User login

Nitrous oxide, a colorless, odorless gas, has long been used for labor analgesia in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, throughout Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Recently, interest in its use in the United States has increased, since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 of simple devices for administration of nitrous oxide in a variety of locations. Being able to offer an alternative technique, other than parenteral opioids, for women who may not wish to or who cannot have regional analgesia, and for women who have delivered and need analgesia for postdelivery repair, conveys significant benefits. Risks to its use are very low, although the quality of pain relief is inferior to that offered by regional analgesic techniques. Our experience with its use since 2014 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, corroborates that reported in the literature and leads us to continue offering inhaled nitrous oxide and advocating that others do as well.1–7 When using nitrous oxide in your labor and delivery unit, or if considering its use, keep the following points in mind.

A successful inhaled nitrous oxide program requires proper patient selection

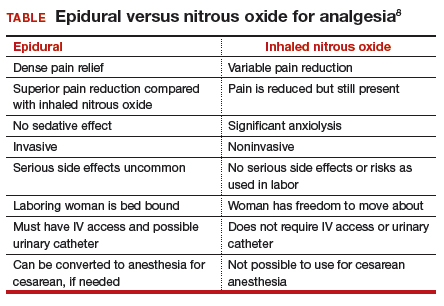

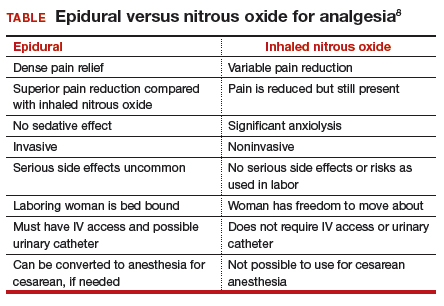

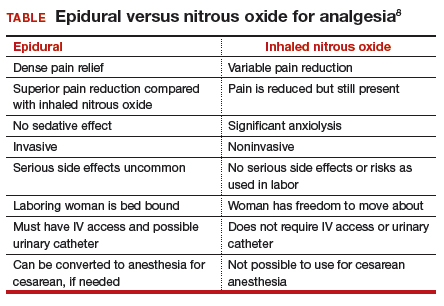

Inhaled nitrous oxide is not an epidural (TABLE).8 The pain relief is clearly inferior to that of an epidural. Inhaled nitrous oxide will not replace epidurals or even have any effect on the epidural rate at a particular institution.6 However, the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia has a long track record of safety (albeit with moderate efficacy for selected patients) for many years in many countries around the world. Inhaled nitrous oxide is a valuable addition to the options we can offer patients:

- who are poor responders to opioid medication or who have high opioid tolerance

- with certain disorders of coagulation

- with chronic pain or anxiety

- who for other reasons need to consider alternatives or adjuncts to neuraxial analgesia.

Although it is important to be realistic regarding the expectations of analgesia quality offered by this agent,7 compared with other agents we have tried, it has less adverse effects, is economically reasonable, and has no proven impact on neonatal outcomes.

No significant complications with inhaled nitrous oxide have been reported

Systematic reviews did not report any significant complications to either mother or newborn.1,2 Our personal experiences corroborate this, as no complications have been associated with its frequent use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Reported adverse effects are mild. The incidence of nausea is 13%, dizziness is 3% to 5%, and drowsiness is 4%; these rates are hard to detect over the baseline rates of those side effects associated with labor and delivery alone.1 Many other centers have now adopted the use of this agent, with several hundred locations now offering inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia in the United States.

Practical use of inhaled nitrous oxide is relatively simple

Several vendors offer portable, user-friendly, cost-effective equipment that is appropriate for labor and delivery use. All devices are structured in demand-valve modality, meaning that the patient must initiate a breath in order to open a valve that allows gas to flow. Cessation of the inspiratory effort closes the valve, thus preventing the free flow of gas into the ambient atmosphere of the room. The devices generally include a tank with nitrous oxide as well as a source of oxygen. Most devices designed for labor and delivery provide a fixed mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, with fail-safe mechanisms to allow increased oxygen delivery in the event of failure or depletion of the nitrous supply. All modern, FDA–approved devices include effective scavenging systems, such that expired gases are vented outside (generally via room suction), which prevents occupational exposure to low levels of nitrous oxide.

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain must be patient controlled

An essential feature of the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia is that it must be considered a patient-controlled system. Patients have an option to use either a mask or a mouthpiece, according to their preferences and comfort. The patient must hold the mask or mouthpiece herself; it is neither appropriate nor safe for anyone else, such as a nurse, family member, or labor support personnel, to assist with this task.

Some coordination with the nurse is essential for optimal timing of administration. Onset of a therapeutic level of pain relief is generally 30 to 60 seconds after inhalation has begun, with rapid resolution after cessation of the inhalation. The patient should thus initiate the inspiration of the gas at the earliest signs of onset of a contraction, so as to achieve maximal analgesia at the peak of the contraction. Waiting until the peak of the contraction to initiate inhalation of the nitrous oxide will not provide effective analgesia, yet will result in sedation after the contraction has ended.

Read about patient satisfaction with inhaled nitrous oxide.

No oversight by an anesthesiologist is required

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produced a clarification statement for definitions of “anesthesia services” (42 CFR 482.52)9 that may be offered by a hospital, based on American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) definitions. CMS, consistent with ASA guidelines, does not define moderate or conscious sedation as “anesthesia,” thus direct oversight by an anesthesiologist is not required. Furthermore, the definition of “minimal sedation,” which is where 50% concentration delivery of inhaled nitrous oxide would be categorized, also does not meet this requirement by CMS.

Women who use inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain typically are satisfied with its use

The use of analog pain scale measurements may not be appropriate in a setting where dissociation from pain might be the primary beneficial effect. Measurements of maternal satisfaction with their analgesic experience support this. The experiences at Vanderbilt University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital show that, while pain relief is limited, like reported in systematic reviews, maternal satisfaction scores for labor analgesia are not different among women who receive inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia, neuraxial analgesia, and those who transition from nitrous to neuraxial analgesia. In fact, published evidence supports extraordinarily high satisfaction in women who plan to use inhaled nitrous oxide, and actually successfully do so, despite only limited degrees of pain relief.10,11 Work to identify the characteristics of women who report success with inhaled nitrous oxide use needs to be performed so that patients can be better selected and informed when making analgesic choices.

Animal research on inhaled nitrous oxide may not translate well to human neonates

A very recent task force convened by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) addressed some of the potential concerns about inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia.12 Per their report:

“the potential teratogenic effect of N2O observed in experimental models cannot be extrapolated to humans. There is a lack of evidence for an association between N2O and reproductive toxicity. The incidence of health hazards and abortion was not shown to be higher in women exposed to, or spouses of men exposed to N2O than those who were not so exposed. Moreover, the incidence of congenital malformations was not higher among women who received N2O for anaesthesia during the first trimester of pregnancy nor during anaesthesia management for cervical cerclage, nor for surgery in the first two trimesters of pregnancy.”

There is a theoretical concern of an increase in neuronal apoptosis in neonates, demonstrated in laboratory animals in anesthetic concentrations, but the human relevance of this is not clear, since the data on animal developmental neurotoxicity is generally combined with data wherein potent inhalational anesthetic agents were also used, not nitrous oxide alone.13 The analgesic doses and time of exposure of inhaled nitrous oxide administered for labor analgesia are well below those required for these changes, as subanesthetic doses are associated with minimal changes, if any, in laboratory animals.

No labor analgesic is without the potential for fetal effects, and alternative labor analgesics such as systemic opioids in higher doses also may have potential adverse effects on the fetus, such as fetal heart rate effects or early tone, alertness, and breastfeeding difficulties. The low solubility and short half-life of inhaled nitrous oxide contribute to low absorption by tissues, thus contributing to the safety of this agent. Nitrous oxide via inhalation for sedation during elective cesarean has been reported to show no adverse effects on neonatal Apgar scores.14

Modern equipment keeps occupational exposure to nitrous oxide safe

One retrospective review of women exposed to high concentrations of inhaled nitrous oxide reported reduced fertility.15 However, the only effects on fertility were seen when nitrous was used without scavenging equipment, and in high concentrations. Moreover, that study examined dental offices, where nitrous was free flowing during procedures—quite a different setting than the intermittent inhalation, demand-valve modality as is used during labor—and when using appropriate modern, FDA-approved equipment, and scavenging devices. Per the recent ESA task force12:

“Members of the task force agreed that, despite theoretical concerns and laboratory data, there is no evidence indicating that the use of N2O in a clinically relevant setting would increase health risk in patients or providers exposed to this drug. With the ubiquitous availability of scavenging systems in the modern operating room, the health concern for medical staff has decreased dramatically. Properly operating scavenging systems reduce N2O concentrations by more than 70%, thereby efficiently keeping ambient N2O levels well below official limits.”

The ESA task force concludes: “An extensive amount of clinical evidence indicates that N2O can be used safely for procedural pain management, for labour pain, and for anxiolysis and sedation in dentistry.”12

Two important reminders

Inhaled nitrous oxide has been a central component of the labor pain relief menu in most of the rest of the world for decades, and the safety record is impeccable. This agent has now had extensive and growing experience in American maternity units. Remember 2 critical points: 1) patient selection is key, 2) analgesia is not like that provided by regional anesthetic techniques such as an epidural.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Likis FE, Andrews JC, Collins MR, et al. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):153-167.

- Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl nature):S110-S126.

- Angle P, Landy CK, Charles C. Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):468-478.

- Migliaccio L, Lawton R, Leeman L, Holbrook A. Initiating intrapartum nitrous oxide in an academic hospital: considerations and challenges. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):358-362.

- Markley JC, Rollins MD. Non-neuraxial labor analgesia: options. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(2);350-364.

- Bobb LE, Farber MK, McGovern C, Camann W. Does nitrous oxide labor analgesia influence the pattern of neuraxial analgesia usage? An impact study at an academic medical center. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:54-57.

- Sutton CD, Butwick AJ, Riley ET, Carvalho B. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: utilization and predictors of conversion to neuraxial analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:40-45.

- Collins MR, Starr SA, Bishop JT, Baysinger CL. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: expanding analgesic options for women in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(3-4):e126-e131.

- 42 CFR 482.52 - Condition of participation: Anesthesia services. US Government Publishing Office website. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec482-52. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Richardson MG, Lopez BM, Baysinger CL, Shotwell MS, Chestnut DH. Nitrous oxide during labor: maternal satisfaction does not depend exclusively on analgesic effectiveness. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):548-553.

- Camann W. Pain, pain relief, satisfaction, and excellence in obstetric anesthesia: a surprisingly complex relationship. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):383-385.

- European Society of Anaesthesiology Task Force on Use of Nitrous Oxide in Clinical Anaesthetic Practice. The current place of nitrous oxide in clinical practice: an expert opinion-based task force consensus statement of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(8):517-520.

- Rappaport B, Mellon RD, Simone A, Woodcock J. Defining safe use of anesthesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1387-1390.

- Vallejo MC, Phelps AL, Shepherd CJ, Kaul B, Mandell GL, Ramanathan S. Nitrous oxide anxiolysis for elective cesarean section. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(7):543-548.

- Rowland AS, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, et al. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):993-997.

Nitrous oxide, a colorless, odorless gas, has long been used for labor analgesia in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, throughout Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Recently, interest in its use in the United States has increased, since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 of simple devices for administration of nitrous oxide in a variety of locations. Being able to offer an alternative technique, other than parenteral opioids, for women who may not wish to or who cannot have regional analgesia, and for women who have delivered and need analgesia for postdelivery repair, conveys significant benefits. Risks to its use are very low, although the quality of pain relief is inferior to that offered by regional analgesic techniques. Our experience with its use since 2014 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, corroborates that reported in the literature and leads us to continue offering inhaled nitrous oxide and advocating that others do as well.1–7 When using nitrous oxide in your labor and delivery unit, or if considering its use, keep the following points in mind.

A successful inhaled nitrous oxide program requires proper patient selection

Inhaled nitrous oxide is not an epidural (TABLE).8 The pain relief is clearly inferior to that of an epidural. Inhaled nitrous oxide will not replace epidurals or even have any effect on the epidural rate at a particular institution.6 However, the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia has a long track record of safety (albeit with moderate efficacy for selected patients) for many years in many countries around the world. Inhaled nitrous oxide is a valuable addition to the options we can offer patients:

- who are poor responders to opioid medication or who have high opioid tolerance

- with certain disorders of coagulation

- with chronic pain or anxiety

- who for other reasons need to consider alternatives or adjuncts to neuraxial analgesia.

Although it is important to be realistic regarding the expectations of analgesia quality offered by this agent,7 compared with other agents we have tried, it has less adverse effects, is economically reasonable, and has no proven impact on neonatal outcomes.

No significant complications with inhaled nitrous oxide have been reported

Systematic reviews did not report any significant complications to either mother or newborn.1,2 Our personal experiences corroborate this, as no complications have been associated with its frequent use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Reported adverse effects are mild. The incidence of nausea is 13%, dizziness is 3% to 5%, and drowsiness is 4%; these rates are hard to detect over the baseline rates of those side effects associated with labor and delivery alone.1 Many other centers have now adopted the use of this agent, with several hundred locations now offering inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia in the United States.

Practical use of inhaled nitrous oxide is relatively simple

Several vendors offer portable, user-friendly, cost-effective equipment that is appropriate for labor and delivery use. All devices are structured in demand-valve modality, meaning that the patient must initiate a breath in order to open a valve that allows gas to flow. Cessation of the inspiratory effort closes the valve, thus preventing the free flow of gas into the ambient atmosphere of the room. The devices generally include a tank with nitrous oxide as well as a source of oxygen. Most devices designed for labor and delivery provide a fixed mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, with fail-safe mechanisms to allow increased oxygen delivery in the event of failure or depletion of the nitrous supply. All modern, FDA–approved devices include effective scavenging systems, such that expired gases are vented outside (generally via room suction), which prevents occupational exposure to low levels of nitrous oxide.

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain must be patient controlled

An essential feature of the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia is that it must be considered a patient-controlled system. Patients have an option to use either a mask or a mouthpiece, according to their preferences and comfort. The patient must hold the mask or mouthpiece herself; it is neither appropriate nor safe for anyone else, such as a nurse, family member, or labor support personnel, to assist with this task.

Some coordination with the nurse is essential for optimal timing of administration. Onset of a therapeutic level of pain relief is generally 30 to 60 seconds after inhalation has begun, with rapid resolution after cessation of the inhalation. The patient should thus initiate the inspiration of the gas at the earliest signs of onset of a contraction, so as to achieve maximal analgesia at the peak of the contraction. Waiting until the peak of the contraction to initiate inhalation of the nitrous oxide will not provide effective analgesia, yet will result in sedation after the contraction has ended.

Read about patient satisfaction with inhaled nitrous oxide.

No oversight by an anesthesiologist is required

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produced a clarification statement for definitions of “anesthesia services” (42 CFR 482.52)9 that may be offered by a hospital, based on American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) definitions. CMS, consistent with ASA guidelines, does not define moderate or conscious sedation as “anesthesia,” thus direct oversight by an anesthesiologist is not required. Furthermore, the definition of “minimal sedation,” which is where 50% concentration delivery of inhaled nitrous oxide would be categorized, also does not meet this requirement by CMS.

Women who use inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain typically are satisfied with its use

The use of analog pain scale measurements may not be appropriate in a setting where dissociation from pain might be the primary beneficial effect. Measurements of maternal satisfaction with their analgesic experience support this. The experiences at Vanderbilt University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital show that, while pain relief is limited, like reported in systematic reviews, maternal satisfaction scores for labor analgesia are not different among women who receive inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia, neuraxial analgesia, and those who transition from nitrous to neuraxial analgesia. In fact, published evidence supports extraordinarily high satisfaction in women who plan to use inhaled nitrous oxide, and actually successfully do so, despite only limited degrees of pain relief.10,11 Work to identify the characteristics of women who report success with inhaled nitrous oxide use needs to be performed so that patients can be better selected and informed when making analgesic choices.

Animal research on inhaled nitrous oxide may not translate well to human neonates

A very recent task force convened by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) addressed some of the potential concerns about inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia.12 Per their report:

“the potential teratogenic effect of N2O observed in experimental models cannot be extrapolated to humans. There is a lack of evidence for an association between N2O and reproductive toxicity. The incidence of health hazards and abortion was not shown to be higher in women exposed to, or spouses of men exposed to N2O than those who were not so exposed. Moreover, the incidence of congenital malformations was not higher among women who received N2O for anaesthesia during the first trimester of pregnancy nor during anaesthesia management for cervical cerclage, nor for surgery in the first two trimesters of pregnancy.”

There is a theoretical concern of an increase in neuronal apoptosis in neonates, demonstrated in laboratory animals in anesthetic concentrations, but the human relevance of this is not clear, since the data on animal developmental neurotoxicity is generally combined with data wherein potent inhalational anesthetic agents were also used, not nitrous oxide alone.13 The analgesic doses and time of exposure of inhaled nitrous oxide administered for labor analgesia are well below those required for these changes, as subanesthetic doses are associated with minimal changes, if any, in laboratory animals.

No labor analgesic is without the potential for fetal effects, and alternative labor analgesics such as systemic opioids in higher doses also may have potential adverse effects on the fetus, such as fetal heart rate effects or early tone, alertness, and breastfeeding difficulties. The low solubility and short half-life of inhaled nitrous oxide contribute to low absorption by tissues, thus contributing to the safety of this agent. Nitrous oxide via inhalation for sedation during elective cesarean has been reported to show no adverse effects on neonatal Apgar scores.14

Modern equipment keeps occupational exposure to nitrous oxide safe

One retrospective review of women exposed to high concentrations of inhaled nitrous oxide reported reduced fertility.15 However, the only effects on fertility were seen when nitrous was used without scavenging equipment, and in high concentrations. Moreover, that study examined dental offices, where nitrous was free flowing during procedures—quite a different setting than the intermittent inhalation, demand-valve modality as is used during labor—and when using appropriate modern, FDA-approved equipment, and scavenging devices. Per the recent ESA task force12:

“Members of the task force agreed that, despite theoretical concerns and laboratory data, there is no evidence indicating that the use of N2O in a clinically relevant setting would increase health risk in patients or providers exposed to this drug. With the ubiquitous availability of scavenging systems in the modern operating room, the health concern for medical staff has decreased dramatically. Properly operating scavenging systems reduce N2O concentrations by more than 70%, thereby efficiently keeping ambient N2O levels well below official limits.”

The ESA task force concludes: “An extensive amount of clinical evidence indicates that N2O can be used safely for procedural pain management, for labour pain, and for anxiolysis and sedation in dentistry.”12

Two important reminders

Inhaled nitrous oxide has been a central component of the labor pain relief menu in most of the rest of the world for decades, and the safety record is impeccable. This agent has now had extensive and growing experience in American maternity units. Remember 2 critical points: 1) patient selection is key, 2) analgesia is not like that provided by regional anesthetic techniques such as an epidural.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Nitrous oxide, a colorless, odorless gas, has long been used for labor analgesia in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, throughout Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Recently, interest in its use in the United States has increased, since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 of simple devices for administration of nitrous oxide in a variety of locations. Being able to offer an alternative technique, other than parenteral opioids, for women who may not wish to or who cannot have regional analgesia, and for women who have delivered and need analgesia for postdelivery repair, conveys significant benefits. Risks to its use are very low, although the quality of pain relief is inferior to that offered by regional analgesic techniques. Our experience with its use since 2014 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, corroborates that reported in the literature and leads us to continue offering inhaled nitrous oxide and advocating that others do as well.1–7 When using nitrous oxide in your labor and delivery unit, or if considering its use, keep the following points in mind.

A successful inhaled nitrous oxide program requires proper patient selection

Inhaled nitrous oxide is not an epidural (TABLE).8 The pain relief is clearly inferior to that of an epidural. Inhaled nitrous oxide will not replace epidurals or even have any effect on the epidural rate at a particular institution.6 However, the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia has a long track record of safety (albeit with moderate efficacy for selected patients) for many years in many countries around the world. Inhaled nitrous oxide is a valuable addition to the options we can offer patients:

- who are poor responders to opioid medication or who have high opioid tolerance

- with certain disorders of coagulation

- with chronic pain or anxiety

- who for other reasons need to consider alternatives or adjuncts to neuraxial analgesia.

Although it is important to be realistic regarding the expectations of analgesia quality offered by this agent,7 compared with other agents we have tried, it has less adverse effects, is economically reasonable, and has no proven impact on neonatal outcomes.

No significant complications with inhaled nitrous oxide have been reported

Systematic reviews did not report any significant complications to either mother or newborn.1,2 Our personal experiences corroborate this, as no complications have been associated with its frequent use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Reported adverse effects are mild. The incidence of nausea is 13%, dizziness is 3% to 5%, and drowsiness is 4%; these rates are hard to detect over the baseline rates of those side effects associated with labor and delivery alone.1 Many other centers have now adopted the use of this agent, with several hundred locations now offering inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia in the United States.

Practical use of inhaled nitrous oxide is relatively simple

Several vendors offer portable, user-friendly, cost-effective equipment that is appropriate for labor and delivery use. All devices are structured in demand-valve modality, meaning that the patient must initiate a breath in order to open a valve that allows gas to flow. Cessation of the inspiratory effort closes the valve, thus preventing the free flow of gas into the ambient atmosphere of the room. The devices generally include a tank with nitrous oxide as well as a source of oxygen. Most devices designed for labor and delivery provide a fixed mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, with fail-safe mechanisms to allow increased oxygen delivery in the event of failure or depletion of the nitrous supply. All modern, FDA–approved devices include effective scavenging systems, such that expired gases are vented outside (generally via room suction), which prevents occupational exposure to low levels of nitrous oxide.

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain must be patient controlled

An essential feature of the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia is that it must be considered a patient-controlled system. Patients have an option to use either a mask or a mouthpiece, according to their preferences and comfort. The patient must hold the mask or mouthpiece herself; it is neither appropriate nor safe for anyone else, such as a nurse, family member, or labor support personnel, to assist with this task.

Some coordination with the nurse is essential for optimal timing of administration. Onset of a therapeutic level of pain relief is generally 30 to 60 seconds after inhalation has begun, with rapid resolution after cessation of the inhalation. The patient should thus initiate the inspiration of the gas at the earliest signs of onset of a contraction, so as to achieve maximal analgesia at the peak of the contraction. Waiting until the peak of the contraction to initiate inhalation of the nitrous oxide will not provide effective analgesia, yet will result in sedation after the contraction has ended.

Read about patient satisfaction with inhaled nitrous oxide.

No oversight by an anesthesiologist is required

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produced a clarification statement for definitions of “anesthesia services” (42 CFR 482.52)9 that may be offered by a hospital, based on American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) definitions. CMS, consistent with ASA guidelines, does not define moderate or conscious sedation as “anesthesia,” thus direct oversight by an anesthesiologist is not required. Furthermore, the definition of “minimal sedation,” which is where 50% concentration delivery of inhaled nitrous oxide would be categorized, also does not meet this requirement by CMS.

Women who use inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain typically are satisfied with its use

The use of analog pain scale measurements may not be appropriate in a setting where dissociation from pain might be the primary beneficial effect. Measurements of maternal satisfaction with their analgesic experience support this. The experiences at Vanderbilt University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital show that, while pain relief is limited, like reported in systematic reviews, maternal satisfaction scores for labor analgesia are not different among women who receive inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia, neuraxial analgesia, and those who transition from nitrous to neuraxial analgesia. In fact, published evidence supports extraordinarily high satisfaction in women who plan to use inhaled nitrous oxide, and actually successfully do so, despite only limited degrees of pain relief.10,11 Work to identify the characteristics of women who report success with inhaled nitrous oxide use needs to be performed so that patients can be better selected and informed when making analgesic choices.

Animal research on inhaled nitrous oxide may not translate well to human neonates

A very recent task force convened by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) addressed some of the potential concerns about inhaled nitrous oxide analgesia.12 Per their report:

“the potential teratogenic effect of N2O observed in experimental models cannot be extrapolated to humans. There is a lack of evidence for an association between N2O and reproductive toxicity. The incidence of health hazards and abortion was not shown to be higher in women exposed to, or spouses of men exposed to N2O than those who were not so exposed. Moreover, the incidence of congenital malformations was not higher among women who received N2O for anaesthesia during the first trimester of pregnancy nor during anaesthesia management for cervical cerclage, nor for surgery in the first two trimesters of pregnancy.”

There is a theoretical concern of an increase in neuronal apoptosis in neonates, demonstrated in laboratory animals in anesthetic concentrations, but the human relevance of this is not clear, since the data on animal developmental neurotoxicity is generally combined with data wherein potent inhalational anesthetic agents were also used, not nitrous oxide alone.13 The analgesic doses and time of exposure of inhaled nitrous oxide administered for labor analgesia are well below those required for these changes, as subanesthetic doses are associated with minimal changes, if any, in laboratory animals.

No labor analgesic is without the potential for fetal effects, and alternative labor analgesics such as systemic opioids in higher doses also may have potential adverse effects on the fetus, such as fetal heart rate effects or early tone, alertness, and breastfeeding difficulties. The low solubility and short half-life of inhaled nitrous oxide contribute to low absorption by tissues, thus contributing to the safety of this agent. Nitrous oxide via inhalation for sedation during elective cesarean has been reported to show no adverse effects on neonatal Apgar scores.14

Modern equipment keeps occupational exposure to nitrous oxide safe

One retrospective review of women exposed to high concentrations of inhaled nitrous oxide reported reduced fertility.15 However, the only effects on fertility were seen when nitrous was used without scavenging equipment, and in high concentrations. Moreover, that study examined dental offices, where nitrous was free flowing during procedures—quite a different setting than the intermittent inhalation, demand-valve modality as is used during labor—and when using appropriate modern, FDA-approved equipment, and scavenging devices. Per the recent ESA task force12:

“Members of the task force agreed that, despite theoretical concerns and laboratory data, there is no evidence indicating that the use of N2O in a clinically relevant setting would increase health risk in patients or providers exposed to this drug. With the ubiquitous availability of scavenging systems in the modern operating room, the health concern for medical staff has decreased dramatically. Properly operating scavenging systems reduce N2O concentrations by more than 70%, thereby efficiently keeping ambient N2O levels well below official limits.”

The ESA task force concludes: “An extensive amount of clinical evidence indicates that N2O can be used safely for procedural pain management, for labour pain, and for anxiolysis and sedation in dentistry.”12

Two important reminders

Inhaled nitrous oxide has been a central component of the labor pain relief menu in most of the rest of the world for decades, and the safety record is impeccable. This agent has now had extensive and growing experience in American maternity units. Remember 2 critical points: 1) patient selection is key, 2) analgesia is not like that provided by regional anesthetic techniques such as an epidural.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Likis FE, Andrews JC, Collins MR, et al. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):153-167.

- Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl nature):S110-S126.

- Angle P, Landy CK, Charles C. Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):468-478.

- Migliaccio L, Lawton R, Leeman L, Holbrook A. Initiating intrapartum nitrous oxide in an academic hospital: considerations and challenges. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):358-362.

- Markley JC, Rollins MD. Non-neuraxial labor analgesia: options. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(2);350-364.

- Bobb LE, Farber MK, McGovern C, Camann W. Does nitrous oxide labor analgesia influence the pattern of neuraxial analgesia usage? An impact study at an academic medical center. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:54-57.

- Sutton CD, Butwick AJ, Riley ET, Carvalho B. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: utilization and predictors of conversion to neuraxial analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:40-45.

- Collins MR, Starr SA, Bishop JT, Baysinger CL. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: expanding analgesic options for women in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(3-4):e126-e131.

- 42 CFR 482.52 - Condition of participation: Anesthesia services. US Government Publishing Office website. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec482-52. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Richardson MG, Lopez BM, Baysinger CL, Shotwell MS, Chestnut DH. Nitrous oxide during labor: maternal satisfaction does not depend exclusively on analgesic effectiveness. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):548-553.

- Camann W. Pain, pain relief, satisfaction, and excellence in obstetric anesthesia: a surprisingly complex relationship. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):383-385.

- European Society of Anaesthesiology Task Force on Use of Nitrous Oxide in Clinical Anaesthetic Practice. The current place of nitrous oxide in clinical practice: an expert opinion-based task force consensus statement of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(8):517-520.

- Rappaport B, Mellon RD, Simone A, Woodcock J. Defining safe use of anesthesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1387-1390.

- Vallejo MC, Phelps AL, Shepherd CJ, Kaul B, Mandell GL, Ramanathan S. Nitrous oxide anxiolysis for elective cesarean section. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(7):543-548.

- Rowland AS, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, et al. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):993-997.

- Likis FE, Andrews JC, Collins MR, et al. Nitrous oxide for the management of labor pain: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(1):153-167.

- Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 suppl nature):S110-S126.

- Angle P, Landy CK, Charles C. Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):468-478.

- Migliaccio L, Lawton R, Leeman L, Holbrook A. Initiating intrapartum nitrous oxide in an academic hospital: considerations and challenges. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):358-362.

- Markley JC, Rollins MD. Non-neuraxial labor analgesia: options. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(2);350-364.

- Bobb LE, Farber MK, McGovern C, Camann W. Does nitrous oxide labor analgesia influence the pattern of neuraxial analgesia usage? An impact study at an academic medical center. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:54-57.

- Sutton CD, Butwick AJ, Riley ET, Carvalho B. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: utilization and predictors of conversion to neuraxial analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2017;40:40-45.

- Collins MR, Starr SA, Bishop JT, Baysinger CL. Nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: expanding analgesic options for women in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(3-4):e126-e131.

- 42 CFR 482.52 - Condition of participation: Anesthesia services. US Government Publishing Office website. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec482-52. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- Richardson MG, Lopez BM, Baysinger CL, Shotwell MS, Chestnut DH. Nitrous oxide during labor: maternal satisfaction does not depend exclusively on analgesic effectiveness. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):548-553.

- Camann W. Pain, pain relief, satisfaction, and excellence in obstetric anesthesia: a surprisingly complex relationship. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):383-385.

- European Society of Anaesthesiology Task Force on Use of Nitrous Oxide in Clinical Anaesthetic Practice. The current place of nitrous oxide in clinical practice: an expert opinion-based task force consensus statement of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(8):517-520.

- Rappaport B, Mellon RD, Simone A, Woodcock J. Defining safe use of anesthesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1387-1390.

- Vallejo MC, Phelps AL, Shepherd CJ, Kaul B, Mandell GL, Ramanathan S. Nitrous oxide anxiolysis for elective cesarean section. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(7):543-548.

- Rowland AS, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, et al. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):993-997.