User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

The neurobiology of Jeopardy! champions

As a regular viewer of Jeopardy! I find it both interesting and educational. But the psychiatric neuroscientist in me marvels at the splendid cerebral attributes embedded in the brains of Jeopardy! champions.

Back in my college days, I participated in what were then called “general knowledge contests” and won a couple of trophies, the most gratifying of which was when our team of medical students beat the faculty team! Later, when my wife and I had children, Trivial Pursuit was a game frequently played in our household. So it is no wonder I have often thought of the remarkable, sometimes stunning intellectual performances of Jeopardy! champions.

What does it take to excel at Jeopardy!?

Watching contestants successfully answer a bewildering array of questions across an extensive spectrum of topics is simply dazzling and prompts me to ask: Which neurologic structures play a central role in the brains of Jeopardy! champions? So I channeled my inner neurobiologist and came up with the following prerequisites to excel at Jeopardy!:

- A hippocampus on steroids! Memory is obviously a core ingredient for responding to Jeopardy! questions. Unlike ordinary mortals, Jeopardy! champions appear to retain and instantaneously, accurately recall everything they have read, saw, or heard.

- A sublime network of dendritic spines, where learning is immediately transduced to biological memories, thanks to the wonders of experiential neuroplasticity in homo sapiens.

- A superlative frontal lobe, which provides the champion with an ultra-rapid abstraction ability in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, along with razor-sharp concentration and attention.

- An extremely well-myelinated network of the 137,000 miles of white matter fibers in the human brain. This is what leads to fabulous processing speed. Rapid neurotransmission is impossible without very well-myelinated axons and dendrites. It is not enough for a Jeopardy! champion to know the answer and retrieve it from the hippocampus—they also must transmit the answer at lightning speed to the speech area, and then activate the motor area to enunciate the answer. Processing speed is the foundation of overall cognitive functioning.

- A first-rate Broca’s area, referred to as “the brain’s scriptwriter,” which shapes human speech. It receives the flow of sensory information from the temporal cortex, devises a plan for speaking, and passes that plan seamlessly to the motor cortex, which controls the movements of the mouth.

- Blistering speed reflexes to click the handheld response buzzer within a fraction of a millisecond after the host finishes reading the clue (not before, or a penalty is incurred). Jeopardy! champions always click the buzzer faster than their competitors, who may know the answer but have ordinary motor reflexes (also related to the degree of myelination and a motoric component of processing speed).

- A thick corpus callosum, the largest interhemispheric commissure, a bundle of 200 million white matter fibers connecting analogous regions in the right and left hemispheres, is vital for the rapid bidirectional transfer of bits of information from the intuitive/nonverbal right hemisphere to the mathematical/verbal left hemisphere, when the answer requires right hemispheric input.

- A bright occipital cortex and exceptional optic nerve and retina, so that champions can recognize faces or locations and read the questions before the host finishes reading them, which gives them an awesome edge on other contestants.

Obviously, the brains of Jeopardy! champions are a breed of their own, with exceptional performances by multiple regions converging to produce a winning performance. But during their childhood and youthful years, such brains also generate motivation, curiosity, and interest in a wide range of topics, from cultures, regions, music genres, and word games to history, geography, sports, science, medicine, astronomy, and Greek mythology.

Jeopardy! champions may appear to have regular jobs and ordinary lives, but they have resplendent “renaissance” brains. I wonder how they spent their childhood, who mentored them, what type of family lives they had, and what they dream of accomplishing other than winning on Jeopardy!. Will their awe-inspiring performance in Jeopardy! translate to overall success in life? That’s a story that remains to be told.

As a regular viewer of Jeopardy! I find it both interesting and educational. But the psychiatric neuroscientist in me marvels at the splendid cerebral attributes embedded in the brains of Jeopardy! champions.

Back in my college days, I participated in what were then called “general knowledge contests” and won a couple of trophies, the most gratifying of which was when our team of medical students beat the faculty team! Later, when my wife and I had children, Trivial Pursuit was a game frequently played in our household. So it is no wonder I have often thought of the remarkable, sometimes stunning intellectual performances of Jeopardy! champions.

What does it take to excel at Jeopardy!?

Watching contestants successfully answer a bewildering array of questions across an extensive spectrum of topics is simply dazzling and prompts me to ask: Which neurologic structures play a central role in the brains of Jeopardy! champions? So I channeled my inner neurobiologist and came up with the following prerequisites to excel at Jeopardy!:

- A hippocampus on steroids! Memory is obviously a core ingredient for responding to Jeopardy! questions. Unlike ordinary mortals, Jeopardy! champions appear to retain and instantaneously, accurately recall everything they have read, saw, or heard.

- A sublime network of dendritic spines, where learning is immediately transduced to biological memories, thanks to the wonders of experiential neuroplasticity in homo sapiens.

- A superlative frontal lobe, which provides the champion with an ultra-rapid abstraction ability in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, along with razor-sharp concentration and attention.

- An extremely well-myelinated network of the 137,000 miles of white matter fibers in the human brain. This is what leads to fabulous processing speed. Rapid neurotransmission is impossible without very well-myelinated axons and dendrites. It is not enough for a Jeopardy! champion to know the answer and retrieve it from the hippocampus—they also must transmit the answer at lightning speed to the speech area, and then activate the motor area to enunciate the answer. Processing speed is the foundation of overall cognitive functioning.

- A first-rate Broca’s area, referred to as “the brain’s scriptwriter,” which shapes human speech. It receives the flow of sensory information from the temporal cortex, devises a plan for speaking, and passes that plan seamlessly to the motor cortex, which controls the movements of the mouth.

- Blistering speed reflexes to click the handheld response buzzer within a fraction of a millisecond after the host finishes reading the clue (not before, or a penalty is incurred). Jeopardy! champions always click the buzzer faster than their competitors, who may know the answer but have ordinary motor reflexes (also related to the degree of myelination and a motoric component of processing speed).

- A thick corpus callosum, the largest interhemispheric commissure, a bundle of 200 million white matter fibers connecting analogous regions in the right and left hemispheres, is vital for the rapid bidirectional transfer of bits of information from the intuitive/nonverbal right hemisphere to the mathematical/verbal left hemisphere, when the answer requires right hemispheric input.

- A bright occipital cortex and exceptional optic nerve and retina, so that champions can recognize faces or locations and read the questions before the host finishes reading them, which gives them an awesome edge on other contestants.

Obviously, the brains of Jeopardy! champions are a breed of their own, with exceptional performances by multiple regions converging to produce a winning performance. But during their childhood and youthful years, such brains also generate motivation, curiosity, and interest in a wide range of topics, from cultures, regions, music genres, and word games to history, geography, sports, science, medicine, astronomy, and Greek mythology.

Jeopardy! champions may appear to have regular jobs and ordinary lives, but they have resplendent “renaissance” brains. I wonder how they spent their childhood, who mentored them, what type of family lives they had, and what they dream of accomplishing other than winning on Jeopardy!. Will their awe-inspiring performance in Jeopardy! translate to overall success in life? That’s a story that remains to be told.

As a regular viewer of Jeopardy! I find it both interesting and educational. But the psychiatric neuroscientist in me marvels at the splendid cerebral attributes embedded in the brains of Jeopardy! champions.

Back in my college days, I participated in what were then called “general knowledge contests” and won a couple of trophies, the most gratifying of which was when our team of medical students beat the faculty team! Later, when my wife and I had children, Trivial Pursuit was a game frequently played in our household. So it is no wonder I have often thought of the remarkable, sometimes stunning intellectual performances of Jeopardy! champions.

What does it take to excel at Jeopardy!?

Watching contestants successfully answer a bewildering array of questions across an extensive spectrum of topics is simply dazzling and prompts me to ask: Which neurologic structures play a central role in the brains of Jeopardy! champions? So I channeled my inner neurobiologist and came up with the following prerequisites to excel at Jeopardy!:

- A hippocampus on steroids! Memory is obviously a core ingredient for responding to Jeopardy! questions. Unlike ordinary mortals, Jeopardy! champions appear to retain and instantaneously, accurately recall everything they have read, saw, or heard.

- A sublime network of dendritic spines, where learning is immediately transduced to biological memories, thanks to the wonders of experiential neuroplasticity in homo sapiens.

- A superlative frontal lobe, which provides the champion with an ultra-rapid abstraction ability in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, along with razor-sharp concentration and attention.

- An extremely well-myelinated network of the 137,000 miles of white matter fibers in the human brain. This is what leads to fabulous processing speed. Rapid neurotransmission is impossible without very well-myelinated axons and dendrites. It is not enough for a Jeopardy! champion to know the answer and retrieve it from the hippocampus—they also must transmit the answer at lightning speed to the speech area, and then activate the motor area to enunciate the answer. Processing speed is the foundation of overall cognitive functioning.

- A first-rate Broca’s area, referred to as “the brain’s scriptwriter,” which shapes human speech. It receives the flow of sensory information from the temporal cortex, devises a plan for speaking, and passes that plan seamlessly to the motor cortex, which controls the movements of the mouth.

- Blistering speed reflexes to click the handheld response buzzer within a fraction of a millisecond after the host finishes reading the clue (not before, or a penalty is incurred). Jeopardy! champions always click the buzzer faster than their competitors, who may know the answer but have ordinary motor reflexes (also related to the degree of myelination and a motoric component of processing speed).

- A thick corpus callosum, the largest interhemispheric commissure, a bundle of 200 million white matter fibers connecting analogous regions in the right and left hemispheres, is vital for the rapid bidirectional transfer of bits of information from the intuitive/nonverbal right hemisphere to the mathematical/verbal left hemisphere, when the answer requires right hemispheric input.

- A bright occipital cortex and exceptional optic nerve and retina, so that champions can recognize faces or locations and read the questions before the host finishes reading them, which gives them an awesome edge on other contestants.

Obviously, the brains of Jeopardy! champions are a breed of their own, with exceptional performances by multiple regions converging to produce a winning performance. But during their childhood and youthful years, such brains also generate motivation, curiosity, and interest in a wide range of topics, from cultures, regions, music genres, and word games to history, geography, sports, science, medicine, astronomy, and Greek mythology.

Jeopardy! champions may appear to have regular jobs and ordinary lives, but they have resplendent “renaissance” brains. I wonder how they spent their childhood, who mentored them, what type of family lives they had, and what they dream of accomplishing other than winning on Jeopardy!. Will their awe-inspiring performance in Jeopardy! translate to overall success in life? That’s a story that remains to be told.

The case for pursuing a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Four years ago, pursuing a consultation-liaison psychiatry (CL) fellowship was the last thing on my mind. I had recently started my third year as a CL attending at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and was becoming more of an integral part of its academic department. I felt that I had found my calling. I wanted to be an educator, with the hope of becoming a psychiatry residency program director. This idea was validated when I was awarded the Golden Apple for Excellence in Clinical Teaching, voted by the psychiatry residents, as well as a medical student teaching award. Both awards related to my CL duties.

And then, life happened. My wife and I decided to move east to be closer to family. I planned to continue my path at an academic institution while teaching CL psychiatry. Yet, each institution I interviewed with explained that while my recent experience was “great,” I would need to be formally CL fellowship–trained if I wanted to work in the CL division. On the one hand, this was frustrating to hear; however, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established rules regarding how many faculty at institutions that offer CL fellowships need to be CL fellowship–trained. After much consideration, specifically about my personal career aspirations and family situation, I decided to go “backwards” and pursue a CL fellowship.

Parts of the fellowship year were easier than the previous 3 years. For example, my caseload was much lighter, as were my supervision duties. However, almost immediately, there was an ego-check—for instance, recognizing that I would not always agree with my attendings, and other services would no longer view me as “the attending.” Despite that, as I now discuss with my trainees, I am never above further learning and gaining more clinical experience. Early in that first year of fellowship, I was involved in a complicated case of a patient with autoimmune encephalitis with severe catatonia who warranted electroconvulsive therapy. I gained experience using phenobarbital for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal, something I did not use during my residency or first 3 years as an attending.

Furthermore, my academic project that year was to revamp the fellowship. This included resetting the fellowship’s mission statement, as well as updating our rotations and curriculum, to better align with fellowship best practices around the country. It afforded me time to develop my own “educational” pathway and think of ways in which CL is expanding its footprint. Consistent with this, Park et al1 demonstrated the most common “major reason” for pursuing a CL fellowship was to obtain clinical training; the “moderate reason” of teaching opportunities cannot be overlooked.

The value of a CL fellowship

CL is about the intersection of behavioral health with medicine. As such, I believe CL fellowships will be part of the solution for addressing the current health care cost crisis2 as well as improving access to mental health treatment.3 We already see this solution in collaborative care programs. According to the National Resident Matching Program, in 2021 there were 60 CL fellowship programs and 124 CL fellowship positions offered nationwide, with a total of 89 fellowship applicants and 84 spots filled.4 Looking back 5 years, there were only 52 CL fellowship programs nationwide.4 While there are currently fewer applicants than spots, the fact that the number of available programs is increasing demonstrates the value that each institution puts into CL as well as the importance of our presence in the health care system. The CL fellowship year can create a special opportunity for the fellow that dovetails with their passions. If an applicant wants a program that has expert subspecialty services and focuses on teaching and social determinates of health, they can assuredly find that program.

The decision to pursue fellowship is a personal choice. I believe that CL as a subspecialty will demonstrate its importance to both the psychiatric and medical fields. CL fellowships can continue to innovate and move forward by recognizing the changing landscape of CL psychiatry and matching the fellowship experience to those needs. This will only make the draw for fellowship more powerful. Four years ago, I did not want to pursue fellowship—today I am truly grateful I did.

1. Park EM, Sockalingam S, Ravindranath D, et al; Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine’s Early Career Psychiatrist Special Interest Group. Psychosomatic medicine training as a bridge to practice: training and professional practice patterns of early career psychosomatic medicine specialists. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):52-58. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2014.05.003

2. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en

3. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2016.

4. National Resident Matching Program. Results and data: specialties matching service 2021 appointment year. National Resident Matching Program; 2021.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Four years ago, pursuing a consultation-liaison psychiatry (CL) fellowship was the last thing on my mind. I had recently started my third year as a CL attending at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and was becoming more of an integral part of its academic department. I felt that I had found my calling. I wanted to be an educator, with the hope of becoming a psychiatry residency program director. This idea was validated when I was awarded the Golden Apple for Excellence in Clinical Teaching, voted by the psychiatry residents, as well as a medical student teaching award. Both awards related to my CL duties.

And then, life happened. My wife and I decided to move east to be closer to family. I planned to continue my path at an academic institution while teaching CL psychiatry. Yet, each institution I interviewed with explained that while my recent experience was “great,” I would need to be formally CL fellowship–trained if I wanted to work in the CL division. On the one hand, this was frustrating to hear; however, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established rules regarding how many faculty at institutions that offer CL fellowships need to be CL fellowship–trained. After much consideration, specifically about my personal career aspirations and family situation, I decided to go “backwards” and pursue a CL fellowship.

Parts of the fellowship year were easier than the previous 3 years. For example, my caseload was much lighter, as were my supervision duties. However, almost immediately, there was an ego-check—for instance, recognizing that I would not always agree with my attendings, and other services would no longer view me as “the attending.” Despite that, as I now discuss with my trainees, I am never above further learning and gaining more clinical experience. Early in that first year of fellowship, I was involved in a complicated case of a patient with autoimmune encephalitis with severe catatonia who warranted electroconvulsive therapy. I gained experience using phenobarbital for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal, something I did not use during my residency or first 3 years as an attending.

Furthermore, my academic project that year was to revamp the fellowship. This included resetting the fellowship’s mission statement, as well as updating our rotations and curriculum, to better align with fellowship best practices around the country. It afforded me time to develop my own “educational” pathway and think of ways in which CL is expanding its footprint. Consistent with this, Park et al1 demonstrated the most common “major reason” for pursuing a CL fellowship was to obtain clinical training; the “moderate reason” of teaching opportunities cannot be overlooked.

The value of a CL fellowship

CL is about the intersection of behavioral health with medicine. As such, I believe CL fellowships will be part of the solution for addressing the current health care cost crisis2 as well as improving access to mental health treatment.3 We already see this solution in collaborative care programs. According to the National Resident Matching Program, in 2021 there were 60 CL fellowship programs and 124 CL fellowship positions offered nationwide, with a total of 89 fellowship applicants and 84 spots filled.4 Looking back 5 years, there were only 52 CL fellowship programs nationwide.4 While there are currently fewer applicants than spots, the fact that the number of available programs is increasing demonstrates the value that each institution puts into CL as well as the importance of our presence in the health care system. The CL fellowship year can create a special opportunity for the fellow that dovetails with their passions. If an applicant wants a program that has expert subspecialty services and focuses on teaching and social determinates of health, they can assuredly find that program.

The decision to pursue fellowship is a personal choice. I believe that CL as a subspecialty will demonstrate its importance to both the psychiatric and medical fields. CL fellowships can continue to innovate and move forward by recognizing the changing landscape of CL psychiatry and matching the fellowship experience to those needs. This will only make the draw for fellowship more powerful. Four years ago, I did not want to pursue fellowship—today I am truly grateful I did.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Four years ago, pursuing a consultation-liaison psychiatry (CL) fellowship was the last thing on my mind. I had recently started my third year as a CL attending at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and was becoming more of an integral part of its academic department. I felt that I had found my calling. I wanted to be an educator, with the hope of becoming a psychiatry residency program director. This idea was validated when I was awarded the Golden Apple for Excellence in Clinical Teaching, voted by the psychiatry residents, as well as a medical student teaching award. Both awards related to my CL duties.

And then, life happened. My wife and I decided to move east to be closer to family. I planned to continue my path at an academic institution while teaching CL psychiatry. Yet, each institution I interviewed with explained that while my recent experience was “great,” I would need to be formally CL fellowship–trained if I wanted to work in the CL division. On the one hand, this was frustrating to hear; however, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established rules regarding how many faculty at institutions that offer CL fellowships need to be CL fellowship–trained. After much consideration, specifically about my personal career aspirations and family situation, I decided to go “backwards” and pursue a CL fellowship.

Parts of the fellowship year were easier than the previous 3 years. For example, my caseload was much lighter, as were my supervision duties. However, almost immediately, there was an ego-check—for instance, recognizing that I would not always agree with my attendings, and other services would no longer view me as “the attending.” Despite that, as I now discuss with my trainees, I am never above further learning and gaining more clinical experience. Early in that first year of fellowship, I was involved in a complicated case of a patient with autoimmune encephalitis with severe catatonia who warranted electroconvulsive therapy. I gained experience using phenobarbital for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal, something I did not use during my residency or first 3 years as an attending.

Furthermore, my academic project that year was to revamp the fellowship. This included resetting the fellowship’s mission statement, as well as updating our rotations and curriculum, to better align with fellowship best practices around the country. It afforded me time to develop my own “educational” pathway and think of ways in which CL is expanding its footprint. Consistent with this, Park et al1 demonstrated the most common “major reason” for pursuing a CL fellowship was to obtain clinical training; the “moderate reason” of teaching opportunities cannot be overlooked.

The value of a CL fellowship

CL is about the intersection of behavioral health with medicine. As such, I believe CL fellowships will be part of the solution for addressing the current health care cost crisis2 as well as improving access to mental health treatment.3 We already see this solution in collaborative care programs. According to the National Resident Matching Program, in 2021 there were 60 CL fellowship programs and 124 CL fellowship positions offered nationwide, with a total of 89 fellowship applicants and 84 spots filled.4 Looking back 5 years, there were only 52 CL fellowship programs nationwide.4 While there are currently fewer applicants than spots, the fact that the number of available programs is increasing demonstrates the value that each institution puts into CL as well as the importance of our presence in the health care system. The CL fellowship year can create a special opportunity for the fellow that dovetails with their passions. If an applicant wants a program that has expert subspecialty services and focuses on teaching and social determinates of health, they can assuredly find that program.

The decision to pursue fellowship is a personal choice. I believe that CL as a subspecialty will demonstrate its importance to both the psychiatric and medical fields. CL fellowships can continue to innovate and move forward by recognizing the changing landscape of CL psychiatry and matching the fellowship experience to those needs. This will only make the draw for fellowship more powerful. Four years ago, I did not want to pursue fellowship—today I am truly grateful I did.

1. Park EM, Sockalingam S, Ravindranath D, et al; Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine’s Early Career Psychiatrist Special Interest Group. Psychosomatic medicine training as a bridge to practice: training and professional practice patterns of early career psychosomatic medicine specialists. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):52-58. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2014.05.003

2. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en

3. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2016.

4. National Resident Matching Program. Results and data: specialties matching service 2021 appointment year. National Resident Matching Program; 2021.

1. Park EM, Sockalingam S, Ravindranath D, et al; Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine’s Early Career Psychiatrist Special Interest Group. Psychosomatic medicine training as a bridge to practice: training and professional practice patterns of early career psychosomatic medicine specialists. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):52-58. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2014.05.003

2. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en

3. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2016.

4. National Resident Matching Program. Results and data: specialties matching service 2021 appointment year. National Resident Matching Program; 2021.

Deprescribing in older adults: An overview

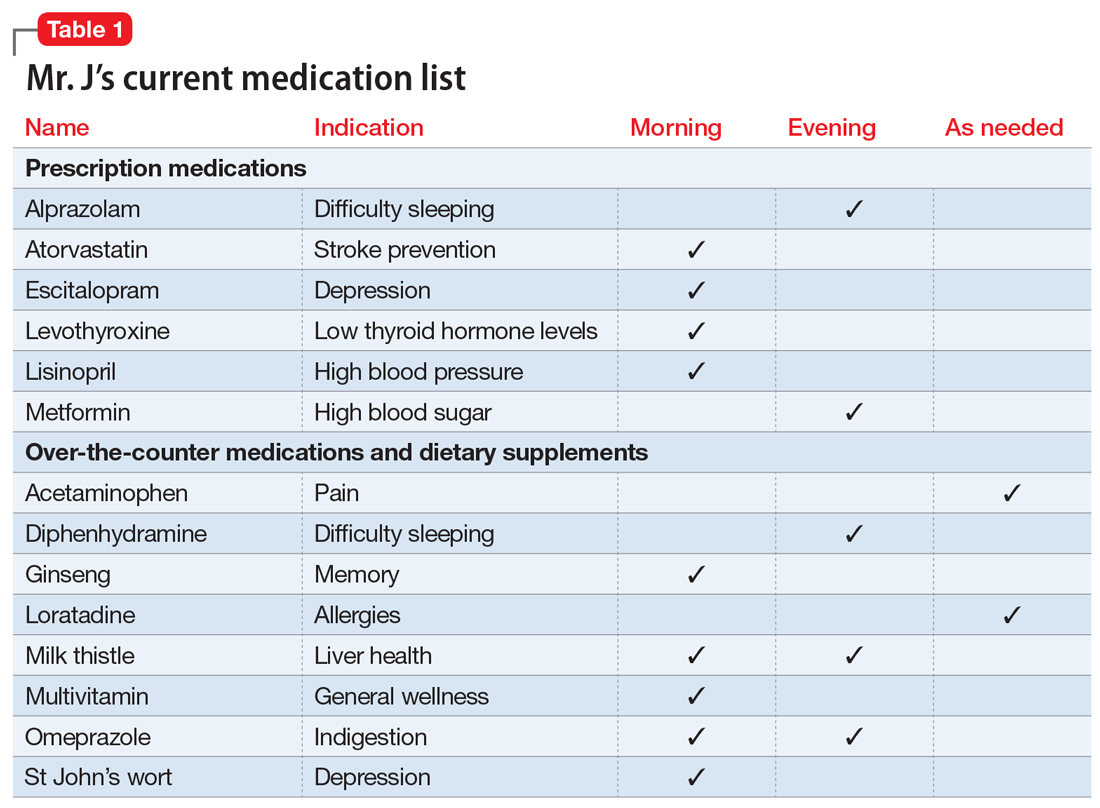

Mr. J, age 73, has a 25-year history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. His medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, insomnia, and allergic rhinitis. His last laboratory test results indicate his hemoglobin A1c, thyroid-stimulating hormone, low-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure measurements are at goal. He believes his conditions are well controlled but cites concerns about taking multiple medications each day and being able to afford his medications.

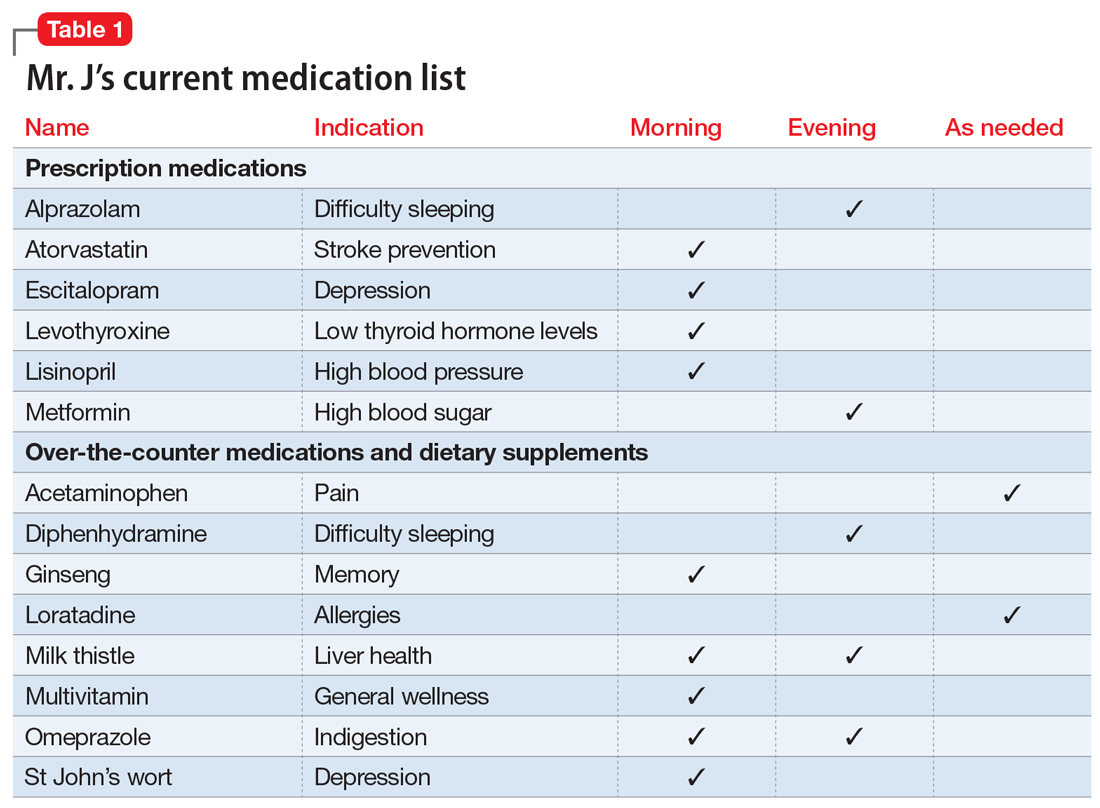

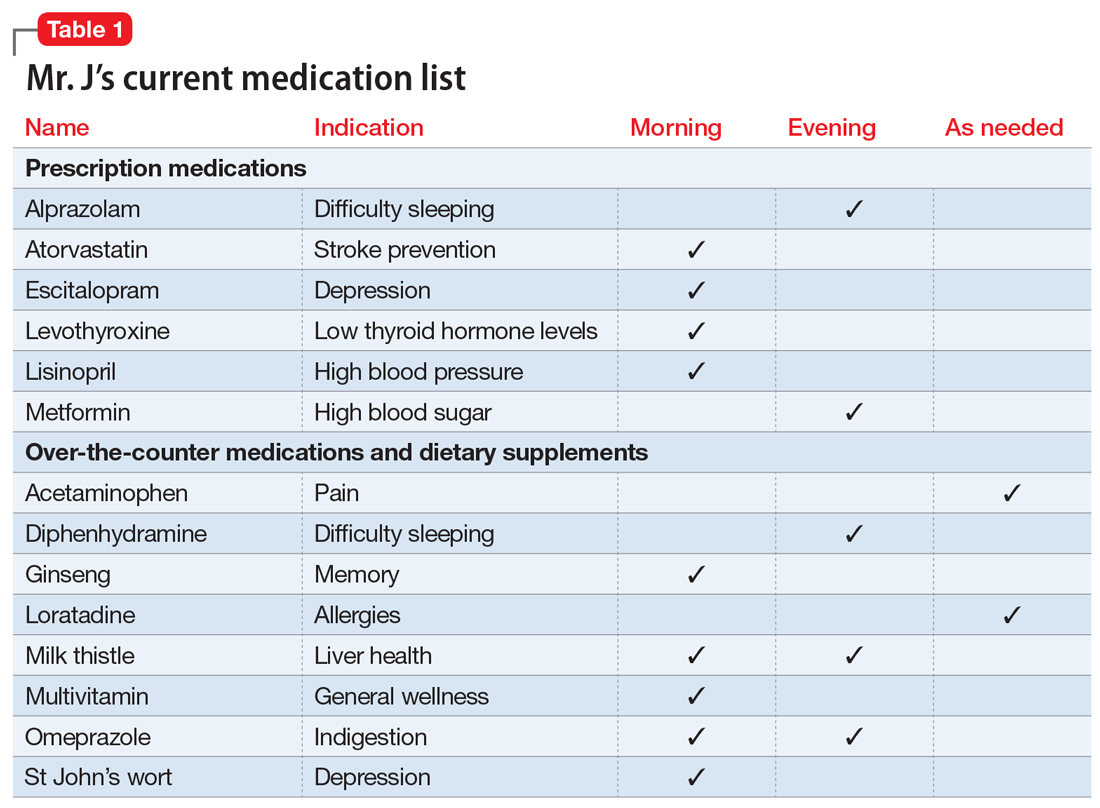

You review the list of Mr. J’s current prescription medications, which include alprazolam 0.5 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, escitalopram 10 mg/d, levothyroxine 0.125 mg/d, lisinopril 20 mg/d, and metformin XR 1,000 mg/d. Mr. J reports taking over-the-counter (OTC) acetaminophen as needed for pain, diphenhydramine for insomnia, loratadine as needed for allergic rhinitis, and omeprazole for 2 years for indigestion. After further questioning, he also reports taking ginseng, milk thistle, a multivitamin, and, based on a friend’s recommendation, St John’s Wort (Table 1).

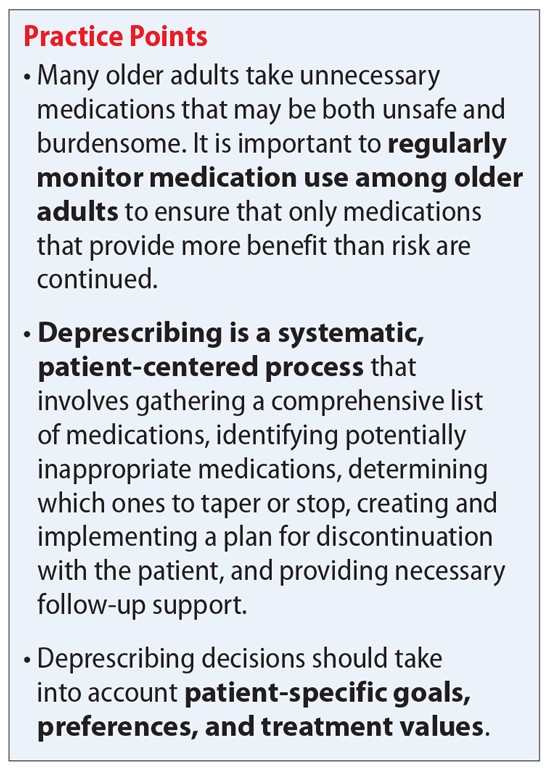

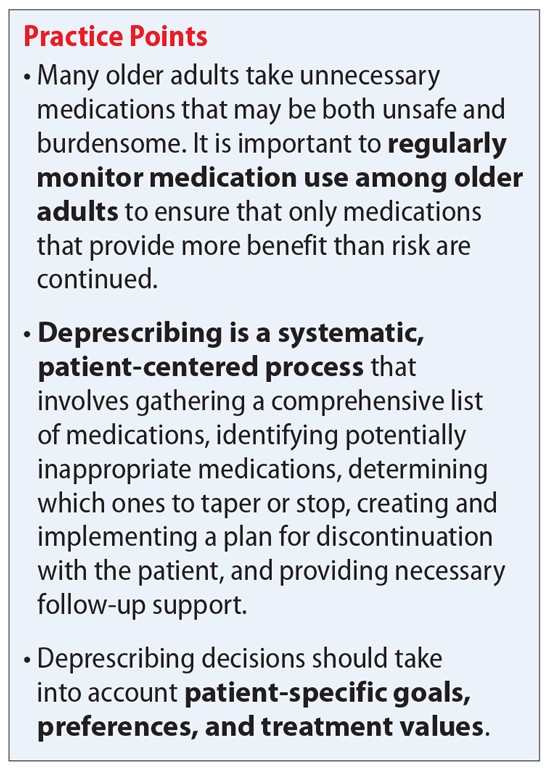

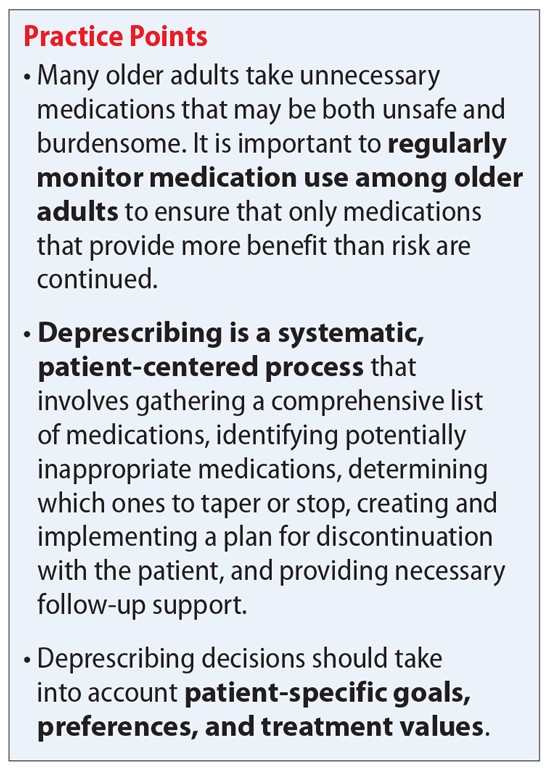

Similar to Mr. J, many older adults take multiple medications to manage chronic health conditions and promote their overall health. On average, 30% of older adults take ≥5 medications.1 Among commonly prescribed medications for these patients, an estimated 1 in 5 of may be inappropriate.1 Older adults have high rates of polypharmacy (often defined as taking ≥5 medications1), age-related physiological changes, increased number of comorbidities, and frailty, all of which can increase the risk of medication-related adverse events.2 As a result, older patients’ medications should be regularly evaluated to determine if each medication is appropriate to continue or should be tapered or stopped.

Deprescribing, in which medications are tapered or discontinued using a patient-centered approach, should be considered when a patient is no longer receiving benefit from a medication, or when the harm may exceed the benefit.1,3

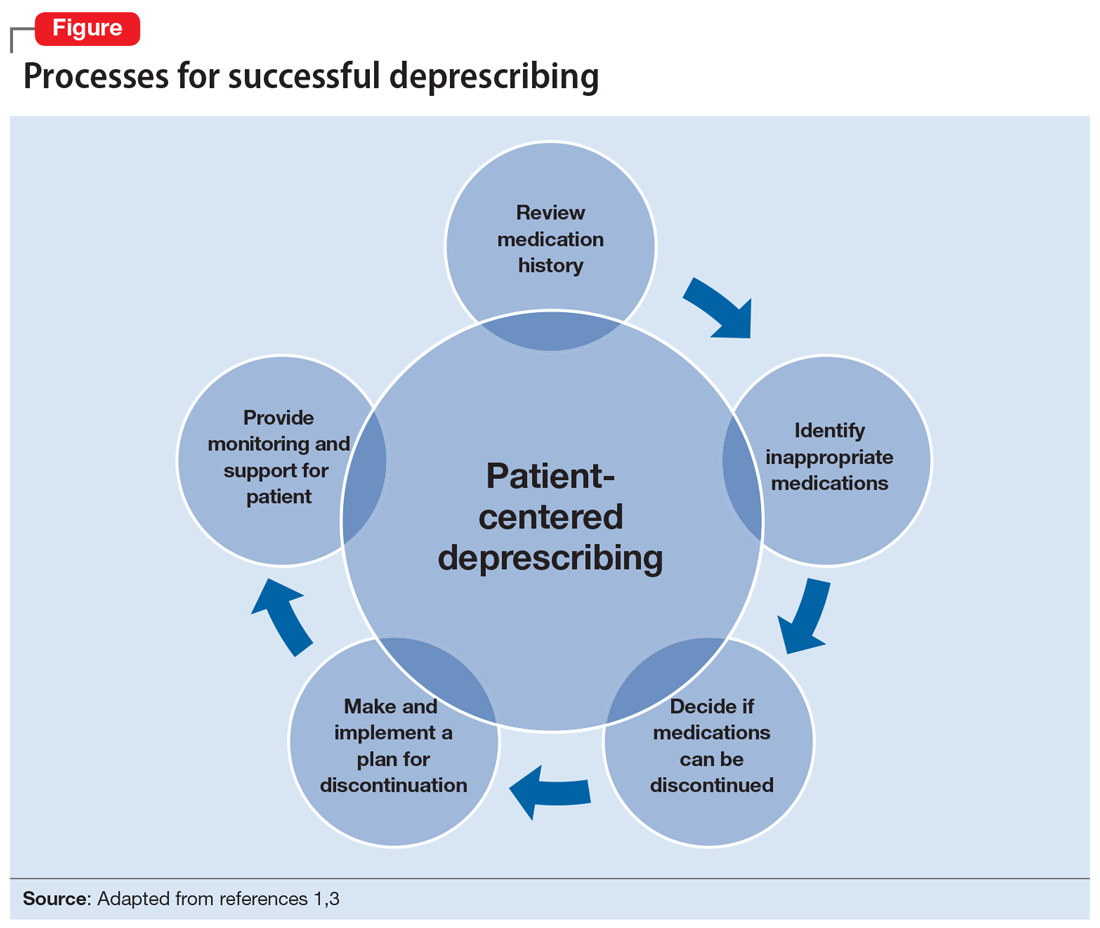

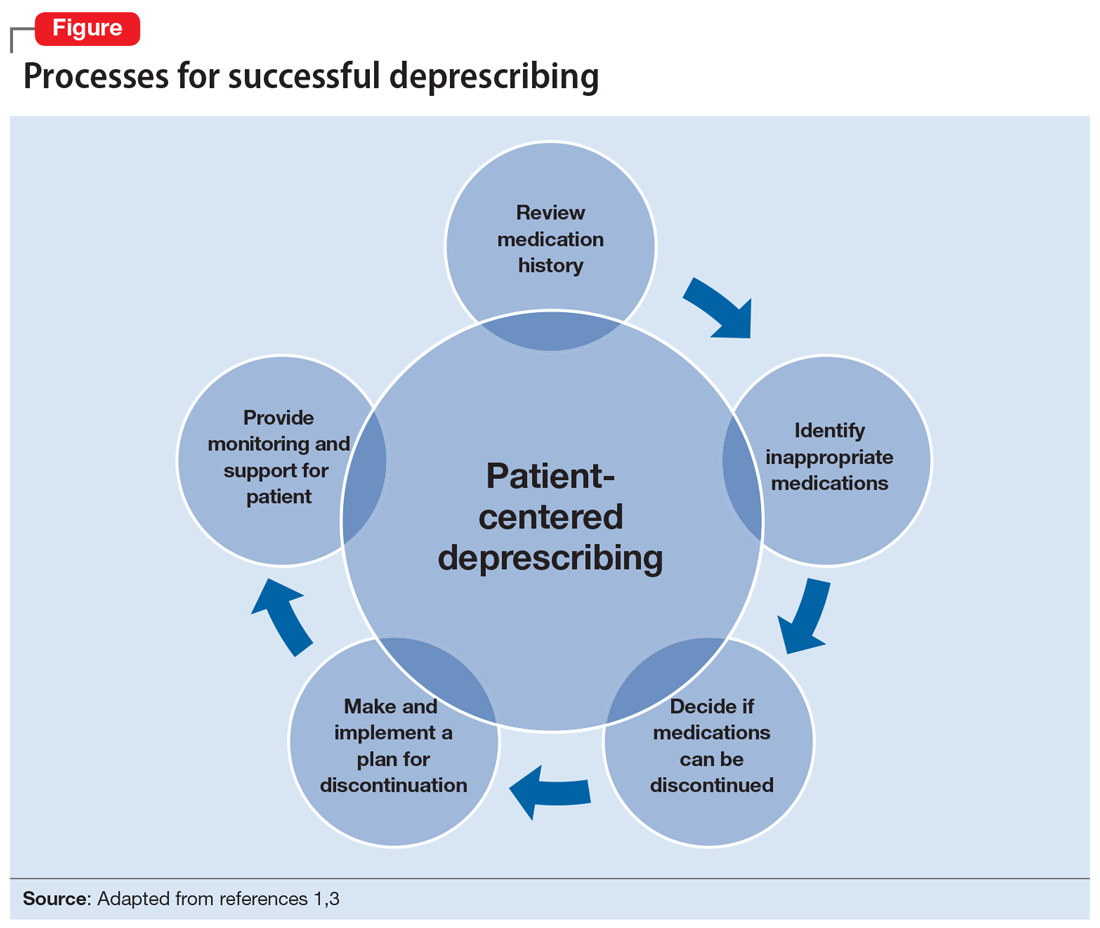

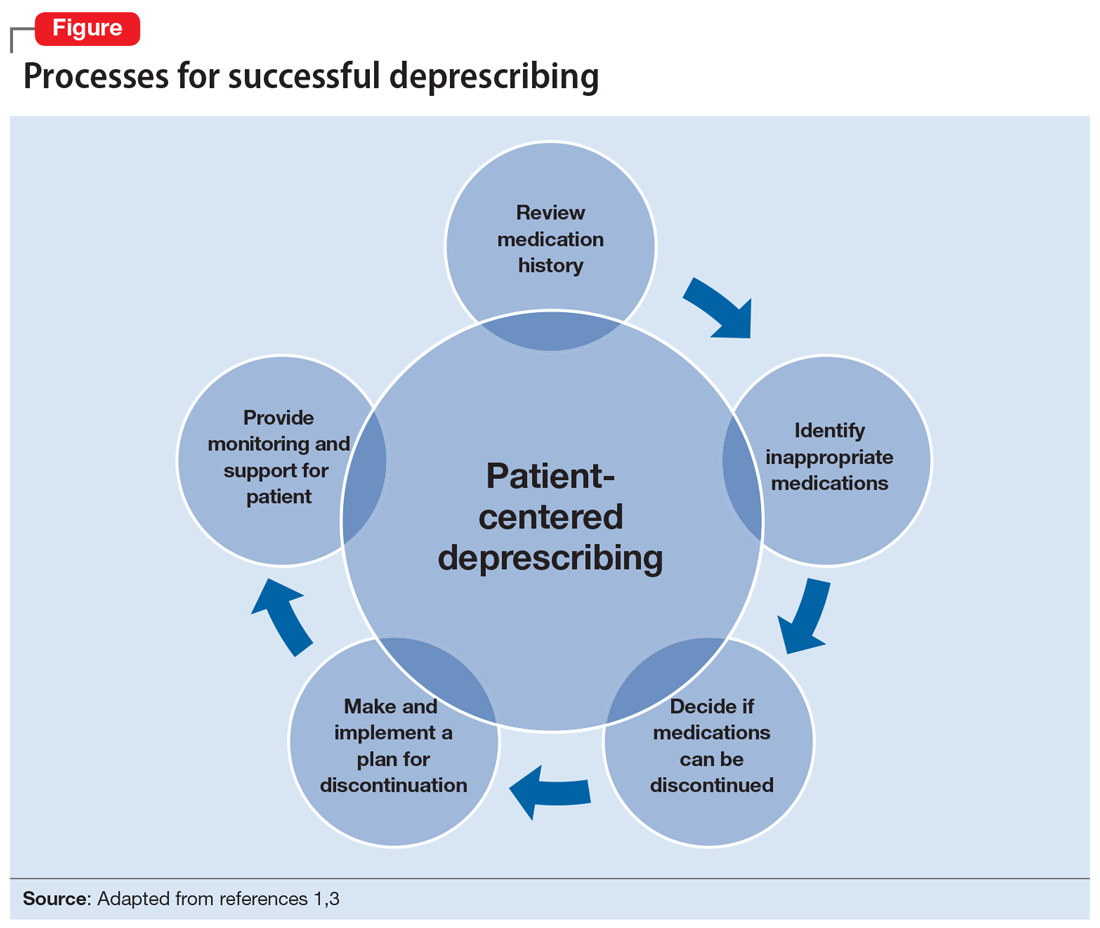

Several researchers1,3 and organizations have published detailed descriptions of and guidelines for the process of deprescribing (see Related Resources). Here we provide a brief overview of this process (Figure1,3). The first step is to assemble a list of all prescription and OTC medications, herbal products, vitamins, or nutritional supplements the patient is taking. It is important to specifically ask patients about their use of nonprescription products, because these products are infrequently documented in medical records.

The second step is to evaluate the indication, effectiveness, safety, and patient’s adherence to each medication while beginning to consider opportunities to limit treatment burden and the risk of harm from medications. Ideally, this assessment should involve a patient-centered conversation that considers the patient’s goals, preferences, and treatment values. Many resources can be used to evaluate which medications might be inappropriate for an older adult. Two examples are the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria5 and STOPP/START criteria.6 By looking at these resources, you could identify that (for example) anticholinergic medications should be avoided in older patients due to an increased risk of adverse effects, change in cognitive status, and falls.5,6 These resources can aid in identifying, prioritizing, and deprescribing potentially harmful and/or inappropriate medications.

The next step is to decide whether any medications should be discontinued. Whenever possible, include the patient in this conversation, as they may have strong feelings about their current medication regimen. When there are multiple medications that can be discontinued, consider which medication to stop first based on potential harm, patient resistance, and other factors.

Continue to: Subsequently, work with...

Subsequently, work with the patient to create a plan for stopping or lowering the dose or frequency of the medication. These changes should be individualized based on the patient’s preferences as well as the properties of the medication. For example, some medications can be immediately discontinued, while others (eg, benzodiazepines) may need to be slowly tapered. It is important to consider if the patient will need to switch to a safer medication, change their behaviors (eg, lifestyle changes), or engage in alternative treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia) when they stop their current medication. Take an active role in monitoring your patient during this process, and encourage them to reach out to you or to their primary clinician if they have concerns.

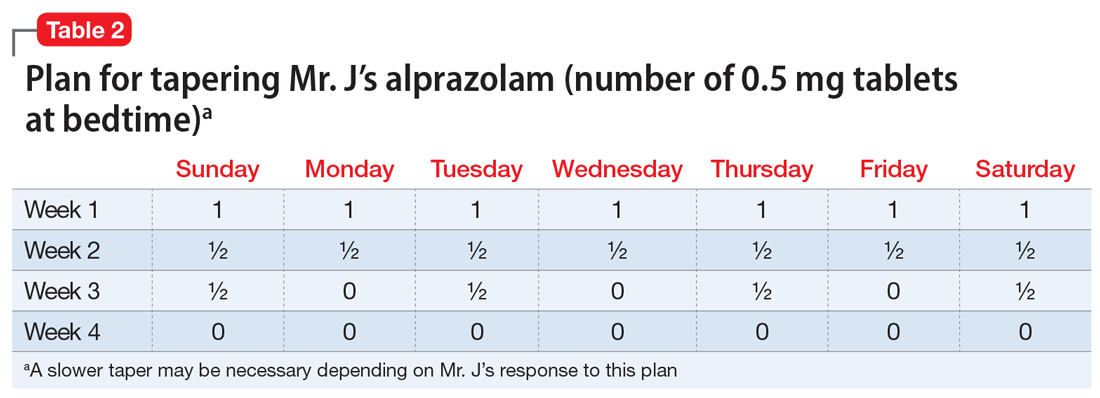

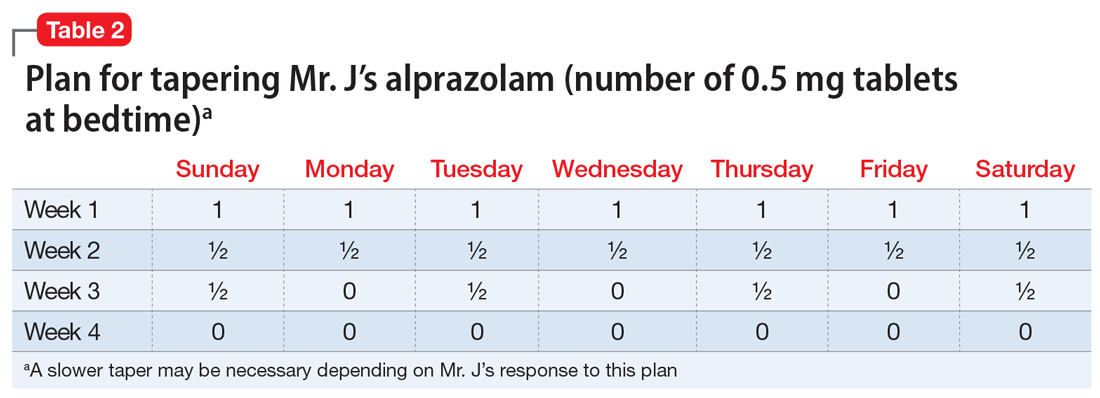

CASE CONTINUED

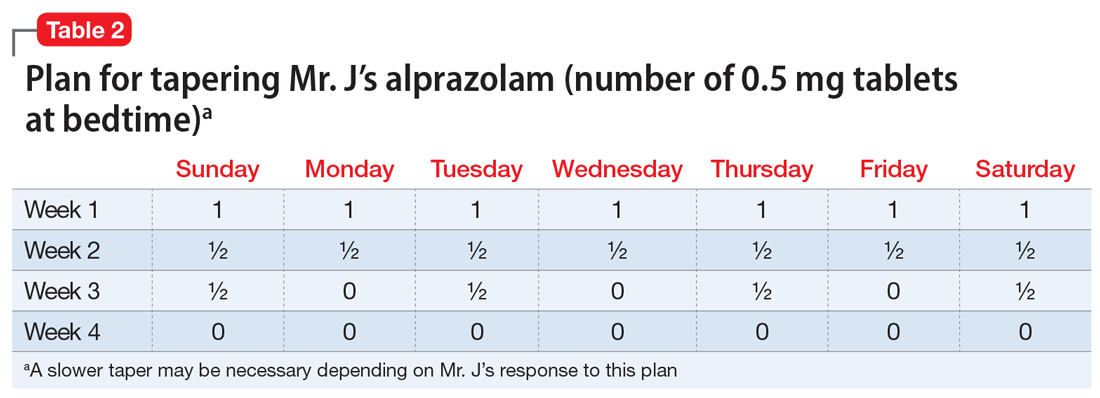

Mr. J is a candidate for deprescribing because he has expressed concerns about his current regimen, and because he is taking potentially unsafe medications. The 2 medications he’s taking that may cause the most harm are diphenhydramine and alprazolam, due to the risk of cognitive impairment and falls. Through a patient-centered conversation, Mr. J says he is willing to stop diphenhydramine immediately and taper off the alprazolam over the next month, with the support of a tapering chart (Table 2). You explain to him that a long tapering of alprazolam may be necessary. He is willing to try good sleep hygiene practices and will put off starting trazodone as an alternative to diphenhydramine until he sees if it will be necessary. You make a note to follow up with him in 1 week to assess his insomnia and adherence to the new treatment plan. You also teach Mr. J that some of his supplements may interact with his prescription medications, such as St John’s Wort with escitalopram (ie, risk of serotonin syndrome) and ginseng with metformin (ie, risk for hypoglycemia). He says he doesn’t take ginseng, milk thistle, or St John’s Wort regularly, and because he feels they do not offer any benefit, he will stop taking them. He says that at his next visit with his primary care physician, he will bring up the idea of stopping omeprazole.

Related Resources

- Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing guidelines and algorithms. https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-guidelines-algorithms/

- US Deprescribing Research Network. Resources for Clinicians. https://deprescribingresearch.org/resources-2/resources-for-clinicians/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Zestril

Metformin XR • Glucophage XR

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

2. Gibson G, Kennedy LH, Barlow G. Polypharmacy in older adults. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):40-46.

3. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmcol. 2014;78(4):738-747.

4. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1021-1031.

5. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.

Mr. J, age 73, has a 25-year history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. His medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, insomnia, and allergic rhinitis. His last laboratory test results indicate his hemoglobin A1c, thyroid-stimulating hormone, low-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure measurements are at goal. He believes his conditions are well controlled but cites concerns about taking multiple medications each day and being able to afford his medications.

You review the list of Mr. J’s current prescription medications, which include alprazolam 0.5 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, escitalopram 10 mg/d, levothyroxine 0.125 mg/d, lisinopril 20 mg/d, and metformin XR 1,000 mg/d. Mr. J reports taking over-the-counter (OTC) acetaminophen as needed for pain, diphenhydramine for insomnia, loratadine as needed for allergic rhinitis, and omeprazole for 2 years for indigestion. After further questioning, he also reports taking ginseng, milk thistle, a multivitamin, and, based on a friend’s recommendation, St John’s Wort (Table 1).

Similar to Mr. J, many older adults take multiple medications to manage chronic health conditions and promote their overall health. On average, 30% of older adults take ≥5 medications.1 Among commonly prescribed medications for these patients, an estimated 1 in 5 of may be inappropriate.1 Older adults have high rates of polypharmacy (often defined as taking ≥5 medications1), age-related physiological changes, increased number of comorbidities, and frailty, all of which can increase the risk of medication-related adverse events.2 As a result, older patients’ medications should be regularly evaluated to determine if each medication is appropriate to continue or should be tapered or stopped.

Deprescribing, in which medications are tapered or discontinued using a patient-centered approach, should be considered when a patient is no longer receiving benefit from a medication, or when the harm may exceed the benefit.1,3

Several researchers1,3 and organizations have published detailed descriptions of and guidelines for the process of deprescribing (see Related Resources). Here we provide a brief overview of this process (Figure1,3). The first step is to assemble a list of all prescription and OTC medications, herbal products, vitamins, or nutritional supplements the patient is taking. It is important to specifically ask patients about their use of nonprescription products, because these products are infrequently documented in medical records.

The second step is to evaluate the indication, effectiveness, safety, and patient’s adherence to each medication while beginning to consider opportunities to limit treatment burden and the risk of harm from medications. Ideally, this assessment should involve a patient-centered conversation that considers the patient’s goals, preferences, and treatment values. Many resources can be used to evaluate which medications might be inappropriate for an older adult. Two examples are the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria5 and STOPP/START criteria.6 By looking at these resources, you could identify that (for example) anticholinergic medications should be avoided in older patients due to an increased risk of adverse effects, change in cognitive status, and falls.5,6 These resources can aid in identifying, prioritizing, and deprescribing potentially harmful and/or inappropriate medications.

The next step is to decide whether any medications should be discontinued. Whenever possible, include the patient in this conversation, as they may have strong feelings about their current medication regimen. When there are multiple medications that can be discontinued, consider which medication to stop first based on potential harm, patient resistance, and other factors.

Continue to: Subsequently, work with...

Subsequently, work with the patient to create a plan for stopping or lowering the dose or frequency of the medication. These changes should be individualized based on the patient’s preferences as well as the properties of the medication. For example, some medications can be immediately discontinued, while others (eg, benzodiazepines) may need to be slowly tapered. It is important to consider if the patient will need to switch to a safer medication, change their behaviors (eg, lifestyle changes), or engage in alternative treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia) when they stop their current medication. Take an active role in monitoring your patient during this process, and encourage them to reach out to you or to their primary clinician if they have concerns.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J is a candidate for deprescribing because he has expressed concerns about his current regimen, and because he is taking potentially unsafe medications. The 2 medications he’s taking that may cause the most harm are diphenhydramine and alprazolam, due to the risk of cognitive impairment and falls. Through a patient-centered conversation, Mr. J says he is willing to stop diphenhydramine immediately and taper off the alprazolam over the next month, with the support of a tapering chart (Table 2). You explain to him that a long tapering of alprazolam may be necessary. He is willing to try good sleep hygiene practices and will put off starting trazodone as an alternative to diphenhydramine until he sees if it will be necessary. You make a note to follow up with him in 1 week to assess his insomnia and adherence to the new treatment plan. You also teach Mr. J that some of his supplements may interact with his prescription medications, such as St John’s Wort with escitalopram (ie, risk of serotonin syndrome) and ginseng with metformin (ie, risk for hypoglycemia). He says he doesn’t take ginseng, milk thistle, or St John’s Wort regularly, and because he feels they do not offer any benefit, he will stop taking them. He says that at his next visit with his primary care physician, he will bring up the idea of stopping omeprazole.

Related Resources

- Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing guidelines and algorithms. https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-guidelines-algorithms/

- US Deprescribing Research Network. Resources for Clinicians. https://deprescribingresearch.org/resources-2/resources-for-clinicians/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Zestril

Metformin XR • Glucophage XR

Trazodone • Desyrel

Mr. J, age 73, has a 25-year history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. His medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, insomnia, and allergic rhinitis. His last laboratory test results indicate his hemoglobin A1c, thyroid-stimulating hormone, low-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure measurements are at goal. He believes his conditions are well controlled but cites concerns about taking multiple medications each day and being able to afford his medications.

You review the list of Mr. J’s current prescription medications, which include alprazolam 0.5 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, escitalopram 10 mg/d, levothyroxine 0.125 mg/d, lisinopril 20 mg/d, and metformin XR 1,000 mg/d. Mr. J reports taking over-the-counter (OTC) acetaminophen as needed for pain, diphenhydramine for insomnia, loratadine as needed for allergic rhinitis, and omeprazole for 2 years for indigestion. After further questioning, he also reports taking ginseng, milk thistle, a multivitamin, and, based on a friend’s recommendation, St John’s Wort (Table 1).

Similar to Mr. J, many older adults take multiple medications to manage chronic health conditions and promote their overall health. On average, 30% of older adults take ≥5 medications.1 Among commonly prescribed medications for these patients, an estimated 1 in 5 of may be inappropriate.1 Older adults have high rates of polypharmacy (often defined as taking ≥5 medications1), age-related physiological changes, increased number of comorbidities, and frailty, all of which can increase the risk of medication-related adverse events.2 As a result, older patients’ medications should be regularly evaluated to determine if each medication is appropriate to continue or should be tapered or stopped.

Deprescribing, in which medications are tapered or discontinued using a patient-centered approach, should be considered when a patient is no longer receiving benefit from a medication, or when the harm may exceed the benefit.1,3

Several researchers1,3 and organizations have published detailed descriptions of and guidelines for the process of deprescribing (see Related Resources). Here we provide a brief overview of this process (Figure1,3). The first step is to assemble a list of all prescription and OTC medications, herbal products, vitamins, or nutritional supplements the patient is taking. It is important to specifically ask patients about their use of nonprescription products, because these products are infrequently documented in medical records.

The second step is to evaluate the indication, effectiveness, safety, and patient’s adherence to each medication while beginning to consider opportunities to limit treatment burden and the risk of harm from medications. Ideally, this assessment should involve a patient-centered conversation that considers the patient’s goals, preferences, and treatment values. Many resources can be used to evaluate which medications might be inappropriate for an older adult. Two examples are the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria5 and STOPP/START criteria.6 By looking at these resources, you could identify that (for example) anticholinergic medications should be avoided in older patients due to an increased risk of adverse effects, change in cognitive status, and falls.5,6 These resources can aid in identifying, prioritizing, and deprescribing potentially harmful and/or inappropriate medications.

The next step is to decide whether any medications should be discontinued. Whenever possible, include the patient in this conversation, as they may have strong feelings about their current medication regimen. When there are multiple medications that can be discontinued, consider which medication to stop first based on potential harm, patient resistance, and other factors.

Continue to: Subsequently, work with...

Subsequently, work with the patient to create a plan for stopping or lowering the dose or frequency of the medication. These changes should be individualized based on the patient’s preferences as well as the properties of the medication. For example, some medications can be immediately discontinued, while others (eg, benzodiazepines) may need to be slowly tapered. It is important to consider if the patient will need to switch to a safer medication, change their behaviors (eg, lifestyle changes), or engage in alternative treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia) when they stop their current medication. Take an active role in monitoring your patient during this process, and encourage them to reach out to you or to their primary clinician if they have concerns.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J is a candidate for deprescribing because he has expressed concerns about his current regimen, and because he is taking potentially unsafe medications. The 2 medications he’s taking that may cause the most harm are diphenhydramine and alprazolam, due to the risk of cognitive impairment and falls. Through a patient-centered conversation, Mr. J says he is willing to stop diphenhydramine immediately and taper off the alprazolam over the next month, with the support of a tapering chart (Table 2). You explain to him that a long tapering of alprazolam may be necessary. He is willing to try good sleep hygiene practices and will put off starting trazodone as an alternative to diphenhydramine until he sees if it will be necessary. You make a note to follow up with him in 1 week to assess his insomnia and adherence to the new treatment plan. You also teach Mr. J that some of his supplements may interact with his prescription medications, such as St John’s Wort with escitalopram (ie, risk of serotonin syndrome) and ginseng with metformin (ie, risk for hypoglycemia). He says he doesn’t take ginseng, milk thistle, or St John’s Wort regularly, and because he feels they do not offer any benefit, he will stop taking them. He says that at his next visit with his primary care physician, he will bring up the idea of stopping omeprazole.

Related Resources

- Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing guidelines and algorithms. https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-guidelines-algorithms/

- US Deprescribing Research Network. Resources for Clinicians. https://deprescribingresearch.org/resources-2/resources-for-clinicians/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Zestril

Metformin XR • Glucophage XR

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

2. Gibson G, Kennedy LH, Barlow G. Polypharmacy in older adults. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):40-46.

3. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmcol. 2014;78(4):738-747.

4. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1021-1031.

5. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.

1. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

2. Gibson G, Kennedy LH, Barlow G. Polypharmacy in older adults. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):40-46.

3. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmcol. 2014;78(4):738-747.

4. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1021-1031.

5. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.

The woman who kept passing out

CASE An apparent code blue

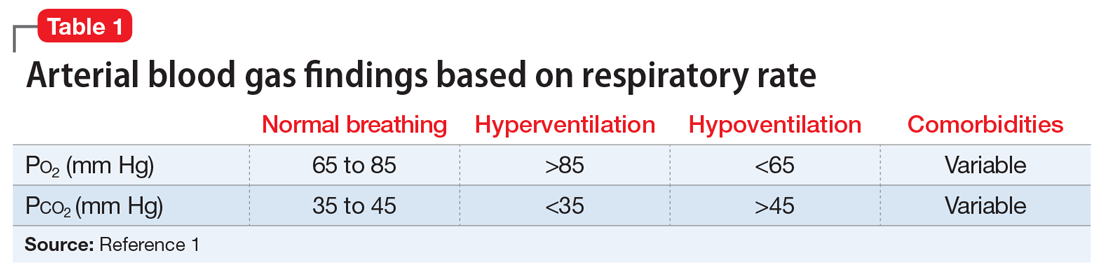

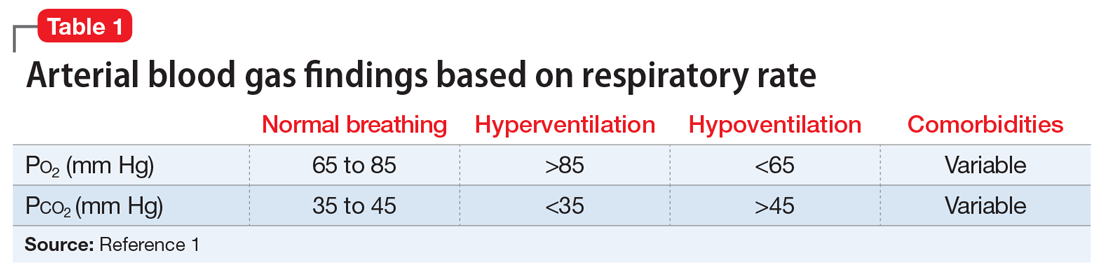

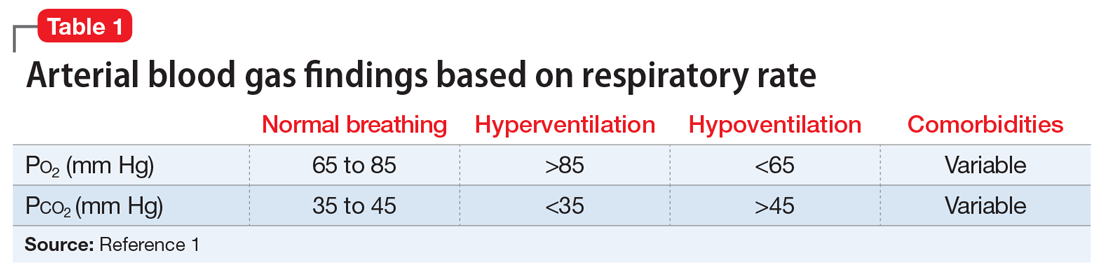

Ms. B, age 44, has posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She presents to the hospital for an outpatient orthopedic appointment. In the hospital cafeteria, she becomes unresponsive, and a code blue is called. Ms. B is admitted to the medicine intensive care unit (MICU), where she is sedated with propofol and intubated. The initial blood work for this supposed hypoxic event shows a Po2 of 336 mm Hg (reference range: 80 to 100 mm Hg; see Table 11). The MICU calls the psychiatric consultation-liaison (CL) team to evaluate this paradoxical finding.

HISTORY A pattern of similar symptoms

In the 12 months before her current hospital visit, Ms. B presented to the emergency department (ED) on 3 occasions. These were for a syncopal episode with shortness of breath and 2 incidences of passing out while receiving diagnostic testing. Each time, on Ms. B’s insistence, she was admitted and intubated. Once extubated, Ms. B left against medical advice (AMA) after a short period. She has an allergy list that includes more than 30 drugs spanning multiple drug classes, including antibiotics, contrast material, and some gamma aminobutyric acidergic medications. Notably, Ms. B is not allergic to benzodiazepines. She also has undergone more than 10 surgeries, including bariatric surgery, cholecystectomy, appendectomy, neurostimulator placement, and colon surgery.

EVALUATION Clues suggest a potential psychiatric diagnosis

When the CL team initially consults, Ms. B is intubated and sedated with dexmedetomidine, which limits the examination. She is able to better participate during interviews as she is weaned from sedation while in the MICU. A mental status exam reveals a woman who appears older than 44. She is oriented to person, place, time, and situation despite being mildly somnolent and having poor eye contact. Ms. B displays restricted affect, psychomotor retardation, and slowed speech. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, intent, or plans; paranoia or other delusions; and any visual, auditory, somatic, or olfactory hallucinations. Her thought process is goal-directed and linear but with thought-blocking. Ms. B’s initial arterial blood gas (ABG) test is abnormal, showing she is acidotic with both hypercarbia and extreme hyperoxemia (pH 7.21 and P

[polldaddy:11104278]

The authors’ observations

Under normal code blue situations, patients are expected to have respiratory acidosis, with low Po2 levels and high Pco2 levels. However, Ms. B’s ABG revealed she had high Po2 levels and high Pco2levels. Her paradoxical findings of elevated Pco2 on the initial ABG were likely due to hyperventilation on pure oxygen in the context of her underlying chronic lung disease and respiratory fatigue.

The clinical team contacted Ms. B’s husband, who stated that during her prior hospitalizations, she had a history of physical aggression with staff when weaned off sedation. Additionally, he reported that 1 week before presenting to the ED, she had wanted to meet her dead father.

A review of Ms. B’s medical records revealed she had been prescribed alprazolam, 2 mg 3 times a day as needed, so she was prescribed scheduled lorazepam in addition to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) protocol to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. Ms. B had 2 prior long-term monitoring for epilepsy evaluations in our system for evaluation of seizure-like behavior. The first evaluation showed an episode of stiffening with tremulousness and eye closure for 20 to 25 minutes with no epileptiform discharge or other EEG changes. The second showed diffuse bihemispheric dysfunction consistent with toxic metabolic encephalopathies, but no epileptiform abnormality.

When hospital staff would collect arterial blood, Ms. B had periods when her eyes were closed, muscles flaccid, and she displayed an unresponsiveness to voice, touch, and noxious stimulation, including sternal rub. Opening her eyelids during these episodes revealed slow, wandering eye movements, but no nystagmus or fixed eye deviation. Vital signs and oxygenation were unchanged during these episodes. When this occurred, the phlebotomist would leave the room to notify the attending physician on call, but Ms. B would quickly return to her mildly impaired baseline. When the attending entered the room, Ms. B reported no memory of what happened during these episodes. At this point, the CL team begins to suspect that Ms. B may have factitious disorder.

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT Agitation, possibly due to benzo withdrawal

Ms. B is successfully weaned off sedation and transferred out of the MICU for continued CIWA protocol management on a different floor. However, she breaks free of her soft restraint, strips naked, and attempts to barricade her room to prevent staff from entering. Nursing staff administers haloperidol 4 mg to manage agitation.

[polldaddy:11104279]

The authors’ observations

To better match Ms. B’s prior alprazolam prescription, the treatment team increased her lorazepam dosage to a dose higher than her CIWA protocol. This allowed the team to manage her withdrawal, as they believed that benzodiazepine withdrawal was a major driving force behind her decision to leave AMA following prior hospitalizations. This enabled the CL team to coordinate care as Ms. B transitioned to outpatient management. The team suspected Ms. B may have factitious disorder, but did not discuss that specific diagnosis with the patient. However, they did talk through general treatment options with her.

Challenges of factitious disorder

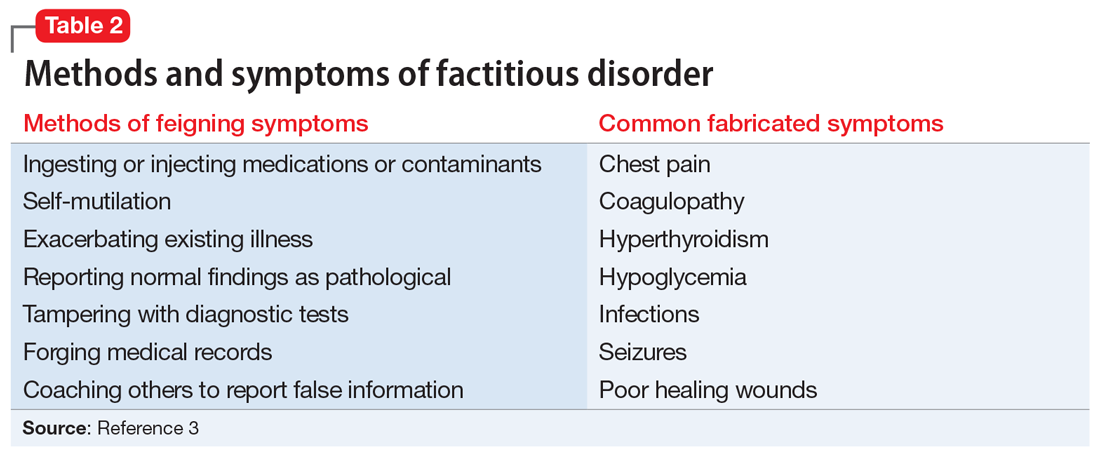

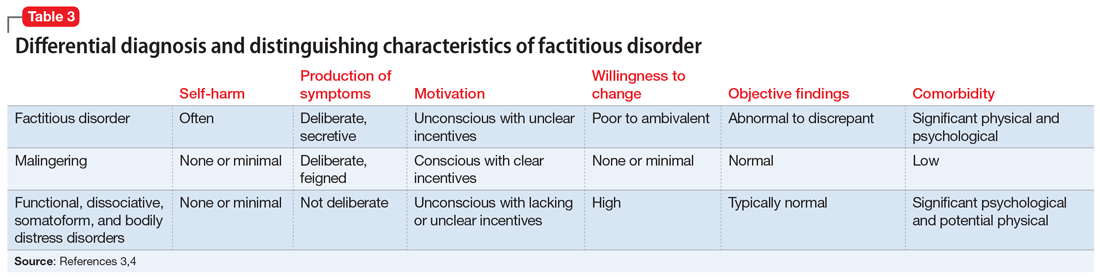

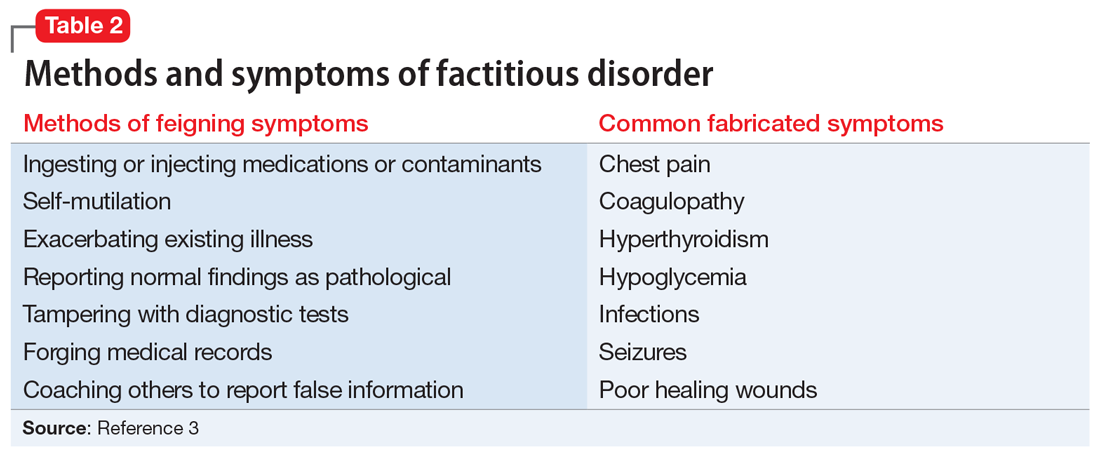

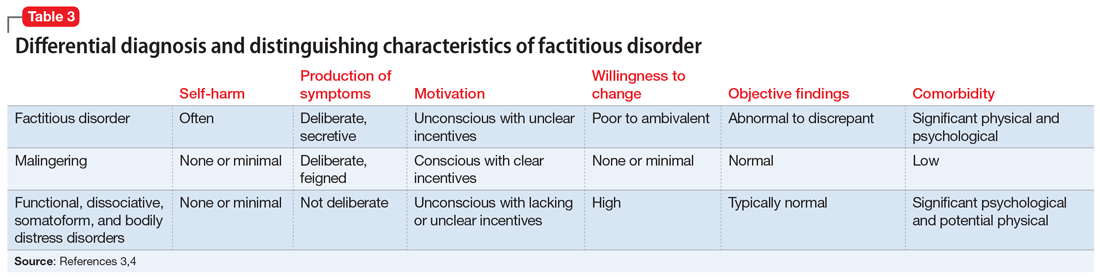

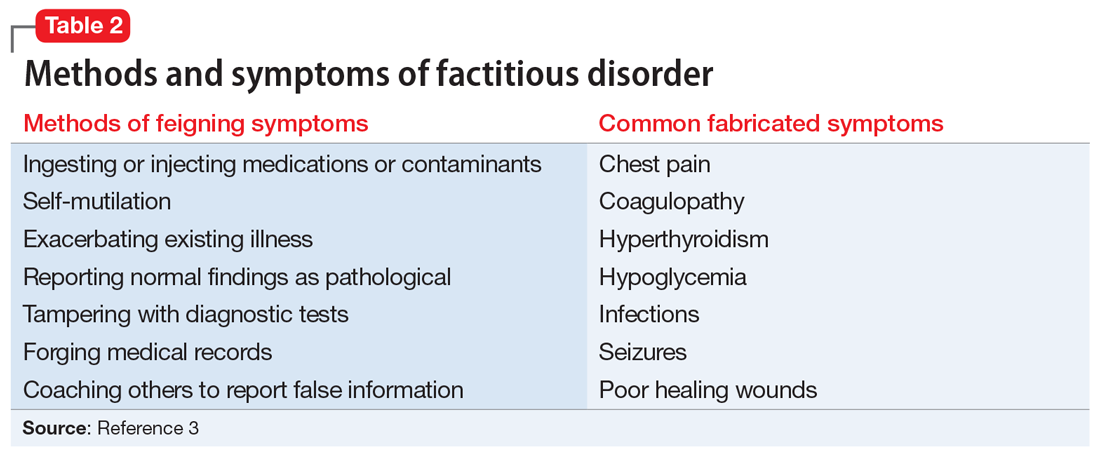

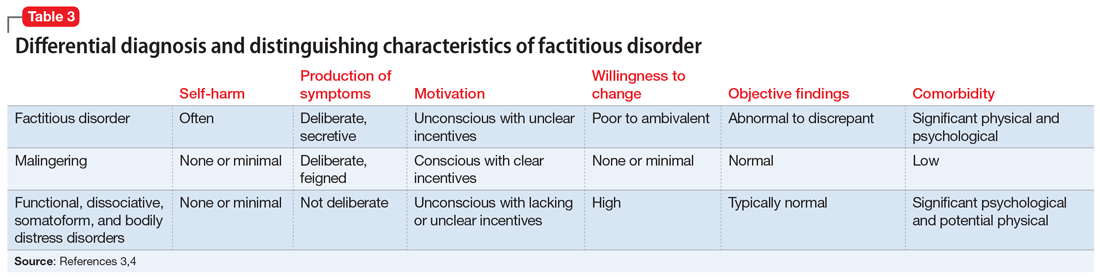

DSM-5 classifies factitious disorder under Somatic Symptoms and Related Disorders, and describes it as “deceptive behavior in the absence of external incentives.”2 A prominent feature of factitious disorder is a persistent concern related to illness and identity causing significant distress and impairment.2 Patients with factitious disorder enact deceptive behavior such as intentionally falsifying medical and/or psychological symptoms, inducing illness to themselves, or exaggerated signs and symptoms.3 External motives and rewards are often unidentifiable but could result in a desire to receive care, an “adrenaline rush,” or a sense of control over health care personnel.3Table 23 outlines additional symptoms of factitious disorder. When evaluating a patient who may have factitious disorder, the differential diagnosis may include malingering, conversion disorder, somatic symptom disorder, delusional disorder somatic type, borderline personality disorder, and other impulse-control disorders (Table 33,4).

Consequences of factitious disorder include self-harm and a significant impact on health care costs related to excessive and inappropriate hospital admissions and treatments. Factitious disorder represents approximately 0.6% to 3% of referrals from general medicine and 0.02% to 0.9% of referrals from specialists.3

Patients may be treated at multiple hospitals, pharmacies, and medical institutions because of deceptive behaviors that lead to a lack of complete and accurate documentation and fragmentation in communication and care. Internet access may also play a role in enabling skillful and versatile feigning of symptoms. This is compounded with further complexity because many of these patients suffer from comorbid conditions.

Continue to: Management of self-imposed...

Management of self-imposed factitious disorder includes acute treatment in inpatient settings with multidisciplinary teams as well as in longer-term settings with ongoing medical and psychological support.5 The key to achieving positive outcomes in both settings is negotiation and agreement with the patient on their diagnosis and engagement in treatment.5 There is little evidence available to support the effectiveness of any particular management strategy for factitious disorder, specifically in the inpatient psychiatric setting. A primary reason for this paucity of data is that most patients are lost to follow-up after initiation of a treatment plan.6

Addressing factitious disorder with patients can be particularly difficult; it requires a thoughtful and balanced approach. Typical responses to confrontation of this deceptive behavior involve denial, leaving AMA, or potentially verbal and physical aggression.4 In a review of medical records, Krahn et al6 found that of 71 patients with factitious disorder who were confronted about their role in the illness, only 23% (n = 16) acknowledged factitious behavior. Confrontation can be conceptualized as direct or indirect. In direct confrontation, patients are directly told of their diagnosis. This frequently angers patients, because such confrontation can be interpreted as humiliating and can cause them to seek care from another clinician, leave the hospital AMA, or increase their self-destructive behavior.4 In contrast, indirect confrontation approaches the conversation with an explanatory view of the maladaptive behaviors, which may allow the patient to be more open to therapy.4 An example of this would be, “When some patients are very upset, they often do something to themselves to create illness as a way of seeking help. We believe that something such as this must be going on and we would like to help you focus on the true nature of your problem, which is emotional distress.” However, there is no evidence that either of these approaches is superior, or that a significant difference in outcomes exists between confrontational and nonconfrontational approaches.7

The treatment for factitious disorder most often initiated in inpatient settings and continued in outpatient care is psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, supportive psychotherapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy.4,8,9 There is, however, no evidence to support the efficacy of one form of psychotherapy over another, or even to establish the efficacy of treatment with psychotherapy compared to no psychotherapy. This is further complicated by some resources that suggest mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, or antidepressants as treatment options for psychiatric comorbidities in patients with factitious disorder; very little evidence supports these agents’ efficacy in treating the patient’s behaviors related to factitious disorder.7

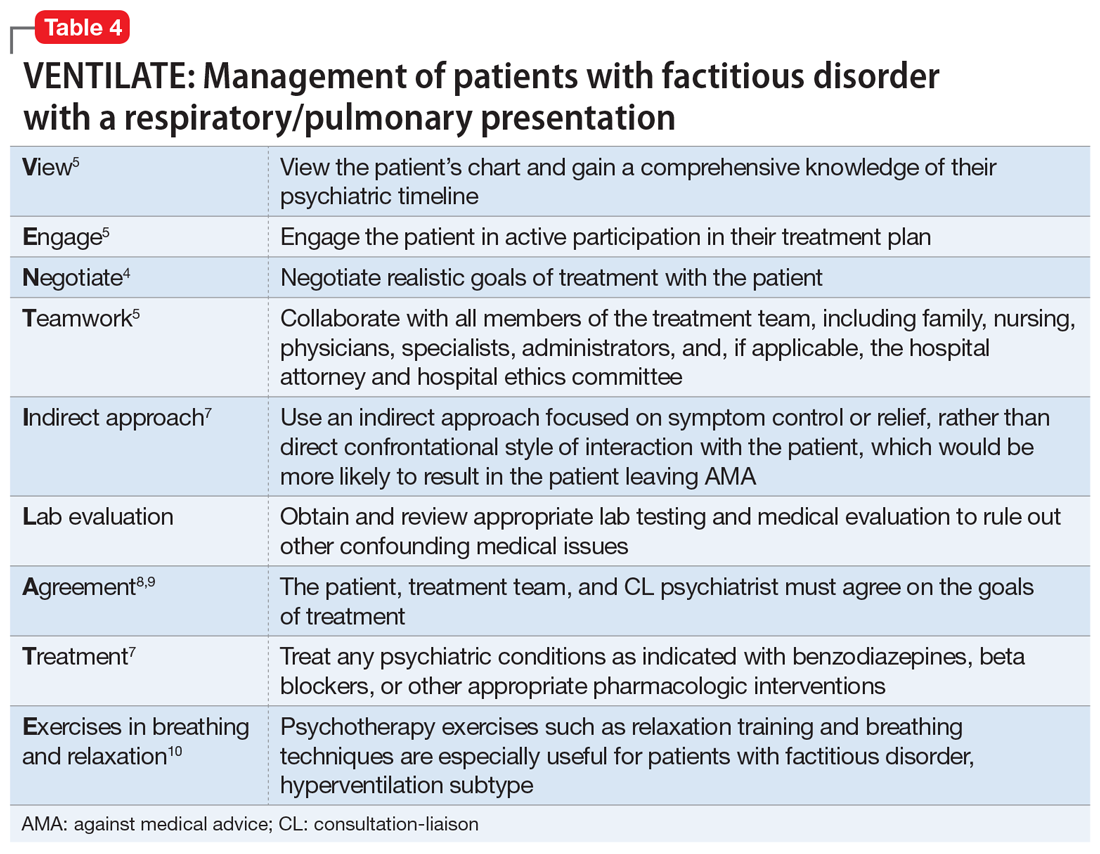

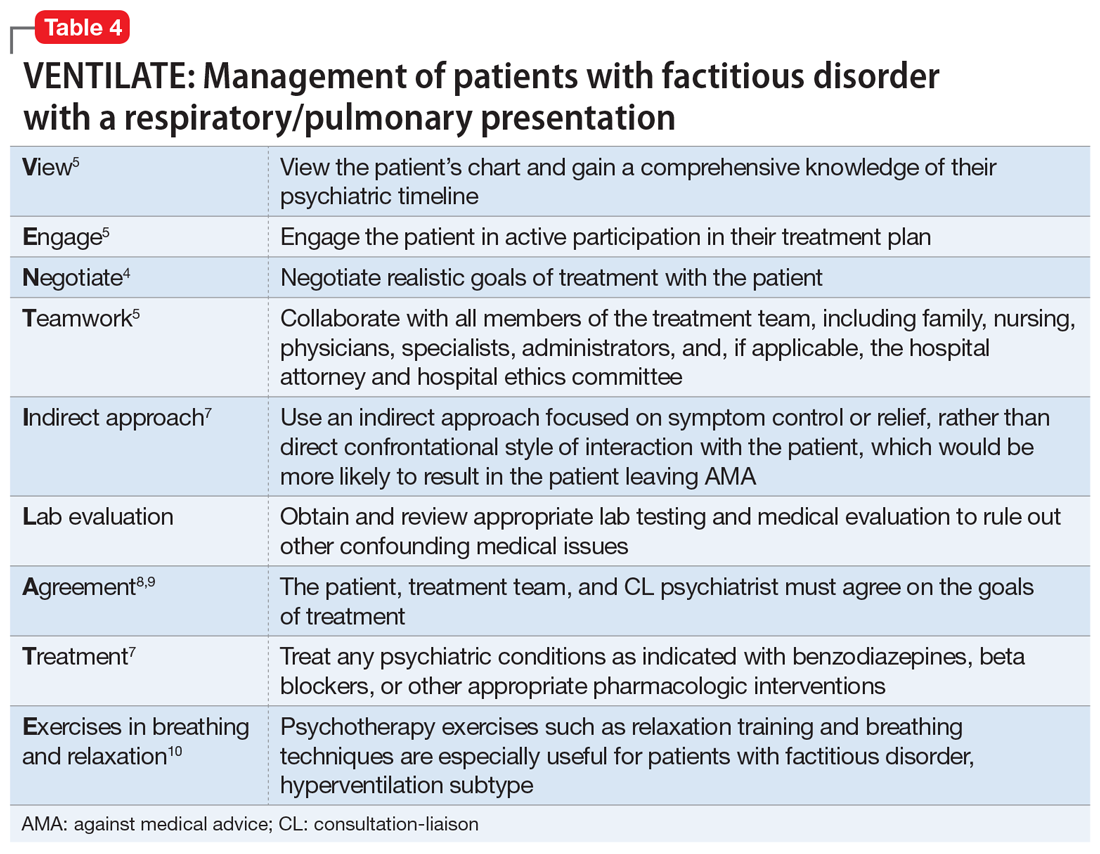

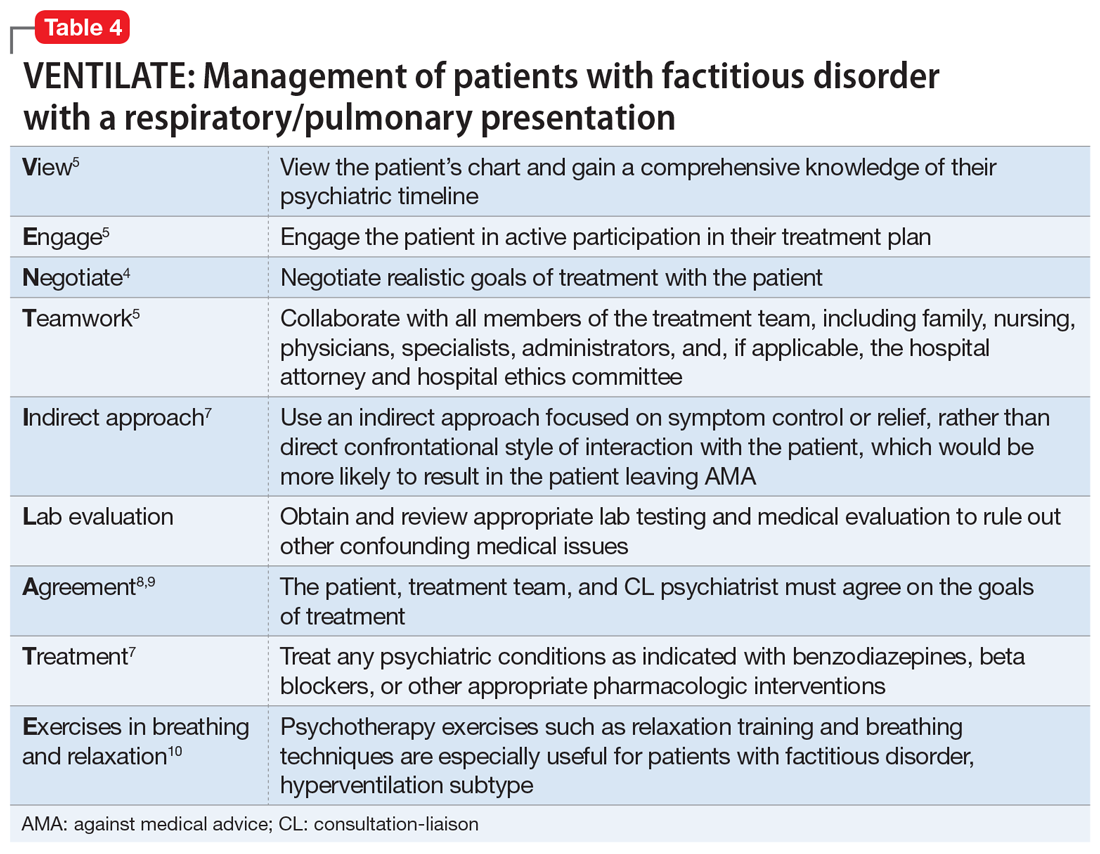

No data are available to support a management strategy for patients with factitious disorder who have a respiratory/pulmonary presentation, such as Ms. B. Suggested treatment options for hyperventilation syndrome include relaxation therapy, breathing exercises, short-acting benzodiazepines, and beta-blockers; there is no evidence to support their efficacy, whether in the context of factitious disorder or another disorder.10 We suggest the acronym VENTILATE to guide the treating psychiatrist in managing a patient with factitious disorder with a respiratory/pulmonary presentation and hyperventilation (Table 44,5,7-10).

Bass et al5 suggest that regardless of the manifestation of a patient’s factitious disorder, for a CL psychiatrist, it is important to consult with the patient’s entire care team, hospital administrators, hospital and personal attorneys, and hospital ethics committee before making treatment decisions that deviate from usual medical practice.

Continue to: OUTCOME

OUTCOME Set up for success at home

Before Ms. B is discharged, her husband is contacted and amenable to removing all objects and medications that Ms. B could potentially use to cause self-harm at home. A follow-up with Ms. B’s psychiatric outpatient clinician is scheduled for the following week. By the end of her hospital stay, she denies any suicidal or homicidal ideation, delusions, or hallucinations. Ms. B is able to express multiple protective factors against the risk of self-harm, and engages in meaningful discussions on safety planning with her husband and the psychiatry team. This is the first time in more than 1 year that Ms. B does not leave the hospital AMA.

Bottom Line

Patients with factitious disorder may present with respiratory/pulmonary symptoms. There is limited data to support the efficacy of one approach over another for treating factitious disorder in an inpatient setting, but patient engagement and collaboration with the entire care team is critical to managing this difficult scenario.

Related Resources

- de Similien R, Lee BL, Hairston DR, et al. Sick, or faking it? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(9):49-52.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

1. Castro D, Patil SM, Keenaghan M. Arterial Blood Gas. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536919/

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Yates GP, Feldman MD. Factitious disorder: a systematic review of 455 cases in the professional literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;41:20-28.

4. Ford CV, Sonnier L, McCullumsmith C. Deception syndromes: factitious disorders and malingering. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine and Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Assocation Publishing, Inc.; 2018:323-340.

5. Bass C, Halligan P. Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422-1432.

6. Krahn LE, Li H, O’Connor MK. Patients who strive to be ill: factitious disorder with physical symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1163-1168.

7. Eastwood S, Bisson JI. Management of factitious disorders: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):209-218.

8. Abbass A, Kisely S, Kroenke K. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for somatic disorders. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(5):265-274.

9. McDermott BE, Leamon MH, Feldman MD, et al. Factitious disorder and malingering. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Gabbard GO, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Assocation Publishing, Inc.; 2008:643-664.

10. Jones M, Harvey A, Marston L, et al. Breathing exercises for dysfunctional breathing/hyperventilation syndrome in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(5):CD009041.

CASE An apparent code blue

Ms. B, age 44, has posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She presents to the hospital for an outpatient orthopedic appointment. In the hospital cafeteria, she becomes unresponsive, and a code blue is called. Ms. B is admitted to the medicine intensive care unit (MICU), where she is sedated with propofol and intubated. The initial blood work for this supposed hypoxic event shows a Po2 of 336 mm Hg (reference range: 80 to 100 mm Hg; see Table 11). The MICU calls the psychiatric consultation-liaison (CL) team to evaluate this paradoxical finding.

HISTORY A pattern of similar symptoms

In the 12 months before her current hospital visit, Ms. B presented to the emergency department (ED) on 3 occasions. These were for a syncopal episode with shortness of breath and 2 incidences of passing out while receiving diagnostic testing. Each time, on Ms. B’s insistence, she was admitted and intubated. Once extubated, Ms. B left against medical advice (AMA) after a short period. She has an allergy list that includes more than 30 drugs spanning multiple drug classes, including antibiotics, contrast material, and some gamma aminobutyric acidergic medications. Notably, Ms. B is not allergic to benzodiazepines. She also has undergone more than 10 surgeries, including bariatric surgery, cholecystectomy, appendectomy, neurostimulator placement, and colon surgery.

EVALUATION Clues suggest a potential psychiatric diagnosis

When the CL team initially consults, Ms. B is intubated and sedated with dexmedetomidine, which limits the examination. She is able to better participate during interviews as she is weaned from sedation while in the MICU. A mental status exam reveals a woman who appears older than 44. She is oriented to person, place, time, and situation despite being mildly somnolent and having poor eye contact. Ms. B displays restricted affect, psychomotor retardation, and slowed speech. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, intent, or plans; paranoia or other delusions; and any visual, auditory, somatic, or olfactory hallucinations. Her thought process is goal-directed and linear but with thought-blocking. Ms. B’s initial arterial blood gas (ABG) test is abnormal, showing she is acidotic with both hypercarbia and extreme hyperoxemia (pH 7.21 and P

[polldaddy:11104278]

The authors’ observations

Under normal code blue situations, patients are expected to have respiratory acidosis, with low Po2 levels and high Pco2 levels. However, Ms. B’s ABG revealed she had high Po2 levels and high Pco2levels. Her paradoxical findings of elevated Pco2 on the initial ABG were likely due to hyperventilation on pure oxygen in the context of her underlying chronic lung disease and respiratory fatigue.

The clinical team contacted Ms. B’s husband, who stated that during her prior hospitalizations, she had a history of physical aggression with staff when weaned off sedation. Additionally, he reported that 1 week before presenting to the ED, she had wanted to meet her dead father.

A review of Ms. B’s medical records revealed she had been prescribed alprazolam, 2 mg 3 times a day as needed, so she was prescribed scheduled lorazepam in addition to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) protocol to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. Ms. B had 2 prior long-term monitoring for epilepsy evaluations in our system for evaluation of seizure-like behavior. The first evaluation showed an episode of stiffening with tremulousness and eye closure for 20 to 25 minutes with no epileptiform discharge or other EEG changes. The second showed diffuse bihemispheric dysfunction consistent with toxic metabolic encephalopathies, but no epileptiform abnormality.

When hospital staff would collect arterial blood, Ms. B had periods when her eyes were closed, muscles flaccid, and she displayed an unresponsiveness to voice, touch, and noxious stimulation, including sternal rub. Opening her eyelids during these episodes revealed slow, wandering eye movements, but no nystagmus or fixed eye deviation. Vital signs and oxygenation were unchanged during these episodes. When this occurred, the phlebotomist would leave the room to notify the attending physician on call, but Ms. B would quickly return to her mildly impaired baseline. When the attending entered the room, Ms. B reported no memory of what happened during these episodes. At this point, the CL team begins to suspect that Ms. B may have factitious disorder.

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT Agitation, possibly due to benzo withdrawal

Ms. B is successfully weaned off sedation and transferred out of the MICU for continued CIWA protocol management on a different floor. However, she breaks free of her soft restraint, strips naked, and attempts to barricade her room to prevent staff from entering. Nursing staff administers haloperidol 4 mg to manage agitation.

[polldaddy:11104279]

The authors’ observations

To better match Ms. B’s prior alprazolam prescription, the treatment team increased her lorazepam dosage to a dose higher than her CIWA protocol. This allowed the team to manage her withdrawal, as they believed that benzodiazepine withdrawal was a major driving force behind her decision to leave AMA following prior hospitalizations. This enabled the CL team to coordinate care as Ms. B transitioned to outpatient management. The team suspected Ms. B may have factitious disorder, but did not discuss that specific diagnosis with the patient. However, they did talk through general treatment options with her.

Challenges of factitious disorder

DSM-5 classifies factitious disorder under Somatic Symptoms and Related Disorders, and describes it as “deceptive behavior in the absence of external incentives.”2 A prominent feature of factitious disorder is a persistent concern related to illness and identity causing significant distress and impairment.2 Patients with factitious disorder enact deceptive behavior such as intentionally falsifying medical and/or psychological symptoms, inducing illness to themselves, or exaggerated signs and symptoms.3 External motives and rewards are often unidentifiable but could result in a desire to receive care, an “adrenaline rush,” or a sense of control over health care personnel.3Table 23 outlines additional symptoms of factitious disorder. When evaluating a patient who may have factitious disorder, the differential diagnosis may include malingering, conversion disorder, somatic symptom disorder, delusional disorder somatic type, borderline personality disorder, and other impulse-control disorders (Table 33,4).

Consequences of factitious disorder include self-harm and a significant impact on health care costs related to excessive and inappropriate hospital admissions and treatments. Factitious disorder represents approximately 0.6% to 3% of referrals from general medicine and 0.02% to 0.9% of referrals from specialists.3

Patients may be treated at multiple hospitals, pharmacies, and medical institutions because of deceptive behaviors that lead to a lack of complete and accurate documentation and fragmentation in communication and care. Internet access may also play a role in enabling skillful and versatile feigning of symptoms. This is compounded with further complexity because many of these patients suffer from comorbid conditions.

Continue to: Management of self-imposed...

Management of self-imposed factitious disorder includes acute treatment in inpatient settings with multidisciplinary teams as well as in longer-term settings with ongoing medical and psychological support.5 The key to achieving positive outcomes in both settings is negotiation and agreement with the patient on their diagnosis and engagement in treatment.5 There is little evidence available to support the effectiveness of any particular management strategy for factitious disorder, specifically in the inpatient psychiatric setting. A primary reason for this paucity of data is that most patients are lost to follow-up after initiation of a treatment plan.6

Addressing factitious disorder with patients can be particularly difficult; it requires a thoughtful and balanced approach. Typical responses to confrontation of this deceptive behavior involve denial, leaving AMA, or potentially verbal and physical aggression.4 In a review of medical records, Krahn et al6 found that of 71 patients with factitious disorder who were confronted about their role in the illness, only 23% (n = 16) acknowledged factitious behavior. Confrontation can be conceptualized as direct or indirect. In direct confrontation, patients are directly told of their diagnosis. This frequently angers patients, because such confrontation can be interpreted as humiliating and can cause them to seek care from another clinician, leave the hospital AMA, or increase their self-destructive behavior.4 In contrast, indirect confrontation approaches the conversation with an explanatory view of the maladaptive behaviors, which may allow the patient to be more open to therapy.4 An example of this would be, “When some patients are very upset, they often do something to themselves to create illness as a way of seeking help. We believe that something such as this must be going on and we would like to help you focus on the true nature of your problem, which is emotional distress.” However, there is no evidence that either of these approaches is superior, or that a significant difference in outcomes exists between confrontational and nonconfrontational approaches.7