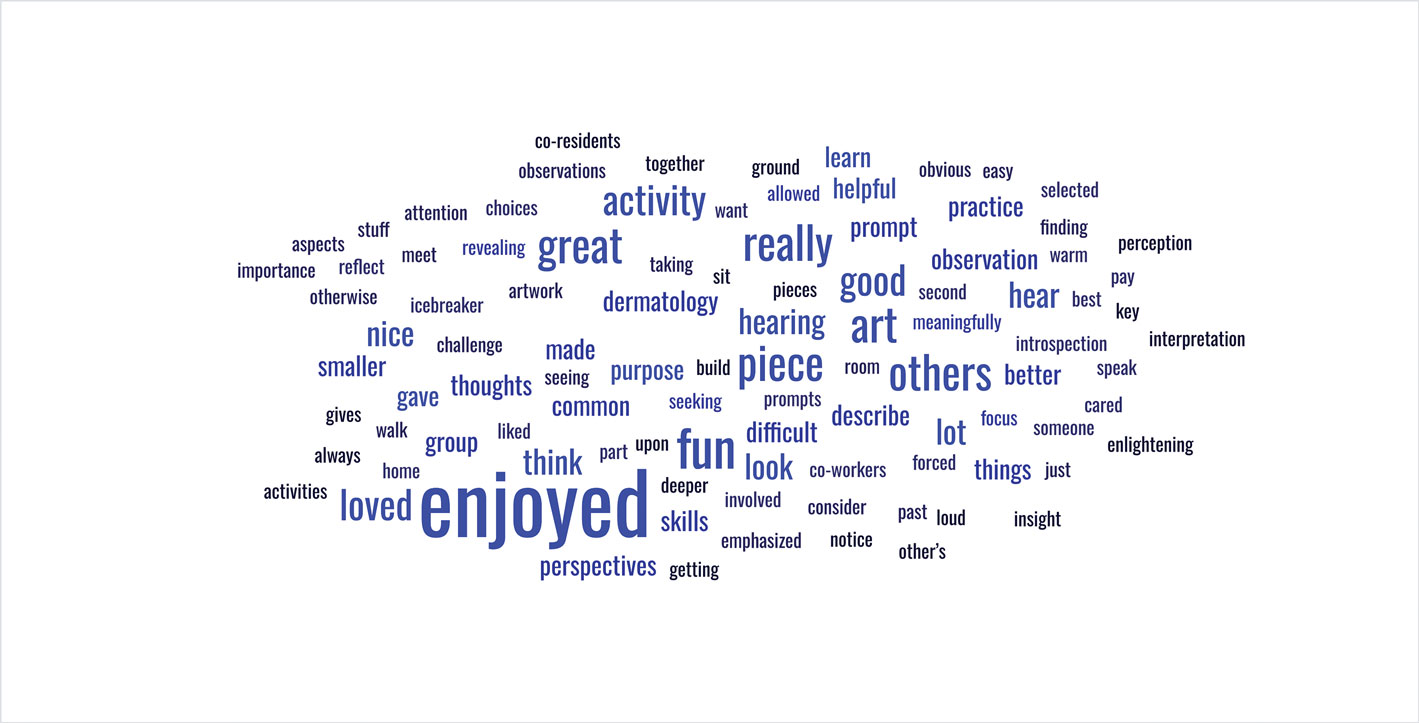

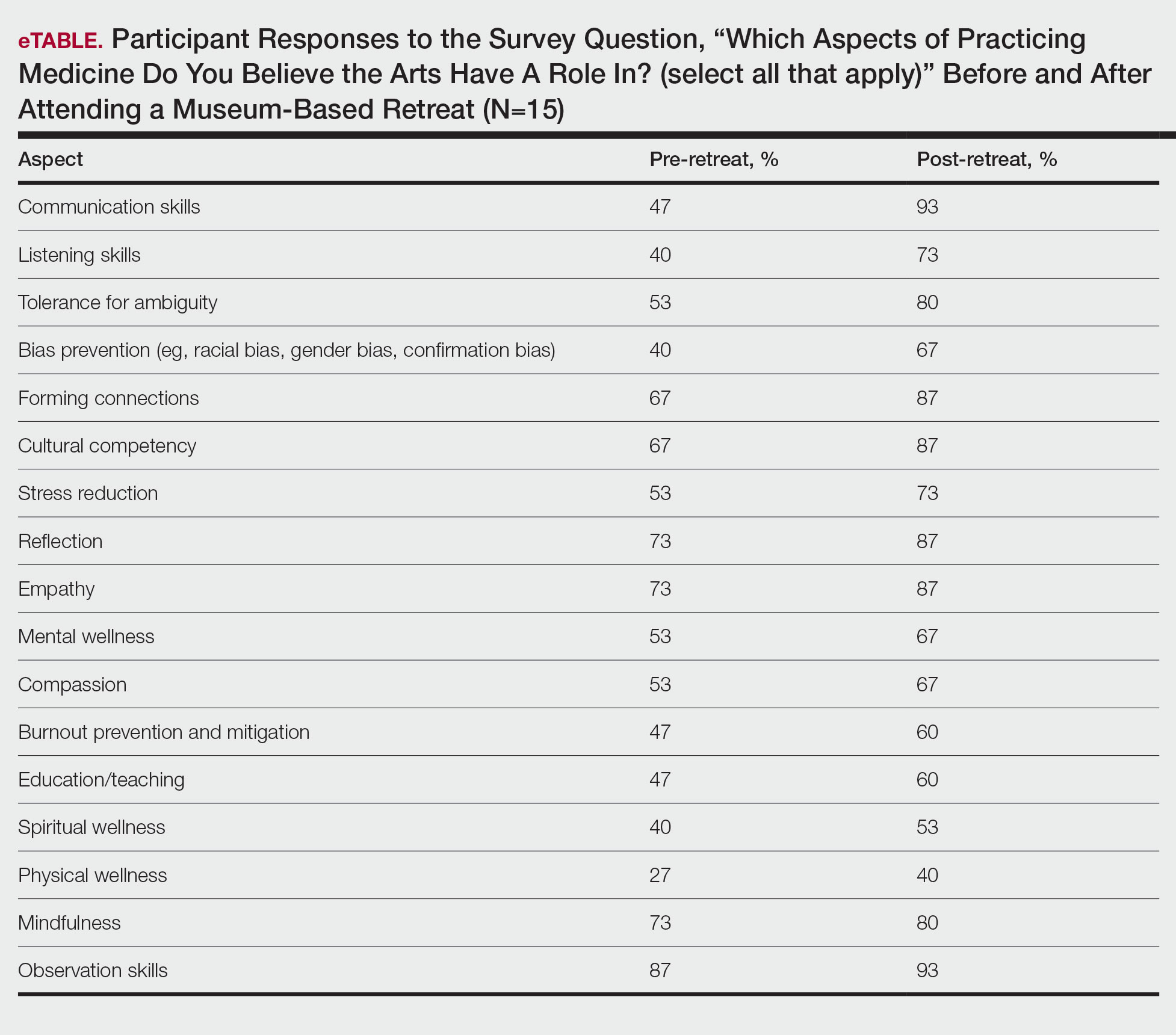

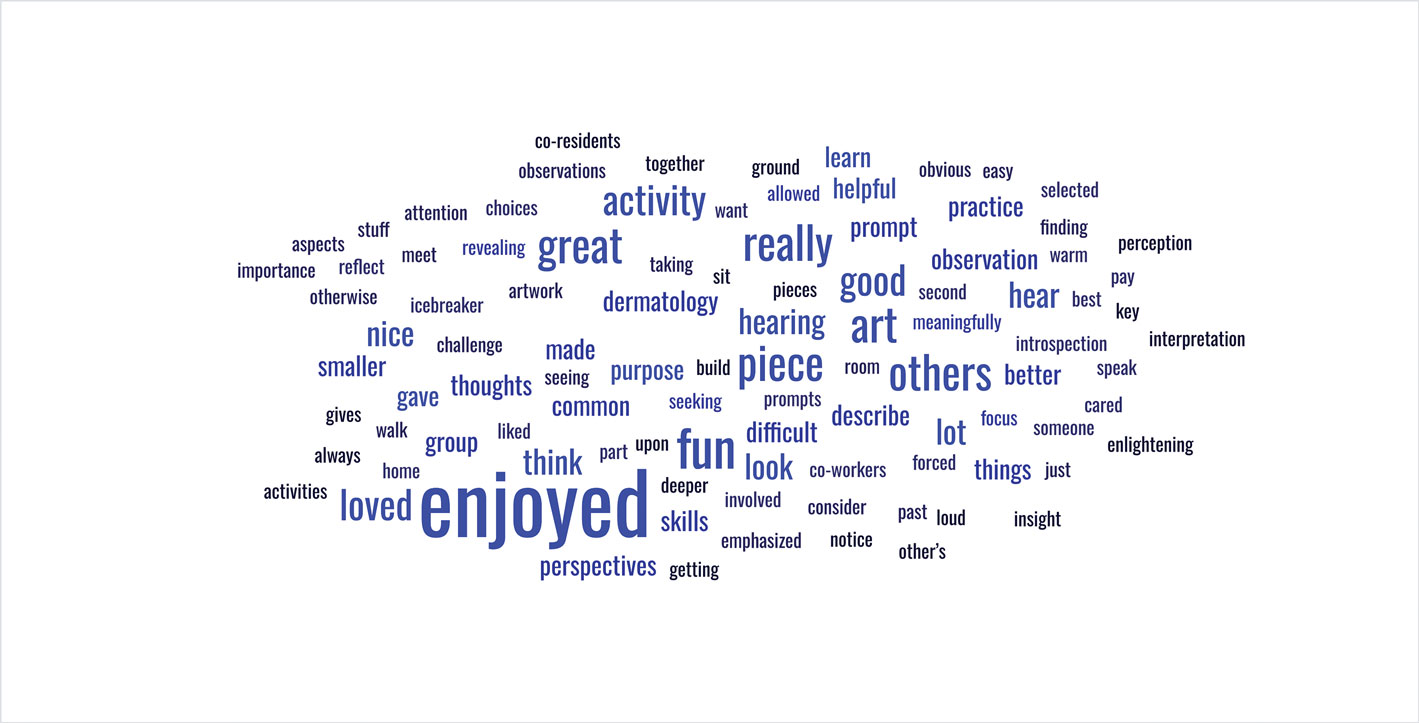

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Prior research has demonstrated that museum-based programming decreases resident burnout and depersonalization.1 A partnership between the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program was well received by residents and resulted in improvement of their observational skills.2 The impact of museum-based programming on the clinical practice skills and well-being of Duke dermatology residents and faculty has not been previously assessed.

In this study, our objective was to evaluate the impact of a 3-part museum-based arts retreat on arts appreciation, clinical practice skills, and well-being among dermatology resident and faculty participants. Surveys administered before and after the retreat were used to assess the value that participants attributed to the arts in various areas of clinical practice.

Methods

A 3-part museum-based retreat held on February 7, 2024, was developed with a Nasher Museum of Art (Durham, North Carolina) curator (E.R.). Part 1 was a personal response tour in which 15 residents and 3 faculty members were given individualized prompts and asked to identify an art piece in the museum that encapsulated their response; they then were asked to explain to the group why they chose that particular piece. Participants were given 10 minutes to explore the museum galleries to choose their piece, followed by 15 minutes to share their selected work in groups of 3 to 4.

Part 2 encompassed visual-thinking strategies, a research-based method that uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills.2 Using this method, facilitators follow a specific protocol to guide participants in the exploration of an art piece through sharing observations and interpretations.4 Participants were divided into 2 groups led by trained museum educators (including E.R.) to analyze and ascribe meaning to a chosen art piece. Three questions were asked: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What else can we find?

Part 3 involved back-to-back drawing, in which participants were paired up and tasked with recreating an art piece in the museum based solely on their partner’s verbal description. In each pair, both participants took turns as the describer and the drawer.

After each part of the retreat, 5 to 10 minutes were dedicated to debriefing in small groups about how each activity may connect to the role of a clinician. A total of 15 participants completed pre- and post-retreat surveys to assess the value they attributed to the arts and identify in which aspects of clinical practice they believe the arts play a role.

Results

Seventy-three percent of participants (11/15) found the museum-based retreat “extremely useful” or “very useful.” There was a 20% increase in those who attributed at least moderate value to the arts as a clinician after compared to before the retreat (13/15 [87%] vs 8/15 [53%]), and 100% of the participants desired to participate in future arts-based programming. Following the retreat, a greater percentage of participants believed the arts have a role in the following aspects of clinical practice: education, observation, listening, communication, empathy, compassion, forming connections, cultural sensitivity, tolerance for ambiguity, reflection, mindfulness, stress reduction, preventing burnout, bias prevention, mental wellness, spiritual wellness, and physical wellness (eTable). Qualitative feedback compiled from the participants’ responses to survey questions following the retreat about their thoughts on each activity and overall feedback was used to create a word cloud (eFigure).

Comment

The importance of arts and humanities integration into medical education previously has been described.5 Our survey results suggest that museum-based programming increases dermatology resident and faculty appreciation for the arts and encourages participation in future arts-based programming. Our results also demonstrate that arts-based programming positively impacts important resident competencies in the practice of medicine including tolerance for ambiguity, bias prevention, and cultural competency, and that the incorporation of arts-based programming can enhance residents’ well-being (physical, mental, and spiritual) as well as their ability to be better clinicians by addressing skills in communication, listening, and observation. The structure of our 3-part museum-based retreat offers practical implementation strategies for integrating the humanities into dermatology residency curricula and easily can be modified to meet the needs of different dermatology residency programs.

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Orr AR, Moghbeli N, Swain A, et al. The Fostering Resilience through Art in Medical Education (FRAME) workshop: a partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:361-369. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S194575

Zimmermann C, Huang JT, Buzney EA. Refining the eye: dermatology and visual literacy. J Museum Ed. 2016;41:116-122.

Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Harvard Education Press; 2013.

Hailey D, Miller A, Yenawine P. Understanding visual literacy: the visual thinking strategies approach. In: Baylen DM, D’Alba A. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy: Visualizing Learning. Springer Cham; 2015:49-73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05837-5

Howley L, Gaufberg E, King BE. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://store.aamc.org/the-fundamental-role-of-the-arts-and-humanities-in-medical-education.html

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Impact of a Museum-Based Retreat on the Clinical Skills and Well-Being of Dermatology Residents and Faculty

Practice Points

- Arts-based programming positively impacts resident competencies that are important to the practice of medicine.

- Incorporating arts-based programming in the dermatology residency curriculum can enhance resident well-being and the ability to be better clinicians.

A Comparison of Knowledge Acquisition and Perceived Efficacy of a Traditional vs Flipped Classroom–Based Dermatology Residency Curriculum

The ideal method of resident education is a subject of great interest within the medical community, and many dermatology residency programs utilize a traditional classroom model for didactic training consisting of required textbook reading completed at home and classroom lectures that often include presentations featuring text, dermatology images, and questions throughout the lecture. A second teaching model is known as the flipped, or inverted, classroom. This model moves the didactic material that typically is covered in the classroom into the realm of home study or homework and focuses on application and clarification of the new material in the classroom. 1 There is an emphasis on completing and understanding course material prior to the classroom session. Students are expected to be prepared for the lesson, and the classroom session can include question review and deeper exploration of the topic with a focus on subject mastery. 2

In recent years, the flipped classroom model has been used in elementary education, due in part to the influence of teachers Bergmann and Sams,3 as described in their book Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. More recently, Prober and Khan4 argued for its use in medical education, and this model has been utilized in medical school curricula to teach specialty subjects, including medical dermatology.5

Given the increasing popularity and use of the flipped classroom, the primary objective of this study was to determine if a difference in knowledge acquisition and resident perception exists between the traditional and flipped classrooms. If differences do exist, the secondary aim was to quantify them. We hypothesized that the flipped classroom actively engages residents and would improve both knowledge acquisition and resident sentiment toward the residency program curriculum compared to the traditional model.

Methods

The Duke Health (Durham, North Carolina) institutional review board granted approval for this study. All of the dermatology residents from Duke University Medical Center for the 2014-2015 academic year participated in this study. Twelve individual lectures chosen by the dermatology residency program director were included: 6 traditional lectures and 6 flipped lectures. The lectures were paired for similar content.

Survey Administration

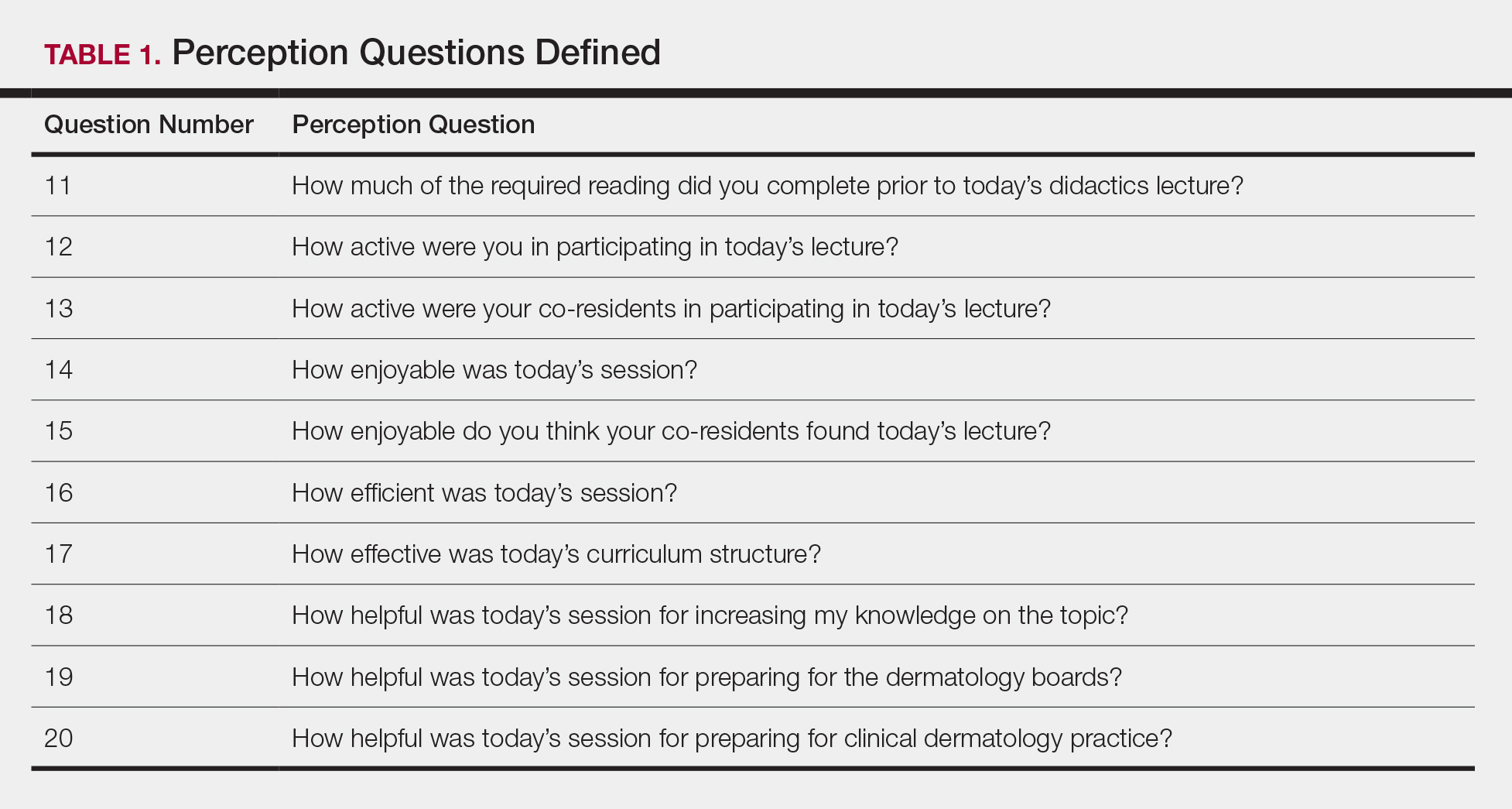

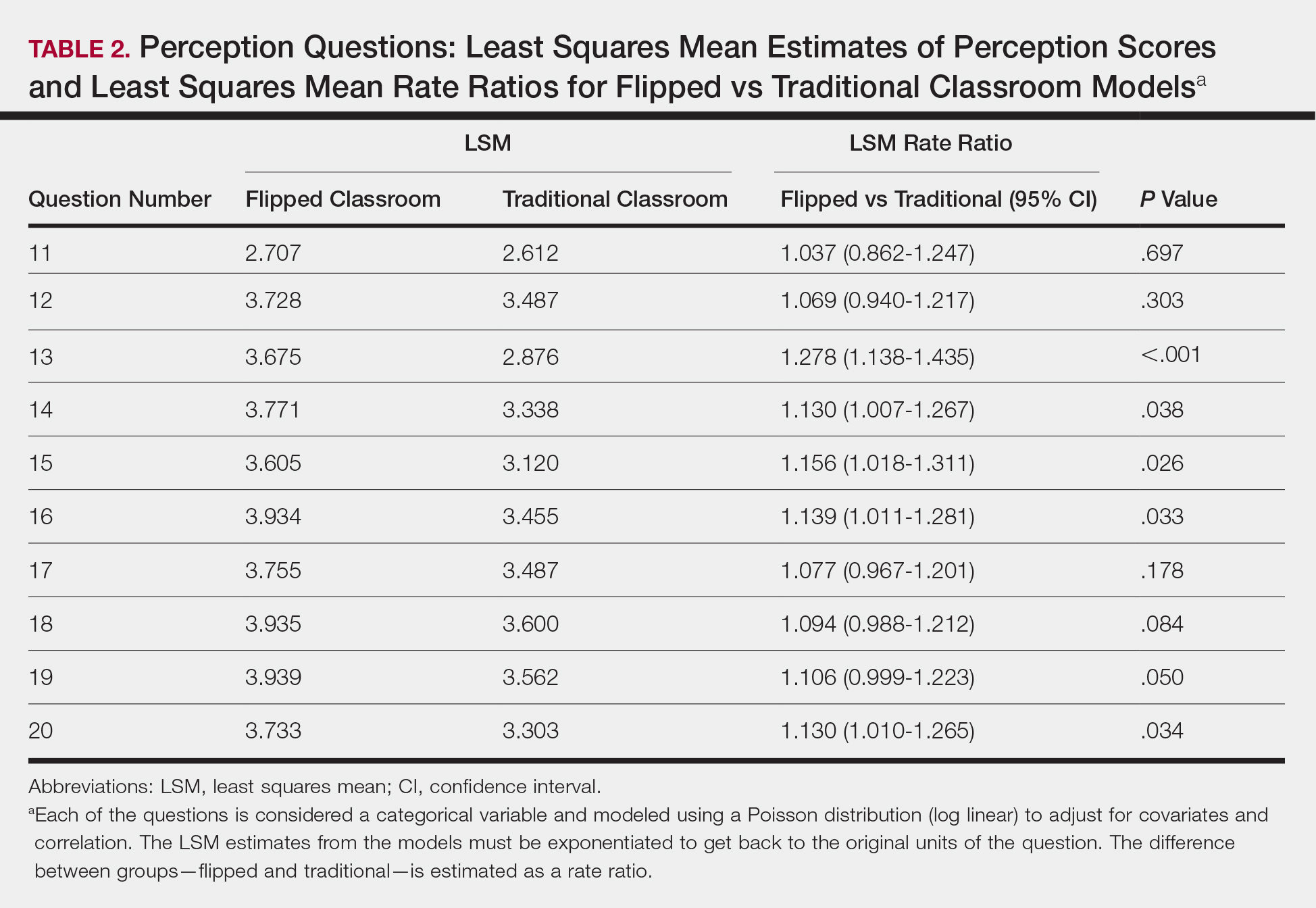

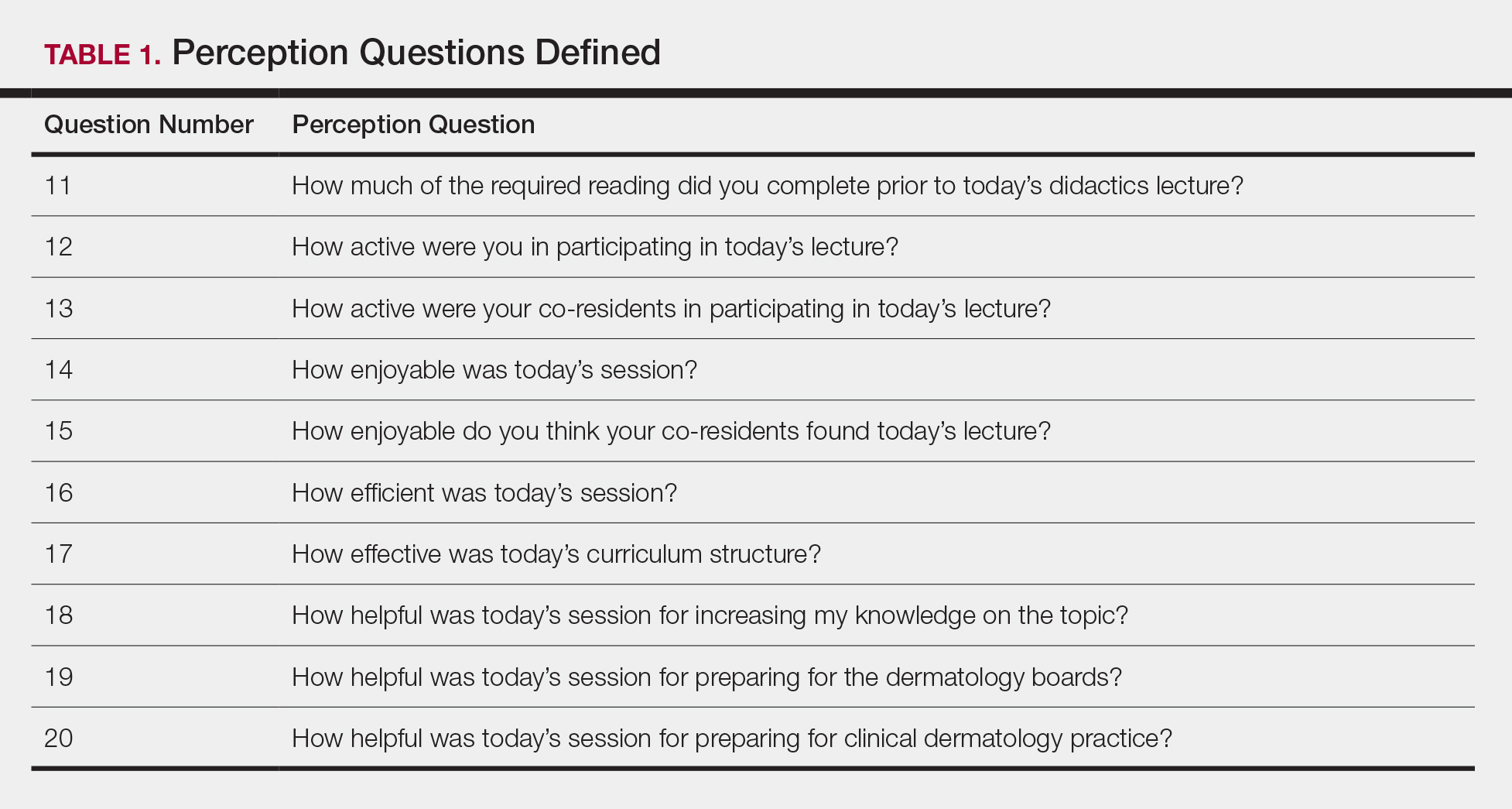

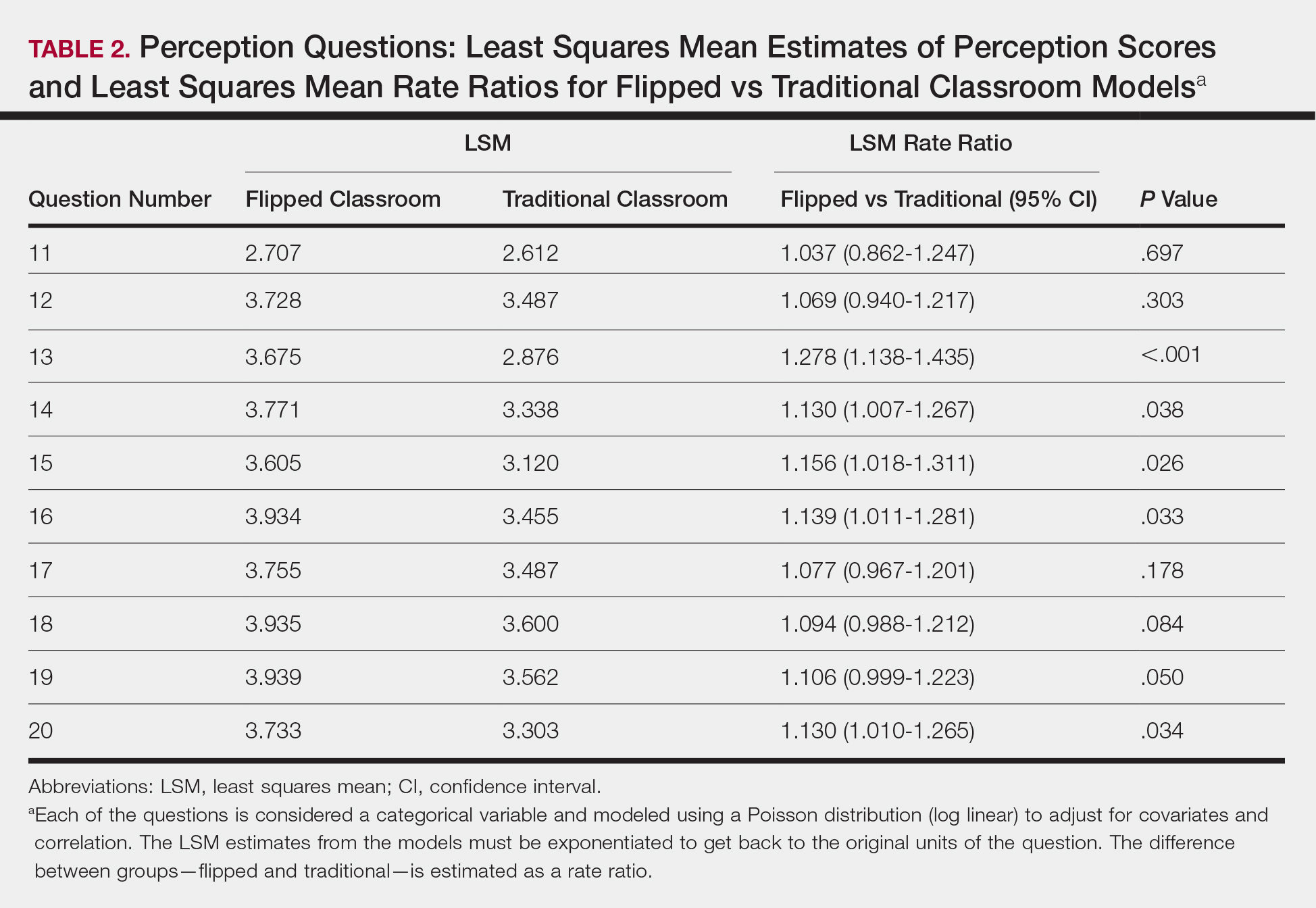

Each resident was assigned a unique 4-digit numeric code that was unknown to the investigators and recorded at the beginning of each survey. The residents expected flipped lectures for each session and were blinded as to when a traditional lecture and quiz would occur, with the exception of the resident providing the lecture. Classroom presentations were immediately followed by a voluntary survey administered through Qualtrics.6 Consent was given at the beginning of each survey, followed by 10 factual questions and 10 perception questions. The factual questions varied based on the lecture topic and were multiple-choice questions written by the program director, associate program director, and faculty. Each factual question was worth 10 points, and the scaled score for each quiz had a maximum value of 100. The perception questions were developed by the authors (J.H. and A.R.A.) in consultation with a survey methodology expert at the Duke Social Science Research Institute. These questions remained constant across each survey and were descriptive based on standard response scales. The data were extracted from Qualtrics for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The mean score with the standard deviation for each factual question quiz was calculated and plotted. A generalized linear mixed model was created to study the difference in quiz scores between the 2 classroom models after adjusting for other covariates, including resident, the interaction between resident and class type, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was specified as a random variable, and a variance components covariance structure was used. For the perception questions, the frequency and percentage of each answer for a question was counted. Generalized linear mixed models with a Poisson distribution were created to study the difference in answers for each survey question between the 2 curriculum types after adjusting for other covariates, including scores for factual questions, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was again specified as a random variable, and a diagonal covariance structure was used. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute) by the Duke University Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All 9 of the department’s residents were included and participated in this study. Mean score with standard deviation for each factual quiz is plotted in the Figure. Across all residents, the mean factual quiz score was slightly higher but not statistically significant in the flipped vs traditional classrooms (67.5% vs 65.4%; P=.448)(data not shown). When comparing traditional and flipped factual quiz scores by individual resident, there was not a significant difference in quiz performance (P=.166)(data not shown). However, there was a significant difference in the factual quiz scores among residents for all quizzes (P=.005) as well as a significant difference in performance between each individual quiz over time (P<.001)(data not shown). In the traditional classroom, residents demonstrated a trend in variable performance with each factual quiz. In the flipped classroom, residents also had variable performance, with wide-ranging scores (P=.008)(data not shown).

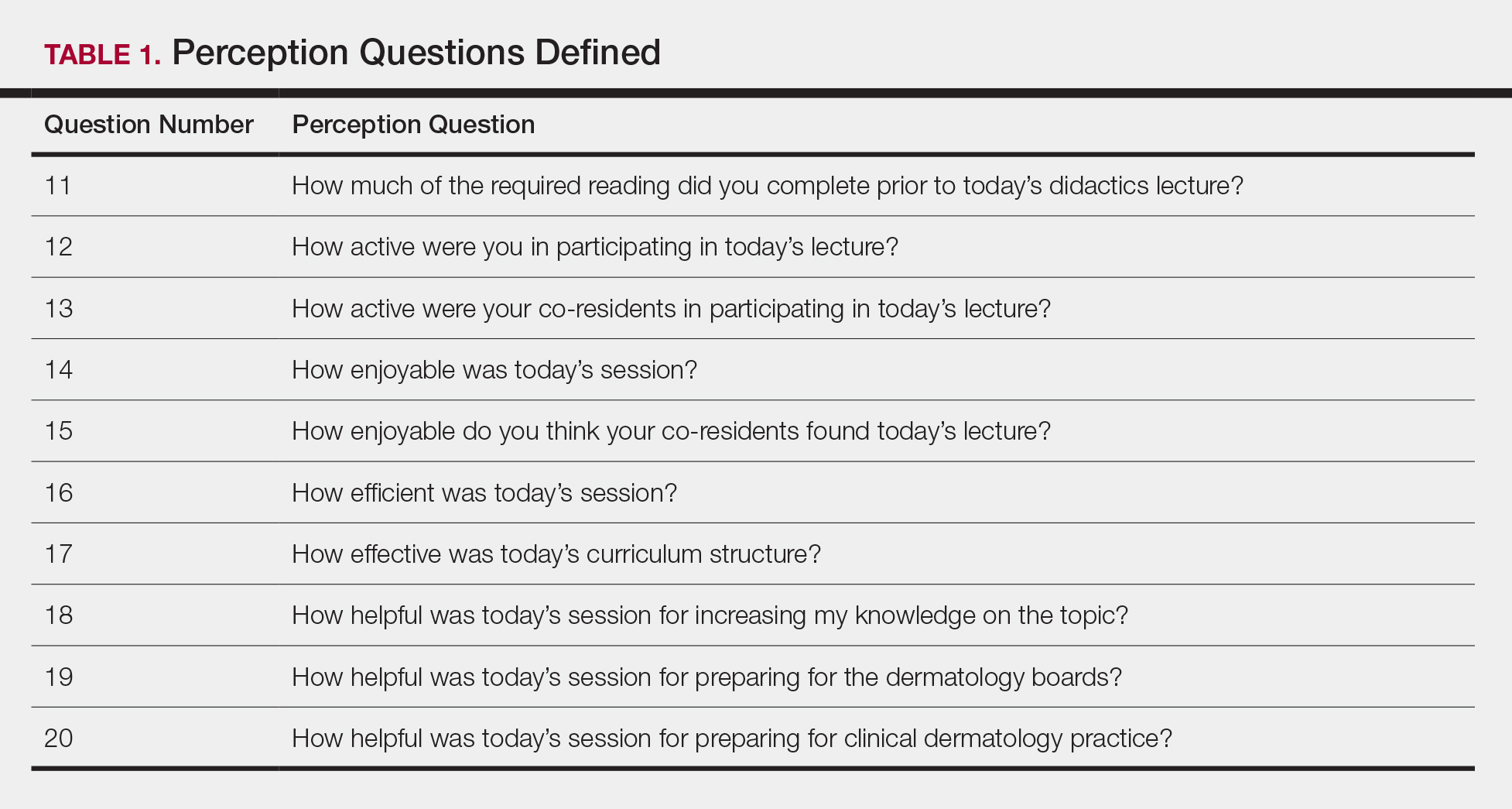

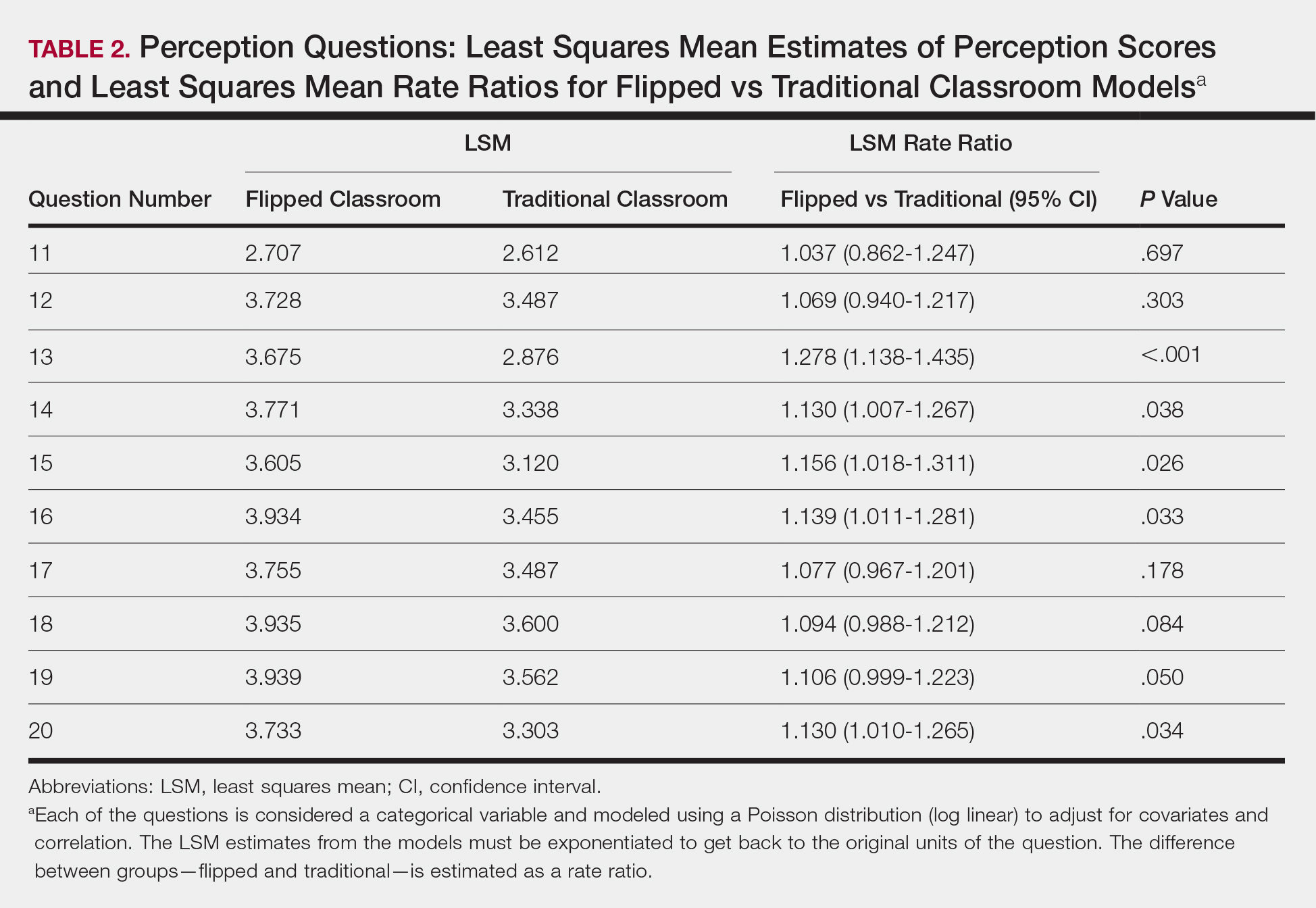

Each resident also answered 10 perception questions (Table 1). When comparing the responses by quiz type (Table 2), there was a significant difference for several questions in favor of the flipped classroom: how actively residents thought their co-residents participated in the lecture (P<.001), how much each resident enjoyed the session (P=.038), and how much each resident believed their co-residents enjoyed the session (P=.026). Additionally, residents thought that the flipped classroom sessions were more efficient (P=.033), better prepared them for boards (P=.050), and better prepared them for clinical practice (P=.034). There was not a significant difference in the amount of reading and preparation residents did for class (P=.697), how actively the residents thought they participated in the lecture (P=.303), the effectiveness of the day’s curriculum structure (P=.178), or whether residents thought the lesson increased their knowledge on the topic (P=.084).

Comment

The traditional model in medical education has undergone changes in recent years, and researchers have been looking for new ways to convey more information in shorter periods of time, especially as the field of medicine continues to expand. Despite the growing popularity and adoption of the flipped classroom, studies in dermatology have been limited. In this study, we compared a traditional classroom model with the flipped model, assessing both knowledge acquisition and resident perception of the experience.

There was not a significant difference in mean objective quiz scores when comparing the 2 curricula. The flipped model was not better or worse than the traditional teaching model at relaying information and promoting learning. Rather, there was a significant difference in quiz scores based on the individual resident and on the individual quiz. Individual performance was not affected by the teaching model but rather by the individual resident and lecture topic.

These findings differ from a study of internal medicine residents, which revealed that trainees in a quality-improvement flipped classroom had greater increases in knowledge than a traditional cohort.7 It is difficult to make direct comparisons to this group, given the difference in specialty and subject content. In comparison, an emergency medicine program completed a cross-sectional cohort study of in-service examination scores in the setting of a traditional curriculum (2011-2012) vs a flipped curriculum (2015-2016) and found that there was no statistical difference in average in-service examination scores.8 The type of examination content in this study may be more similar to the quizzes that our residents experienced (ie, fact-based material based on traditional medical knowledge).

The dermatology residents favored the flipped curriculum for 6 of 10 perception questions, which included areas of co-resident participation, personal and co-resident enjoyment, efficiency, boards preparation, and preparation for clinical practice. They did not favor the flipped classroom for prelecture preparation, personal participation, lecture effectiveness, or knowledge acquisition. They perceived their peers as being more engaged and found the flipped classroom to be a more positive experience. The residents thought that the flipped lectures were more time efficient, which could have contributed to overall learner satisfaction. Additionally, they thought that the flipped model better prepared them for both the boards and clinical practice, which are markers of future performance.

These findings are consistent with other studies that revealed improved postcourse perception scores for a quality improvement emergency medicine–flipped classroom. Most of this group preferred the flipped classroom over the traditional after completion of the flipped curriculum.9 A neurosurgery residency program also reported increased resident engagement and resident preference for a newly designed flipped curriculum.10

Overall, our data indicate that there was no objective change in knowledge acquisition at the time of the quiz, but learner satisfaction was significantly greater in the flipped classroom model.

Limitations

This study was comprised of a small number of residents from a single institution and was based on a limited number of lectures given throughout the year. All lectures during the study year were flipped with the exception of the 6 traditional study lectures. Therefore, each resident who presented a traditional lecture was not blinded for her individual assigned lecture. In addition, because traditional lectures only occurred on study days, once the lectures started, all trainees could predict that a content quiz would occur at the end of the session, which could potentially introduce bias toward better quiz performance for the traditional lectures.

Conclusion

When comparing traditional and flipped classroom models, we found no difference in knowledge acquisition. Rather, the difference in quiz scores was among individual residents. There was a significant positive difference in how residents perceived these teaching models, including enjoyment and feeling prepared for the boards. The flipped classroom model provides another opportunity to better engage residents during teaching and should be considered as part of dermatology residency education.

Acknowledgments

Duke Social Sciences Institute postdoctoral fellow Scott Clifford, PhD, and Duke Dermatology residents Daniel Chang, MD; Sinae Kane, MD; Rebecca Bialas, MD; Jolene Jewell, MD; Elizabeth Ju, MD; Michael Raisch, MD; Reed Garza, MD; Joanna Hooten, MD; and E. Schell Bressler, MD (all Durham, North Carolina)

- Lage MJ, Platt GJ, Treglia M. Inverting the classroom: a gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. J Economic Educ. 2000;31:30-43.

- Gillispie V. Using the flipped classroom to bridge the gap to generation Y. Ochsner J. 2016;16:32-36.

- Bergmann J, Sams A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Alexandria, VA: International Society for Technology in Education; 2012.

- Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013;88:1407-1410.

- Aughenbaugh WD. Dermatology flipped, blended and shaken: a comparison of the effect of an active learning modality on student learning, satisfaction, and teaching. Paper presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group 2013; September 27, 2013; Chicago, IL.

- Oppenheimer AJ, Pannucci CJ, Kasten SJ, et al. Survey says? A primer on web-based survey design and distribution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:299-304.

- Bonnes SL, Ratelle JT, Halvorsen AJ, et al. Flipping the quality improvement classroom in residency education. Acad Med. 2017;92:101-107.

- King AM, Mayer C, Barrie M, et al. Replacing lectures with small groups: the impact of flipping the residency conference day. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:11-17.

- Young TP, Bailey CJ, Guptill M, et al. The flipped classroom: a modality for mixed asynchronous and synchronous learning in a residency program. Western J Emerg Med. 2014;15:938-944.

- Girgis F, Miller JP. Implementation of a “flipped classroom” for neurosurgery resident education. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018;45:76-82.

The ideal method of resident education is a subject of great interest within the medical community, and many dermatology residency programs utilize a traditional classroom model for didactic training consisting of required textbook reading completed at home and classroom lectures that often include presentations featuring text, dermatology images, and questions throughout the lecture. A second teaching model is known as the flipped, or inverted, classroom. This model moves the didactic material that typically is covered in the classroom into the realm of home study or homework and focuses on application and clarification of the new material in the classroom. 1 There is an emphasis on completing and understanding course material prior to the classroom session. Students are expected to be prepared for the lesson, and the classroom session can include question review and deeper exploration of the topic with a focus on subject mastery. 2

In recent years, the flipped classroom model has been used in elementary education, due in part to the influence of teachers Bergmann and Sams,3 as described in their book Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. More recently, Prober and Khan4 argued for its use in medical education, and this model has been utilized in medical school curricula to teach specialty subjects, including medical dermatology.5

Given the increasing popularity and use of the flipped classroom, the primary objective of this study was to determine if a difference in knowledge acquisition and resident perception exists between the traditional and flipped classrooms. If differences do exist, the secondary aim was to quantify them. We hypothesized that the flipped classroom actively engages residents and would improve both knowledge acquisition and resident sentiment toward the residency program curriculum compared to the traditional model.

Methods

The Duke Health (Durham, North Carolina) institutional review board granted approval for this study. All of the dermatology residents from Duke University Medical Center for the 2014-2015 academic year participated in this study. Twelve individual lectures chosen by the dermatology residency program director were included: 6 traditional lectures and 6 flipped lectures. The lectures were paired for similar content.

Survey Administration

Each resident was assigned a unique 4-digit numeric code that was unknown to the investigators and recorded at the beginning of each survey. The residents expected flipped lectures for each session and were blinded as to when a traditional lecture and quiz would occur, with the exception of the resident providing the lecture. Classroom presentations were immediately followed by a voluntary survey administered through Qualtrics.6 Consent was given at the beginning of each survey, followed by 10 factual questions and 10 perception questions. The factual questions varied based on the lecture topic and were multiple-choice questions written by the program director, associate program director, and faculty. Each factual question was worth 10 points, and the scaled score for each quiz had a maximum value of 100. The perception questions were developed by the authors (J.H. and A.R.A.) in consultation with a survey methodology expert at the Duke Social Science Research Institute. These questions remained constant across each survey and were descriptive based on standard response scales. The data were extracted from Qualtrics for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The mean score with the standard deviation for each factual question quiz was calculated and plotted. A generalized linear mixed model was created to study the difference in quiz scores between the 2 classroom models after adjusting for other covariates, including resident, the interaction between resident and class type, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was specified as a random variable, and a variance components covariance structure was used. For the perception questions, the frequency and percentage of each answer for a question was counted. Generalized linear mixed models with a Poisson distribution were created to study the difference in answers for each survey question between the 2 curriculum types after adjusting for other covariates, including scores for factual questions, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was again specified as a random variable, and a diagonal covariance structure was used. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute) by the Duke University Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All 9 of the department’s residents were included and participated in this study. Mean score with standard deviation for each factual quiz is plotted in the Figure. Across all residents, the mean factual quiz score was slightly higher but not statistically significant in the flipped vs traditional classrooms (67.5% vs 65.4%; P=.448)(data not shown). When comparing traditional and flipped factual quiz scores by individual resident, there was not a significant difference in quiz performance (P=.166)(data not shown). However, there was a significant difference in the factual quiz scores among residents for all quizzes (P=.005) as well as a significant difference in performance between each individual quiz over time (P<.001)(data not shown). In the traditional classroom, residents demonstrated a trend in variable performance with each factual quiz. In the flipped classroom, residents also had variable performance, with wide-ranging scores (P=.008)(data not shown).

Each resident also answered 10 perception questions (Table 1). When comparing the responses by quiz type (Table 2), there was a significant difference for several questions in favor of the flipped classroom: how actively residents thought their co-residents participated in the lecture (P<.001), how much each resident enjoyed the session (P=.038), and how much each resident believed their co-residents enjoyed the session (P=.026). Additionally, residents thought that the flipped classroom sessions were more efficient (P=.033), better prepared them for boards (P=.050), and better prepared them for clinical practice (P=.034). There was not a significant difference in the amount of reading and preparation residents did for class (P=.697), how actively the residents thought they participated in the lecture (P=.303), the effectiveness of the day’s curriculum structure (P=.178), or whether residents thought the lesson increased their knowledge on the topic (P=.084).

Comment

The traditional model in medical education has undergone changes in recent years, and researchers have been looking for new ways to convey more information in shorter periods of time, especially as the field of medicine continues to expand. Despite the growing popularity and adoption of the flipped classroom, studies in dermatology have been limited. In this study, we compared a traditional classroom model with the flipped model, assessing both knowledge acquisition and resident perception of the experience.

There was not a significant difference in mean objective quiz scores when comparing the 2 curricula. The flipped model was not better or worse than the traditional teaching model at relaying information and promoting learning. Rather, there was a significant difference in quiz scores based on the individual resident and on the individual quiz. Individual performance was not affected by the teaching model but rather by the individual resident and lecture topic.

These findings differ from a study of internal medicine residents, which revealed that trainees in a quality-improvement flipped classroom had greater increases in knowledge than a traditional cohort.7 It is difficult to make direct comparisons to this group, given the difference in specialty and subject content. In comparison, an emergency medicine program completed a cross-sectional cohort study of in-service examination scores in the setting of a traditional curriculum (2011-2012) vs a flipped curriculum (2015-2016) and found that there was no statistical difference in average in-service examination scores.8 The type of examination content in this study may be more similar to the quizzes that our residents experienced (ie, fact-based material based on traditional medical knowledge).

The dermatology residents favored the flipped curriculum for 6 of 10 perception questions, which included areas of co-resident participation, personal and co-resident enjoyment, efficiency, boards preparation, and preparation for clinical practice. They did not favor the flipped classroom for prelecture preparation, personal participation, lecture effectiveness, or knowledge acquisition. They perceived their peers as being more engaged and found the flipped classroom to be a more positive experience. The residents thought that the flipped lectures were more time efficient, which could have contributed to overall learner satisfaction. Additionally, they thought that the flipped model better prepared them for both the boards and clinical practice, which are markers of future performance.

These findings are consistent with other studies that revealed improved postcourse perception scores for a quality improvement emergency medicine–flipped classroom. Most of this group preferred the flipped classroom over the traditional after completion of the flipped curriculum.9 A neurosurgery residency program also reported increased resident engagement and resident preference for a newly designed flipped curriculum.10

Overall, our data indicate that there was no objective change in knowledge acquisition at the time of the quiz, but learner satisfaction was significantly greater in the flipped classroom model.

Limitations

This study was comprised of a small number of residents from a single institution and was based on a limited number of lectures given throughout the year. All lectures during the study year were flipped with the exception of the 6 traditional study lectures. Therefore, each resident who presented a traditional lecture was not blinded for her individual assigned lecture. In addition, because traditional lectures only occurred on study days, once the lectures started, all trainees could predict that a content quiz would occur at the end of the session, which could potentially introduce bias toward better quiz performance for the traditional lectures.

Conclusion

When comparing traditional and flipped classroom models, we found no difference in knowledge acquisition. Rather, the difference in quiz scores was among individual residents. There was a significant positive difference in how residents perceived these teaching models, including enjoyment and feeling prepared for the boards. The flipped classroom model provides another opportunity to better engage residents during teaching and should be considered as part of dermatology residency education.

Acknowledgments

Duke Social Sciences Institute postdoctoral fellow Scott Clifford, PhD, and Duke Dermatology residents Daniel Chang, MD; Sinae Kane, MD; Rebecca Bialas, MD; Jolene Jewell, MD; Elizabeth Ju, MD; Michael Raisch, MD; Reed Garza, MD; Joanna Hooten, MD; and E. Schell Bressler, MD (all Durham, North Carolina)

The ideal method of resident education is a subject of great interest within the medical community, and many dermatology residency programs utilize a traditional classroom model for didactic training consisting of required textbook reading completed at home and classroom lectures that often include presentations featuring text, dermatology images, and questions throughout the lecture. A second teaching model is known as the flipped, or inverted, classroom. This model moves the didactic material that typically is covered in the classroom into the realm of home study or homework and focuses on application and clarification of the new material in the classroom. 1 There is an emphasis on completing and understanding course material prior to the classroom session. Students are expected to be prepared for the lesson, and the classroom session can include question review and deeper exploration of the topic with a focus on subject mastery. 2

In recent years, the flipped classroom model has been used in elementary education, due in part to the influence of teachers Bergmann and Sams,3 as described in their book Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. More recently, Prober and Khan4 argued for its use in medical education, and this model has been utilized in medical school curricula to teach specialty subjects, including medical dermatology.5

Given the increasing popularity and use of the flipped classroom, the primary objective of this study was to determine if a difference in knowledge acquisition and resident perception exists between the traditional and flipped classrooms. If differences do exist, the secondary aim was to quantify them. We hypothesized that the flipped classroom actively engages residents and would improve both knowledge acquisition and resident sentiment toward the residency program curriculum compared to the traditional model.

Methods

The Duke Health (Durham, North Carolina) institutional review board granted approval for this study. All of the dermatology residents from Duke University Medical Center for the 2014-2015 academic year participated in this study. Twelve individual lectures chosen by the dermatology residency program director were included: 6 traditional lectures and 6 flipped lectures. The lectures were paired for similar content.

Survey Administration

Each resident was assigned a unique 4-digit numeric code that was unknown to the investigators and recorded at the beginning of each survey. The residents expected flipped lectures for each session and were blinded as to when a traditional lecture and quiz would occur, with the exception of the resident providing the lecture. Classroom presentations were immediately followed by a voluntary survey administered through Qualtrics.6 Consent was given at the beginning of each survey, followed by 10 factual questions and 10 perception questions. The factual questions varied based on the lecture topic and were multiple-choice questions written by the program director, associate program director, and faculty. Each factual question was worth 10 points, and the scaled score for each quiz had a maximum value of 100. The perception questions were developed by the authors (J.H. and A.R.A.) in consultation with a survey methodology expert at the Duke Social Science Research Institute. These questions remained constant across each survey and were descriptive based on standard response scales. The data were extracted from Qualtrics for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The mean score with the standard deviation for each factual question quiz was calculated and plotted. A generalized linear mixed model was created to study the difference in quiz scores between the 2 classroom models after adjusting for other covariates, including resident, the interaction between resident and class type, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was specified as a random variable, and a variance components covariance structure was used. For the perception questions, the frequency and percentage of each answer for a question was counted. Generalized linear mixed models with a Poisson distribution were created to study the difference in answers for each survey question between the 2 curriculum types after adjusting for other covariates, including scores for factual questions, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was again specified as a random variable, and a diagonal covariance structure was used. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute) by the Duke University Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All 9 of the department’s residents were included and participated in this study. Mean score with standard deviation for each factual quiz is plotted in the Figure. Across all residents, the mean factual quiz score was slightly higher but not statistically significant in the flipped vs traditional classrooms (67.5% vs 65.4%; P=.448)(data not shown). When comparing traditional and flipped factual quiz scores by individual resident, there was not a significant difference in quiz performance (P=.166)(data not shown). However, there was a significant difference in the factual quiz scores among residents for all quizzes (P=.005) as well as a significant difference in performance between each individual quiz over time (P<.001)(data not shown). In the traditional classroom, residents demonstrated a trend in variable performance with each factual quiz. In the flipped classroom, residents also had variable performance, with wide-ranging scores (P=.008)(data not shown).

Each resident also answered 10 perception questions (Table 1). When comparing the responses by quiz type (Table 2), there was a significant difference for several questions in favor of the flipped classroom: how actively residents thought their co-residents participated in the lecture (P<.001), how much each resident enjoyed the session (P=.038), and how much each resident believed their co-residents enjoyed the session (P=.026). Additionally, residents thought that the flipped classroom sessions were more efficient (P=.033), better prepared them for boards (P=.050), and better prepared them for clinical practice (P=.034). There was not a significant difference in the amount of reading and preparation residents did for class (P=.697), how actively the residents thought they participated in the lecture (P=.303), the effectiveness of the day’s curriculum structure (P=.178), or whether residents thought the lesson increased their knowledge on the topic (P=.084).

Comment

The traditional model in medical education has undergone changes in recent years, and researchers have been looking for new ways to convey more information in shorter periods of time, especially as the field of medicine continues to expand. Despite the growing popularity and adoption of the flipped classroom, studies in dermatology have been limited. In this study, we compared a traditional classroom model with the flipped model, assessing both knowledge acquisition and resident perception of the experience.

There was not a significant difference in mean objective quiz scores when comparing the 2 curricula. The flipped model was not better or worse than the traditional teaching model at relaying information and promoting learning. Rather, there was a significant difference in quiz scores based on the individual resident and on the individual quiz. Individual performance was not affected by the teaching model but rather by the individual resident and lecture topic.

These findings differ from a study of internal medicine residents, which revealed that trainees in a quality-improvement flipped classroom had greater increases in knowledge than a traditional cohort.7 It is difficult to make direct comparisons to this group, given the difference in specialty and subject content. In comparison, an emergency medicine program completed a cross-sectional cohort study of in-service examination scores in the setting of a traditional curriculum (2011-2012) vs a flipped curriculum (2015-2016) and found that there was no statistical difference in average in-service examination scores.8 The type of examination content in this study may be more similar to the quizzes that our residents experienced (ie, fact-based material based on traditional medical knowledge).

The dermatology residents favored the flipped curriculum for 6 of 10 perception questions, which included areas of co-resident participation, personal and co-resident enjoyment, efficiency, boards preparation, and preparation for clinical practice. They did not favor the flipped classroom for prelecture preparation, personal participation, lecture effectiveness, or knowledge acquisition. They perceived their peers as being more engaged and found the flipped classroom to be a more positive experience. The residents thought that the flipped lectures were more time efficient, which could have contributed to overall learner satisfaction. Additionally, they thought that the flipped model better prepared them for both the boards and clinical practice, which are markers of future performance.

These findings are consistent with other studies that revealed improved postcourse perception scores for a quality improvement emergency medicine–flipped classroom. Most of this group preferred the flipped classroom over the traditional after completion of the flipped curriculum.9 A neurosurgery residency program also reported increased resident engagement and resident preference for a newly designed flipped curriculum.10

Overall, our data indicate that there was no objective change in knowledge acquisition at the time of the quiz, but learner satisfaction was significantly greater in the flipped classroom model.

Limitations

This study was comprised of a small number of residents from a single institution and was based on a limited number of lectures given throughout the year. All lectures during the study year were flipped with the exception of the 6 traditional study lectures. Therefore, each resident who presented a traditional lecture was not blinded for her individual assigned lecture. In addition, because traditional lectures only occurred on study days, once the lectures started, all trainees could predict that a content quiz would occur at the end of the session, which could potentially introduce bias toward better quiz performance for the traditional lectures.

Conclusion

When comparing traditional and flipped classroom models, we found no difference in knowledge acquisition. Rather, the difference in quiz scores was among individual residents. There was a significant positive difference in how residents perceived these teaching models, including enjoyment and feeling prepared for the boards. The flipped classroom model provides another opportunity to better engage residents during teaching and should be considered as part of dermatology residency education.

Acknowledgments

Duke Social Sciences Institute postdoctoral fellow Scott Clifford, PhD, and Duke Dermatology residents Daniel Chang, MD; Sinae Kane, MD; Rebecca Bialas, MD; Jolene Jewell, MD; Elizabeth Ju, MD; Michael Raisch, MD; Reed Garza, MD; Joanna Hooten, MD; and E. Schell Bressler, MD (all Durham, North Carolina)

- Lage MJ, Platt GJ, Treglia M. Inverting the classroom: a gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. J Economic Educ. 2000;31:30-43.

- Gillispie V. Using the flipped classroom to bridge the gap to generation Y. Ochsner J. 2016;16:32-36.

- Bergmann J, Sams A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Alexandria, VA: International Society for Technology in Education; 2012.

- Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013;88:1407-1410.

- Aughenbaugh WD. Dermatology flipped, blended and shaken: a comparison of the effect of an active learning modality on student learning, satisfaction, and teaching. Paper presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group 2013; September 27, 2013; Chicago, IL.

- Oppenheimer AJ, Pannucci CJ, Kasten SJ, et al. Survey says? A primer on web-based survey design and distribution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:299-304.

- Bonnes SL, Ratelle JT, Halvorsen AJ, et al. Flipping the quality improvement classroom in residency education. Acad Med. 2017;92:101-107.

- King AM, Mayer C, Barrie M, et al. Replacing lectures with small groups: the impact of flipping the residency conference day. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:11-17.

- Young TP, Bailey CJ, Guptill M, et al. The flipped classroom: a modality for mixed asynchronous and synchronous learning in a residency program. Western J Emerg Med. 2014;15:938-944.

- Girgis F, Miller JP. Implementation of a “flipped classroom” for neurosurgery resident education. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018;45:76-82.

- Lage MJ, Platt GJ, Treglia M. Inverting the classroom: a gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. J Economic Educ. 2000;31:30-43.

- Gillispie V. Using the flipped classroom to bridge the gap to generation Y. Ochsner J. 2016;16:32-36.

- Bergmann J, Sams A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Alexandria, VA: International Society for Technology in Education; 2012.

- Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013;88:1407-1410.

- Aughenbaugh WD. Dermatology flipped, blended and shaken: a comparison of the effect of an active learning modality on student learning, satisfaction, and teaching. Paper presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group 2013; September 27, 2013; Chicago, IL.

- Oppenheimer AJ, Pannucci CJ, Kasten SJ, et al. Survey says? A primer on web-based survey design and distribution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:299-304.

- Bonnes SL, Ratelle JT, Halvorsen AJ, et al. Flipping the quality improvement classroom in residency education. Acad Med. 2017;92:101-107.

- King AM, Mayer C, Barrie M, et al. Replacing lectures with small groups: the impact of flipping the residency conference day. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:11-17.

- Young TP, Bailey CJ, Guptill M, et al. The flipped classroom: a modality for mixed asynchronous and synchronous learning in a residency program. Western J Emerg Med. 2014;15:938-944.

- Girgis F, Miller JP. Implementation of a “flipped classroom” for neurosurgery resident education. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018;45:76-82.

Practice Points

- There was not a significant difference in dermatology resident factual quiz scores when comparing flipped vs traditional classroom teaching sessions.

- There was a significant difference between the flipped vs traditional teaching models, with dermatology residents favoring the flipped classroom, for co-resident lecture participation and individual and co-resident enjoyment of the lecture.

- Residents also perceived that the flipped classroom sessions were more efficient, better prepared them for boards, and better prepared them for clinical practice.

Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris and Severe Hypereosinophilia

To the Editor:

A 63-year-old man presented with a prior diagnosis of severe psoriasis affecting the extremities, neck, face, and scalp of 1 year’s duration. He reported pain, itching, and swelling in the affected areas. He felt the rash was worst on the hands and feet, and pain made performing activities of daily living difficult. His treatment regimen at presentation included triamcinolone cream 0.1% and azathioprine 150 mg daily as prescribed by an outside dermatologist without any response. Physical examination revealed diffuse erythema with lichenification and thick, white, flaking scale on the arms and legs (Figure 1A), face, neck, palms, and soles with islands of sparing. Multiple salmon-colored, follicular-based papules topped with central hyperkeratosis were scattered on these same areas. The palms and soles had severe confluent keratoderma (Figure 2A). Histologic examination of a follicular-based papule showed foci of parakeratosis and hypergranulosis consistent with the patient’s clinical picture of pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP).

Baseline laboratory tests at the time of PRP diagnosis revealed 20.8% eosinophils (reference range, 0%–7%) and an absolute eosinophil count of 2.17×109/L (reference range, 0–0.7×109/L). Laboratory test results from an outside dermatologist conducted 10 to 12 months prior to the current presentation showed 12% eosinophils with a white blood cell count of 8.9×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) around the time of rash onset and before treatment with azathioprine, making a drug reaction an unlikely cause of the eosinophilia.

After consulting with the hematology department, a hypereosinophilia workup including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, lactate dehydrogenase, serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, tryptase, double-stranded DNA antibody, human T-lymphotrophic virus I/II, stool ova, and parasites, as well as a Strongyloides antibody titer, were performed; all were within reference range. His antinuclear antibody level was mildly elevated at 1:160, but the patient had no clinical manifestations of lupus. Given this negative workup, the most likely explanation for the hypereosinophilia was a reactive process secondary to the extreme inflammatory state.

The patient was started on isotretinoin 40 mg daily in addition to urea cream 40% mixed with clobetasol ointment at least once daily to the extremities. Hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% and petrolatum-based ointment were applied to the face, and hydroxyzine was used as needed for pruritus. One month after initiating isotretinoin, erythema had decreased and a repeat complete blood cell count with differential showed a decrease of eosinophils to 14.7% and an absolute eosinophil count of 1.56×109/L. After 2 months of therapy, the patient showed remarkable improvement. After 3.5 months of therapy, the keratoderma on the palms and soles was almost completely resolved, the follicular-based papules disappeared, and the patient had no areas of lichenification (Figures 1B and 2B). After 5 months of therapy, the patient experienced resolution of the PRP, except for residual facial erythema. His eosinophil count continued to trend downward during these 5 months, reaching 7.6% with an absolute eosinophil count of 0.93×109/L. Three years after the initial onset of the rash and 2 years after completing isotretinoin, his eosinophil level was normal at 5.3% with an absolute eosinophil count of 0.7×109/L.

We present a case of PRP and severe eosinophilia. We initially considered a second disease process to explain the extremely elevated eosinophil count; however, a negative eosinophilia workup and simultaneous resolution of these problems suggest that the eosinophilia was related to the severity of the PRP.

To the Editor:

A 63-year-old man presented with a prior diagnosis of severe psoriasis affecting the extremities, neck, face, and scalp of 1 year’s duration. He reported pain, itching, and swelling in the affected areas. He felt the rash was worst on the hands and feet, and pain made performing activities of daily living difficult. His treatment regimen at presentation included triamcinolone cream 0.1% and azathioprine 150 mg daily as prescribed by an outside dermatologist without any response. Physical examination revealed diffuse erythema with lichenification and thick, white, flaking scale on the arms and legs (Figure 1A), face, neck, palms, and soles with islands of sparing. Multiple salmon-colored, follicular-based papules topped with central hyperkeratosis were scattered on these same areas. The palms and soles had severe confluent keratoderma (Figure 2A). Histologic examination of a follicular-based papule showed foci of parakeratosis and hypergranulosis consistent with the patient’s clinical picture of pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP).

Baseline laboratory tests at the time of PRP diagnosis revealed 20.8% eosinophils (reference range, 0%–7%) and an absolute eosinophil count of 2.17×109/L (reference range, 0–0.7×109/L). Laboratory test results from an outside dermatologist conducted 10 to 12 months prior to the current presentation showed 12% eosinophils with a white blood cell count of 8.9×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) around the time of rash onset and before treatment with azathioprine, making a drug reaction an unlikely cause of the eosinophilia.

After consulting with the hematology department, a hypereosinophilia workup including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, lactate dehydrogenase, serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, tryptase, double-stranded DNA antibody, human T-lymphotrophic virus I/II, stool ova, and parasites, as well as a Strongyloides antibody titer, were performed; all were within reference range. His antinuclear antibody level was mildly elevated at 1:160, but the patient had no clinical manifestations of lupus. Given this negative workup, the most likely explanation for the hypereosinophilia was a reactive process secondary to the extreme inflammatory state.

The patient was started on isotretinoin 40 mg daily in addition to urea cream 40% mixed with clobetasol ointment at least once daily to the extremities. Hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% and petrolatum-based ointment were applied to the face, and hydroxyzine was used as needed for pruritus. One month after initiating isotretinoin, erythema had decreased and a repeat complete blood cell count with differential showed a decrease of eosinophils to 14.7% and an absolute eosinophil count of 1.56×109/L. After 2 months of therapy, the patient showed remarkable improvement. After 3.5 months of therapy, the keratoderma on the palms and soles was almost completely resolved, the follicular-based papules disappeared, and the patient had no areas of lichenification (Figures 1B and 2B). After 5 months of therapy, the patient experienced resolution of the PRP, except for residual facial erythema. His eosinophil count continued to trend downward during these 5 months, reaching 7.6% with an absolute eosinophil count of 0.93×109/L. Three years after the initial onset of the rash and 2 years after completing isotretinoin, his eosinophil level was normal at 5.3% with an absolute eosinophil count of 0.7×109/L.

We present a case of PRP and severe eosinophilia. We initially considered a second disease process to explain the extremely elevated eosinophil count; however, a negative eosinophilia workup and simultaneous resolution of these problems suggest that the eosinophilia was related to the severity of the PRP.

To the Editor:

A 63-year-old man presented with a prior diagnosis of severe psoriasis affecting the extremities, neck, face, and scalp of 1 year’s duration. He reported pain, itching, and swelling in the affected areas. He felt the rash was worst on the hands and feet, and pain made performing activities of daily living difficult. His treatment regimen at presentation included triamcinolone cream 0.1% and azathioprine 150 mg daily as prescribed by an outside dermatologist without any response. Physical examination revealed diffuse erythema with lichenification and thick, white, flaking scale on the arms and legs (Figure 1A), face, neck, palms, and soles with islands of sparing. Multiple salmon-colored, follicular-based papules topped with central hyperkeratosis were scattered on these same areas. The palms and soles had severe confluent keratoderma (Figure 2A). Histologic examination of a follicular-based papule showed foci of parakeratosis and hypergranulosis consistent with the patient’s clinical picture of pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP).

Baseline laboratory tests at the time of PRP diagnosis revealed 20.8% eosinophils (reference range, 0%–7%) and an absolute eosinophil count of 2.17×109/L (reference range, 0–0.7×109/L). Laboratory test results from an outside dermatologist conducted 10 to 12 months prior to the current presentation showed 12% eosinophils with a white blood cell count of 8.9×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) around the time of rash onset and before treatment with azathioprine, making a drug reaction an unlikely cause of the eosinophilia.

After consulting with the hematology department, a hypereosinophilia workup including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, lactate dehydrogenase, serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, tryptase, double-stranded DNA antibody, human T-lymphotrophic virus I/II, stool ova, and parasites, as well as a Strongyloides antibody titer, were performed; all were within reference range. His antinuclear antibody level was mildly elevated at 1:160, but the patient had no clinical manifestations of lupus. Given this negative workup, the most likely explanation for the hypereosinophilia was a reactive process secondary to the extreme inflammatory state.

The patient was started on isotretinoin 40 mg daily in addition to urea cream 40% mixed with clobetasol ointment at least once daily to the extremities. Hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% and petrolatum-based ointment were applied to the face, and hydroxyzine was used as needed for pruritus. One month after initiating isotretinoin, erythema had decreased and a repeat complete blood cell count with differential showed a decrease of eosinophils to 14.7% and an absolute eosinophil count of 1.56×109/L. After 2 months of therapy, the patient showed remarkable improvement. After 3.5 months of therapy, the keratoderma on the palms and soles was almost completely resolved, the follicular-based papules disappeared, and the patient had no areas of lichenification (Figures 1B and 2B). After 5 months of therapy, the patient experienced resolution of the PRP, except for residual facial erythema. His eosinophil count continued to trend downward during these 5 months, reaching 7.6% with an absolute eosinophil count of 0.93×109/L. Three years after the initial onset of the rash and 2 years after completing isotretinoin, his eosinophil level was normal at 5.3% with an absolute eosinophil count of 0.7×109/L.

We present a case of PRP and severe eosinophilia. We initially considered a second disease process to explain the extremely elevated eosinophil count; however, a negative eosinophilia workup and simultaneous resolution of these problems suggest that the eosinophilia was related to the severity of the PRP.

Practice Points

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) can clinically mimic psoriasis. Look for islands of sparing and palmar and plantar hyperkeratosis to help diagnose PRP. A biopsy may be useful to help with this differentiation.

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris may be associated with eosinophilia, but one should rule out other causes of eosinophilia first.