User login

From the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health (Dr. Janevic) and the Medical School (Dr. Sanders), University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: Asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are all greater among adult women compared to men. Appropriate asthma self-management can improve asthma control. We reviewed published literature about sex- and gender-related factors that influence asthma self-management among women, as well as evidence-based interventions to promote effective asthma self-management in this population.

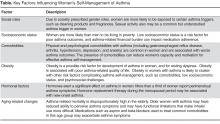

- Design: Based on evidence from the published literature, factors influencing women’s asthma self-management were categorized as follows: social roles and socioeconomic status, comorbidities, obesity, hormonal factors, and aging-related changes.

- Results: A number of factors were identified that affect women’s asthma self-management. These include: exposure to asthma triggers associated with gender roles, such as cleaning products; financial barriers to asthma management; comorbidities that divert attention or otherwise interfere with asthma management; a link between obesity and poor asthma outcomes; the effects of hormonal shifts associated with menstrual cycles and menopause on asthma control; and aging-associated barriers to effective self-management such as functional limitations and caregiving. Certain groups, such as African-American women, are at higher risk for poor asthma outcomes linked to many of the above factors. At least 1 health coaching intervention designed for women with asthma has been shown in a randomized trial to reduce symptoms and health care use.

- Conclusion: Future research on women and asthma self-management should include a focus on the relationship between hormonal changes and asthma symptoms. Interventions are also needed that address the separate and interacting effects of risk factors for poor asthma control that tend to cluster in women, such as obesity, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In childhood, asthma is more prevalent in boys than in girls. In adolescence and adulthood, however, asthma becomes a predominantly female disease, with hormonal factors likely playing a role in this shift [1,2]. Fu et al [3] reviewed daily asthma symptom diaries of 418 children. From age 5 to 7, boys had more severe symptoms, but by age 10 girls’ symptoms were becoming more severe. By age 14, the girls’ symptoms continued increasing while the boys’ symptoms began to decline. A meta-analysis by Lieberoth et al [4] found a 37% increased risk of post-menarchal asthma in girls with onset of menarche < 12 years. Together, these studies implicate female sex hormones in both the increased incidence and severity of asthma after puberty. In 2012, nearly 10% of adult women reported current asthma, compared to only 6% of men [5]. Among adults with asthma, women have a 30% higher mortality rate than men [6]. Disparities that disadvantage women are also evident across a range of other asthma-related outcomes, including disease severity, rescue inhaler use, activity limitations, asthma-related quality of life, and health care utilization [7–12].

Factors Influencing Asthma Self-Management in Women

Social Roles and Socioeconomic Status

Traditional gender roles involve various responsibilities, such as household cleaning, cooking, and care of young children, that are associated with exposures to precipitants of asthma symptoms [17]. Gender norms also promote the use of personal care products, like fragrances and hair sprays, which are potential asthma triggers [17]. Recent observational studies in Europe have examined the link between women’s use of cleaning products and asthma. Bédard and colleagues [18] found an association between weekly use of cleaning sprays at home and asthma among women, and Dumas and colleagues [19] found that workplace exposure to cleaning products among women with asthma was related to increased symptoms and severity of asthma. These researchers conclude that “while domestic exposure is much more frequent in the general population, exposure levels are probably higher at the workplace” and therefore both contribute to asthma disease burden [19]. Although little-discussed in the literature, sexual activity is another common trigger of asthma symptoms in women. Clark et al [15] found that more than one-third of women taking part in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an asthma self-management intervention reported being bothered by symptoms of asthma during sexual activity. This topic was rarely discussed, however, by their health care providers [20].

Socioeconomic factors also play a significant role in asthma management. There is a well-recognized and persistent gender gap in income in the U.S. population such that women who work full-time only earn three-quarters of what their male counterparts earn [21]. Challenges related to low socioeconomic status (SES) may contribute to poor medication adherence among asthma patients [22]. Although a comprehensive review of the impact of SES-related factors on asthma prevalence, severity, and disease-management behaviors is beyond the scope of this article, recent research demonstrates the impact of financial stress on women’s asthma self-management. Patel et al (2014) studied health-related financial burden among African-American women with asthma [23]. Despite the fact that the majority of women in this qualitative study had health insurance, they felt greatly burdened by out-of-pocket expenses such as high co-pays for medications or ambulance use, lost wages due to sick time, and gaps in insurance coverage. These financial concerns—and related issues such as time spent navigating health care insurance and cycling through private and public insurance programs—were described as a significant source of ongoing stress by this group of vulnerable asthma patients [23]. Focus group participants reported several strategies for dealing with asthma-related financial challenges, including stockpiling medications when feasible (eg, when covered by current insurance plan) for future use by the patient or a family member, seeking out and using community assistance programs, and foregoing medications altogether during periods when they could not afford them [23].

Comorbidities

The 2010 publication of Multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework by the US Department of Health and Human Services [24] brought the attention of the medical and research communities to the scope and significance of multimorbidity in the US population, including the challenges that individuals face in managing multiple chronic health conditions. Although the prevalence of specific comorbidities with asthma differs by age, some that are most commonly associated with asthma and that may complicate asthma control are obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), rhinitis, and sinusitis [25,26]. Among women with asthma, multimorbidity appears to be the rule, not the exception. Using nationally-representative data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Patel et al [27] found that more than half of adults with asthma reported also being diagnosed with at least 1 additional major chronic condition. A recent study found that asthma/arthritis and asthma/hypertension were the second and third most prevalent disease dyads among all US women aged 18–44 years [28]. Studies have found that comorbidities among asthma patients are associated with worse asthma outcomes, including increased symptoms, activity limitations and sleep disturbance due to asthma [27], and ED use for asthma [15,27].

Qualitative research yields insight into the patient perspective of multimorbidity, that is, how women with asthma and coexisting chronic diseases perceive the effect of their health conditions on their ability to engage in self-management. Janevic and colleagues [29] conducted face-to-face interviews with African-American women participating in a randomized controlled trial of a culturally and gender-tailored asthma-management intervention to learn about their experiences managing asthma and concurrent health conditions. Interviewees had an average of 5.7 chronic conditions in addition to asthma. Women reported that managing their asthma often “took a backseat” to other chronic conditions. Participants also discussed reduced motivation or capacity for asthma self-management due to depression, chronic pain, mobility limitations or combinations of these, and reduced adherence to asthma medications due to the psychological and logistical burdens of polypharmacy.

Depression and anxiety are common comorbidities that are associated with worse asthma outcomes [26,30–32] and reduced asthma medication adherence [33,34]. In general population studies as well as among asthma patients, women are more likely than men to report depression and anxiety [30,35–37]. Screening for and treating depression and anxiety are indicated in women with asthma and may lead to improved adherence and outcomes [30].

Obesity

Adults with asthma are at increased risk of obesity [38]. Obesity is a possible risk factor for development of asthma in women [2] and for resting dyspnea in women with asthma [39]. It is associated with poor asthma-related QOL and use of emergency/urgent services [40]. Evidence is mixed regarding the link between BMI and asthma control [41–43], but the following studies suggest that women who are overweight/obese face unique asthma management challenges. Valerio and colleagues found that in a sample of 808 women enrolled in a randomized trial of an asthma-education intervention, nearly 7 out of 10 were overweight (BMI ≥ 25) or obese (BMI ≥ 30), and nearly a quarter were “extremely obese” (BMI > 35) [44]. This subgroup of women was more likely to have persistent asthma, comorbid GERD and urinary incontinence, to be non-white, and to have lower levels of education and income. Being overweight was also associated with greater use of health care services and having greater psychosocial challenges (ie, a higher need for asthma-related social support and lower asthma-related quality of life). These authors suggest the need to design communications for overweight women with asthma that recognize “the specific cultural and social influences on their asthma management behaviors” [44] with a focus on psychosocial needs, while incorporating existing social support networks. In the previously discussed study by Janevic and colleagues [29] the average BMI of the interview participants was 36.0, and a number of respondents identified weight loss as the self-care behavior that they thought would benefit them the most across multimorbid conditions. Therefore, health care providers should provide appropriate counseling and/or referrals to help women with asthma achieve weight loss goals. Given trends over time showing increasing prevalence of asthma and obesity [45,46], interest is growing in the asthma research community about the interaction of the 2 conditions.

Hormonal Factors

Hormones exert a significant effect on asthma in women, and must be considered in clinical and self-management of the disease. Hormone levels fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, with a surge of estradiol (a type of estrogen) at the time of ovulation around day 14, accompanied by low levels of progesterone. During the luteal phase (day 14–28 of the menstrual cycle), estrogens decrease while progesterone levels increase then decrease again before onset of menstruation [47]. During pregnancy, levels of estrogens and progesterone increase and are the highest during the third trimester, when women usually experience good asthma control. Then, during menopause both estradiol and progesterone levels drop to lower levels than those during any phase of menstruation. In addition to the role in the menstrual cycle, there are estrogen receptors (ER-α and ER-β) which are expressed in the human lung and have a role in both airway responsiveness (relaxation) and inflammation [48]. Estrogen also acts directly on cells of the immune system to stimulate airway inflammation, particularly when allergens are present [48]. Further discussion about these contrasting actions of estrogen can be found in a recent review [48].

During the reproductive years, 30% to 40% of women with asthma report perimenstrual symptoms. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity are lowest in the periovulatory period, when estrogen levels are high. In contrast, during the luteal phase, studies have shown increased airway hyperreactivity, especially in the premenstrual period when estrogen levels are low [49]. However, when asthma patients with and without perimenstrual symptoms are evaluated, there is no significant difference in their perimenstrual estrogen and progesterone levels [50]. Clark et al [15] found women participating in a self-management intervention, which included checking daily peak flow rates, reported significantly more menstrual and perimenstrual asthma symptomatology than the control group. This suggests that some women with asthma have may have, but do not recognize, perimenstrual symptoms. Further elucidation of the incidence of symptomatology related to the menstrual cycle as well as the role of hormonal variation is an area for future research efforts.

At the time of menopause and continuing to postmenopause, levels of both estrogen and progesterone drop to below those during the reproductive years, leading to uncomfortable symptoms in many women. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with either estrogen alone or estrogen-progesterone combination effectively improves these, but there is concern for potential effects on asthma prevalence and severity. Two recent large studies support this concern. Postmenopausal women followed for 10 years in the Nurses’ Health Study with a history of HRT had an increased risk of new onset asthma when compared to postmenopausal women with no history of estrogen use (RR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.69–3.14) [51]. This persisted in estrogen-progesterone users. A large French cohort confirmed the increased onset of new asthma in users of estrogen-alone replacement therapy (HR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.13–2.09). However, this effect decreased with time if estrogen had been discontinued, and they did not find a similar increase in users of estrogen-progesterone combination therapy [52]. In contrast, Bonelykke et al [53] found an association between ever using HRT and first-ever hospital admission for asthma, in postmenopausal women (HR 1.46, CI 1.21–1.76), and this risk increased with duration of HRT use. It is clear that physicians need to be aware of these potential respiratory complications, inform their patients, and consider new-onset asthma when women on HRT bring complaints of dyspnea, cough, or wheeze. Future randomized trials are needed to clarify the relationship between HRT and asthma, and to test ways to optimize asthma self-management in women experiencing these transitions.

Older Women and Asthma

Although the bulk of research on asthma focuses on children and young adults, asthma in the elderly is receiving increased attention [54], in part because this demographic group has the highest asthma mortality rate and the most frequent hospitalizations [6,55]. In a sample of midlife and older women from the Nurses’ Health Study who had been diagnosed with persistent asthma, Barr et al found that adherence to asthma medication guidelines decreased with age [54]. In this study, women with more severe asthma and those with multimorbidity were less adherent than those without comorbidities, as were women who spent more hours caregiving for an ill spouse. The authors concluded that asthma is undertreated among older women.

Baptist et al (2014) describe several challenges to asthma management of older women by clinicians and by the women themselves [55]. For example, elderly women may be at increased risk for adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroids. Certain medications used to treat comorbidities, such as beta-blockers and aspirin, may also exacerbate asthma symptoms. In terms of self-management, older women may have a decreased ability to perceive breathlessness, requiring monitoring with a peak flow meter to detect reductions in airflow. Comorbidities are particularly prevalent in this age group, and asthma symptoms may be confused with symptoms of other conditions, such as heart disease [56]. Baptist and colleagues note factors common among elderly women that pose potential barriers to successful self-management of asthma, including limited income, poverty, depression, and caregiving [55]. They also mention that functional limitations such as those due to arthritis, visual difficulties, or weakened inspiratory strength can make inhaler use more difficult. It should also be noted that some behaviors may promote asthma self-management in this group; for example, Valerio and colleagues [57] found that women over age 50 were more likely than younger women to keep a daily asthma diary when asked to do so as part of a self-management intervention [57].

Evidence-Based Asthma Self-Management Interventions for Women

For women to achieve optimal asthma control, the unique factors as described above that influence their symptoms and management need to be addressed [58]. Several examples can be found in the literature of behavioral interventions that focus on the particular self-management challenges faced by women. Clark and colleagues reported the results of an RCT of the Women Breathe Free (WBF) program [15,16]. This intervention consisted of asthma self-management education delivered over 5 telephone sessions by a health educator. WBF content was based on self-regulation theory, which involves observing one’s behavior and making judgments on the observations, testing strategies to improve asthma management, and reacting to positive results of these strategies with enhanced self-efficacy and outcome expectations, ie, the belief that a given strategy will produce the desired results [59]. In WBF, participants used a problem-solving process based on this framework to carry out recommendations in their physician’s therapeutic plan. WBF also incorporated special attention to sex- and gender-based factors in asthma management.

Over a 12-month period, women who participated in the intervention relative to controls experienced significant reductions in nighttime symptoms, days of missed work/school, emergency department visits, and both scheduled and urgent office visits. Intervention group women also reported decreased asthma symptoms during sexual activity, improved asthma-related quality of life, and increased confidence to manage asthma. At long-term follow-up (2 years from baseline), persistent positive effects of the intervention were found on outpatient visits for asthma symptom level during sexual activity, days of missed work/school, asthma-related quality of life, and confidence to manage asthma [60].

In a follow-up study, Clark and colleagues [61] developed the “Women of Color and Asthma Control” (WCAC) program. WCAC incorporates the theoretical orientation and many of the program elements of Women Breathe Free, but has been adapted to be responsive to the needs and preferences of African-American women. Poverty and race are associated with greater asthma morbidity and mortality [5,62,63]. African-American women and women of low socioeconomic status are particularly vulnerable to asthma and associated morbidity and mortality, making this an important group for intervention. Culturally responsive components in the WCAC intervention include use of culturally relevant activities and beliefs when discussing triggers and barriers to asthma management, as well as culturally appropriate visuals. This ongoing trial will test WCAC’s effect on ED visits, hospitalizations, and urgent care; asthma symptoms; and asthma-related quality of life at 1 year and 18 months from baseline.

In a small RCT among women with asthma, Bidwell and colleagues tested a program consisting of 10 weeks of yoga instruction (including breathing practices, poses, and meditation/relaxation skills) in a group setting followed by 10 weeks of home practice [64]. Women in the intervention group reported improved quality of life, as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Quality of Life questionnaire [65], and participants also had decreased parasympathetic modulation in response to an isometric forearm exercise. They conclude that yoga is a promising modality for improving quality of life among asthma patients and that these changes may be linked to better autonomic modulation. Although this program was not designed specifically for women, yoga is practiced significantly more frequently among women compared to men [66,67], and thus has the potential to be widely used in this group.

Based on our experience conducting self-management research among women with asthma, and unpublished process data from these studies, we observe that the following elements appear to contribute to high participant engagement in these programs and successful outcomes. First, in participant feedback questionnaires from the Women Breathe Free and Women of Color and Asthma Control studies, women have singled out the importance of their relationship with their assigned telephone asthma educator as motivating them to make positive changes in their asthma self-management behaviors. The popularity of health and wellness coaching, including for chronic disease management, is rapidly growing [68]. This is a patient-centered approach that guides patients in setting their own goals for disease management and devising their own strategies for achieving them [68]. Strong interpersonal relationships are thought to enhance the coaching process and this may be especially important for women [68]. Participants have also indicated that they are able to apply the goal-setting and problem-solving skills they have learned as part of the intervention to management of other health or psychosocial issues in their lives; therefore this component seems especially critical for women with asthma who are typically managing multiple health issues as well as those of others. Finally, maximizing the flexibility of interventions is important for working-age women who typically are engaged in part- or full-time employment and also have significant responsibilities caring for others. This flexibility can come in the form of telephone-based or “mHealth” interventions that use mobile technologies such as text messaging [69], as well as internet-based or smartphone/tablet “apps” that can be completed at a pace and schedule that is convenient for the participant [70]. Such interventions could be easily tailored to address sex- and gender-specific issues in asthma management.

Future Research and Practice Directions

This review points to several promising directions for research and practice in the area of supporting women’s asthma self-management. The first is a systematic exploration of the added value of gender-tailoring asthma self-management support interventions to determine which subgroups of women benefit from which type of sex- and gender-specific information, and in which form. More research is needed on the relationship between hormone levels and changes and asthma symptoms, and how this affects women’s self-management. This includes recognition of new or worsening asthma with the use of hormone replacement therapy in menopausal and post-menopausal women, a group that is rapidly increasing in number in the US population. Another direction for research is a family-systems approach to asthma education and supporting asthma management. Asthma in one or more first-degree relatives has been shown across diverse populations to be a risk factor for asthma [71]. Women with asthma are therefore more likely to have children with asthma, and vice-versa; however, no prior research was identified that addresses asthma self-management in mother/child dyads. For example, it is possible that teaching women to better manage their own asthma could have “trickle down” effects to how they help a child manage asthma. Last, as the above discussion of factors affecting women’s asthma makes clear, many risk factors for poor asthma management and control in women cluster together, such as obesity, depression, and GERD. Interventions that attempt to address the separate and interacting effects of these factors and comorbidities, may yield better outcomes among the most vulnerable asthma patients.

Corresponding author: Mary R. Janevic, PhD, Center for Managing Chronic Disease, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1425 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Postma DS. Gender differences in asthma development and progression. Gend Med 2007;4 Suppl B:S133–46.

2. Melgert BN, Ray A, Hylkema MN, et al. Are there reasons why adult asthma is more common in females? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2007;7:143–50.

3. Fu L, Freishtat RJ, Gordish-Dressman H, et al. Natural progression of childhood asthma symptoms and strong influence of sex and puberty. Ann Am Thor Soc 2014;11:939–44.

4. Lieberoth S, Gade EJ, Brok J, et al. Age at menarche and risk of asthma: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma 2014;51:559–65.

5. Blackwell D, Lucas J, Clarke T. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat 10 2014;(260):1–161.

6. Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief 2012 May;(94):1–8.

7. Sinclair AH, Tolsma DD. Gender differences in asthma experience and disease care in a managed care organization. J Asthma 2006;43:363–7.

8. Naleway AL, Vollmer WM, Frazier EA, et al. Gender differences in asthma management and quality of life. J Asthma 2006;43:549–52.

9. Lisspers K, Ställberg B, Janson C, et al. Sex-differences in quality of life and asthma control in Swedish asthma patients. J Asthma 2013;50:1090–5.

10. Ostrom NK. Women with asthma: a review of potential variables and preferred medical management. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;96:655–65.

11. Kynyk JA, Mastronarde JG, McCallister JW. Asthma, the sex difference. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2011;17:6–11.

12. Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat 10 2012;(252):1–207.

13. Clark NM, Becker MH, Janz NK, et al. Self-management of chronic disease by older adults: A review and directions for research. J Aging Health 1991;3:3–27.

14. Sundberg R, Torén K, Franklin KA, et al. Asthma in men and women: Treatment adherence, anxiety, and quality of sleep. Resp Med 2010;104:337–44.

15. Clark NM, Gong ZM, Wang SJ, et al. A randomized trial of a self-regulation intervention for women with asthma. Chest 2007;132:88–97.

16. Clark NM, Gong ZM, Wang SJ, et al. From the female perspective: Long-term effects on quality of life of a program for women with asthma. Gend Med 2010;7:125–36.

17. Thomas LJ, Janevic MR, Sanders G, Clark NM. Gender-related asthma challenges in a sample of African American women. Poster presented at 2012 Women’s Health Congress.

18. Bedard A, Varraso R, Sanchez M, et al. Cleaning sprays, household help and asthma among elderly women. Respir Med 2014;108:171–80.

19. Dumas O, Siroux V, Luu F, et al. Cleaning and asthma characteristics in women. Am J Ind Med 2014;57:303–11.

20. Clark NM, Valerio MA, Gong ZM. Self-regulation and women with asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;8:222–7.

21. Lips HM. The gender pay gap: Challenging the rationalizations. Perceived equity, discrimination, and the limits of human capital models. Sex Roles 2013;68:169–85.

22. Apter AJ, Reisine ST, Affleck G, et al. Adherence with twice-daily dosing of inhaled steroids. Socioeconomic and health-belief differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157(6 Pt 1):1810–7.

23. Patel MR, Nelson BW, Id-Deen E, Caldwell CH. Beyond co-pays and out-of-pocket costs: perceptions of health-related financial burden in managing asthma among African American women. J Asthma 2014;51:1083–8.

24. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Multiple chronic conditions—a strategic framework: optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. Washington, DC; 2010.

25. Boulet LP, Boulay ME. Asthma-related comorbidities. Expert Rev Respir Med 2011;5:377–93.

26. Sumino K, O’Brian K, Bartle B, et al. Coexisting chronic conditions associated with mortality and morbidity in adult patients with asthma. J Asthma 2014;51:306–14.

27. Patel MR, Janevic MR, Heeringa SG, et al. An examination of adverse asthma outcomes in U.S. Adults with multiple morbidities. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013;10:426–31.

28. Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E65.

29. Janevic MR, Ellis KR, Sanders GM, et al. Self-management of multiple chronic conditions among African American women with asthma: a qualitative study. J Asthma 2014;51:243–52.

30. Eisner MD, Katz PP, Lactao G, Iribarren C. Impact of depressive symptoms on adult asthma outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005;94:566–74.

31. Strine TW, Mokdad AH, Balluz LS, et al. Impact of depression and anxiety on quality of life, health behaviors, and asthma control among adults in the United States with asthma, 2006. J Asthma 2008;45:123–33.

32. Di Marco F, Verga M, Santus P, et al. Close correlation between anxiety, depression, and asthma control. Resp Med 2010;104:22–8.

33. Smith A, Krishnan JA, Bilderback A, et al. Depressive symptoms and adherence to asthma therapy after hospital discharge. Chest 2006;130:1034–8.

34. Krauskopf KA, Sofianou A, Goel MS, et al. Depressive symptoms, low adherence, and poor asthma outcomes in the elderly. J Asthma 2013;50:260–6.

35. Current depression among adults---United States, 2006 and 2008. MMWR 2010;59:1229–35.

36. McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45:1027–35.

37. Sundberg R, Toren K, Franklin KA, et al. Asthma in men and women: treatment adherence, anxiety, and quality of sleep. Respir Med 2010;104:337–44.

38. Ford ES. The epidemiology of obesity and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:897–909.

39. Essalhi M, Gillaizeau F, Chevallier JM, et al. Cross-sectional assessment of the roles of comorbidities in resting and activity-related dyspnea in severely obese women. J Asthma 2013;50:565–72.

40. Grammer LC, Weiss KB, Pedicano JB, et al. Obesity and asthma morbidity in a community-based adult cohort in a large urban area: the Chicago Initiative to Raise Asthma Health Equity (CHIRAH). J Asthma 2010;47:491–5.

41. Clerisme-Beaty EM, Karam S, Rand C, et al. Does higher body mass index contribute to worse asthma control in an urban population? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:207–12.

42. Boudreau M, Bacon SL, Ouellet K, et al. Mediator effect of depressive symptoms on the association between BMI and asthma control in adults. Chest 2014;146:348–54.

43. Camargo CA Jr, Sutherland ER, Bailey W, et al. Effect of increased body mass index on asthma risk, impairment and response to asthma controller therapy in African Americans. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:1629–35.

44. Valerio MA, Gong ZM, Wang S, et al. Overweight women and management of asthma. Women Health Issues 2009;19:

300–5.

45. Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–1962 through 2009–2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012.

46. Manion AB. Asthma and obesity: the dose effect. Nurs Clin North Am 2013;48:151–8.

47. Tam A, Morrish D, Wadsworth S, et al. The role of female hormones on lung function in chronic lung diseases. BMC Women Health 2011;11:24.

48. Ticconi C, Pietropolli A, Piccione E. Estrogen replacement therapy and asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2013;26:617–23.

49. Bonds RS, Midoro-Horiuti T. Estrogen effects in allergy and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;13:92–9.

50. Pereira-Vega A, Sanchez Ramos JL, Vazquez Oliva R, et al. Premenstrual asthma and female sex hormones. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2012;22:437–9.

51. Barr RG, Wentowski CC, Grodstein F, et al. Prospective study of postmenopausal hormone use and newly diagnosed asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:379–86.

52. Romieu I, Fabre A, Fournier A, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and asthma onset in the E3N cohort. Thorax 2010;65:292–7.

53. Bonnelykke K, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Tjonneland A, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and asthma-related hospital admission. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015.

54. Barr RG, Somers SC, Speizer FE, Camargo CA, Jr. Patient factors and medication guideline adherence among older women with asthma. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1761–8.

55. Baptist AP, Hamad A, Patel MR. Special challenges in treatment and self-management of older women with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;113:125–30.

56. Baptist AP, Deol BB, Reddy RC, et al. Age-specific factors influencing asthma management by older adults. Qual Health Res 2010;20:117–24.

57. Valerio MA, Parker EA, Couper MP, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics predictive of asthma diary use among women. J Asthma 2008;45:357–61.

58. Ostrom NK. Women with asthma: a review of potential variables and preferred medical management. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;96:655–65.

59. Clark NM, Valerio MA, Gong ZM. Self-regulation and women with asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;8:222.

60. Clark NM, Gong ZM, Wang SJ, et al. From the female perspective: Long-term effects on quality of life of a program for women with asthma. Gend Med 2010;7:125–36.

61. Janevic MR, Sanders GM, Thomas LJ, et al. Study protocol for Women of Color and Asthma Control: a randomized controlled trial of an asthma-management intervention for African American women. BMC Public Health 2012;12:76.

62. Rand CS, Apter AJ. Mind the widening gap: have improvements in asthma care increased asthma disparities? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;2:319–21.

63. Moorman JE, Mannino DM. Increasing U.S. asthma mortality rates: who is really dying? J Asthma 2001;38:65–71.

64. Bidwell AJ, Yazel B, Davin D, et al. Yoga training improves quality of life in women with asthma. J Altern Complement Med 2012;18:749–55.

65. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD 2005;2:75–9.

66. Ding D, Stamatakis E. Yoga practice in England 1997-2008: prevalence, temporal trends, and correlates of participation. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:172.

67. Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, et al. Characteristics of yoga users: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1653–8.

68. Wolever RQ, Simmons LA, Sforzo GA, et al. A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: defining a key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med 2013;2:38–57.

69. Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001362.

70. Marcano Belisario JS, Huckvale K, Greenfield G, et al. Smartphone and tablet self management apps for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;11:CD010013.

71. Burke W, Fesinmeyer M, Reed K, et al. Family history as a predictor of asthma risk. Am J Prev Med 2003;24:160–9.

From the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health (Dr. Janevic) and the Medical School (Dr. Sanders), University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: Asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are all greater among adult women compared to men. Appropriate asthma self-management can improve asthma control. We reviewed published literature about sex- and gender-related factors that influence asthma self-management among women, as well as evidence-based interventions to promote effective asthma self-management in this population.

- Design: Based on evidence from the published literature, factors influencing women’s asthma self-management were categorized as follows: social roles and socioeconomic status, comorbidities, obesity, hormonal factors, and aging-related changes.

- Results: A number of factors were identified that affect women’s asthma self-management. These include: exposure to asthma triggers associated with gender roles, such as cleaning products; financial barriers to asthma management; comorbidities that divert attention or otherwise interfere with asthma management; a link between obesity and poor asthma outcomes; the effects of hormonal shifts associated with menstrual cycles and menopause on asthma control; and aging-associated barriers to effective self-management such as functional limitations and caregiving. Certain groups, such as African-American women, are at higher risk for poor asthma outcomes linked to many of the above factors. At least 1 health coaching intervention designed for women with asthma has been shown in a randomized trial to reduce symptoms and health care use.

- Conclusion: Future research on women and asthma self-management should include a focus on the relationship between hormonal changes and asthma symptoms. Interventions are also needed that address the separate and interacting effects of risk factors for poor asthma control that tend to cluster in women, such as obesity, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In childhood, asthma is more prevalent in boys than in girls. In adolescence and adulthood, however, asthma becomes a predominantly female disease, with hormonal factors likely playing a role in this shift [1,2]. Fu et al [3] reviewed daily asthma symptom diaries of 418 children. From age 5 to 7, boys had more severe symptoms, but by age 10 girls’ symptoms were becoming more severe. By age 14, the girls’ symptoms continued increasing while the boys’ symptoms began to decline. A meta-analysis by Lieberoth et al [4] found a 37% increased risk of post-menarchal asthma in girls with onset of menarche < 12 years. Together, these studies implicate female sex hormones in both the increased incidence and severity of asthma after puberty. In 2012, nearly 10% of adult women reported current asthma, compared to only 6% of men [5]. Among adults with asthma, women have a 30% higher mortality rate than men [6]. Disparities that disadvantage women are also evident across a range of other asthma-related outcomes, including disease severity, rescue inhaler use, activity limitations, asthma-related quality of life, and health care utilization [7–12].

Factors Influencing Asthma Self-Management in Women

Social Roles and Socioeconomic Status

Traditional gender roles involve various responsibilities, such as household cleaning, cooking, and care of young children, that are associated with exposures to precipitants of asthma symptoms [17]. Gender norms also promote the use of personal care products, like fragrances and hair sprays, which are potential asthma triggers [17]. Recent observational studies in Europe have examined the link between women’s use of cleaning products and asthma. Bédard and colleagues [18] found an association between weekly use of cleaning sprays at home and asthma among women, and Dumas and colleagues [19] found that workplace exposure to cleaning products among women with asthma was related to increased symptoms and severity of asthma. These researchers conclude that “while domestic exposure is much more frequent in the general population, exposure levels are probably higher at the workplace” and therefore both contribute to asthma disease burden [19]. Although little-discussed in the literature, sexual activity is another common trigger of asthma symptoms in women. Clark et al [15] found that more than one-third of women taking part in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an asthma self-management intervention reported being bothered by symptoms of asthma during sexual activity. This topic was rarely discussed, however, by their health care providers [20].

Socioeconomic factors also play a significant role in asthma management. There is a well-recognized and persistent gender gap in income in the U.S. population such that women who work full-time only earn three-quarters of what their male counterparts earn [21]. Challenges related to low socioeconomic status (SES) may contribute to poor medication adherence among asthma patients [22]. Although a comprehensive review of the impact of SES-related factors on asthma prevalence, severity, and disease-management behaviors is beyond the scope of this article, recent research demonstrates the impact of financial stress on women’s asthma self-management. Patel et al (2014) studied health-related financial burden among African-American women with asthma [23]. Despite the fact that the majority of women in this qualitative study had health insurance, they felt greatly burdened by out-of-pocket expenses such as high co-pays for medications or ambulance use, lost wages due to sick time, and gaps in insurance coverage. These financial concerns—and related issues such as time spent navigating health care insurance and cycling through private and public insurance programs—were described as a significant source of ongoing stress by this group of vulnerable asthma patients [23]. Focus group participants reported several strategies for dealing with asthma-related financial challenges, including stockpiling medications when feasible (eg, when covered by current insurance plan) for future use by the patient or a family member, seeking out and using community assistance programs, and foregoing medications altogether during periods when they could not afford them [23].

Comorbidities

The 2010 publication of Multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework by the US Department of Health and Human Services [24] brought the attention of the medical and research communities to the scope and significance of multimorbidity in the US population, including the challenges that individuals face in managing multiple chronic health conditions. Although the prevalence of specific comorbidities with asthma differs by age, some that are most commonly associated with asthma and that may complicate asthma control are obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), rhinitis, and sinusitis [25,26]. Among women with asthma, multimorbidity appears to be the rule, not the exception. Using nationally-representative data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Patel et al [27] found that more than half of adults with asthma reported also being diagnosed with at least 1 additional major chronic condition. A recent study found that asthma/arthritis and asthma/hypertension were the second and third most prevalent disease dyads among all US women aged 18–44 years [28]. Studies have found that comorbidities among asthma patients are associated with worse asthma outcomes, including increased symptoms, activity limitations and sleep disturbance due to asthma [27], and ED use for asthma [15,27].

Qualitative research yields insight into the patient perspective of multimorbidity, that is, how women with asthma and coexisting chronic diseases perceive the effect of their health conditions on their ability to engage in self-management. Janevic and colleagues [29] conducted face-to-face interviews with African-American women participating in a randomized controlled trial of a culturally and gender-tailored asthma-management intervention to learn about their experiences managing asthma and concurrent health conditions. Interviewees had an average of 5.7 chronic conditions in addition to asthma. Women reported that managing their asthma often “took a backseat” to other chronic conditions. Participants also discussed reduced motivation or capacity for asthma self-management due to depression, chronic pain, mobility limitations or combinations of these, and reduced adherence to asthma medications due to the psychological and logistical burdens of polypharmacy.

Depression and anxiety are common comorbidities that are associated with worse asthma outcomes [26,30–32] and reduced asthma medication adherence [33,34]. In general population studies as well as among asthma patients, women are more likely than men to report depression and anxiety [30,35–37]. Screening for and treating depression and anxiety are indicated in women with asthma and may lead to improved adherence and outcomes [30].

Obesity

Adults with asthma are at increased risk of obesity [38]. Obesity is a possible risk factor for development of asthma in women [2] and for resting dyspnea in women with asthma [39]. It is associated with poor asthma-related QOL and use of emergency/urgent services [40]. Evidence is mixed regarding the link between BMI and asthma control [41–43], but the following studies suggest that women who are overweight/obese face unique asthma management challenges. Valerio and colleagues found that in a sample of 808 women enrolled in a randomized trial of an asthma-education intervention, nearly 7 out of 10 were overweight (BMI ≥ 25) or obese (BMI ≥ 30), and nearly a quarter were “extremely obese” (BMI > 35) [44]. This subgroup of women was more likely to have persistent asthma, comorbid GERD and urinary incontinence, to be non-white, and to have lower levels of education and income. Being overweight was also associated with greater use of health care services and having greater psychosocial challenges (ie, a higher need for asthma-related social support and lower asthma-related quality of life). These authors suggest the need to design communications for overweight women with asthma that recognize “the specific cultural and social influences on their asthma management behaviors” [44] with a focus on psychosocial needs, while incorporating existing social support networks. In the previously discussed study by Janevic and colleagues [29] the average BMI of the interview participants was 36.0, and a number of respondents identified weight loss as the self-care behavior that they thought would benefit them the most across multimorbid conditions. Therefore, health care providers should provide appropriate counseling and/or referrals to help women with asthma achieve weight loss goals. Given trends over time showing increasing prevalence of asthma and obesity [45,46], interest is growing in the asthma research community about the interaction of the 2 conditions.

Hormonal Factors

Hormones exert a significant effect on asthma in women, and must be considered in clinical and self-management of the disease. Hormone levels fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, with a surge of estradiol (a type of estrogen) at the time of ovulation around day 14, accompanied by low levels of progesterone. During the luteal phase (day 14–28 of the menstrual cycle), estrogens decrease while progesterone levels increase then decrease again before onset of menstruation [47]. During pregnancy, levels of estrogens and progesterone increase and are the highest during the third trimester, when women usually experience good asthma control. Then, during menopause both estradiol and progesterone levels drop to lower levels than those during any phase of menstruation. In addition to the role in the menstrual cycle, there are estrogen receptors (ER-α and ER-β) which are expressed in the human lung and have a role in both airway responsiveness (relaxation) and inflammation [48]. Estrogen also acts directly on cells of the immune system to stimulate airway inflammation, particularly when allergens are present [48]. Further discussion about these contrasting actions of estrogen can be found in a recent review [48].

During the reproductive years, 30% to 40% of women with asthma report perimenstrual symptoms. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity are lowest in the periovulatory period, when estrogen levels are high. In contrast, during the luteal phase, studies have shown increased airway hyperreactivity, especially in the premenstrual period when estrogen levels are low [49]. However, when asthma patients with and without perimenstrual symptoms are evaluated, there is no significant difference in their perimenstrual estrogen and progesterone levels [50]. Clark et al [15] found women participating in a self-management intervention, which included checking daily peak flow rates, reported significantly more menstrual and perimenstrual asthma symptomatology than the control group. This suggests that some women with asthma have may have, but do not recognize, perimenstrual symptoms. Further elucidation of the incidence of symptomatology related to the menstrual cycle as well as the role of hormonal variation is an area for future research efforts.

At the time of menopause and continuing to postmenopause, levels of both estrogen and progesterone drop to below those during the reproductive years, leading to uncomfortable symptoms in many women. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with either estrogen alone or estrogen-progesterone combination effectively improves these, but there is concern for potential effects on asthma prevalence and severity. Two recent large studies support this concern. Postmenopausal women followed for 10 years in the Nurses’ Health Study with a history of HRT had an increased risk of new onset asthma when compared to postmenopausal women with no history of estrogen use (RR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.69–3.14) [51]. This persisted in estrogen-progesterone users. A large French cohort confirmed the increased onset of new asthma in users of estrogen-alone replacement therapy (HR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.13–2.09). However, this effect decreased with time if estrogen had been discontinued, and they did not find a similar increase in users of estrogen-progesterone combination therapy [52]. In contrast, Bonelykke et al [53] found an association between ever using HRT and first-ever hospital admission for asthma, in postmenopausal women (HR 1.46, CI 1.21–1.76), and this risk increased with duration of HRT use. It is clear that physicians need to be aware of these potential respiratory complications, inform their patients, and consider new-onset asthma when women on HRT bring complaints of dyspnea, cough, or wheeze. Future randomized trials are needed to clarify the relationship between HRT and asthma, and to test ways to optimize asthma self-management in women experiencing these transitions.

Older Women and Asthma

Although the bulk of research on asthma focuses on children and young adults, asthma in the elderly is receiving increased attention [54], in part because this demographic group has the highest asthma mortality rate and the most frequent hospitalizations [6,55]. In a sample of midlife and older women from the Nurses’ Health Study who had been diagnosed with persistent asthma, Barr et al found that adherence to asthma medication guidelines decreased with age [54]. In this study, women with more severe asthma and those with multimorbidity were less adherent than those without comorbidities, as were women who spent more hours caregiving for an ill spouse. The authors concluded that asthma is undertreated among older women.

Baptist et al (2014) describe several challenges to asthma management of older women by clinicians and by the women themselves [55]. For example, elderly women may be at increased risk for adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroids. Certain medications used to treat comorbidities, such as beta-blockers and aspirin, may also exacerbate asthma symptoms. In terms of self-management, older women may have a decreased ability to perceive breathlessness, requiring monitoring with a peak flow meter to detect reductions in airflow. Comorbidities are particularly prevalent in this age group, and asthma symptoms may be confused with symptoms of other conditions, such as heart disease [56]. Baptist and colleagues note factors common among elderly women that pose potential barriers to successful self-management of asthma, including limited income, poverty, depression, and caregiving [55]. They also mention that functional limitations such as those due to arthritis, visual difficulties, or weakened inspiratory strength can make inhaler use more difficult. It should also be noted that some behaviors may promote asthma self-management in this group; for example, Valerio and colleagues [57] found that women over age 50 were more likely than younger women to keep a daily asthma diary when asked to do so as part of a self-management intervention [57].

Evidence-Based Asthma Self-Management Interventions for Women

For women to achieve optimal asthma control, the unique factors as described above that influence their symptoms and management need to be addressed [58]. Several examples can be found in the literature of behavioral interventions that focus on the particular self-management challenges faced by women. Clark and colleagues reported the results of an RCT of the Women Breathe Free (WBF) program [15,16]. This intervention consisted of asthma self-management education delivered over 5 telephone sessions by a health educator. WBF content was based on self-regulation theory, which involves observing one’s behavior and making judgments on the observations, testing strategies to improve asthma management, and reacting to positive results of these strategies with enhanced self-efficacy and outcome expectations, ie, the belief that a given strategy will produce the desired results [59]. In WBF, participants used a problem-solving process based on this framework to carry out recommendations in their physician’s therapeutic plan. WBF also incorporated special attention to sex- and gender-based factors in asthma management.

Over a 12-month period, women who participated in the intervention relative to controls experienced significant reductions in nighttime symptoms, days of missed work/school, emergency department visits, and both scheduled and urgent office visits. Intervention group women also reported decreased asthma symptoms during sexual activity, improved asthma-related quality of life, and increased confidence to manage asthma. At long-term follow-up (2 years from baseline), persistent positive effects of the intervention were found on outpatient visits for asthma symptom level during sexual activity, days of missed work/school, asthma-related quality of life, and confidence to manage asthma [60].

In a follow-up study, Clark and colleagues [61] developed the “Women of Color and Asthma Control” (WCAC) program. WCAC incorporates the theoretical orientation and many of the program elements of Women Breathe Free, but has been adapted to be responsive to the needs and preferences of African-American women. Poverty and race are associated with greater asthma morbidity and mortality [5,62,63]. African-American women and women of low socioeconomic status are particularly vulnerable to asthma and associated morbidity and mortality, making this an important group for intervention. Culturally responsive components in the WCAC intervention include use of culturally relevant activities and beliefs when discussing triggers and barriers to asthma management, as well as culturally appropriate visuals. This ongoing trial will test WCAC’s effect on ED visits, hospitalizations, and urgent care; asthma symptoms; and asthma-related quality of life at 1 year and 18 months from baseline.

In a small RCT among women with asthma, Bidwell and colleagues tested a program consisting of 10 weeks of yoga instruction (including breathing practices, poses, and meditation/relaxation skills) in a group setting followed by 10 weeks of home practice [64]. Women in the intervention group reported improved quality of life, as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Quality of Life questionnaire [65], and participants also had decreased parasympathetic modulation in response to an isometric forearm exercise. They conclude that yoga is a promising modality for improving quality of life among asthma patients and that these changes may be linked to better autonomic modulation. Although this program was not designed specifically for women, yoga is practiced significantly more frequently among women compared to men [66,67], and thus has the potential to be widely used in this group.

Based on our experience conducting self-management research among women with asthma, and unpublished process data from these studies, we observe that the following elements appear to contribute to high participant engagement in these programs and successful outcomes. First, in participant feedback questionnaires from the Women Breathe Free and Women of Color and Asthma Control studies, women have singled out the importance of their relationship with their assigned telephone asthma educator as motivating them to make positive changes in their asthma self-management behaviors. The popularity of health and wellness coaching, including for chronic disease management, is rapidly growing [68]. This is a patient-centered approach that guides patients in setting their own goals for disease management and devising their own strategies for achieving them [68]. Strong interpersonal relationships are thought to enhance the coaching process and this may be especially important for women [68]. Participants have also indicated that they are able to apply the goal-setting and problem-solving skills they have learned as part of the intervention to management of other health or psychosocial issues in their lives; therefore this component seems especially critical for women with asthma who are typically managing multiple health issues as well as those of others. Finally, maximizing the flexibility of interventions is important for working-age women who typically are engaged in part- or full-time employment and also have significant responsibilities caring for others. This flexibility can come in the form of telephone-based or “mHealth” interventions that use mobile technologies such as text messaging [69], as well as internet-based or smartphone/tablet “apps” that can be completed at a pace and schedule that is convenient for the participant [70]. Such interventions could be easily tailored to address sex- and gender-specific issues in asthma management.

Future Research and Practice Directions

This review points to several promising directions for research and practice in the area of supporting women’s asthma self-management. The first is a systematic exploration of the added value of gender-tailoring asthma self-management support interventions to determine which subgroups of women benefit from which type of sex- and gender-specific information, and in which form. More research is needed on the relationship between hormone levels and changes and asthma symptoms, and how this affects women’s self-management. This includes recognition of new or worsening asthma with the use of hormone replacement therapy in menopausal and post-menopausal women, a group that is rapidly increasing in number in the US population. Another direction for research is a family-systems approach to asthma education and supporting asthma management. Asthma in one or more first-degree relatives has been shown across diverse populations to be a risk factor for asthma [71]. Women with asthma are therefore more likely to have children with asthma, and vice-versa; however, no prior research was identified that addresses asthma self-management in mother/child dyads. For example, it is possible that teaching women to better manage their own asthma could have “trickle down” effects to how they help a child manage asthma. Last, as the above discussion of factors affecting women’s asthma makes clear, many risk factors for poor asthma management and control in women cluster together, such as obesity, depression, and GERD. Interventions that attempt to address the separate and interacting effects of these factors and comorbidities, may yield better outcomes among the most vulnerable asthma patients.

Corresponding author: Mary R. Janevic, PhD, Center for Managing Chronic Disease, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1425 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health (Dr. Janevic) and the Medical School (Dr. Sanders), University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: Asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are all greater among adult women compared to men. Appropriate asthma self-management can improve asthma control. We reviewed published literature about sex- and gender-related factors that influence asthma self-management among women, as well as evidence-based interventions to promote effective asthma self-management in this population.

- Design: Based on evidence from the published literature, factors influencing women’s asthma self-management were categorized as follows: social roles and socioeconomic status, comorbidities, obesity, hormonal factors, and aging-related changes.

- Results: A number of factors were identified that affect women’s asthma self-management. These include: exposure to asthma triggers associated with gender roles, such as cleaning products; financial barriers to asthma management; comorbidities that divert attention or otherwise interfere with asthma management; a link between obesity and poor asthma outcomes; the effects of hormonal shifts associated with menstrual cycles and menopause on asthma control; and aging-associated barriers to effective self-management such as functional limitations and caregiving. Certain groups, such as African-American women, are at higher risk for poor asthma outcomes linked to many of the above factors. At least 1 health coaching intervention designed for women with asthma has been shown in a randomized trial to reduce symptoms and health care use.

- Conclusion: Future research on women and asthma self-management should include a focus on the relationship between hormonal changes and asthma symptoms. Interventions are also needed that address the separate and interacting effects of risk factors for poor asthma control that tend to cluster in women, such as obesity, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In childhood, asthma is more prevalent in boys than in girls. In adolescence and adulthood, however, asthma becomes a predominantly female disease, with hormonal factors likely playing a role in this shift [1,2]. Fu et al [3] reviewed daily asthma symptom diaries of 418 children. From age 5 to 7, boys had more severe symptoms, but by age 10 girls’ symptoms were becoming more severe. By age 14, the girls’ symptoms continued increasing while the boys’ symptoms began to decline. A meta-analysis by Lieberoth et al [4] found a 37% increased risk of post-menarchal asthma in girls with onset of menarche < 12 years. Together, these studies implicate female sex hormones in both the increased incidence and severity of asthma after puberty. In 2012, nearly 10% of adult women reported current asthma, compared to only 6% of men [5]. Among adults with asthma, women have a 30% higher mortality rate than men [6]. Disparities that disadvantage women are also evident across a range of other asthma-related outcomes, including disease severity, rescue inhaler use, activity limitations, asthma-related quality of life, and health care utilization [7–12].

Factors Influencing Asthma Self-Management in Women

Social Roles and Socioeconomic Status

Traditional gender roles involve various responsibilities, such as household cleaning, cooking, and care of young children, that are associated with exposures to precipitants of asthma symptoms [17]. Gender norms also promote the use of personal care products, like fragrances and hair sprays, which are potential asthma triggers [17]. Recent observational studies in Europe have examined the link between women’s use of cleaning products and asthma. Bédard and colleagues [18] found an association between weekly use of cleaning sprays at home and asthma among women, and Dumas and colleagues [19] found that workplace exposure to cleaning products among women with asthma was related to increased symptoms and severity of asthma. These researchers conclude that “while domestic exposure is much more frequent in the general population, exposure levels are probably higher at the workplace” and therefore both contribute to asthma disease burden [19]. Although little-discussed in the literature, sexual activity is another common trigger of asthma symptoms in women. Clark et al [15] found that more than one-third of women taking part in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an asthma self-management intervention reported being bothered by symptoms of asthma during sexual activity. This topic was rarely discussed, however, by their health care providers [20].

Socioeconomic factors also play a significant role in asthma management. There is a well-recognized and persistent gender gap in income in the U.S. population such that women who work full-time only earn three-quarters of what their male counterparts earn [21]. Challenges related to low socioeconomic status (SES) may contribute to poor medication adherence among asthma patients [22]. Although a comprehensive review of the impact of SES-related factors on asthma prevalence, severity, and disease-management behaviors is beyond the scope of this article, recent research demonstrates the impact of financial stress on women’s asthma self-management. Patel et al (2014) studied health-related financial burden among African-American women with asthma [23]. Despite the fact that the majority of women in this qualitative study had health insurance, they felt greatly burdened by out-of-pocket expenses such as high co-pays for medications or ambulance use, lost wages due to sick time, and gaps in insurance coverage. These financial concerns—and related issues such as time spent navigating health care insurance and cycling through private and public insurance programs—were described as a significant source of ongoing stress by this group of vulnerable asthma patients [23]. Focus group participants reported several strategies for dealing with asthma-related financial challenges, including stockpiling medications when feasible (eg, when covered by current insurance plan) for future use by the patient or a family member, seeking out and using community assistance programs, and foregoing medications altogether during periods when they could not afford them [23].

Comorbidities

The 2010 publication of Multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework by the US Department of Health and Human Services [24] brought the attention of the medical and research communities to the scope and significance of multimorbidity in the US population, including the challenges that individuals face in managing multiple chronic health conditions. Although the prevalence of specific comorbidities with asthma differs by age, some that are most commonly associated with asthma and that may complicate asthma control are obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), rhinitis, and sinusitis [25,26]. Among women with asthma, multimorbidity appears to be the rule, not the exception. Using nationally-representative data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Patel et al [27] found that more than half of adults with asthma reported also being diagnosed with at least 1 additional major chronic condition. A recent study found that asthma/arthritis and asthma/hypertension were the second and third most prevalent disease dyads among all US women aged 18–44 years [28]. Studies have found that comorbidities among asthma patients are associated with worse asthma outcomes, including increased symptoms, activity limitations and sleep disturbance due to asthma [27], and ED use for asthma [15,27].

Qualitative research yields insight into the patient perspective of multimorbidity, that is, how women with asthma and coexisting chronic diseases perceive the effect of their health conditions on their ability to engage in self-management. Janevic and colleagues [29] conducted face-to-face interviews with African-American women participating in a randomized controlled trial of a culturally and gender-tailored asthma-management intervention to learn about their experiences managing asthma and concurrent health conditions. Interviewees had an average of 5.7 chronic conditions in addition to asthma. Women reported that managing their asthma often “took a backseat” to other chronic conditions. Participants also discussed reduced motivation or capacity for asthma self-management due to depression, chronic pain, mobility limitations or combinations of these, and reduced adherence to asthma medications due to the psychological and logistical burdens of polypharmacy.

Depression and anxiety are common comorbidities that are associated with worse asthma outcomes [26,30–32] and reduced asthma medication adherence [33,34]. In general population studies as well as among asthma patients, women are more likely than men to report depression and anxiety [30,35–37]. Screening for and treating depression and anxiety are indicated in women with asthma and may lead to improved adherence and outcomes [30].

Obesity

Adults with asthma are at increased risk of obesity [38]. Obesity is a possible risk factor for development of asthma in women [2] and for resting dyspnea in women with asthma [39]. It is associated with poor asthma-related QOL and use of emergency/urgent services [40]. Evidence is mixed regarding the link between BMI and asthma control [41–43], but the following studies suggest that women who are overweight/obese face unique asthma management challenges. Valerio and colleagues found that in a sample of 808 women enrolled in a randomized trial of an asthma-education intervention, nearly 7 out of 10 were overweight (BMI ≥ 25) or obese (BMI ≥ 30), and nearly a quarter were “extremely obese” (BMI > 35) [44]. This subgroup of women was more likely to have persistent asthma, comorbid GERD and urinary incontinence, to be non-white, and to have lower levels of education and income. Being overweight was also associated with greater use of health care services and having greater psychosocial challenges (ie, a higher need for asthma-related social support and lower asthma-related quality of life). These authors suggest the need to design communications for overweight women with asthma that recognize “the specific cultural and social influences on their asthma management behaviors” [44] with a focus on psychosocial needs, while incorporating existing social support networks. In the previously discussed study by Janevic and colleagues [29] the average BMI of the interview participants was 36.0, and a number of respondents identified weight loss as the self-care behavior that they thought would benefit them the most across multimorbid conditions. Therefore, health care providers should provide appropriate counseling and/or referrals to help women with asthma achieve weight loss goals. Given trends over time showing increasing prevalence of asthma and obesity [45,46], interest is growing in the asthma research community about the interaction of the 2 conditions.

Hormonal Factors

Hormones exert a significant effect on asthma in women, and must be considered in clinical and self-management of the disease. Hormone levels fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, with a surge of estradiol (a type of estrogen) at the time of ovulation around day 14, accompanied by low levels of progesterone. During the luteal phase (day 14–28 of the menstrual cycle), estrogens decrease while progesterone levels increase then decrease again before onset of menstruation [47]. During pregnancy, levels of estrogens and progesterone increase and are the highest during the third trimester, when women usually experience good asthma control. Then, during menopause both estradiol and progesterone levels drop to lower levels than those during any phase of menstruation. In addition to the role in the menstrual cycle, there are estrogen receptors (ER-α and ER-β) which are expressed in the human lung and have a role in both airway responsiveness (relaxation) and inflammation [48]. Estrogen also acts directly on cells of the immune system to stimulate airway inflammation, particularly when allergens are present [48]. Further discussion about these contrasting actions of estrogen can be found in a recent review [48].

During the reproductive years, 30% to 40% of women with asthma report perimenstrual symptoms. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity are lowest in the periovulatory period, when estrogen levels are high. In contrast, during the luteal phase, studies have shown increased airway hyperreactivity, especially in the premenstrual period when estrogen levels are low [49]. However, when asthma patients with and without perimenstrual symptoms are evaluated, there is no significant difference in their perimenstrual estrogen and progesterone levels [50]. Clark et al [15] found women participating in a self-management intervention, which included checking daily peak flow rates, reported significantly more menstrual and perimenstrual asthma symptomatology than the control group. This suggests that some women with asthma have may have, but do not recognize, perimenstrual symptoms. Further elucidation of the incidence of symptomatology related to the menstrual cycle as well as the role of hormonal variation is an area for future research efforts.

At the time of menopause and continuing to postmenopause, levels of both estrogen and progesterone drop to below those during the reproductive years, leading to uncomfortable symptoms in many women. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with either estrogen alone or estrogen-progesterone combination effectively improves these, but there is concern for potential effects on asthma prevalence and severity. Two recent large studies support this concern. Postmenopausal women followed for 10 years in the Nurses’ Health Study with a history of HRT had an increased risk of new onset asthma when compared to postmenopausal women with no history of estrogen use (RR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.69–3.14) [51]. This persisted in estrogen-progesterone users. A large French cohort confirmed the increased onset of new asthma in users of estrogen-alone replacement therapy (HR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.13–2.09). However, this effect decreased with time if estrogen had been discontinued, and they did not find a similar increase in users of estrogen-progesterone combination therapy [52]. In contrast, Bonelykke et al [53] found an association between ever using HRT and first-ever hospital admission for asthma, in postmenopausal women (HR 1.46, CI 1.21–1.76), and this risk increased with duration of HRT use. It is clear that physicians need to be aware of these potential respiratory complications, inform their patients, and consider new-onset asthma when women on HRT bring complaints of dyspnea, cough, or wheeze. Future randomized trials are needed to clarify the relationship between HRT and asthma, and to test ways to optimize asthma self-management in women experiencing these transitions.

Older Women and Asthma

Although the bulk of research on asthma focuses on children and young adults, asthma in the elderly is receiving increased attention [54], in part because this demographic group has the highest asthma mortality rate and the most frequent hospitalizations [6,55]. In a sample of midlife and older women from the Nurses’ Health Study who had been diagnosed with persistent asthma, Barr et al found that adherence to asthma medication guidelines decreased with age [54]. In this study, women with more severe asthma and those with multimorbidity were less adherent than those without comorbidities, as were women who spent more hours caregiving for an ill spouse. The authors concluded that asthma is undertreated among older women.

Baptist et al (2014) describe several challenges to asthma management of older women by clinicians and by the women themselves [55]. For example, elderly women may be at increased risk for adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroids. Certain medications used to treat comorbidities, such as beta-blockers and aspirin, may also exacerbate asthma symptoms. In terms of self-management, older women may have a decreased ability to perceive breathlessness, requiring monitoring with a peak flow meter to detect reductions in airflow. Comorbidities are particularly prevalent in this age group, and asthma symptoms may be confused with symptoms of other conditions, such as heart disease [56]. Baptist and colleagues note factors common among elderly women that pose potential barriers to successful self-management of asthma, including limited income, poverty, depression, and caregiving [55]. They also mention that functional limitations such as those due to arthritis, visual difficulties, or weakened inspiratory strength can make inhaler use more difficult. It should also be noted that some behaviors may promote asthma self-management in this group; for example, Valerio and colleagues [57] found that women over age 50 were more likely than younger women to keep a daily asthma diary when asked to do so as part of a self-management intervention [57].

Evidence-Based Asthma Self-Management Interventions for Women

For women to achieve optimal asthma control, the unique factors as described above that influence their symptoms and management need to be addressed [58]. Several examples can be found in the literature of behavioral interventions that focus on the particular self-management challenges faced by women. Clark and colleagues reported the results of an RCT of the Women Breathe Free (WBF) program [15,16]. This intervention consisted of asthma self-management education delivered over 5 telephone sessions by a health educator. WBF content was based on self-regulation theory, which involves observing one’s behavior and making judgments on the observations, testing strategies to improve asthma management, and reacting to positive results of these strategies with enhanced self-efficacy and outcome expectations, ie, the belief that a given strategy will produce the desired results [59]. In WBF, participants used a problem-solving process based on this framework to carry out recommendations in their physician’s therapeutic plan. WBF also incorporated special attention to sex- and gender-based factors in asthma management.