User login

Paid parental leave policies have been unevenly adopted among academic medical centers, according to a study published in the Journal of Surgical Research. These policies, or their lack, may have important ramifications for recruiting and specialty selection by surgeons, and for women of child-rearing age in particular.

Parental leave for surgeons has been championed by the American College of Surgeons, among other professional societies, in formal statements and supportive policies in recent years.

Dina S. Itum, MD, a fifth-year resident in the department of surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Houston, and a research team looked into how widespread parental leave is for surgeons in US medical centers. Their sample was the 91 top-ranked academic medical centers identified by U.S. News & World Report in 2016. The method used by U.S. News & World Report for ranking medical centers is based on student selectivity, dean and residency directors’ peer assessment of national institutions, faculty to student ratio, and the dollar amount in NIH research grants received.

“Parental leave” was defined by the research team as any leave dedicated to new mothers, fathers and/or primary caregivers after childbirth or adoption. “Paid leave” was defined as some protected leave with salary without mandated use of sick leave or vacation leave.

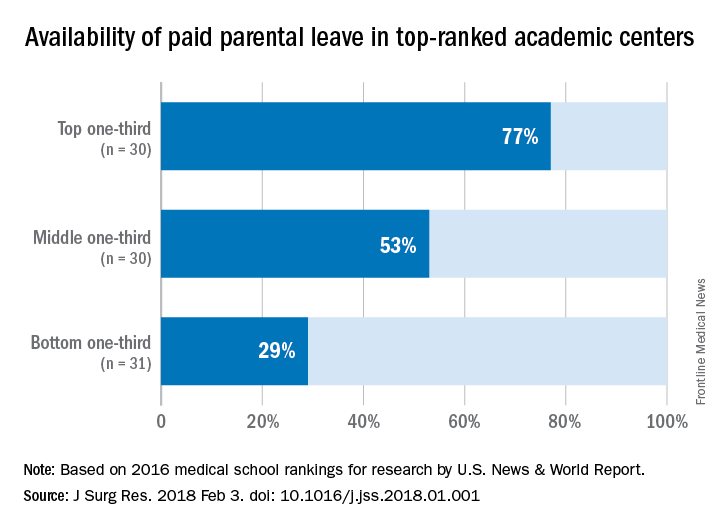

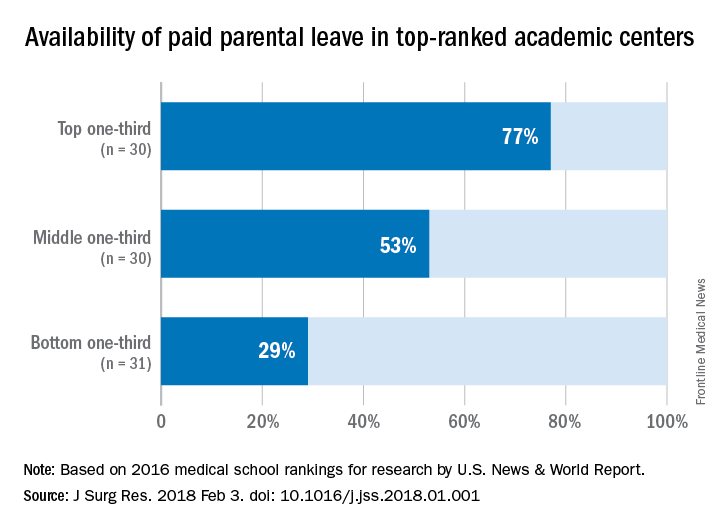

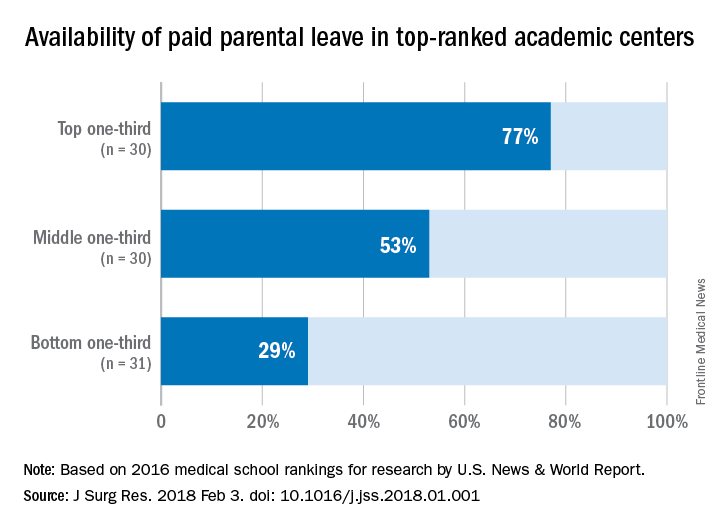

The study found that among the top-ranked 91 institutions, 48 (53%) offered some form of paid parental leave to faculty surgeons. The higher the rating, the more likely the institution offered paid parental leave: 77% of those in the top third of rankings vs. 53% in the middle third and 29% in the bottom third. Private institutions were more likely to offer paid leave of 6 weeks or longer; 67% vs. 33% of public institutions.

The investigators posed a question: Did these institutions implement the policy to attract the top talent, or did the policy improve faculty morale and productivity leading to a higher ranking? The study does not answer the question, but the investigators consider it an important issue for further study.

The investigators also suggested that surgeons of child-rearing age use parental leave information their in their own employment negotiations. “As physicians, we are aware of the health care benefits associated with parental leave, and as leaders within our communities, we should be at the forefront of supporting further advancement of this benefit,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Itum DS et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Feb 3. doi. org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.01.001.

Paid parental leave policies have been unevenly adopted among academic medical centers, according to a study published in the Journal of Surgical Research. These policies, or their lack, may have important ramifications for recruiting and specialty selection by surgeons, and for women of child-rearing age in particular.

Parental leave for surgeons has been championed by the American College of Surgeons, among other professional societies, in formal statements and supportive policies in recent years.

Dina S. Itum, MD, a fifth-year resident in the department of surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Houston, and a research team looked into how widespread parental leave is for surgeons in US medical centers. Their sample was the 91 top-ranked academic medical centers identified by U.S. News & World Report in 2016. The method used by U.S. News & World Report for ranking medical centers is based on student selectivity, dean and residency directors’ peer assessment of national institutions, faculty to student ratio, and the dollar amount in NIH research grants received.

“Parental leave” was defined by the research team as any leave dedicated to new mothers, fathers and/or primary caregivers after childbirth or adoption. “Paid leave” was defined as some protected leave with salary without mandated use of sick leave or vacation leave.

The study found that among the top-ranked 91 institutions, 48 (53%) offered some form of paid parental leave to faculty surgeons. The higher the rating, the more likely the institution offered paid parental leave: 77% of those in the top third of rankings vs. 53% in the middle third and 29% in the bottom third. Private institutions were more likely to offer paid leave of 6 weeks or longer; 67% vs. 33% of public institutions.

The investigators posed a question: Did these institutions implement the policy to attract the top talent, or did the policy improve faculty morale and productivity leading to a higher ranking? The study does not answer the question, but the investigators consider it an important issue for further study.

The investigators also suggested that surgeons of child-rearing age use parental leave information their in their own employment negotiations. “As physicians, we are aware of the health care benefits associated with parental leave, and as leaders within our communities, we should be at the forefront of supporting further advancement of this benefit,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Itum DS et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Feb 3. doi. org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.01.001.

Paid parental leave policies have been unevenly adopted among academic medical centers, according to a study published in the Journal of Surgical Research. These policies, or their lack, may have important ramifications for recruiting and specialty selection by surgeons, and for women of child-rearing age in particular.

Parental leave for surgeons has been championed by the American College of Surgeons, among other professional societies, in formal statements and supportive policies in recent years.

Dina S. Itum, MD, a fifth-year resident in the department of surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Houston, and a research team looked into how widespread parental leave is for surgeons in US medical centers. Their sample was the 91 top-ranked academic medical centers identified by U.S. News & World Report in 2016. The method used by U.S. News & World Report for ranking medical centers is based on student selectivity, dean and residency directors’ peer assessment of national institutions, faculty to student ratio, and the dollar amount in NIH research grants received.

“Parental leave” was defined by the research team as any leave dedicated to new mothers, fathers and/or primary caregivers after childbirth or adoption. “Paid leave” was defined as some protected leave with salary without mandated use of sick leave or vacation leave.

The study found that among the top-ranked 91 institutions, 48 (53%) offered some form of paid parental leave to faculty surgeons. The higher the rating, the more likely the institution offered paid parental leave: 77% of those in the top third of rankings vs. 53% in the middle third and 29% in the bottom third. Private institutions were more likely to offer paid leave of 6 weeks or longer; 67% vs. 33% of public institutions.

The investigators posed a question: Did these institutions implement the policy to attract the top talent, or did the policy improve faculty morale and productivity leading to a higher ranking? The study does not answer the question, but the investigators consider it an important issue for further study.

The investigators also suggested that surgeons of child-rearing age use parental leave information their in their own employment negotiations. “As physicians, we are aware of the health care benefits associated with parental leave, and as leaders within our communities, we should be at the forefront of supporting further advancement of this benefit,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Itum DS et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Feb 3. doi. org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.01.001.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Parental leave policies have been unevenly adopted by U.S. medical schools.

Major finding: Among the top 91 ranked medical schools, 53% offer paid parental leave.

Data source: Survey of 91 top academic medical centers identified in U.S. News & World Report 2016 listing.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Itum DS et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Feb 3. doi. org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.01.001.