User login

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

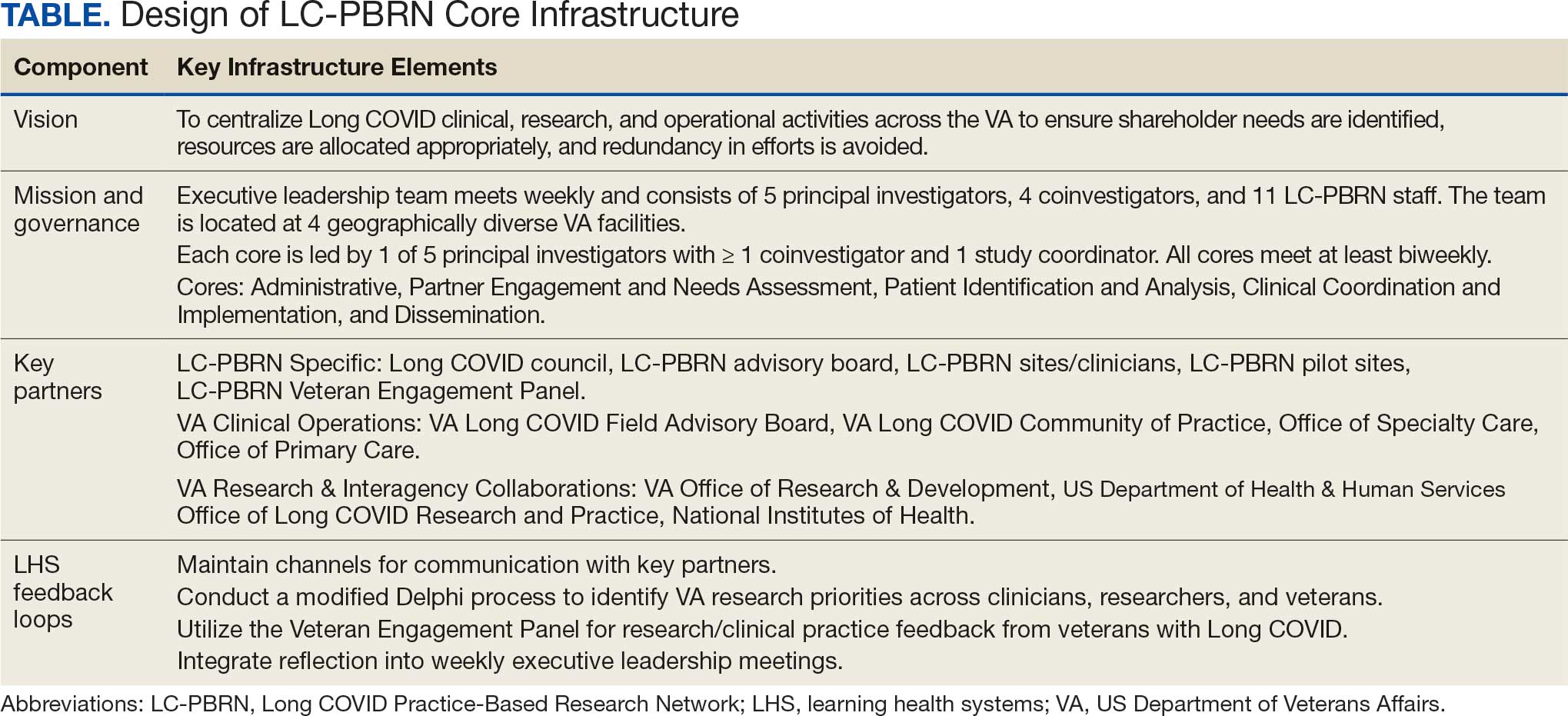

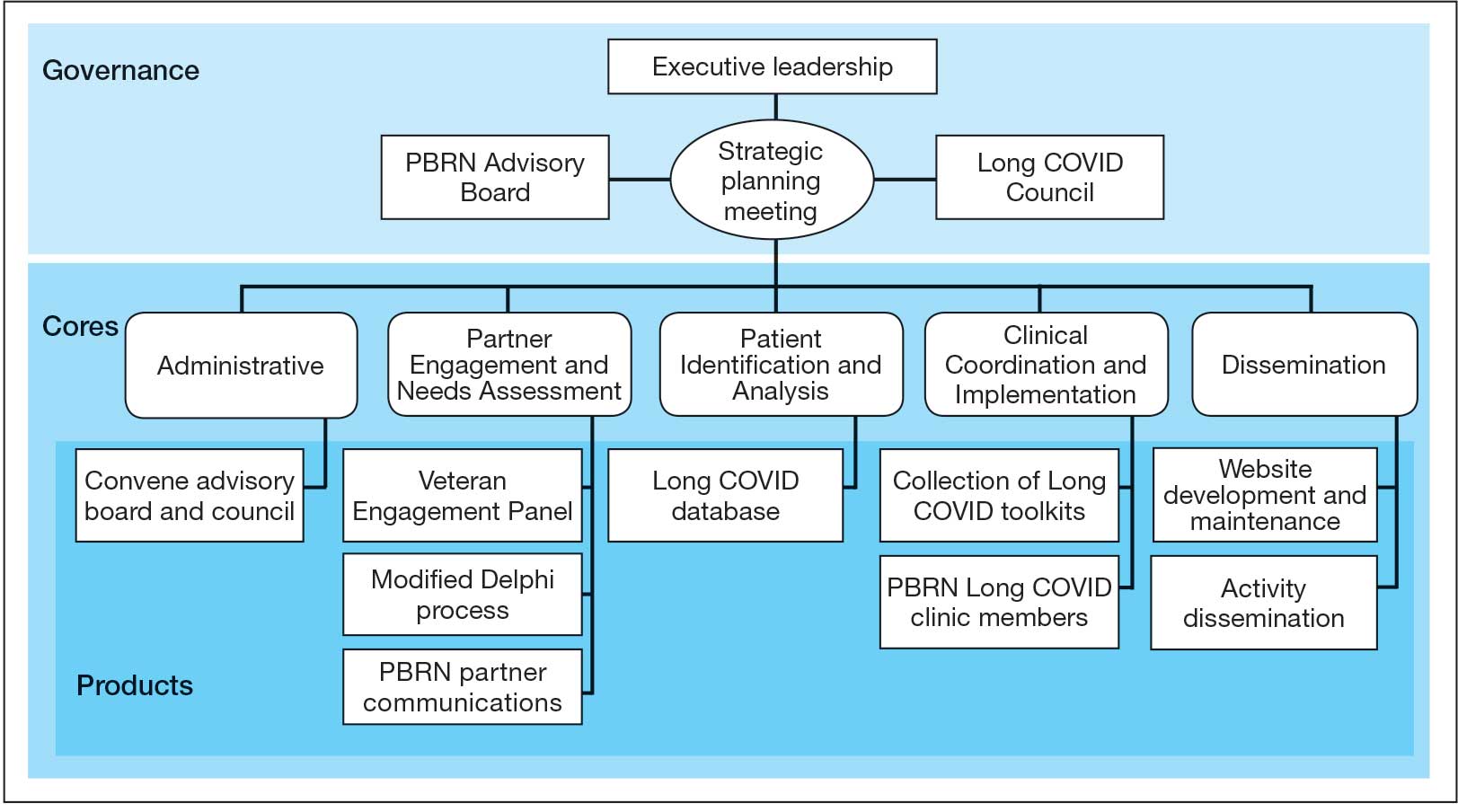

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

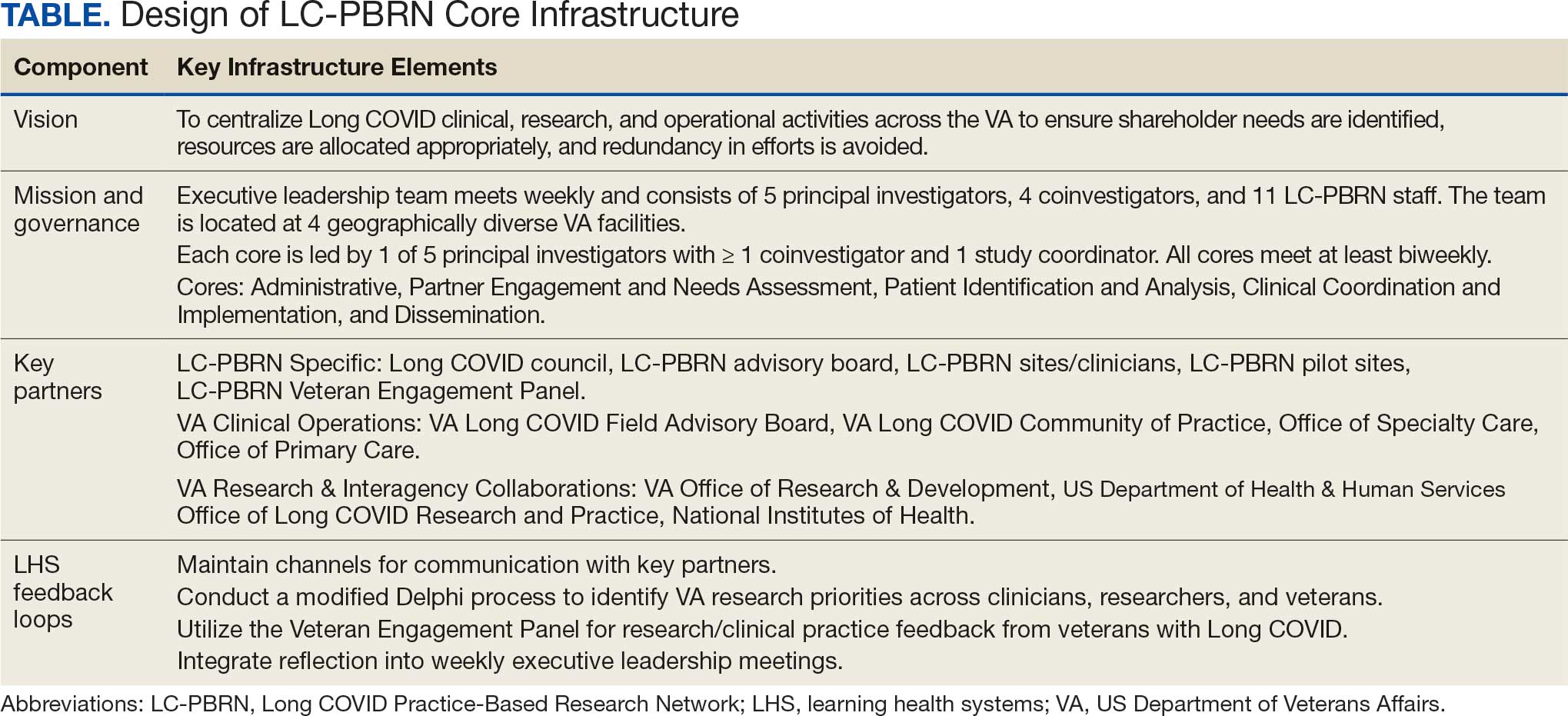

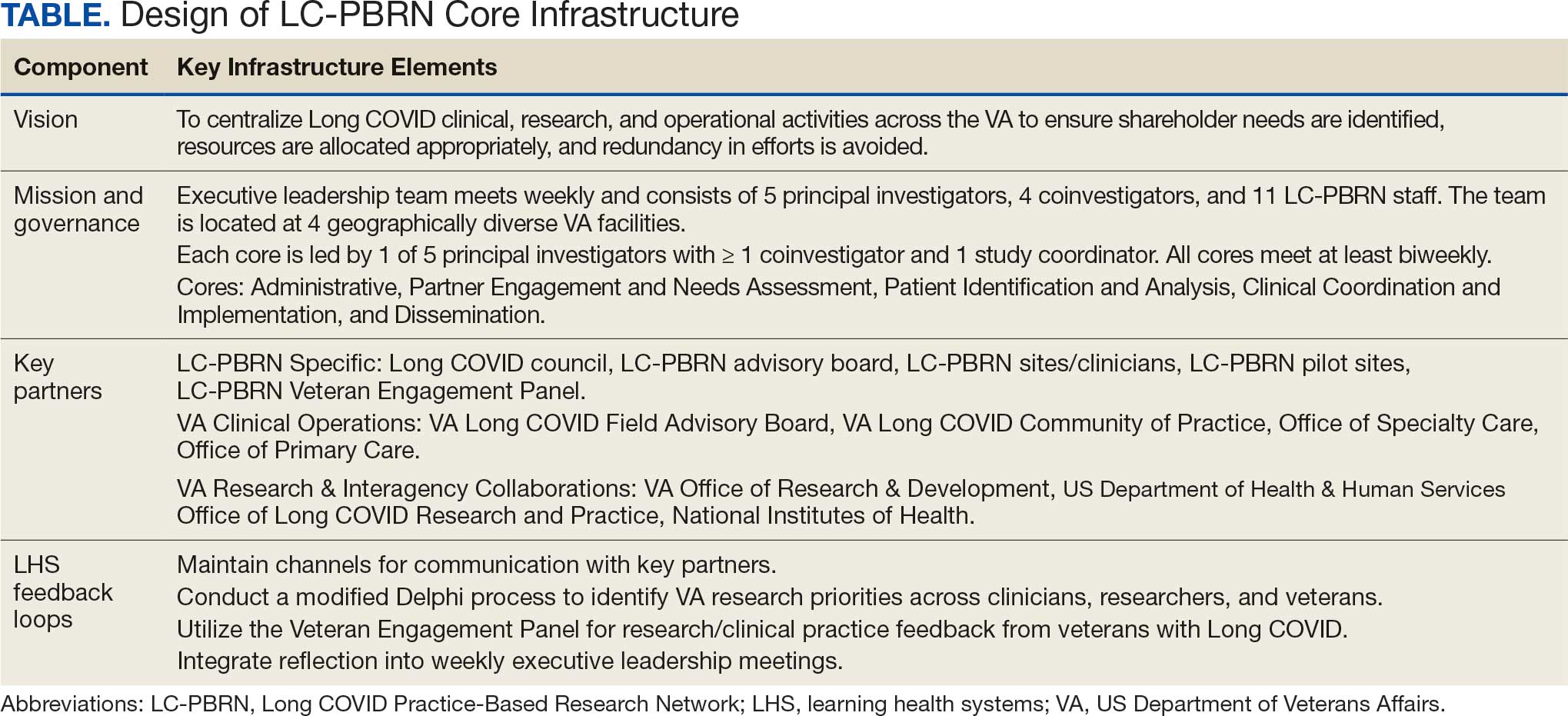

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

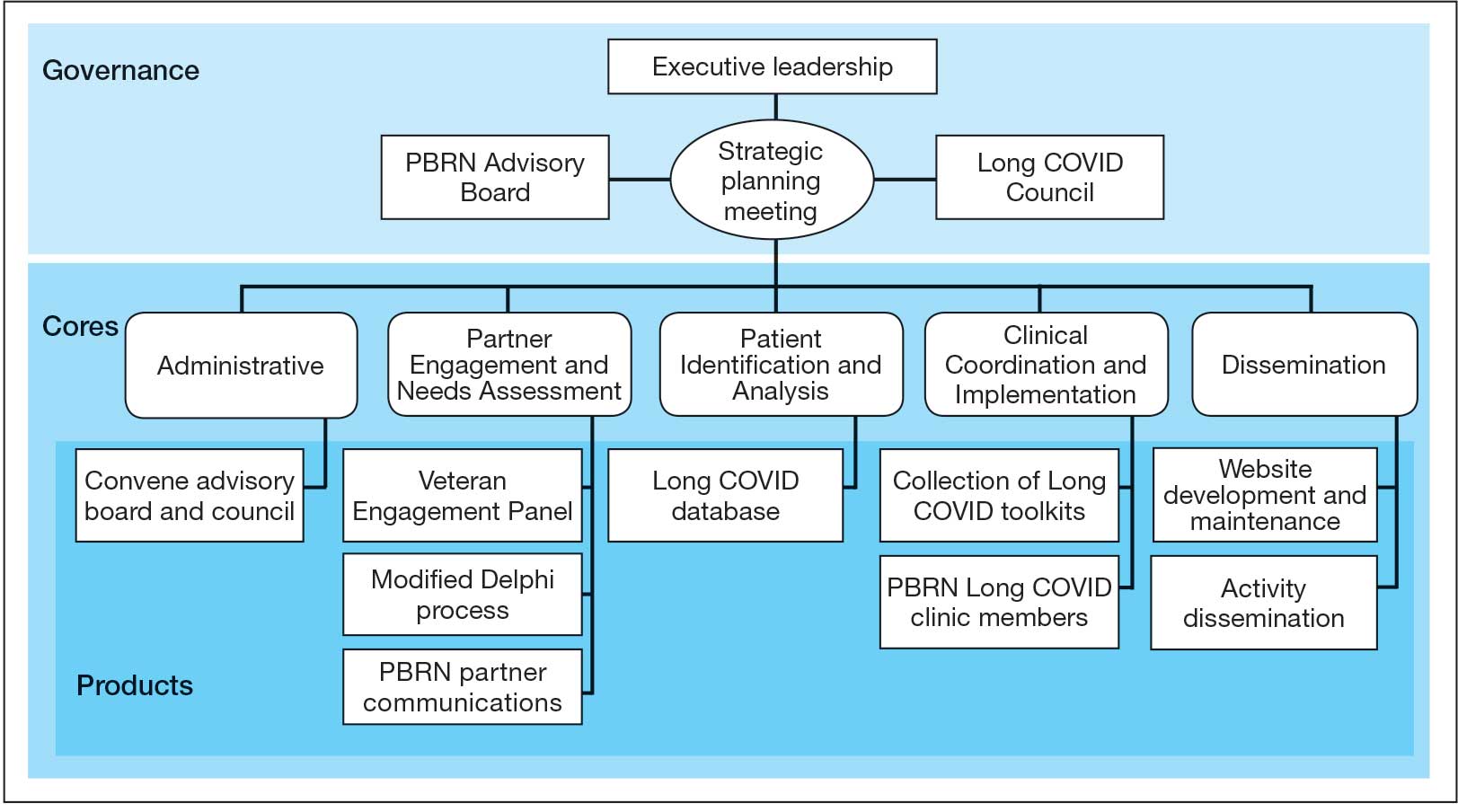

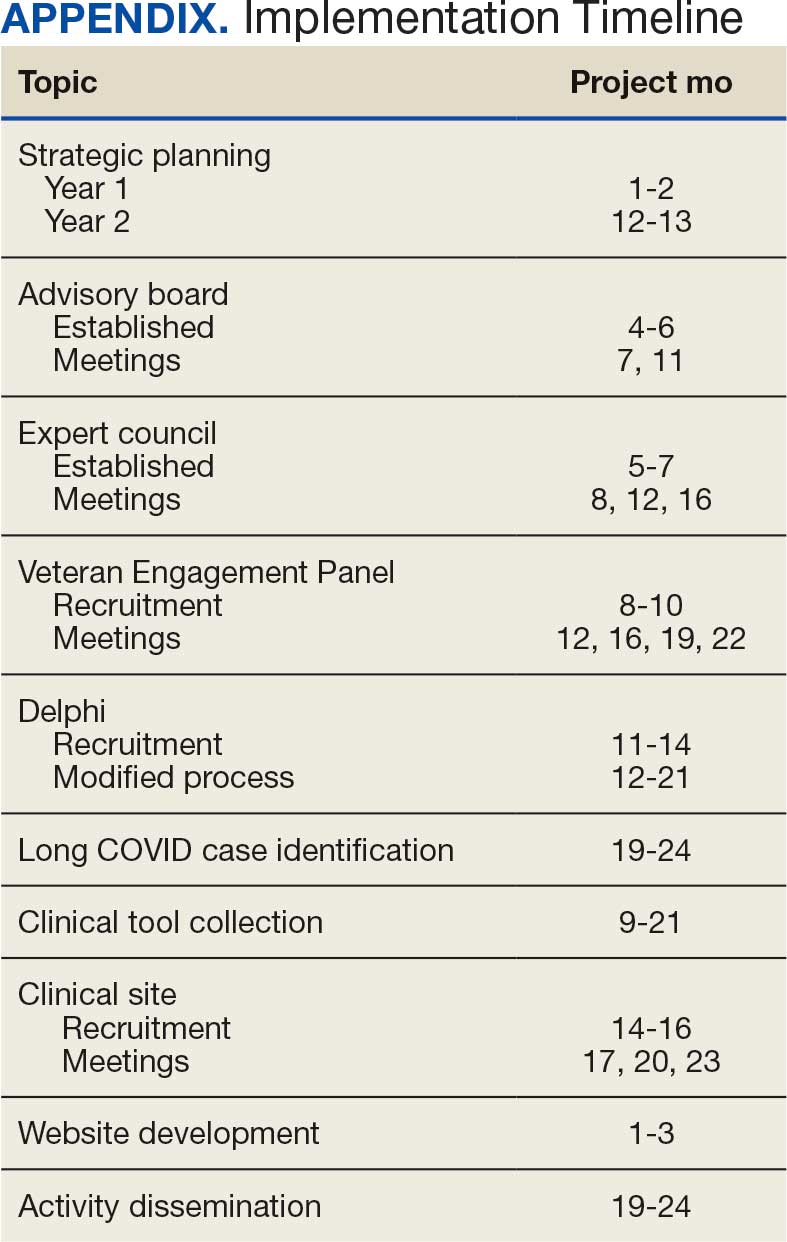

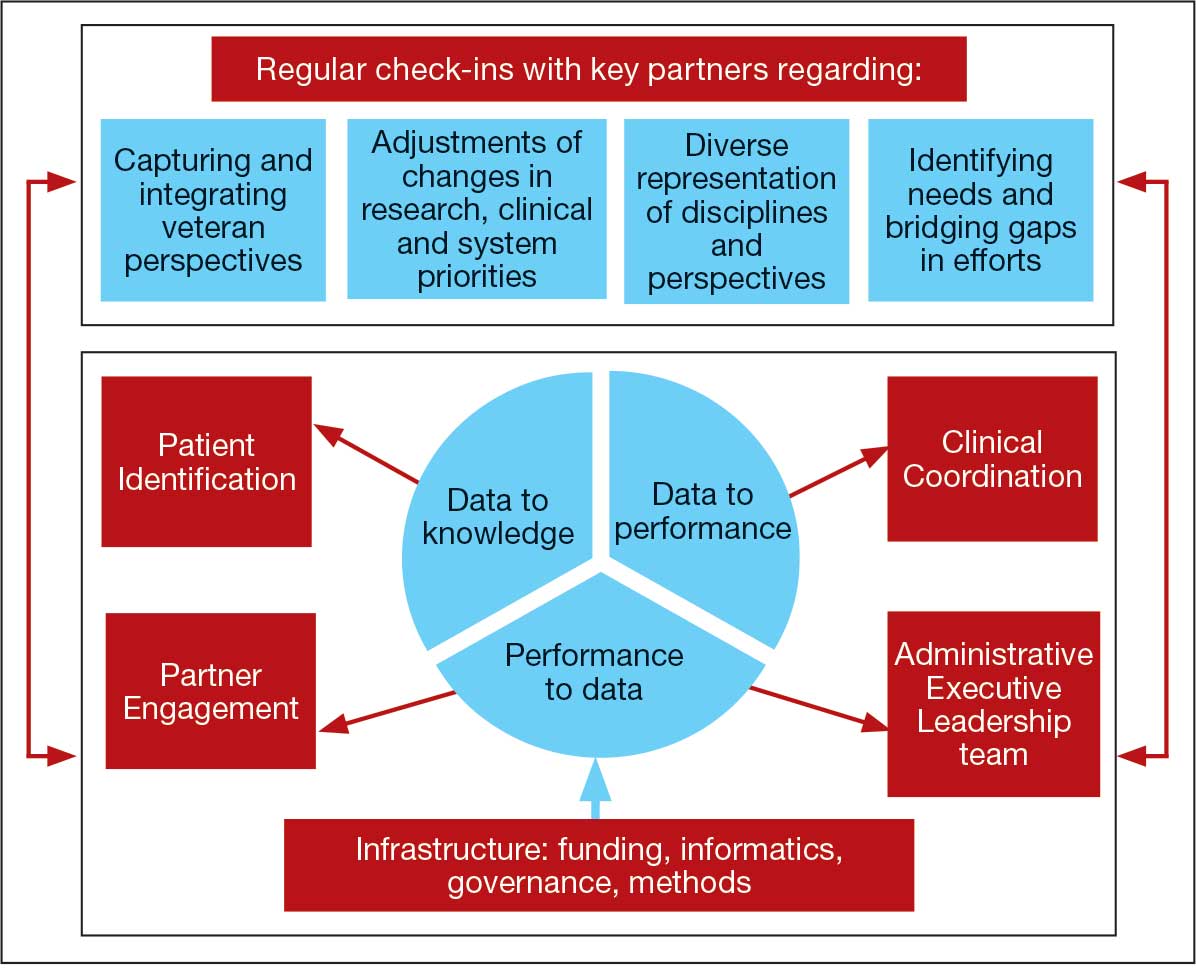

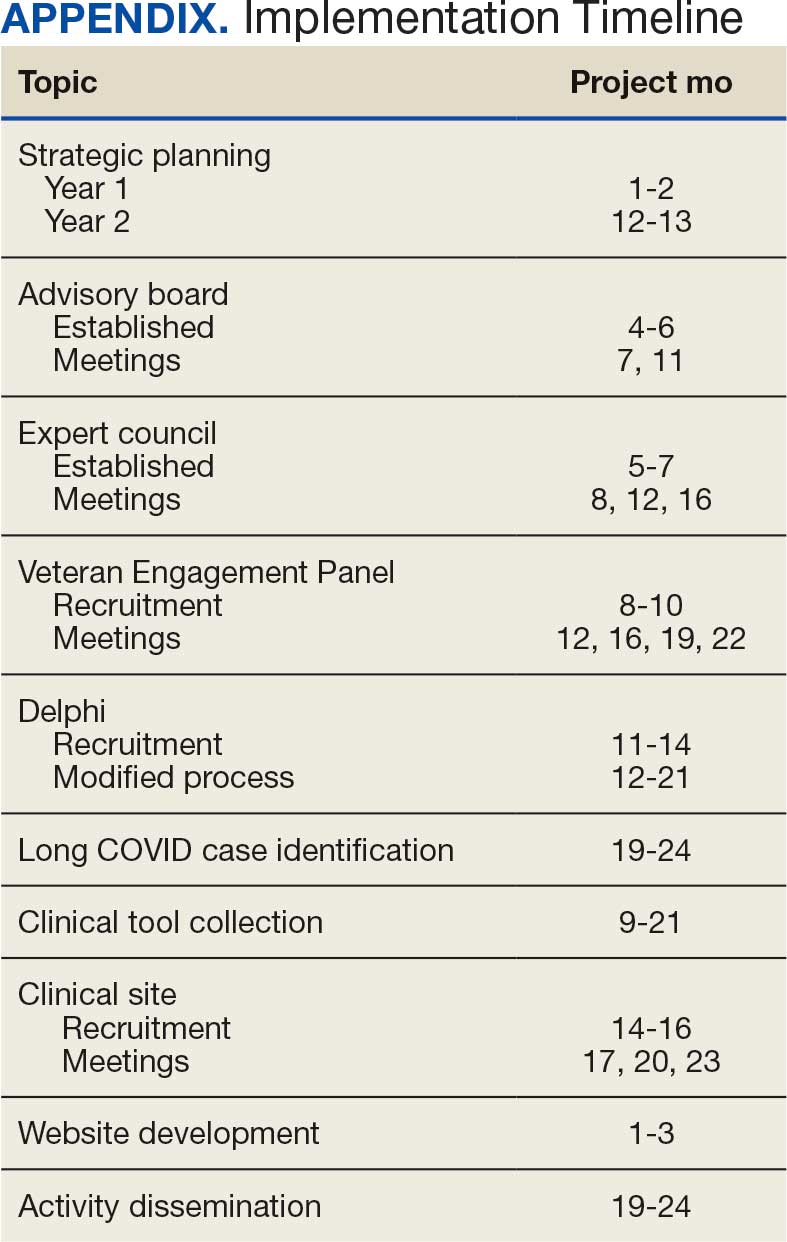

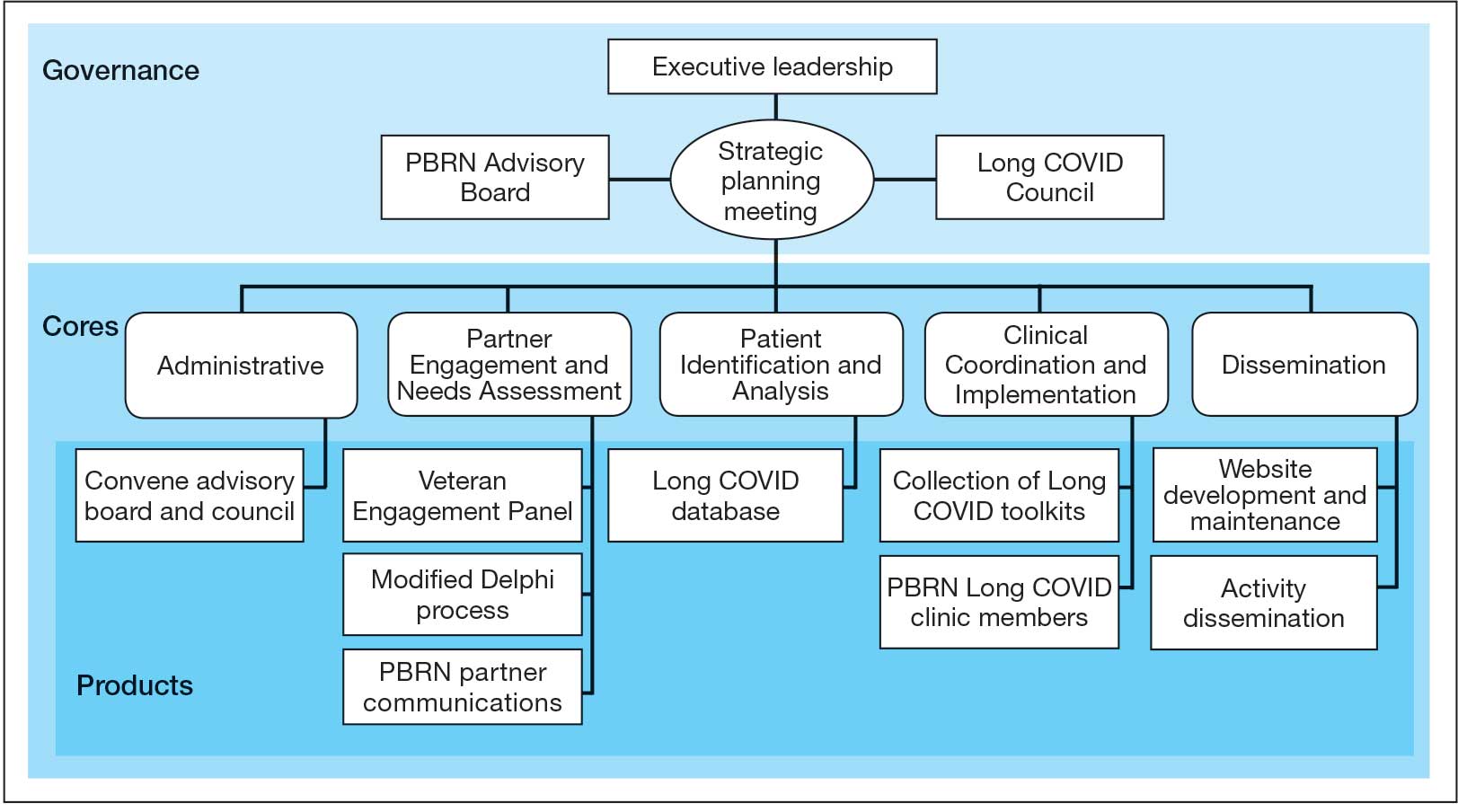

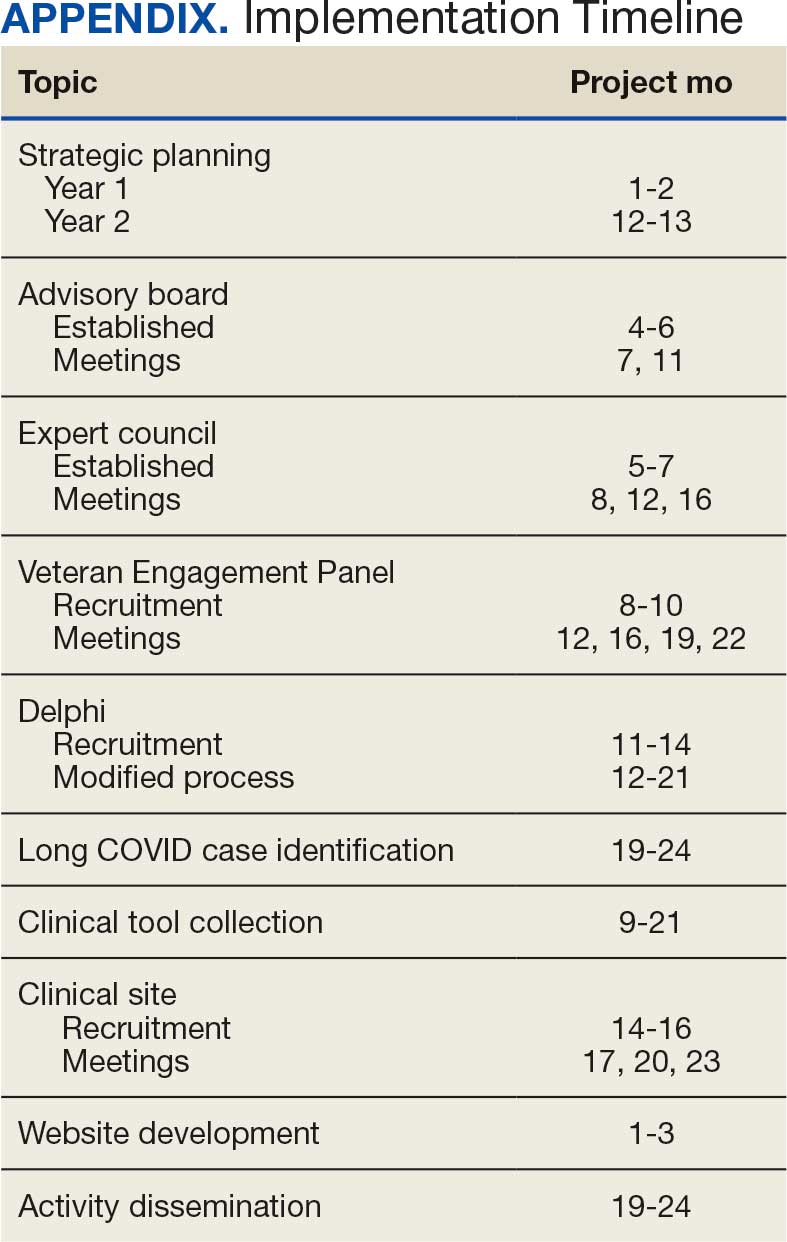

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

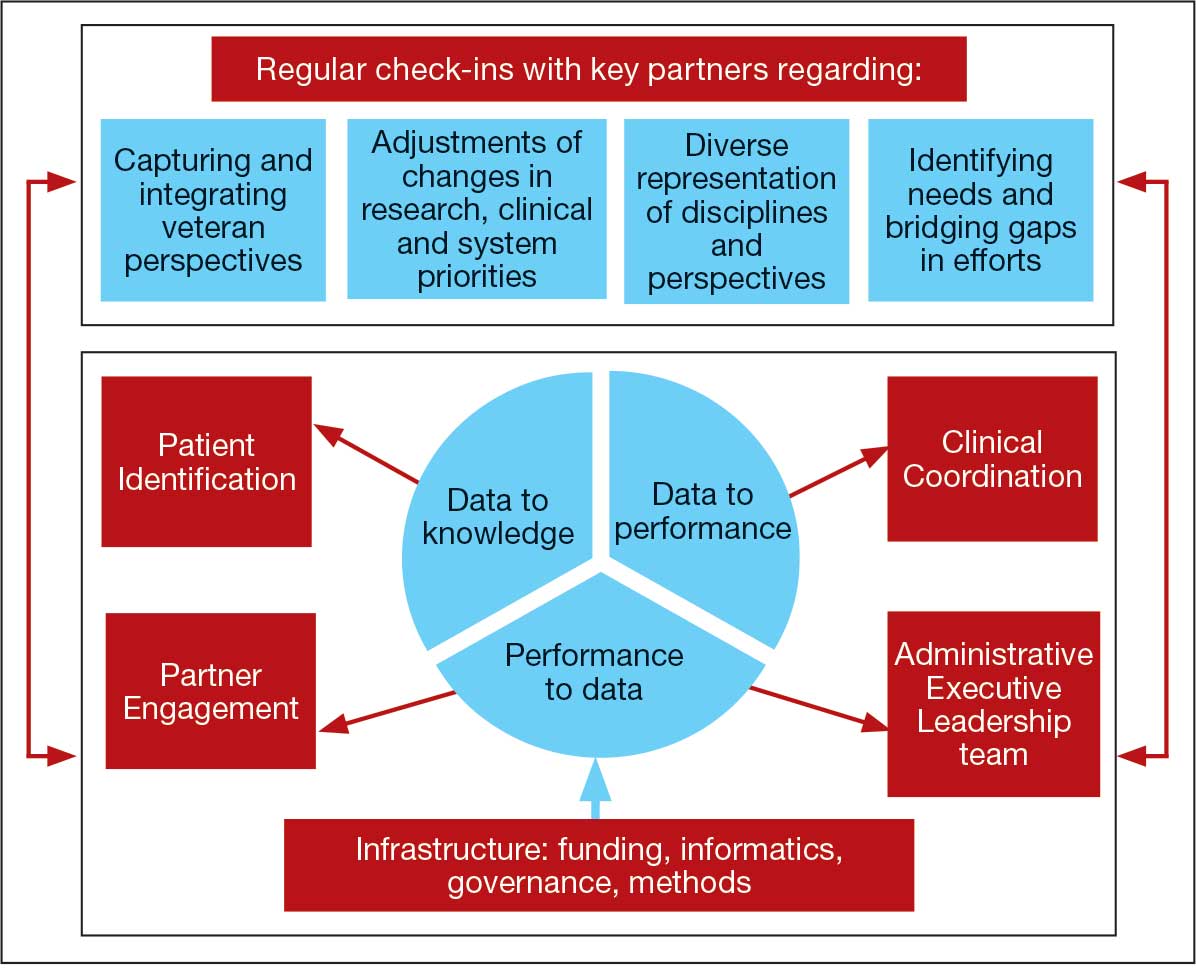

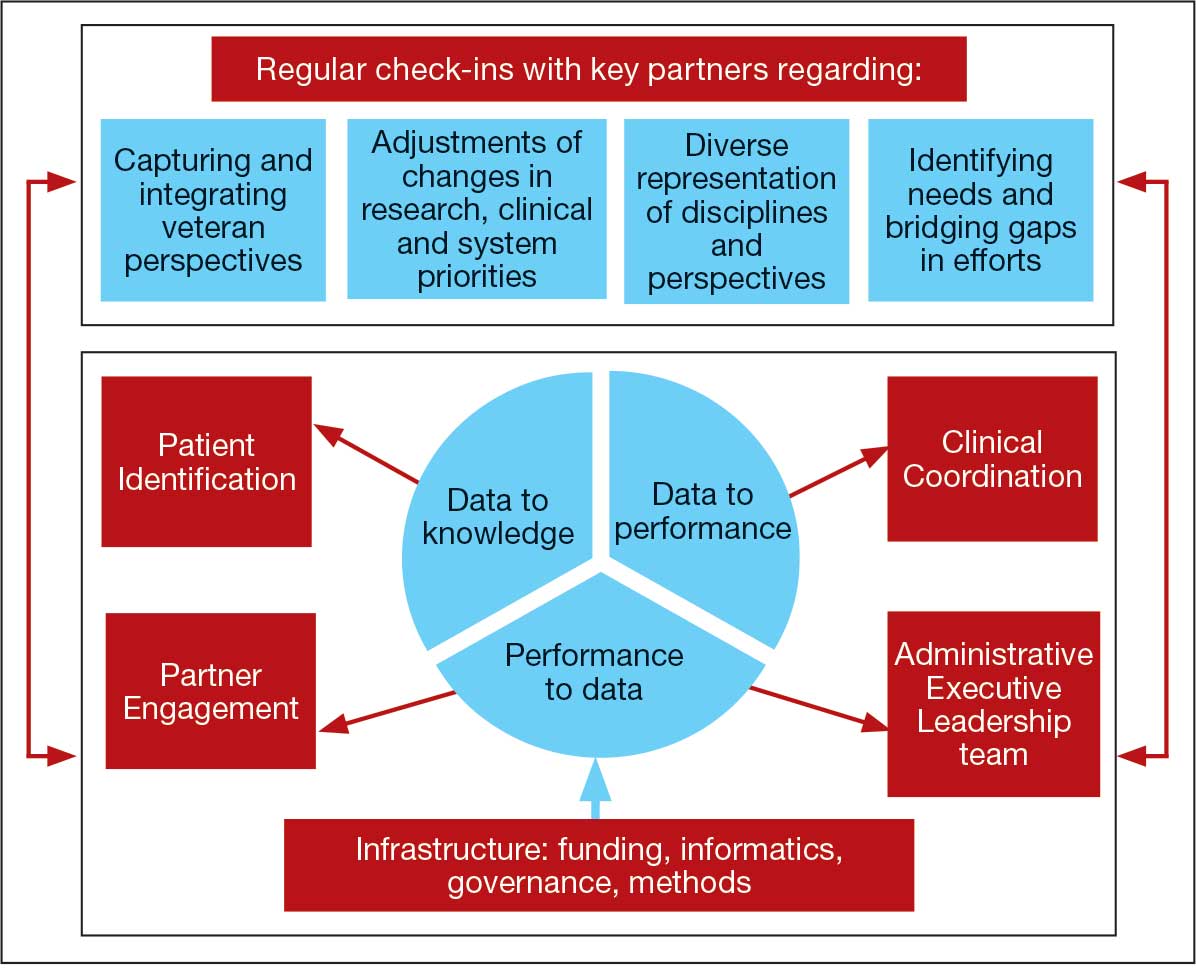

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at [email protected]) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at [email protected]) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at [email protected]) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Needs of Veterans With Personality Disorder Diagnoses in Community-Based Mental Health Care

Needs of Veterans With Personality Disorder Diagnoses in Community-Based Mental Health Care

Personality disorders (PDs) are enduring patterns of internal experience and behavior that differ from cultural norms and expectations, are inflexible and pervasive, have their onset in adolescence or early adulthood, and lead to distress or impairment. Ten PDs are included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition): paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, borderline, antisocial, histrionic, narcissistic, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive.1 These disorders impose a high burden on patients, families, health care systems, and broader economic systems.2,3 Up to 1 in 7 persons in the community and 50% of those receiving outpatient mental health treatment experience a PD.4,5 These conditions are associated with an increased risk of adverse events, including suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, homelessness, substance use, underemployment, relational issues, and high utilization of psychiatric services.6-9 PDs are routinely underassessed, underdocumented, and undertreated in clinical settings, and consistently receive less research funding than other, less prevalent forms of psychopathology. 10-12 As a result, there is limited understanding of clinical needs of individuals experiencing PDs.

MILITARY VETERANS WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS

Underacknowledgment of PDs and their associated difficulties may be especially pronounced in veteran populations. Due to longstanding etiological theories that implicate childhood trauma and adolescent onset in pathology development, PDs are traditionally considered pre-existing conditions or developmental abnormalities by the US Department of Defense and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a result, PDs are therefore deemed incompatible with military service and ineligible for service-connected disability benefits.13-15 Such determinations allowed PD pathology to be used as grounds for discharge for 26,000 service members from 2001 to 2007, or 2.6% of total enlisted discharges during that period.13,15,16

Despite this structural discrimination, recent research suggests veterans may be more likely to experience PD pathology than the general population.17 For example, a 2021 epidemiological survey in a community-based veteran sample found elevated rates of borderline, antisocial, and schizotypal PDs (6%-13%).6 In contrast, only 0.8% to 5.0% of veteran electronic health records (EHRs) have a documented PD diagnosis.8,18,19 Such elevations in PD pathology within veteran samples imply either a disproportionately high prevalence among enlistees (and therefore missed during recruitment procedures) or onset following military service, possibly due to exposure to traumatic events and/ or occupational stress.17 Due to the relative infancy of research in this area and a lack of longitudinal studies, etiology and course of illness for personality pathology in veterans remains largely unclear.

Structural underacknowledgment of PDs among military personnel has contributed to their underrepresentation in research on veteran populations. PD-focused research with veterans is rare, despite a rapid increase in broader empirical attention paid to these conditions in nonveteran samples.20 A recent meta-analysis of veterans with PDs identified 27 studies that included basic prevalence statistics. PDs were rarely a primary focus for these studies, and most were limited to veterans seen in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) settings.17 The literature also paints a bleak picture, suggesting veterans who experience PDs are at higher risk for suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, and homelessness. They also tend to experience more severe comorbid psychopathological symptoms and more often use high-intensity mental health services (eg, care within emergency departments or psychiatric inpatient settings) than veterans without PD pathology.6,8,18,19,21 However, PD pathology does not appear to impede the effectiveness of treatment for veterans.22-24 The implications of PD pathology on broader psychosocial functioning and health care needs certify a need for additional research that examines patterns of personality pathology, particularly in veterans outside the VHA.

METHODS

This study aims to enhance understanding of veterans affected by PDs and offer insight and guidance for treatment of these conditions in federal and nonfederal treatment settings. Previous research has been largely limited to VHA care-receiving samples; the longstanding stigma against PDs by the US military and VA may contribute to biased diagnosis and documentation of PDs in these settings. A large sample of veterans receiving community-based mental health care was therefore used to explore aims of the current study. This study specifically examined demographic patterns, diagnostic comorbidity, psychosocial outcomes, and treatment care settings among veterans with and without a PD diagnosis. Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized that veterans with a PD diagnosis would have more severe mental health comorbidities, poorer psychosocial outcomes, and receive care in higher intensity settings relative to veterans without a diagnosis.

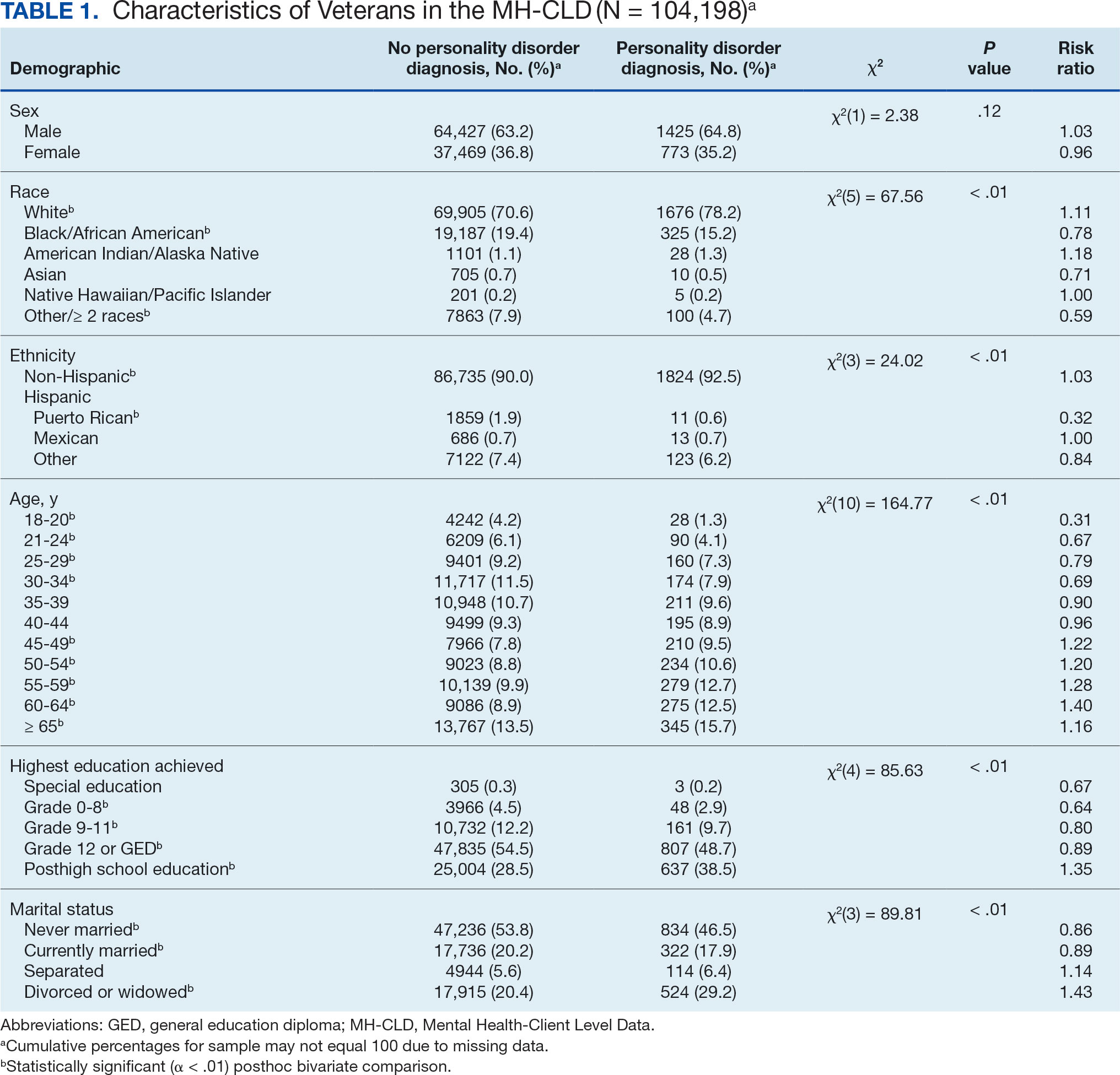

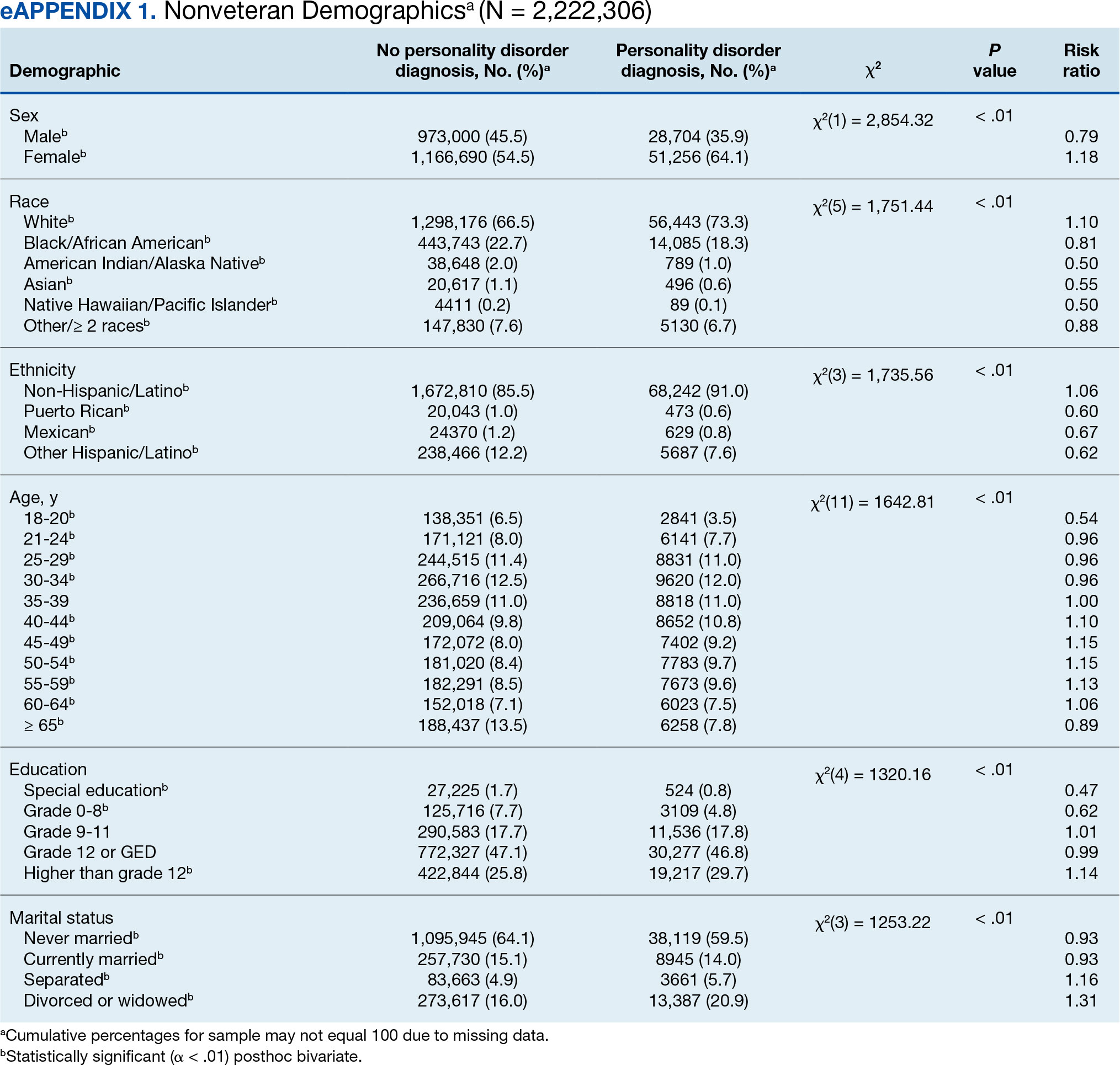

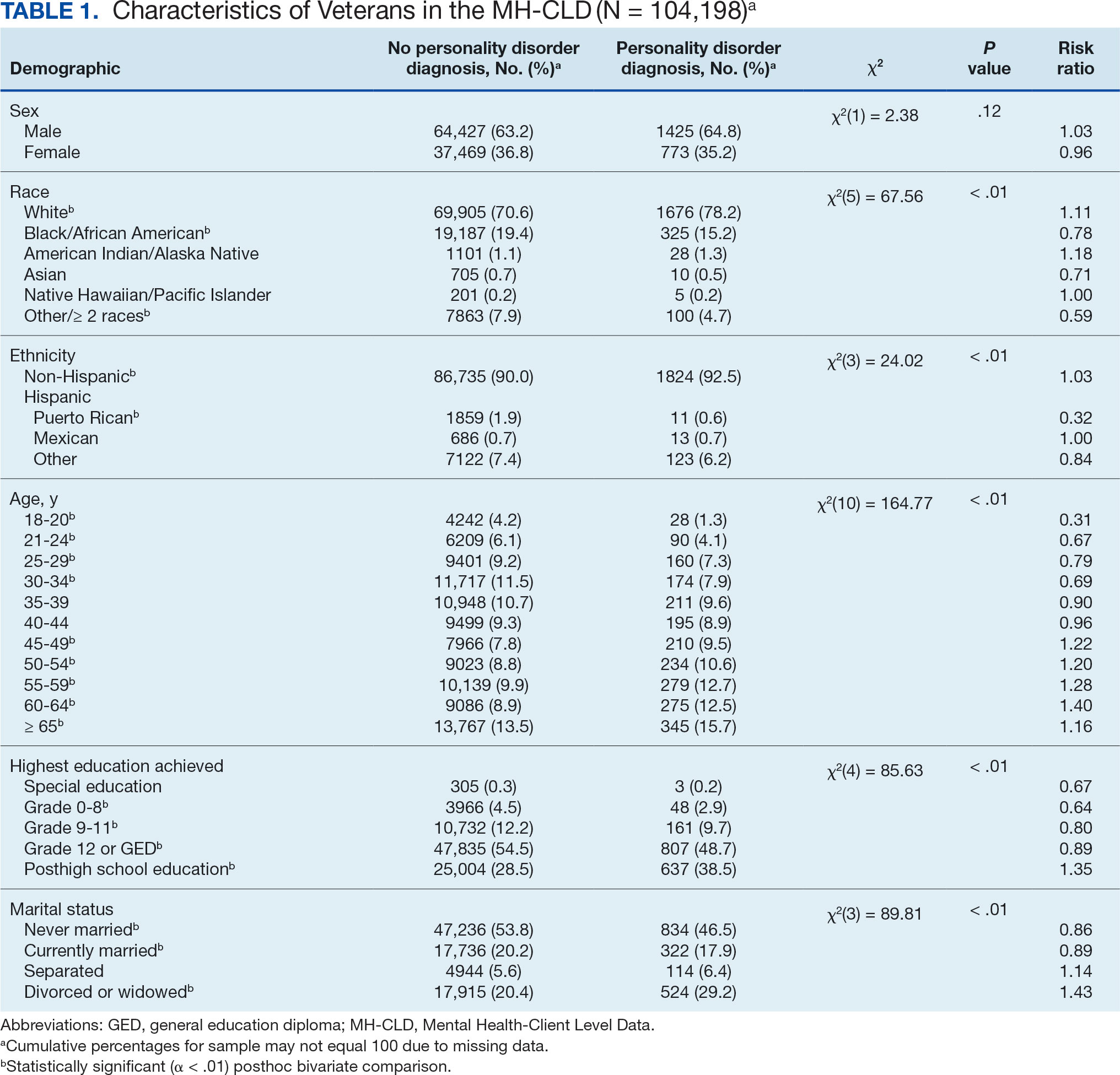

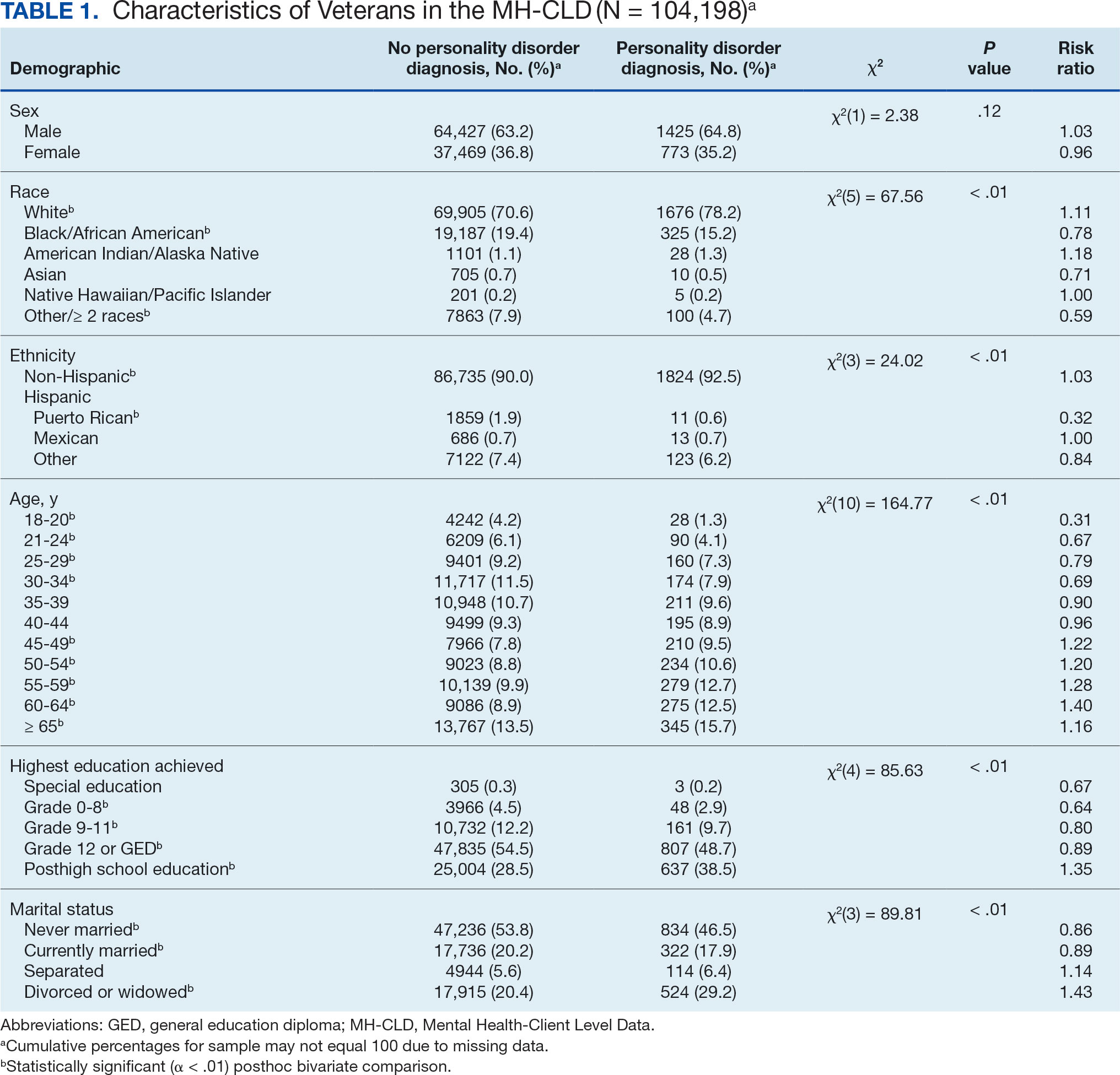

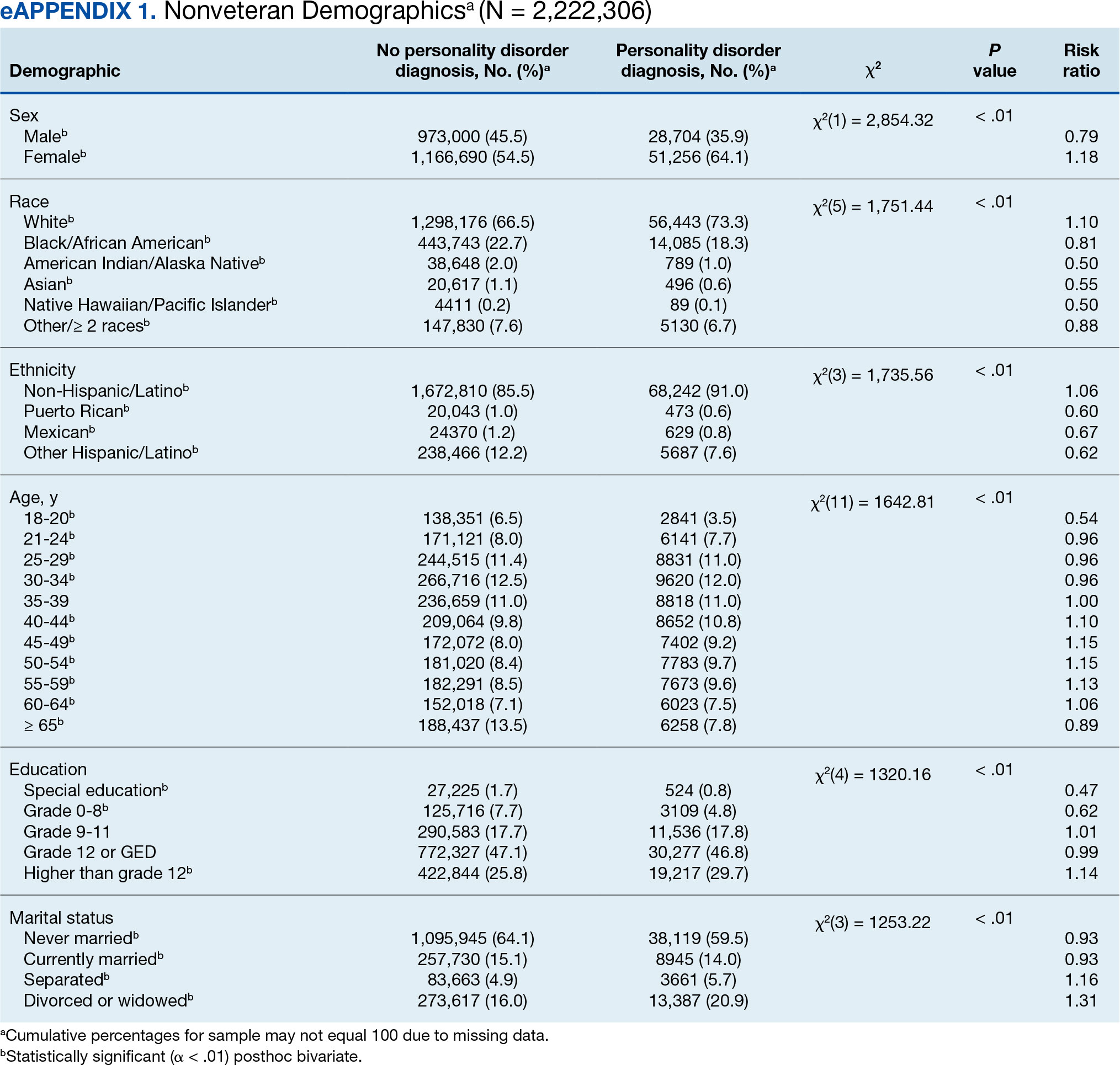

Data for the sample were drawn from the Mental Health Client-Level Data, a publicly available national dataset of nearly 7 million patients who received mental health treatment services provided or funded through state mental health agencies in 2022.25 The analytic sample included about 2.5 million patients for whom veteran status and data around the presence or absence of a PD diagnosis were available. Of these patients, 104,198 were identified as veterans. Veteran patients were identified as predominantly male (63%), White (71%), non-Hispanic (90%), and never married (54%).

Measures

The parent dataset included demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome information reported by treatment facilities to individual state administrative systems for each patient who received services. To protect patient privacy, only nonprotected health information is included, and efforts were made throughout compilation of the parent dataset to ensure patient privacy (eg, limiting detail of information disseminated for public access). Because the parent dataset does not include protected health information, studies using these data are considered exempt from institutional review board oversight.

Demographic information. This study reviewed veteran status, sex, race, ethnicity, age, education, and marital status. Veteran status was defined by whether the patient was aged ≥ 18 years and had previously served (but was not currently serving) in the military. Patients with a history of service in the National Guard or Military Reserves were only classified as veterans if they had been called or ordered to active duty while serving. Sex was operationalized dichotomously as male or female; no patients were identified as intersex, transgender, or other gender identities.

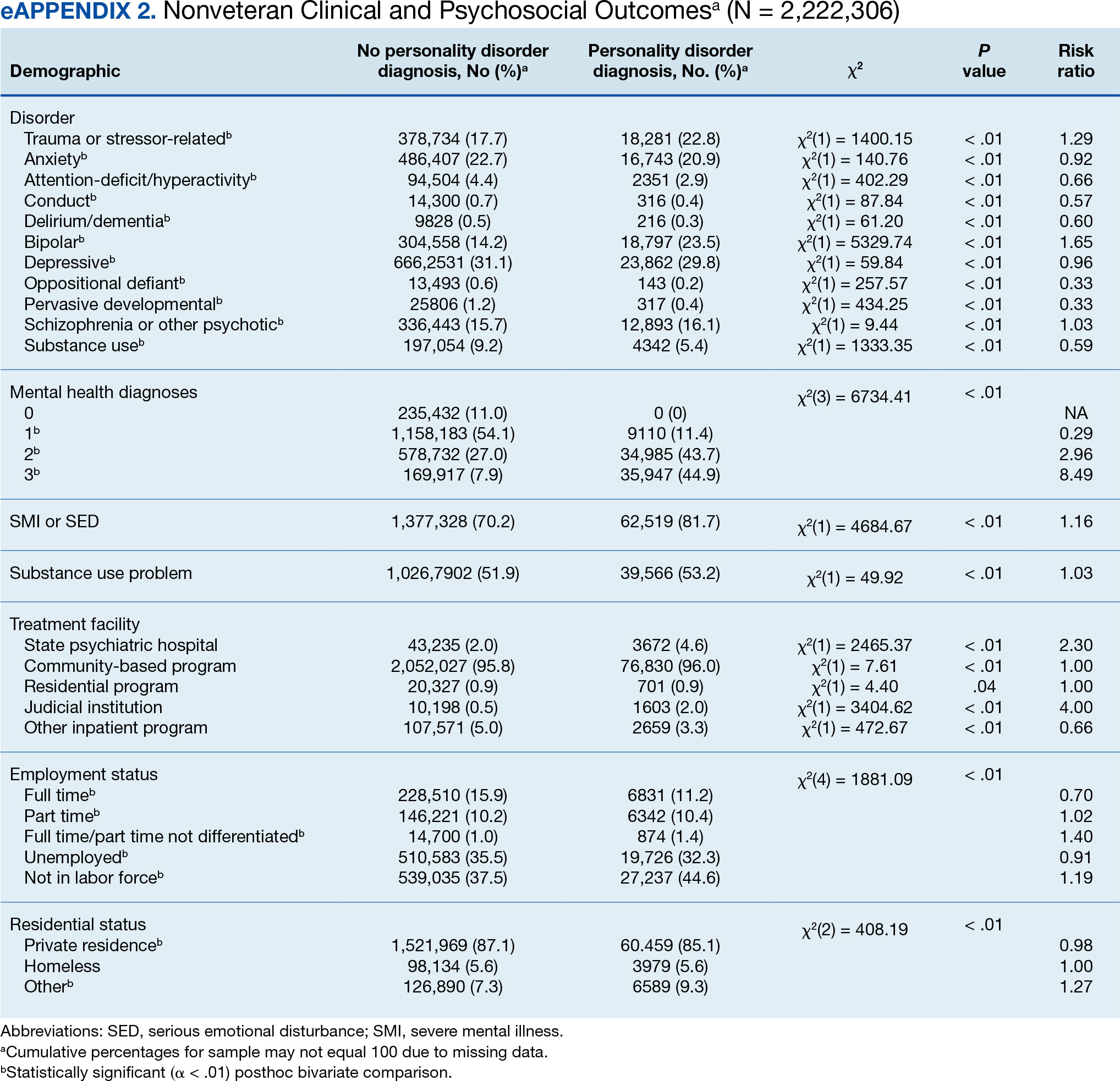

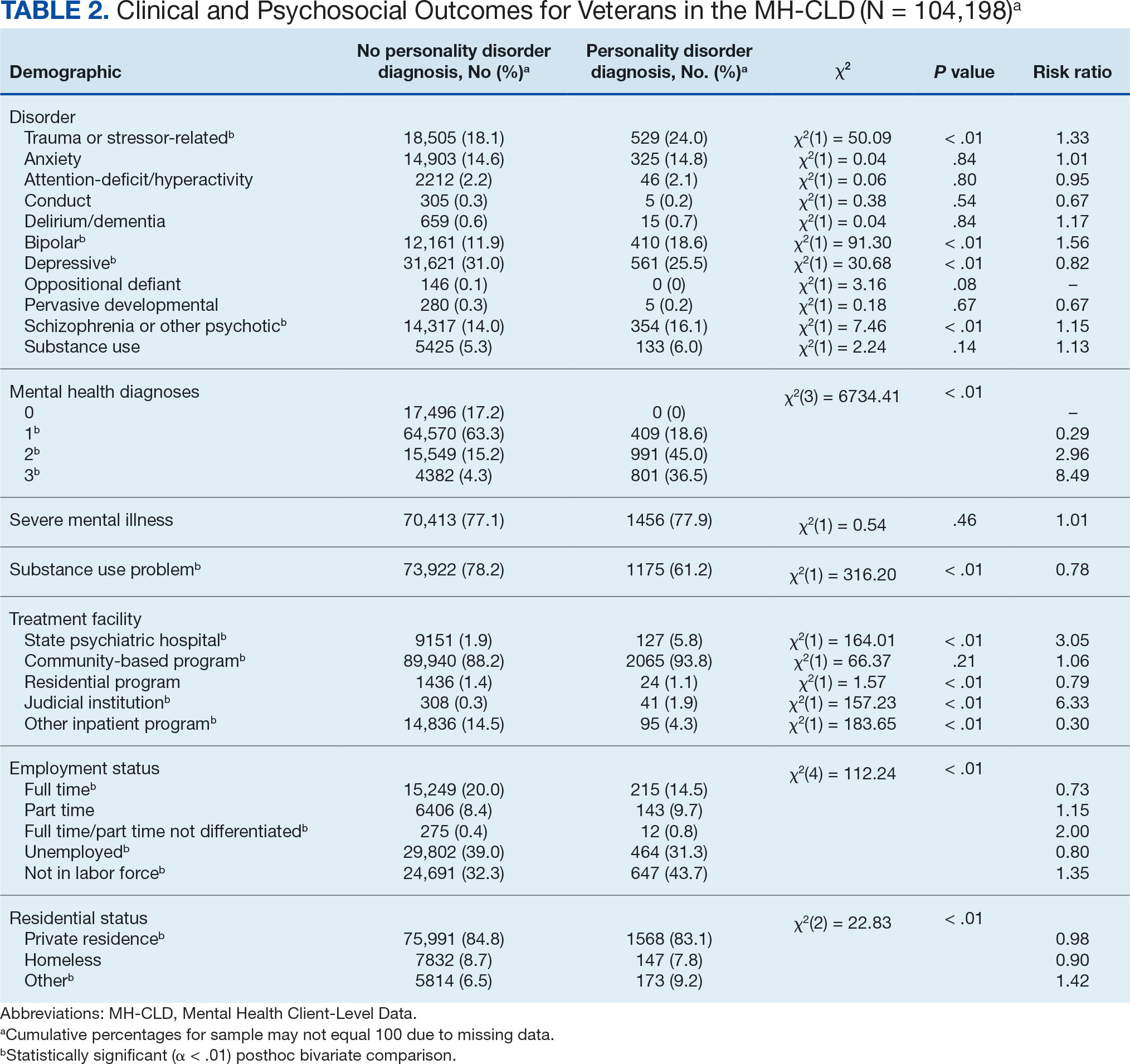

Clinical information. Up to 3 mental health diagnoses were reported for each patient and included the following disorders: personality, trauma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity, stressor, anxiety, conduct, delirium/dementia, bipolar, depressive, oppositional defiant, pervasive developmental, schizophrenia or other psychotic, and alcohol or substance use. Mental health diagnosis categories were generated for the parent dataset by grouping diagnostic codes corresponding to each category. To protect patient privacy, more detailed diagnostic information was not available as part of the parent dataset. Although the American Psychiatric Association recognizes 10 distinct PDs, the exact nature of PD diagnoses was not included within the parent dataset. PD diagnoses were coded to reflect the presence or absence of any such diagnosis.

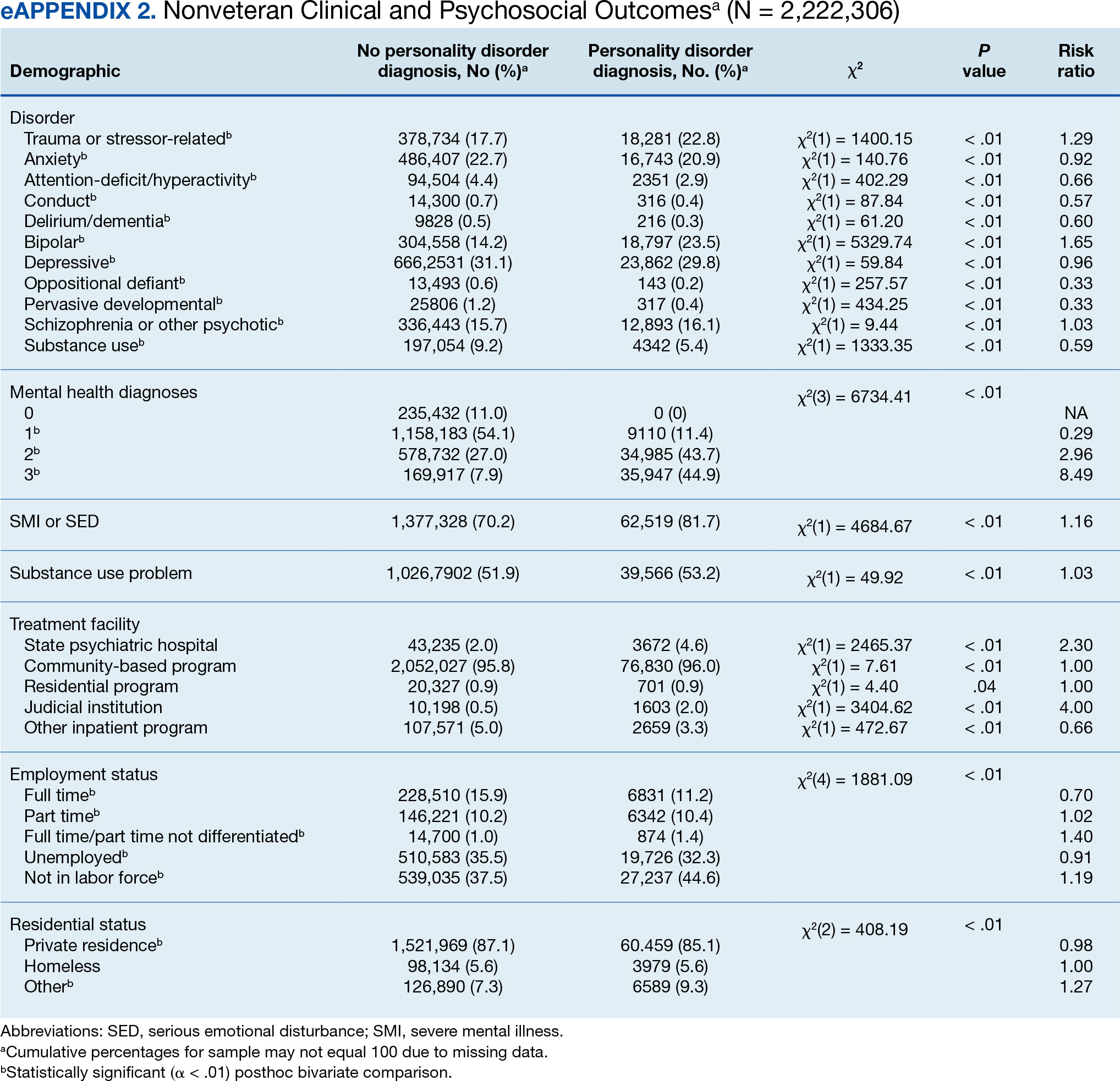

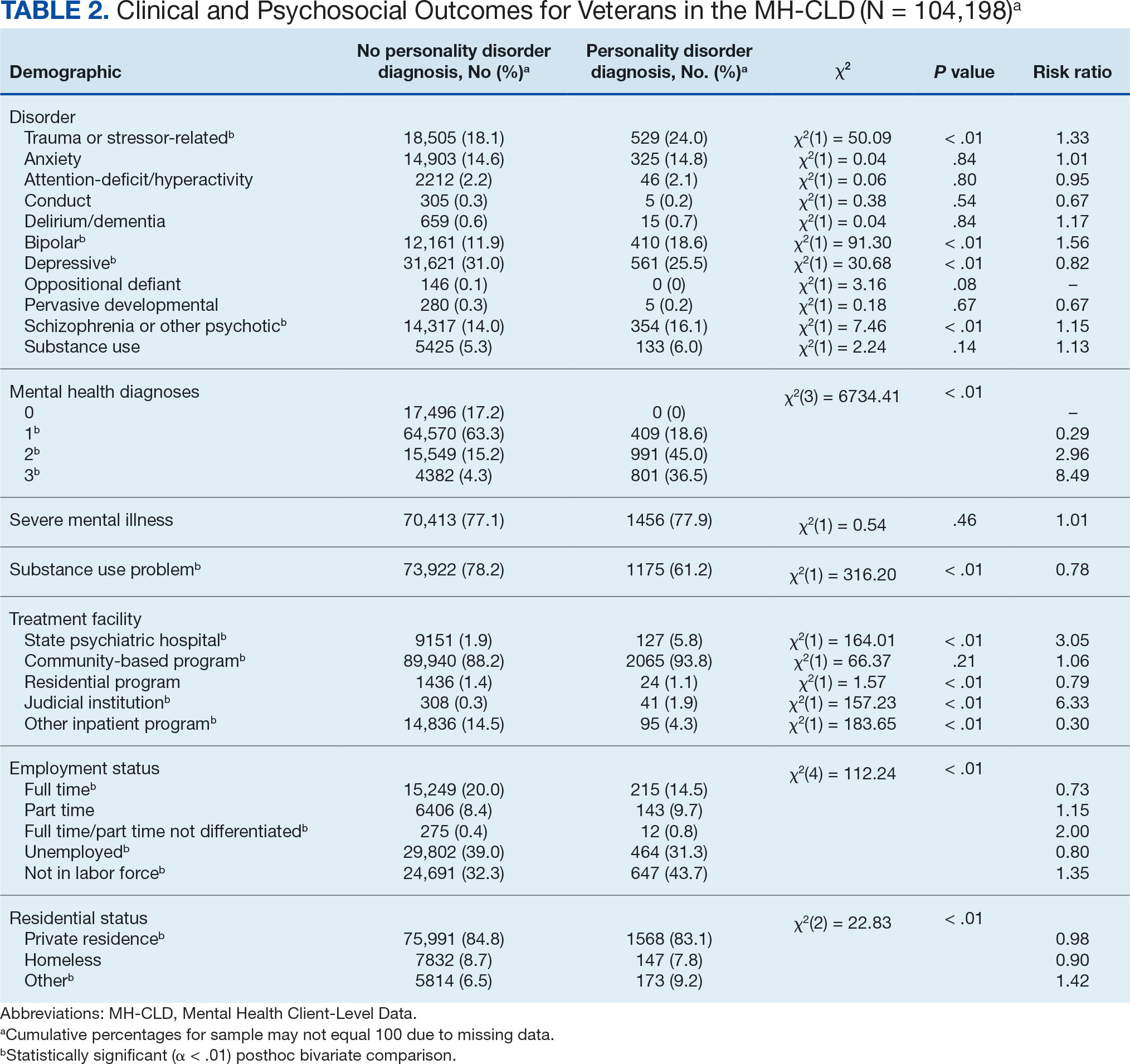

A substance use problem designation was also provided for patients according to various identification methods, including substance use disorder (SUD) diagnosis, substance use screening results, enrollment in a substance use program, substance use survey, service claims information, and other related sources of information. A severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance designation was provided for patients meeting state definitions of these designations. Context(s) of service provision were coded as inpatient state psychiatric hospital, community-based program, residential treatment center, judicial institution, or other psychiatric inpatient setting.

Psychosocial outcome information. Patient employment and residential status were also included in analyses. Each reflected status at the time of discharge from services or end of reporting period; employment status was only provided for patients receiving treatment in community-based programs.

Data Analysis

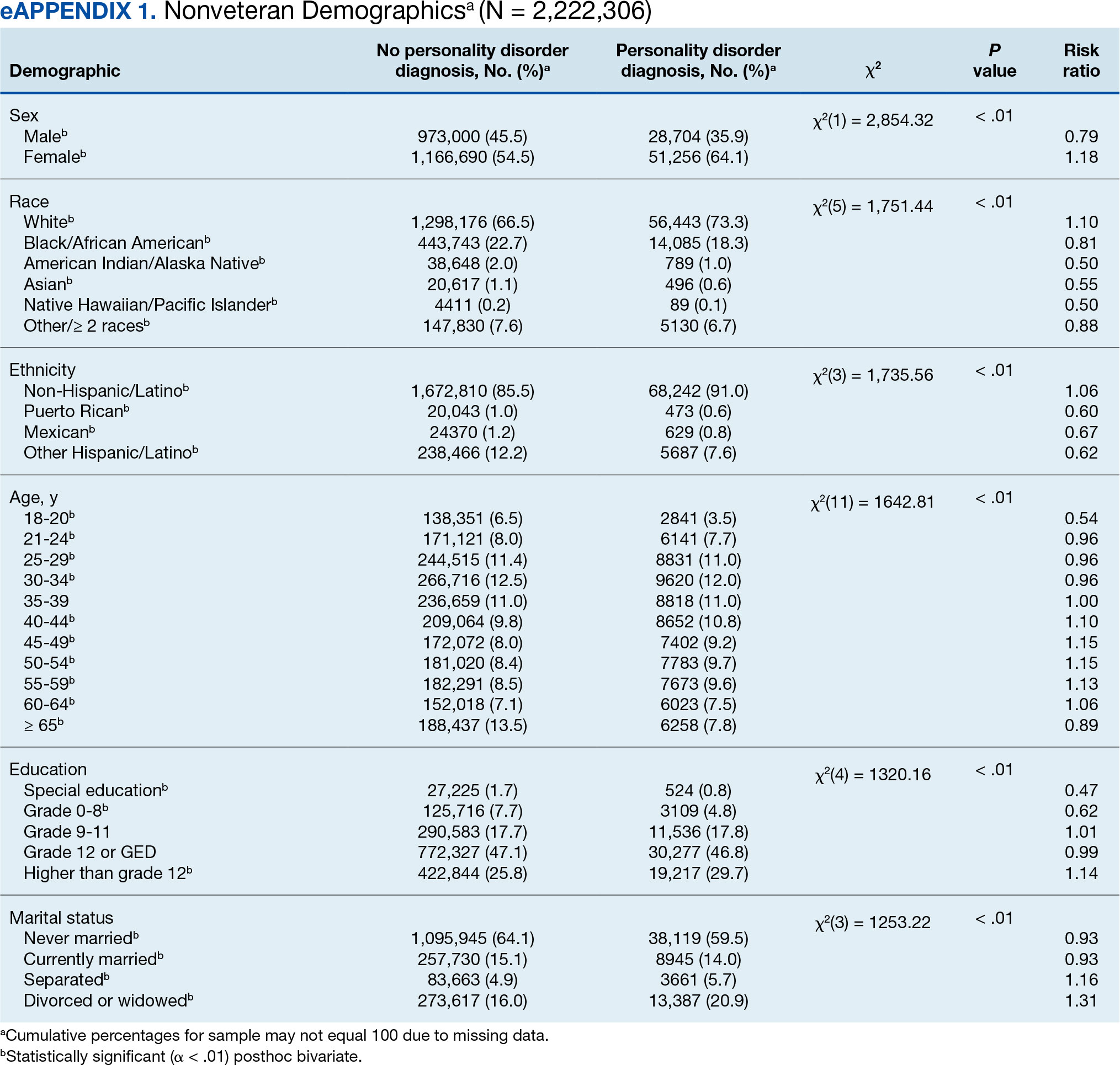

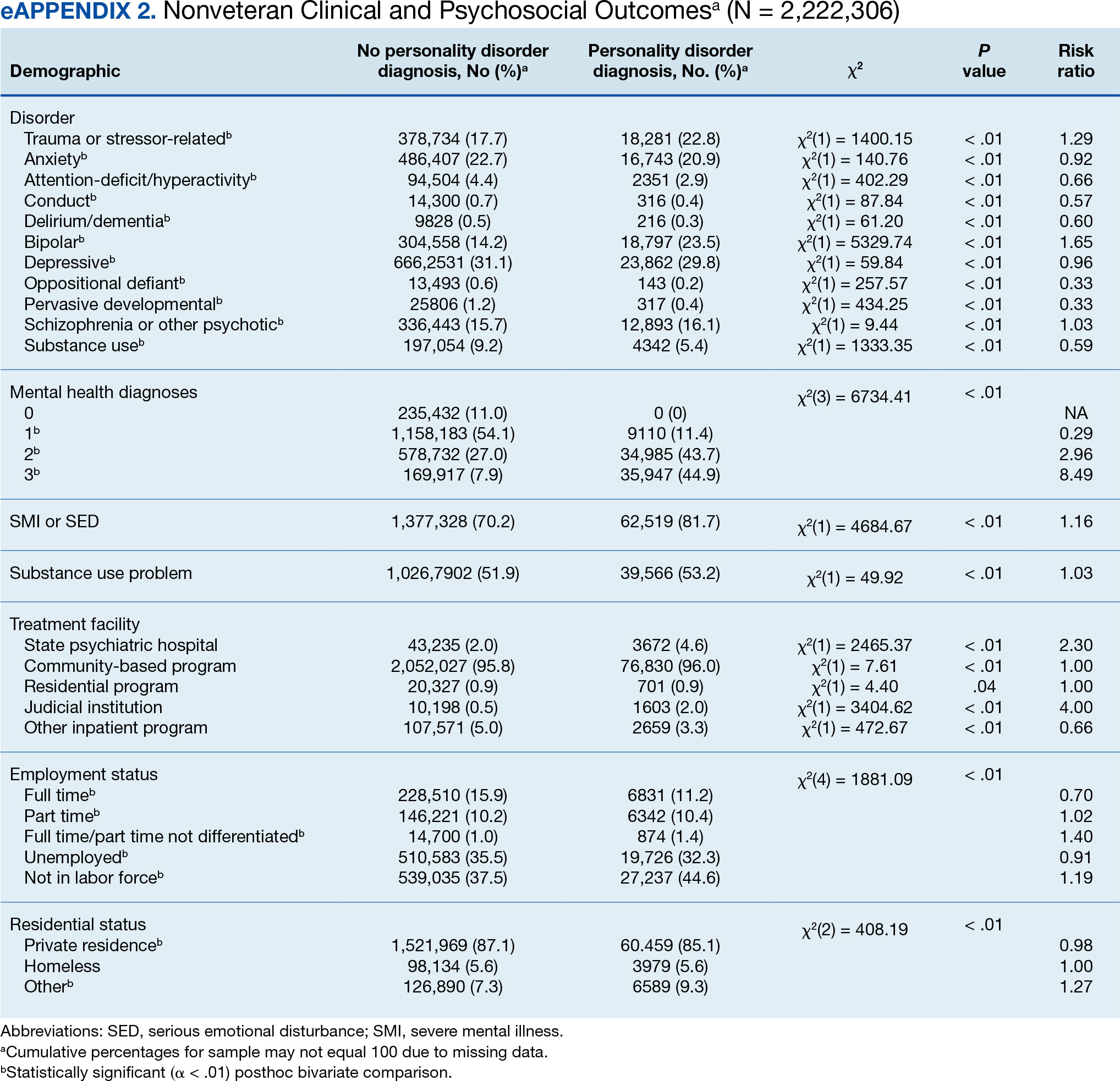

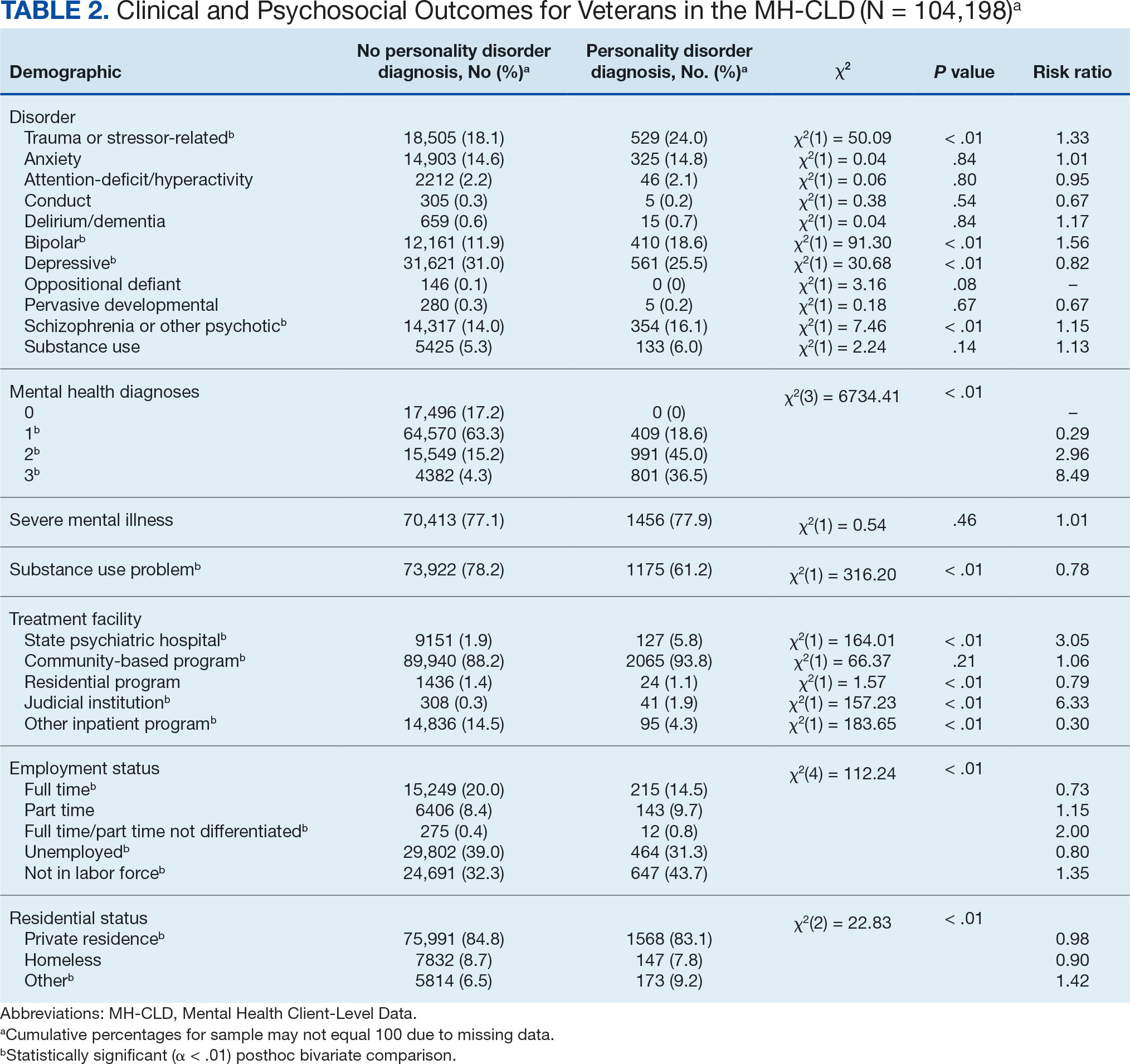

Descriptive statistics and X2 analyses were used to compare demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome variables between patients with and without PD diagnoses. These analyses were calculated for both the 104,198 veterans and the 2,222,306 nonveterans aged ≥ 18 years in the dataset. Given the sample size, a conservative α of .01 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

In this sample of persons receiving state-funded mental health care, veterans were significantly less likely than nonveterans to have a documented PD diagnosis (2.1% vs 3.6%, X2 [1] = 647.49; P < .01). PD diagnoses were more common among White (risk ratio [RR], 1.11), non-Hispanic (RR, 1.03) veterans who were in middle to late adulthood (RR, 1.16-1.40), more educated (RR, 1.35), and divorced or widowed (RR, 1.43), and less common among Black/African American (RR, 0.78) or Puerto Rican (RR, 0.32) veterans who were in early adulthood (RR, 0.31-0.79), less educated (RR, 0.64-0.89), and currently married (RR, 0.89) or never married (RR, 0.86). Veteran men and women were equally likely to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 1.03) (Table 1). Among nonveterans, men were less likely than women to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.79), and PD diagnoses were most common among persons in middle adulthood (RR, 1.06-1.15) (eAppendix 1).

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were more likely than those without a diagnosis to have more diagnoses (RR, 2.96-8.49) and to have comorbid trauma or related stressor (RR, 1.33), or bipolar (RR, 1.56) or psychotic (RR, 1.15) disorder diagnoses, but less likely to have comorbid depressive disorder (RR, 0.82). Although veterans with and without a PD diagnosis were similarly likely to have a comorbid SUD (RR, 1.13), those with a PD diagnosis were significantly less likely to be assigned a substance use problem designation (RR, 0.78). PD diagnosis was also more common among veterans who received services in state psychiatric hospitals (RR, 3.05), community-based clinics (RR, 1.06), and judicial institutions (RR, 6.33) and less common among those who received services in other psychiatric inpatient settings (RR, 0.30). No differences were observed for residential treatment settings (RR, 0.79). Among nonveterans, a PD diagnosis was associated with slightly greater odds of a substance use designation (RR, 1.03) (eAppendix 2).

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also less likely to have full-time employment (RR, 0.73) and more likely to have undifferentiated employment (RR, 2.00) or to be removed from the labor force (RR, 1.35). Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also more likely to reside in nontraditional living conditions (RR, 1.42) and less likely to be residing in a private residence (RR, 0.98), compared with those without PD diagnosis. The rates of homelessness were similar for veterans with and without a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.90) (Table 2). These patterns were similar among nonveterans.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the rate and correlates of PD diagnosis among a large, community-based sample of veterans receiving state-funded mental health care. About 2% of veterans in this sample had a PD diagnosis, with diagnoses more common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, aged ≥ 45 years, with higher education, divorced or widowed, also diagnosed with trauma-related, bipolar, and/or psychotic disorders, underemployed, nontraditionally housed, and receiving treatment in state psychiatric hospital, community-based clinic, or judicial system settings.

The observed rate of PD diagnosis in this study aligns with what is typically observed in VHA EHRs.8,18,19 However, the rate is notably lower than prevalence estimates for psychiatric outpatient settings (about 50%) and in meta-analyses of prevalence among veterans (0.8%-23% for each of the 10 PDs).4,17,26 Longstanding stigma against PDs may contribute to underdiagnosis. For example, many clinicians are concerned that documentation or disclosure of a PD will interfere with the patient’s ability to access treatment due to stigma and discrimination.27,28 These fears are not unfounded; even among clinicians, PDs are commonly considered untreatable, and many individuals with PDs are denied access to evidence-based treatments due to the diagnosis.29 In a 2016 survey of community psychiatrists, nearly 1 in 4 reported that they avoid taking patients with a borderline PD diagnosis in their caseloads.28 To date, no studies have been conducted to explore clinicians’ willingness to accept patients with other PDs or, specifically, among veterans.

Despite such widespread stigma, research suggests clinicians' negative attitudes toward PDs can be decreased through antistigma campaigns.30 However, it remains unclear if such efforts also contribute to an increase in clinicians’ willingness to document PD diagnoses. Without accurate identification and documentation, the field’s understanding of PDs will remain limited.

In the current study, veterans with PD diagnoses tended to present with more complex and severe psychiatric comorbidities compared to veterans without such diagnoses. Observed comorbidity of PDs (particularly borderline PD) with trauma-related and bipolar disorders is well established.8 Conversely, co-occurring personality and psychotic disorders—which comprise 16% of veterans with a PD diagnosis in the sample in this study—are not consistently examined in the literature. A 2022 examination of veterans receiving VHA care suggested 12% and 13% of those with a PD diagnosis documented in their EHR also had documented schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, respectively. PD diagnoses were associated with 6.88- and 9.80-fold increases in risk for comorbid schizophrenia and other psychotic disorder diagnoses, respectively.8 Similarly, a recent longitudinal study of nearly 2 million Swedish individuals suggested borderline PD is specifically associated with a > 24-times greater risk of having a comorbid psychotic disorder.31 It is therefore possible that the comorbidity between personality and psychotic disorders is quite common despite its relative lack of attention in empirical research.

Veterans with PD diagnoses in this study were also more likely to experience substandard housing, employment challenges, and receive treatment through judicial institutions than those without a PD diagnosis. Such findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating the substantial psychosocial challenges associated with PD diagnosis, even after controlling for comorbid conditions.7,9 Veterans with PDs may benefit from specialized case management and support to facilitate stable housing and employment and to mitigate the risk of judicial involvement. Some research suggests veterans with PDs may be less likely to gain competitive employment after participating in VA therapeutic and supportive employment services programs, suggesting standard programming may be less suitable for this population.32 Similarly, other research suggests individuals with PDs may benefit more from specialized, intensive services than standard clinical case management.33 Future research may therefore benefit from clarifying the degree to which adaptations to standard programming could yield beneficial effects for persons with PD diagnoses.

Implications