User login

- Neonatal death from group B strep

(Medical Verdicts, March 2011)

Before widespread intrapartum prophylaxis against group B Streptococcus (GBS) was initiated in the late 1990s, roughly 7,500 newborns developed invasive GBS disease every year in the United States, and the case-fatality rate reached an astonishing—and disheartening—50%.1 Now that all pregnant women undergo culture-based screening at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation, the incidence of early-onset neonatal GBS disease has declined precipitously.

According to a report issued late last year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), GBS now causes roughly 1,200 cases of early-onset invasive disease every year, approximately 70% of them among infants born at or after 37 weeks’ gestation, and the case-fatality rate is 4% to 6%.2 Mortality is higher among preterm infants, with a case-fatality rate of 20% to 30% for infants born at or before 33 weeks’ gestation, compared with 2% to 3% for full-term infants.2

Despite progress, GBS remains the leading cause of early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States. In November 2010, to spur further improvement, the CDC updated its guidelines on prevention of perinatal GBS, and ACOG and other professional organizations endorsed the new recommendations. This article highlights changes to the guidelines—the first since 2002—in four critical areas:

- clarification of who should receive GBS prophylaxis, and when

- updated algorithms for screening and intrapartum prophylaxis for women who experience preterm labor or pre-term premature rupture of membranes (pPROM)

- new recommended dosage of penicillin G for prophylaxis

- updated regimens for prophylaxis among women who are allergic to penicillin.2

When is intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis indicated? When is it not?

| Indicated | Not indicated |

|---|---|

Previous infant with invasive GBS disease GBS bacteriuria during any trimester of the current pregnancy* Positive GBS vaginal-rectal screening culture in late gestation† during current pregnancy* Unknown GBS status at the onset of labor (culture not done, incomplete, or results unknown) and any of the following:

| Colonization with GBS during a previous pregnancy (unless an indication for GBS prophylaxis is present for current pregnancy) GBS bacteriuria during previous pregnancy (unless an indication for GBS prophylaxis is present for current pregnancy) Negative vaginal and rectal GBS screening culture in late gestation† during the current pregnancy, regardless of intrapartum risk factors Cesarean delivery performed before onset of labor on a woman who has intact amniotic membranes, regardless of GBS colonization status or gestational age |

| SOURCE: CDC2 * Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated in this circumstance if a cesarean delivery is performed before onset of labor on a woman who has intact amniotic membranes. † Optimal timing for prenatal GBS screening is at 35–37 weeks’ gestation. § Recommendations for the use of intrapartum antibiotics for prevention of early-onset GBS disease in the setting of threatened preterm delivery are presented in FIGURES 1 and 2. ¶ If amnionitis is suspected, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy that includes an agent known to be active against GBS should replace GBS prophylaxis. ** NAAT testing for GBS is optional and might not be available in all settings. If intrapartum NAAT is negative for GBS but any other intrapartum risk factor (delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation, amniotic membrane rupture at ≥18 hours, or temperature ≥100.4°F [≥38.0°C]) is present, then intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated. | |

Who should receive prophylaxis?

In its report, the CDC reiterated the indications and “nonindications” for intrapartum prophylaxis (TABLE). Among the clarifications:

- Women who have GBS isolated from the urine at any time during pregnancy should undergo intrapartum prophylaxis. They do not need third-trimester screening for GBS.

- Women who had a previous infant with invasive GBS disease should also undergo intrapartum prophylaxis, with no need for third-trimester screening

- All other pregnant women should undergo screening at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation. If results are positive, intrapartum prophylaxis is indicated.

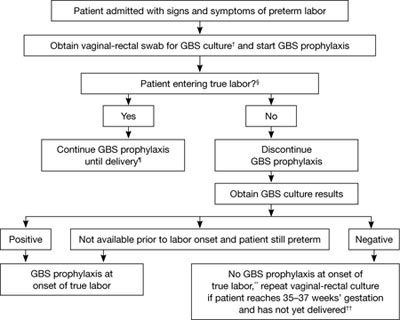

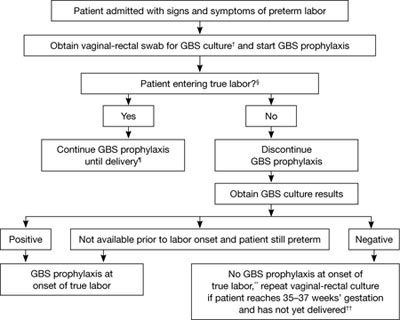

FIGURE 1 Recommended management when a patient experiences preterm labor*

SOURCE: CDC2

*At <37 weeks and 0 days’ gestation.

† If patient has undergone vaginal-rectal GBS culture within the preceding 5 weeks, the results of that culture should guide management. GBS-colonized women should receive intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. No antibiotics are indicated for GBS prophylaxis if a vaginal-rectal screen within 5 weeks was negative.

§ Patient should be regularly assessed for progression to true labor; if the patient is considered not to be in true labor, discontinue GBS prophylaxis.

¶ If GBS culture results become available prior to delivery and are negative, discontinue GBS prophylaxis.

** Unless subsequent GBS culture prior to delivery is positive.

†† A negative GBS screen is considered valid for 5 weeks. If a patient with a history of preterm labor is readmitted with signs and symptoms of preterm labor and had a negative GBS screen >5 weeks earlier, she should be rescreened and managed according to this algorithm at that time.

CDC now offers distinct algorithms for preterm labor and pPROM

To clarify the management of two distinct groups of women, the CDC developed separate algorithms for GBS prophylaxis in the setting of threatened preterm delivery—one for spontaneous preterm labor (FIGURE 1) and another for pPROM (FIGURE 2). In addition, it now recommends:

- When GBS prophylaxis is given to a woman who has signs and symptoms of preterm labor, it should be discontinued if it is later determined that she is not in true labor

- If antibiotics given to prolong latency for pPROM include adequate coverage for GBS (i.e., 2 g intravenous [IV] ampicillin followed by 1 g IV ampicillin every 6 hours for 48 hours), no additional prophylaxis for GBS is necessary, provided delivery occurs during administration of that antibiotic regimen. Oral antibiotics alone are not adequate for GBS prophylaxis.

- When a woman who has pPROM is not in labor and is receiving antibiotics with adequate GBS coverage to prolong latency, she should be managed according to the standard of care for pPROM. GBS testing results should not affect the duration of antibiotics.

- When a woman who has pPROM is not in labor and is not receiving antibiotics to prolong latency (or is receiving antibiotics that do not have adequate GBS coverage), she should undergo GBS prophylaxis for 48 hours unless a GBS screen performed within 5 weeks was negative.

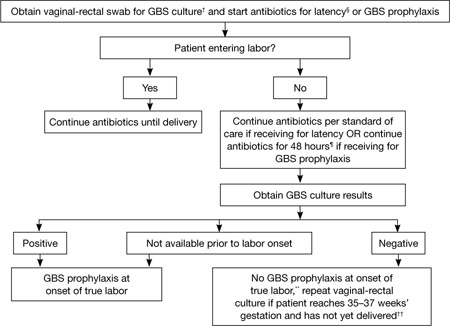

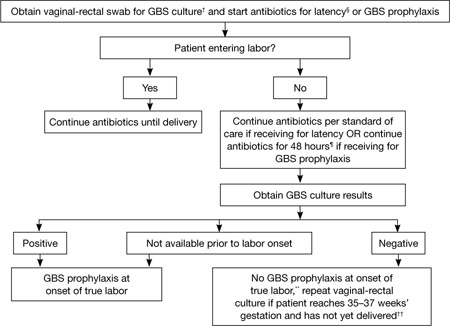

FIGURE 2 GBS screening and prophylaxis for preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM)*

SOURCE: CDC2

* At <37 weeks and 0 days’ gestation.

† If patient has undergone vaginal-rectal GBS culture within the preceding 5 weeks, the results of that culture should guide management. GBS-colonized women should receive intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. No antibiotics are indicated for GBS prophylaxis if a vaginal-rectal screen within 5 weeks was negative.

§ Antibiotics given for latency in the setting of pPROM that include ampicillin 2 g IV once, followed by 1 g IV every 6 hours for at least 48 hours are adequate for GBS prophylaxis. If other regimens are used, GBS prophylaxis should be initiated in addition.

¶ GBS prophylaxis should be discontinued at 48 hours for women with pPROM who are not in labor. If results from a GBS screen performed at admission become available during the 48-hour period and are negative, GBS prophylaxis should be discontinued at that time.

** Unless subsequent GBS culture prior to delivery is positive.

†† A negative GBS screen is considered valid for 5 weeks. If a patient with pPROM is entering labor and had a negative GBS screen >5 weeks earlier, she should be rescreened and managed according to this algorithm at that time.

New dosage allows room for flexibility

The CDC now recommends a dosage of 5 million units of IV penicillin G for GBS prophylaxis, followed by 2.5 to 3.0 million units IV every 4 hours. The range of 2.5 to 3.0 million units is recommended to ensure that the drug reaches an adequate concentration in the fetal circulation and amniotic fluid without being neurotoxic. The choice of dosage within that range should be guided by which formulations of penicillin G are readily available, says the CDC.

Penicillin remains the agent of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis, but ampicillin is an acceptable alternative.

If a woman is allergic to penicillin but has no history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria following administration of a penicillin or cephalosporin, she should be given 2 g IV cefazolin, followed by 1 g IV cefazolin every 8 hours until delivery. If she does have a history of anaphylaxis or is at high risk for anaphylaxis, ask the laboratory for antimicrobial susceptibility testing on the antenatal GBS culture. If the isolate is susceptible to clindamycin, give her 900 mg IV clindamycin every 8 hours until delivery. If it is not susceptible to clindamycin, give her 1 g IV vancomycin every 12 hours until the time of delivery.

The CDC no longer considers erythromycin to be an acceptable alternative for intrapartum GBS prophylaxis for penicillin-allergic women at high risk of anaphylaxis.

Where we go from here

Although early-onset GBS disease has become relatively uncommon, the rate of maternal GBS colonization remains unchanged since the 1970s. Therefore, it is important to continue efforts to sustain and improve on the progress that has been made. There is also a need to monitor for potential adverse consequences of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, such as emergence of bacterial antimicrobial resistance or an increased incidence or severity of nonGBS neonatal pathogens, the CDC observes. “In the absence of a licensed GBS vaccine, universal screening and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis continue to be the cornerstones of early-onset GBS disease prevention."

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Baker CJ, Barrett FF. Group B streptococcal infections in infants. The importance of the various serotypes. JAMA. 1974;230(8):1158-1160.

2. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease: Revised Guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(RR-10):1-36.

- Neonatal death from group B strep

(Medical Verdicts, March 2011)

Before widespread intrapartum prophylaxis against group B Streptococcus (GBS) was initiated in the late 1990s, roughly 7,500 newborns developed invasive GBS disease every year in the United States, and the case-fatality rate reached an astonishing—and disheartening—50%.1 Now that all pregnant women undergo culture-based screening at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation, the incidence of early-onset neonatal GBS disease has declined precipitously.

According to a report issued late last year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), GBS now causes roughly 1,200 cases of early-onset invasive disease every year, approximately 70% of them among infants born at or after 37 weeks’ gestation, and the case-fatality rate is 4% to 6%.2 Mortality is higher among preterm infants, with a case-fatality rate of 20% to 30% for infants born at or before 33 weeks’ gestation, compared with 2% to 3% for full-term infants.2

Despite progress, GBS remains the leading cause of early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States. In November 2010, to spur further improvement, the CDC updated its guidelines on prevention of perinatal GBS, and ACOG and other professional organizations endorsed the new recommendations. This article highlights changes to the guidelines—the first since 2002—in four critical areas:

- clarification of who should receive GBS prophylaxis, and when

- updated algorithms for screening and intrapartum prophylaxis for women who experience preterm labor or pre-term premature rupture of membranes (pPROM)

- new recommended dosage of penicillin G for prophylaxis

- updated regimens for prophylaxis among women who are allergic to penicillin.2

When is intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis indicated? When is it not?

| Indicated | Not indicated |

|---|---|

Previous infant with invasive GBS disease GBS bacteriuria during any trimester of the current pregnancy* Positive GBS vaginal-rectal screening culture in late gestation† during current pregnancy* Unknown GBS status at the onset of labor (culture not done, incomplete, or results unknown) and any of the following:

| Colonization with GBS during a previous pregnancy (unless an indication for GBS prophylaxis is present for current pregnancy) GBS bacteriuria during previous pregnancy (unless an indication for GBS prophylaxis is present for current pregnancy) Negative vaginal and rectal GBS screening culture in late gestation† during the current pregnancy, regardless of intrapartum risk factors Cesarean delivery performed before onset of labor on a woman who has intact amniotic membranes, regardless of GBS colonization status or gestational age |

| SOURCE: CDC2 * Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated in this circumstance if a cesarean delivery is performed before onset of labor on a woman who has intact amniotic membranes. † Optimal timing for prenatal GBS screening is at 35–37 weeks’ gestation. § Recommendations for the use of intrapartum antibiotics for prevention of early-onset GBS disease in the setting of threatened preterm delivery are presented in FIGURES 1 and 2. ¶ If amnionitis is suspected, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy that includes an agent known to be active against GBS should replace GBS prophylaxis. ** NAAT testing for GBS is optional and might not be available in all settings. If intrapartum NAAT is negative for GBS but any other intrapartum risk factor (delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation, amniotic membrane rupture at ≥18 hours, or temperature ≥100.4°F [≥38.0°C]) is present, then intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated. | |

Who should receive prophylaxis?

In its report, the CDC reiterated the indications and “nonindications” for intrapartum prophylaxis (TABLE). Among the clarifications:

- Women who have GBS isolated from the urine at any time during pregnancy should undergo intrapartum prophylaxis. They do not need third-trimester screening for GBS.

- Women who had a previous infant with invasive GBS disease should also undergo intrapartum prophylaxis, with no need for third-trimester screening

- All other pregnant women should undergo screening at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation. If results are positive, intrapartum prophylaxis is indicated.

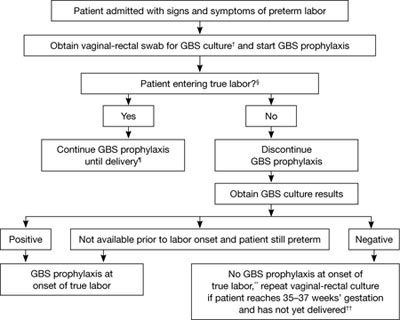

FIGURE 1 Recommended management when a patient experiences preterm labor*

SOURCE: CDC2

*At <37 weeks and 0 days’ gestation.

† If patient has undergone vaginal-rectal GBS culture within the preceding 5 weeks, the results of that culture should guide management. GBS-colonized women should receive intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. No antibiotics are indicated for GBS prophylaxis if a vaginal-rectal screen within 5 weeks was negative.

§ Patient should be regularly assessed for progression to true labor; if the patient is considered not to be in true labor, discontinue GBS prophylaxis.

¶ If GBS culture results become available prior to delivery and are negative, discontinue GBS prophylaxis.

** Unless subsequent GBS culture prior to delivery is positive.

†† A negative GBS screen is considered valid for 5 weeks. If a patient with a history of preterm labor is readmitted with signs and symptoms of preterm labor and had a negative GBS screen >5 weeks earlier, she should be rescreened and managed according to this algorithm at that time.

CDC now offers distinct algorithms for preterm labor and pPROM

To clarify the management of two distinct groups of women, the CDC developed separate algorithms for GBS prophylaxis in the setting of threatened preterm delivery—one for spontaneous preterm labor (FIGURE 1) and another for pPROM (FIGURE 2). In addition, it now recommends:

- When GBS prophylaxis is given to a woman who has signs and symptoms of preterm labor, it should be discontinued if it is later determined that she is not in true labor

- If antibiotics given to prolong latency for pPROM include adequate coverage for GBS (i.e., 2 g intravenous [IV] ampicillin followed by 1 g IV ampicillin every 6 hours for 48 hours), no additional prophylaxis for GBS is necessary, provided delivery occurs during administration of that antibiotic regimen. Oral antibiotics alone are not adequate for GBS prophylaxis.

- When a woman who has pPROM is not in labor and is receiving antibiotics with adequate GBS coverage to prolong latency, she should be managed according to the standard of care for pPROM. GBS testing results should not affect the duration of antibiotics.

- When a woman who has pPROM is not in labor and is not receiving antibiotics to prolong latency (or is receiving antibiotics that do not have adequate GBS coverage), she should undergo GBS prophylaxis for 48 hours unless a GBS screen performed within 5 weeks was negative.

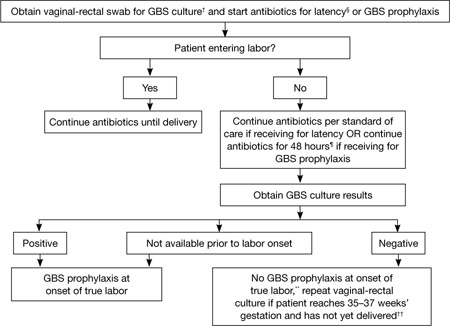

FIGURE 2 GBS screening and prophylaxis for preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM)*

SOURCE: CDC2

* At <37 weeks and 0 days’ gestation.

† If patient has undergone vaginal-rectal GBS culture within the preceding 5 weeks, the results of that culture should guide management. GBS-colonized women should receive intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. No antibiotics are indicated for GBS prophylaxis if a vaginal-rectal screen within 5 weeks was negative.

§ Antibiotics given for latency in the setting of pPROM that include ampicillin 2 g IV once, followed by 1 g IV every 6 hours for at least 48 hours are adequate for GBS prophylaxis. If other regimens are used, GBS prophylaxis should be initiated in addition.

¶ GBS prophylaxis should be discontinued at 48 hours for women with pPROM who are not in labor. If results from a GBS screen performed at admission become available during the 48-hour period and are negative, GBS prophylaxis should be discontinued at that time.

** Unless subsequent GBS culture prior to delivery is positive.

†† A negative GBS screen is considered valid for 5 weeks. If a patient with pPROM is entering labor and had a negative GBS screen >5 weeks earlier, she should be rescreened and managed according to this algorithm at that time.

New dosage allows room for flexibility

The CDC now recommends a dosage of 5 million units of IV penicillin G for GBS prophylaxis, followed by 2.5 to 3.0 million units IV every 4 hours. The range of 2.5 to 3.0 million units is recommended to ensure that the drug reaches an adequate concentration in the fetal circulation and amniotic fluid without being neurotoxic. The choice of dosage within that range should be guided by which formulations of penicillin G are readily available, says the CDC.

Penicillin remains the agent of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis, but ampicillin is an acceptable alternative.

If a woman is allergic to penicillin but has no history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria following administration of a penicillin or cephalosporin, she should be given 2 g IV cefazolin, followed by 1 g IV cefazolin every 8 hours until delivery. If she does have a history of anaphylaxis or is at high risk for anaphylaxis, ask the laboratory for antimicrobial susceptibility testing on the antenatal GBS culture. If the isolate is susceptible to clindamycin, give her 900 mg IV clindamycin every 8 hours until delivery. If it is not susceptible to clindamycin, give her 1 g IV vancomycin every 12 hours until the time of delivery.

The CDC no longer considers erythromycin to be an acceptable alternative for intrapartum GBS prophylaxis for penicillin-allergic women at high risk of anaphylaxis.

Where we go from here

Although early-onset GBS disease has become relatively uncommon, the rate of maternal GBS colonization remains unchanged since the 1970s. Therefore, it is important to continue efforts to sustain and improve on the progress that has been made. There is also a need to monitor for potential adverse consequences of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, such as emergence of bacterial antimicrobial resistance or an increased incidence or severity of nonGBS neonatal pathogens, the CDC observes. “In the absence of a licensed GBS vaccine, universal screening and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis continue to be the cornerstones of early-onset GBS disease prevention."

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Neonatal death from group B strep

(Medical Verdicts, March 2011)

Before widespread intrapartum prophylaxis against group B Streptococcus (GBS) was initiated in the late 1990s, roughly 7,500 newborns developed invasive GBS disease every year in the United States, and the case-fatality rate reached an astonishing—and disheartening—50%.1 Now that all pregnant women undergo culture-based screening at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation, the incidence of early-onset neonatal GBS disease has declined precipitously.

According to a report issued late last year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), GBS now causes roughly 1,200 cases of early-onset invasive disease every year, approximately 70% of them among infants born at or after 37 weeks’ gestation, and the case-fatality rate is 4% to 6%.2 Mortality is higher among preterm infants, with a case-fatality rate of 20% to 30% for infants born at or before 33 weeks’ gestation, compared with 2% to 3% for full-term infants.2

Despite progress, GBS remains the leading cause of early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States. In November 2010, to spur further improvement, the CDC updated its guidelines on prevention of perinatal GBS, and ACOG and other professional organizations endorsed the new recommendations. This article highlights changes to the guidelines—the first since 2002—in four critical areas:

- clarification of who should receive GBS prophylaxis, and when

- updated algorithms for screening and intrapartum prophylaxis for women who experience preterm labor or pre-term premature rupture of membranes (pPROM)

- new recommended dosage of penicillin G for prophylaxis

- updated regimens for prophylaxis among women who are allergic to penicillin.2

When is intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis indicated? When is it not?

| Indicated | Not indicated |

|---|---|

Previous infant with invasive GBS disease GBS bacteriuria during any trimester of the current pregnancy* Positive GBS vaginal-rectal screening culture in late gestation† during current pregnancy* Unknown GBS status at the onset of labor (culture not done, incomplete, or results unknown) and any of the following:

| Colonization with GBS during a previous pregnancy (unless an indication for GBS prophylaxis is present for current pregnancy) GBS bacteriuria during previous pregnancy (unless an indication for GBS prophylaxis is present for current pregnancy) Negative vaginal and rectal GBS screening culture in late gestation† during the current pregnancy, regardless of intrapartum risk factors Cesarean delivery performed before onset of labor on a woman who has intact amniotic membranes, regardless of GBS colonization status or gestational age |

| SOURCE: CDC2 * Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is not indicated in this circumstance if a cesarean delivery is performed before onset of labor on a woman who has intact amniotic membranes. † Optimal timing for prenatal GBS screening is at 35–37 weeks’ gestation. § Recommendations for the use of intrapartum antibiotics for prevention of early-onset GBS disease in the setting of threatened preterm delivery are presented in FIGURES 1 and 2. ¶ If amnionitis is suspected, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy that includes an agent known to be active against GBS should replace GBS prophylaxis. ** NAAT testing for GBS is optional and might not be available in all settings. If intrapartum NAAT is negative for GBS but any other intrapartum risk factor (delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation, amniotic membrane rupture at ≥18 hours, or temperature ≥100.4°F [≥38.0°C]) is present, then intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated. | |

Who should receive prophylaxis?

In its report, the CDC reiterated the indications and “nonindications” for intrapartum prophylaxis (TABLE). Among the clarifications:

- Women who have GBS isolated from the urine at any time during pregnancy should undergo intrapartum prophylaxis. They do not need third-trimester screening for GBS.

- Women who had a previous infant with invasive GBS disease should also undergo intrapartum prophylaxis, with no need for third-trimester screening

- All other pregnant women should undergo screening at 35 to 37 weeks’ gestation. If results are positive, intrapartum prophylaxis is indicated.

FIGURE 1 Recommended management when a patient experiences preterm labor*

SOURCE: CDC2

*At <37 weeks and 0 days’ gestation.

† If patient has undergone vaginal-rectal GBS culture within the preceding 5 weeks, the results of that culture should guide management. GBS-colonized women should receive intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. No antibiotics are indicated for GBS prophylaxis if a vaginal-rectal screen within 5 weeks was negative.

§ Patient should be regularly assessed for progression to true labor; if the patient is considered not to be in true labor, discontinue GBS prophylaxis.

¶ If GBS culture results become available prior to delivery and are negative, discontinue GBS prophylaxis.

** Unless subsequent GBS culture prior to delivery is positive.

†† A negative GBS screen is considered valid for 5 weeks. If a patient with a history of preterm labor is readmitted with signs and symptoms of preterm labor and had a negative GBS screen >5 weeks earlier, she should be rescreened and managed according to this algorithm at that time.

CDC now offers distinct algorithms for preterm labor and pPROM

To clarify the management of two distinct groups of women, the CDC developed separate algorithms for GBS prophylaxis in the setting of threatened preterm delivery—one for spontaneous preterm labor (FIGURE 1) and another for pPROM (FIGURE 2). In addition, it now recommends:

- When GBS prophylaxis is given to a woman who has signs and symptoms of preterm labor, it should be discontinued if it is later determined that she is not in true labor

- If antibiotics given to prolong latency for pPROM include adequate coverage for GBS (i.e., 2 g intravenous [IV] ampicillin followed by 1 g IV ampicillin every 6 hours for 48 hours), no additional prophylaxis for GBS is necessary, provided delivery occurs during administration of that antibiotic regimen. Oral antibiotics alone are not adequate for GBS prophylaxis.

- When a woman who has pPROM is not in labor and is receiving antibiotics with adequate GBS coverage to prolong latency, she should be managed according to the standard of care for pPROM. GBS testing results should not affect the duration of antibiotics.

- When a woman who has pPROM is not in labor and is not receiving antibiotics to prolong latency (or is receiving antibiotics that do not have adequate GBS coverage), she should undergo GBS prophylaxis for 48 hours unless a GBS screen performed within 5 weeks was negative.

FIGURE 2 GBS screening and prophylaxis for preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM)*

SOURCE: CDC2

* At <37 weeks and 0 days’ gestation.

† If patient has undergone vaginal-rectal GBS culture within the preceding 5 weeks, the results of that culture should guide management. GBS-colonized women should receive intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. No antibiotics are indicated for GBS prophylaxis if a vaginal-rectal screen within 5 weeks was negative.

§ Antibiotics given for latency in the setting of pPROM that include ampicillin 2 g IV once, followed by 1 g IV every 6 hours for at least 48 hours are adequate for GBS prophylaxis. If other regimens are used, GBS prophylaxis should be initiated in addition.

¶ GBS prophylaxis should be discontinued at 48 hours for women with pPROM who are not in labor. If results from a GBS screen performed at admission become available during the 48-hour period and are negative, GBS prophylaxis should be discontinued at that time.

** Unless subsequent GBS culture prior to delivery is positive.

†† A negative GBS screen is considered valid for 5 weeks. If a patient with pPROM is entering labor and had a negative GBS screen >5 weeks earlier, she should be rescreened and managed according to this algorithm at that time.

New dosage allows room for flexibility

The CDC now recommends a dosage of 5 million units of IV penicillin G for GBS prophylaxis, followed by 2.5 to 3.0 million units IV every 4 hours. The range of 2.5 to 3.0 million units is recommended to ensure that the drug reaches an adequate concentration in the fetal circulation and amniotic fluid without being neurotoxic. The choice of dosage within that range should be guided by which formulations of penicillin G are readily available, says the CDC.

Penicillin remains the agent of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis, but ampicillin is an acceptable alternative.

If a woman is allergic to penicillin but has no history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria following administration of a penicillin or cephalosporin, she should be given 2 g IV cefazolin, followed by 1 g IV cefazolin every 8 hours until delivery. If she does have a history of anaphylaxis or is at high risk for anaphylaxis, ask the laboratory for antimicrobial susceptibility testing on the antenatal GBS culture. If the isolate is susceptible to clindamycin, give her 900 mg IV clindamycin every 8 hours until delivery. If it is not susceptible to clindamycin, give her 1 g IV vancomycin every 12 hours until the time of delivery.

The CDC no longer considers erythromycin to be an acceptable alternative for intrapartum GBS prophylaxis for penicillin-allergic women at high risk of anaphylaxis.

Where we go from here

Although early-onset GBS disease has become relatively uncommon, the rate of maternal GBS colonization remains unchanged since the 1970s. Therefore, it is important to continue efforts to sustain and improve on the progress that has been made. There is also a need to monitor for potential adverse consequences of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, such as emergence of bacterial antimicrobial resistance or an increased incidence or severity of nonGBS neonatal pathogens, the CDC observes. “In the absence of a licensed GBS vaccine, universal screening and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis continue to be the cornerstones of early-onset GBS disease prevention."

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Baker CJ, Barrett FF. Group B streptococcal infections in infants. The importance of the various serotypes. JAMA. 1974;230(8):1158-1160.

2. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease: Revised Guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(RR-10):1-36.

1. Baker CJ, Barrett FF. Group B streptococcal infections in infants. The importance of the various serotypes. JAMA. 1974;230(8):1158-1160.

2. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease: Revised Guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(RR-10):1-36.