User login

Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer

Dermoscopy, the use of a handheld instrument to magnify the skin 10-fold while providing a light source, is a quick, useful, cost-effective tool for detecting melanoma in family medicine.1-4 The device, which allows the physician to visualize structures below the stratum corneum that are not routinely discernible with the naked eye, can be attached to a smartphone so that photos can be taken and reviewed with the patient. The photo can also be reviewed after a biopsy result is obtained.

Its use among non-dermatologist US physicians appears to be relatively low, but rising. One small study of physicians working in family medicine, internal medicine, and plastic surgery found that only 15% had ever used a dermatoscope and 6% were currently using one.5

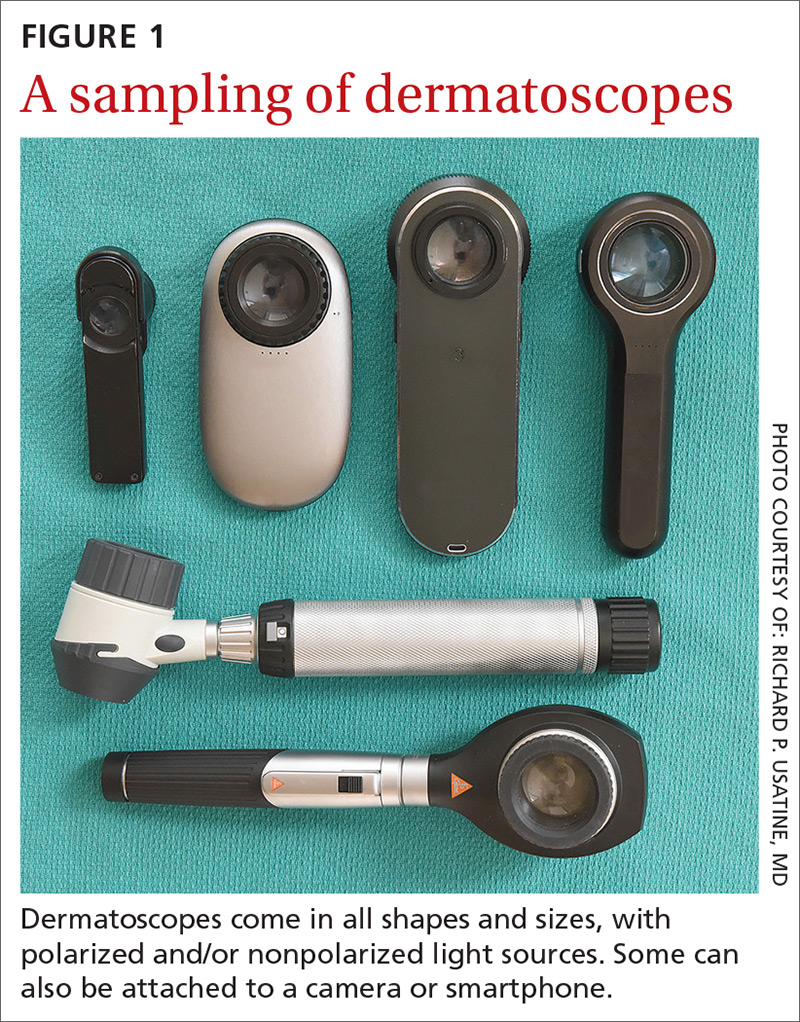

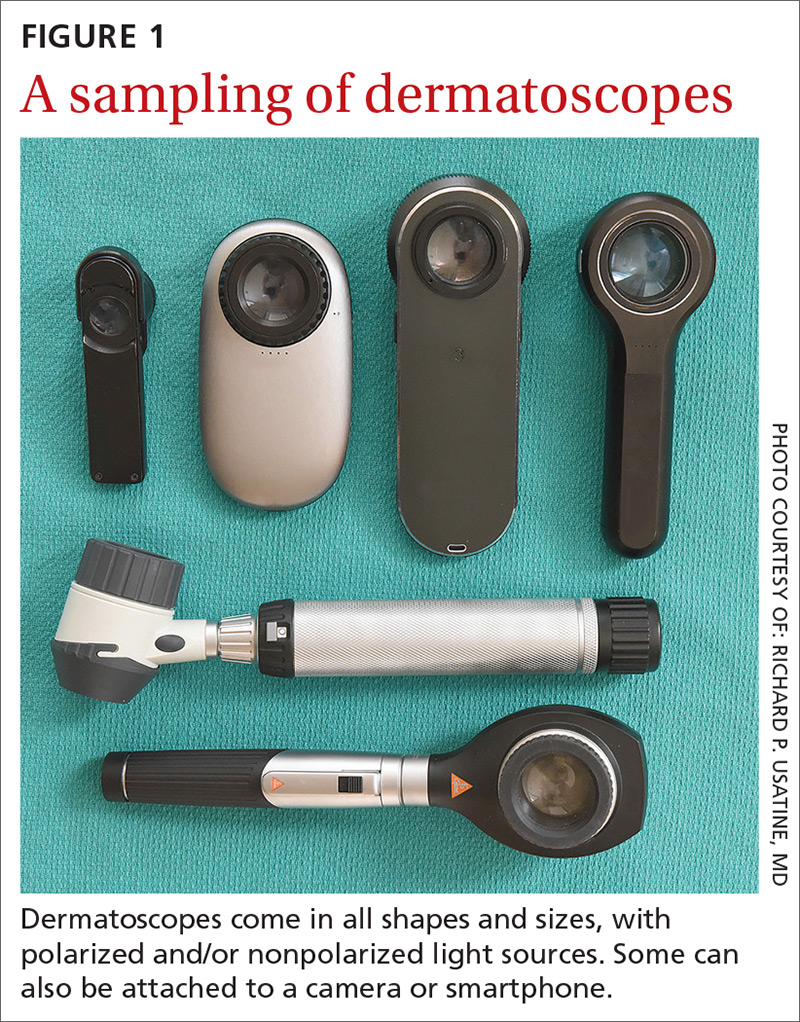

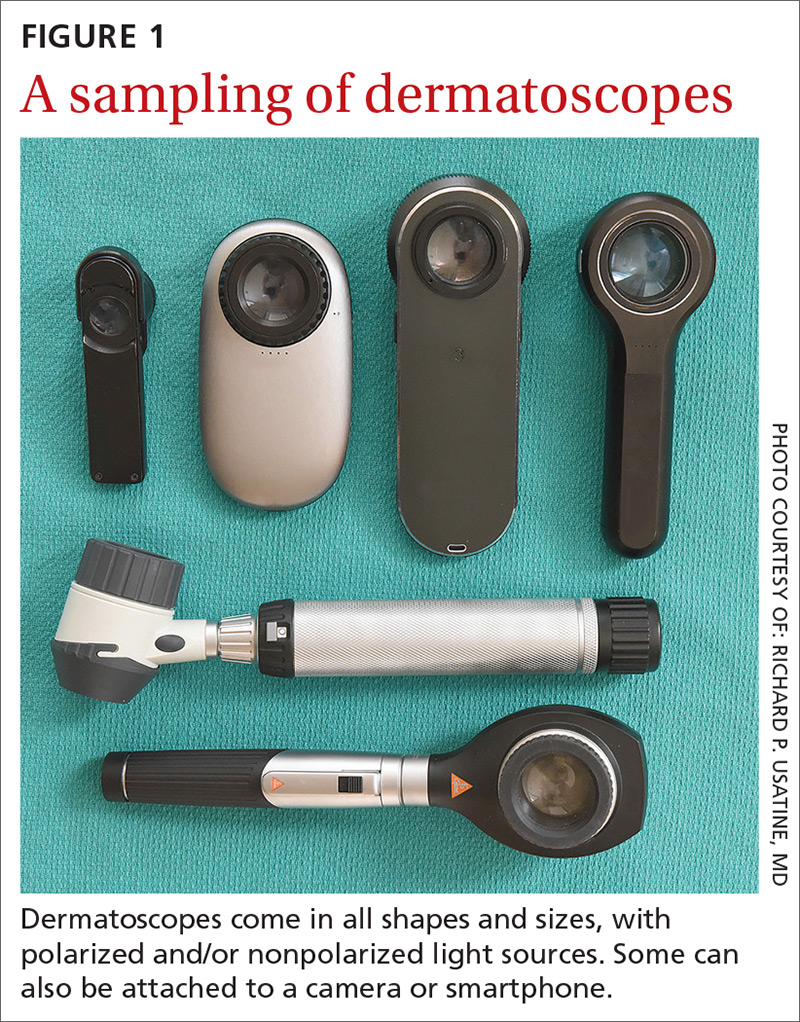

As a family physician, you can expand your diagnostic abilities in dermatology with the acquisition of a dermatoscope (FIGURE 1) and some time invested in learning to interpret visible patterns. With that in mind, this review focuses on the diagnosis of skin cancers and benign growths using dermoscopy. We begin with a brief look at the research on dermoscopy and how it is performed. From there, we’ll detail an algorithm to guide dermoscopic analysis. And to round things out, we provide guidance that will help you to get started. (See “Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it,” and “To learn more about dermoscopy …”.)

SIDEBAR

Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it

1. Consider acquiring a hybrid dermatoscope.

Nonpolarized dermatoscopes (NPDs) and polarized dermatoscopes (PDs) provide different but complementary information. PDs enable users to identify features such as vessels and shiny white structures that are highly indicative of skin cancer. Because PDs are highly sensitive for detecting skin cancer and do not require a liquid interface or direct skin contact, they are the ideal dermatoscopes to use for skin cancer screening.

However, maintaining the highest specificity requires the complementary use of NPDs, which are better at identifying surface structures seen in seborrheic keratoses and other benign lesions. Thus, if the aim is to maintain the highest diagnostic accuracy for all types of lesions, then the preferred dermatoscope is a hybrid that permits the user to toggle between polarized and nonpolarized features in one device.

2. Choose a dermatoscope that attaches to your smartphone and/or camera.

This helps you capture digital dermoscopic images that can be analyzed on a larger screen, which permits:

- enlarging certain areas for in-depth analysis of structures and patterns

- sharing the image with the patient to explain why a biopsy is, or isn’t, needed

- sharing the image with a colleague for the purpose of a consult or a referral, or using the images for teaching purposes

- saving the images in order to follow lesions over time when monitoring is indicated

- ongoing learning. After each biopsy result comes back, we recommend correlating the dermoscopic images with the biopsy report. If your suspected diagnosis was correct, this reinforces your knowledge. If the pathology diagnosis is unexpected, you can learn by revisiting the original images to look for structures or patterns you may have missed upon first examination. You may even question the pathology report based on the dermoscopy, prompting a call to the pathologist.

- keeping a safe distance from the patient when looking for scabies mites.

SIDEBAR

To learn more about dermoscopy…

FREE APPS:

Dermoscopy 2-Step Algorithm. Available for free on iTunes, Google Play, and at https://usatinemedia.com/app/dermoscopy-two-step-algorithm/, this free app (developed by 3 of the 4 authors) is intended to help you interpret the dermoscopic patterns seen with your dermatoscope. It asks a series of questions that lead you to the most probable diagnosis. The app also contains more than 80 photos and charts to help you with your diagnosis. No Internet connection is needed to view the full app. There are 50 interactive cases to solve.

YOUdermoscopy Training (Available for free on iTunes, Google Play, and at https://www.youdermoscopytraining.org/) offers a fun game interface to test and expand your dermoscopy skills.

OTHER INTERNET RESOURCES:

- Dermoscopedia provides state-of-the-art information on dermoscopy. It’s available at: https://dermoscopedia.org.

- A free dermoscopy tutorial is available at: http://www.dermoscopy.org/

- The International Dermoscopy Society’s Web site, which offers various tutorials and other information, can be found at: http://www.dermoscopy-ids.org/.

COURSES:

Dermoscopy courses are a great way to get started and/or to advance your skills. The following courses are taught by the authors of this article:

- The American Dermoscopy Meeting is held yearly in the summer in a national park. See http://www.americandermoscopy.com/.

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center holds a yearly dermoscopy workshop each fall in New York City. See http://www.mskcc.org/events/.

- The yearly American Academy of Family Physicians' FMX meeting offers dermoscopy workshops. See https://www.aafp.org/events/fmx.html.

Continue to: What the research says

What the research says

Dermoscopy improves sensitivity for detecting melanoma over the naked eye alone; it also allows for the detection of melanoma at earlier stages, which improves prognosis.6

A meta-analysis of dermoscopy use in clinical settings showed that, following training, dermoscopy increases the average sensitivity of melanoma diagnosis from 71% to more than 90% without a significant decrease in specificity.7 In a study of 74 primary care physicians, there was an improvement in both clinical and dermoscopic diagnosis of melanoma among those who received training in dermoscopy, compared with a control group.8 Another study found that primary care physicians can reduce their baseline benign-to-melanoma ratio (the number of suspicious benign lesions biopsied to find 1 melanoma) from 9.5:1 with naked eye examination to 3.5:1 with dermoscopy.9

The exam begins by choosing 1 of 3 modes of dermoscopy

Dermatoscopes can have a polarized or nonpolarized light source. Some dermatoscopes combine both types of light (hybrid dermatoscopes; see “Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it.”)

There are 3 modes of dermoscopy:

- nonpolarized contact dermoscopy

- polarized contact dermoscopy

- polarized non-contact dermoscopy.

Dermatoscopes with nonpolarized light require direct skin contact and a liquid interface (eg, alcohol, gel, mineral oil) between the scope’s glass plate and the skin for the visualization of subsurface structures. In contrast, dermatoscopes with polarized light do not require direct skin contact or a liquid interface; however, contacting the skin and using a liquid interface will provide a sharper image.

Continue to: Two major algorithms guide dermoscopic analysis

Two major algorithms guide dermoscopic analysis

The first of 2 major algorithms that can be used to guide dermoscopic analysis is a modified pattern analysis put forth by Kittler.10 This descriptive system based on geometric elements, patterns, colors, and clues guides the observer to a specific diagnosis without categorizing lesions as being either melanocytic or nonmelanocytic. Because this is not the preferred method of the authors, we will move on to Method 2.

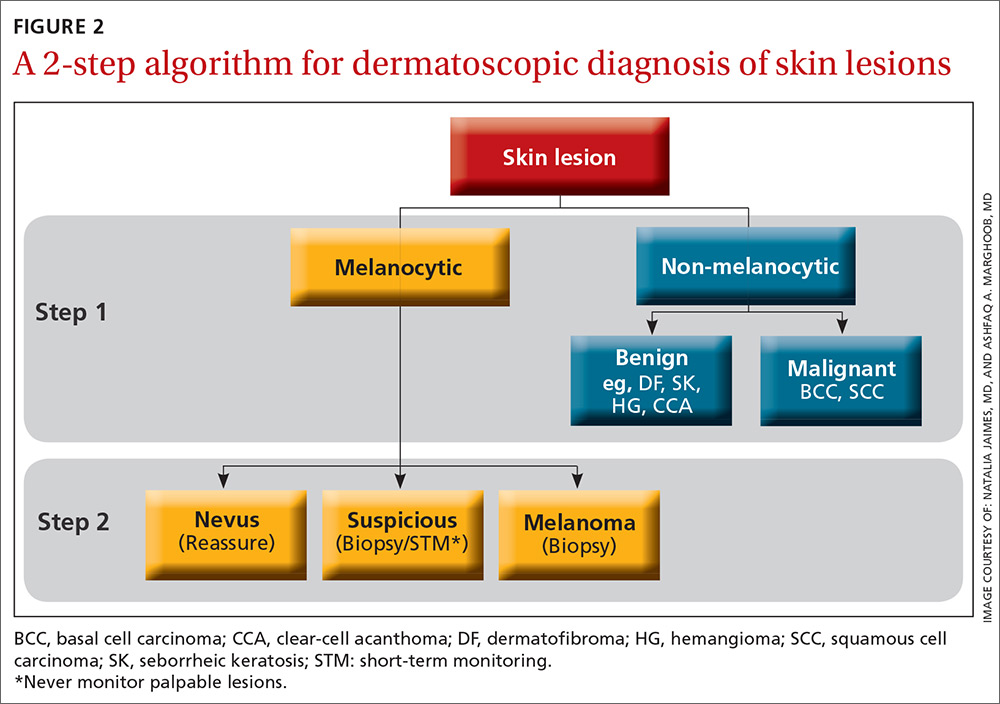

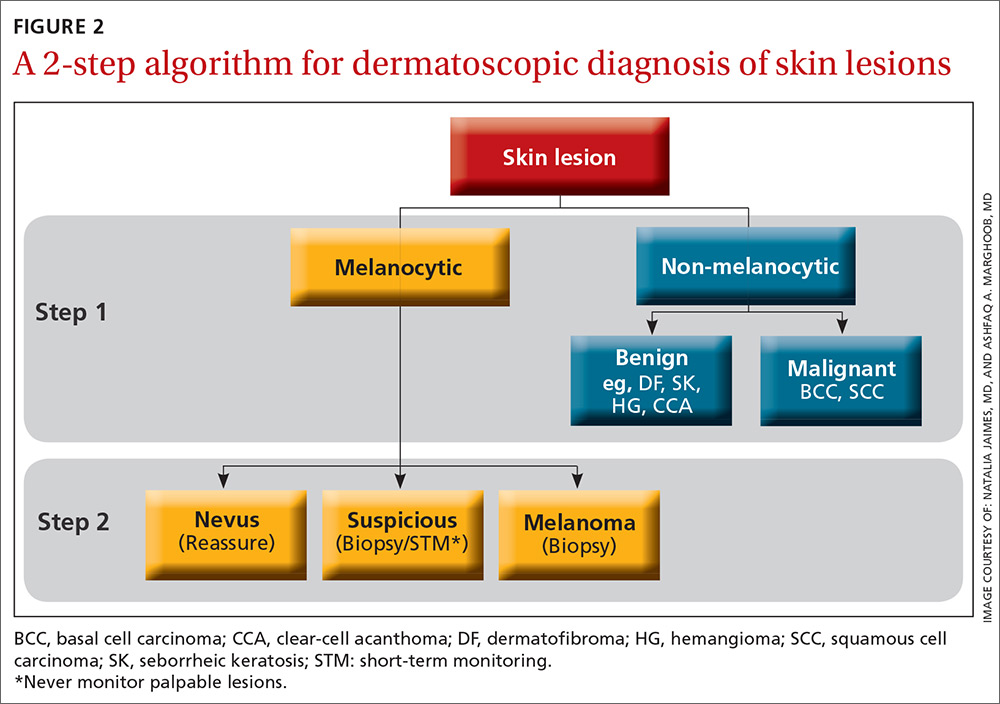

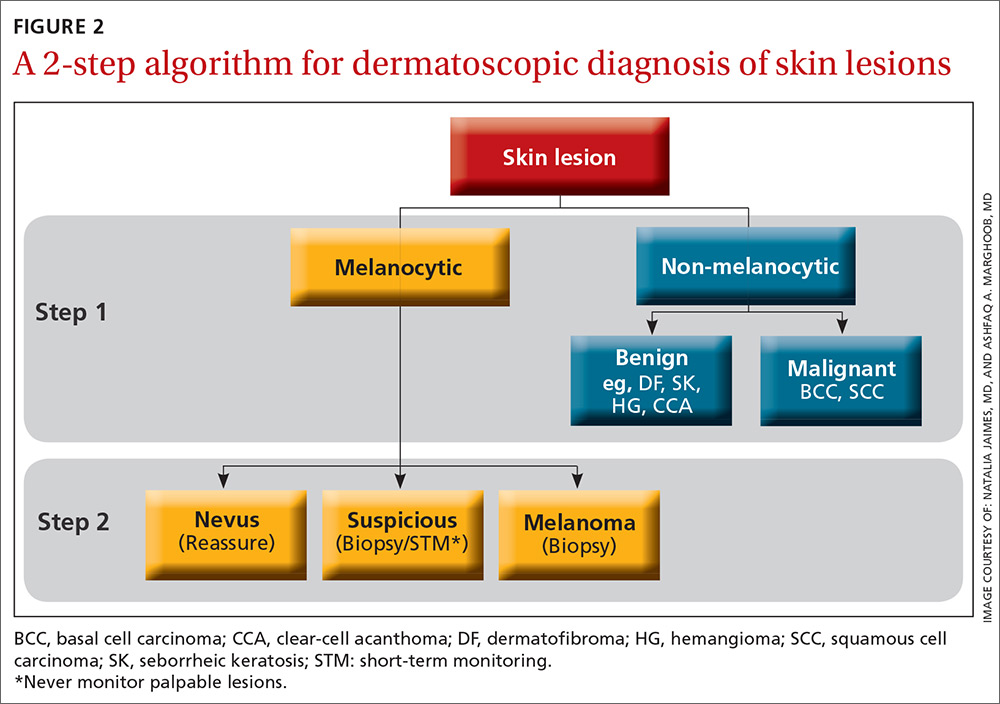

The second method, a 2-step algorithm, is a qualitative system that guides the observer through differentiating melanocytic from nonmelanocytic lesions in order to differentiate nevi from melanoma (FIGURE 2). At the same time, it serves as an aid to correctly diagnose non-melanocytic lesions. The 2-step algorithm forms the foundation for the dermoscopic evaluation of skin lesions in this article.

Not all expert dermoscopists employ structured analytical systems or methods to reach a diagnosis. Because of their vast experience, many rely purely on pattern recognition. But algorithms can facilitate non-experts in dermoscopy in the differentiation of nevi from melanoma or, simply, in differentiating the benign from the malignant.

Although each algorithm has its unique criteria, all of them require training and practice and familiarity with the terms used to describe morphologic structures. The International Dermoscopy Society recently published a consensus paper designating some terms as preferred over others.11

Continue to: Step 1...

Step 1: Melanocytic vs non-melanocytic

Step 1 of the 2-step algorithm requires the observer to determine whether the lesion is melanocytic (ie, originates from melanocytes and, therefore, could be a melanoma) or nonmelanocytic in origin.

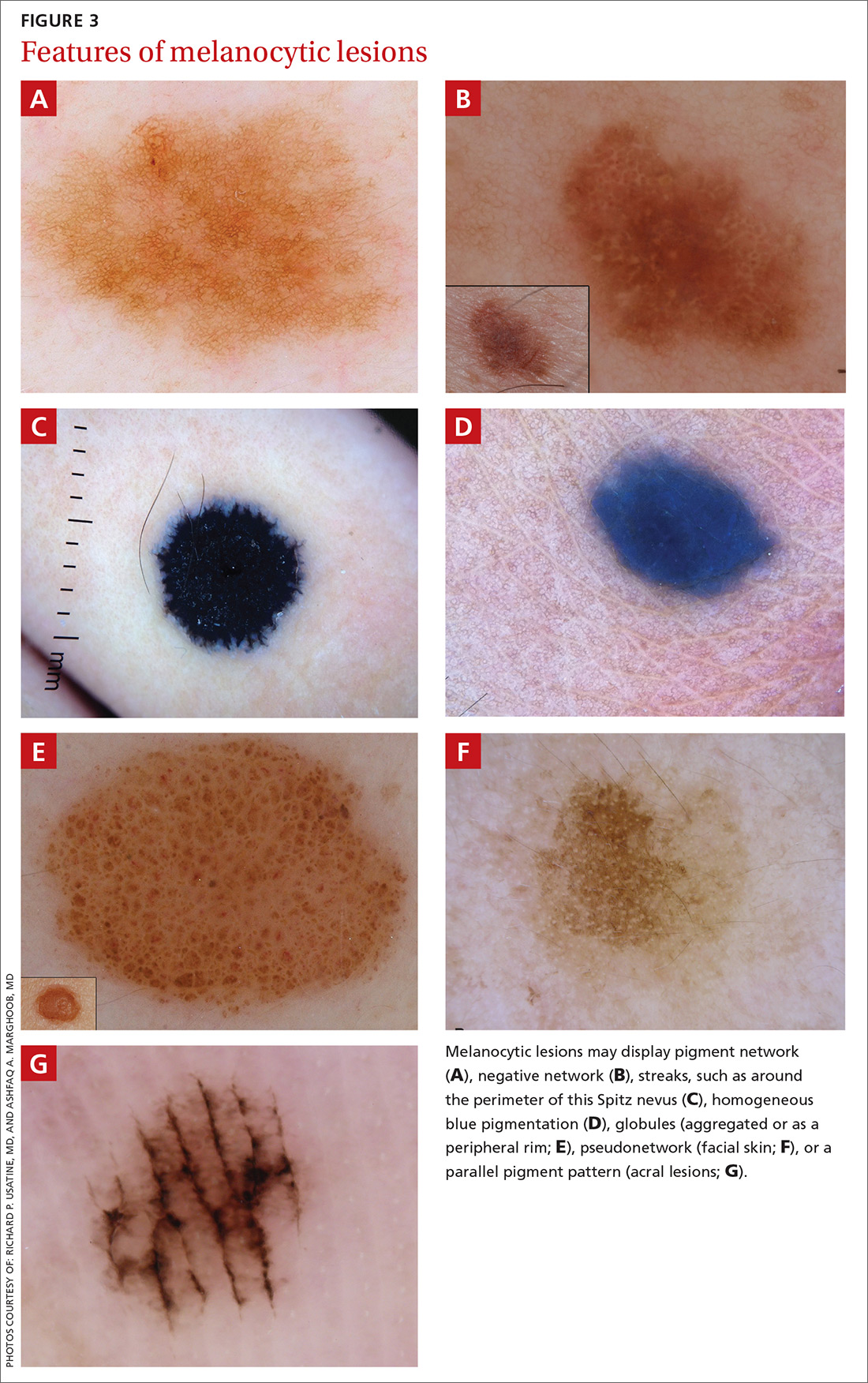

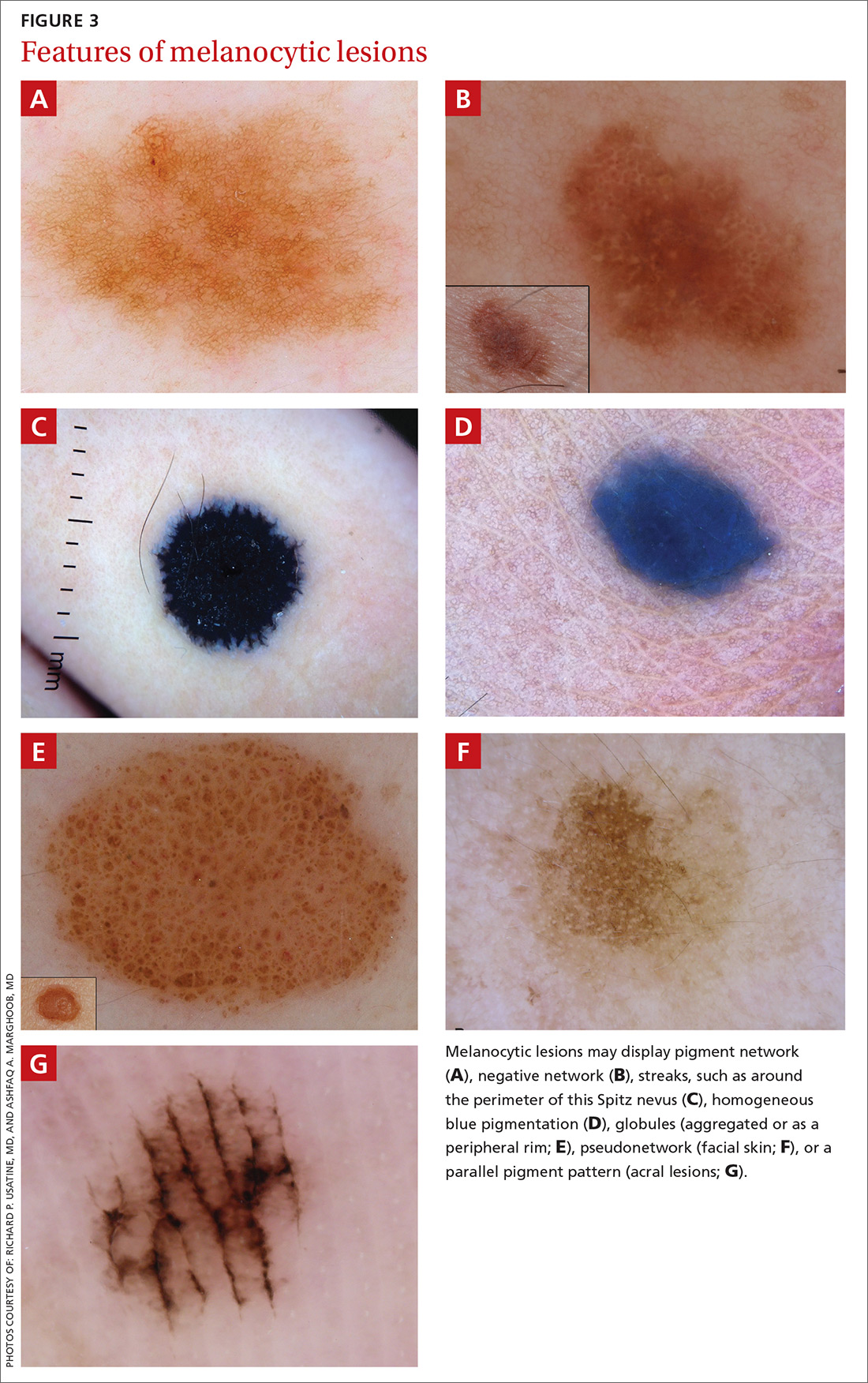

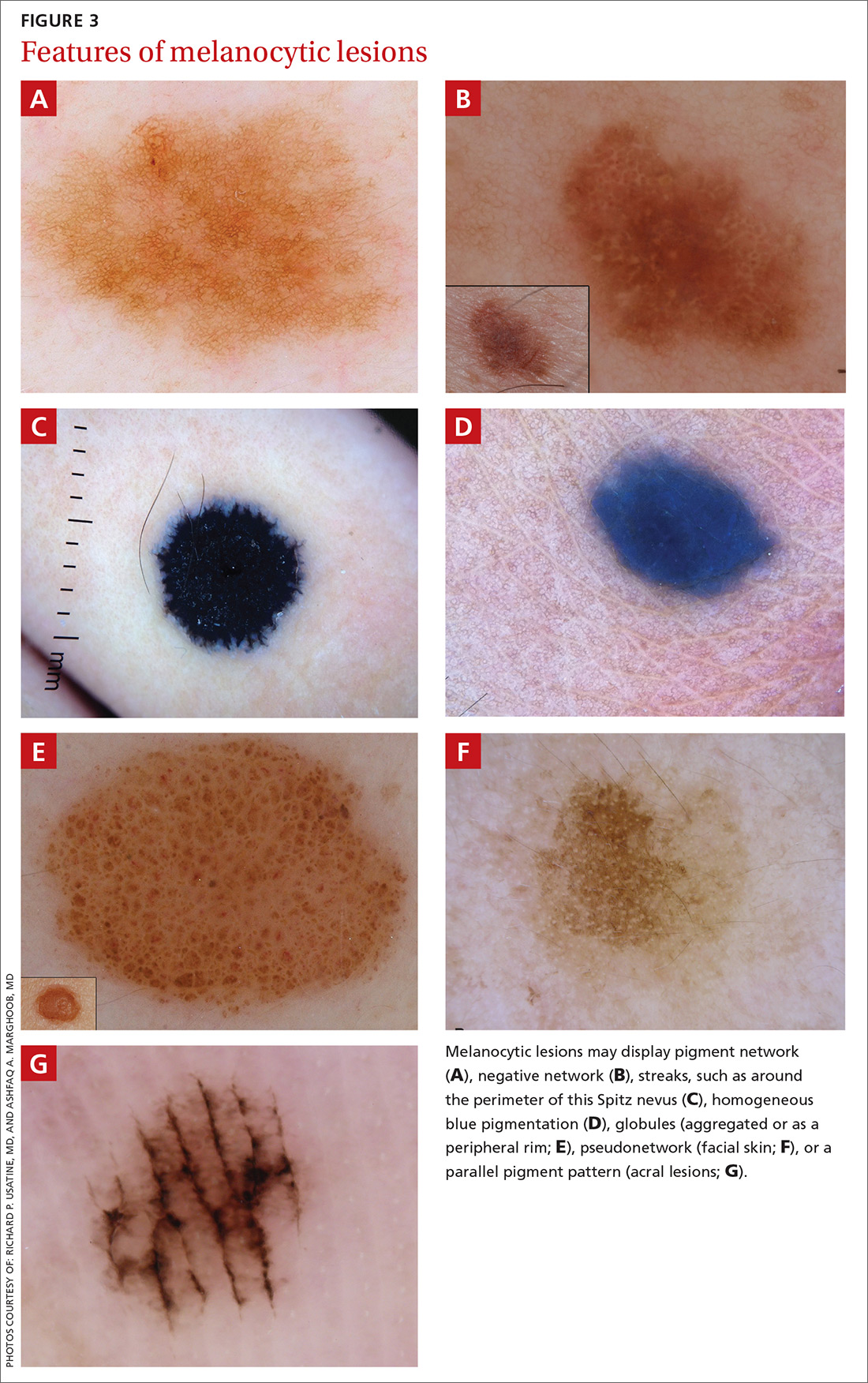

A melanocytic lesion usually will display at least 1 of the following structures:

- pigment network (FIGURE 3A) (This can include angulated lines.)

- negative network (FIGURE 3B) (hypopigmented lines connecting pigmented structures in a serpiginous fashion)

- streaks (FIGURE 3C)

- homogeneous blue pigmentation (FIGURE 3D)

- globules (aggregated or as a peripheral rim) (FIGURE 3E)

- pseudonetwork (facial skin) (FIGURE 3F)

- parallel pigment pattern (acral lesions) (FIGURE 3G).

Exceptions. Sometimes, nonmelanocytic lesions will present with pigment network. Dermatofibromas, for example, are one exception in which the pattern trumps the network. Two other exceptions are solar lentigo and supernumerary or accessory nipple.

If the lesion does not display any structure, it is considered structureless. In these cases, proceed to the second step to rule out a melanoma.

Doesn’t meet criteria for a melanocytic lesion?

If the lesion does not reveal any of the criteria for a melanocytic lesion, then look for structures seen in nonmelanocytic lesions: dermatofibromas; seborrheic keratosis; angiomas and angiokeratomas; sebaceous hyperplasia; clear-cell acanthomas; basal cell carcinomas (BCCs); and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs).

Continue to: Benign nonmelanocytic lesions

Benign nonmelanocytic lesions

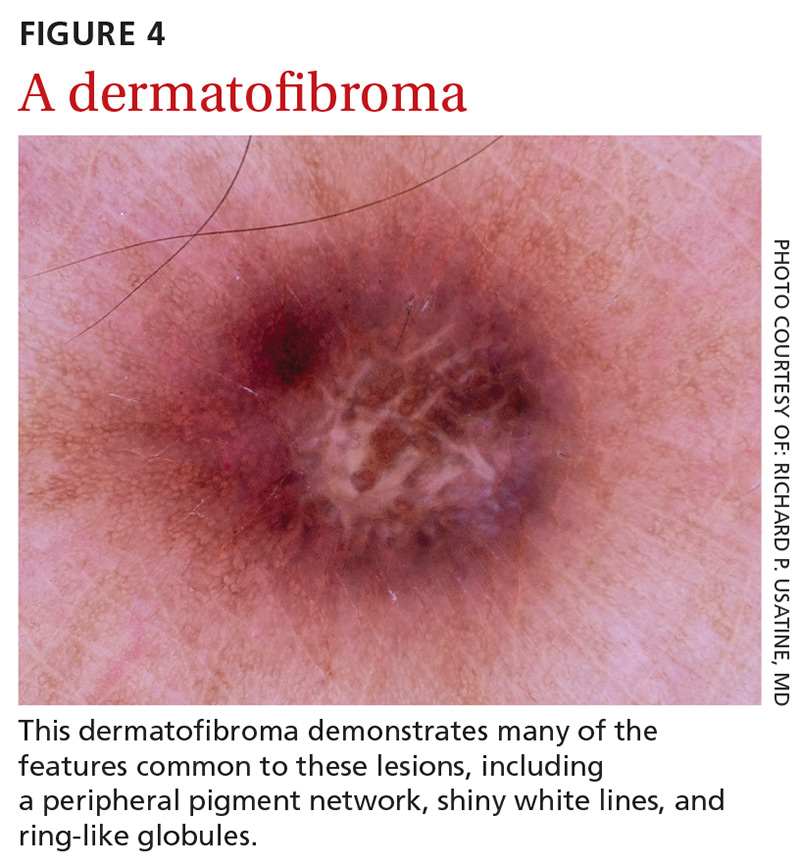

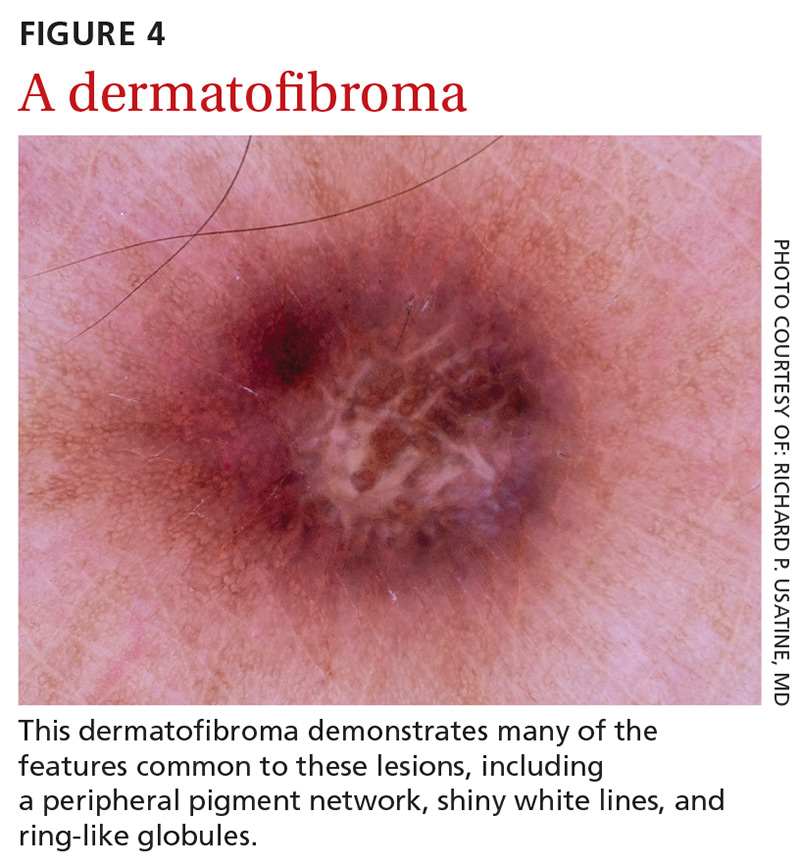

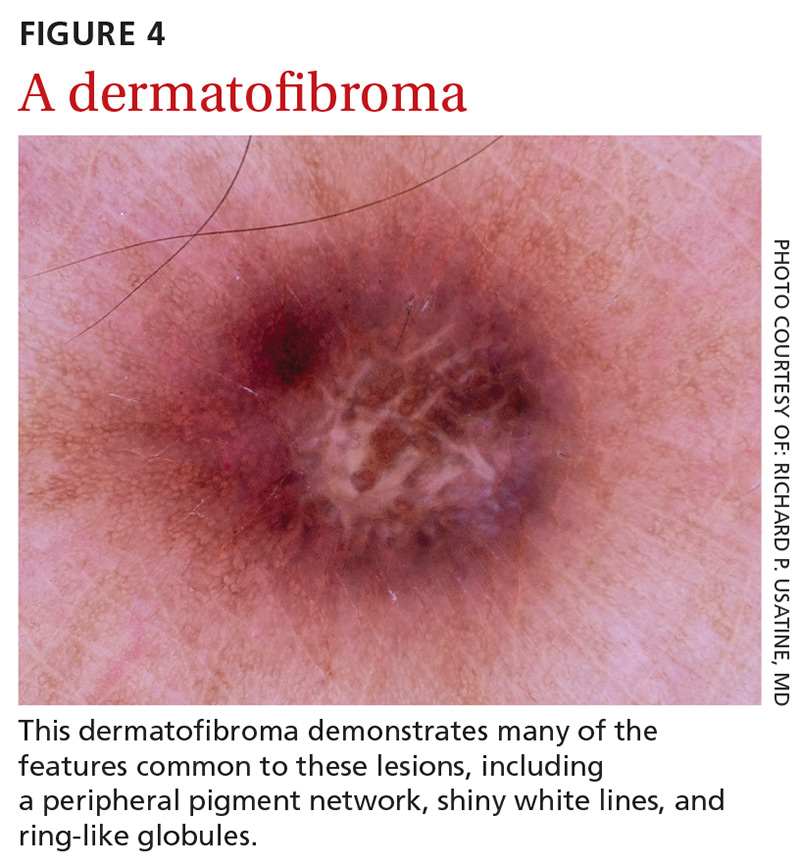

Dermatofibromas are benign symmetric lesions that feel firm and may dimple upon application of lateral pressure. They are fibrotic scar-like lesions that present with 1 or more of the following dermoscopic features (FIGURE 4):

- peripheral pigment network, due to increased melanin in keratinocytes

- homogeneous brown pigmented areas

- central scar-like area

- shiny white lines

- vascular structures (ie, dotted, polymorphous vessels), usually seen within the scar-like area

- ring-like globules, usually seen in the zone between the scar-like depigmentation and the peripheral network. They correspond to widened hyperpigmented rete ridges.

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign skin growth that often has a stuck-on appearance (FIGURE 5). Features often include:

- multiple (>2) milia-like cysts

- comedo-like openings

- a network-like structure that corresponds to gyri and sulci and which in some cases can create a cerebriform pattern

- fingerprint-like structures

- moth-eaten borders

- jelly sign. This consists of semicircular u-shaped structures that have a smudged appearance and are aligned in the same direction. The appearance resembles jelly as it is spread on a piece of bread.

- hairpin (looped or twisted-looped) vessels surrounded by a white halo.

Other clues include a sharp demarcation and a negative wobble sign (which we’ll describe in a moment). The presence or absence of a wobble sign is determined by using a dermatoscope that touches the skin. Mild vertical pressure is applied to the lesion while moving the scope back and forth horizontally. If the lesion slides across the skin surface, the diagnosis of an epidermal keratinocytic tumor (ie, SK) is favored. If, on the other hand, the lesion wobbles (rolls back and forth), then the diagnosis of a neoplasm with a dermal component (ie, intradermal or compound nevus) is more likely.

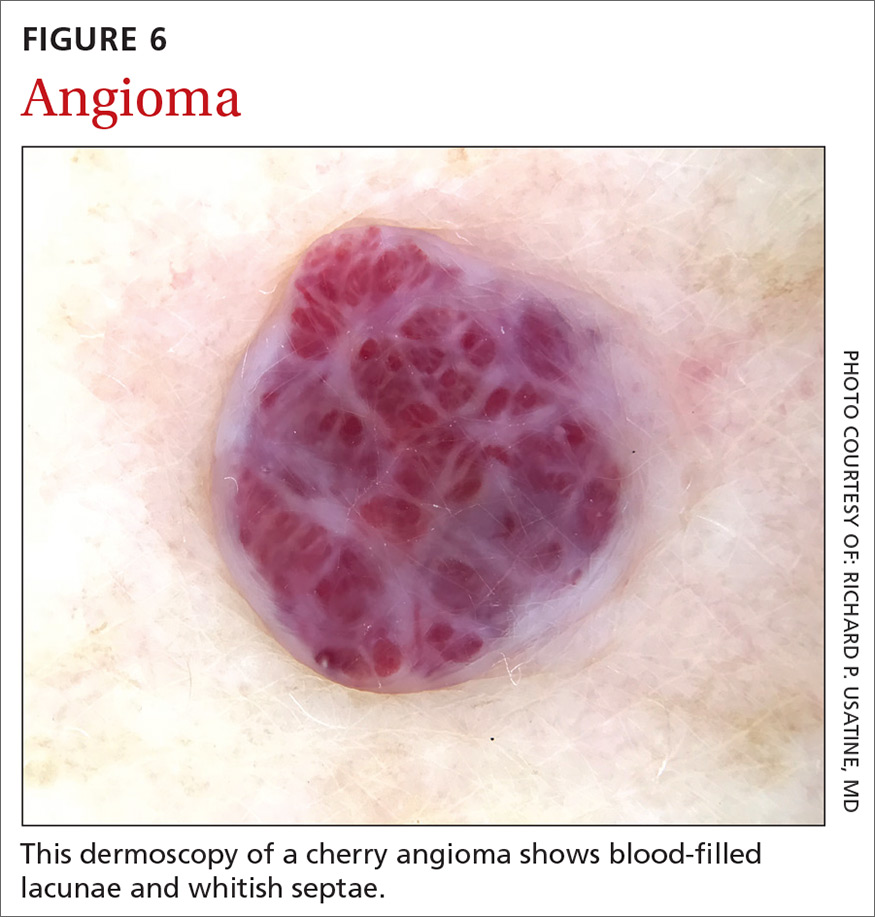

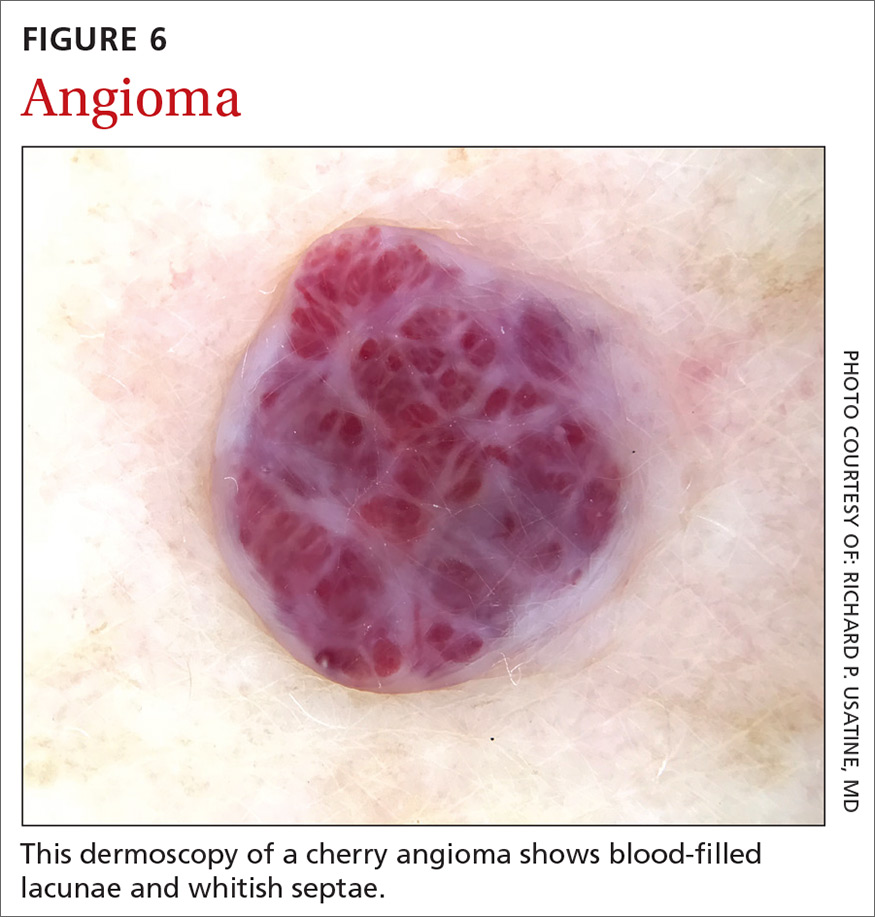

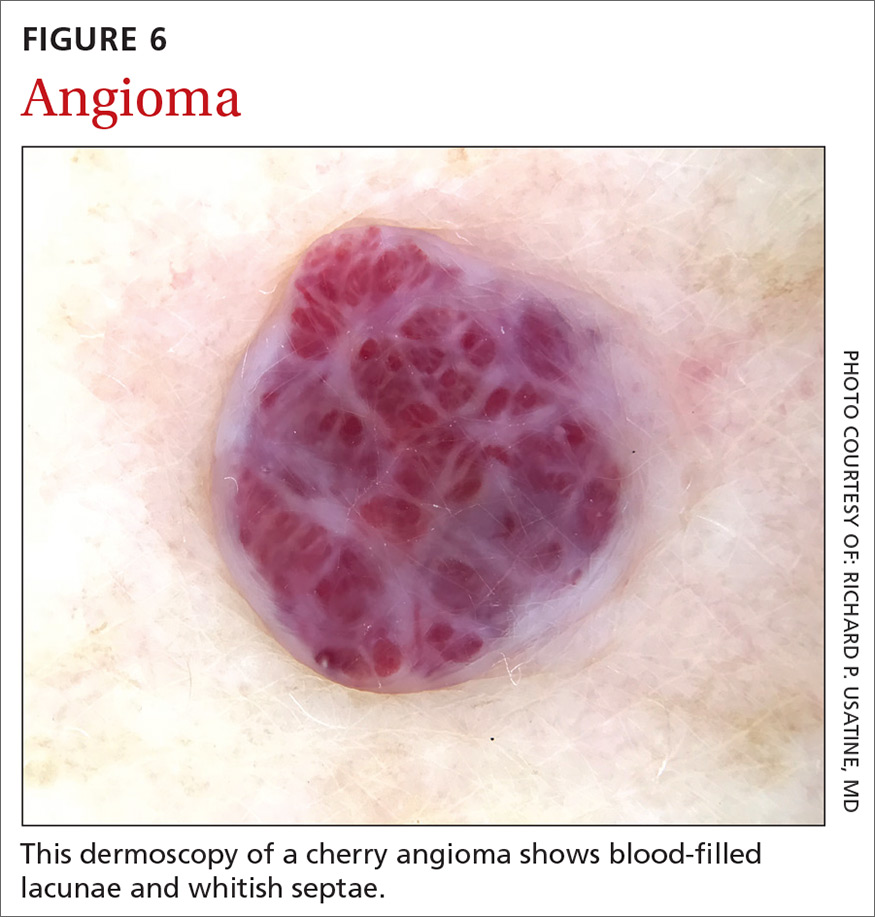

Angiomas and angiokeratomas. Angiomas demonstrate lacunae that are often separated by septae (FIGURE 6). Lacunae can vary in size and color. They can be red, red-white, red-blue, maroon, blue, blue-black, or even black (when thrombosis is present).

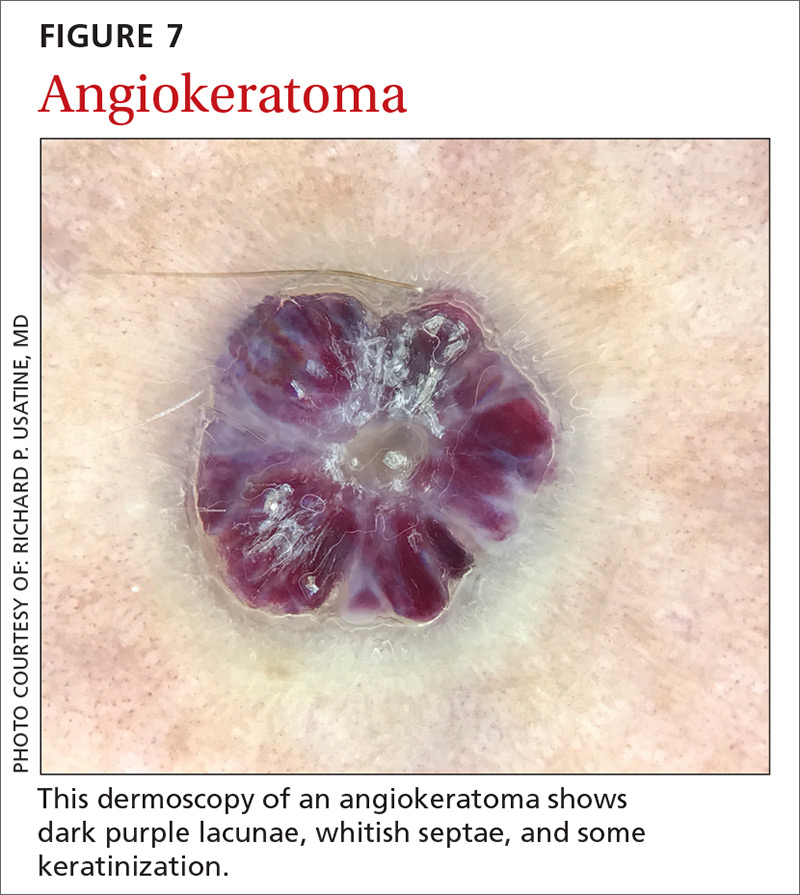

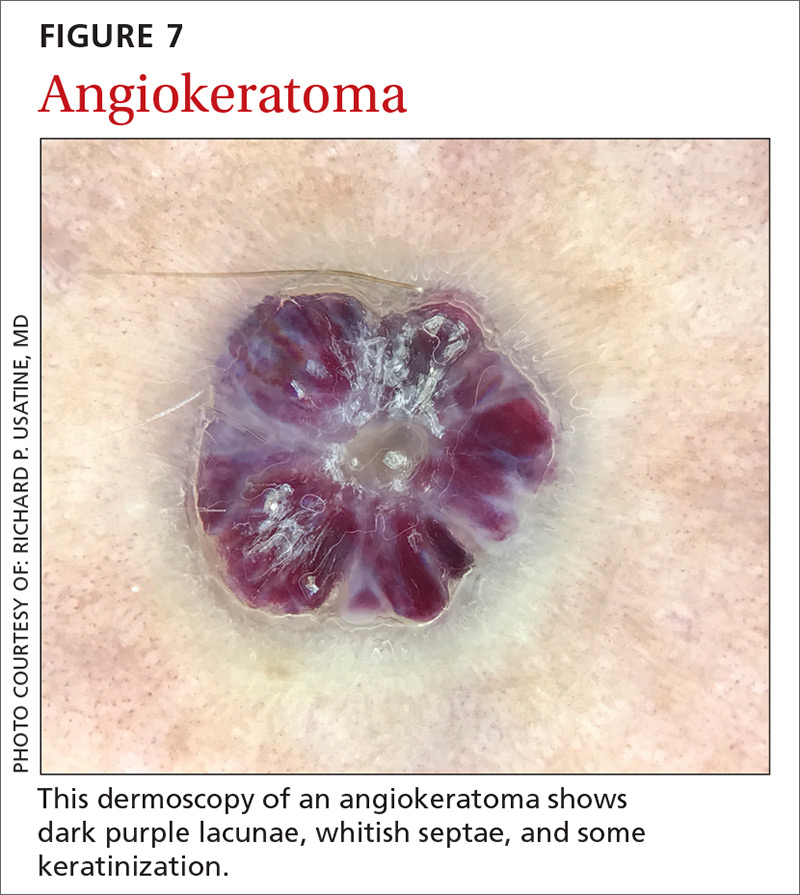

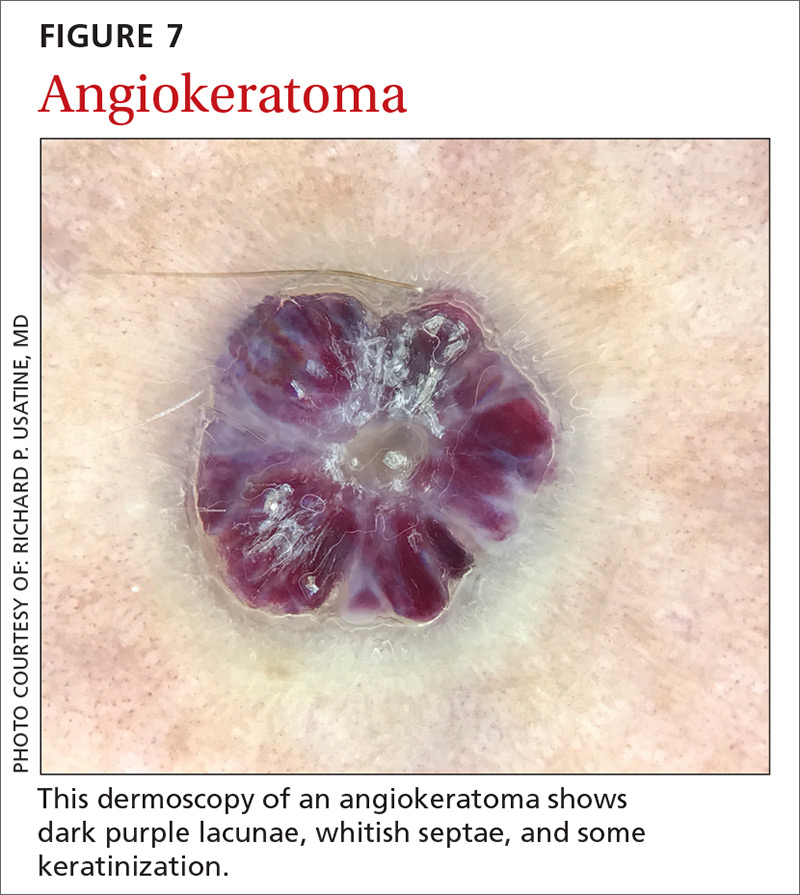

Angiokeratomas (FIGURE 7) can reveal lacunae of varying colors including black, red, purple, and maroon. In addition, a blue-whitish veil, erythema, and hemorrhagic crusts can be present.

Continue to: Sebaceous hyperplasia...

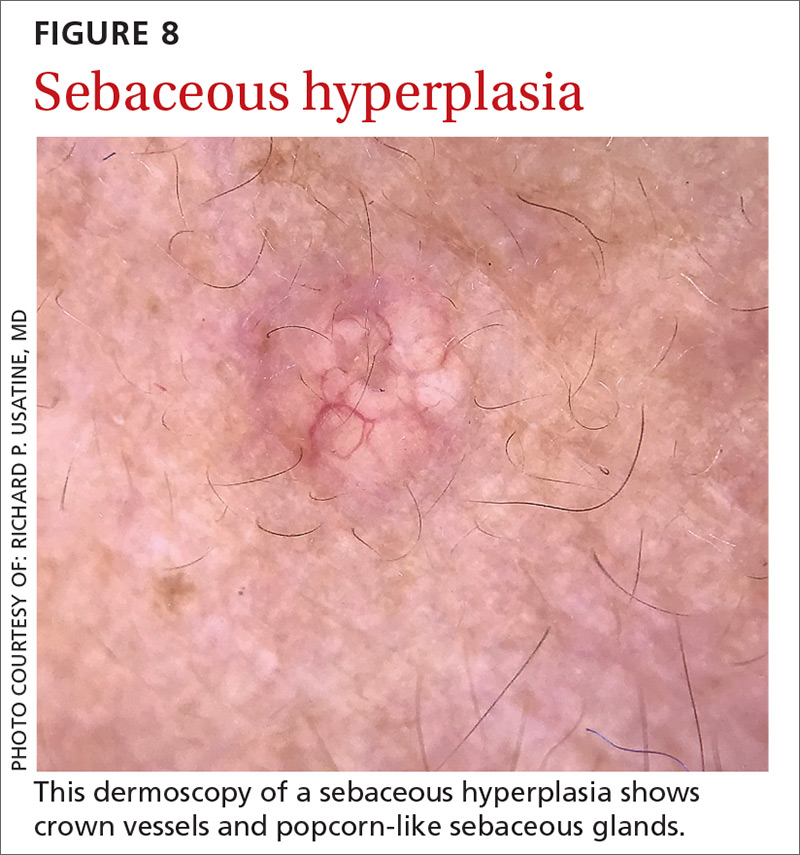

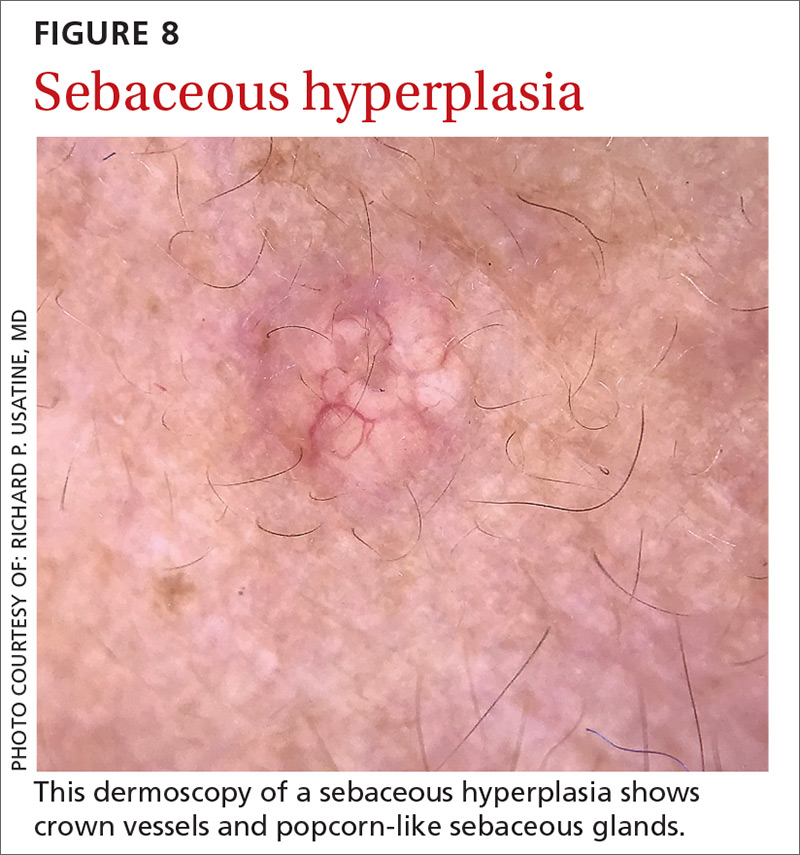

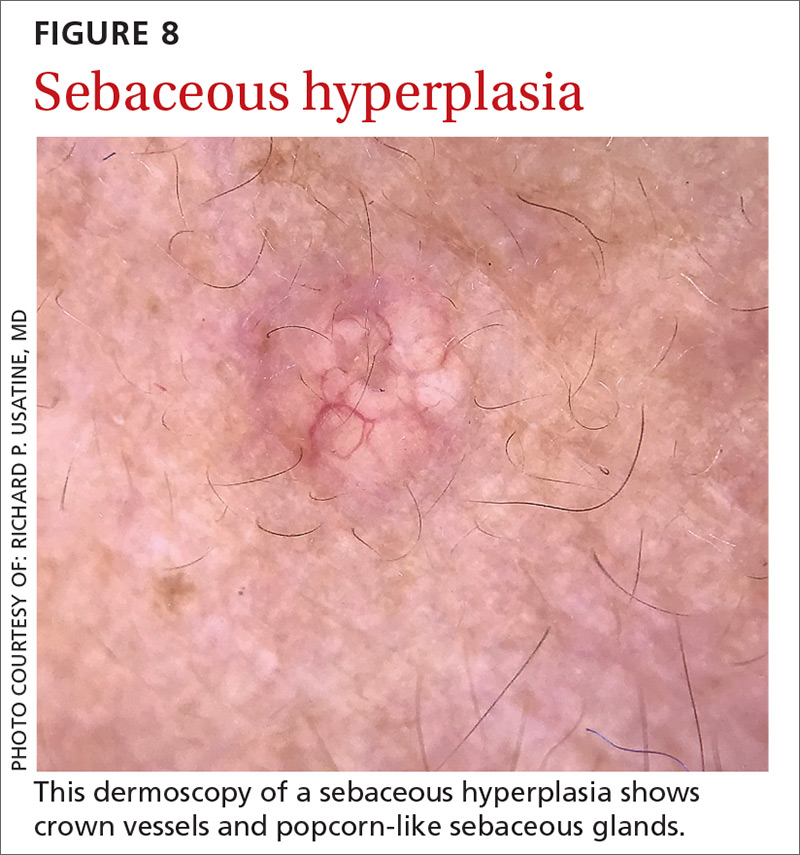

Sebaceous hyperplasia is the overgrowth of sebaceous glands. It can mimic BCC on the face. Sebaceous hyperplasia presents with multiple vessels in a crown-like arrangement that do not cross the center of the lesion. The sebaceous glands resemble popcorn (FIGURE 8).

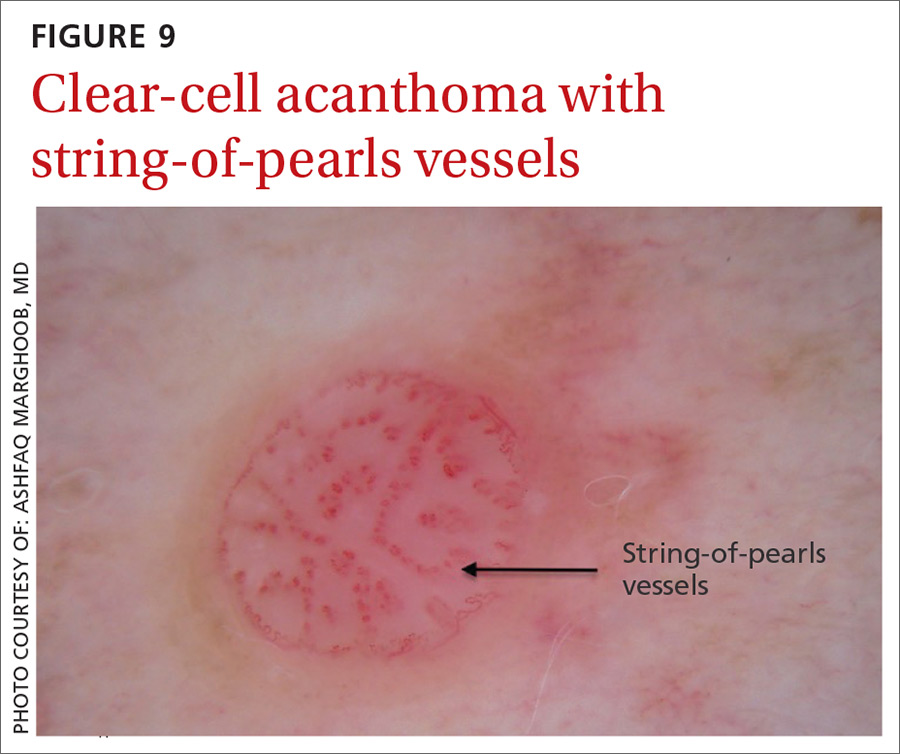

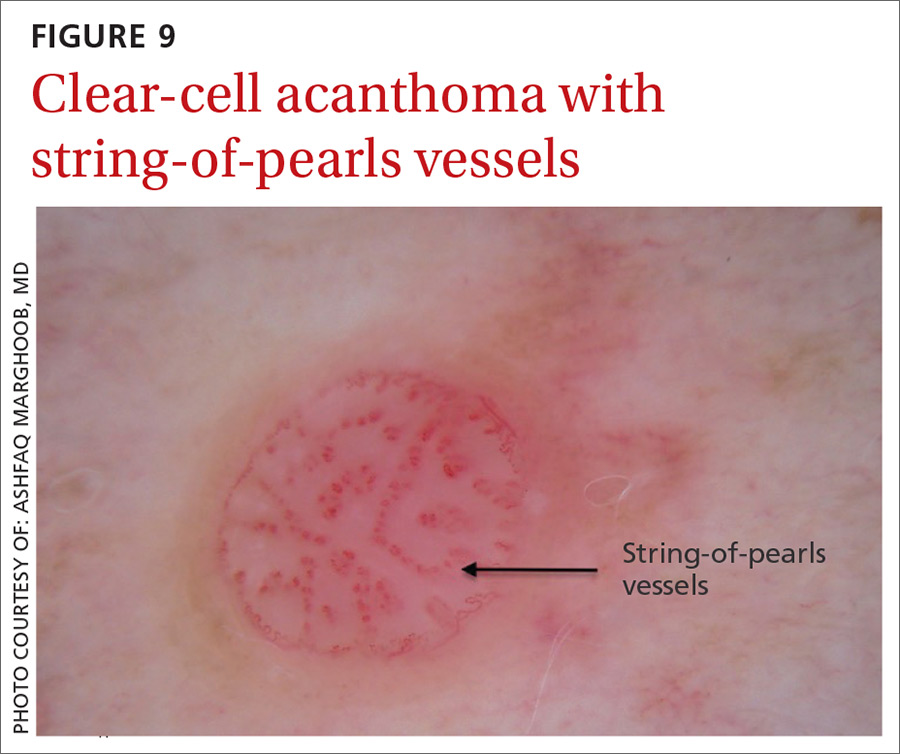

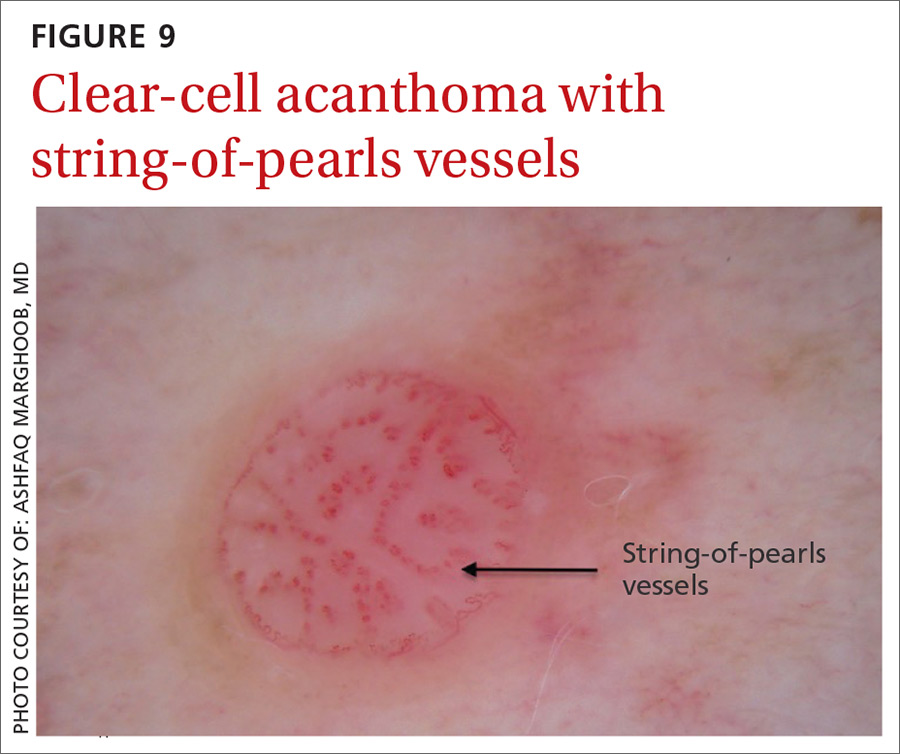

Clear-cell acanthoma is a benign erythematous epidermal tumor usually found on the leg with a string-of-pearls pattern. This pattern is vascular so the pearls are red in color (FIGURE 9).

Malignant nonmelanocytic lesions

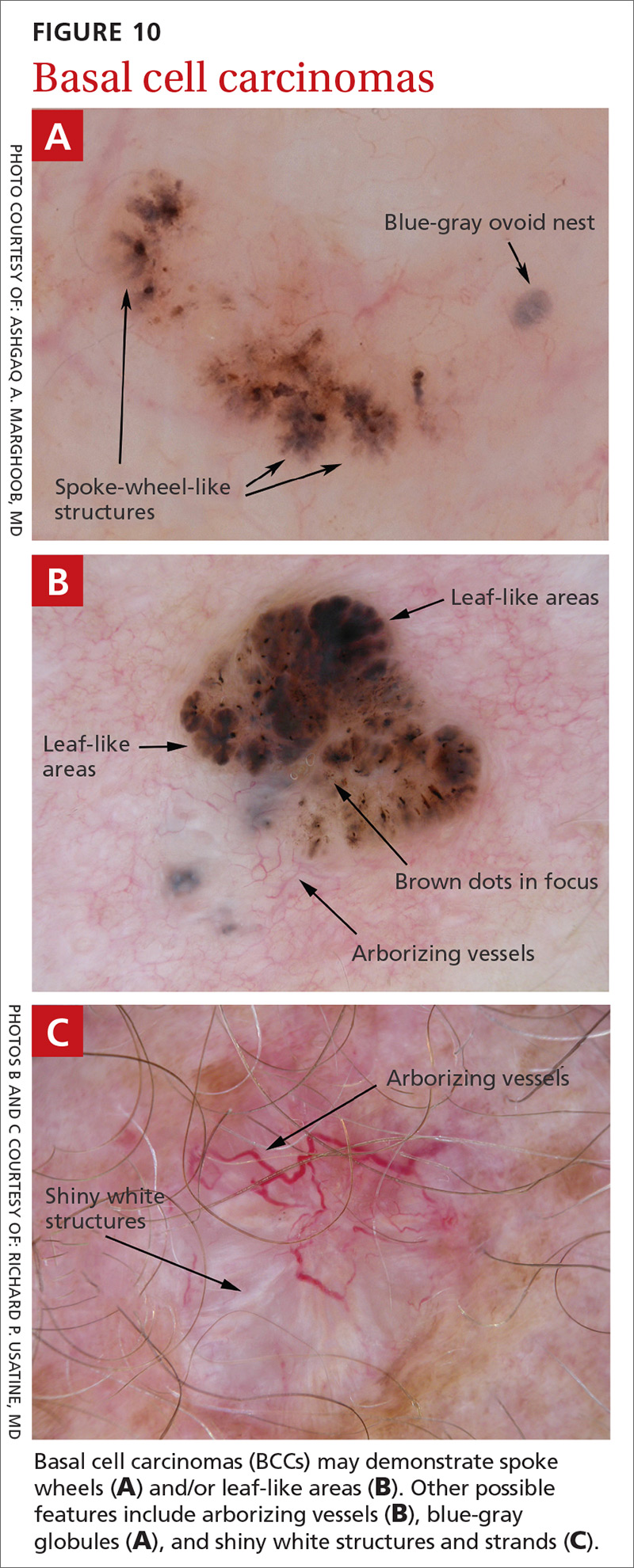

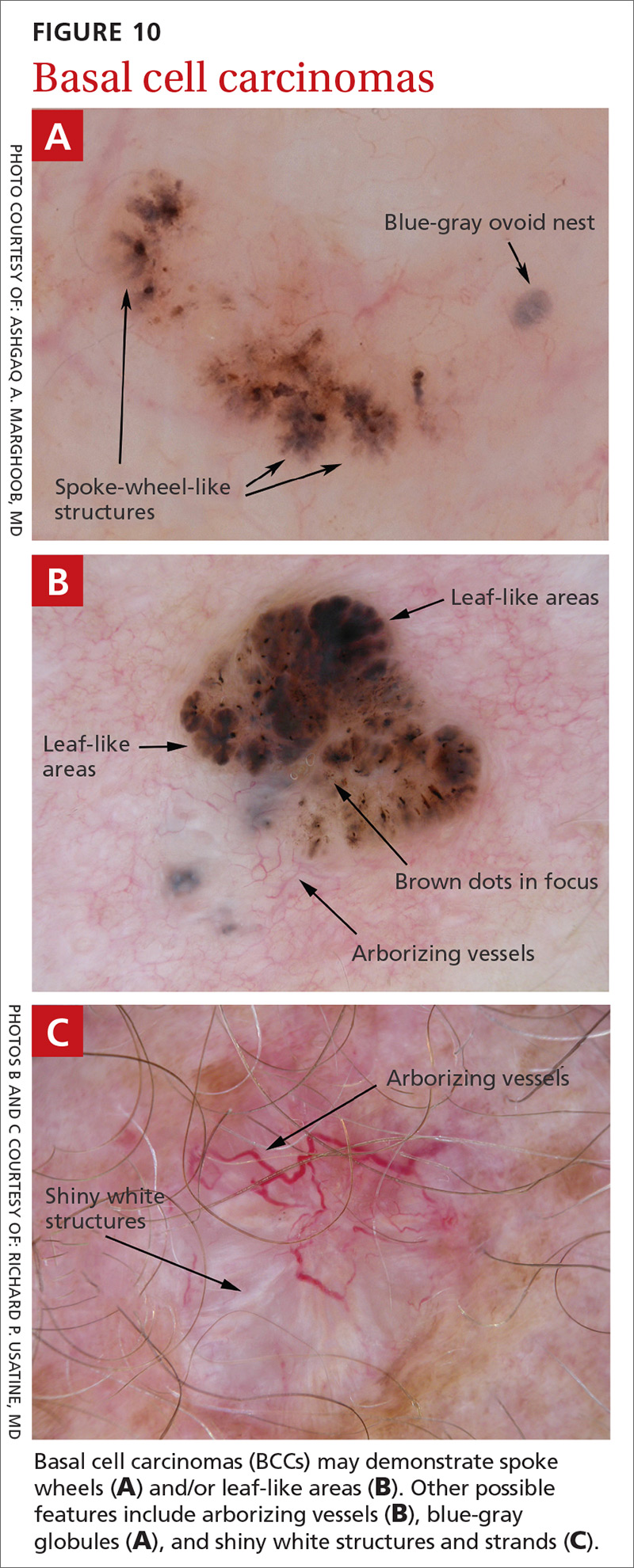

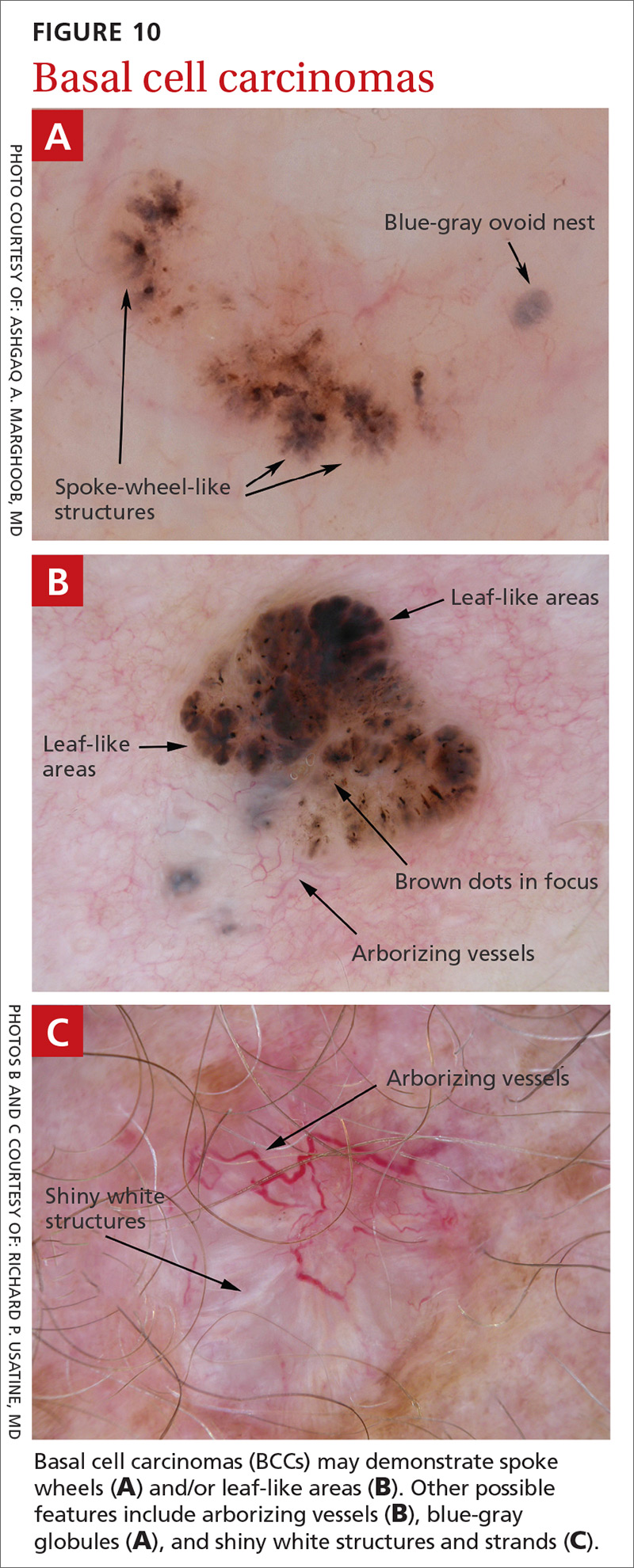

BCC is the most common type of skin cancer. Features often include:

- spoke-wheel-like structures or concentric structures (FIGURE 10A)

- leaf-like areas (FIGURE 10B)

- arborizing vessels (FIGURE 10b and 10C)large blue-gray ovoid nest (FIGURE 10A)

- multiple blue-gray non-aggregated globules

- ulceration or multiple small erosions

- shiny white structures and strands (FIGURE 10C).

Additional dermoscopic clues include short, fine, superficial telangiectasias and multiple in-focus dots in a buck-shot scatter distribution.

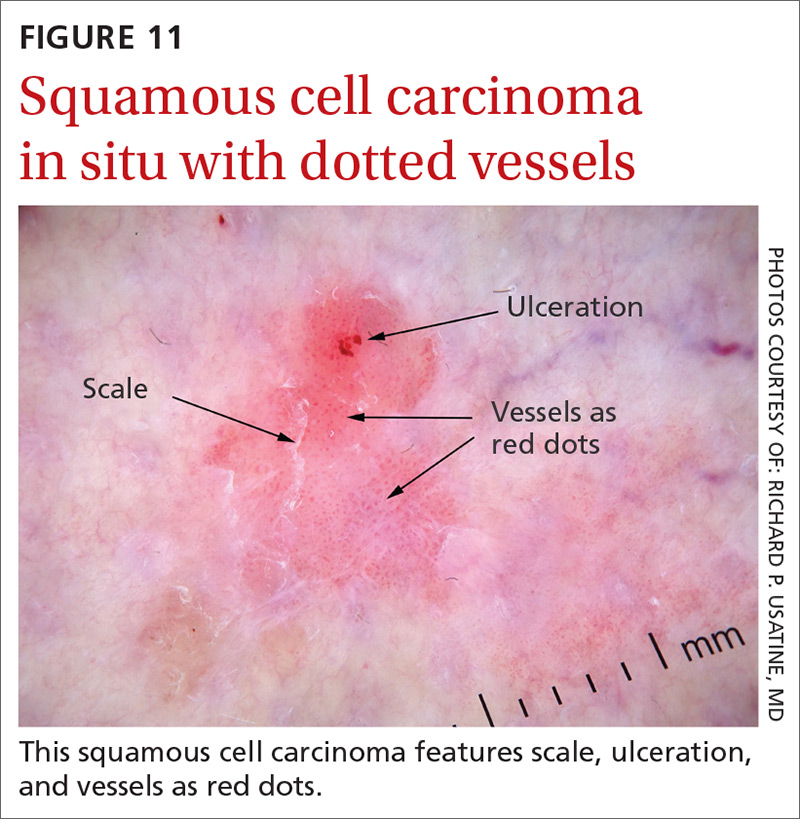

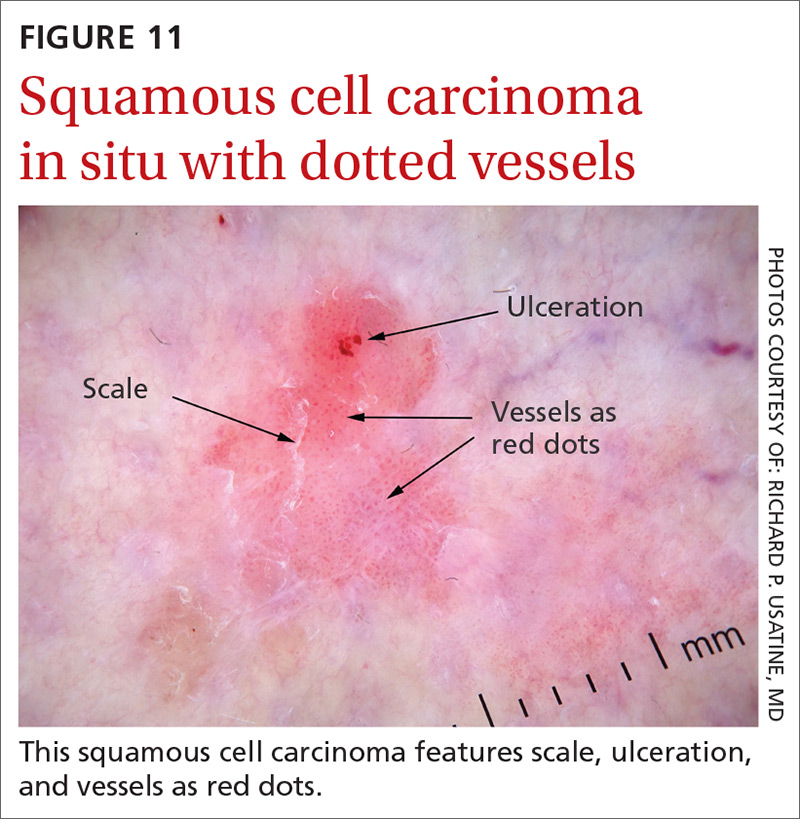

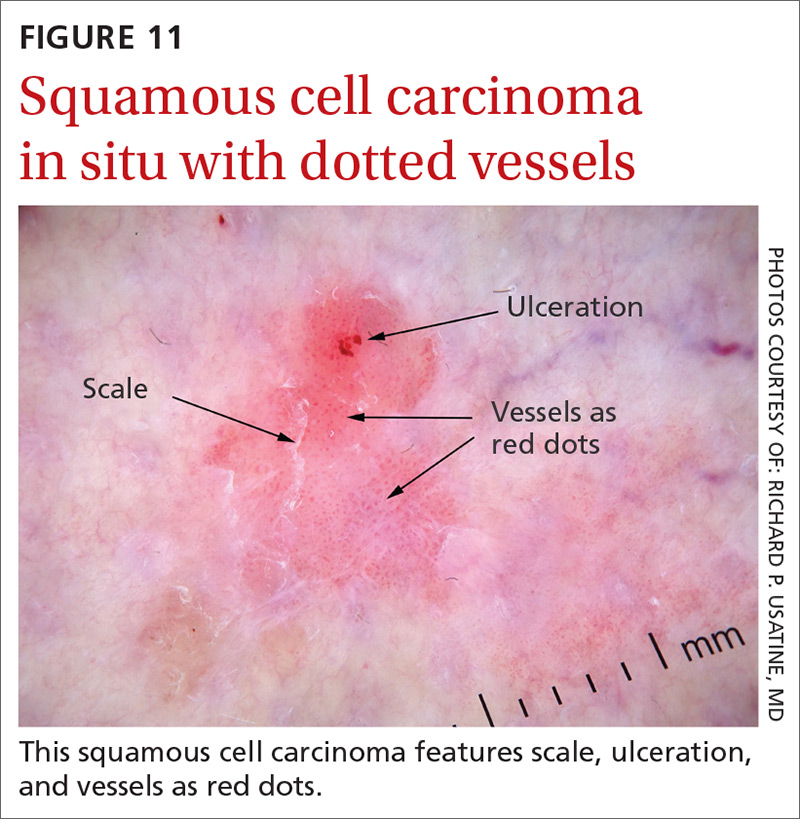

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of the skin are keratinizing malignant tumors. Each SCC generally has some of the following features (FIGURE 11):

- dotted and/or glomerular vessels, commonly distributed focally at the periphery. They can also be diffuse or aligned linearly within the lesion.

- scale (yellow or white)

- rosettes (seen with polarized light)

- white circles or keratin pearls

- brown circles

- ulcerations

- brown dots or globules arranged in a linear configuration.

Continue to: Step 2...

Step 2: It’s melanocytic, but is it a nevus or a melanoma?

If, by following Step 1 of the algorithm, the lesion is determined to be of melanocytic origin, then one proceeds to Step 2 to decide whether the growth is a nevus, a suspicious lesion, or a melanoma. For this purpose, several additional algorithms are available.12-17

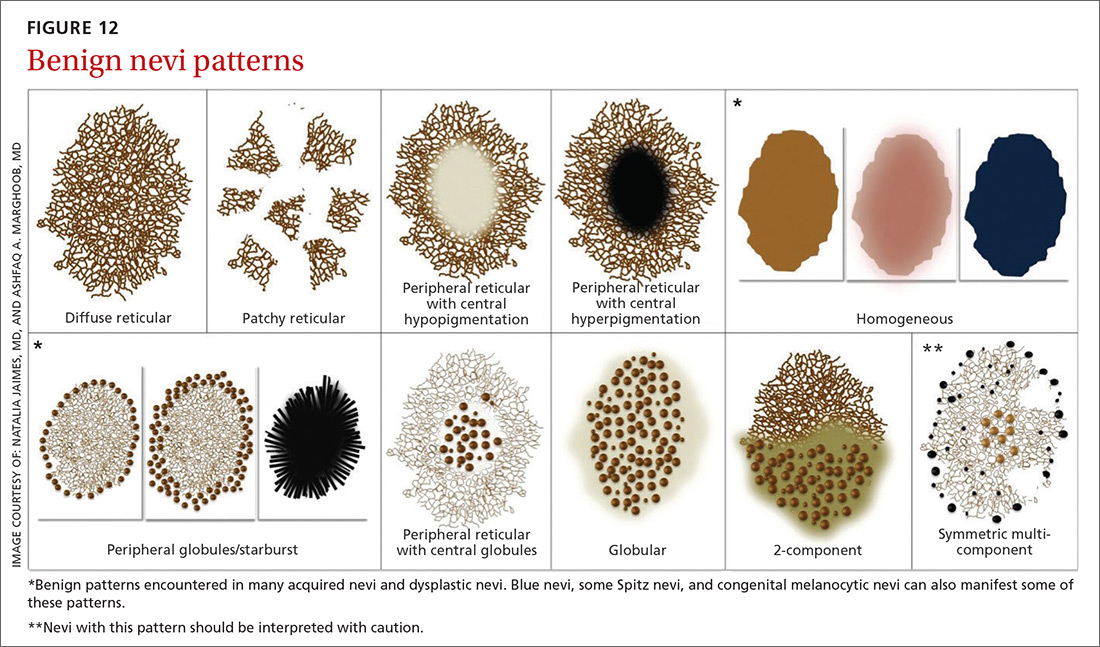

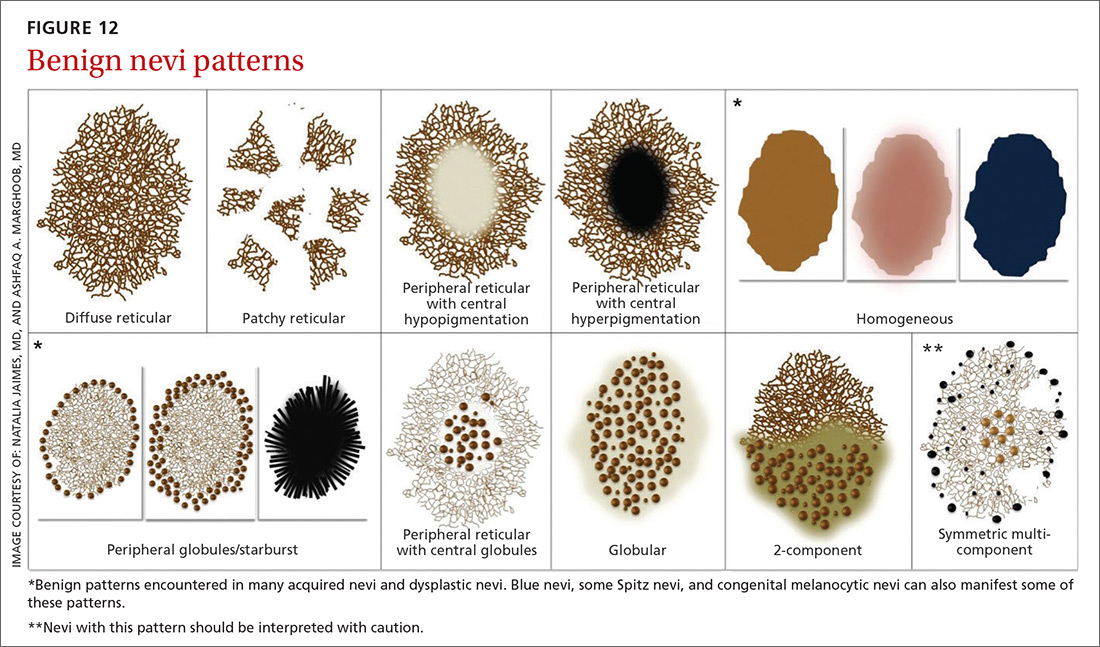

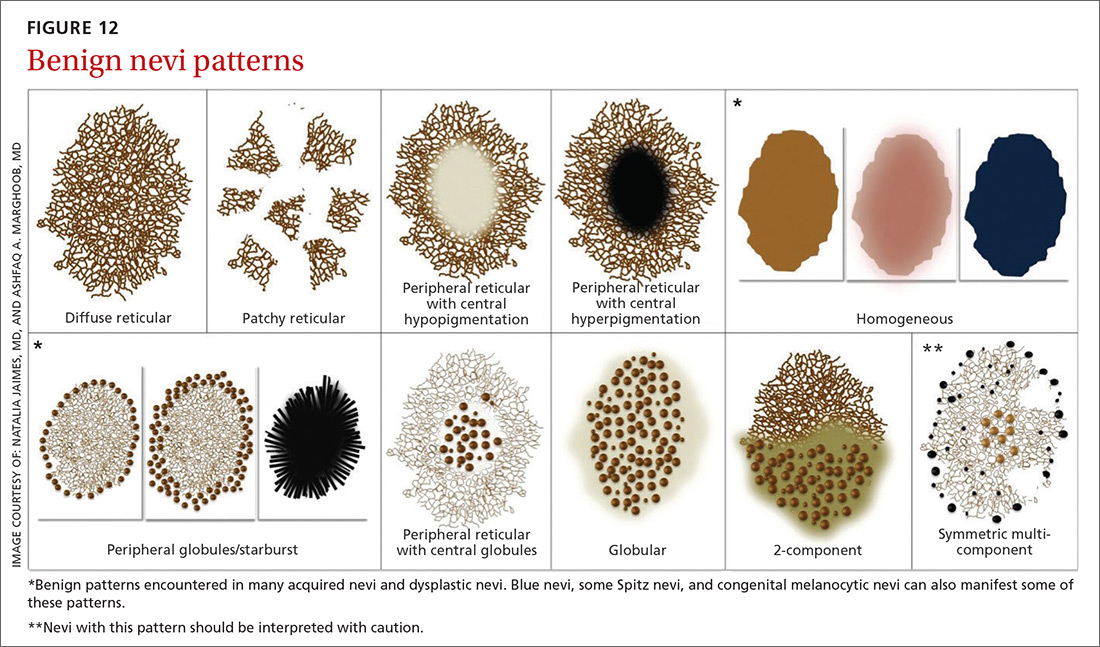

Benign nevi tend to manifest with 1 of the following 10 patterns: (FIGURE 12)

- diffuse reticular

- patchy reticular

- peripheral reticular with central hypopigmentation

- peripheral reticular with central hyperpigmentation

- homogeneous

- peripheral globules/starburst. It has been suggested that lesions that show starburst morphology on dermoscopy require complete excision and follow-up since 13% of Spitzoid-looking symmetric lesions in patients older than 12 years were found to be melanoma in one study.18

- peripheral reticular with central globules

- globular

- 2-component

- symmetric multicomponent (this pattern should be interpreted with caution, and a biopsy is probably warranted for dermoscopic novices).

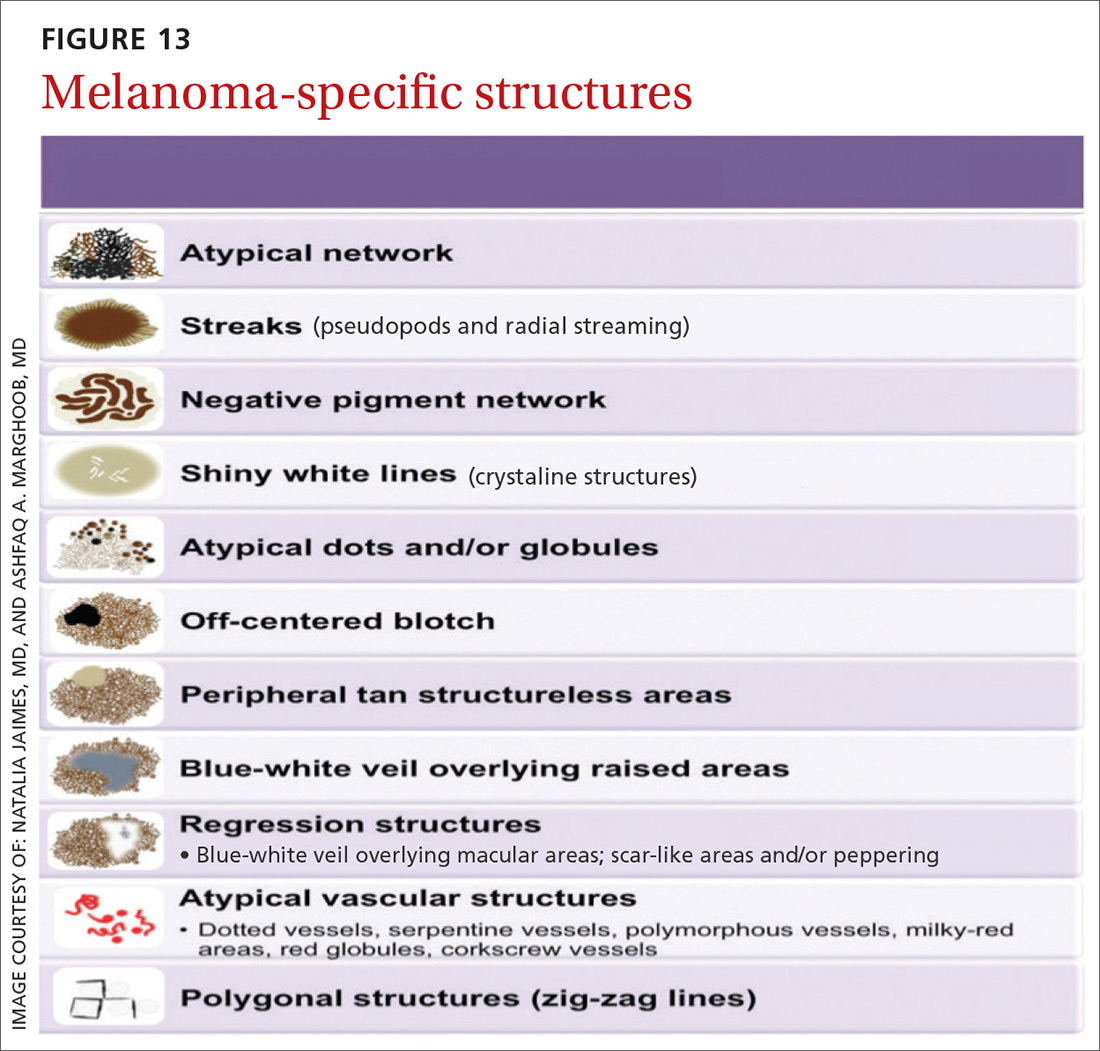

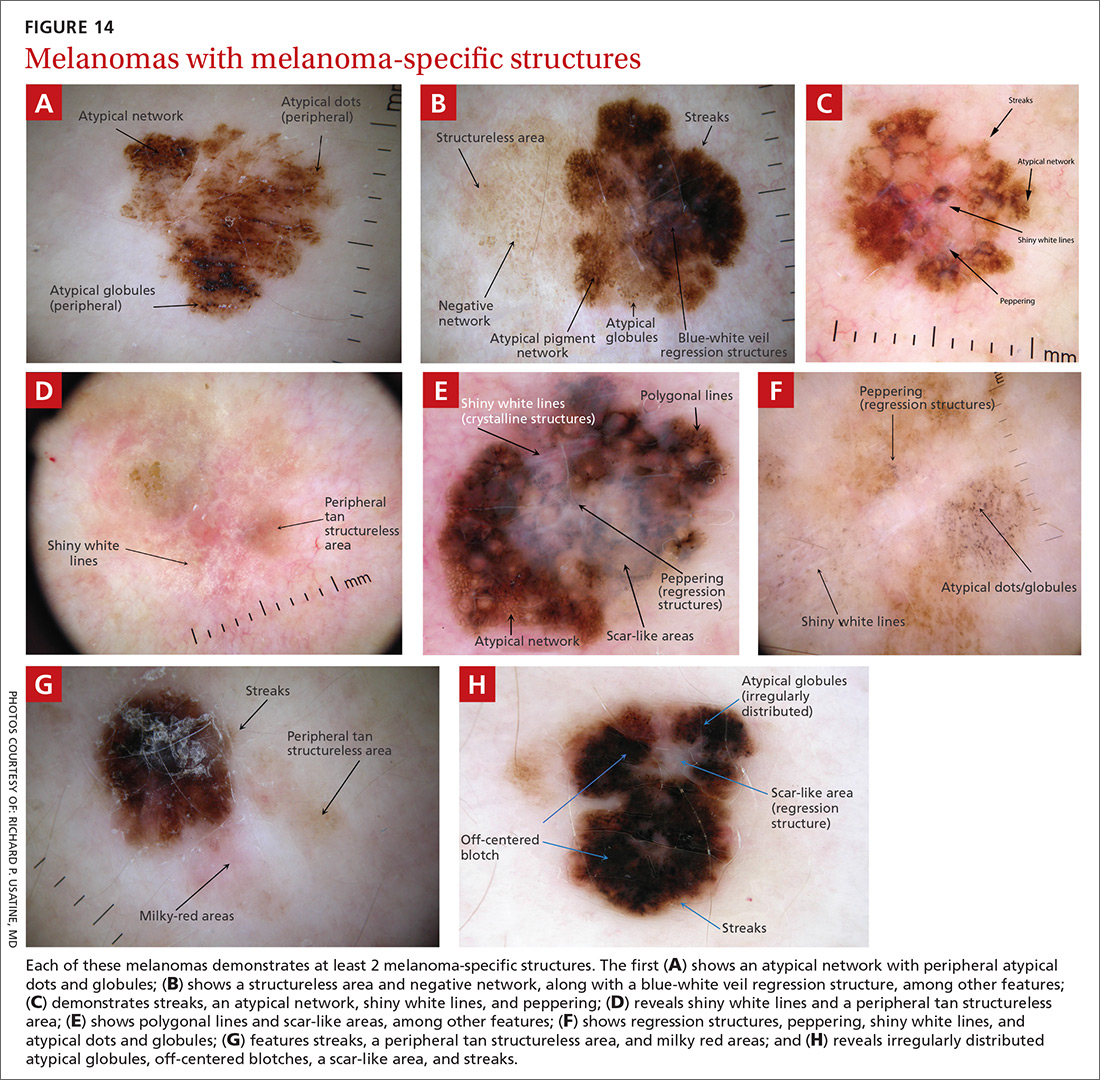

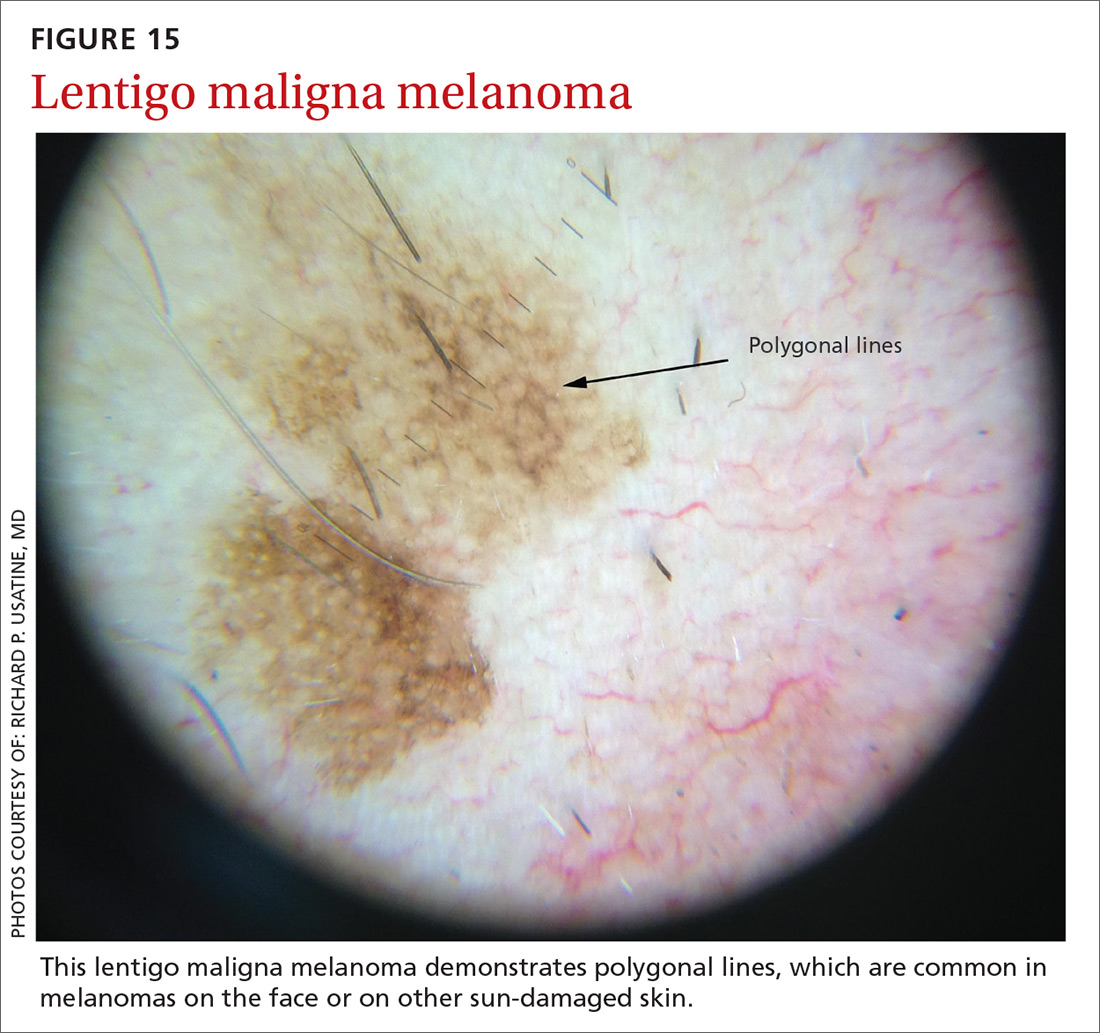

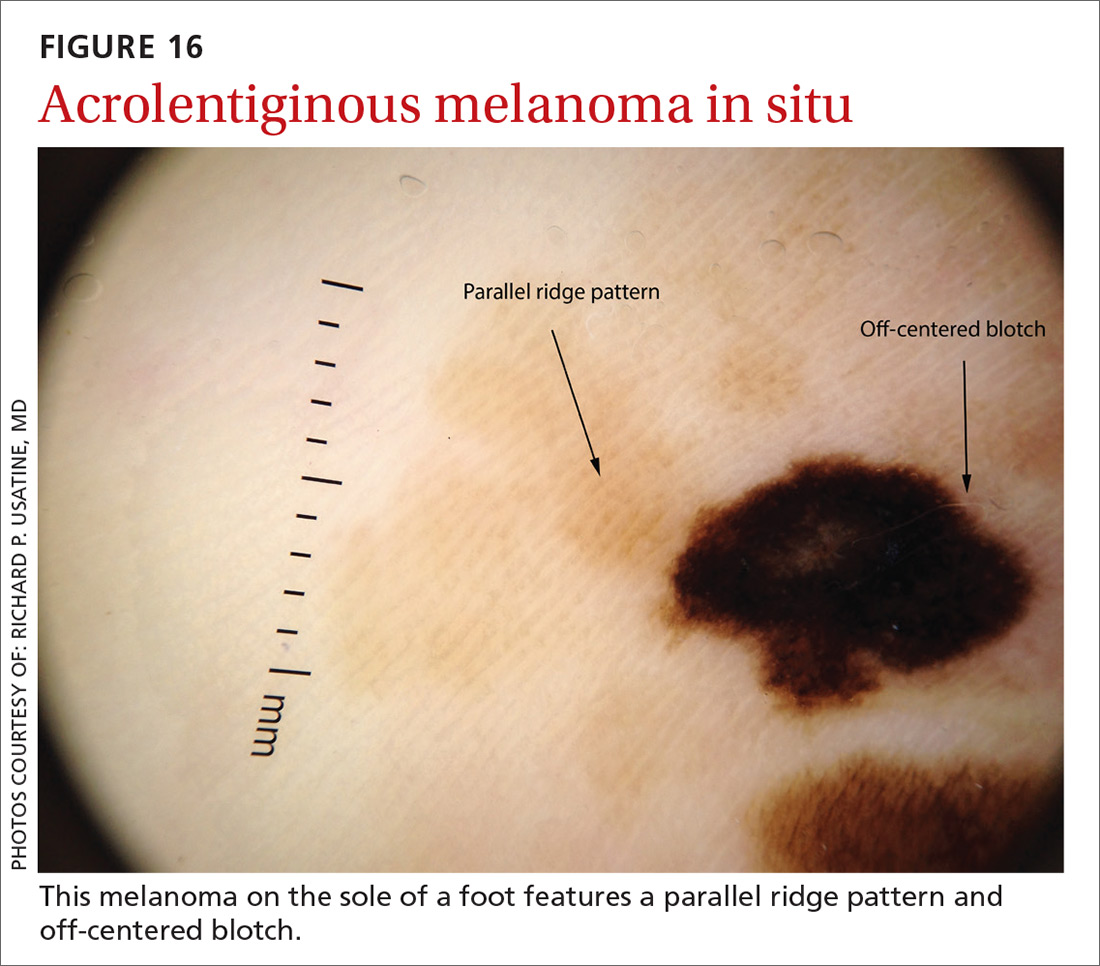

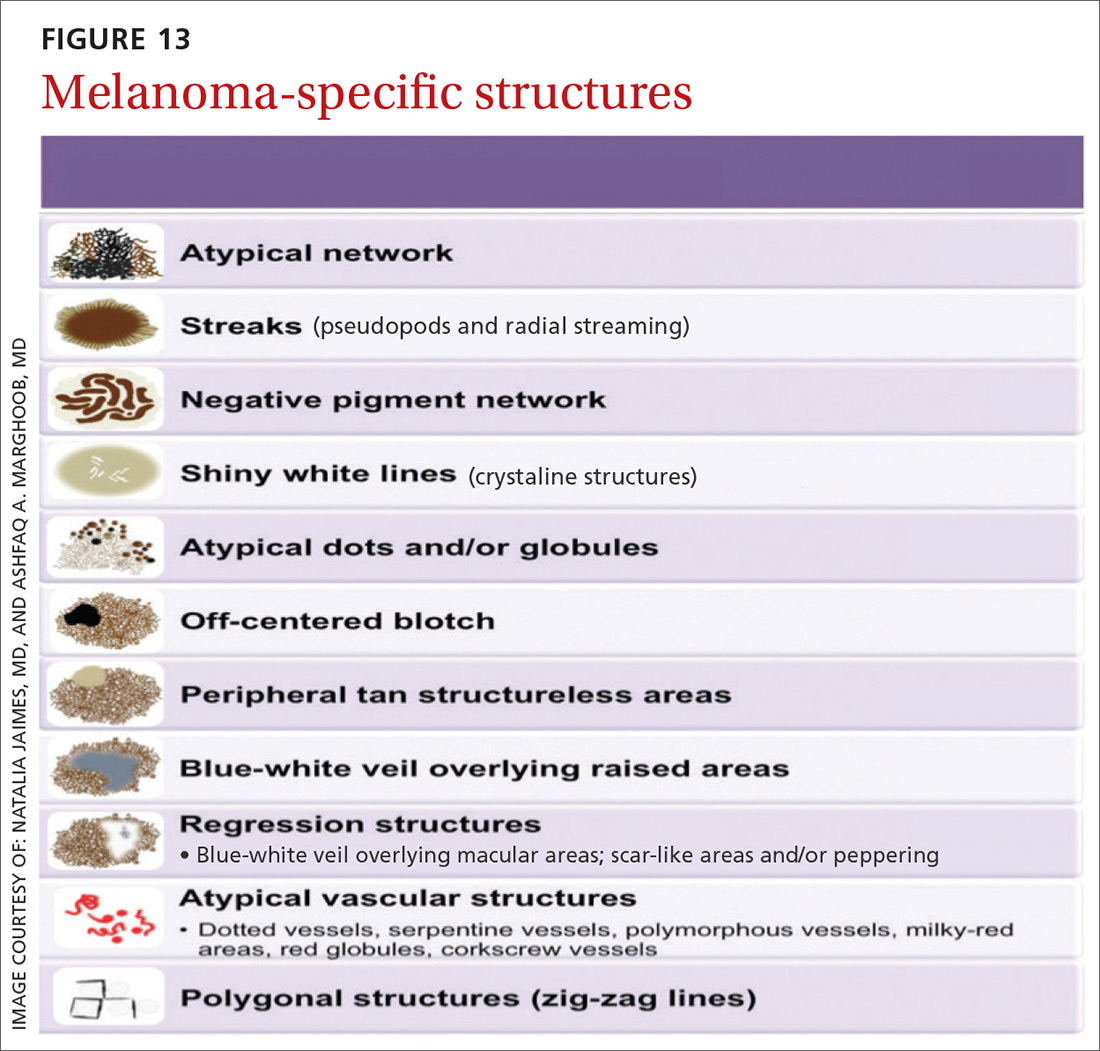

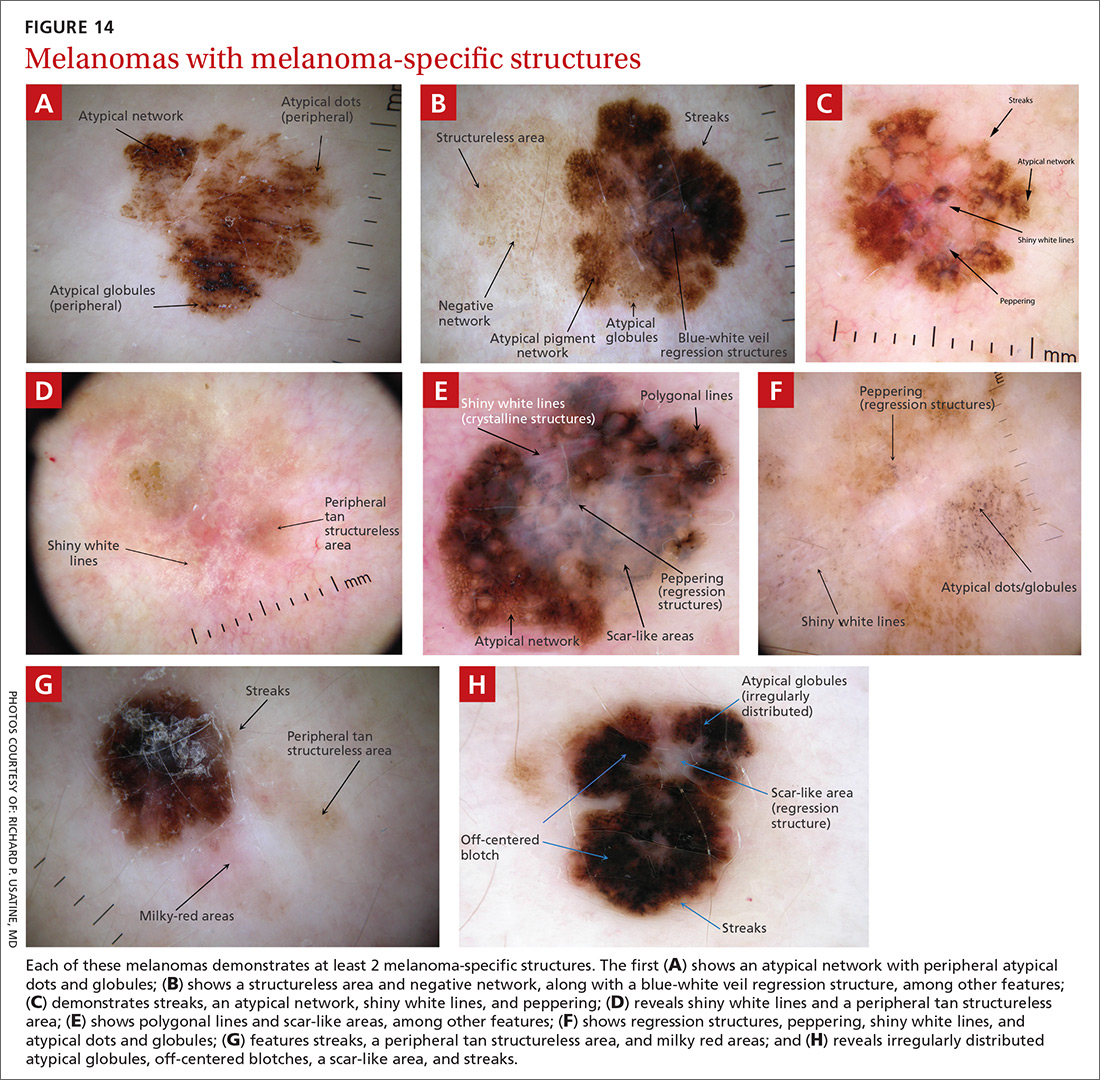

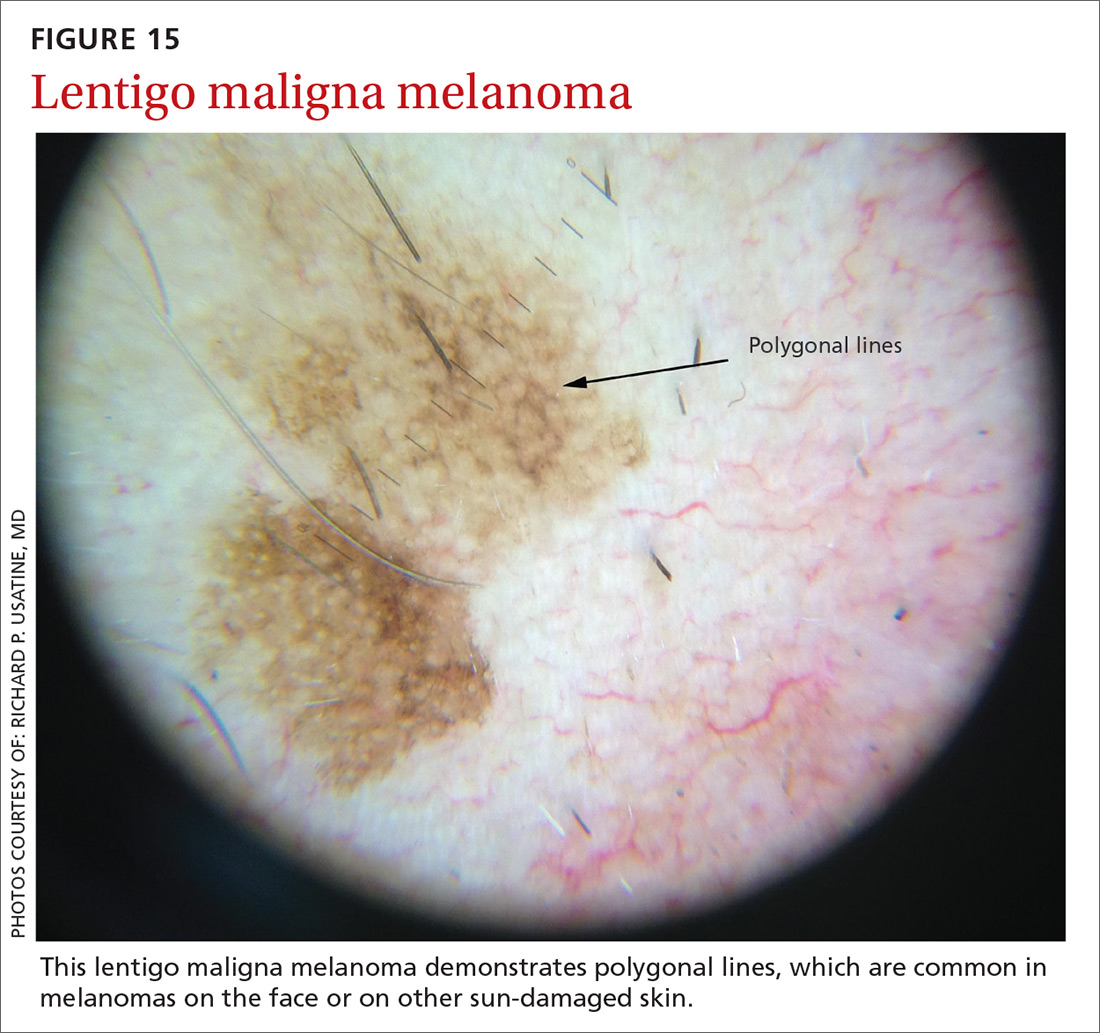

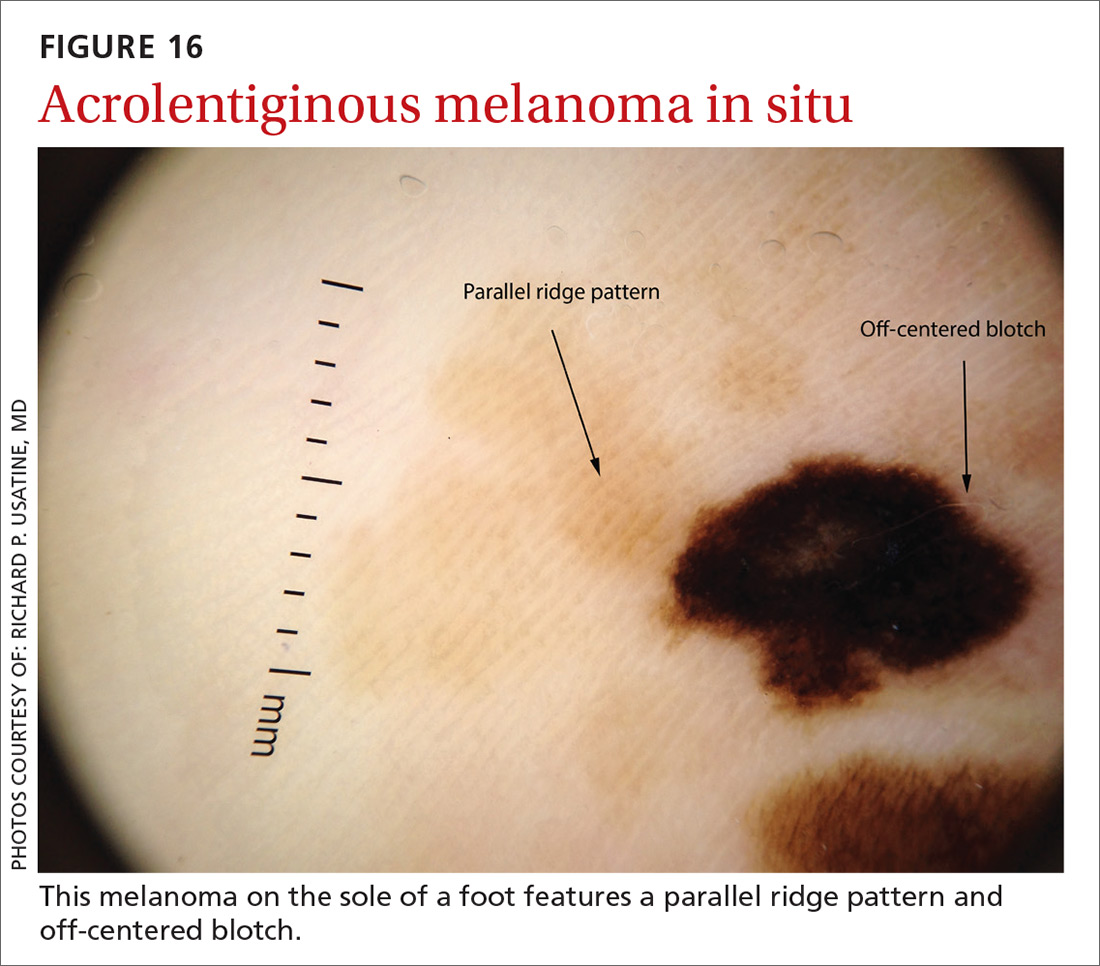

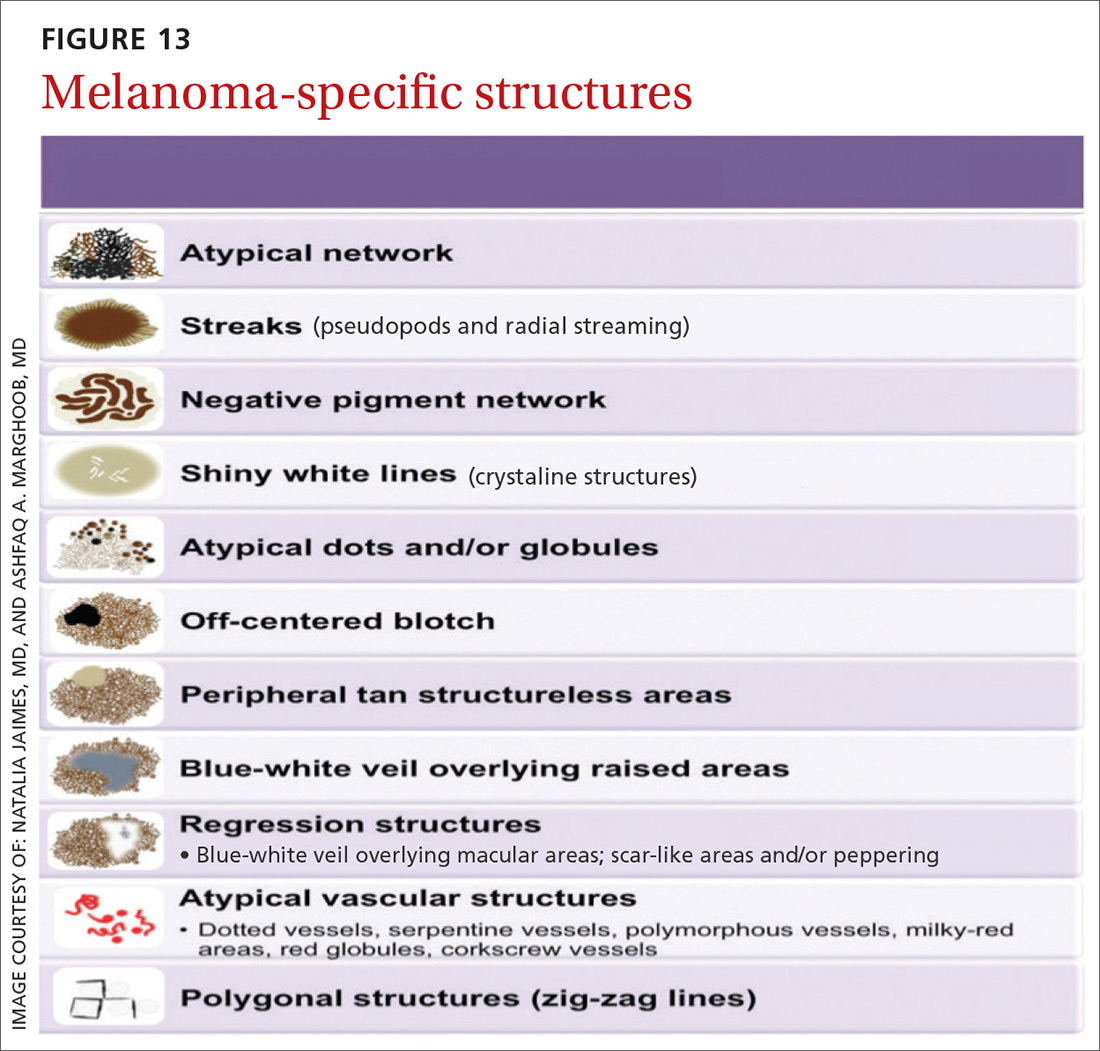

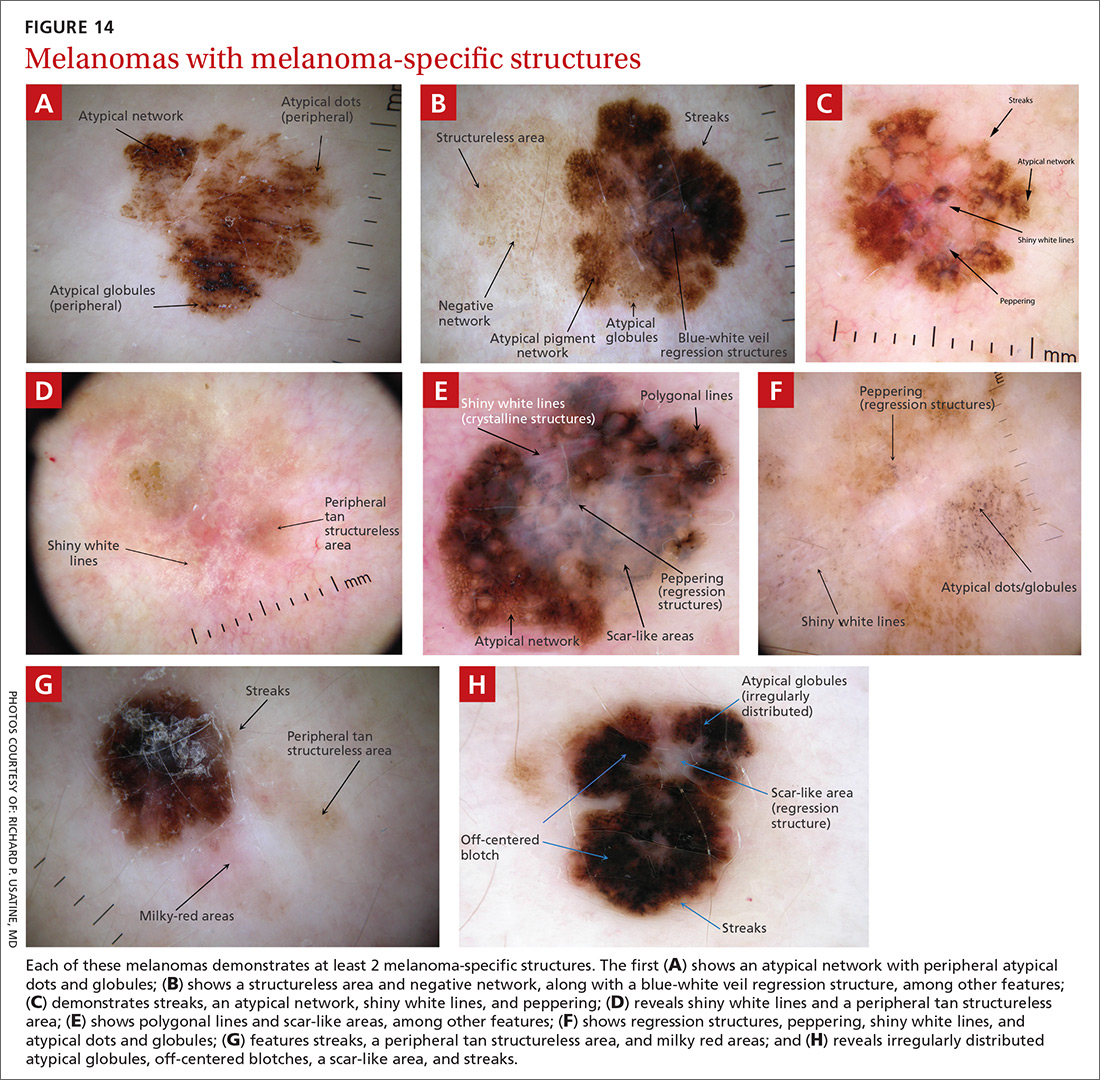

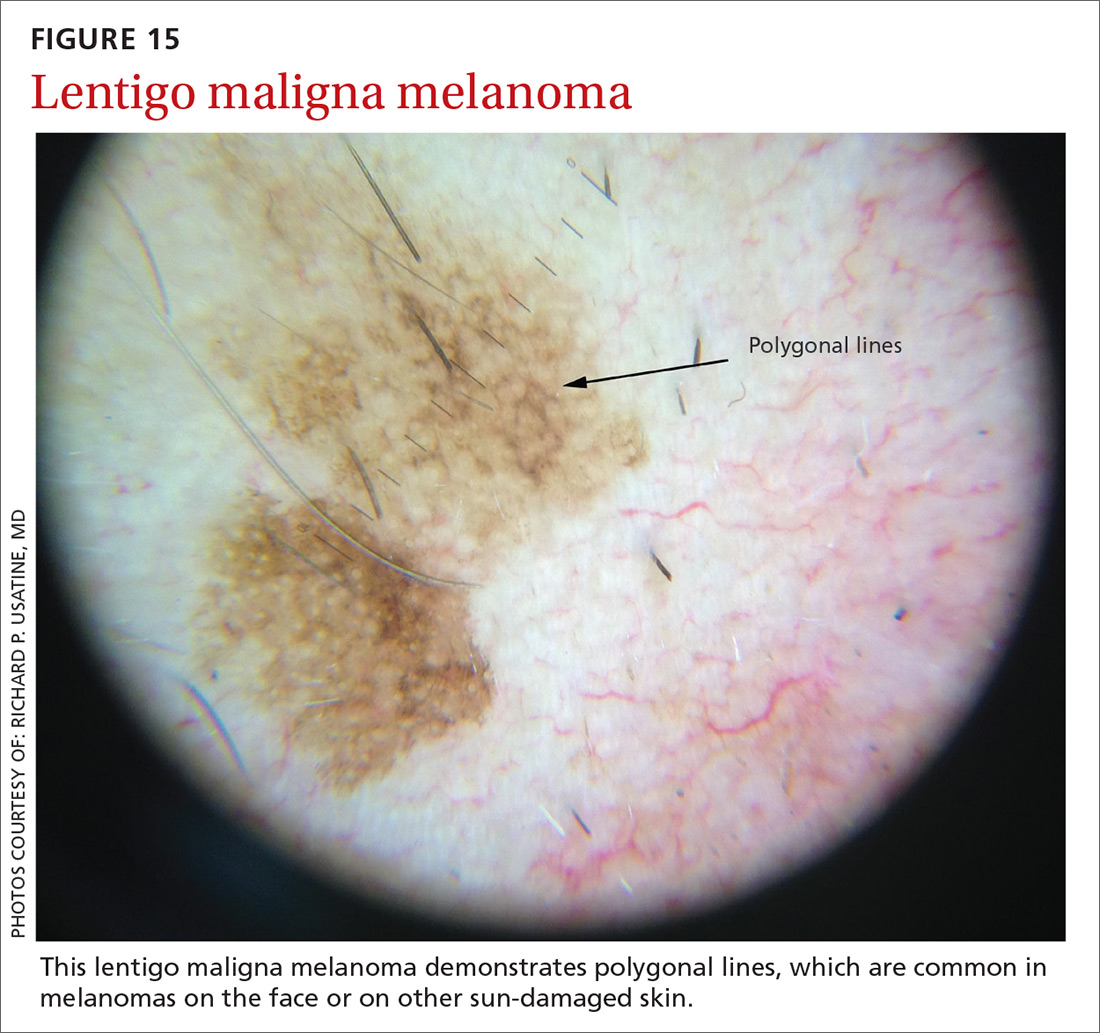

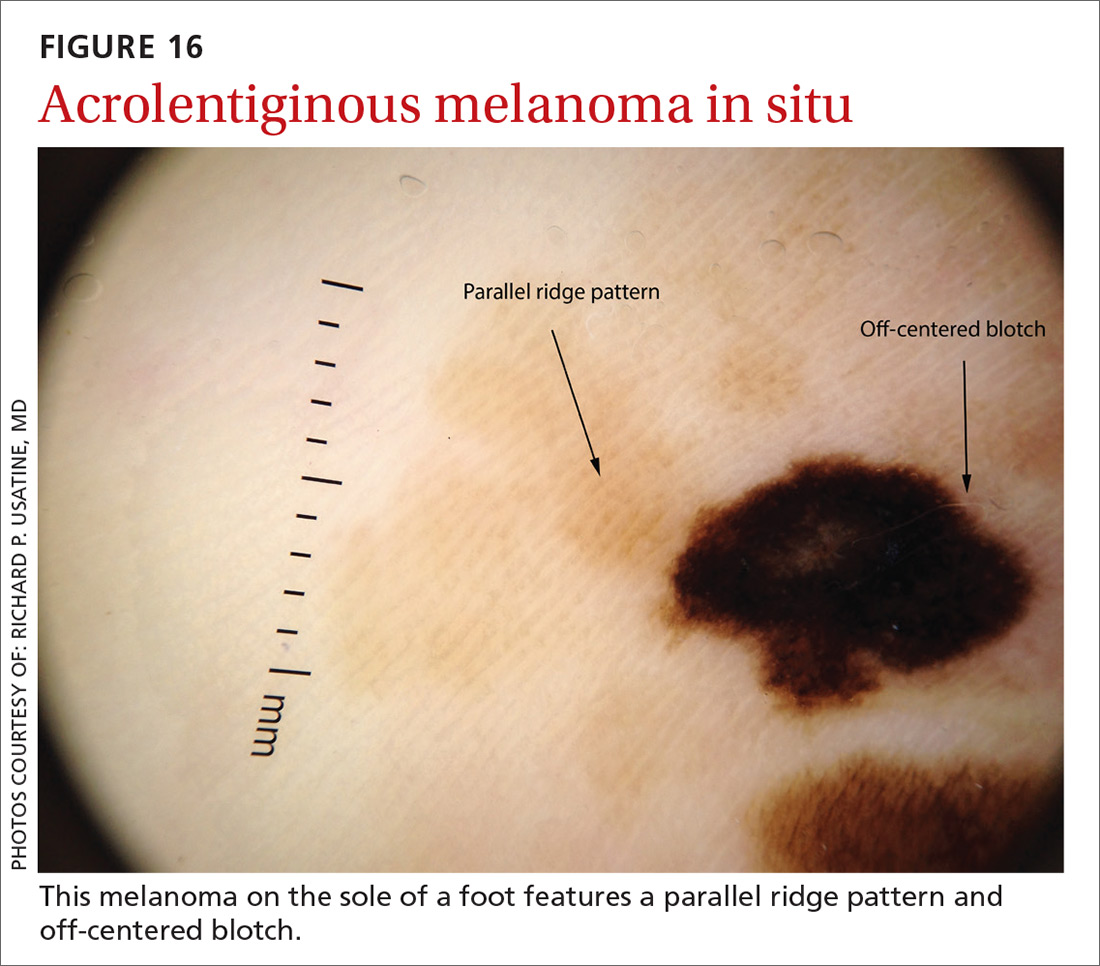

Melanomas tend to deviate from the benign patterns described earlier. Structures in melanomas are often distributed in an asymmetric fashion (which is the basis for diagnosis in many of the other algorithms), and most of them will reveal 1 or more of the melanoma-specific structures (FIGURE 13). The melanomas in FIGURES 14 A-H each show at least 2 melanoma-specific structures. On the face or sun-damaged skin, melanoma may present with grey color, a circle-in-circle pattern, and/or polygonal lines (FIGURE 15). Note that melanoma on the soles or palms may present with a parallel ridge pattern (FIGURE 16).

How to proceed after the evaluation of melanocytic lesions

After evaluating the lesion for benign patterns and melanoma-specific structures, there are 3 possible pathways:

1. The lesion adheres to one of the nevi patterns and does not display a melanoma-specific structure. You can reassure the patient that the lesion is benign.

2. The lesion:

A. Adheres to one nevus pattern, but also displays a melanoma-specific structure.

B. Does not adhere to any of the benign patterns and does not have any melanoma-specific structures.

This is considered a suspicious lesion, and the choices of action include performing a biopsy or short-term monitoring by comparing dermoscopic images over a 3-month interval. (Caveat: Never monitor raised lesions because nodular melanomas can grow quickly and develop a worsened prognosis in a short time. Instead you’ll want to biopsy the lesion that day or very soon thereafter.)

3. The lesion deviates from the benign patterns and has at least 1 melanoma-specific structure. Biopsy the lesion to rule out melanoma.

Continue to: A bonus...

A bonus: Diagnosing scabies

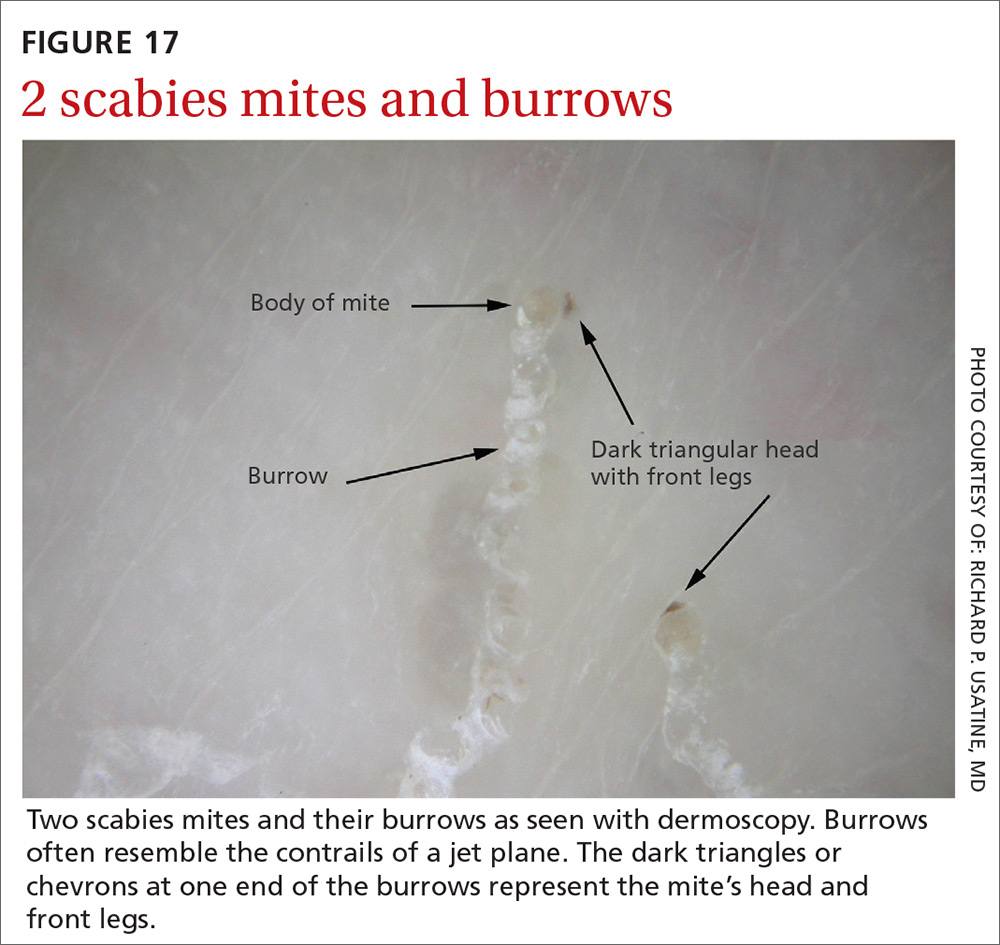

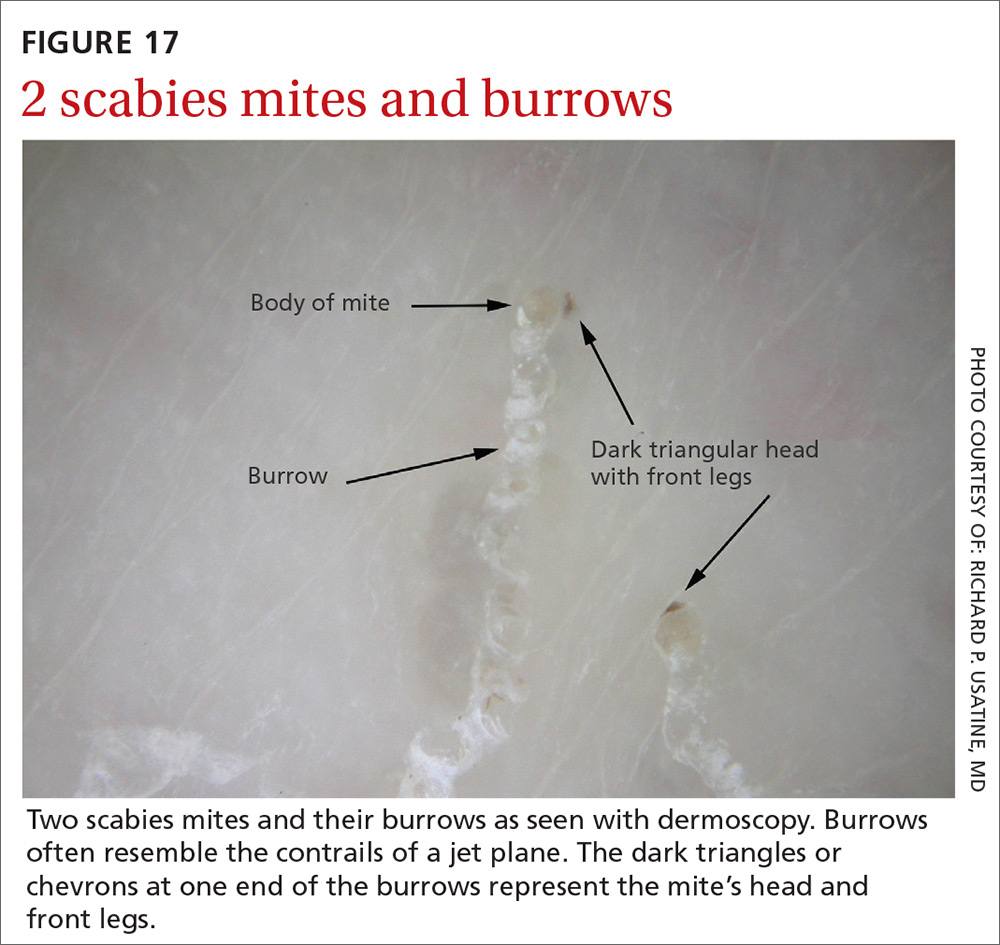

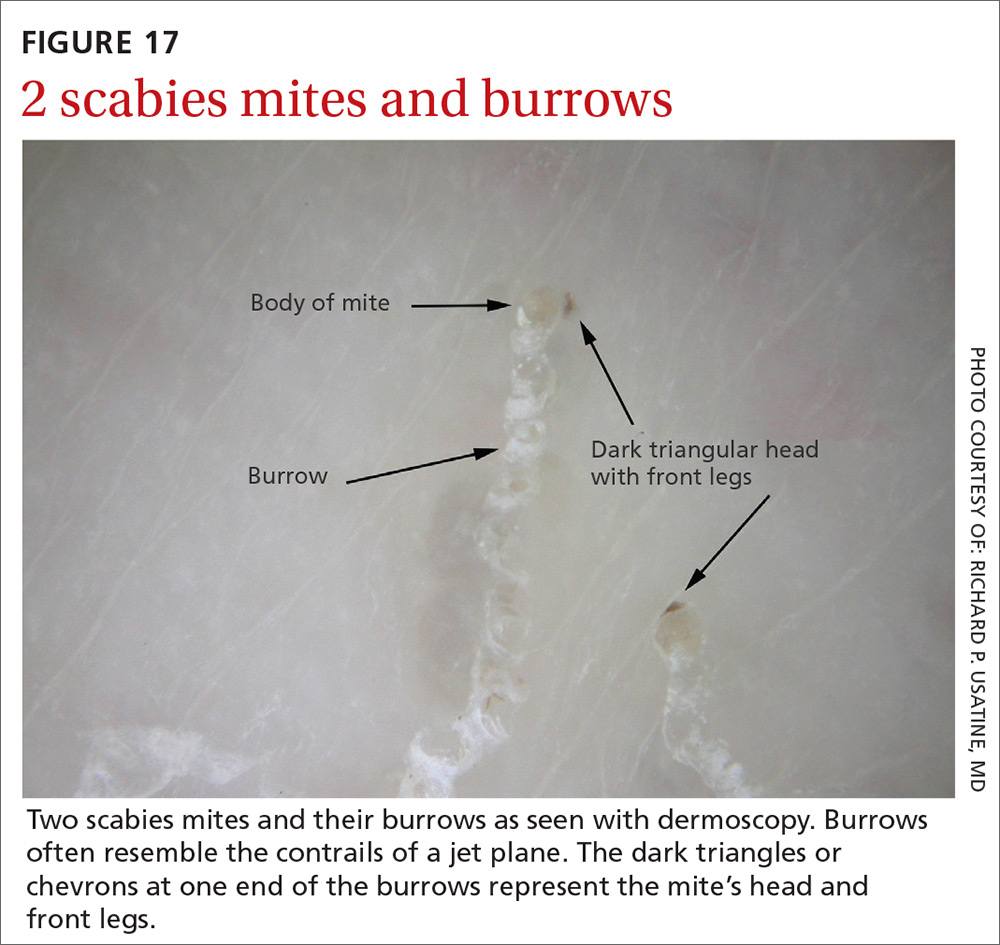

Increasingly, dermoscopy is being used in the diagnosis of many other skin, nail, and hair problems. In fact, one great bonus to owning a dermatoscope is the accurate diagnosis of scabies. Dermoscopy can be helpful in detecting the scabies mite without having to scrape and use the microscope. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of a dermoscopic diagnosis is higher than for scraping and microscopy.19

What you’ll see

The anterior legs and mouth parts of the mite resemble a triangle (arrowhead, delta-wing jet) (FIGURE 17). Look for a burrow, and the mite can be seen at the end of the burrow as a faint circle with a leading darker triangle. The burrow itself has a distinctive pattern that has more morphology than an excoriation and has been described as the contrail of a jet plane. Using a dermatoscope attached to your smartphone allows you to magnify the image even further while maintaining a safe distance from the mite.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, 903 W. Martin, Skin Clinic – Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected].

1. Herschorn A. Dermoscopy for melanoma detection in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:740-745.

2. Buckley D, McMonagle C. Melanoma in primary care. The role of the general practitioner. Ir J Med Sci. 2014;183:363-368.

3. Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T, et al. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part I Epidemiology, high-risk groups, clinical strategies, and diagnostic technology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:599.e1-599.e12.

4. Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T, et al. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part II Screening, education, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:611.e1-611.e10.

5. Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, et al. Use of and intentions to use dermoscopy among physicians in the United States. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:2.

6. Salerni G, Terán T, Alonso C, et al. The role of dermoscopy and digital dermoscopy follow-up in the clinical diagnosis of melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features of 99 consecutive primary melanomas. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:39-46.

7. Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

8. Westerhoff K, McCarthy WH, Menzies SW. Increase in the sensitivity for melanoma diagnosis by primary care physicians using skin surface microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1016-1020.

9. Menzies SW, Emery J, Staples M, et al. Impact of dermoscopy and short-term sequential digital dermoscopy imaging for the management of pigmented lesions in primary care: a sequential intervention trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1270-1277.

10. Kittler H. Dermatoscopy: introduction of a new algorithmic method based on pattern analysis for diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions. Dermatopathology: Practical & Conceptual. 2007;13:3.

11. Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, et al. Standardization of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1093-1106.

12. Stolz W, Riemann A, Cognetta AB, et al. ABCD rule of dermoscopy: a new practical method for early recognition of malignant melanoma. Eur J Dermatol. 1994;4:521-527.

13. Pehamberger H, Steiner A, Wolff K. In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions I Pattern analysis of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:571-583.

14. Menzies SW, Ingvar C, McCarthy WH. A sensitivity and specificity analysis of the surface microscopy features of invasive melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1996;6:55-62.

15. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, et al. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. Comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1563-1570.

16. Henning JS, Dusza SW, Wang SQ, et al. The CASH (color, architecture, symmetry, and homogeneity) algorithm for dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:45-52.

17. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, et al. Three-point checklist of dermoscopy. A new screening method for early detection of melanoma. Dermatology. 2004;208:27-31.

18. Lallas A, Moscarella E, Longo C, et al. Likelihood of finding melanoma when removing a Spitzoid-looking lesion in patients aged 12 years or older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:47-53.

19. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

Dermoscopy, the use of a handheld instrument to magnify the skin 10-fold while providing a light source, is a quick, useful, cost-effective tool for detecting melanoma in family medicine.1-4 The device, which allows the physician to visualize structures below the stratum corneum that are not routinely discernible with the naked eye, can be attached to a smartphone so that photos can be taken and reviewed with the patient. The photo can also be reviewed after a biopsy result is obtained.

Its use among non-dermatologist US physicians appears to be relatively low, but rising. One small study of physicians working in family medicine, internal medicine, and plastic surgery found that only 15% had ever used a dermatoscope and 6% were currently using one.5

As a family physician, you can expand your diagnostic abilities in dermatology with the acquisition of a dermatoscope (FIGURE 1) and some time invested in learning to interpret visible patterns. With that in mind, this review focuses on the diagnosis of skin cancers and benign growths using dermoscopy. We begin with a brief look at the research on dermoscopy and how it is performed. From there, we’ll detail an algorithm to guide dermoscopic analysis. And to round things out, we provide guidance that will help you to get started. (See “Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it,” and “To learn more about dermoscopy …”.)

SIDEBAR

Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it

1. Consider acquiring a hybrid dermatoscope.

Nonpolarized dermatoscopes (NPDs) and polarized dermatoscopes (PDs) provide different but complementary information. PDs enable users to identify features such as vessels and shiny white structures that are highly indicative of skin cancer. Because PDs are highly sensitive for detecting skin cancer and do not require a liquid interface or direct skin contact, they are the ideal dermatoscopes to use for skin cancer screening.

However, maintaining the highest specificity requires the complementary use of NPDs, which are better at identifying surface structures seen in seborrheic keratoses and other benign lesions. Thus, if the aim is to maintain the highest diagnostic accuracy for all types of lesions, then the preferred dermatoscope is a hybrid that permits the user to toggle between polarized and nonpolarized features in one device.

2. Choose a dermatoscope that attaches to your smartphone and/or camera.

This helps you capture digital dermoscopic images that can be analyzed on a larger screen, which permits:

- enlarging certain areas for in-depth analysis of structures and patterns

- sharing the image with the patient to explain why a biopsy is, or isn’t, needed

- sharing the image with a colleague for the purpose of a consult or a referral, or using the images for teaching purposes

- saving the images in order to follow lesions over time when monitoring is indicated

- ongoing learning. After each biopsy result comes back, we recommend correlating the dermoscopic images with the biopsy report. If your suspected diagnosis was correct, this reinforces your knowledge. If the pathology diagnosis is unexpected, you can learn by revisiting the original images to look for structures or patterns you may have missed upon first examination. You may even question the pathology report based on the dermoscopy, prompting a call to the pathologist.

- keeping a safe distance from the patient when looking for scabies mites.

SIDEBAR

To learn more about dermoscopy…

FREE APPS:

Dermoscopy 2-Step Algorithm. Available for free on iTunes, Google Play, and at https://usatinemedia.com/app/dermoscopy-two-step-algorithm/, this free app (developed by 3 of the 4 authors) is intended to help you interpret the dermoscopic patterns seen with your dermatoscope. It asks a series of questions that lead you to the most probable diagnosis. The app also contains more than 80 photos and charts to help you with your diagnosis. No Internet connection is needed to view the full app. There are 50 interactive cases to solve.

YOUdermoscopy Training (Available for free on iTunes, Google Play, and at https://www.youdermoscopytraining.org/) offers a fun game interface to test and expand your dermoscopy skills.

OTHER INTERNET RESOURCES:

- Dermoscopedia provides state-of-the-art information on dermoscopy. It’s available at: https://dermoscopedia.org.

- A free dermoscopy tutorial is available at: http://www.dermoscopy.org/

- The International Dermoscopy Society’s Web site, which offers various tutorials and other information, can be found at: http://www.dermoscopy-ids.org/.

COURSES:

Dermoscopy courses are a great way to get started and/or to advance your skills. The following courses are taught by the authors of this article:

- The American Dermoscopy Meeting is held yearly in the summer in a national park. See http://www.americandermoscopy.com/.

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center holds a yearly dermoscopy workshop each fall in New York City. See http://www.mskcc.org/events/.

- The yearly American Academy of Family Physicians' FMX meeting offers dermoscopy workshops. See https://www.aafp.org/events/fmx.html.

Continue to: What the research says

What the research says

Dermoscopy improves sensitivity for detecting melanoma over the naked eye alone; it also allows for the detection of melanoma at earlier stages, which improves prognosis.6

A meta-analysis of dermoscopy use in clinical settings showed that, following training, dermoscopy increases the average sensitivity of melanoma diagnosis from 71% to more than 90% without a significant decrease in specificity.7 In a study of 74 primary care physicians, there was an improvement in both clinical and dermoscopic diagnosis of melanoma among those who received training in dermoscopy, compared with a control group.8 Another study found that primary care physicians can reduce their baseline benign-to-melanoma ratio (the number of suspicious benign lesions biopsied to find 1 melanoma) from 9.5:1 with naked eye examination to 3.5:1 with dermoscopy.9

The exam begins by choosing 1 of 3 modes of dermoscopy

Dermatoscopes can have a polarized or nonpolarized light source. Some dermatoscopes combine both types of light (hybrid dermatoscopes; see “Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it.”)

There are 3 modes of dermoscopy:

- nonpolarized contact dermoscopy

- polarized contact dermoscopy

- polarized non-contact dermoscopy.

Dermatoscopes with nonpolarized light require direct skin contact and a liquid interface (eg, alcohol, gel, mineral oil) between the scope’s glass plate and the skin for the visualization of subsurface structures. In contrast, dermatoscopes with polarized light do not require direct skin contact or a liquid interface; however, contacting the skin and using a liquid interface will provide a sharper image.

Continue to: Two major algorithms guide dermoscopic analysis

Two major algorithms guide dermoscopic analysis

The first of 2 major algorithms that can be used to guide dermoscopic analysis is a modified pattern analysis put forth by Kittler.10 This descriptive system based on geometric elements, patterns, colors, and clues guides the observer to a specific diagnosis without categorizing lesions as being either melanocytic or nonmelanocytic. Because this is not the preferred method of the authors, we will move on to Method 2.

The second method, a 2-step algorithm, is a qualitative system that guides the observer through differentiating melanocytic from nonmelanocytic lesions in order to differentiate nevi from melanoma (FIGURE 2). At the same time, it serves as an aid to correctly diagnose non-melanocytic lesions. The 2-step algorithm forms the foundation for the dermoscopic evaluation of skin lesions in this article.

Not all expert dermoscopists employ structured analytical systems or methods to reach a diagnosis. Because of their vast experience, many rely purely on pattern recognition. But algorithms can facilitate non-experts in dermoscopy in the differentiation of nevi from melanoma or, simply, in differentiating the benign from the malignant.

Although each algorithm has its unique criteria, all of them require training and practice and familiarity with the terms used to describe morphologic structures. The International Dermoscopy Society recently published a consensus paper designating some terms as preferred over others.11

Continue to: Step 1...

Step 1: Melanocytic vs non-melanocytic

Step 1 of the 2-step algorithm requires the observer to determine whether the lesion is melanocytic (ie, originates from melanocytes and, therefore, could be a melanoma) or nonmelanocytic in origin.

A melanocytic lesion usually will display at least 1 of the following structures:

- pigment network (FIGURE 3A) (This can include angulated lines.)

- negative network (FIGURE 3B) (hypopigmented lines connecting pigmented structures in a serpiginous fashion)

- streaks (FIGURE 3C)

- homogeneous blue pigmentation (FIGURE 3D)

- globules (aggregated or as a peripheral rim) (FIGURE 3E)

- pseudonetwork (facial skin) (FIGURE 3F)

- parallel pigment pattern (acral lesions) (FIGURE 3G).

Exceptions. Sometimes, nonmelanocytic lesions will present with pigment network. Dermatofibromas, for example, are one exception in which the pattern trumps the network. Two other exceptions are solar lentigo and supernumerary or accessory nipple.

If the lesion does not display any structure, it is considered structureless. In these cases, proceed to the second step to rule out a melanoma.

Doesn’t meet criteria for a melanocytic lesion?

If the lesion does not reveal any of the criteria for a melanocytic lesion, then look for structures seen in nonmelanocytic lesions: dermatofibromas; seborrheic keratosis; angiomas and angiokeratomas; sebaceous hyperplasia; clear-cell acanthomas; basal cell carcinomas (BCCs); and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs).

Continue to: Benign nonmelanocytic lesions

Benign nonmelanocytic lesions

Dermatofibromas are benign symmetric lesions that feel firm and may dimple upon application of lateral pressure. They are fibrotic scar-like lesions that present with 1 or more of the following dermoscopic features (FIGURE 4):

- peripheral pigment network, due to increased melanin in keratinocytes

- homogeneous brown pigmented areas

- central scar-like area

- shiny white lines

- vascular structures (ie, dotted, polymorphous vessels), usually seen within the scar-like area

- ring-like globules, usually seen in the zone between the scar-like depigmentation and the peripheral network. They correspond to widened hyperpigmented rete ridges.

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign skin growth that often has a stuck-on appearance (FIGURE 5). Features often include:

- multiple (>2) milia-like cysts

- comedo-like openings

- a network-like structure that corresponds to gyri and sulci and which in some cases can create a cerebriform pattern

- fingerprint-like structures

- moth-eaten borders

- jelly sign. This consists of semicircular u-shaped structures that have a smudged appearance and are aligned in the same direction. The appearance resembles jelly as it is spread on a piece of bread.

- hairpin (looped or twisted-looped) vessels surrounded by a white halo.

Other clues include a sharp demarcation and a negative wobble sign (which we’ll describe in a moment). The presence or absence of a wobble sign is determined by using a dermatoscope that touches the skin. Mild vertical pressure is applied to the lesion while moving the scope back and forth horizontally. If the lesion slides across the skin surface, the diagnosis of an epidermal keratinocytic tumor (ie, SK) is favored. If, on the other hand, the lesion wobbles (rolls back and forth), then the diagnosis of a neoplasm with a dermal component (ie, intradermal or compound nevus) is more likely.

Angiomas and angiokeratomas. Angiomas demonstrate lacunae that are often separated by septae (FIGURE 6). Lacunae can vary in size and color. They can be red, red-white, red-blue, maroon, blue, blue-black, or even black (when thrombosis is present).

Angiokeratomas (FIGURE 7) can reveal lacunae of varying colors including black, red, purple, and maroon. In addition, a blue-whitish veil, erythema, and hemorrhagic crusts can be present.

Continue to: Sebaceous hyperplasia...

Sebaceous hyperplasia is the overgrowth of sebaceous glands. It can mimic BCC on the face. Sebaceous hyperplasia presents with multiple vessels in a crown-like arrangement that do not cross the center of the lesion. The sebaceous glands resemble popcorn (FIGURE 8).

Clear-cell acanthoma is a benign erythematous epidermal tumor usually found on the leg with a string-of-pearls pattern. This pattern is vascular so the pearls are red in color (FIGURE 9).

Malignant nonmelanocytic lesions

BCC is the most common type of skin cancer. Features often include:

- spoke-wheel-like structures or concentric structures (FIGURE 10A)

- leaf-like areas (FIGURE 10B)

- arborizing vessels (FIGURE 10b and 10C)large blue-gray ovoid nest (FIGURE 10A)

- multiple blue-gray non-aggregated globules

- ulceration or multiple small erosions

- shiny white structures and strands (FIGURE 10C).

Additional dermoscopic clues include short, fine, superficial telangiectasias and multiple in-focus dots in a buck-shot scatter distribution.

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of the skin are keratinizing malignant tumors. Each SCC generally has some of the following features (FIGURE 11):

- dotted and/or glomerular vessels, commonly distributed focally at the periphery. They can also be diffuse or aligned linearly within the lesion.

- scale (yellow or white)

- rosettes (seen with polarized light)

- white circles or keratin pearls

- brown circles

- ulcerations

- brown dots or globules arranged in a linear configuration.

Continue to: Step 2...

Step 2: It’s melanocytic, but is it a nevus or a melanoma?

If, by following Step 1 of the algorithm, the lesion is determined to be of melanocytic origin, then one proceeds to Step 2 to decide whether the growth is a nevus, a suspicious lesion, or a melanoma. For this purpose, several additional algorithms are available.12-17

Benign nevi tend to manifest with 1 of the following 10 patterns: (FIGURE 12)

- diffuse reticular

- patchy reticular

- peripheral reticular with central hypopigmentation

- peripheral reticular with central hyperpigmentation

- homogeneous

- peripheral globules/starburst. It has been suggested that lesions that show starburst morphology on dermoscopy require complete excision and follow-up since 13% of Spitzoid-looking symmetric lesions in patients older than 12 years were found to be melanoma in one study.18

- peripheral reticular with central globules

- globular

- 2-component

- symmetric multicomponent (this pattern should be interpreted with caution, and a biopsy is probably warranted for dermoscopic novices).

Melanomas tend to deviate from the benign patterns described earlier. Structures in melanomas are often distributed in an asymmetric fashion (which is the basis for diagnosis in many of the other algorithms), and most of them will reveal 1 or more of the melanoma-specific structures (FIGURE 13). The melanomas in FIGURES 14 A-H each show at least 2 melanoma-specific structures. On the face or sun-damaged skin, melanoma may present with grey color, a circle-in-circle pattern, and/or polygonal lines (FIGURE 15). Note that melanoma on the soles or palms may present with a parallel ridge pattern (FIGURE 16).

How to proceed after the evaluation of melanocytic lesions

After evaluating the lesion for benign patterns and melanoma-specific structures, there are 3 possible pathways:

1. The lesion adheres to one of the nevi patterns and does not display a melanoma-specific structure. You can reassure the patient that the lesion is benign.

2. The lesion:

A. Adheres to one nevus pattern, but also displays a melanoma-specific structure.

B. Does not adhere to any of the benign patterns and does not have any melanoma-specific structures.

This is considered a suspicious lesion, and the choices of action include performing a biopsy or short-term monitoring by comparing dermoscopic images over a 3-month interval. (Caveat: Never monitor raised lesions because nodular melanomas can grow quickly and develop a worsened prognosis in a short time. Instead you’ll want to biopsy the lesion that day or very soon thereafter.)

3. The lesion deviates from the benign patterns and has at least 1 melanoma-specific structure. Biopsy the lesion to rule out melanoma.

Continue to: A bonus...

A bonus: Diagnosing scabies

Increasingly, dermoscopy is being used in the diagnosis of many other skin, nail, and hair problems. In fact, one great bonus to owning a dermatoscope is the accurate diagnosis of scabies. Dermoscopy can be helpful in detecting the scabies mite without having to scrape and use the microscope. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of a dermoscopic diagnosis is higher than for scraping and microscopy.19

What you’ll see

The anterior legs and mouth parts of the mite resemble a triangle (arrowhead, delta-wing jet) (FIGURE 17). Look for a burrow, and the mite can be seen at the end of the burrow as a faint circle with a leading darker triangle. The burrow itself has a distinctive pattern that has more morphology than an excoriation and has been described as the contrail of a jet plane. Using a dermatoscope attached to your smartphone allows you to magnify the image even further while maintaining a safe distance from the mite.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, 903 W. Martin, Skin Clinic – Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected].

Dermoscopy, the use of a handheld instrument to magnify the skin 10-fold while providing a light source, is a quick, useful, cost-effective tool for detecting melanoma in family medicine.1-4 The device, which allows the physician to visualize structures below the stratum corneum that are not routinely discernible with the naked eye, can be attached to a smartphone so that photos can be taken and reviewed with the patient. The photo can also be reviewed after a biopsy result is obtained.

Its use among non-dermatologist US physicians appears to be relatively low, but rising. One small study of physicians working in family medicine, internal medicine, and plastic surgery found that only 15% had ever used a dermatoscope and 6% were currently using one.5

As a family physician, you can expand your diagnostic abilities in dermatology with the acquisition of a dermatoscope (FIGURE 1) and some time invested in learning to interpret visible patterns. With that in mind, this review focuses on the diagnosis of skin cancers and benign growths using dermoscopy. We begin with a brief look at the research on dermoscopy and how it is performed. From there, we’ll detail an algorithm to guide dermoscopic analysis. And to round things out, we provide guidance that will help you to get started. (See “Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it,” and “To learn more about dermoscopy …”.)

SIDEBAR

Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it

1. Consider acquiring a hybrid dermatoscope.

Nonpolarized dermatoscopes (NPDs) and polarized dermatoscopes (PDs) provide different but complementary information. PDs enable users to identify features such as vessels and shiny white structures that are highly indicative of skin cancer. Because PDs are highly sensitive for detecting skin cancer and do not require a liquid interface or direct skin contact, they are the ideal dermatoscopes to use for skin cancer screening.

However, maintaining the highest specificity requires the complementary use of NPDs, which are better at identifying surface structures seen in seborrheic keratoses and other benign lesions. Thus, if the aim is to maintain the highest diagnostic accuracy for all types of lesions, then the preferred dermatoscope is a hybrid that permits the user to toggle between polarized and nonpolarized features in one device.

2. Choose a dermatoscope that attaches to your smartphone and/or camera.

This helps you capture digital dermoscopic images that can be analyzed on a larger screen, which permits:

- enlarging certain areas for in-depth analysis of structures and patterns

- sharing the image with the patient to explain why a biopsy is, or isn’t, needed

- sharing the image with a colleague for the purpose of a consult or a referral, or using the images for teaching purposes

- saving the images in order to follow lesions over time when monitoring is indicated

- ongoing learning. After each biopsy result comes back, we recommend correlating the dermoscopic images with the biopsy report. If your suspected diagnosis was correct, this reinforces your knowledge. If the pathology diagnosis is unexpected, you can learn by revisiting the original images to look for structures or patterns you may have missed upon first examination. You may even question the pathology report based on the dermoscopy, prompting a call to the pathologist.

- keeping a safe distance from the patient when looking for scabies mites.

SIDEBAR

To learn more about dermoscopy…

FREE APPS:

Dermoscopy 2-Step Algorithm. Available for free on iTunes, Google Play, and at https://usatinemedia.com/app/dermoscopy-two-step-algorithm/, this free app (developed by 3 of the 4 authors) is intended to help you interpret the dermoscopic patterns seen with your dermatoscope. It asks a series of questions that lead you to the most probable diagnosis. The app also contains more than 80 photos and charts to help you with your diagnosis. No Internet connection is needed to view the full app. There are 50 interactive cases to solve.

YOUdermoscopy Training (Available for free on iTunes, Google Play, and at https://www.youdermoscopytraining.org/) offers a fun game interface to test and expand your dermoscopy skills.

OTHER INTERNET RESOURCES:

- Dermoscopedia provides state-of-the-art information on dermoscopy. It’s available at: https://dermoscopedia.org.

- A free dermoscopy tutorial is available at: http://www.dermoscopy.org/

- The International Dermoscopy Society’s Web site, which offers various tutorials and other information, can be found at: http://www.dermoscopy-ids.org/.

COURSES:

Dermoscopy courses are a great way to get started and/or to advance your skills. The following courses are taught by the authors of this article:

- The American Dermoscopy Meeting is held yearly in the summer in a national park. See http://www.americandermoscopy.com/.

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center holds a yearly dermoscopy workshop each fall in New York City. See http://www.mskcc.org/events/.

- The yearly American Academy of Family Physicians' FMX meeting offers dermoscopy workshops. See https://www.aafp.org/events/fmx.html.

Continue to: What the research says

What the research says

Dermoscopy improves sensitivity for detecting melanoma over the naked eye alone; it also allows for the detection of melanoma at earlier stages, which improves prognosis.6

A meta-analysis of dermoscopy use in clinical settings showed that, following training, dermoscopy increases the average sensitivity of melanoma diagnosis from 71% to more than 90% without a significant decrease in specificity.7 In a study of 74 primary care physicians, there was an improvement in both clinical and dermoscopic diagnosis of melanoma among those who received training in dermoscopy, compared with a control group.8 Another study found that primary care physicians can reduce their baseline benign-to-melanoma ratio (the number of suspicious benign lesions biopsied to find 1 melanoma) from 9.5:1 with naked eye examination to 3.5:1 with dermoscopy.9

The exam begins by choosing 1 of 3 modes of dermoscopy

Dermatoscopes can have a polarized or nonpolarized light source. Some dermatoscopes combine both types of light (hybrid dermatoscopes; see “Choosing a dermatoscope—and making the most of it.”)

There are 3 modes of dermoscopy:

- nonpolarized contact dermoscopy

- polarized contact dermoscopy

- polarized non-contact dermoscopy.

Dermatoscopes with nonpolarized light require direct skin contact and a liquid interface (eg, alcohol, gel, mineral oil) between the scope’s glass plate and the skin for the visualization of subsurface structures. In contrast, dermatoscopes with polarized light do not require direct skin contact or a liquid interface; however, contacting the skin and using a liquid interface will provide a sharper image.

Continue to: Two major algorithms guide dermoscopic analysis

Two major algorithms guide dermoscopic analysis

The first of 2 major algorithms that can be used to guide dermoscopic analysis is a modified pattern analysis put forth by Kittler.10 This descriptive system based on geometric elements, patterns, colors, and clues guides the observer to a specific diagnosis without categorizing lesions as being either melanocytic or nonmelanocytic. Because this is not the preferred method of the authors, we will move on to Method 2.

The second method, a 2-step algorithm, is a qualitative system that guides the observer through differentiating melanocytic from nonmelanocytic lesions in order to differentiate nevi from melanoma (FIGURE 2). At the same time, it serves as an aid to correctly diagnose non-melanocytic lesions. The 2-step algorithm forms the foundation for the dermoscopic evaluation of skin lesions in this article.

Not all expert dermoscopists employ structured analytical systems or methods to reach a diagnosis. Because of their vast experience, many rely purely on pattern recognition. But algorithms can facilitate non-experts in dermoscopy in the differentiation of nevi from melanoma or, simply, in differentiating the benign from the malignant.

Although each algorithm has its unique criteria, all of them require training and practice and familiarity with the terms used to describe morphologic structures. The International Dermoscopy Society recently published a consensus paper designating some terms as preferred over others.11

Continue to: Step 1...

Step 1: Melanocytic vs non-melanocytic

Step 1 of the 2-step algorithm requires the observer to determine whether the lesion is melanocytic (ie, originates from melanocytes and, therefore, could be a melanoma) or nonmelanocytic in origin.

A melanocytic lesion usually will display at least 1 of the following structures:

- pigment network (FIGURE 3A) (This can include angulated lines.)

- negative network (FIGURE 3B) (hypopigmented lines connecting pigmented structures in a serpiginous fashion)

- streaks (FIGURE 3C)

- homogeneous blue pigmentation (FIGURE 3D)

- globules (aggregated or as a peripheral rim) (FIGURE 3E)

- pseudonetwork (facial skin) (FIGURE 3F)

- parallel pigment pattern (acral lesions) (FIGURE 3G).

Exceptions. Sometimes, nonmelanocytic lesions will present with pigment network. Dermatofibromas, for example, are one exception in which the pattern trumps the network. Two other exceptions are solar lentigo and supernumerary or accessory nipple.

If the lesion does not display any structure, it is considered structureless. In these cases, proceed to the second step to rule out a melanoma.

Doesn’t meet criteria for a melanocytic lesion?

If the lesion does not reveal any of the criteria for a melanocytic lesion, then look for structures seen in nonmelanocytic lesions: dermatofibromas; seborrheic keratosis; angiomas and angiokeratomas; sebaceous hyperplasia; clear-cell acanthomas; basal cell carcinomas (BCCs); and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs).

Continue to: Benign nonmelanocytic lesions

Benign nonmelanocytic lesions

Dermatofibromas are benign symmetric lesions that feel firm and may dimple upon application of lateral pressure. They are fibrotic scar-like lesions that present with 1 or more of the following dermoscopic features (FIGURE 4):

- peripheral pigment network, due to increased melanin in keratinocytes

- homogeneous brown pigmented areas

- central scar-like area

- shiny white lines

- vascular structures (ie, dotted, polymorphous vessels), usually seen within the scar-like area

- ring-like globules, usually seen in the zone between the scar-like depigmentation and the peripheral network. They correspond to widened hyperpigmented rete ridges.

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is a benign skin growth that often has a stuck-on appearance (FIGURE 5). Features often include:

- multiple (>2) milia-like cysts

- comedo-like openings

- a network-like structure that corresponds to gyri and sulci and which in some cases can create a cerebriform pattern

- fingerprint-like structures

- moth-eaten borders

- jelly sign. This consists of semicircular u-shaped structures that have a smudged appearance and are aligned in the same direction. The appearance resembles jelly as it is spread on a piece of bread.

- hairpin (looped or twisted-looped) vessels surrounded by a white halo.

Other clues include a sharp demarcation and a negative wobble sign (which we’ll describe in a moment). The presence or absence of a wobble sign is determined by using a dermatoscope that touches the skin. Mild vertical pressure is applied to the lesion while moving the scope back and forth horizontally. If the lesion slides across the skin surface, the diagnosis of an epidermal keratinocytic tumor (ie, SK) is favored. If, on the other hand, the lesion wobbles (rolls back and forth), then the diagnosis of a neoplasm with a dermal component (ie, intradermal or compound nevus) is more likely.

Angiomas and angiokeratomas. Angiomas demonstrate lacunae that are often separated by septae (FIGURE 6). Lacunae can vary in size and color. They can be red, red-white, red-blue, maroon, blue, blue-black, or even black (when thrombosis is present).

Angiokeratomas (FIGURE 7) can reveal lacunae of varying colors including black, red, purple, and maroon. In addition, a blue-whitish veil, erythema, and hemorrhagic crusts can be present.

Continue to: Sebaceous hyperplasia...

Sebaceous hyperplasia is the overgrowth of sebaceous glands. It can mimic BCC on the face. Sebaceous hyperplasia presents with multiple vessels in a crown-like arrangement that do not cross the center of the lesion. The sebaceous glands resemble popcorn (FIGURE 8).

Clear-cell acanthoma is a benign erythematous epidermal tumor usually found on the leg with a string-of-pearls pattern. This pattern is vascular so the pearls are red in color (FIGURE 9).

Malignant nonmelanocytic lesions

BCC is the most common type of skin cancer. Features often include:

- spoke-wheel-like structures or concentric structures (FIGURE 10A)

- leaf-like areas (FIGURE 10B)

- arborizing vessels (FIGURE 10b and 10C)large blue-gray ovoid nest (FIGURE 10A)

- multiple blue-gray non-aggregated globules

- ulceration or multiple small erosions

- shiny white structures and strands (FIGURE 10C).

Additional dermoscopic clues include short, fine, superficial telangiectasias and multiple in-focus dots in a buck-shot scatter distribution.

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of the skin are keratinizing malignant tumors. Each SCC generally has some of the following features (FIGURE 11):

- dotted and/or glomerular vessels, commonly distributed focally at the periphery. They can also be diffuse or aligned linearly within the lesion.

- scale (yellow or white)

- rosettes (seen with polarized light)

- white circles or keratin pearls

- brown circles

- ulcerations

- brown dots or globules arranged in a linear configuration.

Continue to: Step 2...

Step 2: It’s melanocytic, but is it a nevus or a melanoma?

If, by following Step 1 of the algorithm, the lesion is determined to be of melanocytic origin, then one proceeds to Step 2 to decide whether the growth is a nevus, a suspicious lesion, or a melanoma. For this purpose, several additional algorithms are available.12-17

Benign nevi tend to manifest with 1 of the following 10 patterns: (FIGURE 12)

- diffuse reticular

- patchy reticular

- peripheral reticular with central hypopigmentation

- peripheral reticular with central hyperpigmentation

- homogeneous

- peripheral globules/starburst. It has been suggested that lesions that show starburst morphology on dermoscopy require complete excision and follow-up since 13% of Spitzoid-looking symmetric lesions in patients older than 12 years were found to be melanoma in one study.18

- peripheral reticular with central globules

- globular

- 2-component

- symmetric multicomponent (this pattern should be interpreted with caution, and a biopsy is probably warranted for dermoscopic novices).

Melanomas tend to deviate from the benign patterns described earlier. Structures in melanomas are often distributed in an asymmetric fashion (which is the basis for diagnosis in many of the other algorithms), and most of them will reveal 1 or more of the melanoma-specific structures (FIGURE 13). The melanomas in FIGURES 14 A-H each show at least 2 melanoma-specific structures. On the face or sun-damaged skin, melanoma may present with grey color, a circle-in-circle pattern, and/or polygonal lines (FIGURE 15). Note that melanoma on the soles or palms may present with a parallel ridge pattern (FIGURE 16).

How to proceed after the evaluation of melanocytic lesions

After evaluating the lesion for benign patterns and melanoma-specific structures, there are 3 possible pathways:

1. The lesion adheres to one of the nevi patterns and does not display a melanoma-specific structure. You can reassure the patient that the lesion is benign.

2. The lesion:

A. Adheres to one nevus pattern, but also displays a melanoma-specific structure.

B. Does not adhere to any of the benign patterns and does not have any melanoma-specific structures.

This is considered a suspicious lesion, and the choices of action include performing a biopsy or short-term monitoring by comparing dermoscopic images over a 3-month interval. (Caveat: Never monitor raised lesions because nodular melanomas can grow quickly and develop a worsened prognosis in a short time. Instead you’ll want to biopsy the lesion that day or very soon thereafter.)

3. The lesion deviates from the benign patterns and has at least 1 melanoma-specific structure. Biopsy the lesion to rule out melanoma.

Continue to: A bonus...

A bonus: Diagnosing scabies

Increasingly, dermoscopy is being used in the diagnosis of many other skin, nail, and hair problems. In fact, one great bonus to owning a dermatoscope is the accurate diagnosis of scabies. Dermoscopy can be helpful in detecting the scabies mite without having to scrape and use the microscope. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of a dermoscopic diagnosis is higher than for scraping and microscopy.19

What you’ll see

The anterior legs and mouth parts of the mite resemble a triangle (arrowhead, delta-wing jet) (FIGURE 17). Look for a burrow, and the mite can be seen at the end of the burrow as a faint circle with a leading darker triangle. The burrow itself has a distinctive pattern that has more morphology than an excoriation and has been described as the contrail of a jet plane. Using a dermatoscope attached to your smartphone allows you to magnify the image even further while maintaining a safe distance from the mite.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, 903 W. Martin, Skin Clinic – Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected].

1. Herschorn A. Dermoscopy for melanoma detection in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:740-745.

2. Buckley D, McMonagle C. Melanoma in primary care. The role of the general practitioner. Ir J Med Sci. 2014;183:363-368.

3. Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T, et al. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part I Epidemiology, high-risk groups, clinical strategies, and diagnostic technology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:599.e1-599.e12.

4. Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T, et al. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part II Screening, education, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:611.e1-611.e10.

5. Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, et al. Use of and intentions to use dermoscopy among physicians in the United States. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:2.

6. Salerni G, Terán T, Alonso C, et al. The role of dermoscopy and digital dermoscopy follow-up in the clinical diagnosis of melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features of 99 consecutive primary melanomas. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:39-46.

7. Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

8. Westerhoff K, McCarthy WH, Menzies SW. Increase in the sensitivity for melanoma diagnosis by primary care physicians using skin surface microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1016-1020.

9. Menzies SW, Emery J, Staples M, et al. Impact of dermoscopy and short-term sequential digital dermoscopy imaging for the management of pigmented lesions in primary care: a sequential intervention trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1270-1277.

10. Kittler H. Dermatoscopy: introduction of a new algorithmic method based on pattern analysis for diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions. Dermatopathology: Practical & Conceptual. 2007;13:3.

11. Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, et al. Standardization of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1093-1106.

12. Stolz W, Riemann A, Cognetta AB, et al. ABCD rule of dermoscopy: a new practical method for early recognition of malignant melanoma. Eur J Dermatol. 1994;4:521-527.

13. Pehamberger H, Steiner A, Wolff K. In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions I Pattern analysis of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:571-583.

14. Menzies SW, Ingvar C, McCarthy WH. A sensitivity and specificity analysis of the surface microscopy features of invasive melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1996;6:55-62.

15. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, et al. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. Comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1563-1570.

16. Henning JS, Dusza SW, Wang SQ, et al. The CASH (color, architecture, symmetry, and homogeneity) algorithm for dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:45-52.

17. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, et al. Three-point checklist of dermoscopy. A new screening method for early detection of melanoma. Dermatology. 2004;208:27-31.

18. Lallas A, Moscarella E, Longo C, et al. Likelihood of finding melanoma when removing a Spitzoid-looking lesion in patients aged 12 years or older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:47-53.

19. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

1. Herschorn A. Dermoscopy for melanoma detection in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:740-745.

2. Buckley D, McMonagle C. Melanoma in primary care. The role of the general practitioner. Ir J Med Sci. 2014;183:363-368.

3. Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T, et al. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part I Epidemiology, high-risk groups, clinical strategies, and diagnostic technology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:599.e1-599.e12.

4. Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T, et al. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part II Screening, education, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:611.e1-611.e10.

5. Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, et al. Use of and intentions to use dermoscopy among physicians in the United States. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:2.

6. Salerni G, Terán T, Alonso C, et al. The role of dermoscopy and digital dermoscopy follow-up in the clinical diagnosis of melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features of 99 consecutive primary melanomas. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:39-46.

7. Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

8. Westerhoff K, McCarthy WH, Menzies SW. Increase in the sensitivity for melanoma diagnosis by primary care physicians using skin surface microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1016-1020.

9. Menzies SW, Emery J, Staples M, et al. Impact of dermoscopy and short-term sequential digital dermoscopy imaging for the management of pigmented lesions in primary care: a sequential intervention trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1270-1277.

10. Kittler H. Dermatoscopy: introduction of a new algorithmic method based on pattern analysis for diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions. Dermatopathology: Practical & Conceptual. 2007;13:3.

11. Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, et al. Standardization of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1093-1106.

12. Stolz W, Riemann A, Cognetta AB, et al. ABCD rule of dermoscopy: a new practical method for early recognition of malignant melanoma. Eur J Dermatol. 1994;4:521-527.

13. Pehamberger H, Steiner A, Wolff K. In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions I Pattern analysis of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:571-583.

14. Menzies SW, Ingvar C, McCarthy WH. A sensitivity and specificity analysis of the surface microscopy features of invasive melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1996;6:55-62.

15. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, et al. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. Comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1563-1570.

16. Henning JS, Dusza SW, Wang SQ, et al. The CASH (color, architecture, symmetry, and homogeneity) algorithm for dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:45-52.

17. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, et al. Three-point checklist of dermoscopy. A new screening method for early detection of melanoma. Dermatology. 2004;208:27-31.

18. Lallas A, Moscarella E, Longo C, et al. Likelihood of finding melanoma when removing a Spitzoid-looking lesion in patients aged 12 years or older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:47-53.

19. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

Persistent rash on feet

A 49-year-old Hispanic woman presented with a 4-month history of scaling and a macerated rash localized between her toes (FIGURE 1). The rash was malodorous, mildly erythematous, and sometimes associated with pruritus. The patient had no relevant medical history. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing was performed and found to be negative. So a Wood’s lamp was used to examine the patient’s toes—and it revealed the diagnosis.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythrasma

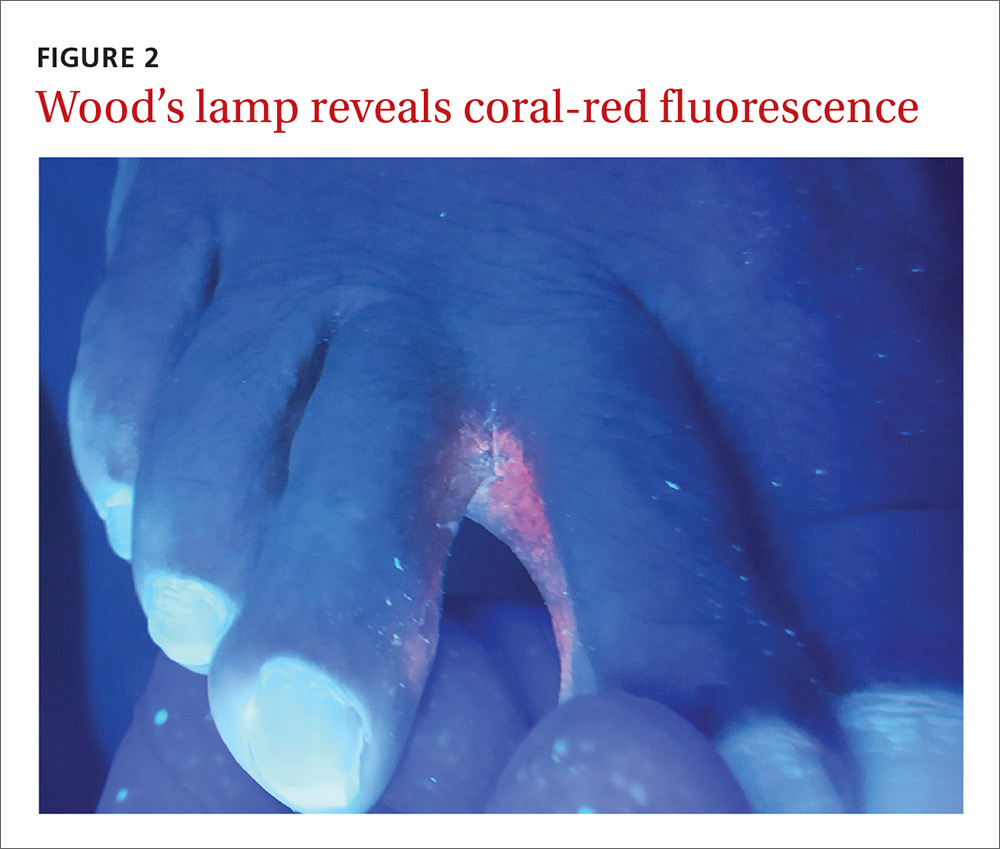

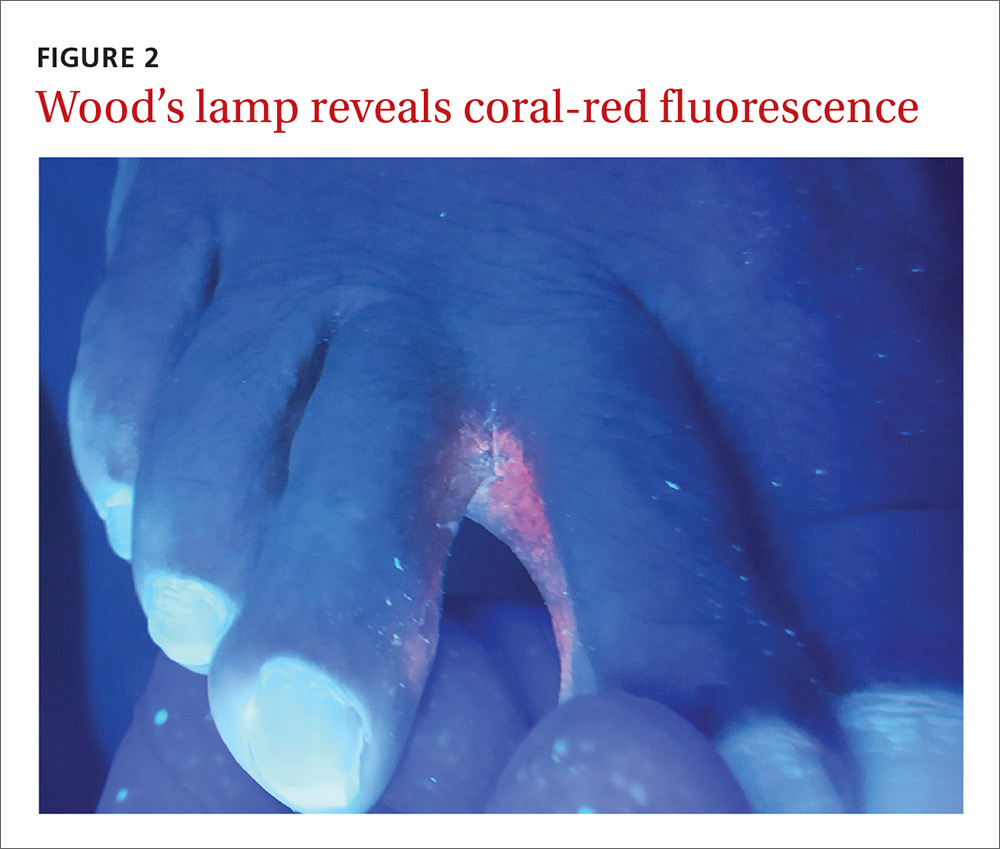

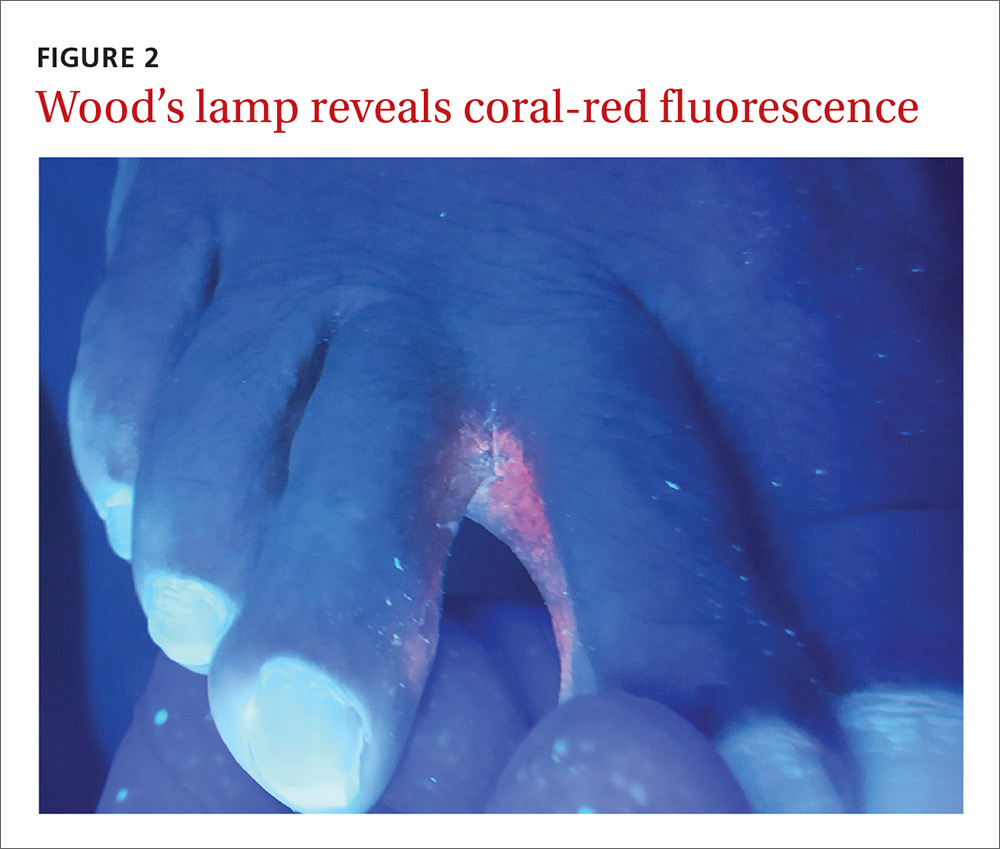

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 2), which led us to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.1,2

Interdigital erythrasma is more common than previously thought; in one study of 151 patients with erythrasma, the most common site was the toe webs (64.9%), followed by the inguinal region (17.9%), the axillary region (14.6%), and the inframammary region (2.6%).2 Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state.3

Differential includes “athlete’s foot”

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes:

Tinea pedis. Erythrasma is often mistaken for tinea pedis, because both conditions cause scaling between the toes. A Wood’s lamp exam can quickly differentiate between the 2,1 as tinea pedis does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light.

Contact dermatitis mimics many conditions, but a negative Wood’s lamp exam and history of worsening with contact to specific substances helps to make this diagnosis.

Prevention and Tx hinge on good hygiene, topical agents

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%.4 Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice.4,5 It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea, because it can treat both conditions. This is not uncommon in the interdigital spaces between the toes and in the groin.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks can also be used to treat the condition.3,6 However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics,6 clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred.2,6

Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Polat M, lhan MN. The prevalence of interdigital erythrasma: a prospective study from an outpatient clinic in Turkey. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:121-124.

2. Avci O, Tanyildizi T, Kusku E. A comparison between the effectiveness of erythromycin, single-dose clarithromycin and topical fusidic acid in the treatment of erythrasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:70-74.

3. Kibbi AG, Sleiman M. Erythrasma. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052532-overview#a0199. Accessed December 10, 2016.

4. Pitcher DG, Noble WC, Seville RH. Treatment of erythrasma with miconazole. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:453-456.

5. Clayton YM, Knight AG. A clinical double-blind trial of topical miconazole and clotrimazole against superficial fungal infections and erythrasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1:225-232.

6. Holdiness MR. Management of cutaneous erythrasma. Drugs. 2002;62:1131-1141.

A 49-year-old Hispanic woman presented with a 4-month history of scaling and a macerated rash localized between her toes (FIGURE 1). The rash was malodorous, mildly erythematous, and sometimes associated with pruritus. The patient had no relevant medical history. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing was performed and found to be negative. So a Wood’s lamp was used to examine the patient’s toes—and it revealed the diagnosis.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythrasma

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 2), which led us to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.1,2

Interdigital erythrasma is more common than previously thought; in one study of 151 patients with erythrasma, the most common site was the toe webs (64.9%), followed by the inguinal region (17.9%), the axillary region (14.6%), and the inframammary region (2.6%).2 Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state.3

Differential includes “athlete’s foot”

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes:

Tinea pedis. Erythrasma is often mistaken for tinea pedis, because both conditions cause scaling between the toes. A Wood’s lamp exam can quickly differentiate between the 2,1 as tinea pedis does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light.

Contact dermatitis mimics many conditions, but a negative Wood’s lamp exam and history of worsening with contact to specific substances helps to make this diagnosis.

Prevention and Tx hinge on good hygiene, topical agents

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%.4 Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice.4,5 It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea, because it can treat both conditions. This is not uncommon in the interdigital spaces between the toes and in the groin.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks can also be used to treat the condition.3,6 However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics,6 clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred.2,6

Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

A 49-year-old Hispanic woman presented with a 4-month history of scaling and a macerated rash localized between her toes (FIGURE 1). The rash was malodorous, mildly erythematous, and sometimes associated with pruritus. The patient had no relevant medical history. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing was performed and found to be negative. So a Wood’s lamp was used to examine the patient’s toes—and it revealed the diagnosis.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythrasma

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 2), which led us to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.1,2

Interdigital erythrasma is more common than previously thought; in one study of 151 patients with erythrasma, the most common site was the toe webs (64.9%), followed by the inguinal region (17.9%), the axillary region (14.6%), and the inframammary region (2.6%).2 Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state.3

Differential includes “athlete’s foot”

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes:

Tinea pedis. Erythrasma is often mistaken for tinea pedis, because both conditions cause scaling between the toes. A Wood’s lamp exam can quickly differentiate between the 2,1 as tinea pedis does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light.

Contact dermatitis mimics many conditions, but a negative Wood’s lamp exam and history of worsening with contact to specific substances helps to make this diagnosis.

Prevention and Tx hinge on good hygiene, topical agents

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%.4 Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice.4,5 It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea, because it can treat both conditions. This is not uncommon in the interdigital spaces between the toes and in the groin.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks can also be used to treat the condition.3,6 However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics,6 clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred.2,6

Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Polat M, lhan MN. The prevalence of interdigital erythrasma: a prospective study from an outpatient clinic in Turkey. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:121-124.

2. Avci O, Tanyildizi T, Kusku E. A comparison between the effectiveness of erythromycin, single-dose clarithromycin and topical fusidic acid in the treatment of erythrasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:70-74.

3. Kibbi AG, Sleiman M. Erythrasma. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052532-overview#a0199. Accessed December 10, 2016.

4. Pitcher DG, Noble WC, Seville RH. Treatment of erythrasma with miconazole. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:453-456.

5. Clayton YM, Knight AG. A clinical double-blind trial of topical miconazole and clotrimazole against superficial fungal infections and erythrasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1:225-232.

6. Holdiness MR. Management of cutaneous erythrasma. Drugs. 2002;62:1131-1141.

1. Polat M, lhan MN. The prevalence of interdigital erythrasma: a prospective study from an outpatient clinic in Turkey. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:121-124.

2. Avci O, Tanyildizi T, Kusku E. A comparison between the effectiveness of erythromycin, single-dose clarithromycin and topical fusidic acid in the treatment of erythrasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:70-74.

3. Kibbi AG, Sleiman M. Erythrasma. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052532-overview#a0199. Accessed December 10, 2016.

4. Pitcher DG, Noble WC, Seville RH. Treatment of erythrasma with miconazole. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:453-456.

5. Clayton YM, Knight AG. A clinical double-blind trial of topical miconazole and clotrimazole against superficial fungal infections and erythrasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1:225-232.

6. Holdiness MR. Management of cutaneous erythrasma. Drugs. 2002;62:1131-1141.

Rash on eyebrows and periumbilical region

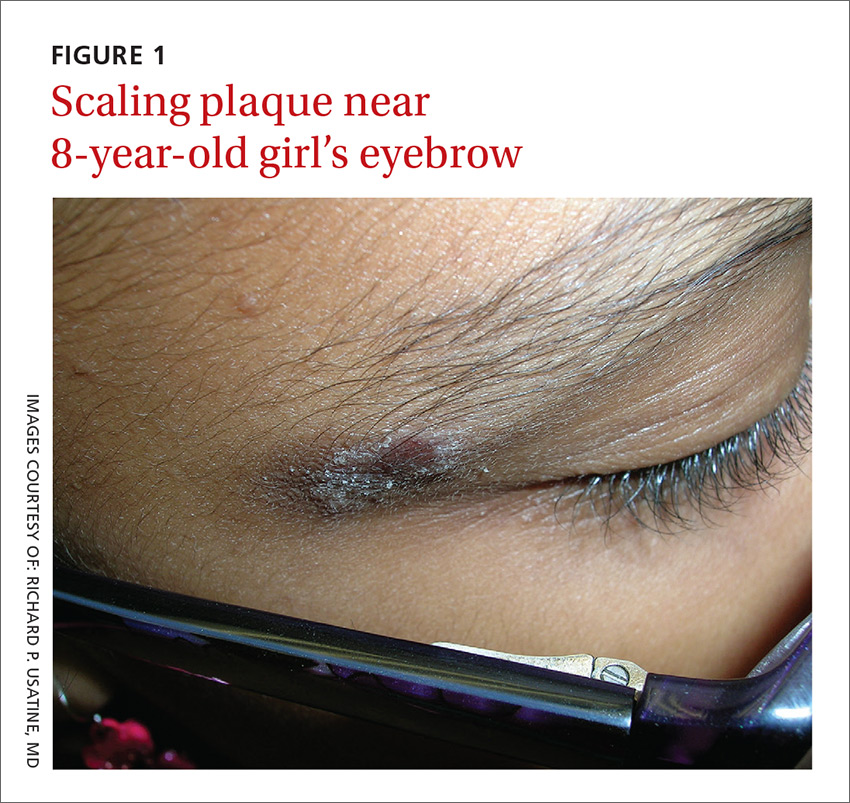

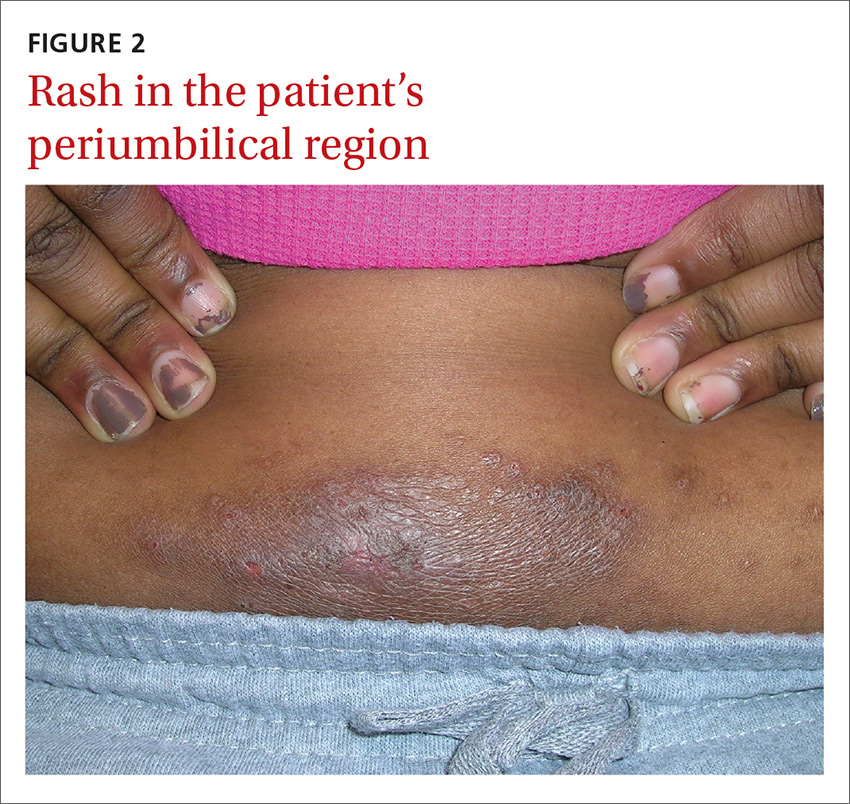

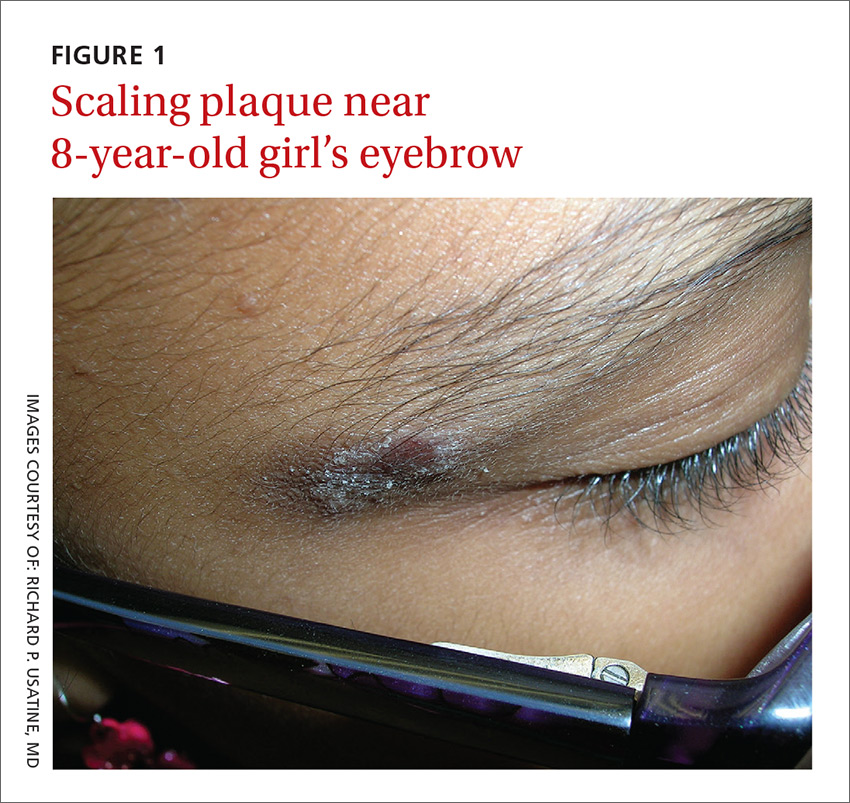

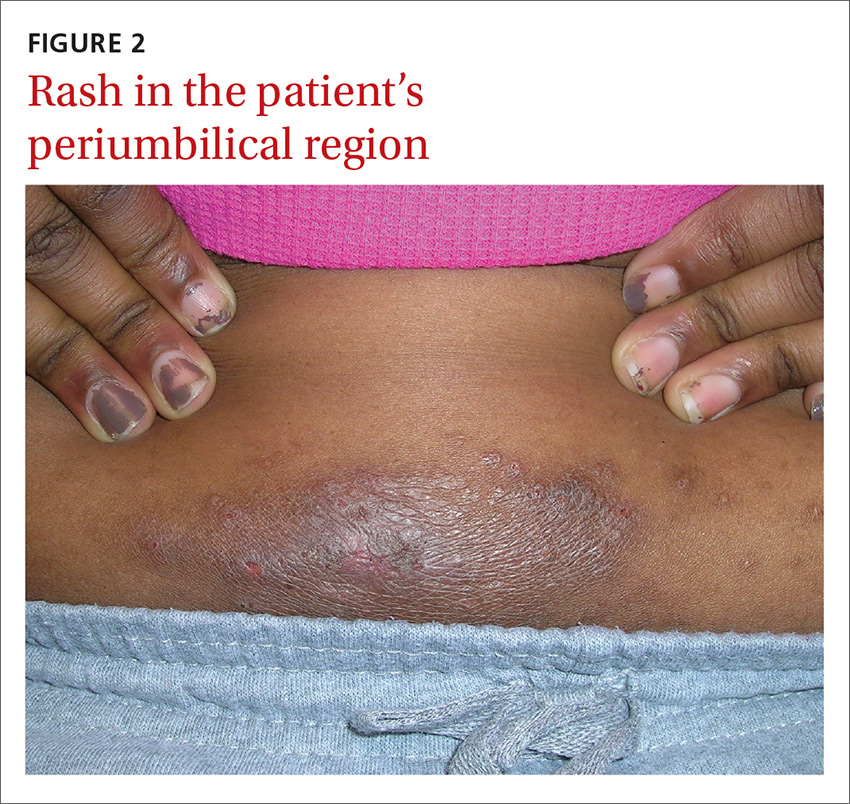

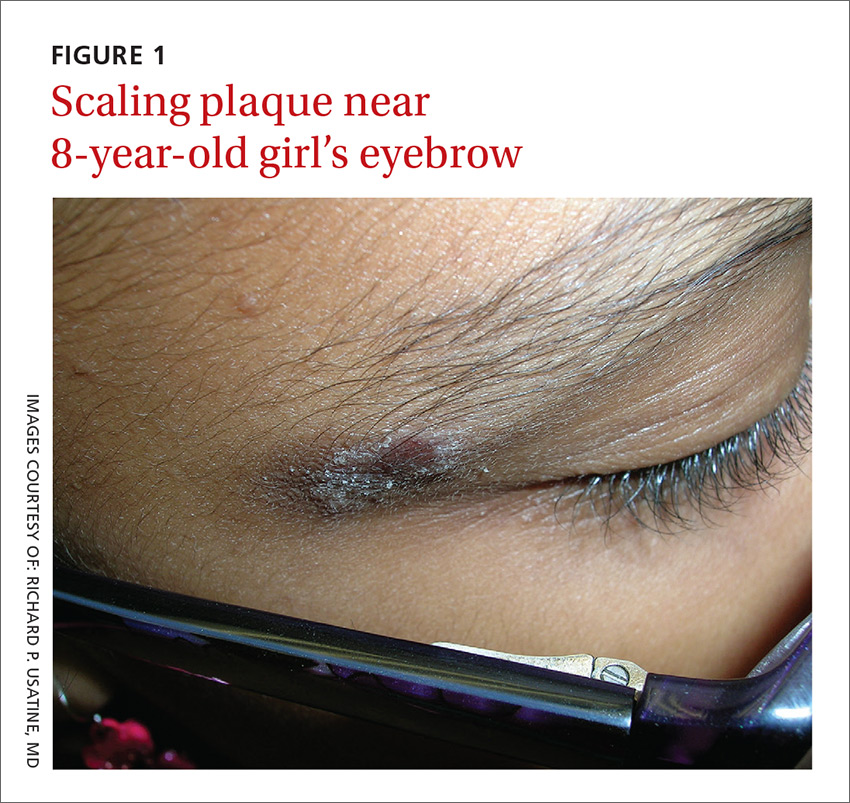

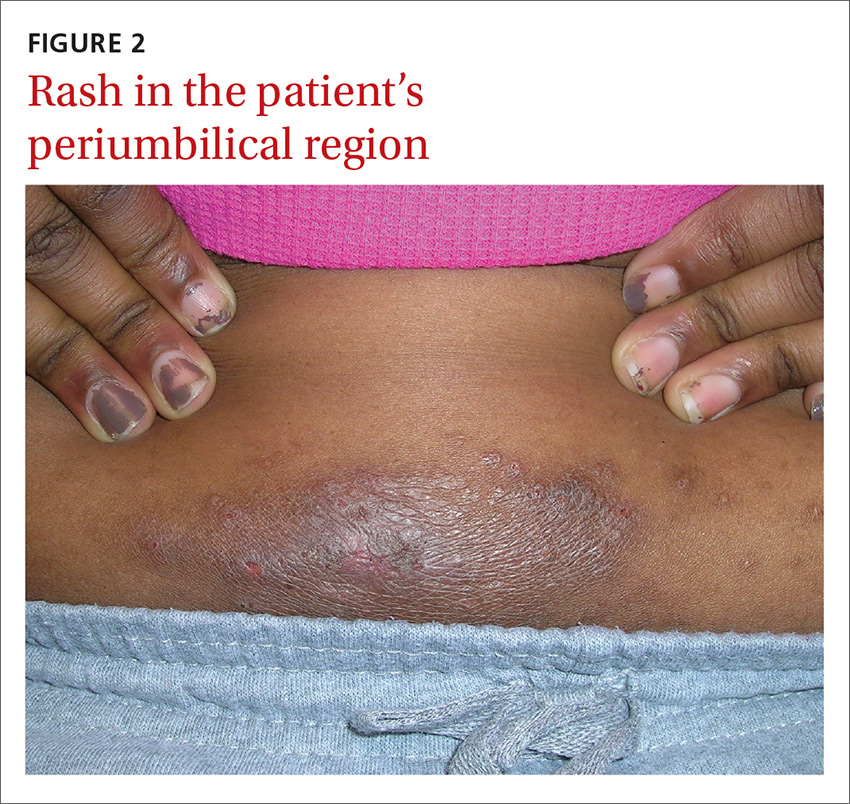

An 8-year-old girl was brought to her family physician’s office (RU) because of a persistent rash on her lateral eyebrows and periumbilical region. The family indicated that she’d had the rash for more than 6 months. They also mentioned that the child had received a new pair of eyeglasses 8 months earlier. The child was otherwise in good health. The physical examination revealed erythematous scaling plaques near both lateral eyebrows and around the belly button (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?