User login

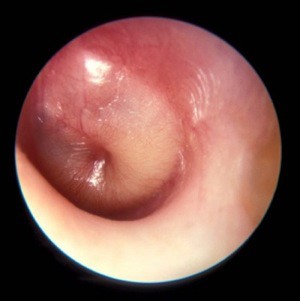

A new, more stringent definition of acute otitis media that focuses on tympanic membrane appearance on otoscopy and downplays the diagnostic role of symptoms highlighted the new acute otitis media diagnosis and management guidelines released by the American Academy of Pediatrics on Feb. 25.

The new guidelines, the first revision since 2004, also reaffirmed and expanded the option of observation without treatment for selected children with acute otitis media (AOM) as an alternative to immediate prescription of an antibiotic. Introduction of observation as a viable alternative to antibiotics had been the major feature of the 2004 guidelines.

"The most important change from 2004 is the working definition of AOM. The appearance of the tympanic membrane [TM] is the key to an accurate diagnosis," said Dr. Allan S. Lieberthal, a pediatrician with Kaiser-Permanente in Panorama City, Calif., who chairs the AAP subcommittee on diagnosis and management of acute otitis media, which wrote the new guidelines revision (Pediatrics 2013;131;e964-e99).

"Fever, fussiness, ear pain, or a combination may be the usual reason for a doctor visit, but research done in the last several years has shown that symptoms do not differentiate AOM from an upper respiratory infection or other minor illnesses. With the requirement of a bulging TM, there should no longer be uncertainty in diagnosis," Dr. Lieberthal said.

The guidelines also emphasize pneumatic otoscopy to ensure the presence of a middle-ear effusion, calling the pneumatic otoscope the "standard tool" for diagnosing otitis media. Despite that, "relatively few physicians consistently use pneumatic otoscopy, and they may be resistant to changing their practice," Dr. Lieberthal said in an interview.

The second major change of the new guidelines is expansion of the observation option to selected children aged 6-24 months if they have unilateral AOM without otorrhea and if the child’s parent or caregiver understands and agrees with the option. Children this young with bilateral AOM, severe symptoms, or otorrhea are not recommended as candidates for deferred treatment and observation. The new guidelines also reaffirmed the observation option first recommended in 2004 for selected children older than 2 years if they have either unilateral or bilateral AOM but without otorrhea or severe symptoms.

Recent research results "reinforced the success of observation, especially in children older than 24 months who are not severely ill," said Dr. Lieberthal. "In most studies, 70% of children treated with initial observation did not require subsequent antibiotic treatment."

The guidelines also stress two important caveats: The family should be included in decisions regarding the use of observation for initial therapy, and a mechanism must be in place to ensure follow-up so that an antibiotic regimen can start if the child worsens or fails to improve within 48-72 hours after symptom onset.

Results from "two major studies using a highly specific definition of AOM in younger children showed significant improvement in patients treated with antibiotics, compared with those who were observed. The panel acknowledged this by continuing to recommend initial antibiotic treatment in children younger than 24 months who have a bulging TM. However, if the bulging is minor and the child does not appear ill, then initial observation may be used if the family agrees, and if a mechanism is in place to ensure follow-up," he said.

"Due to widespread discussion [about the observation option] in consumer media after the 2004 guidelines, parents now often ask if observation is recommended, and a growing number of pediatricians use observation," Dr. Lieberthal said, adding that "family and emergency physicians have been more resistant" to applying the observation option.

The new guidelines made no change in the recommended antibiotic regimens, with amoxicillin the top choice and amoxicillin-clavulanate an alternative for either initial or delayed treatment. For children who fail to improve after 48-72 hours of treatment, the guidelines call for switching to amoxicillin-clavulanate or ceftriaxone. The guidelines also include recommended options for children with penicillin allergy.

The new guidelines also made no changes from the 2004 recommendations for pain management, with acetaminophen and ibuprofen flagged as the "mainstays" for treating AOM pain.

This year’s guidelines also include recommendations that physicians check that their patients are up to date on their pneumococcal conjugate and influenza vaccines, that mothers are encouraged to breastfeed their infants for at least 6 months, and that physicians encourage tobacco smoke avoidance.

The guidelines also address dealing with children who develop recurrent AOM, a topic not included in the 2004 version. Recurrent AOM is defined as three episodes in 6 months or four episodes in 1 year, with one episode in the preceding 6 months. The new guidelines specifically say that clinicians should not prescribe any prophylactic antibiotics but may offer tympanostomy tubes. "Many physicians no longer use prophylactic antibiotics," Dr. Lieberthal noted. "Hopefully, the guidelines will reduce the use of unnecessary tubes," he added.

The AAP first assembled the panel to update the AOM guidelines in 2009, and the members included general pediatricians, pediatric infectious diseases specialists, otolaryngologists, an emergency medicine physician, and a family physician. The panel worked with the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Southern California Evidence-Based Research Center for its literature review. The panel designed the guidelines for children aged 6 months to 12 years who are otherwise healthy, and they include 17 individual action statements for clinicians.

The guidelines also included statements about uptake of the 2004 guidelines: "Despite significant publicity and awareness of the 2004 AOM guideline evidence shows that clinicians are hesitant to follow the guidelines recommendations." The panel added that, "for clinical practice guidelines to be effective more must be done to improve their dissemination and implementation."

When asked about these statements, Dr. Lieberthal said, "Most physicians find it difficult to change their long-standing practices. The AAP is working on an education and implementation plan" for the 2013 revision.

The revised clinical practice guidelines for acute otitis media were sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Dr. Lieberthal said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Dr. Stephen I. Pelton* comments:

The guidelines address five important areas and provide update,

clarification, and greater granularity than the original guidelines did.

They emphasize the diagnostic criteria, and strengthen

the significance of bulging as a diagnostic requirement for AOM as well as the

requirement for the presence of middle ear effusion. This will be challenging

as many clinicians are not well trained in the use of pneumatic otoscopy. The

guidelines were not written to apply to infants younger than 6 months, and in

the youngest infants, tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may be less

accurate.

The initial approach remains assessment of the need

for antibiotic treatment based on age and severity, as well as assessment of

pain and appropriate management of pain. The choice between antibiotic

management and observation is further clarified in these guidelines based on

current evidence. The new guidelines discuss but do not highlight the results

of two recent randomized clinical trials that showed that half of the children

in the placebo group did not have a satisfactory resolution. Presumably, this

information should be included in any discussion with parents about the role

for antibiotics in treating young children with AOM. The criteria recommended

for the routine use of antibiotics in children less than 2 years old –

bilateral disease, acute otorrhea, or high fever – all are supported by

evidence.

The choice of amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate

as the first-line antibiotics is appropriate. The lack of any recommendation

for azithromycin will hopefully help educate clinicians about its limited

activity against Haemophilus in children with culture-positive AOM and

the significant prevalence of macrolide-resistant pneumococci in the community.

The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine has proven

beneficial, both for preventing AOM and recurrent AOM, and for obviating

tympanostomy tube insertion. It is important that the vaccine be administered

early in life, before recurrent AOM can develop. Influenza vaccine also is

valuable during influenza seasons for preventing flu and its AOM complication.

Although the guidelines take an absolute approach

against antibiotic prophylaxis, there may be some specific children where it

may still have value despite concerns about promoting resistance through

selective pressure.

Dr. Stephen I. Pelton is chief of pediatric

infectious disease and also is the coordinator of the maternal-child HIV

program at Boston

Medical Center.

He was not involved in development of the AAP guidelines and responded to a

request to comment on the guidelines.

Updated: 3/4/13 Dr. Pelton's misspelled first name corrected

Dr. Stephen I. Pelton* comments:

The guidelines address five important areas and provide update,

clarification, and greater granularity than the original guidelines did.

They emphasize the diagnostic criteria, and strengthen

the significance of bulging as a diagnostic requirement for AOM as well as the

requirement for the presence of middle ear effusion. This will be challenging

as many clinicians are not well trained in the use of pneumatic otoscopy. The

guidelines were not written to apply to infants younger than 6 months, and in

the youngest infants, tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may be less

accurate.

The initial approach remains assessment of the need

for antibiotic treatment based on age and severity, as well as assessment of

pain and appropriate management of pain. The choice between antibiotic

management and observation is further clarified in these guidelines based on

current evidence. The new guidelines discuss but do not highlight the results

of two recent randomized clinical trials that showed that half of the children

in the placebo group did not have a satisfactory resolution. Presumably, this

information should be included in any discussion with parents about the role

for antibiotics in treating young children with AOM. The criteria recommended

for the routine use of antibiotics in children less than 2 years old –

bilateral disease, acute otorrhea, or high fever – all are supported by

evidence.

The choice of amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate

as the first-line antibiotics is appropriate. The lack of any recommendation

for azithromycin will hopefully help educate clinicians about its limited

activity against Haemophilus in children with culture-positive AOM and

the significant prevalence of macrolide-resistant pneumococci in the community.

The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine has proven

beneficial, both for preventing AOM and recurrent AOM, and for obviating

tympanostomy tube insertion. It is important that the vaccine be administered

early in life, before recurrent AOM can develop. Influenza vaccine also is

valuable during influenza seasons for preventing flu and its AOM complication.

Although the guidelines take an absolute approach

against antibiotic prophylaxis, there may be some specific children where it

may still have value despite concerns about promoting resistance through

selective pressure.

Dr. Stephen I. Pelton is chief of pediatric

infectious disease and also is the coordinator of the maternal-child HIV

program at Boston

Medical Center.

He was not involved in development of the AAP guidelines and responded to a

request to comment on the guidelines.

Updated: 3/4/13 Dr. Pelton's misspelled first name corrected

Dr. Stephen I. Pelton* comments:

The guidelines address five important areas and provide update,

clarification, and greater granularity than the original guidelines did.

They emphasize the diagnostic criteria, and strengthen

the significance of bulging as a diagnostic requirement for AOM as well as the

requirement for the presence of middle ear effusion. This will be challenging

as many clinicians are not well trained in the use of pneumatic otoscopy. The

guidelines were not written to apply to infants younger than 6 months, and in

the youngest infants, tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may be less

accurate.

The initial approach remains assessment of the need

for antibiotic treatment based on age and severity, as well as assessment of

pain and appropriate management of pain. The choice between antibiotic

management and observation is further clarified in these guidelines based on

current evidence. The new guidelines discuss but do not highlight the results

of two recent randomized clinical trials that showed that half of the children

in the placebo group did not have a satisfactory resolution. Presumably, this

information should be included in any discussion with parents about the role

for antibiotics in treating young children with AOM. The criteria recommended

for the routine use of antibiotics in children less than 2 years old –

bilateral disease, acute otorrhea, or high fever – all are supported by

evidence.

The choice of amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate

as the first-line antibiotics is appropriate. The lack of any recommendation

for azithromycin will hopefully help educate clinicians about its limited

activity against Haemophilus in children with culture-positive AOM and

the significant prevalence of macrolide-resistant pneumococci in the community.

The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine has proven

beneficial, both for preventing AOM and recurrent AOM, and for obviating

tympanostomy tube insertion. It is important that the vaccine be administered

early in life, before recurrent AOM can develop. Influenza vaccine also is

valuable during influenza seasons for preventing flu and its AOM complication.

Although the guidelines take an absolute approach

against antibiotic prophylaxis, there may be some specific children where it

may still have value despite concerns about promoting resistance through

selective pressure.

Dr. Stephen I. Pelton is chief of pediatric

infectious disease and also is the coordinator of the maternal-child HIV

program at Boston

Medical Center.

He was not involved in development of the AAP guidelines and responded to a

request to comment on the guidelines.

Updated: 3/4/13 Dr. Pelton's misspelled first name corrected

A new, more stringent definition of acute otitis media that focuses on tympanic membrane appearance on otoscopy and downplays the diagnostic role of symptoms highlighted the new acute otitis media diagnosis and management guidelines released by the American Academy of Pediatrics on Feb. 25.

The new guidelines, the first revision since 2004, also reaffirmed and expanded the option of observation without treatment for selected children with acute otitis media (AOM) as an alternative to immediate prescription of an antibiotic. Introduction of observation as a viable alternative to antibiotics had been the major feature of the 2004 guidelines.

"The most important change from 2004 is the working definition of AOM. The appearance of the tympanic membrane [TM] is the key to an accurate diagnosis," said Dr. Allan S. Lieberthal, a pediatrician with Kaiser-Permanente in Panorama City, Calif., who chairs the AAP subcommittee on diagnosis and management of acute otitis media, which wrote the new guidelines revision (Pediatrics 2013;131;e964-e99).

"Fever, fussiness, ear pain, or a combination may be the usual reason for a doctor visit, but research done in the last several years has shown that symptoms do not differentiate AOM from an upper respiratory infection or other minor illnesses. With the requirement of a bulging TM, there should no longer be uncertainty in diagnosis," Dr. Lieberthal said.

The guidelines also emphasize pneumatic otoscopy to ensure the presence of a middle-ear effusion, calling the pneumatic otoscope the "standard tool" for diagnosing otitis media. Despite that, "relatively few physicians consistently use pneumatic otoscopy, and they may be resistant to changing their practice," Dr. Lieberthal said in an interview.

The second major change of the new guidelines is expansion of the observation option to selected children aged 6-24 months if they have unilateral AOM without otorrhea and if the child’s parent or caregiver understands and agrees with the option. Children this young with bilateral AOM, severe symptoms, or otorrhea are not recommended as candidates for deferred treatment and observation. The new guidelines also reaffirmed the observation option first recommended in 2004 for selected children older than 2 years if they have either unilateral or bilateral AOM but without otorrhea or severe symptoms.

Recent research results "reinforced the success of observation, especially in children older than 24 months who are not severely ill," said Dr. Lieberthal. "In most studies, 70% of children treated with initial observation did not require subsequent antibiotic treatment."

The guidelines also stress two important caveats: The family should be included in decisions regarding the use of observation for initial therapy, and a mechanism must be in place to ensure follow-up so that an antibiotic regimen can start if the child worsens or fails to improve within 48-72 hours after symptom onset.

Results from "two major studies using a highly specific definition of AOM in younger children showed significant improvement in patients treated with antibiotics, compared with those who were observed. The panel acknowledged this by continuing to recommend initial antibiotic treatment in children younger than 24 months who have a bulging TM. However, if the bulging is minor and the child does not appear ill, then initial observation may be used if the family agrees, and if a mechanism is in place to ensure follow-up," he said.

"Due to widespread discussion [about the observation option] in consumer media after the 2004 guidelines, parents now often ask if observation is recommended, and a growing number of pediatricians use observation," Dr. Lieberthal said, adding that "family and emergency physicians have been more resistant" to applying the observation option.

The new guidelines made no change in the recommended antibiotic regimens, with amoxicillin the top choice and amoxicillin-clavulanate an alternative for either initial or delayed treatment. For children who fail to improve after 48-72 hours of treatment, the guidelines call for switching to amoxicillin-clavulanate or ceftriaxone. The guidelines also include recommended options for children with penicillin allergy.

The new guidelines also made no changes from the 2004 recommendations for pain management, with acetaminophen and ibuprofen flagged as the "mainstays" for treating AOM pain.

This year’s guidelines also include recommendations that physicians check that their patients are up to date on their pneumococcal conjugate and influenza vaccines, that mothers are encouraged to breastfeed their infants for at least 6 months, and that physicians encourage tobacco smoke avoidance.

The guidelines also address dealing with children who develop recurrent AOM, a topic not included in the 2004 version. Recurrent AOM is defined as three episodes in 6 months or four episodes in 1 year, with one episode in the preceding 6 months. The new guidelines specifically say that clinicians should not prescribe any prophylactic antibiotics but may offer tympanostomy tubes. "Many physicians no longer use prophylactic antibiotics," Dr. Lieberthal noted. "Hopefully, the guidelines will reduce the use of unnecessary tubes," he added.

The AAP first assembled the panel to update the AOM guidelines in 2009, and the members included general pediatricians, pediatric infectious diseases specialists, otolaryngologists, an emergency medicine physician, and a family physician. The panel worked with the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Southern California Evidence-Based Research Center for its literature review. The panel designed the guidelines for children aged 6 months to 12 years who are otherwise healthy, and they include 17 individual action statements for clinicians.

The guidelines also included statements about uptake of the 2004 guidelines: "Despite significant publicity and awareness of the 2004 AOM guideline evidence shows that clinicians are hesitant to follow the guidelines recommendations." The panel added that, "for clinical practice guidelines to be effective more must be done to improve their dissemination and implementation."

When asked about these statements, Dr. Lieberthal said, "Most physicians find it difficult to change their long-standing practices. The AAP is working on an education and implementation plan" for the 2013 revision.

The revised clinical practice guidelines for acute otitis media were sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Dr. Lieberthal said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A new, more stringent definition of acute otitis media that focuses on tympanic membrane appearance on otoscopy and downplays the diagnostic role of symptoms highlighted the new acute otitis media diagnosis and management guidelines released by the American Academy of Pediatrics on Feb. 25.

The new guidelines, the first revision since 2004, also reaffirmed and expanded the option of observation without treatment for selected children with acute otitis media (AOM) as an alternative to immediate prescription of an antibiotic. Introduction of observation as a viable alternative to antibiotics had been the major feature of the 2004 guidelines.

"The most important change from 2004 is the working definition of AOM. The appearance of the tympanic membrane [TM] is the key to an accurate diagnosis," said Dr. Allan S. Lieberthal, a pediatrician with Kaiser-Permanente in Panorama City, Calif., who chairs the AAP subcommittee on diagnosis and management of acute otitis media, which wrote the new guidelines revision (Pediatrics 2013;131;e964-e99).

"Fever, fussiness, ear pain, or a combination may be the usual reason for a doctor visit, but research done in the last several years has shown that symptoms do not differentiate AOM from an upper respiratory infection or other minor illnesses. With the requirement of a bulging TM, there should no longer be uncertainty in diagnosis," Dr. Lieberthal said.

The guidelines also emphasize pneumatic otoscopy to ensure the presence of a middle-ear effusion, calling the pneumatic otoscope the "standard tool" for diagnosing otitis media. Despite that, "relatively few physicians consistently use pneumatic otoscopy, and they may be resistant to changing their practice," Dr. Lieberthal said in an interview.

The second major change of the new guidelines is expansion of the observation option to selected children aged 6-24 months if they have unilateral AOM without otorrhea and if the child’s parent or caregiver understands and agrees with the option. Children this young with bilateral AOM, severe symptoms, or otorrhea are not recommended as candidates for deferred treatment and observation. The new guidelines also reaffirmed the observation option first recommended in 2004 for selected children older than 2 years if they have either unilateral or bilateral AOM but without otorrhea or severe symptoms.

Recent research results "reinforced the success of observation, especially in children older than 24 months who are not severely ill," said Dr. Lieberthal. "In most studies, 70% of children treated with initial observation did not require subsequent antibiotic treatment."

The guidelines also stress two important caveats: The family should be included in decisions regarding the use of observation for initial therapy, and a mechanism must be in place to ensure follow-up so that an antibiotic regimen can start if the child worsens or fails to improve within 48-72 hours after symptom onset.

Results from "two major studies using a highly specific definition of AOM in younger children showed significant improvement in patients treated with antibiotics, compared with those who were observed. The panel acknowledged this by continuing to recommend initial antibiotic treatment in children younger than 24 months who have a bulging TM. However, if the bulging is minor and the child does not appear ill, then initial observation may be used if the family agrees, and if a mechanism is in place to ensure follow-up," he said.

"Due to widespread discussion [about the observation option] in consumer media after the 2004 guidelines, parents now often ask if observation is recommended, and a growing number of pediatricians use observation," Dr. Lieberthal said, adding that "family and emergency physicians have been more resistant" to applying the observation option.

The new guidelines made no change in the recommended antibiotic regimens, with amoxicillin the top choice and amoxicillin-clavulanate an alternative for either initial or delayed treatment. For children who fail to improve after 48-72 hours of treatment, the guidelines call for switching to amoxicillin-clavulanate or ceftriaxone. The guidelines also include recommended options for children with penicillin allergy.

The new guidelines also made no changes from the 2004 recommendations for pain management, with acetaminophen and ibuprofen flagged as the "mainstays" for treating AOM pain.

This year’s guidelines also include recommendations that physicians check that their patients are up to date on their pneumococcal conjugate and influenza vaccines, that mothers are encouraged to breastfeed their infants for at least 6 months, and that physicians encourage tobacco smoke avoidance.

The guidelines also address dealing with children who develop recurrent AOM, a topic not included in the 2004 version. Recurrent AOM is defined as three episodes in 6 months or four episodes in 1 year, with one episode in the preceding 6 months. The new guidelines specifically say that clinicians should not prescribe any prophylactic antibiotics but may offer tympanostomy tubes. "Many physicians no longer use prophylactic antibiotics," Dr. Lieberthal noted. "Hopefully, the guidelines will reduce the use of unnecessary tubes," he added.

The AAP first assembled the panel to update the AOM guidelines in 2009, and the members included general pediatricians, pediatric infectious diseases specialists, otolaryngologists, an emergency medicine physician, and a family physician. The panel worked with the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Southern California Evidence-Based Research Center for its literature review. The panel designed the guidelines for children aged 6 months to 12 years who are otherwise healthy, and they include 17 individual action statements for clinicians.

The guidelines also included statements about uptake of the 2004 guidelines: "Despite significant publicity and awareness of the 2004 AOM guideline evidence shows that clinicians are hesitant to follow the guidelines recommendations." The panel added that, "for clinical practice guidelines to be effective more must be done to improve their dissemination and implementation."

When asked about these statements, Dr. Lieberthal said, "Most physicians find it difficult to change their long-standing practices. The AAP is working on an education and implementation plan" for the 2013 revision.

The revised clinical practice guidelines for acute otitis media were sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Dr. Lieberthal said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

FROM PEDIATRICS