User login

Clostridium difficile was not given its name because it is easy to diagnose. Indeed, the name reflects the difficulty that the original discoverers of this bacterium had in isolating the germ and getting it to grow. In many respects, C. difficile continues to be a difficult pathogen for today’s practitioners.

As an important reemerging nosocomial and community-acquired pathogen, C. difficile (CD) can cause mild to severe diarrhea or no symptoms at all. In children especially, colonization with the anaerobic, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus does not necessarily mean that CD is the cause of diarrhea nor that treatment is always necessary, even when toxin is present. Indeed, depending on the screening/diagnostic test used, false positives may occur and thus a combination of tests often is warranted.

Further complicating the process, CD can be a normal component of the bowel flora of infants. Therefore, routine testing is currently suggested for children over 1 year of age with symptoms consistent with C. difficile infection (CDI) and with a history of recent antibiotic use. We currently do not have good guidelines for what to do with infants less than 1 year of age.

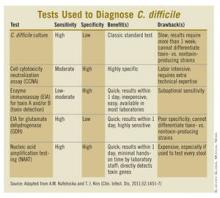

Prior to the mid-1990s, if children older than 1 year of age with diarrhea needed CD testing, a direct cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay (CCNA) was used. While the advantages of using a CCNA included moderate to high sensitivity and high specificity, turnaround time was slow (3-7 days), the testing procedure was labor intensive, and interpretation of the results required special technical expertise. Clinicians were forced to consider empiric treatment until the results came back. Even then a positive toxin assay did not necessarily mean that the toxin was the cause of the child’s current diarrhea. Some children beyond infancy, especially those in group homes and institutionalized settings, can be asymptomatic carriers of toxin-producing strains.

More recently, enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) became available to detect C. difficile toxins A (TcdA) and B (TcdB), as well as the CD-specific antigen glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). GDH is found in both toxin and nontoxin producing CD strains. Compared with CCNA or toxigenic culture, these assays have more rapid turnaround time, are less labor-intensive, and don’t require special laboratory expertise for interpretation. However, recently, it has become clear that the EIA toxin assays lack sufficient sensitivity for use as the sole diagnostic test for CDI. On the other hand, the GDH EIA’s better sensitivity, compared with the toxin EIAs, is counterbalanced by its inability to distinguish between toxigenic and nontoxigenic CD. So, the best EIA approach combines GDH, TcdA, and/or TcdB testing.

More recently, CD testing via nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), usually by polymerase chain reaction testing (PCR), has become available. Although developed more than 15 years ago, it has been improved. The potentially high sensitivity and specificity of PCR might make it the optimal CD test just when we need it because of recent changes in epidemiology and severity of CDI: The increase in community-acquired CD cases that are not associated with antibiotics, and the emergence of a fluoroquinolone-resistant epidemic strain (Anaerobe 2003;9:289-94).

In addition to PCR’s high sensitivity and specificity, other advantages include short turnaround time and ease of performance with minimal hands-on time. The main downside is cost, which can be 3-10 times more than EIA.

A nice paper summarizing the pros and cons of various CD tests and a treatment algorithm taking into account a multistep testing approach was recently published (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:1451-7).

At our institution, we use GDH EIA plus the toxin A&B EIA tests to screen symptomatic children older than 1 year of age. We reserve PCR as a "tiebreaker" for those with positive GDH but negative for both toxins. In this scenario, if the PCR is positive and ongoing symptoms are consistent with CDI, treatment is warranted. Keep in mind, however, that successfully treated CDI patients may have persistent but asymptomatic CD colonization (and detectable toxin by PCR) for several weeks after treatment. So PCR is not necessarily reliable in those patients. A study at our institution is currently actively assessing physician understanding and comfort with evolving CD diagnostic and treatment modalities, including our recent implementation of the two-step method.

While we now have more precise CD testing tools for older children, infants younger than 1 year of age should not routinely be tested or treated for CDI. They should be evaluated for other, more likely causes of diarrhea. And we likely will not have clearer guidelines in this area anytime soon.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases and Dr. Klatte is a second-year fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Neither Dr. Harrison nor Dr. Klatte has any relevant financial disclosures.

Clostridium difficile was not given its name because it is easy to diagnose. Indeed, the name reflects the difficulty that the original discoverers of this bacterium had in isolating the germ and getting it to grow. In many respects, C. difficile continues to be a difficult pathogen for today’s practitioners.

As an important reemerging nosocomial and community-acquired pathogen, C. difficile (CD) can cause mild to severe diarrhea or no symptoms at all. In children especially, colonization with the anaerobic, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus does not necessarily mean that CD is the cause of diarrhea nor that treatment is always necessary, even when toxin is present. Indeed, depending on the screening/diagnostic test used, false positives may occur and thus a combination of tests often is warranted.

Further complicating the process, CD can be a normal component of the bowel flora of infants. Therefore, routine testing is currently suggested for children over 1 year of age with symptoms consistent with C. difficile infection (CDI) and with a history of recent antibiotic use. We currently do not have good guidelines for what to do with infants less than 1 year of age.

Prior to the mid-1990s, if children older than 1 year of age with diarrhea needed CD testing, a direct cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay (CCNA) was used. While the advantages of using a CCNA included moderate to high sensitivity and high specificity, turnaround time was slow (3-7 days), the testing procedure was labor intensive, and interpretation of the results required special technical expertise. Clinicians were forced to consider empiric treatment until the results came back. Even then a positive toxin assay did not necessarily mean that the toxin was the cause of the child’s current diarrhea. Some children beyond infancy, especially those in group homes and institutionalized settings, can be asymptomatic carriers of toxin-producing strains.

More recently, enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) became available to detect C. difficile toxins A (TcdA) and B (TcdB), as well as the CD-specific antigen glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). GDH is found in both toxin and nontoxin producing CD strains. Compared with CCNA or toxigenic culture, these assays have more rapid turnaround time, are less labor-intensive, and don’t require special laboratory expertise for interpretation. However, recently, it has become clear that the EIA toxin assays lack sufficient sensitivity for use as the sole diagnostic test for CDI. On the other hand, the GDH EIA’s better sensitivity, compared with the toxin EIAs, is counterbalanced by its inability to distinguish between toxigenic and nontoxigenic CD. So, the best EIA approach combines GDH, TcdA, and/or TcdB testing.

More recently, CD testing via nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), usually by polymerase chain reaction testing (PCR), has become available. Although developed more than 15 years ago, it has been improved. The potentially high sensitivity and specificity of PCR might make it the optimal CD test just when we need it because of recent changes in epidemiology and severity of CDI: The increase in community-acquired CD cases that are not associated with antibiotics, and the emergence of a fluoroquinolone-resistant epidemic strain (Anaerobe 2003;9:289-94).

In addition to PCR’s high sensitivity and specificity, other advantages include short turnaround time and ease of performance with minimal hands-on time. The main downside is cost, which can be 3-10 times more than EIA.

A nice paper summarizing the pros and cons of various CD tests and a treatment algorithm taking into account a multistep testing approach was recently published (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:1451-7).

At our institution, we use GDH EIA plus the toxin A&B EIA tests to screen symptomatic children older than 1 year of age. We reserve PCR as a "tiebreaker" for those with positive GDH but negative for both toxins. In this scenario, if the PCR is positive and ongoing symptoms are consistent with CDI, treatment is warranted. Keep in mind, however, that successfully treated CDI patients may have persistent but asymptomatic CD colonization (and detectable toxin by PCR) for several weeks after treatment. So PCR is not necessarily reliable in those patients. A study at our institution is currently actively assessing physician understanding and comfort with evolving CD diagnostic and treatment modalities, including our recent implementation of the two-step method.

While we now have more precise CD testing tools for older children, infants younger than 1 year of age should not routinely be tested or treated for CDI. They should be evaluated for other, more likely causes of diarrhea. And we likely will not have clearer guidelines in this area anytime soon.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases and Dr. Klatte is a second-year fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Neither Dr. Harrison nor Dr. Klatte has any relevant financial disclosures.

Clostridium difficile was not given its name because it is easy to diagnose. Indeed, the name reflects the difficulty that the original discoverers of this bacterium had in isolating the germ and getting it to grow. In many respects, C. difficile continues to be a difficult pathogen for today’s practitioners.

As an important reemerging nosocomial and community-acquired pathogen, C. difficile (CD) can cause mild to severe diarrhea or no symptoms at all. In children especially, colonization with the anaerobic, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus does not necessarily mean that CD is the cause of diarrhea nor that treatment is always necessary, even when toxin is present. Indeed, depending on the screening/diagnostic test used, false positives may occur and thus a combination of tests often is warranted.

Further complicating the process, CD can be a normal component of the bowel flora of infants. Therefore, routine testing is currently suggested for children over 1 year of age with symptoms consistent with C. difficile infection (CDI) and with a history of recent antibiotic use. We currently do not have good guidelines for what to do with infants less than 1 year of age.

Prior to the mid-1990s, if children older than 1 year of age with diarrhea needed CD testing, a direct cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay (CCNA) was used. While the advantages of using a CCNA included moderate to high sensitivity and high specificity, turnaround time was slow (3-7 days), the testing procedure was labor intensive, and interpretation of the results required special technical expertise. Clinicians were forced to consider empiric treatment until the results came back. Even then a positive toxin assay did not necessarily mean that the toxin was the cause of the child’s current diarrhea. Some children beyond infancy, especially those in group homes and institutionalized settings, can be asymptomatic carriers of toxin-producing strains.

More recently, enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) became available to detect C. difficile toxins A (TcdA) and B (TcdB), as well as the CD-specific antigen glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). GDH is found in both toxin and nontoxin producing CD strains. Compared with CCNA or toxigenic culture, these assays have more rapid turnaround time, are less labor-intensive, and don’t require special laboratory expertise for interpretation. However, recently, it has become clear that the EIA toxin assays lack sufficient sensitivity for use as the sole diagnostic test for CDI. On the other hand, the GDH EIA’s better sensitivity, compared with the toxin EIAs, is counterbalanced by its inability to distinguish between toxigenic and nontoxigenic CD. So, the best EIA approach combines GDH, TcdA, and/or TcdB testing.

More recently, CD testing via nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), usually by polymerase chain reaction testing (PCR), has become available. Although developed more than 15 years ago, it has been improved. The potentially high sensitivity and specificity of PCR might make it the optimal CD test just when we need it because of recent changes in epidemiology and severity of CDI: The increase in community-acquired CD cases that are not associated with antibiotics, and the emergence of a fluoroquinolone-resistant epidemic strain (Anaerobe 2003;9:289-94).

In addition to PCR’s high sensitivity and specificity, other advantages include short turnaround time and ease of performance with minimal hands-on time. The main downside is cost, which can be 3-10 times more than EIA.

A nice paper summarizing the pros and cons of various CD tests and a treatment algorithm taking into account a multistep testing approach was recently published (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:1451-7).

At our institution, we use GDH EIA plus the toxin A&B EIA tests to screen symptomatic children older than 1 year of age. We reserve PCR as a "tiebreaker" for those with positive GDH but negative for both toxins. In this scenario, if the PCR is positive and ongoing symptoms are consistent with CDI, treatment is warranted. Keep in mind, however, that successfully treated CDI patients may have persistent but asymptomatic CD colonization (and detectable toxin by PCR) for several weeks after treatment. So PCR is not necessarily reliable in those patients. A study at our institution is currently actively assessing physician understanding and comfort with evolving CD diagnostic and treatment modalities, including our recent implementation of the two-step method.

While we now have more precise CD testing tools for older children, infants younger than 1 year of age should not routinely be tested or treated for CDI. They should be evaluated for other, more likely causes of diarrhea. And we likely will not have clearer guidelines in this area anytime soon.

Dr. Harrison is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases and Dr. Klatte is a second-year fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Neither Dr. Harrison nor Dr. Klatte has any relevant financial disclosures.