User login

AMSTERDAM – A simple formula for calculating the risk faced by acutely ill, hospitalized patients for venous thromboembolism was validated in a case-control study with more than 400 patients.

This VTE risk-calculator formula "is the first [risk-assessment model (RAM)] to be validated on a large scale in hospitalized medical patients," Charles E. Mahan, Pharm.D., said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"Applying this RAM could spare 20%-30% of these patients from getting unnecessary prophylaxis" with an anticoagulant, said Dr. Mahan, director of outcomes research at the New Mexico Heart Institute in Albuquerque.

He cautioned that the new evidence he presented still needs to be published, and a prospective test of the risk formula should also be done, but the new findings give this risk-scoring method a leg up over the several other risk-assessment methods that are out there.

"This gives us some information that we can comfortably use," Dr. Mahan said in an interview. Other formulas for estimating VTE risk in patients hospitalized for medical reasons include the Padua Prediction Score (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2450-7), but the RAM tested by Dr. Mahan now "has the best evidence base for hospitalized, acutely ill patients."

The validation used the risk formula developed by the IMPROVE (International Medical Prevention Registry in Venous Thromboembolism) study, which included more than 15,000 medical patients seen at 52 hospitals in 12 countries (Chest 2011;140:705-14).

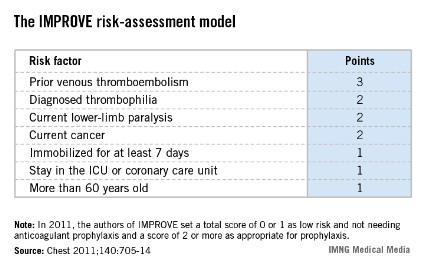

The IMPROVE RAM includes seven risk factors that each score from 1 to 3 points (see box). A history of VTE scores 3 points; immobilization for a week or more, intensive care unit stay, and age over 60 each score 1 point; and three other factors each score 2 points.

The validation cohort came from the more than 130,000 patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized for at least 3 days during 2005-2011 at a McMaster University–affiliated hospital in Hamilton, Ont. After excluding pregnancies, patients with recent surgery, and patients with VTE at the time of admission, the investigators identified 139 patients who developed VTE within 90 days of hospital admission and matched them with 278 patients who did not develop a VTE as controls. Matching was by gender, hospital, and date of admission.

The IMPROVE RAM showed "good" discrimination in the validation cohort, Dr. Mahan reported. The incidence of VTE during the 90 days following hospitalization in the validation cohort was 0.20% in patients with low scores, 0 or 1; 1.04% in patients with moderate scores, 2 or 3; and 4.15% in those with high scores, 4 or greater. By comparison, in the first IMPROVE cohort the VTE rates for 90 days were 0.45% in patients with low scores, 1.30% in those with moderate scores, and 4.74% in those with high scores.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve analysis showed that in the new cohort, the IMPROVE formula could account for about 77% of the variability in VTE incidence, performance that was also similar to that of the derivation cohort. But the formula failed to predict a VTE in several patients: 26 patients (19%) who had a VTE during follow-up had an IMPROVE score of 0 or 1 at the time of their hospitalization.

In 2011, the IMPROVE authors suggested that clinicians apply VTE prophylaxis to patients who scored 2 points or higher on the risk formula, which represented 31% of the more than 15,000 patients in the derivation cohort. In the validation cohort, 37% of the patients had a score of 2 or more. The new data suggest that a score of 3 or more may be an even better cutoff for starting VTE prophylaxis with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Mahan said, but he added that this needs more analysis.

The new data showed that a score cut-point of 2 had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 60%, whereas a cut-point of 3 had a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 78%.

"We’re still working on the cut-point. I’m sure that a score of 0 or 1 needs no prophylaxis," but deciding between 2 and 3 points will take more time, he said. "In the United States especially, we are over-prophylaxing," giving anticoagulant prophylaxis to "a large group of U.S. hospital patients who don’t need it. Some hospitals do blanket prophylaxis" for virtually all patients hospitalized for medical reasons, Dr. Mahan said.

"We want to identify patients who are not at risk so they don’t get prophylaxis."

Dr. Mahan said that he has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

[email protected] On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This research addresses quality, safety, and cost for our patients in hospital medicine. We have recognized that not all inpatients require VTE prevention, and this work offers a validated approach to assist with appropriate prophylaxis.

|

| Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig |

It will be important to see if this can be incorporated into our workflow via electronic health records. This is exactly where we need assistance to prevent one of the leading causes of death in our hospitalized patients in a cost-effective manner.

We still need to better define the risk score, but this is definitely an advance.

Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig is chair of the department of hospital medicine, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

This research addresses quality, safety, and cost for our patients in hospital medicine. We have recognized that not all inpatients require VTE prevention, and this work offers a validated approach to assist with appropriate prophylaxis.

|

| Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig |

It will be important to see if this can be incorporated into our workflow via electronic health records. This is exactly where we need assistance to prevent one of the leading causes of death in our hospitalized patients in a cost-effective manner.

We still need to better define the risk score, but this is definitely an advance.

Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig is chair of the department of hospital medicine, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

This research addresses quality, safety, and cost for our patients in hospital medicine. We have recognized that not all inpatients require VTE prevention, and this work offers a validated approach to assist with appropriate prophylaxis.

|

| Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig |

It will be important to see if this can be incorporated into our workflow via electronic health records. This is exactly where we need assistance to prevent one of the leading causes of death in our hospitalized patients in a cost-effective manner.

We still need to better define the risk score, but this is definitely an advance.

Dr. Steven B. Deitelzweig is chair of the department of hospital medicine, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

AMSTERDAM – A simple formula for calculating the risk faced by acutely ill, hospitalized patients for venous thromboembolism was validated in a case-control study with more than 400 patients.

This VTE risk-calculator formula "is the first [risk-assessment model (RAM)] to be validated on a large scale in hospitalized medical patients," Charles E. Mahan, Pharm.D., said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"Applying this RAM could spare 20%-30% of these patients from getting unnecessary prophylaxis" with an anticoagulant, said Dr. Mahan, director of outcomes research at the New Mexico Heart Institute in Albuquerque.

He cautioned that the new evidence he presented still needs to be published, and a prospective test of the risk formula should also be done, but the new findings give this risk-scoring method a leg up over the several other risk-assessment methods that are out there.

"This gives us some information that we can comfortably use," Dr. Mahan said in an interview. Other formulas for estimating VTE risk in patients hospitalized for medical reasons include the Padua Prediction Score (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2450-7), but the RAM tested by Dr. Mahan now "has the best evidence base for hospitalized, acutely ill patients."

The validation used the risk formula developed by the IMPROVE (International Medical Prevention Registry in Venous Thromboembolism) study, which included more than 15,000 medical patients seen at 52 hospitals in 12 countries (Chest 2011;140:705-14).

The IMPROVE RAM includes seven risk factors that each score from 1 to 3 points (see box). A history of VTE scores 3 points; immobilization for a week or more, intensive care unit stay, and age over 60 each score 1 point; and three other factors each score 2 points.

The validation cohort came from the more than 130,000 patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized for at least 3 days during 2005-2011 at a McMaster University–affiliated hospital in Hamilton, Ont. After excluding pregnancies, patients with recent surgery, and patients with VTE at the time of admission, the investigators identified 139 patients who developed VTE within 90 days of hospital admission and matched them with 278 patients who did not develop a VTE as controls. Matching was by gender, hospital, and date of admission.

The IMPROVE RAM showed "good" discrimination in the validation cohort, Dr. Mahan reported. The incidence of VTE during the 90 days following hospitalization in the validation cohort was 0.20% in patients with low scores, 0 or 1; 1.04% in patients with moderate scores, 2 or 3; and 4.15% in those with high scores, 4 or greater. By comparison, in the first IMPROVE cohort the VTE rates for 90 days were 0.45% in patients with low scores, 1.30% in those with moderate scores, and 4.74% in those with high scores.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve analysis showed that in the new cohort, the IMPROVE formula could account for about 77% of the variability in VTE incidence, performance that was also similar to that of the derivation cohort. But the formula failed to predict a VTE in several patients: 26 patients (19%) who had a VTE during follow-up had an IMPROVE score of 0 or 1 at the time of their hospitalization.

In 2011, the IMPROVE authors suggested that clinicians apply VTE prophylaxis to patients who scored 2 points or higher on the risk formula, which represented 31% of the more than 15,000 patients in the derivation cohort. In the validation cohort, 37% of the patients had a score of 2 or more. The new data suggest that a score of 3 or more may be an even better cutoff for starting VTE prophylaxis with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Mahan said, but he added that this needs more analysis.

The new data showed that a score cut-point of 2 had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 60%, whereas a cut-point of 3 had a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 78%.

"We’re still working on the cut-point. I’m sure that a score of 0 or 1 needs no prophylaxis," but deciding between 2 and 3 points will take more time, he said. "In the United States especially, we are over-prophylaxing," giving anticoagulant prophylaxis to "a large group of U.S. hospital patients who don’t need it. Some hospitals do blanket prophylaxis" for virtually all patients hospitalized for medical reasons, Dr. Mahan said.

"We want to identify patients who are not at risk so they don’t get prophylaxis."

Dr. Mahan said that he has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

[email protected] On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – A simple formula for calculating the risk faced by acutely ill, hospitalized patients for venous thromboembolism was validated in a case-control study with more than 400 patients.

This VTE risk-calculator formula "is the first [risk-assessment model (RAM)] to be validated on a large scale in hospitalized medical patients," Charles E. Mahan, Pharm.D., said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"Applying this RAM could spare 20%-30% of these patients from getting unnecessary prophylaxis" with an anticoagulant, said Dr. Mahan, director of outcomes research at the New Mexico Heart Institute in Albuquerque.

He cautioned that the new evidence he presented still needs to be published, and a prospective test of the risk formula should also be done, but the new findings give this risk-scoring method a leg up over the several other risk-assessment methods that are out there.

"This gives us some information that we can comfortably use," Dr. Mahan said in an interview. Other formulas for estimating VTE risk in patients hospitalized for medical reasons include the Padua Prediction Score (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2450-7), but the RAM tested by Dr. Mahan now "has the best evidence base for hospitalized, acutely ill patients."

The validation used the risk formula developed by the IMPROVE (International Medical Prevention Registry in Venous Thromboembolism) study, which included more than 15,000 medical patients seen at 52 hospitals in 12 countries (Chest 2011;140:705-14).

The IMPROVE RAM includes seven risk factors that each score from 1 to 3 points (see box). A history of VTE scores 3 points; immobilization for a week or more, intensive care unit stay, and age over 60 each score 1 point; and three other factors each score 2 points.

The validation cohort came from the more than 130,000 patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized for at least 3 days during 2005-2011 at a McMaster University–affiliated hospital in Hamilton, Ont. After excluding pregnancies, patients with recent surgery, and patients with VTE at the time of admission, the investigators identified 139 patients who developed VTE within 90 days of hospital admission and matched them with 278 patients who did not develop a VTE as controls. Matching was by gender, hospital, and date of admission.

The IMPROVE RAM showed "good" discrimination in the validation cohort, Dr. Mahan reported. The incidence of VTE during the 90 days following hospitalization in the validation cohort was 0.20% in patients with low scores, 0 or 1; 1.04% in patients with moderate scores, 2 or 3; and 4.15% in those with high scores, 4 or greater. By comparison, in the first IMPROVE cohort the VTE rates for 90 days were 0.45% in patients with low scores, 1.30% in those with moderate scores, and 4.74% in those with high scores.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve analysis showed that in the new cohort, the IMPROVE formula could account for about 77% of the variability in VTE incidence, performance that was also similar to that of the derivation cohort. But the formula failed to predict a VTE in several patients: 26 patients (19%) who had a VTE during follow-up had an IMPROVE score of 0 or 1 at the time of their hospitalization.

In 2011, the IMPROVE authors suggested that clinicians apply VTE prophylaxis to patients who scored 2 points or higher on the risk formula, which represented 31% of the more than 15,000 patients in the derivation cohort. In the validation cohort, 37% of the patients had a score of 2 or more. The new data suggest that a score of 3 or more may be an even better cutoff for starting VTE prophylaxis with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Mahan said, but he added that this needs more analysis.

The new data showed that a score cut-point of 2 had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 60%, whereas a cut-point of 3 had a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 78%.

"We’re still working on the cut-point. I’m sure that a score of 0 or 1 needs no prophylaxis," but deciding between 2 and 3 points will take more time, he said. "In the United States especially, we are over-prophylaxing," giving anticoagulant prophylaxis to "a large group of U.S. hospital patients who don’t need it. Some hospitals do blanket prophylaxis" for virtually all patients hospitalized for medical reasons, Dr. Mahan said.

"We want to identify patients who are not at risk so they don’t get prophylaxis."

Dr. Mahan said that he has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

[email protected] On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE 2013 ISTH CONGRESS