User login

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

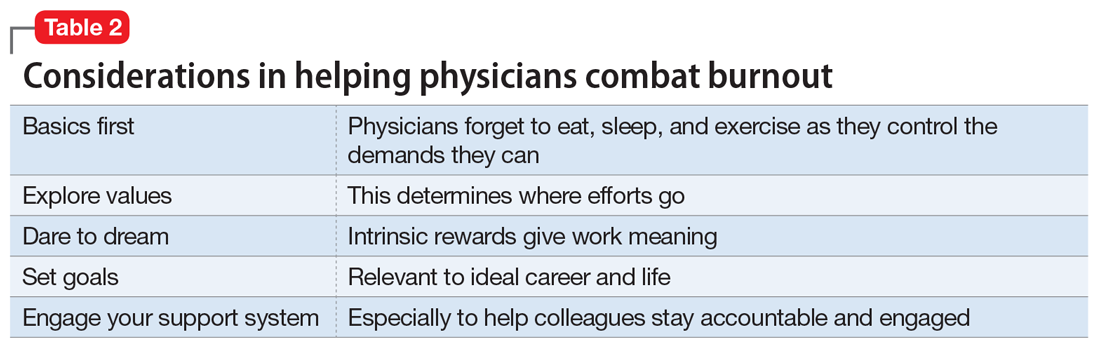

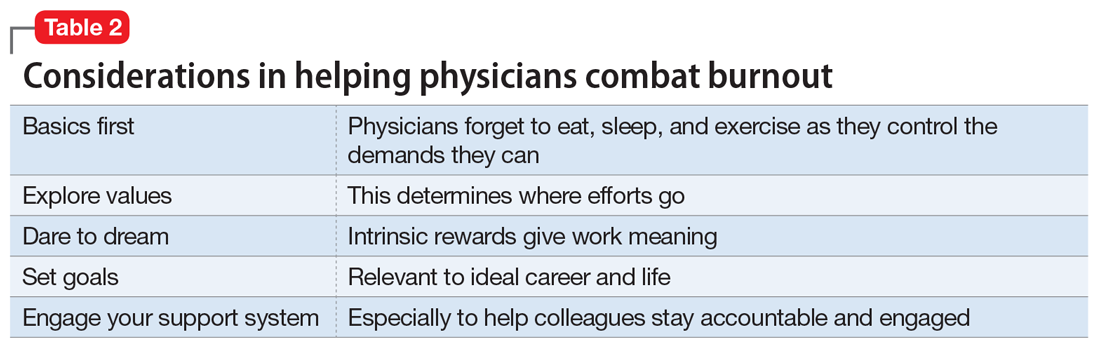

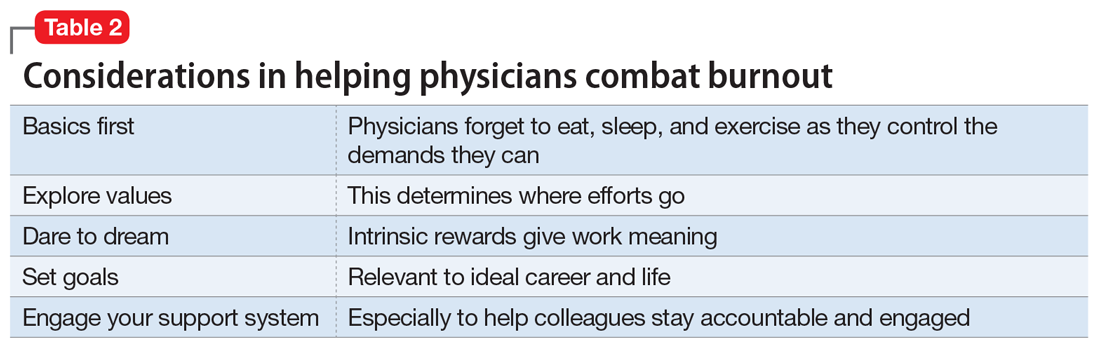

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

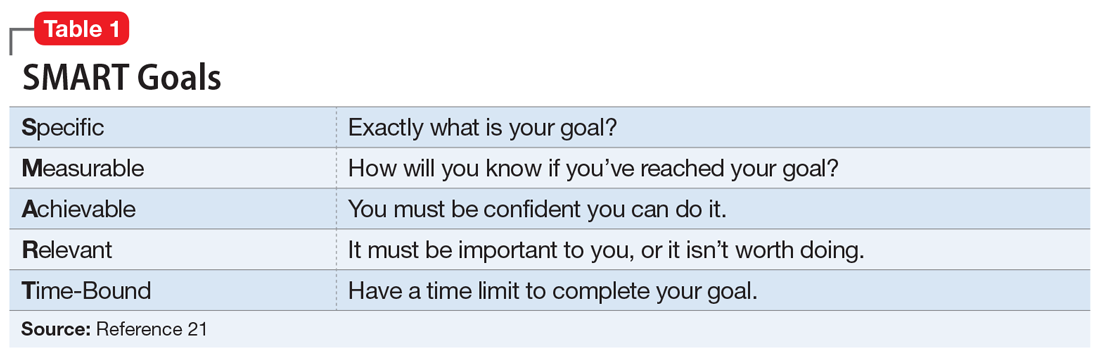

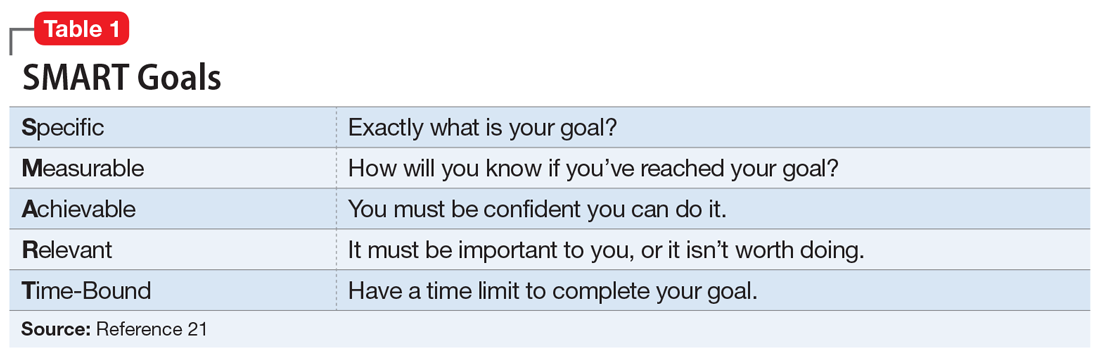

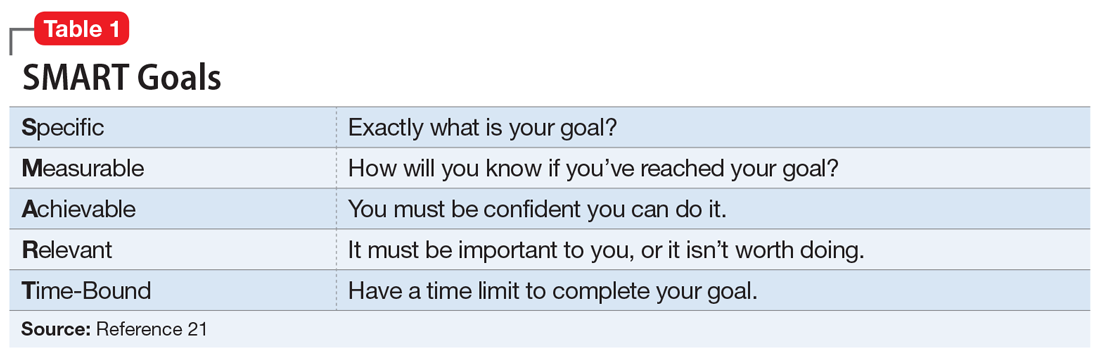

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.