User login

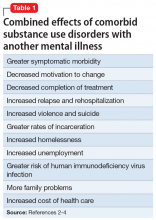

The term “dual diagnosis” describes the clinically challenging comorbidity of a substance use disorder (SUD) along with another major mental illness. Based on data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, the lifetime prevalence of SUDs among patients with mental illness is approximately 30%, and is higher among patients with certain mental disorders, such as schizophrenia (47%), bipolar disorder (61%), and antisocial personality disorder (84%).1 These statistics highlight that addiction is often the rule rather than the exception among those with severe mental illness.1 Not surprisingly, the combined effects of having an SUD along with another mental illness are uniformly negative (Table 12-4).

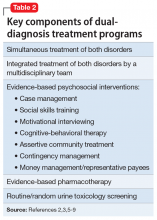

Based on outcomes research, the core tenets of evidence-based dual-diagnosis treatment include the importance of integrated (rather than parallel) and simultaneous (rather than sequential) care, which means an ideal treatment program includes a unified, multidisciplinary team whose coordinated efforts focus on treating both disorders concurrently.2 Evidence-based psychotherapies for addiction, including motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relapse prevention, contingency management, skills training, and/or case management, are a necessity,3,5 and must be balanced with rational and appropriate pharmacotherapy targeting both the SUD as well as the other disorder (Table 22,3,5-9).

3 ‘Real-world’ clinical challenges

Ideal vs real-world treatment

Treating patients with co-occurring disorders (CODs) within integrated dual-disorder treatment (IDDT) programs sounds straightforward. However, implementing evidence-based “best practice” treatment is a significant challenge in the real world for several reasons. First, individuals with CODs often struggle with poor insight, low motivation to change, and lack of access to health care. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 52% of individuals with CODs in the U.S. received no treatment at all in 2016.10 For patients with dual disorders who do seek care, most are not given access to specialty SUD treatment10 and may instead find themselves treated by psychiatrists with limited SUD training who fail to provide evidence-based psychotherapies and underutilize pharmacotherapies for SUDs.11 In the setting of CODs, the “harm reduction model” can be conflated with therapeutic nihilism, resulting in the neglect of SUD issues, with clinicians expecting patients to seek SUD treatment on their own, through self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous or in other community treatment programs staffed by nonprofessionals that often are not tailored to the unique needs of patients with dual disorders. Psychiatrists working with other mental health professionals who provide psychotherapy for SUDs often do so in parallel rather than in an evidence-based, integrated fashion.

IDDT programs are not widely available. One study found that fewer than 20% of addiction treatment programs and fewer than 10% of mental health programs in the U.S. met criteria for dual diagnosis–capable services.12 Getting treatment programs to become dual diagnosis–capable is possible, but it is a time-consuming and costly endeavor that, once achieved, requires continuous staff training and programmatic adaptations to interruptions in funding.13-16 With myriad barriers to the establishment and maintenance of IDDTs, many patients with dual disorders are left without access to the most effective and comprehensive care; as few as 4% of individuals with CODs are treated within integrated programs.17

Diagnostic dilemmas

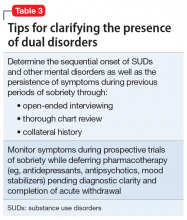

Establishing whether or not a patient with an active SUD has another serious mental illness (SMI) is a crucial first step for optimizing treatment, but diagnostic reliability can prove challenging and requires careful clinical assessment (Table 3). As always in psychiatry, accurate diagnosis is limited to careful clinical assessment18 and, in the case of possible dual disorders, is complicated by the fact that both SUDs as well as non-SUDs can result in the same psychiatric symptoms (eg, insomnia, anxiety, depression, manic behaviors, and psychosis). Clinicians must therefore distinguish between:

- Symptoms of substance intoxication or withdrawal vs independent symptoms of an underlying psychiatric disorder (that persist beyond a month after cessation of intoxication or withdrawal)

- Subclinical symptoms vs threshold mental illness, keeping in mind that some mood and anxiety states can be normal given social situations and stressors (eg, turmoil in relationships, employment difficulties, homelessness, etc.)

- Any mental illness (AMI) vs SMI. The latter is defined by SAMHSA as AMI that substantially interferes with or limits ≥1 major life activities.10

With these distinctions in mind, data from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that dual-diagnosis comorbidity was higher when the threshold for mental illness was lower—among the 19 million adults in the U.S. with SUDs, the past-year prevalence was 43% for AMI and 14% for SMI.10 Looking at substance-induced disorders vs “independent” disorders, the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found that for individuals with SUDs, the past-year prevalence of an independent mood or anxiety disorder was 35% and 26%, respectively.19 Taken together, these findings illustrate the substantial rate of dual-diagnosis comorbidity, the diagnostic heterogeneity and range of severity of CODs,20 and the potential for both false negatives (eg, diagnosing a substance-induced syndrome when in fact a patient has an underlying disorder) and false positives (diagnosing a full-blown mental illness when symptoms are subclinical or substance-induced) when performing diagnostic assessments in the setting of known SUDs.

Continue to: False positives are more likely...

False positives are more likely when patients seeking treatment for non-SUDs don’t disclose active drug use, even when asked. Both patients and their treating clinicians may also be prone to underestimating the significant potential for morbidity associated with SUDs, such that substance-induced symptoms may be misattributed to a dual disorder. Diagnostic questioning and thorough chart review that includes careful assessment of whether psychiatric symptoms preceded the onset of substance use, and whether they persisted in the setting of extended sobriety, is therefore paramount for minimizing false positives when assessing for dual diagnoses.18,21 Likewise, random urine toxicology testing can be invaluable in verifying claims regarding sobriety.

Another factor that can complicate diagnosis is that there are often considerable secondary gains (eg, disability income, hospitalization, housing, access to prescription medications, and mitigation of the blame and stigma associated with addiction) associated with having a dual disorder as opposed to having “just” a SUD. As a result, for some patients, obtaining a non-SUD diagnosis can be highly incentivized.22,23 Clinicians must therefore be savvy about the high potential for malingering, embellishment, and mislabeling of symptoms when conducting diagnostic interviews. For example, in assessing for psychosis, the frequent endorsement of “hearing voices” in patients with SUDs often results in a diagnosis of schizophrenia or unspecified psychotic disorder,22 despite the fact that this symptom can occur during substance intoxication and withdrawal, is well documented among people without mental illness as well as those with non-psychotic disorders,24 and can resolve without medications or with non-antipsychotic pharmacotherapy.25

When assessing for dual disorders, diagnostic false positives and false negatives can both contribute to inappropriate treatment and unrealistic expectations for recovery, and therefore underscore the importance of careful diagnostic assessment. Even with diligent assessment, however, diagnostic clarity can prove elusive due to inadequate sobriety, inconsistent reporting, and poor memory.26 Therefore, for patients with known SUDs but diagnostic uncertainty about a dual disorder, the work-up should include a trial of prospective observation, with completion of appropriate detoxification, throughout a 1-month period of sobriety and in the absence of psychiatric medications, to determine if there are persistent symptoms that would justify a dual diagnosis. In research settings, such observations have revealed that most of depressive symptoms among alcoholics who present for substance abuse treatment resolve after a month of abstinence.27 A similar time course for resolution has been noted for anxiety, distress, fatigue, and depressive symptoms among individuals with cocaine dependence.28 These findings support the guideline established in DSM-IV that symptoms persisting beyond a month of sobriety “should be considered to be manifestations of an independent, non-substance-induced mental disorder,”29 while symptoms occurring within that month may well be substance-induced. Unfortunately, in real-world clinical practice, and particularly in outpatient settings, it can be quite difficult to achieve the requisite period of sobriety for reliable diagnosis, and patients are often prematurely prescribed medications (eg, an antidepressant, antipsychotic, or mood stabilizer) that can confound the cause of symptomatic resolution. Such prescriptions are driven by compelling pressures from patients to relieve their acute suffering, as well as the predilection of some clinicians to give patients “the benefit of doubt” in assessing for dual diagnoses. However, whether an inappropriate diagnosis or a prescription for an unnecessary medication represents a benefit is debatable at best.

Pharmacotherapy

A third real-world challenge in managing patients with dual disorders involves optimizing pharmacotherapy. Unfortunately, because patients with SUDs often are excluded from clinical trials, evidence-based guidance for patients with dual disorders is lacking. In addition, medications for both CODs often remain inaccessible to patients with dual disorders for 3 reasons:

- SUDs negatively impact medication adherence among patients with dual disorders, who sometimes point out that “it says right here on the bottle not to take this medication with drugs or alcohol!”

- Some self-help groups still espouse blanket opposition of any “psychotropic” medications, even when clearly indicated for patients with COD. Groups that recognize the importance of pharmacotherapy, such as Dual Diagnosis Anonymous (DDA), have emerged, but are not yet widely available.30

- Although there are increasing options for FDA-approved medications for SUDs, they are limited to the treatment of alcohol, opioid, and nicotine use disorders31; are often restricted due to hospital and health insurance formularies32; and remain underprescribed for patients with dual disorders.11

Continue to: Although underutilization of pharmacotherapy is...

Although underutilization of pharmacotherapy is a pitfall to be avoided in the treatment of patients with dual disorders, medication overutilization can be just as problematic. Patients with dual disorders are sometimes singularly focused on resolving acute anxiety, depression, or psychosis at the expense of working towards sobriety.33 Although the “self-medication hypothesis” is frequently invoked by patients and clinicians alike to suggest that substance use occurs in the service of “treating” underlying disorders,34 this theory has not been well supported in studies.35-37 Some patients may pledge dedication to abstinence, but still pressure physicians for a pharmacologic solution to their suffering. With expanding legalization of cannabis for both recreational and medical purposes, patients are increasingly seeking doctors’ recommendations for “medical marijuana” for a wide range of complaints, despite the fact that data supporting a therapeutic role for cannabis in the treatment of mental illness is sparse,38 whereas the potential harm in terms of either causing or worsening psychosis is well established.39,40 Clinicians must be knowledgeable about the abuse potential of prescribed medications, ranging from sleep aids, analgesics, and muscle relaxants to antidepressants and antipsychotics, while also being mindful of the psychological meaningfulness of seeking, prescribing, and not prescribing medications.41

Although the simultaneous treatment of patients with dual disorders that includes pharmacotherapy for both SUDs and CODs is vital for optimizing clinical outcomes, clinicians should strive for diagnostic accuracy and use medications judiciously. In addition, although pharmacotherapy often is necessary to deliver evidence-based treatment for patients with dual disorders, it is inadequate as standalone treatment and should be administered along with psychosocial interventions within an integrated, multidisciplinary treatment setting.

The keys to optimal outcomes

The treatment of patients with dual disorders can be challenging, to say the least. Ideal, evidence-based therapy in the form of an IDDT program can be difficult for clinicians to implement and for patients to access. Best efforts to perform meticulous clinical assessment to clarify diagnoses, use pharmacotherapy judiciously, work collaboratively in a multidisciplinary setting, and optimize treatment given available resources are keys to clinical success.

Bottom Line

Ideal treatment of patients with dual disorders consists of simultaneous, integrated interventions delivered by a multidisciplinary team. However, in the real world, limited resources, diagnostic challenges, and both over- and underutilization of pharmacotherapy often hamper optimal treatment.

Related Resources

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Co-occurring disorders. https://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/co-occurring.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. Dual diagnosis. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Related-Conditions/Dual-Diagnosis.

- Foundations Recovery Network. Dual diagnosis support groups. http://www.dualdiagnosis.org/resource/ddrn/self-helpsupport-groups/support-groups.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders evidence-based practices (EBP) KIT. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Integrated-Treatment-for-Co-Occurring-Disorders-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA08-4367.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA13-3992/SMA13-3992.pdf.

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2511-2518.

2. Drake RE, Mercer-McFadden C, Muesner KT, et al. Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(4):589-608.

3. Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE, et al. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): a review of empiric evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17(1):24-34.

4. Krawczyk N, Feder KA, Saloner B, et al. The association of psychiatric comorbidity with treatment completion among clients admitted to substance use treatment programs in a U.S. national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;175:157-163.

5. Brunette MF, Muesner KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):10-17.

6. Tiet QQ, Mausbach B. Treatments for patients with dual diagnosis: a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):513-536.

7. Kelly TM, Daley DC, Douaihy AB. Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):11-24.

8. Tsuang JT, Ho AP, Eckman TA, et al. Dual diagnosis treatment for patients with schizophrenia who are substance dependent. Psychatr Serv. 1997;48(7):887-889.

9. Rosen MI, Rosenheck RA, Shaner A, et al. Veterans who may need a payee to prevent misuse of funds for drugs. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(8):995-1000.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. SMA 17-5044, NSDUH Series H-52. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed August 7, 2018.

11. Rubinsky AD, Chen C, Batki SL, et al. Comparative utilization of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder and other psychiatric disorders among U.S. Veterans Health Administration patients with dual diagnoses. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:150-157.

12. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, McHugo GJ, et al. Improving the dual diagnosis capability of addiction and mental health treatment services: implementation factors associated with program level changes. J Dual Diag. 2010;6:237-250.

13. Reno R. Maintaining quality of care in a comprehensive dual diagnosis treatment program. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(5):673-675.

14. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris, Gotham HJ, et al. Dual diagnosis capability in mental health and addiction treatment services: an assessment of programs across multiple state systems. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41(2):205-214.

15. Gotham HJ, Claus RE, Selig K, et al. Increasing program capabilities to provide treatment for co-occurring substance use and mental disorders: organizational characteristics. J Subs Abuse Treat. 2010;38(2):160-169.

16. Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, et al. Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;61:47-59.

17. Drake RE, Bond GR. Implementing integrated mental health and substance abuse services. J Dual Diagnosis. 2010;6(3-4):251-262.

18. Miele GM, Trautman KD, Hasin DS. Assessing comorbid mental and substance-use disorders: a guide for clinical practice. J Pract Psychiatry Behav Health. 1996;5:272-282.

19. Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, et al. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;80(1):105-116.

20. Flynn PM, Brown BS. Co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment: Issues and prospects. J Subt Abuse Treat. 2008;34(1):36-47.

21. Grant BF, Stintson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

22. Pierre JM, Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC. “Iatrogenic malingering” in VA substance abuse treatment. Psych Services. 2003;54(2):253-254.

23. Pierre JM, Shnayder I, Wirshing DA, et al. Intranasal quetiapine abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(9):1718.

24. Pierre JM. Hallucinations in non-psychotic disorders: Toward a differential diagnosis of “hearing voices.” Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):22-35.

25. Pierre JM. Nonantipsychotic therapy for monosymptomatic auditory hallucinations. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(7):e33-e34.

26. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al. Sources of diagnostic uncertainty for chronically psychotic cocaine abusers. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(5):684-690.

27. Brown SA, Shuckit MA. Changes in depression among abstinent alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 1988;49(5):412-417.

28. Weddington WW, Brown BS, Haertzen CA, et al. Changes in mood, craving, and sleep during short-term abstinence reported by male cocaine addicts. A controlled, residential study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(9):861-868.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:210.

30. Roush S, Monica C, Carpenter-Song E, et al. First-person perspectives on Dual Diagnosis Anonymous (DDA): a qualitative study. J Dual Diagnosis. 2015;11(2):136-141.

31. Klein JW. Pharmacotherapy for substance abuse disorders. Med Clin N Am. 2016;100(4):891-910.

32. Horgan CM, Reif S, Hodgkin D, et al. Availability of addiction medications in private health plans. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(2):147-156.

33. Frances RJ. The wrath of grapes versus the self-medication hypothesis. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):287-289.

34. Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231-244.

35. Hall DH, Queener JE. Self-medication hypothesis of substance use: testing Khantzian’s updated theory. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(2):151-158.

36. Henwood B, Padgett DK. Reevaluating the self-medication hypothesis among the dually diagnosed. Am J Addict. 2007;16(3):160-165.

37. Lembke A. Time to abandon the self-medication hypothesis in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Drug Alc Abuse. 2012;38(6):524-529.

38. Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D’Souza DC. A systematic review of the evidence for medical marijuana in psychiatric indications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(8):1050-1064.

39. Walsh Z, Gonzalez R, Crosby K, et al. Medical cannabis and mental health: a guided systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:15-29.

40. Pierre JM. Risks of increasingly potent cannabis: the joint effects of potency and frequency. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16:14-20.

41. Zweben JE, Smith DE. Considerations in using psychotropic medication with dual diagnosis patients in recovery. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1989;21(2):221-228.

The term “dual diagnosis” describes the clinically challenging comorbidity of a substance use disorder (SUD) along with another major mental illness. Based on data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, the lifetime prevalence of SUDs among patients with mental illness is approximately 30%, and is higher among patients with certain mental disorders, such as schizophrenia (47%), bipolar disorder (61%), and antisocial personality disorder (84%).1 These statistics highlight that addiction is often the rule rather than the exception among those with severe mental illness.1 Not surprisingly, the combined effects of having an SUD along with another mental illness are uniformly negative (Table 12-4).

Based on outcomes research, the core tenets of evidence-based dual-diagnosis treatment include the importance of integrated (rather than parallel) and simultaneous (rather than sequential) care, which means an ideal treatment program includes a unified, multidisciplinary team whose coordinated efforts focus on treating both disorders concurrently.2 Evidence-based psychotherapies for addiction, including motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relapse prevention, contingency management, skills training, and/or case management, are a necessity,3,5 and must be balanced with rational and appropriate pharmacotherapy targeting both the SUD as well as the other disorder (Table 22,3,5-9).

3 ‘Real-world’ clinical challenges

Ideal vs real-world treatment

Treating patients with co-occurring disorders (CODs) within integrated dual-disorder treatment (IDDT) programs sounds straightforward. However, implementing evidence-based “best practice” treatment is a significant challenge in the real world for several reasons. First, individuals with CODs often struggle with poor insight, low motivation to change, and lack of access to health care. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 52% of individuals with CODs in the U.S. received no treatment at all in 2016.10 For patients with dual disorders who do seek care, most are not given access to specialty SUD treatment10 and may instead find themselves treated by psychiatrists with limited SUD training who fail to provide evidence-based psychotherapies and underutilize pharmacotherapies for SUDs.11 In the setting of CODs, the “harm reduction model” can be conflated with therapeutic nihilism, resulting in the neglect of SUD issues, with clinicians expecting patients to seek SUD treatment on their own, through self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous or in other community treatment programs staffed by nonprofessionals that often are not tailored to the unique needs of patients with dual disorders. Psychiatrists working with other mental health professionals who provide psychotherapy for SUDs often do so in parallel rather than in an evidence-based, integrated fashion.

IDDT programs are not widely available. One study found that fewer than 20% of addiction treatment programs and fewer than 10% of mental health programs in the U.S. met criteria for dual diagnosis–capable services.12 Getting treatment programs to become dual diagnosis–capable is possible, but it is a time-consuming and costly endeavor that, once achieved, requires continuous staff training and programmatic adaptations to interruptions in funding.13-16 With myriad barriers to the establishment and maintenance of IDDTs, many patients with dual disorders are left without access to the most effective and comprehensive care; as few as 4% of individuals with CODs are treated within integrated programs.17

Diagnostic dilemmas

Establishing whether or not a patient with an active SUD has another serious mental illness (SMI) is a crucial first step for optimizing treatment, but diagnostic reliability can prove challenging and requires careful clinical assessment (Table 3). As always in psychiatry, accurate diagnosis is limited to careful clinical assessment18 and, in the case of possible dual disorders, is complicated by the fact that both SUDs as well as non-SUDs can result in the same psychiatric symptoms (eg, insomnia, anxiety, depression, manic behaviors, and psychosis). Clinicians must therefore distinguish between:

- Symptoms of substance intoxication or withdrawal vs independent symptoms of an underlying psychiatric disorder (that persist beyond a month after cessation of intoxication or withdrawal)

- Subclinical symptoms vs threshold mental illness, keeping in mind that some mood and anxiety states can be normal given social situations and stressors (eg, turmoil in relationships, employment difficulties, homelessness, etc.)

- Any mental illness (AMI) vs SMI. The latter is defined by SAMHSA as AMI that substantially interferes with or limits ≥1 major life activities.10

With these distinctions in mind, data from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that dual-diagnosis comorbidity was higher when the threshold for mental illness was lower—among the 19 million adults in the U.S. with SUDs, the past-year prevalence was 43% for AMI and 14% for SMI.10 Looking at substance-induced disorders vs “independent” disorders, the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found that for individuals with SUDs, the past-year prevalence of an independent mood or anxiety disorder was 35% and 26%, respectively.19 Taken together, these findings illustrate the substantial rate of dual-diagnosis comorbidity, the diagnostic heterogeneity and range of severity of CODs,20 and the potential for both false negatives (eg, diagnosing a substance-induced syndrome when in fact a patient has an underlying disorder) and false positives (diagnosing a full-blown mental illness when symptoms are subclinical or substance-induced) when performing diagnostic assessments in the setting of known SUDs.

Continue to: False positives are more likely...

False positives are more likely when patients seeking treatment for non-SUDs don’t disclose active drug use, even when asked. Both patients and their treating clinicians may also be prone to underestimating the significant potential for morbidity associated with SUDs, such that substance-induced symptoms may be misattributed to a dual disorder. Diagnostic questioning and thorough chart review that includes careful assessment of whether psychiatric symptoms preceded the onset of substance use, and whether they persisted in the setting of extended sobriety, is therefore paramount for minimizing false positives when assessing for dual diagnoses.18,21 Likewise, random urine toxicology testing can be invaluable in verifying claims regarding sobriety.

Another factor that can complicate diagnosis is that there are often considerable secondary gains (eg, disability income, hospitalization, housing, access to prescription medications, and mitigation of the blame and stigma associated with addiction) associated with having a dual disorder as opposed to having “just” a SUD. As a result, for some patients, obtaining a non-SUD diagnosis can be highly incentivized.22,23 Clinicians must therefore be savvy about the high potential for malingering, embellishment, and mislabeling of symptoms when conducting diagnostic interviews. For example, in assessing for psychosis, the frequent endorsement of “hearing voices” in patients with SUDs often results in a diagnosis of schizophrenia or unspecified psychotic disorder,22 despite the fact that this symptom can occur during substance intoxication and withdrawal, is well documented among people without mental illness as well as those with non-psychotic disorders,24 and can resolve without medications or with non-antipsychotic pharmacotherapy.25

When assessing for dual disorders, diagnostic false positives and false negatives can both contribute to inappropriate treatment and unrealistic expectations for recovery, and therefore underscore the importance of careful diagnostic assessment. Even with diligent assessment, however, diagnostic clarity can prove elusive due to inadequate sobriety, inconsistent reporting, and poor memory.26 Therefore, for patients with known SUDs but diagnostic uncertainty about a dual disorder, the work-up should include a trial of prospective observation, with completion of appropriate detoxification, throughout a 1-month period of sobriety and in the absence of psychiatric medications, to determine if there are persistent symptoms that would justify a dual diagnosis. In research settings, such observations have revealed that most of depressive symptoms among alcoholics who present for substance abuse treatment resolve after a month of abstinence.27 A similar time course for resolution has been noted for anxiety, distress, fatigue, and depressive symptoms among individuals with cocaine dependence.28 These findings support the guideline established in DSM-IV that symptoms persisting beyond a month of sobriety “should be considered to be manifestations of an independent, non-substance-induced mental disorder,”29 while symptoms occurring within that month may well be substance-induced. Unfortunately, in real-world clinical practice, and particularly in outpatient settings, it can be quite difficult to achieve the requisite period of sobriety for reliable diagnosis, and patients are often prematurely prescribed medications (eg, an antidepressant, antipsychotic, or mood stabilizer) that can confound the cause of symptomatic resolution. Such prescriptions are driven by compelling pressures from patients to relieve their acute suffering, as well as the predilection of some clinicians to give patients “the benefit of doubt” in assessing for dual diagnoses. However, whether an inappropriate diagnosis or a prescription for an unnecessary medication represents a benefit is debatable at best.

Pharmacotherapy

A third real-world challenge in managing patients with dual disorders involves optimizing pharmacotherapy. Unfortunately, because patients with SUDs often are excluded from clinical trials, evidence-based guidance for patients with dual disorders is lacking. In addition, medications for both CODs often remain inaccessible to patients with dual disorders for 3 reasons:

- SUDs negatively impact medication adherence among patients with dual disorders, who sometimes point out that “it says right here on the bottle not to take this medication with drugs or alcohol!”

- Some self-help groups still espouse blanket opposition of any “psychotropic” medications, even when clearly indicated for patients with COD. Groups that recognize the importance of pharmacotherapy, such as Dual Diagnosis Anonymous (DDA), have emerged, but are not yet widely available.30

- Although there are increasing options for FDA-approved medications for SUDs, they are limited to the treatment of alcohol, opioid, and nicotine use disorders31; are often restricted due to hospital and health insurance formularies32; and remain underprescribed for patients with dual disorders.11

Continue to: Although underutilization of pharmacotherapy is...

Although underutilization of pharmacotherapy is a pitfall to be avoided in the treatment of patients with dual disorders, medication overutilization can be just as problematic. Patients with dual disorders are sometimes singularly focused on resolving acute anxiety, depression, or psychosis at the expense of working towards sobriety.33 Although the “self-medication hypothesis” is frequently invoked by patients and clinicians alike to suggest that substance use occurs in the service of “treating” underlying disorders,34 this theory has not been well supported in studies.35-37 Some patients may pledge dedication to abstinence, but still pressure physicians for a pharmacologic solution to their suffering. With expanding legalization of cannabis for both recreational and medical purposes, patients are increasingly seeking doctors’ recommendations for “medical marijuana” for a wide range of complaints, despite the fact that data supporting a therapeutic role for cannabis in the treatment of mental illness is sparse,38 whereas the potential harm in terms of either causing or worsening psychosis is well established.39,40 Clinicians must be knowledgeable about the abuse potential of prescribed medications, ranging from sleep aids, analgesics, and muscle relaxants to antidepressants and antipsychotics, while also being mindful of the psychological meaningfulness of seeking, prescribing, and not prescribing medications.41

Although the simultaneous treatment of patients with dual disorders that includes pharmacotherapy for both SUDs and CODs is vital for optimizing clinical outcomes, clinicians should strive for diagnostic accuracy and use medications judiciously. In addition, although pharmacotherapy often is necessary to deliver evidence-based treatment for patients with dual disorders, it is inadequate as standalone treatment and should be administered along with psychosocial interventions within an integrated, multidisciplinary treatment setting.

The keys to optimal outcomes

The treatment of patients with dual disorders can be challenging, to say the least. Ideal, evidence-based therapy in the form of an IDDT program can be difficult for clinicians to implement and for patients to access. Best efforts to perform meticulous clinical assessment to clarify diagnoses, use pharmacotherapy judiciously, work collaboratively in a multidisciplinary setting, and optimize treatment given available resources are keys to clinical success.

Bottom Line

Ideal treatment of patients with dual disorders consists of simultaneous, integrated interventions delivered by a multidisciplinary team. However, in the real world, limited resources, diagnostic challenges, and both over- and underutilization of pharmacotherapy often hamper optimal treatment.

Related Resources

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Co-occurring disorders. https://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/co-occurring.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. Dual diagnosis. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Related-Conditions/Dual-Diagnosis.

- Foundations Recovery Network. Dual diagnosis support groups. http://www.dualdiagnosis.org/resource/ddrn/self-helpsupport-groups/support-groups.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders evidence-based practices (EBP) KIT. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Integrated-Treatment-for-Co-Occurring-Disorders-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA08-4367.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA13-3992/SMA13-3992.pdf.

The term “dual diagnosis” describes the clinically challenging comorbidity of a substance use disorder (SUD) along with another major mental illness. Based on data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, the lifetime prevalence of SUDs among patients with mental illness is approximately 30%, and is higher among patients with certain mental disorders, such as schizophrenia (47%), bipolar disorder (61%), and antisocial personality disorder (84%).1 These statistics highlight that addiction is often the rule rather than the exception among those with severe mental illness.1 Not surprisingly, the combined effects of having an SUD along with another mental illness are uniformly negative (Table 12-4).

Based on outcomes research, the core tenets of evidence-based dual-diagnosis treatment include the importance of integrated (rather than parallel) and simultaneous (rather than sequential) care, which means an ideal treatment program includes a unified, multidisciplinary team whose coordinated efforts focus on treating both disorders concurrently.2 Evidence-based psychotherapies for addiction, including motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relapse prevention, contingency management, skills training, and/or case management, are a necessity,3,5 and must be balanced with rational and appropriate pharmacotherapy targeting both the SUD as well as the other disorder (Table 22,3,5-9).

3 ‘Real-world’ clinical challenges

Ideal vs real-world treatment

Treating patients with co-occurring disorders (CODs) within integrated dual-disorder treatment (IDDT) programs sounds straightforward. However, implementing evidence-based “best practice” treatment is a significant challenge in the real world for several reasons. First, individuals with CODs often struggle with poor insight, low motivation to change, and lack of access to health care. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 52% of individuals with CODs in the U.S. received no treatment at all in 2016.10 For patients with dual disorders who do seek care, most are not given access to specialty SUD treatment10 and may instead find themselves treated by psychiatrists with limited SUD training who fail to provide evidence-based psychotherapies and underutilize pharmacotherapies for SUDs.11 In the setting of CODs, the “harm reduction model” can be conflated with therapeutic nihilism, resulting in the neglect of SUD issues, with clinicians expecting patients to seek SUD treatment on their own, through self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous or in other community treatment programs staffed by nonprofessionals that often are not tailored to the unique needs of patients with dual disorders. Psychiatrists working with other mental health professionals who provide psychotherapy for SUDs often do so in parallel rather than in an evidence-based, integrated fashion.

IDDT programs are not widely available. One study found that fewer than 20% of addiction treatment programs and fewer than 10% of mental health programs in the U.S. met criteria for dual diagnosis–capable services.12 Getting treatment programs to become dual diagnosis–capable is possible, but it is a time-consuming and costly endeavor that, once achieved, requires continuous staff training and programmatic adaptations to interruptions in funding.13-16 With myriad barriers to the establishment and maintenance of IDDTs, many patients with dual disorders are left without access to the most effective and comprehensive care; as few as 4% of individuals with CODs are treated within integrated programs.17

Diagnostic dilemmas

Establishing whether or not a patient with an active SUD has another serious mental illness (SMI) is a crucial first step for optimizing treatment, but diagnostic reliability can prove challenging and requires careful clinical assessment (Table 3). As always in psychiatry, accurate diagnosis is limited to careful clinical assessment18 and, in the case of possible dual disorders, is complicated by the fact that both SUDs as well as non-SUDs can result in the same psychiatric symptoms (eg, insomnia, anxiety, depression, manic behaviors, and psychosis). Clinicians must therefore distinguish between:

- Symptoms of substance intoxication or withdrawal vs independent symptoms of an underlying psychiatric disorder (that persist beyond a month after cessation of intoxication or withdrawal)

- Subclinical symptoms vs threshold mental illness, keeping in mind that some mood and anxiety states can be normal given social situations and stressors (eg, turmoil in relationships, employment difficulties, homelessness, etc.)

- Any mental illness (AMI) vs SMI. The latter is defined by SAMHSA as AMI that substantially interferes with or limits ≥1 major life activities.10

With these distinctions in mind, data from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that dual-diagnosis comorbidity was higher when the threshold for mental illness was lower—among the 19 million adults in the U.S. with SUDs, the past-year prevalence was 43% for AMI and 14% for SMI.10 Looking at substance-induced disorders vs “independent” disorders, the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found that for individuals with SUDs, the past-year prevalence of an independent mood or anxiety disorder was 35% and 26%, respectively.19 Taken together, these findings illustrate the substantial rate of dual-diagnosis comorbidity, the diagnostic heterogeneity and range of severity of CODs,20 and the potential for both false negatives (eg, diagnosing a substance-induced syndrome when in fact a patient has an underlying disorder) and false positives (diagnosing a full-blown mental illness when symptoms are subclinical or substance-induced) when performing diagnostic assessments in the setting of known SUDs.

Continue to: False positives are more likely...

False positives are more likely when patients seeking treatment for non-SUDs don’t disclose active drug use, even when asked. Both patients and their treating clinicians may also be prone to underestimating the significant potential for morbidity associated with SUDs, such that substance-induced symptoms may be misattributed to a dual disorder. Diagnostic questioning and thorough chart review that includes careful assessment of whether psychiatric symptoms preceded the onset of substance use, and whether they persisted in the setting of extended sobriety, is therefore paramount for minimizing false positives when assessing for dual diagnoses.18,21 Likewise, random urine toxicology testing can be invaluable in verifying claims regarding sobriety.

Another factor that can complicate diagnosis is that there are often considerable secondary gains (eg, disability income, hospitalization, housing, access to prescription medications, and mitigation of the blame and stigma associated with addiction) associated with having a dual disorder as opposed to having “just” a SUD. As a result, for some patients, obtaining a non-SUD diagnosis can be highly incentivized.22,23 Clinicians must therefore be savvy about the high potential for malingering, embellishment, and mislabeling of symptoms when conducting diagnostic interviews. For example, in assessing for psychosis, the frequent endorsement of “hearing voices” in patients with SUDs often results in a diagnosis of schizophrenia or unspecified psychotic disorder,22 despite the fact that this symptom can occur during substance intoxication and withdrawal, is well documented among people without mental illness as well as those with non-psychotic disorders,24 and can resolve without medications or with non-antipsychotic pharmacotherapy.25

When assessing for dual disorders, diagnostic false positives and false negatives can both contribute to inappropriate treatment and unrealistic expectations for recovery, and therefore underscore the importance of careful diagnostic assessment. Even with diligent assessment, however, diagnostic clarity can prove elusive due to inadequate sobriety, inconsistent reporting, and poor memory.26 Therefore, for patients with known SUDs but diagnostic uncertainty about a dual disorder, the work-up should include a trial of prospective observation, with completion of appropriate detoxification, throughout a 1-month period of sobriety and in the absence of psychiatric medications, to determine if there are persistent symptoms that would justify a dual diagnosis. In research settings, such observations have revealed that most of depressive symptoms among alcoholics who present for substance abuse treatment resolve after a month of abstinence.27 A similar time course for resolution has been noted for anxiety, distress, fatigue, and depressive symptoms among individuals with cocaine dependence.28 These findings support the guideline established in DSM-IV that symptoms persisting beyond a month of sobriety “should be considered to be manifestations of an independent, non-substance-induced mental disorder,”29 while symptoms occurring within that month may well be substance-induced. Unfortunately, in real-world clinical practice, and particularly in outpatient settings, it can be quite difficult to achieve the requisite period of sobriety for reliable diagnosis, and patients are often prematurely prescribed medications (eg, an antidepressant, antipsychotic, or mood stabilizer) that can confound the cause of symptomatic resolution. Such prescriptions are driven by compelling pressures from patients to relieve their acute suffering, as well as the predilection of some clinicians to give patients “the benefit of doubt” in assessing for dual diagnoses. However, whether an inappropriate diagnosis or a prescription for an unnecessary medication represents a benefit is debatable at best.

Pharmacotherapy

A third real-world challenge in managing patients with dual disorders involves optimizing pharmacotherapy. Unfortunately, because patients with SUDs often are excluded from clinical trials, evidence-based guidance for patients with dual disorders is lacking. In addition, medications for both CODs often remain inaccessible to patients with dual disorders for 3 reasons:

- SUDs negatively impact medication adherence among patients with dual disorders, who sometimes point out that “it says right here on the bottle not to take this medication with drugs or alcohol!”

- Some self-help groups still espouse blanket opposition of any “psychotropic” medications, even when clearly indicated for patients with COD. Groups that recognize the importance of pharmacotherapy, such as Dual Diagnosis Anonymous (DDA), have emerged, but are not yet widely available.30

- Although there are increasing options for FDA-approved medications for SUDs, they are limited to the treatment of alcohol, opioid, and nicotine use disorders31; are often restricted due to hospital and health insurance formularies32; and remain underprescribed for patients with dual disorders.11

Continue to: Although underutilization of pharmacotherapy is...

Although underutilization of pharmacotherapy is a pitfall to be avoided in the treatment of patients with dual disorders, medication overutilization can be just as problematic. Patients with dual disorders are sometimes singularly focused on resolving acute anxiety, depression, or psychosis at the expense of working towards sobriety.33 Although the “self-medication hypothesis” is frequently invoked by patients and clinicians alike to suggest that substance use occurs in the service of “treating” underlying disorders,34 this theory has not been well supported in studies.35-37 Some patients may pledge dedication to abstinence, but still pressure physicians for a pharmacologic solution to their suffering. With expanding legalization of cannabis for both recreational and medical purposes, patients are increasingly seeking doctors’ recommendations for “medical marijuana” for a wide range of complaints, despite the fact that data supporting a therapeutic role for cannabis in the treatment of mental illness is sparse,38 whereas the potential harm in terms of either causing or worsening psychosis is well established.39,40 Clinicians must be knowledgeable about the abuse potential of prescribed medications, ranging from sleep aids, analgesics, and muscle relaxants to antidepressants and antipsychotics, while also being mindful of the psychological meaningfulness of seeking, prescribing, and not prescribing medications.41

Although the simultaneous treatment of patients with dual disorders that includes pharmacotherapy for both SUDs and CODs is vital for optimizing clinical outcomes, clinicians should strive for diagnostic accuracy and use medications judiciously. In addition, although pharmacotherapy often is necessary to deliver evidence-based treatment for patients with dual disorders, it is inadequate as standalone treatment and should be administered along with psychosocial interventions within an integrated, multidisciplinary treatment setting.

The keys to optimal outcomes

The treatment of patients with dual disorders can be challenging, to say the least. Ideal, evidence-based therapy in the form of an IDDT program can be difficult for clinicians to implement and for patients to access. Best efforts to perform meticulous clinical assessment to clarify diagnoses, use pharmacotherapy judiciously, work collaboratively in a multidisciplinary setting, and optimize treatment given available resources are keys to clinical success.

Bottom Line

Ideal treatment of patients with dual disorders consists of simultaneous, integrated interventions delivered by a multidisciplinary team. However, in the real world, limited resources, diagnostic challenges, and both over- and underutilization of pharmacotherapy often hamper optimal treatment.

Related Resources

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Co-occurring disorders. https://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/co-occurring.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. Dual diagnosis. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Related-Conditions/Dual-Diagnosis.

- Foundations Recovery Network. Dual diagnosis support groups. http://www.dualdiagnosis.org/resource/ddrn/self-helpsupport-groups/support-groups.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders evidence-based practices (EBP) KIT. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Integrated-Treatment-for-Co-Occurring-Disorders-Evidence-Based-Practices-EBP-KIT/SMA08-4367.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA13-3992/SMA13-3992.pdf.

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2511-2518.

2. Drake RE, Mercer-McFadden C, Muesner KT, et al. Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(4):589-608.

3. Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE, et al. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): a review of empiric evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17(1):24-34.

4. Krawczyk N, Feder KA, Saloner B, et al. The association of psychiatric comorbidity with treatment completion among clients admitted to substance use treatment programs in a U.S. national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;175:157-163.

5. Brunette MF, Muesner KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):10-17.

6. Tiet QQ, Mausbach B. Treatments for patients with dual diagnosis: a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):513-536.

7. Kelly TM, Daley DC, Douaihy AB. Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):11-24.

8. Tsuang JT, Ho AP, Eckman TA, et al. Dual diagnosis treatment for patients with schizophrenia who are substance dependent. Psychatr Serv. 1997;48(7):887-889.

9. Rosen MI, Rosenheck RA, Shaner A, et al. Veterans who may need a payee to prevent misuse of funds for drugs. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(8):995-1000.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. SMA 17-5044, NSDUH Series H-52. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed August 7, 2018.

11. Rubinsky AD, Chen C, Batki SL, et al. Comparative utilization of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder and other psychiatric disorders among U.S. Veterans Health Administration patients with dual diagnoses. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:150-157.

12. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, McHugo GJ, et al. Improving the dual diagnosis capability of addiction and mental health treatment services: implementation factors associated with program level changes. J Dual Diag. 2010;6:237-250.

13. Reno R. Maintaining quality of care in a comprehensive dual diagnosis treatment program. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(5):673-675.

14. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris, Gotham HJ, et al. Dual diagnosis capability in mental health and addiction treatment services: an assessment of programs across multiple state systems. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41(2):205-214.

15. Gotham HJ, Claus RE, Selig K, et al. Increasing program capabilities to provide treatment for co-occurring substance use and mental disorders: organizational characteristics. J Subs Abuse Treat. 2010;38(2):160-169.

16. Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, et al. Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;61:47-59.

17. Drake RE, Bond GR. Implementing integrated mental health and substance abuse services. J Dual Diagnosis. 2010;6(3-4):251-262.

18. Miele GM, Trautman KD, Hasin DS. Assessing comorbid mental and substance-use disorders: a guide for clinical practice. J Pract Psychiatry Behav Health. 1996;5:272-282.

19. Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, et al. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;80(1):105-116.

20. Flynn PM, Brown BS. Co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment: Issues and prospects. J Subt Abuse Treat. 2008;34(1):36-47.

21. Grant BF, Stintson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

22. Pierre JM, Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC. “Iatrogenic malingering” in VA substance abuse treatment. Psych Services. 2003;54(2):253-254.

23. Pierre JM, Shnayder I, Wirshing DA, et al. Intranasal quetiapine abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(9):1718.

24. Pierre JM. Hallucinations in non-psychotic disorders: Toward a differential diagnosis of “hearing voices.” Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):22-35.

25. Pierre JM. Nonantipsychotic therapy for monosymptomatic auditory hallucinations. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(7):e33-e34.

26. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al. Sources of diagnostic uncertainty for chronically psychotic cocaine abusers. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(5):684-690.

27. Brown SA, Shuckit MA. Changes in depression among abstinent alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 1988;49(5):412-417.

28. Weddington WW, Brown BS, Haertzen CA, et al. Changes in mood, craving, and sleep during short-term abstinence reported by male cocaine addicts. A controlled, residential study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(9):861-868.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:210.

30. Roush S, Monica C, Carpenter-Song E, et al. First-person perspectives on Dual Diagnosis Anonymous (DDA): a qualitative study. J Dual Diagnosis. 2015;11(2):136-141.

31. Klein JW. Pharmacotherapy for substance abuse disorders. Med Clin N Am. 2016;100(4):891-910.

32. Horgan CM, Reif S, Hodgkin D, et al. Availability of addiction medications in private health plans. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(2):147-156.

33. Frances RJ. The wrath of grapes versus the self-medication hypothesis. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):287-289.

34. Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231-244.

35. Hall DH, Queener JE. Self-medication hypothesis of substance use: testing Khantzian’s updated theory. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(2):151-158.

36. Henwood B, Padgett DK. Reevaluating the self-medication hypothesis among the dually diagnosed. Am J Addict. 2007;16(3):160-165.

37. Lembke A. Time to abandon the self-medication hypothesis in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Drug Alc Abuse. 2012;38(6):524-529.

38. Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D’Souza DC. A systematic review of the evidence for medical marijuana in psychiatric indications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(8):1050-1064.

39. Walsh Z, Gonzalez R, Crosby K, et al. Medical cannabis and mental health: a guided systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:15-29.

40. Pierre JM. Risks of increasingly potent cannabis: the joint effects of potency and frequency. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16:14-20.

41. Zweben JE, Smith DE. Considerations in using psychotropic medication with dual diagnosis patients in recovery. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1989;21(2):221-228.

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264(19):2511-2518.

2. Drake RE, Mercer-McFadden C, Muesner KT, et al. Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(4):589-608.

3. Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE, et al. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): a review of empiric evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17(1):24-34.

4. Krawczyk N, Feder KA, Saloner B, et al. The association of psychiatric comorbidity with treatment completion among clients admitted to substance use treatment programs in a U.S. national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;175:157-163.

5. Brunette MF, Muesner KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 7):10-17.

6. Tiet QQ, Mausbach B. Treatments for patients with dual diagnosis: a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):513-536.

7. Kelly TM, Daley DC, Douaihy AB. Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):11-24.

8. Tsuang JT, Ho AP, Eckman TA, et al. Dual diagnosis treatment for patients with schizophrenia who are substance dependent. Psychatr Serv. 1997;48(7):887-889.

9. Rosen MI, Rosenheck RA, Shaner A, et al. Veterans who may need a payee to prevent misuse of funds for drugs. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(8):995-1000.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. SMA 17-5044, NSDUH Series H-52. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed August 7, 2018.

11. Rubinsky AD, Chen C, Batki SL, et al. Comparative utilization of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder and other psychiatric disorders among U.S. Veterans Health Administration patients with dual diagnoses. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:150-157.

12. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, McHugo GJ, et al. Improving the dual diagnosis capability of addiction and mental health treatment services: implementation factors associated with program level changes. J Dual Diag. 2010;6:237-250.

13. Reno R. Maintaining quality of care in a comprehensive dual diagnosis treatment program. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(5):673-675.

14. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris, Gotham HJ, et al. Dual diagnosis capability in mental health and addiction treatment services: an assessment of programs across multiple state systems. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41(2):205-214.

15. Gotham HJ, Claus RE, Selig K, et al. Increasing program capabilities to provide treatment for co-occurring substance use and mental disorders: organizational characteristics. J Subs Abuse Treat. 2010;38(2):160-169.

16. Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, et al. Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;61:47-59.

17. Drake RE, Bond GR. Implementing integrated mental health and substance abuse services. J Dual Diagnosis. 2010;6(3-4):251-262.

18. Miele GM, Trautman KD, Hasin DS. Assessing comorbid mental and substance-use disorders: a guide for clinical practice. J Pract Psychiatry Behav Health. 1996;5:272-282.

19. Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, et al. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;80(1):105-116.

20. Flynn PM, Brown BS. Co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment: Issues and prospects. J Subt Abuse Treat. 2008;34(1):36-47.

21. Grant BF, Stintson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

22. Pierre JM, Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC. “Iatrogenic malingering” in VA substance abuse treatment. Psych Services. 2003;54(2):253-254.

23. Pierre JM, Shnayder I, Wirshing DA, et al. Intranasal quetiapine abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(9):1718.

24. Pierre JM. Hallucinations in non-psychotic disorders: Toward a differential diagnosis of “hearing voices.” Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):22-35.

25. Pierre JM. Nonantipsychotic therapy for monosymptomatic auditory hallucinations. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(7):e33-e34.

26. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al. Sources of diagnostic uncertainty for chronically psychotic cocaine abusers. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(5):684-690.

27. Brown SA, Shuckit MA. Changes in depression among abstinent alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 1988;49(5):412-417.

28. Weddington WW, Brown BS, Haertzen CA, et al. Changes in mood, craving, and sleep during short-term abstinence reported by male cocaine addicts. A controlled, residential study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(9):861-868.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:210.

30. Roush S, Monica C, Carpenter-Song E, et al. First-person perspectives on Dual Diagnosis Anonymous (DDA): a qualitative study. J Dual Diagnosis. 2015;11(2):136-141.

31. Klein JW. Pharmacotherapy for substance abuse disorders. Med Clin N Am. 2016;100(4):891-910.

32. Horgan CM, Reif S, Hodgkin D, et al. Availability of addiction medications in private health plans. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(2):147-156.

33. Frances RJ. The wrath of grapes versus the self-medication hypothesis. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):287-289.

34. Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231-244.

35. Hall DH, Queener JE. Self-medication hypothesis of substance use: testing Khantzian’s updated theory. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(2):151-158.

36. Henwood B, Padgett DK. Reevaluating the self-medication hypothesis among the dually diagnosed. Am J Addict. 2007;16(3):160-165.

37. Lembke A. Time to abandon the self-medication hypothesis in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Drug Alc Abuse. 2012;38(6):524-529.

38. Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D’Souza DC. A systematic review of the evidence for medical marijuana in psychiatric indications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(8):1050-1064.

39. Walsh Z, Gonzalez R, Crosby K, et al. Medical cannabis and mental health: a guided systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:15-29.

40. Pierre JM. Risks of increasingly potent cannabis: the joint effects of potency and frequency. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16:14-20.

41. Zweben JE, Smith DE. Considerations in using psychotropic medication with dual diagnosis patients in recovery. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1989;21(2):221-228.