User login

Take-Home Points

- Gorham disease is a rare condition that manifests as an acute, spontaneous osteolysis.

- There is no clear hereditary pattern of transmission. Bones of any type or location can be affected.

- Imaging studies are nonspecific, but show permeative osteolysis involving the subcortical and intramedullary regions and typically affect regional, contiguous bones, without adjacent sclerosis, somewhat resembling osteoporosis.

- Tissue biopsy is indicated to rule out other potential etiologies of osteolysis, and the histologic findings help confirm a diagnosis of Gorham disease.

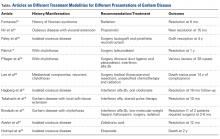

- There is no single or combined treatment modality that is considered as the gold standard. Surgical treatment includes resection of the lesion and reconstruction. Also, antiosteoclastic medication can be used.

Gorham disease, a rare condition of unknown etiology, manifests as acute, spontaneous osteolysis associated with benign hemangiomatosis or lymphangiomatosis, which presents as skeletal lucency on radiographs, prompting the classic eponym of vanishing bone disease.1-6 There is no evidence supporting the idea that osteoclasts are present in any meaningful amount in the resorption areas or that local reparative osteogenesis occurs.4,6

Jackson and colleagues first described idiopathic osteolysis in 1838,1,2 and Gorham and Stout3 introduced the syndrome to the orthopedic community in 1955. Since then, few strides have been made in identifying the disease origin.1,2,4 Diagnosis is possible only after meticulous work-up has excluded neoplastic and infectious etiologies.7,8

Clinical Presentation

Gorham disease affects patients ranging widely in age, from 2 months to 78 years, but typically presents in those under 40 years. There is a questionable predilection for males but no correlation with ethnicity or geographic region. There is no clear hereditary pattern of transmission.7 Although the bones of the head, neck, and upper extremities are involved in most cases, bone of any type or location can be affected.6 Pelvic bones seem to be involved least often.6,7

Initial clinical presentation varies considerably but typically involves prolonged soreness in the affected region and, rarely, acute pathologic fracture.1,2,4 The nonspecific nature of complaints, lack of markers of systemic illness, and rarity of the disease contribute to delayed diagnosis.1,2

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) better defines the severity and extent of these changes.

Magnetic resonance imaging shows an infiltrative and irregular T2 hyperintense signal throughout regions of bone affected by osteolysis, but this finding is not characteristic. There is heterogeneous enhancement on postcontrast sequences, and, though masslike enhancement is absent, signal abnormalities may extend into adjacent soft tissues.

Bone scintigraphy using technetium-99m is similarly nonspecific, typically revealing radiotracer uptake that is consistent with bony reaction to an underlying osteolytic process (Figure 4) but turning negative with ongoing resorption.

Positron emission tomography/CT typically shows foci of increased metabolic activity in the areas of osteolysis.10

Diagnosis

There have been 8 histologic and clinical criteria described to diagnose Gorham disease: (1) biopsy positive for presence of angiomatous tissue, (2) complete absence of any cellular atypia, (3) lack of osteoclastic response and lack of dystrophic calcifications, (4) evidence of progressive resorption of native bone, (5) no evidence of expansive or ulcerative lesion, (6) lack of visceral involvement, (7) osteolytic radiographic pattern, and (8) no concrete diagnosis after hereditary, metabolic, neoplastic, immunologic, and infectious work-up.4-6 These criteria confirm that the diagnosis can be rendered only after exclusion of neoplastic and infectious etiologies through clinical and laboratory work-up, imaging studies, and tissue sampling.

Tissue biopsy is indicated to rule out other potential etiologies of osteolysis, and the histologic findings help confirm a diagnosis of Gorham disease.

The differential diagnosis includes infection (osteomyelitis, Brodie abscess), benign tumors (eosinophilic granuloma/Langerhans cell histiocytosis), malignant tumors (Ewing sarcoma and angiosarcoma), inflammatory conditions (eg, apatite- associated destructive arthritis), endocrine disorders (eg, osteolytic hyperparathyroidism), benign non-neoplastic conditions (venous or venolymphatic malformation), and other syndromes that present with osteolysis.1,2 Nevertheless, progressive and unusually substantial bone destruction without evidence of repair is almost pathognomonic for Gorham disease.9

Treatment

Surgical treatment usually includes lesion resection and subsequent reconstruction using combinations of bone grafts (allogenic) and prostheses. Bone graft alone is quickly resorbed and has not been found to be beneficial.1,2,4,20

1. Saify FY, Gosavi SR. Gorham’s disease: a diagnostic challenge. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(3):411-414.

2. Patel DV. Gorham’s disease or massive osteolysis. Clin Med Res. 2005;3(2):65-74.

3. Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone); its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37(5):985-1004.

4. Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, Feeney JE. Perspectives on massive osteolysis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55(4):331-343.

5. Gulati U, Mohanty S, Dabas J, Chandra N. “Vanishing bone disease” in maxillofacial region: a review and our experience. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(3):548-557.

6. Nikolaou VS, Chytas D, Korres D, Efstathopoulos N. Vanishing bone disease (Gorham-Stout syndrome): a review of a rare entity. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):694-698.

7. Möller G, Priemel M, Amling M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G. The Gorham-Stout syndrome (Gorham’s massive osteolysis). A report of six cases with histopathological findings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(3):501-506.

8. Dominguez R, Washowich TL. Gorham’s disease or vanishing bone disease: plain film, CT, and MRI findings of two cases. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24(5):316-318.

9. Kotecha R, Mascarenhas L, Jackson HA, Venkatramani R. Radiological features of Gorham’s disease. Clin Radiol. 2012;67(8):782-788.

10. Dong A, Bai Y, Wang Y, Zuo C. Bone scan, MRI, and FDG PET/CT findings in composite hemangioendothelioma of the manubrium sterni. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(2):e180-e183.

11. Baulieu F, De Pinieux G, Maruani A, Vaillant L, Lorette G. Serial lymphoscintigraphic findings in a patient with Gorham’s disease with lymphedema. Lymphology. 2014;47(3):118-122.

12. Manisali M, Ozaksoy D. Gorham disease: correlation of MR findings with histopathologic changes. Eur Radiol. 1998;8(9):1647-1650.

13. Brodszki N, Länsberg JK, Dictor M, et al. A novel treatment approach for paediatric Gorham-Stout syndrome with chylothorax. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(11):1448-1453.

14. Nir V, Guralnik L, Livnat G, et al. Propranolol as a treatment option in Gorham-Stout syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(4):417-419.

15. Fontanesi J. Radiation therapy in the treatment of Gorham disease. J Pediatr Hematol. 2003;25(10):816-817.

16. Pfleger A, Schwinger W, Maier A, Tauss J, Popper HH, Zach MS. Gorham-Stout syndrome in a male adolescent—case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28(4):231-233.

17. Patrick JH. Massive osteolysis complicated by chylothorax successfully treated by pleurodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58(3):347-349.

18. Hagberg H, Lamberg K, Åström G. α-2b interferon and oral clodronate for Gorham’s disease. Lancet. 1997;350(9094):1822-1823.

19. Takahashi A, Ogawa C, Kanazawa T, et al. Remission induced by interferon alfa in a patient with massive osteolysis and extension of lymph-hemangiomatosis: a severe case of Gorham-Stout syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(3):E47-E50.

20. Paley MD, Lloyd CJ, Penfold CN. Total mandibular reconstruction for massive osteolysis of the mandible (Gorham-Stout syndrome). Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43(2):166-168.

21. Avelar RL, Martins VB, Antunes AA, de Oliveira Neto PJ, de Souza Andrade ES. Use of zoledronic acid in the treatment of Gorham’s disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(3):319-322.

22. Holroyd I, Dillon M, Roberts GJ. Gorham’s disease: a case (including dental presentation) of vanishing bone disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(1):125-129.

23. Lee S, Finn L, Sze RW, Perkins JA, Sie KC. Gorham Stout syndrome (disappearing bone disease): two additional case reports and a review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(12):1340-1343.

Take-Home Points

- Gorham disease is a rare condition that manifests as an acute, spontaneous osteolysis.

- There is no clear hereditary pattern of transmission. Bones of any type or location can be affected.

- Imaging studies are nonspecific, but show permeative osteolysis involving the subcortical and intramedullary regions and typically affect regional, contiguous bones, without adjacent sclerosis, somewhat resembling osteoporosis.

- Tissue biopsy is indicated to rule out other potential etiologies of osteolysis, and the histologic findings help confirm a diagnosis of Gorham disease.

- There is no single or combined treatment modality that is considered as the gold standard. Surgical treatment includes resection of the lesion and reconstruction. Also, antiosteoclastic medication can be used.

Gorham disease, a rare condition of unknown etiology, manifests as acute, spontaneous osteolysis associated with benign hemangiomatosis or lymphangiomatosis, which presents as skeletal lucency on radiographs, prompting the classic eponym of vanishing bone disease.1-6 There is no evidence supporting the idea that osteoclasts are present in any meaningful amount in the resorption areas or that local reparative osteogenesis occurs.4,6

Jackson and colleagues first described idiopathic osteolysis in 1838,1,2 and Gorham and Stout3 introduced the syndrome to the orthopedic community in 1955. Since then, few strides have been made in identifying the disease origin.1,2,4 Diagnosis is possible only after meticulous work-up has excluded neoplastic and infectious etiologies.7,8

Clinical Presentation

Gorham disease affects patients ranging widely in age, from 2 months to 78 years, but typically presents in those under 40 years. There is a questionable predilection for males but no correlation with ethnicity or geographic region. There is no clear hereditary pattern of transmission.7 Although the bones of the head, neck, and upper extremities are involved in most cases, bone of any type or location can be affected.6 Pelvic bones seem to be involved least often.6,7

Initial clinical presentation varies considerably but typically involves prolonged soreness in the affected region and, rarely, acute pathologic fracture.1,2,4 The nonspecific nature of complaints, lack of markers of systemic illness, and rarity of the disease contribute to delayed diagnosis.1,2

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) better defines the severity and extent of these changes.

Magnetic resonance imaging shows an infiltrative and irregular T2 hyperintense signal throughout regions of bone affected by osteolysis, but this finding is not characteristic. There is heterogeneous enhancement on postcontrast sequences, and, though masslike enhancement is absent, signal abnormalities may extend into adjacent soft tissues.

Bone scintigraphy using technetium-99m is similarly nonspecific, typically revealing radiotracer uptake that is consistent with bony reaction to an underlying osteolytic process (Figure 4) but turning negative with ongoing resorption.

Positron emission tomography/CT typically shows foci of increased metabolic activity in the areas of osteolysis.10

Diagnosis

There have been 8 histologic and clinical criteria described to diagnose Gorham disease: (1) biopsy positive for presence of angiomatous tissue, (2) complete absence of any cellular atypia, (3) lack of osteoclastic response and lack of dystrophic calcifications, (4) evidence of progressive resorption of native bone, (5) no evidence of expansive or ulcerative lesion, (6) lack of visceral involvement, (7) osteolytic radiographic pattern, and (8) no concrete diagnosis after hereditary, metabolic, neoplastic, immunologic, and infectious work-up.4-6 These criteria confirm that the diagnosis can be rendered only after exclusion of neoplastic and infectious etiologies through clinical and laboratory work-up, imaging studies, and tissue sampling.

Tissue biopsy is indicated to rule out other potential etiologies of osteolysis, and the histologic findings help confirm a diagnosis of Gorham disease.

The differential diagnosis includes infection (osteomyelitis, Brodie abscess), benign tumors (eosinophilic granuloma/Langerhans cell histiocytosis), malignant tumors (Ewing sarcoma and angiosarcoma), inflammatory conditions (eg, apatite- associated destructive arthritis), endocrine disorders (eg, osteolytic hyperparathyroidism), benign non-neoplastic conditions (venous or venolymphatic malformation), and other syndromes that present with osteolysis.1,2 Nevertheless, progressive and unusually substantial bone destruction without evidence of repair is almost pathognomonic for Gorham disease.9

Treatment

Surgical treatment usually includes lesion resection and subsequent reconstruction using combinations of bone grafts (allogenic) and prostheses. Bone graft alone is quickly resorbed and has not been found to be beneficial.1,2,4,20

Take-Home Points

- Gorham disease is a rare condition that manifests as an acute, spontaneous osteolysis.

- There is no clear hereditary pattern of transmission. Bones of any type or location can be affected.

- Imaging studies are nonspecific, but show permeative osteolysis involving the subcortical and intramedullary regions and typically affect regional, contiguous bones, without adjacent sclerosis, somewhat resembling osteoporosis.

- Tissue biopsy is indicated to rule out other potential etiologies of osteolysis, and the histologic findings help confirm a diagnosis of Gorham disease.

- There is no single or combined treatment modality that is considered as the gold standard. Surgical treatment includes resection of the lesion and reconstruction. Also, antiosteoclastic medication can be used.

Gorham disease, a rare condition of unknown etiology, manifests as acute, spontaneous osteolysis associated with benign hemangiomatosis or lymphangiomatosis, which presents as skeletal lucency on radiographs, prompting the classic eponym of vanishing bone disease.1-6 There is no evidence supporting the idea that osteoclasts are present in any meaningful amount in the resorption areas or that local reparative osteogenesis occurs.4,6

Jackson and colleagues first described idiopathic osteolysis in 1838,1,2 and Gorham and Stout3 introduced the syndrome to the orthopedic community in 1955. Since then, few strides have been made in identifying the disease origin.1,2,4 Diagnosis is possible only after meticulous work-up has excluded neoplastic and infectious etiologies.7,8

Clinical Presentation

Gorham disease affects patients ranging widely in age, from 2 months to 78 years, but typically presents in those under 40 years. There is a questionable predilection for males but no correlation with ethnicity or geographic region. There is no clear hereditary pattern of transmission.7 Although the bones of the head, neck, and upper extremities are involved in most cases, bone of any type or location can be affected.6 Pelvic bones seem to be involved least often.6,7

Initial clinical presentation varies considerably but typically involves prolonged soreness in the affected region and, rarely, acute pathologic fracture.1,2,4 The nonspecific nature of complaints, lack of markers of systemic illness, and rarity of the disease contribute to delayed diagnosis.1,2

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) better defines the severity and extent of these changes.

Magnetic resonance imaging shows an infiltrative and irregular T2 hyperintense signal throughout regions of bone affected by osteolysis, but this finding is not characteristic. There is heterogeneous enhancement on postcontrast sequences, and, though masslike enhancement is absent, signal abnormalities may extend into adjacent soft tissues.

Bone scintigraphy using technetium-99m is similarly nonspecific, typically revealing radiotracer uptake that is consistent with bony reaction to an underlying osteolytic process (Figure 4) but turning negative with ongoing resorption.

Positron emission tomography/CT typically shows foci of increased metabolic activity in the areas of osteolysis.10

Diagnosis

There have been 8 histologic and clinical criteria described to diagnose Gorham disease: (1) biopsy positive for presence of angiomatous tissue, (2) complete absence of any cellular atypia, (3) lack of osteoclastic response and lack of dystrophic calcifications, (4) evidence of progressive resorption of native bone, (5) no evidence of expansive or ulcerative lesion, (6) lack of visceral involvement, (7) osteolytic radiographic pattern, and (8) no concrete diagnosis after hereditary, metabolic, neoplastic, immunologic, and infectious work-up.4-6 These criteria confirm that the diagnosis can be rendered only after exclusion of neoplastic and infectious etiologies through clinical and laboratory work-up, imaging studies, and tissue sampling.

Tissue biopsy is indicated to rule out other potential etiologies of osteolysis, and the histologic findings help confirm a diagnosis of Gorham disease.

The differential diagnosis includes infection (osteomyelitis, Brodie abscess), benign tumors (eosinophilic granuloma/Langerhans cell histiocytosis), malignant tumors (Ewing sarcoma and angiosarcoma), inflammatory conditions (eg, apatite- associated destructive arthritis), endocrine disorders (eg, osteolytic hyperparathyroidism), benign non-neoplastic conditions (venous or venolymphatic malformation), and other syndromes that present with osteolysis.1,2 Nevertheless, progressive and unusually substantial bone destruction without evidence of repair is almost pathognomonic for Gorham disease.9

Treatment

Surgical treatment usually includes lesion resection and subsequent reconstruction using combinations of bone grafts (allogenic) and prostheses. Bone graft alone is quickly resorbed and has not been found to be beneficial.1,2,4,20

1. Saify FY, Gosavi SR. Gorham’s disease: a diagnostic challenge. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(3):411-414.

2. Patel DV. Gorham’s disease or massive osteolysis. Clin Med Res. 2005;3(2):65-74.

3. Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone); its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37(5):985-1004.

4. Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, Feeney JE. Perspectives on massive osteolysis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55(4):331-343.

5. Gulati U, Mohanty S, Dabas J, Chandra N. “Vanishing bone disease” in maxillofacial region: a review and our experience. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(3):548-557.

6. Nikolaou VS, Chytas D, Korres D, Efstathopoulos N. Vanishing bone disease (Gorham-Stout syndrome): a review of a rare entity. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):694-698.

7. Möller G, Priemel M, Amling M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G. The Gorham-Stout syndrome (Gorham’s massive osteolysis). A report of six cases with histopathological findings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(3):501-506.

8. Dominguez R, Washowich TL. Gorham’s disease or vanishing bone disease: plain film, CT, and MRI findings of two cases. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24(5):316-318.

9. Kotecha R, Mascarenhas L, Jackson HA, Venkatramani R. Radiological features of Gorham’s disease. Clin Radiol. 2012;67(8):782-788.

10. Dong A, Bai Y, Wang Y, Zuo C. Bone scan, MRI, and FDG PET/CT findings in composite hemangioendothelioma of the manubrium sterni. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(2):e180-e183.

11. Baulieu F, De Pinieux G, Maruani A, Vaillant L, Lorette G. Serial lymphoscintigraphic findings in a patient with Gorham’s disease with lymphedema. Lymphology. 2014;47(3):118-122.

12. Manisali M, Ozaksoy D. Gorham disease: correlation of MR findings with histopathologic changes. Eur Radiol. 1998;8(9):1647-1650.

13. Brodszki N, Länsberg JK, Dictor M, et al. A novel treatment approach for paediatric Gorham-Stout syndrome with chylothorax. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(11):1448-1453.

14. Nir V, Guralnik L, Livnat G, et al. Propranolol as a treatment option in Gorham-Stout syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(4):417-419.

15. Fontanesi J. Radiation therapy in the treatment of Gorham disease. J Pediatr Hematol. 2003;25(10):816-817.

16. Pfleger A, Schwinger W, Maier A, Tauss J, Popper HH, Zach MS. Gorham-Stout syndrome in a male adolescent—case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28(4):231-233.

17. Patrick JH. Massive osteolysis complicated by chylothorax successfully treated by pleurodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58(3):347-349.

18. Hagberg H, Lamberg K, Åström G. α-2b interferon and oral clodronate for Gorham’s disease. Lancet. 1997;350(9094):1822-1823.

19. Takahashi A, Ogawa C, Kanazawa T, et al. Remission induced by interferon alfa in a patient with massive osteolysis and extension of lymph-hemangiomatosis: a severe case of Gorham-Stout syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(3):E47-E50.

20. Paley MD, Lloyd CJ, Penfold CN. Total mandibular reconstruction for massive osteolysis of the mandible (Gorham-Stout syndrome). Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43(2):166-168.

21. Avelar RL, Martins VB, Antunes AA, de Oliveira Neto PJ, de Souza Andrade ES. Use of zoledronic acid in the treatment of Gorham’s disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(3):319-322.

22. Holroyd I, Dillon M, Roberts GJ. Gorham’s disease: a case (including dental presentation) of vanishing bone disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(1):125-129.

23. Lee S, Finn L, Sze RW, Perkins JA, Sie KC. Gorham Stout syndrome (disappearing bone disease): two additional case reports and a review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(12):1340-1343.

1. Saify FY, Gosavi SR. Gorham’s disease: a diagnostic challenge. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(3):411-414.

2. Patel DV. Gorham’s disease or massive osteolysis. Clin Med Res. 2005;3(2):65-74.

3. Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone); its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37(5):985-1004.

4. Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, Feeney JE. Perspectives on massive osteolysis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55(4):331-343.

5. Gulati U, Mohanty S, Dabas J, Chandra N. “Vanishing bone disease” in maxillofacial region: a review and our experience. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(3):548-557.

6. Nikolaou VS, Chytas D, Korres D, Efstathopoulos N. Vanishing bone disease (Gorham-Stout syndrome): a review of a rare entity. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):694-698.

7. Möller G, Priemel M, Amling M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G. The Gorham-Stout syndrome (Gorham’s massive osteolysis). A report of six cases with histopathological findings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(3):501-506.

8. Dominguez R, Washowich TL. Gorham’s disease or vanishing bone disease: plain film, CT, and MRI findings of two cases. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24(5):316-318.

9. Kotecha R, Mascarenhas L, Jackson HA, Venkatramani R. Radiological features of Gorham’s disease. Clin Radiol. 2012;67(8):782-788.

10. Dong A, Bai Y, Wang Y, Zuo C. Bone scan, MRI, and FDG PET/CT findings in composite hemangioendothelioma of the manubrium sterni. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(2):e180-e183.

11. Baulieu F, De Pinieux G, Maruani A, Vaillant L, Lorette G. Serial lymphoscintigraphic findings in a patient with Gorham’s disease with lymphedema. Lymphology. 2014;47(3):118-122.

12. Manisali M, Ozaksoy D. Gorham disease: correlation of MR findings with histopathologic changes. Eur Radiol. 1998;8(9):1647-1650.

13. Brodszki N, Länsberg JK, Dictor M, et al. A novel treatment approach for paediatric Gorham-Stout syndrome with chylothorax. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(11):1448-1453.

14. Nir V, Guralnik L, Livnat G, et al. Propranolol as a treatment option in Gorham-Stout syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(4):417-419.

15. Fontanesi J. Radiation therapy in the treatment of Gorham disease. J Pediatr Hematol. 2003;25(10):816-817.

16. Pfleger A, Schwinger W, Maier A, Tauss J, Popper HH, Zach MS. Gorham-Stout syndrome in a male adolescent—case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28(4):231-233.

17. Patrick JH. Massive osteolysis complicated by chylothorax successfully treated by pleurodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58(3):347-349.

18. Hagberg H, Lamberg K, Åström G. α-2b interferon and oral clodronate for Gorham’s disease. Lancet. 1997;350(9094):1822-1823.

19. Takahashi A, Ogawa C, Kanazawa T, et al. Remission induced by interferon alfa in a patient with massive osteolysis and extension of lymph-hemangiomatosis: a severe case of Gorham-Stout syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(3):E47-E50.

20. Paley MD, Lloyd CJ, Penfold CN. Total mandibular reconstruction for massive osteolysis of the mandible (Gorham-Stout syndrome). Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43(2):166-168.

21. Avelar RL, Martins VB, Antunes AA, de Oliveira Neto PJ, de Souza Andrade ES. Use of zoledronic acid in the treatment of Gorham’s disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(3):319-322.

22. Holroyd I, Dillon M, Roberts GJ. Gorham’s disease: a case (including dental presentation) of vanishing bone disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(1):125-129.

23. Lee S, Finn L, Sze RW, Perkins JA, Sie KC. Gorham Stout syndrome (disappearing bone disease): two additional case reports and a review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(12):1340-1343.