User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

A call for psychiatrists with tardive dyskinesia expertise

The CURESZ Foundation was founded in 2016 to bring hope to people suffering from schizophrenia and those who love and care for them. CURESZ was established by Bethany Yeiser and her psychiatrist, Current Psychiatry Editor-in-Chief Henry Nasrallah, MD, and was inspired by Bethany's complete recovery from schizophrenia after 4 years of delusions, hallucinations, homelessness, and disability. Bethany returned to her normal life and graduated from college with honors, thanks to clozapine, which cured her symptoms when several other medications did not work (for more of Bethany’s story, see From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2014, p. 21,24-25).

We previously assembled a panel of clozapine experts to whom the CURESZ Foundation would refer patients who have never had a trial of clozapine despite ongoing delusions or hallucinations. We now have a panel of 80 clozapine experts around the country who are willing to receive referrals.

In an unexpected turn of events, after several years of receiving clozapine, Bethany developed tardive dyskinesia (TD) which, fortunately, was successfully treated. Bethany would not have been able to recover from her TD had it not been for the recent FDA approval of effective treatments. The embarrassing personal experience of oro-buccal TD movements that Bethany went through before she improved led her and me to establish a panel of experts in the recognition and treatment of TD around the country. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorders, bipolar disorder and major depression, all of whom receive first or second generation antipsychotic agents, currently have TD that is not being diagnosed or treated.

We are therefore calling for psychiatric practitioners who have had experience in recognizing TD movements and have treated patients with FDA-approved treatments, to contact the CURESZ Foundation. Henry Nasrallah, MD, the Scientific Director of the CURESZ Foundation, who has had many years of federally funded research experience in TD, will serve as the Chair of this TD Panel.

This is a call for readers of Current Psychiatry who are treating TD and who practice in settings that can accommodate additional patients seeking treatment for their involuntary TD muscle movements in their face, trunk, and extremities. We hope to assemble between 50 to 100 experts to join this national TD panel.

If you would like to be a member of this national CURESZ TD Panel, please go to https://curesz.org/tardive-dyskinesia-panel/ and enter your name, email, work address, and office phone number. We will later organize the list by state and city so that patients and families around the country can contact the nearest expert to get an evaluation for assessment and treatment of their TD.

Thank you and we look forward to working with the experts who say “YESZ” to joining the TD Panel, sponsored by the CURESZ Foundation.

The CURESZ Foundation was founded in 2016 to bring hope to people suffering from schizophrenia and those who love and care for them. CURESZ was established by Bethany Yeiser and her psychiatrist, Current Psychiatry Editor-in-Chief Henry Nasrallah, MD, and was inspired by Bethany's complete recovery from schizophrenia after 4 years of delusions, hallucinations, homelessness, and disability. Bethany returned to her normal life and graduated from college with honors, thanks to clozapine, which cured her symptoms when several other medications did not work (for more of Bethany’s story, see From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2014, p. 21,24-25).

We previously assembled a panel of clozapine experts to whom the CURESZ Foundation would refer patients who have never had a trial of clozapine despite ongoing delusions or hallucinations. We now have a panel of 80 clozapine experts around the country who are willing to receive referrals.

In an unexpected turn of events, after several years of receiving clozapine, Bethany developed tardive dyskinesia (TD) which, fortunately, was successfully treated. Bethany would not have been able to recover from her TD had it not been for the recent FDA approval of effective treatments. The embarrassing personal experience of oro-buccal TD movements that Bethany went through before she improved led her and me to establish a panel of experts in the recognition and treatment of TD around the country. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorders, bipolar disorder and major depression, all of whom receive first or second generation antipsychotic agents, currently have TD that is not being diagnosed or treated.

We are therefore calling for psychiatric practitioners who have had experience in recognizing TD movements and have treated patients with FDA-approved treatments, to contact the CURESZ Foundation. Henry Nasrallah, MD, the Scientific Director of the CURESZ Foundation, who has had many years of federally funded research experience in TD, will serve as the Chair of this TD Panel.

This is a call for readers of Current Psychiatry who are treating TD and who practice in settings that can accommodate additional patients seeking treatment for their involuntary TD muscle movements in their face, trunk, and extremities. We hope to assemble between 50 to 100 experts to join this national TD panel.

If you would like to be a member of this national CURESZ TD Panel, please go to https://curesz.org/tardive-dyskinesia-panel/ and enter your name, email, work address, and office phone number. We will later organize the list by state and city so that patients and families around the country can contact the nearest expert to get an evaluation for assessment and treatment of their TD.

Thank you and we look forward to working with the experts who say “YESZ” to joining the TD Panel, sponsored by the CURESZ Foundation.

The CURESZ Foundation was founded in 2016 to bring hope to people suffering from schizophrenia and those who love and care for them. CURESZ was established by Bethany Yeiser and her psychiatrist, Current Psychiatry Editor-in-Chief Henry Nasrallah, MD, and was inspired by Bethany's complete recovery from schizophrenia after 4 years of delusions, hallucinations, homelessness, and disability. Bethany returned to her normal life and graduated from college with honors, thanks to clozapine, which cured her symptoms when several other medications did not work (for more of Bethany’s story, see From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2014, p. 21,24-25).

We previously assembled a panel of clozapine experts to whom the CURESZ Foundation would refer patients who have never had a trial of clozapine despite ongoing delusions or hallucinations. We now have a panel of 80 clozapine experts around the country who are willing to receive referrals.

In an unexpected turn of events, after several years of receiving clozapine, Bethany developed tardive dyskinesia (TD) which, fortunately, was successfully treated. Bethany would not have been able to recover from her TD had it not been for the recent FDA approval of effective treatments. The embarrassing personal experience of oro-buccal TD movements that Bethany went through before she improved led her and me to establish a panel of experts in the recognition and treatment of TD around the country. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorders, bipolar disorder and major depression, all of whom receive first or second generation antipsychotic agents, currently have TD that is not being diagnosed or treated.

We are therefore calling for psychiatric practitioners who have had experience in recognizing TD movements and have treated patients with FDA-approved treatments, to contact the CURESZ Foundation. Henry Nasrallah, MD, the Scientific Director of the CURESZ Foundation, who has had many years of federally funded research experience in TD, will serve as the Chair of this TD Panel.

This is a call for readers of Current Psychiatry who are treating TD and who practice in settings that can accommodate additional patients seeking treatment for their involuntary TD muscle movements in their face, trunk, and extremities. We hope to assemble between 50 to 100 experts to join this national TD panel.

If you would like to be a member of this national CURESZ TD Panel, please go to https://curesz.org/tardive-dyskinesia-panel/ and enter your name, email, work address, and office phone number. We will later organize the list by state and city so that patients and families around the country can contact the nearest expert to get an evaluation for assessment and treatment of their TD.

Thank you and we look forward to working with the experts who say “YESZ” to joining the TD Panel, sponsored by the CURESZ Foundation.

Tardive dyskinesia is theme of awards competition for early career psychiatrists

Important advances in neuroscience and clinical psychiatry have been achieved in recent years, but there are significant gaps in knowledge and much that we don’t understand about the brain and behavior. Further advances depend on cultivating and supporting a new generation of dedicated basic science and clinical investigators. While there is a compelling need to attract, recruit, and encourage talented individuals to pursue scholarly interests, competing life and career demands often prove daunting.

The theme of the competition this year concerning tardive dyskinesia is timely and consistent with the mission of NMSIS to promote knowledge on neurologic side effects of antipsychotic drugs. Tardive dyskinesia can have a negative impact on the social, psychological, and physical well-being of patients; it remains a legacy of past treatment with antipsychotics; it is an increasing concern among an ever widening population of patients receiving even newer antipsychotics; and there are now two Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for the disorder. Early career psychiatrists may have had limited instruction on tardive dyskinesia, which has not received prominent attention in curricular programs in recent years. Thus, in addition to supporting scholarly work and research experience, the 2018 Promising Scholars Award Program aims to promote knowledge and skills in managing patients with tardive dyskinesia.

Specific learning objectives are:

- Participants will learn the steps necessary to prepare a scientific manuscript for publication.

- Participants will review comments by expert referees and learn to incorporate and respond to the peer review process.

- Participants will review the evidence related to the diagnosis and treatment of tardive dyskinesia.

- Participants will be introduced to the spectrum of educational and networking opportunities at the Institute for Psychiatric Services conference.

In the past, this program was very popular and gained national recognition among psychiatric trainees. Numerous submitted papers were accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals after the competition was completed.

Instructions for manuscript preparation are:

- First author must be a student, resident, or fellow.

- Papers should address specific issues related to the theme of tardive dyskinesia and be no longer than 15 double-spaced typed pages in length (excluding references and illustrations).

- Literature reviews, case reports, or studies that are original and newly developed or recently published are acceptable.

- Reviews and feedback will be provided by a panel of academic psychiatrists.

- Papers will be judged on relevance to tardive dyskinesia, originality, scholarship, scientific rigor, valid methodology, clinical significance, and organization.

To participate, papers and curriculum vitae of the first author must be submitted by July 1, 2018, to Dianne Daugherty by email at [email protected]. Winners will be announced by Aug. 10, 2018. For additional information, write to [email protected] or visit www.mhaus.org/nmsis/about-us/what-is-nmsis.

Dr. Caroff, professor of psychiatry, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and at the University of Pennsylvania, both in Philadelphia, is director of the NMSIS. He served as consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, and receives research grant funding from Neurocrine Biosciences.

Important advances in neuroscience and clinical psychiatry have been achieved in recent years, but there are significant gaps in knowledge and much that we don’t understand about the brain and behavior. Further advances depend on cultivating and supporting a new generation of dedicated basic science and clinical investigators. While there is a compelling need to attract, recruit, and encourage talented individuals to pursue scholarly interests, competing life and career demands often prove daunting.

The theme of the competition this year concerning tardive dyskinesia is timely and consistent with the mission of NMSIS to promote knowledge on neurologic side effects of antipsychotic drugs. Tardive dyskinesia can have a negative impact on the social, psychological, and physical well-being of patients; it remains a legacy of past treatment with antipsychotics; it is an increasing concern among an ever widening population of patients receiving even newer antipsychotics; and there are now two Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for the disorder. Early career psychiatrists may have had limited instruction on tardive dyskinesia, which has not received prominent attention in curricular programs in recent years. Thus, in addition to supporting scholarly work and research experience, the 2018 Promising Scholars Award Program aims to promote knowledge and skills in managing patients with tardive dyskinesia.

Specific learning objectives are:

- Participants will learn the steps necessary to prepare a scientific manuscript for publication.

- Participants will review comments by expert referees and learn to incorporate and respond to the peer review process.

- Participants will review the evidence related to the diagnosis and treatment of tardive dyskinesia.

- Participants will be introduced to the spectrum of educational and networking opportunities at the Institute for Psychiatric Services conference.

In the past, this program was very popular and gained national recognition among psychiatric trainees. Numerous submitted papers were accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals after the competition was completed.

Instructions for manuscript preparation are:

- First author must be a student, resident, or fellow.

- Papers should address specific issues related to the theme of tardive dyskinesia and be no longer than 15 double-spaced typed pages in length (excluding references and illustrations).

- Literature reviews, case reports, or studies that are original and newly developed or recently published are acceptable.

- Reviews and feedback will be provided by a panel of academic psychiatrists.

- Papers will be judged on relevance to tardive dyskinesia, originality, scholarship, scientific rigor, valid methodology, clinical significance, and organization.

To participate, papers and curriculum vitae of the first author must be submitted by July 1, 2018, to Dianne Daugherty by email at [email protected]. Winners will be announced by Aug. 10, 2018. For additional information, write to [email protected] or visit www.mhaus.org/nmsis/about-us/what-is-nmsis.

Dr. Caroff, professor of psychiatry, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and at the University of Pennsylvania, both in Philadelphia, is director of the NMSIS. He served as consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, and receives research grant funding from Neurocrine Biosciences.

Important advances in neuroscience and clinical psychiatry have been achieved in recent years, but there are significant gaps in knowledge and much that we don’t understand about the brain and behavior. Further advances depend on cultivating and supporting a new generation of dedicated basic science and clinical investigators. While there is a compelling need to attract, recruit, and encourage talented individuals to pursue scholarly interests, competing life and career demands often prove daunting.

The theme of the competition this year concerning tardive dyskinesia is timely and consistent with the mission of NMSIS to promote knowledge on neurologic side effects of antipsychotic drugs. Tardive dyskinesia can have a negative impact on the social, psychological, and physical well-being of patients; it remains a legacy of past treatment with antipsychotics; it is an increasing concern among an ever widening population of patients receiving even newer antipsychotics; and there are now two Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for the disorder. Early career psychiatrists may have had limited instruction on tardive dyskinesia, which has not received prominent attention in curricular programs in recent years. Thus, in addition to supporting scholarly work and research experience, the 2018 Promising Scholars Award Program aims to promote knowledge and skills in managing patients with tardive dyskinesia.

Specific learning objectives are:

- Participants will learn the steps necessary to prepare a scientific manuscript for publication.

- Participants will review comments by expert referees and learn to incorporate and respond to the peer review process.

- Participants will review the evidence related to the diagnosis and treatment of tardive dyskinesia.

- Participants will be introduced to the spectrum of educational and networking opportunities at the Institute for Psychiatric Services conference.

In the past, this program was very popular and gained national recognition among psychiatric trainees. Numerous submitted papers were accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals after the competition was completed.

Instructions for manuscript preparation are:

- First author must be a student, resident, or fellow.

- Papers should address specific issues related to the theme of tardive dyskinesia and be no longer than 15 double-spaced typed pages in length (excluding references and illustrations).

- Literature reviews, case reports, or studies that are original and newly developed or recently published are acceptable.

- Reviews and feedback will be provided by a panel of academic psychiatrists.

- Papers will be judged on relevance to tardive dyskinesia, originality, scholarship, scientific rigor, valid methodology, clinical significance, and organization.

To participate, papers and curriculum vitae of the first author must be submitted by July 1, 2018, to Dianne Daugherty by email at [email protected]. Winners will be announced by Aug. 10, 2018. For additional information, write to [email protected] or visit www.mhaus.org/nmsis/about-us/what-is-nmsis.

Dr. Caroff, professor of psychiatry, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and at the University of Pennsylvania, both in Philadelphia, is director of the NMSIS. He served as consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, and receives research grant funding from Neurocrine Biosciences.

Chief complaint: Homicidal. Assessing violence risk

Mr. F, age 35, is homeless and has a history of cocaine and alcohol use disorders. He is admitted voluntarily to the psychiatric unit because he has homicidal thoughts toward Ms. S, who works in the shelter where he has been staying. Mr. F reports that he is thinking of killing Ms. S if he is discharged because she has been rude to him. He states that he has access to several firearms, but he will not disclose the location. He has been diagnosed with unspecified depressive disorder and exhibited antisocial personality disorder traits. He is being treated with sertraline. However, his mood appears to be relatively stable, except for occasional angry verbal outbursts. The outbursts have been related to intrusive peers or staff turning the television off for group meetings. Mr. F has been joking with peers, eating well, and sleeping appropriately. He reports no suicidal thoughts and has not been physically violent on the unit. However, Mr. F has had a history of violence since his teenage years. He has been incarcerated twice for assault and once for drug possession.

How would you approach assessing and managing Mr. F’s risk for violence?

We all have encountered a patient similar to Mr. F on the psychiatric unit or in the emergency department—a patient who makes violent threats and appears angry, intimidating, manipulative, and/or demanding, despite exhibiting no evidence of mania or psychosis. This patient often has a history of substance abuse and a lifelong pattern of viewing violence as an acceptable way of addressing life’s problems. Many psychiatrists suspect that more time on the inpatient unit is unlikely to reduce this patient’s risk of violence. Why? Because the violence risk does not stem from a treatable mental illness. Further, psychiatrists may be apprehensive about this patient’s potential for violence after discharge and their liability in the event of a bad outcome. No one wants their name associated with a headline that reads “Psychiatrist discharged man less than 24 hours before he killed 3 people.”

The purported relationship between mental illness and violence often is sensationalized in the media. However, research reveals that the vast majority of violence is in fact not due to symptoms of mental illness.1,2 A common clinical challenge in psychiatry involves evaluating individuals at elevated risk of violence and determining how to address their risk factors for violence. When the risk is primarily due to psychosis and can be reduced with antipsychotic medication, the job is easy. But how should we proceed when the risk stems from factors other than mental illness?

This article

Violence and mental illness: A tenuous link

Violence is a major public health concern in the United States. Although in recent years the rates of homicide and aggravated assault have decreased dramatically, there are approximately 16,000 homicides annually in the United States, and more than 1.6 million injuries from assaults treated in emergency departments each year.3 Homicide continues to be one of the leading causes of death among teenagers and young adults.4

The most effective methods of preventing widespread violence are public health approaches, such as parent- and family-focused programs, early childhood education, programs in school, and public policy changes.3 However, as psychiatrists, we are routinely asked to assess the risk of violence for an individual patient and devise strategies to mitigate violence risk.

Continue to: Although certain mental illnesses...

Although certain mental illnesses increase the relative risk of violence (compared with people without mental illness),5,6 recent studies suggest that mental illness plays only a “minor role in explaining violence in populations.”7 It is estimated that as little as 4% of the violence in the United States can be attributed to mental illness.1 According to a 1998 meta-analysis of 48 studies of criminal recidivism, the risk factors for violent recidivism were “almost identical” among offenders who had a mental disorder and those who did not.8

Approaches to assessing violence risk

Psychiatrists can assess the risk of future violence via 3 broad approaches.9,10

Unaided clinical judgment is when a mental health professional estimates violence risk based on his or her own experience and intuition, with knowledge of violence risk factors, but without the use of structured tools.

Actuarial tools are statistical models that use formulae to show relationships between data (risk factors) and outcomes (violence).10,11

Continue to: Structured professional judgment

Structured professional judgment is a hybrid of unaided clinical judgment and actuarial methods. Structured professional judgment tools help the evaluator identify empirically established risk factors. Once the information is collected, it is combined with clinical judgment in decision making.9,10 There are now more than 200 structured tools available for assessing violence risk in criminal justice and forensic mental health populations.12

Clinical judgment, although commonly used in practice, is less accurate than actuarial tools or structured professional judgment.10,11 In general, risk assessment tools offer moderate levels of accuracy in categorizing people at low risk vs high risk.5,13 The tools have better ability to accurately categorize individuals at low risk, compared with high risk, where false positives are common.12,14

Two types of risk factors

Risk factors for violence are commonly categorized as static or dynamic factors. Static factors are historical factors that cannot be changed with intervention (eg, age, sex, history of abuse). Dynamic factors can be changed with intervention (eg, substance abuse).15

Static risk factors. The best predictor of future violence is past violent behavior.5,16,17 Violence risk increases with each prior episode of violence.5 Prior arrests for any crime, especially if the individual was a juvenile at the time of arrest for his or her first violent offense, increase future violence risk.5 Other important static violence risk factors include demographic factors such as age, sex, and socioeconomic status. Swanson et al6 reviewed a large pool of data (approximately 10,000 respondents) from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. Being young, male, and of low socioeconomic status were all associated with violence in the community.6 The highest-risk age group for violence is age 15 to 24.5 Males perpetrate violence in the community at a rate 10 times that of females.18 However, among individuals with severe mental illness, men and women have similar rates of violence.19,20 Unstable employment,21 less education,22 low intelligence,16 and a history of a significant head injury5 also are risk factors for violence.5

Continue to: Being abused as a child...

Being abused as a child, witnessing violence in the home,5,16 and growing up with an unstable parental situation (eg, parental loss or separation) has been linked to violence.16,23,24 Early disruptive behavior in childhood (eg, fighting, lying and stealing, truancy, and school problems) increases violence risk.21,23

Personality factors are important static risk factors for violence. Antisocial personality disorder is the most common personality disorder linked with violence.17 Several studies consistently show psychopathy to be a strong predictor of both violence and criminal behavior.5,25 A psychopath is a person who lacks empathy and close relationships, behaves impulsively, has superficially charming qualities, and is primarily interested in self-gratification.26 Harris et al27 studied 169 released forensic patients and found that 77% of the psychopaths (according to Psychopathy Checklist-Revised [PCL-R] scores) violently recidivated. In contrast, only 21% of the non-psychopaths violently recidivated.27

Other personality factors associated with violence include a predisposition toward feelings of anger and hatred (as opposed to empathy, anxiety, or guilt, which may reduce risk), hostile attributional biases (a tendency to interpret benign behavior of others as intentionally antagonistic), violent fantasies, poor anger control, and impulsivity.5 Although personality factors tend to be longstanding and more difficult to modify, in the outpatient setting, therapeutic efforts can be made to modify hostile attribution biases, poor anger control, and impulsive behavior.

Dynamic risk factors. Substance abuse is strongly associated with violence.6,17 The prevalence of violence is 12 times greater among individuals with alcohol use disorder and 16 times greater among individuals with other substance use disorders, compared with those with no such diagnoses.5,6

Continue to: Steadman et al...

Steadman et al28 compared 1,136 adult patients with mental disorders discharged from psychiatric hospitals with 519 individuals living in the same neighborhoods as the hospitalized patients. They found that the prevalence of violence among discharged patients without substance abuse was “statistically indistinguishable” from the prevalence of violence among community members, in the same neighborhood, who did not have symptoms of substance abuse.28 Swanson et al6 found that the combination of a mental disorder plus an alcohol or substance use disorder substantially increased the risk of violence.

Other dynamic risk factors for violence include mental illness symptoms such as psychosis, especially threat/control-override delusions, where the individual believes that they are being threatened or controlled by an external force.17

Contextual factors to consider in violence risk assessments include current stressors, lack of social support, availability of weapons, access to drugs and alcohol, and the presence of similar circumstances that led to violent behavior in the past.5

How to assess the risk of targeted violence

Targeted violence is a predatory act of violence intentionally committed against a preselected person, group of people, or place.29 Due to the low base rates of these incidents, targeted violence is difficult to study.7,30 These risk assessments require a more specialized approach.

Continue to: In their 1999 article...

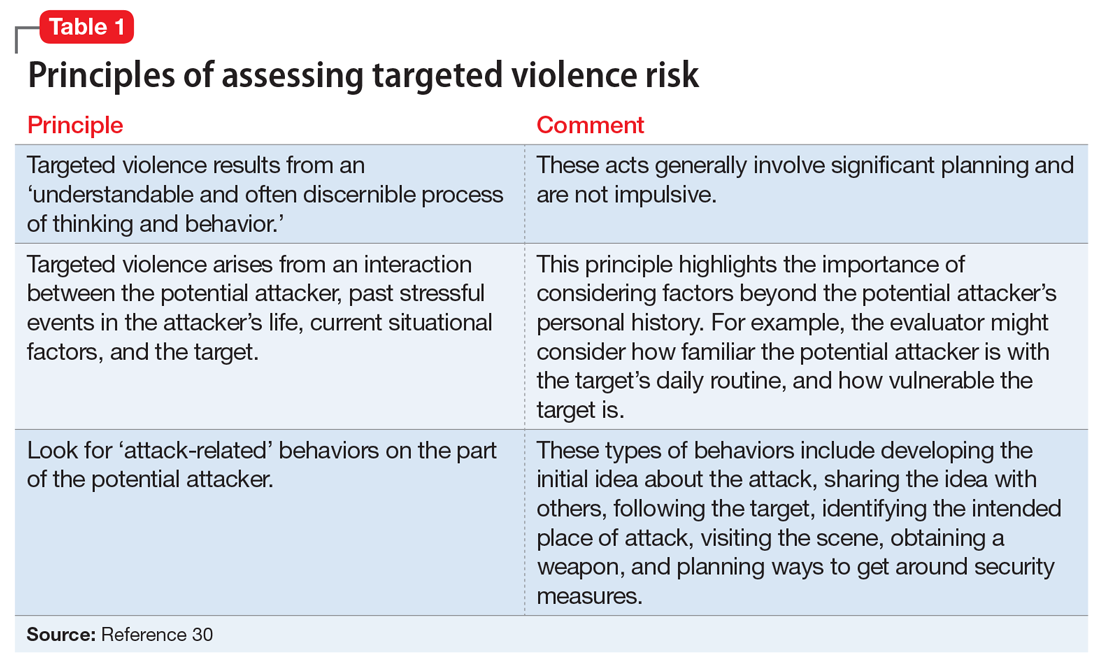

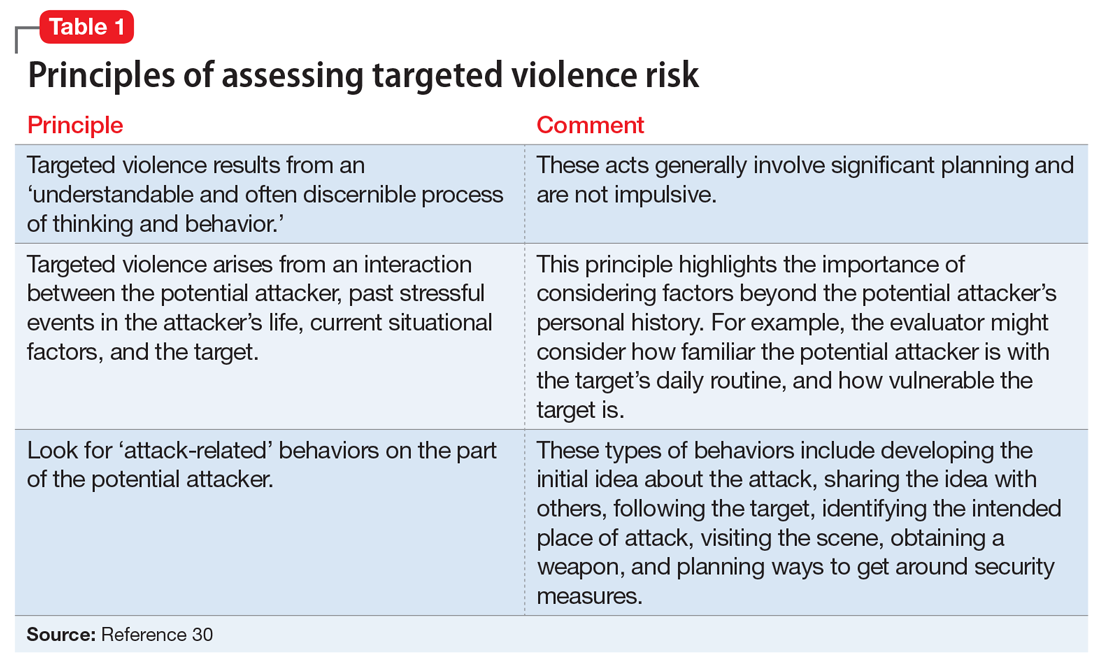

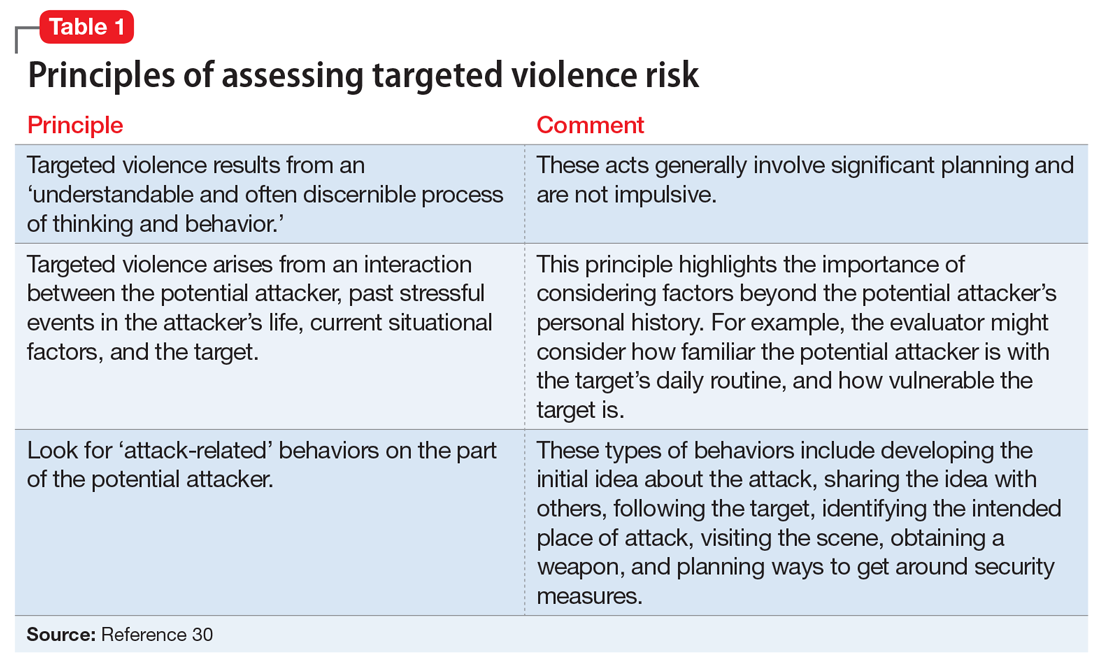

In their 1999 article, Borum et al30 discussed threat assessment strategies utilized by the U.S. Secret Service and recommended investigating “pathways of ideas and behaviors that may lead to violent action.” Borum et al30 summarized 3 fundamental principles of threat assessment (Table 130).

What to do when violence risk is not due to mental illness

Based on the information in Mr. F’s case scenario, it is likely that his homicidal ideation is not due to mental illness. Despite this, several risk factors for violence are present. Where do we go from here?

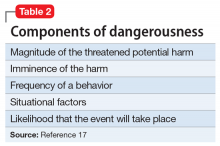

Scott and Resnick17 recommend considering the concept of dangerousness as 5 components (Table 217). When this model of dangerousness is applied to Mr. F’s case, one can see that the magnitude of the harm is great because of threatened homicide. With regard to the imminence of the harm, it would help to clarify whether Mr. F plans to kill Ms. S immediately after discharge, or sometime in the next few months. Is his threat contingent on further provocations by Ms. S? Alternatively, does he intend to kill her for past grievances, regardless of further perceived insults?

Next, the frequency of a behavior relates to how often Mr. F has been aggressive in the past. The severity of his past aggression is also important. What is the most violent act he has ever done? Situational factors in this case include Mr. F’s access to weapons, financial problems, housing problems, and access to drugs and alcohol.17 Mr. F should be asked about what situations previously provoked his violent behavior. Consider how similar the present conditions are to past conditions to which Mr. F responded violently.5 The likelihood that a homicide will occur should take into account Mr. F’s risk factors for violence, as well as the seriousness of his intent to cause harm.

Continue to: Consider using a structured tool...

Consider using a structured tool, such as the Classification of Violence Risk, to help identify Mr. F’s risk factors for violence, or some other formal method to ensure that the proper data are collected. Violence risk assessments are more accurate when structured risk assessment tools are used, compared with clinical judgment alone.

It is important to review collateral sources of information. In Mr. F’s case, useful collateral sources may include his criminal docket (usually available online), past medical records, information from the shelter where he lives, and, potentially, friends or family.

Because Mr. F is making threats of targeted violence, be sure to ask about attack-related behaviors (Table 130).

Regarding the seriousness of Mr. F’s intent to cause harm, it may be helpful to ask him the following questions:

- How likely are you to carry out this act of violence?

- Do you have a plan? Have you taken any steps toward this plan?

- Do you see other, nonviolent solutions to this problem?

- What do you hope that we can do for you to help with this problem?

Continue to: Mr. F's answers...

Mr. F’s answers may suggest the possibility of a hidden agenda. Some patients express homicidal thoughts in order to stay in the hospital. If Mr. F expresses threats that are contingent on discharge and declines to engage in problem-solving discussions, this would cast doubt on the genuineness of his threat. However, doubt about the genuineness of the threat alone is not sufficient to simply discharge Mr. F. Assessment of his intent needs to be considered with other relevant risk factors, risk reduction strategies, and any Tarasoff duties that may apply.

In addition to risk factors, consider mitigating factors. For example, does Mr. F express concern over prison time as a reason to not engage in violence? It would be more ominous if Mr. F says that he does not care if he goes to prison because life is lousy being homeless and unemployed. At this point, an estimation can be made regarding whether Mr. F is a low-, moderate-, or high-risk of violence.

The next step is to organize Mr. F’s risk factors into static (historical) and dynamic (subject to intervention) factors. This will be helpful in formulating a strategy to manage risk because continued hospitalization can only address dynamic risk factors. Often in these cases, the static risk factors are far more numerous than the dynamic risk factors.

Once the data are collected and organized, the final step is to devise a risk management strategy. Some interventions, such as substance use treatment, will be straightforward. A mood-stabilizing medication could be considered, if clinically appropriate, to help reduce aggression and irritability.31 Efforts should be made to eliminate Mr. F’s access to firearms; however, in this case, it sounds unlikely that he will cooperate with those efforts. Ultimately, you may find yourself with a list of risk factors that are unlikely to be altered with further hospitalization, particularly if Mr. F’s homicidal thoughts and intent are due to antisocial personality traits.

Continue to: In that case...

In that case, the most important step will be to carry out your duty to warn/protect others prior to Mr. F’s discharge. Most states either require or permit mental health professionals to take reasonable steps to protect victims from violence when certain conditions are present, such as an explicit threat or identifiable victim (see Related Resources).

Once dynamic risk factors have been addressed, and duty to warn/protect is carried out, if there is no further clinical indication for hospitalization, it would be appropriate to discharge Mr. F. Continued homicidal threats stemming from antisocial personality traits, in the absence of a treatable mental illness (or other modifiable risk factors for violence that can be actively addressed), is not a reason for continued hospitalization. It may be useful to obtain a second opinion from a colleague in such scenarios. A second opinion may offer additional risk management ideas. In the event of a bad outcome, this will also help to show that the decision to discharge the patient was not taken lightly.

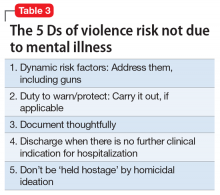

The psychiatrist should document a thoughtful risk assessment, the strategies that were implemented to reduce risk, the details of the warning, and the reasoning why continued hospitalization was not indicated (Table 3).

CASE CONTINUED

Decision to discharge

In Mr. F’s case, the treating psychiatrist determined that Mr. F’s risk of violence toward Ms. S was moderate. The psychiatrist identified several static risk factors for violence that raised Mr. F’s risk, but also noted that Mr. F’s threats were likely a manipulative effort to prolong his hospital stay. The psychiatrist carried out his duty to protect by notifying police and Ms. S of the nature of the threat prior to Mr. F’s discharge. The unit social worker helped Mr. F schedule an intake appointment for a substance use disorder treatment facility. Mr. F ultimately stated that he no longer experienced homicidal ideas once a bed was secured for him in a substance use treatment program. The psychiatrist carefully documented Mr. F’s risk assessment and the reasons why Mr. F’s risk would not be significantly altered by further inpatient hospitalization. Mr. F was discharged, and Ms. S remained unharmed.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Use a structured approach to identify risk factors for violence. Address dynamic risk factors, including access to weapons. Carry out the duty to warn/protect if applicable. Document your decisions and actions carefully, and then discharge the patient if clinically indicated. Do not be “held hostage” by a patient’s homicidal ideation.

Related Resources

- Dolan M, Doyle M. Violence risk prediction. Clinical and actuarial measures and the role of the psychopathy checklist. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:303-311.

- Douglas KS, Hart SD, Webster CD, et al. HCR-20V3: Assessing risk of violence–user guide. Burnaby, Canada: Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University; 2013.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Mental health professionals’ duty to warn. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-professionals-duty-to-warn.aspx. Published September 28, 2015.

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Skeem J, Kennealy P, Monahan J, et al. Psychosis uncommonly and inconsistently precedes violence among high-risk individuals. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4(1):40-49.

2. McGinty E, Frattaroli S, Appelbaum PS, et al. Using research evidence to reframe the policy debate around mental illness and guns: process and recommendations. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e22-e26.

3. Sumner SA, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, et al. Violence in the United States: status, challenges, and opportunities. JAMA. 2015;314(5):478-488.

4. Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(5):1-96.

5. Borum R, Swartz M, Swanson J. Assessing and managing violence risk in clinical practice. J Prac Psychiatry Behav Health. 1996;2(4):205-215.

6. Swanson JW, Holzer CE 3rd, Ganju VK, et al. Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: Evidence from the epidemiologic catchment area surveys. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41(7):761-770.

7. Swanson JW. Explaining rare acts of violence: the limits of evidence from population research. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1369-1371.

8. Bonta J, Law M, Hanson K. The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1998;123(2):123-142.

9. Monahan J. The inclusion of biological risk factors in violence risk assessments. In: Singh I, Sinnott-Armstrong W, Savulescu J, eds. Bioprediction, biomarkers, and bad behavior: scientific, legal, and ethical implications. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014:57-76.

10. Murray J, Thomson ME. Clinical judgement in violence risk assessment. Eur J Psychol. 2010;6(1):128-149.

11. Mossman D. Violence risk: is clinical judgment enough? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(6):66-72.

12. Douglas T, Pugh J, Singh I, et al. Risk assessment tools in criminal justice and forensic psychiatry: the need for better data. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;42:134-137.

13. Dolan M, Doyle M. Violence risk prediction. Clinical and actuarial measures and the role of the psychopathy checklist. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:303-311.

14. Fazel S, Singh J, Doll H, et al. Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence and antisocial behaviour in 73 samples involving 24 827 people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4692.

15. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Violence and aggression: short- term management in mental health, health, and community settings: updated edition. London: British Psychological Society; 2015. NICE Guideline, No 10.

16. Klassen D, O’Connor WA. Predicting violence in schizophrenic and non-schizophrenic patients: a prospective study. J Community Psychol. 1988;16(2):217-227.

17. Scott C, Resnick P. Clinical assessment of aggression and violence. In: Rosner R, Scott C, eds. Principles and practice of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2017:623-631.

18. Tardiff K, Sweillam A. Assault, suicide, and mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(2):164-169.

19. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Gardner W. The accuracy of predictions of violence to others. JAMA. 1993;269(8):1007-1011.

20. Newhill CE, Mulvey EP, Lidz CW. Characteristics of violence in the community by female patients seen in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Serv. 1995;46(8):785-789.

21. Mulvey E, Lidz C. Clinical considerations in the prediction of dangerousness in mental patients. Clin Psychol Rev. 1984;4(4):379-401.

22. Link BG, Andrews H, Cullen FT. The violent and illegal behavior of mental patients reconsidered. Am Sociol Rev. 1992;57(3):275-292.

23. Harris GT, Rice ME, Quinsey VL. Violent recidivism of mentally disordered offenders: the development of a statistical prediction instrument. Crim Justice and Behav. 1993;20(4):315-335.

24. Klassen D, O’Connor W. Demographic and case history variables in risk assessment. In: Monahan J, Steadman H, eds. Violence and mental disorder: developments in risk assessment. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994:229-257.

25. Hart SD, Hare RD, Forth AE. Psychopathy as a risk marker for violence: development and validation of a screening version of the revised Psychopathy Checklist. In: Monahan J, Steadman HJ, eds. Violence and mental disorder: developments in risk assessment. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994:81-98.

26. Cleckley H. The mask of sanity. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1941.

27. Harris GT, Rice ME, Cormier CA. Psychopathy and violent recidivism. Law Hum Behav. 1991;15(6):625-637.

28. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:393-401.

29. Meloy JR, White SG, Hart S. Workplace assessment of targeted violence risk: the development and reliability of the WAVR-21. J Forensic Sci. 2013;58(5):1353-1358.

30. Borum R, Fein R, Vossekuil B, et al. Threat assessment: defining an approach for evaluating risk of targeted violence. Behav Sci Law. 1999;17(3):323-337.

31. Tyrer P, Bateman AW. Drug treatment for personality disorders. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10(5):389-398.

Mr. F, age 35, is homeless and has a history of cocaine and alcohol use disorders. He is admitted voluntarily to the psychiatric unit because he has homicidal thoughts toward Ms. S, who works in the shelter where he has been staying. Mr. F reports that he is thinking of killing Ms. S if he is discharged because she has been rude to him. He states that he has access to several firearms, but he will not disclose the location. He has been diagnosed with unspecified depressive disorder and exhibited antisocial personality disorder traits. He is being treated with sertraline. However, his mood appears to be relatively stable, except for occasional angry verbal outbursts. The outbursts have been related to intrusive peers or staff turning the television off for group meetings. Mr. F has been joking with peers, eating well, and sleeping appropriately. He reports no suicidal thoughts and has not been physically violent on the unit. However, Mr. F has had a history of violence since his teenage years. He has been incarcerated twice for assault and once for drug possession.

How would you approach assessing and managing Mr. F’s risk for violence?

We all have encountered a patient similar to Mr. F on the psychiatric unit or in the emergency department—a patient who makes violent threats and appears angry, intimidating, manipulative, and/or demanding, despite exhibiting no evidence of mania or psychosis. This patient often has a history of substance abuse and a lifelong pattern of viewing violence as an acceptable way of addressing life’s problems. Many psychiatrists suspect that more time on the inpatient unit is unlikely to reduce this patient’s risk of violence. Why? Because the violence risk does not stem from a treatable mental illness. Further, psychiatrists may be apprehensive about this patient’s potential for violence after discharge and their liability in the event of a bad outcome. No one wants their name associated with a headline that reads “Psychiatrist discharged man less than 24 hours before he killed 3 people.”

The purported relationship between mental illness and violence often is sensationalized in the media. However, research reveals that the vast majority of violence is in fact not due to symptoms of mental illness.1,2 A common clinical challenge in psychiatry involves evaluating individuals at elevated risk of violence and determining how to address their risk factors for violence. When the risk is primarily due to psychosis and can be reduced with antipsychotic medication, the job is easy. But how should we proceed when the risk stems from factors other than mental illness?

This article

Violence and mental illness: A tenuous link

Violence is a major public health concern in the United States. Although in recent years the rates of homicide and aggravated assault have decreased dramatically, there are approximately 16,000 homicides annually in the United States, and more than 1.6 million injuries from assaults treated in emergency departments each year.3 Homicide continues to be one of the leading causes of death among teenagers and young adults.4

The most effective methods of preventing widespread violence are public health approaches, such as parent- and family-focused programs, early childhood education, programs in school, and public policy changes.3 However, as psychiatrists, we are routinely asked to assess the risk of violence for an individual patient and devise strategies to mitigate violence risk.

Continue to: Although certain mental illnesses...

Although certain mental illnesses increase the relative risk of violence (compared with people without mental illness),5,6 recent studies suggest that mental illness plays only a “minor role in explaining violence in populations.”7 It is estimated that as little as 4% of the violence in the United States can be attributed to mental illness.1 According to a 1998 meta-analysis of 48 studies of criminal recidivism, the risk factors for violent recidivism were “almost identical” among offenders who had a mental disorder and those who did not.8

Approaches to assessing violence risk

Psychiatrists can assess the risk of future violence via 3 broad approaches.9,10

Unaided clinical judgment is when a mental health professional estimates violence risk based on his or her own experience and intuition, with knowledge of violence risk factors, but without the use of structured tools.

Actuarial tools are statistical models that use formulae to show relationships between data (risk factors) and outcomes (violence).10,11

Continue to: Structured professional judgment

Structured professional judgment is a hybrid of unaided clinical judgment and actuarial methods. Structured professional judgment tools help the evaluator identify empirically established risk factors. Once the information is collected, it is combined with clinical judgment in decision making.9,10 There are now more than 200 structured tools available for assessing violence risk in criminal justice and forensic mental health populations.12

Clinical judgment, although commonly used in practice, is less accurate than actuarial tools or structured professional judgment.10,11 In general, risk assessment tools offer moderate levels of accuracy in categorizing people at low risk vs high risk.5,13 The tools have better ability to accurately categorize individuals at low risk, compared with high risk, where false positives are common.12,14

Two types of risk factors

Risk factors for violence are commonly categorized as static or dynamic factors. Static factors are historical factors that cannot be changed with intervention (eg, age, sex, history of abuse). Dynamic factors can be changed with intervention (eg, substance abuse).15

Static risk factors. The best predictor of future violence is past violent behavior.5,16,17 Violence risk increases with each prior episode of violence.5 Prior arrests for any crime, especially if the individual was a juvenile at the time of arrest for his or her first violent offense, increase future violence risk.5 Other important static violence risk factors include demographic factors such as age, sex, and socioeconomic status. Swanson et al6 reviewed a large pool of data (approximately 10,000 respondents) from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. Being young, male, and of low socioeconomic status were all associated with violence in the community.6 The highest-risk age group for violence is age 15 to 24.5 Males perpetrate violence in the community at a rate 10 times that of females.18 However, among individuals with severe mental illness, men and women have similar rates of violence.19,20 Unstable employment,21 less education,22 low intelligence,16 and a history of a significant head injury5 also are risk factors for violence.5

Continue to: Being abused as a child...

Being abused as a child, witnessing violence in the home,5,16 and growing up with an unstable parental situation (eg, parental loss or separation) has been linked to violence.16,23,24 Early disruptive behavior in childhood (eg, fighting, lying and stealing, truancy, and school problems) increases violence risk.21,23

Personality factors are important static risk factors for violence. Antisocial personality disorder is the most common personality disorder linked with violence.17 Several studies consistently show psychopathy to be a strong predictor of both violence and criminal behavior.5,25 A psychopath is a person who lacks empathy and close relationships, behaves impulsively, has superficially charming qualities, and is primarily interested in self-gratification.26 Harris et al27 studied 169 released forensic patients and found that 77% of the psychopaths (according to Psychopathy Checklist-Revised [PCL-R] scores) violently recidivated. In contrast, only 21% of the non-psychopaths violently recidivated.27

Other personality factors associated with violence include a predisposition toward feelings of anger and hatred (as opposed to empathy, anxiety, or guilt, which may reduce risk), hostile attributional biases (a tendency to interpret benign behavior of others as intentionally antagonistic), violent fantasies, poor anger control, and impulsivity.5 Although personality factors tend to be longstanding and more difficult to modify, in the outpatient setting, therapeutic efforts can be made to modify hostile attribution biases, poor anger control, and impulsive behavior.

Dynamic risk factors. Substance abuse is strongly associated with violence.6,17 The prevalence of violence is 12 times greater among individuals with alcohol use disorder and 16 times greater among individuals with other substance use disorders, compared with those with no such diagnoses.5,6

Continue to: Steadman et al...

Steadman et al28 compared 1,136 adult patients with mental disorders discharged from psychiatric hospitals with 519 individuals living in the same neighborhoods as the hospitalized patients. They found that the prevalence of violence among discharged patients without substance abuse was “statistically indistinguishable” from the prevalence of violence among community members, in the same neighborhood, who did not have symptoms of substance abuse.28 Swanson et al6 found that the combination of a mental disorder plus an alcohol or substance use disorder substantially increased the risk of violence.

Other dynamic risk factors for violence include mental illness symptoms such as psychosis, especially threat/control-override delusions, where the individual believes that they are being threatened or controlled by an external force.17

Contextual factors to consider in violence risk assessments include current stressors, lack of social support, availability of weapons, access to drugs and alcohol, and the presence of similar circumstances that led to violent behavior in the past.5

How to assess the risk of targeted violence

Targeted violence is a predatory act of violence intentionally committed against a preselected person, group of people, or place.29 Due to the low base rates of these incidents, targeted violence is difficult to study.7,30 These risk assessments require a more specialized approach.

Continue to: In their 1999 article...

In their 1999 article, Borum et al30 discussed threat assessment strategies utilized by the U.S. Secret Service and recommended investigating “pathways of ideas and behaviors that may lead to violent action.” Borum et al30 summarized 3 fundamental principles of threat assessment (Table 130).

What to do when violence risk is not due to mental illness

Based on the information in Mr. F’s case scenario, it is likely that his homicidal ideation is not due to mental illness. Despite this, several risk factors for violence are present. Where do we go from here?

Scott and Resnick17 recommend considering the concept of dangerousness as 5 components (Table 217). When this model of dangerousness is applied to Mr. F’s case, one can see that the magnitude of the harm is great because of threatened homicide. With regard to the imminence of the harm, it would help to clarify whether Mr. F plans to kill Ms. S immediately after discharge, or sometime in the next few months. Is his threat contingent on further provocations by Ms. S? Alternatively, does he intend to kill her for past grievances, regardless of further perceived insults?

Next, the frequency of a behavior relates to how often Mr. F has been aggressive in the past. The severity of his past aggression is also important. What is the most violent act he has ever done? Situational factors in this case include Mr. F’s access to weapons, financial problems, housing problems, and access to drugs and alcohol.17 Mr. F should be asked about what situations previously provoked his violent behavior. Consider how similar the present conditions are to past conditions to which Mr. F responded violently.5 The likelihood that a homicide will occur should take into account Mr. F’s risk factors for violence, as well as the seriousness of his intent to cause harm.

Continue to: Consider using a structured tool...

Consider using a structured tool, such as the Classification of Violence Risk, to help identify Mr. F’s risk factors for violence, or some other formal method to ensure that the proper data are collected. Violence risk assessments are more accurate when structured risk assessment tools are used, compared with clinical judgment alone.

It is important to review collateral sources of information. In Mr. F’s case, useful collateral sources may include his criminal docket (usually available online), past medical records, information from the shelter where he lives, and, potentially, friends or family.

Because Mr. F is making threats of targeted violence, be sure to ask about attack-related behaviors (Table 130).

Regarding the seriousness of Mr. F’s intent to cause harm, it may be helpful to ask him the following questions:

- How likely are you to carry out this act of violence?

- Do you have a plan? Have you taken any steps toward this plan?

- Do you see other, nonviolent solutions to this problem?

- What do you hope that we can do for you to help with this problem?

Continue to: Mr. F's answers...

Mr. F’s answers may suggest the possibility of a hidden agenda. Some patients express homicidal thoughts in order to stay in the hospital. If Mr. F expresses threats that are contingent on discharge and declines to engage in problem-solving discussions, this would cast doubt on the genuineness of his threat. However, doubt about the genuineness of the threat alone is not sufficient to simply discharge Mr. F. Assessment of his intent needs to be considered with other relevant risk factors, risk reduction strategies, and any Tarasoff duties that may apply.

In addition to risk factors, consider mitigating factors. For example, does Mr. F express concern over prison time as a reason to not engage in violence? It would be more ominous if Mr. F says that he does not care if he goes to prison because life is lousy being homeless and unemployed. At this point, an estimation can be made regarding whether Mr. F is a low-, moderate-, or high-risk of violence.

The next step is to organize Mr. F’s risk factors into static (historical) and dynamic (subject to intervention) factors. This will be helpful in formulating a strategy to manage risk because continued hospitalization can only address dynamic risk factors. Often in these cases, the static risk factors are far more numerous than the dynamic risk factors.

Once the data are collected and organized, the final step is to devise a risk management strategy. Some interventions, such as substance use treatment, will be straightforward. A mood-stabilizing medication could be considered, if clinically appropriate, to help reduce aggression and irritability.31 Efforts should be made to eliminate Mr. F’s access to firearms; however, in this case, it sounds unlikely that he will cooperate with those efforts. Ultimately, you may find yourself with a list of risk factors that are unlikely to be altered with further hospitalization, particularly if Mr. F’s homicidal thoughts and intent are due to antisocial personality traits.

Continue to: In that case...

In that case, the most important step will be to carry out your duty to warn/protect others prior to Mr. F’s discharge. Most states either require or permit mental health professionals to take reasonable steps to protect victims from violence when certain conditions are present, such as an explicit threat or identifiable victim (see Related Resources).

Once dynamic risk factors have been addressed, and duty to warn/protect is carried out, if there is no further clinical indication for hospitalization, it would be appropriate to discharge Mr. F. Continued homicidal threats stemming from antisocial personality traits, in the absence of a treatable mental illness (or other modifiable risk factors for violence that can be actively addressed), is not a reason for continued hospitalization. It may be useful to obtain a second opinion from a colleague in such scenarios. A second opinion may offer additional risk management ideas. In the event of a bad outcome, this will also help to show that the decision to discharge the patient was not taken lightly.

The psychiatrist should document a thoughtful risk assessment, the strategies that were implemented to reduce risk, the details of the warning, and the reasoning why continued hospitalization was not indicated (Table 3).

CASE CONTINUED

Decision to discharge

In Mr. F’s case, the treating psychiatrist determined that Mr. F’s risk of violence toward Ms. S was moderate. The psychiatrist identified several static risk factors for violence that raised Mr. F’s risk, but also noted that Mr. F’s threats were likely a manipulative effort to prolong his hospital stay. The psychiatrist carried out his duty to protect by notifying police and Ms. S of the nature of the threat prior to Mr. F’s discharge. The unit social worker helped Mr. F schedule an intake appointment for a substance use disorder treatment facility. Mr. F ultimately stated that he no longer experienced homicidal ideas once a bed was secured for him in a substance use treatment program. The psychiatrist carefully documented Mr. F’s risk assessment and the reasons why Mr. F’s risk would not be significantly altered by further inpatient hospitalization. Mr. F was discharged, and Ms. S remained unharmed.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Use a structured approach to identify risk factors for violence. Address dynamic risk factors, including access to weapons. Carry out the duty to warn/protect if applicable. Document your decisions and actions carefully, and then discharge the patient if clinically indicated. Do not be “held hostage” by a patient’s homicidal ideation.

Related Resources

- Dolan M, Doyle M. Violence risk prediction. Clinical and actuarial measures and the role of the psychopathy checklist. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:303-311.

- Douglas KS, Hart SD, Webster CD, et al. HCR-20V3: Assessing risk of violence–user guide. Burnaby, Canada: Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University; 2013.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Mental health professionals’ duty to warn. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-professionals-duty-to-warn.aspx. Published September 28, 2015.

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

Mr. F, age 35, is homeless and has a history of cocaine and alcohol use disorders. He is admitted voluntarily to the psychiatric unit because he has homicidal thoughts toward Ms. S, who works in the shelter where he has been staying. Mr. F reports that he is thinking of killing Ms. S if he is discharged because she has been rude to him. He states that he has access to several firearms, but he will not disclose the location. He has been diagnosed with unspecified depressive disorder and exhibited antisocial personality disorder traits. He is being treated with sertraline. However, his mood appears to be relatively stable, except for occasional angry verbal outbursts. The outbursts have been related to intrusive peers or staff turning the television off for group meetings. Mr. F has been joking with peers, eating well, and sleeping appropriately. He reports no suicidal thoughts and has not been physically violent on the unit. However, Mr. F has had a history of violence since his teenage years. He has been incarcerated twice for assault and once for drug possession.

How would you approach assessing and managing Mr. F’s risk for violence?

We all have encountered a patient similar to Mr. F on the psychiatric unit or in the emergency department—a patient who makes violent threats and appears angry, intimidating, manipulative, and/or demanding, despite exhibiting no evidence of mania or psychosis. This patient often has a history of substance abuse and a lifelong pattern of viewing violence as an acceptable way of addressing life’s problems. Many psychiatrists suspect that more time on the inpatient unit is unlikely to reduce this patient’s risk of violence. Why? Because the violence risk does not stem from a treatable mental illness. Further, psychiatrists may be apprehensive about this patient’s potential for violence after discharge and their liability in the event of a bad outcome. No one wants their name associated with a headline that reads “Psychiatrist discharged man less than 24 hours before he killed 3 people.”

The purported relationship between mental illness and violence often is sensationalized in the media. However, research reveals that the vast majority of violence is in fact not due to symptoms of mental illness.1,2 A common clinical challenge in psychiatry involves evaluating individuals at elevated risk of violence and determining how to address their risk factors for violence. When the risk is primarily due to psychosis and can be reduced with antipsychotic medication, the job is easy. But how should we proceed when the risk stems from factors other than mental illness?

This article

Violence and mental illness: A tenuous link

Violence is a major public health concern in the United States. Although in recent years the rates of homicide and aggravated assault have decreased dramatically, there are approximately 16,000 homicides annually in the United States, and more than 1.6 million injuries from assaults treated in emergency departments each year.3 Homicide continues to be one of the leading causes of death among teenagers and young adults.4

The most effective methods of preventing widespread violence are public health approaches, such as parent- and family-focused programs, early childhood education, programs in school, and public policy changes.3 However, as psychiatrists, we are routinely asked to assess the risk of violence for an individual patient and devise strategies to mitigate violence risk.

Continue to: Although certain mental illnesses...

Although certain mental illnesses increase the relative risk of violence (compared with people without mental illness),5,6 recent studies suggest that mental illness plays only a “minor role in explaining violence in populations.”7 It is estimated that as little as 4% of the violence in the United States can be attributed to mental illness.1 According to a 1998 meta-analysis of 48 studies of criminal recidivism, the risk factors for violent recidivism were “almost identical” among offenders who had a mental disorder and those who did not.8

Approaches to assessing violence risk

Psychiatrists can assess the risk of future violence via 3 broad approaches.9,10

Unaided clinical judgment is when a mental health professional estimates violence risk based on his or her own experience and intuition, with knowledge of violence risk factors, but without the use of structured tools.

Actuarial tools are statistical models that use formulae to show relationships between data (risk factors) and outcomes (violence).10,11

Continue to: Structured professional judgment

Structured professional judgment is a hybrid of unaided clinical judgment and actuarial methods. Structured professional judgment tools help the evaluator identify empirically established risk factors. Once the information is collected, it is combined with clinical judgment in decision making.9,10 There are now more than 200 structured tools available for assessing violence risk in criminal justice and forensic mental health populations.12

Clinical judgment, although commonly used in practice, is less accurate than actuarial tools or structured professional judgment.10,11 In general, risk assessment tools offer moderate levels of accuracy in categorizing people at low risk vs high risk.5,13 The tools have better ability to accurately categorize individuals at low risk, compared with high risk, where false positives are common.12,14

Two types of risk factors

Risk factors for violence are commonly categorized as static or dynamic factors. Static factors are historical factors that cannot be changed with intervention (eg, age, sex, history of abuse). Dynamic factors can be changed with intervention (eg, substance abuse).15

Static risk factors. The best predictor of future violence is past violent behavior.5,16,17 Violence risk increases with each prior episode of violence.5 Prior arrests for any crime, especially if the individual was a juvenile at the time of arrest for his or her first violent offense, increase future violence risk.5 Other important static violence risk factors include demographic factors such as age, sex, and socioeconomic status. Swanson et al6 reviewed a large pool of data (approximately 10,000 respondents) from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. Being young, male, and of low socioeconomic status were all associated with violence in the community.6 The highest-risk age group for violence is age 15 to 24.5 Males perpetrate violence in the community at a rate 10 times that of females.18 However, among individuals with severe mental illness, men and women have similar rates of violence.19,20 Unstable employment,21 less education,22 low intelligence,16 and a history of a significant head injury5 also are risk factors for violence.5

Continue to: Being abused as a child...

Being abused as a child, witnessing violence in the home,5,16 and growing up with an unstable parental situation (eg, parental loss or separation) has been linked to violence.16,23,24 Early disruptive behavior in childhood (eg, fighting, lying and stealing, truancy, and school problems) increases violence risk.21,23

Personality factors are important static risk factors for violence. Antisocial personality disorder is the most common personality disorder linked with violence.17 Several studies consistently show psychopathy to be a strong predictor of both violence and criminal behavior.5,25 A psychopath is a person who lacks empathy and close relationships, behaves impulsively, has superficially charming qualities, and is primarily interested in self-gratification.26 Harris et al27 studied 169 released forensic patients and found that 77% of the psychopaths (according to Psychopathy Checklist-Revised [PCL-R] scores) violently recidivated. In contrast, only 21% of the non-psychopaths violently recidivated.27

Other personality factors associated with violence include a predisposition toward feelings of anger and hatred (as opposed to empathy, anxiety, or guilt, which may reduce risk), hostile attributional biases (a tendency to interpret benign behavior of others as intentionally antagonistic), violent fantasies, poor anger control, and impulsivity.5 Although personality factors tend to be longstanding and more difficult to modify, in the outpatient setting, therapeutic efforts can be made to modify hostile attribution biases, poor anger control, and impulsive behavior.

Dynamic risk factors. Substance abuse is strongly associated with violence.6,17 The prevalence of violence is 12 times greater among individuals with alcohol use disorder and 16 times greater among individuals with other substance use disorders, compared with those with no such diagnoses.5,6

Continue to: Steadman et al...

Steadman et al28 compared 1,136 adult patients with mental disorders discharged from psychiatric hospitals with 519 individuals living in the same neighborhoods as the hospitalized patients. They found that the prevalence of violence among discharged patients without substance abuse was “statistically indistinguishable” from the prevalence of violence among community members, in the same neighborhood, who did not have symptoms of substance abuse.28 Swanson et al6 found that the combination of a mental disorder plus an alcohol or substance use disorder substantially increased the risk of violence.

Other dynamic risk factors for violence include mental illness symptoms such as psychosis, especially threat/control-override delusions, where the individual believes that they are being threatened or controlled by an external force.17

Contextual factors to consider in violence risk assessments include current stressors, lack of social support, availability of weapons, access to drugs and alcohol, and the presence of similar circumstances that led to violent behavior in the past.5

How to assess the risk of targeted violence

Targeted violence is a predatory act of violence intentionally committed against a preselected person, group of people, or place.29 Due to the low base rates of these incidents, targeted violence is difficult to study.7,30 These risk assessments require a more specialized approach.

Continue to: In their 1999 article...

In their 1999 article, Borum et al30 discussed threat assessment strategies utilized by the U.S. Secret Service and recommended investigating “pathways of ideas and behaviors that may lead to violent action.” Borum et al30 summarized 3 fundamental principles of threat assessment (Table 130).

What to do when violence risk is not due to mental illness

Based on the information in Mr. F’s case scenario, it is likely that his homicidal ideation is not due to mental illness. Despite this, several risk factors for violence are present. Where do we go from here?

Scott and Resnick17 recommend considering the concept of dangerousness as 5 components (Table 217). When this model of dangerousness is applied to Mr. F’s case, one can see that the magnitude of the harm is great because of threatened homicide. With regard to the imminence of the harm, it would help to clarify whether Mr. F plans to kill Ms. S immediately after discharge, or sometime in the next few months. Is his threat contingent on further provocations by Ms. S? Alternatively, does he intend to kill her for past grievances, regardless of further perceived insults?

Next, the frequency of a behavior relates to how often Mr. F has been aggressive in the past. The severity of his past aggression is also important. What is the most violent act he has ever done? Situational factors in this case include Mr. F’s access to weapons, financial problems, housing problems, and access to drugs and alcohol.17 Mr. F should be asked about what situations previously provoked his violent behavior. Consider how similar the present conditions are to past conditions to which Mr. F responded violently.5 The likelihood that a homicide will occur should take into account Mr. F’s risk factors for violence, as well as the seriousness of his intent to cause harm.

Continue to: Consider using a structured tool...

Consider using a structured tool, such as the Classification of Violence Risk, to help identify Mr. F’s risk factors for violence, or some other formal method to ensure that the proper data are collected. Violence risk assessments are more accurate when structured risk assessment tools are used, compared with clinical judgment alone.

It is important to review collateral sources of information. In Mr. F’s case, useful collateral sources may include his criminal docket (usually available online), past medical records, information from the shelter where he lives, and, potentially, friends or family.

Because Mr. F is making threats of targeted violence, be sure to ask about attack-related behaviors (Table 130).

Regarding the seriousness of Mr. F’s intent to cause harm, it may be helpful to ask him the following questions:

- How likely are you to carry out this act of violence?

- Do you have a plan? Have you taken any steps toward this plan?

- Do you see other, nonviolent solutions to this problem?

- What do you hope that we can do for you to help with this problem?

Continue to: Mr. F's answers...

Mr. F’s answers may suggest the possibility of a hidden agenda. Some patients express homicidal thoughts in order to stay in the hospital. If Mr. F expresses threats that are contingent on discharge and declines to engage in problem-solving discussions, this would cast doubt on the genuineness of his threat. However, doubt about the genuineness of the threat alone is not sufficient to simply discharge Mr. F. Assessment of his intent needs to be considered with other relevant risk factors, risk reduction strategies, and any Tarasoff duties that may apply.

In addition to risk factors, consider mitigating factors. For example, does Mr. F express concern over prison time as a reason to not engage in violence? It would be more ominous if Mr. F says that he does not care if he goes to prison because life is lousy being homeless and unemployed. At this point, an estimation can be made regarding whether Mr. F is a low-, moderate-, or high-risk of violence.

The next step is to organize Mr. F’s risk factors into static (historical) and dynamic (subject to intervention) factors. This will be helpful in formulating a strategy to manage risk because continued hospitalization can only address dynamic risk factors. Often in these cases, the static risk factors are far more numerous than the dynamic risk factors.