User login

Managing Resistance to Change Along the Journey to High Reliability

Managing Resistance to Change Along the Journey to High Reliability

To improve safety performance, many health care organizations have embarked on the journey to becoming high reliability organizations (HROs). HROs operate in complex, high-risk, constantly changing environments and avoid catastrophic events despite the inherent risks.1 HROs maintain high levels of safety and reliability by adhering to core principles, foundational practices, rigorous processes, a strong organizational culture, and continuous learning and process improvement.1-3

Becoming an HRO requires understanding what makes systems safer for patients and staff at all levels by taking ownership of 5 principles: (1) sensitivity to operations (increased awareness of the current status of systems); (2) reluctance to simplify (avoiding oversimplification of the cause[s] of problems); (3) preoccupation with failure (anticipating risks that might be symptomatic of a larger problem); (4) deference to expertise (relying on the most qualified individuals to make decisions); and (5) commitment to resilience (planning for potential failure and being prepared to respond).1,2,4 In addition to these, the Veterans Health Administration has identified 3 pillars of HROs: leadership commitment (safety and reliability are central to leadership vision, decision-making, and action-oriented behaviors), safety culture (across the organization, safety values are key to preventing harm and learning from mistakes), and continuous process improvement (promoting constant learning and improvement with evidence-based tools and methodologies).5

Implementing these principles is not enough to achieve high reliability. This transition requires significant change, which can be met with resistance. Without attending to organizational change, implementation of HRO principles can be superficial, scattered, and isolated.6 Large organizations often struggle with change as it conflicts with the fundamental human need for stability and security.7 Consequently, the journey to becoming an HRO requires an understanding of the reasons for resistance to change (RtC) as well as evidence-based strategies.

REASONS FOR RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

RtC is the informal and covert behavior of an individual or group to a particular change. RtC is commonly recognized as the failure of employees to do anything requested by managers and is a main reason change initiatives fail.8 While some staff see change as opportunities for learning and growth, others resist based on uncertainty about how the changes will impact their current work situation, or fear, frustration, confusion, and distrust.8,9 Resistance can overtly manifest with some staff publicly expressing their discontent in public without offering solutions, or covertly by ignoring the change or avoiding participation in any aspect of the change process. Both forms of RtC are equally detrimental.8

Frequent changes in organizations can also cause cynicism. Employees will view the change as something initially popular, but will only last until another change comes along.8,9 Resistance can result in the failure to achieve desired objectives, wasted time, effort, and resources, decreased momentum, and loss of confidence and trust in leaders to effectively manage the change process.9 To understand RtC, 3 main factors must be considered: individual, interpersonal, and organizational.

Individual

An individual’s personality can be an important indicator for how they will respond to change. Some individuals welcome and thrive on change while others resist in preference for the status quo.8,10 Individuals will also resist change if they believe their position, power, or prestige within the organization are in jeopardy or that the change is contrary to current personal or organizational values, principles, and objectives.8-12 Resistance can also be the result of uncertainty about what the change means, lack of information regarding the change, or questioning motives for the change.9

Interpersonal

Another influence on RtC is the interpersonal factors of employees. The personal satisfaction individuals receive from their work and the type of interactions they experience with colleagues can impact RtC. When communication with colleagues is lacking before and during change implementation, negative reactions to the change can fuel resistance.11 Cross-functional and bidirectional communication is vital; its absence can leave staff feeling inadequately informed and less supportive of the change.8 Employees’ understanding of changes through communication between other members of the organization is critical to success.11

Organizational

How organizational leaders introduce change affects the extent to which staff respond.10 RtC can emerge if staff feel change is imposed on them. Change is better received when people are actively engaged in the process and adopt a sense of ownership that will ultimately affect them and their role within the organization.12,13 Organizations are also better equipped to address potential RtC when leadership is respected and have a genuine concern for the overall well-being of staff members. Organizational leaders who mainly focus on the bottom line and have little regard for staff are more likely to be perceived as untrustworthy, which contributes to RtC.9,13 Lack of proper education and guidance from organizational leaders, as well as poor communication, can lead to RtC.8,13

MANAGING RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

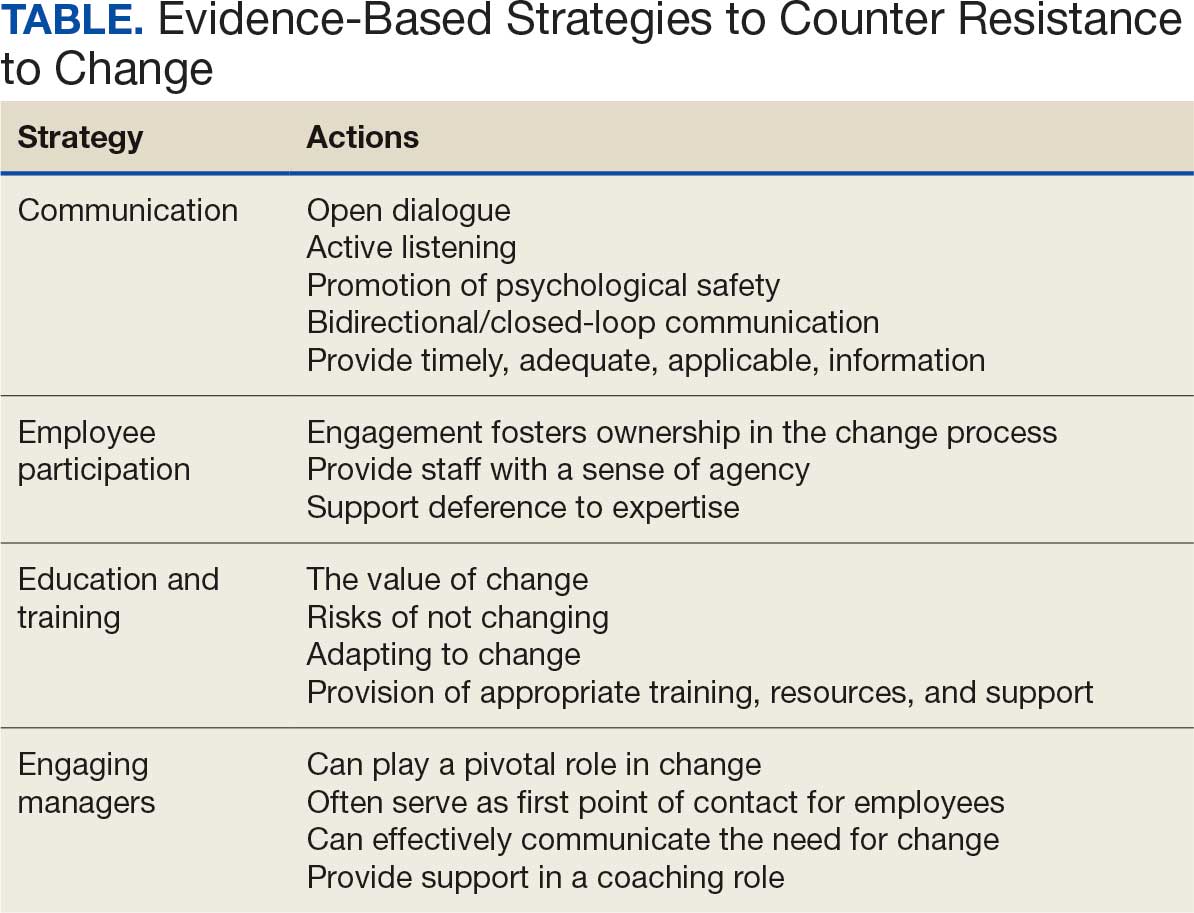

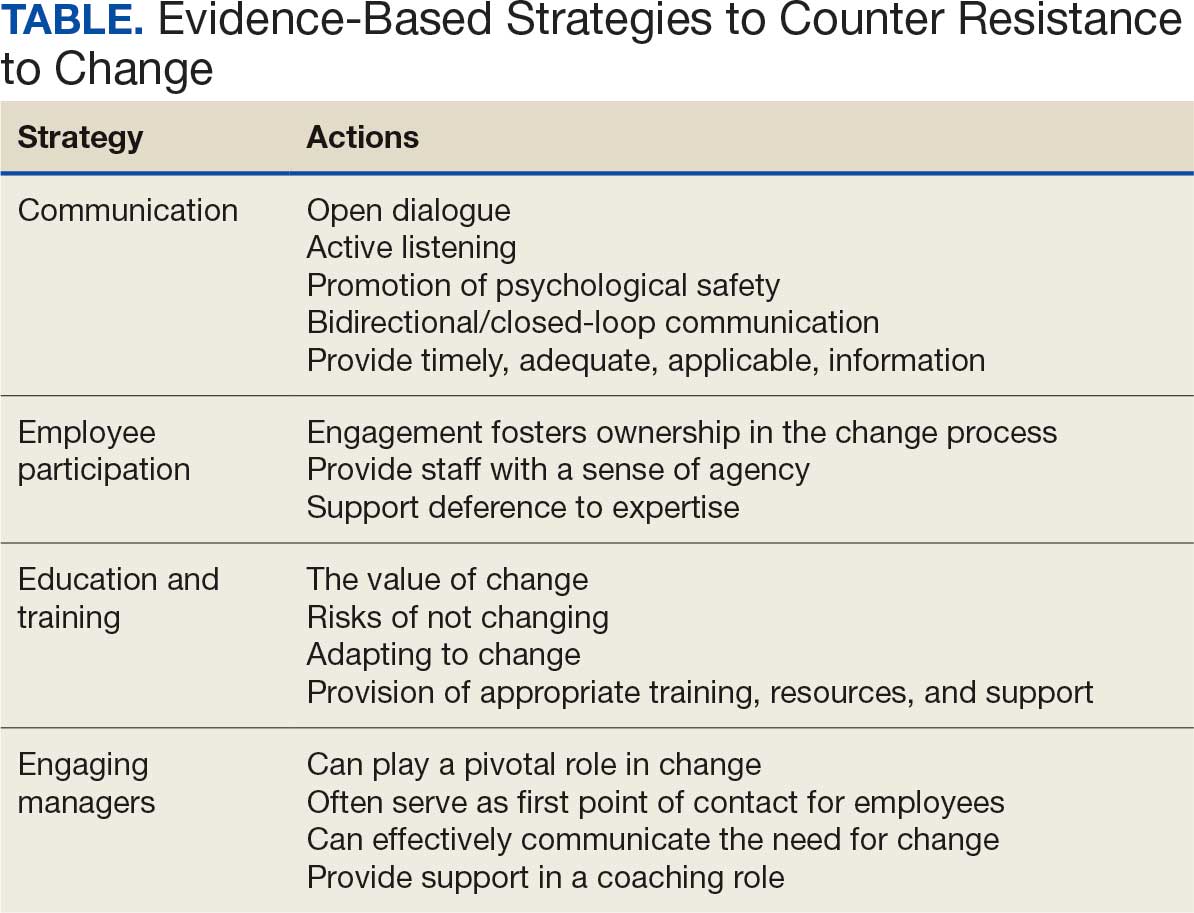

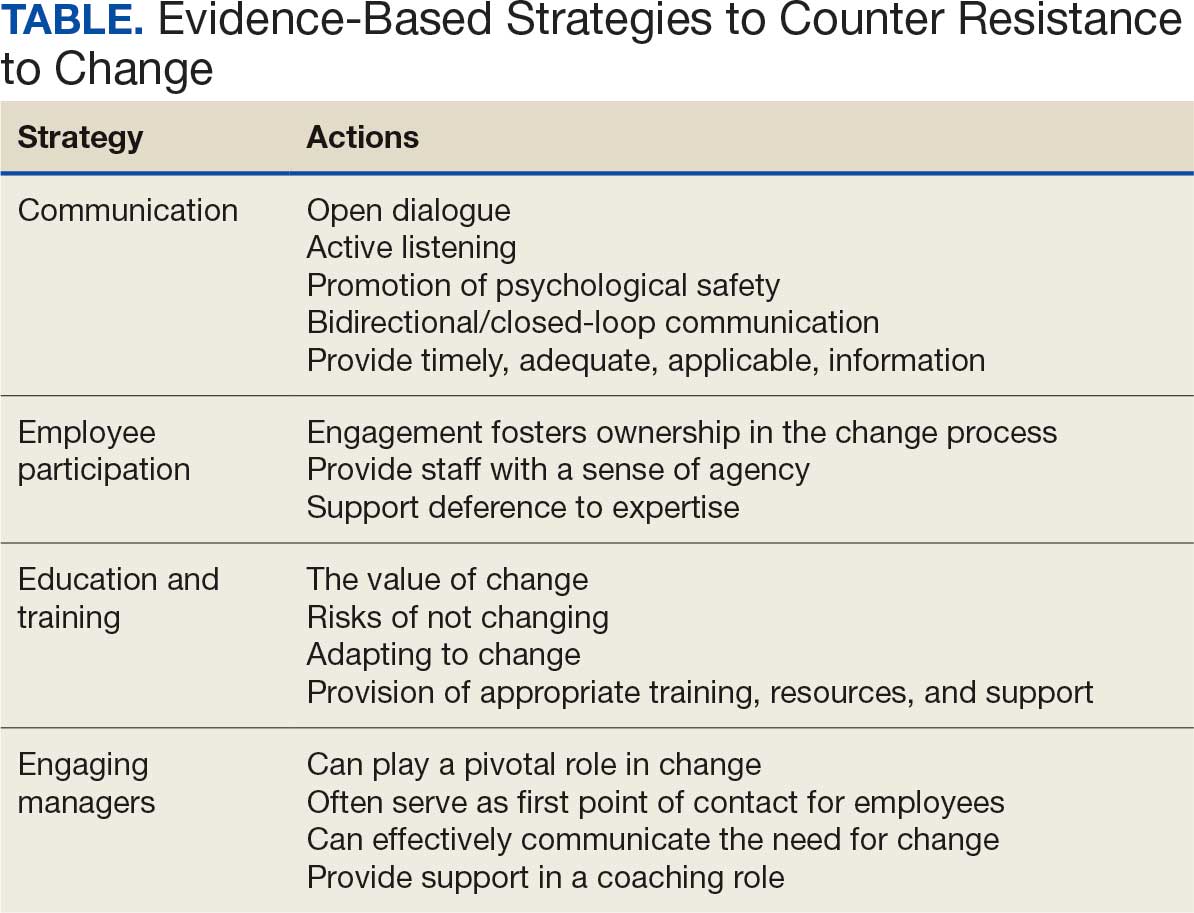

RtC can be a significant factor in the success or failure of the change process. Poorly managed change can exponentially increase resistance, necessitating a multifaceted approach to managing RtC, while well-managed change can result in a high success rate. Evidence-based strategies to counter RtC focus on communication, employee participation, education and training, and engaging managers.8

Communication

Open and effective communication is critical to managing RtC, as uncertainty often exaggerates the negative aspects of change. Effective communication involves active listening, with leadership and management addressing employee concerns in a clear and concise manner. A psychologically safe culture for open dialogue is essential when addressing RtC.9,14,15 Psychological safety empowers staff to speak up, ask questions, and offer ideas, forming a solid basis for open and effective communication and participation. Leaders and managers should create opportunities for open dialogue for all members of the organization throughout the process. This can be accomplished with one-on-one meetings, open forums, town hall meetings, electronic mail, newsletters, and social media. Topics should cover the reasons for change, details of what is changing, the individual, organizational, and patient risks of not changing, as well as the benefits of changing.9 Encouraging staff to ask questions and provide feedback to promote bidirectional and closed-loop communication is essential to avoid misunderstandings.9,15 While open communication is essential, leaders must carefully plan what information to share, how much to share, and how to avoid information overload. Information about the change should be timely, adequate, applicable, and informative.15 The HRO practice of leader rounding for high reliability can be instrumental to ensure effective, bidirectional communication and collaboration among all disciplines across a health care organization through improving leadership visibility during times of change and enhancing interactions and communication with staff.3

Employee Participation

Involving staff in the change process significantly reduces RtC. Engagement fosters ownership in the change process, increasing the likelihood employees will support and even champion it. Health care professionals welcome opportunities to be involved in helping with aspects of organizational change, especially when invited to participate in the change early in the process and throughout the course of change.7,14,15

Leaders should encourage staff to provide feedback to understand the impact the change is having on them and their roles and responsibilities within the organization. This exemplifies the HRO principle of deference to expertise as the employee often has the most in-depth knowledge of their work setting. Employee perspectives can significantly influence the success of change initatives.7,14 Participation is impactful in providing employees with a sense of agency facilitating acceptance and improving desire to adopt the change.14

Tiered safety huddles and visual management systems (VMSs) also can engage staff. Tiered safety huddles provide a forum for transparent communication, increasing situational awareness, and improving a health care organization’s ability to appropriately respond to staff questions, suggestions, and concerns. VMSs display the status and progress toward organizational goals during the change process, and are highly effective in creating environments where staff feel empowered to voice concerns related to the change process.3

Education and Training

Educating employees on the value of change is crucial to overcome RtC. RtC often stems from employees not feeling prepared to adapt or adopt new processes. Health care professionals who do not receive information about change are less likely to support it.7,12,15 Staff are more likely to accept change when they understand why it is needed and how it impacts the organization’s long-term mission.11,15 Timely, compelling, and informative education on how to adapt to the change will promote more positive appraisal of the change and reduce RtC.8,15 Employees must feel confident they will receive the appropriate training, resources, and support to successfully adapt to the change. This requires leaders and managers taking time to clarify expectations, conduct a gap analysis to identify the skills and knowledge needed to support the planned change, and provide sufficient educational opportunities to fill those gaps.8 For example, the US Department of Veterans Affairs offers classes to employees on the Prosci ADKAR (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) Model. This training provides individuals with the information and skills needed for change to be successful.16

Safety forums can be influential and allow leadership to educate staff on updates related to change processes and promote bidirectional communication.3 In safety forums, staff have an opportunity to ask questions, especially as they relate to learning about available resources to become more informed about the organizational changes.

Engaging Managers

Managers are pivotal to the successful implementation of organizational change.8 They serve as the bridge between senior leadership and frontline employees and are positioned to influence the adoption and success of change initiatives. Often the first point of contact for employees, managers can effectively communicate the need for change, and act as the liaison to align it with individual employee motivations. Since they are often the first to encounter resistance among employees, managers serve as advocates through the process. Through a coaching role, managers can help employees develop the knowledge and ability to be successful and thrive in the new environment. The Table summarizes the evidence-based strategies.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementing change in health care organizations can be challenging, especially on the journey to high reliability. RtC is the result of factors at the individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels that leaders must address to increase chances for success. Organizational changes in health care are more likely to succeed when staff understand why the change is needed through open and continuous communication, can influence the change by sharing their own perspectives, and have the knowledge, skills, and resources to prepare for and participate in the process.

- Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Dealing-Perez C, et al. A high-reliability organization mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37:504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

- Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D, et al. Implementing high-reliability organization principles into practice: a rapid evidence review. J Patient Saf. 2022;18:e320-e328. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000768

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, et al. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41:214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Ford J, Isaacks DB, Anderson T. Creating, executing and sustaining a high-reliability organization in health care. The Learning Organization: An International Journal. 2024;31:817-833. doi:10.1108/TLO-03-2023-0048

- Cox GR, Starr LM. VHA’s movement for change: implementing high-reliability principles and practices. J Healthc Manag. 2023;68:151-157. doi:10.1097/JHM-D-00056

- Myers CG, Sutcliffe KM. High reliability organising in healthcare: still a long way left to go. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31:845-848. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014141

- Nilsen P, Seing I, Ericsson C, et al. Characteristics of successful changes in health care organizations: an interview study with physicians, registered nurses and assistant nurses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:147. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-4999-8

- Cheraghi R, Ebrahimi H, Kheibar N, et al. Reasons for resistance to change in nursing: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:310. doi:10/1186/s12912-023-01460-0

- Warrick DD. Revisiting resistance to change and how to manage it: what has been learned and what organizations need to do. Bus Horiz. 2023;66:433-441. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2022.09.001

- Sverdlik N, Oreg S. Beyond the individual-level conceptualization of dispositional resistance to change: multilevel effects on the response to organizational change. J Organ Behav. 2023;44:1066-1077. doi:10.1002/job.2678

- Khaw KW, Alnoor A, Al-Abrrow H, et al. Reactions towards organizational change: a systematic literature review. Curr Psychol. 2022;13:1-24. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03070-6

- Pomare C, Churruca K, Long JC, et al. Organisational change in hospitals: a qualitative case-study of staff perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:840. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4704-y

- DuBose BM, Mayo AM. RtC: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2020;55:631-636. doi:10.1111/nuf.12479

- Sahay S, Goldthwaite C. Participatory practices during organizational change: rethinking participation and resistance. Manag Commun Q. 2024;38(2):279-306. doi:10.1177/08933189231187883

- Damawan AH, Azizah S. Resistance to change: causes and strategies as an organizational challenge. ASSEHR. 2020;395(2020):49-53. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.200120.010

- Wong Q, Lacombe M, Keller R, et al. Leading change with ADKAR. Nurs Manage. 2019;50:28-35. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000554341.70508.75

To improve safety performance, many health care organizations have embarked on the journey to becoming high reliability organizations (HROs). HROs operate in complex, high-risk, constantly changing environments and avoid catastrophic events despite the inherent risks.1 HROs maintain high levels of safety and reliability by adhering to core principles, foundational practices, rigorous processes, a strong organizational culture, and continuous learning and process improvement.1-3

Becoming an HRO requires understanding what makes systems safer for patients and staff at all levels by taking ownership of 5 principles: (1) sensitivity to operations (increased awareness of the current status of systems); (2) reluctance to simplify (avoiding oversimplification of the cause[s] of problems); (3) preoccupation with failure (anticipating risks that might be symptomatic of a larger problem); (4) deference to expertise (relying on the most qualified individuals to make decisions); and (5) commitment to resilience (planning for potential failure and being prepared to respond).1,2,4 In addition to these, the Veterans Health Administration has identified 3 pillars of HROs: leadership commitment (safety and reliability are central to leadership vision, decision-making, and action-oriented behaviors), safety culture (across the organization, safety values are key to preventing harm and learning from mistakes), and continuous process improvement (promoting constant learning and improvement with evidence-based tools and methodologies).5

Implementing these principles is not enough to achieve high reliability. This transition requires significant change, which can be met with resistance. Without attending to organizational change, implementation of HRO principles can be superficial, scattered, and isolated.6 Large organizations often struggle with change as it conflicts with the fundamental human need for stability and security.7 Consequently, the journey to becoming an HRO requires an understanding of the reasons for resistance to change (RtC) as well as evidence-based strategies.

REASONS FOR RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

RtC is the informal and covert behavior of an individual or group to a particular change. RtC is commonly recognized as the failure of employees to do anything requested by managers and is a main reason change initiatives fail.8 While some staff see change as opportunities for learning and growth, others resist based on uncertainty about how the changes will impact their current work situation, or fear, frustration, confusion, and distrust.8,9 Resistance can overtly manifest with some staff publicly expressing their discontent in public without offering solutions, or covertly by ignoring the change or avoiding participation in any aspect of the change process. Both forms of RtC are equally detrimental.8

Frequent changes in organizations can also cause cynicism. Employees will view the change as something initially popular, but will only last until another change comes along.8,9 Resistance can result in the failure to achieve desired objectives, wasted time, effort, and resources, decreased momentum, and loss of confidence and trust in leaders to effectively manage the change process.9 To understand RtC, 3 main factors must be considered: individual, interpersonal, and organizational.

Individual

An individual’s personality can be an important indicator for how they will respond to change. Some individuals welcome and thrive on change while others resist in preference for the status quo.8,10 Individuals will also resist change if they believe their position, power, or prestige within the organization are in jeopardy or that the change is contrary to current personal or organizational values, principles, and objectives.8-12 Resistance can also be the result of uncertainty about what the change means, lack of information regarding the change, or questioning motives for the change.9

Interpersonal

Another influence on RtC is the interpersonal factors of employees. The personal satisfaction individuals receive from their work and the type of interactions they experience with colleagues can impact RtC. When communication with colleagues is lacking before and during change implementation, negative reactions to the change can fuel resistance.11 Cross-functional and bidirectional communication is vital; its absence can leave staff feeling inadequately informed and less supportive of the change.8 Employees’ understanding of changes through communication between other members of the organization is critical to success.11

Organizational

How organizational leaders introduce change affects the extent to which staff respond.10 RtC can emerge if staff feel change is imposed on them. Change is better received when people are actively engaged in the process and adopt a sense of ownership that will ultimately affect them and their role within the organization.12,13 Organizations are also better equipped to address potential RtC when leadership is respected and have a genuine concern for the overall well-being of staff members. Organizational leaders who mainly focus on the bottom line and have little regard for staff are more likely to be perceived as untrustworthy, which contributes to RtC.9,13 Lack of proper education and guidance from organizational leaders, as well as poor communication, can lead to RtC.8,13

MANAGING RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

RtC can be a significant factor in the success or failure of the change process. Poorly managed change can exponentially increase resistance, necessitating a multifaceted approach to managing RtC, while well-managed change can result in a high success rate. Evidence-based strategies to counter RtC focus on communication, employee participation, education and training, and engaging managers.8

Communication

Open and effective communication is critical to managing RtC, as uncertainty often exaggerates the negative aspects of change. Effective communication involves active listening, with leadership and management addressing employee concerns in a clear and concise manner. A psychologically safe culture for open dialogue is essential when addressing RtC.9,14,15 Psychological safety empowers staff to speak up, ask questions, and offer ideas, forming a solid basis for open and effective communication and participation. Leaders and managers should create opportunities for open dialogue for all members of the organization throughout the process. This can be accomplished with one-on-one meetings, open forums, town hall meetings, electronic mail, newsletters, and social media. Topics should cover the reasons for change, details of what is changing, the individual, organizational, and patient risks of not changing, as well as the benefits of changing.9 Encouraging staff to ask questions and provide feedback to promote bidirectional and closed-loop communication is essential to avoid misunderstandings.9,15 While open communication is essential, leaders must carefully plan what information to share, how much to share, and how to avoid information overload. Information about the change should be timely, adequate, applicable, and informative.15 The HRO practice of leader rounding for high reliability can be instrumental to ensure effective, bidirectional communication and collaboration among all disciplines across a health care organization through improving leadership visibility during times of change and enhancing interactions and communication with staff.3

Employee Participation

Involving staff in the change process significantly reduces RtC. Engagement fosters ownership in the change process, increasing the likelihood employees will support and even champion it. Health care professionals welcome opportunities to be involved in helping with aspects of organizational change, especially when invited to participate in the change early in the process and throughout the course of change.7,14,15

Leaders should encourage staff to provide feedback to understand the impact the change is having on them and their roles and responsibilities within the organization. This exemplifies the HRO principle of deference to expertise as the employee often has the most in-depth knowledge of their work setting. Employee perspectives can significantly influence the success of change initatives.7,14 Participation is impactful in providing employees with a sense of agency facilitating acceptance and improving desire to adopt the change.14

Tiered safety huddles and visual management systems (VMSs) also can engage staff. Tiered safety huddles provide a forum for transparent communication, increasing situational awareness, and improving a health care organization’s ability to appropriately respond to staff questions, suggestions, and concerns. VMSs display the status and progress toward organizational goals during the change process, and are highly effective in creating environments where staff feel empowered to voice concerns related to the change process.3

Education and Training

Educating employees on the value of change is crucial to overcome RtC. RtC often stems from employees not feeling prepared to adapt or adopt new processes. Health care professionals who do not receive information about change are less likely to support it.7,12,15 Staff are more likely to accept change when they understand why it is needed and how it impacts the organization’s long-term mission.11,15 Timely, compelling, and informative education on how to adapt to the change will promote more positive appraisal of the change and reduce RtC.8,15 Employees must feel confident they will receive the appropriate training, resources, and support to successfully adapt to the change. This requires leaders and managers taking time to clarify expectations, conduct a gap analysis to identify the skills and knowledge needed to support the planned change, and provide sufficient educational opportunities to fill those gaps.8 For example, the US Department of Veterans Affairs offers classes to employees on the Prosci ADKAR (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) Model. This training provides individuals with the information and skills needed for change to be successful.16

Safety forums can be influential and allow leadership to educate staff on updates related to change processes and promote bidirectional communication.3 In safety forums, staff have an opportunity to ask questions, especially as they relate to learning about available resources to become more informed about the organizational changes.

Engaging Managers

Managers are pivotal to the successful implementation of organizational change.8 They serve as the bridge between senior leadership and frontline employees and are positioned to influence the adoption and success of change initiatives. Often the first point of contact for employees, managers can effectively communicate the need for change, and act as the liaison to align it with individual employee motivations. Since they are often the first to encounter resistance among employees, managers serve as advocates through the process. Through a coaching role, managers can help employees develop the knowledge and ability to be successful and thrive in the new environment. The Table summarizes the evidence-based strategies.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementing change in health care organizations can be challenging, especially on the journey to high reliability. RtC is the result of factors at the individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels that leaders must address to increase chances for success. Organizational changes in health care are more likely to succeed when staff understand why the change is needed through open and continuous communication, can influence the change by sharing their own perspectives, and have the knowledge, skills, and resources to prepare for and participate in the process.

To improve safety performance, many health care organizations have embarked on the journey to becoming high reliability organizations (HROs). HROs operate in complex, high-risk, constantly changing environments and avoid catastrophic events despite the inherent risks.1 HROs maintain high levels of safety and reliability by adhering to core principles, foundational practices, rigorous processes, a strong organizational culture, and continuous learning and process improvement.1-3

Becoming an HRO requires understanding what makes systems safer for patients and staff at all levels by taking ownership of 5 principles: (1) sensitivity to operations (increased awareness of the current status of systems); (2) reluctance to simplify (avoiding oversimplification of the cause[s] of problems); (3) preoccupation with failure (anticipating risks that might be symptomatic of a larger problem); (4) deference to expertise (relying on the most qualified individuals to make decisions); and (5) commitment to resilience (planning for potential failure and being prepared to respond).1,2,4 In addition to these, the Veterans Health Administration has identified 3 pillars of HROs: leadership commitment (safety and reliability are central to leadership vision, decision-making, and action-oriented behaviors), safety culture (across the organization, safety values are key to preventing harm and learning from mistakes), and continuous process improvement (promoting constant learning and improvement with evidence-based tools and methodologies).5

Implementing these principles is not enough to achieve high reliability. This transition requires significant change, which can be met with resistance. Without attending to organizational change, implementation of HRO principles can be superficial, scattered, and isolated.6 Large organizations often struggle with change as it conflicts with the fundamental human need for stability and security.7 Consequently, the journey to becoming an HRO requires an understanding of the reasons for resistance to change (RtC) as well as evidence-based strategies.

REASONS FOR RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

RtC is the informal and covert behavior of an individual or group to a particular change. RtC is commonly recognized as the failure of employees to do anything requested by managers and is a main reason change initiatives fail.8 While some staff see change as opportunities for learning and growth, others resist based on uncertainty about how the changes will impact their current work situation, or fear, frustration, confusion, and distrust.8,9 Resistance can overtly manifest with some staff publicly expressing their discontent in public without offering solutions, or covertly by ignoring the change or avoiding participation in any aspect of the change process. Both forms of RtC are equally detrimental.8

Frequent changes in organizations can also cause cynicism. Employees will view the change as something initially popular, but will only last until another change comes along.8,9 Resistance can result in the failure to achieve desired objectives, wasted time, effort, and resources, decreased momentum, and loss of confidence and trust in leaders to effectively manage the change process.9 To understand RtC, 3 main factors must be considered: individual, interpersonal, and organizational.

Individual

An individual’s personality can be an important indicator for how they will respond to change. Some individuals welcome and thrive on change while others resist in preference for the status quo.8,10 Individuals will also resist change if they believe their position, power, or prestige within the organization are in jeopardy or that the change is contrary to current personal or organizational values, principles, and objectives.8-12 Resistance can also be the result of uncertainty about what the change means, lack of information regarding the change, or questioning motives for the change.9

Interpersonal

Another influence on RtC is the interpersonal factors of employees. The personal satisfaction individuals receive from their work and the type of interactions they experience with colleagues can impact RtC. When communication with colleagues is lacking before and during change implementation, negative reactions to the change can fuel resistance.11 Cross-functional and bidirectional communication is vital; its absence can leave staff feeling inadequately informed and less supportive of the change.8 Employees’ understanding of changes through communication between other members of the organization is critical to success.11

Organizational

How organizational leaders introduce change affects the extent to which staff respond.10 RtC can emerge if staff feel change is imposed on them. Change is better received when people are actively engaged in the process and adopt a sense of ownership that will ultimately affect them and their role within the organization.12,13 Organizations are also better equipped to address potential RtC when leadership is respected and have a genuine concern for the overall well-being of staff members. Organizational leaders who mainly focus on the bottom line and have little regard for staff are more likely to be perceived as untrustworthy, which contributes to RtC.9,13 Lack of proper education and guidance from organizational leaders, as well as poor communication, can lead to RtC.8,13

MANAGING RESISTANCE TO CHANGE

RtC can be a significant factor in the success or failure of the change process. Poorly managed change can exponentially increase resistance, necessitating a multifaceted approach to managing RtC, while well-managed change can result in a high success rate. Evidence-based strategies to counter RtC focus on communication, employee participation, education and training, and engaging managers.8

Communication

Open and effective communication is critical to managing RtC, as uncertainty often exaggerates the negative aspects of change. Effective communication involves active listening, with leadership and management addressing employee concerns in a clear and concise manner. A psychologically safe culture for open dialogue is essential when addressing RtC.9,14,15 Psychological safety empowers staff to speak up, ask questions, and offer ideas, forming a solid basis for open and effective communication and participation. Leaders and managers should create opportunities for open dialogue for all members of the organization throughout the process. This can be accomplished with one-on-one meetings, open forums, town hall meetings, electronic mail, newsletters, and social media. Topics should cover the reasons for change, details of what is changing, the individual, organizational, and patient risks of not changing, as well as the benefits of changing.9 Encouraging staff to ask questions and provide feedback to promote bidirectional and closed-loop communication is essential to avoid misunderstandings.9,15 While open communication is essential, leaders must carefully plan what information to share, how much to share, and how to avoid information overload. Information about the change should be timely, adequate, applicable, and informative.15 The HRO practice of leader rounding for high reliability can be instrumental to ensure effective, bidirectional communication and collaboration among all disciplines across a health care organization through improving leadership visibility during times of change and enhancing interactions and communication with staff.3

Employee Participation

Involving staff in the change process significantly reduces RtC. Engagement fosters ownership in the change process, increasing the likelihood employees will support and even champion it. Health care professionals welcome opportunities to be involved in helping with aspects of organizational change, especially when invited to participate in the change early in the process and throughout the course of change.7,14,15

Leaders should encourage staff to provide feedback to understand the impact the change is having on them and their roles and responsibilities within the organization. This exemplifies the HRO principle of deference to expertise as the employee often has the most in-depth knowledge of their work setting. Employee perspectives can significantly influence the success of change initatives.7,14 Participation is impactful in providing employees with a sense of agency facilitating acceptance and improving desire to adopt the change.14

Tiered safety huddles and visual management systems (VMSs) also can engage staff. Tiered safety huddles provide a forum for transparent communication, increasing situational awareness, and improving a health care organization’s ability to appropriately respond to staff questions, suggestions, and concerns. VMSs display the status and progress toward organizational goals during the change process, and are highly effective in creating environments where staff feel empowered to voice concerns related to the change process.3

Education and Training

Educating employees on the value of change is crucial to overcome RtC. RtC often stems from employees not feeling prepared to adapt or adopt new processes. Health care professionals who do not receive information about change are less likely to support it.7,12,15 Staff are more likely to accept change when they understand why it is needed and how it impacts the organization’s long-term mission.11,15 Timely, compelling, and informative education on how to adapt to the change will promote more positive appraisal of the change and reduce RtC.8,15 Employees must feel confident they will receive the appropriate training, resources, and support to successfully adapt to the change. This requires leaders and managers taking time to clarify expectations, conduct a gap analysis to identify the skills and knowledge needed to support the planned change, and provide sufficient educational opportunities to fill those gaps.8 For example, the US Department of Veterans Affairs offers classes to employees on the Prosci ADKAR (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) Model. This training provides individuals with the information and skills needed for change to be successful.16

Safety forums can be influential and allow leadership to educate staff on updates related to change processes and promote bidirectional communication.3 In safety forums, staff have an opportunity to ask questions, especially as they relate to learning about available resources to become more informed about the organizational changes.

Engaging Managers

Managers are pivotal to the successful implementation of organizational change.8 They serve as the bridge between senior leadership and frontline employees and are positioned to influence the adoption and success of change initiatives. Often the first point of contact for employees, managers can effectively communicate the need for change, and act as the liaison to align it with individual employee motivations. Since they are often the first to encounter resistance among employees, managers serve as advocates through the process. Through a coaching role, managers can help employees develop the knowledge and ability to be successful and thrive in the new environment. The Table summarizes the evidence-based strategies.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementing change in health care organizations can be challenging, especially on the journey to high reliability. RtC is the result of factors at the individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels that leaders must address to increase chances for success. Organizational changes in health care are more likely to succeed when staff understand why the change is needed through open and continuous communication, can influence the change by sharing their own perspectives, and have the knowledge, skills, and resources to prepare for and participate in the process.

- Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Dealing-Perez C, et al. A high-reliability organization mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37:504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

- Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D, et al. Implementing high-reliability organization principles into practice: a rapid evidence review. J Patient Saf. 2022;18:e320-e328. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000768

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, et al. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41:214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Ford J, Isaacks DB, Anderson T. Creating, executing and sustaining a high-reliability organization in health care. The Learning Organization: An International Journal. 2024;31:817-833. doi:10.1108/TLO-03-2023-0048

- Cox GR, Starr LM. VHA’s movement for change: implementing high-reliability principles and practices. J Healthc Manag. 2023;68:151-157. doi:10.1097/JHM-D-00056

- Myers CG, Sutcliffe KM. High reliability organising in healthcare: still a long way left to go. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31:845-848. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014141

- Nilsen P, Seing I, Ericsson C, et al. Characteristics of successful changes in health care organizations: an interview study with physicians, registered nurses and assistant nurses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:147. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-4999-8

- Cheraghi R, Ebrahimi H, Kheibar N, et al. Reasons for resistance to change in nursing: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:310. doi:10/1186/s12912-023-01460-0

- Warrick DD. Revisiting resistance to change and how to manage it: what has been learned and what organizations need to do. Bus Horiz. 2023;66:433-441. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2022.09.001

- Sverdlik N, Oreg S. Beyond the individual-level conceptualization of dispositional resistance to change: multilevel effects on the response to organizational change. J Organ Behav. 2023;44:1066-1077. doi:10.1002/job.2678

- Khaw KW, Alnoor A, Al-Abrrow H, et al. Reactions towards organizational change: a systematic literature review. Curr Psychol. 2022;13:1-24. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03070-6

- Pomare C, Churruca K, Long JC, et al. Organisational change in hospitals: a qualitative case-study of staff perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:840. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4704-y

- DuBose BM, Mayo AM. RtC: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2020;55:631-636. doi:10.1111/nuf.12479

- Sahay S, Goldthwaite C. Participatory practices during organizational change: rethinking participation and resistance. Manag Commun Q. 2024;38(2):279-306. doi:10.1177/08933189231187883

- Damawan AH, Azizah S. Resistance to change: causes and strategies as an organizational challenge. ASSEHR. 2020;395(2020):49-53. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.200120.010

- Wong Q, Lacombe M, Keller R, et al. Leading change with ADKAR. Nurs Manage. 2019;50:28-35. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000554341.70508.75

- Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Dealing-Perez C, et al. A high-reliability organization mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37:504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

- Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D, et al. Implementing high-reliability organization principles into practice: a rapid evidence review. J Patient Saf. 2022;18:e320-e328. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000768

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, et al. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41:214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Ford J, Isaacks DB, Anderson T. Creating, executing and sustaining a high-reliability organization in health care. The Learning Organization: An International Journal. 2024;31:817-833. doi:10.1108/TLO-03-2023-0048

- Cox GR, Starr LM. VHA’s movement for change: implementing high-reliability principles and practices. J Healthc Manag. 2023;68:151-157. doi:10.1097/JHM-D-00056

- Myers CG, Sutcliffe KM. High reliability organising in healthcare: still a long way left to go. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31:845-848. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014141

- Nilsen P, Seing I, Ericsson C, et al. Characteristics of successful changes in health care organizations: an interview study with physicians, registered nurses and assistant nurses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:147. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-4999-8

- Cheraghi R, Ebrahimi H, Kheibar N, et al. Reasons for resistance to change in nursing: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:310. doi:10/1186/s12912-023-01460-0

- Warrick DD. Revisiting resistance to change and how to manage it: what has been learned and what organizations need to do. Bus Horiz. 2023;66:433-441. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2022.09.001

- Sverdlik N, Oreg S. Beyond the individual-level conceptualization of dispositional resistance to change: multilevel effects on the response to organizational change. J Organ Behav. 2023;44:1066-1077. doi:10.1002/job.2678

- Khaw KW, Alnoor A, Al-Abrrow H, et al. Reactions towards organizational change: a systematic literature review. Curr Psychol. 2022;13:1-24. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03070-6

- Pomare C, Churruca K, Long JC, et al. Organisational change in hospitals: a qualitative case-study of staff perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:840. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4704-y

- DuBose BM, Mayo AM. RtC: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2020;55:631-636. doi:10.1111/nuf.12479

- Sahay S, Goldthwaite C. Participatory practices during organizational change: rethinking participation and resistance. Manag Commun Q. 2024;38(2):279-306. doi:10.1177/08933189231187883

- Damawan AH, Azizah S. Resistance to change: causes and strategies as an organizational challenge. ASSEHR. 2020;395(2020):49-53. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.200120.010

- Wong Q, Lacombe M, Keller R, et al. Leading change with ADKAR. Nurs Manage. 2019;50:28-35. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000554341.70508.75

Managing Resistance to Change Along the Journey to High Reliability

Managing Resistance to Change Along the Journey to High Reliability

Achieving Psychological Safety in High Reliability Organizations

Achieving Psychological Safety in High Reliability Organizations

Worldwide, health care is becoming increasingly complex as a result of greater clinical workforce demands, expanded roles and responsibilities, health care system mergers, stakeholder calls for new capabilities, and digital transformation. 1,2These increasing demands has prompted many health care institutions to place greater focus on the psychological safety of their workforce, particularly in high reliability organizations (HROs). Building a robust foundation for high reliability in health care requires the presence of psychological safety—that is, staff members at all levels of the organization must feel comfortable speaking up when they have questions or concerns.3,4 Psychological safety can improve the safety and quality of patient care but has not reached its full potential in health care.5,6 However, there are strategies that promote the widespread implementation of psychological safety in health care organizations.3-6

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

The concept of psychological safety in organizational behavior originated in 1965 when Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis, leaders in organizational psychology and management, published their reflections on the importance of psychological safety in helping individuals feel secure in the work environment.5-7 Psychological safety in the workplace is foundational to staff members feeling comfortable asking questions or expressing concerns without fear of negative consequences.8,9 It supports both individual and team efforts to raise safety concerns and report near misses and adverse events so that similar events can be averted in the future.9 Patients aren’t the only ones who benefit; psychological safety has also been found to promote job satisfaction and employee well-being.10

THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION JOURNEY

Achieving psychological safety is by no means an easy or comfortable process. As with any organizational change, a multipronged approach offers the best chance of success.6,9 When the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) began its incremental, enterprise-wide journey to high reliability in 2019, 3 cohorts were identified. In February 2019, 18 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (cohort 1) began the process of becoming HROs. Cohort 2 followed in October 2020 and included 54 VAMC. Finally, in October 2021, 67 additional VAMCs (cohort 3) started the process.2 During cohort 2, the VA Providence Healthcare System (VAPHCS) decided to emphasize psychological safety at the start of the journey to becoming an HRO. This system is part of the VA New England Healthcare System (VISN 1), which includes VAMCs and clinics in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.11 Soon thereafter, the VA Bedford Healthcare System and the VA Connecticut Healthcare System adopted similar strategies. Since then, other VAMCs have also adopted this approach. These collective experiences identified 4 useful strategies for achieving psychological safety: leadership engagement, open communication, education and training, and accountability.

Leadership Engagement

Health care organization leaders play a critical role in making psychological safety happen—especially in complex and constantly changing environments, such as HROs.4 Leaders behaviors are consistently linked to the perception of psychological safety at the individual, team, and organizational levels.8 It is especially important to have leaders who recognize the views of individuals and team members and encourage staff participation in discussions to gain additional perspectives.7,8,12 Psychological safety can also be facilitated when leaders are visible, approachable, and communicative.4,7-9

Organizational practices, policies, and processes (eg, reporting adverse events without the fear of negative consequences) are also important ways that leaders can establish and sustain psychological safety. On a more granular level, leaders can enhance psychological safety by promoting and acknowledging individuals who speak up, regularly asking staff about safety concerns, highlighting “good catches” when harm is avoided, and using staff feedback to initiate improvements.4,7,13Finally, in the authors’ experience, psychological safety requires clear commitment from leaders at all levels of an organization. Communication should be bidirectional, and leaders should close the proverbial “loop” with feedback and timely follow-up. This encourages and reinforces staff engagement and speaking up behaviors.2,4,7,13

Open Communication

Promoting an environment of open communication, where all individuals and teams feel empowered to speak up with questions, concerns, and recommendations—regardless of position within the organization—is critical to psychological safety.4,6,9 Open communication is especially critical when processes and systems are constantly changing and advancing as a result of new information and technology.9 Promoting open, bidirectional communication during the delivery of patient care can be accomplished with huddles, tiered safety huddles, leader rounding for high reliability, and time-outs.2,4,6 These opportunities allow team members to discuss concerns, identify resources that support safe, high-quality care; reflect on successes and opportunities for improvement; and circle back on concerns.2,6 Open communication in psychologically safe environments empowers staff to raise patient care concerns and is instrumental for improving patient safety, increasing staff job satisfaction, and decreasing turnover.6,14

Education and Training

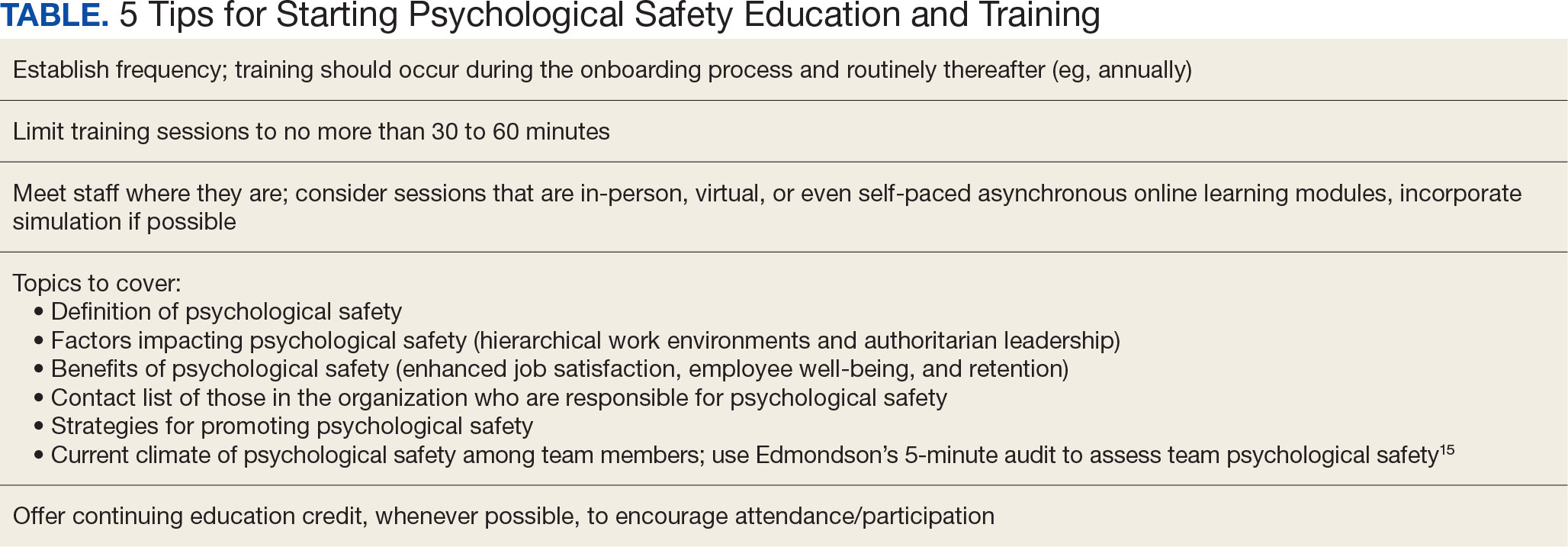

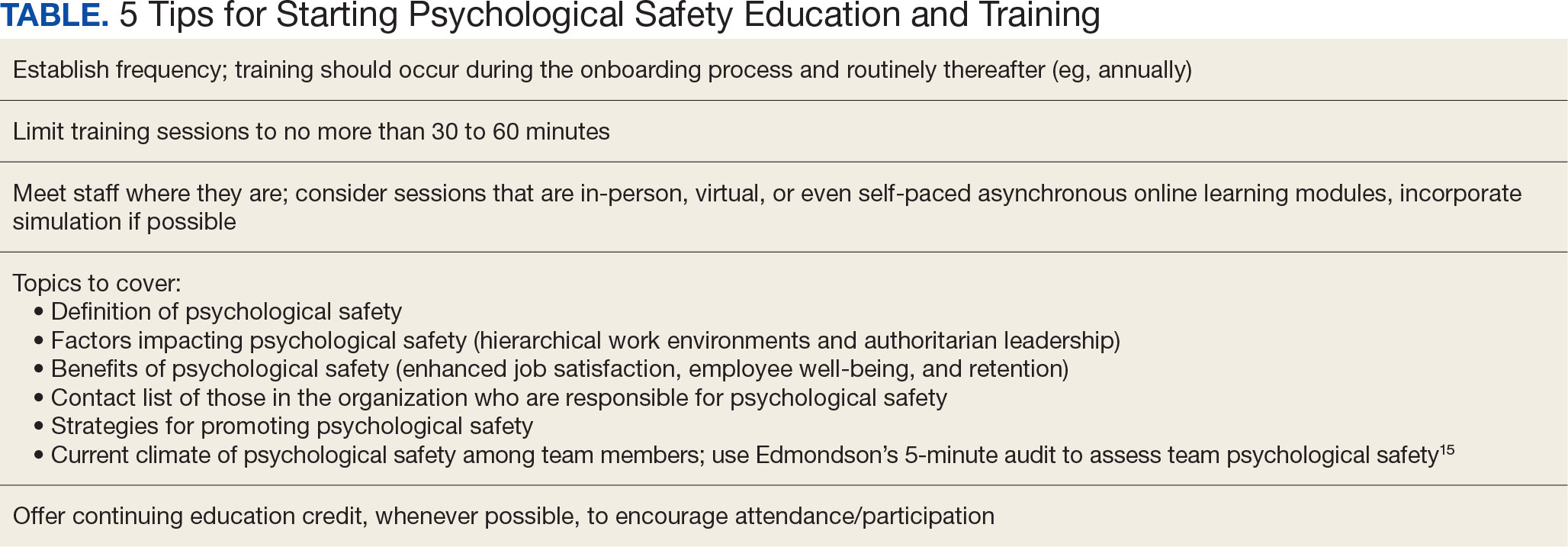

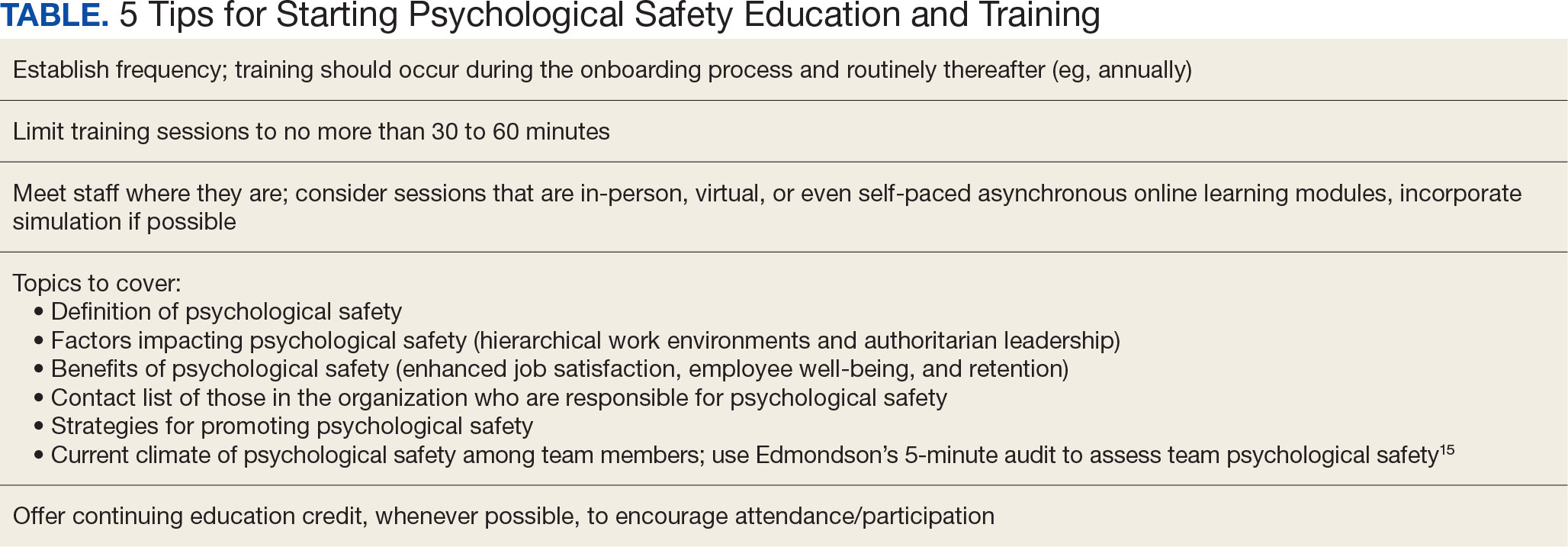

Education and training for all staff—from the frontline to the executive level—are essential to successfully implementing the principles and practices of psychological safety.5-7 VHA training covers many topics, including the origins, benefits, and implementation strategies of psychological safety (Table). Role-playing simulation is an effective teaching format, providing staff with opportunities to practice techniques for raising concerns or share feedback in a controlled environment.6 In addition, education should be ongoing; it helps leaders and staff members feel competent and confident when implementing psychological safety across the health care organization.6,10

Accountability

The final critical strategy for achieving psychological safety is accountability. It is the responsibility of all leadership—from senior leaders to clinical and nonclinical managers—to create a culture of shared accountability.5 But first, expectations must be set. Leadership must establish well-defined behavioral expectations that align with the organization’s values. Understanding behavioral expectations will help to ensure that employees know what achievement looks like, as well as how they are being held accountable for their individual actions.4,5,7 In practical terms, this means ensuring that staff members have the skills and resources to achieve goals and expectations, providing performance feedback in a timely manner, and including expectations in annual performance evaluations (as they are in the VHA).

Consistency is key. Accountability should be the expectation across all levels and services of the health care organization. No staff member should be exempt from promoting a psychologically safe work environment. Compliance with behavioral expectations should be monitored and if a person’s actions are not consistent with expectations, the situation will need to be addressed. Interventions will depend on the type, severity, and frequency of the problematic behaviors. Depending on an organization’s policies and practices, courses of action can range from feedback counseling to employment termination.5

A practical matter in ensuring accountability is implementing a psychologically safe process for reporting concerns. Staff members must feel comfortable reporting behavioral concerns without fear of retaliation, negative judgment, or consequences from peers and supervisors. One method for doing this is to create a confidential, centralized process for reporting concerns.5

First-Hand Results

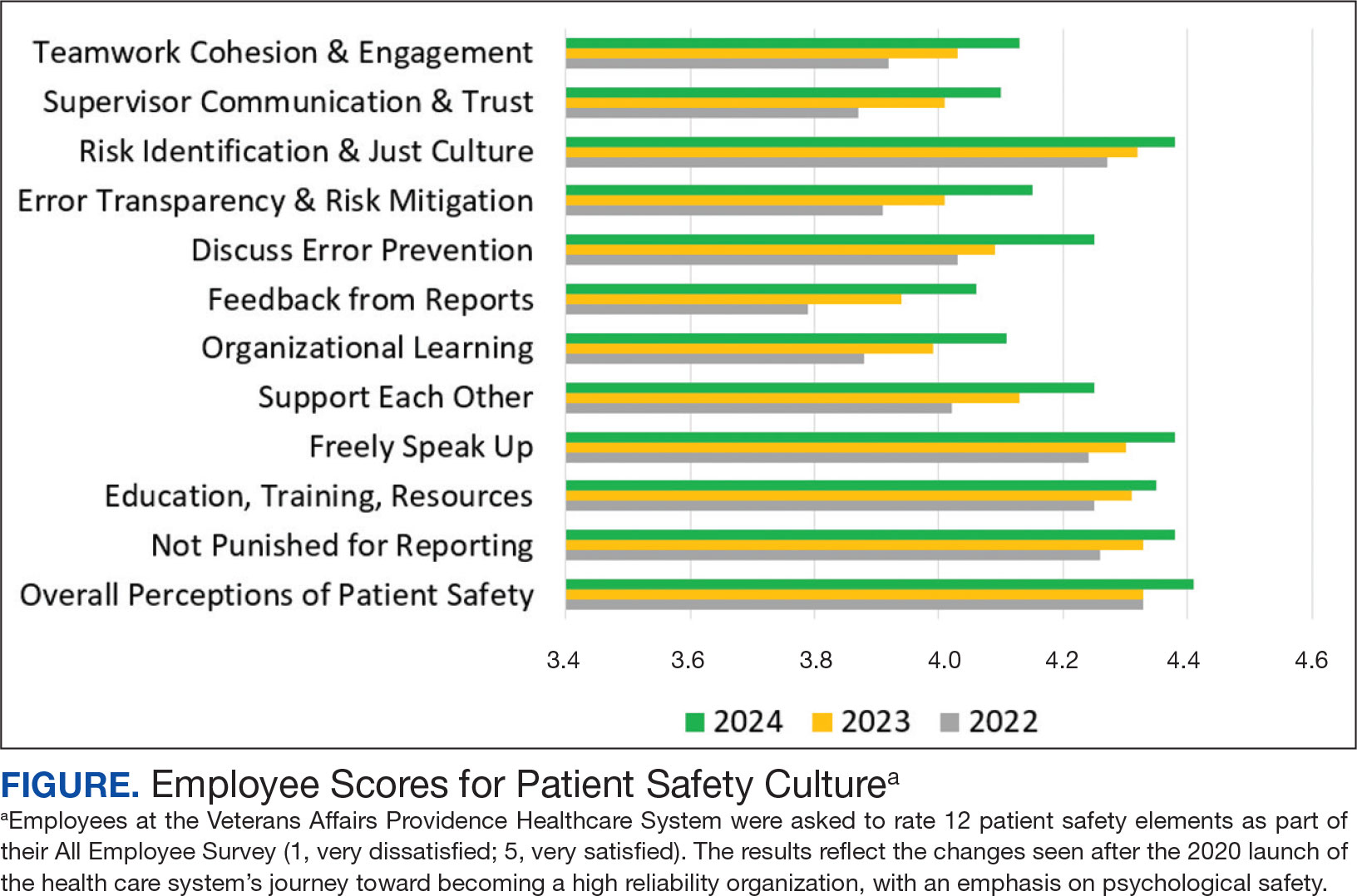

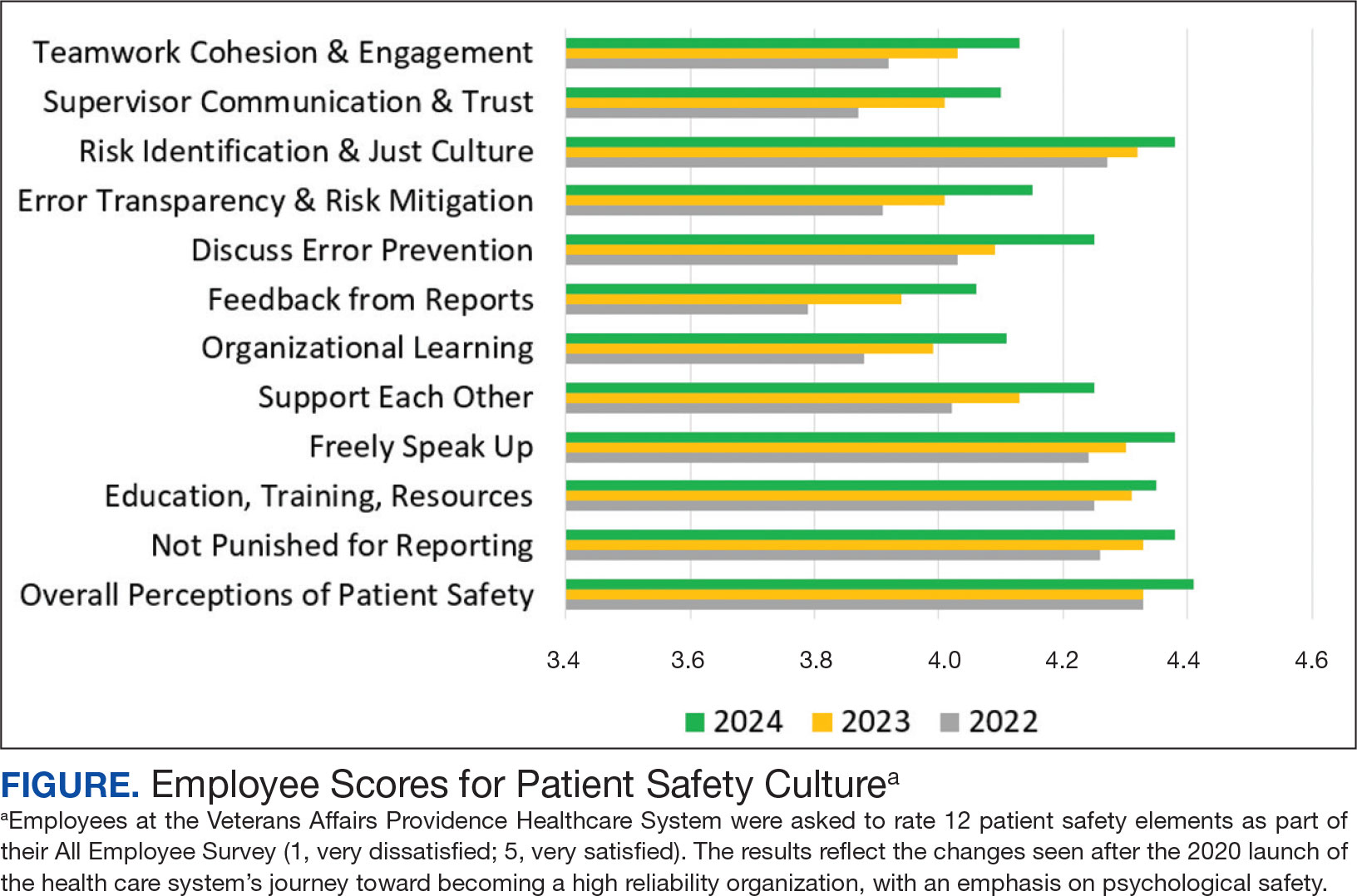

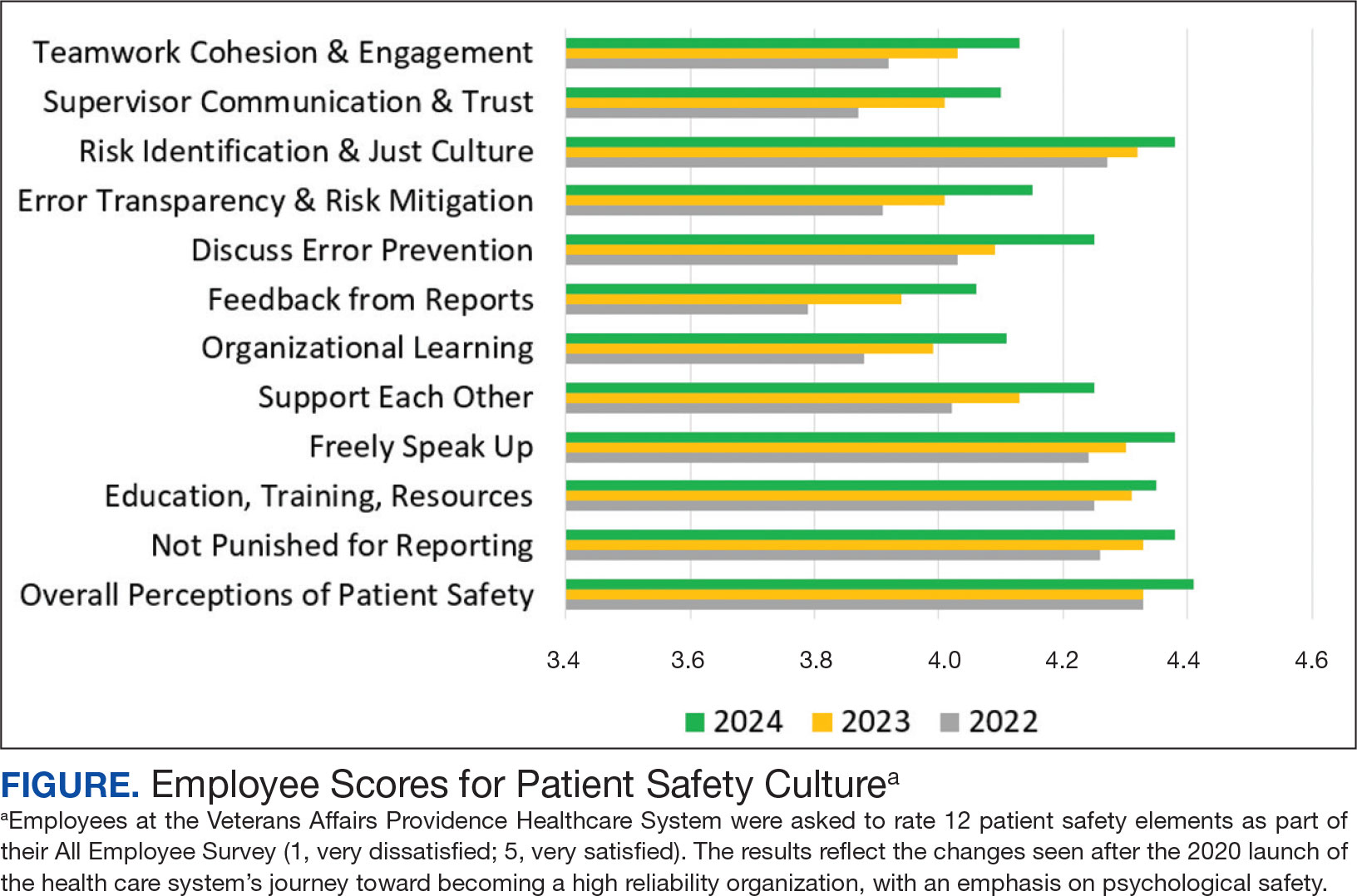

VAPHCS has seen the results of implementing the strategies outlined here. For example, VAPHCS has observed a 45% increase in the use of the patient safety reporting system that logs medical errors and near-misses. In addition, there have been improvements in levels of psychological safety and patient safety reported in the annual VHA All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually to gauge workplace satisfaction, culture, climate, turnover, supervisory behaviors, and general workplace perceptions. VAPHCS has shown consistent improvements in 12 patient safety elements scored on a 5-point scale (1, very dissatisfied; 5, very satisfied) (Figure). Notably, employee ratings of error prevention discussed increased from 4.0 in 2022 to 4.3 in 2024. Data collection and analysis are ongoing; more comprehensive findings will be published in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Health care organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of psychologically safe workplaces in order to provide safe, high-quality patient care. Psychological safety is a critical tool for empowering staff to raise concerns, ask tough questions, challenge the status quo, and share new ideas for providing health care services. While psychological safety has been slowly adopted in health care, it’s clear that evidence-based strategies can make psychological safety a reality.

- Spanos S, Leask E, Patel R, Datyner M, Loh E, Braithwaite J. Healthcare leaders navigating complexity: A scoping review of key trends in future roles and competencies. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):720. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05689-4

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, Crews P, Walsh ND. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41(7):214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Bransby DP, Kerrissey M, Edmondson AC. Paradise lost (and restored?): a study of psychological safety over time. Acad Manag Discov. Published online March 14, 2024. doi:10.5465/amd.2023.0084

- Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

- Jamal N, Young VN, Shapiro J, Brenner MJ, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, part IV: Psychological safety-drivers to outcomes and well-being. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(4):881-888. doi:10.1177/01945998221126966

- Sarofim M. Psychological safety in medicine: What is it, and who cares? Med J Aust. 2024;220(8):398-399. doi:10.5694/mja2.52263

- Edmondson AC, Bransby DP. Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2023;10:55-78. doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-055217

- Kumar S. Psychological safety: What it is, why teams need it, and how to make it flourish. Chest. 2024; 165(4):942-949. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.016

- Hallam KT, Popovic N, Karimi L. Identifying the key elements of psychologically safe workplaces in healthcare settings. Brain Sci. 2023;13(10):1450. doi:10.3390/brainsci13101450

- Grailey KE, Murray E, Reader T, Brett SJ. The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: an evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):773. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06740-6

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VISN 1: VA New England Healthcare System. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-01

- Brimhall KC, Tsai CY, Eckardt R, Dionne S, Yang B, Sharp A. The effects of leadership for self-worth, inclusion, trust, and psychological safety on medical error reporting. Health Care Manage Rev. 2023;48(2):120-129. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000358

- Adair KC, Heath A, Frye MA, et al. The Psychological Safety Scale of the Safety, Communication, Operational, Reliability, and Engagement (SCORE) Survey: a brief, diagnostic, and actionable metric for the ability to speak up in healthcare settings. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(6):513-520. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001048

- Cho H, Steege LM, Arsenault Knudsen ÉN. Psychological safety, communication openness, nurse job outcomes, and patient safety in hospital nurses. Res Nurs Health. 2023;46(4):445-453.

- Practical Tool 2: 5 minute psychological safety audit. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/jlnf3cju/practical-tool-2-psychological-safety-audit.pdf

Worldwide, health care is becoming increasingly complex as a result of greater clinical workforce demands, expanded roles and responsibilities, health care system mergers, stakeholder calls for new capabilities, and digital transformation. 1,2These increasing demands has prompted many health care institutions to place greater focus on the psychological safety of their workforce, particularly in high reliability organizations (HROs). Building a robust foundation for high reliability in health care requires the presence of psychological safety—that is, staff members at all levels of the organization must feel comfortable speaking up when they have questions or concerns.3,4 Psychological safety can improve the safety and quality of patient care but has not reached its full potential in health care.5,6 However, there are strategies that promote the widespread implementation of psychological safety in health care organizations.3-6

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

The concept of psychological safety in organizational behavior originated in 1965 when Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis, leaders in organizational psychology and management, published their reflections on the importance of psychological safety in helping individuals feel secure in the work environment.5-7 Psychological safety in the workplace is foundational to staff members feeling comfortable asking questions or expressing concerns without fear of negative consequences.8,9 It supports both individual and team efforts to raise safety concerns and report near misses and adverse events so that similar events can be averted in the future.9 Patients aren’t the only ones who benefit; psychological safety has also been found to promote job satisfaction and employee well-being.10

THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION JOURNEY

Achieving psychological safety is by no means an easy or comfortable process. As with any organizational change, a multipronged approach offers the best chance of success.6,9 When the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) began its incremental, enterprise-wide journey to high reliability in 2019, 3 cohorts were identified. In February 2019, 18 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (cohort 1) began the process of becoming HROs. Cohort 2 followed in October 2020 and included 54 VAMC. Finally, in October 2021, 67 additional VAMCs (cohort 3) started the process.2 During cohort 2, the VA Providence Healthcare System (VAPHCS) decided to emphasize psychological safety at the start of the journey to becoming an HRO. This system is part of the VA New England Healthcare System (VISN 1), which includes VAMCs and clinics in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.11 Soon thereafter, the VA Bedford Healthcare System and the VA Connecticut Healthcare System adopted similar strategies. Since then, other VAMCs have also adopted this approach. These collective experiences identified 4 useful strategies for achieving psychological safety: leadership engagement, open communication, education and training, and accountability.

Leadership Engagement

Health care organization leaders play a critical role in making psychological safety happen—especially in complex and constantly changing environments, such as HROs.4 Leaders behaviors are consistently linked to the perception of psychological safety at the individual, team, and organizational levels.8 It is especially important to have leaders who recognize the views of individuals and team members and encourage staff participation in discussions to gain additional perspectives.7,8,12 Psychological safety can also be facilitated when leaders are visible, approachable, and communicative.4,7-9

Organizational practices, policies, and processes (eg, reporting adverse events without the fear of negative consequences) are also important ways that leaders can establish and sustain psychological safety. On a more granular level, leaders can enhance psychological safety by promoting and acknowledging individuals who speak up, regularly asking staff about safety concerns, highlighting “good catches” when harm is avoided, and using staff feedback to initiate improvements.4,7,13Finally, in the authors’ experience, psychological safety requires clear commitment from leaders at all levels of an organization. Communication should be bidirectional, and leaders should close the proverbial “loop” with feedback and timely follow-up. This encourages and reinforces staff engagement and speaking up behaviors.2,4,7,13

Open Communication

Promoting an environment of open communication, where all individuals and teams feel empowered to speak up with questions, concerns, and recommendations—regardless of position within the organization—is critical to psychological safety.4,6,9 Open communication is especially critical when processes and systems are constantly changing and advancing as a result of new information and technology.9 Promoting open, bidirectional communication during the delivery of patient care can be accomplished with huddles, tiered safety huddles, leader rounding for high reliability, and time-outs.2,4,6 These opportunities allow team members to discuss concerns, identify resources that support safe, high-quality care; reflect on successes and opportunities for improvement; and circle back on concerns.2,6 Open communication in psychologically safe environments empowers staff to raise patient care concerns and is instrumental for improving patient safety, increasing staff job satisfaction, and decreasing turnover.6,14

Education and Training

Education and training for all staff—from the frontline to the executive level—are essential to successfully implementing the principles and practices of psychological safety.5-7 VHA training covers many topics, including the origins, benefits, and implementation strategies of psychological safety (Table). Role-playing simulation is an effective teaching format, providing staff with opportunities to practice techniques for raising concerns or share feedback in a controlled environment.6 In addition, education should be ongoing; it helps leaders and staff members feel competent and confident when implementing psychological safety across the health care organization.6,10

Accountability

The final critical strategy for achieving psychological safety is accountability. It is the responsibility of all leadership—from senior leaders to clinical and nonclinical managers—to create a culture of shared accountability.5 But first, expectations must be set. Leadership must establish well-defined behavioral expectations that align with the organization’s values. Understanding behavioral expectations will help to ensure that employees know what achievement looks like, as well as how they are being held accountable for their individual actions.4,5,7 In practical terms, this means ensuring that staff members have the skills and resources to achieve goals and expectations, providing performance feedback in a timely manner, and including expectations in annual performance evaluations (as they are in the VHA).

Consistency is key. Accountability should be the expectation across all levels and services of the health care organization. No staff member should be exempt from promoting a psychologically safe work environment. Compliance with behavioral expectations should be monitored and if a person’s actions are not consistent with expectations, the situation will need to be addressed. Interventions will depend on the type, severity, and frequency of the problematic behaviors. Depending on an organization’s policies and practices, courses of action can range from feedback counseling to employment termination.5

A practical matter in ensuring accountability is implementing a psychologically safe process for reporting concerns. Staff members must feel comfortable reporting behavioral concerns without fear of retaliation, negative judgment, or consequences from peers and supervisors. One method for doing this is to create a confidential, centralized process for reporting concerns.5

First-Hand Results

VAPHCS has seen the results of implementing the strategies outlined here. For example, VAPHCS has observed a 45% increase in the use of the patient safety reporting system that logs medical errors and near-misses. In addition, there have been improvements in levels of psychological safety and patient safety reported in the annual VHA All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually to gauge workplace satisfaction, culture, climate, turnover, supervisory behaviors, and general workplace perceptions. VAPHCS has shown consistent improvements in 12 patient safety elements scored on a 5-point scale (1, very dissatisfied; 5, very satisfied) (Figure). Notably, employee ratings of error prevention discussed increased from 4.0 in 2022 to 4.3 in 2024. Data collection and analysis are ongoing; more comprehensive findings will be published in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Health care organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of psychologically safe workplaces in order to provide safe, high-quality patient care. Psychological safety is a critical tool for empowering staff to raise concerns, ask tough questions, challenge the status quo, and share new ideas for providing health care services. While psychological safety has been slowly adopted in health care, it’s clear that evidence-based strategies can make psychological safety a reality.

Worldwide, health care is becoming increasingly complex as a result of greater clinical workforce demands, expanded roles and responsibilities, health care system mergers, stakeholder calls for new capabilities, and digital transformation. 1,2These increasing demands has prompted many health care institutions to place greater focus on the psychological safety of their workforce, particularly in high reliability organizations (HROs). Building a robust foundation for high reliability in health care requires the presence of psychological safety—that is, staff members at all levels of the organization must feel comfortable speaking up when they have questions or concerns.3,4 Psychological safety can improve the safety and quality of patient care but has not reached its full potential in health care.5,6 However, there are strategies that promote the widespread implementation of psychological safety in health care organizations.3-6

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

The concept of psychological safety in organizational behavior originated in 1965 when Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis, leaders in organizational psychology and management, published their reflections on the importance of psychological safety in helping individuals feel secure in the work environment.5-7 Psychological safety in the workplace is foundational to staff members feeling comfortable asking questions or expressing concerns without fear of negative consequences.8,9 It supports both individual and team efforts to raise safety concerns and report near misses and adverse events so that similar events can be averted in the future.9 Patients aren’t the only ones who benefit; psychological safety has also been found to promote job satisfaction and employee well-being.10

THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION JOURNEY

Achieving psychological safety is by no means an easy or comfortable process. As with any organizational change, a multipronged approach offers the best chance of success.6,9 When the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) began its incremental, enterprise-wide journey to high reliability in 2019, 3 cohorts were identified. In February 2019, 18 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (cohort 1) began the process of becoming HROs. Cohort 2 followed in October 2020 and included 54 VAMC. Finally, in October 2021, 67 additional VAMCs (cohort 3) started the process.2 During cohort 2, the VA Providence Healthcare System (VAPHCS) decided to emphasize psychological safety at the start of the journey to becoming an HRO. This system is part of the VA New England Healthcare System (VISN 1), which includes VAMCs and clinics in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.11 Soon thereafter, the VA Bedford Healthcare System and the VA Connecticut Healthcare System adopted similar strategies. Since then, other VAMCs have also adopted this approach. These collective experiences identified 4 useful strategies for achieving psychological safety: leadership engagement, open communication, education and training, and accountability.

Leadership Engagement

Health care organization leaders play a critical role in making psychological safety happen—especially in complex and constantly changing environments, such as HROs.4 Leaders behaviors are consistently linked to the perception of psychological safety at the individual, team, and organizational levels.8 It is especially important to have leaders who recognize the views of individuals and team members and encourage staff participation in discussions to gain additional perspectives.7,8,12 Psychological safety can also be facilitated when leaders are visible, approachable, and communicative.4,7-9

Organizational practices, policies, and processes (eg, reporting adverse events without the fear of negative consequences) are also important ways that leaders can establish and sustain psychological safety. On a more granular level, leaders can enhance psychological safety by promoting and acknowledging individuals who speak up, regularly asking staff about safety concerns, highlighting “good catches” when harm is avoided, and using staff feedback to initiate improvements.4,7,13Finally, in the authors’ experience, psychological safety requires clear commitment from leaders at all levels of an organization. Communication should be bidirectional, and leaders should close the proverbial “loop” with feedback and timely follow-up. This encourages and reinforces staff engagement and speaking up behaviors.2,4,7,13

Open Communication

Promoting an environment of open communication, where all individuals and teams feel empowered to speak up with questions, concerns, and recommendations—regardless of position within the organization—is critical to psychological safety.4,6,9 Open communication is especially critical when processes and systems are constantly changing and advancing as a result of new information and technology.9 Promoting open, bidirectional communication during the delivery of patient care can be accomplished with huddles, tiered safety huddles, leader rounding for high reliability, and time-outs.2,4,6 These opportunities allow team members to discuss concerns, identify resources that support safe, high-quality care; reflect on successes and opportunities for improvement; and circle back on concerns.2,6 Open communication in psychologically safe environments empowers staff to raise patient care concerns and is instrumental for improving patient safety, increasing staff job satisfaction, and decreasing turnover.6,14

Education and Training

Education and training for all staff—from the frontline to the executive level—are essential to successfully implementing the principles and practices of psychological safety.5-7 VHA training covers many topics, including the origins, benefits, and implementation strategies of psychological safety (Table). Role-playing simulation is an effective teaching format, providing staff with opportunities to practice techniques for raising concerns or share feedback in a controlled environment.6 In addition, education should be ongoing; it helps leaders and staff members feel competent and confident when implementing psychological safety across the health care organization.6,10

Accountability

The final critical strategy for achieving psychological safety is accountability. It is the responsibility of all leadership—from senior leaders to clinical and nonclinical managers—to create a culture of shared accountability.5 But first, expectations must be set. Leadership must establish well-defined behavioral expectations that align with the organization’s values. Understanding behavioral expectations will help to ensure that employees know what achievement looks like, as well as how they are being held accountable for their individual actions.4,5,7 In practical terms, this means ensuring that staff members have the skills and resources to achieve goals and expectations, providing performance feedback in a timely manner, and including expectations in annual performance evaluations (as they are in the VHA).

Consistency is key. Accountability should be the expectation across all levels and services of the health care organization. No staff member should be exempt from promoting a psychologically safe work environment. Compliance with behavioral expectations should be monitored and if a person’s actions are not consistent with expectations, the situation will need to be addressed. Interventions will depend on the type, severity, and frequency of the problematic behaviors. Depending on an organization’s policies and practices, courses of action can range from feedback counseling to employment termination.5

A practical matter in ensuring accountability is implementing a psychologically safe process for reporting concerns. Staff members must feel comfortable reporting behavioral concerns without fear of retaliation, negative judgment, or consequences from peers and supervisors. One method for doing this is to create a confidential, centralized process for reporting concerns.5

First-Hand Results

VAPHCS has seen the results of implementing the strategies outlined here. For example, VAPHCS has observed a 45% increase in the use of the patient safety reporting system that logs medical errors and near-misses. In addition, there have been improvements in levels of psychological safety and patient safety reported in the annual VHA All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually to gauge workplace satisfaction, culture, climate, turnover, supervisory behaviors, and general workplace perceptions. VAPHCS has shown consistent improvements in 12 patient safety elements scored on a 5-point scale (1, very dissatisfied; 5, very satisfied) (Figure). Notably, employee ratings of error prevention discussed increased from 4.0 in 2022 to 4.3 in 2024. Data collection and analysis are ongoing; more comprehensive findings will be published in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Health care organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of psychologically safe workplaces in order to provide safe, high-quality patient care. Psychological safety is a critical tool for empowering staff to raise concerns, ask tough questions, challenge the status quo, and share new ideas for providing health care services. While psychological safety has been slowly adopted in health care, it’s clear that evidence-based strategies can make psychological safety a reality.

- Spanos S, Leask E, Patel R, Datyner M, Loh E, Braithwaite J. Healthcare leaders navigating complexity: A scoping review of key trends in future roles and competencies. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):720. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05689-4

- Murray JS, Baghdadi A, Dannenberg W, Crews P, Walsh ND. The role of high reliability organization foundational practices in building a culture of safety. Fed Pract. 2024;41(7):214-221. doi:10.12788/fp.0486

- Bransby DP, Kerrissey M, Edmondson AC. Paradise lost (and restored?): a study of psychological safety over time. Acad Manag Discov. Published online March 14, 2024. doi:10.5465/amd.2023.0084

- Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

- Jamal N, Young VN, Shapiro J, Brenner MJ, Schmalbach CE. Patient safety/quality improvement primer, part IV: Psychological safety-drivers to outcomes and well-being. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(4):881-888. doi:10.1177/01945998221126966

- Sarofim M. Psychological safety in medicine: What is it, and who cares? Med J Aust. 2024;220(8):398-399. doi:10.5694/mja2.52263

- Edmondson AC, Bransby DP. Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2023;10:55-78. doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-055217

- Kumar S. Psychological safety: What it is, why teams need it, and how to make it flourish. Chest. 2024; 165(4):942-949. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.016

- Hallam KT, Popovic N, Karimi L. Identifying the key elements of psychologically safe workplaces in healthcare settings. Brain Sci. 2023;13(10):1450. doi:10.3390/brainsci13101450

- Grailey KE, Murray E, Reader T, Brett SJ. The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: an evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):773. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06740-6

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VISN 1: VA New England Healthcare System. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://department.va.gov/integrated-service-networks/visn-01

- Brimhall KC, Tsai CY, Eckardt R, Dionne S, Yang B, Sharp A. The effects of leadership for self-worth, inclusion, trust, and psychological safety on medical error reporting. Health Care Manage Rev. 2023;48(2):120-129. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000358

- Adair KC, Heath A, Frye MA, et al. The Psychological Safety Scale of the Safety, Communication, Operational, Reliability, and Engagement (SCORE) Survey: a brief, diagnostic, and actionable metric for the ability to speak up in healthcare settings. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(6):513-520. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001048