User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Intensive weight loss fails to help women with obesity and infertility

An intensive weight-loss intervention prior to conception had no effect on birth rates in women with obesity and unexplained infertility, compared with a standard weight-maintenance program, based on data from nearly 400 women.

Obese women experiencing infertility are often counseled to lose weight before attempting fertility treatments in order to improve outcomes based on epidemiologic evidence of an association between obesity and infertility, but data to support this advice are limited, wrote Richard S. Legro, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and colleagues.

The researchers proposed that a more intensive preconception weight loss intervention followed by infertility treatment would be more likely to yield a healthy live birth, compared with a standard weight maintenance intervention.

In an open-label study published in PLOS Medicine, the researchers randomized 379 women at nine academic centers to a standard lifestyle group that followed a weight-maintenance plan focused on physical activity, but not weight loss; or an intensive intervention of diet and medication with a target weight loss of 7%. Both interventions lasted for 16 weeks between July 2015 and July 2018. After the interventions, patients in both groups underwent standardized empiric fertility treatment with three cycles of ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination.

The primary outcome was a live birth at 37 weeks’ gestation or later, with no congenital abnormalities and a birth weight between 2,500 g and 4,000 g. Baseline characteristics including age, education level, race, and body mass index (BMI) were similar between the groups.

The incidence of healthy live births was not significantly different between the standard treatment and intensive treatment groups (15.2% vs. 12.2%; P = 0.40) by the final follow-up time of September 2019. However, women in the intensive group had significantly greater weight loss, compared with the standard group (–6.6% vs. –0.3%; P < .001). Women in the intensive group also showed improvements in metabolic health. Notably, the incidence of metabolic syndrome dropped from 53.6% to 49.4% in the standard group, compared with a decrease from 52.8% to 32.2% in the intensive group over the 16-week study period, the researchers wrote.

Gastrointestinal side effects were significantly more common in the intensive group, but these were consistent with documented side effects of the weight loss medication used (Orlistat).

First-trimester pregnancy loss was higher in the intensive group, compared with the standard group (33.3% vs. 23.7%), but the difference was not significant. Most pregnancy complications, including preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes had nonsignificant improvements in the intensive group, compared with the standard group. Similarly, nonsignificant improvements were noted in the intervention group for intrauterine growth restriction and admission to the neonatal ICU.

Limitations of the study included the relatively small number of pregnancies, which prevented assessment of rare complications in subgroups, and the challenge of matching control interventions, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the focus on women with unexplained infertility, the inclusion of a comparison group, and the collection of data on complications after conception, they wrote.

Avenues for future research include interventions of different duration and intensity prior to conception, which may improve outcomes, the researchers said in their discussion of the findings. “A period of weight stabilization and maintenance after a weight-loss intervention prior to commencing infertility therapy is worth exploring,” they noted, but couples eager to conceive may be reluctant to wait for a weight-loss intervention, they added.

“Our findings directly impact current standards of clinical care, where women who are obese with unexplained infertility are to our knowledge routinely counseled to lose weight prior to initiation of infertility treatment,” they concluded.

Data may inform patient discussions

The current study is important because a large amount of previous research has shown an association between obesity and decreased fecundity in women and men, Mark P. Trolice, MD, of the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and director of the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., said in an interview.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the prevalence of obesity in the United States remains more than 40%, said Dr. Trolice. “Patients and physicians would benefit from clarity of obesity’s effect, if any, on reproduction,” he noted.

In contrast to the authors’ hypothesis, “the study did not find a difference in the live birth rate following up to three cycles of intrauterine insemination (IUI) between an intensive weight loss group [and] women who exercised without weight loss,” said Dr. Trolice. “Prior to this study, many reports suggested a decline in fertility with elevations in BMI, particularly during fertility treatment,” he added.

The take-home message from the current study is a that an elevated BMI, while possibly increasing the risks of metabolic disorders, did not appear to impact fecundity, he said.

The authors therefore concluded, “There is not strong evidence to recommend weight loss prior to conception in women who are obese with unexplained infertility,” Dr. Trolice said.

Regardless of the potential effect of preconception weight loss on fertility, barriers to starting a weight loss program include a woman’s eagerness to move forward with fertility treatments without waiting for weight loss, Dr. Trolice noted. “By the time a woman reaches an infertility specialist, she has been trying to conceive for at least 1 year,” he said. “At the initial consultation, these patients are anxious to undergo necessary additional diagnostic testing followed by treatment. Consequently, initiation of a weight-loss program is viewed as a delay toward the goal of family building,” he explained.

“More research is needed to demonstrate the safety of intensive weight loss preconception,” said Dr. Trolice. However, he said, “the issue of elevated BMI and increased risk of pregnancy complications remains, but this study provides important information for providers regarding counseling their patients desiring pregnancy.”

The study was supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Nutrisystem provided discounted coupons for food allotments in the standardized treatment group, and FitBit provided the study organizers with discounted Fitbits for activity monitoring. Lead author Dr. Legro disclosed consulting fees from InSupp, Ferring, Bayer, Abbvie and Fractyl, and research sponsorship from Guerbet and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Trolice had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Ob.Gyn News.

An intensive weight-loss intervention prior to conception had no effect on birth rates in women with obesity and unexplained infertility, compared with a standard weight-maintenance program, based on data from nearly 400 women.

Obese women experiencing infertility are often counseled to lose weight before attempting fertility treatments in order to improve outcomes based on epidemiologic evidence of an association between obesity and infertility, but data to support this advice are limited, wrote Richard S. Legro, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and colleagues.

The researchers proposed that a more intensive preconception weight loss intervention followed by infertility treatment would be more likely to yield a healthy live birth, compared with a standard weight maintenance intervention.

In an open-label study published in PLOS Medicine, the researchers randomized 379 women at nine academic centers to a standard lifestyle group that followed a weight-maintenance plan focused on physical activity, but not weight loss; or an intensive intervention of diet and medication with a target weight loss of 7%. Both interventions lasted for 16 weeks between July 2015 and July 2018. After the interventions, patients in both groups underwent standardized empiric fertility treatment with three cycles of ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination.

The primary outcome was a live birth at 37 weeks’ gestation or later, with no congenital abnormalities and a birth weight between 2,500 g and 4,000 g. Baseline characteristics including age, education level, race, and body mass index (BMI) were similar between the groups.

The incidence of healthy live births was not significantly different between the standard treatment and intensive treatment groups (15.2% vs. 12.2%; P = 0.40) by the final follow-up time of September 2019. However, women in the intensive group had significantly greater weight loss, compared with the standard group (–6.6% vs. –0.3%; P < .001). Women in the intensive group also showed improvements in metabolic health. Notably, the incidence of metabolic syndrome dropped from 53.6% to 49.4% in the standard group, compared with a decrease from 52.8% to 32.2% in the intensive group over the 16-week study period, the researchers wrote.

Gastrointestinal side effects were significantly more common in the intensive group, but these were consistent with documented side effects of the weight loss medication used (Orlistat).

First-trimester pregnancy loss was higher in the intensive group, compared with the standard group (33.3% vs. 23.7%), but the difference was not significant. Most pregnancy complications, including preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes had nonsignificant improvements in the intensive group, compared with the standard group. Similarly, nonsignificant improvements were noted in the intervention group for intrauterine growth restriction and admission to the neonatal ICU.

Limitations of the study included the relatively small number of pregnancies, which prevented assessment of rare complications in subgroups, and the challenge of matching control interventions, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the focus on women with unexplained infertility, the inclusion of a comparison group, and the collection of data on complications after conception, they wrote.

Avenues for future research include interventions of different duration and intensity prior to conception, which may improve outcomes, the researchers said in their discussion of the findings. “A period of weight stabilization and maintenance after a weight-loss intervention prior to commencing infertility therapy is worth exploring,” they noted, but couples eager to conceive may be reluctant to wait for a weight-loss intervention, they added.

“Our findings directly impact current standards of clinical care, where women who are obese with unexplained infertility are to our knowledge routinely counseled to lose weight prior to initiation of infertility treatment,” they concluded.

Data may inform patient discussions

The current study is important because a large amount of previous research has shown an association between obesity and decreased fecundity in women and men, Mark P. Trolice, MD, of the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and director of the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., said in an interview.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the prevalence of obesity in the United States remains more than 40%, said Dr. Trolice. “Patients and physicians would benefit from clarity of obesity’s effect, if any, on reproduction,” he noted.

In contrast to the authors’ hypothesis, “the study did not find a difference in the live birth rate following up to three cycles of intrauterine insemination (IUI) between an intensive weight loss group [and] women who exercised without weight loss,” said Dr. Trolice. “Prior to this study, many reports suggested a decline in fertility with elevations in BMI, particularly during fertility treatment,” he added.

The take-home message from the current study is a that an elevated BMI, while possibly increasing the risks of metabolic disorders, did not appear to impact fecundity, he said.

The authors therefore concluded, “There is not strong evidence to recommend weight loss prior to conception in women who are obese with unexplained infertility,” Dr. Trolice said.

Regardless of the potential effect of preconception weight loss on fertility, barriers to starting a weight loss program include a woman’s eagerness to move forward with fertility treatments without waiting for weight loss, Dr. Trolice noted. “By the time a woman reaches an infertility specialist, she has been trying to conceive for at least 1 year,” he said. “At the initial consultation, these patients are anxious to undergo necessary additional diagnostic testing followed by treatment. Consequently, initiation of a weight-loss program is viewed as a delay toward the goal of family building,” he explained.

“More research is needed to demonstrate the safety of intensive weight loss preconception,” said Dr. Trolice. However, he said, “the issue of elevated BMI and increased risk of pregnancy complications remains, but this study provides important information for providers regarding counseling their patients desiring pregnancy.”

The study was supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Nutrisystem provided discounted coupons for food allotments in the standardized treatment group, and FitBit provided the study organizers with discounted Fitbits for activity monitoring. Lead author Dr. Legro disclosed consulting fees from InSupp, Ferring, Bayer, Abbvie and Fractyl, and research sponsorship from Guerbet and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Trolice had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Ob.Gyn News.

An intensive weight-loss intervention prior to conception had no effect on birth rates in women with obesity and unexplained infertility, compared with a standard weight-maintenance program, based on data from nearly 400 women.

Obese women experiencing infertility are often counseled to lose weight before attempting fertility treatments in order to improve outcomes based on epidemiologic evidence of an association between obesity and infertility, but data to support this advice are limited, wrote Richard S. Legro, MD, of Penn State University, Hershey, and colleagues.

The researchers proposed that a more intensive preconception weight loss intervention followed by infertility treatment would be more likely to yield a healthy live birth, compared with a standard weight maintenance intervention.

In an open-label study published in PLOS Medicine, the researchers randomized 379 women at nine academic centers to a standard lifestyle group that followed a weight-maintenance plan focused on physical activity, but not weight loss; or an intensive intervention of diet and medication with a target weight loss of 7%. Both interventions lasted for 16 weeks between July 2015 and July 2018. After the interventions, patients in both groups underwent standardized empiric fertility treatment with three cycles of ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination.

The primary outcome was a live birth at 37 weeks’ gestation or later, with no congenital abnormalities and a birth weight between 2,500 g and 4,000 g. Baseline characteristics including age, education level, race, and body mass index (BMI) were similar between the groups.

The incidence of healthy live births was not significantly different between the standard treatment and intensive treatment groups (15.2% vs. 12.2%; P = 0.40) by the final follow-up time of September 2019. However, women in the intensive group had significantly greater weight loss, compared with the standard group (–6.6% vs. –0.3%; P < .001). Women in the intensive group also showed improvements in metabolic health. Notably, the incidence of metabolic syndrome dropped from 53.6% to 49.4% in the standard group, compared with a decrease from 52.8% to 32.2% in the intensive group over the 16-week study period, the researchers wrote.

Gastrointestinal side effects were significantly more common in the intensive group, but these were consistent with documented side effects of the weight loss medication used (Orlistat).

First-trimester pregnancy loss was higher in the intensive group, compared with the standard group (33.3% vs. 23.7%), but the difference was not significant. Most pregnancy complications, including preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes had nonsignificant improvements in the intensive group, compared with the standard group. Similarly, nonsignificant improvements were noted in the intervention group for intrauterine growth restriction and admission to the neonatal ICU.

Limitations of the study included the relatively small number of pregnancies, which prevented assessment of rare complications in subgroups, and the challenge of matching control interventions, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the focus on women with unexplained infertility, the inclusion of a comparison group, and the collection of data on complications after conception, they wrote.

Avenues for future research include interventions of different duration and intensity prior to conception, which may improve outcomes, the researchers said in their discussion of the findings. “A period of weight stabilization and maintenance after a weight-loss intervention prior to commencing infertility therapy is worth exploring,” they noted, but couples eager to conceive may be reluctant to wait for a weight-loss intervention, they added.

“Our findings directly impact current standards of clinical care, where women who are obese with unexplained infertility are to our knowledge routinely counseled to lose weight prior to initiation of infertility treatment,” they concluded.

Data may inform patient discussions

The current study is important because a large amount of previous research has shown an association between obesity and decreased fecundity in women and men, Mark P. Trolice, MD, of the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and director of the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., said in an interview.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the prevalence of obesity in the United States remains more than 40%, said Dr. Trolice. “Patients and physicians would benefit from clarity of obesity’s effect, if any, on reproduction,” he noted.

In contrast to the authors’ hypothesis, “the study did not find a difference in the live birth rate following up to three cycles of intrauterine insemination (IUI) between an intensive weight loss group [and] women who exercised without weight loss,” said Dr. Trolice. “Prior to this study, many reports suggested a decline in fertility with elevations in BMI, particularly during fertility treatment,” he added.

The take-home message from the current study is a that an elevated BMI, while possibly increasing the risks of metabolic disorders, did not appear to impact fecundity, he said.

The authors therefore concluded, “There is not strong evidence to recommend weight loss prior to conception in women who are obese with unexplained infertility,” Dr. Trolice said.

Regardless of the potential effect of preconception weight loss on fertility, barriers to starting a weight loss program include a woman’s eagerness to move forward with fertility treatments without waiting for weight loss, Dr. Trolice noted. “By the time a woman reaches an infertility specialist, she has been trying to conceive for at least 1 year,” he said. “At the initial consultation, these patients are anxious to undergo necessary additional diagnostic testing followed by treatment. Consequently, initiation of a weight-loss program is viewed as a delay toward the goal of family building,” he explained.

“More research is needed to demonstrate the safety of intensive weight loss preconception,” said Dr. Trolice. However, he said, “the issue of elevated BMI and increased risk of pregnancy complications remains, but this study provides important information for providers regarding counseling their patients desiring pregnancy.”

The study was supported by multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Nutrisystem provided discounted coupons for food allotments in the standardized treatment group, and FitBit provided the study organizers with discounted Fitbits for activity monitoring. Lead author Dr. Legro disclosed consulting fees from InSupp, Ferring, Bayer, Abbvie and Fractyl, and research sponsorship from Guerbet and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Trolice had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Ob.Gyn News.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Unraveling plaque changes in CAD With elevated Lp(a)

New research suggests serial coronary CT angiography (CCTA) can provide novel insights into the association between lipoprotein(a) and plaque progression over time in patients with advanced coronary artery disease.

Researchers examined data from 191 individuals with multivessel coronary disease receiving preventive statin (95%) and antiplatelet (100%) therapy in the single-center Scottish DIAMOND trial and compared CCTA at baseline and 12 months available for 160 patients.

As reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, patients with high Lp(a), defined as at least 70 mg/dL, had higher baseline high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and ASSIGN scores than those with low Lp(a) but had comparable coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and total, calcific, noncalcific, and low-attenuation plaque (LAP) volumes.

At 1 year, however, LAP volume – a marker for necrotic core – increased by 26.2 mm3 in the high-Lp(a) group and decreased by –0.7 mm3 in the low-Lp(a) group (P = .020).

There was no significant difference in change in total, calcific, and noncalcific plaque volumes between groups.

In multivariate linear regression analysis adjusting for body mass index, ASSIGN score, and segment involvement score, LAP volume increased by 10.5% for each 50 mg/dL increment in Lp(a) (P = .034).

“It’s an exciting observation, because we’ve done previous studies where we’ve demonstrated the association of that particular plaque type with future myocardial infarction,” senior author Marc R. Dweck, MD, PhD, University of Amsterdam, told this news organization. “So, you’ve potentially got an explanation for the adverse prognosis associated with high lipoprotein(a) and its link to cardiovascular events and, in particular, myocardial infarction.”

The team’s recent SCOT-HEART analysis found that LAP burden was a stronger predictor of myocardial infarction (MI) than cardiovascular risk scores, stenosis severity, and CAC scoring, with MI risk nearly five-fold higher if LAP was above 4%.

As to why total, calcific, and noncalcific plaque volumes didn’t change significantly on repeat CCTA in the present study, Dr. Dweck said it’s possible that the sample was too small and follow-up too short but also that “total plaque volume is really dominated by the fibrous plaque, which doesn’t appear affected by Lp(a).” Nevertheless, Lp(a)’s effect on low-attenuation plaque was clearly present and supported by the change in fibro-fatty plaque, the next-most unstable plaque type.

At 1 year, fibro-fatty plaque volume was 55.0 mm3 in the high-Lp(a) group versus –25.0 mm3 in the low-Lp(a) group (P = .020).

Lp(a) was associated with fibro-fatty plaque progression in univariate analysis (β = 6.7%; P = .034) and showed a trend in multivariable analysis (β = 6.0%; P = .062).

“This study shows you can track changes in plaque over time and highlight important disease mechanisms and use them to understand the pathology of the disease,” Dr. Dweck said. “I’m very encouraged by this.”

What’s novel in the present study is that “it represents the beginning of our understanding of the role of Lp(a) in plaque progression,” Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, and Jagat Narula, MD, PhD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, say in an accompanying commentary.

They note that prior studies, including the Dallas Heart Study, have struggled to find a strong association between Lp(a) with the extent or progression of CAC, despite elevated Lp(a) and CAC identifying higher-risk patients.

Similarly, a meta-analysis of intravascular ultrasound trials turned up only a 1.2% absolute difference in atheroma volume in patients with elevated Lp(a), and a recent optical coherence tomography study found an association of Lp(a) with thin-cap fibroatheromas but not lipid core.

With just 36 patients with elevated Lp(a), however, the current findings need validation in a larger data set, Dr. Tsimikas and Dr. Narula say.

Although Lp(a) is genetically elevated in about one in five individuals and measurement is recommended in European dyslipidemia guidelines, testing rates are low, in part because the argument has been that there are no Lp(a)-lowering therapies available, Dr. Dweck observed. That may change with the phase 3 cardiovascular outcomes Lp(a)HORIZON trial, which follows strong phase 2 results with the antisense agent AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx and is enrolling patients similar to the current cohort.

“Ultimately it comes down to that fundamental thing, that you need an action once you’ve done the test and then insurers will be happy to pay for it and clinicians will ask for it. That’s why that trial is so important,” Dr. Dweck said.

Dr. Tsimikas and Dr. Narula also point to the eagerly awaited results of that trial, expected in 2025. “A positive trial is likely to lead to additional trials and new drugs that may reinvigorate the use of imaging modalities that could go beyond plaque volume and atherosclerosis to also predict clinically relevant inflammation and atherothrombosis,” they conclude.

Dr. Dweck is supported by the British Heart Foundation and is the recipient of the Sir Jules Thorn Award for Biomedical Research 2015; has received speaker fees from Pfizer and Novartis; and has received consultancy fees from Novartis, Jupiter Bioventures, and Silence Therapeutics. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the paper. Dr. Tsimikas has a dual appointment at the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) and Ionis Pharmaceuticals; is a coinventor and receives royalties from patents owned by UCSD; and is a cofounder and has an equity interest in Oxitope and its affiliates, Kleanthi Diagnostics, and Covicept Therapeutics. Dr. Narula reports having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research suggests serial coronary CT angiography (CCTA) can provide novel insights into the association between lipoprotein(a) and plaque progression over time in patients with advanced coronary artery disease.

Researchers examined data from 191 individuals with multivessel coronary disease receiving preventive statin (95%) and antiplatelet (100%) therapy in the single-center Scottish DIAMOND trial and compared CCTA at baseline and 12 months available for 160 patients.

As reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, patients with high Lp(a), defined as at least 70 mg/dL, had higher baseline high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and ASSIGN scores than those with low Lp(a) but had comparable coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and total, calcific, noncalcific, and low-attenuation plaque (LAP) volumes.

At 1 year, however, LAP volume – a marker for necrotic core – increased by 26.2 mm3 in the high-Lp(a) group and decreased by –0.7 mm3 in the low-Lp(a) group (P = .020).

There was no significant difference in change in total, calcific, and noncalcific plaque volumes between groups.

In multivariate linear regression analysis adjusting for body mass index, ASSIGN score, and segment involvement score, LAP volume increased by 10.5% for each 50 mg/dL increment in Lp(a) (P = .034).

“It’s an exciting observation, because we’ve done previous studies where we’ve demonstrated the association of that particular plaque type with future myocardial infarction,” senior author Marc R. Dweck, MD, PhD, University of Amsterdam, told this news organization. “So, you’ve potentially got an explanation for the adverse prognosis associated with high lipoprotein(a) and its link to cardiovascular events and, in particular, myocardial infarction.”

The team’s recent SCOT-HEART analysis found that LAP burden was a stronger predictor of myocardial infarction (MI) than cardiovascular risk scores, stenosis severity, and CAC scoring, with MI risk nearly five-fold higher if LAP was above 4%.

As to why total, calcific, and noncalcific plaque volumes didn’t change significantly on repeat CCTA in the present study, Dr. Dweck said it’s possible that the sample was too small and follow-up too short but also that “total plaque volume is really dominated by the fibrous plaque, which doesn’t appear affected by Lp(a).” Nevertheless, Lp(a)’s effect on low-attenuation plaque was clearly present and supported by the change in fibro-fatty plaque, the next-most unstable plaque type.

At 1 year, fibro-fatty plaque volume was 55.0 mm3 in the high-Lp(a) group versus –25.0 mm3 in the low-Lp(a) group (P = .020).

Lp(a) was associated with fibro-fatty plaque progression in univariate analysis (β = 6.7%; P = .034) and showed a trend in multivariable analysis (β = 6.0%; P = .062).

“This study shows you can track changes in plaque over time and highlight important disease mechanisms and use them to understand the pathology of the disease,” Dr. Dweck said. “I’m very encouraged by this.”

What’s novel in the present study is that “it represents the beginning of our understanding of the role of Lp(a) in plaque progression,” Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, and Jagat Narula, MD, PhD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, say in an accompanying commentary.

They note that prior studies, including the Dallas Heart Study, have struggled to find a strong association between Lp(a) with the extent or progression of CAC, despite elevated Lp(a) and CAC identifying higher-risk patients.

Similarly, a meta-analysis of intravascular ultrasound trials turned up only a 1.2% absolute difference in atheroma volume in patients with elevated Lp(a), and a recent optical coherence tomography study found an association of Lp(a) with thin-cap fibroatheromas but not lipid core.

With just 36 patients with elevated Lp(a), however, the current findings need validation in a larger data set, Dr. Tsimikas and Dr. Narula say.

Although Lp(a) is genetically elevated in about one in five individuals and measurement is recommended in European dyslipidemia guidelines, testing rates are low, in part because the argument has been that there are no Lp(a)-lowering therapies available, Dr. Dweck observed. That may change with the phase 3 cardiovascular outcomes Lp(a)HORIZON trial, which follows strong phase 2 results with the antisense agent AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx and is enrolling patients similar to the current cohort.

“Ultimately it comes down to that fundamental thing, that you need an action once you’ve done the test and then insurers will be happy to pay for it and clinicians will ask for it. That’s why that trial is so important,” Dr. Dweck said.

Dr. Tsimikas and Dr. Narula also point to the eagerly awaited results of that trial, expected in 2025. “A positive trial is likely to lead to additional trials and new drugs that may reinvigorate the use of imaging modalities that could go beyond plaque volume and atherosclerosis to also predict clinically relevant inflammation and atherothrombosis,” they conclude.

Dr. Dweck is supported by the British Heart Foundation and is the recipient of the Sir Jules Thorn Award for Biomedical Research 2015; has received speaker fees from Pfizer and Novartis; and has received consultancy fees from Novartis, Jupiter Bioventures, and Silence Therapeutics. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the paper. Dr. Tsimikas has a dual appointment at the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) and Ionis Pharmaceuticals; is a coinventor and receives royalties from patents owned by UCSD; and is a cofounder and has an equity interest in Oxitope and its affiliates, Kleanthi Diagnostics, and Covicept Therapeutics. Dr. Narula reports having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research suggests serial coronary CT angiography (CCTA) can provide novel insights into the association between lipoprotein(a) and plaque progression over time in patients with advanced coronary artery disease.

Researchers examined data from 191 individuals with multivessel coronary disease receiving preventive statin (95%) and antiplatelet (100%) therapy in the single-center Scottish DIAMOND trial and compared CCTA at baseline and 12 months available for 160 patients.

As reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, patients with high Lp(a), defined as at least 70 mg/dL, had higher baseline high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and ASSIGN scores than those with low Lp(a) but had comparable coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and total, calcific, noncalcific, and low-attenuation plaque (LAP) volumes.

At 1 year, however, LAP volume – a marker for necrotic core – increased by 26.2 mm3 in the high-Lp(a) group and decreased by –0.7 mm3 in the low-Lp(a) group (P = .020).

There was no significant difference in change in total, calcific, and noncalcific plaque volumes between groups.

In multivariate linear regression analysis adjusting for body mass index, ASSIGN score, and segment involvement score, LAP volume increased by 10.5% for each 50 mg/dL increment in Lp(a) (P = .034).

“It’s an exciting observation, because we’ve done previous studies where we’ve demonstrated the association of that particular plaque type with future myocardial infarction,” senior author Marc R. Dweck, MD, PhD, University of Amsterdam, told this news organization. “So, you’ve potentially got an explanation for the adverse prognosis associated with high lipoprotein(a) and its link to cardiovascular events and, in particular, myocardial infarction.”

The team’s recent SCOT-HEART analysis found that LAP burden was a stronger predictor of myocardial infarction (MI) than cardiovascular risk scores, stenosis severity, and CAC scoring, with MI risk nearly five-fold higher if LAP was above 4%.

As to why total, calcific, and noncalcific plaque volumes didn’t change significantly on repeat CCTA in the present study, Dr. Dweck said it’s possible that the sample was too small and follow-up too short but also that “total plaque volume is really dominated by the fibrous plaque, which doesn’t appear affected by Lp(a).” Nevertheless, Lp(a)’s effect on low-attenuation plaque was clearly present and supported by the change in fibro-fatty plaque, the next-most unstable plaque type.

At 1 year, fibro-fatty plaque volume was 55.0 mm3 in the high-Lp(a) group versus –25.0 mm3 in the low-Lp(a) group (P = .020).

Lp(a) was associated with fibro-fatty plaque progression in univariate analysis (β = 6.7%; P = .034) and showed a trend in multivariable analysis (β = 6.0%; P = .062).

“This study shows you can track changes in plaque over time and highlight important disease mechanisms and use them to understand the pathology of the disease,” Dr. Dweck said. “I’m very encouraged by this.”

What’s novel in the present study is that “it represents the beginning of our understanding of the role of Lp(a) in plaque progression,” Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, and Jagat Narula, MD, PhD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, say in an accompanying commentary.

They note that prior studies, including the Dallas Heart Study, have struggled to find a strong association between Lp(a) with the extent or progression of CAC, despite elevated Lp(a) and CAC identifying higher-risk patients.

Similarly, a meta-analysis of intravascular ultrasound trials turned up only a 1.2% absolute difference in atheroma volume in patients with elevated Lp(a), and a recent optical coherence tomography study found an association of Lp(a) with thin-cap fibroatheromas but not lipid core.

With just 36 patients with elevated Lp(a), however, the current findings need validation in a larger data set, Dr. Tsimikas and Dr. Narula say.

Although Lp(a) is genetically elevated in about one in five individuals and measurement is recommended in European dyslipidemia guidelines, testing rates are low, in part because the argument has been that there are no Lp(a)-lowering therapies available, Dr. Dweck observed. That may change with the phase 3 cardiovascular outcomes Lp(a)HORIZON trial, which follows strong phase 2 results with the antisense agent AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx and is enrolling patients similar to the current cohort.

“Ultimately it comes down to that fundamental thing, that you need an action once you’ve done the test and then insurers will be happy to pay for it and clinicians will ask for it. That’s why that trial is so important,” Dr. Dweck said.

Dr. Tsimikas and Dr. Narula also point to the eagerly awaited results of that trial, expected in 2025. “A positive trial is likely to lead to additional trials and new drugs that may reinvigorate the use of imaging modalities that could go beyond plaque volume and atherosclerosis to also predict clinically relevant inflammation and atherothrombosis,” they conclude.

Dr. Dweck is supported by the British Heart Foundation and is the recipient of the Sir Jules Thorn Award for Biomedical Research 2015; has received speaker fees from Pfizer and Novartis; and has received consultancy fees from Novartis, Jupiter Bioventures, and Silence Therapeutics. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the paper. Dr. Tsimikas has a dual appointment at the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) and Ionis Pharmaceuticals; is a coinventor and receives royalties from patents owned by UCSD; and is a cofounder and has an equity interest in Oxitope and its affiliates, Kleanthi Diagnostics, and Covicept Therapeutics. Dr. Narula reports having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

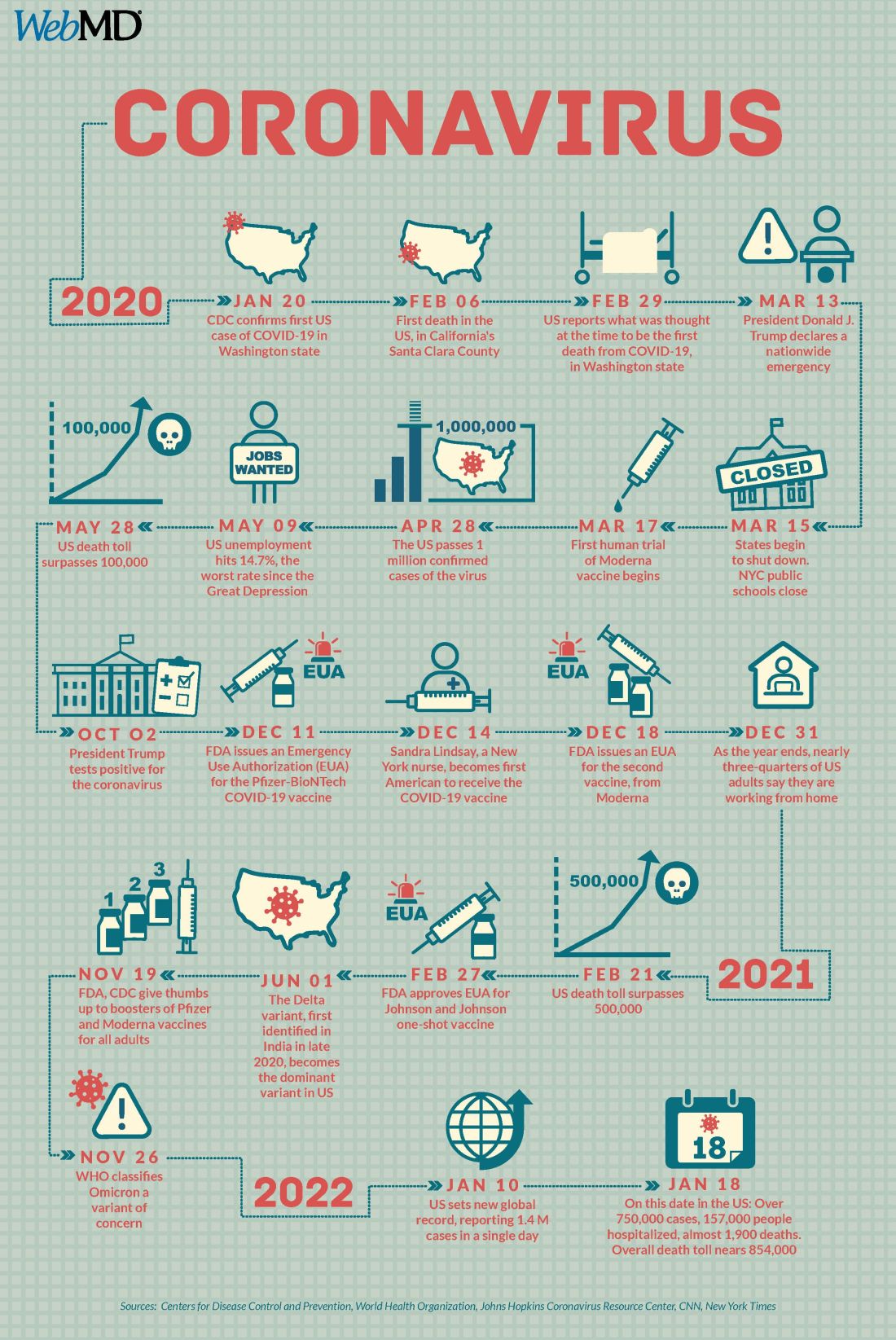

Five things you should know about ‘free’ at-home COVID tests

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

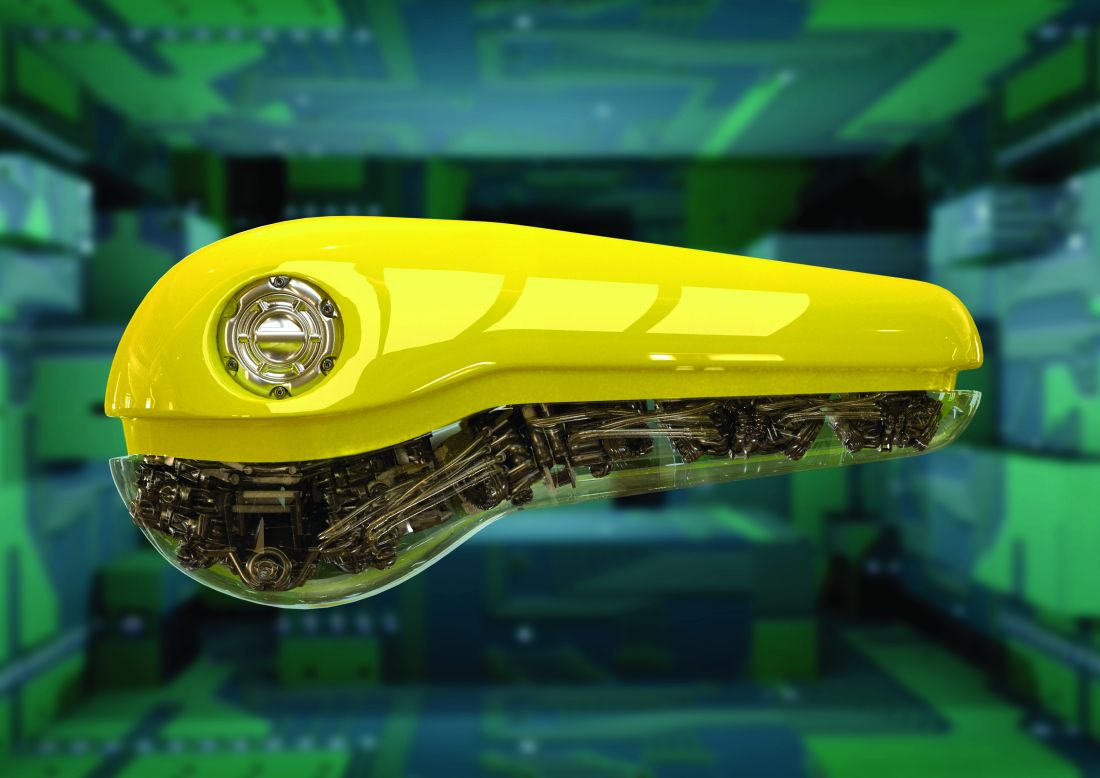

‘Artificial pancreas’ life-changing in kids with type 1 diabetes

A semiautomated insulin delivery system improved glycemic control in young children with type 1 diabetes aged 1-7 years without increasing hypoglycemia.

“Hybrid closed-loop” systems – comprising an insulin pump, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), and software enabling communication that semiautomates insulin delivery based on glucose levels – have been shown to improve glucose control in older children and adults.

The technology, also known as an artificial pancreas, has been less studied in very young children even though it may uniquely benefit them, said the authors of the new study, led by Julia Ware, MD, of the Wellcome Trust–Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science and the University of Cambridge (England). The findings were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Very young children are extremely vulnerable to changes in their blood sugar levels. High levels in particular can have potentially lasting consequences to their brain development. On top of that, diabetes is very challenging to manage in this age group, creating a huge burden for families,” she said in a University of Cambridge statement.

There is “high variability of insulin requirements, marked insulin sensitivity, and unpredictable eating and activity patterns,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

“Caregiver fear of hypoglycemia, particularly overnight, is common and, coupled with young children’s unawareness that hypoglycemia is occurring, contributes to children not meeting the recommended glycemic targets or having difficulty maintaining recommended glycemic control unless caregivers can provide constant monitoring. These issues often lead to ... reduced quality of life for the whole family,” they added.

Except for mealtimes, device is fully automated

The new multicenter, randomized, crossover trial was conducted at seven centers across Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom in 2019-2020.

The trial compared the safety and efficacy of hybrid closed-loop therapy with sensor-augmented pump therapy (that is, without the device communication, as a control). All 74 children used the CamAPS FX hybrid closed-loop system for 16 weeks, and then used the control treatment for 16 weeks. The children were a mean age of 5.6 years and had a baseline hemoglobin A1c of 7.3% (56.6 mmol/mol).

The hybrid closed-loop system consisted of components that are commercially available in Europe: the Sooil insulin pump (Dana Diabecare RS) and the Dexcom G6 CGM, along with an unlocked Samsung Galaxy 8 smartphone housing an app (CamAPS FX, CamDiab) that runs the Cambridge proprietary model predictive control algorithm.

The smartphone communicates wirelessly with both the pump and the CGM transmitter and automatically adjusts the pump’s insulin delivery based on real-time sensor glucose readings. It also issues alarms if glucose levels fall below or rise above user-specified thresholds. This functionality was disabled during the study control periods.

Senior investigator Roman Hovorka, PhD, who developed the CamAPS FX app, explained in the University of Cambridge statement that the app “makes predictions about what it thinks is likely to happen next based on past experience. It learns how much insulin the child needs per day and how this changes at different times of the day.

“It then uses this [information] to adjust insulin levels to help achieve ideal blood sugar levels. Other than at mealtimes, it is fully automated, so parents do not need to continually monitor their child’s blood sugar levels.”

Indeed, the time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) during the 16-week closed-loop period was 8.7 percentage points higher than during the control period (P < .001).

That difference translates to “a clinically meaningful 125 minutes per day,” and represented around three-quarters of their day (71.6%) in the target range, the investigators wrote.

The mean adjusted difference in time spent above 180 mg/dL was 8.5 percentage points lower with the closed-loop, also a significant difference (P < .001). Time spent below 70 mg/dL did not differ significantly between the two interventions (P = .74).

At the end of the study periods, the mean adjusted between-treatment difference in A1c was –0.4 percentage points, significantly lower following the closed-loop, compared with the control period (P < .001).

That percentage point difference (equivalent to 3.9 mmol/mol) “is important in a population of patients who had tight glycemic control at baseline. This result was observed without an increase in the time spent in a hypoglycemic state,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

Median glucose sensor use was 99% during the closed-loop period and 96% during the control periods. During the closed-loop periods, the system was in closed-loop mode 95% of the time.

This finding supports longer-term usability in this age group and compares well with use in older children, they said.

One serious hypoglycemic episode, attributed to parental error rather than system malfunction, occurred during the closed-loop period. There were no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis. Rates of other adverse events didn’t differ between the two periods.

“CamAPS FX led to improvements in several measures, including hyperglycemia and average blood sugar levels, without increasing the risk of hypos. This is likely to have important benefits for those children who use it,” Dr. Ware summarized.

Sleep quality could improve for children and caregivers

Reductions in time spent in hyperglycemia without increasing hypoglycemia could minimize the risk for neurocognitive deficits that have been reported among young children with type 1 diabetes, the authors speculated.

In addition, they noted that because 80% of overnight sensor readings were within target range and less than 3% were below 70 mg/dL, sleep quality could improve for both the children and their parents. This, in turn, “would confer associated quality of life benefits.”

“Parents have described our artificial pancreas as ‘life changing’ as it meant they were able to relax and spend less time worrying about their child’s blood sugar levels, particularly at nighttime. They tell us it gives them more time to do what any ‘normal’ family can do, to play and do fun things with their children,” observed Dr. Ware.

The CamAPS FX has been commercialized by CamDiab, a spin-out company set up by Dr. Hovorka. It is currently available through several NHS trusts across the United Kingdom, including Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and is expected to be more widely available soon.

The study was supported by the European Commission within the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and JDRF. Dr. Ware had no further disclosures. Dr. Hovorka has reported acting as consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, BD, Dexcom, being a speaker for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, and receiving royalty payments from B. Braun for software. He is director of CamDiab.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A semiautomated insulin delivery system improved glycemic control in young children with type 1 diabetes aged 1-7 years without increasing hypoglycemia.

“Hybrid closed-loop” systems – comprising an insulin pump, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), and software enabling communication that semiautomates insulin delivery based on glucose levels – have been shown to improve glucose control in older children and adults.

The technology, also known as an artificial pancreas, has been less studied in very young children even though it may uniquely benefit them, said the authors of the new study, led by Julia Ware, MD, of the Wellcome Trust–Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science and the University of Cambridge (England). The findings were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Very young children are extremely vulnerable to changes in their blood sugar levels. High levels in particular can have potentially lasting consequences to their brain development. On top of that, diabetes is very challenging to manage in this age group, creating a huge burden for families,” she said in a University of Cambridge statement.

There is “high variability of insulin requirements, marked insulin sensitivity, and unpredictable eating and activity patterns,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

“Caregiver fear of hypoglycemia, particularly overnight, is common and, coupled with young children’s unawareness that hypoglycemia is occurring, contributes to children not meeting the recommended glycemic targets or having difficulty maintaining recommended glycemic control unless caregivers can provide constant monitoring. These issues often lead to ... reduced quality of life for the whole family,” they added.

Except for mealtimes, device is fully automated

The new multicenter, randomized, crossover trial was conducted at seven centers across Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom in 2019-2020.

The trial compared the safety and efficacy of hybrid closed-loop therapy with sensor-augmented pump therapy (that is, without the device communication, as a control). All 74 children used the CamAPS FX hybrid closed-loop system for 16 weeks, and then used the control treatment for 16 weeks. The children were a mean age of 5.6 years and had a baseline hemoglobin A1c of 7.3% (56.6 mmol/mol).

The hybrid closed-loop system consisted of components that are commercially available in Europe: the Sooil insulin pump (Dana Diabecare RS) and the Dexcom G6 CGM, along with an unlocked Samsung Galaxy 8 smartphone housing an app (CamAPS FX, CamDiab) that runs the Cambridge proprietary model predictive control algorithm.

The smartphone communicates wirelessly with both the pump and the CGM transmitter and automatically adjusts the pump’s insulin delivery based on real-time sensor glucose readings. It also issues alarms if glucose levels fall below or rise above user-specified thresholds. This functionality was disabled during the study control periods.

Senior investigator Roman Hovorka, PhD, who developed the CamAPS FX app, explained in the University of Cambridge statement that the app “makes predictions about what it thinks is likely to happen next based on past experience. It learns how much insulin the child needs per day and how this changes at different times of the day.

“It then uses this [information] to adjust insulin levels to help achieve ideal blood sugar levels. Other than at mealtimes, it is fully automated, so parents do not need to continually monitor their child’s blood sugar levels.”

Indeed, the time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) during the 16-week closed-loop period was 8.7 percentage points higher than during the control period (P < .001).

That difference translates to “a clinically meaningful 125 minutes per day,” and represented around three-quarters of their day (71.6%) in the target range, the investigators wrote.

The mean adjusted difference in time spent above 180 mg/dL was 8.5 percentage points lower with the closed-loop, also a significant difference (P < .001). Time spent below 70 mg/dL did not differ significantly between the two interventions (P = .74).

At the end of the study periods, the mean adjusted between-treatment difference in A1c was –0.4 percentage points, significantly lower following the closed-loop, compared with the control period (P < .001).

That percentage point difference (equivalent to 3.9 mmol/mol) “is important in a population of patients who had tight glycemic control at baseline. This result was observed without an increase in the time spent in a hypoglycemic state,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

Median glucose sensor use was 99% during the closed-loop period and 96% during the control periods. During the closed-loop periods, the system was in closed-loop mode 95% of the time.

This finding supports longer-term usability in this age group and compares well with use in older children, they said.

One serious hypoglycemic episode, attributed to parental error rather than system malfunction, occurred during the closed-loop period. There were no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis. Rates of other adverse events didn’t differ between the two periods.

“CamAPS FX led to improvements in several measures, including hyperglycemia and average blood sugar levels, without increasing the risk of hypos. This is likely to have important benefits for those children who use it,” Dr. Ware summarized.

Sleep quality could improve for children and caregivers

Reductions in time spent in hyperglycemia without increasing hypoglycemia could minimize the risk for neurocognitive deficits that have been reported among young children with type 1 diabetes, the authors speculated.

In addition, they noted that because 80% of overnight sensor readings were within target range and less than 3% were below 70 mg/dL, sleep quality could improve for both the children and their parents. This, in turn, “would confer associated quality of life benefits.”

“Parents have described our artificial pancreas as ‘life changing’ as it meant they were able to relax and spend less time worrying about their child’s blood sugar levels, particularly at nighttime. They tell us it gives them more time to do what any ‘normal’ family can do, to play and do fun things with their children,” observed Dr. Ware.

The CamAPS FX has been commercialized by CamDiab, a spin-out company set up by Dr. Hovorka. It is currently available through several NHS trusts across the United Kingdom, including Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and is expected to be more widely available soon.

The study was supported by the European Commission within the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and JDRF. Dr. Ware had no further disclosures. Dr. Hovorka has reported acting as consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, BD, Dexcom, being a speaker for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, and receiving royalty payments from B. Braun for software. He is director of CamDiab.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A semiautomated insulin delivery system improved glycemic control in young children with type 1 diabetes aged 1-7 years without increasing hypoglycemia.

“Hybrid closed-loop” systems – comprising an insulin pump, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), and software enabling communication that semiautomates insulin delivery based on glucose levels – have been shown to improve glucose control in older children and adults.

The technology, also known as an artificial pancreas, has been less studied in very young children even though it may uniquely benefit them, said the authors of the new study, led by Julia Ware, MD, of the Wellcome Trust–Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science and the University of Cambridge (England). The findings were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Very young children are extremely vulnerable to changes in their blood sugar levels. High levels in particular can have potentially lasting consequences to their brain development. On top of that, diabetes is very challenging to manage in this age group, creating a huge burden for families,” she said in a University of Cambridge statement.

There is “high variability of insulin requirements, marked insulin sensitivity, and unpredictable eating and activity patterns,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

“Caregiver fear of hypoglycemia, particularly overnight, is common and, coupled with young children’s unawareness that hypoglycemia is occurring, contributes to children not meeting the recommended glycemic targets or having difficulty maintaining recommended glycemic control unless caregivers can provide constant monitoring. These issues often lead to ... reduced quality of life for the whole family,” they added.

Except for mealtimes, device is fully automated

The new multicenter, randomized, crossover trial was conducted at seven centers across Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom in 2019-2020.

The trial compared the safety and efficacy of hybrid closed-loop therapy with sensor-augmented pump therapy (that is, without the device communication, as a control). All 74 children used the CamAPS FX hybrid closed-loop system for 16 weeks, and then used the control treatment for 16 weeks. The children were a mean age of 5.6 years and had a baseline hemoglobin A1c of 7.3% (56.6 mmol/mol).

The hybrid closed-loop system consisted of components that are commercially available in Europe: the Sooil insulin pump (Dana Diabecare RS) and the Dexcom G6 CGM, along with an unlocked Samsung Galaxy 8 smartphone housing an app (CamAPS FX, CamDiab) that runs the Cambridge proprietary model predictive control algorithm.

The smartphone communicates wirelessly with both the pump and the CGM transmitter and automatically adjusts the pump’s insulin delivery based on real-time sensor glucose readings. It also issues alarms if glucose levels fall below or rise above user-specified thresholds. This functionality was disabled during the study control periods.

Senior investigator Roman Hovorka, PhD, who developed the CamAPS FX app, explained in the University of Cambridge statement that the app “makes predictions about what it thinks is likely to happen next based on past experience. It learns how much insulin the child needs per day and how this changes at different times of the day.

“It then uses this [information] to adjust insulin levels to help achieve ideal blood sugar levels. Other than at mealtimes, it is fully automated, so parents do not need to continually monitor their child’s blood sugar levels.”

Indeed, the time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) during the 16-week closed-loop period was 8.7 percentage points higher than during the control period (P < .001).

That difference translates to “a clinically meaningful 125 minutes per day,” and represented around three-quarters of their day (71.6%) in the target range, the investigators wrote.

The mean adjusted difference in time spent above 180 mg/dL was 8.5 percentage points lower with the closed-loop, also a significant difference (P < .001). Time spent below 70 mg/dL did not differ significantly between the two interventions (P = .74).

At the end of the study periods, the mean adjusted between-treatment difference in A1c was –0.4 percentage points, significantly lower following the closed-loop, compared with the control period (P < .001).

That percentage point difference (equivalent to 3.9 mmol/mol) “is important in a population of patients who had tight glycemic control at baseline. This result was observed without an increase in the time spent in a hypoglycemic state,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

Median glucose sensor use was 99% during the closed-loop period and 96% during the control periods. During the closed-loop periods, the system was in closed-loop mode 95% of the time.

This finding supports longer-term usability in this age group and compares well with use in older children, they said.

One serious hypoglycemic episode, attributed to parental error rather than system malfunction, occurred during the closed-loop period. There were no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis. Rates of other adverse events didn’t differ between the two periods.

“CamAPS FX led to improvements in several measures, including hyperglycemia and average blood sugar levels, without increasing the risk of hypos. This is likely to have important benefits for those children who use it,” Dr. Ware summarized.

Sleep quality could improve for children and caregivers

Reductions in time spent in hyperglycemia without increasing hypoglycemia could minimize the risk for neurocognitive deficits that have been reported among young children with type 1 diabetes, the authors speculated.

In addition, they noted that because 80% of overnight sensor readings were within target range and less than 3% were below 70 mg/dL, sleep quality could improve for both the children and their parents. This, in turn, “would confer associated quality of life benefits.”

“Parents have described our artificial pancreas as ‘life changing’ as it meant they were able to relax and spend less time worrying about their child’s blood sugar levels, particularly at nighttime. They tell us it gives them more time to do what any ‘normal’ family can do, to play and do fun things with their children,” observed Dr. Ware.

The CamAPS FX has been commercialized by CamDiab, a spin-out company set up by Dr. Hovorka. It is currently available through several NHS trusts across the United Kingdom, including Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and is expected to be more widely available soon.

The study was supported by the European Commission within the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and JDRF. Dr. Ware had no further disclosures. Dr. Hovorka has reported acting as consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, BD, Dexcom, being a speaker for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, and receiving royalty payments from B. Braun for software. He is director of CamDiab.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

COVID at 2 years: Preparing for a different ‘normal’

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States is still breaking records in hospital overcrowding and new cases.

The United States is logging nearly 800,000 cases a day, hospitals are starting to fray, and deaths have topped 850,000. Schools oscillate from remote to in-person learning, polarizing communities.

The vaccines are lifesaving for many, yet frustration mounts as the numbers of unvaccinated people in this country stays relatively stagnant (63% in the United States are fully vaccinated) and other parts of the world have seen hardly a single dose. Africa has the slowest vaccination rate among continents, with only 14% of the population receiving one shot, according to the New York Times tracker.

Yet