User login

Fatigue and depression can be viewed as a “vicious cycle”: Fatigue can be a symptom of major depression, and fatigue can be a risk factor for depression.1 For example, fatigue associated with a general medical condition or traumatic brain injury can be a risk factor for developing major depressive disorder (MDD).1-3 It isn’t surprising that fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD.

Despite the observed association between fatigue and depression, their underlying relationship often is unclear. The literature does not differentiate among fatigue associated with depression, fatigue as a treatment-emergent adverse effect, and fatigue as a residual symptom of depression that is partially responsive to treatment.4,5 To complicate the situation, many medications used to treat MDD can cause fatigue.

Patients often describe fatigue as (1) feeling tired, exhausted, or drained and (2) lacking energy and motivation. Fatigue can be related to impaired wakefulness but is believed to be a different entity than sleepiness.6 Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health.

We reviewed the literature about fatigue as a symptom of MDD by conducting a search of Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using keywords depression, fatigue, residual symptoms, and treatment. We chose the papers cited in this article based on our consensus and because these publications represent expert opinion or the highest quality evidence available.

Residual fatigue has an effect on prognosis

Fatigue is a common symptom of MDD that persists in 20% to 30% of patients whose symptoms of depression otherwise remit.4,7-9 Several studies have linked residual fatigue with the overall prognosis of MDD.5 Data from a prospective study demonstrate that depressed patients have a higher risk of relapse when they continue to report symptoms of fatigue after their symptoms of depression have otherwise entered partial remission.10 Another study demonstrated that the severity of residual symptoms of depression is a strong predictor of another major depressive episode.11

In a large-scale study, the prevalence of residual fatigue after adequate treatment of MDD in both partial responders and remitters was 84.6%.12 The same study showed that one-third of patients who had been treated for MDD had persistent and clinically significant fatigue, which could suggest a relationship between fatigue and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants.

Another study demonstrated that 64.6% of patients who responded to antidepressant treatment and who had baseline fatigue continued to exhibit symptoms of fatigue after an adequate trial of an antidepressant.13

Neurobiological considerations

Studies have shown that the neuronal circuits that malfunction in fatigue are different from those that malfunction in depression.14 Although the neurobiology of fatigue has not been determined, decreased neuronal activity in the prefrontal circuits has been associated with symptoms of fatigue.15

In addition, evidence from the literature shows a decrease in hormone secretion16 and cognitive abilities in patients exhibiting symptoms of fatigue.17 These findings have led some experts to hypothesize that symptoms of fatigue associated with depression could be the result of (1) immune dysregulation18 and (2) an inability of available antidepressants to target the underlying biology of the disorder.2

Despite the hypothesis that fatigue associated with depression might be biologically related to immune dysregulation, some authors continue to point to an imbalance in neurotransmitters—norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, acetylcholine—as being associated with fatigue.14 For example, a study demonstrated that drugs targeting noradrenergic reuptake inhibition were more effective at preventing a relapse of fatigue compared with serotonergic drugs.19 Another study showed improvement in energy with an increase in the plasma level of desipramine, which affects noradrenergic neurotransmission.20

Inflammatory cytokines also have been explored in the search for an understanding of the etiology of fatigue and depression.21 Physical and mental stress promote the release of cytokines, which activate the immune system by inducing an inflammatory response; this response has been etiologically linked to depressive disorders.22 Furthermore, studies have demonstrated an elevated level of inflammatory cytokines in patients who have MDD— suggesting that MDD is associated with a chronic low level of inflammation that crosses the blood−brain barrier.23

Clinical considerations: A role for rating scales?

Despite the significance of residual fatigue on the quality of life of patients who have MDD, most common rating scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale24 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale,25 have limited sensitivity for measuring fatigue.26 The Fatigue Associated with Depression (FAsD)27 questionnaire, designed according to FDA guidelines,28 is used to assess fatigue associated with depression. The final version of the FAsD includes 13 items: a 6-item experience subscale and a 7-item impact subscale.

Is the FAsD helpful? The experience subscale of the FAsD assesses how often the patient experiences different aspects of fatigue (tiredness, exhaustion, lack of energy, physical weakness, and a feeling that everything requires too much effort). The impact subscale of the FAsD assesses the effect of fatigue on daily life.

The overall FAsD score is calculated by taking the mean of each subscale; a change of 0.67 on the experience subscale and 0.57 on the impact subscale are considered clinically meaningful.27 The measurement properties of the questionnaire showed internal consistency, reliability, and validity in testing. Researchers note, however, that FAsD does not include items to assess the impact of fatigue on cognition. This means that the FAsD might not distinguish between physical and mental aspects of fatigue.

Treatment

It isn’t surprising that residual depression can increase health care utilization and economic burden, including such indirect costs as lost productivity and wages.29 Despite these impacts, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the relationship between residual symptoms, such as fatigue, and work productivity. It has been established that improving a depressed patient’s level of energy correlates with improved performance at work.

Treating fatigue as a residual symptom of MDD can be complicated because symptoms of fatigue might be:

• a discrete symptom of MDD

• a prodromal symptom of another disorder

• an adverse effect of an antidepressant.2,30

It is a major clinical problem, therefore, that antidepressants can alleviate and cause symptoms of fatigue.31 Treatment strategy should focus on identifying antidepressants that are less likely to cause fatigue (ie, noradrenergic or dopaminergic drugs, or both). Adjunctive treatments to target residual fatigue also can be used.32

There are limited published data on the effective treatment of residual fatigue in patients with MDD. Given the absence of sufficient evidence, agents that promote noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission have been the treatment of choice when targeting fatigue in depressed patients.2,14,21,33

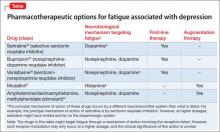

The Table34-37 lists potential treatment options often used to treat fatigue associated with depression.

SSRIs. Treatment with SSRIs has been associated with a low probability of achieving remission when targeting fatigue as a symptom of MDD.21

One study reported that, after 8 weeks of treatment with an SSRI, treatment-emergent adverse events, such as worsening fatigue and weakness, were observed—along with an overall lack of efficacy in targeting all symptoms of depression.38

Another study demonstrated positive effects when a noradrenergic agent was added to an SSRI in partial responders who continued to complain of residual fatigue.33

However, studies that compared the effects of SSRIs with those of antidepressants that have pronoradrenergic effects showed that the 2 mechanisms of action were not significantly different from each other in their ability to resolve residual symptoms of fatigue.21 A limiting factor might be that these studies were retrospective and did not analyze the efficacy of a noradrenergic agent as an adjunct for alleviating symptoms of fatigue.39

Bupropion. This commonly used medication for fatigue is believed to cause a significantly lower level of fatigue compared with SSRIs.40 The potential utility of bupropion in this area could be a reflection of its mechanism of action—ie, the drug targets both noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission.41

A study comparing bupropion with SSRIs in targeting somatic symptoms of depression reported a small but statistically significant difference in favor of the bupropion-treated group. However, this finding was confounded by the small effect size and difficulty quantifying somatic symptoms.40

Stimulants and modafinil. Psycho-stimulants have been shown to be efficacious for depression and fatigue, both as monotherapy and adjunctively.39,42

Modafinil has demonstrated efficacy in open-label trials for improving residual fatigue, but failed to separate from placebo in controlled trials.43 At least 1 other failed study has been published examining modafinil as a treatment for fatigue associated with depression.43

Adjunctive therapy with CNS stimulants, such as amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, has been used to treat fatigue, with positive results.16 Modafinil and stimulants also could be tried as an augmentation strategy to other antidepressants; such use is off-label and should be attempted only after careful consideration.16

Exercise might be a nonpharmacotherapeutic modality that targets the underlying physiology associated with fatigue. Exercise releases endorphins, which can affect overall brain chemistry and which have been theorized to diminish symptoms of fatigue and depression.44 Consider exercise in addition to treatment with an antidepressant in selected patients.45

To sum up

In general, the literature does not recommend one medication as superior to any other for treating fatigue that is a residual symptom of depression. Such hesitation suggests that more empirical studies are needed to determine what is the best and proper management of treating fatigue associated with depression.

Bottom LinE

Fatigue can be a symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) or a risk factor for depression. Fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD. Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health and can result in increased utilization of health care services. A number of treatment options are available; none has been shown to be superior to the others.

Related Resources

• Leone SS. A disabling combination: fatigue and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):86-87.

• Targum SD, Fava M. Fatigue as a residual symptom of depression. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):40-43.

• Illiades C. How to fight depression fatigue. Everyday Health. http://www.everydayhealth.com/health-report/major-depression-living-well/fight-depression-fatigue.aspx.

• Kerr M. Depression and fatigue: a vicious cycle. Healthline. http://www.healthline.com/health/depression/fatigue.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Desipramine • Norpramin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Modafinil • Provigil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Sohail reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Macaluso has conducted clinical trials research as principal investigator for the following pharmaceutical manufacturers in the past 12 months: AbbVie, Inc.; Alkermes; AssureRx Health, Inc.; Eisai Co., Ltd.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Naurex Inc. All clinical trial and study contracts were with, and payments were made to, University of Kansas Medical Center Research Institute, Kansas City, Kansas, a research institute affiliated with University of Kansas School of Medicine−Wichita.

1. Schönberger M, Herrberg M, Ponsford J. Fatigue as a cause, not a consequence of depression and daytime sleepiness: a cross-lagged analysis. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(5):427-431.

2. Demyttenaere K, De Fruyt J, Stahl, SM. The many faces of fatigue in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):93-105.

3. Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Mavreas V. Temporal relations between unexplained fatigue and depression: longitudinal data from an international study in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):330-335.

4. Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):41-50.

5. Kennedy N, Paykel ES. Residual symptoms at remission from depression: impact on long-term outcome. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):135-144.

6. Shen J, Barbera J, Shapiro CM. Distinguishing sleepiness and fatigue: focus on definition and measurement. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:63-76.

7. Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):221-225.

8. Tylee A, Gastpar M, Lépine JP, et al. DEPRES II (Depression Research in European Society II): a patient survey of the symptoms, disability and current management of depression in the community. DEPRES Steering Committee. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(3):139-151.

9. Marcus SM, Young EA, Kerber KB, et al. Gender differences in depression: findings from the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):141-150.

10. Paykel ES, Ramana, R, Cooper Z, et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1171-1180.

11. Bockting CL, Spinhoven P, Koeter MW, et al; Depression Evaluation Longitudinal Therapy Assessment Study Group. Prediction of recurrence in recurrent depression and the influence of consecutive episodes on vulnerability for depression: a 2-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):747-755.

12. Greco T, Eckert G, Kroenke K. The outcome of physical symptoms with treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):813-818.

13. McClintock SM, Husain MM, Wisniewski SR, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):180-186.

14. Stahl SM, Zhang L, Damatarca C, et al. Brain circuits determine destiny in depression: a novel approach to the psychopharmacology of wakefulness, fatigue, and executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):6-17.

15. MacHale SM, Law´rie SM, Cavanagh JT, et al. Cerebral perfusion in chronic fatigue syndrome and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:550-556.

16. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

17. van den Heuvel OA, Groenewegen HJ, Barkhof F, et al. Frontostriatal system in planning complexity: a parametric functional magnetic resonance version of Tower of London task. Neuroimage. 2003;18(2):367-374.

18. Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Glaser R, et al. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(8):1310-1317.

19. Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):411-418.

20. Nelson JC, Mazure C, Quinlan DM, et al. Drug-responsive symptoms in melancholia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(7):663-668.

21. Fava M, Ball S, Nelson, JC, et al. Clinical relevance of fatigue as a residual symptom in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(3):250-257.

22. Anisman H, Merali Z, Poulter MO, et al. Cytokines as a precipitant of depressive illness: animal and human studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(8):963-972.

23. Simon NM, McNamara K, Chow CW, et al. A detailed examination of cytokine abnormalities in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(3):230-233.

24. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

25. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382-389.

26. Matza LS, Phillips GA, Revicki DA, et al. Development and validation of a patient-report measure of fatigue associated with depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):294-303.

27. Matza LS, Wyrwich KW, Phillips GA, et al. The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD): responsiveness and responder definition. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(2):351-360.

28. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda. gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Published December 2009. Accessed May 7, 2015.

29. Knoth RL, Bolge SC, Kim E, et al. Effect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):e188-e196.

30. Fava M. Symptoms of fatigue and cognitive/executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder before and after antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):30-34.

31. Chang T, Fava M. The future of psychopharmacology of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(8):971-975.

32. Baldwin DS, Papakostas GI. Symptoms of fatigue and sleepiness in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):9-15.

33. Ball SG, Dellva MA, D’Souza D, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of augmentation with LY2216684 for major depressive disorder patients who are partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [abstract P 05]. Int J Psych Clin Pract. 2010;14(suppl 1):19.

34. Stahl SM. Using secondary binding properties to select a not so elective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(12):642-643.

35. Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

36. Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(5):699-711.

37. Scammell TE, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, et al. Hypothalamic arousal regions are activated during modafinil-induced wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2000;20(22):8620-8628.

38. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, et al. The relationship between adverse events during selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for major depressive disorder and nonremission in the suicide assessment methodology study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):31-38.

39. Nelson JC. A review of the efficacy of serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors for treatment of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1301-1308.

40. Papakostas GI, Nutt DJ, Hallett LA, et al. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1350-1355.

41. Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, et al. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):106-113.

42. Candy M, Jones CB, Williams R, et al. Psychostimulants for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006722.pub2.

43. Lam JY, Freeman MK, Cates ME. Modafinil augmentation for residual symptoms of fatigue in patients with a partial response to antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(6):1005-1012.

44. Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clinical Psychol Rev. 2001;21(1):33-61.

45. Trivedi MH, Greer TL, Grannemann BD, et al. Exercise as an augmentation strategy for treatment of major depression. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(4):205-213.

Fatigue and depression can be viewed as a “vicious cycle”: Fatigue can be a symptom of major depression, and fatigue can be a risk factor for depression.1 For example, fatigue associated with a general medical condition or traumatic brain injury can be a risk factor for developing major depressive disorder (MDD).1-3 It isn’t surprising that fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD.

Despite the observed association between fatigue and depression, their underlying relationship often is unclear. The literature does not differentiate among fatigue associated with depression, fatigue as a treatment-emergent adverse effect, and fatigue as a residual symptom of depression that is partially responsive to treatment.4,5 To complicate the situation, many medications used to treat MDD can cause fatigue.

Patients often describe fatigue as (1) feeling tired, exhausted, or drained and (2) lacking energy and motivation. Fatigue can be related to impaired wakefulness but is believed to be a different entity than sleepiness.6 Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health.

We reviewed the literature about fatigue as a symptom of MDD by conducting a search of Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using keywords depression, fatigue, residual symptoms, and treatment. We chose the papers cited in this article based on our consensus and because these publications represent expert opinion or the highest quality evidence available.

Residual fatigue has an effect on prognosis

Fatigue is a common symptom of MDD that persists in 20% to 30% of patients whose symptoms of depression otherwise remit.4,7-9 Several studies have linked residual fatigue with the overall prognosis of MDD.5 Data from a prospective study demonstrate that depressed patients have a higher risk of relapse when they continue to report symptoms of fatigue after their symptoms of depression have otherwise entered partial remission.10 Another study demonstrated that the severity of residual symptoms of depression is a strong predictor of another major depressive episode.11

In a large-scale study, the prevalence of residual fatigue after adequate treatment of MDD in both partial responders and remitters was 84.6%.12 The same study showed that one-third of patients who had been treated for MDD had persistent and clinically significant fatigue, which could suggest a relationship between fatigue and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants.

Another study demonstrated that 64.6% of patients who responded to antidepressant treatment and who had baseline fatigue continued to exhibit symptoms of fatigue after an adequate trial of an antidepressant.13

Neurobiological considerations

Studies have shown that the neuronal circuits that malfunction in fatigue are different from those that malfunction in depression.14 Although the neurobiology of fatigue has not been determined, decreased neuronal activity in the prefrontal circuits has been associated with symptoms of fatigue.15

In addition, evidence from the literature shows a decrease in hormone secretion16 and cognitive abilities in patients exhibiting symptoms of fatigue.17 These findings have led some experts to hypothesize that symptoms of fatigue associated with depression could be the result of (1) immune dysregulation18 and (2) an inability of available antidepressants to target the underlying biology of the disorder.2

Despite the hypothesis that fatigue associated with depression might be biologically related to immune dysregulation, some authors continue to point to an imbalance in neurotransmitters—norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, acetylcholine—as being associated with fatigue.14 For example, a study demonstrated that drugs targeting noradrenergic reuptake inhibition were more effective at preventing a relapse of fatigue compared with serotonergic drugs.19 Another study showed improvement in energy with an increase in the plasma level of desipramine, which affects noradrenergic neurotransmission.20

Inflammatory cytokines also have been explored in the search for an understanding of the etiology of fatigue and depression.21 Physical and mental stress promote the release of cytokines, which activate the immune system by inducing an inflammatory response; this response has been etiologically linked to depressive disorders.22 Furthermore, studies have demonstrated an elevated level of inflammatory cytokines in patients who have MDD— suggesting that MDD is associated with a chronic low level of inflammation that crosses the blood−brain barrier.23

Clinical considerations: A role for rating scales?

Despite the significance of residual fatigue on the quality of life of patients who have MDD, most common rating scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale24 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale,25 have limited sensitivity for measuring fatigue.26 The Fatigue Associated with Depression (FAsD)27 questionnaire, designed according to FDA guidelines,28 is used to assess fatigue associated with depression. The final version of the FAsD includes 13 items: a 6-item experience subscale and a 7-item impact subscale.

Is the FAsD helpful? The experience subscale of the FAsD assesses how often the patient experiences different aspects of fatigue (tiredness, exhaustion, lack of energy, physical weakness, and a feeling that everything requires too much effort). The impact subscale of the FAsD assesses the effect of fatigue on daily life.

The overall FAsD score is calculated by taking the mean of each subscale; a change of 0.67 on the experience subscale and 0.57 on the impact subscale are considered clinically meaningful.27 The measurement properties of the questionnaire showed internal consistency, reliability, and validity in testing. Researchers note, however, that FAsD does not include items to assess the impact of fatigue on cognition. This means that the FAsD might not distinguish between physical and mental aspects of fatigue.

Treatment

It isn’t surprising that residual depression can increase health care utilization and economic burden, including such indirect costs as lost productivity and wages.29 Despite these impacts, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the relationship between residual symptoms, such as fatigue, and work productivity. It has been established that improving a depressed patient’s level of energy correlates with improved performance at work.

Treating fatigue as a residual symptom of MDD can be complicated because symptoms of fatigue might be:

• a discrete symptom of MDD

• a prodromal symptom of another disorder

• an adverse effect of an antidepressant.2,30

It is a major clinical problem, therefore, that antidepressants can alleviate and cause symptoms of fatigue.31 Treatment strategy should focus on identifying antidepressants that are less likely to cause fatigue (ie, noradrenergic or dopaminergic drugs, or both). Adjunctive treatments to target residual fatigue also can be used.32

There are limited published data on the effective treatment of residual fatigue in patients with MDD. Given the absence of sufficient evidence, agents that promote noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission have been the treatment of choice when targeting fatigue in depressed patients.2,14,21,33

The Table34-37 lists potential treatment options often used to treat fatigue associated with depression.

SSRIs. Treatment with SSRIs has been associated with a low probability of achieving remission when targeting fatigue as a symptom of MDD.21

One study reported that, after 8 weeks of treatment with an SSRI, treatment-emergent adverse events, such as worsening fatigue and weakness, were observed—along with an overall lack of efficacy in targeting all symptoms of depression.38

Another study demonstrated positive effects when a noradrenergic agent was added to an SSRI in partial responders who continued to complain of residual fatigue.33

However, studies that compared the effects of SSRIs with those of antidepressants that have pronoradrenergic effects showed that the 2 mechanisms of action were not significantly different from each other in their ability to resolve residual symptoms of fatigue.21 A limiting factor might be that these studies were retrospective and did not analyze the efficacy of a noradrenergic agent as an adjunct for alleviating symptoms of fatigue.39

Bupropion. This commonly used medication for fatigue is believed to cause a significantly lower level of fatigue compared with SSRIs.40 The potential utility of bupropion in this area could be a reflection of its mechanism of action—ie, the drug targets both noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission.41

A study comparing bupropion with SSRIs in targeting somatic symptoms of depression reported a small but statistically significant difference in favor of the bupropion-treated group. However, this finding was confounded by the small effect size and difficulty quantifying somatic symptoms.40

Stimulants and modafinil. Psycho-stimulants have been shown to be efficacious for depression and fatigue, both as monotherapy and adjunctively.39,42

Modafinil has demonstrated efficacy in open-label trials for improving residual fatigue, but failed to separate from placebo in controlled trials.43 At least 1 other failed study has been published examining modafinil as a treatment for fatigue associated with depression.43

Adjunctive therapy with CNS stimulants, such as amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, has been used to treat fatigue, with positive results.16 Modafinil and stimulants also could be tried as an augmentation strategy to other antidepressants; such use is off-label and should be attempted only after careful consideration.16

Exercise might be a nonpharmacotherapeutic modality that targets the underlying physiology associated with fatigue. Exercise releases endorphins, which can affect overall brain chemistry and which have been theorized to diminish symptoms of fatigue and depression.44 Consider exercise in addition to treatment with an antidepressant in selected patients.45

To sum up

In general, the literature does not recommend one medication as superior to any other for treating fatigue that is a residual symptom of depression. Such hesitation suggests that more empirical studies are needed to determine what is the best and proper management of treating fatigue associated with depression.

Bottom LinE

Fatigue can be a symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) or a risk factor for depression. Fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD. Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health and can result in increased utilization of health care services. A number of treatment options are available; none has been shown to be superior to the others.

Related Resources

• Leone SS. A disabling combination: fatigue and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):86-87.

• Targum SD, Fava M. Fatigue as a residual symptom of depression. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):40-43.

• Illiades C. How to fight depression fatigue. Everyday Health. http://www.everydayhealth.com/health-report/major-depression-living-well/fight-depression-fatigue.aspx.

• Kerr M. Depression and fatigue: a vicious cycle. Healthline. http://www.healthline.com/health/depression/fatigue.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Desipramine • Norpramin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Modafinil • Provigil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Sohail reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Macaluso has conducted clinical trials research as principal investigator for the following pharmaceutical manufacturers in the past 12 months: AbbVie, Inc.; Alkermes; AssureRx Health, Inc.; Eisai Co., Ltd.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Naurex Inc. All clinical trial and study contracts were with, and payments were made to, University of Kansas Medical Center Research Institute, Kansas City, Kansas, a research institute affiliated with University of Kansas School of Medicine−Wichita.

Fatigue and depression can be viewed as a “vicious cycle”: Fatigue can be a symptom of major depression, and fatigue can be a risk factor for depression.1 For example, fatigue associated with a general medical condition or traumatic brain injury can be a risk factor for developing major depressive disorder (MDD).1-3 It isn’t surprising that fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD.

Despite the observed association between fatigue and depression, their underlying relationship often is unclear. The literature does not differentiate among fatigue associated with depression, fatigue as a treatment-emergent adverse effect, and fatigue as a residual symptom of depression that is partially responsive to treatment.4,5 To complicate the situation, many medications used to treat MDD can cause fatigue.

Patients often describe fatigue as (1) feeling tired, exhausted, or drained and (2) lacking energy and motivation. Fatigue can be related to impaired wakefulness but is believed to be a different entity than sleepiness.6 Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health.

We reviewed the literature about fatigue as a symptom of MDD by conducting a search of Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using keywords depression, fatigue, residual symptoms, and treatment. We chose the papers cited in this article based on our consensus and because these publications represent expert opinion or the highest quality evidence available.

Residual fatigue has an effect on prognosis

Fatigue is a common symptom of MDD that persists in 20% to 30% of patients whose symptoms of depression otherwise remit.4,7-9 Several studies have linked residual fatigue with the overall prognosis of MDD.5 Data from a prospective study demonstrate that depressed patients have a higher risk of relapse when they continue to report symptoms of fatigue after their symptoms of depression have otherwise entered partial remission.10 Another study demonstrated that the severity of residual symptoms of depression is a strong predictor of another major depressive episode.11

In a large-scale study, the prevalence of residual fatigue after adequate treatment of MDD in both partial responders and remitters was 84.6%.12 The same study showed that one-third of patients who had been treated for MDD had persistent and clinically significant fatigue, which could suggest a relationship between fatigue and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants.

Another study demonstrated that 64.6% of patients who responded to antidepressant treatment and who had baseline fatigue continued to exhibit symptoms of fatigue after an adequate trial of an antidepressant.13

Neurobiological considerations

Studies have shown that the neuronal circuits that malfunction in fatigue are different from those that malfunction in depression.14 Although the neurobiology of fatigue has not been determined, decreased neuronal activity in the prefrontal circuits has been associated with symptoms of fatigue.15

In addition, evidence from the literature shows a decrease in hormone secretion16 and cognitive abilities in patients exhibiting symptoms of fatigue.17 These findings have led some experts to hypothesize that symptoms of fatigue associated with depression could be the result of (1) immune dysregulation18 and (2) an inability of available antidepressants to target the underlying biology of the disorder.2

Despite the hypothesis that fatigue associated with depression might be biologically related to immune dysregulation, some authors continue to point to an imbalance in neurotransmitters—norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, acetylcholine—as being associated with fatigue.14 For example, a study demonstrated that drugs targeting noradrenergic reuptake inhibition were more effective at preventing a relapse of fatigue compared with serotonergic drugs.19 Another study showed improvement in energy with an increase in the plasma level of desipramine, which affects noradrenergic neurotransmission.20

Inflammatory cytokines also have been explored in the search for an understanding of the etiology of fatigue and depression.21 Physical and mental stress promote the release of cytokines, which activate the immune system by inducing an inflammatory response; this response has been etiologically linked to depressive disorders.22 Furthermore, studies have demonstrated an elevated level of inflammatory cytokines in patients who have MDD— suggesting that MDD is associated with a chronic low level of inflammation that crosses the blood−brain barrier.23

Clinical considerations: A role for rating scales?

Despite the significance of residual fatigue on the quality of life of patients who have MDD, most common rating scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale24 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale,25 have limited sensitivity for measuring fatigue.26 The Fatigue Associated with Depression (FAsD)27 questionnaire, designed according to FDA guidelines,28 is used to assess fatigue associated with depression. The final version of the FAsD includes 13 items: a 6-item experience subscale and a 7-item impact subscale.

Is the FAsD helpful? The experience subscale of the FAsD assesses how often the patient experiences different aspects of fatigue (tiredness, exhaustion, lack of energy, physical weakness, and a feeling that everything requires too much effort). The impact subscale of the FAsD assesses the effect of fatigue on daily life.

The overall FAsD score is calculated by taking the mean of each subscale; a change of 0.67 on the experience subscale and 0.57 on the impact subscale are considered clinically meaningful.27 The measurement properties of the questionnaire showed internal consistency, reliability, and validity in testing. Researchers note, however, that FAsD does not include items to assess the impact of fatigue on cognition. This means that the FAsD might not distinguish between physical and mental aspects of fatigue.

Treatment

It isn’t surprising that residual depression can increase health care utilization and economic burden, including such indirect costs as lost productivity and wages.29 Despite these impacts, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the relationship between residual symptoms, such as fatigue, and work productivity. It has been established that improving a depressed patient’s level of energy correlates with improved performance at work.

Treating fatigue as a residual symptom of MDD can be complicated because symptoms of fatigue might be:

• a discrete symptom of MDD

• a prodromal symptom of another disorder

• an adverse effect of an antidepressant.2,30

It is a major clinical problem, therefore, that antidepressants can alleviate and cause symptoms of fatigue.31 Treatment strategy should focus on identifying antidepressants that are less likely to cause fatigue (ie, noradrenergic or dopaminergic drugs, or both). Adjunctive treatments to target residual fatigue also can be used.32

There are limited published data on the effective treatment of residual fatigue in patients with MDD. Given the absence of sufficient evidence, agents that promote noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission have been the treatment of choice when targeting fatigue in depressed patients.2,14,21,33

The Table34-37 lists potential treatment options often used to treat fatigue associated with depression.

SSRIs. Treatment with SSRIs has been associated with a low probability of achieving remission when targeting fatigue as a symptom of MDD.21

One study reported that, after 8 weeks of treatment with an SSRI, treatment-emergent adverse events, such as worsening fatigue and weakness, were observed—along with an overall lack of efficacy in targeting all symptoms of depression.38

Another study demonstrated positive effects when a noradrenergic agent was added to an SSRI in partial responders who continued to complain of residual fatigue.33

However, studies that compared the effects of SSRIs with those of antidepressants that have pronoradrenergic effects showed that the 2 mechanisms of action were not significantly different from each other in their ability to resolve residual symptoms of fatigue.21 A limiting factor might be that these studies were retrospective and did not analyze the efficacy of a noradrenergic agent as an adjunct for alleviating symptoms of fatigue.39

Bupropion. This commonly used medication for fatigue is believed to cause a significantly lower level of fatigue compared with SSRIs.40 The potential utility of bupropion in this area could be a reflection of its mechanism of action—ie, the drug targets both noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission.41

A study comparing bupropion with SSRIs in targeting somatic symptoms of depression reported a small but statistically significant difference in favor of the bupropion-treated group. However, this finding was confounded by the small effect size and difficulty quantifying somatic symptoms.40

Stimulants and modafinil. Psycho-stimulants have been shown to be efficacious for depression and fatigue, both as monotherapy and adjunctively.39,42

Modafinil has demonstrated efficacy in open-label trials for improving residual fatigue, but failed to separate from placebo in controlled trials.43 At least 1 other failed study has been published examining modafinil as a treatment for fatigue associated with depression.43

Adjunctive therapy with CNS stimulants, such as amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, has been used to treat fatigue, with positive results.16 Modafinil and stimulants also could be tried as an augmentation strategy to other antidepressants; such use is off-label and should be attempted only after careful consideration.16

Exercise might be a nonpharmacotherapeutic modality that targets the underlying physiology associated with fatigue. Exercise releases endorphins, which can affect overall brain chemistry and which have been theorized to diminish symptoms of fatigue and depression.44 Consider exercise in addition to treatment with an antidepressant in selected patients.45

To sum up

In general, the literature does not recommend one medication as superior to any other for treating fatigue that is a residual symptom of depression. Such hesitation suggests that more empirical studies are needed to determine what is the best and proper management of treating fatigue associated with depression.

Bottom LinE

Fatigue can be a symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) or a risk factor for depression. Fatigue has been studied as a predictor of relapse after previous response to treatment in patients with MDD. Residual fatigue can affect social, cognitive, emotional, and physical health and can result in increased utilization of health care services. A number of treatment options are available; none has been shown to be superior to the others.

Related Resources

• Leone SS. A disabling combination: fatigue and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):86-87.

• Targum SD, Fava M. Fatigue as a residual symptom of depression. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):40-43.

• Illiades C. How to fight depression fatigue. Everyday Health. http://www.everydayhealth.com/health-report/major-depression-living-well/fight-depression-fatigue.aspx.

• Kerr M. Depression and fatigue: a vicious cycle. Healthline. http://www.healthline.com/health/depression/fatigue.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Desipramine • Norpramin

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Modafinil • Provigil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Sohail reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Macaluso has conducted clinical trials research as principal investigator for the following pharmaceutical manufacturers in the past 12 months: AbbVie, Inc.; Alkermes; AssureRx Health, Inc.; Eisai Co., Ltd.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Naurex Inc. All clinical trial and study contracts were with, and payments were made to, University of Kansas Medical Center Research Institute, Kansas City, Kansas, a research institute affiliated with University of Kansas School of Medicine−Wichita.

1. Schönberger M, Herrberg M, Ponsford J. Fatigue as a cause, not a consequence of depression and daytime sleepiness: a cross-lagged analysis. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(5):427-431.

2. Demyttenaere K, De Fruyt J, Stahl, SM. The many faces of fatigue in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):93-105.

3. Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Mavreas V. Temporal relations between unexplained fatigue and depression: longitudinal data from an international study in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):330-335.

4. Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):41-50.

5. Kennedy N, Paykel ES. Residual symptoms at remission from depression: impact on long-term outcome. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):135-144.

6. Shen J, Barbera J, Shapiro CM. Distinguishing sleepiness and fatigue: focus on definition and measurement. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:63-76.

7. Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):221-225.

8. Tylee A, Gastpar M, Lépine JP, et al. DEPRES II (Depression Research in European Society II): a patient survey of the symptoms, disability and current management of depression in the community. DEPRES Steering Committee. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(3):139-151.

9. Marcus SM, Young EA, Kerber KB, et al. Gender differences in depression: findings from the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):141-150.

10. Paykel ES, Ramana, R, Cooper Z, et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1171-1180.

11. Bockting CL, Spinhoven P, Koeter MW, et al; Depression Evaluation Longitudinal Therapy Assessment Study Group. Prediction of recurrence in recurrent depression and the influence of consecutive episodes on vulnerability for depression: a 2-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):747-755.

12. Greco T, Eckert G, Kroenke K. The outcome of physical symptoms with treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):813-818.

13. McClintock SM, Husain MM, Wisniewski SR, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):180-186.

14. Stahl SM, Zhang L, Damatarca C, et al. Brain circuits determine destiny in depression: a novel approach to the psychopharmacology of wakefulness, fatigue, and executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):6-17.

15. MacHale SM, Law´rie SM, Cavanagh JT, et al. Cerebral perfusion in chronic fatigue syndrome and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:550-556.

16. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

17. van den Heuvel OA, Groenewegen HJ, Barkhof F, et al. Frontostriatal system in planning complexity: a parametric functional magnetic resonance version of Tower of London task. Neuroimage. 2003;18(2):367-374.

18. Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Glaser R, et al. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(8):1310-1317.

19. Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):411-418.

20. Nelson JC, Mazure C, Quinlan DM, et al. Drug-responsive symptoms in melancholia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(7):663-668.

21. Fava M, Ball S, Nelson, JC, et al. Clinical relevance of fatigue as a residual symptom in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(3):250-257.

22. Anisman H, Merali Z, Poulter MO, et al. Cytokines as a precipitant of depressive illness: animal and human studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(8):963-972.

23. Simon NM, McNamara K, Chow CW, et al. A detailed examination of cytokine abnormalities in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(3):230-233.

24. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

25. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382-389.

26. Matza LS, Phillips GA, Revicki DA, et al. Development and validation of a patient-report measure of fatigue associated with depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):294-303.

27. Matza LS, Wyrwich KW, Phillips GA, et al. The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD): responsiveness and responder definition. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(2):351-360.

28. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda. gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Published December 2009. Accessed May 7, 2015.

29. Knoth RL, Bolge SC, Kim E, et al. Effect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):e188-e196.

30. Fava M. Symptoms of fatigue and cognitive/executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder before and after antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):30-34.

31. Chang T, Fava M. The future of psychopharmacology of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(8):971-975.

32. Baldwin DS, Papakostas GI. Symptoms of fatigue and sleepiness in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):9-15.

33. Ball SG, Dellva MA, D’Souza D, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of augmentation with LY2216684 for major depressive disorder patients who are partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [abstract P 05]. Int J Psych Clin Pract. 2010;14(suppl 1):19.

34. Stahl SM. Using secondary binding properties to select a not so elective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(12):642-643.

35. Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

36. Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(5):699-711.

37. Scammell TE, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, et al. Hypothalamic arousal regions are activated during modafinil-induced wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2000;20(22):8620-8628.

38. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, et al. The relationship between adverse events during selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for major depressive disorder and nonremission in the suicide assessment methodology study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):31-38.

39. Nelson JC. A review of the efficacy of serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors for treatment of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1301-1308.

40. Papakostas GI, Nutt DJ, Hallett LA, et al. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1350-1355.

41. Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, et al. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):106-113.

42. Candy M, Jones CB, Williams R, et al. Psychostimulants for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006722.pub2.

43. Lam JY, Freeman MK, Cates ME. Modafinil augmentation for residual symptoms of fatigue in patients with a partial response to antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(6):1005-1012.

44. Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clinical Psychol Rev. 2001;21(1):33-61.

45. Trivedi MH, Greer TL, Grannemann BD, et al. Exercise as an augmentation strategy for treatment of major depression. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(4):205-213.

1. Schönberger M, Herrberg M, Ponsford J. Fatigue as a cause, not a consequence of depression and daytime sleepiness: a cross-lagged analysis. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(5):427-431.

2. Demyttenaere K, De Fruyt J, Stahl, SM. The many faces of fatigue in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(1):93-105.

3. Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Mavreas V. Temporal relations between unexplained fatigue and depression: longitudinal data from an international study in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):330-335.

4. Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):41-50.

5. Kennedy N, Paykel ES. Residual symptoms at remission from depression: impact on long-term outcome. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):135-144.

6. Shen J, Barbera J, Shapiro CM. Distinguishing sleepiness and fatigue: focus on definition and measurement. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:63-76.

7. Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):221-225.

8. Tylee A, Gastpar M, Lépine JP, et al. DEPRES II (Depression Research in European Society II): a patient survey of the symptoms, disability and current management of depression in the community. DEPRES Steering Committee. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(3):139-151.

9. Marcus SM, Young EA, Kerber KB, et al. Gender differences in depression: findings from the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):141-150.

10. Paykel ES, Ramana, R, Cooper Z, et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1171-1180.

11. Bockting CL, Spinhoven P, Koeter MW, et al; Depression Evaluation Longitudinal Therapy Assessment Study Group. Prediction of recurrence in recurrent depression and the influence of consecutive episodes on vulnerability for depression: a 2-year prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):747-755.

12. Greco T, Eckert G, Kroenke K. The outcome of physical symptoms with treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):813-818.

13. McClintock SM, Husain MM, Wisniewski SR, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):180-186.

14. Stahl SM, Zhang L, Damatarca C, et al. Brain circuits determine destiny in depression: a novel approach to the psychopharmacology of wakefulness, fatigue, and executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):6-17.

15. MacHale SM, Law´rie SM, Cavanagh JT, et al. Cerebral perfusion in chronic fatigue syndrome and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:550-556.

16. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

17. van den Heuvel OA, Groenewegen HJ, Barkhof F, et al. Frontostriatal system in planning complexity: a parametric functional magnetic resonance version of Tower of London task. Neuroimage. 2003;18(2):367-374.

18. Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Glaser R, et al. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(8):1310-1317.

19. Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):411-418.

20. Nelson JC, Mazure C, Quinlan DM, et al. Drug-responsive symptoms in melancholia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(7):663-668.

21. Fava M, Ball S, Nelson, JC, et al. Clinical relevance of fatigue as a residual symptom in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(3):250-257.

22. Anisman H, Merali Z, Poulter MO, et al. Cytokines as a precipitant of depressive illness: animal and human studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(8):963-972.

23. Simon NM, McNamara K, Chow CW, et al. A detailed examination of cytokine abnormalities in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(3):230-233.

24. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

25. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382-389.

26. Matza LS, Phillips GA, Revicki DA, et al. Development and validation of a patient-report measure of fatigue associated with depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):294-303.

27. Matza LS, Wyrwich KW, Phillips GA, et al. The Fatigue Associated with Depression Questionnaire (FAsD): responsiveness and responder definition. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(2):351-360.

28. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda. gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Published December 2009. Accessed May 7, 2015.

29. Knoth RL, Bolge SC, Kim E, et al. Effect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):e188-e196.

30. Fava M. Symptoms of fatigue and cognitive/executive dysfunction in major depressive disorder before and after antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 14):30-34.

31. Chang T, Fava M. The future of psychopharmacology of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(8):971-975.

32. Baldwin DS, Papakostas GI. Symptoms of fatigue and sleepiness in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):9-15.

33. Ball SG, Dellva MA, D’Souza D, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of augmentation with LY2216684 for major depressive disorder patients who are partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [abstract P 05]. Int J Psych Clin Pract. 2010;14(suppl 1):19.

34. Stahl SM. Using secondary binding properties to select a not so elective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(12):642-643.

35. Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

36. Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(5):699-711.

37. Scammell TE, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, et al. Hypothalamic arousal regions are activated during modafinil-induced wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2000;20(22):8620-8628.

38. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, et al. The relationship between adverse events during selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for major depressive disorder and nonremission in the suicide assessment methodology study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):31-38.

39. Nelson JC. A review of the efficacy of serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors for treatment of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1301-1308.

40. Papakostas GI, Nutt DJ, Hallett LA, et al. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1350-1355.

41. Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, et al. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):106-113.

42. Candy M, Jones CB, Williams R, et al. Psychostimulants for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006722.pub2.

43. Lam JY, Freeman MK, Cates ME. Modafinil augmentation for residual symptoms of fatigue in patients with a partial response to antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(6):1005-1012.

44. Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clinical Psychol Rev. 2001;21(1):33-61.

45. Trivedi MH, Greer TL, Grannemann BD, et al. Exercise as an augmentation strategy for treatment of major depression. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(4):205-213.