User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

United States reaches 5 million cases of child COVID

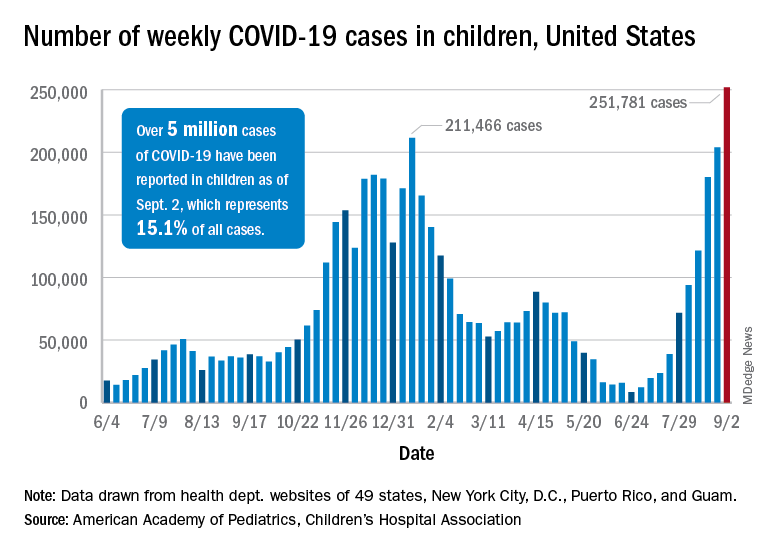

Cases of child COVID-19 set a new 1-week record and the total number of children infected during the pandemic passed 5 million, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The nearly 282,000 new cases reported in the United States during the week ending Sept. 2 broke the record of 211,000 set in mid-January and brought the cumulative count to 5,049,465 children with COVID-19 since the pandemic began, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Hospitalizations in children aged 0-17 years have also reached record levels in recent days. The highest daily admission rate since the pandemic began, 0.51 per 100,000 population, was recorded on Sept. 2, less than 2 months after the nation saw its lowest child COVID admission rate for 1 day: 0.07 per 100,000 on July 4. That’s an increase of 629%, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccinations in children, however, did not follow suit. New vaccinations in children aged 12-17 years dropped by 4.5% for the week ending Sept. 6, compared with the week before. Initiations were actually up almost 12% for children aged 16-17, but that was not enough to overcome the continued decline among 12- to 15-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the decline in new vaccinations, those younger children passed a noteworthy group milestone: 50.9% of all 12- to 15-year-olds now have received at least one dose, with 38.6% having completed the regimen. The 16- to 17-year-olds got an earlier start and have reached 58.9% coverage for one dose and 47.6% for two, the CDC said.

A total of 12.2 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Sept. 6, of whom almost 9.5 million are fully vaccinated, based on the CDC data.

At the state level, Vermont has the highest rates for vaccine initiation (75%) and full vaccination (65%), with Massachusetts (75%/62%) and Connecticut (73%/59%) just behind. The other end of the scale is occupied by Wyoming (28% initiation/19% full vaccination), Alabama (32%/19%), and North Dakota (32%/23%), the AAP said in a separate report.

In a recent letter to the Food and Drug Administration, AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, said that the “Delta variant is surging at extremely alarming rates in every region of America. This surge is seriously impacting all populations, including children.” Dr. Beers urged the FDA to work “aggressively toward authorizing safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for children under age 12 as soon as possible.”

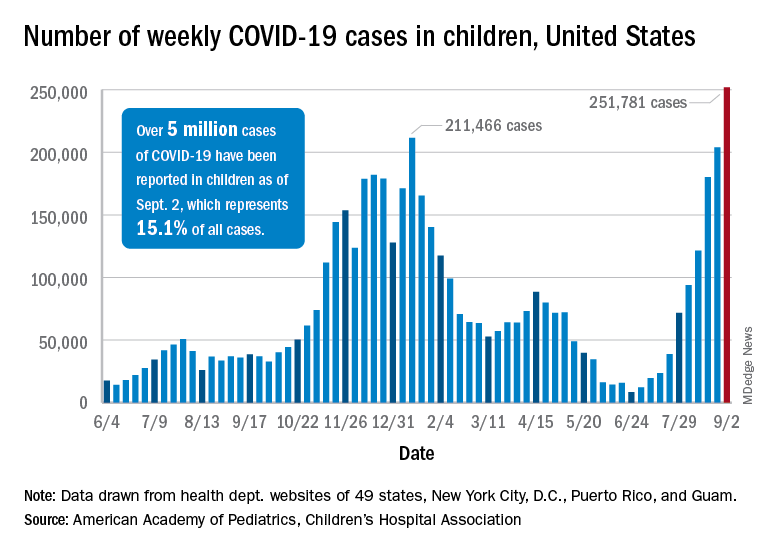

Cases of child COVID-19 set a new 1-week record and the total number of children infected during the pandemic passed 5 million, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The nearly 282,000 new cases reported in the United States during the week ending Sept. 2 broke the record of 211,000 set in mid-January and brought the cumulative count to 5,049,465 children with COVID-19 since the pandemic began, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Hospitalizations in children aged 0-17 years have also reached record levels in recent days. The highest daily admission rate since the pandemic began, 0.51 per 100,000 population, was recorded on Sept. 2, less than 2 months after the nation saw its lowest child COVID admission rate for 1 day: 0.07 per 100,000 on July 4. That’s an increase of 629%, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccinations in children, however, did not follow suit. New vaccinations in children aged 12-17 years dropped by 4.5% for the week ending Sept. 6, compared with the week before. Initiations were actually up almost 12% for children aged 16-17, but that was not enough to overcome the continued decline among 12- to 15-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the decline in new vaccinations, those younger children passed a noteworthy group milestone: 50.9% of all 12- to 15-year-olds now have received at least one dose, with 38.6% having completed the regimen. The 16- to 17-year-olds got an earlier start and have reached 58.9% coverage for one dose and 47.6% for two, the CDC said.

A total of 12.2 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Sept. 6, of whom almost 9.5 million are fully vaccinated, based on the CDC data.

At the state level, Vermont has the highest rates for vaccine initiation (75%) and full vaccination (65%), with Massachusetts (75%/62%) and Connecticut (73%/59%) just behind. The other end of the scale is occupied by Wyoming (28% initiation/19% full vaccination), Alabama (32%/19%), and North Dakota (32%/23%), the AAP said in a separate report.

In a recent letter to the Food and Drug Administration, AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, said that the “Delta variant is surging at extremely alarming rates in every region of America. This surge is seriously impacting all populations, including children.” Dr. Beers urged the FDA to work “aggressively toward authorizing safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for children under age 12 as soon as possible.”

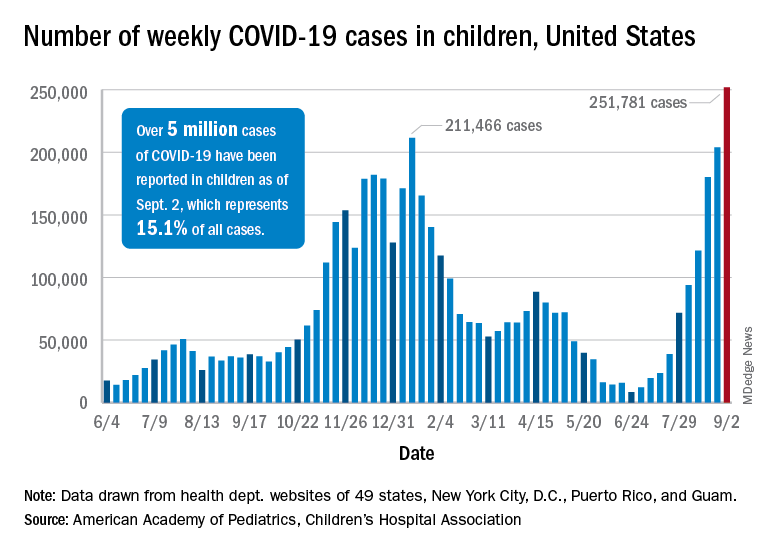

Cases of child COVID-19 set a new 1-week record and the total number of children infected during the pandemic passed 5 million, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The nearly 282,000 new cases reported in the United States during the week ending Sept. 2 broke the record of 211,000 set in mid-January and brought the cumulative count to 5,049,465 children with COVID-19 since the pandemic began, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Hospitalizations in children aged 0-17 years have also reached record levels in recent days. The highest daily admission rate since the pandemic began, 0.51 per 100,000 population, was recorded on Sept. 2, less than 2 months after the nation saw its lowest child COVID admission rate for 1 day: 0.07 per 100,000 on July 4. That’s an increase of 629%, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccinations in children, however, did not follow suit. New vaccinations in children aged 12-17 years dropped by 4.5% for the week ending Sept. 6, compared with the week before. Initiations were actually up almost 12% for children aged 16-17, but that was not enough to overcome the continued decline among 12- to 15-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the decline in new vaccinations, those younger children passed a noteworthy group milestone: 50.9% of all 12- to 15-year-olds now have received at least one dose, with 38.6% having completed the regimen. The 16- to 17-year-olds got an earlier start and have reached 58.9% coverage for one dose and 47.6% for two, the CDC said.

A total of 12.2 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Sept. 6, of whom almost 9.5 million are fully vaccinated, based on the CDC data.

At the state level, Vermont has the highest rates for vaccine initiation (75%) and full vaccination (65%), with Massachusetts (75%/62%) and Connecticut (73%/59%) just behind. The other end of the scale is occupied by Wyoming (28% initiation/19% full vaccination), Alabama (32%/19%), and North Dakota (32%/23%), the AAP said in a separate report.

In a recent letter to the Food and Drug Administration, AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, said that the “Delta variant is surging at extremely alarming rates in every region of America. This surge is seriously impacting all populations, including children.” Dr. Beers urged the FDA to work “aggressively toward authorizing safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for children under age 12 as soon as possible.”

COVID-19 continues to complicate children’s mental health care

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact child and adolescent mental health, and clinicians are learning as they go to develop strategies that address the challenges of providing both medical and mental health care to young patients, including those who test positive for COVID-19, according to Hani Talebi, PhD, director of pediatric psychology, and Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, director of pediatric hospital medicine, both of the University of Texas at Austin and Dell Children’s Medical Center.

In a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem shared their experiences in identifying the impact of the pandemic on mental health services in a freestanding hospital, and synthesizing inpatient mental health care and medical care outside of a dedicated mental health unit.

Mental health is a significant pediatric issue; approximately one in five children have a diagnosable mental or behavioral health problem, but nearly two-thirds get little or no help, Dr. Talebi said. “COVID-19 has only exacerbated these mental health challenges,” he said.

He noted that beginning in April 2020, the proportion of children’s mental health-related emergency department visits increased and remained elevated through the spring, summer, and fall of 2020, as families fearful of COVID-19 avoided regular hospital visits.

Data suggest that up to 50% of all adolescent psychiatric crises that led to inpatient admissions were related in some way to COVID-19, Dr. Talebi said. In addition, “individuals with a recent diagnosis of a mental health disorder are at increased risk for COVID-19 infection,” and the risk is even higher among women and African Americans, he said.

The past year significantly impacted the mental wellbeing of parents and children, Dr. Talebi said. He cited a June 2020 study in Pediatrics in which 27% of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health for their children. Ongoing issues including food insecurity, loss of regular child care, and an overall “very disorienting experience in the day-to-day” compromised the mental health of families, Dr. Talebi emphasized. Children isolated at home were not meeting developmental milestones that organically occur when socializing with peers, parents didn’t know how to handle some of their children’s issues without support from schools, and many people were struggling with other preexisting health conditions, he said.

This confluence of factors helped drive a surge in emergency department visits, meaning longer wait times and concerns about meeting urgent medical and mental health needs while maintaining safety, he added.

Parents and children waited longer to seek care, and community hospitals such as Dell Children’s Medical Center were faced with children in the emergency department with crisis-level mental health issues, along with children already waiting in the ED to address medical emergencies. All these patients had to be tested for COVID-19 and managed accordingly, Dr. Talebi noted.

Dr. Talebi emphasized the need for clinically robust care of the children who were in isolation for 10 days on the medical unit, waiting to test negative. New protocols were created for social workers to conduct daily safety checks, and to develop regular schedules for screening, “so they are having an experience on the medical floors similar to what they would have in a mental health unit,” he said.

Dr. Ganem reflected on the logistical challenges of managing mental health care while observing COVID-19 safety protocols. “COVID-19 added a new wrinkle of isolation,” he said. As institutional guidelines on testing and isolation evolved, negative COVID-19 tests were required for admission to the mental health units both in the hospital and throughout the region. Patients who tested positive had to be quarantined for 10 days, at which time they could be admitted to a mental health unit if necessary, he said.

Dr. Ganem shared details of some strategies adopted by Dell Children’s. He explained that the COVID-19 psychiatry patient workflow started with an ED evaluation, followed by medical clearance and consideration for admission.

“There was significant coordination between the social worker in the emergency department and the psychiatry social worker,” he said.

Key elements of the treatment plan for children with positive COVID-19 tests included an “interprofessional huddle” to coordinate the plan of care, goals for admission, and goals for safety, Dr. Ganem said.

Patients who required admission were expected to have an initial length of stay of 72 hours, and those who tested positive for COVID-19 were admitted to a medical unit with COVID-19 isolation, he said.

Once a patient is admitted, an RN activates a suicide prevention pathway, and an interprofessional team meets to determine what patients need for safe and effective discharge, said Dr. Ganem. He cited the SAFE-T protocol (Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage) as one of the tools used to determine safe discharge criteria. Considerations on the SAFE-T list include family support, an established outpatient therapist and psychiatrist, no suicide attempts prior to the current admission, or a low lethality attempt, and access to partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient programs.

Patients who could not be discharged because of suicidality or inadequate support or concerns about safety at home were considered for inpatient admission. Patients with COVID-19–positive tests who had continued need for inpatient mental health services could be transferred to an inpatient mental health unit after a 10-day quarantine.

Overall, “this has been a continuum of lessons learned, with some things we know now that we didn’t know in April or May of 2020,” Dr. Ganem said. Early in the pandemic, the focus was on minimizing risk, securing personal protective equipment, and determining who provided services in a patient’s room. “We developed new paradigms on the fly,” he said, including the use of virtual visits, which included securing and cleaning devices, as well as learning how to use them in this setting,” he said.

More recently, the emphasis has been on providing services to patients before they need to visit the hospital, rather than automatically admitting any patients with suicidal ideation and a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Ganem said.

Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem had no financial conflicts to disclose. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact child and adolescent mental health, and clinicians are learning as they go to develop strategies that address the challenges of providing both medical and mental health care to young patients, including those who test positive for COVID-19, according to Hani Talebi, PhD, director of pediatric psychology, and Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, director of pediatric hospital medicine, both of the University of Texas at Austin and Dell Children’s Medical Center.

In a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem shared their experiences in identifying the impact of the pandemic on mental health services in a freestanding hospital, and synthesizing inpatient mental health care and medical care outside of a dedicated mental health unit.

Mental health is a significant pediatric issue; approximately one in five children have a diagnosable mental or behavioral health problem, but nearly two-thirds get little or no help, Dr. Talebi said. “COVID-19 has only exacerbated these mental health challenges,” he said.

He noted that beginning in April 2020, the proportion of children’s mental health-related emergency department visits increased and remained elevated through the spring, summer, and fall of 2020, as families fearful of COVID-19 avoided regular hospital visits.

Data suggest that up to 50% of all adolescent psychiatric crises that led to inpatient admissions were related in some way to COVID-19, Dr. Talebi said. In addition, “individuals with a recent diagnosis of a mental health disorder are at increased risk for COVID-19 infection,” and the risk is even higher among women and African Americans, he said.

The past year significantly impacted the mental wellbeing of parents and children, Dr. Talebi said. He cited a June 2020 study in Pediatrics in which 27% of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health for their children. Ongoing issues including food insecurity, loss of regular child care, and an overall “very disorienting experience in the day-to-day” compromised the mental health of families, Dr. Talebi emphasized. Children isolated at home were not meeting developmental milestones that organically occur when socializing with peers, parents didn’t know how to handle some of their children’s issues without support from schools, and many people were struggling with other preexisting health conditions, he said.

This confluence of factors helped drive a surge in emergency department visits, meaning longer wait times and concerns about meeting urgent medical and mental health needs while maintaining safety, he added.

Parents and children waited longer to seek care, and community hospitals such as Dell Children’s Medical Center were faced with children in the emergency department with crisis-level mental health issues, along with children already waiting in the ED to address medical emergencies. All these patients had to be tested for COVID-19 and managed accordingly, Dr. Talebi noted.

Dr. Talebi emphasized the need for clinically robust care of the children who were in isolation for 10 days on the medical unit, waiting to test negative. New protocols were created for social workers to conduct daily safety checks, and to develop regular schedules for screening, “so they are having an experience on the medical floors similar to what they would have in a mental health unit,” he said.

Dr. Ganem reflected on the logistical challenges of managing mental health care while observing COVID-19 safety protocols. “COVID-19 added a new wrinkle of isolation,” he said. As institutional guidelines on testing and isolation evolved, negative COVID-19 tests were required for admission to the mental health units both in the hospital and throughout the region. Patients who tested positive had to be quarantined for 10 days, at which time they could be admitted to a mental health unit if necessary, he said.

Dr. Ganem shared details of some strategies adopted by Dell Children’s. He explained that the COVID-19 psychiatry patient workflow started with an ED evaluation, followed by medical clearance and consideration for admission.

“There was significant coordination between the social worker in the emergency department and the psychiatry social worker,” he said.

Key elements of the treatment plan for children with positive COVID-19 tests included an “interprofessional huddle” to coordinate the plan of care, goals for admission, and goals for safety, Dr. Ganem said.

Patients who required admission were expected to have an initial length of stay of 72 hours, and those who tested positive for COVID-19 were admitted to a medical unit with COVID-19 isolation, he said.

Once a patient is admitted, an RN activates a suicide prevention pathway, and an interprofessional team meets to determine what patients need for safe and effective discharge, said Dr. Ganem. He cited the SAFE-T protocol (Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage) as one of the tools used to determine safe discharge criteria. Considerations on the SAFE-T list include family support, an established outpatient therapist and psychiatrist, no suicide attempts prior to the current admission, or a low lethality attempt, and access to partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient programs.

Patients who could not be discharged because of suicidality or inadequate support or concerns about safety at home were considered for inpatient admission. Patients with COVID-19–positive tests who had continued need for inpatient mental health services could be transferred to an inpatient mental health unit after a 10-day quarantine.

Overall, “this has been a continuum of lessons learned, with some things we know now that we didn’t know in April or May of 2020,” Dr. Ganem said. Early in the pandemic, the focus was on minimizing risk, securing personal protective equipment, and determining who provided services in a patient’s room. “We developed new paradigms on the fly,” he said, including the use of virtual visits, which included securing and cleaning devices, as well as learning how to use them in this setting,” he said.

More recently, the emphasis has been on providing services to patients before they need to visit the hospital, rather than automatically admitting any patients with suicidal ideation and a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Ganem said.

Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem had no financial conflicts to disclose. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact child and adolescent mental health, and clinicians are learning as they go to develop strategies that address the challenges of providing both medical and mental health care to young patients, including those who test positive for COVID-19, according to Hani Talebi, PhD, director of pediatric psychology, and Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, director of pediatric hospital medicine, both of the University of Texas at Austin and Dell Children’s Medical Center.

In a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem shared their experiences in identifying the impact of the pandemic on mental health services in a freestanding hospital, and synthesizing inpatient mental health care and medical care outside of a dedicated mental health unit.

Mental health is a significant pediatric issue; approximately one in five children have a diagnosable mental or behavioral health problem, but nearly two-thirds get little or no help, Dr. Talebi said. “COVID-19 has only exacerbated these mental health challenges,” he said.

He noted that beginning in April 2020, the proportion of children’s mental health-related emergency department visits increased and remained elevated through the spring, summer, and fall of 2020, as families fearful of COVID-19 avoided regular hospital visits.

Data suggest that up to 50% of all adolescent psychiatric crises that led to inpatient admissions were related in some way to COVID-19, Dr. Talebi said. In addition, “individuals with a recent diagnosis of a mental health disorder are at increased risk for COVID-19 infection,” and the risk is even higher among women and African Americans, he said.

The past year significantly impacted the mental wellbeing of parents and children, Dr. Talebi said. He cited a June 2020 study in Pediatrics in which 27% of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health for their children. Ongoing issues including food insecurity, loss of regular child care, and an overall “very disorienting experience in the day-to-day” compromised the mental health of families, Dr. Talebi emphasized. Children isolated at home were not meeting developmental milestones that organically occur when socializing with peers, parents didn’t know how to handle some of their children’s issues without support from schools, and many people were struggling with other preexisting health conditions, he said.

This confluence of factors helped drive a surge in emergency department visits, meaning longer wait times and concerns about meeting urgent medical and mental health needs while maintaining safety, he added.

Parents and children waited longer to seek care, and community hospitals such as Dell Children’s Medical Center were faced with children in the emergency department with crisis-level mental health issues, along with children already waiting in the ED to address medical emergencies. All these patients had to be tested for COVID-19 and managed accordingly, Dr. Talebi noted.

Dr. Talebi emphasized the need for clinically robust care of the children who were in isolation for 10 days on the medical unit, waiting to test negative. New protocols were created for social workers to conduct daily safety checks, and to develop regular schedules for screening, “so they are having an experience on the medical floors similar to what they would have in a mental health unit,” he said.

Dr. Ganem reflected on the logistical challenges of managing mental health care while observing COVID-19 safety protocols. “COVID-19 added a new wrinkle of isolation,” he said. As institutional guidelines on testing and isolation evolved, negative COVID-19 tests were required for admission to the mental health units both in the hospital and throughout the region. Patients who tested positive had to be quarantined for 10 days, at which time they could be admitted to a mental health unit if necessary, he said.

Dr. Ganem shared details of some strategies adopted by Dell Children’s. He explained that the COVID-19 psychiatry patient workflow started with an ED evaluation, followed by medical clearance and consideration for admission.

“There was significant coordination between the social worker in the emergency department and the psychiatry social worker,” he said.

Key elements of the treatment plan for children with positive COVID-19 tests included an “interprofessional huddle” to coordinate the plan of care, goals for admission, and goals for safety, Dr. Ganem said.

Patients who required admission were expected to have an initial length of stay of 72 hours, and those who tested positive for COVID-19 were admitted to a medical unit with COVID-19 isolation, he said.

Once a patient is admitted, an RN activates a suicide prevention pathway, and an interprofessional team meets to determine what patients need for safe and effective discharge, said Dr. Ganem. He cited the SAFE-T protocol (Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage) as one of the tools used to determine safe discharge criteria. Considerations on the SAFE-T list include family support, an established outpatient therapist and psychiatrist, no suicide attempts prior to the current admission, or a low lethality attempt, and access to partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient programs.

Patients who could not be discharged because of suicidality or inadequate support or concerns about safety at home were considered for inpatient admission. Patients with COVID-19–positive tests who had continued need for inpatient mental health services could be transferred to an inpatient mental health unit after a 10-day quarantine.

Overall, “this has been a continuum of lessons learned, with some things we know now that we didn’t know in April or May of 2020,” Dr. Ganem said. Early in the pandemic, the focus was on minimizing risk, securing personal protective equipment, and determining who provided services in a patient’s room. “We developed new paradigms on the fly,” he said, including the use of virtual visits, which included securing and cleaning devices, as well as learning how to use them in this setting,” he said.

More recently, the emphasis has been on providing services to patients before they need to visit the hospital, rather than automatically admitting any patients with suicidal ideation and a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Ganem said.

Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem had no financial conflicts to disclose. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

FROM PHM 2021

Anakinra improved survival in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients at increased risk for respiratory failure showed significant improvement after treatment with anakinra, compared with placebo, based on data from a phase 3, randomized trial of nearly 600 patients who also received standard of care treatment.

Anakinra, a recombinant interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist that blocks activity for both IL-1 alpha and beta, showed a 70% decrease in the risk of progression to severe respiratory failure in a prior open-label, phase 2, proof-of-concept study, wrote Evdoxia Kyriazopoulou, MD, PhD, of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and colleagues.

Previous research has shown that soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) serum levels can signal increased risk of progression to severe disease and respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients, they noted.

Supported by these early findings, “the SAVE-MORE study (suPAR-guided anakinra treatment for validation of the risk and early management of severe respiratory failure by COVID-19) is a pivotal, confirmatory, phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of early initiation of anakinra treatment in hospitalized patients with moderate or severe COVID-19,” the researchers said.

In the SAVE-MORE study published Sept. 3 in Nature Medicine, the researchers identified 594 adults with COVID-19 who were hospitalized at 37 centers in Greece and Italy and at risk of progressing to respiratory failure based on plasma suPAR levels of at least 6 ng/mL.

The primary objective was to assess the impact of early anakinra treatment on the clinical status of COVID-19 patients at risk for severe disease according to the 11-point, ordinal World Health Organization Clinical Progression Scale (WHO-CPS) at 28 days after starting treatment. All patients received standard of care, which consisted of regular monitoring of physical signs, oximetry, and anticoagulation. Patients with severe disease by the WHO definition were also received 6 mg of dexamethasone intravenously daily for 10 days. A total of 405 were randomized to anakinra and 189 to placebo. Approximately 92% of the study participants had severe pneumonia according to the WHO classification for COVID-19. The average age of the patients was 62 years, 58% were male, and the average body mass index was 29.5 kg/m2.

At 28 days, 204 (50.4%) of the anakinra-treated patients had fully recovered, with no detectable viral RNA, compared with 50 (26.5%) of the placebo-treated patients (P < .0001). In addition, significantly fewer patients in the anakinra group had died by 28 days (13 patients, 3.2%), compared with patients in the placebo group (13 patients, 6.9%).

The median decrease in WHO-CPS scores from baseline to 28 days was 4 points in the anakinra group and 3 points in the placebo group, a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

“Overall, the unadjusted proportional odds of having a worse score on the 11-point WHO-CPS at day 28 with anakinra was 0.36 versus placebo,” and this number remained the same in adjusted analysis, the researchers wrote.

All five secondary endpoints on the WHO-CPS showed significant benefits of anakinra, compared with placebo. These included an absolute decrease of WHO-CPS at day 28 and day 14 from baseline; an absolute decrease of Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores at day 7 from baseline; and a significantly shorter mean time to both hospital and ICU discharge (1 day and 4 days, respectively) with anakinra versus placebo.

Follow-up laboratory data showed a significant increase in absolute lymphocyte count at 7 days, a significant decrease in circulating IL-6 levels at 4 and 7 days, and significantly decreased plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 7 days.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 16% with anakinra and in 21.7% with placebo; the most common of these events were infections (8.4% with anakinra and 15.9% with placebo). The next most common serious treatment-emergent adverse events were ventilator-associated pneumonia, septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction, bloodstream infections, and pulmonary embolism. The most common nonserious treatment-emergent adverse events were an increase of liver function tests and hyperglycemia (similar in anakinra and placebo groups) and nonserious anemia (lower in the anakinra group).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of patients with critical COVID-19 disease and the challenge of application of suPAR in all hospital settings, the researchers noted. However, “the results validate the findings of the previous SAVE open-label phase 2 trial,” they said. The results suggest “that suPAR should be measured upon admission of all patients with COVID-19 who do not need oxygen or who need nasal or mask oxygen, and that, if suPAR levels are 6 ng/mL or higher, anakinra treatment might be a suitable therapy,” they concluded.

Cytokine storm syndrome remains a treatment challenge

“Many who die from COVID-19 suffer hyperinflammation with features of cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) and associated acute respiratory distress syndrome,” wrote Randy Q. Cron, MD, and W. Winn Chatham, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Roberto Caricchio, MD, of Temple University, Philadelphia, in an accompanying editorial. They noted that the SAVE-MORE trial results contrast with another recent randomized trial of canakinumab, which failed to show notable benefits, compared with placebo, in treating hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

“There are some key differences between these trials, one being that anakinra blocks signaling of both IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta, whereas canakinumab binds only IL-1 beta,” the editorialists explained. “SARS-CoV-2–infected endothelium may be a particularly important source of IL-1 alpha that is not targeted by canakinumab,” they noted.

Additional studies have examined IL-6 inhibition to treat COVID-19 patients, but data have been inconsistent, the editorialists said.

“One thing that is clearly emerging from this pandemic is that the CSS associated with COVID-19 is relatively unique, with only modestly elevated levels of IL-6, CRP, and ferritin, for example,” they noted. However, the SAVE-MORE study suggests that more targeted approaches, such as anakinra, “may allow earlier introduction of anticytokine treatment” and support the use of IL-1 blockade with anakinra for cases of severe COVID-19 pneumonia.

Predicting risk for severe disease

“One of the major challenges in the management of patients with COVID-19 is identifying patients at risk of severe disease who would warrant early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy,” said Salim Hayek, MD, medical director of the University of Michigan’s Frankel Cardiovascular Center Clinics, in an interview. “We and others had found that soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) levels are the strongest predictor of severe disease amongst biomarkers of inflammation,” he said. “In this study, patients with high suPAR levels derived benefit from anakinra, compared to those with placebo. This study is a great example of how suPAR levels could be used to identify high-risk patients that would benefit from therapies targeting inflammation,” Dr. Hayek emphasized.

“The findings are in line with the hypothesis that patients with the highest degrees of inflammation would benefit the best from targeting the hyperinflammatory cascade using anakinra or other interleukin antagonists,” Dr. Hayek said. “Given suPAR levels are the best predictors of high-risk disease, it is not surprising to see that patients with high levels benefit from targeting inflammation,” he noted.

The take-home message for clinicians at this time is that anakinra effectively improves outcomes in COVID-19 patients with high suPAR levels, Dr. Hayek said. “SuPAR can be measured easily at the point of care. Thus, a targeted strategy using suPAR to identify patients who would benefit from anakinra appears to be viable,” he explained.

However, “Whether anakinra is effective in patients with lower suPAR levels (<6 ng/mL) is unclear and was not answered by this study,” he said. “We eagerly await results of other trials to make that determination. Whether suPAR levels can also help guide the use of other therapies for COVID-19 should be explored and would enhance the personalization of treatment for COVID-19 according to the underlying inflammatory state,” he added.

The SAVE-MORE study was funded by the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis and Sobi, which manufactures anakinra. Some of the study authors reported financial relationships with Sobi and other pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Cron disclosed serving as a consultant to Sobi, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sironax. Dr. Cron and Dr. Chatham disclosed having received grant support from Sobi for investigator-initiated clinical trials, and Dr. Caricchio disclosed serving as a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Aurinia, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Hayek had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients at increased risk for respiratory failure showed significant improvement after treatment with anakinra, compared with placebo, based on data from a phase 3, randomized trial of nearly 600 patients who also received standard of care treatment.

Anakinra, a recombinant interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist that blocks activity for both IL-1 alpha and beta, showed a 70% decrease in the risk of progression to severe respiratory failure in a prior open-label, phase 2, proof-of-concept study, wrote Evdoxia Kyriazopoulou, MD, PhD, of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and colleagues.

Previous research has shown that soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) serum levels can signal increased risk of progression to severe disease and respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients, they noted.

Supported by these early findings, “the SAVE-MORE study (suPAR-guided anakinra treatment for validation of the risk and early management of severe respiratory failure by COVID-19) is a pivotal, confirmatory, phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of early initiation of anakinra treatment in hospitalized patients with moderate or severe COVID-19,” the researchers said.

In the SAVE-MORE study published Sept. 3 in Nature Medicine, the researchers identified 594 adults with COVID-19 who were hospitalized at 37 centers in Greece and Italy and at risk of progressing to respiratory failure based on plasma suPAR levels of at least 6 ng/mL.

The primary objective was to assess the impact of early anakinra treatment on the clinical status of COVID-19 patients at risk for severe disease according to the 11-point, ordinal World Health Organization Clinical Progression Scale (WHO-CPS) at 28 days after starting treatment. All patients received standard of care, which consisted of regular monitoring of physical signs, oximetry, and anticoagulation. Patients with severe disease by the WHO definition were also received 6 mg of dexamethasone intravenously daily for 10 days. A total of 405 were randomized to anakinra and 189 to placebo. Approximately 92% of the study participants had severe pneumonia according to the WHO classification for COVID-19. The average age of the patients was 62 years, 58% were male, and the average body mass index was 29.5 kg/m2.

At 28 days, 204 (50.4%) of the anakinra-treated patients had fully recovered, with no detectable viral RNA, compared with 50 (26.5%) of the placebo-treated patients (P < .0001). In addition, significantly fewer patients in the anakinra group had died by 28 days (13 patients, 3.2%), compared with patients in the placebo group (13 patients, 6.9%).

The median decrease in WHO-CPS scores from baseline to 28 days was 4 points in the anakinra group and 3 points in the placebo group, a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

“Overall, the unadjusted proportional odds of having a worse score on the 11-point WHO-CPS at day 28 with anakinra was 0.36 versus placebo,” and this number remained the same in adjusted analysis, the researchers wrote.

All five secondary endpoints on the WHO-CPS showed significant benefits of anakinra, compared with placebo. These included an absolute decrease of WHO-CPS at day 28 and day 14 from baseline; an absolute decrease of Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores at day 7 from baseline; and a significantly shorter mean time to both hospital and ICU discharge (1 day and 4 days, respectively) with anakinra versus placebo.

Follow-up laboratory data showed a significant increase in absolute lymphocyte count at 7 days, a significant decrease in circulating IL-6 levels at 4 and 7 days, and significantly decreased plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 7 days.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 16% with anakinra and in 21.7% with placebo; the most common of these events were infections (8.4% with anakinra and 15.9% with placebo). The next most common serious treatment-emergent adverse events were ventilator-associated pneumonia, septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction, bloodstream infections, and pulmonary embolism. The most common nonserious treatment-emergent adverse events were an increase of liver function tests and hyperglycemia (similar in anakinra and placebo groups) and nonserious anemia (lower in the anakinra group).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of patients with critical COVID-19 disease and the challenge of application of suPAR in all hospital settings, the researchers noted. However, “the results validate the findings of the previous SAVE open-label phase 2 trial,” they said. The results suggest “that suPAR should be measured upon admission of all patients with COVID-19 who do not need oxygen or who need nasal or mask oxygen, and that, if suPAR levels are 6 ng/mL or higher, anakinra treatment might be a suitable therapy,” they concluded.

Cytokine storm syndrome remains a treatment challenge

“Many who die from COVID-19 suffer hyperinflammation with features of cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) and associated acute respiratory distress syndrome,” wrote Randy Q. Cron, MD, and W. Winn Chatham, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Roberto Caricchio, MD, of Temple University, Philadelphia, in an accompanying editorial. They noted that the SAVE-MORE trial results contrast with another recent randomized trial of canakinumab, which failed to show notable benefits, compared with placebo, in treating hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

“There are some key differences between these trials, one being that anakinra blocks signaling of both IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta, whereas canakinumab binds only IL-1 beta,” the editorialists explained. “SARS-CoV-2–infected endothelium may be a particularly important source of IL-1 alpha that is not targeted by canakinumab,” they noted.

Additional studies have examined IL-6 inhibition to treat COVID-19 patients, but data have been inconsistent, the editorialists said.

“One thing that is clearly emerging from this pandemic is that the CSS associated with COVID-19 is relatively unique, with only modestly elevated levels of IL-6, CRP, and ferritin, for example,” they noted. However, the SAVE-MORE study suggests that more targeted approaches, such as anakinra, “may allow earlier introduction of anticytokine treatment” and support the use of IL-1 blockade with anakinra for cases of severe COVID-19 pneumonia.

Predicting risk for severe disease

“One of the major challenges in the management of patients with COVID-19 is identifying patients at risk of severe disease who would warrant early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy,” said Salim Hayek, MD, medical director of the University of Michigan’s Frankel Cardiovascular Center Clinics, in an interview. “We and others had found that soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) levels are the strongest predictor of severe disease amongst biomarkers of inflammation,” he said. “In this study, patients with high suPAR levels derived benefit from anakinra, compared to those with placebo. This study is a great example of how suPAR levels could be used to identify high-risk patients that would benefit from therapies targeting inflammation,” Dr. Hayek emphasized.

“The findings are in line with the hypothesis that patients with the highest degrees of inflammation would benefit the best from targeting the hyperinflammatory cascade using anakinra or other interleukin antagonists,” Dr. Hayek said. “Given suPAR levels are the best predictors of high-risk disease, it is not surprising to see that patients with high levels benefit from targeting inflammation,” he noted.

The take-home message for clinicians at this time is that anakinra effectively improves outcomes in COVID-19 patients with high suPAR levels, Dr. Hayek said. “SuPAR can be measured easily at the point of care. Thus, a targeted strategy using suPAR to identify patients who would benefit from anakinra appears to be viable,” he explained.

However, “Whether anakinra is effective in patients with lower suPAR levels (<6 ng/mL) is unclear and was not answered by this study,” he said. “We eagerly await results of other trials to make that determination. Whether suPAR levels can also help guide the use of other therapies for COVID-19 should be explored and would enhance the personalization of treatment for COVID-19 according to the underlying inflammatory state,” he added.

The SAVE-MORE study was funded by the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis and Sobi, which manufactures anakinra. Some of the study authors reported financial relationships with Sobi and other pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Cron disclosed serving as a consultant to Sobi, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sironax. Dr. Cron and Dr. Chatham disclosed having received grant support from Sobi for investigator-initiated clinical trials, and Dr. Caricchio disclosed serving as a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Aurinia, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Hayek had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Hospitalized COVID-19 patients at increased risk for respiratory failure showed significant improvement after treatment with anakinra, compared with placebo, based on data from a phase 3, randomized trial of nearly 600 patients who also received standard of care treatment.

Anakinra, a recombinant interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist that blocks activity for both IL-1 alpha and beta, showed a 70% decrease in the risk of progression to severe respiratory failure in a prior open-label, phase 2, proof-of-concept study, wrote Evdoxia Kyriazopoulou, MD, PhD, of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and colleagues.

Previous research has shown that soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) serum levels can signal increased risk of progression to severe disease and respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients, they noted.

Supported by these early findings, “the SAVE-MORE study (suPAR-guided anakinra treatment for validation of the risk and early management of severe respiratory failure by COVID-19) is a pivotal, confirmatory, phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of early initiation of anakinra treatment in hospitalized patients with moderate or severe COVID-19,” the researchers said.

In the SAVE-MORE study published Sept. 3 in Nature Medicine, the researchers identified 594 adults with COVID-19 who were hospitalized at 37 centers in Greece and Italy and at risk of progressing to respiratory failure based on plasma suPAR levels of at least 6 ng/mL.

The primary objective was to assess the impact of early anakinra treatment on the clinical status of COVID-19 patients at risk for severe disease according to the 11-point, ordinal World Health Organization Clinical Progression Scale (WHO-CPS) at 28 days after starting treatment. All patients received standard of care, which consisted of regular monitoring of physical signs, oximetry, and anticoagulation. Patients with severe disease by the WHO definition were also received 6 mg of dexamethasone intravenously daily for 10 days. A total of 405 were randomized to anakinra and 189 to placebo. Approximately 92% of the study participants had severe pneumonia according to the WHO classification for COVID-19. The average age of the patients was 62 years, 58% were male, and the average body mass index was 29.5 kg/m2.

At 28 days, 204 (50.4%) of the anakinra-treated patients had fully recovered, with no detectable viral RNA, compared with 50 (26.5%) of the placebo-treated patients (P < .0001). In addition, significantly fewer patients in the anakinra group had died by 28 days (13 patients, 3.2%), compared with patients in the placebo group (13 patients, 6.9%).

The median decrease in WHO-CPS scores from baseline to 28 days was 4 points in the anakinra group and 3 points in the placebo group, a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

“Overall, the unadjusted proportional odds of having a worse score on the 11-point WHO-CPS at day 28 with anakinra was 0.36 versus placebo,” and this number remained the same in adjusted analysis, the researchers wrote.

All five secondary endpoints on the WHO-CPS showed significant benefits of anakinra, compared with placebo. These included an absolute decrease of WHO-CPS at day 28 and day 14 from baseline; an absolute decrease of Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores at day 7 from baseline; and a significantly shorter mean time to both hospital and ICU discharge (1 day and 4 days, respectively) with anakinra versus placebo.

Follow-up laboratory data showed a significant increase in absolute lymphocyte count at 7 days, a significant decrease in circulating IL-6 levels at 4 and 7 days, and significantly decreased plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 7 days.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 16% with anakinra and in 21.7% with placebo; the most common of these events were infections (8.4% with anakinra and 15.9% with placebo). The next most common serious treatment-emergent adverse events were ventilator-associated pneumonia, septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction, bloodstream infections, and pulmonary embolism. The most common nonserious treatment-emergent adverse events were an increase of liver function tests and hyperglycemia (similar in anakinra and placebo groups) and nonserious anemia (lower in the anakinra group).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of patients with critical COVID-19 disease and the challenge of application of suPAR in all hospital settings, the researchers noted. However, “the results validate the findings of the previous SAVE open-label phase 2 trial,” they said. The results suggest “that suPAR should be measured upon admission of all patients with COVID-19 who do not need oxygen or who need nasal or mask oxygen, and that, if suPAR levels are 6 ng/mL or higher, anakinra treatment might be a suitable therapy,” they concluded.

Cytokine storm syndrome remains a treatment challenge

“Many who die from COVID-19 suffer hyperinflammation with features of cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) and associated acute respiratory distress syndrome,” wrote Randy Q. Cron, MD, and W. Winn Chatham, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Roberto Caricchio, MD, of Temple University, Philadelphia, in an accompanying editorial. They noted that the SAVE-MORE trial results contrast with another recent randomized trial of canakinumab, which failed to show notable benefits, compared with placebo, in treating hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

“There are some key differences between these trials, one being that anakinra blocks signaling of both IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta, whereas canakinumab binds only IL-1 beta,” the editorialists explained. “SARS-CoV-2–infected endothelium may be a particularly important source of IL-1 alpha that is not targeted by canakinumab,” they noted.

Additional studies have examined IL-6 inhibition to treat COVID-19 patients, but data have been inconsistent, the editorialists said.

“One thing that is clearly emerging from this pandemic is that the CSS associated with COVID-19 is relatively unique, with only modestly elevated levels of IL-6, CRP, and ferritin, for example,” they noted. However, the SAVE-MORE study suggests that more targeted approaches, such as anakinra, “may allow earlier introduction of anticytokine treatment” and support the use of IL-1 blockade with anakinra for cases of severe COVID-19 pneumonia.

Predicting risk for severe disease

“One of the major challenges in the management of patients with COVID-19 is identifying patients at risk of severe disease who would warrant early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy,” said Salim Hayek, MD, medical director of the University of Michigan’s Frankel Cardiovascular Center Clinics, in an interview. “We and others had found that soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) levels are the strongest predictor of severe disease amongst biomarkers of inflammation,” he said. “In this study, patients with high suPAR levels derived benefit from anakinra, compared to those with placebo. This study is a great example of how suPAR levels could be used to identify high-risk patients that would benefit from therapies targeting inflammation,” Dr. Hayek emphasized.

“The findings are in line with the hypothesis that patients with the highest degrees of inflammation would benefit the best from targeting the hyperinflammatory cascade using anakinra or other interleukin antagonists,” Dr. Hayek said. “Given suPAR levels are the best predictors of high-risk disease, it is not surprising to see that patients with high levels benefit from targeting inflammation,” he noted.

The take-home message for clinicians at this time is that anakinra effectively improves outcomes in COVID-19 patients with high suPAR levels, Dr. Hayek said. “SuPAR can be measured easily at the point of care. Thus, a targeted strategy using suPAR to identify patients who would benefit from anakinra appears to be viable,” he explained.

However, “Whether anakinra is effective in patients with lower suPAR levels (<6 ng/mL) is unclear and was not answered by this study,” he said. “We eagerly await results of other trials to make that determination. Whether suPAR levels can also help guide the use of other therapies for COVID-19 should be explored and would enhance the personalization of treatment for COVID-19 according to the underlying inflammatory state,” he added.

The SAVE-MORE study was funded by the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis and Sobi, which manufactures anakinra. Some of the study authors reported financial relationships with Sobi and other pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Cron disclosed serving as a consultant to Sobi, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sironax. Dr. Cron and Dr. Chatham disclosed having received grant support from Sobi for investigator-initiated clinical trials, and Dr. Caricchio disclosed serving as a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Aurinia, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Hayek had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Addressing vaccine hesitancy with patients

Breakthrough with empathy and compassion

The COVID-19 pandemic is a worldwide tragedy. In the beginning there was a lack of testing, personal protective equipment, COVID tests, and support for health care workers and patients. As 2020 came to a close, the world was given a glimpse of hope with the development of a vaccine against the deadly virus. Many world citizens celebrated the scientific accomplishment and began to breathe a sigh of relief that there was an end in sight. However, the development and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine revealed a new challenge, vaccine hesitancy.

Community members, young healthy people, and even critically ill hospitalized patients who have the fortune of surviving acute illness are hesitant to the COVID-19 vaccine. I recently cared for a critically ill young patient who was intubated for days with status asthmaticus, one of the worst cases I’d ever seen. She was extubated and made a full recovery. Prior to discharge I asked if she wanted the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and she said, “No.” I was shocked. This was an otherwise healthy 30-something-year-old who was lucky enough to survive without any underlying infection in the setting of severe obstructive lung disease. A co-infection with COVID-19 would be disastrous and increase her mortality. I had a long talk at the bedside and asked the reason for her hesitancy. Her answer left me speechless, “I don’t know, I just don’t want to.” I ultimately convinced her that contracting COVID-19 would be a fate worse than she could imagine, and she agreed to the vaccine prior to discharge. This interaction made me ponder – “why are our patients, friends, and family members hesitant about receiving a lifesaving vaccine, especially when they are aware of how sick they or others can become without it?”

According to the World Health Organization, vaccine hesitancy refers to a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place, and vaccines. It is influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience, and confidence.1 No vaccine is 100% effective. However, throughout history, the work of scientists and doctors to create vaccines saved millions of lives and revolutionized global health. Arguably, the single most life-saving innovation in the history of medicine, vaccines have eradicated smallpox, protected against whooping cough (1914), diphtheria (1926), tetanus (1938), influenza (1945) and mumps (1948), polio (1955), measles (1963), and rubella (1969), and worldwide vaccination rates increased dramatically thanks to successful global health campaigns.2 However, there was a paradox of vaccine success. As terrifying diseases decreased in prevalence, so did the fear of these diseases and their effects – paralysis, brain damage, blindness, and death. This gave birth to a new challenge in modern medicine, vaccine hesitancy – a privilege of first world nations.

Vaccines saved countless lives and improved health and wellbeing around the world for decades. However, to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with vaccine-preventable diseases and their complications, and optimize control of vaccine-preventable diseases in communities, high vaccination rates must be achieved. Enter the COVID-19 pandemic, the creation of the COVID-19 vaccine, and vaccine hesitancy.

The question we ask ourselves as health care providers is ‘how do we convince the skeptics and those opposed to vaccination to take the vaccine?’ The answer is complicated. If you are like me, you’ve had many conversations with people – friends, patients, family members, who are resistant to the vaccine. Very often the facts are not well received, and those discussions end in argument, high emotions, and broken relationships. With the delta variant of COVID-19 on the rise, spreading aggressively among the unvaccinated, and increased hospitalizations, we foresee the reoccurrence of overwhelmed health systems and a continued death toll.

The new paradox we are faced with is that people choose to believe fiction versus fact, despite the real life evidence of the severe health effects and increased deaths related to COVID-19. Do these skeptics simply have a cavalier attitude towards not only their own life, but the lives of others? Or, is there something deeper? It is not enough to tell people that the vaccines are proven safe3 and are more widely available than ever. It is not enough to tell people that they can die of COVID-19 – they already know that. Emotional pleas to family members are falling on deaf ears. This past month, when asking patients why they don’t want the vaccine, many have no real legitimate health-related reason and respond with a simple, “I don’t want to.” So, how do we get through to the unvaccinated?

A compassionate approach

We navigate these difficult conversations over time with the approach of compassion and empathy, not hostility or bullying. As health care providers, we start by being good empathic listeners. Similar to when we have advance care planning and code status conversations, we cannot enter the dialogue with our intention, beliefs, or formulated goals for that person. We have to listen without judgement to the wide range of reasons why others are reluctant or unwilling to get the vaccine – historical mistrust, political identity, religious reasons, short-term side effects that may cause them to lose a day or two of work – and understand that for each person their reasons are different. The point is to not assume that you know or understand what barriers and beliefs they have towards vaccination, but to meet them at their point of view and listen while keeping your own emotions level and steady.

Identifying the reason for vaccine hesitancy is the first step to getting the unvaccinated closer to vaccination. Ask open ended questions: “Can you help me understand, what is your hesitancy to the vaccine?”; “What about the vaccine worries you?”; “What have you heard about/know about the COVID-19 vaccine?”; or “Can you tell me more about why you feel that way?” As meticulous as it sounds, we have to go back to the basics of patient interviewing.

It is important to remember that this is not a debate and escalation to arguments will certainly backfire. Think about any time you disagreed with someone on a topic. Did criticizing, blaming, and shaming ever convince you to change your beliefs or behaviors? The likely answer is, “No.” Avoid the “backfire effect”– which is when giving people facts disproving their “incorrect” beliefs can actually reinforce those beliefs. The more people are confronted with facts at odds with their opinions, the stronger they cling to those opinions. If you want them to change their mind, you cannot approach the conversation as a debate. You are having this vaccine discussion to try to meet the other person where they are, understand their position, and talk with them, and not at them, about their concerns.

As leaders in health care, we have to be willing to give up control and lead with empathy. We have to show others that we hear them, believe their concerns, and acknowledge that their beliefs are valid to them as individuals. Even if you disagree, this is not the place to let anger, disappointment, or resentment take a front seat. This is about balance, and highlighting the autonomy in decision making that the other person has to make a choice. Be humble in these conversations and avoid condescending tones or statements.

We already know that you are a caring health care provider. As hospitalists, we are frontline providers who have seen unnecessary deaths and illness due to COVID-19. You are passionate and motivated because you are committed to your oath to save lives. However, you have to check your own feelings and remember that you are not speaking with an unvaccinated person to make them get vaccinated, but rather to understand their cognitive process and hopefully walk with them down a path that provides them with a clarity of options they truly have. Extend empathy and they will see your motivation is rooted in good-heartedness and a concern for their wellbeing.

If someone admits to reasons for avoiding vaccination that are not rooted in any fact, then guide them to the best resources. Our health care system recently released a COVID-19 fact versus myth handout called Trust the Facts. This could be the kind of vetted resource you offer. Guide them to accredited websites, such as the World Health Organization, the Center for Disease Control, or their local and state departments of health to help debunk fiction by reviewing it with them. Discuss myths such as, ‘the vaccine will cause infertility,’ ‘the vaccine will give me COVID,’ ‘the vaccine was rushed and is not safe,’ ‘the vaccine is not needed if I am young and healthy,’ ‘the vaccine has a microchip,’ etc. Knowledge is power and disinformation is deadly, but how facts are presented will make the biggest difference in how others receive them, so remember your role is not to argue with these statements, but rather to provide perspective without agreeing or disagreeing.

Respond to their concerns with statements such as, “I hear you…it sounds like you are worried/fearful/mistrusting about the side effects/safety/efficacy of the vaccine…can we talk more about that?” Ask them where these concerns come from – the news, social media, an article, word of mouth, friends, or family. Ask them about the information they have and show genuine interest that you want to see it from their perspective. This is the key to compassionate and empathic dialogue – you relinquish your intentions.

Once you know or unveil their reasons for hesitancy, ask them what they would like to see with regards to COVID-19 and ending the pandemic. Would they like to get back to a new normal, to visit family members, to travel once again, to not have to wear masks and quarantine? What do they want for themselves, their families, communities, the country, or even the world? The goal is to find something in our shared humanity, to connect on a deeper level so they start to open up and let down walls, and find something you both see eye-to-eye on. Know your audience and speak to what serves them. To effectively persuade someone to come around to your point of view starts with recognizing the root of the disagreement and trying to overcome it before trying to change the person’s mind, understanding both the logic and the emotion that’s driving their decision making.4

Building trust

Reminding patients, friends or family members that their health and well-being means a lot to you can also be a strategy to keeping the conversation open and friendly. Sharing stories as hospitalists caring for many critically ill COVID patients or patients who died alone due to COVID-19, and the trauma you experienced as a health care provider feeling paralyzed by the limitations of modern medicine against the deadly virus, will only serve to humanize you in such an interaction.

Building trust will also increase vaccine willingness. This will require a concerted effort by scientists, doctors, and health care systems to engage with community leaders and members. To address hesitancy, the people we serve have to hear those local, personal, and relatable stories about vaccinations, and how it benefits not just themselves, but others around them in their community. As part of the #VaxUp campaign in Virginia, community and physician leaders shared their stories of hesitancy and motivation surrounding the vaccine. These are real people in the community discussing why getting vaccinated is so important and what helped them make an informed decision. I discussed my own hesitancy and concerns and also tackled a few vaccine myths.

As vaccinated health care workers or community leaders, you are living proof of the benefits of getting the COVID vaccine. Focus on the positives but also be honest. If your second shot gave you fevers, chills, or myalgias, then admit it and share how you overcame these expected reactions. Refocus on the safety of the vaccine and the fact that it is freely available to all people. Maybe the person you are speaking with doesn’t know where or how to get an appointment to get vaccinated. Help them find the nearest place to get an appointment and identify barriers they may have in transportation, child, or senior care to leave home safely to get vaccinated, or physical conditions that are preventing them from receiving the vaccine. Share that being vaccinated protects you from contracting the virus and spreading it to loved ones. Focus on how a fully vaccinated community and country can open up opportunities to heal and connect as a society, spend time with family/friends in another county or state, hold a newborn grandchild, or even travel outside the U.S.

There is no guarantee that you will be able to persuade someone to get vaccinated. It’s possible the outcome of your conversation will not result in the other person changing their mind in that moment. That doesn’t mean that you failed, because you started the dialogue and planted the seed. If you are a vaccinated health care provider, your words have influence and power, and we are obliged by our positions to have responsibility for the health of our communities. Don’t be discouraged, as it is through caring, compassionate, respectful, and empathic conversations that your influence will make the most difference in these relationships as you continue to advocate for all human life.

Dr. Williams is vice president of the Hampton Roads chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. She is a hospitalist at Sentara Careplex Hospital in Hampton, Va., where she also serves as vice president of the Medical Executive Committee.

References

1. World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. Oct 2014. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf

2. Hsu JL. A brief history of vaccines: Smallpox to the present. S D Med. 2013;Spec no:33-7. PMID: 23444589.

3. Chiu A, Bever L. Are they experimental? Can they alter DNA? Experts tackle lingering coronavirus vaccine fears. The Washington Post. 2021 May 14. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2021/05/14/safe-fast-vaccine-fear-infertility-dna/

4. Huang L. Edge: Turning Adversity into Advantage. New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2020.

Breakthrough with empathy and compassion

Breakthrough with empathy and compassion

The COVID-19 pandemic is a worldwide tragedy. In the beginning there was a lack of testing, personal protective equipment, COVID tests, and support for health care workers and patients. As 2020 came to a close, the world was given a glimpse of hope with the development of a vaccine against the deadly virus. Many world citizens celebrated the scientific accomplishment and began to breathe a sigh of relief that there was an end in sight. However, the development and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine revealed a new challenge, vaccine hesitancy.

Community members, young healthy people, and even critically ill hospitalized patients who have the fortune of surviving acute illness are hesitant to the COVID-19 vaccine. I recently cared for a critically ill young patient who was intubated for days with status asthmaticus, one of the worst cases I’d ever seen. She was extubated and made a full recovery. Prior to discharge I asked if she wanted the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and she said, “No.” I was shocked. This was an otherwise healthy 30-something-year-old who was lucky enough to survive without any underlying infection in the setting of severe obstructive lung disease. A co-infection with COVID-19 would be disastrous and increase her mortality. I had a long talk at the bedside and asked the reason for her hesitancy. Her answer left me speechless, “I don’t know, I just don’t want to.” I ultimately convinced her that contracting COVID-19 would be a fate worse than she could imagine, and she agreed to the vaccine prior to discharge. This interaction made me ponder – “why are our patients, friends, and family members hesitant about receiving a lifesaving vaccine, especially when they are aware of how sick they or others can become without it?”

According to the World Health Organization, vaccine hesitancy refers to a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place, and vaccines. It is influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience, and confidence.1 No vaccine is 100% effective. However, throughout history, the work of scientists and doctors to create vaccines saved millions of lives and revolutionized global health. Arguably, the single most life-saving innovation in the history of medicine, vaccines have eradicated smallpox, protected against whooping cough (1914), diphtheria (1926), tetanus (1938), influenza (1945) and mumps (1948), polio (1955), measles (1963), and rubella (1969), and worldwide vaccination rates increased dramatically thanks to successful global health campaigns.2 However, there was a paradox of vaccine success. As terrifying diseases decreased in prevalence, so did the fear of these diseases and their effects – paralysis, brain damage, blindness, and death. This gave birth to a new challenge in modern medicine, vaccine hesitancy – a privilege of first world nations.

Vaccines saved countless lives and improved health and wellbeing around the world for decades. However, to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with vaccine-preventable diseases and their complications, and optimize control of vaccine-preventable diseases in communities, high vaccination rates must be achieved. Enter the COVID-19 pandemic, the creation of the COVID-19 vaccine, and vaccine hesitancy.

The question we ask ourselves as health care providers is ‘how do we convince the skeptics and those opposed to vaccination to take the vaccine?’ The answer is complicated. If you are like me, you’ve had many conversations with people – friends, patients, family members, who are resistant to the vaccine. Very often the facts are not well received, and those discussions end in argument, high emotions, and broken relationships. With the delta variant of COVID-19 on the rise, spreading aggressively among the unvaccinated, and increased hospitalizations, we foresee the reoccurrence of overwhelmed health systems and a continued death toll.

The new paradox we are faced with is that people choose to believe fiction versus fact, despite the real life evidence of the severe health effects and increased deaths related to COVID-19. Do these skeptics simply have a cavalier attitude towards not only their own life, but the lives of others? Or, is there something deeper? It is not enough to tell people that the vaccines are proven safe3 and are more widely available than ever. It is not enough to tell people that they can die of COVID-19 – they already know that. Emotional pleas to family members are falling on deaf ears. This past month, when asking patients why they don’t want the vaccine, many have no real legitimate health-related reason and respond with a simple, “I don’t want to.” So, how do we get through to the unvaccinated?

A compassionate approach

We navigate these difficult conversations over time with the approach of compassion and empathy, not hostility or bullying. As health care providers, we start by being good empathic listeners. Similar to when we have advance care planning and code status conversations, we cannot enter the dialogue with our intention, beliefs, or formulated goals for that person. We have to listen without judgement to the wide range of reasons why others are reluctant or unwilling to get the vaccine – historical mistrust, political identity, religious reasons, short-term side effects that may cause them to lose a day or two of work – and understand that for each person their reasons are different. The point is to not assume that you know or understand what barriers and beliefs they have towards vaccination, but to meet them at their point of view and listen while keeping your own emotions level and steady.

Identifying the reason for vaccine hesitancy is the first step to getting the unvaccinated closer to vaccination. Ask open ended questions: “Can you help me understand, what is your hesitancy to the vaccine?”; “What about the vaccine worries you?”; “What have you heard about/know about the COVID-19 vaccine?”; or “Can you tell me more about why you feel that way?” As meticulous as it sounds, we have to go back to the basics of patient interviewing.

It is important to remember that this is not a debate and escalation to arguments will certainly backfire. Think about any time you disagreed with someone on a topic. Did criticizing, blaming, and shaming ever convince you to change your beliefs or behaviors? The likely answer is, “No.” Avoid the “backfire effect”– which is when giving people facts disproving their “incorrect” beliefs can actually reinforce those beliefs. The more people are confronted with facts at odds with their opinions, the stronger they cling to those opinions. If you want them to change their mind, you cannot approach the conversation as a debate. You are having this vaccine discussion to try to meet the other person where they are, understand their position, and talk with them, and not at them, about their concerns.

As leaders in health care, we have to be willing to give up control and lead with empathy. We have to show others that we hear them, believe their concerns, and acknowledge that their beliefs are valid to them as individuals. Even if you disagree, this is not the place to let anger, disappointment, or resentment take a front seat. This is about balance, and highlighting the autonomy in decision making that the other person has to make a choice. Be humble in these conversations and avoid condescending tones or statements.