User login

Children with comorbid autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at an increased risk of anxiety and mood disorders, a cross-sectional analysis has shown.

“Our study supports that anxiety and mood disorders, although highly prevalent in those with ASD alone, are even more prevalent in individuals who have ADHD,” wrote Eliza Gordon-Lipkin, MD, of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, and her associates. ”The identification of psychiatric conditions in children with ASD is important because these disorders are treatable and affect quality of life.”

The study was published in Pediatrics.

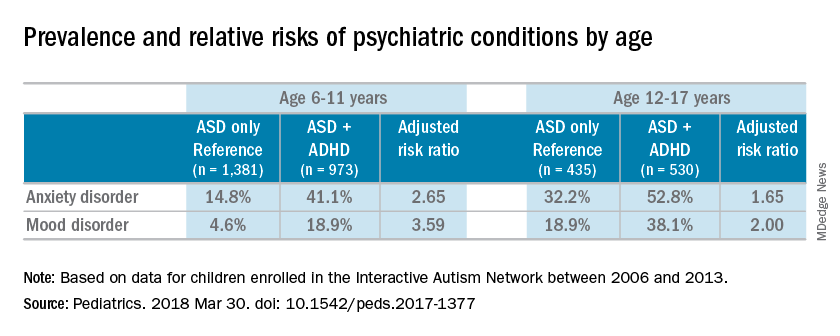

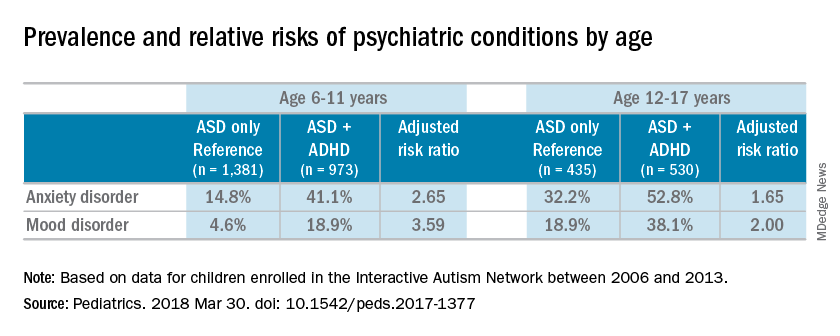

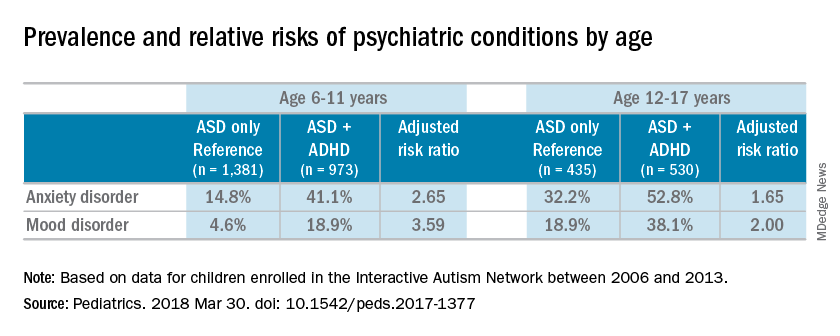

Most of the children were male (83%), white (87%), and non-Hispanic (92%); the mean age of the children was 10 years. Almost half of the children in the study had parent-reported ADHD (45%). Almost one-third of patients were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (31%), and many also were reported to have been diagnosed with a mood disorder (16%). An increased risk of reported anxiety disorder was found in patients with both ADHD and ASD (adjusted relative risk, 2.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.97-2.46).

The researchers also found an increased risk of mood disorders (aRR, 2.72; 95% CI, 2.28-3.24) among children with comorbid conditions. Those risks increased with age (both P less than .001). An increased prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders was found in adolescents, compared with school-aged children with both ASD and ADHD or ASD alone. But higher relative risk ratios were found for the younger children, compared with the adolescents for those in the ADHD/ASD group and the ASD alone group.

“This suggests that or more likely to exhibit detectable symptoms at an earlier age,” reported Dr. Gordon-Lipkin, also with the department of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore.

The research team cited several limitations. For example, patient-reported data might be subject to recall or reporting biases. Also, computer and Internet access was required to complete the IAN questionnaires, which means that the findings could be biased toward people of higher socioeconomic status.

Nevertheless, the researchers wrote, their study is the largest to compare comorbidities in patients with ASD and ADHD, or ASD alone.

Further research is needed to better understand the relationship between ASD and ADHD. “ADHD affects nearly half of the children with ASD. This subgroup of individuals with ASD may represent a distinct clinical phenotype, with different diagnostic and therapeutic implications,” Dr. Gordon-Lipkin and her associates wrote. “Better understanding the differences between children with ASD with and without ADHD is crucial to designing effective interventions.”

None of the study authors had relevant financial disclosures to report. The Interactive Autism Network is funded by the Simons Foundation and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

SOURCE: Gordon-Lipkin E et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Mar 30. doi: 10.1542/ peds.2017-1377.

The work of Gordon-Lipkin et al. is one of the largest studies analyzing the relationships between autism, ADHD, and anxiety and mood disorders. But because of the inherent behavioral and biological complexity of autism, changes in the diagnostic criteria, and the use of parent-reported data, the current study might not reflect what is truly occurring in patients with autism, Christopher J. McDougle, MD, said in an interview.

“There are a number of things to say about [the study]. [One] of the strengths of the paper [is] the sample size,” Dr. McDougle said.“It’s always good to have a big sample size. The downside to having informant-databased information is that it is exactly what it is. This is fine, but the information may be inaccurate.”

In addition to parent-reported data, physicians are dealing with the relatively new diagnostic criteria. The May 2013 update of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to the DSM-5 brought with it the ability to diagnose ADHD with autism, when just the day before the DSM-5 was released, this differential diagnosis was not listed in the manual, Dr. McDougle said. “If something that important can change with the strike of the clock, it makes me concerned.” He also said listing the differential diagnosis in the diagnostic manual underscored the uncertainty of medicine’s understanding of comorbid autism and ADHD.

“That’s reflective of the field’s lack of knowledge. Sometimes I think we like to portray things as though we understand what’s going on, when I think it’s better to be honest and say we really don’t; we are just doing our best.”

Dr. McDougle is the director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital and is the Nancy Lurie Marks Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical Center, both in Boston. He treats children, adolescents, and adults with autism spectrum disorder and other neurodevelopmental disorders. He was asked to comment on this study.

The work of Gordon-Lipkin et al. is one of the largest studies analyzing the relationships between autism, ADHD, and anxiety and mood disorders. But because of the inherent behavioral and biological complexity of autism, changes in the diagnostic criteria, and the use of parent-reported data, the current study might not reflect what is truly occurring in patients with autism, Christopher J. McDougle, MD, said in an interview.

“There are a number of things to say about [the study]. [One] of the strengths of the paper [is] the sample size,” Dr. McDougle said.“It’s always good to have a big sample size. The downside to having informant-databased information is that it is exactly what it is. This is fine, but the information may be inaccurate.”

In addition to parent-reported data, physicians are dealing with the relatively new diagnostic criteria. The May 2013 update of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to the DSM-5 brought with it the ability to diagnose ADHD with autism, when just the day before the DSM-5 was released, this differential diagnosis was not listed in the manual, Dr. McDougle said. “If something that important can change with the strike of the clock, it makes me concerned.” He also said listing the differential diagnosis in the diagnostic manual underscored the uncertainty of medicine’s understanding of comorbid autism and ADHD.

“That’s reflective of the field’s lack of knowledge. Sometimes I think we like to portray things as though we understand what’s going on, when I think it’s better to be honest and say we really don’t; we are just doing our best.”

Dr. McDougle is the director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital and is the Nancy Lurie Marks Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical Center, both in Boston. He treats children, adolescents, and adults with autism spectrum disorder and other neurodevelopmental disorders. He was asked to comment on this study.

The work of Gordon-Lipkin et al. is one of the largest studies analyzing the relationships between autism, ADHD, and anxiety and mood disorders. But because of the inherent behavioral and biological complexity of autism, changes in the diagnostic criteria, and the use of parent-reported data, the current study might not reflect what is truly occurring in patients with autism, Christopher J. McDougle, MD, said in an interview.

“There are a number of things to say about [the study]. [One] of the strengths of the paper [is] the sample size,” Dr. McDougle said.“It’s always good to have a big sample size. The downside to having informant-databased information is that it is exactly what it is. This is fine, but the information may be inaccurate.”

In addition to parent-reported data, physicians are dealing with the relatively new diagnostic criteria. The May 2013 update of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to the DSM-5 brought with it the ability to diagnose ADHD with autism, when just the day before the DSM-5 was released, this differential diagnosis was not listed in the manual, Dr. McDougle said. “If something that important can change with the strike of the clock, it makes me concerned.” He also said listing the differential diagnosis in the diagnostic manual underscored the uncertainty of medicine’s understanding of comorbid autism and ADHD.

“That’s reflective of the field’s lack of knowledge. Sometimes I think we like to portray things as though we understand what’s going on, when I think it’s better to be honest and say we really don’t; we are just doing our best.”

Dr. McDougle is the director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital and is the Nancy Lurie Marks Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical Center, both in Boston. He treats children, adolescents, and adults with autism spectrum disorder and other neurodevelopmental disorders. He was asked to comment on this study.

Children with comorbid autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at an increased risk of anxiety and mood disorders, a cross-sectional analysis has shown.

“Our study supports that anxiety and mood disorders, although highly prevalent in those with ASD alone, are even more prevalent in individuals who have ADHD,” wrote Eliza Gordon-Lipkin, MD, of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, and her associates. ”The identification of psychiatric conditions in children with ASD is important because these disorders are treatable and affect quality of life.”

The study was published in Pediatrics.

Most of the children were male (83%), white (87%), and non-Hispanic (92%); the mean age of the children was 10 years. Almost half of the children in the study had parent-reported ADHD (45%). Almost one-third of patients were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (31%), and many also were reported to have been diagnosed with a mood disorder (16%). An increased risk of reported anxiety disorder was found in patients with both ADHD and ASD (adjusted relative risk, 2.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.97-2.46).

The researchers also found an increased risk of mood disorders (aRR, 2.72; 95% CI, 2.28-3.24) among children with comorbid conditions. Those risks increased with age (both P less than .001). An increased prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders was found in adolescents, compared with school-aged children with both ASD and ADHD or ASD alone. But higher relative risk ratios were found for the younger children, compared with the adolescents for those in the ADHD/ASD group and the ASD alone group.

“This suggests that or more likely to exhibit detectable symptoms at an earlier age,” reported Dr. Gordon-Lipkin, also with the department of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore.

The research team cited several limitations. For example, patient-reported data might be subject to recall or reporting biases. Also, computer and Internet access was required to complete the IAN questionnaires, which means that the findings could be biased toward people of higher socioeconomic status.

Nevertheless, the researchers wrote, their study is the largest to compare comorbidities in patients with ASD and ADHD, or ASD alone.

Further research is needed to better understand the relationship between ASD and ADHD. “ADHD affects nearly half of the children with ASD. This subgroup of individuals with ASD may represent a distinct clinical phenotype, with different diagnostic and therapeutic implications,” Dr. Gordon-Lipkin and her associates wrote. “Better understanding the differences between children with ASD with and without ADHD is crucial to designing effective interventions.”

None of the study authors had relevant financial disclosures to report. The Interactive Autism Network is funded by the Simons Foundation and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

SOURCE: Gordon-Lipkin E et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Mar 30. doi: 10.1542/ peds.2017-1377.

Children with comorbid autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at an increased risk of anxiety and mood disorders, a cross-sectional analysis has shown.

“Our study supports that anxiety and mood disorders, although highly prevalent in those with ASD alone, are even more prevalent in individuals who have ADHD,” wrote Eliza Gordon-Lipkin, MD, of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, and her associates. ”The identification of psychiatric conditions in children with ASD is important because these disorders are treatable and affect quality of life.”

The study was published in Pediatrics.

Most of the children were male (83%), white (87%), and non-Hispanic (92%); the mean age of the children was 10 years. Almost half of the children in the study had parent-reported ADHD (45%). Almost one-third of patients were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (31%), and many also were reported to have been diagnosed with a mood disorder (16%). An increased risk of reported anxiety disorder was found in patients with both ADHD and ASD (adjusted relative risk, 2.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.97-2.46).

The researchers also found an increased risk of mood disorders (aRR, 2.72; 95% CI, 2.28-3.24) among children with comorbid conditions. Those risks increased with age (both P less than .001). An increased prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders was found in adolescents, compared with school-aged children with both ASD and ADHD or ASD alone. But higher relative risk ratios were found for the younger children, compared with the adolescents for those in the ADHD/ASD group and the ASD alone group.

“This suggests that or more likely to exhibit detectable symptoms at an earlier age,” reported Dr. Gordon-Lipkin, also with the department of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore.

The research team cited several limitations. For example, patient-reported data might be subject to recall or reporting biases. Also, computer and Internet access was required to complete the IAN questionnaires, which means that the findings could be biased toward people of higher socioeconomic status.

Nevertheless, the researchers wrote, their study is the largest to compare comorbidities in patients with ASD and ADHD, or ASD alone.

Further research is needed to better understand the relationship between ASD and ADHD. “ADHD affects nearly half of the children with ASD. This subgroup of individuals with ASD may represent a distinct clinical phenotype, with different diagnostic and therapeutic implications,” Dr. Gordon-Lipkin and her associates wrote. “Better understanding the differences between children with ASD with and without ADHD is crucial to designing effective interventions.”

None of the study authors had relevant financial disclosures to report. The Interactive Autism Network is funded by the Simons Foundation and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

SOURCE: Gordon-Lipkin E et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Mar 30. doi: 10.1542/ peds.2017-1377.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: “Better understanding the differences between children with ASD with and without ADHD is crucial to designing effective interventions.”

Major finding: Sixteen percent of the children with autistic spectrum disorder had a mood disorder, and 31% had an anxiety disorder.

Study details: A cross-sectional analysis of information on 3,319 patients, obtained between 2006 and 2013 in the Interactive Autism Network (IAN), an online autism research registry that uses parent report information.

Disclosures: None of the study authors reported relevant financial disclosures. The Interactive Autism Network is funded by the Simons Foundation and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Source: Gordon-Lipkin E et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Mar 30. doi: 10.1542/ peds.2017-1377.